Syllable definition: A syllable is a unit of sound that creates meaning in language. Consonants join vowels to create syllables.

A syllable is one unit of sound in English. Syllables join consonants and vowels to form words.

Syllables can have more than one letter; however, a syllable cannot have more than one sound.

Syllables can have more than one consonant and more than one vowel, as well. However, the consonant(s) and vowel(s) that create the syllable cannot make more than one sound.

A syllable is only one sound.

Examples of Syllables in English

Some words have one syllable (monosyllabic), and some words have many syllables (polysyllabic).

New vowels sounds create new syllables.

- long

- This word has one syllable. There is only one vowel sound, created by the “o.”

- shame

- This word has one syllable. Even though there are two vowels, only one vowel makes a sound. The long “a” sound is the vowel sound; the “e” is a silent “e.”

- silent

- This word has two vowels sounds; therefore it has two syllables. The first syllable is “si” with the long “i” sound. The second syllable includes the letters “lent.”

Open Syllable vs. Closed Syllable

There are two ways that syllables formed in English words: open and closed syllables. Here is a brief discussion of both of those topics.

Open Syllable

Examples of Open Syllables:

- wry

- try

- no

- go

- a

- chew

- brew

Closed Syllable

Examples of Closed Syllables:

- clock

- truck

- ask

- bin

- trim

- gym

- neck

- if

How Many Syllables Are in a Word?

A syllable starts with a vowel sound. That vowel most often joins with a consonant, or consonants, to create a syllable. Syllables will sometimes consist of more than one vowel but never more than one vowel sound.

Syllables create meaning in language. When vowels and consonants join to create sound, words are formed.

A single syllable makes a single sound. Some words have one unit of sound, which means they have one syllable. More than one sound means the word has more than one syllable.

Monosyllabic Words

Single vowel sound

- man

- This word has two consonants and one vowel

- The one vowel sound (the short “a”) joins with the two consonants to create one syllable

- cry

- This word has two consonants and one vowel

- The one vowel (the long “i” sound formed by the “y”) joins with the two consonants to create one syllable

Double vowels with single sound

- brain

- This word has three consonants and two vowels

- The two vowels create one vowel sound (a long “a” sound)

- The single vowel sound joins with the three consonants to make one syllable

- tree

- This word has two consonants and two vowels

- The two vowels create one vowel sound (a long “e” sound)

- The single vowel sound joins with the two consonants to make one syllable

Words ending with a silent “e”

- lane

- This word has two consonants and two vowels

- The “e” and the end of the word is silent to represent a long “a” sound

- The single vowel sound in this word is a long “a” sound

- The single vowel sound joins with the two consonants to make one syllable

- tile

- This word has two consonants and two vowels

- The “e” and the end of the word is silent to represent a long “i” sound

- The single vowel sound in this word is a long “i” sound

- The single vowel sound joins with the two consonants to make one syllable

Polysyllabic Words

- baker

- two syllables

- This word has three consonants and two vowels

- “bak”: two consonants “m” “k” plus one vowel “a”

- “er”: one vowel “e” plus one consonant “r”

- growing

- two syllables

- This word has five consonants and two vowels

- “grow”: three consonants “g”, “r”, and “w” plus one vowel “o”

- “ing”: one vowel “i” plus two consonants “ng”

- terrible

- three syllables

- This word has five consonants and three vowels

- “ter”: two consonants “t” and “r” plus one vowel “e”

- “ri”: one consonant “i” plus one vowel “i”

- “ble” : two consonants “b” and “l” plus one vowel “e”

Note: The last “e” in “terrible” is not silent. The “e” and the end creates more of a “bull” sound when joined with the “b” and “l” than an “e” sound would normally make.

Summary: What are Syllables?

Define syllables: the definition of syllables is a phonological unit consisting of one or more sounds, including a vowel sound.

To sum up, a syllable:

- is a unit of sound in language

- joins vowels with consonants to create meaning

- will always contain only one vowel sound

Contents

- 1 What is a Syllable?

- 2 Examples of Syllables in English

- 3 Open Syllable vs. Closed Syllable

- 4 Open Syllable

- 5 Closed Syllable

- 6 How Many Syllables Are in a Word?

- 7 Monosyllabic Words

- 8 Polysyllabic Words

- 9 Summary: What are Syllables?

A syllable is a unit of organization for a sequence of speech sounds typically made up of a syllable nucleus (most often a vowel) with optional initial and final margins (typically, consonants). Syllables are often considered the phonological «building blocks» of words.[1] They can influence the rhythm of a language, its prosody, its poetic metre and its stress patterns. Speech can usually be divided up into a whole number of syllables: for example, the word ignite is made of two syllables: ig and nite.

Syllabic writing began several hundred years before the first letters. The earliest recorded syllables are on tablets written around 2800 BC in the Sumerian city of Ur. This shift from pictograms to syllables has been called «the most important advance in the history of writing».[2]

A word that consists of a single syllable (like English dog) is called a monosyllable (and is said to be monosyllabic). Similar terms include disyllable (and disyllabic; also bisyllable and bisyllabic) for a word of two syllables; trisyllable (and trisyllabic) for a word of three syllables; and polysyllable (and polysyllabic), which may refer either to a word of more than three syllables or to any word of more than one syllable.

Etymology[edit]

Syllable is an Anglo-Norman variation of Old French sillabe, from Latin syllaba, from Koine Greek συλλαβή syllabḗ (Greek pronunciation: [sylːabɛ̌ː]). συλλαβή means «the taken together», referring to letters that are taken together to make a single sound.[3]

συλλαβή is a verbal noun from the verb συλλαμβάνω syllambánō, a compound of the preposition σύν sýn «with» and the verb λαμβάνω lambánō «take».[4] The noun uses the root λαβ-, which appears in the aorist tense; the present tense stem λαμβάν- is formed by adding a nasal infix ⟨μ⟩ ⟨m⟩ before the β b and a suffix -αν -an at the end.[5]

Transcription[edit]

In the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA), the fullstop ⟨.⟩ marks syllable breaks, as in the word «astronomical» ⟨/ˌæs.trə.ˈnɒm.ɪk.əl/⟩.

In practice, however, IPA transcription is typically divided into words by spaces, and often these spaces are also understood to be syllable breaks. In addition, the stress mark ⟨ˈ⟩ is placed immediately before a stressed syllable, and when the stressed syllable is in the middle of a word, in practice, the stress mark also marks a syllable break, for example in the word «understood» ⟨/ʌndərˈstʊd/⟩ (though the syllable boundary may still be explicitly marked with a full stop,[6] e.g. ⟨/ʌn.dər.ˈstʊd/⟩).

When a word space comes in the middle of a syllable (that is, when a syllable spans words), a tie bar ⟨‿⟩ can be used for liaison, as in the French combination les amis ⟨/lɛ.z‿a.mi/⟩. The liaison tie is also used to join lexical words into phonological words, for example hot dog ⟨/ˈhɒt‿dɒɡ/⟩.

A Greek sigma, ⟨σ⟩, is used as a wild card for ‘syllable’, and a dollar/peso sign, ⟨$⟩, marks a syllable boundary where the usual fullstop might be misunderstood. For example, ⟨σσ⟩ is a pair of syllables, and ⟨V$⟩ is a syllable-final vowel.

Components[edit]

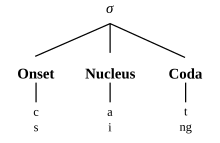

Segmental model for cat and sing

Typical model[edit]

In the typical theory[citation needed] of syllable structure, the general structure of a syllable (σ) consists of three segments. These segments are grouped into two components:

- Onset (ω)

- a consonant or consonant cluster, obligatory in some languages, optional or even restricted in others

- Rime (ρ)

- right branch, contrasts with onset, splits into nucleus and coda

- Nucleus (ν)

- a vowel or syllabic consonant, obligatory in most languages

- Coda (κ)

- a consonant or consonant cluster, optional in some languages, highly restricted or prohibited in others

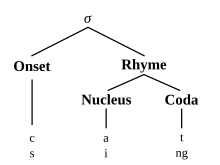

The syllable is usually considered right-branching, i.e. nucleus and coda are grouped together as a «rime» and are only distinguished at the second level.

The nucleus is usually the vowel in the middle of a syllable. The onset is the sound or sounds occurring before the nucleus, and the coda (literally ‘tail’) is the sound or sounds that follow the nucleus. They are sometimes collectively known as the shell. The term rime covers the nucleus plus coda. In the one-syllable English word cat, the nucleus is a (the sound that can be shouted or sung on its own), the onset c, the coda t, and the rime at. This syllable can be abstracted as a consonant-vowel-consonant syllable, abbreviated CVC. Languages vary greatly in the restrictions on the sounds making up the onset, nucleus and coda of a syllable, according to what is termed a language’s phonotactics.

Although every syllable has supra-segmental features, these are usually ignored if not semantically relevant, e.g. in tonal languages.

- Tone (τ)

- may be carried by the syllable as a whole or by the rime

Chinese model[edit]

Traditional Chinese syllable structure

In Chinese syllable structure, the onset is replaced with an initial, and a semivowel or liquid forms another segment, called the medial. These four segments are grouped into two slightly different components:[example needed]

- Initial (ι)

- optional onset, excluding sonorants

- Final (φ)

- medial, nucleus, and final consonant[7]

- Medial (μ)

- optional semivowel or liquid[8]

- Nucleus (ν)

- a vowel or syllabic consonant

- Coda (κ)

- optional final consonant

In many languages of the Mainland Southeast Asia linguistic area, such as Chinese, the syllable structure is expanded to include an additional, optional segment known as a medial, which is located between the onset (often termed the initial in this context) and the rime. The medial is normally a semivowel, but reconstructions of Old Chinese generally include liquid medials (/r/ in modern reconstructions, /l/ in older versions), and many reconstructions of Middle Chinese include a medial contrast between /i/ and /j/, where the /i/ functions phonologically as a glide rather than as part of the nucleus. In addition, many reconstructions of both Old and Middle Chinese include complex medials such as /rj/, /ji/, /jw/ and /jwi/. The medial groups phonologically with the rime rather than the onset, and the combination of medial and rime is collectively known as the final.

Some linguists, especially when discussing the modern Chinese varieties, use the terms «final» and «rime/rhyme» interchangeably. In historical Chinese phonology, however, the distinction between «final» (including the medial) and «rime» (not including the medial) is important in understanding the rime dictionaries and rime tables that form the primary sources for Middle Chinese, and as a result most authors distinguish the two according to the above definition.

Grouping of components[edit]

Hierarchical model for cat and sing

In some theories of phonology, syllable structures are displayed as tree diagrams (similar to the trees found in some types of syntax). Not all phonologists agree that syllables have internal structure; in fact, some phonologists doubt the existence of the syllable as a theoretical entity.[9]

There are many arguments for a hierarchical relationship, rather than a linear one, between the syllable constituents. One hierarchical model groups the syllable nucleus and coda into an intermediate level, the rime. The hierarchical model accounts for the role that the nucleus+coda constituent plays in verse (i.e., rhyming words such as cat and bat are formed by matching both the nucleus and coda, or the entire rime), and for the distinction between heavy and light syllables, which plays a role in phonological processes such as, for example, sound change in Old English scipu and wordu.[10][further explanation needed]

Body[edit]

Left-branching hierarchical model

In some traditional descriptions of certain languages such as Cree and Ojibwe, the syllable is considered left-branching, i.e. onset and nucleus group below a higher-level unit, called a «body» or «core». This contrasts with the coda.

Rime[edit]

The rime or rhyme of a syllable consists of a nucleus and an optional coda. It is the part of the syllable used in most poetic rhymes, and the part that is lengthened or stressed when a person elongates or stresses a word in speech.

The rime is usually the portion of a syllable from the first vowel to the end. For example, /æt/ is the rime of all of the words at, sat, and flat. However, the nucleus does not necessarily need to be a vowel in some languages. For instance, the rime of the second syllables of the words bottle and fiddle is just /l/, a liquid consonant.

Just as the rime branches into the nucleus and coda, the nucleus and coda may each branch into multiple phonemes. The limit for the number of phonemes which may be contained in each varies by language. For example, Japanese and most Sino-Tibetan languages do not have consonant clusters at the beginning or end of syllables, whereas many Eastern European languages can have more than two consonants at the beginning or end of the syllable. In English, the onset may have up to three consonants, and the coda five: strengths can be pronounced as , while angsts can have five coda consonants.

Rime and rhyme are variants of the same word, but the rarer form rime is sometimes used to mean specifically syllable rime to differentiate it from the concept of poetic rhyme. This distinction is not made by some linguists and does not appear in most dictionaries.

| structure: | syllable = | onset | + rhyme |

|---|---|---|---|

| C+V+C*: | C1(C2)V1(V2)(C3)(C4) = | C1(C2) | + V1(V2)(C3)(C4) |

| V+C*: | V1(V2)(C3)(C4) = | ∅ | + V1(V2)(C3)(C4) |

Weight[edit]

Branching nucleus for pout and branching coda for pond

A heavy syllable is generally one with a branching rime, i.e. it is either a closed syllable that ends in a consonant, or a syllable with a branching nucleus, i.e. a long vowel or diphthong. The name is a metaphor, based on the nucleus or coda having lines that branch in a tree diagram.

In some languages, heavy syllables include both VV (branching nucleus) and VC (branching rime) syllables, contrasted with V, which is a light syllable.

In other languages, only VV syllables are considered heavy, while both VC and V syllables are light.

Some languages distinguish a third type of superheavy syllable, which consists of VVC syllables (with both a branching nucleus and rime) or VCC syllables (with a coda consisting of two or more consonants) or both.

In moraic theory, heavy syllables are said to have two moras, while light syllables are said to have one and superheavy syllables are said to have three. Japanese phonology is generally described this way.

Many languages forbid superheavy syllables, while a significant number forbid any heavy syllable. Some languages strive for constant syllable weight; for example, in stressed, non-final syllables in Italian, short vowels co-occur with closed syllables while long vowels co-occur with open syllables, so that all such syllables are heavy (not light or superheavy).

The difference between heavy and light frequently determines which syllables receive stress – this is the case in Latin and Arabic, for example. The system of poetic meter in many classical languages, such as Classical Greek, Classical Latin, Old Tamil and Sanskrit, is based on syllable weight rather than stress (so-called quantitative rhythm or quantitative meter).

Syllabification[edit]

Syllabification is the separation of a word into syllables, whether spoken or written. In most languages, the actually spoken syllables are the basis of syllabification in writing too. Due to the very weak correspondence between sounds and letters in the spelling of modern English, for example, written syllabification in English has to be based mostly on etymological i.e. morphological instead of phonetic principles. English written syllables therefore do not correspond to the actually spoken syllables of the living language.

Phonotactic rules determine which sounds are allowed or disallowed in each part of the syllable. English allows very complicated syllables; syllables may begin with up to three consonants (as in strength), and occasionally end with as many as five (as in angsts, pronounced [æŋsts]). (Some dialects of English pronounce strengths with a four-consonant onset, and angsts with a five-consonant coda: [stʃɹɛŋkθ] and [æŋksts] respectively.) Many other languages are much more restricted; Japanese, for example, only allows /ɴ/ and a chroneme in a coda, and theoretically has no consonant clusters at all, as the onset is composed of at most one consonant.[11]

The linking of a word-final consonant to a vowel beginning the word immediately following it forms a regular part of the phonetics of some languages, including Spanish, Hungarian, and Turkish. Thus, in Spanish, the phrase los hombres (‘the men’) is pronounced [loˈsom.bɾes], Hungarian az ember (‘the human’) as [ɒˈzɛm.bɛr], and Turkish nefret ettim (‘I hated it’) as [nefˈɾe.tet.tim]. In Italian, a final [j] sound can be moved to the next syllable in enchainement, sometimes with a gemination: e.g., non ne ho mai avuti (‘I’ve never had any of them’) is broken into syllables as [non.neˈɔ.ma.jaˈvuːti] and io ci vado e lei anche (‘I go there and she does as well’) is realized as [jo.tʃiˈvaːdo.e.lɛjˈjaŋ.ke]. A related phenomenon, called consonant mutation, is found in the Celtic languages like Irish and Welsh, whereby unwritten (but historical) final consonants affect the initial consonant of the following word.

Ambisyllabicity[edit]

There can be disagreement about the location of some divisions between syllables in spoken language. The problems of dealing with such cases have been most commonly discussed with relation to English. In the case of a word such as hurry, the division may be /hʌr.i/ or /hʌ.ri/, neither of which seems a satisfactory analysis for a non-rhotic accent such as RP (British English): /hʌr.i/ results in a syllable-final /r/, which is not normally found, while /hʌ.ri/ gives a syllable-final short stressed vowel, which is also non-occurring. Arguments can be made in favour of one solution or the other: A general rule has been proposed that states that «Subject to certain conditions …, consonants are syllabified with the more strongly stressed of two flanking syllables»,[12] while many other phonologists prefer to divide syllables with the consonant or consonants attached to the following syllable wherever possible. However, an alternative that has received some support is to treat an intervocalic consonant as ambisyllabic, i.e. belonging both to the preceding and to the following syllable: /hʌṛi/. This is discussed in more detail in English phonology § Phonotactics.

Onset[edit]

The onset (also known as anlaut) is the consonant sound or sounds at the beginning of a syllable, occurring before the nucleus. Most syllables have an onset. Syllables without an onset may be said to have an empty or zero onset – that is, nothing where the onset would be.

Onset cluster[edit]

Some languages restrict onsets to be only a single consonant, while others allow multiconsonant onsets according to various rules. For example, in English, onsets such as pr-, pl- and tr- are possible but tl- is not, and sk- is possible but ks- is not. In Greek, however, both ks- and tl- are possible onsets, while contrarily in Classical Arabic no multiconsonant onsets are allowed at all.

Null onset[edit]

Some languages forbid null onsets. In these languages, words beginning in a vowel, like the English word at, are impossible.

This is less strange than it may appear at first, as most such languages allow syllables to begin with a phonemic glottal stop (the sound in the middle of English uh-oh or, in some dialects, the double T in button, represented in the IPA as /ʔ/). In English, a word that begins with a vowel may be pronounced with an epenthetic glottal stop when following a pause, though the glottal stop may not be a phoneme in the language.

Few languages make a phonemic distinction between a word beginning with a vowel and a word beginning with a glottal stop followed by a vowel, since the distinction will generally only be audible following another word. However, Maltese and some Polynesian languages do make such a distinction, as in Hawaiian /ahi/ (‘fire’) and /ʔahi/ ← /kahi/ (‘tuna’) and Maltese /∅/ ← Arabic /h/ and Maltese /k~ʔ/ ← Arabic /q/.

Ashkenazi and Sephardi Hebrew may commonly ignore א, ה and ע, and Arabic forbid empty onsets. The names Israel, Abel, Abraham, Omar, Abdullah, and Iraq appear not to have onsets in the first syllable, but in the original Hebrew and Arabic forms they actually begin with various consonants: the semivowel /j/ in יִשְׂרָאֵל yisra’él, the glottal fricative in /h/ הֶבֶל heḇel, the glottal stop /ʔ/ in אַבְרָהָם ‘aḇrāhām, or the pharyngeal fricative /ʕ/ in عُمَر ʿumar, عَبْدُ ٱللّٰ ʿabdu llāh, and لْعِرَاق ʿirāq. Conversely, the Arrernte language of central Australia may prohibit onsets altogether; if so, all syllables have the underlying shape VC(C).[13]

The difference between a syllable with a null onset and one beginning with a glottal stop is often purely a difference of phonological analysis, rather than the actual pronunciation of the syllable. In some cases, the pronunciation of a (putatively) vowel-initial word when following another word – particularly, whether or not a glottal stop is inserted – indicates whether the word should be considered to have a null onset. For example, many Romance languages such as Spanish never insert such a glottal stop, while English does so only some of the time, depending on factors such as conversation speed; in both cases, this suggests that the words in question are truly vowel-initial.

But there are exceptions here, too. For example, standard German (excluding many southern accents) and Arabic both require that a glottal stop be inserted between a word and a following, putatively vowel-initial word. Yet such words are perceived to begin with a vowel in German but a glottal stop in Arabic. The reason for this has to do with other properties of the two languages. For example, a glottal stop does not occur in other situations in German, e.g. before a consonant or at the end of word. On the other hand, in Arabic, not only does a glottal stop occur in such situations (e.g. Classical /saʔala/ «he asked», /raʔj/ «opinion», /dˤawʔ/ «light»), but it occurs in alternations that are clearly indicative of its phonemic status (cf. Classical /kaːtib/ «writer» vs. /maktuːb/ «written», /ʔaːkil/ «eater» vs. /maʔkuːl/ «eaten»). In other words, while the glottal stop is predictable in German (inserted only if a stressed syllable would otherwise begin with a vowel),[14] the same sound is a regular consonantal phoneme in Arabic. The status of this consonant in the respective writing systems corresponds to this difference: there is no reflex of the glottal stop in German orthography, but there is a letter in the Arabic alphabet (Hamza (ء)).

The writing system of a language may not correspond with the phonological analysis of the language in terms of its handling of (potentially) null onsets. For example, in some languages written in the Latin alphabet, an initial glottal stop is left unwritten (see the German example); on the other hand, some languages written using non-Latin alphabets such as abjads and abugidas have a special zero consonant to represent a null onset. As an example, in Hangul, the alphabet of the Korean language, a null onset is represented with ㅇ at the left or top section of a grapheme, as in 역 «station», pronounced yeok, where the diphthong yeo is the nucleus and k is the coda.

Nucleus[edit]

| Word | Nucleus |

|---|---|

| cat [kæt] | [æ] |

| bed [bɛd] | [ɛ] |

| ode [oʊd] | [oʊ] |

| beet [bit] | [i] |

| bite [baɪt] | [aɪ] |

| rain [ɻeɪn] | [eɪ] |

| bitten [ˈbɪt.ən] or [ˈbɪt.n̩] |

[ɪ] [ə] or [n̩] |

The nucleus is usually the vowel in the middle of a syllable. Generally, every syllable requires a nucleus (sometimes called the peak), and the minimal syllable consists only of a nucleus, as in the English words «eye» or «owe». The syllable nucleus is usually a vowel, in the form of a monophthong, diphthong, or triphthong, but sometimes is a syllabic consonant.

In most Germanic languages, lax vowels can occur only in closed syllables. Therefore, these vowels are also called checked vowels, as opposed to the tense vowels that are called free vowels because they can occur even in open syllables.

Consonant nucleus[edit]

The notion of syllable is challenged by languages that allow long strings of obstruents without any intervening vowel or sonorant. By far the most common syllabic consonants are sonorants like [l], [r], [m], [n] or [ŋ], as in English bottle, church (in rhotic accents), rhythm, button and lock ‘n key. However, English allows syllabic obstruents in a few para-verbal onomatopoeic utterances such as shh (used to command silence) and psst (used to attract attention). All of these have been analyzed as phonemically syllabic. Obstruent-only syllables also occur phonetically in some prosodic situations when unstressed vowels elide between obstruents, as in potato [pʰˈteɪɾəʊ] and today [tʰˈdeɪ], which do not change in their number of syllables despite losing a syllabic nucleus.

A few languages have so-called syllabic fricatives, also known as fricative vowels, at the phonemic level. (In the context of Chinese phonology, the related but non-synonymous term apical vowel is commonly used.) Mandarin Chinese is famous for having such sounds in at least some of its dialects, for example the pinyin syllables sī shī rī, usually pronounced [sź̩ ʂʐ̩́ ʐʐ̩́], respectively. Though, like the nucleus of rhotic English church, there is debate over whether these nuclei are consonants or vowels.

Languages of the northwest coast of North America, including Salishan, Wakashan and Chinookan languages, allow stop consonants and voiceless fricatives as syllables at the phonemic level, in even the most careful enunciation. An example is Chinook [ɬtʰpʰt͡ʃʰkʰtʰ] ‘those two women are coming this way out of the water’. Linguists have analyzed this situation in various ways, some arguing that such syllables have no nucleus at all and some arguing that the concept of «syllable» cannot clearly be applied at all to these languages.

Other examples:

- Nuxálk (Bella Coola)

- [ɬχʷtʰɬt͡sʰxʷ] ‘you spat on me’

- [t͡sʼkʰtʰskʷʰt͡sʼ] ‘he arrived’

- [xɬpʼχʷɬtʰɬpʰɬɬs] ‘he had in his possession a bunchberry plant’[15]

- [sxs] ‘seal blubber’

In Bagemihl’s survey of previous analyses, he finds that the Bella Coola word /t͡sʼktskʷt͡sʼ/ ‘he arrived’ would have been parsed into 0, 2, 3, 5, or 6 syllables depending on which analysis is used. One analysis would consider all vowel and consonant segments as syllable nuclei, another would consider only a small subset (fricatives or sibilants) as nuclei candidates, and another would simply deny the existence of syllables completely. However, when working with recordings rather than transcriptions, the syllables can be obvious in such languages, and native speakers have strong intuitions as to what the syllables are.

This type of phenomenon has also been reported in Berber languages (such as Indlawn Tashlhiyt Berber), Mon–Khmer languages (such as Semai, Temiar, Khmu) and the Ōgami dialect of Miyako, a Ryukyuan language.[16]

- Indlawn Tashlhiyt Berber

- [tftktst tfktstt] ‘you sprained it and then gave it’

- [rkkm] ‘rot’ (imperf.)[17][18]

- Semai

- [kckmrʔɛːc] ‘short, fat arms’[19]

Coda[edit]

The coda (also known as auslaut) comprises the consonant sounds of a syllable that follow the nucleus. The sequence of nucleus and coda is called a rime. Some syllables consist of only a nucleus, only an onset and a nucleus with no coda, or only a nucleus and coda with no onset.

The phonotactics of many languages forbid syllable codas. Examples are Swahili and Hawaiian. In others, codas are restricted to a small subset of the consonants that appear in onset position. At a phonemic level in Japanese, for example, a coda may only be a nasal (homorganic with any following consonant) or, in the middle of a word, gemination of the following consonant. (On a phonetic level, other codas occur due to elision of /i/ and /u/.) In other languages, nearly any consonant allowed as an onset is also allowed in the coda, even clusters of consonants. In English, for example, all onset consonants except /h/ are allowed as syllable codas.

If the coda consists of a consonant cluster, the sonority typically decreases from first to last, as in the English word help. This is called the sonority hierarchy (or sonority scale).[20] English onset and coda clusters are therefore different. The onset /str/ in strengths does not appear as a coda in any English word. However, some clusters do occur as both onsets and codas, such as /st/ in stardust. The sonority hierarchy is more strict in some languages and less strict in others.

Open and closed[edit]

«Checked syllable» redirects here. For checked syllables in Chinese, see Checked tone.

A coda-less syllable of the form V, CV, CCV, etc. (V = vowel, C = consonant) is called an open syllable or free syllable, while a syllable that has a coda (VC, CVC, CVCC, etc.) is called a closed syllable or checked syllable. They have nothing to do with open and close vowels, but are defined according to the phoneme that ends the syllable: a vowel (open syllable) or a consonant (closed syllable). Almost all languages allow open syllables, but some, such as Hawaiian, do not have closed syllables.

When a syllable is not the last syllable in a word, the nucleus normally must be followed by two consonants in order for the syllable to be closed. This is because a single following consonant is typically considered the onset of the following syllable. For example, Spanish casar («to marry») is composed of an open syllable followed by a closed syllable (ca-sar), whereas cansar «to get tired» is composed of two closed syllables (can-sar). When a geminate (double) consonant occurs, the syllable boundary occurs in the middle, e.g. Italian panna «cream» (pan-na); cf. Italian pane «bread» (pa-ne).

English words may consist of a single closed syllable, with nucleus denoted by ν, and coda denoted by κ:

- in: ν = /ɪ/, κ = /n/

- cup: ν = /ʌ/, κ = /p/

- tall: ν = /ɔː/, κ = /l/

- milk: ν = /ɪ/, κ = /lk/

- tints: ν = /ɪ/, κ = /nts/

- fifths: ν = /ɪ/, κ = /fθs/

- sixths: ν = /ɪ/, κ = /ksθs/

- twelfths: ν = /ɛ/, κ = /lfθs/

- strengths: ν = /ɛ/, κ = /ŋθs/

English words may also consist of a single open syllable, ending in a nucleus, without a coda:

- glue, ν = /uː/

- pie, ν = /aɪ/

- though, ν = /oʊ/

- boy, ν = /ɔɪ/

A list of examples of syllable codas in English is found at English phonology#Coda.

Null coda[edit]

Some languages, such as Hawaiian, forbid codas, so that all syllables are open.

Suprasegmental features[edit]

The domain of suprasegmental features is the syllable (or some larger unit), but not a specific sound. That is to say, these features may effect more than a single segment, and possibly all segments of a syllable:

- Stress

- Tone

- Stød

- Suprasegmental palatalization

Sometimes syllable length is also counted as a suprasegmental feature; for example, in some Germanic languages, long vowels may only exist with short consonants and vice versa. However, syllables can be analyzed as compositions of long and short phonemes, as in Finnish and Japanese, where consonant gemination and vowel length are independent.

Tone[edit]

In most languages, the pitch or pitch contour in which a syllable is pronounced conveys shades of meaning such as emphasis or surprise, or distinguishes a statement from a question. In tonal languages, however, the pitch affects the basic lexical meaning (e.g. «cat» vs. «dog») or grammatical meaning (e.g. past vs. present). In some languages, only the pitch itself (e.g. high vs. low) has this effect, while in others, especially East Asian languages such as Chinese, Thai or Vietnamese, the shape or contour (e.g. level vs. rising vs. falling) also needs to be distinguished.

Accent[edit]

Syllable structure often interacts with stress or pitch accent. In Latin, for example, stress is regularly determined by syllable weight, a syllable counting as heavy if it has at least one of the following:

- a long vowel in its nucleus

- a diphthong in its nucleus

- one or more codas

In each case the syllable is considered to have two morae.

The first syllable of a word is the initial syllable and the last syllable is the final syllable.

In languages accented on one of the last three syllables, the last syllable is called the ultima, the next-to-last is called the penult, and the third syllable from the end is called the antepenult. These terms come from Latin ultima «last», paenultima «almost last», and antepaenultima «before almost last».

In Ancient Greek, there are three accent marks (acute, circumflex, and grave), and terms were used to describe words based on the position and type of accent. Some of these terms are used in the description of other languages.

| Placement of accent | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antepenult | Penult | Ultima | ||

| Type of accent |

Circumflex | — | properispomenon | perispomenon |

| Acute | proparoxytone | paroxytone | oxytone | |

| Any | barytone | — |

History[edit]

Guilhem Molinier, a member of the Consistori del Gay Saber, which was the first literary academy in the world and held the Floral Games to award the best troubadour with the violeta d’aur top prize, gave a definition of the syllable in his Leys d’amor (1328–1337), a book aimed at regulating then-flourishing Occitan poetry:

|

Sillaba votz es literals. |

A syllable is the sound of several letters, |

See also[edit]

- English phonology#Phonotactics. Covers syllable structure in English.

- Entering tone

- IPA symbols for syllables

- Line (poetry)

- List of the longest English words with one syllable

- Minor syllable

- Mora (linguistics)

- Phonology

- Pitch accent

- Stress (linguistics)

- Syllabary writing system

- Syllabic consonant

- Syllabification

- Syllable (computing)

- Timing (linguistics)

- Vocalese

References[edit]

- ^ de Jong, Kenneth (2003). «Temporal constraints and characterising syllable structuring». In Local, John; Ogden, Richard; Temple, Rosalind (eds.). Phonetic Interpretation: Papers in Laboratory Phonology VI. Cambridge University Press. pp. 253–268. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511486425.015. ISBN 978-0-521-82402-6. Page 254.

- ^ Walker, Christopher B. F. (1990). «Cuneiform». Reading the Past: Ancient Writing from Cuneiform to the Alphabet. University of California Press; British Museum. ISBN 0-520-07431-9. as cited in Blainey, Geoffrey (2002). A Short History of the World. Chicago, IL: Dee. p. 60. ISBN 1-56663-507-1.

- ^ Harper, Douglas. «syllable». Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved 2015-01-05.

- ^ λαμβάνω. Liddell, Henry George; Scott, Robert; A Greek–English Lexicon at the Perseus Project

- ^ Smyth 1920, §523: present stems formed by suffixes containing ν

- ^ International Phonetic Association (December 1989). «Report on the 1989 Kiel Convention: International Phonetic Association». Journal of the International Phonetic Association. Cambridge University Press. 19 (2): 75–76. doi:10.1017/S0025100300003868. S2CID 249412330.

- ^ More generally, the letter φ indicates a prosodic foot of two syllables

- ^ More generally, the letter μ indicates a mora

- ^ For discussion of the theoretical existence of the syllable see «CUNY Conference on the Syllable». CUNY Phonology Forum. CUNY Graduate Center. Archived from the original on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 21 June 2022.

- ^ Feng, Shengli (2003). A Prosodic Grammar of Chinese. University of Kansas. p. 3.

- ^ Shibatani, Masayoshi (1987). «Japanese». In Bernard Comrie (ed.). The World’s Major Languages. Oxford University Press. pp. 855–80. ISBN 0-19-520521-9.

- ^ Wells, John C. (1990). «Syllabification and allophony». In Ramsaran, Susan (ed.). Studies in the pronunciation of English : a commemorative volume in honour of A.C. Gimson. Abingdon, UK: Routledge. pp. 76–86. ISBN 9781138918658.

- ^ Breen, Gavan; Pensalfini, Rob (1999). «Arrernte: A Language with No Syllable Onsets» (PDF). Linguistic Inquiry. 30 (1): 1–25. doi:10.1162/002438999553940. JSTOR 4179048. S2CID 57564955.

- ^ Wiese, Richard (2000). Phonology of German. Oxford University Press. pp. 58–61. ISBN 9780198299509.

- ^ Bagemihl 1991, pp. 589, 593, 627

- ^ Pellard, Thomas (2010). «Ōgami (Miyako Ryukyuan)». In Shimoji, Michinori (ed.). An introduction to Ryukyuan languages (PDF). Fuchū, Tokyo: Research Institute for Languages and Cultures of Asia and Africa, Tokyo University of Foreign Studies. pp. 113–166. ISBN 978-4-86337-072-2. Retrieved 21 June 2022. HAL hal-00529598

- ^ Dell & Elmedlaoui 1985

- ^ Dell & Elmedlaoui 1988

- ^ Sloan 1988

- ^ Harrington, Jonathan; Cox, Felicity (August 2014). «Syllable and foot: The syllable and phonotactic constraints». Department of Linguistics. Macquarie University. Retrieved 21 June 2022.

Sources and recommended reading[edit]

- Bagemihl, Bruce (1991). «Syllable structure in Bella Coola». Linguistic Inquiry. 22 (4): 589–646. JSTOR 4178744.

- Clements, George N.; Keyser, Samuel J. (1983). CV phonology: a generative theory of the syllable. Linguistic Inquiry Monographs. Vol. 9. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press. ISBN 9780262030984.

- Dell, François; Elmedlaoui, Mohamed (1985). «Syllabic consonants and syllabification in Imdlawn Tashlhiyt Berber». Journal of African Languages and Linguistics. 7 (2): 105–130. doi:10.1515/jall.1985.7.2.105. S2CID 29304770.

- Dell, François; Elmedlaoui, Mohamed (1988). «Syllabic consonants in Berber: Some new evidence». Journal of African Languages and Linguistics. 10: 1–17. doi:10.1515/jall.1988.10.1.1. S2CID 144470527.

- Ladefoged, Peter (2001). A course in phonetics (4th ed.). Fort Worth, TX: Harcourt College Publishers. ISBN 0-15-507319-2.

- Sloan, Kerry (1988). «Bare-Consonant Reduplication: Implications for a Prosodic Theory of Reduplication». In Borer, Hagit (ed.). The Proceedings of the Seventh West Coast Conference on Formal Linguistics. WCCFL 7. Irvine, CA: University of Chicago Press. pp. 319–330. ISBN 9780937073407.

- Smyth, Herbert Weir (1920). A Greek Grammar for Colleges. American Book Company. Retrieved 1 January 2014 – via CCEL.

External links[edit]

- Syllable Dictionary: Look up the number of syllables in a word. Learn to divide into syllables. Hear it pronounced.

- Do syllables have internal structure? What is their status in phonology? CUNY Phonology Forum Archived 2019-03-30 at the Wayback Machine

- Syllable Word Counter A comprehensive database of words and their syllables

- Syllable drill. Listen to syllables and select its representation in Latin letters

- Syllable counter: Count the number of syllables for any word or sentence.

Noun

The word “doctor” has two syllables.

“Doctor” is a two-syllable word.

The first syllable of the word “doctor” is given stress.

Recent Examples on the Web

Not one syllable of intelligible language is spoken, but the choral anguish of generations subjugated to colonial cruelty rings loud through every wordless frame.

—

Lindsay Lohan also recently joined the ever-growing list of celebrities who corrected fans on the saying of her name, quietly revealing that followers have been stressing the wrong syllable in her last name.

—

His deep, booming voice is relaxed and unhurried, every dragging syllable weighted with heavy breaths and slick with saliva.

—

Too often, though, it’s fussed over, as if every syllable were held up with a jeweler’s loupe and assessed for shine and heft.

—

The melody is sparse and prettily melancholic, but Ferry’s singing is chilly and detached, with every syllable enunciated.

—

Every syllable was an opportunity for a new artistic choice, as though words exist in isolation and sentences have no relation to one another.

—

On average, for every syllable spoken in Japanese, 11 more are spoken in English.

—

No artifice, no forcing one syllable to spread itself thin along many notes.

—

See More

These examples are programmatically compiled from various online sources to illustrate current usage of the word ‘syllable.’ Any opinions expressed in the examples do not represent those of Merriam-Webster or its editors. Send us feedback about these examples.

Select your language

Suggested languages for you:

Syllable

Lerne mit deinen Freunden und bleibe auf dem richtigen Kurs mit deinen persönlichen Lernstatistiken

Jetzt kostenlos anmelden

Ah, the humble syllable. Such a small part of language, yet syllables make up all the words we say across all languages. So, what are they all about? And how can we identify them?

This article is all about syllables and will give a definition for syllable definition, cover the types of syllables in English, and provide some syllable examples. We’ll also cover syllable division – in other words, how to divide a word into its constituent syllables.

Syllable: definition

Before we dive into the intricacies of syllables, let’s begin with our syllable definition. You might already have a good idea of what a syllable is but just in case:

A syllable is a unit of pronunciation that can join other syllables to form longer words or be a word in and of itself. Syllables must contain a singular vowel sound and may or may not have consonants before, after, or surrounding the vowel sound.

To illustrate this, here are some brief examples of what a syllable can look like:

- The indefinite article «a» is a syllable (one vowel sound, with no consonants).

- The word «oven» has two syllables because it has two vowel sounds – «ov» /-ʌv/ + «en» /-ən/ (each of these syllables includes a vowel sound and a consonant).

- Many words consist of only one syllable, such as «run,» «fruit,» «bath,» and «large.» Each of these comprises a combination of one vowel sound and various consonants.

Types of syllables in English

Since you’re an English Language student, we’ll be focusing on the types of syllables in English rather than looking at syllables on a more global level.

There are six key types of syllables in English:

-

Closed syllable: syllables that end in a consonant and have a short vowel sound (e.g., In «picture,» the first syllable, «pic» /pɪk/ ends in a consonant, and the /ɪ/ sound is short).

-

Open syllable: syllables that end in a vowel and have a long vowel sound (e.g., In «zero,» the last syllable «ro» /roʊ/ ends with the vowel sound /oʊ/, which is long).

-

Vowel-consonant-e syllable: syllables that end with a long vowel, a consonant, and a silent -e (e.g., «Fate» is a one-syllable word which ends with a long -a /eɪ/, a consonant (t), and a silent -e).

-

Diphthong (vowel team) syllable: syllables that include two consecutive vowels making a singular sound (e.g., in «shouting,» the first syllable «shout» (ʃaʊt) includes an -o and a -u together that makes one sound — the diphthong /aʊ/).

-

R-controlled syllable: syllables that end in at least one vowel followed by -r (e.g., In the name Peter, the end syllable «er» /ər/ consists of an -e followed by an -r.)

R-controlled syllables are specific to rhotic accents, that is, accents where the -r is pronounced wherever it appears. In Standard American English, the -r at the end of r-controlled syllables is a rhotic /r/, which means it is more pronounced than the non-rhotic /r/ of Standard British English.

In Standard British English, the -r at the end of most words and syllables ending in -r would make a schwa sound (ə) instead of a strong, rhotic /r/ sound. Therefore, non-rhotic British English (and other non-rhotic accents) does not include r-controlled syllables.

There are some British accents that are rhotic, however, such as the Cornish and Devon accents, and there are a couple of American accents which are non-rhotic, such as the Chicago or Upstate New York accents.

-

Consonant-le syllable: syllables that end with a consonant followed by -le (e.g., In «syllable,» the last syllable «ble» /bəl/ ends with the consonant -b followed by -le.)

Each of these syllable types follows the rule of having a singular vowel sound and either no consonants or a range of consonants before, after, or surrounding the vowel sound.

Syllable: examples

An example of a syllable is the word ‘hello’, which has two syllables: «hel» and «lo». To ensure each of these syllable types is cemented in our minds, let’s look at a few more syllable examples for each type:

Closed Syllables

- cat (/kæt/)

- napkin – nap(/næp/) + kin (/kɪn/)

- spin (/spɪn/)

- doughnut – dough + nut (/nʌt/)

In all of these examples, the underlined syllables end with a consonant and have a short vowel sound.

This is generally the first kind of syllable that children are taught to read; many early reading words follow the consonant-vowel-consonant (CVC) pattern («cat,» «mat,» «pin,» «dip,» «dog,» etc.)

Open Syllables

- go (/goʊ/)

- sky (/skaɪ/)

- we (/wi/)

- mosquito – mos + qui + to (/toʊ/)

In all of these examples, the underlined syllables end in a vowel that has a long vowel sound.

Vowel-Consonant-e Syllables

- plate (/pleɪt/)

- tame (/teɪm/)

- mite (/maɪt/)

- bone (/boʊn/)

In all of these examples, the syllables underlined consist of a vowel, followed by a consonant, followed by a silent (or «magic») -e. The -e in each syllable elongates the sound of the vowels.

Diphthong Syllables

- sky (skaɪ)

- trail (/treɪl/)

- spoiled — spoi (/spɔɪ/) + led

In all of these examples, the underlined syllables include two vowels together that make a singular vowel sound.

R-Controlled Syllables

- fir (/fɜːr/)

- burr (/bɜːr/

- plumber – plumb + er (/ər/)

- corridor – cor + ri + dor (/dər/)

In all of these examples, the underlined syllables are made up of a vowel followed by an — r. To reiterate, r-controlled syllables are specific to rhotic accents. Non-rhotic accents do not have r-controlled syllables.

Consonant-le Syllables

- turtle — tur + tle (/təl/)

- hurdle — hur + dle (/dəl/)

- maple — ma + ple (/pəl/)

In all of these examples, the underlined syllables are formed by placing -le after a consonant.

Syllable division

If you aren’t used to doing it, syllable division can sometimes be a bit tricky. What do we mean by ‘syllable division’?

Syllable division simply refers to the process of dividing a word into its constituent syllables.

There are several ways to divide words into syllables, and these ways depend on the composition of the word. There are seven rules you can learn to make syllable division easier.

Syllable rules

The seven syllable rules mentioned above are as follows:

-

A syllable can only have one vowel sound. Using this logic, you can divide words into syllables by looking at the vowel sounds.

Vowels and vowel sounds are two different things.

- a vowel is one of the letters: a, e, i, o, u (and sometimes y)

- a vowel sound is the sound made by the vowel or vowels in a word

The number of vowels in a word does not always equal the number of vowel sounds. For instance, words with a silent «-e,» such as «rate» have two vowels (a and e) but only one vowel sound (eɪ).

The word «plant» only has one vowel sound, so the word itself is only one syllable. The word «coriander,» however, has four vowel sounds and is therefore divided into four syllables – «co» + «ri» + «an» + «der,» where each syllable has a vowel sound.

-

Dividing between two of the same consonant. If a word has two of the same consonant (e.g., «mopping»), you can divide the word into syllables between them (e.g., «mopping» becomes «mop» + «ping»). For this rule to work, the double consonant must have a vowel on either side. In the «mopping» example, there is an «-o» on one side of the double -p and an «-i» on the other.

-

Divide according to the length of the vowel sound. Some vowel sounds are short, some are long, and some words include both. You can figure out where to divide a word into syllables depending on the kind of vowel sounds in that word.

If the first vowel sound in a word is long, then the divide should come after the first vowel. For instance, in the word «deepen,» the first vowel sound is the long -e, so the division into syllables would look like: «dee» + «pen.» In this case, the middle consonant becomes attached to the second vowel sound.

If the first vowel sound in a word is short, then the divide should come before the second vowel sound in the word. In the word «figure,» the first vowel sound is the short -i, so the division into syllables would look like: «fig» + «ure». In this case, the middle consonant attaches to the first vowel sound.

-

Divide between two vowels if they make different sounds. If a word has two vowels next to each other that produce two different sounds, then you should divide between these two vowels (e.g., «diet» becomes «di» + «et», and «diaspora» becomes «di» + «as» + «por» + «a»).

-

Affixes become separate syllables. If a word has been inflected to include a prefix, suffix, or both, then these affixes become their own syllables (e.g., «endless» becomes «end» + «less» and «reread» becomes «re» + «read»).

-

Compound words are always divided between the two words. If a word is made up of two or more other words, then there should be syllable divisions between them.

«Cupcake»: «cup» + «cake»

«Something»: «some» + «thing»

«Sunflower»: «sun» + «flow» + «er» (here, «flower» is split into two syllables because it includes two different vowel sounds — ˈflaʊ + ər ).

-

Divide before consonant-le structures. If a word ends with a consonant followed by -le, then you should divide the word before the consonant preceding the -le (e.g., «needle» becomes «nee» + «dle» and «turtle» becomes «tur» + «tle»).

By following these seven rules, you should be able to identify where a word should be divided into syllables.

Names with two syllables

For a bit of fun, we’ll end this article by looking at some names with two syllables.

This table shows the two-syllable names and how they can be divided into their constituent syllables in IPA (international phonetic alphabet).

| Name | Syllables |

| Harvey | -hɑr + -vi |

| Shannon | -ʃæ + -nən |

| Michael | -maɪ + -kəl |

| Gertrude | -gɜr + -trud |

| Sarah | -sɛ + -rə |

Syllable — Key takeaways

- A syllable is a unit of pronunciation that can either be its own word or can come together with other syllables to make longer words.

- Each syllable can only have one vowel sound in it and may or may not have a variety of consonants around the vowel sound.

- There are six key types of syllables in English: closed, open, vowel-consonant-e, diphthong, r-controlled, and consonant-le.

- Syllable division refers to how words are broken down into their constituent syllables.

- There are seven rules for syllable division.

Frequently Asked Questions about Syllable

A syllable is a unit of pronunciation that can either come together with other syllables to form longer words or be a word in and of itself. Syllables contain a singular vowel sound and may or may not have consonants before, after, or surrounding the vowel sound.

An example of a syllable is the word «English». The syllables are «Eng» and «lish».

There are six types of syllables in English, and knowing these types can help you to identify them in a word. They are:

- open

- closed

- vowel-consonant-e

- diphthong

- r-controlled

- consonant-le

Once you understand what each of the syllable types consists of, you can identify these types in words.

These are some examples of two-syllable words:

- English: Eng + lish

- exact: ex + act

- mother: mo + ther

- classroom: class + room

- begin: be + gin

There are seven rules of syllable division which are as follows:

- A syllable can only have one vowel sound.

- Dividing between two of the same consonant.

- Divide according to the length of the vowel sound.

- Divide between two vowels if they make different sounds.

- Affixes become separate syllables.

- Compound words are always divided between the two words.

- Divide before consonant-le structures.

Every syllable needs to include one vowel sound. Syllables can either be a vowel on their own, or can have consonants attached to the vowel sound.

Final Syllable Quiz

Syllable Quiz — Teste dein Wissen

Question

Briefly describe what a syllable is.

Show answer

Answer

A syllable is a unit of pronunciation that can either come together with other syllables to form longer words, or it can be a word in and of itself. Syllables contain a singular vowel sound and may or may not have consonants before, after, or surrounding the vowel sound.

Show question

Question

True or false, a syllable can have more than one vowel sound in it.

Show answer

Question

True or false, syllables can sometimes include consonants, but don’t always.

Show answer

Question

List the six kinds of syllable in English.

Show answer

Answer

- closed

- open

- vowel-consonant-e

- diphthong

- r-controlled

- consonant-le

Show question

Question

How many syllable division rules are there in English?

Show answer

Question

What is «syllable division»?

Show answer

Answer

When a word is divided into its constituent syllables.

Show question

Question

Using this rule, divide the word «pineapple» into syllables:

A syllable can only have one vowel sound.

Show answer

Question

Using this rule, divide the word «rabbit» into syllables:

Dividing between two of the same consonant.

Show answer

Question

Using this rule, divide the word «feature» into syllables:

Divide according to the length of the vowel sound.

Show answer

Question

Using this rule, divide the word «dieting» into syllables:

Divide between two vowels if they make different sounds.

Show answer

Question

True or false, affixes become their own syllables.

Show answer

Question

Where should you divide a compound word during syllable division?

Show answer

Answer

Compound words should always be divided between their constituent words, as well as following the other syllable division rules.

Show question

Question

Which of these words has the most syllables?

Show answer

Question

Divide the word «plumber» into syllables.

Show answer

Question

Briefly describe each of the six syllable types.

Show answer

Answer

-

Closed syllable: syllables that end in a consonant and have a short vowel sound

-

Open syllable: syllables that end in a vowel and have a long vowel sound

-

Vowel-consonant-e syllable: syllables that end with a long vowel, a consonant, and a silent -e

-

Diphthong (vowel team) syllable: syllables that include two consecutive vowels making a singular sound

-

R-controlled syllable: syllables that end in at least one vowel followed by -r

-

Consonant-le syllable: syllables that end with a consonant followed by -le

Show question

Discover the right content for your subjects

No need to cheat if you have everything you need to succeed! Packed into one app!

Study Plan

Be perfectly prepared on time with an individual plan.

Quizzes

Test your knowledge with gamified quizzes.

Flashcards

Create and find flashcards in record time.

Notes

Create beautiful notes faster than ever before.

Study Sets

Have all your study materials in one place.

Documents

Upload unlimited documents and save them online.

Study Analytics

Identify your study strength and weaknesses.

Weekly Goals

Set individual study goals and earn points reaching them.

Smart Reminders

Stop procrastinating with our study reminders.

Rewards

Earn points, unlock badges and level up while studying.

Magic Marker

Create flashcards in notes completely automatically.

Smart Formatting

Create the most beautiful study materials using our templates.

Sign up to highlight and take notes. It’s 100% free.

This website uses cookies to improve your experience. We’ll assume you’re ok with this, but you can opt-out if you wish. Accept

Privacy & Cookies Policy

Lecture 3.

-

The syllable as the phonological unit.

-

Theories on the syllable division

-

Types and functions of the syllable.

-

Word stress, its nature and functions.

-

Utterance, logical and emphatic stress.

Syllable is the

smallest pronounceable unit which forms language units of greater

magnitud (morphemes, words and phonemes).

The syllable can be considered as the phonetic and phonological unit.

As the phonetic unit the syllable is defined in

articulatory, auditory and acoustic terms.

Acoustically and auditory the syllables are

characteristic by prosodic features:

— the force of the utterance

— the pitch of voice

— sonority

— length

Phonologically the syllable is regarded and

defined in terms of its structural and functional properties. The

term «syllable» denotes smth. taken together.

Phonetic aspect

There are different points of view on syllable

formation.

1. There are as many syllable in a word as

there are vowels.(but in some languages

consonants can be syllabic and it doesn’t explain the boundary of

syllable.)

2. Expiratory

(shest-puls or pressure) theory.

Syllable is a sound or group of the sounds that are pronounced in

one chest-puls . There are as many syllables in a word as there are

chest-pulses made during the word .

The border line between the syllables is a moment of the weaker

expiration (it is quite possible possible to pronounce some syllables

in one articulatory effort).

3. The

relative sonority theory (гучності)

or the prominence theory. It was

created by Danish phonetician O.Jespersen. It is based upon the fact

that each sound was a definite carrying power.

Sounds group themselves according to their

sonority. There are as many syllables as there are peaks of

prominence of sonority.

O.Jespersen classified sounds according to the

degree of sonority. He stayed the scale of sonority of sounds. The

most sonor are vowels. The less sonor are sonorants . The least sonor

consonants are voiced and voiceless.

1. open vowels

2. closed vowels

3. sonorants

4. voiced fricatives

5. voiced plosives

6. voiceless fricatives

7. voiceless plosives

The most sonor sound form the peak of sonority in

a syllable. One peak is separated from another peak by sound of lower

sonority that is consonant.

melt metl s dn

(it doesn’t explain the mechanism )of syllable division and formation

and it doesn’t state to which syllable the less sonorant sound at the

boundary of two words belongs

an aim

a name

summer dresses

some addresses

4. The muscular tension or the articulatory effort theory.

A syllable is characteristic by variations in

muscular tension . The energy of articulation increases at the

beginning of the syllable reaches its maximum within a vowel sound

and decreases towards the end of the syllable.

p l a n t

The syllable is defined as an arc are of artificial tension. The

boundary is determined by lowest articulatory energy. There are as

many syllables as there are max of muscular tension.

Consonants within a syllable are characteristic by

different distribution of muscular tension.

Scherba advanced the theory about 3 types of

consonants :

— finally strong (initially weak) . The end of

the syllable is more energetic. They occur at the beginning of the

syllable /si:/

— cv

— finally weak (initially strong). The beginning

is more energetic, the end is weaker. It occurs at the beginning of

the syllable. /at/

— vc

— double peak. The beginning and the end are

energetic, while the middle is weak. It occurs at the junction of the

words or morphemes: what time /wɒtaɪm/,

unknown /ʌnəʊn/. Acoustically

they produce an effect of 2 consonants.

5. Loudness theory.

It was worked out by N.I.Zhinkin. It took into consideration

Scherba’s statement about peaks. It takes into consideration both

levels production and perception. Syllable is an arc of loudness.

The peak of the syllable is louder and higher in

pitch than the slopes. Zhinkin proved that the organ which is

responsible for the variation of loudness is pharynx . There are as

many syllables in a word as there are arcs of loudness.

Соседние файлы в предмете [НЕСОРТИРОВАННОЕ]

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #