Photograph of the crescent of the planet Neptune (top) and its moon Triton (center), taken by Voyager 2 during its 1989 flyby

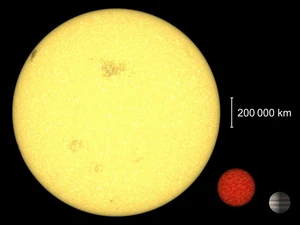

The definition of planet has changed several times since the word was coined by the ancient Greeks. Greek astronomers employed the term ἀστέρες πλανῆται (asteres planetai), ‘wandering stars’, for star-like objects which apparently moved over the sky. Over the millennia, the term has included a variety of different celestial bodies, from the Sun and the Moon to satellites and asteroids.

In modern astronomy, there are two primary conceptions of a ‘planet’. Disregarding the often inconsistent technical details, they are whether an astronomical body dynamically dominates its region (that is, whether it controls the fate of other smaller bodies in its vicinity) or whether it is in hydrostatic equilibrium (that is, whether it looks round). These may be characterized as the dynamical dominance definition and the geophysical definition.

The issue of a clear definition for planet came to a head in January 2005 with the discovery of the trans-Neptunian object Eris, a body more massive than the smallest then-accepted planet, Pluto.[1] In its August 2006 response, the International Astronomical Union (IAU), recognised by astronomers as the world body responsible for resolving issues of nomenclature, released its decision on the matter during a meeting in Prague. This definition, which applies only to the Solar System (though exoplanets had been addressed in 2003), states that a planet is a body that orbits the Sun, is massive enough for its own gravity to make it round, and has «cleared its neighbourhood» of smaller objects approaching its orbit. Under this formalized definition, Pluto and other trans-Neptunian objects do not qualify as planets. The IAU’s decision has not resolved all controversies, and while many astronomers have accepted it, some planetary scientists have rejected it outright, proposing a geophysical or similar definition instead.

History[edit]

Planets in antiquity[edit]

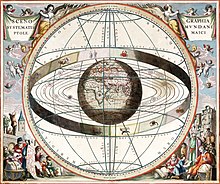

While knowledge of the planets predates history and is common to most civilizations, the word planet dates back to ancient Greece. Most Greeks believed the Earth to be stationary and at the center of the universe in accordance with the geocentric model and that the objects in the sky, and indeed the sky itself, revolved around it (an exception was Aristarchus of Samos, who put forward an early version of heliocentrism). Greek astronomers employed the term ἀστέρες πλανῆται (asteres planetai), ‘wandering stars’,[2][3] to describe those starlike lights in the heavens that moved over the course of the year, in contrast to the ἀστέρες ἀπλανεῖς (asteres aplaneis), the ‘fixed stars’, which stayed motionless relative to one another. The five bodies currently called «planets» that were known to the Greeks were those visible to the naked eye: Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn.

Graeco-Roman cosmology commonly considered seven planets, with the Sun and the Moon counted among them (as is the case in modern astrology); however, there is some ambiguity on that point, as many ancient astronomers distinguished the five star-like planets from the Sun and Moon. As the 19th-century German naturalist Alexander von Humboldt noted in his work Cosmos,

Of the seven cosmical bodies which, by their continually varying relative positions and distances apart, have ever since the remotest antiquity been distinguished from the «unwandering orbs» of the heaven of the «fixed stars», which to all sensible appearance preserve their relative positions and distances unchanged, five only—Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter and Saturn—wear the appearance of stars—»cinque stellas errantes«—while the Sun and Moon, from the size of their disks, their importance to man, and the place assigned to them in mythological systems, were classed apart.[4]

In his Timaeus, written in roughly 360 BCE, Plato mentions, «the Sun and Moon and five other stars, which are called the planets».[5] His student Aristotle makes a similar distinction in his On the Heavens: «The movements of the sun and moon are fewer than those of some of the planets».[6] In his Phaenomena, which set to verse an astronomical treatise written by the philosopher Eudoxus in roughly 350 BCE,[7] the poet Aratus describes «those five other orbs, that intermingle with [the constellations] and wheel wandering on every side of the twelve figures of the Zodiac.»[8]

In his Almagest written in the 2nd century, Ptolemy refers to «the Sun, Moon and five planets.»[9] Hyginus explicitly mentions «the five stars which many have called wandering, and which the Greeks call Planeta.»[10] Marcus Manilius, a Latin writer who lived during the time of Caesar Augustus and whose poem Astronomica is considered one of the principal texts for modern astrology, says, «Now the dodecatemory is divided into five parts, for so many are the stars called wanderers which with passing brightness shine in heaven.»[11]

The single view of the seven planets is found in Cicero’s Dream of Scipio, written sometime around 53 BCE, where the spirit of Scipio Africanus proclaims, «Seven of these spheres contain the planets, one planet in each sphere, which all move contrary to the movement of heaven.»[12] In his Natural History, written in 77 CE, Pliny the Elder refers to «the seven stars, which owing to their motion we call planets, though no stars wander less than they do.»[13] Nonnus, the 5th century Greek poet, says in his Dionysiaca, «I have oracles of history on seven tablets, and the tablets bear the names of the seven planets.»[10]

Planets in the Middle Ages[edit]

Medieval and Renaissance writers generally accepted the idea of seven planets. The standard medieval introduction to astronomy, Sacrobosco’s De Sphaera, includes the Sun and Moon among the planets,[14] the more advanced Theorica planetarum presents the «theory of the seven planets,»[15] while the instructions to the Alfonsine Tables show how «to find by means of tables the mean motuses of the sun, moon, and the rest of the planets.»[16] In his Confessio Amantis, 14th-century poet John Gower, referring to the planets’ connection with the craft of alchemy, writes, «Of the planetes ben begonne/The gold is tilted to the Sonne/The Mone of Selver hath his part…», indicating that the Sun and the Moon were planets.[17] Even Nicolaus Copernicus, who rejected the geocentric model, was ambivalent concerning whether the Sun and Moon were planets. In his De Revolutionibus, Copernicus clearly separates «the sun, moon, planets and stars»;[18] however, in his Dedication of the work to Pope Paul III, Copernicus refers to, «the motion of the sun and the moon… and of the five other planets.»[19]

Earth[edit]

Eventually, when Copernicus’s heliocentric model was accepted over the geocentric, Earth was placed among the planets and the Sun and Moon were reclassified, necessitating a conceptual revolution in the understanding of planets. As the historian of science Thomas Kuhn noted in his book, The Structure of Scientific Revolutions:[20]

The Copernicans who denied its traditional title ‘planet’ to the sun … were changing the meaning of ‘planet’ so that it would continue to make useful distinctions in a world where all celestial bodies … were seen differently from the way they had been seen before… Looking at the moon, the convert to Copernicanism … says, ‘I once took the moon to be (or saw the moon as) a planet, but I was mistaken.’

Copernicus obliquely refers to Earth as a planet in De Revolutionibus when he says, «Having thus assumed the motions which I ascribe to the Earth later on in the volume, by long and intense study I finally found that if the motions of the other planets are correlated with the orbiting of the earth…»[18] Galileo also asserts that Earth is a planet in the Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems: «[T]he Earth, no less than the moon or any other planet, is to be numbered among the natural bodies that move circularly.»[21]

Modern planets[edit]

William Herschel, discoverer of Uranus

In 1781, the astronomer William Herschel was searching the sky for elusive stellar parallaxes, when he observed what he termed a comet in the constellation of Taurus. Unlike stars, which remained mere points of light even under high magnification, this object’s size increased in proportion to the power used. That this strange object might have been a planet simply did not occur to Herschel; the five planets beyond Earth had been part of humanity’s conception of the universe since antiquity. As the asteroids had yet to be discovered, comets were the only moving objects one expected to find in a telescope.[22] However, unlike a comet, this object’s orbit was nearly circular and within the ecliptic plane. Before Herschel announced his discovery of his «comet», his colleague, British Astronomer Royal Nevil Maskelyne, wrote to him, saying, «I don’t know what to call it. It is as likely to be a regular planet moving in an orbit nearly circular to the sun as a Comet moving in a very eccentric ellipsis. I have not yet seen any coma or tail to it.»[23] The «comet» was also very far away, too far away for a mere comet to resolve itself. Eventually it was recognised as the seventh planet and named Uranus after the father of Saturn.

Gravitationally induced irregularities in Uranus’s observed orbit led eventually to the discovery of Neptune in 1846, and presumed irregularities in Neptune’s orbit subsequently led to a search which did not find the perturbing object (it was later found to be a mathematical artefact caused by an overestimation of Neptune’s mass) but did find Pluto in 1930. Initially believed to be roughly the mass of the Earth, observation gradually shrank Pluto’s estimated mass until it was revealed to be a mere five hundredth as large; far too small to have influenced Neptune’s orbit at all.[22] In 1989, Voyager 2 determined the irregularities to be due to an overestimation of Neptune’s mass.[24]

Satellites[edit]

When Copernicus placed Earth among the planets, he also placed the Moon in orbit around Earth, making the Moon the first natural satellite to be identified. When Galileo discovered his four satellites of Jupiter in 1610, they lent weight to Copernicus’s argument, because if other planets could have satellites, then Earth could too. However, there remained some confusion as to whether these objects were «planets»; Galileo referred to them as «four planets flying around the star of Jupiter at unequal intervals and periods with wonderful swiftness.»[25] Similarly, Christiaan Huygens, upon discovering Saturn’s largest moon Titan in 1655, employed many terms to describe it, including «planeta» (planet), «stella» (star), «luna» (moon), and «satellite» (attendant), a word coined by Johannes Kepler.[26][27] Giovanni Cassini, in announcing his discovery of Saturn’s moons Iapetus and Rhea in 1671 and 1672, described them as Nouvelles Planetes autour de Saturne («New planets around Saturn»).[28] However, when the «Journal de Scavans» reported Cassini’s discovery of two new Saturnian moons (Dione and Tethys) in 1686, it referred to them strictly as «satellites», though sometimes Saturn as the «primary planet».[29] When William Herschel announced his discovery of two objects in orbit around Uranus in 1787 (Titania and Oberon), he referred to them as «satellites» and «secondary planets».[30] All subsequent reports of natural satellite discoveries used the term «satellite» exclusively,[31] though the 1868 book «Smith’s Illustrated Astronomy» referred to satellites as «secondary planets».[32]

Minor planets[edit]

Giuseppe Piazzi, discoverer of Ceres

One of the unexpected results of William Herschel’s discovery of Uranus was that it appeared to validate Bode’s law, a mathematical function which generates the size of the semimajor axis of planetary orbits. Astronomers had considered the «law» a meaningless coincidence, but Uranus fell at very nearly the exact distance it predicted. Since Bode’s law also predicted a body between Mars and Jupiter that at that point had not been observed, astronomers turned their attention to that region in the hope that it might be vindicated again. Finally, in 1801, astronomer Giuseppe Piazzi found a miniature new world, Ceres, lying at just the correct point in space. The object was hailed as a new planet.[33]

Then in 1802, Heinrich Olbers discovered Pallas, a second «planet» at roughly the same distance from the Sun as Ceres. The fact that two planets could occupy the same orbit was an affront to centuries of thinking; even Shakespeare had ridiculed the idea («Two stars keep not their motion in one sphere»).[34] Even so, in 1804, another world, Juno, was discovered in a similar orbit.[33] In 1807, Olbers discovered a fourth object, Vesta, at a similar orbital distance.

Herschel suggested that these four worlds be given their own separate classification, asteroids (meaning «starlike» since they were too small for their disks to resolve and thus resembled stars), though most astronomers preferred to refer to them as planets.[33] This conception was entrenched by the fact that, due to the difficulty of distinguishing asteroids from yet-uncharted stars, those four remained the only asteroids known until 1845.[35][36] Science textbooks in 1828, after Herschel’s death, still numbered the asteroids among the planets.[33] With the arrival of more refined star charts, the search for asteroids resumed, and a fifth and sixth were discovered by Karl Ludwig Hencke in 1845 and 1847.[36] By 1851 the number of asteroids had increased to 15, and a new method of classifying them, by affixing a number before their names in order of discovery, was adopted, inadvertently placing them in their own distinct category. Ceres became «(1) Ceres», Pallas became «(2) Pallas», and so on. By the 1860s, the number of known asteroids had increased to over a hundred, and observatories in Europe and the United States began referring to them collectively as «minor planets», or «small planets», though it took the first four asteroids longer to be grouped as such.[33] To this day, «minor planet» remains the official designation for all small bodies in orbit around the Sun, and each new discovery is numbered accordingly in the IAU’s Minor Planet Catalogue.[37]

Pluto[edit]

Clyde Tombaugh, discoverer of Pluto

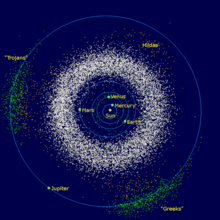

The long road from planethood to reconsideration undergone by Ceres is mirrored in the story of Pluto, which was named a planet soon after its discovery by Clyde Tombaugh in 1930. Uranus and Neptune had been declared planets based on their circular orbits, large masses and proximity to the ecliptic plane. None of these applied to Pluto, a tiny and icy world in a region of gas giants with an orbit that carried it high above the ecliptic and even inside that of Neptune. In 1978, astronomers discovered Pluto’s largest moon, Charon, which allowed them to determine its mass. Pluto was found to be much tinier than anyone had expected: only one-sixth the mass of Earth’s Moon. However, as far as anyone could yet tell, it was unique. Then, beginning in 1992, astronomers began to detect large numbers of icy bodies beyond the orbit of Neptune that were similar to Pluto in composition, size, and orbital characteristics. They concluded that they had discovered the long-hypothesised Kuiper belt (sometimes called the Edgeworth–Kuiper belt), a band of icy debris that is the source for «short-period» comets—those with orbital periods of up to 200 years.[38]

Pluto’s orbit lay within this band and thus its planetary status was thrown into question. Many scientists concluded that tiny Pluto should be reclassified as a minor planet, just as Ceres had been a century earlier. Mike Brown of the California Institute of Technology suggested that a «planet» should be redefined as «any body in the Solar System that is more massive than the total mass of all of the other bodies in a similar orbit.»[39] Those objects under that mass limit would become minor planets. In 1999, Brian G. Marsden of Harvard University’s Minor Planet Center suggested that Pluto be given the minor planet number 10000 while still retaining its official position as a planet.[40][41] The prospect of Pluto’s «demotion» created a public outcry, and in response the International Astronomical Union clarified that it was not at that time proposing to remove Pluto from the planet list.[42][43]

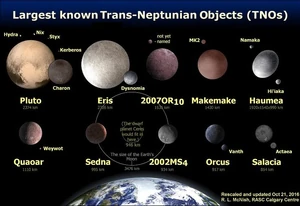

The discovery of several other trans-Neptunian objects, such as Quaoar and Sedna, continued to erode arguments that Pluto was exceptional from the rest of the trans-Neptunian population. On July 29, 2005, Mike Brown and his team announced the discovery of a trans-Neptunian object confirmed to be more massive than Pluto,[44] named Eris.[45]

In the immediate aftermath of the object’s discovery, there was much discussion as to whether it could be termed a «tenth planet». NASA even put out a press release describing it as such.[46] However, acceptance of Eris as the tenth planet implicitly demanded a definition of planet that set Pluto as an arbitrary minimum size. Many astronomers, claiming that the definition of planet was of little scientific importance, preferred to recognise Pluto’s historical identity as a planet by «grandfathering» it into the planet list.[47]

IAU definition[edit]

The discovery of Eris forced the IAU to act on a definition. In October 2005, a group of 19 IAU members, which had already been working on a definition since the discovery of Sedna in 2003, narrowed their choices to a shortlist of three, using approval voting. The definitions were:

- A planet is any object in orbit around the Sun with a diameter greater than 2,000 km. (eleven votes in favour)

- A planet is any object in orbit around the Sun whose shape is stable due to its own gravity. (eight votes in favour)

- A planet is any object in orbit around the Sun that is dominant in its immediate neighbourhood. (six votes in favour)[48][49]

Since no consensus could be reached, the committee decided to put these three definitions to a wider vote at the IAU General Assembly meeting in Prague in August 2006,[50] and on August 24, the IAU put a final draft to a vote, which combined elements from two of the three proposals. It essentially created a medial classification between planet and rock (or, in the new parlance, small Solar System body), called dwarf planet and placed Pluto in it, along with Ceres and Eris.[51][52] The vote was passed, with 424 astronomers taking part in the ballot.[53][54][55]

The IAU therefore resolves that planets and other bodies in our Solar System, except satellites, be defined into three distinct categories in the following way:

(1) A «planet»1 is a celestial body that: (a) is in orbit around the Sun, (b) has sufficient mass for its self-gravity to overcome rigid body forces so that it assumes a hydrostatic equilibrium (nearly round) shape, and (c) has cleared the neighbourhood around its orbit.

(2) A «dwarf planet» is a celestial body that: (a) is in orbit around the Sun, (b) has sufficient mass for its self-gravity to overcome rigid body forces so that it assumes a hydrostatic equilibrium (nearly round) shape2, (c) has not cleared the neighbourhood around its orbit, and (d) is not a satellite.

(3) All other objects3, except satellites, orbiting the Sun shall be referred to collectively as «Small Solar System Bodies».

Footnotes:

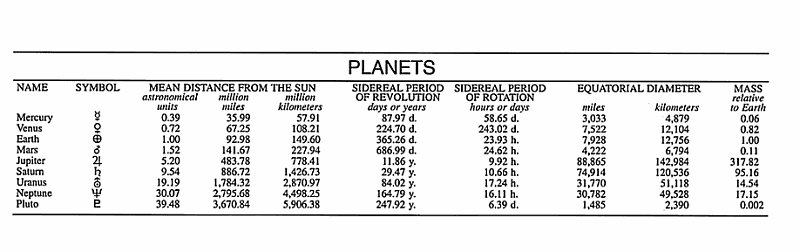

1 The eight planets are: Mercury, Venus, Earth, Mars, Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune.

2 An IAU process will be established to assign borderline objects into either «dwarf planet» and other categories.

3 These currently include most of the Solar System asteroids, most Trans-Neptunian objects (TNOs), comets, and other small bodies.

The IAU further resolves:

Pluto is a «dwarf planet» by the above definition and is recognised as the prototype of a new category of trans-Neptunian objects.

Artistic comparison of Pluto, Eris, Haumea, Makemake, Gonggong, Quaoar, Sedna, Orcus, Salacia, 2002 MS4, and Earth along with the Moon

- v

- t

- e

The IAU also resolved that «planets and dwarf planets are two distinct classes of objects», meaning that dwarf planets, despite their name, would not be considered planets.[55]

On September 13, 2006, the IAU placed Eris, its moon Dysnomia, and Pluto into their Minor Planet Catalogue, giving them the official minor planet designations (134340) Pluto, (136199) Eris, and (136199) Eris I Dysnomia.[56] Other possible dwarf planets, such as 2003 EL61, 2005 FY9, Sedna and Quaoar, were left in temporary limbo until a formal decision could be reached regarding their status.

On June 11, 2008, the IAU executive committee announced the establishment of a subclass of dwarf planets comprising the aforementioned «new category of trans-Neptunian objects» to which Pluto is a prototype. This new class of objects, termed plutoids, would include Pluto, Eris and any other trans-Neptunian dwarf planets, but excluded Ceres. The IAU decided that those TNOs with an absolute magnitude brighter than +1 would be named by a joint commissions of the planetary and minor-planet naming committees, under the assumption that they were likely to be dwarf planets. To date, only two other TNOs, 2003 EL61 and 2005 FY9, have met the absolute magnitude requirement, while other possible dwarf planets, such as Sedna, Orcus and Quaoar, were named by the minor-planet committee alone.[57] On July 11, 2008, the Working Group on Planetary Nomenclature named 2005 FY9 Makemake,[58] and on September 17, 2008, they named 2003 EL61 Haumea.[59]

Acceptance of the IAU definition[edit]

Among the most vocal proponents of the IAU’s decided definition are Mike Brown, the discoverer of Eris; Steven Soter, professor of astrophysics at the American Museum of Natural History; and Neil deGrasse Tyson, director of the Hayden Planetarium.

In the early 2000s, when the Hayden Planetarium was undergoing a $100 million renovation, Tyson refused to refer to Pluto as the ninth planet at the planetarium.[60] He explained that he would rather group planets according to their commonalities rather than counting them. This decision resulted in Tyson receiving large amounts of hate mail, primarily from children.[61] In 2009, Tyson wrote a book detailing the demotion of Pluto.

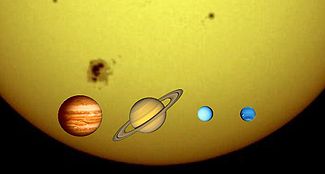

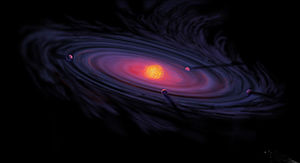

In an article in the January 2007 issue of Scientific American, Soter cited the definition’s incorporation of current theories of the formation and evolution of the Solar System; that as the earliest protoplanets emerged from the swirling dust of the protoplanetary disc, some bodies «won» the initial competition for limited material and, as they grew, their increased gravity meant that they accumulated more material, and thus grew larger, eventually outstripping the other bodies in the Solar System by a very wide margin. The asteroid belt, disturbed by the gravitational tug of nearby Jupiter, and the Kuiper belt, too widely spaced for its constituent objects to collect together before the end of the initial formation period, both failed to win the accretion competition.

When the numbers for the winning objects are compared to those of the losers, the contrast is striking; if Soter’s concept that each planet occupies an «orbital zone»[b] is accepted, then the least orbitally dominant planet, Mars, is larger than all other collected material in its orbital zone by a factor of 5100. Ceres, the largest object in the asteroid belt, only accounts for one third of the material in its orbit; Pluto’s ratio is even lower, at around 7 percent.[62] Mike Brown asserts that this massive difference in orbital dominance leaves «absolutely no room for doubt about which objects do and do not belong.»[63]

Ongoing controversies[edit]

Despite the IAU’s declaration, a number of critics remain unconvinced. The definition is seen by some as arbitrary and confusing. A number of Pluto-as-planet proponents, in particular Alan Stern, head of NASA’s New Horizons mission to Pluto, have circulated a petition among astronomers to alter the definition. Stern’s claim is that, since less than 5 percent of astronomers voted for it, the decision was not representative of the entire astronomical community.[53][64] Even with this controversy excluded, however, there remain several ambiguities in the definition.

Clearing the neighbourhood[edit]

One of the main points at issue is the precise meaning of «cleared the neighbourhood around its orbit». Alan Stern objects that «it is impossible and contrived to put a dividing line between dwarf planets and planets»,[65] and that since neither Earth, Mars, Jupiter, nor Neptune have entirely cleared their regions of debris, none could properly be considered planets under the IAU definition.[c]

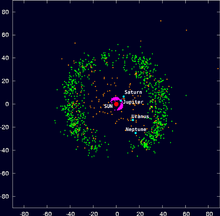

The asteroids of the inner Solar System; note the Trojan asteroids (green), trapped into Jupiter’s orbit by its gravity

Mike Brown counters these claims by saying that, far from not having cleared their orbits, the major planets completely control the orbits of the other bodies within their orbital zone. Jupiter may coexist with a large number of small bodies in its orbit (the Trojan asteroids), but these bodies only exist in Jupiter’s orbit because they are in the sway of the planet’s huge gravity. Similarly, Pluto may cross the orbit of Neptune, but Neptune long ago locked Pluto and its attendant Kuiper belt objects, called plutinos, into a 3:2 resonance, i.e., they orbit the Sun twice for every three Neptune orbits. The orbits of these objects are entirely dictated by Neptune’s gravity, and thus, Neptune is gravitationally dominant.[63]

In October 2015, astronomer Jean-Luc Margot of the University of California Los Angeles proposed a metric for orbital zone clearance derived from whether an object can clear an orbital zone of extent 2√3 of its Hill radius in a specific time scale. This metric places a clear dividing line between the dwarf planets and the planets of the solar system.[66] The calculation is based on the mass of the host star, the mass of the body, and the orbital period of the body. An Earth-mass body orbiting a solar-mass star clears its orbit at distances of up to 400 astronomical units from the star. A Mars-mass body at the orbit of Pluto clears its orbit. This metric, which leaves Pluto as a dwarf planet, applies to both the Solar System and to extrasolar systems.[66]

Some opponents of the definition have claimed that «clearing the neighbourhood» is an ambiguous concept. Mark Sykes, director of the Planetary Science Institute in Tucson, Arizona, and organiser of the petition, expressed this opinion to National Public Radio. He believes that the definition does not categorise a planet by composition or formation, but, effectively, by its location. He believes that a Mars-sized or larger object beyond the orbit of Pluto would not be considered a planet, because he believes that it would not have time to clear its orbit.[67]

Brown notes, however, that were the «clearing the neighbourhood» criterion to be abandoned, the number of planets in the Solar System could rise from eight to more than 50, with hundreds more potentially to be discovered.[68]

Hydrostatic equilibrium[edit]

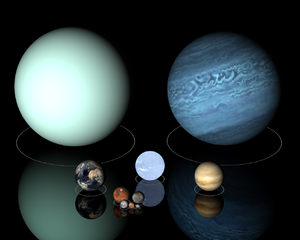

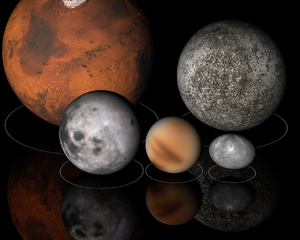

The IAU’s definition mandates that planets be large enough for their own gravity to form them into a state of hydrostatic equilibrium; this means that they will reach a round, ellipsoidal shape. Up to a certain mass, an object can be irregular in shape, but beyond that point gravity begins to pull an object towards its own centre of mass until the object collapses into an ellipsoid. (None of the large objects of the Solar System are truly spherical. Many are spheroids, and several, such as the larger moons of Saturn and the dwarf planet Haumea, have been further distorted into ellipsoids by rapid rotation or tidal forces, but still in hydrostatic equilibrium.[69])

However, there is no precise point at which an object can be said to have reached hydrostatic equilibrium. As Soter noted in his article, «how are we to quantify the degree of roundness that distinguishes a planet? Does gravity dominate such a body if its shape deviates from a spheroid by 10 percent or by 1 percent? Nature provides no unoccupied gap between round and nonround shapes, so any boundary would be an arbitrary choice.»[62] Furthermore, the point at which an object’s mass compresses it into an ellipsoid varies depending on the chemical makeup of the object. Objects made of ices,[d] such as Enceladus and Miranda, assume that state more easily than those made of rock, such as Vesta and Pallas.[68] Heat energy, from gravitational collapse, impacts, tidal forces such as orbital resonances, or radioactive decay, also factors into whether an object will be ellipsoidal or not; Saturn’s icy moon Mimas is ellipsoidal (though no longer in hydrostatic equilibrium), but Neptune’s larger moon Proteus, which is similarly composed but colder because of its greater distance from the Sun, is irregular. In addition, the much larger Iapetus is ellipsoidal but does not have the dimensions expected for its current speed of rotation, indicating that it was once in hydrostatic equilibrium but no longer is,[70] and the same is true for Earth’s moon.[71][72] Even Mercury, universally regarded as a planet, is not in hydrostatic equilibrium.[73]

Double planets and moons[edit]

The definition specifically excludes satellites from the category of dwarf planet, though it does not directly define the term «satellite».[55] In the original draft proposal, an exception was made for Pluto and its largest satellite, Charon, which possess a barycenter outside the volume of either body. The initial proposal classified Pluto–Charon as a double planet, with the two objects orbiting the Sun in tandem. However, the final draft made clear that, even though they are similar in relative size, only Pluto would currently be classified as a dwarf planet.[55]

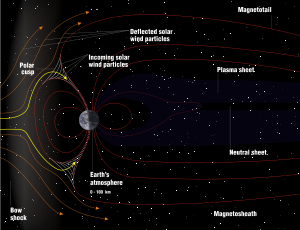

A diagram illustrating the Moon’s co-orbit with the Earth

However, some have suggested that the Moon nonetheless deserves to be called a planet. In 1975, Isaac Asimov noted that the timing of the Moon’s orbit is in tandem with the Earth’s own orbit around the Sun—looking down on the ecliptic, the Moon never actually loops back on itself, and in essence it orbits the Sun in its own right.[74]

Also many moons, even those that do not orbit the Sun directly, often exhibit features in common with true planets. There are 20 moons in the Solar System that are massive enough to have achieved hydrostatic equilibrium (the so-called planetary-mass moons); they would be considered planets if only the physical parameters are considered. Both Jupiter’s moon Ganymede and Saturn’s moon Titan are larger than Mercury, and Titan even has a substantial atmosphere, thicker than the Earth’s. Moons such as Io and Triton demonstrate obvious and ongoing geological activity, and Ganymede has a magnetic field. Just as stars in orbit around other stars are still referred to as stars, some astronomers argue that objects in orbit around planets that share all their characteristics could also be called planets.[75][76][77] Indeed, Mike Brown makes just such a claim in his dissection of the issue, saying:[63]

It is hard to make a consistent argument that a 400 km iceball should count as a planet because it might have interesting geology, while a 5000 km satellite with a massive atmosphere, methane lakes, and dramatic storms [Titan] shouldn’t be put into the same category, whatever you call it.

However, he goes on to say that, «For most people, considering round satellites (including our Moon) ‘planets’ violates the idea of what a planet is.»[63]

Alan Stern has argued that location should not matter and that only geophysical attributes should be taken into account in the definition of a planet, and proposes the term satellite planet for planetary-mass moons.[78]

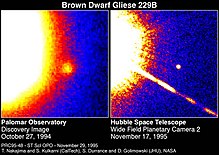

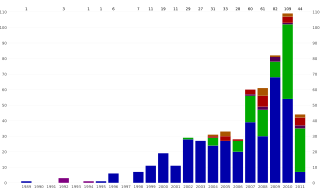

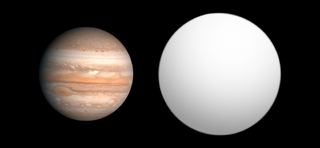

Extrasolar planets and brown dwarfs[edit]

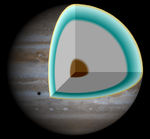

The discovery since 1992 of extrasolar planets, or planet-sized objects around other stars (5,346 such planets in 3,943 planetary systems including 855 multiple planetary systems as of 1 April 2023),[79] has widened the debate on the nature of planethood in unexpected ways. Many of these planets are of considerable size, approaching the mass of small stars, while many newly discovered brown dwarfs are, conversely, small enough to be considered planets.[80] The material difference between a low-mass star and a large gas giant is not clear-cut; apart from size and relative temperature, there is little to separate a gas giant like Jupiter from its host star. Both have similar overall compositions: hydrogen and helium, with trace levels of heavier elements in their atmospheres. The generally accepted difference is one of formation; stars are said to have formed from the «top down», out of the gases in a nebula as they underwent gravitational collapse, and thus would be composed almost entirely of hydrogen and helium, while planets are said to have formed from the «bottom up», from the accretion of dust and gas in orbit around the young star, and thus should have cores of silicates or ices.[81] As yet it is uncertain whether gas giants possess such cores, though the Juno mission to Jupiter could resolve the issue. If it is indeed possible that a gas giant could form as a star does, then it raises the question of whether such an object should be considered an orbiting low-mass star rather than a planet.

Traditionally, the defining characteristic for starhood has been an object’s ability to fuse hydrogen in its core. However, stars such as brown dwarfs have always challenged that distinction. Too small to commence sustained hydrogen-1 fusion, they have been granted star status on their ability to fuse deuterium. However, due to the relative rarity of that isotope, this process lasts only a tiny fraction of the star’s lifetime, and hence most brown dwarfs would have ceased fusion long before their discovery.[82] Binary stars and other multiple-star formations are common, and many brown dwarfs orbit other stars. Therefore, since they do not produce energy through fusion, they could be described as planets. Indeed, astronomer Adam Burrows of the University of Arizona claims that «from the theoretical perspective, however different their modes of formation, extrasolar giant planets and brown dwarfs are essentially the same».[83] Burrows also claims that such stellar remnants as white dwarfs should not be considered stars,[84] a stance which would mean that an orbiting white dwarf, such as Sirius B, could be considered a planet. However, the current convention among astronomers is that any object massive enough to have possessed the capability to sustain atomic fusion during its lifetime and that is not a black hole should be considered a star.[85]

The confusion does not end with brown dwarfs. María Rosa Zapatero Osorio et al. have discovered many objects in young star clusters of masses below that required to sustain fusion of any sort (currently calculated to be roughly 13 Jupiter masses).[86] These have been described as «free floating planets» because current theories of Solar System formation suggest that planets may be ejected from their star systems altogether if their orbits become unstable.[87] However, it is also possible that these «free floating planets» could have formed in the same manner as stars.[88]

In 2003, a working group of the IAU released a position statement[89] to establish a working definition as to what constitutes an extrasolar planet and what constitutes a brown dwarf. To date, it remains the only guidance offered by the IAU on this issue. The 2006 planet definition committee did not attempt to challenge it, or to incorporate it into their definition, claiming that the issue of defining a planet was already difficult to resolve without also considering extrasolar planets.[90] This working definition was amended by the IAU’s Commission F2: Exoplanets and the Solar System in August 2018.[91] The official working definition of an exoplanet is now as follows:

- Objects with true masses below the limiting mass for thermonuclear fusion of deuterium (currently calculated to be 13 Jupiter masses for objects of solar metallicity) that orbit stars, brown dwarfs or stellar remnants and that have a mass ratio with the central object below the L4/L5 instability (M/Mcentral < 2/(25+√621) are «planets» (no matter how they formed).

- The minimum mass/size required for an extrasolar object to be considered a planet should be the same as that used in our Solar System.

The IAU noted that this definition could be expected to evolve as knowledge improves.

CHXR 73 b, an object which lies at the border between planet and brown dwarf

This definition makes location, rather than formation or composition, the determining characteristic for planethood. A free-floating object with a mass below 13 Jupiter masses is a «sub-brown dwarf», whereas such an object in orbit around a fusing star is a planet, even if, in all other respects, the two objects may be identical. Further, in 2010, a paper published by Burrows, David S. Spiegel and John A. Milsom called into question the 13-Jupiter-mass criterion, showing that a brown dwarf of three times solar metallicity could fuse deuterium at as low as 11 Jupiter masses.[92]

Also, the 13 Jupiter-mass cutoff does not have precise physical significance. Deuterium fusion can occur in some objects with mass below that cutoff. The amount of deuterium fused depends to some extent on the composition of the object.[92] As of 2011 the Extrasolar Planets Encyclopaedia included objects up to 25 Jupiter masses, saying, «The fact that there is no special feature around 13 MJup in the observed mass spectrum reinforces the choice to forget this mass limit».[93]

As of 2016 this limit was increased to 60 Jupiter masses[94] based on a study of mass–density relationships.[95] The Exoplanet Data Explorer includes objects up to 24 Jupiter masses with the advisory: «The 13 Jupiter-mass distinction by the IAU Working Group is physically unmotivated for planets with rocky cores, and observationally problematic due to the sin i ambiguity.»[96] The NASA Exoplanet Archive includes objects with a mass (or minimum mass) equal to or less than 30 Jupiter masses.[97]

Another criterion for separating planets and brown dwarfs, rather than deuterium burning, formation process or location, is whether the core pressure is dominated by Coulomb pressure or electron degeneracy pressure.[98][99]

One study suggests that objects above 10 MJup formed through gravitational instability and not core accretion and therefore should not be thought of as planets.[100]

A 2016 study shows no noticeable difference between gas giants and brown dwarfs in mass–radius trends: from approximately one Saturn mass to about 0.080 ± 0.008 M☉ (the onset of hydrogen burning), radius stays roughly constant as mass increases, and no obvious difference occurs when passing 13 MJ. By this measure, brown dwarfs are more like planets than they are like stars.[101]

Planetary-mass stellar objects[edit]

The ambiguity inherent in the IAU’s definition was highlighted in December 2005, when the Spitzer Space Telescope observed Cha 110913-773444 (above), only eight times Jupiter’s mass with what appears to be the beginnings of its own planetary system. Were this object found in orbit around another star, it would have been termed a planet.[102]

In September 2006, the Hubble Space Telescope imaged CHXR 73 b (left), an object orbiting a young companion star at a distance of roughly 200 AU. At 12 Jovian masses, CHXR 73 b is just under the threshold for deuterium fusion, and thus technically a planet; however, its vast distance from its parent star suggests it could not have formed inside the small star’s protoplanetary disc, and therefore must have formed, as stars do, from gravitational collapse.[103]

In 2012, Philippe Delorme, of the Institute of Planetology and Astrophysics of Grenoble in France announced the discovery of CFBDSIR 2149-0403; an independently moving 4–7 Jupiter-mass object that likely forms part of the AB Doradus moving group, less than 100 light years from Earth. Although it shares its spectrum with a spectral class T brown dwarf, Delorme speculates that it may be a planet.[104]

In October 2013, astronomers led by Dr. Michael Liu of the University of Hawaii discovered PSO J318.5-22, a solitary free-floating L dwarf estimated to possess only 6.5 times the mass of Jupiter, making it the least massive sub-brown dwarf yet discovered.[105]

In 2019, astronomers at the Calar Alto Observatory in Spain identified GJ3512b, a gas giant about half the mass of Jupiter orbiting around the red dwarf star GJ3512 in 204 days. Such a large gas giant around such a small star at such a wide orbit is highly unlikely to have formed via accretion, and is more likely to have formed by fragmentation of the disc, similar to a star.[106]

Semantics[edit]

Finally, from a purely linguistic point of view, there is the dichotomy that the IAU created between ‘planet’ and ‘dwarf planet’. The term ‘dwarf planet’ arguably contains two words, a noun (planet) and an adjective (dwarf). Thus, the term could suggest that a dwarf planet is a type of planet, even though the IAU explicitly defines a dwarf planet as not so being. By this formulation therefore, ‘dwarf planet’ and ‘minor planet’ are best considered compound nouns. Benjamin Zimmer of Language Log summarised the confusion: «The fact that the IAU would like us to think of dwarf planets as distinct from ‘real’ planets lumps the lexical item ‘dwarf planet’ in with such oddities as ‘Welsh rabbit’ (not really a rabbit) and ‘Rocky Mountain oysters’ (not really oysters).»[107] As Dava Sobel, the historian and popular science writer who participated in the IAU’s initial decision in October 2006, noted in an interview with National Public Radio, «A dwarf planet is not a planet, and in astronomy, there are dwarf stars, which are stars, and dwarf galaxies, which are galaxies, so it’s a term no one can love, dwarf planet.»[108] Mike Brown noted in an interview with the Smithsonian that «Most of the people in the dynamical camp really did not want the word ‘dwarf planet’, but that was forced through by the pro-Pluto camp. So you’re left with this ridiculous baggage of dwarf planets not being planets.»[109]

Conversely, astronomer Robert Cumming of the Stockholm Observatory notes that, «The name ‘minor planet’ [has] been more or less synonymous with ‘asteroid’ for a very long time. So it seems to me pretty insane to complain about any ambiguity or risk for confusion with the introduction of ‘dwarf planet’.»[107]

See also[edit]

Look up planet in Wiktionary, the free dictionary.

- Geophysical definition of planet

- IAU definition of planet

- List of gravitationally rounded objects of the Solar System

- List of former planets

- Mesoplanet

- Natural kind

- Planemo

- Planetar (astronomy)

- Planetesimal

- Planets in astrology

- Rogue planet

- Sub-brown dwarf

- Timeline of discovery of Solar System planets and their moons

Notes[edit]

- ^ Defined as the region occupied by two bodies whose orbits cross a common distance from the Sun, if their orbital periods differ less than an order of magnitude. In other words, if two bodies occupy the same distance from the Sun at one point in their orbits, and those orbits are of similar size, rather than, as a comet’s would be, extending for several times the other’s distance, then they are in the same orbital zone.[110]

- ^ In 2002, in collaboration with dynamicist Harold Levison, Stern wrote, «we define an überplanet as a planetary body in orbit around a star that is dynamically important enough to have cleared its neighboring planetesimals … And we define an unterplanet as one that has not been able to do so,» and then a few paragraphs later, «our Solar System clearly contains 8 überplanets and a far larger number of unterplanets, the largest of which are Pluto and Ceres.»[111] While this may appear to contradict Stern’s objections, Stern noted in an interview with Smithsonian Air and Space that, unlike the IAU’s definition, his definition still allows unterplanets to be planets: «I do think from a dynamical standpoint, there are planets that really matter in the architecture of the solar system, and those that don’t. They’re both planets. Just as you can have wet and dry planets, or life-bearing and non-life-bearing planets, you can have dynamically important planets and dynamically unimportant planets.»[109]

- ^ The density of an object is a rough guide to its composition: the lower the density, the higher the fraction of ices, and the lower the fraction of rock. The denser objects, Vesta and Juno, are composed almost entirely of rock with very little ice, and have a density close to the Moon’s, while the less dense, such as Proteus and Enceladus, are composed mainly of ice.[112][113]

References[edit]

- ^ Chang, Kenneth (January 18, 2022). «Quiz — Is Pluto A Planet? — Who doesn’t love Pluto? It shares a name with the Roman god of the underworld and a Disney dog. But is it a planet? — Interactive». The New York Times. Retrieved January 18, 2022.

- ^ «Definition of planet». Merriam-Webster OnLine. Retrieved July 23, 2007.

- ^ «Words For Our Modern Age: Especially words derived from Latin and Greek sources». Wordsources.info. Retrieved July 23, 2007.

- ^ Alexander von Humboldt (1849). Cosmos: A Sketch of a Physical Description of the Universe. digitised 2006. H.G. Bohn. p. 297. ISBN 978-0-8018-5503-0. Retrieved July 23, 2007.

- ^ «Timaeus by Plato». The Internet Classics. Retrieved February 22, 2007.

- ^ «On the Heavens by Aristotle, Translated by J. L. Stocks, volume II». University of Adelaide Library. 2004. Archived from the original on August 23, 2008. Retrieved February 24, 2007.

- ^ «Phaenomena Book I — ARATUS of SOLI». Archived from the original on September 1, 2005. Retrieved June 16, 2007.

- ^ Aratus. «Phaemonema». theoi.com. Translated by A. W. & G. R. Mair. Retrieved June 16, 2007.

- ^ Ptolemy (1952). The Almagest. Translated by R. Gatesby Taliaterro. University of Chicago Press. p. 270.

- ^ a b theoi.com. «Astra Planeta». Retrieved February 25, 2007.

- ^ Marcus Manilius (1977). Astronomica. Translated by G. P. Goold. Harvard University Press. p. 141.

- ^ Cicero (1996). «The Dream of Scipio». Roman Philosophy. Translated by Richard Hooker. Archived from the original on July 3, 2007. Retrieved June 16, 2007.

- ^ IH Rackham (1938). Natural History vol 1. William Heinemann Ltd. p. 177, viii.

- ^ Sacrobosco, «On the Sphere», in Edward Grant, ed. A Source Book in Medieval Science, (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1974), p. 450. «every planet except the sun has an epicycle.»

- ^ Anonymous, «The Theory of the Planets,» in Edward Grant, ed. A Source Book in Medieval Science, (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1974), p. 452.

- ^ John of Saxony, «Extracts from the Alfonsine Tables and Rules for their use», in Edward Grant, ed. A Source Book in Medieval Science, (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1974), p. 466.

- ^ P. Heather (1943). «The Seven Planets». Folklore. 54 (3): 338–361. doi:10.1080/0015587x.1943.9717687.

- ^ a b Edward Rosen (trans.). «The text of Nicholas Copernicus’ De Revolutionibus (On the Revolutions), 1543 C.E.» Calendars Through the Ages. Retrieved February 28, 2007.

- ^ Nicolaus Copernicus. «Dedication of the Revolutions of the Heavenly Bodies to Pope Paul III». The Harvard Classics. 1909–14. Retrieved February 23, 2007.

- ^ Thomas S. Kuhn, (1962) The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, 1st. ed., (Chicago: University of Chicago Press), pp. 115, 128–9.

- ^ «Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems». Calendars Through the Ages. Retrieved June 14, 2008.

- ^ a b

Croswell, Ken (1999). Planet Quest: The Epic Discovery of Alien Solar Systems. Oxford University Press. pp. 48, 66. ISBN 978-0-19-288083-3. - ^ Patrick Moore (1981). William Herschel: Astronomer and Musician of 19 New King Street, Bath. PME Erwood. p. 8. ISBN 978-0-907322-06-1.

- ^ Ken Croswell (1993). «Hopes Fade in hunt for Planet X». Retrieved November 4, 2007.

- ^ Galileo Galilei (1989). Siderius Nuncius. Albert van Helden. University of Chicago Press. p. 26.

- ^ «Johannes Kepler: His Life, His Laws and Times». NASA. September 24, 2016. Retrieved September 22, 2022.

- ^ Christiani Hugenii (Christiaan Huygens) (1659). Systema Saturnium: Sive de Causis Miradorum Saturni Phaenomenon, et comite ejus Planeta Novo. Adriani Vlacq. pp. 1–50.

- ^ Giovanni Cassini (1673). Decouverte de deux Nouvelles Planetes autour de Saturne. Sabastien Mabre-Craniusy. pp. 6–14.

- ^ Cassini, G. D. (1686–1692). «An Extract of the Journal Des Scavans. Of April 22 st. N. 1686. Giving an Account of Two New Satellites of Saturn, Discovered Lately by Mr. Cassini at the Royal Observatory at Paris». Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. 16 (179–191): 79–85. Bibcode:1686RSPT…16…79C. doi:10.1098/rstl.1686.0013. JSTOR 101844.

- ^ William Herschel (1787). An Account of the Discovery of Two Satellites Around the Georgian Planet. Read at the Royal Society. J. Nichols. pp. 1–4.

- ^ See primary citations in Timeline of discovery of Solar System planets and their moons

- ^ Smith, Asa (1868). Smith’s Illustrated Astronomy. Nichols & Hall. p. 23.

secondary planet Herschel.

- ^ a b c d e Hilton, James L. «When did asteroids become minor planets?» (PDF). U.S. Naval Observatory. Retrieved May 25, 2006.

- ^ William Shakespeare (1979). King Henry the Fourth Part One in The Globe Illustrated Shakespeare: The Complete Works Annotated. Granercy Books. p. 559.

- ^ «The Planet Hygea». spaceweather.com. 1849. Retrieved June 24, 2008.

- ^ a b Cooper, Keith (June 2007). «Call the Police! The story behind the discovery of the asteroids». Astronomy Now. 21 (6): 60–61.

- ^ «The MPC Orbit (MPCORB) Database». Retrieved October 15, 2007.

- ^ Weissman, Paul R. (1995). «The Kuiper Belt». Annual Review of Astronomy and Astrophysics. 33: 327–357. Bibcode:1995ARA&A..33..327W. doi:10.1146/annurev.aa.33.090195.001551.

- ^ Brown, Mike. «A World on the Edge». NASA Solar System Exploration. Archived from the original on April 27, 2006. Retrieved May 25, 2006.

- ^ «Is Pluto a giant comet?». Central Bureau for Astronomical Telegrams. Retrieved July 3, 2011.

- ^ Kenneth Chang (September 15, 2006). «Xena becomes Eris – Pluto reduced to a number». New York Times. Retrieved June 18, 2008.

- ^ «The Status of Pluto:A clarification». International Astronomical Union, Press release. 1999. Archived from the original on September 23, 2006. Retrieved May 25, 2006. Copy kept Archived October 5, 2008, at the Wayback Machine at the Argonne National Laboratory.

- ^ Witzgall, Bonnie B. (1999). «Saving Planet Pluto». Amateur Astronomer article. Archived from the original on October 16, 2006. Retrieved May 25, 2006.

- ^ Brown, Mike (2006). «The discovery of 2003 UB313, the 10th planet». California Institute of Technology. Retrieved May 25, 2006.

- ^ M. E. Brown; C. A. Trujillo; D. L. Rabinowitz (2005). «DISCOVERY OF A PLANETARY-SIZED OBJECT IN THE SCATTERED KUIPER BELT» (PDF). The American Astronomical Society. Retrieved August 15, 2006.

- ^ «NASA-Funded Scientists Discover Tenth Planet». Jet Propulsion Laboratory. 2005. Retrieved February 22, 2007.

- ^ Bonnie Buratti (2005). «Topic — First Mission to Pluto and the Kuiper Belt; «From Darkness to Light: The Exploration of the Planet Pluto»«. Jet Propulsion Laboratory. Retrieved February 22, 2007.

- ^ McKee, Maggie (2006). «Xena reignites a planet-sized debate». NewScientistSpace. Retrieved May 25, 2006.

- ^ Croswell, Ken (2006). «The Tenth Planet’s First Anniversary». Retrieved May 25, 2006.

- ^ «Planet Definition». IAU. 2006. Archived from the original on August 26, 2006. Retrieved August 14, 2006.

- ^ «IAU General Assembly Newspaper» (PDF). August 24, 2006. Retrieved March 3, 2007.

- ^ «The Final IAU Resolution on the Definition of «Planet» Ready for Voting». IAU (News Release — IAU0602). August 24, 2006. Retrieved March 2, 2007.

- ^ a b Robert Roy Britt (2006). «Pluto demoted in highly controversial definition». Space.com. Retrieved August 24, 2006.

- ^ «IAU 2006 General Assembly: Resolutions 5 and 6» (PDF). IAU. August 24, 2006. Retrieved June 23, 2009.

- ^ a b c d «IAU 2006 General Assembly: Result of the IAU Resolution votes» (Press release). International Astronomical Union (News Release — IAU0603). August 24, 2006. Retrieved December 31, 2007. (orig link Archived January 3, 2007, at the Wayback Machine)

- ^ Central Bureau for Astronomical Telegrams, International Astronomical Union (2006). «Circular No. 8747». Retrieved July 3, 2011. web.archive

- ^ «Plutoid chosen as name for Solar System objects like Pluto». Paris: International Astronomical Union (News Release — IAU0804). June 11, 2008. Archived from the original on June 13, 2008. Retrieved June 11, 2008.

- ^ «Dwarf Planets and their Systems». Working Group for Planetary System Nomenclature (WGPSN). July 11, 2008. Retrieved July 13, 2008.

- ^ «USGS Gazetteer of Planetary Nomenclature». Retrieved September 17, 2008.

- ^ Space com Staff (February 2, 2001). «Astronomer Responds to Pluto-Not-a-Planet Claim». Space.com. Retrieved March 29, 2023.

- ^ The Colbert Report, August 17, 2006

- ^ a b Steven Soter (August 16, 2006). «What is a Planet?». The Astronomical Journal. 132 (6): 2513–2519. arXiv:astro-ph/0608359. Bibcode:2006AJ….132.2513S. doi:10.1086/508861. S2CID 14676169.

- ^ a b c d Michael E. Brown (2006). «The Eight Planets». Caltech. Retrieved February 21, 2007.

- ^ Robert Roy Britt (2006). «Pluto: Down But Maybe Not Out». Space.com. Retrieved August 24, 2006.

- ^ Paul Rincon (August 25, 2006). «Pluto vote ‘hijacked’ in revolt». BBC News. Retrieved February 28, 2007.

- ^ a b Jean-Luc Margot (2015). «A Quantitative Criterion For Defining Planets». The Astronomical Journal. 150 (6): 185. arXiv:1507.06300. Bibcode:2015AJ….150..185M. doi:10.1088/0004-6256/150/6/185. S2CID 51684830.

- ^ Mark, Sykes (September 8, 2006). «Astronomers Prepare to Fight Pluto Demotion» (RealPlayer). NPR.org. Retrieved October 4, 2006.

- ^ a b Mike Brown. «The Dwarf Planets». Retrieved August 4, 2007.

- ^ Brown, Michael E. «2003EL61». California Institute of Technology. Retrieved May 25, 2006.

- ^ Thomas, P. C. (July 2010). «Sizes, shapes, and derived properties of the saturnian satellites after the Cassini nominal mission» (PDF). Icarus. 208 (1): 395–401. Bibcode:2010Icar..208..395T. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2010.01.025. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 23, 2018. Retrieved September 4, 2015.

- ^ Garrick-Bethell et al. (2014) «The tidal-rotational shape of the Moon and evidence for polar wander», Nature 512, 181–184.

- ^ Bursa, M. (October 1, 1984). «Secular Love Numbers and Hydrostatic Equilibrium of Planets». Earth Moon and Planets. 31 (2): 135–140. Bibcode:1984EM&P…31..135B. doi:10.1007/BF00055525. ISSN 0167-9295. S2CID 119815730.

- ^ Sean Solomon, Larry Nittler & Brian Anderson, eds. (2018) Mercury: The View after MESSENGER. Cambridge Planetary Science series no. 21, Cambridge University Press, pp. 72–73.

- ^ Asimov, Isaac (1975). Just Mooning Around, In: Of time and space, and other things. Avon.

- ^ Marc W. Buie (March 2005). «Definition of a Planet». Southwest Research Institute. Retrieved July 7, 2008.

- ^ «IAU Snobbery». NASA Watch (not a NASA Website). June 15, 2008. Retrieved July 5, 2008.

- ^ Serge Brunier (2000). Solar System Voyage. Cambridge University Press. pp. 160–165. ISBN 978-0-521-80724-1.

- ^ «Should Large Moons Be Called ‘Satellite Planets’?». News.discovery.com. May 14, 2010. Archived from the original on May 5, 2012. Retrieved November 4, 2011.

- ^

Schneider, J. (September 10, 2011). «Interactive Extra-solar Planets Catalog». The Extrasolar Planets Encyclopedia. Retrieved July 13, 2012. - ^ «IAU General Assembly: Definition of Planet debate». 2006. Archived from the original on July 13, 2012. Retrieved September 24, 2006.

- ^ G. Wuchterl (2004). «Giant planet formation». Institut für Astronomie der Universität Wien. 67 (1–3): 51–65. Bibcode:1994EM&P…67…51W. doi:10.1007/BF00613290. S2CID 119772190.

- ^ Basri, Gibor (2000). «Observations of Brown Dwarfs». Annual Review of Astronomy and Astrophysics. 38: 485–519. Bibcode:2000ARA&A..38..485B. doi:10.1146/annurev.astro.38.1.485.

- ^ Burrows, Adam; Hubbard, William B.; Lunine, Jonathan I.; Leibert, James (2001). «The Theory of Brown Dwarfs and Extrasolar Giant Planets». Reviews of Modern Physics. 73 (3): 719–765. arXiv:astro-ph/0103383. Bibcode:2001RvMP…73..719B. doi:10.1103/RevModPhys.73.719. S2CID 204927572.

- ^ Croswell p. 119

- ^ Croswell, Ken (1999). Planet Quest: The Epic Discovery of Alien Solar Systems. Oxford University Press. p. 119. ISBN 978-0-19-288083-3.

- ^ Zapatero M. R. Osorio; V. J. S. Béjar; E. L. Martín; R. Rebolo; D. Barrado y Navascués; C. A. L. Bailer-Jones; R. Mundt (2000). «Discovery of Young, Isolated Planetary Mass Objects in the Sigma Orionis Star Cluster». Division of Geological and Planetary Sciences, California Institute of Technology. 290 (5489): 103–107. Bibcode:2000Sci…290..103Z. doi:10.1126/science.290.5489.103. PMID 11021788.

- ^ Lissauer, J. J. (1987). «Timescales for Planetary Accretion and the Structure of the Protoplanetary disk». Icarus. 69 (2): 249–265. Bibcode:1987Icar…69..249L. doi:10.1016/0019-1035(87)90104-7. hdl:2060/19870013947.

- ^ «Rogue planet find makes astronomers ponder theory». Reuters. October 6, 2000. Retrieved May 25, 2006.

- ^ «Working Group on Extrasolar Planets (WGESP) of the International Astronomical Union». IAU. 2001. Archived from the original on September 16, 2006. Retrieved May 25, 2006.

- ^ «General Sessions & Public Talks». International Astronomical Union. 2006. Archived from the original on December 8, 2008. Retrieved November 28, 2008.

- ^ «Official Working Definition of an Exoplanet». IAU position statement. Retrieved November 29, 2020.

- ^ a b David S. Spiegel; Adam Burrows; John A. Milsom (2010). «The Deuterium-Burning Mass Limit for Brown Dwarfs and Giant Planets». The Astrophysical Journal. 727 (1): 57. arXiv:1008.5150. Bibcode:2011ApJ…727…57S. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/727/1/57. S2CID 118513110.

- ^ Schneider, J.; Dedieu, C.; Le Sidaner, P.; Savalle, R.; Zolotukhin, I. (2011). «Defining and cataloging exoplanets: The exoplanet.eu database». Astronomy & Astrophysics. 532 (79): A79. arXiv:1106.0586. Bibcode:2011A&A…532A..79S. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201116713. S2CID 55994657.

- ^ Schneider, Jean (April 4, 2016). «III.8 Exoplanets versus brown dwarfs: The CoRoT view and the future». Exoplanets versus brown dwarfs: the CoRoT view and the future. p. 157. arXiv:1604.00917. doi:10.1051/978-2-7598-1876-1.c038. ISBN 978-2-7598-1876-1. S2CID 118434022.

- ^ Hatzes Heike Rauer, Artie P. (2015). «A Definition for Giant Planets Based on the Mass-Density Relationship». The Astrophysical Journal. 810 (2): L25. arXiv:1506.05097. Bibcode:2015ApJ…810L..25H. doi:10.1088/2041-8205/810/2/L25. S2CID 119111221.

- ^ Wright, J. T.; et al. (2010). «The Exoplanet Orbit Database». arXiv:1012.5676v1 [astro-ph.SR].

- ^ «Exoplanet Criteria for Inclusion in the Exoplanet Archive». exoplanetarchive.ipac.caltech.edu. Retrieved March 29, 2023.

- ^ Basri, Gibor; Brown, Michael E. (2006). «Planetesimals To Brown Dwarfs: What is a Planet?». Annu. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 34: 193–216. arXiv:astro-ph/0608417. Bibcode:2006AREPS..34..193B. doi:10.1146/annurev.earth.34.031405.125058. S2CID 119338327.

- ^ Boss, Alan P.; Basri, Gibor; Kumar, Shiv S.; Liebert, James; Martín, Eduardo L.; Reipurth, Bo; Zinnecker, Hans (2003). «Nomenclature: Brown Dwarfs, Gas Giant Planets, and ?». Brown Dwarfs. 211: 529. Bibcode:2003IAUS..211..529B.

- ^ Schlaufman, Kevin C. (January 18, 2018). «Evidence of an Upper Bound on the Masses of Planets and its Implications for Giant Planet Formation». The Astrophysical Journal. 853: 37. arXiv:1801.06185. doi:10.3847/1538-4357/aa961c. S2CID 55995400.

- ^ Chen, Jingjing; Kipping, David (2016). «Probabilistic Forecasting of the Masses and Radii of Other Worlds». The Astrophysical Journal. 834 (1): 17. arXiv:1603.08614. doi:10.3847/1538-4357/834/1/17. S2CID 119114880. Retrieved July 27, 2021.

- ^ Clavin, Whitney (2005). «A Planet With Planets? Spitzer Finds Cosmic Oddball». Spitzer Science Center. Retrieved May 25, 2006.

- ^ «Planet or failed star? Hubble photographs one of the smallest stellar companions ever seen». ESA Hubble page. 2006. Retrieved February 23, 2007.

- ^ P. Delorme; J. Gagn´e; L. Malo; C. Reyl´e; E. Artigau; L. Albert; T. Forveille; X. Delfosse; F. Allard; D. Homeier (2012). «CFBDSIR2149-0403: a 4–7 Jupiter-mass free-floating planet in the young moving group AB Doradus?». Astronomy & Astrophysics. 548: A26. arXiv:1210.0305. Bibcode:2012A&A…548A..26D. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201219984. S2CID 50935950.

- ^

Liu, Michael C.; Magnier, Eugene A.; Deacon, Niall R.; Allers, Katelyn N.; Dupuy, Trent J.; Kotson, Michael C.; Aller, Kimberly M.; Burgett, W. S.; Chambers, K. C.; Draper, P. W.; Hodapp, K. W.; Jedicke, R.; Kudritzki, R.-P.; Metcalfe, N.; Morgan, J. S.; Kaiser, N.; Price, P. A.; Tonry, J. L.; Wainscoat, R. J. (October 1, 2013). «The Extremely Red, Young L Dwarf PSO J318-22: A Free-Floating Planetary-Mass Analog to Directly Imaged Young Gas-Giant Planets». Astrophysical Journal Letters. 777 (2): L20. arXiv:1310.0457. Bibcode:2013ApJ…777L..20L. doi:10.1088/2041-8205/777/2/L20. S2CID 54007072. - ^ Andrew Norton (September 27, 2019). «Exoplanet discovery blurs the line between large planets and small stars». phys.org. Retrieved March 13, 2020.

- ^ a b Zimmer, Benjamin. «New planetary definition a «linguistic catastrophe»!». Language Log. Retrieved October 4, 2006.

- ^ «A Travel Guide to the Solar System». National Public Radio. 2006. Archived from the original on November 7, 2006. Retrieved November 18, 2006.

- ^ a b «Pluto’s Planethood: What Now?». Air and Space. 2006. Archived from the original on January 1, 2013. Retrieved August 21, 2007.

- ^ Soter, Steven (August 16, 2006). «What is a Planet?». The Astronomical Journal. 132 (6): 2513–2519. arXiv:astro-ph/0608359. Bibcode:2006AJ….132.2513S. doi:10.1086/508861. S2CID 14676169. submitted to The Astronomical Journal, August 16, 2006

- ^ Stern, S. Alan; Levison, Harold F. (2002). «Regarding the criteria for planethood and proposed planetary classification schemes» (PDF). Highlights of Astronomy. 12: 205–213, as presented at the XXIVth General Assembly of the IAU–2000 [Manchester, UK, August 7–18, 2000]. Bibcode:2002HiA….12..205S. doi:10.1017/S1539299600013289.

- ^ Righter, Kevin; Drake, Michael J. (1997). «A magma ocean on Vesta: Core formation and petrogenesis of eucrites and diogenites». Meteoritics & Planetary Science. 32 (6): 929–944. Bibcode:1997M&PS…32..929R. doi:10.1111/j.1945-5100.1997.tb01582.x. S2CID 128684062.

- ^ Johanna Torppa; Mikko Kaasalainen; Tadeusz Michałowski; Tomasz Kwiatkowski; Agnieszka Kryszczyńska; Peter Denchev; Richard Kowalski (2003). «Shapes and rotational properties of thirty asteroids from photometric data» (PDF). Astronomical Observatory, Adam Mickiewicz University. Retrieved May 25, 2006.

Bibliography and external links[edit]

- What is a planet? -Steven Soter

- Why Planets will never be defined: Robert Roy Britt on the outcome of the IAU’s decision

- Nunberg, Earth (August 28, 2006). «Dwarfing Pluto». NPR.org. NPR. Retrieved April 13, 2007. An examination of the redefinition of Pluto from a linguistic perspective.

- The Pluto Files by Neil deGrasse Tyson The Rise and Fall of America’s Favorite Planet

- Q&A New planets proposal Wednesday, August 16, 2006, 13:36 GMT 14:36 UK

- David Jewitt’s Kuiper Belt page- Pluto

- Dan Green’s webpage: What is a planet?

- What is a Planet? Debate Forces New Definition

- The Flap Over Pluto

- «You Call That a Planet?: How astronomers decide whether a celestial body measures up.»

- David Darling. The Universal Book of Astronomy, from the Andromeda Galaxy to the Zone of Avoidance. 2003. John Wiley & Sons Canada (ISBN 0-471-26569-1), p. 394

- Collins Dictionary of Astronomy, 2nd ed. 2000. HarperCollins Publishers (ISBN 0-00-710297-6), p. 312-4.

- Catalogue of Planetary Objects. Version 2006.0 O.V. Zakhozhay, V.A. Zakhozhay, Yu.N. Krugly, 2006

- The New Proposal, Resolution 5, 6 and 7 2006-08-22

- IAU 2006 General Assembly: video-records of the discussion and of the final vote on the Planet definition.

- Boyle, Alan, The Case for Pluto The Case for Pluto Book by MSNBC Science Editor and author of «Cosmic Log»

- Croswell, Dr. Ken «Pluto Question» Pluto Question

English[edit]

Etymology[edit]

From Middle English planete, from Old French planete, from Latin planeta, planetes, from Ancient Greek πλανήτης (planḗtēs, “wanderer”) (ellipsis of πλάνητες ἀστέρες (plánētes astéres, “wandering stars”).), from Ancient Greek πλανάω (planáō, “wander about, stray”), of unknown origin. Cognate with Latin pālor (“wander about, stray”), Old Norse flana (“to rush about”), and Norwegian flanta (“to wander about”). More at flaunt.

Perhaps it is from a nasalized form of Proto-Indo-European *pleh₂- (“flat, broad”) on the notion of «spread out», «but the semantics are highly problematic», according to Beekes, who notes the similarity of meaning to πλάζω (plázō, “to make devious, repel, dissuade from the right path, bewilder”), but adds, «it is hard to think of a formal connection».

So called because they have apparent motion, unlike the «fixed» stars. Originally including also the moon and sun but not the Earth; modern scientific sense of «world that orbits a star» is from 1630s in English. The Greek word is an enlarged form of πλάνης (plánēs, “who wanders around, wanderer”), also «wandering star, planet», in medicine «unstable temperature.»

Pronunciation[edit]

- (Received Pronunciation) IPA(key): /ˈplænɪt/

- (General American, General Australian) IPA(key): /ˈplænət/

-

- Rhymes: -ænɪt

Noun[edit]

planet (plural planets)

- (now historical or astrology) Each of the seven major bodies which move relative to the fixed stars in the night sky—the Moon, Mercury, Venus, the Sun, Mars, Jupiter and Saturn. [from 14thc.]

-

1603, Michel de Montaigne, chapter 12, in John Florio, transl., The Essayes […], book II, London: […] Val[entine] Simmes for Edward Blount […], →OCLC, page 260:

-

Be they not dreames of humane vanity, […] to make of our knowne earth a bright shining planet [translating astre]?

-

-

1749, Henry Fielding, Tom Jones, Folio Society, published 1973, page 288:

-

The moon […] began to rise from her bed, where she had slumbered away the day, in order to sit up all night. Jones had not travelled far before he paid his compliments to that beautiful planet, and, turning to his companion, asked him if he had ever beheld so delicious an evening?

-

-

1971, Keith Thomas, Religion and the Decline of Magic, Folio Society, published 2012, page 361:

-

Another of Boehme’s followers, the Welshman Morgan Llwyd, also believed that the seven planets could be found within man.

-

-

- (astronomy) A body which is massive enough to be in hydrostatic equilibrium (generally resulting in being an ellipsoid) but not enough to attain nuclear fusion and, in IAU usage, which directly orbits a star (or star cluster) and dominates the region of its orbit; specifically, in the case of the Solar system, the eight major bodies of Mercury, Venus, Earth, Mars, Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune. [from 2006]

- Synonyms: wandering star, wanderstar

- Hypernym: planemo (in IAU usage)

- Hyponyms: binary planet, Blue Planet, carbide planet, carbon planet, classical planet, diamond planet, double planet, dual planet, dwarf planet (in non-IAU usage), exoplanet, extrasolar planet, free-floating planet (in non-IAU usage), gas giant, giant planet, hycean planet, ice giant, inferior planet, inner planet, interstellar planet (in non-IAU usage), major planet, mesoplanet, minor planet (in non-IAU usage), outer planet, Planet Earth, primary planet (in non-IAU usage), Red Planet, rogue planet (in non-IAU usage), satellite planet (in non-IAU usage), silicate planet, silicon planet, supergiant planet, superior planet, superplanet, terrestrial planet, water planet

- Coordinate terms: brown dwarf, sub-brown dwarf

-

1640, John Wilkins, A Discovrse concerning a New Planet. Tending to prove, That ’tis probable our Earth is one of the Planets, title:

-

A Discovrse concerning a New Planet. Tending to prove, That ’tis probable our Earth is one of the Planets

-

-

2006 December 22, Alok Jha, The Guardian:

-

Their decision will force a rewrite of science textbooks because the solar system is now a place with eight planets and three newly defined «dwarf planets«—a new category of object that includes Pluto.

-

-

2009 December 1st, Wada, Keiichi; Tsukamoto, Yusuke; Kokubo, Eiichiro, “Planet Formation around Supermassive Black Holes in the Active Galactic Nuclei”, in The Astrophysical Journal, volume 886, number 2, article 107:

- construed with the or this: synonym of Earth.

-

1907 August, Robert W[illiam] Chambers, chapter VIII, in The Younger Set, New York, N.Y.: D. Appleton & Company, →OCLC:

-

«My tastes,» he said, still smiling, «incline me to the garishly sunlit side of this planet.» And, to tease her and arouse her to combat: «I prefer a farandole to a nocturne; I’d rather have a painting than an etching; Mr. Whistler bores me with his monochromatic mud; I don’t like dull colours, dull sounds, dull intellects; […].»

-

-

2013 June 7, David Simpson, “Fantasy of navigation”, in The Guardian Weekly, volume 188, number 26, page 36:

-

It is tempting to speculate about the incentives or compulsions that might explain why anyone would take to the skies in [the] basket [of a balloon]: […]; perhaps to moralise on the oneness or fragility of the planet, or to see humanity for the small and circumscribed thing that it is; […].

-

-

Usage notes[edit]

The term planet originally meant any star which wandered across the sky, and generally included comets and the Sun and Moon. With the Copernican revolution, the Earth was recognized as a planet, and the Sun was seen to be fundamentally different. The Galilean satellites of Jupiter were at first called planets (satellite planets), but later reclassified along with the Moon. The first asteroids were also considered to be planets, but were reclassified when it was realized that there were a great many of them, crossing each other’s orbits, in a zone where only a single planet had been expected. Likewise, Pluto was found where an outer planet had been expected, but doubts were raised when it turned out to cross Neptune’s orbit and to be much smaller than the expectation required. When Eris, an outer body more massive than Pluto, was discovered, the International Astronomical Union (IAU) officially defined the word planet as above. However, a significant number of astronomers reject the IAU definition, especially in the field of planetary geology. Some are of the opinion that orbital parameters should be irrelevant, and that either any equilibrium (ellipsoidal) body in direct orbit around a star is a planet (there are likely at least a dozen such bodies in the Solar system) or that any equilibrium body at all is a planet, thus re-accepting the Moon, the Galilean satellites and other large moons as planets, as well as rogue planets.

Hypernyms[edit]

- planemo

Hyponyms[edit]

- dwarf planet

- exoplanet

- gas giant

- ice giant

- ice planet

- minor planet

- protoplanet

- terrestrial planet

Derived terms[edit]

- interplanetary

- planet-hunting

- planetar

- planetarium

- planetary

- planetesimal

- planetoid

[edit]

- planet-ruler

- planet-struck

- planetary body

- planetary object

- planetary-mass object

Translations[edit]

each of the seven major bodies which move relative to the fixed stars in the night sky

- Abkhaz: апланета (apʼlanetʼa)

- Adyghe: планет (plaaneet)

- Afrikaans: planeet (af)

- Albanian: planet (sq) m

- Amharic: ፕላኔት (pəlanet)

- Arabic: كَوْكَب سَيَّار m (kawkab sayyār), كَوْكَب (ar) m (kawkab)

- Egyptian Arabic: كوكب m (kawkab)

- Hijazi Arabic: كَوْكَب m (kawkab)

- Aragonese: planeta

- Armenian: մոլորակ (hy) (molorak)

- Assamese: গ্ৰহ (groh)

- Asturian: planeta (ast) m

- Azerbaijani: planet (az), səyyarə

- Banyumasan: planet

- Bashkir: планета (planeta)

- Basque: planeta (eu)

- Belarusian: плане́та f (planjéta), плянэ́та f (pljanéta) (Taraškievica)

- Bengali: গ্রহ (groho)

- Bulgarian: плане́та (bg) f (planéta)

- Burmese: ဂြိုဟ် (my) (gruih)

- Catalan: planeta (ca) m

- Chechen: планета (planeta)

- Chinese:

- Cantonese: 行星 (hang4 sing1, haang4 sing1)

- Mandarin: 行星 (zh) (xíngxīng)

- Min Nan: 行星 (zh-min-nan) (hêng-chhiⁿ, hêng-chheⁿ, hêng-seng)

- Chuvash: планета (planet̬a)

- Coptic: ⲫⲱⲥⲧⲏⲣ m (phōstēr)

- Cornish: planet

- Czech: planeta (cs) f

- Danish: planet (da) c

- Dutch: planeet (nl) f

- English:

- Old English: tungol m

- Esperanto: planedo (eo)

- Estonian: planeet (et)

- Extremaduran: praneta

- Faroese: gongustjørna f

- Fiji Hindi: grah

- Finnish: planeetta (fi)

- Franco-Provençal: planèta

- French: planète (fr) f

- Frisian:

- North Frisian: planeete

- West Frisian: planeet (fy) c

- Friulian: planet

- Galician: planeta (gl) m

- Georgian: პლანეტა (ṗlaneṭa), ცთომილი (ctomili)

- German: Planet (de) m, Wandelstern (de) m (old)

- Rhine Franconian: planed (Palatine)

- Greek: πλανήτης (el) m (planítis)

- Ancient: πλανήτης m (planḗtēs)

- Guaraní: mbyjajere

- Gujarati: ગ્રહ m (grah)

- Haitian Creole: planèt

- Hawaiian: hōkū hele

- Hebrew: כּוֹכַב לֶכֶת (he) m (kokháv lékhet)

- Hindi: ग्रह (hi) m (grah)

- Hungarian: bolygó (hu), (dated) planéta (hu)

- Icelandic: reikistjarna (is) f

- Ido: planeto (io)

- Ilocano: planeta

- Indonesian: planet (id), bintang siarah (id)

- Interlingua: planeta

- Irish: pláinéad (ga) m

- Italian: pianeta (it) m

- Japanese: 惑星 (ja) (わくせい, wakusei), プラネット (puranetto), 迷い星 (まよいぼし, mayoiboshi), 星 (ja) (ほし, hoshi)

- Javanese: planèt

- Kabardian: планетэ (plaaneete)

- Kannada: ಗ್ರಹ (kn) (graha)

- Kapampangan: planeta

- Karakalpak: planeta

- Kazakh: ғаламшар (ğalamşar), планета (kk) (planeta)

- Khmer: ផ្កាយព្រះគ្រោះ (phkaay prĕəh krŭəh), ផ្កាយ (km) (phkaay)

- Kongo: mweta

- Korean: 행성(行星) (ko) (haengseong), 유성(遊星) (ko) (yuseong)

- Kurdish:

- Central Kurdish: هەسارە (ckb) (hesare)

- Northern Kurdish: gerstêrk (ku), hesare (ku), exter (ku)

- Kyrgyz: планета (planeta)

- Lao: ດາວເຄາະ (lo) (dāo khǫ), ເຄາະ (khǫ), ດາວ (lo) (dāo)

- Latin: planēta (la) m, planētēs m, stella errans, stella vaga

- Latvian: planēta f

- Limburgish: planeet (li)

- Lingala: monzɔ́tɔ mwa malíli

- Lithuanian: planeta (lt) f

- Low German:

- Dutch Low Saxon: planeet

- German Low German: Planet (nds) m

- Luxembourgish: planéit

- Macedonian: плане́та f (planéta)

- Malagasy: fajiry (mg)

- Malay: planet (ms), bintang siarah, bintang beredar

- Malayalam: ഗ്രഹം (ml) (grahaṃ)

- Maltese: pjaneta f

- Manx: planaid

- Maori: whetūao, whetū mārama, aorangi (mi)

- Marathi: ग्रह m (grah)

- Minangkabau: planet

- Mirandese: planeta

- Mongolian:

- Cyrillic: гариг (mn) (garig), гараг (mn) (garag)

- Mongolian: ᠭᠠᠷᠠᠭ (ɣarag)

- Nahuatl: nehnencācītlalli

- Narom: plianète

- Neapolitan: chianéta m

- Nepali: ग्रह (ne) (graha)

- Norman: plianète f (Jersey)

- Norwegian:

- Bokmål: planet (no) m, klode m

- Nynorsk: planet (nn) m, klode m

- Occitan: planeta (oc) f

- Old Church Slavonic:

- Cyrillic: планита f (planita), планитъ m (planitŭ)

- Oriya: ଗ୍ରହ (or) (grôhô)

- Ossetian: планетӕ (planetæ)

- Pashto: سياره (ps) f (sayāra)

- Persian: سیاره (fa) (sayyâre), اختر (fa) (axtar) (archaic), اباختر (fa) (abâxtar), هرباسپ (harbâsp), هرباسب (harbâsb)

- Middle Persian: 𐭠𐭧𐭲𐭥𐭠𐭯 (abāxtar)

- Picard: planète

- Piedmontese: pianeta

- Pitcairn-Norfolk: plaanet

- Polish: planeta (pl) f

- Portuguese: planeta (pt) m

- Punjabi: ਗ੍ਰਹਿ m (grhi), ਨਛੱਤਰ m (nachattar)

- Quechua: puriq quyllur

- Romanian: planetă (ro) f

- Romansch: planet m

- Russian: плане́та (ru) f (planéta)

- Sami:

- Northern Sami: planehta

- Sanskrit: ग्रह (sa) m (graha)

- Saterland Frisian: planet

- Scots: planet

- Scottish Gaelic: planaid

- Serbo-Croatian:

- Cyrillic: плане́та f, пла̀не̄т m

- Roman: planéta (sh) f, plànēt (sh) m

- Shona: chindeya

- Sicilian: pianeta

- Silesian: planeta

- Sinhalese: ග්රහ (graha)

- Slovak: planéta (sk) f

- Slovene: planet (sl) m

- Spanish: planeta (es) m

- Sundanese: planét

- Swahili: sayari (sw)

- Swedish: planet (sv) c

- Tagalog: planeta (tl), buntala

- Tajik: сайёра (sayyora), кавкаб (kavkab)

- Tamil: கிரகம் (ta) (kirakam)

- Tatar: планета (planeta)

- Crimean Tatar: seyyare, planeta

- Telugu: గ్రహము (te) (grahamu)

- Tetum: planeta

- Thai: ดาวนพเคราะห์ (th), ดาวเคราะห์ (th) (daao-krɔ́), เคราะห์ (th) (krɔ́), ดาว (th) (daao)

- Tibetan: གཟའ (gza’), གཟའ་སྐར (gza’ skar)

- Tigrinya: ፕላነት (pəlanät)

- Tok Pisin: planet (tpi)

- Turkish: gezegen (tr), planet (tr) (rare), seyyare (tr) (archaic)

- Ottoman Turkish: سیاره (seyyâre)

- Turkmen: planeta

- Ukrainian: плане́та (uk) f (planéta)