Innovation is the practical implementation of ideas that result in the introduction of new goods or services or improvement in offering goods or services.[1] ISO TC 279 in the standard ISO 56000:2020 [2] defines innovation as «a new or changed entity realizing or redistributing value». Others have different definitions; a common element in the definitions is a focus on newness, improvement, and spread of ideas or technologies.

Innovation often takes place through the development of more-effective products, processes, services, technologies, art works[3]

or business models that innovators make available to markets, governments and society. Innovation is related to, but not the same as, invention:[4] innovation is more apt to involve the practical implementation of an invention (i.e. new / improved ability) to make a meaningful impact in a market or society,[5] and not all innovations require a new invention.[6]

Technical innovation often manifests itself via the engineering process when the problem being solved is of a technical or scientific nature. The opposite of innovation is exnovation.

DefinitionEdit

Surveys of the literature on innovation have found a variety of definitions. In 2009, Baregheh et al. found around 60 definitions in different scientific papers, while a 2014 survey found over 40.[7] Based on their survey, Baragheh et al. attempted to define a multidisciplinary definition and arrived at the following definition:

«Innovation is the multi-stage process whereby organizations transform ideas into new/improved products, service or processes, in order to advance, compete and differentiate themselves successfully in their marketplace»[8]

In an industrial survey of how the software industry defined innovation, the following definition given by Crossan and Apaydin was considered to be the most complete, which builds on the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) manual’s definition:[7]

Innovation is production or adoption, assimilation, and exploitation of a value-added novelty in economic and social spheres; renewal and enlargement of products, services, and markets; development of new methods of production; and the establishment of new management systems. It is both a process and an outcome.

American sociologist Everett Rogers, defined it as follows:

«An idea, practice, or object that is perceived as new by an individual or other unit of adoption»[9]

According to Alan Altshuler and Robert D. Behn, innovation includes original invention and creative use and defines innovation as a generation, admission and realization of new ideas, products, services and processes.[10]

Two main dimensions of innovation are degree of novelty (i.e. whether an innovation is new to the firm, new to the market, new to the industry, or new to the world) and kind of innovation (i.e. whether it is process or product-service system innovation).[7] In organizational scholarship, researchers have also distinguished innovation to be separate from creativity, by providing an updated definition of these two related constructs:

Workplace creativity concerns the cognitive and behavioral processes applied when attempting to generate novel ideas. Workplace innovation concerns the processes applied when attempting to implement new ideas. Specifically, innovation involves some combination of problem/opportunity identification, the introduction, adoption or modification of new ideas germane to organizational needs, the promotion of these ideas, and the practical implementation of these ideas.[11]

Peter Drucker wrote:

Innovation is the specific function of entrepreneurship, whether in an existing business, a public service institution, or a new venture started by a lone individual in the family kitchen. It is the means by which the entrepreneur either creates new wealth-producing resources or endows existing resources with enhanced potential for creating wealth.[12]

Creativity and innovationEdit

In general, innovation is distinguished from creativity by its emphasis on the implementation of creative ideas in an economic setting. Amabile and Pratt in 2016, drawing on the literature, distinguish between creativity («the production of novel and useful ideas by an individual or small group of individuals working together») and innovation («the successful implementation of creative ideas within an organization»).[13]

TypesEdit

Several frameworks have been proposed for defining types of innovation.[14][15]

Sustaining vs disruptive innovationEdit

One framework proposed by Clayton Christensen draws a distinction between sustaining and disruptive innovations.[16] Sustaining innovation is the improvement of a product or service based on the known needs of current customers (e.g. faster microprocessors, flat screen televisions). Disruptive innovation in contrast refers to a process by which a new product or service creates a new market (e.g. transistor radio, free crowdsourced encyclopedia, etc.), eventually displacing established competitors.[17][18] According to Christensen, disruptive innovations are critical to long-term success in business.[19]

Disruptive innovation is often enabled by disruptive technology. Marco Iansiti and Karim R. Lakhani define foundational technology as having the potential to create new foundations for global technology systems over the longer term. Foundational technology tends to transform business operating models as entirely new business models emerge over many years, with gradual and steady adoption of the innovation leading to waves of technological and institutional change that gain momentum more slowly.[20][additional citation(s) needed] The advent of the packet-switched communication protocol TCP/IP—originally introduced in 1972 to support a single use case for United States Department of Defense electronic communication (email), and which gained widespread adoption only in the mid-1990s with the advent of the World Wide Web—is a foundational technology.[20]

Four types innovation modelEdit

Another framework was suggested by Henderson and Clark. They divide innovation into four types;

- Radical innovation: «establishes a new dominant design and, hence, a new set of core design concepts embodied in components that are linked together in a new architecture.» (p. 11)[21]

- Incremental innovation: «refines and extends an established design. Improvement occurs in individual components, but the underlying core design concepts, and the links between them, remain the same.» (p. 11)[21]

- Architectural innovation: «innovation that changes only the relationships between them [the core design concepts]» (p. 12)[21]

- Modular Innovation: «innovation that changes only the core design concepts of a technology» (p. 12)[21]

While Henderson and Clark as well as Christensen talk about technical innovation there are other kinds of innovation as well, such as service innovation and organizational innovation.

Non-economic innovationEdit

The classical definition of innovation being limited to the primary goal of generating profit for a firm, has led others to define other types of innovation such as: social innovation, sustainable innovation (or green innovation), and responsible innovation.[22][23]

HistoryEdit

The word «innovation» once had a quite different meaning. The first full-length discussion about innovation is the account[which?] by the Greek philosopher and historian Xenophon (430–355 BCE). He viewed the concept as multifaceted and connected it to political action. The word for innovation that he uses, ‘kainotomia’, had previously occurred in two plays by Aristophanes (c. 446 – c. 386 BCE). Plato (died c. 348 BCE) discussed innovation in his Laws dialogue and was not very fond of the concept. He was skeptical to it both in culture (dancing and art) and in education (he did not believe in introducing new games and toys to the kids).[24] Aristotle (384–322 BCE) did not like organizational innovations: he believed that all possible forms of organization had been discovered.[25]

Before the 4th century in Rome, the words novitas and res nova / nova res were used with either negative or positive judgment on the innovator. This concept meant «renewing» and was incorporated into the new Latin verb word innovo («I renew» or «I restore») in the centuries that followed. The Vulgate version of the Bible (late 4th century CE) used the word in spiritual as well as political contexts. It also appeared in poetry, mainly with spiritual connotations, but was also connected to political, material and cultural aspects.[24]

Machiavelli’s The Prince (1513), discusses innovation in a political setting. Machiavelli portrays it as a strategy a Prince may employ in order to cope with a constantly changing world as well as the corruption within it. Here innovation is described as introducing change in government (new laws and institutions); Machiavelli’s later book The Discourses (1528) characterises innovation as imitation, as a return to the original that has been corrupted by people and by time.[citation needed] Thus for Machiavelli innovation came with positive connotations. This is however an exception in the usage of the concept of innovation from the 16th century and onward. No innovator from the renaissance until the late 19th century ever thought of applying the word innovator upon themselves, it was a word used to attack enemies.[24]

From the 1400s[citation needed] through the 1600s, the concept of innovation was pejorative – the term was an early-modern synonym for «rebellion», «revolt» and «heresy».[26][27][28][29][30] In the 1800s[timeframe?] people promoting capitalism saw socialism as an innovation and spent a lot of energy working against it. For instance, Goldwin Smith (1823-1910) saw the spread of social innovations as an attack on money and banks. These social innovations were socialism, communism, nationalization, cooperative associations.[24]

In the 20th century the concept of innovation did not become popular until after the Second World War of 1939-1945. This is the point in time when people started to talk about technological product innovation and tie it to the idea of economic growth and competitive advantage.[31] Joseph Schumpeter (1883–1950) is often[quantify] credited as the one who made the term popular — he contributed greatly to the study of innovation economics,

In business and in economics, innovation can provide a catalyst for growth in an enterprise or even in an industry. With rapid advances in transportation and communications over the past few decades, the old concepts of factor endowments and comparative advantage which focused on an area’s unique inputs are outmoded in today’s global economy.[citation needed] Schumpeter argued that industries must incessantly revolutionize the economic structure from within, that is: innovate with better or more effective processes and products, as well as with market distribution (such as the transition from the craft shop to factory). He famously asserted that «creative destruction is the essential fact about capitalism».[32] Entrepreneurs continuously search for better ways to satisfy their consumer base with improved quality, durability, service and price — searches which may come to fruition in innovation with advanced technologies and organizational strategies.[33]

A prime example of innovation involved the boom of Silicon Valley start-ups out of the Stanford Industrial Park. In 1957, dissatisfied employees of Shockley Semiconductor, the company of Nobel laureate and co-inventor of the transistor William Shockley, left to form an independent firm, Fairchild Semiconductor. After several years, Fairchild developed into a formidable presence in the sector.[which?] Eventually, these founders left to start their own companies based on their own unique ideas, and then leading employees started their own firms. Over the next 20 years this process resulted in the momentous startup-company explosion of information-technology firms.[citation needed] Silicon Valley began as 65 new enterprises born out of Shockley’s eight former employees.[34]

Another example involves business incubators – a phenomenon introduced in 1959 and subsequently nurtured by governments around the world. Such «incubators», located close to knowledge clusters (mostly research-based) like universities or other government excellence centres – aim primarily to channel generated knowledge to applied innovation outcomes in order to stimulate regional or national economic growth.[35]

In the 21st century the Islamic State (IS) movement, while decrying religious innovations, has innovated in military tactics, recruitment, ideology and geopolitical activity.[36][37]

Process of innovationEdit

An early model included only three phases of innovation. According to Utterback (1971), these phases were: 1) idea generation, 2) problem solving, and 3) implementation.[38] By the time one completed phase 2, one had an invention, but until one got it to the point of having an economic impact, one didn’t have an innovation. Diffusion wasn’t considered a phase of innovation. Focus at this point in time was on manufacturing.

All organizations can innovate, including for example hospitals, universities, and local governments.[39] The organization requires a proper structure in order to retain competitive advantage. Organizations can also improve profits and performance by providing work groups opportunities and resources to innovate, in addition to employee’s core job tasks.[40] Executives and managers have been advised to break away from traditional ways of thinking and use change to their advantage.[41] The world of work is changing with the increased use of technology and companies are becoming increasingly competitive. Companies will have to downsize or reengineer their operations to remain competitive. This will affect employment as businesses will be forced to reduce the number of people employed while accomplishing the same amount of work if not more.[42]

For instance, former Mayor Martin O’Malley pushed the City of Baltimore to use CitiStat, a performance-measurement data and management system that allows city officials to maintain statistics on several areas from crime trends to the conditions of potholes. This system aided in better evaluation of policies and procedures with accountability and efficiency in terms of time and money. In its first year, CitiStat saved the city $13.2 million.[43] Even mass transit systems have innovated with hybrid bus fleets to real-time tracking at bus stands. In addition, the growing use of mobile data terminals in vehicles, that serve as communication hubs between vehicles and a control center, automatically send data on location, passenger counts, engine performance, mileage and other information. This tool helps to deliver and manage transportation systems.[44]

Still other innovative strategies include hospitals digitizing medical information in electronic medical records. For example, the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development’s HOPE VI initiatives turned severely distressed public housing in urban areas into revitalized, mixed-income environments; the Harlem Children’s Zone used a community-based approach to educate local area children; and the Environmental Protection Agency’s brownfield grants facilitates turning over brownfields for environmental protection, green spaces, community and commercial development.

Sources of innovationEdit

Innovation may occur due to effort from a range of different agents, by chance, or as a result of a major system failure. According to Peter F. Drucker, the general sources of innovations are changes in industry structure, in market structure, in local and global demographics, in human perception, in the amount of available scientific knowledge, etc.[12]

Original model of three phases of the process of Technological Change

In the simplest linear model of innovation the traditionally recognized source is manufacturer innovation. This is where an agent (person or business) innovates in order to sell the innovation. Specifically, R&D measurement is the commonly used input for innovation, in particular in the business sector, named Business Expenditure on R&D (BERD) that grew over the years on the expenses of the declining R&D invested by the public sector.[45]

Another source of innovation, only now becoming widely recognized, is end-user innovation. This is where an agent (person or company) develops an innovation for their own (personal or in-house) use because existing products do not meet their needs. MIT economist Eric von Hippel has identified end-user innovation as, by far, the most important and critical in his classic book on the subject, «The Sources of Innovation».[46]

The robotics engineer Joseph F. Engelberger asserts that innovations require only three things:

- a recognized need

- competent people with relevant technology

- financial support[47]

The Kline chain-linked model of innovation[48] places emphasis on potential market needs as drivers of the innovation process, and describes the complex and often iterative feedback loops between marketing, design, manufacturing, and R&D.

Facilitating innovationEdit

Innovation by businesses is achieved in many ways, with much attention now given to formal research and development (R&D) for «breakthrough innovations». R&D help spur on patents and other scientific innovations that leads to productive growth in such areas as industry, medicine, engineering, and government.[49] Yet, innovations can be developed by less formal on-the-job modifications of practice, through exchange and combination of professional experience and by many other routes. Investigation of relationship between the concepts of innovation and technology transfer revealed overlap.[50] The more radical and revolutionary innovations tend to emerge from R&D, while more incremental innovations may emerge from practice – but there are many exceptions to each of these trends.

Information technology and changing business processes and management style can produce a work climate favorable to innovation.[51] For example, the software tool company Atlassian conducts quarterly «ShipIt Days» in which employees may work on anything related to the company’s products.[52] Google employees work on self-directed projects for 20% of their time (known as Innovation Time Off). Both companies cite these bottom-up processes as major sources for new products and features.

An important innovation factor includes customers buying products or using services. As a result, organizations may incorporate users in focus groups (user centered approach), work closely with so-called lead users (lead user approach), or users might adapt their products themselves. The lead user method focuses on idea generation based on leading users to develop breakthrough innovations. U-STIR, a project to innovate Europe’s surface transportation system, employs such workshops.[53] Regarding this user innovation, a great deal of innovation is done by those actually implementing and using technologies and products as part of their normal activities. Sometimes user-innovators may become entrepreneurs, selling their product, they may choose to trade their innovation in exchange for other innovations, or they may be adopted by their suppliers. Nowadays, they may also choose to freely reveal their innovations, using methods like open source. In such networks of innovation the users or communities of users can further develop technologies and reinvent their social meaning.[54][55]

One technique for innovating a solution to an identified problem is to actually attempt an experiment with many possible solutions.[56] This technique was famously used by Thomas Edison’s laboratory to find a version of the incandescent light bulb economically viable for home use, which involved searching through thousands of possible filament designs before settling on carbonized bamboo.

This technique is sometimes used in pharmaceutical drug discovery. Thousands of chemical compounds are subjected to high-throughput screening to see if they have any activity against a target molecule which has been identified as biologically significant to a disease. Promising compounds can then be studied; modified to improve efficacy and reduce side effects, evaluated for cost of manufacture; and if successful turned into treatments.

The related technique of A/B testing is often used to help optimize the design of web sites and mobile apps. This is used by major sites such as amazon.com, Facebook, Google, and Netflix.[57] Procter & Gamble uses computer-simulated products and online user panels to conduct larger numbers of experiments to guide the design, packaging, and shelf placement of consumer products.[58] Capital One uses this technique to drive credit card marketing offers.[57]

Goals and failuresEdit

Programs of organizational innovation are typically tightly linked to organizational goals and growth objectives, to the business plan, and to market competitive positioning. Davila et al. (2006) note, «Companies cannot grow through cost reduction and reengineering alone… Innovation is the key element in providing aggressive top-line growth, and for increasing bottom-line results».[59]

One survey across a large number of manufacturing and services organizations found that systematic programs of organizational innovation are most frequently driven by: improved quality, creation of new markets, extension of the product range, reduced labor costs, improved production processes, reduced materials cost, reduced environmental damage, replacement of products/services, reduced energy consumption, and conformance to regulations.[59]

Different goals are appropriate for different products, processes, and services. According to Andrea Vaona and Mario Pianta, some example goals of innovation could stem from two different types of technological strategies: technological competitiveness and active price competitiveness. Technological competitiveness may have a tendency to be pursued by smaller firms and can be characterized as «efforts for market-oriented innovation, such as a strategy of market expansion and patenting activity.»[60] On the other hand, active price competitiveness is geared toward process innovations that lead to efficiency and flexibility, which tend to be pursued by large, established firms as they seek to expand their market foothold.[60] Whether innovation goals are successfully achieved or otherwise depends greatly on the environment prevailing in the organization.[61]

Failure of organizational innovation programs has been widely researched and the causes vary considerably. Some causes are external to the organization and outside its influence of control. Others are internal and ultimately within the control of the organization. Internal causes of failure can be divided into causes associated with the cultural infrastructure and causes associated with the innovation process itself. David O’Sullivan wrote that causes of failure within the innovation process in most organizations can be distilled into five types: poor goal definition, poor alignment of actions to goals, poor participation in teams, poor monitoring of results, and poor communication and access to information.[62]

DiffusionEdit

Diffusion of innovation research was first started in 1903 by seminal researcher Gabriel Tarde, who first plotted the S-shaped diffusion curve. Tarde defined the innovation-decision process as a series of steps that include:[63]

- knowledge

- forming an attitude

- a decision to adopt or reject

- implementation and use

- confirmation of the decision

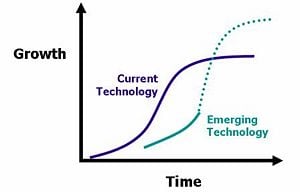

Once innovation occurs, innovations may be spread from the innovator to other individuals and groups. This process has been proposed that the lifecycle of innovations can be described using the ‘s-curve’ or diffusion curve. The s-curve maps growth of revenue or productivity against time. In the early stage of a particular innovation, growth is relatively slow as the new product establishes itself. At some point, customers begin to demand and the product growth increases more rapidly. New incremental innovations or changes to the product allow growth to continue. Towards the end of its lifecycle, growth slows and may even begin to decline. In the later stages, no amount of new investment in that product will yield a normal rate of return.

The s-curve derives from an assumption that new products are likely to have «product life» – i.e., a start-up phase, a rapid increase in revenue and eventual decline. In fact, the great majority of innovations never get off the bottom of the curve, and never produce normal returns.

Innovative companies will typically be working on new innovations that will eventually replace older ones. Successive s-curves will come along to replace older ones and continue to drive growth upwards. In the figure above the first curve shows a current technology. The second shows an emerging technology that currently yields lower growth but will eventually overtake current technology and lead to even greater levels of growth. The length of life will depend on many factors.[64]

MeasuresEdit

Measuring innovation is inherently difficult as it implies commensurability so that comparisons can be made in quantitative terms. Innovation, however, is by definition novelty. Comparisons are thus often meaningless across products or service.[65] Nevertheless, Edison et al.[66] in their review of literature on innovation management found 232 innovation metrics. They categorized these measures along five dimensions; i.e. inputs to the innovation process, output from the innovation process, effect of the innovation output, measures to access the activities in an innovation process and availability of factors that facilitate such a process.[66]

There are two different types of measures for innovation: the organizational level and the political level.

Organizational-levelEdit

- The measure of innovation at the organizational level relates to individuals, team-level assessments, and private companies from the smallest to the largest company. Measure of innovation for organizations can be conducted by surveys, workshops, consultants, or internal benchmarking. There is today no established general way to measure organizational innovation. Corporate measurements are generally structured around balanced scorecards which cover several aspects of innovation such as business measures related to finances, innovation process efficiency, employees’ contribution and motivation, as well benefits for customers. Measured values will vary widely between businesses, covering for example new product revenue, spending in R&D, time to market, customer and employee perception & satisfaction, number of patents, additional sales resulting from past innovations.[67]

Political-levelEdit

- For the political level, measures of innovation are more focused on a country or region competitive advantage through innovation. In this context, organizational capabilities can be evaluated through various evaluation frameworks, such as those of the European Foundation for Quality Management. The OECD Oslo Manual (1992) suggests standard guidelines on measuring technological product and process innovation. Some people consider the Oslo Manual complementary to the Frascati Manual from 1963. The new Oslo Manual from 2018 takes a wider perspective to innovation, and includes marketing and organizational innovation. These standards are used for example in the European Community Innovation Surveys.[68]

Other ways of measuring innovation have traditionally been expenditure, for example, investment in R&D (Research and Development) as percentage of GNP (Gross National Product). Whether this is a good measurement of innovation has been widely discussed and the Oslo Manual has incorporated some of the critique against earlier methods of measuring. The traditional methods of measuring still inform many policy decisions. The EU Lisbon Strategy has set as a goal that their average expenditure on R&D should be 3% of GDP.[69]

IndicatorsEdit

Many scholars claim that there is a great bias towards the «science and technology mode» (S&T-mode or STI-mode), while the «learning by doing, using and interacting mode» (DUI-mode) is ignored and measurements and research about it rarely done. For example, an institution may be high tech with the latest equipment, but lacks crucial doing, using and interacting tasks important for innovation.[70]

A common industry view (unsupported by empirical evidence) is that comparative cost-effectiveness research is a form of price control which reduces returns to industry, and thus limits R&D expenditure, stifles future innovation and compromises new products access to markets.[71]

Some academics claim cost-effectiveness research is a valuable value-based measure of innovation which accords «truly significant» therapeutic advances (i.e. providing «health gain») higher prices than free market mechanisms.[72] Such value-based pricing has been viewed as a means of indicating to industry the type of innovation that should be rewarded from the public purse.[73]

An Australian academic developed the case that national comparative cost-effectiveness analysis systems should be viewed as measuring «health innovation» as an evidence-based policy concept for valuing innovation distinct from valuing through competitive markets, a method which requires strong anti-trust laws to be effective, on the basis that both methods of assessing pharmaceutical innovations are mentioned in annex 2C.1 of the Australia-United States Free Trade Agreement.[74][75][76]

IndicesEdit

Several indices attempt to measure innovation and rank entities based on these measures, such as:

- Bloomberg Innovation Index

- «Bogota Manual»[77] similar to the Oslo Manual, is focused on Latin America and the Caribbean countries.[citation needed]

- «Creative Class» developed by Richard Florida[citation needed]

- EIU Innovation Ranking[78]

- Global Competitiveness Report

- Global Innovation Index (GII), by INSEAD[79]

- Information Technology and Innovation Foundation (ITIF) Index

- Innovation 360 – From the World Bank. Aggregates innovation indicators (and more) from a number of different public sources

- Innovation Capacity Index (ICI) published by a large number of international professors working in a collaborative fashion. The top scorers of ICI 2009–2010 were: 1. Sweden 82.2; 2. Finland 77.8; and 3. United States 77.5[80]

- Innovation Index, developed by the Indiana Business Research Center, to measure innovation capacity at the county or regional level in the United States[81]

- Innovation Union Scoreboard, developed by the European Union

- innovationsindikator for Germany, developed by the Federation of German Industries (Bundesverband der Deutschen Industrie) in 2005[82]

- INSEAD Innovation Efficacy Index[83]

- International Innovation Index, produced jointly by The Boston Consulting Group, the National Association of Manufacturers (NAM) and its nonpartisan research affiliate The Manufacturing Institute, is a worldwide index measuring the level of innovation in a country; NAM describes it as the «largest and most comprehensive global index of its kind»[citation needed][84]

- Management Innovation Index – Model for Managing Intangibility of Organizational Creativity: Management Innovation Index[85]

- NYCEDC Innovation Index, by the New York City Economic Development Corporation, tracks New York City’s «transformation into a center for high-tech innovation. It measures innovation in the City’s growing science and technology industries and is designed to capture the effect of innovation on the City’s economy»[86]

- OECD Oslo Manual is focused on North America, Europe, and other rich economies

- State Technology and Science Index, developed by the Milken Institute, is a U.S.-wide benchmark to measure the science and technology capabilities that furnish high paying jobs based around key components[87]

- World Competitiveness Scoreboard[88]

RankingsEdit

Common areas of focus include: high-tech companies, manufacturing, patents, post secondary education, research and development, and research personnel. The left ranking of the top 10 countries below is based on the 2020 Bloomberg Innovation Index.[89] However, studies may vary widely; for example the Global Innovation Index 2016 ranks Switzerland as number one wherein countries like South Korea, Japan, and China do not even make the top ten.[90]

Rate of innovationEdit

In 2005 Jonathan Huebner, a physicist working at the Pentagon’s Naval Air Warfare Center, argued on the basis of both U.S. patents and world technological breakthroughs, per capita, that the rate of human technological innovation peaked in 1873 and has been slowing ever since.[94][95] In his article, he asked «Will the level of technology reach a maximum and then decline as in the Dark Ages?»[94] In later comments to New Scientist magazine, Huebner clarified that while he believed that we will reach a rate of innovation in 2024 equivalent to that of the Dark Ages, he was not predicting the reoccurrence of the Dark Ages themselves.[96]

John Smart criticized the claim and asserted that technological singularity researcher Ray Kurzweil and others showed a «clear trend of acceleration, not deceleration» when it came to innovations.[97] The foundation replied to Huebner the journal his article was published in, citing Second Life and eHarmony as proof of accelerating innovation; to which Huebner replied.[98]

However, Huebner’s findings were confirmed in 2010 with U.S. Patent Office data.[99] and in a 2012 paper.[100]

Innovation and developmentEdit

The theme of innovation as a tool to disrupting patterns of poverty has gained momentum since the mid-2000s among major international development actors such as DFID,[101] Gates Foundation’s use of the Grand Challenge funding model,[102] and USAID’s Global Development Lab.[103] Networks have been established to support innovation in development, such as D-Lab at MIT.[104] Investment funds have been established to identify and catalyze innovations in developing countries, such as DFID’s Global Innovation Fund,[105] Human Development Innovation Fund,[106] and (in partnership with USAID) the Global Development Innovation Ventures.[107]

The United States has to continue to play on the same level of playing field as its competitors in federal research. This can be achieved being strategically innovative through investment in basic research and science».[108]

Government policiesEdit

Given its effects on efficiency, quality of life, and productive growth, innovation is a key driver in improving society and economy. Consequently, policymakers have worked to develop environments that will foster innovation, from funding research and development to establishing regulations that do not inhibit innovation, funding the development of innovation clusters, and using public purchasing and standardisation to ‘pull’ innovation through.

For instance, experts are advocating that the U.S. federal government launch a National Infrastructure Foundation, a nimble, collaborative strategic intervention organization that will house innovations programs from fragmented silos under one entity, inform federal officials on innovation performance metrics, strengthen industry-university partnerships, and support innovation economic development initiatives, especially to strengthen regional clusters. Because clusters are the geographic incubators of innovative products and processes, a cluster development grant program would also be targeted for implementation. By focusing on innovating in such areas as precision manufacturing, information technology, and clean energy, other areas of national concern would be tackled including government debt, carbon footprint, and oil dependence.[49] The U.S. Economic Development Administration understand this reality in their continued Regional Innovation Clusters initiative.[109] The United States also has to integrate her supply-chain and improve her applies research capability and downstream process innovation.[110]

Many countries recognize the importance of innovation including Japan’s Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT);[111] Germany’s Federal Ministry of Education and Research;[112] and the Ministry of Science and Technology in the People’s Republic of China. Russia’s innovation programme is the Medvedev modernisation programme which aims to create a diversified economy based on high technology and innovation. The Government of Western Australia has established a number of innovation incentives for government departments. Landgate was the first Western Australian government agency to establish its Innovation Program.[113]

Some regions have taken a proactive role in supporting innovation. Many regional governments are setting up innovation agencies to strengthen regional capabilities.[114] In 2009, the municipality of Medellin, Colombia created Ruta N to transform the city into a knowledge city.[115]

See alsoEdit

Look up innovation in Wiktionary, the free dictionary.

- Communities of innovation

- Creative problem solving

- Diffusion (anthropology)

- Ecoinnovation

- Hype cycle

- Induced innovation

- Information revolution

- Innovation leadership

- Innovation system

- International Association of Innovation Professionals

- ISO 56000

- Knowledge economy

- Obsolescence

- Open Innovation

- Open Innovations (Forum and Technology Show)

- Outcome-Driven Innovation

- Participatory design

- Product innovation

- Pro-innovation bias

- Sustainable Development Goals (Agenda 9)

- Technology Life Cycle

- Technological innovation system

- Theories of technology

- Timeline of historic inventions

- Toolkits for User Innovation

- UNDP Innovation Facility

- User Innovation

- Virtual product development

ReferencesEdit

- ^ Schumpeter, Joseph A., 1883–1950 (1983). The theory of economic development : an inquiry into profits, capital, credit, interest, and the business cycle. Opie, Redvers,, Elliott, John E. New Brunswick, New Jersey. ISBN 0-87855-698-2. OCLC 8493721.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ «ISO 56000:2020(en)Innovation management — Fundamentals and vocabulary». ISO. 2020.

- ^

Lijster, Thijs, ed. (2018). The Future of the New: Artistic Innovation in Times of Social Acceleration. Arts in society. Valiz. ISBN 9789492095589. Retrieved 10 September 2020. - ^ Bhasin, Kim (2 April 2012). «This Is The Difference Between ‘Invention’ And ‘Innovation’«. Business Insider.

- ^ «What’s the Difference Between Invention and Innovation?», Forbes, 10 September 2015

- ^

Schumpeter, Joseph Alois (1939). Business Cycles. Vol. 1. p. 84.Innovation is possible without anything we should identify as invention, and invention does not necessarily induce innovation.

- ^ a b c Edison, H., Ali, N.B., & Torkar, R. (2014). Towards innovation measurement in the software industry. Journal of Systems and Software 86(5), 1390–407.

- ^ Baregheh, Anahita; Rowley, Jennifer; Sambrook, Sally (4 September 2009). «Towards a multidisciplinary definition of innovation». Management Decision. 47 (8): 1323–1339. doi:10.1108/00251740910984578. ISSN 0025-1747.

- ^ Rogers, Everett M. (2003). Diffusion of innovations (5th ed.). New York: Free Press. ISBN 0-7432-2209-1. OCLC 52030797.

- ^ Innovation in American Government: Challenges, Opportunities, and Dilemmas. Brookings Inst Pr. 1 June 1997. ISBN 9780815703587.

- ^ Hughes, D. J.; Lee, A.; Tian, A. W.; Newman, A.; Legood, A. (2018). «Leadership, creativity, and innovation: A critical review and practical recommendations» (PDF). The Leadership Quarterly. 29 (5): 549–569. doi:10.1016/j.leaqua.2018.03.001. hdl:10871/32289. S2CID 149671044. Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 December 2019.

- ^ a b Drucker, Peter F. (August 2002). «The Discipline of Innovation». Harvard Business Review. Retrieved 13 October 2013.

- ^ Amabile, Teresa M.; Pratt, Michael G. (2016). «The dynamic componential model of creativity and innovation in organizations: Making progress, making meaning». Research in Organizational Behavior. 36: 157–183. doi:10.1016/j.riob.2016.10.001.

- ^ Blank, Steve (1 February 2019). «McKinsey’s Three Horizons Model Defined Innovation for Years. Here’s Why It No Longer Applies». Harvard Business Review. ISSN 0017-8012. Retrieved 16 August 2020.

- ^ Satell, Greg (21 June 2017). «The 4 Types of Innovation and the Problems They Solve». Harvard Business Review. ISSN 0017-8012. Retrieved 16 August 2020.

- ^ Bower, Joseph L.; Christensen, Clayton M. (1 January 1995). «Disruptive Technologies: Catching the Wave». Harvard Business Review. No. January–February 1995. ISSN 0017-8012. Retrieved 16 August 2020.

- ^ Christensen, Clayton M.; Raynor, Michael E.; McDonald, Rory (1 December 2015). «What Is Disruptive Innovation?». Harvard Business Review. No. December 2015. ISSN 0017-8012. Retrieved 16 August 2020.

- ^ «Disruptive Innovations». Christensen Institute. Retrieved 16 August 2020.

- ^ Christensen, Clayton & Overdorf, Michael (2000). «Meeting the Challenge of Disruptive Change». Harvard Business Review.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b

Iansiti, Marco; Lakhani, Karim R. (January 2017). «The Truth About Blockchain». Harvard Business Review. Harvard University. Retrieved 17 January 2017.a foundational technology: It has the potential to create new foundations for our economic and social systems.

- ^ a b c d Henderson, Rebecca M.; Clark, Kim B. (March 1990). «Architectural Innovation: The Reconfiguration of Existing Product Technologies and the Failure of Established Firms». Administrative Science Quarterly. 35 (1): 9. doi:10.2307/2393549. ISSN 0001-8392. JSTOR 2393549.

- ^ Schiederig, Tim; Tietze, Frank; Herstatt, Cornelius (22 February 2012). «Green innovation in technology and innovation management – an exploratory literature review». R&D Management. 42 (2): 180–192. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9310.2011.00672.x. ISSN 0033-6807. S2CID 153958119.

- ^ Blok, Vincent; Lemmens, Pieter (2015), «The Emerging Concept of Responsible Innovation. Three Reasons Why It Is Questionable and Calls for a Radical Transformation of the Concept of Innovation», Responsible Innovation 2, Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 19–35, doi:10.1007/978-3-319-17308-5_2, ISBN 978-3-319-17307-8, retrieved 17 September 2020

- ^ a b c d Godin, Benoit (2015). Innovation contested : the idea of innovation over the centuries. New York, New York. ISBN 978-1-315-85560-8. OCLC 903958473.

- ^ Politics II as cited by Benoît Godin 2015).

- ^ Mazzaferro, Alexander (2018). «Such a Murmur»: Innovation, Rebellion, and Sovereignty in William Strachey’s «True Reportory». Early American Literature. 53 (1): 3–32. doi:10.1353/eal.2018.0001. S2CID 166005186.

- ^ Mazzaferro, Alexander McLean (2017). «No newe enterprize» (Doctoral dissertation) (Thesis). Camden, New Jersey: Rutgers University. doi:10.7282/T38W3HFQ. Retrieved 19 February 2019.

- ^ Lepore, Jill (23 June 2014). «The Disruption Machine: What the gospel of innovation gets wrong». The New Yorker. Retrieved 19 February 2019.

The word ‘innovate’—to make new—used to have chiefly negative connotations: it signified excessive novelty, without purpose or end. Edmund Burke called the French Revolution a ‘revolt of innovation’; Federalists declared themselves to be ‘enemies to innovation.’ George Washington, on his deathbed, was said to have uttered these words: ‘Beware of innovation in politics.’ Noah Webster warned in his dictionary, in 1828, ‘It is often dangerous to innovate on the customs of a nation.’

- ^ Green, Emma (20 June 2013). «Innovation: The History of a Buzzword». The Atlantic. Retrieved 19 February 2019.

- ^ «innovation». Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

- ^ Godin, Benoit (2019). The invention of technological innovation : languages, discourses and ideology in historical perspective. Edward Elgar Publishing. Cheltenham, UK. ISBN 978-1-78990-334-8. OCLC 1125747489.

- ^ Schumpeter, J. A. (1943). Capitalism, Socialism, and Democracy (6 ed.). Routledge. pp. 81–84. ISBN 978-0-415-10762-4.

- ^ Heyne, P., Boettke, P. J., and Prychitko, D. L. (2010). The Economic Way of Thinking. Prentice Hall, 12th ed. pp. 163, 317–18.

- ^ «Silicon Valley History & Future». Netvalley.com. Retrieved 14 March 2016.

[…] over the course of just 20 years, a mere eight of Shockley’s former employees gave forth 65 new enterprises, which then went on to do the same. The process is still going […].

- ^

Rubin, Tzameret H.; Aas, Tor Helge; Stead, Andrew (1 July 2015). «Knowledge flow in Technological Business Incubators: Evidence from Australia and Israel». Technovation. 41–42: 11–24. doi:10.1016/j.technovation.2015.03.002. - ^

Hashim, Ahmed S. (2018). The Caliphate at War: The Ideological, Organisational and Military Innovations of Islamic State. London: Oxford University Press. p. 7. ISBN 9781849046435. Retrieved 8 February 2022.Though IS is not unique as an example of a violent nonstate actor, I argue that IS has innovated in the fields of ideology, organization, war-fighting, and strategies of state-formation.

- ^

Scott Ligon, Gina; Derrick, Douglas C.; Harms, Mackenzie (15 November 2017). «Destruction Through Collaboration: How Terrorists Work Together Toward Malevolent Innovation». In Reiter-Palmon, Roni (ed.). Team Creativity and Innovation. New York: Oxford University Press (published 2017). ISBN 9780190695323. Retrieved 8 February 2022.As seen in recent advancements by the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria (ISIS), innovation from VEOs [violent extremist organisations] can also occur in recruiting/marketing campaigns and fundraising efforts.

- ^ Utterback, James (1971). «The Process of Technological Innovation Within the Firm». Academy of Management Journal. 14 (1): 78. doi:10.2307/254712. JSTOR 254712.

- ^ Salge, T. O.; Vera, A. (2009). «Hospital innovativeness and organizational performance: Evidence from English public acute care». Health Care Management Review. 34 (1): 54–67. doi:10.1097/01.HMR.0000342978.84307.80. PMID 19104264.

- ^ West, Michael A. (2002). «Sparkling Fountains or Stagnant Ponds: An Integrative Model of Creativity and Innovation Implementation in Work Groups». Applied Psychology. 51 (3): 355–387. doi:10.1111/1464-0597.00951.

- ^ MIT Sloan Management Review Spring 2002. «How to identify and build New Businesses»

- ^ Anthony, Scott D.; Johnson, Mark W.; Sinfield, Joseph V.; Altman, Elizabeth J. (2008). Innovator’s Guide to Growth. «Putting Disruptive Innovation to Work». Harvard Business School Press. ISBN 978-1-59139-846-2.

- ^ Perez, T. and Rushing R. (2007). «The CitiStat Model: How Data-Driven Government Can Increase Efficiency and Effectiveness». Center for American Progress Report. pp. 1–18.

- ^ Transportation Research Board (2007). «Transit Cooperative Research Program (TCRP) Synthesis 70: Mobile Data Terminals». pp. 1–5. TCRP (PDF).

- ^ H. Rubin, Tzameret (2015). «The Achilles heel of a strong private knowledge sector: evidence from Israel» (PDF). The Journal of Innovation Impact. 7 (1): 80–99. Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 December 2016.

- ^ Von Hippel, Eric (1988). The Sources of Innovation (PDF). Oxford University Press. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 October 2006. Retrieved 3 December 2015.

- ^ Engelberger, J. F. (1982). «Robotics in practice: Future capabilities». Electronic Servicing & Technology magazine.

- ^ Kline (1985). Research, Invention, Innovation and Production: Models and Reality, Report INN-1, March 1985, Mechanical Engineering Department, Stanford University.

- ^ a b Mark, M., Katz, B., Rahman, S., and Warren, D. (2008) MetroPolicy: Shaping A New Federal Partnership for a Metropolitan Nation. Brookings Institution: Metropolitan Policy Program Report. pp. 4–103.

- ^ Dubickis, M., Gaile-Sarkane, E. (2015). «Perspectives on Innovation and Technology Transfer». Procedia — Social and Behavioral Sciences. 213: 965–970. doi:10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.11.512.

- ^ «New Trends in Innovation Management». Forbesindia.com. Forbes India Magazine. Retrieved 14 March 2016.

- ^ «ShipIt Days». Atlassian. Retrieved 14 March 2016.

- ^ «U-STIR». U-stir.eu. Archived from the original on 18 September 2011. Retrieved 7 September 2011.

- ^ Tuomi, I. (2002). Networks of Innovation. Oxford University Press. Networks of Innovation Archived 5 November 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Siltala, R. (2010). Innovativity and cooperative learning in business life and teaching. PhD thesis. University of Turku.

- ^ Forget The 10,000-Hour Rule; Edison, Bezos, & Zuckerberg Follow The 10,000-Experiment Rule. Medium.com (26 October 2017). Retrieved 16 October 2018.

- ^ a b Why These Tech Companies Keep Running Thousands Of Failed Experiments. Fast Company.com (21 September 2016). Retrieved 16 October 2018.

- ^ Simulation Advantage. Bcgperspectives.com (4 August 2010). Retrieved 16 October 2018.

- ^ a b Davila, T., Epstein, M. J., and Shelton, R. (2006). «Making Innovation Work: How to Manage It, Measure It, and Profit from It.» Upper Saddle River: Wharton School Publishing.

- ^ a b Vaona, Andrea; Pianta, Mario (March 2008). «Firm Size and Innovation in European Manufacturing». Small Business Economics. 30 (3): 283–299. doi:10.1007/s11187-006-9043-9. hdl:10419/3843. ISSN 0921-898X. S2CID 153525567.

- ^ Khan, Arshad M.; Manopichetwattana, V. (1989). «Innovative and Noninnovative Small Firms: Types and Characteristics». Management Science. 35 (5): 597–606. doi:10.1287/mnsc.35.5.597.

- ^ O’Sullivan, David (2002). «Framework for Managing Development in the Networked Organisations». Journal of Computers in Industry. 47 (1): 77–88. doi:10.1016/S0166-3615(01)00135-X.

- ^ Tarde, G. (1903). The laws of imitation (E. Clews Parsons, Trans.). New York: H. Holt & Co.

- ^ Rogers, E. M. (1962). Diffusion of Innovation. New York, NY: Free Press.

- ^ The Oxford handbook of innovation. Fagerberg, Jan., Mowery, David C., Nelson, Richard R. Oxford: Oxford University Press. 2005. ISBN 9780199264551. OCLC 56655392.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ a b Edison, H.; Ali, N.B.; Torkar, R. (2013). «Towards innovation measurement in the software industry». Journal of Systems and Software. 86 (5): 1390–1407. doi:10.1016/j.jss.2013.01.013 – via ResearchGate.

- ^ Davila, Tony; Marc J. Epstein and Robert Shelton (2006). Making Innovation Work: How to Manage It, Measure It, and Profit from It. Upper Saddle River: Wharton School Publishing

- ^ OECD The Measurement of Scientific and Technological Activities. Proposed Guidelines for Collecting and Interpreting Technological Innovation Data. Oslo Manual. 2nd edition, DSTI, OECD / European Commission Eurostat, Paris 31 December 1995.

- ^ «Industrial innovation – Enterprise and Industry». European Commission. Archived from the original on 27 August 2011. Retrieved 7 September 2011.

- ^ «DEVELOPMENT OF INNOVATION — European Journal of Natural History (scientific magazine)». world-science.ru. Retrieved 7 April 2021.

- ^ Chalkidou, K.; Tunis, S.; Lopert, R.; Rochaix, L.; Sawicki, P. T.; Nasser, M.; Xerri, B. (2009). «Comparative effectiveness research and evidence-based health policy: Experience from four countries». The Milbank Quarterly. 87 (2): 339–67. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0009.2009.00560.x. PMC 2881450. PMID 19523121.

- ^ Roughead, E.; Lopert, R.; Sansom, L. (2007). «Prices for innovative pharmaceutical products that provide health gain: a comparison between Australia and the United States». Value in Health. 10 (6): 514–20. doi:10.1111/j.1524-4733.2007.00206.x. PMID 17970935.

- ^ Hughes, B. (2008). «Payers Growing Influence on R&D Decision Making». Nature Reviews Drug Discovery. 7 (11): 876–78. doi:10.1038/nrd2749. PMID 18974741. S2CID 10217053.

- ^ Faunce, T.; Bai, J.; Nguyen, D. (2010). «Impact of the Australia-US Free Trade Agreement on Australian medicines regulation and prices». Journal of Generic Medicines. 7 (1): 18–29. doi:10.1057/jgm.2009.40. S2CID 154433476. Archived from the original on 16 April 2021.

- ^ Faunce TA (2006). «Global intellectual property protection of ‘innovative’ pharmaceuticals: Challenges for bioethics and health law in B Bennett and G Tomossy» (PDF). Law.anu.edu.au. Globalization and Health Springer. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 April 2011. Retrieved 18 June 2009.

- ^ Faunce, T. A. (2007). «Reference pricing for pharmaceuticals: is the Australia-United States Free Trade Agreement affecting Australia’s Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme?». Medical Journal of Australia. 187 (4): 240–42. doi:10.5694/j.1326-5377.2007.tb01209.x. PMID 17564579. S2CID 578533.

- ^ Hernán Jaramillo, Gustavo Lugones, Mónica Salazar (March 2001). «Bogota Manual. Standardisation of Indicators of Technological Innovation in Latin American and Caribbean Countries». Iberoamerican Network of Science and Technology Indicators (RICYT) Organisation of American States (OAS) / CYTED PROGRAM COLCIENCIAS/OCYT. p. 87.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link) - ^ «Social Innovation Index 2016». Economist Impact | Perspectives. Retrieved 7 April 2021.

- ^ «The INSEAD Global Innovation Index (GII)». INSEAD. 28 October 2013.

- ^ «Home page». Innovation Capacity Index.

- ^ «Tools». Statsamerica.org. Retrieved 7 September 2011.

- ^ Innovations Indikator retrieved 7 March 2017

- ^ «The INSEAD Innovation Efficiency Inndex». Technology Review. February 2016.

- ^ Adsule, Anil (2015). «INNOVATION LEADING THE WAY TO REVOLUTION» (PDF). International Journal of Business and Administration Research Review. 2, Issue.11. Archived (PDF) from the original on 1 August 2020 – via Google scholar.

- ^ Kerle, Ralph (2013). «Model for Managing Intangibility of Organizational Creativity: Management Innovation Index». Encyclopedia of Creativity, Invention, Innovation and Entrepreneurship. pp. 1300–1307. doi:10.1007/978-1-4614-3858-8_35. ISBN 978-1-4614-3857-1.

- ^ «Innovation Index». NYCEDC.com.

- ^ «Home page». statetechandscience.org.

- ^ «The World Competitiveness Scoreboard 2014» (PDF). IMD.org. 2014. Archived (PDF) from the original on 30 June 2014.

- ^ «Germany Breaks Korea’s Six-Year Streak as Most Innovative Nation». Bloomberg L.P. Retrieved 17 March 2021.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ «Infografik: Schweiz bleibt globaler Innovationsführer». Statista Infografiken. Statista (In German). Retrieved 25 November 2016.

- ^ Jamrisko, Michelle; Lu, Wei; Tanzi, Alexandre (3 February 2021). «South Korea Leads World in Innovation as U.S. Exits Top Ten». Bloomberg.

- ^ «GII 2020 Report». Global Innovation Index. Retrieved 19 October 2020.

- ^ innovations indikator 2020 (PDF) (in German). Bundesverband der Deutschen Industrie, Fraunhofer ISI, Zentrum für Europäische Wirtschaftsforschung. 2020. Archived (PDF) from the original on 8 April 2021.

- ^ a b Huebner, J. (2005). «A possible declining trend for worldwide innovation». Technological Forecasting and Social Change. 72 (8): 980–986. doi:10.1016/j.techfore.2005.01.003.

- ^ Hayden, Thomas (7 July 2005). «Science: Wanna be an inventor? Don’t bother». U.S. News & World Report. Archived from the original on 1 November 2013. Retrieved 10 June 2013.

- ^ Adler, Robert (2 July 2005). «Entering a dark age of innovation». New Scientist. Retrieved 30 May 2013.

- ^ Smart, J. (2005). «Discussion of Huebner article». Technological Forecasting and Social Change. 72 (8): 988–995. doi:10.1016/j.techfore.2005.07.001.

- ^ Huebner, Jonathan (2005). «Response by the Authors». Technological Forecasting and Social Change. 72 (8): 995–1000. doi:10.1016/j.techfore.2005.05.008.

- ^ Strumsky, D.; Lobo, J.; Tainter, J. A. (2010). «Complexity and the productivity of innovation». Systems Research and Behavioral Science. 27 (5): 496. doi:10.1002/sres.1057.

- ^ Gordon, Robert J. (2012). «Is U.S. Economic Growth Over? Faltering Innovation Confronts the Six Headwinds». NBER Working Paper No. 18315. doi:10.3386/w18315.

- ^ «Jonathan Wong, Head of DFID’s Innovation Hub | DFID bloggers». Government of the United Kingdom. 24 September 2014. Retrieved 14 March 2016.

- ^ «Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and Grand Challenge Partners Commit to Innovation with New Investments in Breakthrough Science – Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation». Gatesfoundation.org. 7 October 2014. Retrieved 14 March 2016.

- ^ «Global Development Lab | U.S. Agency for International Development». Usaid.gov. 5 August 2015. Retrieved 14 March 2016.

- ^ «International Development Innovation Network (IDIN) | D-Lab». D-lab.mit.edu. Retrieved 14 March 2016.

- ^ «Global Innovation Fund International development funding». Government of the United Kingdom. Retrieved 14 March 2016.

- ^ «Human Development Innovation Fund (HDIF)». Hdif-tz.org. 14 August 2015. Retrieved 14 March 2016.

- ^ «USAID and DFID Announce Global Development Innovation Ventures to Invest in Breakthrough Solutions to World Poverty | U.S. Agency for International Development». Usaid.gov. 6 June 2013. Archived from the original on 4 May 2017. Retrieved 14 March 2016.

- ^ «StackPath». industryweek.com. Retrieved 28 April 2020.

- ^ «U.S. Economic Development Administration : Fiscal Year 2010 Annual Report» (PDF). Eda.gov. Archived (PDF) from the original on 22 September 2011. Retrieved 14 March 2016.

- ^ «The American Way of Innovation and Its Deficiencies». American Affairs Journal. 20 May 2018. Retrieved 28 April 2020.

- ^ «Science and Technology». MEXT. Archived from the original on 5 September 2011. Retrieved 7 September 2011.

- ^ «BMBF » Ministry». Bmbf.de. Retrieved 7 September 2011.

- ^ «Home». Landgate.wa.gov.au. Landgate Innovation Program. Retrieved 14 March 2016.

- ^ Morisson, A. & Doussineau, M. (2019). Regional innovation governance and place-based policies: design, implementation and implications. Regional Studies, Regional Science,6(1),101–116. https://rsa.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/21681376.2019.1578257.

- ^ Morisson, Arnault (2018). «Knowledge Gatekeepers and Path Development on the Knowledge Periphery: The Case of Ruta N in Medellin, Colombia». Area Development and Policy. 4: 98–115. doi:10.1080/23792949.2018.1538702. S2CID 169689111.

Further readingEdit

- Bloom, Nicholas, Charles I. Jones, John Van Reenen, and Michael Webb. 2020. «Are Ideas Getting Harder to Find?», American Economic Review, 110 (4): 1104–44.

- Steven Johnson (2011). Where Good Ideas Come From. Riverhead Books. ISBN 9781594485381.

- Sonenshein, Scott (2017). Stretch: Unlock the Power of Less and Achieve More Than You Ever Imagined. Harper Business. ISBN 978-0062457226.

1

: a new idea, method, or device : novelty

2

: the introduction of something new

Did you know?

The words innovation and invention overlap semantically but are really quite distinct.

Invention can refer to a type of musical composition, a falsehood, a discovery, or any product of the imagination. The sense of invention most likely to be confused with innovation is “a device, contrivance, or process originated after study and experiment,” usually something which has not previously been in existence.

Innovation, for its part, can refer to something new or to a change made to an existing product, idea, or field. One might say that the first telephone was an invention, the first cellular telephone either an invention or an innovation, and the first smartphone an innovation.

Synonyms

Example Sentences

She is responsible for many innovations in her field.

the latest innovation in computer technology

Through technology and innovation, they found ways to get better results with less work.

the rapid pace of technological innovation

Recent Examples on the Web

What’s more, the rampant craze helped put the authorities on high alert: China’s government quickly established new rules to restrain the unencumbered growth of digital platforms that rewarded rule-breaking and risk-taking—and became more suspicious of digital financial innovation in general.

—

In 2021, Lee decided to change his career from engineering to cooking and moved from Houston to Fort Worth to open the restaurant, which opened April 1, 2022, thinking this area of Texas has a thriving environment for culinary innovation.

—

Intel helped cement the region as a global center for technological innovation, the article says.

—

One of our main stage sessions at the upcoming event will focus on innovations in the field of obesity and will include Reitano.

—

Contrary to what some might believe pickleball isn’t a new sport, but thanks to pickleball’s popularity the innovation in the game has never been more rampant.

—

Lit cables trailing down from each stage serve as a metaphor for human electricity generating the power for Lexus innovation.

—

But Capital One ranked in the top 10% for process innovation among the companies on Fortune‘s list.

—

On Monday the Supreme Court will hear oral arguments in Amgen v. Sanofi, a case with immense potential consequences for scientific innovation.

—

See More

These examples are programmatically compiled from various online sources to illustrate current usage of the word ‘innovation.’ Any opinions expressed in the examples do not represent those of Merriam-Webster or its editors. Send us feedback about these examples.

Word History

First Known Use

15th century, in the meaning defined at sense 2

Time Traveler

The first known use of innovation was

in the 15th century

Dictionary Entries Near innovation

Cite this Entry

“Innovation.” Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary, Merriam-Webster, https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/innovation. Accessed 13 Apr. 2023.

Share

More from Merriam-Webster on innovation

Last Updated:

13 Apr 2023

— Updated example sentences

Subscribe to America’s largest dictionary and get thousands more definitions and advanced search—ad free!

Merriam-Webster unabridged

While many of our regular readers are very familiar with the nuances of innovation, it’s such a difficult concept that we still come across a lot of confusion and misinformation surrounding the term in most companies – and of course the population at large.

Especially in light of recent events, innovation is seemingly on everyone’s lips, so we thought it would be important to clarify what it really means.

There’s naturally a good reason for this popularity: innovation is what essentially drives humanity forward, both in terms of well-being, but also economic growth.

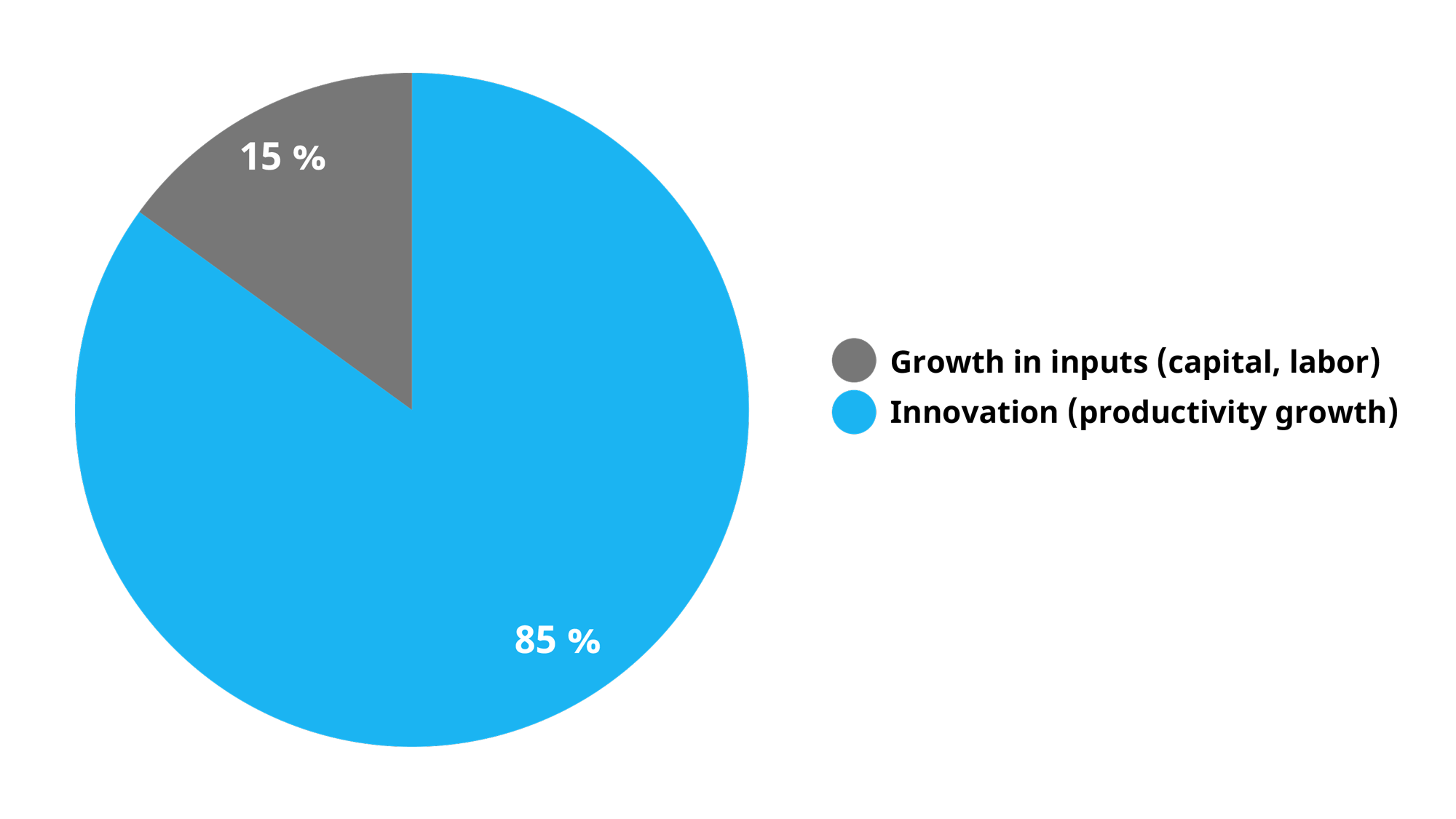

According to OECD research, 85% of all economic growth in the US economy between 1870 and 1950 actually is a result of innovation.

So, even if some of the latest technologies and companies using them are often overhyped, in the long run, innovation is what both companies and investors should really be investing in.

Table of contents

- Defining innovation

- Innovation in practice

- What do the experts say?

- Common misconceptions

- Examples of successful innovations

- How do you make it happen?

- Conclusion

Definition and true meaning of innovation

Let’s start by first defining what the term actually means.

There are literally hundreds, if not thousands, of different definitions for the word “innovation” out there, so just getting to the root of what the term actually means, can be challenging. There just isn’t a clear consensus in the industry on what the correct definition is.

We have gone through the vast majority of these definitions, and for the most part, the differences are actually relatively minor and academic in nature.

In general, everyone agrees that innovations are “novel”. Many argue that it’s not an innovation, but an invention, unless it “creates value”.

The challenge is that these are both naturally very subjective terms.

- Does something have to be “new” or “novel” to the entire world for it to count as an innovation? What about your industry or market? Or just for your company?

- For whom should it “create value”? For customers? For the company and its shareholders? What about the society at large?

- And how do you even define value? Is it just monetary value, or do softer measures count as well? What if it creates tremendous value for some individuals, but is harmful at large?

Thus, it’s virtually impossible to come up with a truly objective way to tell if something is an innovation – or not. Thus, it’s probably best to keep the definition of the word quite accommodating.

The introduction of something new.

– Merriam-Webster online dictionary

In other words, innovation is simply anything new that you do.

It can be new products or services, a new manufacturing process that saves a lot of resources, or even just a minor improvement in an existing product or process.

Using the term “innovation” in practice

Knowing how often people interpret the term “innovation” in so wildly different ways, those of us who are in the business of trying to make it happen should obviously be mindful of the challenges that careless use of the term may lead to.

So, whenever you’re talking about “innovation” with a new audience, it’s often helpful to start by ensuring that you’re on the same page when it comes to the terminology, or your conversation might turn out to not be as productive as you hoped it would be.

What can we learn from the experts – our favorite quotes on innovation

Since innovation is a topic that some of the smartest minds on our planet have put a lot of thought into, we thought it would also make sense to provide you with a few of our favorite quotes on innovation. They really do a great job of capturing the essence of innovation.

1

“Innovation is taking two things that exist and putting them together in a new way.“

Tom Freston (born 1945), Co-founder of MTV

2

“What is the calculus of innovation? The calculus of innovation is really quite simple: Knowledge drives innovation, innovation drives productivity, productivity drives economic growth.“

William Brody (born 1944), Scientist

3

“Creativity is thinking up new things. Innovation is doing new things.“

Theodore Levitt (1925 – 2006), Renown economist

4

“You can’t wait for inspiration, you have to go after it with a club.“

Albert Einstein (1879 – 1955), Mathematician

5

“I have not failed. I’ve just found 10,000 ways that won’t work.“

Thomas Edison (1847 – 1931), Inventor

6

“There’s a way to do it better. Find it.“

Thomas Edison (1847 — 1931), Inventor

7

“The riskiest thing we can do is just maintain the status quo.“

Bob Iger (born 1951), Media executive & businessman

8

“When the winds of change blow, some people build walls and others build windmills.“

An ancient Chinese proverb

9

“Innovation- any new idea- by definition will not be accepted at first. It takes repeated attempts, endless demonstrations, monotonous rehearsals before innovation can be accepted and internalized by an organization. This requires courageous patience.“

Warren Bennis (1925 – 2014), Scholar and organizational consultant

Lessons learned

When we put all of those thoughts together, what can we learn?

- Innovation is ultimately about putting the figurative 1 + 1 of existing knowledge together to create something novel.

- Innovation takes a lot of hard work, it’s not just about being creative or coming up with a great idea.

- Innovation always feel risky and new ideas will usually be resisted, that’s just a part of the process.

- Still, the riskiest thing you can do is to try to stick with the past and not embrace the change.

Common misconceptions about innovation

Now that we’ve understand the big picture, let’s clear a few of the most common misconceptions about innovation.

“Innovation is something startups do”

This is probably one of the most common misconceptions out there.

Sure, many startups are tremendously innovative, and drive a significant portion of the innovation in our society, but that

-

- doesn’t mean that all startups would be innovative

- doesn’t mean that large organizations wouldn’t innovate

First of all, not every startup is innovative. If you decide to open up a lemonade stand and set up a company for it, it is a startup, but there probably isn’t anything new or innovative there.

Just think of the device you’re using to read this article. It’s without a doubt a product created and sold by a large company, with most of the meaningful hardware and software components on it also being developed by other large organizations.

It’s actually the medium-sized organizations that are usually worst positioned to innovate: they don’t have the resources of the big companies, and unlike startups, they usually have existing processes in place, as well as something to lose, which makes them less likely to want to embrace change and innovation.

This is something we very much empathize with, and it’s a big part of our mission to help them change this.

“Build and they will come”

This is the traditional way people approached innovation. You simply created a pretty good product, and usually people came and found you.

Well, these days, most of us in the developed world have most of our basic needs met, and there’s so much information and so many different products and services out there, that it doesn’t usually work like that anymore.

These days, you have to start by truly, deeply, understanding your customer, and the specific problems they’re trying to solve, or you’re very likely to fail at innovation.

“Innovation has to be a groundbreaking technological invention”

Many still think that innovations have to be these big, groundbreaking inventions.

Well, as we covered earlier, that simply isn’t true.

In addition, innovations can be any kind of novel, even seemingly minor things, that just make a difference in the grand scheme of things. They don’t even have to be technological at all.

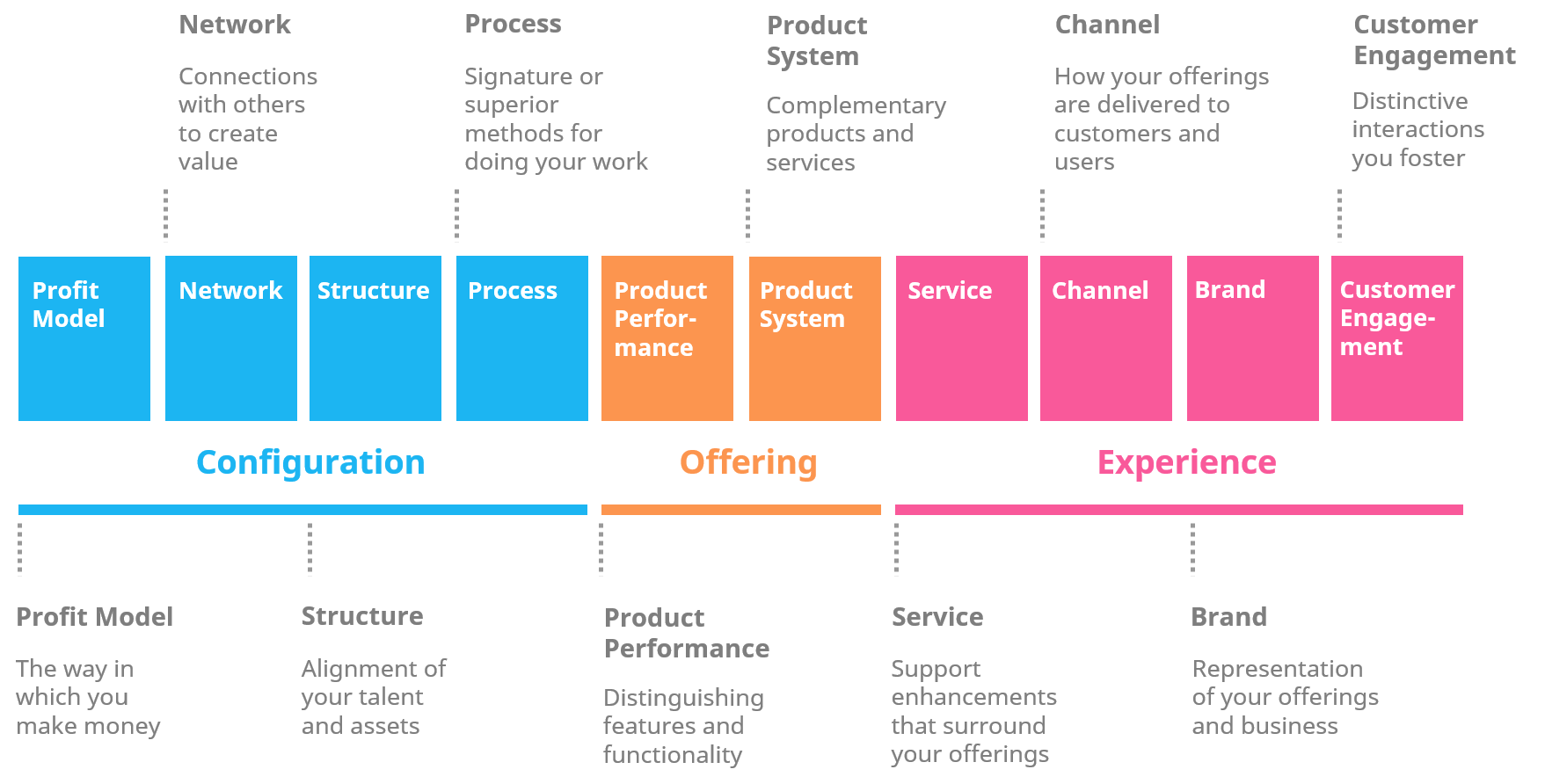

As a matter of fact, marketing and business model innovations are incredibly powerful forms of innovation, that don’t require you to necessarily invest in cutting edge research.

Even a few relatively simple improvements in some of your internal processes can be the difference between being profitable or not, so incremental innovations are usually very important, especially for large companies.

Examples of successful innovations

So, what do successful innovations then look like?

Well, everyone is familiar with those big new technological breakthroughs that changed the world, like the lightbulb, and the Internet, so we’ll next show a few more subtle examples of successful innovations from throughout history.

The subscription business model

Business model innovation is one of the most powerful, yet simultaneously underappreciated forms of innovation.

While the business model itself is obviously pretty old, it’s been successfully used for ages in things like newspapers and season tickets, it’s really gained incredible popularity in the last couple of decades.

After Salesforce pioneered the Software as a Service business model in the early 2000s, we’ve literally seen an explosion in subscription businesses, and for good reason.

A subscription business model makes it easier for customers to buy as they aren’t forced to make an upfront investment and have the flexibility to end their subscription whenever they want. For the business, it aligns their interests with the customer, provides a more predictable source of revenue, and ultimately allows them to increase profitability down the road.

It’s a great example of a seemingly simple change that can make all the difference between success and failure.

Seasonal crop rotation

Way back in the day when humans first started cultivating crops, a similar pattern emerged in many diverse geographical areas.

Thanks to the agricultural revolution, population quickly began to grow. As the population grew, more and more land was needed to grow food for everyone. Farmland thus expanded until there was no more arable land in the vicinity to expand to.

At that point, people often started cultivating the land more aggressively and only chose to plant the most productive crops to cope with the increased demand.

When you plant the same crop in the same place year after year, the soil will gradually lose more and more of its nutrients. This will in turn lower crop yields and eventually lead to the land becoming unusable for farming for extended periods of time.

The solution to this problem is incredibly simple: you essentially just rotate the placing of the crops every season and perhaps give the soil a season to rest every now and then.

This seemingly simple process innovation alone was usually enough to preserve the quality of the land and save the lives of thousands, perhaps even millions, of people back when we didn’t have all the fancy technology and knowledge we today possess.

The Ritz-Carlton $2,000 rule

The $2,000 rule is an example of a very different kind of a process innovation, one that focuses on the customer experience.

As a luxury hotel chain, Ritz-Carlton is one of the embodiments of great customer service, and for them to stay in business, they do need to live up to their reputation.

To ensure that is the case, they’ve long had the so called $2,000 rule, which as the name would suggest, indicates that any frontline employee can spend up to $2,000 right away without asking their manager for permission to address any and all problems customers might face.

And that is not $2,000 per year, but $2,000 per incident. This might raise a few eyebrows at first, but when you consider that their customers spend an average of $250,000 during their lifetime, it suddenly makes a lot of sense.

The same exact rule might not make sense for your business, but it’s still a great example of a really simple change that can make a huge difference in making customers lives’ much easier.

How does innovation happen in practice?

So, now that you have a pretty good of what innovations really is, the question remains, how do you actually create one?

Well, it’s a whole art and a science of its own, there isn’t necessarily just one “right way to innovate”.

What’s more, the answer also depends highly on whether you’re looking to create smaller, incremental innovations, or perhaps the bigger, more outside the box, breakthrough innovations.

Also, if you’re looking to innovate as a startup, the challenges you face will be somewhat different than if you were to innovate within a large incumbent organization.

However, there are also many similarities. Here’s the high-level overview of the way we like to approach this:

-

- Identify a meaningful problem, if it’s a big one, break it down into smaller chunks

- Find the best solution with first principles thinking

- Solve the problem(s) and create real value

- Keep an open mind and continuously look for things to improve upon

That’s of course easier said than done. Still, it’s important to keep the big picture in mind and not get lost in the weeds.

In essence, you should usually start by identifying a meaningful problem you’d like to solve for your customers. Alternatively, this could also be a bigger, more far flung but ambitious and concrete objective.

Almost never can you solve these meaningful problems with just a single innovation, so what you then need to do is to break the problem or objective into smaller chunks.

Then, you can simply start solving the problem or problems, one by one. Just make sure to do it in a way that creates real, tangible value.

The above two steps are essentially what all agile methods and movements like the lean startup are all about.

Finally, to get to the best possible solution, you should keep an open mind and continuously look for better ways to solve the problem and achieve your objectives, and the way you do that is by embracing first principles thinking.

Here’s Elon Musk explaining the concept:

Conclusion

If innovation is an art and a science of its own, so is the act of making it happen in organizations. This is what’s referred to as innovation management, or the ability to systematically introduce new things and manage the whole process in a way that helps you make innovation more predictable and scalable.

It’s such a big topic, and one that we’ve written about quite extensively, that we won’t cover it in more detail here. However, if you are looking to make more innovation happen in your organization, a great place to start from is our Innovation System Online Coaching Program.

It is an online program that will walk you through the process of making more innovation happen in your organization, step-by-step. We guarantee it will help deliver real business results for you.

Meaning Innovation

What does Innovation mean? Here you find 46 meanings of the word Innovation. You can also add a definition of Innovation yourself

1 |

0 Innovation, whether it relates to the development of new products, processes or organisational techniques, can help give economic operators a competitive edge. The European Union is acutely aware of t [..]

|

2 |

0 InnovationThe introduction of new ideas, goods, etc., or new methods of production. A new way of doing something.

|

3 |