From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

An idiom is a phrase or expression that typically presents a figurative, non-literal meaning attached to the phrase; but some phrases become figurative idioms while retaining the literal meaning of the phrase. Categorized as formulaic language, an idiom’s figurative meaning is different from the literal meaning.[1] Idioms occur frequently in all languages; in English alone there are an estimated twenty-five million[dubious – discuss] idiomatic expressions.[2]

Derivations[edit]

Many idiomatic expressions were meant literally in their original use, but sometimes the attribution of the literal meaning changed and the phrase itself grew away from its original roots—typically leading to a folk etymology. For instance, the phrase «spill the beans» (meaning to reveal a secret) is first attested in 1919, but has been said to originate from an ancient method of voting by depositing beans in jars, which could be spilled, prematurely revealing the results.[3]

Other idioms are deliberately figurative. For example, «break a leg» is an ironic expression to wish a person good luck just prior to their giving a performance or presentation. It may have arisen from the superstition that one ought not utter the words «good luck» to an actor because it is believed that doing so will cause the opposite result.[4]

Compositionality[edit]

Love is blind—an idiom meaning a person who is in love can see no faults or imperfections in the person whom they love.[5]

In linguistics, idioms are usually presumed to be figures of speech contradicting the principle of compositionality. That compositionality is the key notion for the analysis of idioms is emphasized in most accounts of idioms.[6][7] This principle states that the meaning of a whole should be constructed from the meanings of the parts that make up the whole. In other words, one should be in a position to understand the whole if one understands the meanings of each of the parts that make up the whole. The following example is widely employed to illustrate the point:

Fred kicked the bucket.

Understood compositionally, Fred has literally kicked an actual, physical bucket. The much more likely idiomatic reading, however, is non-compositional: Fred is understood to have died. Arriving at the idiomatic reading from the literal reading is unlikely for most speakers. What this means is that the idiomatic reading is, rather, stored as a single lexical item that is now largely independent of the literal reading.

In phraseology, idioms are defined as a sub-type of phraseme, the meaning of which is not the regular sum of the meanings of its component parts.[8] John Saeed defines an idiom as collocated words that became affixed to each other until metamorphosing into a fossilised term.[9] This collocation of words redefines each component word in the word-group and becomes an idiomatic expression. Idioms usually do not translate well; in some cases, when an idiom is translated directly word-for-word into another language, either its meaning is changed or it is meaningless.

When two or three words are conventionally used together in a particular sequence, they form an irreversible binomial. For example, a person may be left «high and dry», but never «dry and high». Not all irreversible binomials are idioms, however: «chips and dip» is irreversible, but its meaning is straightforwardly derived from its components.

Mobility[edit]

Idioms possess varying degrees of mobility. Whereas some idioms are used only in a routine form, others can undergo syntactic modifications such as passivization, raising constructions, and clefting, demonstrating separable constituencies within the idiom.[10] Mobile idioms, allowing such movement, maintain their idiomatic meaning where fixed idioms do not:

- Mobile

- I spilled the beans on our project. → The beans were spilled on our project.

- Fixed

- The old man kicked the bucket. → The bucket was kicked (by the old man).

Many fixed idioms lack semantic composition, meaning that the idiom contains the semantic role of a verb, but not of any object. This is true of kick the bucket, which means die. By contrast, the semantically composite idiom spill the beans, meaning reveal a secret, contains both a semantic verb and object, reveal and secret. Semantically composite idioms have a syntactic similarity between their surface and semantic forms.[10]

The types of movement allowed for certain idioms also relate to the degree to which the literal reading of the idiom has a connection to its idiomatic meaning. This is referred to as motivation or transparency. While most idioms that do not display semantic composition generally do not allow non-adjectival modification, those that are also motivated allow lexical substitution.[11] For example, oil the wheels and grease the wheels allow variation for nouns that elicit a similar literal meaning.[12] These types of changes can occur only when speakers can easily recognize a connection between what the idiom is meant to express and its literal meaning, thus an idiom like kick the bucket cannot occur as kick the pot.

From the perspective of dependency grammar, idioms are represented as a catena which cannot be interrupted by non-idiomatic content. Although syntactic modifications introduce disruptions to the idiomatic structure, this continuity is only required for idioms as lexical entries.[13]

Certain idioms, allowing unrestricted syntactic modification, can be said to be metaphors. Expressions such as jump on the bandwagon, pull strings, and draw the line all represent their meaning independently in their verbs and objects, making them compositional. In the idiom jump on the bandwagon, jump on involves joining something and a ‘bandwagon’ can refer to a collective cause, regardless of context.[10]

Translation[edit]

A word-by-word translation of an opaque idiom will most likely not convey the same meaning in other languages. The English idiom kick the bucket has a variety of equivalents in other languages, such as kopnąć w kalendarz («kick the calendar») in Polish, casser sa pipe («to break his pipe») in French[14] and tirare le cuoia («pulling the leathers») in Italian.[15]

Some idioms are transparent.[16] Much of their meaning gets through if they are taken (or translated) literally. For example, lay one’s cards on the table meaning to reveal previously unknown intentions or to reveal a secret. Transparency is a matter of degree; spill the beans (to let secret information become known) and leave no stone unturned (to do everything possible in order to achieve or find something) are not entirely literally interpretable but involve only a slight metaphorical broadening. Another category of idioms is a word having several meanings, sometimes simultaneously, sometimes discerned from the context of its usage. This is seen in the (mostly uninflected) English language in polysemes, the common use of the same word for an activity, for those engaged in it, for the product used, for the place or time of an activity, and sometimes for a verb.

Idioms tend to confuse those unfamiliar with them; students of a new language must learn its idiomatic expressions as vocabulary. Many natural language words have idiomatic origins but are assimilated and so lose their figurative senses. For example, in Portuguese, the expression saber de coração ‘to know by heart’, with the same meaning as in English, was shortened to ‘saber de cor’, and, later, to the verb decorar, meaning memorize.

In 2015, TED collected 40 examples of bizarre idioms that cannot be translated literally. They include the Swedish saying «to slide in on a shrimp sandwich», which refers those who did not have to work to get where they are.[17]

Conversely, idioms may be shared between multiple languages. For example, the Arabic phrase في نفس المركب (fi nafs al-markab) is translated as «in the same boat,» and it carries the same figurative meaning as the equivalent idiom in English.

According to the German linguist Elizabeth Piirainen, the idiom «to get on one’s nerves» has the same figurative meaning in 57 European languages. She also says that the phrase «to shed crocodile tears,» meaning to express insincere sorrow, is similarly widespread in European languages but is also used in Arabic, Swahili, Persian, Chinese, Mongolian, and several others.[citation needed]

The origin of cross-language idioms is uncertain. One theory is that cross-language idioms are a language contact phenomenon, resulting from a word-for-word translation called a calque. Piirainen says that may happen as a result of lingua franca usage in which speakers incorporate expressions from their own native tongue, which exposes them to speakers of other languages. Other theories suggest they come from a shared ancestor language or that humans are naturally predisposed to develop certain metaphors.[citation needed]

Dealing with non-compositionality[edit]

The non-compositionality of meaning of idioms challenges theories of syntax. The fixed words of many idioms do not qualify as constituents in any sense. For example:

How do we get to the bottom of this situation?

The fixed words of this idiom (in bold) do not form a constituent in any theory’s analysis of syntactic structure because the object of the preposition (here this situation) is not part of the idiom (but rather it is an argument of the idiom). One can know that it is not part of the idiom because it is variable; for example, How do we get to the bottom of this situation / the claim / the phenomenon / her statement / etc. What this means is that theories of syntax that take the constituent to be the fundamental unit of syntactic analysis are challenged. The manner in which units of meaning are assigned to units of syntax remains unclear. This problem has motivated a tremendous amount of discussion and debate in linguistics circles and it is a primary motivator behind the Construction Grammar framework.[18]

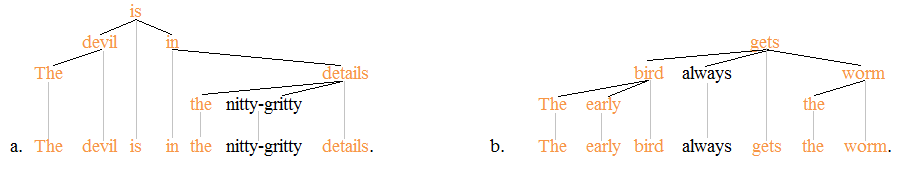

A relatively recent development in the syntactic analysis of idioms departs from a constituent-based account of syntactic structure, preferring instead the catena-based account. The catena unit was introduced to linguistics by William O’Grady in 1998. Any word or any combination of words that are linked together by dependencies qualifies as a catena.[19] The words constituting idioms are stored as catenae in the lexicon, and as such, they are concrete units of syntax. The dependency grammar trees of a few sentences containing non-constituent idioms illustrate the point:

The fixed words of the idiom (in orange) in each case are linked together by dependencies; they form a catena. The material that is outside of the idiom (in normal black script) is not part of the idiom. The following two trees illustrate proverbs:

The fixed words of the proverbs (in orange) again form a catena each time. The adjective nitty-gritty and the adverb always are not part of the respective proverb and their appearance does not interrupt the fixed words of the proverb. A caveat concerning the catena-based analysis of idioms concerns their status in the lexicon. Idioms are lexical items, which means they are stored as catenae in the lexicon. In the actual syntax, however, some idioms can be broken up by various functional constructions.

The catena-based analysis of idioms provides a basis for an understanding of meaning compositionality. The Principle of Compositionality can in fact be maintained. Units of meaning are being assigned to catenae, whereby many of these catenae are not constituents.

Various studies have investigated methods to develop the ability to interpret idioms in children with various diagnoses including Autism,[20] Moderate Learning Difficulties,[21] Developmental Language Disorder [22] and typically developing weak readers.[23]

See also[edit]

- Adage

- Catena (linguistics)

- Chengyu

- Cliché

- Collocation

- Comprehension of idioms

- English-language idioms

- Figure of speech

- Metaphor

- Multiword expression

- Phrasal verb

- Principle of compositionality

- Rhetorical device

References[edit]

- ^ The Oxford companion to the English language (1992:495f.)

- ^ Jackendoff (1997).

- ^ «The Mavens’ Word of the Day: Spill the Beans». Random House. 23 February 2001. Archived from the original on 25 April 2011. Retrieved 28 July 2021.

- ^ Gary Martin. «Break a leg». The Phrase Finder.

- ^ Elizabeth Knowles, ed. (2006). The Oxford Dictionary of Phrase and Fable. Oxford University Press. pp. 302–3. ISBN 9780191578564.

the saying is generally used to mean that a person is often unable to see faults in the one they love.

- ^ Radford (2004:187f.)

- ^ Portner (2005:33f).

- ^ Mel’čuk (1995:167–232).

- ^ For Saeed’s definition, see Saeed (2003:60).

- ^ a b c Horn, George (2003). «Idioms, Metaphors, and Syntactic Mobility». Journal of Linguistics. 39 (2): 245–273. doi:10.1017/s0022226703002020.

- ^ Keizer, Evelien (2016). «Idiomatic expressions in Functional Discourse Grammar». Linguistics. 54 (5): 981–1016. doi:10.1515/ling-2016-0022. S2CID 151574119.

- ^ Mostafa, Massrura (2010). «Variation in V+the+N idioms». English Today. 26 (4): 37–43. doi:10.1017/s0266078410000325. S2CID 145266570.

- ^ O’Grady, William (1998). «The Syntax of Idioms». Natural Language and Linguistic Theory. 16 (2): 279–312. doi:10.1023/a:1005932710202. S2CID 170903210.

- ^ «Translation of the idiom kick the bucket in French». www.idiommaster.com. Retrieved 2018-01-06.

- ^ «Translation of the idiom kick the bucket in Italian». www.idiommaster.com. Retrieved 2018-01-06.

- ^ Gibbs, R. W. (1987)

- ^ «40 brilliant idioms that simply can’t be translated literally». TED Blog. Retrieved 2016-04-08.

- ^ Culicver and Jackendoff (2005:32ff.)

- ^ Osborne and Groß (2012:173ff.)

- ^ Mashal and Kasirer, 2011

- ^ Ezell and Goldstein, 1992

- ^ Benjamin, Ebbels and Newton, 2020

- ^ Lundblom and Woods, 2012

Bibliography[edit]

- Benjamin, L.; Ebbels, S.; Newton, C. (2020). «Investigating the effectiveness of idiom intervention for 9-16 year olds with developmental language disorder». International Journal of Language and Communication Disorders. 55 (2): 266–286. doi:10.1111/1460-6984.12519. PMID 31867833.

- Crystal, A dictionary of linguistics and phonetics, 4th edition. Oxford, UK: Blackwell Publishers.

- Culicover, P. and R. Jackendoff. 2005. Simpler syntax. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

- Ezell, H.; Goldstein, H. (1992). «Teaching Idiom Comprehension To Children with Mental Retardation». Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 25 (1): 181–191. doi:10.1901/jaba.1992.25-181. PMC 1279665. PMID 1582965.

- Gibbs, R (1987). «Linguistic factors in children’s understanding of idioms». Journal of Child Language. 14 (3): 569–586. doi:10.1017/s0305000900010291. PMID 2447110. S2CID 6544015.

- Jackendoff, R. 1997. The architecture of the language faculty. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press.

- Jurafsky, D. and J. Martin. 2008. Speech and language processing: An introduction to natural language processing, computational linguistics, and speech recognition. Dorling Kindersley (India): Pearson Education, Inc.

- Leaney, C. 2005. In the know: Understanding and using idioms. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Lundblom, E.; Woods, J. (2012). «Working in the Classroom: Improving Idiom Comprehension Through Classwide Peer Tutoring». Communication Disorders Quarterly. 33 (4): 202–219. doi:10.1177/1525740111404927. S2CID 143858683.

- Mel’čuk, I. 1995. «Phrasemes in language and phraseology in linguistics». In M. Everaert, E.-J. van der Linden, A. Schenk and R. Schreuder (eds.), Idioms: Structural and psychological perspectives, 167–232. Hillsdale, N.J.: Lawrence Erlbaum.

- Mashal, Nira; Kasirer, Anat (2011). «Thinking maps enhance metaphoric competence in children with autism and learning disabilities». Research in Developmental Disabilities. 32 (6): 2045–2054. doi:10.1016/j.ridd.2011.08.012. PMID 21985987.

- O’Grady, W (1998). «The syntax of idioms». Natural Language and Linguistic Theory. 16 (2): 79–312. doi:10.1023/A:1005932710202. S2CID 170903210.

- Osborne, T.; Groß, T. (2012). «Constructions are catenae: Construction Grammar meets Dependency Grammar». Cognitive Linguistics. 23 (1): 163–214. doi:10.1515/cog-2012-0006.

- Portner, P. 2005. What is meaning?: Fundamentals of formal semantics. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing.

- Radford, A. English syntax: An introduction. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Saeed, J. 2003. Semantics. 2nd edition. Oxford: Blackwell.

Further reading[edit]

- Editors of the American Heritage Dictionaries (2011). The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language (5th ed.). Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Trade. ISBN 978-0547041018.

External links[edit]

- The Idioms – Online English idioms dictionary.

- babelite.org – Online cross-language idioms dictionary in English, Spanish, French and Portuguese.

Have you ever heard an expression but had no idea what it meant? If you have, it’s probably because it was an idiom. Writers are always looking for the most natural way to write dialogue and literary devices like the idiom are just one technique available. But what is an idiom? We’re going to answer that question by breaking down the idiom definition and by looking at some examples.

Define Idiom

First, let’s define idiom

What is an idiom? A more general answer is that it is a literary device writers use to capture «realistic dialogue.» A more specific answer is that it the use of expressions and turns of phrase to communicate. Let’s answer that question with an idiom definition.

IDIOM DEFINITION

What is an idiom?

An idiom is a figurative expression where the meaning cannot be interpreted solely by the conjunction of its words; e.g., “by the skin of your teeth” means “barely getting by.” These expressions and phrases are interpreted as nonsensical by those who don’t have prior knowledge of them. They are also often culturally specific — most languages and cultures have their own sets. This form of expression is often confused with other literary devices such as metaphor, simile, proverbs, euphemisms and cliches. But as we will explain in a minute, there are distinct differences in form and function.

Idiom Examples:

- Beat around the bush

- Under the weather

- The last straw

- Miss the boat

Idioms can often be confused with other types of figurative language. Let’s take a look at what makes them distinct.

Origins

What is an idiom (and what isn’t)

Idioms fall under the umbrella of figurative language, which plays an important role in writing and everyday conversations.

But what is figurative language?

Figurative language is when something means something other than its literal meaning. For example: the term “I feel like a million bucks” is an example of figurative language.

Metaphors, similes, and allusions are all types of figurative language. Check out this video from Khan Academy to learn more about figurative language.

Let’s Define Idiom • Context of Figurative Language by Khan Academy

We use idioms to communicate non-literal ideas, but we also use other figurative language to do the same thing. So, what makes them different?

Idiom vs. Metaphor

A metaphor is when a word is applied to another word in a non-literal manner. For example: “Jeff was a rollercoaster.” Jeff is not literally a rollercoaster, he just is temperamental. But we can derive meaning from this phrase even if we haven’t heard it before.

With an phrase like “pulling someone’s leg,” you’re not applying a word to another word figuratively; the entire phrase is figurative. That said, sometimes an idiom can be a metaphor (and vice versa).

Take, for example, “it’s not rocket science.” This is a common idiom, but also is comparing two things figuratively– “rocket science” and “it.”

Idiom vs. Proverb

Idioms and proverbs are also commonly confused. Like an idiom, proverbs are widely repeated. But with proverbs, meaning can be derived from the phrase even without prior knowledge. Take the proverb “a picture is worth a thousand words.” If you had never heard this phrase before, you would still be able to discern its message: pictures can contain a lot of information.

If you had never heard the expression “bite the bullet,” you’d be a little lost.

Idiom vs. Euphemism

A euphemism uses an indirect word to convey a harsher meaning, like saying “I’m in between jobs” instead of “I’m unemployed.” Idioms can sometimes operate as euphemisms, like saying “she has a bun in the oven” instead of “she’s pregnant.”

But not all euphemisms are idioms, and not all idioms are euphemisms. “I’m in between jobs” conveys a clear meaning, even if it sounds nicer than “I’m unemployed,” so it isn’t an idiom. Likewise, “let’s bite the bullet” isn’t really a softer way to say “let’s get it done,” so it’s not a euphemism.

Idiom vs. Cliché

A cliché is often in the eye of the beholder. The term refers to a phrase or idea that is overused. So, by definition, most idioms are clichés, since they depend on wide usage to convey their meaning. If “hit the sack” wasn’t said by everybody, nobody would know what it meant.

Another cliché

So most idioms could be considered clichés, but not all clichés are idioms. Take “cold as ice.” Anyone without prior knowledge understands what that means, so it’s not an idiom, but it’s an overused phrase, so you could call it a cliché.

Storytelling Idioms

Types of Idioms

Now that we’ve compared this device to other types of figurative language, let’s look at the various types of idioms. We know, we know — a lot of categorizing.

Pure

The pure idiom is the most easily recognizable form, the one we’ve been using the most so far. It’s a full phrase which has a meaning that can’t be deduced without prior knowledge.

Some more pure idiom examples: “speak of the devil,” “let her off the hook.”

Binomial

The binomial idiom is short and sweet. Wait a minute – that was one right there. The binomial is two words combined with a conjunction. Like with all idioms, the meaning is unclear to anyone who hasn’t heard it before.

With “short and sweet,” it may not be obvious what exactly the sweet part might mean.

Here are some additional binomial idiom examples: “by and large,” “bread and butter,” “fair and square,” “heart to heart.”

Partial

A partial idiom is, as its name may indicate, just a part of an idiom. The most common example of this is “when in Rome.” The entire idiom is “when in Rome, do as the Romans do.”

Do as the Romans do

More than any other type, partial idioms really rely on familiarity.

Prepositional

Last but not least, we have prepositional idioms. These are phrases which combine a preposition and a word to alter the meaning of said word.

They’re pretty subtle – think of “in advance,” “on hand,” or “out of the blue,” for example.

Classic Expressions

Idiom Examples

Different languages and different dialects have their own particular idiom examples. Here are some common idiom examples in English:

- “It’s raining cats and dogs out there.” – there is a lot of rain outside

- “Things are getting out of hand.” – losing control over a situation

- “Going to hit the sack.” – going to sleep

- “Missed the boat.” – too late

- “Feeling under the weather.” – feeling sick

- “Play devil’s advocate.” – take a contrarian stance

- “Kill two birds with one stone.” – accomplish two tasks with one action

- “Break the ice.” – open a line of communication

- “Don’t count your chickens before they hatch.” – don’t assume something is going to happen

- “Spill the beans.” – share a secret

- “Don’t judge a book by its cover.” – don’t judge something by what it appears to be

- “Elephant in the room.” – an unspoken but known issue

These are just some of the most common idiom examples in English – you might be surprised just how many there are! If you want to check out some other idiom examples (along with some great animations), check out the video from Domics below.

Writing Idioms • What is an Idiom by Domics

Idioms are niche examples of figurative language – but they play an important role in cultural learning. Let’s look at how these expressions are used by analyzing why they’re an important part of cultural learning.

Idiom Meaning

Why use idioms?

We use idioms in everyday conversations – but what are the benefits of including them in writing? Well, they add linguistic nuance to conversation and tell us about the culture of characters.

Every language has its own idioms. They are developed over time to express peculiarities about cultures, and oftentimes, they’re nonsensical when translated literally.

Why is that? Because they’re a sort of cultural “inside joke.”

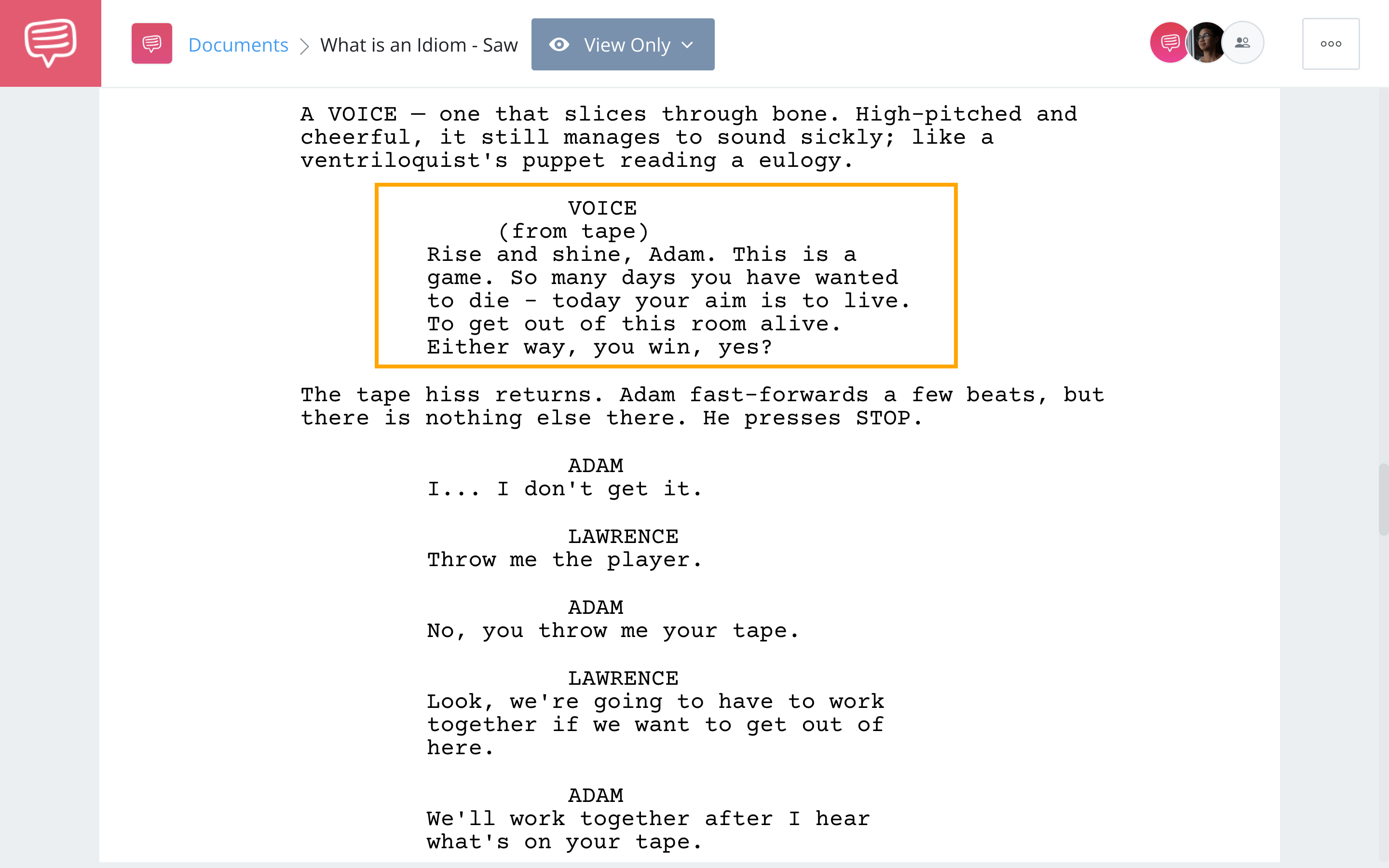

Take this example from Saw, which was written by Leigh Whannell and James Wan. We imported the script into StudioBinder’s screenwriting software:

Saw Idiom Example • Read Full Scene

Here, the “voice” uses a binomial idiom: “rise and shine.” By using this friendly and colloquial term, Whannell and Wan make the scene much creepier. There’s nothing worse than faux-friendliness from a sadistic monster.

On a lighter note, I like to reference this example when explaining the difference between idioms in different cultures:

In Italian, people often say “in bocca al lupo” to wish good luck. “In bocca al lupo” translates to English as “in the mouth of the wolf.” Wait, that doesn’t make sense! Well, figuratively it kind of does.

In English, people often say “break a leg” to wish good luck. When you think about it, neither “break a leg” or “in the mouth of the wolf” have anything to do with wishing good luck. This underscores the greater notion that cultures often express ideas differently while retaining the same connotation.

Essentially, an idiom may have the same meaning as others, even if they seemingly make no sense.

This next video from Crash Course analyzes why it’s important to know about idioms and “mythical language.”

Idioms for Writers • Mythical Language and Idioms by Crash Course

What does this video teach us about idioms? Well, I’d say it teaches us that idioms are part of “universal language.” Although we use different words, we often express the same things. In other words, the notion of “good luck” is part of universal language – and although we wish good luck in different ways, we mean the same thing.

By using idioms in writing, we can build universality (or even confusion). Idioms are simply tools for writers to experiment with.

What does this video teach us about idioms? Well, I’d say it teaches us that these expressions are part of “universal language.” Although we use different words, we often express the same things. In other words, the notion of “good luck” is part of universal language – and although we wish good luck in different ways, we mean the same thing.

By using idioms in writing, we can build universality (or even confusion). Idioms are simply tools for writers to experiment with.

UP NEXT

What are Tropes?

Tropes are an important part of figurative storytelling – but what are tropes? In our next article, we’ll explain tropes with examples from Once Upon a Time… in Hollywood, The Other Guys, and more. We’ll also show you can use tropes subversively to avoid creating cliches.

Up Next: Trope Definition & Examples →

1

: an expression in the usage of a language that is peculiar to itself either in having a meaning that cannot be derived from the conjoined meanings of its elements (such as up in the air for «undecided») or in its grammatically atypical use of words (such as give way)

2

a

: the language peculiar to a people or to a district, community, or class : dialect

3

: a style or form of artistic expression that is characteristic of an individual, a period or movement, or a medium or instrument

Did you know?

If you had never heard someone say «We’re on the same page,» would you have understood that they weren’t talking about a book? And the first time someone said he’d «ride shotgun», did you wonder where the gun was? A modern English-speaker knows thousands of idioms, and uses many every day. Idioms can be completely ordinary («first off», «the other day», «make a point of», «What’s up?») or more colorful («asleep at the wheel», «bite the bullet», «knuckle sandwich»). A particular type of idiom, called a phrasal verb, consists of a verb followed by an adverb or preposition (or sometimes both); in make over, make out, and make up, for instance, notice how the meanings have nothing to do with the usual meanings of over, out, and up.

View more idiom examples, definitions, and origins

Synonyms

Example Sentences

She is a populist in politics, as she repeatedly makes clear for no very clear reason. Yet the idiom of the populace is not popular with her.

—

And the prospect of recovering a nearly lost language, the idiom and scrappy slang of the postwar period …

—

We need to explicate the ways in which specific themes, fears, forms of consciousness, and class relationships are embedded in the use of Africanist idiom …

—

The expression “give way,” meaning “retreat,” is an idiom.

rock and roll and other musical idioms

a feature of modern jazz idiom

See More

Recent Examples on the Web

At a launch event in Beijing, Baidu’s bot named a company and gave it a slogan, wrote a 600-word business newsletter, explained economic theory, and wrote a poem based on a Chinese idiom.

—

Merve: Or just other ways in which the language was either updated or nationalized or globalized, converted into this global American idiom.

—

It was stylistically influenced by the musical idioms of one of his mentors, the Jewish composer Giacomo Meyerbeer.

—

Jazz was a familiar idiom for Docter to explore.

—

The idiom is used advisedly, as murderous impulses, a wicked delight in the macabre and the grotesque, witches and erstwhile witches animate the pages of this collection.

—

Friends and collaborators agree that the Hated not only resist reflexive muso taxonomy, but also those too-tidy creation myths where an entire musical idiom can allegedly spring from a lone source.

—

Raimi’s sheer passion for his material can sometimes overwhelm the coherence of his storytelling, and his unfashionable sincerity doesn’t always mesh with the breezy quip-a-minute tone that is the Marvel enterprise’s preferred comic idiom.

—

Scarpa’s work on the villa itself, and on the barn — where Federico now lives with his wife, Natalia — is more subdued, operating unostentatiously within the rural idiom.

—

See More

These examples are programmatically compiled from various online sources to illustrate current usage of the word ‘idiom.’ Any opinions expressed in the examples do not represent those of Merriam-Webster or its editors. Send us feedback about these examples.

Word History

Etymology

Middle French & Late Latin; Middle French idiome, from Late Latin idioma individual peculiarity of language, from Greek idiōmat-, idiōma, from idiousthai to appropriate, from idios

First Known Use

1575, in the meaning defined at sense 2a

Time Traveler

The first known use of idiom was

in 1575

Dictionary Entries Near idiom

Cite this Entry

“Idiom.” Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary, Merriam-Webster, https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/idiom. Accessed 13 Apr. 2023.

Share

More from Merriam-Webster on idiom

Last Updated:

12 Apr 2023

— Updated example sentences

Subscribe to America’s largest dictionary and get thousands more definitions and advanced search—ad free!

Merriam-Webster unabridged

id·i·om

(ĭd′ē-əm)

n.

1. A speech form or an expression of a given language that is peculiar to itself grammatically or cannot be understood from the individual meanings of its elements, as in keep tabs on.

2. The specific grammatical, syntactic, and structural character of a given language.

3. Regional speech or dialect.

4. A specialized vocabulary used by a group of people; jargon: legal idiom.

5. A style of artistic expression characteristic of a particular individual, school, period, or medium: the idiom of the French impressionists; the punk rock idiom.

[Late Latin idiōma, idiōmat-, from Greek, from idiousthai, to make one’s own, from idios, own, personal, private; see s(w)e- in Indo-European roots.]

American Heritage® Dictionary of the English Language, Fifth Edition. Copyright © 2016 by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company. Published by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company. All rights reserved.

idiom

(ˈɪdɪəm)

n

1. (Linguistics) a group of words whose meaning cannot be predicted from the meanings of the constituent words, as for example (It was raining) cats and dogs

2. (Linguistics) linguistic usage that is grammatical and natural to native speakers of a language

3. (Linguistics) the characteristic vocabulary or usage of a specific human group or subject

4. (Art Terms) the characteristic artistic style of an individual, school, period, etc

[C16: from Latin idiōma peculiarity of language, from Greek; see idio-]

idiomatic, ˌidioˈmatical adj

ˌidioˈmatically adv

ˌidioˈmaticalness n

Collins English Dictionary – Complete and Unabridged, 12th Edition 2014 © HarperCollins Publishers 1991, 1994, 1998, 2000, 2003, 2006, 2007, 2009, 2011, 2014

id•i•om

(ˈɪd i əm)

n.

1. an expression whose meaning is not predictable from the usual grammatical rules of a language or from the usual meanings of its constituent elements, as kick the bucket “to die.”

2. a language, dialect, or style of speaking peculiar to a people.

3. a construction or expression peculiar to a language.

4. the manner of expression characteristic of or peculiar to a language.

5. a distinct style or character, as in music or art.

[1565–75; < Latin idiōma < Greek idíōma peculiarity, specific property]

Random House Kernerman Webster’s College Dictionary, © 2010 K Dictionaries Ltd. Copyright 2005, 1997, 1991 by Random House, Inc. All rights reserved.

idiom

A group of words with a meaning that cannot be deduced from its constituent parts, such as “at the end of my tether;” also used to mean the vocabulary of a particular group.

Dictionary of Unfamiliar Words by Diagram Group Copyright © 2008 by Diagram Visual Information Limited

ThesaurusAntonymsRelated WordsSynonymsLegend:

| Noun | 1. | idiom — a manner of speaking that is natural to native speakers of a language

parlance formulation, expression — the style of expressing yourself; «he suggested a better formulation»; «his manner of expression showed how much he cared» |

| 2. |  idiom — the usage or vocabulary that is characteristic of a specific group of people; «the immigrants spoke an odd dialect of English»; «he has a strong German accent»; «it has been said that a language is a dialect with an army and navy» idiom — the usage or vocabulary that is characteristic of a specific group of people; «the immigrants spoke an odd dialect of English»; «he has a strong German accent»; «it has been said that a language is a dialect with an army and navy»

dialect, accent non-standard speech — speech that differs from the usual accepted, easily recognizable speech of native adult members of a speech community eye dialect — the use of misspellings to identify a colloquial or uneducated speaker patois — a regional dialect of a language (especially French); usually considered substandard spang, bang — leap, jerk, bang; «Bullets spanged into the trees» forrad, forrard, forward, forwards, frontward, frontwards — at or to or toward the front; «he faced forward»; «step forward»; «she practiced sewing backward as well as frontward on her new sewing machine»; (`forrad’ and `forrard’ are dialectal variations) |

|

| 3. |  idiom — the style of a particular artist or school or movement; «an imaginative orchestral idiom» idiom — the style of a particular artist or school or movement; «an imaginative orchestral idiom»

artistic style baroqueness, baroque — elaborate and extensive ornamentation in decorative art and architecture that flourished in Europe in the 17th century classical style — the artistic style of ancient Greek art with its emphasis on proportion and harmony order — (architecture) one of original three styles of Greek architecture distinguished by the type of column and entablature used or a style developed from the original three by the Romans rococo — fanciful but graceful asymmetric ornamentation in art and architecture that originated in France in the 18th century fashion, manner, mode, style, way — how something is done or how it happens; «her dignified manner»; «his rapid manner of talking»; «their nomadic mode of existence»; «in the characteristic New York style»; «a lonely way of life»; «in an abrasive fashion» High Renaissance — the artistic style of early 16th century painting in Florence and Rome; characterized by technical mastery and heroic composition and humanistic content treatment — a manner of dealing with something artistically; «his treatment of space borrows from Italian architecture» neoclassicism — revival of a classical style (in art or literature or architecture or music) but from a new perspective or with a new motivation classicalism, classicism — a movement in literature and art during the 17th and 18th centuries in Europe that favored rationality and restraint and strict forms; «classicism often derived its models from the ancient Greeks and Romans» Romantic Movement, Romanticism — a movement in literature and art during the late 18th and early 19th centuries that celebrated nature rather than civilization; «Romanticism valued imagination and emotion over rationality» |

|

| 4. | idiom — an expression whose meanings cannot be inferred from the meanings of the words that make it up

idiomatic expression, phrasal idiom, set phrase, phrase locution, saying, expression — a word or phrase that particular people use in particular situations; «pardon the expression» ruralism, rusticism — a rural idiom or expression in the lurch — in a difficult or vulnerable position; «he resigned and left me in the lurch» like clockwork — with regularity and precision; «the rocket launch went off like clockwork» |

Based on WordNet 3.0, Farlex clipart collection. © 2003-2012 Princeton University, Farlex Inc.

idiom

Collins Thesaurus of the English Language – Complete and Unabridged 2nd Edition. 2002 © HarperCollins Publishers 1995, 2002

idiom

noun

Specialized expressions indigenous to a particular field, subject, trade, or subculture:

argot, cant, dialect, jargon, language, lexicon, lingo, patois, terminology, vernacular, vocabulary.

The American Heritage® Roget’s Thesaurus. Copyright © 2013, 2014 by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company. Published by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company. All rights reserved.

Translations

تعابير اللغة بصورة عامَّهتَعْبير إصْطِلاحي

idiomjazyk

idiomsprogsprogbrugtalemådeudtryksform

idiotismo

اصطلاحزبان زد زبانزد

idiomikädenjälkikäsialakielipuheenparsi

idióma

málvenjaorîatiltæki, orîtak

成句方言様式熟語訛り

idiomaidiomatinisidiomatiškaisavita kalbasavitas

idioma, savdabīgs izteiciensidiomātisks izteiciens

idiom

expressão idiomáticaidioma

idióm

fraza

idiom

idiom

[ˈɪdɪəm] N

2. (= style of expression) → lenguaje m

Collins Spanish Dictionary — Complete and Unabridged 8th Edition 2005 © William Collins Sons & Co. Ltd. 1971, 1988 © HarperCollins Publishers 1992, 1993, 1996, 1997, 2000, 2003, 2005

Collins English/French Electronic Resource. © HarperCollins Publishers 2005

idiom

Collins German Dictionary – Complete and Unabridged 7th Edition 2005. © William Collins Sons & Co. Ltd. 1980 © HarperCollins Publishers 1991, 1997, 1999, 2004, 2005, 2007

idiom

[ˈɪdɪəm] n (phrase) → locuzione f idiomatica; (style of expression) → stile m

Collins Italian Dictionary 1st Edition © HarperCollins Publishers 1995

idiom

(ˈidiəm) noun

1. an expression with a meaning that cannot be guessed from the meanings of the individual words. His mother passed away (= died) this morning.

2. the expressions of a language in general. English idiom.

ˌidioˈmatic (-ˈmӕtik) adjective

(negative unidiomatic).

1. using an idiom. an idiomatic use of this word.

2. using appropriate idioms. We try to teach idiomatic English.

ˌidioˈmatically adverb

Kernerman English Multilingual Dictionary © 2006-2013 K Dictionaries Ltd.

Definition and Examples of English Idioms

The idiomatic phrase «ugly duckling» refers to someone who starts out awkward but eventually exceed exceptions.

Wraithimages / Getty Images

Updated on November 04, 2019

An idiom is a set expression of two or more words that mean something other than the literal meanings of its individual words. Adjective: idiomatic.

«Idioms are the idiosyncrasies of a language,» says Christine Ammer. «Often defying the rules of logic, they pose great difficulties for non-native speakers» (The American Heritage Dictionary of Idioms, 2013).

Pronunciation: ID-ee-um

Etymology: From the Latin, «own, personal, private»

Examples and Observations

- «Every cloud has its silver lining but it is sometimes a little difficult to get it to the mint.»

(Don Marquis) - «Fads are the kiss of death. When the fad goes away, you go with it.»

(Conway Twitty) - «We may have started by beating about the bush, but we ended by barking up the wrong tree.»

(P. M. S. Hacker, Human Nature: The Categorial Framework. Wiley, 2011) - «I worked the graveyard shift with old people, which was really demoralizing because the old people didn’t have a chance in hell of ever getting out.»

(Kate Millett) - «Some of the places they used for repairs, Bill said, had taken to calling themselves ‘auto restoration facilities’ and charging an arm and a leg.»

(Jim Sterba, Frankie’s Place: A Love Story. Grove, 2003) - «If we could just agree to disagree and not get all bent out of shape. That was one of the main things we decided in therapy.”

(Clyde Edgerton, Raney. Algonquin, 1985) - «Chloe decided that Skylar was the big cheese. She called the shots and dominated the conversation.»

(Jeanette Baker, Chesapeake Tide. Mira, 2004) - «Anytime they came up short on food, they yanked one of the pigs out of the pen, slit its throat, and went on a steady diet of pig meat.»

(Jimmy Breslin, The Short Sweet Dream of Eduardo Gutierrez. Three Rivers Press, 2002) - «Mrs. Brofusem is prone to malapropisms and mangled idioms, as when she says she wishes to ‘kill one bird with two stones’ and teases Mr. Onyimdzi for having a white girl ‘in’ (rather than ‘up’) his sleeve.»

(Catherine M. Cole, Ghana’s Concert Party Theatre. Indiana University Press, 2001) - «‘Just the normal filling for you today then?’ Blossom enquires at her usual breakneck speed, blinking rapidly. She’s got one brown eye and one blue, suiting her quirky style. ‘The ball’s in your shoe!’

«The saying, of course, is the ball’s in your court, but Blossom is always getting her idioms mixed up.»

(Carla Caruso, Cityglitter. Penguin, 2012)

Functions of Idioms

- «People use idioms to make their language richer and more colorful and to convey subtle shades of meaning or intention. Idioms are used often to replace a literal word or expression, and many times the idiom better describes the full nuance of meaning. Idioms and idiomatic expressions can be more precise than the literal words, often using fewer words but saying more. For example, the expression it runs in the family is shorter and more succinct than saying that a physical or personality trait ‘is fairly common throughout one’s extended family and over a number of generations.'»

(Gail Brenner, Webster’s New World American Idioms Handbook. Webster’s New World, 2003)

Idioms and Culture

- «If natural language had been designed by a logician, idioms would not exist.»

(Philip Johnson-Laird, 1993) - «Idioms, in general, are deeply connected to culture. . . . Agar (1991) proposes that biculturalism and bilingualism are two sides of the same coin. Engaged in the intertwined process of culture change, learners have to understand the full meaning of idioms.»

(Sam Glucksberg, Understanding Figurative Language. Oxford University Press, 2001)

Shakespeare’s Idioms

- «Shakespeare is credited with coining more than 2,000 words, infusing thousands more existing ones with electrifying new meanings and forging idioms that would last for centuries. ‘A fool’s paradise,’ ‘at one fell swoop,’ ‘heart’s content,’ ‘in a pickle,’ ‘send him packing,’ ‘too much of a good thing,’ ‘the game is up,’ ‘good riddance,’ ‘love is blind,’ and ‘a sorry sight,’ to name a few.»

(David Wolman, Righting the Mother Tongue: From Olde English to Email, the Tangled Story of English Spelling. Harper, 2010)

Levels of «Transparency»

- «Idioms vary in ‘transparency’: that is, whether their meaning can be derived from the literal meanings of the individual words. For example, make up [one’s] mind is rather transparent in suggesting the meaning ‘reach a decision,’ while kick the bucket is far from transparent in representing the meaning ‘die.'» (Douglas Biber et al., Longman Student Grammar of Spoken and Written English. Pearson, 2002)

- «The thought hit me that this was a pretty pathetic way to kick the bucket—being accidentally poisoned during a photo shoot, of all things—and I started weeping at the idiocy of it all.» (Lara St. John)

The Idiom Principle

- «The observation that meanings are made in chunks of language that are more or less predictable, though not fixed, sequences of morphemes leads [John] Sinclair [in Corpus Concordance Collocation, 1991] to an articulation of the ‘idiom principle.’ He states the principle thus:

The principle of idiom is that a language user has available to him or her a large number of semi-preconstructed phrases that constitute single choices, even though they might appear to be analysable into segments (Sinclair 1991): 110)

- The study of fixed phrases has a fairly long tradition…but phrases are normally seen as outside the normal organizing principle of language. Here, Sinclair extends the notion of phraseology to encompass a great deal more of language than it is commonly considered to encompass. At its strongest, we might say that all senses of all words exist in and are identified by the sequences of morphemes in which they typically occur.» (Susan Hunston and Gill Francis, Pattern Grammar: A Corpus-Driven Approach to the Lexical Grammar of English. John Benjamins, 2000)

Modal Idioms

- «Modal idioms are idiosyncratic verbal formations which consist of more than one word and which have modal meanings that are not predictable from the constituent parts (compare the non-modal idiom kick the bucket). Under this heading we include have got [to], had better/best, would rather/sooner/as soon, and be [to].» (Bas Aarts, Oxford Modern English Grammar. Oxford University Press, 2011)

The Lighter Side of Idioms

Kirk: If we play our cards right, we may be able to find out when those whales are being released.

Spock: How will playing cards help? (Captain James T. Kirk and Spock in Star Trek IV: The Voyage Home, 1986)