1

a

: descent with modification from preexisting species : cumulative inherited change in a population of organisms through time leading to the appearance of new forms : the process by which new species or populations of living things develop from preexisting forms through successive generations

Evolution is a process of continuous branching and diversification from common trunks. This pattern of irreversible separation gives life’s history its basic directionality.—

also

: the scientific theory explaining the appearance of new species and varieties through the action of various biological mechanisms (such as natural selection, genetic mutation or drift, and hybridization)

Since 1950, developments in molecular biology have had a growing influence on the theory of evolution. —

In Darwinian evolution, the basic mechanism is genetic mutation, followed by selection of the organisms most likely to survive. —

b

: the historical development of a biological group (such as a species) : phylogeny

2

a

: a process of change in a certain direction : unfolding

b

: the action or an instance of forming and giving something off : emission

c(1)

: a process of continuous change from a lower, simpler, or worse to a higher, more complex, or better state : growth

(2)

: a process of gradual and relatively peaceful social, political, and economic advance

3

: the process of working out or developing

4

: the extraction of a mathematical root

5

: a process in which the whole universe is a progression of interrelated phenomena

6

: one of a set of prescribed movements

evolutionist

noun or adjective

Synonyms

Example Sentences

changes brought about by evolution

an important step in the evolution of computers

Recent Examples on the Web

But across nearly two hours in Port St. Lucie late last month, trailed by Christie and two communications aides, Cohen insisted that age and perspective had dulled his edges, straining to project an emotional evolution, to a point.

—

An early addition to Drew’s staff in 2003, Tang was one of the key players behind Baylor’s evolution from a program in shambles following the scandalous Dave Bliss era into one of the top teams in the sport and a national champion.

—

Napa’s evolution from a quiet farming town to a top tourist destination is on full display at Frank Family.

—

The adoption of voice recognition and AI as new channels for patient care is helping to drive this evolution.

—

The first study, published in the journal Astronomy & Astrophysics Letters, utilized an instrument called a Multi Unit Spectroscopic Explorer (MUSE) to follow the evolution of the cloud of debris from the collision for a month.

—

Still, the character’s evolution from pitchman to sitcom main character has been remarkably successful.

—

Enlarge Anton Petrus Generation over generation, catch after catch, fishing changes fish evolution.

—

No longer a hawk: NBC News’ Henry J. Gomez, Phil McCausland and Jonathan Allen explore Florida GOP Gov. Ron DeSantis’ evolution on defense issues.

—

See More

These examples are programmatically compiled from various online sources to illustrate current usage of the word ‘evolution.’ Any opinions expressed in the examples do not represent those of Merriam-Webster or its editors. Send us feedback about these examples.

Word History

Etymology

borrowed from New Latin ēvolūtiōn-, ēvolūtiō «unfolding of a curve (in geometry), emergence from an enclosing structure, historical development,» going back to Medieval Latin, «unfolding of a tale, lapse of time,» going back to Latin, «unrolling of a papyrus scroll while reading it,» from ēvolū-, variant stem of ēvolvere «to roll out or away, unwind, unroll» + -tiōn-, -tiō, suffix of verbal action — more at evolve

First Known Use

1616, in the meaning defined at sense 6

Time Traveler

The first known use of evolution was

in 1616

Dictionary Entries Near evolution

Cite this Entry

“Evolution.” Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary, Merriam-Webster, https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/evolution. Accessed 13 Apr. 2023.

Share

More from Merriam-Webster on evolution

Last Updated:

30 Mar 2023

— Updated example sentences

Subscribe to America’s largest dictionary and get thousands more definitions and advanced search—ad free!

Merriam-Webster unabridged

Evolution is a biological process. It is how living things change over time and how new species develop. The theory of evolution explains how evolution works, and how living and extinct things have come to be the way they are.[1] The theory of evolution is a very important idea in biology. Theodosius Dobzhansky, a well-known evolutionary biologist, said: «Nothing in biology makes sense except in the light of evolution».[2]

Evolution has been happening since life started on Earth and is happening now. Evolution is caused mostly by natural selection. Living things are not identical to each other. Even living things of the same species look, move, and behave differently to some extent. Some differences make it easier for living things to survive and reproduce. Differences may make it easier to find food, hide from danger, or give birth to offspring which survive. The offspring have some of the things which made it easier for their parents to have them. Over time, these differences continue, and living things change enough to become new species.

It is known that living things have changed over time, because their remains can be seen in the rocks. These remains are called ‘fossils’. This proves that the animals and plants of today are different from those of long ago. The older the fossils, the bigger the differences from modern forms.[3] This has happened because evolution has taken place. That evolution has taken place is a fact, because it is overwhelmingly supported by many lines of evidence.[4][5][6] At the same time, evolutionary questions are still being actively researched by biologists.

Comparison of DNA sequences allows organisms to be grouped by how similar their sequences are. In 2010 an analysis compared sequences to phylogenetic trees, and supported the idea of common descent. There is now «strong quantitative support, by a formal test»,[7] for the unity of life.[8]

Evidence[change | change source]

-4500 —

–

-4250 —

–

-4000 —

–

-3750 —

–

-3500 —

–

-3250 —

–

-3000 —

–

-2750 —

–

-2500 —

–

-2250 —

–

-2000 —

–

-1750 —

–

-1500 —

–

-1250 —

–

-1000 —

–

-750 —

–

-500 —

–

-250 —

–

0 —

-13 —

–

-12 —

–

-11 —

–

-10 —

–

-9 —

–

-8 —

–

-7 —

–

-6 —

–

-5 —

–

-4 —

–

-3 —

–

-2 —

–

-1 —

–

0 —

The evidence for evolution is given in a number of books.[9][10][11][12] Some of this evidence is discussed here.

Fossils show that change has occurred[change | change source]

The realization that some rocks contain fossils was a very important event in natural history. There are three parts to this story:

1. The realization that things in rocks which looked organic actually were the altered remains of living things. This was settled in the 16th and 17th centuries by Conrad Gessner, Nicolaus Steno, Robert Hooke and others.[13][14]

2. The realization that many fossils represented species which do not exist today. It was Georges Cuvier, the comparative anatomist, who proved that extinction occurred and that different strata contained different fossils.[15]p108

3. The realization that early fossils were simpler organisms than later fossils. Also, the later the rocks, the more like the present day are the fossils.[16]

- «The most convincing evidence for the occurrence of evolution is the discovery of extinct organisms in older geological strata… The older the strata are…the more different the fossil will be from living representatives… that is to be expected if the fauna and flora of the earlier strata had gradually evolved into their descendants. Ernst Mayr [1]p13

Geographical distribution[change | change source]

Where species live is a topic which fascinated both Charles Darwin and Alfred Russel Wallace.[17][18][19] When new species occur, usually by the splitting of older species, this takes place in one place in the world. Once it is established, a new species may spread to some places and not others.

Australasia[change | change source]

Australasia has been separated from other continents for many millions of years. In the main part of the continent, Australia, 83% of mammals, 89% of reptiles, 90% of fish and insects, and 93% of amphibians are endemic.[20] Its native mammals are mostly marsupials like kangaroos, bandicoots, and quolls.[21] By contrast, marsupials are today totally absent from Africa and form a small portion of the mammalian fauna of South America, where opossums, shrew opossums, and the monito del monte occur (see the Great American Interchange).

The only living representatives of primitive egg-laying mammals (monotremes) are the echidnas and the platypus. They are only found in Australasia, which includes Tasmania, New Guinea, and Kangaroo Island. These monotremes are totally absent in the rest of the world.[22] On the other hand, Australia is missing many groups of placental mammals that are common on other continents (carnivora, artiodactyls, shrews, squirrels, lagomorphs), although it does have indigenous bats and rodents, which arrived later.[23]

The evolutionary story is that placental mammals evolved in Eurasia, and wiped out the marsupials and monotremes wherever they spread. They did not reach Australasia until more recently. That is the simple reason why Australia has most of the world’s marsupials and all the world’s monotremes.

Evolution of horses[change | change source]

The evolution of the horse family (Equidae) is a good example of the way that evolution works. The oldest fossil of a horse is about 52 million years old. It was a small animal with five toes on the front feet and four on the hind feet. At that time, there were more forests in the world than today. This horse lived in woodland, eating leaves, nuts and fruit with its simple teeth. It was only about as big as a fox.[24]

About 30 million years ago the world started to become cooler and drier. Forests shrank; grassland expanded, and horses changed. They ate grass, they grew larger, and they ran faster because they had to escape faster predators. Because grass wears teeth out, horses with longer-lasting teeth had an advantage.

For most of this long period of time, there were a number of horse types (genera). Now only one genus exists: the modern horse, Equus. It has teeth which grow all its life, hooves on single toes, great long legs for running, and the animal is big and strong enough to survive in the open plain.[24] Horses lived in western Canada until 12,000 years ago,[25] but all horses in North America became extinct about 11,000 years ago. The causes of this extinction are not yet clear. Climate change and over-hunting by humans are suggested.

So, scientists can see that changes have happened. They have happened slowly over a long time. How these changes have come about is explained by the theory of evolution.

Hawaiian Drosophila (fruit flies)[change | change source]

In about 6,500 sq mi (17,000 km2), the Hawaiian Islands have the most diverse collection of Drosophila flies in the world, living from rainforests to mountain meadows. About 800 Hawaiian fruit fly species are known.

Genetic evidence shows that all the native fruit fly species in Hawaiʻi have descended from a single ancestral species that came to the islands, about 20 million years ago. Later adaptive radiation was caused by a lack of competition and a wide variety of vacant niches. Although it would be possible for a single pregnant female to colonise an island, it is more likely to have been a group from the same species.[26][27][28][29]

Distribution of Glossopteris[change | change source]

Current distribution of Glossopteris on a Permian map showing the connection of the continents. (1. South America 2. Africa 3. Madagascar 4. India 5. Antarctica and 6. Australia)

The combination of continental drift and evolution can explain what is found in the fossil record. Glossopteris is an extinct species of seed fern plants from the Permian period on the ancient supercontinent of Gondwana.[30]

Glossopteris fossils are found in Permian strata in southeast South America, southeast Africa, all of Madagascar, northern India, all of Australia, all of New Zealand, and scattered on the southern and northern edges of Antarctica.

During the Permian, these continents were connected as Gondwana. This is known from magnetic striping in the rocks, other fossil distributions, and glacial scratches pointing away from the temperate climate of the South Pole during the Permian.[11]p103

Common descent[change | change source]

When biologists look at living things, they see that animals and plants belong to groups which have something in common. Charles Darwin explained that this followed naturally if «we admit the common parentage of allied forms, together with their modification through variation and natural selection».[17]p402[9]p456

For example, all insects are related. They share a basic body plan, whose development is controlled by master regulatory genes.[31] They have six legs; they have hard parts on the outside of the body (an exoskeleton); they have eyes formed of many separate chambers, and so on. Biologists explain this with evolution. All insects are the descendants of a group of animals who lived a long time ago. They still keep the basic plan (six legs and so on) but the details change. They look different now because they changed in different ways: this is evolution.[32]

It was Darwin who first suggested that all life on Earth had a single origin, and from that beginning «endless forms most beautiful and most wonderful have been, and are being, evolved».[9]p490[17] Evidence from molecular biology in recent years has supported the idea that all life is related by common descent.[33]

Vestigial structures[change | change source]

Strong evidence for common descent comes from vestigial structures.[17]p397 The useless wings of flightless beetles are sealed under fused wing covers. This can be simply explained by their descent from ancestral beetles which had wings that worked.[12]p49

Rudimentary body parts, those that are smaller and simpler in structure than corresponding parts in ancestral species, are called vestigial organs. Those organs are functional in the ancestral species but are now either nonfunctional or re-adapted to a new function. Examples are the pelvic girdles of whales, halteres (hind wings) of flies, wings of flightless birds, and the leaves of some xerophytes (e.g. cactus) and parasitic plants (e.g. dodder).

However, vestigial structures may have their original function replaced with another. For example, the halteres in flies help balance the insect while in flight, and the wings of ostriches are used in mating rituals and aggressive displays. The ear ossicles in mammals are former bones of the lower jaw.

- «Rudimentary organs plainly declare their origin and meaning…» (p262). «Rudimentary organs… are the record of a former state of things, and have been retained solely through the powers of inheritance… far from being a difficulty, as they assuredly do on the old doctrine of creation, might even have been anticipated in accordance with the views here explained» (p402). Charles Darwin.[17]

In 1893, Robert Wiedersheim published a book on human anatomy and its relevance to man’s evolutionary history. This book contained a list of 86 human organs that he considered vestigial.[34] This list included examples such as the appendix and the 3rd molar teeth (wisdom teeth).

The strong grip of a baby is another example.[35] It is a vestigial reflex, a remnant of the past when pre-human babies clung to their mothers’ hair as the mothers swung through the trees. Human babies’ feet curl up when they are sitting down, while primate babies can grip with their feet as well. All primates except modern man have thick body hair which an infant can grasp, unlike modern humans. The grasp reflex allows the mother to escape danger by climbing a tree using both hands and feet.[11][36]

Vestigial organs often have some selection against them. The original organs take resources to build and maintain. If they no longer have a function, reducing their size improves fitness. There is direct evidence of selection. Some cave crustacea reproduce more successfully with smaller eyes than do those with larger eyes. This may be because the nervous tissue dealing with sight now becomes available to handle other sensory input.[37]p310

Embryology[change | change source]

From the eighteenth century, it was known that embryos of different species were much more similar than the adults. In particular, some parts of embryos reflect their evolutionary past. For example, the embryos of land vertebrates develop gill slits like fish embryos. Of course, this is only a temporary stage, which gives rise to many structures in the neck of reptiles, birds, and mammals. The proto-gill slits are part of a complicated system of development: that is why they persisted.[31]

Another example is the embryonic teeth of baleen whales.[38] They are later lost. The baleen filter is developed from different tissue, called keratin. Early fossil baleen whales did actually have teeth as well as the baleen.[39]

A good example is the barnacle. It took many centuries before natural historians discovered that barnacles were crustacea. Their adults look so unlike other crustacea, but their larvae are very similar to those of other crustacea.[40]

Artificial selection[change | change source]

This mixed-breed Chihuahua and Great Dane show the range of dog breed sizes produced by artificial selection.

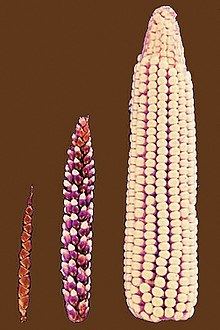

Selective breeding transformed teosinte’s few fruit cases (left) into modern corn’s rows of exposed kernels (right).

Charles Darwin lived in a world where animal husbandry and domesticated crops were vitally important. In both cases, farmers selected individuals for breeding that had desirable characteristics and prevented the breeding of individuals with less desirable characteristics. The eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries saw growth in scientific agriculture. Some of that growth was due to artificial breeding.

Darwin discussed artificial selection as a model for natural selection in the 1859 first edition of his work On the Origin of Species, in Chapter IV: Natural selection:

- «Slow though the process of selection may be, if feeble man can do much by his powers of artificial selection, I can see no limit to the amount of change… which may be effected in the long course of time by nature’s power of selection».[9]p109[41]

Rye is a now a crop. Originally it was a mimetic weed of wheat

Nikolai Vavilov showed that rye, originally a weed, came to be a crop plant by unintentional selection. Rye is a tougher plant than wheat: it survives in harsher conditions. Having become a crop like wheat, rye was able to become a crop plant in harsh areas, such as hills and mountains.[42][43]

There is no real difference in the genetic processes underlying artificial and natural selection, and the concept of artificial selection was used by Charles Darwin as an illustration of the wider process of natural selection. There are practical differences. Experimental studies of artificial selection show that «the rate of evolution in selection experiments is at least two orders of magnitude (that is 100 times) greater than any rate seen in nature or the fossil record».[44]p157

Artificial new species[change | change source]

Some have thought that artificial selection could not produce new species. It now seems that it can.

New species have been created by domesticated animal husbandry, but the details are not known or not clear. For example, domestic sheep were created by hybridisation, and no longer produce viable offspring with Ovis orientalis, one species from which they are descended.[45] Domestic cattle, on the other hand, can be considered the same species as several varieties of wild ox, gaur, yak, etc., as they readily produce fertile offspring with them.[46]

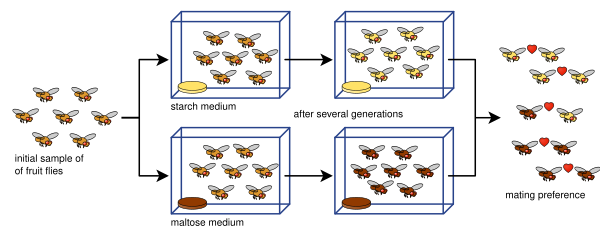

The best-documented new species came from laboratory experiments in the late 1980s. William Rice and G.W. Salt bred fruit flies, Drosophila melanogaster, using a maze with three different choices of habitat such as light/dark and wet/dry. Each generation was put into the maze, and the groups of flies that came out of two of the eight exits were set apart to breed with each other in their respective groups.

After thirty-five generations, the two groups and their offspring were isolated reproductively because of their strong habitat preferences: they mated only within the areas they preferred, and so did not mate with flies that preferred the other areas.[47][48]

Diane Dodd was also able to show how reproductive isolation can develop from mating preferences in Drosophila pseudoobscura fruit flies after only eight generations using different food types, starch, and maltose.[49]

Dodd’s experiment has been easy for others to repeat. It has also been done with other fruit flies and foods.[50]

Observable changes[change | change source]

Some biologists say that evolution has happened when a trait that is caused by genetics becomes more or less common in a group of organisms.[51] Others call it evolution when new species appear.

Changes can happen quickly in smaller, simpler organisms. For example, many bacteria that cause disease can no longer be killed with some antibiotic medicines. These medicines have only been in use since the 1940s, and at first, they worked extremely well. The bacteria have evolved so that they are less affected by antibiotics.[52] The drugs killed off all the bacteria except a few which had some resistance. These few resistant bacteria reproduced, and their offspring had the same drug resistance.

The Colorado beetle is famous for its ability to resist pesticides. Over the last 50 years it has become resistant to 52 chemical compounds used in insecticides, including cyanide.[53] This is natural selection sped up by artificial conditions. However, not every population is resistant to every chemical.[54] The populations only become resistant to chemicals used in their area.

History[change | change source]

-10 —

–

-9 —

–

-8 —

–

-7 —

–

-6 —

–

-5 —

–

-4 —

–

-3 —

–

-2 —

–

-1 —

–

0 —

Although there were a number of natural historians in the 18th century who had some idea of evolution, the first well-formed ideas came in the 19th century. Four biologists are considered the most important.

Lamarck[change | change source]

Jean-Baptiste de Lamarck (1744–1829), a French biologist, claimed that animals changed according to natural laws. He said that animals could pass on traits they had acquired during their lifetime to their offspring, using inheritance. Today, his theory is known as Lamarckism. Its main purpose is to explain adaptations by natural means.[55] He proposed a tendency for organisms to become more complex, moving up a ladder of progress, plus use and disuse.

Lamarck’s idea was that a giraffe’s neck grew longer because it tried to reach higher up. This idea failed because it conflicts with heredity (Mendel’s work). Mendel made his discoveries about half a century after Lamarck’s work.

Darwin[change | change source]

Charles Darwin (1809–1882) wrote his On the Origin of Species in 1859. In this book, he put forward much evidence that evolution had occurred. He also proposed natural selection as the way evolution had taken place. But Darwin did not understand genetics and how traits were actually passed on. He could not accurately explain what made children look like their parents.

Nevertheless, Darwin’s explanation of evolution was fundamentally correct. In contrast to Lamarck, Darwin’s idea was that the giraffe’s neck became longer because those with longer necks survived better.[17]p177/9 These survivors passed their genes on, and in time the whole species got longer necks.

Wallace[change | change source]

Alfred Russel Wallace OM FRS (1823–1913) was a British naturalist, explorer, biologist, and social activist. He proposed a theory of natural selection at about the same time as Darwin. His idea was published in 1858 together with Charles Darwin’s idea.

Mendel[change | change source]

An Austrian monk called Gregor Mendel (1822–1884) bred plants. In the mid-19th century, he discovered how traits were passed on from one generation to the next.

He used peas for his experiments: some peas have white flowers and others have red ones. Some peas have green seeds and others have yellow seeds. Mendel used artificial pollination to breed the peas. His results are discussed further in Mendelian inheritance. Darwin thought that the inheritance from both parents blended together. Mendel proved that the genes from the two parents stay separate, and may be passed on unchanged to later generations.

Mendel published his results in a journal that was not well-known, and his discoveries were overlooked. Around 1900, his work was rediscovered.[56][57] Genes are bits of information made of DNA which work like a set of instructions. A set of genes are in every living cell. Together, genes organise the way an egg develops into an adult. With mammals, and many other living things, a copy of each gene comes from the father and another copy from the mother. Some living organisms, including some plants, only have one parent, so get all their genes from them. These genes produce the genetic differences that evolution acts on.

Darwin’s theory[change | change source]

Darwin’s On the Origin of Species has two themes: the evidence for evolution, and his ideas on how evolution took place. This section deals with the second issue.

Variation[change | change source]

The members of this family are similar in some ways, different in others

Variation. The flower on the right has a different colour.

The first two chapters of the Origin deal with variations in domesticated plants and animals, and variations in nature.

All living things show variation. Every population which has been studied shows that animals and plants vary as much as humans do.[58][59]p90 This is a great fact of nature, and without it evolution would not occur. Darwin said that, just as man selects what he wants in his farm animals, so in nature the variations allow natural selection to work.[60]

The features of an individual are influenced by two things, heredity and environment. First, development is controlled by genes inherited from the parents. Second, living brings its own influences. Some things are entirely inherited, others partly, and some not inherited at all.

The colour of eyes is entirely inherited; they are a genetic trait. Height or weight is only partly inherited, and language is not at all inherited. The fact that humans can speak is inherited, but what language is spoken depends on where a person lives and what they are taught. Another example: a person inherits a brain of somewhat variable capacity. What happens after birth depends on many things such as home environment, education, and other experiences. When a person is an adult, their brain is what their inheritance and life experience have made it.

Evolution only concerns the traits which can be inherited, wholly or partly. The hereditary traits are passed on from one generation to the next through genes. A person’s genes contain all the characteristics that they inherit from their parents. The accidents of life are not passed on. Each person lives a somewhat different life, which increases the differences.

Organisms in any population vary in reproductive success.[61]p81 From the point of view of evolution, ‘reproductive success’ means the total number of offspring which live to breed and leave offspring themselves.

Inherited variation[change | change source]

Variation can only affect future generations if it is inherited. Because of the work of Gregor Mendel, we know that much variation is inherited. Mendel’s ‘factors’ are now called genes. Research has shown that almost every individual in a sexually reproducing species is genetically unique.[62]p204

Genetic variation is increased by gene mutations. DNA does not always reproduce exactly. Rare changes occur, and these changes can be inherited. Many changes in DNA cause faults; some are neutral or even advantageous. This gives rise to genetic variation, which is the seed corn of evolution. Sexual reproduction, by the crossing over of chromosomes during meiosis, spreads variation through the population. Other events, like natural selection and drift, reduce variation. A population in the wild always has variation, but the details are always changing.[59]p90

Natural selection[change | change source]

Evolution mainly works by natural selection. What does this mean? Animals and plants which are best suited to their environment will, on average, survive better. There is a struggle for existence. Those who survive will reproduce and create the next generation. Their genes will be passed on, and the genes of those who did not reproduce will not. This is the basic mechanism which changes the characteristics of a population and causes evolution.

Natural selection explains why living organisms change over time, and explains the anatomy, functions, and behavior that they have. It works like this:

- All living things have such fertility that their population size could increase rapidly forever.

- However, population sizes do not increase forever. Mostly, population sizes remain about the same.

- Food and other resources are limited. Therefore, there is competition for food and resources.

- No two individuals are alike. Therefore, they will not have the same chances to live and reproduce.

- Much of this variation can be inherited. Parents pass traits to their children through their genes.

- The next generation can only come from those that survive and reproduce. After many generations of this, the population will have more helpful genetic differences, and fewer harmful ones.[63] Natural selection is really a process of elimination.[1]p117 The elimination is being caused by the relative fit between individuals and the environment they live in.

Selection in natural populations[change | change source]

There are now many cases where natural selection has been proved to occur in wild populations.[4][64][65] Almost every case investigated of camouflage, mimicry and polymorphism has shown strong effects of selection.[66]

The force of selection can be much stronger than was thought by the early population geneticists. The resistance to pesticides has grown quickly. Resistance to warfarin in Norway rats (Rattus norvegicus) grew rapidly because those that survived made up more and more of the population. Research showed that, in the absence of warfarin, the resistant homozygote was at a 54% disadvantage to the normal wild type homozygote.[59]p182[67] This great disadvantage was quickly overcome by the selection for warfarin resistance.

Mammals normally cannot drink milk as adults, but humans are an exception. Milk is digested by the enzyme lactase, which switches off as mammals stop taking milk from their mothers. The human ability to drink milk during adult life is supported by a lactase mutation which prevents this switch-off. Human populations have a high proportion of this mutation wherever milk is important in the diet. The spread of this ‘milk tolerance’ is promoted by natural selection, because it helps people survive where milk is available. Genetic studies suggest that the oldest mutations causing lactase persistence only reached high levels in human populations in the last ten thousand years.[68][69] Therefore, lactase persistence is often cited as an example of recent human evolution.[70][71] As lactase persistence is genetic, but animal husbandry a cultural trait, this is gene–culture coevolution.[72]

Adaptation[change | change source]

Adaptation is one of the basic phenomena of biology.[73] Through the process of adaptation, an organism becomes better suited to its habitat.[74]

Adaptation is one of the two main processes that explain the diverse species we see in biology. The other is speciation (species-splitting or cladogenesis).[75][76] A favourite example used today to study the interplay of adaptation and speciation is the evolution of cichlid fish in African rivers and lakes.[77][78]

When people speak about adaptation they often mean something which helps an animal or plant survive. One of the most widespread adaptations in animals is the evolution of the eye. Another example is the adaptation of horses’ teeth to grinding grass. Camouflage is another adaptation; so is mimicry. The better-adapted animals are the most likely to survive and reproduce successfully (natural selection).

An internal parasite (such as a fluke) is a good example: it has a very simple bodily structure, but still the organism is highly adapted to its particular environment. From this we see that adaptation is not just a matter of visible traits: in such parasites, critical adaptations take place in the life cycle, which is often quite complex.[79]

Limitations[change | change source]

Not all features of an organism are adaptations.[59]p251 Adaptations tend to reflect the past life of a species. If a species has recently changed its life style, a once valuable adaptation may become useless, and eventually become a dwindling vestige.

Adaptations are never perfect. There are always tradeoffs between the various functions and structures in a body. It is the organism as a whole that lives and reproduces, therefore it is the complete set of adaptations that is passed on to future generations.

Genetic drift and its effect[change | change source]

Click for action

In this simulation, there is a fixation of the blue «allele» in five generations.

In populations, there are forces that add variation to the population (such as mutation), and forces that remove it. Genetic drift is the name given to random changes which remove variation from a population. Genetic drift gets rid of variation at the rate of 1/(2N) where N = population size.[44]p29 It is therefore «a very weak evolutionary force in large populations».[44]p55

Genetic drift explains how random chance can affect evolution in surprisingly big ways, but only when populations are quite small. Overall, its action is to make the individuals more similar to each other, and hence more vulnerable to disease or to chance events in their environment.

- Drift reduces genetic variation in populations, potentially reducing a population’s ability to survive new selective pressures.

- Genetic drift acts faster and has more drastic results in smaller populations. Small populations usually become extinct.

- Genetic drift may contribute to speciation (starting a new species) if the small group does survive.

- Bottleneck events: when a large population is suddenly and drastically reduced in size by some event, the genetic variety will be very much reduced. Infections and extreme climate events are frequent causes. Occasionally, invasions by more competitive species can be devastating.[80]

♦ In late 1800s, hunting reduced the Northern elephant seal to only about 20 individuals. Although the population has rebounded, its genetic variability is much less than that of the Southern elephant seal.

♦ Cheetahs have very little variation. We think the species was reduced to a small number at some recent time. Because it lacks genetic variation, it is in danger of infectious diseases.[81] - Founder events: these occur when a small group buds off from a larger population. The small group then lives separately from the main population. The human species is often quoted as having been through such stages. For example, when groups left Africa to set up elsewhere (see human evolution). Apparently, we have less variation than would be expected from our worldwide distribution.

Groups that arrive on islands far from the mainland are also good examples. These groups, by virtue of their small size, cannot carry the full range of alleles to be found in the parent population.[82][83]

Species[change | change source]

How species form is a major part of evolutionary biology. Darwin interpreted ‘evolution’ (a word he did not use at first) as being about speciation. That is why he called his famous book On the Origin of Species.

Darwin thought most species arose directly from pre-existing species. This is called anagenesis: new species by older species changing. Now we think most species arise by previous species splitting: cladogenesis.[84][85]

Species splitting[change | change source]

Two groups that start the same can become very different if they live in different places. When a species gets split into two geographical regions, a process starts. Each adapts to its own situation. After a while, individuals from one group can no longer reproduce with the other group. Two separate species have evolved from one.

A German explorer, Moritz Wagner, during his three years in Algeria in the 1830s, studied flightless beetles. Each species is confined to a stretch of the north coast between rivers which descend from the Atlas mountains to the Mediterranean. As soon as one crosses a river, a different but closely related species appears.[86] He wrote later:

- «… a [new] species will only [arise] when a few individuals [cross] the limiting borders of their range… the formation of a new race will never succeed… without a long continued separation of the colonists from the other members of their species».[87]

This was an early account of the importance of geographical separation. Another biologist who thought geographical separation was critical was Ernst Mayr.[88]

The three-spined stickleback (Gasterosteus aculeatus)

One example of natural speciation is the three-spined stickleback, a sea fish that, after the last ice age, invaded freshwater, and set up colonies in isolated lakes and streams. Over about 10,000 generations, the sticklebacks show great differences, including variations in fins, changes in the number or size of their bony plates, variable jaw structure, and colour differences.[89]

The wombats of Australia fall into two main groups, common wombats and hairy-nosed wombats. The two types look very similar, apart from the hairiness of their noses. However, they are adapted to different environments. Common wombats live in forested areas and eat mostly green food with lots of moisture. They often feed in the daytime. Hairy-nosed wombats live on hot dry plains where they eat dry grass with very little water or nutrition in it. Their metabolic rate is slow and they sleep most of the day underground.

When two groups that started the same become different enough, then they become two different species. Part of the theory of evolution is that all living things started the same, but then split into different groups over billions of years.[90]

Modern evolutionary synthesis[change | change source]

This was an important movement in evolutionary biology, which started in the 1930s and finished in the 1950s.[91][92] It has been updated regularly ever since.

The synthesis explains how the ideas of Charles Darwin fit with the discoveries of Gregor Mendel, who found out how we inherit our genes. The modern synthesis brought Darwin’s idea up to date. It bridged the gap between different types of biologists: geneticists, naturalists, and palaeontologists.

When the theory of evolution was developed, it was not clear that natural selection and genetics worked together. But Ronald Fisher showed that natural selection would work to change species.[93] Sewall Wright explained genetic drift in 1931.[94]

- Evolution and genetics: evolution can be explained by what we know about genetics, and what we see of animals and plants living in the wild.[91][92]

- Thinking in terms of populations, rather than individuals, is important. The genetic variety existing in natural populations is a key factor in evolution.[95]

- Evolution and fossils: the same factors which act today also acted in the past.[96]

- Gradualism: evolution is gradual, and usually takes place by small steps. There are some exceptions to this, notably polyploidy, especially in plants.[97][98]

- Natural selection: the struggle for existence of animals and plants in the wild causes natural selection. The strength of natural selection in the wild was greater than even Darwin expected.[65]

- Genetic drift can be important in small populations.[44]

- The rate of evolution can vary. There is very good evidence from fossils that different groups can evolve at different rates, and that different parts of an animal can evolve at different rates.[59]p292, 397

Some areas of research[change | change source]

Pollinator constancy: these two honeybees, active at the same time and place, each visit flowers from only one species: see the colour of the pollen in their baskets

Co-evolution[change | change source]

Co-evolution is where the existence of one species is tightly bound up with the life of one or more other species.

New or ‘improved’ adaptations which occur in one species are often followed by the appearance and spread of related features in the other species. The life and death of living things is intimately connected, not just with the physical environment, but with the life of other species.

These relationships may continue for millions of years, as it has in the pollination of flowering plants by insects.[99][100] The gut contents, wing structures, and mouthparts of fossilized beetles and flies suggest that they acted as early pollinators. The association between beetles and angiosperms during the Lower Cretaceous period led to parallel radiations of angiosperms and insects into the late Cretaceous. The evolution of nectaries in Upper Cretaceous flowers signals the beginning of the mutualism between hymenoptera and angiosperms.[101]

Tree of life[change | change source]

Charles Darwin was the first to use this metaphor in biology. The evolutionary tree shows the relationships among various biological groups. It includes data from DNA, RNA and protein analysis. Tree of life work is a product of traditional comparative anatomy, and modern molecular evolution and molecular clock research.

The major figure in this work is Carl Woese, who defined the Archaea, the third domain (or kingdom) of life.[102] Below is a simplified version of present-day understanding.[103]

Macroevolution[change | change source]

Macroevolution: the study of changes above the species level, and how they take place. The basic data for such a study are fossils (palaeontology) and the reconstruction of ancient environments. Some subjects whose study falls within the realm of macroevolution:

- Adaptive radiation, such as the Cambrian Explosion.

- Changes in biodiversity through time.

- Mass extinctions.

- Speciation and extinction rates.

- The debate between punctuated equilibrium and gradualism.

- The role of development in shaping evolution: heterochrony; hox genes.

- Origin of major categories: cleidoic egg; origin of birds.

It is a term of convenience: for most biologists it does not suggest any change in the process of evolution.[4][104][105]p87 For some palaeontologists, what they see in the fossil record cannot be explained just by the gradualist evolutionary synthesis.[106] They are in the minority.

Altruism and group selection[change | change source]

Altruism – the willingness of some to sacrifice themselves for others – is widespread in social animals. As explained above, the next generation can only come from those who survive and reproduce. Some biologists have thought that this meant altruism could not evolve by the normal process of selection. Instead a process called «group selection» was proposed.[107][108] Group selection refers to the idea that alleles can become fixed or spread in a population because of the benefits they bestow on groups, regardless of the alleles’ effect on the fitness of individuals within that group.

For several decades, critiques cast serious doubt on group selection as a major mechanism of evolution.[109][110][111][112]

In simple cases it can be seen at once that traditional selection suffices. For example, if one sibling sacrifices itself for three siblings, the genetic disposition for the act will be increased. This is because siblings share on average 50% of their genetic inheritance, and the sacrificial act has led to greater representation of the genes in the next generation.

Altruism is now generally seen as emerging from standard selection.[113][114][115][116][117] The warning note from Ernst Mayr, and the work of William Hamilton are both important to this discussion.[118][119]

Hamilton’s equation[change | change source]

Hamilton’s equation describes whether or not a gene for altruistic behaviour will spread in a population. The gene will spread if rxb is greater than c:

where:

Sexual reproduction[change | change source]

Main article: Sex

At first, sexual reproduction might seem to be at a disadvantage compared with asexual reproduction. In order to be advantageous, sexual reproduction (cross-fertilisation) has to overcome a two-fold disadvantage (takes two to reproduce) plus the difficulty of finding a mate. Why, then, is sex so nearly universal among eukaryotes? This is one of the oldest questions in biology.[120]

The answer has been given since Darwin’s time: because the sexual populations adapt better to changing circumstances. A recent laboratory experiment suggests this is indeed the correct explanation.[121][122]

- «When populations are outcrossed[123] genetic recombination occurs between different parental genomes. This allows beneficial mutations to escape deleterious alleles on its original background, and to combine with other beneficial alleles that arise elsewhere in the population. In selfing[124] populations, individuals are largely homozygous and recombination has no effect».[121]

In the main experiment, nematode worms were divided into two groups. One group was entirely outcrossing, the other was entirely selfing. The groups were subjected to a rugged terrain and repeatedly subjected to a mutagen.[125] After 50 generations, the selfing population showed a substantial decline in fitness (= survival), whereas the outcrossing population showed no decline. This is one of a number of studies that show sexuality to have real advantages over non-sexual types of reproduction.[126]

What evolution is used for today[change | change source]

An important activity is artificial selection for domestication. This is when people choose which animals to breed from, based on their traits. Humans have used this for thousands of years to domesticate plants and animals.[127]

More recently, it has become possible to use genetic engineering. New techniques such as ‘gene targeting’ are now available. The purpose of this is to insert new genes or knock out old genes from the genome of a plant or animal. A number of Nobel Prizes have already been awarded for this work.

However, the real purpose of studying evolution is to explain and help our understanding of biology. After all, it is the first good explanation of how living things came to be the way they are. That is a big achievement. The practical things come mostly from genetics, the science started by Gregor Mendel, and from molecular and cell biology.

Evolution gems[change | change source]

In 2010 the journal Nature selected 15 topics as ‘Evolution gems’. These were:

Gems from the fossil record[change | change source]

- Land-living ancestors of whales

- From water to land (see tetrapod)

- The origin of feathers (see origin of birds)

- The evolutionary history of teeth

- The origin of vertebrate skeleton

Gems from habitats[change | change source]

- Natural selection in speciation

- Natural selection in lizards

- A case of co-adaptation

- Differential dispersal in wild birds

- Selective survival in wild guppies

- Evolutionary history matters

Gems from molecular processes[change | change source]

- Darwin’s Galapagos finches

- Microevolution meets macroevolution

- Toxin resistance in snakes and clams

- Variation versus stability

- Nature is the oldest scientific weekly journal. The link downloads as a free text file, complete with references. The idea is to make the information available to teachers.[128]

Responses to the idea of evolution[change | change source]

Debates about the fact of evolution[change | change source]

The idea that all life evolved had been proposed before Charles Darwin published On the Origin of species. Even today, some people still discuss the concept of evolution and what it means to them, their philosophy, and their religion. Evolution does explain some things about our human nature.[130] People also talk about the social implications of evolution, for example in sociobiology.

Some people have the religious belief that life on Earth was created by a god. In order to fit in the idea of evolution with that belief, people have used ideas like guided evolution or theistic evolution. They say that evolution is real, but is being guided in some way.[15][131][132][133]

There are many different concepts of theistic evolution. Many creationists believe that the creation myth found in their religion goes against the idea of evolution.[134] As Darwin realised, the most controversial part of the evolutionary thought is what it means for human origins.

In some countries, especially in the United States, there is tension between people who accept the idea of evolution and those who do not accept it. The debate is mostly about whether evolution should be taught in schools, and in what way this should be done.[135]

Other fields, like cosmology[136] and earth science[137] also do not match with the original writings of many religious texts. These ideas were once also fiercely opposed. Death for heresy was threatened to those who wrote against the idea that Earth was the center of the universe.

Evolutionary biology is a more recent idea. Certain religious groups oppose the idea of evolution more than other religious groups do. For instance, the Roman Catholic Church now has the following position on evolution: Pope Pius XII said in his encyclical Humani Generis published in the 1950s:

- «The Church does not forbid that (…) research and discussions (..) take place with regard to the doctrine of evolution, in as far as it inquires into the origin of the human body as coming from pre-existent and living matter,» Pope Pius XII Humani Generis[138]

Pope John Paul II updated this position in 1996. He said that Evolution was «more than a hypothesis»:

- «In his encyclical Humani Generis, my predecessor Pius XII has already [said] that there is no conflict between evolution and the doctrine of the faith regarding man and his vocation. (…) Today, more than a half-century after (..) that encyclical, some new findings lead us toward the recognition of evolution as more than an hypothesis. In fact it is remarkable that this theory has had progressively greater influence on the spirit of researchers, following a series of discoveries in different scholarly disciplines,» Pope John Paul II speaking to the Pontifical Academy of Science[139]

The Anglican Communion also does not oppose the scientific account of evolution.

Using evolution for other purposes[change | change source]

Many of those who accepted evolution were not much interested in biology. They were interested in using the theory to support their own ideas on society.

Racism[change | change source]

Some people have tried to use evolution to support racism. People wanting to justify racism claimed that certain groups, such as black people, were inferior. In nature, some animals do survive better than others, and it does lead to animals better adapted to their circumstances. With humans groups from different parts of the world, all evolution can say is that each group is probably well suited to its original situation. Evolution makes no judgements about better or worse. It does not say that any human group is superior to any other.[140]

Eugenics[change | change source]

The idea of eugenics was rather different. Two things had been noticed as far back as the 18th century. One was the great success of farmers in breeding cattle and crop plants. They did this by selecting which animals or plants would produce the next generation (artificial selection). The other observation was that lower class people had more children than upper-class people. If (and it’s a big if) the higher classes were there on merit, then their lack of children was the exact reverse of what should be happening. Faster breeding in the lower classes would lead to the society getting worse.

The idea to improve the human species by selective breeding is called eugenics. The name was proposed by Francis Galton, a bright scientist who meant to do good.[141] He said that the human stock (gene pool) should be improved by selective breeding policies. This would mean that those who were considered «good stock» would receive a reward if they reproduced. However, other people suggested that those considered «bad stock» would need to undergo compulsory sterilization, prenatal testing and birth control. The German Nazi government (1933–1945) used eugenics as a cover for their extreme racial policies, with dreadful results.[142]

The problem with Galton’s idea is how to decide which features to select. There are so many different skills people could have, you could not agree who was «good stock» and who was «bad stock». There was rather more agreement on who should not be breeding. Several countries passed laws for the compulsory sterilisation of unwelcome groups.[143] Most of these laws were passed between 1900 and 1940. After World War II, disgust at what the Nazis had done squashed any more attempts at eugenics.

Algorithm design[change | change source]

Some equations can be solved using algorithms that simulate evolution. Evolutionary algorithms work like that.

[change | change source]

Another example of using ideas about evolution to support social action is social Darwinism. Social Darwinism is a term given to the ideas of the 19th century social philosopher Herbert Spencer. Spencer believed the survival of the fittest could and should be applied to commerce and human societies as a whole.

Again, some people used these ideas to claim that racism, and ruthless economic policies were justified.[144] Today, most biologists and philosophers say that the theory of evolution should not be applied to social policy.[145][146]

Controversy[change | change source]

Some people disagree with the idea of evolution. They disagree with it for a number of reasons. Most often these reasons are influenced by or based on their religious beliefs instead of science. People who do not agree with evolution usually believe in creationism or intelligent design.

Despite this, evolution is one of the most successful theories in science. People have discovered it to be useful for different kinds of research. None of the other suggestions explain things, such as fossil records, as well. So, for almost all scientists, evolution is not in doubt.[2][147][148][149]

Further reading[change | change source]

Evidence for evolution[change | change source]

These books are mostly about the evidence for evolution.

- Coyne, Jerry A. 2009 Why evolution is true. Oxford University Press, Oxford. ISBN 0670-02053-2 (pbk)

- Dawkins, Richard 2009. The greatest show on Earth. Bantam, London. ISBN 978-0-593-06173-2 (hbk)

- Futuyma D.J. 1983. Science on trial: the case for evolution. Pantheon Books, New York. ISBN 0-394-52371-7; 2nd ed 1995 Sinauer Associates, Sunderland, Massachusetts. ISBN 0-87893-184-8.

- Prothero, Donald R. 2007. Evolution: what the fossils say and why it matters. Columbia University Press, New York. ISBN 978-0-231-13962-5 (hbk)

The process of evolution[change | change source]

These books cover most evolutionary topics.

- Barton N.H; Briggs D.E.G; Eisen J.A; Goldstein D.B. & Patel N.H. 2007. Evolution. New York: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press. ISBN 978-0-879-69684-9. Strong in molecular evolution; brings together molecular biology with evolutionary concepts.

- Futuyma D.J. 1979. Evolutionary biology. 1st ed. Sinauer Associates, Sunderland, Massachusetts. ISBN 0-87893-199-6; 2nd ed 1986 Sinauer. ISBN 0-87893-188-0; 3rd ed 1998 Sinauer. ISBN 0-87893-189-9. Widely used textbook, available second-hand. For students and teachers.

- Futuyma D.J. 2005. Evolution. Sinauer Associates, Sunderland, Massachusetts. ISBN 0-87893-187-2; 2nd ed 2009 Sinauer. ISBN 978-0-87893-223-8. Successor to above; but basically a different book. For students and teachers.

- Freeman, Scott & Herron, Jon; 1997. Evolutionary analysis. Prentice Hall ISBN 0-13-568023-9; 2nd ed 2000 ISBN 0-13-017291-X; 3rd ed 2004 Cummings ISBN 978-0-13-101859-4; 4th ed 2007 Cummings ISBN 0-13-227584-8. Modern topics such as phylogenetic trees based on genomics, genetics, molecular biology. Has website: [4] Archived 2012-12-15 at the Wayback Machine For students and teachers.

- Ridley, Mark 1993. Evolution. Blackwell ISBN 0-86542-226-5; 2nd ed 1996 Wiley-Blackwell ISBN 0-86542-495-0; 3rd ed 2003 Wiley ISBN 978-1-4051-0345-9. Comprehensive: case studies, commentary, dedicated website and CD. For students and teachers.

- Mayr, Ernst. 2001. What evolution is. Weidenfeld & Nicolson, London. ISBN 0-297-60741-3. Clearly written, for a general audience.

[change | change source]

- Evolutionary biology

- Coevolution

- Human evolution

- Adaptation

- Natural selection

- Sociobiology

References[change | change source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Mayr, Ernst. 2001. What evolution is. Weidenfeld & Nicolson, London. ISBN 0-465-04426-3

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Dobzhansky, Theodosius 1973. Nothing in biology makes sense except in the light of evolution. American Biology Teacher 35, 125-129. http://www.2think.org/dobzhansky.shtml

- ↑ Levin, Harold L. 2005. The Earth through time. 8th ed, Wiley, N.Y. Chapter 6: Life on Earth: what do fossils reveal?

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Futuyma, Douglas J. 1997. Evolutionary biology, 3rd ed. Sinauer Associates. ISBN 0-87893-189-9.

- ↑ Dawkins, Richard; Coyne, Jerry (1 September 2005). «One side can be wrong». guardian.co.uk. Retrieved 29 January 2011.

- ↑ Muller, H.J. (1959). «One hundred years without Darwin are enough». School Science and Mathematics. 59: 304–305. doi:10.1111/j.1949-8594.1959.tb08235.x. Archived from the original on 2016-03-03. Retrieved 2009-11-18.

Reprinted in:

Zetterberg, Peter, ed. (1983). Evolution versus creationism: the public education controversy. Phoenix AZ: ORYX Press. ISBN 0897740610. - ↑ Theobald, Douglas L. (2010). «A formal test of the theory of universal common ancestry». Nature. 465 (7295): 219–222. Bibcode:2010Natur.465..219T. doi:10.1038/nature09014. PMID 20463738. S2CID 4422345.

- ↑ Steel, Mike; Penny, David (2010). «Origins of life: common ancestry put to the test». Nature. 465 (7295): 168–9. Bibcode:2010Natur.465..168S. doi:10.1038/465168a. PMID 20463725. S2CID 205055573.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 Darwin, Charles; Costa, James T. 2009. The annotated Origin: a facsimile of the first edition of On the Origin of Species annotated by James T. Costa. Cambridge, Massachusetts, and London, England: Belknap Press of Harvard University. ISBN 978-0-674-03281-1

- ↑ Dawkins, Richard 2009. The greatest show on Earth: the evidence for evolution. Transworld, Ealing. ISBN 978-0-593-06173-2

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 Jerry Coyne (2009). Why evolution is true. Penguin Group. pp. 85–86. ISBN 978-0-670-02053-9.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Futuyma D.J. 1983. Science on trial: the case for evolution. Pantheon Books, New York. ISBN 0-394-52371-7; 2nd ed 1995 Sinauer Associates, Sunderland, Massachusetts. ISBN 0-87893-184-8

- ↑ Rudwick M.J.S. 1972. The meaning of fossils: episodes in the history of palaeontology. Chicago University Press.

- ↑ Whewell, William 1837. History of the inductive sciences, from the earliest to the present time. vol III, Parker, London. Book XVII The palaeotiological sciences. Chapter 1 Descriptive geology, section 2. Early collections and descriptions of fossils, p405.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Bowler, Peter H. 2003. Evolution: the history of an idea. 3rd ed, University of California Press.

- ↑ Prothero, Donald R. 2007. Evolution: what the fossils say and why it matters. Columbia University Press, New York. ISBN 978-0-231-13962-5

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 17.3 17.4 17.5 Darwin, Charles 1884. The origin of species. 6th ed, Murray, London.

- ↑ Wallace, Alfred Russel 1876. The geographical distribution of animals. 2 vols, Macmillan, London.

- ↑ Wallace, Alfred Russel 1880. Island life. Macmillan, London.

- ↑ Williams, J. et al. 2001. Biodiversity, Australia State of the Environment Report 2001 (Theme Report), CSIRO Publishing on behalf of the Department of the Environment and Heritage, Canberra. ISBN 0-643-06749-3

- ↑ Menkhorst, Peter; Knight, Frank (2001). A field guide to the mammals of Australia. Oxford University Press. p. 14. ISBN 0-19-550870-X.

- ↑ Michael Augee, Brett Gooden, and Anne Musser (2006). Echidna: Extraordinary egg-laying mammal. CSIRO Publishing.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Bats arrived 15 million years ago (mya), and rodents 5–10 mya. Egerton L. (ed) 2005. Encyclopedia of Australian wildlife. Reader’s Digest ISBN 1-876689-34-X

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 Simpson G.G. 1951. Horses: the story of the horse family in the modern world and through sixty million years of history. Oxford, New York. (despite the title, the earliest record of the horse is 52 mya)

- ↑ Singer, Ben 2005. A brief history of the horse in America. Canadian Geographic Magazine. [1] Archived 2012-01-07 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Carson H.L. 1970. Chromosomal tracers of evolution. Science 168, 1414–1418.

- ↑ Carson H.L. 1983. Chromosomal sequences and interisland colonizations in Hawaiian Drosophila. Genetics 103, 465-482.

- ↑ Carson H.L. 1992. Inversions in Hawaiian Drosophila. In: Krimbas C.B. & Powell J.R. (eds) Drosophila inversion polymorphism. CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL. 407-439.

- ↑ Kaneshiro K.Y. Gillespie R.G. and Carson H.L. 1995. Chromosomes and male genitalia of Hawaiian Drosophila: tools for interpreting phylogeny and geography. In Wagner W.L. & Funk E. (eds) Hawaiian biogeography: evolution on a hot spot archipelago. Smithsonian, Washington D.C. 57-71

- ↑ Davis, Paul and Kenrick, Paul. 2004. Fossil plants. Smithsonian, Washington D.C. ISBN 1-58834-156-9

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 Gehring, Walter. 1998. Master control genes in development and evolution: the homeobox story. Yale University Press, New Haven, Connecticut. ISBN 0-300-07409-3

- ↑ Grimaldi D. and Engel M.S. 2005. Evolution of the insects. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-82149-5

- ↑ Tree of Life Web Project Archived 2012-09-11 at the Wayback Machine — explore complete phylogenetic tree interactively.

- ↑ Wiedersheim, Robert 1893. The structure of Man: an index to his past history. Macmillan, London.

- ↑ Peter Gray (2007). Psychology (5th ed.). Worth. p. 66. ISBN 978-0-7167-0617-5.

- ↑ Anthony Stevens (1982). Archetype: a natural history of the self. Routledge & Kegan Paul. p. 87. ISBN 0-7100-0980-1.

- ↑ Futuyma D.J. 2005. Evolution. Sinauer, Sunderland, Massachusetts. Sinauer. ISBN 0-87893-187-2

- ↑ Baleen whales, such as the blue whale, use a comb-like structure made of keratin to filter the plankton from the water.

- ↑ Fudge D.S., Szewciw L.J. and A.N. Schwalb. 2009. Morphology and development of blue whale baleen: an annotated translation of Tycho Tullberg’s classic 1883 paper. Aquatic Mammals 35(2):226-252.

- ↑ Charles Darwin 1851 and 1854. A Monograph of the Sub-class Cirripedia, with figures of all the species.

- ↑ van Wyhe, John (ed) 2002. The complete work of Charles Darwin online. [2]

- ↑ Vavilov N. 1951. The origin, variation, immunity and breeding of cultivated plants (translated by K. Starr Chester). Chronica Botanica 13:1–366.

- ↑ Vavilov N. 1992. Origin and geography of cultivated plants (translated by Doris Love). Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. ISBN 0-521-40427-4

- ↑ 44.0 44.1 44.2 44.3 Gillespie J.H. 2004. Population genetics: a concise guide 2nd ed, Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore. ISBN 0-8018-8009-2

- ↑ Hiendleder, S; Kaupe, B; Wassmuth, R; Janke, A. (2002). «Molecular analysis of wild and domestic sheep questions current nomenclature and provides evidence for domestication from two different subspecies». Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 269 (1494): 893–904. doi:10.1098/rspb.2002.1975. PMC 1690972. PMID 12028771.

- ↑ Nowak R. 1999 Walker’s Mammals of the World 6th ed. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

- ↑ Rice W.R. and G.W. Salt (1988). «Speciation via disruptive selection on habitat preference: experimental evidence». The American Naturalist. 131 (6): 911–917. doi:10.1086/284831. S2CID 84876223.

- ↑ W.R. Rice and E.E. Hostert (1993). «Laboratory experiments on speciation: what have we learned in forty years?». Evolution. 47 (6): 1637–1653. doi:10.2307/2410209. JSTOR 2410209.

- ↑ Dodd, D.M.B. (1989). «Reproductive isolation as a consequence of adaptive divergence in Drosophila pseudoobscura«. Evolution. 43 (6): 1308–1311. doi:10.2307/2409365. JSTOR 2409365. PMID 28564510.

- ↑ Kirkpatrick M. and V. Ravigné 2002. Speciation by natural and sexual selection: models and experiments The American Naturalist 159:S22–S35 DOI

- ↑ Stephen Jay Gould, Evolution as fact and theory Archived 2019-03-17 at the Wayback Machine from Hen’s teeth and horse’s toes, New York: Norton 1994, pp253-262.

- ↑ Quammen, David, Was Darwin wrong? Archived 2007-11-28 at the Wayback Machine, National Geographic, November 2004

- ↑ Plant pests: The biggest threats to food security? BBC News Science & Environment [3]

- ↑ Alyokhin A. et al. 2008. Colorado potato beetle resistance to insecticides. American Journal of Potato Research 85: 395–413.

- ↑ see, for example, the discussion in Bowler, Peter H. 2003. Evolution: the history of an idea. 3rd ed, California. p86–95, especially «Whatever the true nature of Lamarck’s theory, it was his mechanism of adaptation that caught the attention of later naturalists». p90

- ↑ Stern, Curt and Underwood, Eva R. (eds) 1966. The origin of genetics: a Mendel source book. Freeman, San Francisco.

- ↑ Carlson, E.A. 1966. The gene: a critical history. Saunders, N.Y.

- ↑ Maynard Smith, John 1993. The theory of evolution. Cambridge University Press. p133

- ↑ 59.0 59.1 59.2 59.3 59.4 Futuyma D.J. 1986. Evolutionary biology. Sinauer Associates, Sunderland, Massachusetts. 2nd ed, Sinauer. ISBN 0-87893-188-0

- ↑ A paraphrase of Darwin C.D. 1859. On the origin of species. Chapters 1 and 2, especially p45.

- ↑ Ridley, Mark 1996. Evolution. 2nd ed, Wiley-Blackwell ISBN 0-632-04292-3

- ↑ Futuyma D.J. 2005. Evolution. Sinauer, Sunderland, Massachusetts. ISBN 0-87893-187-2

- ↑ Evolution 101: Natural selection from the Understanding evolution webpages made by the University of California at Berkeley

- ↑ Endler J.A. 1986. Natural selection in the wild. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-00057-3.

- ↑ 65.0 65.1 Ford E.B. 1964, 4th edn 1975. Ecological genetics. Chapman and Hall, London.

- ↑ Ruxton G.D; Sherratt T.N. and Speed M.P. 2004. Avoiding attack: the evolutionary ecology of crypsis, warning signals and mimicry. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-852860-4

- ↑ Wood R.J. 1981. Insecticide resistance: genes and mechanisms. In Bishop J.A. & Cook L.M. (eds) Genetic consequences of man-made change. Academic Press, London. 97–127

- ↑ Coelho M. et al. 2002. Microsatellite variation and evolution of human lactase persistence. Human Genetics 117(4): 329–339.

- ↑ Bersaglieri T. et al. 2004. Genetic signatures of strong recent positive selection at the lactase gene. American Journal of Human Genetics 74(6): 1111–20.

- ↑ Wade N. 2006. Study detects recent instance of human evolution. The New York Times. December 10, 2006.

- ↑ Swaminathan, N. 2006. African adaptation to digesting milk is «strongest signal of selection ever». Scientific American.

- ↑ Aoki K. 2001. Theoretical and empirical aspects of gene–culture coevolution. Theoretical Population Biology 59(4): 253–261.

- ↑ Williams, George C. 1966. Adaptation and natural selection: a critique of some current evolutionary thought. Princeton. «Evolutionary adaptation is a phenomenon of pervasive importance in biology.» p5

- ↑ The Oxford Dictionary of Science defines adaptation as «Any change in the structure or functioning of an organism that makes it better suited to its environment».

- ↑ Mayr, Ernst (1963). Animal species and evolution (1st ed.). Cambridge: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-03750-2.

- ↑ Mayr, Ernst (1982). The growth of biological thought: diversity, evolution, and inheritance (1st ed.). Cambridge, Mass: Belknap Press. pp. 562–566. ISBN 0-674-36445-7.

- ↑ Salzburger W., Mack T., Verheyen E., Meyer A. (2005). «Out of Tanganyika: genesis, explosive speciation, key-innovations and phylogeography of the haplochromine cichlid fishes» (PDF). BMC Evolutionary Biology. 5 (17): 17. doi:10.1186/1471-2148-5-17. PMC 554777. PMID 15723698.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Kornfield, Irv; Smith, Peter (November 2000). «African Cichlid fishes: model systems for evolutionary biology». Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics. 31: 163–196. doi:10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.31.1.163. Archived from the original on 2017-11-07. Retrieved 2011-06-06.

- ↑ Price P.W. 1980. The evolutionary biology of parasites. Princeton.

- ↑ The extinction of many Australian marsupials by foreign species is a famous example.

- ↑ O’Brien S. Wildt D. & Bush M. 1986. The Cheetah in genetic peril. Scientific American 254: 68–76. Skin grafts between non-related cheetahs illustrate this point: there is no rejection of the donor skin.

- ↑ Evolution 101:Sampling error and evolution Archived 2010-03-30 at the Wayback Machine and Effects of genetic drift Archived 2012-03-23 at the Wayback Machine from the Understanding evolution webpages of the University of California at Berkeley

- ↑ Evolution 101: Peripatric speciation Archived 2004-04-23 at the Wayback Machine from the Understanding evolution webpages of the University of California at Berkeley

- ↑ Cook O.F. (1906). «Factors of species-formation». Science. 23 (587): 506–507. Bibcode:1906Sci….23..506C. doi:10.1126/science.23.587.506. PMID 17789700.

- ↑ Cook O.F. (1908). «Evolution without isolation». American Naturalist. 42 (503): 727–731. doi:10.1086/279001. S2CID 84565616.

- ↑ Wagner M. Reisen in der Regentschaft Algier in den Jahren 1836, 1837 & 1838. Voss, Leipzig. p199-200

- ↑ Wagner M. 1873. The Darwinian theory and the law of the migration of organisms. Translated by I.L. Laird, London.

- ↑ Provine, William B. 2004. Genetics and speciation, Genetics 167, 1041-1046.

- ↑ Kingsley D.M. January 2009. From atoms to traits. Scientific American p57

- ↑ Evolution 101: Definition: What is Macroevolution? Archived 2010-02-24 at the Wayback Machine from the Understanding Evolution webpages made by the University of California at Berkeley

- ↑ 91.0 91.1 Huxley, Julian S. 1942. Evolution: the modern synthesis. Reprint 2010, The MIT Press. ISBN 0-262-51366-8.

- ↑ 92.0 92.1 Mayr E. and W.B. Provine eds. 1998. The evolutionary synthesis: perspectives on the unification of biology. Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-27225-0

- ↑ Larson, Edward J. 2004. Evolution: the remarkable history of a scientific theory 221-243

- ↑ Provine, William B. 1986. Sewell Wright and evolutionary biology. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-68474-1

- ↑ Dobzhansky T. 1951. Genetics and the Origin of Species. 3rd ed, Columbia University Press New York.

- ↑ George Gaylord Simpson 1953. The major features of evolution. Columbia University Press, New York.

- ↑ Stebbins G. Ledyard 1940. The significance of polyploidy in plant evolution. The American Naturalist 74:54–66

- ↑ Stebbins, G. Ledyard. 1950. Variation and evolution in plants. Columbia University Press, New York.

- ↑ Armbruster W.S. 2012. In Patiny S. (ed) Evolution of plant-pollinator relationships. Cambridge University Press, p45/67.

- ↑ Discussion in Grimaldi D. & Engel M.S. 2005. Evolution of the insects, p613 et seq..

- ↑ Stebbins, G. Ledyard, Jr. 1974. Flowering plants: evolution above the species level. Harvard.

- ↑ Woese C, Kandler O, Wheelis M (1990). «Towards a natural system of organisms: proposal for the domains Archaea, Bacteria, and Eucarya». Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 87 (12): 4576–9. Bibcode:1990PNAS…87.4576W. doi:10.1073/pnas.87.12.4576. PMC 54159. PMID 2112744.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Woese C.R. 2000. Interpreting the universal phylogenetic tree. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA, 97(15):8392–6.

- ↑ Rensch B. 1959. Evolution above the species level. Columbia University Press.

- ↑ Hoffman, Antoni 1989. Arguments on evolution: a paleontologist’s perspective. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-504443-6

- ↑ Stanley S.M. 1979. Evolution: patterns and processes. Freeman, San Francisco. p3, table 7.1, p183. ISBN 0-7167-1092-7

- ↑ Wynne-Edwards V. 1962. Animal dispersion in relation to social behavior. Oliver & Boyd, London.

- ↑ Wynne-Edwards V. 1986. Evolution through group selection. Blackwell, Oxford. ISBN 0-632-01541-1.

- ↑ Williams, George C. 1972. Adaptation and natural selection: a critique of some current evolutionary thought. Princeton University Press.ISBN 0-691-02357-3

- ↑ Williams G.C. 1986. Evolution through group selection. Blackwell. ISBN 0-632-01541-1

- ↑ Maynard Smith, John 1964. Group selection and kin selection Nature 201:1145–1147

- ↑ Maynard Smith, John 1998. Evolutionary genetics, 2nd ed. Oxford.

- ↑ Koeslag J.H. 1997. Sex, the prisoner’s dilemma game, and the evolutionary inevitability of cooperation. J. Theor. Biol. 189, 53–61

- ↑ Koeslag J.H. 2003. Evolution of cooperation: cooperation defeats defection in the cornfield model. J. Theor. Biol. 224, 399–410

- ↑ Hamilton W. 1963. «The evolution of altruistic behavior.» American Naturalist 97:354-356

- ↑ Dawkins R. 1976. The selfish gene. Oxford.

- ↑ Dawkins R. 1982. The extended phenotype. Freeman, Oxford.

- ↑ Mayr, Ernst 1997. The objects of selection. PNAS 94 2091-2094 The objects of selection Archived 2007-03-11 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Hamilton W.D. 1996. Narrow roads of geneland: the collected papers of W.D. Hamilton, vol 1. Freeman, Oxford.

- ↑ Maynard Smith J. 1978. The evolution of sex. Cambridge.

- ↑ 121.0 121.1 Agrawal A.F. 2009. Why reproduction often takes two. Nature 462 p294

- ↑ Morran L.T. Parmenter M.D. & Phillips P.C. 2009. Mutation load and rapid adaptation favour outcrossing over self-fertilisation. Nature 462 p350

- ↑ Normal sexual reproduction with unrelated members of the population.

- ↑ Self-fertilisation (which is possible in some animals and plants) is an extreme form of inbreeding which leads to loss of genetic variability.

- ↑ Mutagen = chemical which causes mutations.

- ↑ «Non-sexual», because obligatory selfing is effectively asexual in its genetic effect.

- ↑ Doebley JF, Gaut BS, Smith BD (2006). «The molecular genetics of crop domestication». Cell. 127 (7): 1309–21. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2006.12.006. PMID 17190597. S2CID 278993.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Gee H; Howlett R. & Campbell P. 2009. 15 evolutionary gems. Nature

- ↑ Browne, Janet (2003). Charles Darwin: The power of place. London: Pimlico. pp. 376–379. ISBN 0-7126-6837-3.

- ↑ Stevenson, Leslie and Haberman, David L. 2009. Ten theories of human nature. 5th ed, Oxford University Press. Chapter 10: Darwinian theories of human nature. ISBN 978-0-19-536825-3

- ↑ For an overview of the controversies see: Dennett, D (1995). Darwin’s dangerous idea: Evolution and the meanings of life. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-0684824710.

- ↑ For the reception of evolution in the 19th and early 20th centuries, see: Johnston, Ian C. «History of science: origins of evolutionary theory». And still we evolve. Liberal Studies Department, Malaspina University College. Archived from the original on 2007-08-23. Retrieved 2007-05-24.

- ↑ Zuckerkandl E (2006). «Intelligent design and biological complexity». Gene. 385: 2–18. doi:10.1016/j.gene.2006.03.025. PMID 17011142.

- ↑ Ross M.R. (2005). «Who believes what? Clearing up confusion over intelligent design and young-Earth creationism» (PDF). Journal of Geoscience Education. 53 (3): 319–323. Bibcode:2005JGeEd..53..319R. doi:10.5408/1089-9995-53.3.319. S2CID 14208021. Retrieved 2008-04-28.