In linguistics, discourse refers to a unit of language longer than a single sentence. The word discourse is derived from the latin prefix dis- meaning «away» and the root word currere meaning «to run». Discourse, therefore, translates to «run away» and refers to the way that conversations flow. To study discourse is to analyze the use of spoken or written language in a social context.

Discourse studies look at the form and function of language in conversation beyond its small grammatical pieces such as phonemes and morphemes. This field of study, which Dutch linguist Teun van Dijk is largely responsible for developing, is interested in how larger units of language—including lexemes, syntax, and context—contribute meaning to conversations.

Definitions and Examples of Discourse

«Discourse in context may consist of only one or two words as in stop or no smoking. Alternatively, a piece of discourse can be hundreds of thousands of words in length, as some novels are. A typical piece of discourse is somewhere between these two extremes,» (Hinkel and Fotos 2001).

«Discourse is the way in which language is used socially to convey broad historical meanings. It is language identified by the social conditions of its use, by who is using it and under what conditions. Language can never be ‘neutral’ because it bridges our personal and social worlds,» (Henry and Tator 2002).

Contexts and Topics of Discourse

The study of discourse is entirely context-dependent because conversation involves situational knowledge beyond just the words spoken. Often times, meaning cannot be extrapolated from an exchange merely from its verbal utterances because there are many semantic factors involved in authentic communication.

«The study of discourse…can involve matters like context, background information or knowledge shared between a speaker and hearer,» (Bloor and Bloor 2013).

Subcategories of Discourse

«Discourse can…be used to refer to particular contexts of language use, and in this sense, it becomes similar to concepts like genre or text type. For example, we can conceptualize political discourse (the sort of language used in political contexts) or media discourse (language used in the media).

In addition, some writers have conceived of discourse as related to particular topics, such as an environmental discourse or colonial discourse…Such labels sometimes suggest a particular attitude towards a topic (e.g. people engaging in environmental discourse would generally be expected to be concerned with protecting the environment rather than wasting resources). Related to this, Foucault…defines discourse more ideologically as ‘practices which systematically form the objects of which they speak’,» (Baker and Ellece 2013).

Discourse in Social Sciences

«Within social science…discourse is mainly used to describe verbal reports of individuals. In particular, discourse is analyzed by those who are interested in language and talk and what people are doing with their speech. This approach [studies] the language used to describe aspects of the world and has tended to be taken by those using a sociological perspective,» (Ogden 2002).

Common Ground

Discourse is a joint activity requiring active participation from two or more people, and as such is dependent on the lives and knowledge of two or more people as well as the situation of the communication itself. Herbert Clark applied the concept of common ground to his discourse studies as a way of accounting for the various agreements that take place in successful communication.

«Discourse is more than a message between sender and receiver. In fact, sender and receiver are metaphors that obfuscate what is really going on in communication. Specific illocutions have to be linked to the message depending on the situation in which discourse takes place…Clark compares language in use with a business transaction, paddling together in a canoe, playing cards or performing music in an orchestra.

A central notion in Clark’s study is common ground. The joint activity is undertaken to accumulate the common ground of the participants. With common ground is meant the sum of the joint and mutual knowledge, beliefs and suppositions of the participants,» (Renkema 2004).

Sources

- Baker, Paul, and Sibonile Ellece. Key Terms in Discourse Analysis. 1st ed., Bloomsbury Academic, 2013.

- Bloor, Meriel, and Thomas Bloor. Practice of Critical Discourse Analysis: An Introduction. Routledge, 2013.

- Henry, Frances, and Carol Tator. Discourses of Domination: Racial Bias in the Canadian English-Language Press. University of Toronto, 2002.

- Hinkel, Eli, and Sandra Fotos, editors. New Perspectives on Grammar Teaching in Second Language Classrooms. Lawrence Erlbaum, 2001.

- Ogden, Jane. Health and the Construction of the Individual. Routledge, 2002.

- Renkema, Jan. Introduction to Discourse Studies. John Benjamins, 2004.

- Van Dijk, Teun Adrianus. Handbook of Discourse Analysis. Academic, 1985.

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Discourse is a generalization of the notion of a conversation to any form of communication.[1] Discourse is a major topic in social theory, with work spanning fields such as sociology, anthropology, continental philosophy, and discourse analysis. Following pioneering work by Michel Foucault, these fields view discourse as a system of thought, knowledge, or communication that constructs our experience of the world. Since control of discourse amounts to control of how the world is perceived, social theory often studies discourse as a window into power. Within theoretical linguistics, discourse is understood more narrowly as linguistic information exchange and was one of the major motivations for the framework of dynamic semantics, in which expressions’ denotations are equated with their ability to update a discourse context.

[edit]

In the humanities and social sciences, discourse describes a formal way of thinking that can be expressed through language. Discourse is a social boundary that defines what statements can be said about a topic. Many definitions of discourse are largely derived from the work of French philosopher Michel Foucault. In sociology, discourse is defined as «any practice (found in a wide range of forms) by which individuals imbue reality with meaning».[2]

Political science sees discourse as closely linked to politics[3][4] and policy making.[5] Likewise, different theories among various disciplines understand discourse as linked to power and state, insofar as the control of discourses is understood as a hold on reality itself (e.g. if a state controls the media, they control the «truth»). In essence, discourse is inescapable, since any use of language will have an effect on individual perspectives. In other words, the chosen discourse provides the vocabulary, expressions, or style needed to communicate. For example, two notably distinct discourses can be used about various guerrilla movements, describing them either as «freedom fighters» or «terrorists».

In psychology, discourses are embedded in different rhetorical genres and meta-genres that constrain and enable them—language talking about language. This is exemplified in the APA’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, which tells of the terms that have to be used in speaking about mental health, thereby mediating meanings and dictating practices of professionals in psychology and psychiatry.[6]

Modernism[edit]

Modernist theorists were focused on achieving progress and believed in the existence of natural and social laws which could be used universally to develop knowledge and thus a better understanding of society.[7] Such theorists would be preoccupied with obtaining the «truth» and «reality», seeking to develop theories which contained certainty and predictability.[8] Modernist theorists therefore understood discourse to be functional.[9] Discourse and language transformations are ascribed to progress or the need to develop new or more «accurate» words to describe new discoveries, understandings, or areas of interest.[9] In modernist theory, language and discourse are dissociated from power and ideology and instead conceptualized as «natural» products of common sense usage or progress.[9] Modernism further gave rise to the liberal discourses of rights, equality, freedom, and justice; however, this rhetoric masked substantive inequality and failed to account for differences, according to Regnier.[10]

Structuralism (Saussure & Lacan)[edit]

Structuralist theorists, such as Ferdinand de Saussure and Jacques Lacan, argue that all human actions and social formations are related to language and can be understood as systems of related elements.[11] This means that the «individual elements of a system only have significance when considered in relation to the structure as a whole, and that structures are to be understood as self-contained, self-regulated, and self-transforming entities».[11]: 17 In other words, it is the structure itself that determines the significance, meaning and function of the individual elements of a system. Structuralism has made an important contribution to our understanding of language and social systems.[12] Saussure’s theory of language highlights the decisive role of meaning and signification in structuring human life more generally.[11]

Poststructuralism (Foucault)[edit]

Following the perceived limitations of the modern era, emerged postmodern theory.[7] Postmodern theorists rejected modernist claims that there was one theoretical approach that explained all aspects of society.[8] Rather, postmodernist theorists were interested in examining the variety of experiences of individuals and groups and emphasized differences over similarities and common experiences.[9]

In contrast to modernist theory, postmodern theory is more fluid, allowing for individual differences as it rejects the notion of social laws. Such theorists shifted away from truth-seeking, and instead sought answers for how truths are produced and sustained. Postmodernists contended that truth and knowledge are plural, contextual, and historically produced through discourses. Postmodern researchers therefore embarked on analyzing discourses such as texts, language, policies, and practices.[9]

Foucault[edit]

In the works of the philosopher Michel Foucault, a discourse is “an entity of sequences, of signs, in that they are enouncements (énoncés).”[13] The enouncement (l’énoncé, “the statement”) is a linguistic construct that allows the writer and the speaker to assign meaning to words and to communicate repeatable semantic relations to, between, and among the statements, objects, or subjects of the discourse.[13] There exist internal relations among the signs (semiotic sequences) that are between and among the statements, objects, or subjects of the discourse. The term discursive formation identifies and describes written and spoken statements with semantic relations that produce discourses. As a researcher, Foucault applied the discursive formation to analyses of large bodies of knowledge, e.g. political economy and natural history.[14]

In The Archaeology of Knowledge (1969), a treatise about the methodology and historiography of systems of thought (“epistemes”) and of knowledge (“discursive formations”), Michel Foucault developed the concepts of discourse. The sociologist Iara Lessa summarizes Foucault’s definition of discourse as «systems of thoughts composed of ideas, attitudes, courses of action, beliefs, and practices that systematically construct the subjects and the worlds of which they speak.»[15] Foucault traces the role of discourse in the legitimation of society’s power to construct contemporary truths, to maintain said truths, and to determine what relations of power exist among the constructed truths; therefore discourse is a communications medium through which power relations produce men and women who can speak.[9]

The inter-relation between power and knowledge renders every human relationship into a power negotiation,[16] because power is always present and so produces and constrains the truth.[9] Power is exercised through rules of exclusion (discourses) that determine what subjects people can discuss; when, where, and how a person may speak; and determines which persons are allowed speak.[13] That knowledge is both the creator of power and the creation of power, Foucault coined the term power-knowledge to show that an object becomes a «node within a network» of meanings. In The Archaeology of Knowledge, Foucault’s example is a book’s function as a node within a network meanings. The book does not exist as an individual object, but exists as part of a structure of knowledge that is «a system of references to other books, other texts, other sentences.» In the critique of power–knowledge, Foucault identified Neo-liberalism as a discourse of political economy which is conceptually related to governmentality, the organized practices (mentalities, rationalities, techniques) with which people are governed.[17][18]

Interdiscourse studies the external semantic relations among discourses, because a discourse exists in relation to other discourses, e.g. books of history; thus do academic researchers debate and determine “What is a discourse?” and “What is not a discourse?” in accordance with the denotations and connotations (meanings) used in their academic disciplines.[14]

Discourse analysis[edit]

In discourse analysis, discourse is a conceptual generalization of conversation within each modality and context of communication. In this sense, the term is studied in corpus linguistics, the study of language expressed in corpora (samples) of «real world» text.

Moreover, because a discourse is a body of text meant to communicate specific data, information, and knowledge, there exist internal relations in the content of a given discourse, as well as external relations among discourses. As such, a discourse does not exist per se (in itself), but is related to other discourses, by way of inter-discursive practices.

In Francois Rastier’s approach to semantics, discourse is understood as meaning the totality of codified language (i.e., vocabulary) used in a given field of intellectual enquiry and of social practice, such as legal discourse, medical discourse, religious discourse, etc.[19] In this sense, along with that of Foucault’s in the previous section, the analysis of a discourse examines and determines the connections among language and structure and agency.

Formal semantics and pragmatics[edit]

In formal semantics and pragmatics, discourse is often viewed as the process of refining the information in a common ground. In some theories of semantics such as discourse representation theory, sentences’ denotations themselves are equated with functions which update a common ground.[20][21][22][23]

See also[edit]

- Common ground

- Conversational scoreboard

- Critical discourse analysis

- Deconstruction

- Difference (philosophy)

- Discipline and Punish

- Discourse community

- Discursive dominance

- Discourse Studies

- Dynamic semantics

- Episteme

- Foucauldian discourse analysis

- Interdiscursivity

- Parrhesia

- Post-structuralism

- Pragmatics

- The Philosophical Discourse of Modernity, a 1985 book by Jürgen Habermas, regarded as an important contribution to Frankfurt School critical theory

- Public speaking

- Rhetoric

References[edit]

- ^ The noun derives from a Latin verb meaning “running to and fro”. For a concise historical account of the term and the concept see Dorschel, Andreas. 2021. «Diskurs.» Pp. 110–114 in Zeitschrift für Ideengeschichte XV/4: Falschmünzer, edited by M. Mulsow, & A.U. Sommer. Munich: C.H. Beck.

- ^ Ruiz, Jorge R. (2009-05-30). «Sociological discourse analysis: Methods and logic». Forum: Qualitative Social Research. 10 (2): Article 26.

- ^ «Politics, Ideology, and Discourse» (PDF). Retrieved 2019-01-27.

- ^ van Dijk, Teun A. «What is Political Discourse Analysis?» (PDF). Retrieved 2020-03-21.

- ^ Feindt, Peter H.; Oels, Angela (2005). «Does discourse matter? Discourse analysis in environmental policy making». Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning. 7 (3): 161–173. doi:10.1080/15239080500339638. S2CID 143314592.

- ^ Schryer, Catherine F., and Philippa Spoel. 2005. «Genre theory, health-care discourse, and professional identity formation.» Journal of Business and Technical Communication 19: 249. Retrieved from SAGE.

- ^ a b Larrain, Jorge. 1994. Ideology and Cultural Identity: Modernity and the Third World Presence. Cambridge: Polity Press. ISBN 9780745613154. Retrieved via Google Books.

- ^ a b Best, Steven; Kellner, Douglas (1997). The Postmodern Turn. New York City: The Guilford Press. ISBN 978-1-57230-221-1.

- ^ a b c d e f g Strega, Susan. 2005. «The View from the Poststructural Margins: Epistemology and Methodology Reconsidered.» Pp. 199–235 in Research as Resistance, edited by L. Brown, & S. Strega. Toronto: Canadian Scholars’ Press.

- ^ Regnier, 2005

- ^ a b c Howarth, D. (2000). Discourse. Philadelphia: Open University Press. ISBN 978-0-335-20070-2.

- ^ Sommers, Aaron. 2002. «Discourse and Difference.» Cosmology and our View of the World, University of New Hampshire. Seminar summary.

- ^ a b c M. Foucault (1969). L’Archéologie du savoir. Paris: Éditions Gallimard.

- ^ a b M. Foucault (1970). The Order of Things. Pantheon Books. ISBN 0-415-26737-4.

- ^ Lessa, Iara (February 2006). «Discursive Struggles within Social Welfare: Restaging Teen Motherhood». The British Journal of Social Work. 36 (2): 283–298. doi:10.1093/bjsw/bch256.

- ^ Foucault, Michel. Power/Knowledge: Selected Interviews and Other Writings, 1972–1977 (1980) New York City: Pantheon Books.

- ^ “Governmentality”, A Dictionary of Geography (2004) Susan Mayhew, Ed., Oxford University Press, p. 0000.

- ^ Foucault, Michel. The Birth of Biopolitics: Lectures at the Collège de France, 1978–1979 (2008) New York: Palgrave MacMillan, pp. 0000.

- ^ Rastier, Francois, ed. (June 2001). «A Little Glossary of Semantics». Texto! Textes & Cultures (Electronic journal) (in French). Translated by Larry Marks. Institut Saussure. ISSN 1773-0120. Retrieved 5 April 2020.

- ^ Green, Mitchell (2020). «Speech Acts». In Zalta, Edward (ed.). Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved 2021-03-05.

- ^ Pagin, Peter (2016). «Assertion». In Zalta, Edward (ed.). Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved 2021-03-05.

- ^ Nowen, Rick; Brasoveanu, Adrian; van Eijck, Jan; Visser, Albert (2016). «Dynamic Semantics». In Zalta, Edward (ed.). The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved 2020-08-11.

- ^ Stalnaker, Robert (1978). «Assertion». In Cole, P (ed.). Syntax and Semantics, Vol. IX: Pragmatics. Academic Press.

Further reading[edit]

- Foucault, Michel (1972) [1969]. Archaeology of Knowledge. New York: Pantheon Books. ISBN 978-0-415-28752-4.

- — (1977). Discipline and Punish. New York: Pantheon Books. ISBN 978-0-394-49942-0.

- — (1980). «Two Lectures,» in Power/Knowledge: Selected Interviews, edited by C. Gordon. New York; Pantheon Books.

- — (2003). Society Must Be Defended. New York: Picador. ISBN 978-0-312-42266-0.

- McHoul, Alec; Grace, Wendy (1993). A Foucault Primer: Discourse, Power, and the Subject. Melbourne: Melbourne University Press. ISBN 978-0-8147-5480-1.

- Motion, J.; Leitch, S. (2007). «A Toolbox for Public Relations: The Oeuvre of Michel Foucault». Public Relations Review. 33 (3): 263–268. doi:10.1016/j.pubrev.2007.05.004. hdl:1959.3/76588.

- R. Mullaly, Robert (1997). Structural Social Work: Ideology, Theory, and Practice (2nd ed.). New York City: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-7710-6673-3.

- Howard, Harry. (2017). «Discourse 2.» Brain and Language, Tulane University. [PowerPoint slides].

- Norton, Bonny (1997). «Language, identity, and the ownership of English». TESOL Quarterly. 31 (3): 409–429. doi:10.2307/3587831. JSTOR 3587831.

- Sunderland, J. (2004). Gendered Discourses. New York City: Palgrave Macmillan.

External links[edit]

Wikiquote has quotations related to Discourse.

- DiscourseNet, an international association for discourse studies.

- Beyond open access: open discourse, the next great equalizer, Retrovirology 2006, 3:55

- Discourse (Lun) in the Chinese tradition

Noun

Hans Selye, a Czech physician and biochemist at the University of Montreal, took these ideas further, introducing the term «stress» (borrowed from metallurgy) to describe the way trauma caused overactivity of the adrenal gland, and with it a disruption of bodily equilibrium. In the most extreme case, Selye argued, stress could wear down the body’s adaptation mechanisms, resulting in death. His narrative fit well into the cultural discourse of the cold-war era, where, Harrington writes, many saw themselves as «broken by modern life.»

—

Such is the exquisite refinement of American political discourse in the early 21st century.

—

Literature records itself, shows how its records might be broken, and how the assumptions of a given discourse or culture might thereby be challenged. Shakespeare is, again, the great example.

—

He likes to engage in lively discourse with his visitors.

She delivered an entertaining discourse on the current state of the film industry.

Verb

The most energetic ingredients in a Ken Burns documentary are the intervals of commentary, the talking heads of historians, sociologists, and critics coming at us in living color and discoursing volubly.

—

Clarke had discoursed knowledgeably on the implications of temperature for apples; it was too cool here for … Winesaps, or Granny Smiths, none of which mature promptly enough to beat autumn’s first freeze.

—

… Bill Clinton was up in the sky-box suites, giving interviews. So The Baltimore Sun’s guy on the job was Carl Cannon and he took notes while Clinton discoursed on the importance of Ripken’s streak, the value of hard work, the lessons communicated to our youth in a nation troubled by blah blah blah.

—

She could discourse for hours on almost any subject.

the guest lecturer discoursed at some length on the long-term results of the war

See More

Recent Examples on the Web

Dialog, discourse, and engagement are essential elements of a university’s function, whether in the classroom, across and among governance units, or between the institution and its external constituents (e.g., alumni, community members, legislators).

—

Political discourse?

—

Others wrote that family love should transcend politics, that public discourse could stop at the threshold.

—

The former is discourse, which is very much within the scope of acceptable behavior toward a public figure; the latter is harassment, which is very much not.

—

At the same time, his government has sought to remove nuance from public discourse, Mr. Wani says.

—

That’s the larger, more important discourse ahead, and Thao will have to steer it while being abundantly transparent on why her strict stance on accountability is in everyone’s best interest, especially Black Oaklanders.

—

All this nepo-baby discourse, all this talk of leg-ups and familial privilege, and in 2010, a 16-year-old, completely unknown Harry Styles skived off school and walked into an X Factor audition.

—

Because there was also, at the same time, a discourse going on, which is still ongoing, about how Trump was actually the summation of all of these fringe traditions in American politics.

—

Those qualities reflected not just in the appearance of, or discourse around, these cultural products, but in the execution of the products themselves.

—

Harassment, even if technically not against the law, is wrong and corrosive to discourse.

—

That means the College Football Playoff’s four-team system that was introduced in 2014 and has become part of Alabama fans’ discourse each November will end after the upcoming 2023 season.

—

But like art made in other arenas, prison art exists in relation to economies, power structures governing resources and access, and discourses that legitimate certain works as art and others as craft, material object, historical artifact, or trash.

—

Backed by a five-piece band, Janelle McDermoth discourses on life, death and the arguable usefulness of art.

—

In a 2016 article, Krauze discoursed on populism: The term has different meanings, or at least overtones, in different regions of the world and in different political traditions.

—

In the audience plump dignitaries in bright orange turbans sat comfortably on white leather armchairs, discoursing on the spectacle.

—

Knights, serfs, monks, men-at-arms, artisans, and shopkeepers traveled these pungent ways, discoursing loudly in decayed Latic and foreign tongues ranging from English to Syrian.

—

See More

These examples are programmatically compiled from various online sources to illustrate current usage of the word ‘discourse.’ Any opinions expressed in the examples do not represent those of Merriam-Webster or its editors. Send us feedback about these examples.

Britannica Dictionary definition of DISCOURSE

formal

1

[noncount]

:

the use of words to exchange thoughts and ideas

-

It’s a word that doesn’t have much use in ordinary discourse. [=conversation]

-

He likes to engage in lively discourse with his visitors.

-

public/political discourse

2

[count]

:

a long talk or piece of writing about a subject

-

She delivered an entertaining discourse on the current state of the film industry.

Britannica Dictionary definition of DISCOURSE

:

to talk about something especially for a long time

-

She could discourse for hours on/about almost any subject.

Discourse refers to the use of language beyond single sentences. Discourse is an important study for the English language because it allows individuals to express their ideas and thoughts effectively, understand and interpret the perspectives and opinions of others, and build relationships through effective communication. Discourse analysis is also critical for language teachers and researchers to better understand language use and development.

What is the definition of discourse?

Discourse is the verbal or written exchange of ideas. Any unit of connected speech or writing that is longer than a sentence and that has a coherent meaning and a clear purpose is referred to as discourse.

An example of discourse is when you discuss something with your friends in person or over a chat platform. Discourse can also be when someone expresses their ideas on a particular subject in a formal and orderly way, either verbally or in writing.

Most of what we know of discourse today is thanks to the French philosopher, writer and literary critic Michel Foucault, who developed and popularised the concept of discourse. You can read about his use of the term in The Archeology of Knowledge and Discourse on Language (1969).

What is the function of discourse?

Discourse has significant importance in human behaviour and the development of human societies. It can refer to any kind of communication.

Spoken discourse is how we interact with each other, as we express and discuss our thoughts and feelings. Think about it — isn’t conversation a huge part of our daily lives? Conversations can enrich us, especially when they are polite and civil.

Civil discourse is a conversation in which all parties are able to equally share their views without being dominated. Individuals engaged in civil discourse aim to enhance understanding and the social good through frank and honest dialogue. Engaging in such conversations helps us live peacefully in society.

What is more, written discourse (which can consist of novels, poems, diaries, plays, film scripts etc.) provides records of decades-long shared information. How many times have you read a book that gave you an insight into what people did in the past? And how many times have you watched a film which made you feel less alone because it showed you that someone out there feels the same way you do?

‘Discourse analysis’ is the study of spoken or written language in context and explains how language defines our world and our social relations.

What is Critical Discourse Analysis?

Critical discourse analysis is an interdisciplinary method in the study of discourse that is used to examine language as a social practice. The method is aimed at the form, structure, content and reception of discourse, in both spoken and written forms. Critical discourse analysis explores social relations, social problems, and the ‘ role of discourse on the production and reproduction of power abuse or domination in communications’.

Teun A. van Dijk offers this definition of CDA in ‘Multidisciplinary Critical Discourse Analysis: A plea for diversity.’ (2001).

CDA explores the relationship between language and power. Because language both shapes and is shaped by society, CDA offers an explanation of why and how discourse works.

The social context in which discourse occurs influences how participants speak or write.

If you write an email to apply for a job, you would most likely use more formal language, as this is socially acceptable in that situation.

At the same time, the way in which people speak ultimately influences the social context.

If you are meeting your new boss and you have prepared for a formal conversation, but all of your other colleagues are chatting with your boss in a more casual manner, you would do the same as everyone else, in this way changing what is expected.

By examining these social influences, critical discourse analysis explores social structures and issues even further. Critical discourse analysis is problem or issue-oriented: it must successfully study relevant social problems in language and communication, such as racism, sexism, and other social inequalities in conversation. The method allows us to look into the sociopolitical context — power structures and the abuse of power in society.

Critical discourse analysis is often used in the study of rhetoric in political discourse, media, education and other forms of speech that deal with the articulation of power.

Linguist Norman Fairclough’s (1989, 1995) model for CDA consists of three processes for analysis, tied to three interrelated dimensions of discourse:

- The object of analysis (including visual or verbal texts).

- The process by which the object was produced and received by people (including writing, speaking, designing and reading, listening, and viewing).

- The socio-historical conditions that inform or influence these processes.

Tip: These three dimensions require different types of analysis, such as text analysis (description), processing analysis (interpretation), and social analysis (explanation). Think about when your teacher asks you to analyse a newspaper and determine its author’s bias. Is the author’s bias related to their social background or their culture?

Simply put, critical discourse analysis studies the underlying ideologies in communication. A multidisciplinary study explores relations of power, dominance, and inequality, and the ways these are reproduced or resisted by social groups via spoken or written communication.

Language is used to establish and reinforce societal power, which individuals or social groups can achieve through discourse (also known as ‘rhetorical modes’).

What are the four types of discourse?

The four types of discourse are description, narration, exposition and argumentation.

| Types of discourse | Purpose for the type of discourse |

| Description | Helps the audience visualise the item or subject by relying on the five senses. |

| Narration | Aims to tell a story through a narrator, who usually gives an account of an event. |

| Exposition | Conveys background information to the audience in a relatively neutral way. |

| Argumentation | Aims to persuade and convince the audience of an idea or a statement. |

Description

Description is the first type of discourse. Description helps the audience visualise the item or subject by relying on the five senses. Its purpose is to depict and explain the topic by the way things look, sound, taste, feel, and smell. Description helps readers visualise characters, settings, and actions with nouns and adjectives. Description also establishes mood and atmosphere (think pathetic fallacy in William Shakespeare’s Macbeth (1606).

Examples of the descriptive mode of discourse include the descriptive parts of essays and novels. Description is also frequently used in advertisements.

Let’s look at this example from the advert for One Bottle by One Movement:

‘Beautiful, functional, versatile and sustainable.

At 17 oz / 500ml it’s the only bottle you’ll ever need, using double-wall stainless steel which will keep your drinks cold for 24 hours or piping hot for 12. It’s tough, light and dishwasher safe.’

The advert uses descriptive language to list the qualities of the bottle. The description can affect us; it may even persuade us to buy the bottle by making us visualise exactly what the bottle looks and feels like.

Narration

Narration is the second type of discourse. The aim of narration is to tell a story. A narrator usually gives an account of an event, which usually has a plot. Examples of the narrative mode of discourse are novels, short stories, and plays.

Consider this example from Shakespeare’s tragedy Romeo and Juliet (1597):

‘Two households, both alike in dignity,

In fair Verona, where we lay our scene,

From ancient grudge break to new mutiny,

Where civil blood makes civil hands unclean.

From forth the fatal loins of these two foes

A pair of star-cross’d lovers take their life;

Whose misadventured piteous overthrows

Do with their death bury their parents’ strife.’¹

Shakespeare uses a narrative to set the scene and tell the audience what will occur during the course of the play. Although this introduction to the play gives the ending away, it doesn’t spoil the experience for the audience. On the contrary, because the narration emphasises emotion, it creates a strong sense of urgency and sparks interest. Hearing or reading this as an audience, we are eager to find out why and how the ‘pair of star-cross’d lovers take their life’.

Exposition

Exposition is the third type of discourse. Exposition is used to convey background information to the audience in a relatively neutral way. In most cases, it doesn’t use emotion and it doesn’t aim to persuade.

Examples of discourse exposure are definitions and comparative analysis.

What is more, exposure serves as an umbrella term for modes such as:

Exemplification (illustration): The speaker or writer uses examples to illustrate their point.

Michael Jackson is one of the most famous artists in the world. His 1982 album ‘Thriller’ is actually the best-selling album of all time — it has sold more than 120 million copies worldwide.

Cause / Effect: The speaker or writer traces reasons (causes) and outcomes (effects).

I forgot to set my alarm this morning and I was late for work.

Comparison / Contrast: The speaker or writer examines the similarities and differences between two or more items.

Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone is shorter than Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows.

Definition: The speaker or writer explains a term, often using examples to emphasise their point.

Rock is a type of popular music originating in the late 1960s and 70s and characterized by a heavy beat and simple melodies. One of the most famous rock songs is ‘Smoke on the Water’ by the English band Deep Purple.

Problem / Solution: The speaker or writer draws attention to a particular issue (or issues) and offers ways in which it can be resolved (solutions).

Climate change is possibly the biggest issue humanity has ever faced. It is a largely man-made problem that can be solved by the creative use of technology.

Argumentation

Argumentation is the fourth type of discourse. The aim of argumentation is to persuade and convince the audience of an idea or a statement. To achieve this, argumentation relies heavily on evidence and logic.

Lectures, essays and public speeches are all examples of the argumentative mode of discourse.

Take a look at this example — an excerpt from Martin Luther King Jr.’s famous speech ‘I Have a Dream’ (1963):

‘I have a dream that one day this nation will rise up and live out the true meaning of its creed: We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal. (…). This will be the day when all of God’s children will be able to sing with new meaning: My country, ’tis of thee, sweet land of liberty, of thee I sing. Land where my fathers died, land of the pilgrims’ pride, from every mountainside, let freedom ring. And if America is to be a great nation, this must become true.‘²

In his speech, Martin Luther King Jr. successfully argued that African Americans should be treated equally to white Americans. He rationalised and validated his claim. By quoting the United States Declaration of Independence (1776), King argued that the country could not live up to the promises of its founders unless all its citizens lived in it freely and possessed the same rights.

What are the three categories of literary discourse?

There are three categories of literary discourse — poetic, expressive, and transactional.

| Types of literary discourse | Purpose of literary discourse | Examples |

| Poetic discourse | Poetic devices are incorporated (such as rhyme, rhythm, and style) to emphasise the speaker’s expression of feelings or description of events and places. |

|

| Expressive discourse | Literary writing that focuses on the non-fictional to generate ideas and reflect the author’s emotions, usually without presenting any facts or arguments. |

|

| Transactional discourse | An instructional approach that encourages action by presenting a clear, non-ambiguous plan to the reader and is usually written in an active voice. |

|

Poetic discourse

Poetic discourse is a type of literary communication in which special intensity is given to a text through distinctive diction (such as rhyme), rhythm, style, and imagination. It incorporates different poetic devices to emphasise the poet’s expression of feelings, thoughts, ideas or description of events and places. Poetic discourse is most common in poetry but it is also frequently used by writers of prose.

Let’s look at this example from the tragedy Macbeth (1606) by William Shakespeare:

‘To-morrow, and to-morrow, and to-morrow,

Creeps in this petty pace from day to day,

To the last syllable of recorded time;

And all our yesterdays have lighted fools

The way to dusty death. Out, out, letter candle!

Life’s but a walking shadow, a poor player

That struts and frets his hour upon the stage

And then is heard no more. It is a tale

Told by an idiot, full of sound and fury

Signifying nothing.’ ³

In this soliloquy, Macbeth mourns the death of his wife, Lady Macbeth, and ponders the futility of an unfulfilled life. The use of literary devices and poetic techniques, such as repetition, metaphor and imagery, evokes strong emotions.

Expressive discourse

Expressive discourse refers to literary writing that is creative but not fictional. This writing aims to generate ideas and to reflect the author’s emotions, usually without presenting any facts or arguments.

Expressive discourse includes diaries, letters, memoirs, and blog posts.

Consider this example from The Diary of Anaïs Nin (1934-1939):

‘I was never one with the world, yet I was to be destroyed with it. I always lived seeing beyond it. I was not in harmony with its explosions and collapse. I had, as an artist, another rhythm, another death, another renewal. That was it. I was not at one with the world, I was seeking to create one by other rules…. The struggle against destruction which I lived out in my intimate relationships had to be transposed and become of use to the whole world.’4

In her diaries, Nin reflects on her feelings of being a woman and an artist in the 20th century. She wrote this passage in preparation for leaving France at the start of World War Two. We can read her sense of the disconnection between her intense inner world and the violence of the outer world. This example is a trademark of expressive discourse, as it delves into personal ideas and explores inner thoughts and feelings.

Transactional discourse

Transactional discourse is an instructional approach that is used to encourage action. It presents a non-ambiguous plan that is clear to the reader and is usually written in an active voice. Transactional discourse is common in advertising, instruction manuals, guidelines, privacy policies, and business correspondence.

This excerpt from the novel The Midnight Library (2020) by Matt Haig is an example of transactional discourse:

‘An instruction manual for a washing machine is an example of transactional discourse:

1. Put washing detergent in the drawer2. Push the power button to switch on the power3. Select the suitable automatic programme4. Select the suitable delay wash programme5. Close the top lid6. Finish washing’ 5

This is a clear plan — a list of instructions. Haig uses transactional discourse as part of his work of fiction in order to add realism to the relative part of the story.

Discourse — key takeaways

- Discourse is another word for any kind of written or spoken communication. It is any unit of connected speech that is longer than a sentence, and that has a coherent meaning and a clear purpose.

- Discourse is crucial to human behaviour and social progress.

- Critical discourse analysis is an interdisciplinary method in the study of discourse that is used to examine language as a social practice.

- There are four types of discourse — Description, Narration, Exposition, and Argumentation.

- There are three categories of literary discourse — Poetic, Expressive, and Transactional.

- Discourse appears in Literature (both poetry and prose), speeches, advertisements, diaries, blog posts, definitions and verbal conversations.

SOURCE:

¹ William Shakespeare, Romeo and Juliet, 1597

² Martin Luther King Jr., ‘I Have a Dream’, 1963

³ William Shakespeare, Macbeth, 1606

4 Anaïs Nin, The Diary of Anaïs Nin, Vol. 2, 1934-1939

5 Matt Haig, The Midnight Library, 2020

The title discourse furnishes a central theme to which those following stand in relation. ❋ Gaius Glenn Atkins (1912)

Critically, the crux of the entire process in the development of these works was for Ravi the concept of Sannidhi which in traditional Indian aesthetic discourse translates as ‘proximity’ or ‘close by’ or ‘in the presence’. ❋ Unknown (2010)

Her book, which first appeared in French in 2008, combines three strands: a study of events; a detailed account of the social, economic, religious, cultural, political and administrative context of 12th-century Syria and Egypt; and an unrelenting investigation of what she calls the «discourse.» ❋ Christopher Tyerman (2011)

All that comes from debasing the discourse is a spoiled public forum. ❋ Unknown (2010)

How it shapes our discourse is a worthy topic for consideration. ❋ SVGL (2009)

By the way, using a script exotic to a discourse is a gratuitous and low form of argument. ❋ Unknown (2005)

I am the bread of life — Henceforth the discourse is all in the first person, «I,» «Me,» which occur in one form or other, as Stier reckons, thirty-five times. he that cometh to me — to obtain what the soul craves, and as the only all-sufficient and ordained source of supply. hunger … thirst — shall have conscious and abiding satisfaction. ❋ Unknown (1871)

Like Foucault, Kittler diagnosed the present through what he called discourse analysis — the excavation of the underlying structure of human practices. ❋ Stuart Jeffries (2011)

Severing political discussion from decision and action, however, focuses the locus of Habermasian politics strictly on discussion and what he calls a discourse theory of democracy. ❋ Unknown (2009)

McD reminds me of cruelly ridiculing your spouse at a cocktail party just for a cheap laugh; tells all around you reams abut your character and integrity; what a putz; and — whose payroll is he on? ours? guess loyality is relative; sell out your country and troops and call it «discourse» or «free speech» or «constructive criticism» so you can sleep at night. libs will surely be our collective death; ❋ Unknown (2006)

If you ask me, one of the most disturbing trends in American public discourse is the incredibly provincialism and solipsism of a lot of our policy debate. ❋ Unknown (2009)

The tone of most Internet discourse is historically libertarian, and Republicans did pretty well online for many years. ❋ Unknown (2009)

This level of discourse is “high school stoner speculation” stupid. ❋ Unknown (2009)

The discourse is how we find out what happened; the way the story gets told. ❋ Rebecca Tushnet (2009)

Still, though, we have ever-increasing access to information already, and the national discourse is decomposing before our eyes. ❋ Tom Toles (2010)

I am confident that I should not be trying to appear ‘English’ and hence, any directness or lack of tentativeness typical of Greek discourse, is certain to have crept into the way I use English. ❋ Unknown (2010)

But academic discourse is such a particular thing. ❋ Unknown (2009)

For me — and I think for a lot of people — the moment that «sanity» left the building in American discourse came in late 2002 and early 2003, when it became clear that Dick Cheney, George W. Bush, Paul Halfwits, and their minions were dead set on invading Iraq. ❋ Will Bunch (2010)

Human rights discourse is an essentially individualistic framework, whereas most cultures of the global South (or third world) are formed on a communitarian value system. ❋ Unknown (2009)

Their discourse was widely varied; they discussed [everything] from [Chaucer] to [ice fishing]. ❋ Danny_Luv17 (2008)

[Eagleton] is invoking an ethical obligation on the part of the intellectual to speak for, but also to, those whose consciousness is [lagging] behind whatever Hegelian discourse of [utopian] progress is being espoused.

I had a discourse with your mom last night. ❋ Bigtrick (2006)

You gotta be [Extremely Online] to [keep up with] the [discourse] ❋ Klaudunski (2021)

[Can’t wait] for the new [discourse] this [saturday] ❋ Commissar_nik (2021)

«No students what is the [discourse] of this [piece] of [text]» . . . . . . . . WTF! ❋ Wadup (2005)

[nerd]: [modern] discourses

[steve]: your fucking gay ❋ Taller Than You Kk Ty (2009)

I pointed out that murder was already illegal and that making it moreso with a special [gun murder] [statute] was a bit silly. [Reasoned discourse] broke out, and my comment vanished from the blog. ❋ GCynic (2012)

Hym «Sooo… The public [discourse] being democratized if bad (because why should a [golden god] have to acknowledge a peasant? He should be doing what everyone else is doing. And everyone else should be doing what I tell them. Then everything would be better for everyone.) but identity being democratized is good? That’s how people end up getting [lobotomized] or thrown in an oven. ..» ❋ Hym Iam (2022)

White lesbians [gatekeeping] [dyke], a word originated by black lesbians by not allowing bisexual people to say it is an example of [slur discourse]. ❋ Ihatepinkmonkeys (2021)

[Anne] runs a discourse account called ‘fairy.course’ on instagram. Anne has never [touched] a single [blade of grass] in her life. ❋ Boobie Fan 69 (2021)

Other forms: discourses; discoursed; discoursing

If you use the word discourse, you are describing a formal and intense discussion or debate.

The noun discourse comes from the Latin discursus to mean «an argument.» But luckily, that kind of argument does not mean people fighting or coming to blows. The argument in discourse refers to an exchange of ideas — sometimes heated — that often follows a kind of order and give-and-take between the participants. It’s the kind of argument and discussion that teachers love, so discourse away!

Definitions of discourse

-

noun

an extended communication (often interactive) dealing with some particular topic

-

noun

extended verbal expression in speech or writing

-

noun

an address of a religious nature (usually delivered during a church service)

Definitions of discourse

-

verb

consider or examine in speech or writing

-

verb

talk at length and formally about a topic

-

verb

carry on a conversation

-

synonyms:

converse

see moresee less-

types:

- show 11 types…

- hide 11 types…

-

argue, contend, debate, fence

have an argument about something

-

interview, question

conduct an interview in television, newspaper, and radio reporting

-

interview

discuss formally with (somebody) for the purpose of an evaluation

-

interview

go for an interview in the hope of being hired

-

chaffer, chat, chatter, chew the fat, chit-chat, chitchat, claver, confab, confabulate, gossip, jaw, natter, shoot the breeze, visit

talk socially without exchanging too much information

-

stickle

dispute or argue stubbornly (especially minor points)

-

spar

fight verbally

-

bicker, brabble, niggle, pettifog, quibble, squabble

argue over petty things

-

altercate, argufy, dispute, quarrel, scrap

have a disagreement over something

-

oppose

be against; express opposition to

-

jawbone, schmoose, schmooze, shmoose, shmooze

talk idly or casually and in a friendly way

-

type of:

-

speak, talk

exchange thoughts; talk with

DISCLAIMER: These example sentences appear in various news sources and books to reflect the usage of the word ‘discourse’.

Views expressed in the examples do not represent the opinion of Vocabulary.com or its editors.

Send us feedback

EDITOR’S CHOICE

Look up discourse for the last time

Close your vocabulary gaps with personalized learning that focuses on teaching the

words you need to know.

Sign up now (it’s free!)

Whether you’re a teacher or a learner, Vocabulary.com can put you or your class on the path to systematic vocabulary improvement.

Get started

Discourse:

Pragmatics and Interactional analysis in discourse

DEFINITION

OF DISCOURSE. The difference between text and discourse

Originally

the word ‘discourse’ comes from Latin ‘discursus‘

which denoted ‘conversation, speech’. Discourse is a term used in

LINGUISTICS to refer to a continuous stretch of (especially spoken)

LANGUAGE larger than a SENTENCE — but, within this broad notion,

several different applications may be found. At its most general, a

discourse is a behavioural UNIT which has a pre-theoretical status in

linguistics: it is a set of UTTERANCES which constitute any

recognisable SPEECH event, e.g. a conversation, a joke, a sermon, an

interview… [Crystal, Dictionary

of linguistics and phonetics,

3rd edn 1991]

In

the broad sense discourse ‘includes’ TEXT (q.v.),

but the two terms are not always easily distinguished, and are often

used synonymously.

Some

linguists would restrict discourse to spoken communication, and

reserve text for written:

Text

1.

result

of the process

of

speech production

in

graphic form

2.

indirect (processed) speech

3.

no personal contacts between agents

4.

perception of speech

in

different space

and

time

5.

one agent

Discourse

1.

The process of

speech

production

in

the form of a sound

2.

Spontaneous speech

in

a particular situation

with

the

help of verbal

and nonverbal means

3.

Personal contacts between agents

4.

generation and

perception

of speech

in

a

unity

of space

and

time

5.

two authors constantly change their roles ‘speaker – hearer’

(bilateral discourse).

There

are a number of approaches to discourse analysis and pragmatics is

one of them.

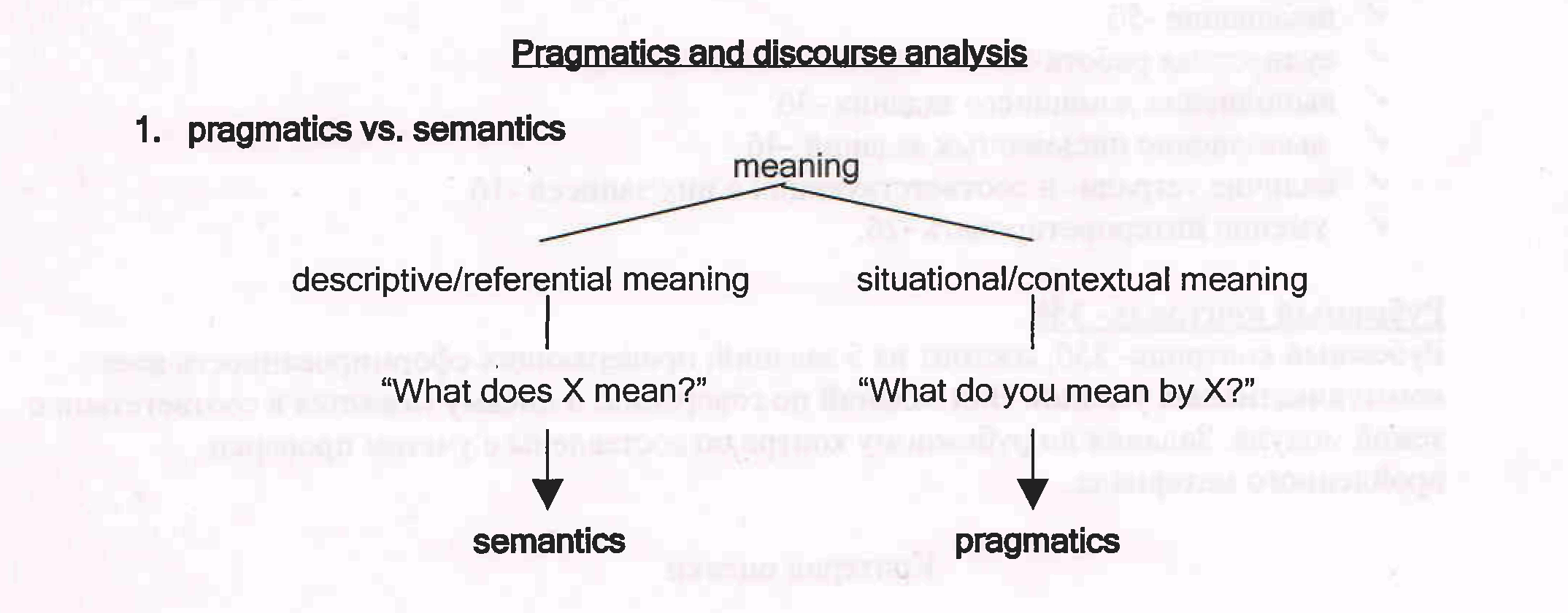

Definitions

of pragmatics:

The

underlying concepts behind pragmatics are meaning, context and

communication. Early researchers considered pragmatics as having

originated from semiosis, a process that involves the use of signs;

hence signs are central to pragmatics users. Pragmatics is a

broad approach to discourse that deals with the widely vast concepts

of meaning, context and communication. Due to the wide scope of

pragmatics, experts have failed to reach an agreement on the best

definition of this approach. In language, pragmatics and discourse

are closely connected. Discourse is the method, either written or

verbal, by which an idea is communicated in an orderly,

understandable fashion. Used as a verb, discourse refers to the

exchange of ideas or information through conversation. Comparatively,

pragmatics involve the use of language to meet specific needs or for

a predetermined purpose. As such, pragmatics and discourse are

related in that pragmatics are the means by which the purpose of

discourse is achieved.

Both

pragmatics and discourse involve concepts far deeper than mere word

definitions and sentence structure. Unlike grammar, which involves

the rules governing proper language structure, pragmatics and

discourse focus on the meaningfulness of spoken or written language.

Whether storytelling, explaining, instructing, or requesting, a

speaker or writer has an intended purpose for communicating. How a

speaker or writer constructs sentences to meet his intended

purpose

involves both pragmatics and discourse.

It

is only with the aid of considerations of a pragmatic nature that we

can go beyond the question «What does this utterance mean?»

and ask «Why was this utterance produced?».and explain how

utterances are interpreted and how successful interpretation of

utterances is managed. F.E.

1

Ms: (You should hurry up a little in persuading the PSOE, because

we’re all in a

hurry

to do all that)

Mr:

(Do you read the papers ?)

To

know why Mr (Maragall) asks the question, we need to bear in mind

quite a number of considerations of a pragmatic nature, for example,

the degree of relevance of the question: in fact considerable, given

that this is a political debate.

While

discourse analysis can only explain that this is a reply to the

observation made by Ms (Mas) or explain what type of sentences make

up each of the utterances, pragmatics will explain what kind of reply

it is, based on one or more implicatures. For example, «if you

read the newspapers you will know that I have done so many times»,

or «as I am sure that you read the newspapers, I think you know

perfectly well that I have done so, therefore your observation is

unnecessary». Taking a pragmatic approach, the linguist can

successfully

uncover

the intention that Mr has in selecting «Do you read the

papers?», and why he selected this utterance rather than another

one.

Pragmatics’

object of study is «language use and language users»

(Haberland & Mey 2002, 1673).

Argumentative

discourse. The concept of argument has a long history in

communication. An argument is a concluding statement that claims

legitimacy on the basis of reason. But argumentative discourse is a

form of interaction in which the individuals maintain incompatible

positions. More specifically, argumentative discourse directs

attention to the arguments of naïve social actors engaged in

intersubjective social interaction rather than the nature and

structure of abstract arguments ( Willard 1989 ). The traditional

notion of argument has the logical syllogism as its elemental

structure. Thus, the concluding statement (A = C) is logically

necessitated in: A = B, B = C, therefore A = C. A politician who

states that “Democrats are liberals; my opponent is a democrat;

therefore, my opponent is a liberal” is arguing from such

syllogistic logic. Argument in this case is abstract and separate

from the perspective of social actors.

Institutional

discourse. Over the past thirty years or so, scholars of language and

social life have investigated discourse within a variety of

institutional contexts, most notably within schools, courtrooms,

corporations, clinics and hospitals. In Institutional Discourse, you

will have multiple opportunities to build on your knowledge and

practice of discourse analysis by exploring some of the intriguing

regions in which institutions and discourse intersect.

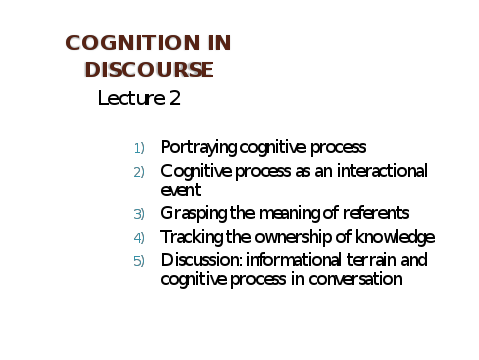

Lecture

2. Cognition in discourse (1 hour)

1)

Portraying cognitive process

2)

Cognitive process as an interactional event

3)

Grasping the meaning of referents

—

Tracking the ownership of knowledge

4)

Discussion: informational terrain and cognitive process in

conversation

Cognition

is the word we use to refer to mental activities such as seeing,

attending, remembering and solving problems. The study of cognition

is the study of the cognitive

processes

that receive, transmit and operate upon information. These processes

operate at every waking moment and they are also part of our

personality, our intelligence and the way we interact socially.

Comprehending them is, to a large extent, understanding what it means

to be human. Their biological site is in the brain and, in psychiatry

and neuroscience they are sometimes considered as mind-related.

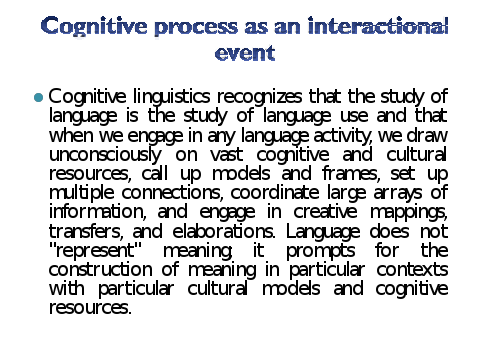

Cognitive

linguistics has emerged in the last twenty-five years as a powerful

approach to the study of language, conceptual systems, human

cognition, and general meaning construction.

It

addresses within language the structuring of basic conceptual

categories such as space and time, scenes and events, entities and

processes, motion and location, force and causation. It addresses the

structuring of ideational and affective categories attributed to

cognitive agents, such as attention and perspective, volition and

intention.

Cognitive

linguistics recognizes that the study of language is the study of

language use and that when we engage in any language activity, we

draw unconsciously on vast cognitive and cultural resources, call up

models and frames, set up multiple connections, coordinate large

arrays of information, and engage in creative mappings, transfers,

and elaborations. Language does not «represent» meaning; it

prompts for the construction of meaning in particular contexts with

particular cultural models and cognitive resources.

Cognitive

linguistics goes beyond the visible structure of language and

investigates the considerably more complex backstage operations of

cognition that create grammar, conceptualization, discourse, and

thought itself. The theoretical insights of cognitive linguistics are

based on extensive empirical observation in multiple contexts, and on

experimental work in psychology and neuroscience.

The

alliance between Cognitive Linguistics and the study of discourse has

become stronger in the recent past. This is a natural development. On

the one hand, Cognitive Linguistics focuses on language as an

instrument for organizing, processing, and conveying information; on

the other, language users communicate through discourse rather than

through isolated sentences.

a.

Cognitive Linguistics is a source of inspiration for the

modeling of discourse structure. Major contributions such as those by

Fauconnier (Mental Spaces), Langacker (Subjectivity), and Sweetser

(Domains of Use) offer the terminology and theoretical framework to

consider linguistic phenomena as structure-building devices.

b.

Cognitive Linguistics provides theoretical insights that can

be—and

partly have been— extended to the discourse level. An example is

the classical cognitive linguistic work on categorization. Human

beings categorize the world around them. As Lakoff (1987) and Lakoff

and Johnson (1999) have shown, the linguistic categories apparent in

people’s everyday language use provide us with many interesting

insights in the working of the mind.

Over the last decade, the categorization of coherence relations and

the linguistic devices expressing them have played a major role in

text-linguistic and cognitive linguistic approaches to discourse. For

instance, the way in which speakers categorize related events by

expressing them with one connective (because)

rather

than another (since)

can

be treated as an act of categorization that reveals language users’

ways of thinking.

c.

Cognitive Linguistics is the study of language in use; it seeks

to develop so-called usage-based models (Barlow and Kemmer 2000) and

in doing so increasingly relies on corpora of naturally occurring

discourse that make it possible to adduce cognitively plausible

theories to empirical testing.

d.

Cognitive Linguistics typically appreciates the methodological

strategy of converging evidence. In principle, linguistic analyses

are to be corroborated by evidence from areas other than linguistics,

such as psychological (Gibbs 1996) and neurological processing

studies.

We

have discourse analysis, and its many branches (stylistics, rhetoric,

narrative or argumentation analysis, as well as syntactic, semantic

or pragmatic analysis, and of course conversation analysis), but

«cognitive analysis» is not a well-known, standard way of

looking at text or talk.

We

have a cognitive psychology of discourse processing (production,

comprehension), and we have a social psychology of discourse (the

Loughborough school) called «discursive psychology», but

the latter rejects any mental approach and in fact advocates a more

ethnomethodological approach to discourse within social psychology.

A

psychological or cognitive study of discourse is rather different

from a more formal, grammatical or (say) stylistic, narrative or

argumentative analysis. It does not deal with abstract categories and

rules purported to describe ‘structures’ of discourse, but with the

actual mental representations and processes of language users. In

that respect, psychology intends to provide a more ’empirically’

based understanding of discourse.

in

a cognitive analysis, interpretation is not static, nor an abstract

procedure, as in linguistic semantics, but a dynamic, ongoing process

of (at first tentatively) assigning meaning and functions to units of

discourse.

In

order to account for such processes of production and understanding,

psychology makes use of a large number of more or less technical

notions describing various aspects of the ‘mind’:

Short

Term Memory (STM) vs. Long Term Memory (LTM)

Episodic

Memory vs. Semantic Memory

Situation

or Even Models

Knowledge

(scripts, etc.)

A

cognitive analysis as intended does not at

all

exclude a further social analysis. Indeed, many aspects of cognitive

representations and processing are themselves social — such as the

socially shared knowledge and other beliefs, as well as the jointly

constructed social aspects of the context. Indeed, discourse

processing and understanding is studied at all levels as part of a

communicative event, as a form of social interaction, for which in

fact it provides a further cognitive basis: also action and

interaction derives its meanings, functions and coordination from

cognitive representations that ongoingly monitor it.

«Cognitive

analysis» of discourse, however, is NOT the same as a

psychological study of discourse processing.

Psychology

focuses on the structures and processes of mental representations,

and does so, for instance, with experiments, or using other forms of

evidence of what actually goed on in the mind. So, cognitive analysis

is not going to measure reading or reaction times, or any other

method psychologists use to test their hypotheses.

Cognitive

analysis is focused on discourse and its structures, but derives its

terms from the theory of discourse processing.

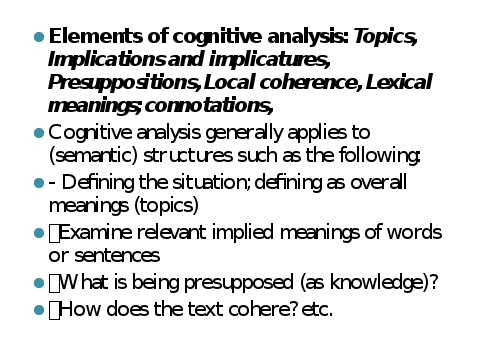

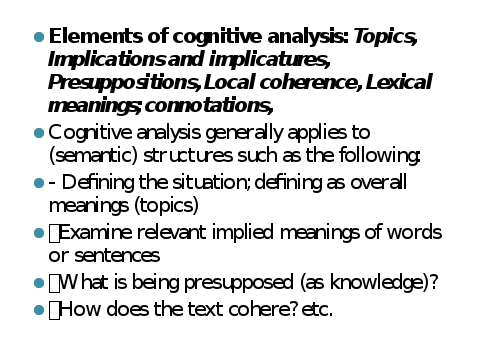

Elements

of cognitive analysis: Topics,

Implications and implicatures, Presuppositions, Local coherence,

Lexical meanings; connotations, We

have only given a short list of examples for cognitive analysis.

However, we see that a cognitive analysis generally applies to

(semantic) structures such as the following:

—

Defining the situation; defining as overall meanings (topics)

Examine

relevant implied meanings of words or sentences

What

is being presupposed (as knowledge)?

How

does the text cohere? etc.

Most

of these semantic structures, as well as many others, can only be

accounted for in terms of personal or socially shared knowledge, and

require listing relevant knowledge or other beliefs.

Lecture

3

An

overview of socio-cultural theory in discourse

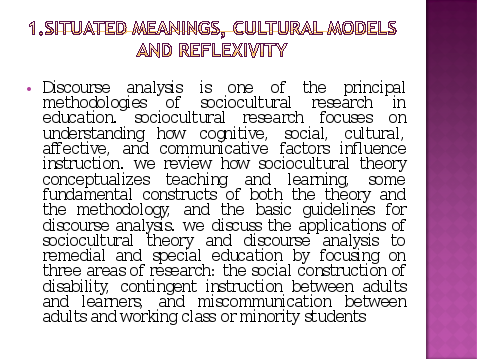

Discourse

analysis is one of the principal methodologies of sociocultural

research in education. sociocultural research focuses on

understanding how cognitive, social, cultural, affective, and

communicative factors influence instruction. we review how

sociocultural theory conceptualizes teaching and learning, some

fundamental constructs of both the theory and the methodology, and

the basic guidelines for discourse analysis. we discuss the

applications of sociocultural theory and discourse analysis to

remedial and special education by focusing on three areas of

research: the social construction of disability, contingent

instruction between adults and learners, and miscommunication between

adults and working class or minority students.

An

emerging body of work in social, political and educational fields is

interested in integrating ethnographic and discourse analytical

approaches. This field includes a wide range of studies,

2.1

Ethnographic perspectives

Ethnography

is concerned with understanding and describing meaning in social

life. Ideally, it involves sustained involvement in a research site

through fieldwork, and the recording of social activity in as much of

its complexity and messiness as possible. As such, ethnography is at

once a research methodology, a set of fieldwork techniques, most

prominently participant observation, and a research product, a

reflexive account of social life that prioritizes participants’

perspectives. As a theoretical and methodological perspective on

situated practices, ethnography is particularly useful for examining

discourse production.

We

begin the discussion of discourse and language by introducing two

types of meaning that attach to words and phrases in actual use:

situated meanings and cultural models. After a brief discussion of

these two notions, we turn to a discussion of an important and

related property of language-in-use, a property ethnomethodologists

call refiexivity.

Through

these constructs, we examine language as social action with a

focus on what members of a social group are accomplishing

through their discourse, rather than focusing solely on language form

or function.

Situated

Meanings and Cultural Models

A

situated meaning is an image or pattern that we (participants in an

interaction) assemble «on the spot» as we communicate in a

given context, based on our construal of that context and on our past

experiences. For example, consider the following two utterances:

«The coffee spilled, get a mop» and «The coffee

spilled, get a broom.» In the first case, triggered by the word

mop

(a

lexical cue), a hearer (or reader) may assemble the situated meaning

as something like «dark liquid we drink» for «coffee,»

by using his or her experience in similar situations. In the second

case, triggered by the word broom

and

personal experience in such matters, a hearer (or reader) may

assemble a situated meaning as something like «grains that we

make our coffee from» or «beans from which we grind

coffee.»

These

contrasting cases provide a point of departure for the discussion of

situated meaning. However, in a real context, there are many

more signals as to how to go about assembling situated meanings for

words and phrases. Gumperz (1982a) called such cues (or clues)

contextualization

cues. They

include prosodic and nonverbal cues such as pitch, stress,

intonation, pause, juncture, proxemics (distance between

speakers, spatial organization of speakers), eye gaze, and kinesics

(gesture, body movement, and physical activity), in addition to

lexical items, grammatical structures, and visual dimensions of

context. Such cues provide information to participants about the

meaning of words and grammar and how to move back and forth between

language and context (situations).

Words

are also associated with «cultural models.» Cultural models

are «story lines,» families of connected images (like a

mental movie), or (informal) «theories» shared by people

belonging to specific social or cultural groups (Cole, 1996;

D’Andrade & Strauss, 1992; Geertz, 1983; Holland &. Quinn,

1987; Spradley, 1980). Cultural models «explain,11

relative to the standards (norms) of a particular social group, why

words have the range of situated meanings they do for members and

shape members’ ability to construct new ones. They also serve as

resources that members of a group can use to guide their actions and

interpretations in new situations.

Cultural

models are usually not stored in any one person’s head but are

distributed across the different sorts of «expertise»

and viewpoints found in a group (Hutchins, 1995; Shore, 1996), much

like a plot of a group-constructed (oral or written) story in which

different people have different bits of information, expertise,

and interpretations that they use to contribute to the plot being

negotiated. Through this process of joint construction of text, then,

members construct local meanings that they draw on to mutually

develop a «big picture.»

From

this theoretical position, not all of the bits and pieces of cultural

models or principles of practice are consciously in people’s heads,

and different bits and pieces are shared across different people and

groups. Through interactions, members appropriate the bits and

pieces available to them within a social group, and these bits and

pieces often become part of people’s taken-for-granted social

practices. In this way, members construct—and,

at times, reconstruct— cultural models socially significant to

appropriate participation within their social group. This

view of the situated nature of meaning and the constructed nature of

cultural knowledge places particular demands on discourse

analysts. The task of the discourse analyst is to construct

representations of cultural models by studying people’s actions

across time and events. In closely observing the concerted actions

among members, examining how and what members communicate, and

interviewing members (see Briggs, 1986, and Mishler, 1986, for

discussions of the constructed nature of interviews), the

analyst asks questions about the patterns of practice that make

visible what members need to know, produce, and interpret to

participate in socially appropriate ways (Heath, 1982).

One

way to approach the study of cultural models is through the use of an

ethnographic perspective to guide a discourse analysis. While

this approach is not the same as doing ethnography, Green and Bloome

(1983,1997) argue that the cultural perspective guiding ethnography

can be productively used in discourse studies (hence the term

ethnogaphic

perspective). One

way to assess how discourse and ethnographic perspectives are

conceptually related is through the definition of the phenomenon of

study in ethnography by Spindler and Spindler (1987):

Within

any social setting, and any social scene within a setting, whether

great or small, social actors are carrying on a culturally

constructed dialogue. This dialogue is expressed in behavior, words,

symbols, and in the application of cultural knowledge to make

instrumental activities and social situations work

for

one. We learn the dialogue as children, and continue learning it all

of our lives, as our circumstances change. This is the phenomenon we

study as ethnographers—the

dialogue of action and interaction, (p. 2)

In

summarizing the goals and purpose of ethnography in this way, they

place the study of «dialogue» in the center of the work,

whether that dialogue be through discourse or through action.

Discourse analysis, then, when guided by an ethnographic

perspective, forms a basis for identifying what members of a social

group (e.g., a classroom or other educational setting) need to know,

produce, predict, interpret, and evaluate in a given setting or

social group to participate appropriately (Heath, 1982) and,

through that participation, learn (i.e., acquire and construct

the cultural knowledge of the group). Thus, an ethnographic

perspective provides a conceptual approach for analyzing discourse

data (oral or written) from an (insider’s) perspective and for

examining how discourse shapes both what is available to be learned

and what is, in fact, learned.8

Lecture

4

Discourse Interpreting

After

these remarks on what the process of translation is, I intend, from

now on, to focus this discussion on translation as a communication

activity and not as a mere product, involving the negotiation of

meanings between producers and receivers of a text. In this sense,

the discussion on translation activities goes far beyond the

linguistic aspects underlying a text but it regards the social,

cultural and psychological dimensions of the process. Thus, the

translation activity should be studied as a discursive practice,

where different reflexive actions are performed, such as: reading,

interpreting, analysis, making decisions and others, which surpass

the level of words and sentences reaching the level of discourse.

According

to Fairclough (1992), discourse is the relationship between text and

social practice. He conceptualizes discourse in three important

dimensions: text,

discursive practice and

social

practice (Figure

2). Shortly, we could say that the text

is

the discursive event, the central part of the discourse which deals

with the linguistic aspects of the language; the discursive

practice is

related to the text production, distribution and consumption of the

text and involves the analysis of the text as discourse — the

interpretation of ideas which brings about the social function of a

text; and finally, the

social practice establishes

the relationship between discourse and the social structure as a

whole — how the discourse articulated by the text may affect current

society, by changing values, behavior, concepts, etc.

Definition of Discourse

Discourse is any written or spoken communication. Discourse can also be described as the expression of thought through language. While discourse can refer to the smallest act of communication, the analysis can be quite complex. Several scholars in many different disciplines have theorized about the different types and functions of discourse.

The word discourse comes from the Latin word discursus, which means “running to and fro.” The definition of discourse thus comes from this physical act of transferring information “to and fro,” the way a runner might.

Types of Discourse

While every act of communication can count as an example of discourse, some scholars have broken discourse down into four primary types: argument, narration, description, and exposition. Many acts of communicate include more than one of these types in quick succession.