From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

A conversation amongst participants in a 1972 cross-cultural youth convention.

Dialogue (sometimes spelled dialog in American English[1]) is a written or spoken conversational exchange between two or more people, and a literary and theatrical form that depicts such an exchange. As a philosophical or didactic device, it is chiefly associated in the West with the Socratic dialogue as developed by Plato, but antecedents are also found in other traditions including Indian literature.[2]

Etymology[edit]

The term dialogue stems from the Greek διάλογος (dialogos, conversation); its roots are διά (dia: through) and λόγος (logos: speech, reason). The first extant author who uses the term is Plato, in whose works it is closely associated with the art of dialectic.[3] Latin took over the word as dialogus.[4]

As genre[edit]

Antiquity[edit]

Dialogue as a genre in the Middle East and Asia dates back to ancient works, such as Sumerian disputations preserved in copies from the late third millennium BC,[5] Rigvedic dialogue hymns and the Mahabharata.

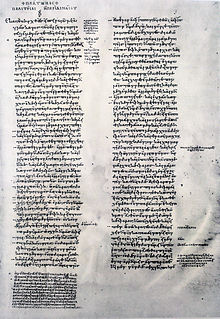

In the West, Plato (c. 437 BC – c. 347 BC) has commonly been credited with the systematic use of dialogue as an independent literary form.[6] Ancient sources indicate, however, that the Platonic dialogue had its foundations in the mime, which the Sicilian poets Sophron and Epicharmus had cultivated half a century earlier.[7] These works, admired and imitated by Plato, have not survived and we have only the vaguest idea of how they may have been performed.[8] The Mimes of Herodas, which were found in a papyrus in 1891, give some idea of their character.[9]

Plato further simplified the form and reduced it to pure argumentative conversation, while leaving intact the amusing element of character-drawing.[10] By about 400 BC he had perfected the Socratic dialogue.[11] All his extant writings, except the Apology and Epistles, use this form.[12]

Following Plato, the dialogue became a major literary genre in antiquity, and several important works both in Latin and in Greek were written. Soon after Plato, Xenophon wrote his own Symposium; also, Aristotle is said to have written several philosophical dialogues in Plato’s style (of which only fragments survive).[13] In the 2nd century CE, Christian apologist Justin Martyr wrote the Dialogue with Trypho, which was a discourse between Justin representing Christianity and Trypho representing Judaism. Another Christian apologetic dialogue from the time was the Octavius, between the Christian Octavius and pagan Caecilius.

Japan[edit]

In the East, in 13th century Japan, dialogue was used in important philosophical works. In the 1200s, Nichiren Daishonin wrote some of his important writings in dialogue form, describing a meeting between two characters in order to present his argument and theory, such as in «Conversation between a Sage and an Unenlightened Man» (The Writings of Nichiren Daishonin 1: pp. 99–140, dated around 1256), and «On Establishing the Correct Teaching for the Peace of the Land» (Ibid., pp. 6–30; dated 1260), while in other writings he used a question and answer format, without the narrative scenario, such as in «Questions and Answers about Embracing the Lotus Sutra» (Ibid., pp. 55–67, possibly from 1263). The sage or person answering the questions was understood as the author.

Modern period[edit]

Two French writers of eminence borrowed the title of Lucian’s most famous collection; both Fontenelle (1683) and Fénelon (1712) prepared Dialogues des morts («Dialogues of the Dead»).[6] Contemporaneously, in 1688, the French philosopher Nicolas Malebranche published his Dialogues on Metaphysics and Religion, thus contributing to the genre’s revival in philosophic circles. In English non-dramatic literature the dialogue did not see extensive use until Berkeley employed it, in 1713, for his treatise, Three Dialogues between Hylas and Philonous.[10] His contemporary, the Scottish philosopher David Hume wrote Dialogues Concerning Natural Religion. A prominent 19th-century example of literary dialogue was Landor’s Imaginary Conversations (1821–1828).[14]

In Germany, Wieland adopted this form for several important satirical works published between 1780 and 1799. In Spanish literature, the Dialogues of Valdés (1528) and those on Painting (1633) by Vincenzo Carducci are celebrated. Italian writers of collections of dialogues, following Plato’s model, include Torquato Tasso (1586), Galileo (1632), Galiani (1770), Leopardi (1825), and a host of others.[10]

In the 19th century, the French returned to the original application of dialogue. The inventions of «Gyp», of Henri Lavedan, and of others, which tell a mundane anecdote wittily and maliciously in conversation, would probably present a close analogy to the lost mimes of the early Sicilian poets. English writers including Anstey Guthrie also adopted the form, but these dialogues seem to have found less of a popular following among the English than their counterparts written by French authors.[10]

The Platonic dialogue, as a distinct genre which features Socrates as a speaker and one or more interlocutors discussing some philosophical question, experienced something of a rebirth in the 20th century. Authors who have recently employed it include George Santayana, in his eminent Dialogues in Limbo (1926, 2nd ed. 1948; this work also includes such historical figures as Alcibiades, Aristippus, Avicenna, Democritus, and Dionysius the Younger as speakers). Also Edith Stein and Iris Murdoch used the dialogue form. Stein imagined a dialogue between Edmund Husserl (phenomenologist) and Thomas Aquinas (metaphysical realist). Murdoch included not only Socrates and Alcibiades as interlocutors in her work Acastos: Two Platonic Dialogues (1986), but featured a young Plato himself as well.[15] More recently Timothy Williamson wrote Tetralogue, a philosophical exchange on a train between four people with radically different epistemological views.

In the 20th century, philosophical treatments of dialogue emerged from thinkers including Mikhail Bakhtin, Paulo Freire, Martin Buber, and David Bohm. Although diverging in many details, these thinkers have proposed a holistic concept of dialogue.[16] Educators such as Freire and Ramón Flecha have also developed a body of theory and techniques for using egalitarian dialogue as a pedagogical tool.[17]

As topic[edit]

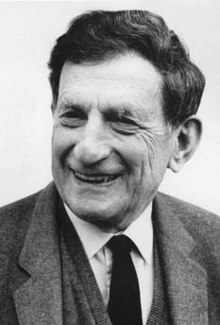

David Bohm, a leading 20th-century thinker on dialogue.

Martin Buber assigns dialogue a pivotal position in his theology. His most influential work is titled I and Thou.[18] Buber cherishes and promotes dialogue not as some purposive attempt to reach conclusions or express mere points of view, but as the very prerequisite of authentic relationship between man and man, and between man and God. Buber’s thought centers on «true dialogue», which is characterized by openness, honesty, and mutual commitment.[19]

The Second Vatican Council placed a major emphasis on dialogue with the World. Most of the council’s documents involve some kind of dialogue : dialogue with other religions (Nostra aetate), dialogue with other Christians (Unitatis Redintegratio), dialogue with modern society (Gaudium et spes) and dialogue with political authorities (Dignitatis Humanae).[20] However, in the English translations of these texts, «dialogue» was used to translate two Latin words with distinct meanings, colloquium («discussion») and dialogus («dialogue»).[21] The choice of terminology appears to have been strongly influenced by Buber’s thought.[22]

The physicist David Bohm originated a related form of dialogue where a group of people talk together in order to explore their assumptions of thinking, meaning, communication, and social effects. This group consists of ten to thirty people who meet for a few hours regularly or a few continuous days. In a Bohm dialogue, dialoguers agree to leave behind debate tactics that attempt to convince and, instead, talk from their own experience on subjects that are improvised on the spot.[23]

In his influential works, Russian philosopher Mikhail Bakhtin provided an extralinguistic methodology for analysing the nature and meaning of dialogue:[24]

Dialogic relations have a specific nature: they can be reduced neither to the purely logical (even if dialectical) nor to the purely linguistic (compositional-syntactic) They are possible only between complete utterances of various speaking subjects… Where there is no word and no language, there can be no dialogic relations; they cannot exist among objects or logical quantities (concepts, judgments, and so forth). Dialogic relations presuppose a language, but they do not reside within the system of language. They are impossible among elements of a language.[25]

The Brazilian educationalist Paulo Freire, known for developing popular education, advanced dialogue as a type of pedagogy. Freire held that dialogued communication allowed students and teachers to learn from one another in an environment characterized by respect and equality. A great advocate for oppressed peoples, Freire was concerned with praxis—action that is informed and linked to people’s values. Dialogued pedagogy was not only about deepening understanding; it was also about making positive changes in the world: to make it better.[26]

As practice[edit]

Dialogue is used as a practice in a variety of settings, from education to business. Influential theorists of dialogal education include Paulo Freire and Ramon Flecha.

In the United States, an early form of dialogic learning emerged in the Great Books movement of the early to mid-20th century, which emphasized egalitarian dialogues in small classes as a way of understanding the foundational texts of the Western canon.[27] Institutions that continue to follow a version of this model include the Great Books Foundation, Shimer College in Chicago,[28] and St. John’s College in Annapolis and Santa Fe.[29]

Egalitarian dialogue[edit]

Egalitarian dialogue is a concept in dialogic learning. It may be defined as a dialogue in which contributions are considered according to the validity of their reasoning, instead of according to the status or position of power of those who make them.[30]

Structured dialogue[edit]

Structured dialogue represents a class of dialogue practices developed as a means of orienting the dialogic discourse toward problem understanding and consensual action. Whereas most traditional dialogue practices are unstructured or semi-structured, such conversational modes have been observed as insufficient for the coordination of multiple perspectives in a problem area. A disciplined form of dialogue, where participants agree to follow a dialogue framework or a facilitator, enables groups to address complex shared problems.[31]

Aleco Christakis (who created structured dialogue design) and John N. Warfield (who created science of generic design) were two of the leading developers of this school of dialogue.[32] The rationale for engaging structured dialogue follows the observation that a rigorous bottom-up democratic form of dialogue must be structured to ensure that a sufficient variety of stakeholders represents the problem system of concern, and that their voices and contributions are equally balanced in the dialogic process.

Structured dialogue is employed for complex problems including peacemaking (e.g., Civil Society Dialogue project in Cyprus) and indigenous community development.,[33] as well as government and social policy formulation.[34]

In one deployment, structured dialogue is (according to a European Union definition) «a means of mutual communication between governments and administrations including EU institutions and young people. The aim is to get young people’s contribution towards the formulation of policies relevant to young peoples lives.»[35] The application of structured dialogue requires one to differentiate the meanings of discussion and deliberation.

Groups such as Worldwide Marriage Encounter and Retrouvaille use dialogue as a communication tool for married couples. Both groups teach a dialogue method that helps couples learn more about each other in non-threatening postures, which helps to foster growth in the married relationship.[36]

Dialogical leadership[edit]

The German philosopher and classicist Karl-Martin Dietz emphasizes the original meaning of dialogue (from Greek dia-logos, i.e. ‘two words’), which goes back to Heraclitus: «The logos […] answers to the question of the world as a whole and how everything in it is connected. Logos is the one principle at work, that gives order to the manifold in the world.»[37] For Dietz, dialogue means «a kind of thinking, acting and speaking, which the logos «passes through»»[38] Therefore, talking to each other is merely one part of «dialogue». Acting dialogically means directing someone’s attention to another one and to reality at the same time.[39]

Against this background and together with Thomas Kracht, Karl-Martin Dietz developed what he termed «dialogical leadership» as a form of organizational management.[40] In several German enterprises and organisations it replaced the traditional human resource management, e.g. in the German drugstore chain dm-drogerie markt.[40]

Separately, and earlier to Thomas Kracht and Karl-Martin Dietz, Rens van Loon published multiple works on the concept of dialogical leadership, starting with a chapter in the 2003 book The Organization as Story.[41]

Moral dialogues[edit]

Moral dialogues are social processes which allow societies or communities to form new shared moral understandings. Moral dialogues have the capacity to modify the moral positions of a sufficient number of people to generate widespread approval for actions and policies that previously had little support or were considered morally inappropriate by many. Communitarian philosopher Amitai Etzioni has developed an analytical framework which—modeling historical examples—outlines the reoccurring components of moral dialogues. Elements of moral dialogues include: establishing a moral baseline; sociological dialogue starters which initiate the process of developing new shared moral understandings; the linking of multiple groups’ discussions in the form of «megalogues»; distinguishing the distinct attributes of the moral dialogue (apart from rational deliberations or culture wars); dramatization to call widespread attention to the issue at hand; and, closure through the establishment of a new shared moral understanding.[42] Moral dialogues allow people of a given community to determine what is morally acceptable to a majority of people within the community.

See also[edit]

- Argumentation theory

- Collaborative leadership

- Deliberation

- Dialogical self

- Dialogue Among Civilizations

- Dialogue (Bakhtin)

- Dialogue mapping

- Intercultural dialogue

- Interfaith dialogue

- Intergroup dialogue

- Rogerian argument

- Speech

Notes[edit]

- ^ See entry on «dialogue (n)» in the Oxford English Dictionary, 2nd ed.

- ^ Nakamura, Hajime (1964). The Ways of Thinking of Eastern Peoples. p. 189. ISBN 978-0824800789.

- ^ Jazdzewska, K. (1 June 2015). «From Dialogos to Dialogue: The Use of the Term from Plato to the Second Century CE». Greek, Roman and Byzantine Studies. 54 (1): 17–36.

- ^ «Dialogue», Oxford English Dictionary, 2nd edition

- ^ G. J., and H. L. J. Vanstiphout. 1991. Dispute Poems and Dialogues in the Ancient and Mediaeval Near East: Forms and Types of Literary Debates in Semitic and Related Literatures. Leuven: Department Oriëntalistiek.

- ^ a b Gosse 1911.

- ^ Kutzko 2012, p. 377.

- ^ Kutzko 2012, p. 381.

- ^ Nairn, John Arbuthnot (1904). The Mimes of Herodas. Clarendon Press. p. ix.

- ^ a b c d Gosse, Edmund (1911). «Dialogue» . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 8 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 156–157.

- ^ Merriam-Webster’s Encyclopedia of Literature. Merriam-Webster, Inc. 1995. pp. 322–323. ISBN 9780877790426.

- ^ Sarton, George (2011). Ancient Science Through the Golden Age of Greece. p. 405. ISBN 9780486274959.

- ^ Bos, A. P. (1989). Cosmic and Meta-Cosmic Theology in Aristotle’s Lost Dialogues. p. xviii. ISBN 978-9004091559.

- ^ Craig, Hardin; Thomas, Joseph M. (1929). «Walter Savage Landor». English Prose of the Nineteenth Century. p. 215.

- ^ Altorf, Marije (2008). Iris Murdoch and the Art of Imagining. Bloomsbury Academic. p. 92. ISBN 9780826497574.

- ^ Phillips, Louise (2011). The Promise of Dialogue: The dialogic turn in the production and communication of knowledge. pp. 25–26. ISBN 9789027210296.

- ^ Flecha, Ramón (2000). Sharing Words: Theory and Practice of Dialogic Learning. Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield.

- ^ Braybrooke, Marcus (2009). Beacons of the Light: 100 Holy People Who Have Shaped the History of Humanity. p. 560. ISBN 978-1846941856.

- ^ Bergman, Samuel Hugo (1991). Dialogical Philosophy from Kierkegaard to Buber. p. 219. ISBN 978-0791406236.

- ^ Nolan 2006.

- ^ Nolan 2006, p. 30.

- ^ Nolan 2006, p. 174.

- ^ Isaacs, William (1999). Dialogue and The Art Of Thinking Together. p. 38. ISBN 978-0307483782.

- ^ Maranhão 1990, p.51

- ^ Bakhtin 1986, p.117

- ^ Goodson, Ivor; Gill, Scherto (2014). Critical Narrative as Pedagogy. Bloomsbury. p. 56. ISBN 9781623566890.

- ^ Bird, Otto A.; Musial, Thomas J. (1973). «Great Books Programs». Encyclopedia of Library and Information Science. Vol. 10. pp. 159–160.

- ^ Jon, Ronson (6 December 2014). «Shimer College: The Worst School in America?». Guardian.

- ^ «Why SJC?». St. John’s College. Retrieved 18 January 2015.

- ^ Flecha, Ramon (2000). Sharing Words. Theory and Practice of Dialogic Learning. Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield.

- ^ Sorenson, R. L. (2011). Family Business and Social Capital. p. xxi. ISBN 978-1849807388.

- ^ Laouris, Yiannis (16 November 2014). «Reengineering and Reinventing both Democracy and the Concept of Life in the Digital Era». In Floridi, Luciano (ed.). The Onlife Manifesto. p. 130. ISBN 978-3319040936.

- ^ Westoby, Peter; Dowling, Gerard (2013). Theory and Practice of Dialogical Community Development. p. 28. ISBN 978-1136272851.

- ^ Denstad, Finn Yrjar (2009). Youth Policy Manual: How to Develop a National Youth Strategy. p. 35. ISBN 978-9287165763.

- ^ Definition of structured dialogue focused on youth matters

- ^ Hunt, Richard A.; Hof, Larry; DeMaria, Rita (1998). Marriage Enrichment: Preparation, Mentoring, and Outreach. p. 13. ISBN 978-0876309131.

- ^ Karl-Martin Dietz: Acting Independently for the Good of the Whole. From Dialogical Leadership to a Dialogical Corporate Culture. Heidelberg: Menon 2013. p. 10.

- ^ Dietz: Acting Independently for the Good of the Whole. p. 10.

- ^ Karl-Martin Dietz: Dialog die Kunst der Zusammenarbeit. 4. Auflage. Heidelberg 2014. p. 7.

- ^ a b Karl-Martin Dietz, Thomas Kracht: Dialogische Führung. Grundlagen — Praxis Fallbeispiel: dm-drogerie markt. 3. Auflage. Frankfurt am Main: Campus 2011.

- ^ De organisatie als verhaal. 2003. ISBN 9789023239468.

- ^ Etzioni, Amitai (2017). «Moral Dialogues». Happiness is the Wrong Metric. Library of Public Policy and Public Administration. Vol. 11. pp. 65–86. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-69623-2_4. ISBN 978-3-319-69623-2.

Bibliography[edit]

- Bakhtin, M. M. (1986) Speech Genres and Other Late Essays. Trans. by Vern W. McGee. Austin, Tx: University of Texas Press.

- Kutzko, David (2012). «In pursuit of Sophron». In Bosher, Kathryn (ed.). Theater Outside Athens: Drama in Greek Sicily and South Italy. p. 377. ISBN 9780521761789.

- Hösle, Vittorio (2013): The Philosophical Dialogue: a Poetics and a Hermeneutics. Trans. by Steven Rendall. Notre Dame, University of Notre Dame Press.

- Maranhão, Tullio (1990) The Interpretation of Dialogue University of Chicago Press ISBN 0-226-50433-6

- Nolan, Ann Michele (2006). A Privileged Moment: Dialogue in the Language of the Second Vatican Council. p. 276. ISBN 978-3039109845.

- E. Di Nuoscio, «Epistemologia del dialogo. Una difesa filosofica del confronto pacifico tra culture», Carocci, Roma, 2011

- Suitner, Riccarda (2022) The Dialogues of the Dead of the Early German Enlightenment. Trans. by Gwendolin Goldbloom. Leiden-Boston: Brill

External links[edit]

Look up dialogue in Wiktionary, the free dictionary.

- «National Coalition for Dialogue and Deliberation». ncdd.org.

- «Strengthening Canadian Democracy | SFU Centre for Dialog». democracydialogue.ca.

Noun

He is an expert at writing dialogue.

There’s very little dialogue in the film.

The best part of the book is the clever dialogue.

Students were asked to read dialogues from the play.

The two sides involved in the labor dispute are trying to establish a dialogue.

The two parties have been in constant dialogue with each other.

See More

Recent Examples on the Web

Sadiq recalled a collaborative relationship that saw Khan tailoring the dialogue and shaping it to her own dialect (the film is in Urdu and Punjabi).

—

But this is one of the senses in which Eliot was, after all, right: Art is in a dynamic dialogue not only with other art but also with objective reality.

—

Organizations engaged in education and workforce development – schools, nonprofits, social innovation organizations, and others – are constantly seeking out opportunities to engage in ongoing dialogue with their peers, identify what works, and adapt the most effective approaches.

—

Occasionally, the action moves so quickly that the dialogue gets lost in the commotion.

—

Body camera footage and security footage of notable incidents, though, has been treated as potentially more useful for public dialogue by platforms, despite it oftentimes depicting violence, killings, police brutality, and other sensitive media.

—

BaianaSystem’s music was in constant dialogue with the country’s zeitgeist.

—

Even before Netanyahu acted, the Israeli President, Isaac Herzog, and the opposition leaders Benny Gantz and Yair Lapid had welcomed an opportunity for a real dialogue; in fact, Herzog had presented his own formula for judicial reform earlier in the month.

—

El-Amin hosted a forum in February 2007 at the Muslim Center that brought together the two groups for dialogue the same week the Nation held its annual convention in Detroit.

—

And do the living and dead continue to dialogue?

—

Visitors are encouraged to dialogue with artists whose works-in-progress are on view June 4 through June 25.

—

How might our politics look different if sincerity claims were an invitation to dialogue rather than a conversation-stopper?

—

Be sure to regularly dialogue with your employees about stress management and burnout, formally through surveys and informally through check-ins.

—

In behind-the-scenes footage shared to her Story, El Moussa and Richards lip synched along to dialogue from her Netflix show.

—

There will be time at the end of the program for audience members to dialogue with the performers.

—

Typically done after a project is completed, snapshots enable managers to dialogue with employees about their performance while the project is still top of mind.

—

Who knows, had Korach and his group agreed to seriously dialogue with Moses, Moses might have calmed them down.

—

See More

These examples are programmatically compiled from various online sources to illustrate current usage of the word ‘dialogue.’ Any opinions expressed in the examples do not represent those of Merriam-Webster or its editors. Send us feedback about these examples.

di·a·logue

or di·a·log (dī′ə-lôg′, -lŏg′)

n.

1.

a. A conversation between two or more people.

b. A discussion of positions or beliefs, especially between groups to resolve a disagreement.

2.

a. Conversation between characters in a drama or narrative.

b. The lines or passages in a script that are intended to be spoken.

3. A literary work written in the form of a conversation: the dialogues of Plato.

4. Music A composition or passage for two or more parts, suggestive of conversational interplay.

v. di·a·logued, di·a·logu·ing, di·a·logues or di·a·loged or di·a·log·ing or di·a·logs

v.tr.

To express as or in a dialogue: dialogued parts of the story.

v.intr.

To engage in a dialogue.

[Middle English dialog, from Old French dialogue, from Latin dialogus, from Greek dialogos, conversation, from dialegesthai, to discuss; see dialect.]

di′a·log′uer n.

Usage Note: Although use of the verb dialogue meaning «to engage in an exchange of views» is widespread, the Usage Panel has little affection for it. In our 2009 survey, 80 percent of the Panel rejected the sentence The department was remiss in not trying to dialogue with representatives of the community before hiring new officers. This represents some erosion of the 98 percent who rejected this example in 1988, but resistance is still very strong. A number of Panelists felt moved to comment on the ugliness or awkwardness of the construction.

American Heritage® Dictionary of the English Language, Fifth Edition. Copyright © 2016 by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company. Published by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company. All rights reserved.

dialogue

(ˈdaɪəˌlɒɡ) or

dialog

n

1. conversation between two or more people

2. an exchange of opinions on a particular subject; discussion

3. (Literary & Literary Critical Terms) the lines spoken by characters in drama or fiction

4. (Literary & Literary Critical Terms) a particular passage of conversation in a literary or dramatic work

5. (Literary & Literary Critical Terms) a literary composition in the form of a dialogue

6. (Government, Politics & Diplomacy) a political discussion between representatives of two nations or groups

vb

7. (tr) to put into the form of a dialogue

8. (intr) to take part in a dialogue; converse

[C13: from Old French dialoge, from Latin dialogus, from Greek dialogos, from dialegesthai to converse; see dialect]

dialogic adj

ˈdiaˌloguer, ˈdiaˌloger n

Collins English Dictionary – Complete and Unabridged, 12th Edition 2014 © HarperCollins Publishers 1991, 1994, 1998, 2000, 2003, 2006, 2007, 2009, 2011, 2014

di•a•logue

or di•a•log

(ˈdaɪ əˌlɔg, -ˌlɒg)

n., v. -logued, -logu•ing. n.

1. conversation between two or more persons.

2. the conversation between characters in a novel, drama, etc.

3. an exchange of ideas or opinions on a particular issue esp. with a view to reaching an amicable agreement.

4. a literary work in the form of a conversation.

v.i.

5. to carry on a dialogue; converse.

6. to discuss areas of disagreement frankly in order to resolve them.

v.t.

7. to put into the form of a dialogue.

[1175–1225; Middle English < Old French dïalogue, Latin dialogus < Greek diálogos, n. derivative of dialégesthai to converse]

di′a•logu`er, n.

Random House Kernerman Webster’s College Dictionary, © 2010 K Dictionaries Ltd. Copyright 2005, 1997, 1991 by Random House, Inc. All rights reserved.

dialogue

a frank exchange of ideas, spoken or written, for the purpose of meeting in harmony.

See also: Agreement

-Ologies & -Isms. Copyright 2008 The Gale Group, Inc. All rights reserved.

dialogue

Past participle: dialogued

Gerund: dialoguing

| Imperative |

|---|

| dialogue |

| dialogue |

| Present |

|---|

| I dialogue |

| you dialogue |

| he/she/it dialogues |

| we dialogue |

| you dialogue |

| they dialogue |

| Preterite |

|---|

| I dialogued |

| you dialogued |

| he/she/it dialogued |

| we dialogued |

| you dialogued |

| they dialogued |

| Present Continuous |

|---|

| I am dialoguing |

| you are dialoguing |

| he/she/it is dialoguing |

| we are dialoguing |

| you are dialoguing |

| they are dialoguing |

| Present Perfect |

|---|

| I have dialogued |

| you have dialogued |

| he/she/it has dialogued |

| we have dialogued |

| you have dialogued |

| they have dialogued |

| Past Continuous |

|---|

| I was dialoguing |

| you were dialoguing |

| he/she/it was dialoguing |

| we were dialoguing |

| you were dialoguing |

| they were dialoguing |

| Past Perfect |

|---|

| I had dialogued |

| you had dialogued |

| he/she/it had dialogued |

| we had dialogued |

| you had dialogued |

| they had dialogued |

| Future |

|---|

| I will dialogue |

| you will dialogue |

| he/she/it will dialogue |

| we will dialogue |

| you will dialogue |

| they will dialogue |

| Future Perfect |

|---|

| I will have dialogued |

| you will have dialogued |

| he/she/it will have dialogued |

| we will have dialogued |

| you will have dialogued |

| they will have dialogued |

| Future Continuous |

|---|

| I will be dialoguing |

| you will be dialoguing |

| he/she/it will be dialoguing |

| we will be dialoguing |

| you will be dialoguing |

| they will be dialoguing |

| Present Perfect Continuous |

|---|

| I have been dialoguing |

| you have been dialoguing |

| he/she/it has been dialoguing |

| we have been dialoguing |

| you have been dialoguing |

| they have been dialoguing |

| Future Perfect Continuous |

|---|

| I will have been dialoguing |

| you will have been dialoguing |

| he/she/it will have been dialoguing |

| we will have been dialoguing |

| you will have been dialoguing |

| they will have been dialoguing |

| Past Perfect Continuous |

|---|

| I had been dialoguing |

| you had been dialoguing |

| he/she/it had been dialoguing |

| we had been dialoguing |

| you had been dialoguing |

| they had been dialoguing |

| Conditional |

|---|

| I would dialogue |

| you would dialogue |

| he/she/it would dialogue |

| we would dialogue |

| you would dialogue |

| they would dialogue |

| Past Conditional |

|---|

| I would have dialogued |

| you would have dialogued |

| he/she/it would have dialogued |

| we would have dialogued |

| you would have dialogued |

| they would have dialogued |

Collins English Verb Tables © HarperCollins Publishers 2011

ThesaurusAntonymsRelated WordsSynonymsLegend:

| Noun | 1. |  dialogue — a conversation between two persons dialogue — a conversation between two persons

dialog, duologue talk, talking — an exchange of ideas via conversation; «let’s have more work and less talk around here» |

| 2. | dialogue — the lines spoken by characters in drama or fiction

dialog playscript, script, book — a written version of a play or other dramatic composition; used in preparing for a performance duologue — a part of the script in which the speaking roles are limited to two actors actor’s line, words, speech — words making up the dialogue of a play; «the actor forgot his speech» |

|

| 3. | dialogue — a literary composition in the form of a conversation between two people; «he has read Plato’s Dialogues in the original Greek»

dialog literary composition, literary work — imaginative or creative writing |

|

| 4. |  dialogue — a discussion intended to produce an agreement; «the buyout negotiation lasted several days»; «they disagreed but kept an open dialogue»; «talks between Israelis and Palestinians» dialogue — a discussion intended to produce an agreement; «the buyout negotiation lasted several days»; «they disagreed but kept an open dialogue»; «talks between Israelis and Palestinians»

negotiation, talks give-and-take, discussion, word — an exchange of views on some topic; «we had a good discussion»; «we had a word or two about it» parley — a negotiation between enemies diplomacy, diplomatic negotiations — negotiation between nations bargaining — the negotiation of the terms of a transaction or agreement collective bargaining — negotiation between an employer and trade union horse trading — negotiation accompanied by mutual concessions and shrewd bargaining mediation — a negotiation to resolve differences that is conducted by some impartial party |

Based on WordNet 3.0, Farlex clipart collection. © 2003-2012 Princeton University, Farlex Inc.

dialogue

Collins Thesaurus of the English Language – Complete and Unabridged 2nd Edition. 2002 © HarperCollins Publishers 1995, 2002

dialogue

or dialog

noun

The American Heritage® Roget’s Thesaurus. Copyright © 2013, 2014 by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company. Published by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company. All rights reserved.

Translations

dialog

dialogsamtale

vuoropuheludialogi

dijalog

párbeszéd

samtalsamtal; tvítal

対話対話形式討論

대화

dialogas

dialogs

dialóg

dialog

การสนทนา

cuộc đối thoại

dialogue

dialog (US) [ˈdaɪəlɒg]

Collins Spanish Dictionary — Complete and Unabridged 8th Edition 2005 © William Collins Sons & Co. Ltd. 1971, 1988 © HarperCollins Publishers 1992, 1993, 1996, 1997, 2000, 2003, 2005

dialogue

[ˈdaɪəlɒg] dialog (US) n

Collins English/French Electronic Resource. © HarperCollins Publishers 2005

dialogue

, (US) dialog

n (all senses) → Dialog m; dialogue box (Comput) → Dialogfeld nt; dialogue coach → Dialogregisseur(in) m(f)

Collins German Dictionary – Complete and Unabridged 7th Edition 2005. © William Collins Sons & Co. Ltd. 1980 © HarperCollins Publishers 1991, 1997, 1999, 2004, 2005, 2007

Collins Italian Dictionary 1st Edition © HarperCollins Publishers 1995

dialogue

(ˈdaiəlog) (American) dialog(ue) noun

(a) talk between two or more people, especially in a play or novel.

Kernerman English Multilingual Dictionary © 2006-2013 K Dictionaries Ltd.

dialogue

→ حِوَار dialog dialog Dialog διάλογος diálogo vuoropuhelu dialogue dijalog dialogo 対話 대화 dialoog dialog dialog diálogo диалог dialog การสนทนา diyalog cuộc đối thoại 对话

Multilingual Translator © HarperCollins Publishers 2009

- Albanian: dialog (sq) m, bisedë (sq) f

- Arabic: حِوَار (ar) m (ḥiwār), مُحَادَثَة f (muḥādaṯa), مُكَالَمَة f (mukālama)

- Armenian: երկխոսություն (hy) (erkxosutʿyun), զրույց (hy) (zruycʿ)

- Azerbaijani: dialoq (az), söhbət (az), qonuşma

- Belarusian: дыяло́г m (dyjalóh), размо́ва f (razmóva), гу́тарка f (hútarka), дыялёг m (dyjaljóh) (Taraškievica)

- Bengali: সংলাপ (śoṅlap)

- Bulgarian: ра́зговор (bg) m (rázgovor), диало́г (bg) m (dialóg), бесе́да (bg) f (beséda)

- Burmese: အပြော (my) (a.prau:)

- Catalan: diàleg (ca) m

- Chinese:

- Mandarin: 對話/对话 (zh) (duìhuà), 會話/会话 (zh) (huìhuà), 對白/对白 (zh) (duìbái)

- Czech: dialog (cs) m, konverzace (cs) f, rozhovor (cs) m

- Danish: dialog (da) c, samtale (da) c, konversation c

- Dutch: dialoog (nl) m, gesprek (nl) n

- Estonian: dialoog, vestlus (et), kahekõne

- Finnish: dialogi (fi), vuoropuhelu (fi)

- French: dialogue (fr) m, conversation (fr) f

- Galician: diálogo m

- Georgian: დიალოგი (dialogi), საუბარი (saubari)

- German: Dialog (de) m, Gespräch (de) n

- Greek: διάλογος (el) (diálogos), συνομιλία (el) f (synomilía)

- Ancient: διάλογος m (diálogos)

- Gujarati: સંવાદ (sãvād)

- Hebrew: (between two parties) דּוּ שִׂיחַ (he) m (du-syakh), שִׂיחָה (he) f (sikha)

- Hindi: बातचीत (hi) f (bātcīt), गुफ़्तगू f (guftagū), गुफ्तगू (hi) f (guphtagū), बात (hi) m (bāt), सुहबत (hi) m (suhbat), संभाषण (hi) m (sambhāṣaṇ), संवाद (hi) m (samvād)

- Hungarian: párbeszéd (hu), (conversation) beszélgetés (hu), (conversation) társalgás (hu)

- Icelandic: samtal (is) n

- Indonesian: dialog (id), percakapan (id)

- Italian: dialogo (it) m, conversazione (it) f, discorso (it) m

- Japanese: 対談 (ja) (たいだん, taidan), 対話 (ja) (たいわ, taiwa)

- Kashubian: rozgòwôr m

- Kazakh: сөйлесім (kk) (söilesım), диалог (dialog), сұхбат (kk) (sūxbat), үнқатысу (ünqatysu)

- Korean: 대화(對話) (ko) (daehwa), 회화(會話) (ko) (hoehwa)

- Kyrgyz: сүйлөшүү (ky) (süylöşüü), диалог (dialog)

- Lao: ການສົນທະນາ (lo) (kān son tha nā)

- Latin: colloquium (la) n, sermō (la) m

- Latvian: dialogs m, saruna f

- Lithuanian: dialogas (lt) m, pokalbis m

- Macedonian: дијалог m (dijalog), разговор (mk) m (razgovor)

- Malay: dialog, perbualan (ms), percakapan

- Malayalam: സംഭാഷണം (ml) (sambhāṣaṇaṃ)

- Maori: whakawhitinga kōrero

- Mongolian:

- Cyrillic: яриа (mn) (jaria), үг (mn) (üg)

- Norwegian:

- Bokmål: dialog m, samtale (no) m, konversasjon m

- Pashto: سکالو (ps) f (skāló)

- Persian: گفتگو (fa) (goftogu, goftegu, goft-gu), صحبت (fa) (sohbat), مکالمه (fa) (mokâleme)

- Polish: dialog (pl) m, rozmowa (pl) f, konwersacja (pl) f

- Portuguese: diálogo (pt), conversa (pt) f, conversação (pt) f

- Romanian: dialog (ro), conversație (ro) f

- Russian: диало́г (ru) m (dialóg), разгово́р (ru) m (razgovór), бесе́да (ru) f (beséda)

- Scottish Gaelic: còmhradh m, seanchas m, agallamh m

- Serbo-Croatian:

- Cyrillic: дија̀лог m, ра̏згово̄р m

- Roman: dijàlog (sh) m, rȁzgovōr (sh) m

- Slovak: dialóg m, rozhovor m, konverzácia f

- Slovene: dialog m, pogovor (sl) m

- Spanish: diálogo (es) m, conversación (es) f

- Swedish: dialog (sv), samtal (sv) n, konversation (sv) c

- Tagalog: dalwausap

- Tajik: муколама (mukolama), гуфтугӯ (tg) (guftugü), сӯхбат (süxbat)

- Tamil: உரையாடல் (ta) (uraiyāṭal)

- Tatar: диалог (dialoğ)

- Telugu: సంభాషణ (te) (sambhāṣaṇa)

- Thai: การสนทนา (th) (gaan-sǒn-tá-naa), บทพูด

- Tok Pisin: toktok

- Turkish: diyalog (tr), sohbet (tr), konuşma (tr)

- Turkmen: gürrüň, söhbet, dialog

- Ukrainian: діало́г m (dialóh), розмо́ва f (rozmóva), бе́сіда (uk) f (bésida)

- Urdu: بات چیت (ur) f (bāt cīt)

- Uyghur: دىئالوگ (di’alog), سۆھبەت (söhbet)

- Uzbek: suhbat (uz), mukolama (uz), dialog (uz)

- Vietnamese: (cuộc) đối thoại (vi), sự hội thoại (vi)

You can also hear him as the newscaster, although the main dialogue is subtitled in English. ❋ Unknown (2010)

But “reading comprehension” in dialogue is a two-way street kind of thing. ❋ Unknown (2010)

If the only way to engage the DKE boys in dialogue is to ignore the gravity of their offence, as the YDN was inclined to do, nothing would be gained. ❋ Leah Anthony Libresco (2010)

Here, the term dialogue is used in a broader sense concerning interactions between various forms of government: in this case, dialogue between provincial and federal governments on division of powers disputes. ❋ Ahsan Mirza (2009)

Some of the dialogue is a little stilted, and is the stuff that looks great on paper but rings odd when spoken aloud. ❋ Unknown (2009)

— Generally, I think the dialogue is a lot better. ❋ Unknown (2009)

But here, the dialogue is all building up tension to the violent release, which is what Tarantino does best. ❋ Darkerblogistan (2009)

But this dialogue is a nice illustration of why science can’t do what Intelligent Design-phreaks and atheists claim it can do. ❋ M_francis (2009)

The action sequences that start around 1: 45 look pretty spectacular, but the jokes are stale and the dialogue is awful. ❋ Unknown (2010)

The cumulative effect of this dialogue is a sense of thoroughgoing fidelity to the speech patterns of these characters as rooted in country, region, class, and time period. ❋ Unknown (2009)

It’s a tricky business, I tell you, but this dialogue is absolutely refreshing — and absolutely crucial. ❋ Unknown (2009)

Still, any movie with this dialogue is alright with me: ❋ Unknown (2010)

Think about this for a minute, comics are like a script, all the dialogue is there, all the scenes are set, characters established and a fanbase ready and waiting. ❋ Unknown (2008)

The key to winning the dialogue is actually to respect and engage the enemy. ❋ Unknown (2008)

Many of the motifs and images here seem recycled from previous war novels and movies, but Benioff’s palpable love for his grandfather animates the book and lends it heart, and the dialogue is as funny and sharp as he wants it to be. ❋ Unknown (2008)

The “mundane” moments of comedy, when the dialogue is able to shine. ❋ Unknown (2007)

It drags on a little more slowly, the dialogue is a shade grayer, the cardboard out of which the characters are cut is a shade thinner, and the cheating is a little more obvious. ❋ Unknown (2007)

❋ Larstait (2003)

❋ Me (2003)

«I hate dialogue«said [jimbe]

«Nuke Uranus»said josh

«hail hitler» your brother enfoced

«Its not you its me»said your new Ex

«I like bananas»I said

«I don’t like how today went so I think I might go back in time to September 10, 2001 at 11:00 pm and sit on top of The World [Trade Center] wondering who will remember me if I die or if anyone would be sad if I died. I would wait there until 8:45 am when I would fall off in a fire ball of skin. Now I know you may be think I commited suicide but I really didn’t. You see a plane would have killed me, not myself. So after no one remembers me I would have [unfinished business] and [haught] the hell out of people. Causing this to happen multiple times from my victims. which would eventually cause a paradox, ultimately leading All of the trash human race into a dark and empty rift of time. And even then people would still not remember me. I AM A NOBODY.»said ( ͡° ͜ʖ ͡°) ❋ Thatoneguynooneknows (2016)

The [Pepe] meme showed how the [engineered Dialogue] travels from a few obscure message board posts on 4Chan to troll Hillary Clinton in [the 2016 election] ❋ Cy-Fi (2017)

Tim: [Half life 3] isn’t confirmed

Tom: Stfu! Our names have 3 letters, illuminate has a triangle, triangles have 3 sides therefore Half life 3 is confirmed.

[Katey]: Damn, you guys are having [a legit dialogue] ❋ J Mellow (2015)

Matt: «Overall, I would say that Sarah Palin is a very intelligent woman.»

Scott: «I call [Thong Dialogue] on you; that woman does not have an I.Q. above 90.»

Matt: «Yeah, I guess I did leave my ass [uncovered] on that one. My argument was wearing a [thongLet’s] go pick up chicks.» ❋ MCBassGuitar (2015)

[Carol] is a real [rug-muncher], she participates in vagina dialogues at least [twice] a night. ❋ Cam Nielsen (2008)

The only thing that is getting me [throught] the [week] is the thought of [Friday’s] Dialogue Circle. ❋ Advisor Of Sorts (2006)

There’s a few movies that want the bad lines off their script back when the girl is done trying to get rich off dialogue that came out years ago. She really has people she recruits to [intervene] in her disputes saying lines to people that could come from [Roadhouse] or [Swat] in a real life event. Stolen dialogue is not original or authentic dialogue. ❋ The Original Agahnim (2021)

J — «You should have seen the fish I caught. It was HUGE! It was 29″ and [at least 6].2lbs.»

D- «Did you measure and weigh it? Was it a new record?»

J — «Well… I put it on the hood of my truck and by the size and how the hood began to»

D — «Loaf Dialogue!»

(Imaginary whistle blows in the background, the subtle sounds of [echoing] ‘BULLSHIT’ is heard! Silence ensue’s… for approx 3-5 seconds.)

J — «Well I didn’t exactly get the measurement/weight, but it was a [big fish].» ❋ Dingle B (2011)

Dialogue Definition

What is dialogue? Here’s a quick and simple definition:

Dialogue is the exchange of spoken words between two or more characters in a book, play, or other written work. In prose writing, lines of dialogue are typically identified by the use of quotation marks and a dialogue tag, such as «she said.» In plays, lines of dialogue are preceded by the name of the person speaking. Here’s a bit of dialogue from Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland:

- «Oh, you can’t help that,’ said the Cat: ‘we’re all mad here. I’m mad. You’re mad.»

- «How do you know I’m mad?» said Alice.

- «You must be,’ said the Cat, ‘or you wouldn’t have come here.»

Some additional key details about dialogue:

- Dialogue is defined in contrast to monologue, when only one person is speaking.

- Dialogue is often critical for moving the plot of a story forward, and can be a great way of conveying key information about characters and the plot.

- Dialogue is also a specific and ancient genre of writing, which often takes the form of a philosophical investigation carried out by two people in conversation, as in the works of Plato. This entry, however, deals with dialogue as a narrative element, not as a genre.

How to Pronounce Dialogue

Here’s how to pronounce dialogue: dye-uh-log

Dialogue in Depth

Dialogue is used in all forms of writing, from novels to news articles to plays—and even in some poetry. It’s a useful tool for exposition (i.e., conveying the key details and background information of a story) as well as characterization (i.e., fleshing out characters to make them seem lifelike and unique).

Dialogue as an Expository Tool

Dialogue is often a crucial expository tool for writers—which is just another way of saying that dialogue can help convey important information to the reader about the characters or the plot without requiring the narrator to state the information directly. For instance:

- In a book with a first person narrator, the narrator might identify themselves outright (as in Kazuo Ishiguro’s Never Let Me Go, which begins «My name is Kathy H. I am thirty-one years old, and I’ve been a carer now for over eleven years.»).

- But if the narrator doesn’t identify themselves by stating their name and age directly, dialogue can be a useful tool for finding out important things about the narrator. For instance, in The Great Gatsby, the reader learns the name of the narrator (Nick) through the following line of dialogue:

- Tom Buchanan, who had been hovering restlessly about the room, stopped and rested his hand on my shoulder. «What you doing, Nick?”

The above example is just one scenario in which important information might be conveyed indirectly through dialogue, allowing writers to show rather than tell their readers the most important details of the plot.

Expository Dialogue in Plays and Films

Dialogue is an especially important tool for playwrights and screenwriters, because most plays and films rely primarily on a combination of visual storytelling and dialogue to introduce the world of the story and its characters. In plays especially, the most basic information (like time of day) often needs to be conveyed through dialogue, as in the following exchange from Romeo and Juliet:

BENVOLIO

Good-morrow, cousin.

ROMEO

Is the day so young?

BENVOLIO

But new struck nine.

ROMEO

Ay me! sad hours seem long.

Here you can see that what in prose writing might have been conveyed with a simple introductory clause like «Early the next morning…» instead has to be conveyed through dialogue.

Dialogue as a Tool for Characterization

In all forms of writing, dialogue can help writers flesh out their characters to make them more lifelike, and give readers a stronger sense of who each character is and where they come from. This can be achieved using a combination of:

- Colloquialisms and slang: Colloquialism is the use of informal words or phrases in writing or speech. This can be used in dialogue to establish that a character is from a particular time, place, or class background. Similarly, slang can be used to associate a character with a particular social group or age group.

- The form the dialogue takes: for instance, multiple books have now been written in the form of text messages between characters—a form which immediately gives readers some hint as to the demographic of the characters in the «dialogue.»

- The subject matter: This is the obvious one. What characters talk about can tell readers more about them than how the characters speak. What characters talk about reveals their fears and desires, their virtues and vices, their strengths and their flaws.

For example, in Pride and Prejudice, Jane Austen’s narrator uses dialogue to introduce Mrs. and Mr. Bennet, their relationship, and their differing attitudes towards arranging marriages for their daughters:

«A single man of large fortune; four or five thousand a year. What a fine thing for our girls!”

“How so? How can it affect them?”

“My dear Mr. Bennet,” replied his wife, “how can you be so tiresome! You must know that I am thinking of his marrying one of them.”

“Is that his design in settling here?”

“Design! Nonsense, how can you talk so! But it is very likely that he may fall in love with one of them, and therefore you must visit him as soon as he comes.”

This conversation is an example of the use of dialogue as a tool of characterization, showing readers—without explaining it directly—that Mrs. Bennet is preoccupied with arranging marriages for her daughters, and that Mr. Bennet has a deadpan sense of humor and enjoys teasing his wife.

Recognizing Dialogue in Different Types of Writing

It’s important to note that how a writer uses dialogue changes depending on the form in which they’re writing, so it’s useful to have a basic understanding of the form dialogue takes in prose writing (i.e., fiction and nonfiction) versus the form it takes in plays and screenplays—as well as the different functions it can serve in each. We’ll cover that in greater depth in the sections that follow.

Dialogue in Prose

In prose writing, which includes fiction and nonfiction, there are certain grammatical and stylistic conventions governing the use of dialogue within a text. We won’t cover all of them in detail here (we’ll skip over the placement of commas and such), but here are some of the basic rules for organizing dialogue in prose:

- Punctuation: Generally speaking, lines of dialogue are encased in double quotation marks «such as this,» but they may also be encased in single quotation marks, ‘such as this.’ However, single quotation marks are generally reserved for quotations within a quotation, e.g., «Even when I dared him he said ‘No way,’ so I dropped the subject.»

-

Dialogue tags: Dialogue tags (such as «he asked» or «she said») are used to attribute a line of dialogue to a specific speaker. They can be placed before or after a line of dialogue, or even in the middle of a sentence, but some lines of dialogue don’t have any tags at all because it’s already clear who is speaking. Here are a few examples of lines of dialogue with dialogue tags:

- «Where did you go?» she asked.

- I said, «Leave me alone.»

- «Answer my question,» said Monica, «or I’m leaving.»

- Line breaks: Lines of dialogue spoken by different speakers are generally separated by line breaks. This is helpful for determining who is speaking when dialogue tags have been omitted.

Of course, some writers ignore these conventions entirely, choosing instead to italicize lines of dialogue, for example, or not to use quotation marks, leaving lines of dialogue undifferentiated from other text except for the occasional use of a dialogue tag. Writers that use nonstandard ways of conveying dialogue, however, usually do so in a consistent way, so it’s not hard to figure out when someone is speaking, even if it doesn’t look like normal dialogue.

Indirect vs. Direct Dialogue

In prose, there are two main ways for writers to convey the content of a conversation between two characters: directly, and indirectly. Here’s an overview of the difference between direct and indirect dialogue:

-

Indirect Dialogue: In prose, dialogue is often summarized without using any direct quotations (as in «He told her he was having an affair, and she replied callously that she didn’t love him anymore, at which point they parted ways»). When dialogue is summarized in this way, it is called «indirect dialogue.» It’s useful when the writer wants the reader to understand that a conversation has taken place, and to get the gist of what each person said, but doesn’t feel that it’s necessary to convey what each person said word-for-word.

- This type of dialogue can often help lend credibility or verisimilitude to dialogue in a story narrated in the first-person, since it’s unlikely that a real person would remember every line of dialogue that they had overheard or spoken.

- Direct Dialogue: This is what most people are referring to when they talk about dialogue. In contrast to indirect dialogue, direct dialogue is when two people are speaking and their words are in quotations.

Of these two types of dialogue, direct dialogue is the only one that counts as dialogue strictly speaking. Indirect dialogue, by contrast, is technically considered to be part of a story’s narration.

A Note on Dialogue Tags and «Said Bookisms»

It is pretty common for writers to use verbs other than «said» and «asked» to attribute a line of dialogue to a speaker in a text. For instance, it’s perfectly acceptable for someone to write:

- Robert was beginning to get worried. «Hurry!» he shouted.

- «I am hurrying,» Nick replied.

However, depending on how it’s done, substituting different verbs for «said» can be quite distracting, since it shifts the reader’s attention away from the dialogue and onto the dialogue tag itself. Here’s an example where the use of non-standard dialogue tags begins to feel a bit clumsy:

- Helen was thrilled. «Nice to meet you,» she beamed.

- «Nice to meet you, too,» Wendy chimed.

Dialogue tags that use verbs other than the standard set (which is generally thought to include «said,» «asked,» «replied,» and «shouted») are known as «said bookisms,» and are generally ill-advised. But these «bookisms» can be easily avoided by using adverbs or simple descriptions in conjunction with one of the more standard dialogue tags, as in:

- Helen was thrilled. «Nice to meet you,» she said, beaming.

- «Nice to meet you, too,» Wendy replied brightly.

In the earlier version, the irregular verbs (or «said bookisms») draw attention to themselves, distracting the reader from the dialogue. By comparison, this second version reads much more smoothly.

Dialogue in Plays

Dialogue in plays (and screenplays) is easy to identify because, aside from the stage directions, dialogue is the only thing a play is made of. Here’s a quick rundown of the basic rules governing dialogue in plays:

- Names: Every line of dialogue is preceded by the name of the person speaking.

-

Adverbs and stage directions: Sometimes an adverb or stage direction will be inserted in brackets or parentheses between the name of the speaker and the line of dialogue to specify how it should be read, as in:

- Mama (outraged) : What kind of way is that to talk about your brother?

- Line breaks: Each time someone new begins speaking, just as in prose, the new line of dialogue is separated from the previous one by a line break.

Rolling all that together, here’s an example of what dialogue looks like in plays, from Edward Albee’s Zoo Story:

JERRY: And what is that cross street there; that one, to the right?

PETER: That? Oh, that’s Seventy-fourth Street.

JERRY: And the zoo is around Sixty-5th Street; so, I’ve been walking north.

PETER: [anxious to get back to his reading] Yes; it would seem so.

JERRY: Good old north.

PETER: [lightly, by reflex] Ha, ha.

Dialogue Examples

The following examples are taken from all types of literature, from ancient philosophical texts to contemporary novels, showing that dialogue has always been an integral feature of many different types of writing.

Dialogue in Shakespeare’s Othello

In this scene from Othello, the dialogue serves an expository purpose, as the messenger enters to deliver news about the unfolding military campaign by the Ottomites against the city of Rhodes.

First Officer

Here is more news.Enter a Messenger

Messenger

The Ottomites, reverend and gracious,

Steering with due course towards the isle of Rhodes,

Have there injointed them with an after fleet.First Senator

Ay, so I thought. How many, as you guess?Messenger

Of thirty sail: and now they do restem

Their backward course, bearing with frank appearance

Their purposes toward Cyprus. Signior Montano,

Your trusty and most valiant servitor,

With his free duty recommends you thus,

And prays you to believe him.

Dialogue in Madeleine L’Engel’s A Wrinkle in Time

From the classic children’s book A Wrinkle in Time, here’s a good example of dialogue that uses a description of a character’s tone of voice instead of using unconventional verbiage to tag the line of dialogue. In other words, L’Engel doesn’t follow Calvin’s line of dialogue with a distracting tag like «Calvin barked.» Rather, she simply states that his voice was unnaturally loud.

«I’m different, and I like being different.» Calvin’s voice was unnaturally loud.

«Maybe I don’t like being different,» Meg said, «but I don’t want to be like everybody else, either.»

It’s also worth noting that this dialogue helps characterize Calvin as a misfit who embraces his difference from others, and Meg as someone who is concerned with fitting in.

Dialogue in A Visit From the Good Squad

This passage from Jennifer Egan’s A Visit From the Good Squad doesn’t use dialogue tags at all. In this exchange between Alex and the unnamed woman, it’s always clear who’s speaking even though most of the lines of dialogue are not explicitly attributed to a speaker using tags like «he said.»

Alex turns to the woman. “Where did this happen?”

“In the ladies’ room. I think.”

“Who else was there?”

“No one.”

“It was empty?”

“There might have been someone, but I didn’t see her.”

Alex swung around to Sasha. “You were just in the bathroom,” he said. “Did you see anyone?”

Elsewhere in the book, Egan peppers her dialogue with colloquialisms and slang to help with characterization. Here, the washed-up, alcoholic rock star Bosco says:

«I want interviews, features, you name it,» Bosco went on. «Fill up my life with that shit. Let’s document every fucking humiliation. This is reality, right? You don’t look good anymore twenty years later, especially when you’ve had half your guts removed. Time’s a goon, right? Isn’t that the expression?»

In this passage, Bosco’s speech is littered with colloquialisms, including profanity and his use of the word «guts» to describe his liver, establishing him as a character with a unique way of speaking.

Dialogue in Plato’s Meno

The following passage is excerpted from a dialogue by Plato titled Meno. This text is one of the more well-known Socratic dialogues. The two characters speaking are Socrates (abbreviated, «Soc.») and Meno (abbreviated, «Men.»). They’re exploring the subject of virtue together.

Soc. Now, if there be any sort-of good which is distinct from knowledge, virtue may be that good; but if knowledge embraces all good, then we shall be right in think in that virtue is knowledge?

Men. True.

Soc. And virtue makes us good?

Men. Yes.

Soc. And if we are good, then we are profitable; for all good things are profitable?

Men. Yes.

Soc. Then virtue is profitable?

Men. That is the only inference.

Indirect Dialogue in Tim O’Brien’s The Things They Carried

This passage from O’Brien’s The Things They Carried exemplifies the use of indirect dialogue to summarize a conversation. Here, the third-person narrator tells how Kiowa recounts the death of a soldier named Ted Lavender. Notice how the summary of the dialogue is interwoven with the rest of the narrative.

They marched until dusk, then dug their holes, and that night Kiowa kept explaining how you had to be there, how fast it was, how the poor guy just dropped like so much concrete. Boom-down, he said. Like cement.

O’Brien takes liberties in his use of quotation marks and dialogue tags, making it difficult at times to distinguish between the voices of different speakers and the voice of the narrator. In the following passage, for instance, it’s unclear who is the speaker of the final sentence:

The cheekbone was gone. Oh shit, Rat Kiley said, the guy’s dead. The guy’s dead, he kept saying, which seemed profound—the guy’s dead. I mean really.

Why Do Writers Use Dialogue in Literature?

Most writers use dialogue simply because there is more than one character in their story, and dialogue is a major part of how the plot progresses and characters interact. But in addition to the fact that dialogue is virtually a necessary component of fiction, theater, and film, writers use dialogue in their work because:

- It aids in characterization, helping to flesh out the various characters and make them feel lifelike and individual.

- It is a useful tool of exposition, since it can help convey key information abut the world of the story and its characters.

- It moves the plot along. Whether it takes the form of an argument, an admission of love, or the delivery of an important piece of news, the information conveyed through dialogue is often essential not only to readers’ understanding of what’s going on, but to generating the action that furthers the story’s plot line.

Other Helpful Dialogue Resources

- The Wikipedia Page on Dialogue: A bare-bones explanation of dialogue in writing, with one or two examples.

- The Dictionary Definition of Dialogue: A basic definition, with a bit on the etymology of the word (it comes from the Greek meaning «through discourse.»

- Cinefix’s video with their take on the 14 best dialogues of all time: A smart overview of what dialogue can accomplish in film.

Definition of Dialogue

Dialogue is a conversation between two or more people in a work of literature. Dialogue can be written or spoken. It is found in prose, some poetry, and makes up the majority of plays. Dialogue is a literary device that can be used for narrative, philosophical, or didactic purposes. The Ancient Greek philosopher Socrates was a chief proponent of dialogue, and the Socratic Method that is named after him involves a great deal of asking and pondering over questions.

The word dialogue comes from the Greek word διάλογος (dialogos), which means “conversation,” and is a compound of words meaning “through” and “reason or speech.” Thus, the definition of dialogue developed as a way of creating meaning through speech.

Common Examples of Dialogue

Dialogue is an important aspect of every day life, and plays a large part in business and political negotiations, as well as in education and conflict resolution in any type of relationship. People who have different opinions and backgrounds are often encouraged to come together in dialogue to understand the other person’s thinking better.

Dialogue forms a large part of all parts of life, and can be used for humorous purposes as well, such as between the comedian duo Abbott and Costello:

Abbott: Strange as it may seem, they give ball players nowadays very peculiar names.

Costello: Funny names?

Abbott: Nicknames, nicknames. Now, on the St. Louis team we have Who’s on first, What’s on second, I Don’t Know is on third–

Costello: That’s what I want to find out. I want you to tell me the names of the fellows on the St. Louis team.

Abbott: I’m telling you. Who’s on first, What’s on second, I Don’t Know is on third–

Costello: You know the fellows’ names?

Abbott: Yes.

Costello: Well, then who’s playing first?

Abbott: Yes.

Costello: I mean the fellow’s name on first base.

Abbott: Who.

Costello: The fellow playin’ first base.

Abbott: Who.

Costello: The guy on first base.

Abbott: Who is on first.

Costello: Well, what are you askin’ me for?

Abbott: I’m not asking you–I’m telling you. Who is on first.

Costello: I’m asking you–who’s on first?

Abbott: That’s the man’s name.

Costello: That’s who’s name?

Abbott: Yes.

Significance of Dialogue in Literature

Dialogue plays a large part in almost all works of fiction, while forming the majority of every play, even the absurdist ones. Indeed, the goal of most works of drama is to highlight the relationships between different characters by way of dialogue. There are some examples of dialogue in poetry as well, though it is rarer. Dialogue is not just words spoken; instead, dialogue reflects an active choice made on the part of each character to instigate conflict and resolve problems, ask and answer questions, and push the narrative along in numerous ways. The way that characters speak hints at their underlying psychoses, desires, motivations, opinions, and so on. Thus, dialogue is not a superfluous aspect of a piece of literature but a fundamental way in which characters interact, change, reach conclusions, and make decisions to act.

There are examples of dialogues dating back to the third millennium BC in works from the Middle East and Asia. The Greek philosopher Plato adopted his mentor Socrates’s method of dialogue to examine different belief systems.

Examples of Dialogue in Literature

Example #1

ROMEO: (taking JULIET’s hand) If I profane with my unworthiest hand

This holy shrine, the gentle sin is this:

My lips, two blushing pilgrims, ready stand

To smooth that rough touch with a tender kiss.

JULIET: Good pilgrim, you do wrong your hand too much,

Which mannerly devotion shows in this,

For saints have hands that pilgrims’ hands do touch,

And palm to palm is holy palmers’ kiss.

ROMEO: Have not saints lips, and holy palmers too?

JULIET: Ay, pilgrim, lips that they must use in prayer.

ROMEO: O, then, dear saint, let lips do what hands do.

They pray; grant thou, lest faith turn to despair.

(Romeo and Juliet by William Shakespeare)

In this example of dialogue, the characters of Romeo and Juliet begin to fall in love. In this excerpt the language they use is very powerful because it has a real effect on both of them. Using wit and euphemism, the two teenagers charm each other and share their first kiss. In this case, the dialogue propels them into the action of rejecting their families’ wishes and puts them on the track that leads to their downfall.

Example #2

“Prophet!” said I, “thing of evil!—prophet still, if bird or devil!—

Whether Tempter sent, or whether tempest tossed thee here ashore,

Desolate yet all undaunted, on this desert land enchanted—

On this home by Horror haunted—tell me truly, I implore—

Is there—is there balm in Gilead?—tell me—tell me, I implore!”

Quoth the Raven “Nevermore.”

(“The Raven” by Edgar Allen Poe)

This is a dialogue example from a poem. In this case, the narrator of Edgar Allen Poe’s poem “The Raven” is going mad. A raven enters his library and does not leave him alone. The narrator tries to entreat the raven to leave him, but all the raven will answer him is with the word “nevermore.” This dialogue between a hallucinating man and his delusion makes his madness all the more obvious.

Example #3

‘The beer’s nice and cool,’ the man said.

‘It’s lovely,’ the girl said.

‘It’s really an awfully simple operation, Jig,’ the man said. ‘It’s not really an operation at all.’

The girl looked at the ground the table legs rested on.

‘I know you wouldn’t mind it, Jig. It’s really not anything. It’s just to let the air in.’

The girl did not say anything.

(“Hills Like White Elephants” by Ernest Hemingway)

Ernest Hemingway’s short story “Hills Like White Elephants” does not include much description or character development. The majority of the story is a dialogue between an unnamed man and girl. Hemingway makes nothing explicit in this dialogue, but instead relies on subtext and suggestion to show that the two characters are contemplating an abortion. Though it seems inane at times, the dialogue is actually extremely important, as it convinces the girl to go through with the operation.

Example #4

JIM: Aw, aw, aw. Is it broken?

LAURA: Now it is just like all the other horses.

JIM: It’s lost its—

LAURA: Horn! It doesn’t matter. . . . [smiling] I’ll just imagine he had an operation. The horn was removed to make him feel less—freakish!

(The Glass Menagerie by Tennessee Williams)

Tennessee Williams’s play The Glass Menagerie contains only four characters, and the way they talk to each other greatly effects their lives. The character of Jim comes to visit the Wingfield family. Unbeknownst to him, Laura Wingfield had always had a crush on him and hopes that his visit will save her from her loneliness. Jim accidentally knocks into Laura’s glass menagerie and breaks the horn off of her favorite animal, the unicorn. However, there is much symbolism in this action, as the dialogue between Laura and Jim makes Laura feel less “freakish,” just as her unicorn finally becomes normal.

Example #5

ROSENCRANTZ: What are you playing at?

GUILDENSTERN: Words, words. They’re all we have to go on.

(Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are Dead by Tom Stoppard)

Absurdist playwright Tom Stoppard wrote his play Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are Dead using two minor characters from William Shakespeare’s play Hamlet. The two characters share many bizarre exchanges throughout the play, but there is also much lucidity. In the above example of dialogue, Guildenstern notes that words are “all we have to go on.” Indeed, the play shows the importance of words and clear communication, and how lives can be lost when communication breaks down.

Test Your Knowledge of Dialogue

1. Which of the following statements is the best dialogue definition?

A. A short speech that a character makes in private.

B. A conversation between two or more characters.

C. An aside that a protagonist makes.

| Answer to Question #1 | Show |

|---|---|

2. Which of the following statements is true of dialogue examples?

A. They are a literary device used to reveal characters’ opinions and desires, and propel the narrative forward.

B. They have no effect on the action of a play or novel.

C. They cannot be found in poetry.

| Answer to Question #2 | Show |

|---|---|

3. Which of the following statements is false about examples of dialogues?

A. Dialogues have been used in philosophical treatises, peacekeeping negotiations, and comedy routines.

B. Dialogues are capable of affecting characters in both minor and profound ways.

C. Dialogues can only occur between two characters.

| Answer to Question #3 | Show |

|---|---|

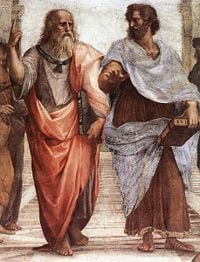

Detail of Plato in conversation at The School of Athens by Raphael

Dialogue (sometimes spelled dialog) is a reciprocal conversation between two or more entities. The etymological origins of the word (in Greek διά (diá,through) + λόγος (logos,word,speech) concepts like flowing-through meaning) do not necessarily convey the way in which people have come to use the word, with some confusion between the prefix διά-(diá-,through) and the prefix δι-(di-, two) leading to the assumption that a dialogue is necessarily between only two parties.

A dialogue as a form of communication has a verbal connotation. While communication can be an exchange of ideas and information by non-verbal signals, behaviors, as the etymology connotes, dialogue implies the use of language. A dialogue is distinguished from other communication methods such as discussions and debates. While debates are considered confrontational, dialogues emphasize listening and understanding. Martin Buber developed his philosophy on the dialogical nature of human existence and elaborated its implications in a broad range of subjects including religious consciousness, modernity, the concept of evil, ethics, education, spirituality, and Biblical hermeneutics.

Because dialogue is, for a human being, the fundamental form of communication and interaction, numerous texts from antiquity have used the structure of a dialogue as a literary form. Religious texts such as the Bible, Buddhist sutras, and Confucian texts and contemporary literature have used the form of a dialogue. In philosophy, Plato’s use of dialogue in his writings is often the best known.

Literary and philosophical genre

A dialogue is a fundamental and the most common form of communication for human beings. From religious texts in antiquity, including the Bible, Buddhist sutras, mythologies, to contemporary literature, a dialogue as a literary form has been widely used in diverse traditions.

Antiquity and the middle ages

In the east, the genre dates back to the Sumerian dialogues and disputations (preserved in copies from the early second millennium B.C.E.), as well as Rigvedic dialogue hymns and the Indian epic Mahabharata, while in the west, literary historians commonly suppose that Plato (c. 427 B.C.E.-c. 347 B.C.E.) introduced the systematic use of dialogue as an independent literary form: They point to his earliest experiment with the genre in the Laches. The Platonic dialogue, however, had its foundations in the mime, which the Sicilian poets Sophron and Epicharmus had cultivated half a century earlier. The works of these writers, which Plato admired and imitated, have not survived, but scholars imagine them as little plays usually presented with only two performers. The Mimes of Herodas gives some idea of their form.

Plato further simplified the form and reduced it to pure argumentative conversation, while leaving intact the amusing element of character-drawing. He must have begun this about the year 405 B.C.E., and by 399, he had fully developed his use of dialogue, especially in the cycle directly inspired by the death of Socrates. All his philosophical writings, except the Apology, use this form. As the greatest of all masters of Greek prose style, Plato lifted his favorite instrument, the dialogue, to its highest splendor, and to this day he remains by far its most distinguished proficient.

Following Plato, the dialogue became a major literary form in antiquity, and there are several examples both in Latin and Greek. Soon after Plato, Xenophon wrote his own Symposium, Aristotle is said to have written several philosophical dialogues in Plato’s style (none of which have survived), and later most of the Hellenistic schools had their own dialogue. Cicero wrote some very important works in this genre, such as Orator, Res Publica, and the lost Hortensius (the latter cited by Augustine in the Confessions as the work which instilled in him his lifelong love of philosophy).

In the second century C.E., Lucian of Samosata achieved a brilliant success with his ironic dialogues Of the Gods, Of the Dead, Of Love, and Of the Courtesans. In some of them, he attacks superstition and philosophical error with the sharpness of his wit; in others he merely paints scenes of modern life.

The dialogue was frequently used by early Christian writers, such as Justin, Origen and Augustine, and a particularly notable dialogue from late antiquity is Boethius’s Consolation of Philosophy. The genre survived up through the early scholastic period, with Peter Abelard composing his Dialogue with a Jew, a Christian and a Philosopher in the early twelfth century C.E., but later, in the wake of the powerful influence of writings by Bonaventure and Thomas Aquinas, the scholastic tradition adopted the more formal and concise genre of the summa, which largely superseded the dialogue as philosophical format.

The modern period to the present

Two French writers of eminence borrowed the title of Lucian’s most famous collection; both Fontenelle (1683) and Fénelon (1712) prepared Dialogues des morts («Dialogues of the Dead»). Contemporaneously, in 1688, the French philosopher Nicolas Malebranche published his Dialogues on Metaphysics and Religion, thus contributing to the genre’s revival in philosophic circles. In English non-dramatic literature the dialogue did not see extensive use until Berkeley used it in 1713, for his Platonic treatise, Three Dialogs between Hylas and Philonous. Landor’s Imaginary Conversations (1821-1828) formed the most famous English example of dialogue in the 19th century, although the dialogues of Sir Arthur Helps also claim attention.

In Germany, Wieland adopted this form for several important satirical works published between 1780 and 1799. In Spanish literature, the Dialogues of Valdés (1528) and those on Painting (1633) by Vincenzo Carducci are celebrated. Italian writers of collections of dialogues, following Plato’s model, include Torquato Tasso (1586), Galileo (1632), Galiani (1770), Leopardi (1825), and a host of others.

More recently, the French returned to the original application of dialogue. The inventions of «Gyp,» of Henri Lavedan, and of others, tell a mundane anecdote wittily and maliciously in conversation, would probably present a close analogy to the lost mimes of the early Sicilian poets. This kind of dialogue also appeared in English, exemplified by Anstey Guthrie, but these dialogues seem to have found less of a popular following among the English than their counterparts written by French authors.