«Forest clearing» redirects here. For a gap in a forest, see Glade (geography).

Annual change in forest area

Deforestation or forest clearance is the removal of a forest or stand of trees from land that is then converted to non-forest use.[3] Deforestation can involve conversion of forest land to farms, ranches, or urban use. The most concentrated deforestation occurs in tropical rainforests.[4] About 31% of Earth’s land surface is covered by forests at present.[5] This is one-third less than the forest cover before the expansion of agriculture, a half of that loss occurring in the last century.[6] Between 15 million to 18 million hectares of forest, an area the size of Bangladesh, are destroyed every year. On average 2,400 trees are cut down each minute.[7]

The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations defines deforestation as the conversion of forest to other land uses (regardless of whether it is human-induced). «Deforestation» and «forest area net change» are not the same: the latter is the sum of all forest losses (deforestation) and all forest gains (forest expansion) in a given period. Net change, therefore, can be positive or negative, depending on whether gains exceed losses, or vice versa.[8]

The removal of trees without sufficient reforestation has resulted in habitat damage, biodiversity loss, and aridity. Deforestation causes extinction, changes to climatic conditions, desertification, and displacement of populations, as observed by current conditions and in the past through the fossil record.[9] Deforestation also reduces biosequestration of atmospheric carbon dioxide, increasing negative feedback cycles contributing to global warming. Global warming also puts increased pressure on communities who seek food security by clearing forests for agricultural use and reducing arable land more generally. Deforested regions typically incur significant other environmental effects such as adverse soil erosion and degradation into wasteland.

The resilience of human food systems and their capacity to adapt to future change is linked to biodiversity – including dryland-adapted shrub and tree species that help combat desertification, forest-dwelling insects, bats and bird species that pollinate crops, trees with extensive root systems in mountain ecosystems that prevent soil erosion, and mangrove species that provide resilience against flooding in coastal areas.[10] With climate change exacerbating the risks to food systems, the role of forests in capturing and storing carbon and mitigating climate change is important for the agricultural sector.[10]

Recent history (1970 onwards)

For instance, FAO estimate that the global forest carbon stock has decreased 0.9%, and tree cover 4.2% between 1990 and 2020.[11] The forest carbon stock in Europe (including Russia) increased from 158.7 to 172.4 Gt between 1990 and 2020. In North America, the forest carbon stock increased from 136.6 to 140 Gt in the same period. However, carbon stock decreased from 94.3 to 80.9 Gt in Africa, 45.8 to 41.5 Gt in South and Southeast Asia combined, 33.4 to 33.1 Gt in Oceania, 5 to 4.1 Gt in Central America, and from 161.8 to 144.8 Gt in South America.[12] The IPCC (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change) states that there is disagreement about whether the global forest is shrinking or not, and quote research indicating that tree cover has increased 7.1% between 1982 and 2016.[a] IPCC also writes: «While above-ground biomass carbon stocks are estimated to be declining in the tropics, they are increasing globally due to increasing stocks in temperate and boreal forest.[13]

Agricultural expansion continues to be the main driver of deforestation and forest fragmentation and the associated loss of forest biodiversity.[10] Large-scale commercial agriculture (primarily cattle ranching and cultivation of soya bean and oil palm) accounted for 40 percent of tropical deforestation between 2000 and 2010, and local subsistence agriculture for another 33 percent.[10] Trees are cut down for use as building material, timber or sold as fuel (sometimes in the form of charcoal or timber), while cleared land is used as pasture for livestock and agricultural crops. The vast majority of agricultural activity resulting in deforestation is subsidized by government tax revenue.[14] Disregard of ascribed value, lax forest management, and deficient environmental laws are some of the factors that lead to large-scale deforestation. Deforestation in many countries—both naturally occurring[15] and human-induced—is an ongoing issue.[16] Between 2000 and 2012, 2.3 million square kilometres (890,000 sq mi) of forests around the world were cut down.[17] Deforestation and forest degradation continue to take place at alarming rates, which contributes significantly to the ongoing loss of biodiversity.[10]

The amount of globally needed agricultural land would be reduced by three quarters if the entire population adopted a vegan diet.[18]

Deforestation is more extreme in tropical and subtropical forests in emerging economies. More than half of all plant and land animal species in the world live in tropical forests.[19] As a result of deforestation, only 6.2 million square kilometres (2.4 million square miles) remain of the original 16 million square kilometres (6 million square miles) of tropical rainforest that formerly covered the Earth.[17] An area the size of a football pitch is cleared from the Amazon rainforest every minute, with 136 million acres (55 million hectares) of rainforest cleared for animal agriculture overall.[20] More than 3.6 million hectares of virgin tropical forest was lost in 2018.[21] Consumption and production of beef is the primary driver of deforestation in the Amazon, with around 80% of all converted land being used to rear cattle.[22][23] 91% of Amazon land deforested since 1970 has been converted to cattle ranching.[24][25] The global annual net loss of trees is estimated to be approximately 10 billion.[26][27] According to the Global Forest Resources Assessment 2020 the global average annual deforested land in the 2015–2020 demi-decade was 10 million hectares and the average annual forest area net loss in the 2000–2010 decade was 4.7 million hectares.[8] The world has lost 178 million ha of forest since 1990, which is an area about the size of Libya.[8]

According to a 2020 study published in Scientific Reports, if deforestation continues at current rates it can trigger a total or almost total extinction of humanity in the next 20 to 40 years. They conclude that «from a statistical point of view . . . the probability that our civilisation survives itself is less than 10% in the most optimistic scenario.» To avoid this collapse, humanity should pass from a civilization dominated by the economy to «cultural society» that «privileges the interest of the ecosystem above the individual interest of its components, but eventually in accordance with the overall communal interest.»[28][29]

In 2014, about 40 countries signed the New York Declaration on Forests, a voluntary pledge to halve deforestation by 2020 and end it by 2030. The agreement was not legally binding, however, and some key countries, such as Brazil, China, and Russia, did not sign onto it. As a result, the effort failed, and deforestation increased from 2014 to 2020.[30][31] In November 2021, 141 countries (with around 85% of the world’s primary tropical forests and 90% of global tree cover) agreed at the COP26 climate summit in Glasgow to the Glasgow Leaders’ Declaration on Forests and Land Use, a pledge to end and reverse deforestation by 2030.[31][32][33] The agreement was accompanied by about $19.2 billion in associated funding commitments.[32] The 2021 Glasgow agreement improved on the New York Declaration by now including Brazil and many other countries that did not sign the 2014 agreement.[31][32] Some key nations with high rates of deforestation (including Malaysia, Cambodia, Laos, Paraguay, and Myanmar) have not signed the Glasgow Declaration.[32] Like the earlier agreement, the Glasgow Leaders’ Declaration was entered into outside the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change and is thus not legally binding.[32] In November 2021, the EU executive outlined a draft law requiring companies to prove that the agricultural commodities beef, wood, palm oil, soy, coffee and cocoa destined for the EU’s 450 million consumers were not linked to deforestation.[34] In September 2022, the EU Parliament supported and strengthened the plan from the EU’s executive with 453 votes to 57.[35]

Causes

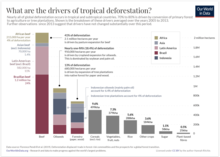

Drivers of deforestation and forest degradation by region, 2000–2010, from FAO publication The State of the World’s Forests 2020. Forests, biodiversity and people – In brief.[36]

Drivers of tropical deforestration

According to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) secretariat, the overwhelming direct cause of deforestation is agriculture. Subsistence farming is responsible for 48% of deforestation; commercial agriculture is responsible for 32%; logging is responsible for 14%, and fuel wood removals make up 5%.[37]

Experts do not agree on whether industrial logging is an important contributor to global deforestation.[38][39] Some argue that poor people are more likely to clear forest because they have no alternatives, others that the poor lack the ability to pay for the materials and labour needed to clear forest.[38]

Other causes of contemporary deforestation may include corruption of government institutions,[40][41][42] the inequitable distribution of wealth and power,[43] population growth[44] and overpopulation,[45][46] and urbanization.[47][48] The impact of population growth on deforestation has been contested. One study found that population increases due to high fertility rates were a primary driver of tropical deforestation in only 8% of cases.[49] In 2000 the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) found that «the role of population dynamics in a local setting may vary from decisive to negligible», and that deforestation can result from «a combination of population pressure and stagnating economic, social and technological conditions».[44]

Globalization is often viewed as another root cause of deforestation,[50][51] though there are cases in which the impacts of globalization (new flows of labor, capital, commodities, and ideas) have promoted localized forest recovery.[52]

Another cause of deforestation is climate change. 23% of tree cover losses result from wildfires and climate change increase their frequency and power.[53] The rising temperatures cause massive wildfires especially in the Boreal forests. One possible effect is the change of the forest composition.[54]Deforestation can also cause forests to become more fire prone through mechanisms such as logging[55]

Illegal gold mining in Madre de Dios, Peru.

The degradation of forest ecosystems has also been traced to economic incentives that make forest conversion appear more profitable than forest conservation.[56] Many important forest functions have no markets, and hence, no economic value that is readily apparent to the forests’ owners or the communities that rely on forests for their well-being.[56] From the perspective of the developing world, the benefits of forest as carbon sinks or biodiversity reserves go primarily to richer developed nations and there is insufficient compensation for these services. Developing countries feel that some countries in the developed world, such as the United States of America, cut down their forests centuries ago and benefited economically from this deforestation, and that it is hypocritical to deny developing countries the same opportunities, i.e. that the poor should not have to bear the cost of preservation when the rich created the problem.[57]

Some commentators have noted a shift in the drivers of deforestation over the past 30 years.[58] Whereas deforestation was primarily driven by subsistence activities and government-sponsored development projects like transmigration in countries like Indonesia and colonization in Latin America, India, Java, and so on, during the late 19th century and the earlier half of the 20th century, by the 1990s the majority of deforestation was caused by industrial factors, including extractive industries, large-scale cattle ranching, and extensive agriculture.[59] Since 2001, commodity-driven deforestation, which is more likely to be permanent, has accounted for about a quarter of all forest disturbance, and this loss has been concentrated in South America and Southeast Asia.[60]

Environmental effects

Atmospheric

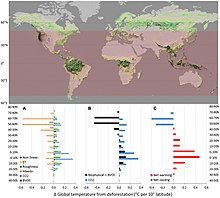

Biophysical mechanisms by which forests influence climate.[61]

Per capita CO2 emissions from deforestation for food production

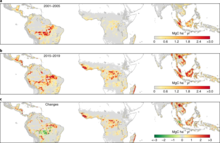

Mean annual carbon loss from tropical deforestation.[62]

Deforestation is ongoing and is shaping climate and geography.[63][64][65][66]

Deforestation is a contributor to global warming,[67][68][69] and is often cited as one of the major causes of the enhanced greenhouse effect. Recent calculations suggest that carbon dioxide emissions from deforestation and forest degradation (excluding peatland emissions) contribute about 12% of total anthropogenic carbon dioxide emissions with a range from 6% to 17%.[70] A 2022 study shows annual carbon emissions from tropical deforestation have doubled during the last two decades and continue to increase. (0.97 ±0.16 PgC per year in 2001–2005 to 1.99 ±0.13 PgC per year in 2015–2019)[71][62]

According to a review, north of 50°N, large scale deforestation leads to an overall net global cooling while tropical deforestation leads to substantial warming not just due to CO2-impacts but also due to other biophysical mechanisms (making carbon-centric metrics inadequate). Moreover, it suggests that standing tropical forests help cool the average global temperature by more than 1 °C.[72][61]

A study suggests logged and structurally degraded tropical forests are carbon sources for at least a decade – even when recovering[clarification needed] – due to larger carbon losses from soil organic matter and deadwood, indicating the tropical forest carbon sink (at least in South Asia) «may be much smaller than previously estimated», contradicting that «recovering logged and degraded tropical forests are net carbon sinks».[73]

Mechanisms

Deforestation causes carbon dioxide to linger in the atmosphere. As carbon dioxide accrues, it produces a layer in the atmosphere that traps radiation from the sun. The radiation converts to heat which causes global warming, which is better known as the greenhouse effect.[74] Plants remove carbon in the form of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere during the process of photosynthesis, but release some carbon dioxide back into the atmosphere during normal respiration. Only when actively growing can a tree or forest remove carbon, by storing it in plant tissues. Both the decay and the burning of wood release much of this stored carbon back into the atmosphere. Although an accumulation of wood is generally necessary for carbon sequestration, in some forests the network of symbiotic fungi that surround the trees’ roots can store a significant amount of carbon, storing it underground even if the tree which supplied it dies and decays, or is harvested and burned.[75] Another way carbon can be sequestered by forests is for the wood to be harvested and turned into long-lived products, with new young trees replacing them.[76] Deforestation may also cause carbon stores held in soil to be released. Forests can be either sinks or sources depending upon environmental circumstances. Mature forests alternate between being net sinks and net sources of carbon dioxide (see carbon dioxide sink and carbon cycle).

In deforested areas, the land heats up faster and reaches a higher temperature, leading to localized upward motions that enhance the formation of clouds and ultimately produce more rainfall.[77] However, according to the Geophysical Fluid Dynamics Laboratory, the models used to investigate remote responses to tropical deforestation showed a broad but mild temperature increase all through the tropical atmosphere. The model predicted <0.2 °C warming for upper air at 700 mb and 500 mb. However, the model shows no significant changes in other areas besides the Tropics. Though the model showed no significant changes to the climate in areas other than the Tropics, this may not be the case since the model has possible errors and the results are never absolutely definite.[78] Deforestation affects wind flows,

water vapour flows and absorption of solar energy thus clearly influencing local and global climate.[79]

REDD

Reducing emissions from deforestation and forest degradation (REDD) in developing countries has emerged as a new potential to complement ongoing climate policies. The idea consists in providing financial compensations for the reduction of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions from deforestation and forest degradation».[80] REDD can be seen as an alternative to the emissions trading system as in the latter, polluters must pay for permits for the right to emit certain pollutants (i.e. CO2).

Oxygen-supply misconception

Rainforests are widely believed by laymen to contribute a significant amount of the world’s oxygen,[81] although it is now accepted by scientists that rainforests contribute little net oxygen to the atmosphere and deforestation has only a minor effect on atmospheric oxygen levels.[82][83]In fact about 50 percent of oxygen on earth is produced by algae.[84] However, the incineration and burning of forest plants to clear land releases large amounts of CO2, which contributes to global warming.[68] Scientists also state that tropical deforestation releases 1.5 billion tons of carbon each year into the atmosphere.[85]

Hydrological

The water cycle is also affected by deforestation. Trees extract groundwater through their roots and release it into the atmosphere. When part of a forest is removed, the trees no longer transpire this water, resulting in a much drier climate. Deforestation reduces the content of water in the soil and groundwater as well as atmospheric moisture. The dry soil leads to lower water intake for the trees to extract.[86] Deforestation reduces soil cohesion, so that erosion, flooding and landslides ensue.[87][88]

Shrinking forest cover lessens the landscape’s capacity to intercept, retain and transpire precipitation. Instead of trapping precipitation, which then percolates to groundwater systems, deforested areas become sources of surface water runoff, which moves much faster than subsurface flows. Forests return most of the water that falls as precipitation to the atmosphere by transpiration. In contrast, when an area is deforested, almost all precipitation is lost as run-off.[89] That quicker transport of surface water can translate into flash flooding and more localized floods than would occur with the forest cover. Deforestation also contributes to decreased evapotranspiration, which lessens atmospheric moisture which in some cases affects precipitation levels downwind from the deforested area, as water is not recycled to downwind forests, but is lost in runoff and returns directly to the oceans. According to one study, in deforested north and northwest China, the average annual precipitation decreased by one third between the 1950s and the 1980s.[90]

Trees, and plants in general, affect the water cycle significantly:[91]

- their canopies intercept a proportion of precipitation, which is then evaporated back to the atmosphere (canopy interception);

- their litter, stems and trunks slow down surface runoff;

- their roots create macropores – large conduits – in the soil that increase infiltration of water;

- they contribute to terrestrial evaporation and reduce soil moisture via transpiration;

- their litter and other organic residue change soil properties that affect the capacity of soil to store water.

- their leaves control the humidity of the atmosphere by transpiring. 99% of the water absorbed by the roots moves up to the leaves and is transpired.[92]

As a result, the presence or absence of trees can change the quantity of water on the surface, in the soil or groundwater, or in the atmosphere. This in turn changes erosion rates and the availability of water for either ecosystem functions or human services. Deforestation on lowland plains moves cloud formation and rainfall to higher elevations.[93]

The forest may have little impact on flooding in the case of large rainfall events, which overwhelm the storage capacity of forest soil if the soils are at or close to saturation.

Tropical rainforests produce about 30% of our planet’s fresh water.[81]

Deforestation disrupts normal weather patterns creating hotter and drier weather thus increasing drought, desertification, crop failures, melting of the polar ice caps, coastal flooding and displacement of major vegetation regimes.[94]

Soil

Due to surface plant litter, forests that are undisturbed have a minimal rate of erosion. The rate of erosion occurs from deforestation, because it decreases the amount of litter cover, which provides protection from surface runoff.[95] The rate of erosion is around 2 metric tons per square kilometre.[96][self-published source?] This can be an advantage in excessively leached tropical rain forest soils. Forestry operations themselves also increase erosion through the development of (forest) roads and the use of mechanized equipment.

Deforestation in China’s Loess Plateau many years ago has led to soil erosion; this erosion has led to valleys opening up. The increase of soil in the runoff causes the Yellow River to flood and makes it yellow colored.[96]

Greater erosion is not always a consequence of deforestation, as observed in the southwestern regions of the US. In these areas, the loss of grass due to the presence of trees and other shrubbery leads to more erosion than when trees are removed.[96]

Soils are reinforced by the presence of trees, which secure the soil by binding their roots to soil bedrock. Due to deforestation, the removal of trees causes sloped lands to be more susceptible to landslides.[91]

Biodiversity

Deforestation on a human scale results in decline in biodiversity,[97] and on a natural global scale is known to cause the extinction of many species.[9][98] The removal or destruction of areas of forest cover has resulted in a degraded environment with reduced biodiversity.[46] Forests support biodiversity, providing habitat for wildlife;[99] moreover, forests foster medicinal conservation.[100] With forest biotopes being irreplaceable source of new drugs (such as taxol), deforestation can destroy genetic variations (such as crop resistance) irretrievably.[101]

Since the tropical rainforests are the most diverse ecosystems on Earth[102][103] and about 80% of the world’s known biodiversity can be found in tropical rainforests,[104][105] removal or destruction of significant areas of forest cover has resulted in a degraded[106] environment with reduced biodiversity.[9][107] A study in Rondônia, Brazil, has shown that deforestation also removes the microbial community which is involved in the recycling of nutrients, the production of clean water and the removal of pollutants.[108]

It has been estimated that we are losing 137 plant, animal and insect species every single day due to rainforest deforestation, which equates to 50,000 species a year.[109] Others state that tropical rainforest deforestation is contributing to the ongoing Holocene mass extinction.[110][111] The known extinction rates from deforestation rates are very low, approximately 1 species per year from mammals and birds, which extrapolates to approximately 23,000 species per year for all species. Predictions have been made that more than 40% of the animal and plant species in Southeast Asia could be wiped out in the 21st century.[112] Such predictions were called into question by 1995 data that show that within regions of Southeast Asia much of the original forest has been converted to monospecific plantations, but that potentially endangered species are few and tree flora remains widespread and stable.[113]

Scientific understanding of the process of extinction is insufficient to accurately make predictions about the impact of deforestation on biodiversity.[114] Most predictions of forestry related biodiversity loss are based on species-area models, with an underlying assumption that as the forest declines species diversity will decline similarly.[115] However, many such models have been proven to be wrong and loss of habitat does not necessarily lead to large scale loss of species.[115] Species-area models are known to overpredict the number of species known to be threatened in areas where actual deforestation is ongoing, and greatly overpredict the number of threatened species that are widespread.[113]

In 2012, a study of the Brazilian Amazon predicts that despite a lack of extinctions thus far, up to 90 percent of predicted extinctions will finally occur in the next 40 years.[116]

Health effects

Public health context

The degradation and loss of forests disrupts nature’s balance.[10] Indeed, deforestation eliminates a great number of species of plants and animals which also often results in an increase in disease,[117] and exposure of people to zoonotic diseases.[10][118][119][120] Deforestation can also create a path for non-native species to flourish such as certain types of snails, which have been correlated with an increase in schistosomiasis cases.[117][121]

Forest-associated diseases include malaria, Chagas disease (also known as American trypanosomiasis), African trypanosomiasis (sleeping sickness), leishmaniasis, Lyme disease, HIV and Ebola.[10] The majority of new infectious diseases affecting humans, including the SARS-CoV2 virus that caused the current COVID-19 pandemic, are zoonotic and their emergence may be linked to habitat loss due to forest area change and the expansion of human populations into forest areas, which both increase human exposure to wildlife.[10]

Deforestation is occurring all over the world and has been coupled with an increase in the occurrence of disease outbreaks. In Malaysia, thousands of acres of forest have been cleared for pig farms. This has resulted in an increase in the zoonosis the Nipah virus.[122] In Kenya, deforestation has led to an increase in malaria cases which is now the leading cause of morbidity and mortality the country.[123][124] A 2017 study in the American Economic Review found that deforestation substantially increased the incidence of malaria in Nigeria.[125]

Another pathway through which deforestation affects disease is the relocation and dispersion of disease-carrying hosts. This disease emergence pathway can be called «range expansion», whereby the host’s range (and thereby the range of pathogens) expands to new geographic areas.[126] Through deforestation, hosts and reservoir species are forced into neighboring habitats. Accompanying the reservoir species are pathogens that have the ability to find new hosts in previously unexposed regions. As these pathogens and species come into closer contact with humans, they are infected both directly and indirectly.

A catastrophic example of range expansion is the 1998 outbreak of Nipah virus in Malaysia.[127] For a number of years, deforestation, drought, and subsequent fires led to a dramatic geographic shift and density of fruit bats, a reservoir for Nipah virus.[128] Deforestation reduced the available fruiting trees in the bats’ habitat, and they encroached on surrounding orchards which also happened to be the location of a large number of pigsties. The bats, through proximity spread the Nipah to pigs. While the virus infected the pigs, mortality was much lower than among humans, making the pigs a virulent host leading to the transmission of the virus to humans. This resulted in 265 reported cases of encephalitis, of which 105 resulted in death. This example provides an important lesson for the impact deforestation can have on human health.

Another example of range expansion due to deforestation and other anthropogenic habitat impacts includes the Capybara rodent in Paraguay.[129] This rodent is the host of a number of zoonotic diseases and, while there has not yet been a human-borne outbreak due to the movement of this rodent into new regions, it offers an example of how habitat destruction through deforestation and subsequent movements of species is occurring regularly.

A now well-developed and widely accepted theory is that the spillover of HIV from chimpanzees was at least partially due to deforestation. Rising populations created a food demand, and with deforestation opening up new areas of the forest, hunters harvested a great deal of primate bushmeat, which is believed to be the origin of HIV.[117]

Research in Indonesia has found that outdoor workers who worked in tropical and deforested instead of tropical and naturally forested areas experienced cognitive and memory impairments which appear to be caused primarily by exposure to high heat which trees would have protected them from.[130] Deforestation reduces safe working hours for millions of people in the tropics, especially for those performing heavy labour outdoors. Continued global heating and forest loss is expected to amplify these impacts, reducing work hours for vulnerable groups even more.[131]

General overview

According to the World Economic Forum, 31% of emerging diseases are linked to deforestation.[132]

According to the US Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), 75% of emerging diseases in humans came from animals. The rising number of outbreaks is probably linked to habitat and biodiversity loss. In response, scientists created a new discipline, planetary health, which posits that the health of the ecosystems and the health of humans are linked.[133] In 2015, the Rockefeller Foundation and The Lancet launched the concept as the Rockefeller Foundation–Lancet Commission on Planetary Health.[134]

Since the 1980s, every decade has seen the number of new diseases in humans increase more than threefold. According to a major study by American and Australian scientists, degradation of ecosystems increases the risk of new outbreaks. The diseases that passed to humans in this way in the latest decades include HIV, Ebola, Avian flu, Swine Flu, and likely COVID-19.[135]

In 2016, the United Nations Environment Programme published the UNEP Frontiers 2016 Report. In this report, the second chapter was dedicated to zoonotic diseases, that is diseases that pass from animals to humans. This chapter stated that deforestation, climate change, and livestock agriculture are among the main causes that increase the risk of such diseases. It mentioned that every four months, a new disease is discovered in humans. It is said that outbreaks that already happened (as of 2016) led to loss of lives and financial losses of billions dollars and if future diseases become pandemics it will cost trillions of dollars.[136]

The report presents the causes of the emerging diseases, a large part of them environmental:

| Cause | Part of emerging diseases caused by it (%) |

|---|---|

| Land-use change | 31% |

| Agricultural industry changes | 15% |

| International travel and commerce | 13% |

| Medical industry changes | 11% |

| War and Famine | 7% |

| Climate and Weather | 6% |

| Human demography and behavior | 4% |

| Breakdown of public health | 3% |

| Bushmeat | 3% |

| Food industry change | 2% |

| Other | 4%[136] |

On page 23 of the report are presented some of the latest emerging diseases and the definite environmental cause of them:

| Disease | Environmental cause |

|---|---|

| Rabies | Forest activities in South America |

| Bat associated viruses | Deforestation and Agricultural expansion |

| Lyme disease | Forest fragmentation in North America |

| Nipah virus infection | Pig farming and intensification of fruit production in Malaysia |

| Japanese encephalitis virus | Irrigated rice production and pig farming in Southeast Asia |

| Ebola virus disease | Forest losses |

| Avian influenza | Intensive Poultry farming |

| SARS virus | contact with civet cats either in the wild or in live animal markets[136] |

HIV/AIDS

Further information: AIDS

AIDS is probably linked to deforestation.[137] The virus firstly circulated among monkeys and apes and when the humans came and destroyed the forest and most of the primates, the virus needed a new host to survive and jumped to humans.[138] The virus, which killed more than 25 million people, is believed to have come from the consumption of bushmeat, namely that of primates, and most likely chimpanzees in the Congo.[139][140][141]

Malaria

Malaria, which killed 405,000 people in 2018,[142] is probably linked to deforestation. When humans change dramatically the ecological system the diversity in mosquito species is reduced and: «»The species that survive and become dominant, for reasons that are not well understood, almost always transmit malaria better than the species that had been most abundant in the intact forests», write Eric Chivian and Aaron Bernstein, public health experts at Harvard Medical School, in their book How Our Health Depends on Biodiversity. «This has been observed essentially everywhere malaria occurs».

Some of the reasons for this connection, found by scientists in the latest years:

- When there is less shadow of the trees, the temperature of the water is higher which benefits mosquitos.

- When the trees don’t consume water, there is more water on the ground, which also benefits mosquitos.

- Low lying vegetation is better for the species of mosquitos that transmit the disease.

- When there is no forest there is less tannin in water. Than the water is less acidic and more turbid, what is better for some species of mosquitos.

- The mosquitos that live in deforested areas are better at carrying malaria.

- Another reason is that when a large part of a forest is destroyed, the animals are crowded in the remaining fragments in higher density, which facilitate the spread of the virus between them. This leads to a bigger number of cases between animals which increase the likelihood of transmission to humans.

Consequently, the same type of mosquito bites 278 times more often in deforested areas. According to one study in Brazil, cutting of 4% of the forest, led to a 50% increase in Malaria cases. In one region in Peru the number of cases per year, jumped from 600 to 120,000 after people begun to cut forests.[139]

Coronavirus disease 2019

According to the United Nations, World Health Organization and World Wildlife Foundation the Coronavirus pandemic is linked to the destruction of nature, especially to deforestation, habitat loss in general and wildlife trade.[143]

In April 2020, United Nations Environment Programme published 2 short videos explaining the link between nature destruction, wildlife trade and the COVID-19 pandemic[144][145] and created a section on its site dedicated to the issue.[146]

The World Economic Forum published a call to involve nature recovery in the recovery efforts from the COVID-19 pandemic saying that this outbreak is linked to the destruction of the natural world.[147]

In May 2020, a group of experts from the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services published an article saying that humans are the species responsible for the COVID-19 pandemic because it is linked to nature destruction and more severe epidemics might occur if humanity will not change direction. It calls to «strengthen environmental regulations; adopt a ‘One Health’ approach to decision-making that recognizes complex interconnections among the health of people, animals, plants, and our shared environment; and prop up health care systems in the most vulnerable countries where resources are strained and underfunded», which can prevent future epidemics and therefore is in the interest of all. The call was published on the site of the World Economic Forum.[148]

According to the United Nations Environment Programme the Coronavirus disease 2019 is zoonotic, e.g., the virus passed from animals to humans. Such diseases are occurring more frequently in the latest decades, due to a number of factors, a large part of them environmental. One of the factors is deforestation because it reduce the space reserved for animals and destroys natural barriers between animals and humans. Another cause is climate change. Too fast changes in temperature and humidity facilitate the spread of diseases. The United Nations Environment Programme concludes that: «The most fundamental way to protect ourselves from zoonotic diseases is to prevent destruction of nature. Where ecosystems are healthy and biodiverse, they are resilient, adaptable and help to regulate diseases.[149]

In June 2020, a scientific unit of Greenpeace with University of the West of England (UWE Bristol) published a report saying that the rise of zoonotic diseases, including coronavirus is directly linked to deforestation because it change the interaction between people and animals and reduce the amount of water necessary for hygiene and diseases treatment.[150][151]

Experts say that anthropogenic deforestation, habitat loss and destruction of biodiversity may be linked to outbreaks like the COVID-19 pandemic in several ways:

- Bringing people and domestic animals in contact with a species of animals and plants that were not contacted by them before. Kate Jones, chair of ecology and biodiversity at University College London, says the disruption of pristine forests, driven by logging, mining, road building through remote places, rapid urbanisation and population growth is bringing people into closer contact with animal species they may never have been near before, resulting in transmission of new zoonotic diseases from wildlife to humans.

- Creating degraded habitats. Such habitats with a few species are more likely to cause a transmission of zoonotic viruses to humans.

- Creating more crowded habitats, with more dense population.

- Habitat loss prompts animals to search for a new one, which often results in mixing with humans and other animals.

- Disruption of ecosystems can increase the number of animals that carry many viruses, like bats and rodents. It can increase the number of mice and rats by reducing the populations of predators. Deforestation in the Amazon rainforest increases the likelihood of malaria because the deforested area is ideal for mosquitoes.[147]

- Animal trade, by killing and transporting live and dead animals very long distances. According to American science journalist David Quammen, «We cut the trees; we kill the animals or cage them and send them to markets. We disrupt ecosystems, and we shake viruses loose from their natural hosts. When that happens, they need a new host. Often, we are it.»[133][135]

When climate change or deforestation causes a virus to pass to another host it becomes more dangerous. This is because viruses generally learn to coexist with their host and become virulent when they pass to another.[152]

Economic impact

|

|

This section needs to be updated. The reason given is: cites are very old. Please help update this article to reflect recent events or newly available information. (June 2020) |

According to the World Economic Forum, half of the global GDP is strongly or moderately dependent on nature. For every dollar spent on nature restoration, there is a profit of at least 9 dollars. Example of this link is the COVID-19 pandemic, which is linked to nature destruction and caused severe economic damage.[147]

Damage to forests and other aspects of nature could halve living standards for the world’s poor and reduce global GDP by about 7% by 2050, a report concluded at the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) meeting in Bonn in 2008.[153] Historically, utilization of forest products, including timber and fuel wood, has played a key role in human societies, comparable to the roles of water and cultivable land. Today, developed countries continue to utilize timber for building houses, and wood pulp for paper. In developing countries, almost three billion people rely on wood for heating and cooking.[154]

The forest products industry is a large part of the economy in both developed and developing countries. Short-term economic gains made by conversion of forest to agriculture, or over-exploitation of wood products, typically leads to a loss of long-term income and long-term biological productivity. West Africa, Madagascar, Southeast Asia and many other regions have experienced lower revenue because of declining timber harvests. Illegal logging causes billions of dollars of losses to national economies annually.[155]

The new procedures to get amounts of wood are causing more harm to the economy and overpower the amount of money spent by people employed in logging.[156] According to a study, «in most areas studied, the various ventures that prompted deforestation rarely generated more than US$5 for every ton of carbon they released and frequently returned far less than US$1». The price on the European market for an offset tied to a one-ton reduction in carbon is 23 euro (about US$35).[157]

Rapidly growing economies also have an effect on deforestation. Most pressure will come from the world’s developing countries, which have the fastest-growing populations and most rapid economic (industrial) growth.[158] In 1995, economic growth in developing countries reached nearly 6%, compared with the 2% growth rate for developed countries.[158] As our human population grows, new homes, communities, and expansions of cities will occur. Connecting all of the new expansions will be roads, a very important part in our daily life. Rural roads promote economic development but also facilitate deforestation.[158] About 90% of the deforestation has occurred within 100 km of roads in most parts of the Amazon.[159]

The European Union is one of the largest importer of products made from illegal deforestation.[160]

Forest transition theory

The forest area change may follow a pattern suggested by the forest transition (FT) theory,[161] whereby at early stages in its development a country is characterized by high forest cover and low deforestation rates (HFLD countries).[59]

Then deforestation rates accelerate (HFHD, high forest cover – high deforestation rate), and forest cover is reduced (LFHD, low forest cover – high deforestation rate), before the deforestation rate slows (LFLD, low forest cover – low deforestation rate), after which forest cover stabilizes and eventually starts recovering. FT is not a «law of nature», and the pattern is influenced by national context (for example, human population density, stage of development, structure of the economy), global economic forces, and government policies. A country may reach very low levels of forest cover before it stabilizes, or it might through good policies be able to «bridge» the forest transition.[citation needed]

FT depicts a broad trend, and an extrapolation of historical rates therefore tends to underestimate future BAU deforestation for countries in the early stages of the transition (HFLD), while it tends to overestimate BAU deforestation for countries in the later stages (LFHD and LFLD).

Countries with high forest cover can be expected to be at early stages of the FT. GDP per capita captures the stage in a country’s economic development, which is linked to the pattern of natural resource use, including forests. The choice of forest cover and GDP per capita also fits well with the two key scenarios in the FT:

(i) a forest scarcity path, where forest scarcity triggers forces (for example, higher prices of forest products) that lead to forest cover stabilization; and

(ii) an economic development path, where new and better off-farm employment opportunities associated with economic growth (= increasing GDP per capita) reduce the profitability of frontier agriculture and slows deforestation.[59]

Historical causes

Prehistory

The Carboniferous Rainforest Collapse[9] was an event that occurred 300 million years ago. Climate change devastated tropical rainforests causing the extinction of many plant and animal species. The change was abrupt, specifically, at this time climate became cooler and drier, conditions that are not favorable to the growth of rainforests and much of the biodiversity within them. Rainforests were fragmented forming shrinking ‘islands’ further and further apart. Populations such as the sub class Lissamphibia were devastated, whereas Reptilia survived the collapse. The surviving organisms were better adapted to the drier environment left behind and served as legacies in succession after the collapse.[162][self-published source?]

An array of Neolithic artifacts, including bracelets, ax heads, chisels, and polishing tools.

Rainforests once covered 14% of the earth’s land surface; now they cover a mere 6% and experts estimate that the last remaining rainforests could be consumed in less than 40 years.[163]

Small scale deforestation was practiced by some societies for tens of thousands of years before the beginnings of civilization.[164] The first evidence of deforestation appears in the Mesolithic period.[165] It was probably used to convert closed forests into more open ecosystems favourable to game animals.[164] With the advent of agriculture, larger areas began to be deforested, and fire became the prime tool to clear land for crops. In Europe there is little solid evidence before 7000 BC. Mesolithic foragers used fire to create openings for red deer and wild boar. In Great Britain, shade-tolerant species such as oak and ash are replaced in the pollen record by hazels, brambles, grasses and nettles. Removal of the forests led to decreased transpiration, resulting in the formation of upland peat bogs. Widespread decrease in elm pollen across Europe between 8400 and 8300 BC and 7200–7000 BC, starting in southern Europe and gradually moving north to Great Britain, may represent land clearing by fire at the onset of Neolithic agriculture.

The Neolithic period saw extensive deforestation for farming land.[166][167] Stone axes were being made from about 3000 BC not just from flint, but from a wide variety of hard rocks from across Britain and North America as well. They include the noted Langdale axe industry in the English Lake District, quarries developed at Penmaenmawr in North Wales and numerous other locations. Rough-outs were made locally near the quarries, and some were polished locally to give a fine finish. This step not only increased the mechanical strength of the axe, but also made penetration of wood easier. Flint was still used from sources such as Grimes Graves but from many other mines across Europe.

Evidence of deforestation has been found in Minoan Crete; for example the environs of the Palace of Knossos were severely deforested in the Bronze Age.[168]

Pre-industrial history

Easter Island, deforested. According to Jared Diamond: «Among past societies faced with the prospect of ruinous deforestation, Easter Island and Mangareva chiefs succumbed to their immediate concerns, but Tokugawa shoguns, Inca emperors, New Guinea highlanders, and 16th century German landowners adopted a long view and reafforested.»[169]

Just as archaeologists have shown that prehistoric farming societies had to cut or burn forests before planting, documents and artifacts from early civilizations often reveal histories of deforestation. Some of the most dramatic are eighth century BCE Assyrian reliefs depicting logs being floated downstream from conquered areas to the less forested capital region as spoils of war. Ancient Chinese texts make clear that some areas of the Yellow River valley had already destroyed many of their forests over 2000 years ago and had to plant trees as crops or import them from long distances.[170] In South China much of the land came to be privately owned and used for the commercial growing of timber.[171]

Three regional studies of historic erosion and alluviation in ancient Greece found that, wherever adequate evidence exists, a major phase of erosion follows the introduction of farming in the various regions of Greece by about 500–1,000 years, ranging from the later Neolithic to the Early Bronze Age.[172] The thousand years following the mid-first millennium BC saw serious, intermittent pulses of soil erosion in numerous places. The historic silting of ports along the southern coasts of Asia Minor (e.g. Clarus, and the examples of Ephesus, Priene and Miletus, where harbors had to be abandoned because of the silt deposited by the Meander) and in coastal Syria during the last centuries BC.[173][174]

Easter Island has suffered from heavy soil erosion in recent centuries, aggravated by agriculture and deforestation.[175] Jared Diamond gives an extensive look into the collapse of the ancient Easter Islanders in his book Collapse. The disappearance of the island’s trees seems to coincide with a decline of its civilization around the 17th and 18th century. He attributed the collapse to deforestation and over-exploitation of all resources.[176][177]

The famous silting up of the harbor for Bruges, which moved port commerce to Antwerp, also followed a period of increased settlement growth (and apparently of deforestation) in the upper river basins. In early medieval Riez in upper Provence, alluvial silt from two small rivers raised the riverbeds and widened the floodplain, which slowly buried the Roman settlement in alluvium and gradually moved new construction to higher ground; concurrently the headwater valleys above Riez were being opened to pasturage.[178]

A typical progress trap was that cities were often built in a forested area, which would provide wood for some industry (for example, construction, shipbuilding, pottery). When deforestation occurs without proper replanting, however; local wood supplies become difficult to obtain near enough to remain competitive, leading to the city’s abandonment, as happened repeatedly in Ancient Asia Minor. Because of fuel needs, mining and metallurgy often led to deforestation and city abandonment.[179]

With most of the population remaining active in (or indirectly dependent on) the agricultural sector, the main pressure in most areas remained land clearing for crop and cattle farming. Enough wild green was usually left standing (and partially used, for example, to collect firewood, timber and fruits, or to graze pigs) for wildlife to remain viable. The elite’s (nobility and higher clergy) protection of their own hunting privileges and game often protected significant woodland.[180]

Major parts in the spread (and thus more durable growth) of the population were played by monastical ‘pioneering’ (especially by the Benedictine and Commercial orders) and some feudal lords’ recruiting farmers to settle (and become tax payers) by offering relatively good legal and fiscal conditions. Even when speculators sought to encourage towns, settlers needed an agricultural belt around or sometimes within defensive walls. When populations were quickly decreased by causes such as the Black Death, the colonization of the Americas,[181] or devastating warfare (for example, Genghis Khan’s Mongol hordes in eastern and central Europe, Thirty Years’ War in Germany), this could lead to settlements being abandoned. The land was reclaimed by nature, but the secondary forests usually lacked the original biodiversity. The Mongol invasions and conquests alone resulted in the reduction of 700 million tons of carbon from the atmosphere by enabling the re-growth of carbon-absorbing forests on depopulated lands over a significant period of time.[182][183]

From 1100 to 1500 AD, significant deforestation took place in Western Europe as a result of the expanding human population.[184] The large-scale building of wooden sailing ships by European (coastal) naval owners since the 15th century for exploration, colonisation, slave trade, and other trade on the high seas, consumed many forest resources and became responsible for the introduction of numerous bubonic plague outbreaks in the 14th century. Piracy also contributed to the over harvesting of forests, as in Spain. This led to a weakening of the domestic economy after Columbus’ discovery of America, as the economy became dependent on colonial activities (plundering, mining, cattle, plantations, trade, etc.)[185]

In Changes in the Land (1983), William Cronon analyzed and documented 17th-century English colonists’ reports of increased seasonal flooding in New England during the period when new settlers initially cleared the forests for agriculture. They believed flooding was linked to widespread forest clearing upstream.

The massive use of charcoal on an industrial scale in Early Modern Europe was a new type of consumption of western forests; even in Stuart England, the relatively primitive production of charcoal has already reached an impressive level. Stuart England was so widely deforested that it depended on the Baltic trade for ship timbers, and looked to the untapped forests of New England to supply the need. Each of Nelson’s Royal Navy war ships at Trafalgar (1805) required 6,000 mature oaks for its construction. In France, Colbert planted oak forests to supply the French navy in the future. When the oak plantations matured in the mid-19th century, the masts were no longer required because shipping had changed.

Norman F. Cantor’s summary of the effects of late medieval deforestation applies equally well to Early Modern Europe:[186]

Europeans had lived in the midst of vast forests throughout the earlier medieval centuries. After 1250 they became so skilled at deforestation that by 1500 they were running short of wood for heating and cooking. They were faced with a nutritional decline because of the elimination of the generous supply of wild game that had inhabited the now-disappearing forests, which throughout medieval times had provided the staple of their carnivorous high-protein diet. By 1500 Europe was on the edge of a fuel and nutritional disaster [from] which it was saved in the sixteenth century only by the burning of soft coal and the cultivation of potatoes and maize.

In folk culture

Different cultures of different places in the world have different interpretations of the actions of the cutting down of trees.

Meitei culture

In Meitei mythology and Meitei folklore of Manipur, deforestation is mentioned as one of the reasons to make mother nature (most probably goddess Leimarel Sidabi) weep and mourn for the death of her precious children.

In an ancient Meitei language narrative poem named the «Hijan Hirao» (Old Manipuri: «Hichan Hilao»), it is mentioned that King Hongnem Luwang Ningthou Punsiba of Luwang dynasty once ordered his men for the cutting down of woods in the forest for crafting out a beautiful royal Hiyang Hiren. His servants spotted on a gigantic tree growing on the slope of a mountain and by the side of a river.

They performed traditional customary rites and rituals before chopping off the woods on the next day.

In the middle of the night, Mother nature started weeping in the fear of losing her child, the tree.[187][188][189]

Her agony is described as follows:

At dead of night

The mother who begot the tree

And the mother of all giant trees,

The queen of the hill-range

And the mistress of the gorges

Took the tall and graceful tree

To her bosom and wailed:

«O my son, tall and big,

While yet an infant, a sapling

Didn’t I tell you

To be an ordinary tree?

The king’s men have found you out

And bought your life with gold and silver.

* *

At daybreak, hacked at the trunk

You will be found lying prostrate.

No longer will you respond

To your mother’s call

Nor a likeness of you

Shall be found, when I survey

The whole hillside.Who shall now relieve my grief?»

— Hijan Hirao[190][191][192]

Industrial era

Tropical deforestation, 1700–2004 (percent loss)[193]

In the 19th century, introduction of steamboats in the United States was the cause of deforestation of banks of major rivers, such as the Mississippi River, with increased and more severe flooding one of the environmental results. The steamboat crews cut wood every day from the riverbanks to fuel the steam engines. Between St. Louis and the confluence with the Ohio River to the south, the Mississippi became more wide and shallow, and changed its channel laterally. Attempts to improve navigation by the use of snag pullers often resulted in crews’ clearing large trees 100 to 200 feet (61 m) back from the banks. Several French colonial towns of the Illinois Country, such as Kaskaskia, Cahokia and St. Philippe, Illinois, were flooded and abandoned in the late 19th century, with a loss to the cultural record of their archeology.[194]

The wholesale clearance of woodland to create agricultural land can be seen in many parts of the world, such as the Central forest-grasslands transition and other areas of the Great Plains of the United States. Specific parallels are seen in the 20th-century deforestation occurring in many developing nations.

Rates of deforestation

Estimates vary widely as to the extent of tropical deforestation.[195][196]

Present-day

In 2019, the world lost nearly 12 million hectares of tree cover. Nearly a third of that loss, 3.8 million hectares, occurred within humid tropical primary forests, areas of mature rainforest that are especially important for biodiversity and carbon storage. That’s the equivalent of losing an area of primary forest the size of a football pitch every six seconds.[197][198]

History

Global deforestation[199] sharply accelerated around 1852.[200][201] As of 1947, the planet had 15 million to 16 million km2 (5.8 million to 6.2 million sq mi) of mature tropical forests,[202] but by 2015, it was estimated that about half of these had been destroyed.[203][19][204] Total land coverage by tropical rainforests decreased from 14% to 6%. Much of this loss happened between 1960 and 1990, when 20% of all tropical rainforests were destroyed. At this rate, extinction of such forests is projected to occur by the mid-21st century.[162]

In the early 2000s, some scientists predicted that unless significant measures (such as seeking out and protecting old growth forests that have not been disturbed)[202] are taken on a worldwide basis, by 2030 there will only be 10% remaining,[200][204] with another 10% in a degraded condition.[200] 80% will have been lost, and with them hundreds of thousands of irreplaceable species.[200]

Rates of change

Annual forest area net change, by decade and region, 1990–2020.[205]

Global annual forest area net change, by decade, 1990–2020[206]

The rate of global tree cover loss has approximately doubled since 2001, to an annual loss approaching an area the size of Italy.[207]

A 2002 analysis of satellite imagery suggested that the rate of deforestation in the humid tropics (approximately 5.8 million hectares per year) was roughly 23% lower than the most commonly quoted rates.[208] A 2005 report by the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) estimated that although the Earth’s total forest area continued to decrease at about 13 million hectares per year, the global rate of deforestation had been slowing.[209][210] On the other hand, a 2005 analysis of satellite images reveals that deforestation of the Amazon rainforest is twice as fast as scientists previously estimated.[211][212]

From 2010 to 2015, worldwide forest area decreased by 3.3 million ha per year, according to FAO. During this five-year period, the biggest forest area loss occurred in the tropics, particularly in South America and Africa. Per capita forest area decline was also greatest in the tropics and subtropics but is occurring in every climatic domain (except in the temperate) as populations increase.[213]

An estimated 420 million ha of forest has been lost worldwide through deforestation since 1990, but the rate of forest loss has declined substantially. In the most recent five-year period (2015–2020), the annual rate of deforestation was estimated at 10 million ha, down from 12 million ha in 2010–2015.[8]

Loss of primary (old-growth) forest in the tropics has continued its upward trend, with fire-related losses contributing an increasing portion.[214]

Overall, 20% of the Amazon rainforest has been «transformed» (deforested) and another 6% has been «highly degraded», causing Amazon Watch to warn that the Amazonia is in the midst of a tipping point crisis.[215]

Africa had the largest annual rate of net forest loss in 2010–2020, at 3.9 million ha, followed by South America, at 2.6 million ha. The rate of net forest loss has increased in Africa in each of the three decades since 1990. It has declined substantially in South America, however, to about half the rate in 2010–2020 compared with 2000–2010. Asia had the highest net gain of forest area in 2010–2020, followed by Oceania and Europe. Nevertheless, both Europe and Asia recorded substantially lower rates of net gain in 2010–2020 than in 2000–2010. Oceania experienced net losses of forest area in the decades 1990–2000 and 2000–2010.[8]

Some claim that rainforests are being destroyed at an ever-quickening pace.[216] The London-based Rainforest Foundation notes that «the UN figure is based on a definition of forest as being an area with as little as 10% actual tree cover, which would therefore include areas that are actually savanna-like ecosystems and badly damaged forests».[217] Other critics of the FAO data point out that they do not distinguish between forest types,[218] and that they are based largely on reporting from forestry departments of individual countries,[219] which do not take into account unofficial activities like illegal logging.[220] Despite these uncertainties, there is agreement that destruction of rainforests remains a significant environmental problem.

Methods of analysis

Some have argued that deforestation trends may follow a Kuznets curve,[221] which if true would nonetheless fail to eliminate the risk of irreversible loss of non-economic forest values (for example, the extinction of species).[222][223]

Some cartographers have attempted to illustrate the sheer scale of deforestation by country using a cartogram.[224]

Deforestation around Pakke Tiger Reserve, India

Regions

Rates of deforestation vary around the world.

Up to 90% of West Africa’s coastal rainforests have disappeared since 1900.[225] Madagascar has lost 90% of its eastern rainforests.[226][227]

In South Asia, about 88% of the rainforests have been lost.[228]

Mexico, India, the Philippines, Indonesia, Thailand, Burma, Malaysia, Bangladesh, China, Sri Lanka, Laos, Nigeria, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Liberia, Guinea, Ghana and the Ivory Coast, have lost large areas of their rainforest.[229][230]

Much of what remains of the world’s rainforests is in the Amazon basin, where the Amazon Rainforest covers approximately 4 million square kilometres.[231] Some 80% of the deforestation of the Amazon can be attributed to cattle ranching,[232] as Brazil is the largest exporter of beef in the world.[233] The Amazon region has become one of the largest cattle ranching territories in the world.[234] The regions with the highest tropical deforestation rate between 2000 and 2005 were Central America—which lost 1.3% of its forests each year—and tropical Asia.[217] In Central America, two-thirds of lowland tropical forests have been turned into pasture since 1950 and 40% of all the rainforests have been lost in the last 40 years.[235] Brazil has lost 90–95% of its Mata Atlântica forest.[236] Deforestation in Brazil increased by 88% for the month of June 2019, as compared with the previous year.[237] However, Brazil still destroyed 1.3 million hectares in 2019.[197] Brazil is one of several countries that have declared their deforestation a national emergency.[238][239]

Paraguay was losing its natural semi-humid forests in the country’s western regions at a rate of 15,000 hectares at a randomly studied 2-month period in 2010.[240] In 2009, Paraguay’s parliament refused to pass a law that would have stopped cutting of natural forests altogether.[241]

As of 2007, less than 50% of Haiti’s forests remained.[242]

The World Wildlife Fund’s ecoregion project catalogues habitat types throughout the world, including habitat loss such as deforestation, showing for example that even in the rich forests of parts of Canada such as the Mid-Continental Canadian forests of the prairie provinces half of the forest cover has been lost or altered.

In 2011 Conservation International listed the top 10 most endangered forests, characterized by having all lost 90% or more of their original habitat, and each harboring at least 1500 endemic plant species (species found nowhere else in the world).[243]

-

Top 10 Most Endangered Forests 2011

Endangered forest Region Remaining habitat Predominate vegetation type Notes Indo-Burma Asia-Pacific 5% Tropical and subtropical moist broadleaf forests Rivers, floodplain wetlands, mangrove forests. Burma, Thailand, Laos, Vietnam, Cambodia, India.[244] New Caledonia Asia-Pacific 5% Tropical and subtropical moist broadleaf forests See note for region covered.[245] Sundaland Asia-Pacific 7% Tropical and subtropical moist broadleaf forests Western half of the Indo-Malayan archipelago including southern Borneo and Sumatra.[246] Philippines Asia-Pacific 7% Tropical and subtropical moist broadleaf forests Forests over the entire country including 7,100 islands.[247] Atlantic Forest South America 8% Tropical and subtropical moist broadleaf forests Forests along Brazil’s Atlantic coast, extends to parts of Paraguay, Argentina and Uruguay.[248] Mountains of Southwest China Asia-Pacific 8% Temperate coniferous forest See note for region covered.[249] California Floristic Province North America 10% Tropical and subtropical dry broadleaf forests See note for region covered.[250] Coastal Forests of Eastern Africa Africa 10% Tropical and subtropical moist broadleaf forests Mozambique, Tanzania, Kenya, Somalia.[251] Madagascar & Indian Ocean Islands Africa 10% Tropical and subtropical moist broadleaf forests Madagascar, Mauritius, Reunion, Seychelles, Comoros.[252] Eastern Afromontane Africa 11% Tropical and subtropical moist broadleaf forests

Montane grasslands and shrublandsForests scattered along the eastern edge of Africa, from Saudi Arabia in the north to Zimbabwe in the south.[253]

-

- Table source:[243]

Control

Reducing emissions

Main international organizations including the United Nations and the World Bank, have begun to develop programs aimed at curbing deforestation. The blanket term Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation (REDD) describes these sorts of programs, which use direct monetary or other incentives to encourage developing countries to limit and/or roll back deforestation. Funding has been an issue, but at the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) Conference of the Parties-15 (COP-15) in Copenhagen in December 2009, an accord was reached with a collective commitment by developed countries for new and additional resources, including forestry and investments through international institutions, that will approach US$30 billion for the period 2010–2012.[254]

Significant work is underway on tools for use in monitoring developing countries’ adherence to their agreed REDD targets. These tools, which rely on remote forest monitoring using satellite imagery and other data sources, include the Center for Global Development’s FORMA (Forest Monitoring for Action) initiative[255] and the Group on Earth Observations’ Forest Carbon Tracking Portal.[256] Methodological guidance for forest monitoring was also emphasized at COP-15.[257] The environmental organization Avoided Deforestation Partners leads the campaign for development of REDD through funding from the U.S. government.[258] In 2014, the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations and partners launched Open Foris – a set of open-source software tools that assist countries in gathering, producing and disseminating information on the state of forest resources.[259] The tools support the inventory lifecycle, from needs assessment, design, planning, field data collection and management, estimation analysis, and dissemination. Remote sensing image processing tools are included, as well as tools for international reporting for Reducing emissions from deforestation and forest degradation (REDD) and MRV (Measurement, Reporting and Verification)[260] and FAO’s Global Forest Resource Assessments.

In evaluating implications of overall emissions reductions, countries of greatest concern are those categorized as High Forest Cover with High Rates of Deforestation (HFHD) and Low Forest Cover with High Rates of Deforestation (LFHD). Afghanistan, Benin, Botswana, Burma, Burundi, Cameroon, Chad, Ecuador, El Salvador, Ethiopia, Ghana, Guatemala, Guinea, Haiti, Honduras, Indonesia, Liberia, Malawi, Mali, Mauritania, Mongolia, Namibia, Nepal, Nicaragua, Niger, Nigeria, Pakistan, Paraguay, the Philippines, Senegal, Sierra Leone, Sri Lanka, Sudan, Togo, Uganda, United Republic of Tanzania, and Zimbabwe are listed as having Low Forest Cover with High Rates of Deforestation (LFHD). Brazil, Cambodia, Democratic People’s Republic of Korea, Equatorial Guinea, Malaysia, Solomon Islands, Timor-Leste, Venezuela, and Zambia are listed as having High Forest Cover with High Rates of Deforestation (HFHD).[261]

Control can be made by the companies.[262] In 2018 the biggest palm oil trader, Wilmar, decided to control its suppliers to avoid deforestation. This is an important precedent.[263][additional citation(s) needed]

In 2021, over 100 world leaders, representing countries containing more than 85% of the world’s forests, committed to halt and reverse deforestation and land degradation by 2030.[264]

Payments for conserving forests

In Bolivia, deforestation in upper river basins has caused environmental problems, including soil erosion and declining water quality. An innovative project to try and remedy this situation involves landholders in upstream areas being paid by downstream water users to conserve forests. The landholders receive US$20 to conserve the trees, avoid polluting livestock practices, and enhance the biodiversity and forest carbon on their land. They also receive US$30, which purchases a beehive, to compensate for conservation for two hectares of water-sustaining forest for five years. Honey revenue per hectare of forest is US$5 per year, so within five years, the landholder has sold US$50 of honey.[265] The project is being conducted by Fundación Natura Bolivia and Rare Conservation, with support from the Climate & Development Knowledge Network.

International, national and subnational policies

An incomplete concept of a framework of policy mix sequencing for zero-deforestation governance. Non-intervention in processes related to beef production via policies may be a main driver of tropical deforestation.

Policies for forest protection include information and education programs, economic measures to increase revenue returns from authorized activities and measures to increase effectiveness of «forest technicians and forest managers».[266] Poverty and agricultural rent were found to be principal factors leading to deforestation.[267] Contemporary domestic and foreign political decision-makers could possibly create and implement policies whose outcomes ensure that economic activities in critical forests are consistent with their scientifically ascribed value for ecosystem services, climate change mitigation and other purposes.

Such policies may use and organize the development of complementary technical and economic means – including for lower levels of beef production, sales and consumption (which would also have major benefits for climate change mitigation),[268][269] higher levels of specified other economic activities in such areas (such as reforestation, forest protection, sustainable agriculture for specific classes of food products and quaternary work in general), product information requirements, practice- and product-certifications and eco-tariffs, along with the required monitoring and traceability. Inducing the creation and enforcement of such policies could, for instance, achieve a global phase-out of deforestation-associated beef.[270][271][272][additional citation(s) needed] With complex polycentric governance measures, goals like sufficient climate change mitigation as decided with e.g. the Paris Agreement and a stoppage of deforestation by 2030 as decided at the 2021 United Nations Climate Change Conference could be achieved.[273] A study has suggested higher income nations need to reduce imports of tropical forest-related products and help with theoretically forest-related socioeconomic development. Proactive government policies and international forest policies «revisit[ing] and redesign[ing] global forest trade» are needed as well.[274][275]

In 2022 the European parliament approved a very important bill aiming to stop the import linked with deforestation. The bill requires from companies who want to import 14 products: soy, beef, palm oil, timber, cocoa, coffee, pork, lamb, goat meat, poultry, maize, rubber, charcoal, and printed paper to the European Union to prove the production of those commodities is not linked to areas deforested after 31 of December 2019. Without it the import will be forbidden. The bill may cause to Brazil, for example, to stop deforestation for agricultural production and begun to «increase productivity on existing agricultural land».[276]

Technology

|

This section is empty. You can help by adding to it. (May 2021) |

Land rights

Transferring land rights to indigenous inhabitants is argued to efficiently conserve forests.

Indigenous communities have long been the frontline of resistance against deforestation.[277] Transferring rights over land from public domain to its indigenous inhabitants is argued to be a cost-effective strategy to conserve forests.[278] This includes the protection of such rights entitled in existing laws, such as India’s Forest Rights Act.[278] The transferring of such rights in China, perhaps the largest land reform in modern times, has been argued to have increased forest cover.[279] In Brazil, forested areas given tenure to indigenous groups have even lower rates of clearing than national parks.[279]

Community concessions in the Congolian rainforests have significantly less deforestation as communities are incentivized to manage the land sustainably, even reducing poverty.[280]

Farming

New methods are being developed to farm more intensively, such as high-yield hybrid crops, greenhouses, vertical farming, autonomous building gardens, and hydroponics. These methods are often dependent on chemical inputs to maintain necessary yields. In cyclic agriculture, cattle are grazed on farm land that is resting and rejuvenating. Cyclic agriculture actually increases the fertility of the soil. Intensive farming can also decrease soil nutrients by consuming the trace minerals needed for crop growth at an accelerated rate.[162] The most promising approach, however, is the concept of food forests in permaculture, which consists of agroforestal systems carefully designed to mimic natural forests, with an emphasis on plant and animal species of interest for food, timber and other uses. These systems have low dependence on fossil fuels and agro-chemicals, are highly self-maintaining, highly productive, and with strong positive impact on soil and water quality, and biodiversity.

Also, due to the environmental impact of meat production and milk production, production of meat analogues and milk substitutes (fermentation, single-cell protein, …) is being explored. This may or may not effect the economics of cattle farming as well (along with soy production and exports, as a portion of it is used as fodder for cattle).

Monitoring deforestation

There are multiple methods that are appropriate and reliable for reducing and monitoring deforestation. One method is the «visual interpretation of aerial photos or satellite imagery that is labor-intensive but does not require high-level training in computer image processing or extensive computational resources».[159] Another method includes hot-spot analysis (that is, locations of rapid change) using expert opinion or coarse resolution satellite data to identify locations for detailed digital analysis with high resolution satellite images.[159] Deforestation is typically assessed by quantifying the amount of area deforested, measured at the present time.

From an environmental point of view, quantifying the damage and its possible consequences is a more important task, while conservation efforts are more focused on forested land protection and development of land-use alternatives to avoid continued deforestation.[159] Deforestation rate and total area deforested have been widely used for monitoring deforestation in many regions, including the Brazilian Amazon deforestation monitoring by INPE.[85] A global satellite view is available, an example of land change science monitoring of land cover over time.[281][282]

Satellite imaging has become crucial in obtaining data on levels of deforestation and reforestation. Landsat satellite data, for example, has been used to map tropical deforestation as part of NASA’s Landsat Pathfinder Humid Tropical Deforestation Project. The project yielded deforestation maps for the Amazon Basin, Central Africa, and Southeast Asia for three periods in the 1970s, 1980s, and 1990s.[283]

Forest management