If you’ve been teaching reading for a while, you’ve undoubtedly come across the term sight words, and you probably have some questions about them. Should you teach sight words? What’s the best way to approach sight words? Is it bad to use a curriculum that teaches sight words?

In fact, a common question we get is, “Do you teach sight words in the All About Reading program? ” But before we jump into the details, let’s be sure we’re talking about the same definition for the term sight words.

Our Working Definition of Sight Word

At its most basic–and this is what we mean when we talk about sight words–a sight word is a word that can be read instantly, without conscious attention.

For example, if you see the word peanut and recognize it instantly, peanut is a sight word for you. You just see the word and can read it right away without having to sound it out. In fact, if you are a fluent reader, chances are you don’t need to stop to decode words as you read this blog post because every word in this post is a sight word for you.

But there are three other commonly used definitions for sight words that you should be aware of:

- Irregular words that can’t be decoded using phonics and must be memorized, such as of, could, and said.

- The “whole word” or “look-say” approach to teaching reading, also known as the “sight word approach.” This approach is the opposite of phonics, and words are memorized as a whole.

- Words that appear on high-frequency word lists such as the popular Dolch Sight Word and Fry’s Instant Word lists. (Many educators believe that the words on these lists must be learned through rote memorization, but we bust that myth in this video.)

So now you can see why sight words can cause so much angst! Educators have conflicting ideas about sight words and how to teach them, and in large part that stems from having different definitions for what sight words are.

But you are in safe territory here.

In this article, you’ll find out how to minimize the number of sight words that your child needs to memorize, while maximizing his ability to successfully master these words.

How Fast Is “Instant”?

Now that we’ve settled on the definition for sight words as “any words that can be read instantly, without conscious attention,” that may lead some people to wonder how fast is “instant”? And that’s a great question!

Basically, we want kids to see a word and be unable to not read it. Even before they’ve realized that they are looking at the word, they’ve unconsciously read it.

Here’s a demonstration of what I mean.

(Download this PDF if you want to try this experiment with your family and friends!)

As explained in the short video above, the Stroop effect1 shows that word recognition can be even more automatic than something as basic as color recognition.

So that’s what we mean by “instant.”

We want children to develop automaticity when reading, so they don’t even have to think about decoding words—they just automatically know the words. Ideally, we want reading to become as effortless and unconscious as breathing.

But what about words that aren’t as easily decoded? How should those words be taught?

Some Words Need to Be Learned Through Rote Memorization

The vast majority of words don’t need to be taught by rote memorization. Even the Dolch Sight Word list is mostly decodable (video). But there are some words that do need to be memorized.

Some programs call these “Red Words,” “Outlaw Words,” “Sight Words,” or “Watch-Out” words. In All About Reading, we call them Leap Words. Generally, these are high-frequency words that either don’t follow the normal phonetic patterns or contain phonograms that students haven’t practiced yet. Students “leap ahead” to learn these words as sight words.

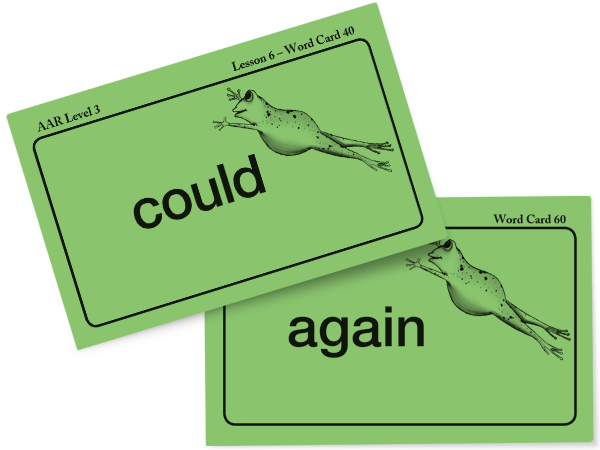

Here’s an example of two flashcards used to practice the Leap Words could and again. In the word could, the L isn’t pronounced. In the word again, the AI says /ĕ/, which isn’t one of its typical sounds. The frog graphic acts as a visual reminder that the words are being treated as sight words that need to be memorized.

Leap Words comprise a small percentage of words taught. For example, out of the 200 words taught in All About Reading Level 1, only 11 are Leap Words.

Several techniques are used to help your student remember the Leap Words:

- Leap Word Cards are kept behind the Review divider in your student’s Reading Review Box until your student has achieved instant recognition of the word.

- Leap Words frequently appear on the Practice Sheets.

- Leap Words are used frequently in the decodable readers.

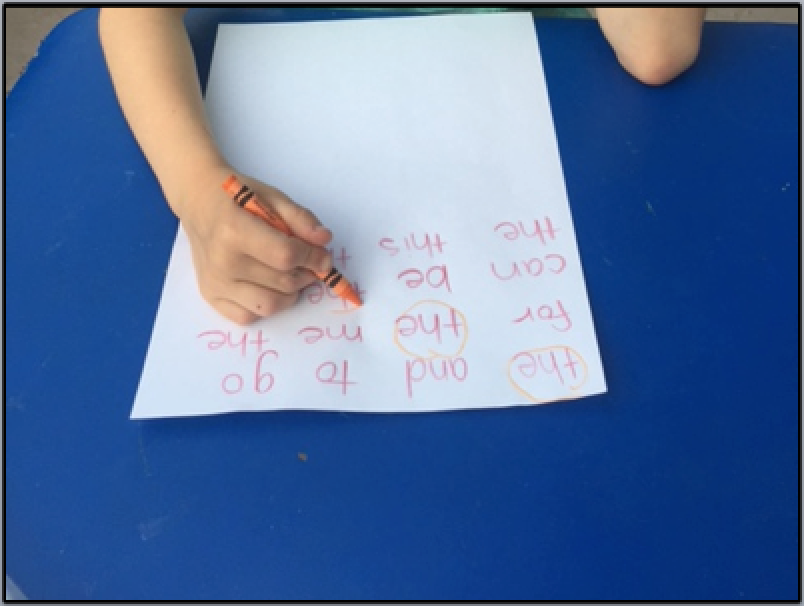

- If a Leap Word causes your student trouble, have your student use a light-colored crayon to circle the part of the word that doesn’t say what your student expects it to say.

- Help your student see that Leap Words generally have just one or two letters that are troublesome, while the rest of the letters say their regular sounds and follow normal patterns.

For typical students who do not struggle with reading, very little practice is needed to move a word into long-term memory. They may encounter the word just one to five times, and never have to sound it out again.

On the other hand, a struggling reader may need up to thirty exposures to a word before it becomes part of the child’s sight word vocabulary. So be patient and give your child the amount of practice she needs to develop a large sight word vocabulary.

Here Are 5 More Ways to Increase Your Child’s Sight Word Vocabulary

These five methods increase the number of times your child encounters a word, helping move the word into long-term memory for instant recall:

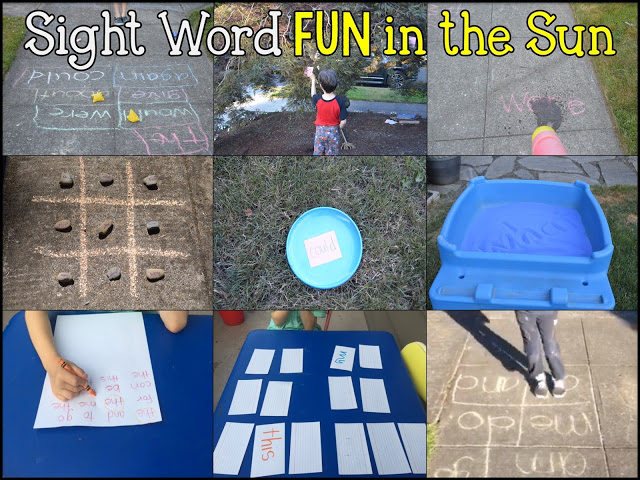

- Make use of interesting games and activities (such as Over Easy, Hatch the Turtles, and Pack Your Suitcase).

- Have your child read decodable books.

- Encourage your child to “sound out” phonetically-regular words.

- Use sentence dictation to encourage extra practice.

- Review Word Cards frequently until they are mastered.

The Bottom Line on Teaching Sight Words

When it comes to teaching sight words, here’s what you need to keep in mind:

- The goal of teaching sight words is to allow your child to read easily and fluently, without conscious attention.

- Some words—we call them Leap Words—can’t be decoded as easily and must be learned through rote memorization.

- Increasing the number of times a child encounters a word helps move the word into the child’s long-term memory.

Are you looking for a reading program that doesn’t involve memorizing hundreds of sight words via rote memorization? All About Reading is a research-based program that walks you through all the steps to help your child achieve instant recall. And if you ever need a hand, we’re here to help.

What’s your take on teaching sight words? Have anything else to share? Let me know in the comments below!

___________________________________

1Stroop, J.R. (1935). Studies of interference in serial verbal reactions. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 18, 643-662.

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

High frequency sight words (also known simply as sight words) are commonly used words that young children are encouraged to memorize as a whole by sight, so that they can automatically recognize these words in print without having to use any strategies to decode.[1] Sight words were introduced after whole language (a similar method) fell out of favor with the education establishment.[2]

The term sight words is often confused with sight vocabulary, which is defined as each person’s own vocabulary that the person recognizes from memory without the need to decode for understanding.[3][1]

However, some researchers say that two of the most significant problems with sight words are: (1) memorizing sight words is labour intensive, requiring on average about 35 trials per word,[4] and (2) teachers who withhold phonics instruction and instead rely on teaching sight words are making it harder for children to «gain basic word-recognition skills» that are critically needed by the end of grade three and can be used over a lifetime of reading.[5]

Rationale[edit]

Sight words account for a large percentage (up to 75%) of the words used in beginning children’s print materials.[6][7] The advantage for children being able to recognize sight words automatically is that a beginning reader will be able to identify the majority of words in a beginning text before they even attempt to read it; therefore, allowing the child to concentrate on meaning and comprehension as they read without having to stop and decode every single word.[6] Advocates of whole-word instruction believe that being able to recognize a large number of sight words gives students a better start to learning to read.

Recognizing sight words automatically is said to be advantageous for beginning readers because many of these words have unusual spelling patterns, cannot be sounded out using basic phonics knowledge and cannot be represented using pictures.[8] For example, the word «was» does not follow a usual spelling pattern, as the middle letter «a» makes an /ɒ~ʌ/ sound and the final letter «s» makes a /z/ sound, nor can the word be associated with a picture clue since it denotes an abstract state (existence). Another example, is the word «said», it breaks the phonetic rule of ai normally makes the long a sound, ay. In this word it makes the short e sound of eh.[9] The word «said» is pronounced as /s/ /e/ /d/. The word «has» also breaks the phonetic rule of s normally making the sss sound, in this word the s makes the z sound, /z/.» The word is then pronounced /h/ /a/ /z/.[9]

However, a 2017 study in England compared teaching with phonics vs. teaching whole written words and concluded that phonics is more effective, saying «our findings suggest that interventions aiming to improve the accuracy of reading aloud and/or comprehension in the early stages of learning should focus on the systematicities present in print-to-sound relationships, rather than attempting to teach direct access to the meanings of whole written words».[10]

Most advocates of sight-words believe children should memorize the words. However, some educators say a more efficient method is to teach them by using an explicit phonics approach, perhaps by using a tool such as Elkonin boxes. As a result, the words form part of the students sight vocabulary, are readily accessible and aid in learning other words containing similar sounds.[11][12]

Other phonics advocates, such as the Common Core State Standards Initiative (CCSSI-USA), the Departments of Education in England, and the State of Victoria in Australia, recommend that teachers first begin by teaching children the frequent sounds and the simple spellings, then introduce the less frequent sounds and more complex spellings later (e.g. the sounds /s/ and /t/ before /v/ and /w/; and the spellings cake before eight and cat before duck).[13][14][15][16] The following are samples of the lists that are available on the CCSSI-USA site:[17]

| Phoneme | Sample only — Word Examples (Consonants) (CCSSI-USA) | Common Graphemes (Spellings) |

|---|---|---|

| /m/ | mitt, comb, hymn | m, mb, mn |

| /t/ | tickle, mitt, sipped | t, tt, ed |

| /n/ | nice, knight, gnat | n, kn, gn |

| /k/ | cup, kite, duck, chorus, folk, quiet | k, c, ck, ch, lk, q |

| /f/ | fluff, sphere, tough, calf | f, ff, gh, ph, lf |

| /s/ | sit, pass, science, psychic | s, ss, sc, ps |

| /z/ | zoo, jazz, nose, as, xylophone | z, zz, se, s, x |

| /sh/ | shoe, mission, sure, charade, precious, notion, mission, special | sh, ss, s, ch, sc, ti, si, ci |

| /zh/ | measure, azure | s, z |

| /r/ | reach, wrap, her, fur, stir | r, wr, er/ur/ir |

| /h/ | house, whole | h, wh |

| Phoneme | Sample only — Word Examples (Vowels) (CCSSI-USA) | Common Graphemes (Spellings) |

|---|---|---|

| /ā/ | make, rain, play, great, baby, eight, vein, they | a_e, ai, ay, ea, -y, eigh, ei, ey |

| /ē/ | see, these, me, eat, key, happy, chief, either | ee, e_e, -e, ea, ey, -y, ie, ei |

| /ī/ | time, pie, cry, right, rifle | i_e, ie, -y, igh, -I |

| /ō/ | vote, boat, toe, snow, open | o_e, oa, oe, ow, o- |

| /ū/ | use, few, cute | u, ew, u_e |

| /ă/ | cat | a |

| /ĕ/ | bed, breath | e, ea |

| /ĭ/ | sit, gym | i, y |

| /ŏ/ | fox, swap, palm | o, (w)a, al |

| /ŭ/ | cup, cover, flood, tough | u, o, oo, ou |

| /aw/ | saw, pause, call, water, bought | aw, au, al, (w)a, ough |

| /er/ | her, fur, sir | er, ur, ir |

Word lists[edit]

A number of sight word lists have been compiled and published; among the most popular are the Dolch sight words[18] (first published in 1936) and the 1000 Instant Word list prepared in 1979 by Edward Fry, professor of Education and Director of the Reading Center at Rutgers University and Loyola University in Los Angeles.[19][20][21][22] Many commercial products are also available. These lists have similar attributes, as they all aim to divide words into levels which are prioritized and introduced to children according to frequency of appearance in beginning readers’ texts. Although many of the lists have overlapping content, the order of frequency of sight words varies and can be disputed, as they depend on contexts such as geographical location, empirical data, samples used, and year of publication.[23]

Criticism[edit]

Research shows that the alphabetic principle is seen as «the primary driver» of development of all aspects of printed word recognition including phonic rules and sight vocabulary.»[24] In addition, the use of sight words as a reading instructional strategy is not consistent with the dual route theory as it involves out-of-context memorization rather than the development of phonological skills.[25] Instead, it is suggested that children first learn to identify individual letter-sound correspondences before blending and segmenting letter combinations.[26][27]

Proponents of systematic phonics and synthetic phonics argue that children must first learn to associate the sounds of their language with the letter(s) that are used to represent them, and then to blends those sounds into words, and that children should never memorize words as visual designs.[28] Using sight words as a method of teaching reading in English is seen as being at odds with the alphabetic principle and treating English as though it was a logographic language (e.g. Chinese or Japanese).[29]

Some notable researchers have clearly stated their disapproval of whole language and whole-word teaching. In his 2009 book, Reading in the brain, French cognitive neuroscientist Stanislas Dehaene wrote, «cognitive psychology directly refutes any notion of teaching via a ‘global’ or ‘whole language’ method.» He goes on to talk about «the myth of whole-word reading», saying it has been refuted by recent experiments. «We do not recognize a printed word through a holistic grasping of its contours, because our brain breaks it down into letters and graphemes.»[30] Another cognitive neuroscientist, Mark Seidenberg, says that learning to sound-out atypical words such as have (/h/-/a/-/v/) helps the student to read other words such as had, has, having, hive, haven’t, etc. because of the sounds they have in common.[31]

See also[edit]

- Dolch word list

- Dual-route hypothesis to reading aloud

- Fry readability formula

- Learning to read

- Literacy

- Most common words in English

- Phonics

- Reading comprehension

- Reading education in the United States

- Reading (process)

- Subvocalization

- Teaching reading: whole language and phonics

- Whole language

- Writing system

References[edit]

- ^ a b «What Are Sight Words?». WeAreTeachers. 2018-04-25. Retrieved 2018-11-30.

- ^ Ravitch, Diane. (2007). EdSpeak: A Glossary of Education Terms, Phrases, Buzzwords, and Jargon. Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision & Curriculum Development, ISBN 1416605754.

- ^ Rapp, S. (1999-09-29). Recognizing words on sight; activity. The Baltimore Sun

- ^ Murray, Bruce; McIlwain, Jane (2019). «How do beginners learn to read irregular words as sight words». Journal of Research in Reading. 42 (1): 123–136. doi:10.1111/1467-9817.12250. ISSN 0141-0423. S2CID 150055551.

- ^ Seidenberg, Mark (2017). Language at the speed of sight. New York, NY: Basic Books. p. 147. ISBN 978-1-5416-1715-5.

- ^ a b Kear, D. J., & Gladhart, M. A. (1983). «Comparative Study to Identify High-Frequency Words in Printed Materials». Perceptual and Motor Skills. 57 (3): 807–810. doi:10.2466/pms.1983.57.3.807. S2CID 144675331.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ «Teaching Sight Words as a Part of Comprehensive Reading Instruction, Iowa reading research centre, 2018-06-12».

- ^ «Phonological Ability», The SAGE Encyclopedia of Contemporary Early Childhood Education, SAGE Publications, Inc, 2016, doi:10.4135/9781483340333.n296, ISBN 9781483340357

- ^ a b «Sight Words». www.thephonicspage.org. Retrieved 2018-11-30.

- ^ Taylor, J. S. H.; Davis, Matthew H.; Rastle, Kathleen (2017). «Comparing and Validating Methods of Reading Instruction Using Behavioural and Neural Findings in an Artificial Orthography» (PDF). Journal of Experimental Psychology: General. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, volume 146, No. 6, 826–858. 146 (6): 826–858. doi:10.1037/xge0000301. PMC 5458780. PMID 28425742.

- ^ «Sight Words: An Evidence-Based Literacy Strategy, Understood.org».

- ^ «A New Model for Teaching High-Frequency Words, reading rockets.org». 6 June 2019.

- ^ «Complete report — National Reading Panel, England» (PDF).

- ^ «Sample phonics lessons, The State Government of Victoria».

- ^ «Foundation skills, The State Government of Victoria, AU».

- ^ «English Appendix 1: Spelling, Government of England» (PDF).

- ^ «Common Core Standards, Appendix A, USA» (PDF).

- ^ «Dolch Words 220, Utah Education Network in partnership with the Utah State Board of Education and Utah System of Higher Education» (PDF).

- ^ Edward Fry (1979). 1000 Instant Words: The Most Common Words for Teaching Reading, Writing, and Spelling. ISBN 0809208806.

- ^ «McGraw-Hill Education Acknowledges Enduring Contributions of Reading and Language Arts Scholar, Author and Innovator Ed Fry, McGraw-Hill Education, Sep 15, 2010».

- ^ «Edward B. Fry, PH.D, Published in Los Angeles Times on Sep. 12, 2010». Legacy.com.

- ^ «Fry Instant Words, UTAH EDUCATION NETWORK».

- ^ Otto, W. & cester, R. (1972). «Sight words for beginning readers». The Journal of Educational Research. 65 (10): 435–443. doi:10.1080/00220671.1972.10884372. JSTOR /27536333.

- ^ «Independent Review of the Primary Curriculum: Final Report, page 87» (PDF).

- ^ Ehri, Linnea C. (2017). «Reconceptualizing the Development of Sight Word Reading and Its Relationship to Recoding». Reading Acquisition. London: Routledge. pp. 107–143. ISBN 9781351236898.

- ^ Literacy teaching guide : phonics. New South Wales. Department of Education and Training. [Sydney, N.S.W.]: New South Wales Dept. of Education and Training. 2009. ISBN 9780731386093. OCLC 590631697.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Findings and Determinations of the National Reading Panel by Topic Areas

- ^ McGuinness, Diane (1997). Why Our Children Can’t Read. New York, NY: The Free Press. ISBN 0684831619.

- ^ Gatto, John Taylor (2006). «Eyless in Gaza». The Underground History of American Education. Oxford, NY: The Oxford Village Press. pp. 70–72. ISBN 0945700040.

- ^ Stanislas Dehaene (2010-10-26). Reading in the brain. Penquin Books. pp. 222–228. ISBN 9780143118053.

- ^ Seidenberg, Mark (2017). Language at the speed of light. pp. 143–144=author=Mark Seidenberg. ISBN 9780465080656.

When you’re a new teacher, the number of buzzwords that you have to master seems overwhelming at times. You’ve probably heard about many concepts, but you may not be entirely sure what they are or how to use them in your classroom. For example, new teacher Katy B. asks, “This seems like a really basic question, but what are sight words, and where do I find them?” No worries, Katy. We have you covered!

What’s the difference between sight words and high-frequency words?

Oftentimes we use the terms sight words and high-frequency words interchangeably. Opinions differ, but our research shows that there is a difference. High-frequency words are words that are most commonly found in written language. Although some fit standard phonetic patterns, some do not. Sight words are a subset of high-frequency words that do not fit standard phonetic patterns and are therefore not easily decoded.

We use both types of words consistently in spoken and written language, and they also appear in books, including textbooks, and stories. Once students learn to quickly recognize these words, reading comes more easily.

What are sight words and how can I teach my students to memorize them?

Sight words are words like come, does, or who that do not follow the rules of spelling or the six types of syllables. Decoding these words can be very difficult for young learners. The common practice has been to teach students to memorize these words as a whole, by sight, so that they can recognize them immediately (within three seconds) and read them without having to use decoding skills.

Can I teach sight words using the science of reading?

On the other hand, recent findings based on the science of reading suggests we can use strategies beyond rote memorization. According to the the science of reading, it is possible to sound out many sight words because they have recognizable patterns. Literacy specialist Susan Jones, a proponent of using the science of reading to teach sight words, recommends a method called phoneme-grapheme mapping where students first map out the sounds they hear in a word and then add graphemes (letters) they hear for each sound.

How else can I teach sight words?

There are many fun and engaging ways to teach sight words. Dozens of books on the subject have been published, including the much-revered Comprehensive Phonics, Spelling, and Word Study Guide by Fountas & Pinnell. Also, resources like games, manipulatives, and flash cards are readily available online and in stores. To help get you started, check out these Creative and Simple Sight Word Activities for the Classroom. Also, check out Susan Jones Teaching for three science-of-reading-based ideas and more.

Where do I find sight word lists?

Two of the most popular sources are the Dolch High Frequency Words list and the Fry High Frequency Words list.

During the 1930s and 1940s, Dr. Edward Dolch developed his word list, used for pre-K through third grade, by studying the most frequently occurring words in the children’s books of that era. The list has 200 “service words” and also 95 high-frequency nouns. The Dolch word list comprises 80 percent of the words you would find in a typical children’s book and 50 percent of the words found in writing for adults.

Dr. Edward Fry developed an expanded word list for grades 1–10 in the 1950s (updated in 1980), based on the most common words that appear in reading materials used in grades 3–9. The Fry list contains the most common 1,000 words in the English language. The Fry words include 90 percent of the words found in a typical book, newspaper, or website.

Looking for more sight word activities? Check out 20 Fun Phonics Activities and Games for Early Readers.

Want more articles like this? Be sure to sign up for our newsletters.

Автор: Горбушина Оксана Сергеевна

Организация: МБОУ «СОШ №18»

Населенный пункт: Челябинская область, г. Миасс

Обучение чтению на английском языке — достаточно сложное занятие, так как есть много слов, которые читаются не по правилам, в большинстве случаев это ставит детей любого возраста в тупик, и поэтому усложняется процесс обучения чтению.

Как следствие педагог, который обучает ребенка данному виду навыка, должен владеть не просто методикой преподавания иностранного языка, а желательно современными способами преподавания, чтобы процесс обучению чтению проходил быстро, эффективно и увлекательно для детей.

Мой педагогический опят в школе составляет 11 лет, за это время мы проходили разные курсы повышения квалификации, но, к сожалению, лично я не нашла той «изюминки», за которую хотелось зацепиться и начать использовать в своей практике. Но 2 года назад случилось чудо, я познакомилась с фонетическим подходом в обучении чтению и понятием «sight words». Если о фонетическом подходе я слышала, то о понятие « sight words » в университете и на курсах повышении квалификации не говорили, поэтому я стала изучать эту тему более подробно, чтобы понять, как знание sight words может облегчить процесс обучения чтению.

Понятие «Sight words» было введено американским писателем Едвардом Уиллиан Долч в 1930 — 1940 годах. Слово « sight » с английского переводится как «взгляд», а «words» — слова. В русском языке такого понятия не существует, но можно провести аналогию с высокочастотными словами. Так вот, sight words – это слова, которые ребенку важно запомнить, чтобы научиться читать и писать. Их нужно запоминать целиком как образ, без необходимости разбивать их на буквы. Изучение sight words помогает детям быстрее научиться читать на ранних этапах. Как правило, дети запоминают слова и при чтении не задумываются, почему буква в этом слове так читается, вследствие этого увеличивается скорость чтения. Дальше перечислены некоторые примеры sight words: I, you, she, he, one, two, this, that, have, some, come и т. д.

Теперь давайте поговорим подробнее, как мы знакомимся с этими словами на занятиях с детьми возрастом от 5 до 10 лет.

Я предпочитаю вводить sight word, когда оно встречается в контексте урока или искусственно создаю ситуацию, что бы нужное слово встретилось. Так, например, мы с детьми запоминали языковую конструкцию „She is …“, и на этом этапе я ввела sight word «she».

На доске я пишу изучаемое слово и прошу детей посмотреть сначала на доску, а затем видео, где показывается параллельно графическое написание слова и его звуковое произношение. Затем после просмотра видео дети должны сказать мне, как оно произноситься. В своей работе я использую видео с ютуб канала «Preschool Prep Company» . Каждое видео – это маленькая история о слове, которая воспринимается с удовольствием.

После того, как мы познакомились со звуковым содержанием слова, дети вырезают фигуру понравившегося им животного или фрукта из бумаги и клеят на нее печатный вариант слова. Затем с помощью скотча крепят эту картинку на тонкую шашлычную палочку и втыкают ее в коробку, где «живут» у нас все sight words. Такие веселые палочки повышают мотивацию детей и позволяют педагогу быстро повторить с детьми все изученные sight words.

На следующем уроке мы опять обращаемся к нашим коробочкам, сначала вспоминаем уже изученные слова, а потом продолжаем работу над новым словом. На втором этапе дети делают рабочий лист « worksheet », который помогает ученикам запомнить написание слова. Эти рабочие листы можно найти в интернете и распечатать. Обычно они включают в себя следующие задания: найди слово и обведи его в кружок, обведи буквы слова, раскрась буквы разными цветами, найди слово и выдели его маркером, напиши его, вырежи буквы слова и приклей их в правильном порядке. Работа с рабочим листом занимает максимум минут 10, но зато дети начинают его узнавать. Однако этого не достаточно, чтобы запомнить его окончательно.

Кроме того, периодически на занятиях мы возвращаемся к sight words и играем с ними. На листах формата А4 я печатаю по одному изучаемому слову, раскладываю листы на полу, предварительно вспомнив с детьми какое слово как читается. Задание заключается в том, что дети должны наступить на то слово, которое называет учитель. Здесь важно время от времени перемещать листы на полу, так как некоторые дети запоминают не слово, а место где лежит слово. Данная игра активная, позволяет детям подвигаться, отдохнуть и заодно выучить sight words.

И последнее, что я создала для лучшего изучения sight words – это была интерактивная игра на сайте Wordwall. Wordwall – представляет собой многофункциональный инструмент для создания как интерактивных, так и печатных материалов. Игры, созданные на этом сайте, очень удобно использовать при дистанционном обучении. Мной было создано вращающиеся колесо, которое делится на несколько разноцветных секторов. В каждом секторе написано определенное sight word. Задача детей — крутить колесо и называть то слово, на которое покажет стрелка. Ребята играют в эту игру с большим интересом.

После того, как мы проходим через все эти этапы, обычно дети без проблем узнают изученные слова и они не вызывают у них никаких трудностей на всех этапах обучения чтению и письму. Чтобы читатель мог прочувствовать и понять, как детям нравится изучать sight words, я создала презентацию, где можно проследить все этапы изучения этих « обычных необычных » слов.

Список литературы:

1. http://didaktor.ru/wordwall-zamechatelnaya-kollekciya-shablonov-didakticheskix-igr/

2. https://letterland.ru/cards/

3. https://vk.com/@english.stepbystep-sight-words-chto-eto-i-kak-s-nimi-rabotat.

Приложения:

- file1.pptx.zip.. 1,9 МБ

- file0.docx.. 20,0 КБ

Опубликовано: 17.05.2021

Sight words are words that a reader automatically recognizes without having to use picture clues or sound them out. These words include very common words, such as «the» and «you,» and «make up 60 to 70 percent of most reading tasks,» according to Sandra Fleming, a teacher and writer for the literacy-promoting website, All Info About Reading. After learning these words, a reader should be able to read almost any basic reading material.

The Function of Sight Words

Sight words can be used to teach children how to read. This method of teaching reading is known as the whole language approach. Visual learners especially benefit from learning sight words, according to Sharon Cromwell in the Education World article, «Whole Language and Phonics: Can They Work Together?» Phonics involve sounding out words, and many of the words in the sight word lists cannot be sounded out. The whole language approach encourages children to learn words by recognition without using any sort of phonics method.

The Importance of Sight Words

The importance of sight words starts at the beginning of elementary school because these words form the core words of most elementary school reading materials. If a student can master sight words at an early age, he will be able to read the majority of readings he is given in the first years of elementary school. Fleming recommends in her All Info About Reading article, «The Importance of Sight Words,» that parents and teachers should «monitor sight word mastery carefully in early elementary school to be sure that this important skill is being learned.»

Sight Words Lists

According to Fleming, the most popular sight word list is the Dolch Word List, compiled by Edward William Dolch, Ph.D., and published in 1948. Not only used to teach English-speaking children how to read, this list of 220 words is in wider use in many English as a Second Language courses. Another popular sight word list is Fry’s Instant Words list, compiled by Edward B. Fry, Jacqueline E. Kress and Dona Lee Fountoukidis and published in 1993. This list consists of the 1,000 most common words in the English language.

Sight Word Activities

The website for the Dolch Word List, DolchSightWords.org, offers activities, including the games «Bingo» and «Hangman» and flashcards of sight words. Parents and teachers can also find sight word activities on teacher websites, such as the msrossbec.com website from Cresco, Pennsylvania. The website provides sight word lists by grade level, flashcards and links to other sight word resources.

The Benefits of Using Sight Words

If students master learning sight words in their elementary years, they will be less likely to have reading problems later in life. As Fleming states, it is a «vital skill» that needs to be learned in elementary school. However, if older students learning English have problems reading, they can get help from sight word tutoring because «a competent literacy tutor will check this area carefully and reteach these words as needed to build confidence and reading efficiency.»

The Difference Between Sight Words and Phonics

When learning to read, kids are exposed to two different kinds of words: decodable words and non-decodable words. Educators define sight words as non-decodable words because they cannot be decoded by sounding them out or applying the rules of phonics. Phonics, on the other hand, refers to the process of decoding words by correlating letters to the sounds they make. Students can use phonics to sound out unfamiliar words. Mastering both the recognition of sight words and the decoding of unfamiliar words through phonics can help kids become highly effective readers.

This post contains affiliate links. As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases.

Sight words vs. high frequency words. What’s the difference? This is the beginning of our blog series all about sight words.

What are sight words?

Traditionally, when teachers say “sight words,” they are referring to high frequency words that children should know by sight.

We often define sight words as words that kids can’t sound out – words like the, for example.

But this definition is not correct. While sight words may be irregular, the definition of sight words is NOT words that kids can’t sound out.

Reading researchers have a different definition of sight words.

A sight word is a word that is instantly and effortlessly recalled from memory, regardless of whether it is phonically regular or irregular. A sight-word vocabulary refers to the pool of words a student can effortlessly recognize.

David A. Kilpatrick, PhD

As an adult, most of the words you encounter are sight words, because unless you’re reading from a challenging textbook or a technical manual, you know the words automatically. You don’t need to sound them out.

What are high frequency words?

High frequency words are the words that are most commonly used in the English language. These words may be regular (as in and) or irregular (as in the).

It’s essential that students develop automaticity as they read, and one way to do this is to help them read many high frequency words by sight.

Our goal is to make high frequency words SIGHT WORDS.

We want our students to recognize high frequency words instantly. But the way we do this isn’t by giving them stacks of words to memorize.

Will students memorize some high frequency words?

Yes, at first.

They’ll memorize their names and a few other words like Dad and Mom.

And there’s nothing wrong with teaching pre-readers a small set of sight words before they begin reading. In their article, A New Model for Teaching High Frequency Words, Linda Farrell, Tina Osenga, and Michael Hunter recommend teaching the following sight words to new readers:

- the

- a

- I

- to

- and

- was

- for

- you

- is

- of

We can teach these words to students after they know letter names but before they’ve begun phonics instruction.

However.

This is just to get them started.

There’s a problem with the common practice of sending home lists of words for students to memorize. “While this method works for many students, it is an abysmal failure with others.” (A New Model for Teaching High Frequency Words, by Farrell, Osenga and Hunter).

Rather, we should integrate high frequency word instruction into phonics lessons whenever possible.

More on that in a minute. First …

What are flash words and heart words?

Some educators refer to decodable high frequency words as “flash words.” These words appear so frequently that students should be able to read them in a flash.

Irregular high frequency words are sometimes called “heart words” because there are parts of the word that can’t be sounded out; students must learn those parts “by heart.”

Teach both flash words and heart words using phonics

Be leery of any reading program that says students need to “just memorize” irregular words.

Rather, look for a program that organizes high frequency words to fit phonics lessons wherever possible.

In other words, teach the word can when students know the sounds of c, a, and n.

Even with irregular words (“heart words”) we can all attention to the part of the word that IS regular.

Really Great Reading has some excellent instructional videos to help you teach those tricky heart words.

Find all of Really Great Reading’s “heart word magic” videos here.

Will we just ask students to memorize SOME sight words?

Yes. High frequency words are the glue that hold decodable sentences together. We want students to know some of these words so the decodable books they read make sense.

Because of that, we’ll teach a small number of sight words to pre-readers, and additional words as needed so our students can read their decodable books.

But let’s let go of this idea that students need to memorize lists and lists of sight words.

Turn high frequency words into sight words with these engaging mats!

High Frequency Word Practice Mats – 240 words!

$24.00

Students will count the sounds in words, spell them, read them in context, and more! What a meaningful, multi-sensory way to master high frequency words!

Stay tuned for the rest of this series!

Part 1 Part 2 Part 3 Part 4 Part 5 Part 6 Part 7 Part 8 Part 9

Let me guess, you’ve been working day and night to make sure the little one has their sight words down packed! The teacher has said that their reading will skyrocket if they can just get the sight words in their working memory.

Sound familiar? I’m sure it does!

But what the teacher may not understand is the limited time you may have when you get home to prep dinner, assist with homework, clean, and squeeze in a bedtime story if you’re lucky. Trust me, I’m doing good if I can get my two and nine year old in the bed without a complete meltdown!

Here’s the deal.

Time is limited, your workload is heavy, but the taxing reading requirements don’t change. How do you manage? What takes priority? ….you may even be thinking how can I help with sight words if I don’t really understand their importance?

Well there’s good news! You can absolutely prioritize in your daily routine without losing your cool at the kitchen table, in less than 10 minutes. However, before we get there and take a look at how to do this, it’s SUPER important that you understand the science behind sight words and how they’ll transform a young readers comprehension experience.

Just What Are Sight Words?

By definition, sight words are those that regularly appear in all texts (fiction and nonfiction), but don’t follow a specific spelling pattern. Therefore, using learned decoding strategies can be unreliable and cause poor reading accuracy. Knowing this, most educators and current researchers encourage students to memorize these highly accessible words.

Choosing The Best Sight Words!

Listen, don’t get carried away with teaching random sight words! In the long run, it’ll do you no good. Here’s why, your child can be so focused on “memorizing” and not focused on how it connects to their task of reading.

Simply said, do your best to teach the necessary sight words based on their independent reading level! This simple shift will allow for your child to practice with the skills they need at the moment. For example, if your child is reading at a beginning first grade level, roughly a guided reading level “E,” it doesn’t make sense to instruct them on sight words from grade 4.

Now I know, you want them to be prepared, advanced, and one step ahead. But a good rule of thumb in reading is to crawl before you walk. Whatever they don’t master at their level, will only manifest in poor reading habits as they move up in age.

Trust where they are and give them the best you’ve got on their level!

They Know Their Sight Words, So Now They’ll Comprehend…

Unfortunately, no. This is one of the BIGGEST misconceptions I’ve come across in doing my research. Many feel that effective memorization of sight words leads to overall comprehension of the selected text. What I’ve come to know is that it’s just not true. Having a strong sense of these words helps to develop powerful word recognition, leading to flawless fluency, which helps establish comprehension.

Think about it for a sec, imagine having to travel to a specific destination. The trip should only take maybe 2 hours. However, because you couldn’t understand the provided map, the trip lasted 6 hours. Imagine if you could read the map, you wouldn’t dread the destination, instead you’d be excited about the arrival.

The same remains true for our babies. Stopping and decoding EVERY word leads to laborious reading, sounding much like a robot. Experiencing this each time they read greatly reduces the higher level of comprehension expected.

Remember, we want them to comprehend, not be great word callers!

Now What?

Alright, so you’ve got the basics and the science. Here’s a few tips incorporate sight words into your daily routine.

- Set aside at least 10 minutes per day for explicit sight word instruction. You may do more, but don’t overwhelm them. The best gauge is the child. See how long they can take before checking out.

- Be super intentional about the amount and level of words you introduce. Research has shown when there is a rhyme and reason for a task, the easier it will be for them to pick up on the content.

- Try using the same routine each time when you introduce the new words and review. If the process changes each time you teach a word, then so will the way they learn. A good rule of thumb is to KISS (Keep It Simple…). You shouldn’t have to plan out strenuous activities daily.

- Lastly, make sure the instructional practice is tactile and allows them to see the word in context of a sentence. Simply repeating the word and cold calling out letters can become mundane, spice it up just a bit!

Here’s A Quick Solution

I don’t want you out here reinventing the wheel! If your daily routine is anything like mine, I’m almost certain finding time to create sight word lessons can be challenging. Here’s the thing, I had you in mind when I created the Ten Minute Sight Word Daily Review Program – an intentional flashcard program to increase word recognition. I knew you would want to explore and implement a system that’s ready made for your family.

What’s included?

- Sight word flashcards for guided reading levels A-P!

- Specific instructions to establish a daily routine.

- Sentences that utilize each sight word.

- Assessment instructions and what to do when your child has mastered certain words.

- Ways to spice up your sight word activities.

Grab the FREE download by clicking here and once you do, make sure to share your feedback!

Happy reading!

When you hear the words “sight word instruction”, what do you think of? I can honestly say that my idea of what “sight word instruction” means and looks like has drastically changed over the years. In fact, my definition of “sight words” has even changed.

Often the term is used interchangeably to mean a few things: high-frequency words, irregular words, and words that students recognize on sight.

I used to think of sight words as words that couldn’t be sounded out and needed to be memorized. I also thought of them as words that needed to be memorized as a whole. I used the flash card method mostly, with the belief that if my students saw these words enough times, they would memorize them. This turned out to be true for some of my students. However, it certainly was not the case with many of my students. I started to look into why. I eventually learned that the research points to more effective methods of teaching “sight words”.

What are Sight Words?

Now I define sight words as words that can be read instantly and effortlessly (“on sight”).

- High-frequency words are words that are the most occurring in print. Because they are words that our students will most likely encounter in a text, we often work hard to help these become “sight words”.

- This includes words that are fully decodable and words that have some irregularities.

- Technically, the goal is to make every word a “sight word” but in the beginning, it is helpful for students to know these particular high-frequency words since they account for 75% of words in print.

- The fancy word for “sight word” is orthographic lexicon, or the words that a reader can read automatically and without any effort.

There are two main lists that most teachers pull from: the Dolch and Fry Lists, that include the most frequently occurring words in children’s texts. Both of these lists were originally created to use the “look-say” method (essentially whole language approach).

We now have more research to draw from that tells us reading outcomes are stronger when beginning readers are taught to decode words using sound-symbol associations, rather than rote memorization. That goes for all words, including regular and irregular high-frequency words.

Why is Teaching Sight Words Important?

Knowing that these high-frequency words appear more often in children’s texts means we should spend a little more time on these words so that our students can read them automatically and with little effort. Helping these high frequency words become “sight words” will begin to improve their fluency because automatic word recognition is the first step toward fluency (followed by developing prosody, rate, expressing, and appropriate phrasing).

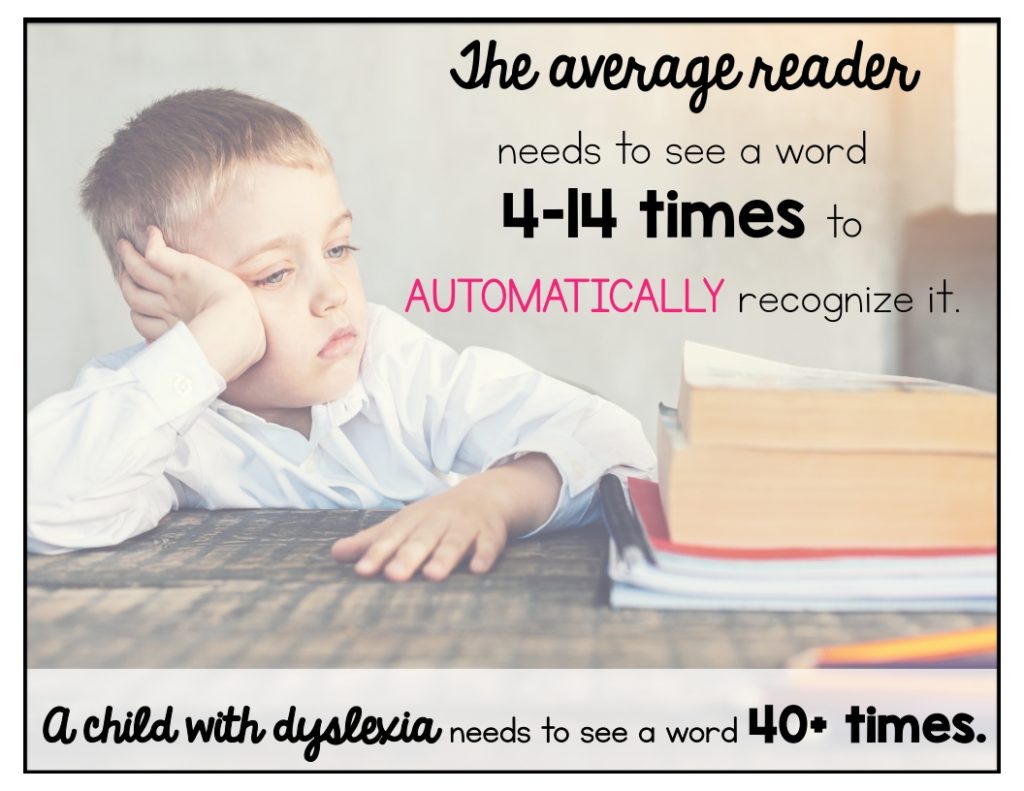

Even your average beginning reader needs to be exposed to a word several times in order to read it with automaticity. Students with dyslexia need SEVERAL more exposures to those words. We need to provide them with those opportunities to practice these words.

However, by second grade on, your typically developing readers are able to store a new word permanently in only one to four exposures (Bowey & Miller, 2007). The exact number for readers with dyslexia is not known, although I can tell from experience, it’s a lot more than that and it varies from student to student.

Some Facts about Sight Words

Another thing we need to get out of the way is the idea that most “sight words” (high-frequency words) are all irregular. I’m going to throw some facts out there:

- Many high-frequency words are decodable.

- The majority of irregular words actually only have only one irregular letter-sound relationship.

- Even though these words are irregular, they are still stored in our long-term memory using the same orthographic mapping process as regular words.

- Most of these irregular words have a history (etymology) and relatives that actually do explain the spelling.

How Do We Learn Sight Words?

How do our brains process and permanently store words into our sight memory? Orthographic mapping! According to David Kilpatrick, new readers map the phonemes (sounds) of words (that they already have in their phonological memory) to the sequence of the letters they see on the page. Once a word has been adequately mapped, it is there for quick, effortless retrieval.

Ortho means straight (correct, in order, sequence) and graph means writing. Together that makes correct writing.

We form connections between the pronunciation of a word (with the individual sounds) and the order of the printed letters. We are connecting sounds to sequence of letters. This connection is called “mapping”. Orthographic mapping allows our brains to permanently store words, so we can retrieve them automatically.

We need three things for this to happen:

- Automatic sound-symbol awareness

- Phoneme awareness

- Word study: helping students see the connections between letters and sounds

Here’s a tidbit I just learned: According to David Kilpatrick’s book Essentials of Assessing, Preventing, and Overcoming Reading Difficulties, we actually do not memorize sight words using our visual memory. We use vision for input but not for storage. Instead, storage is orthographic, phonological (sound), and semantic (meaning). Mind blown, right? That means new words are not simply memorized just by seeing it over and over.

For more about orthographic mapping, click here.

Another study out of Stanford found that “beginning readers who focus on letter-sound relationships increase activity in the area of the brain best wired for reading. In other words, to develop reading skills, teaching students to sound out C-A-T sparks more optimal brain circuitry than instructing them to memorize the word cat.” This also debunks the idea that high-frequency words should be learned using the “look-see-learn” whole language method.

How to Teach Sight Words

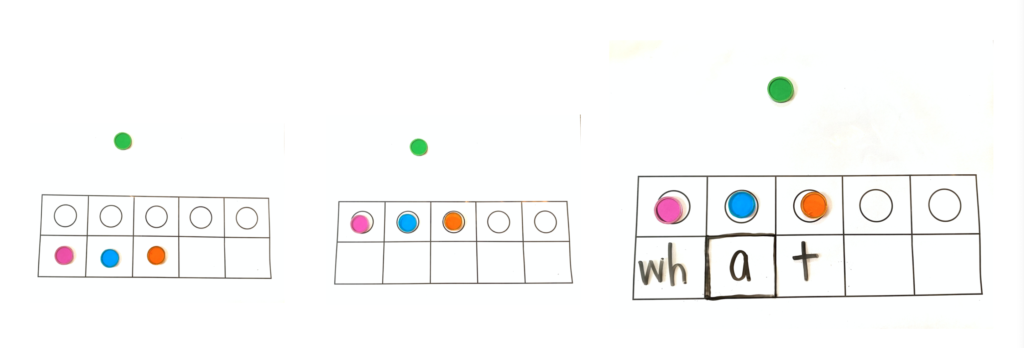

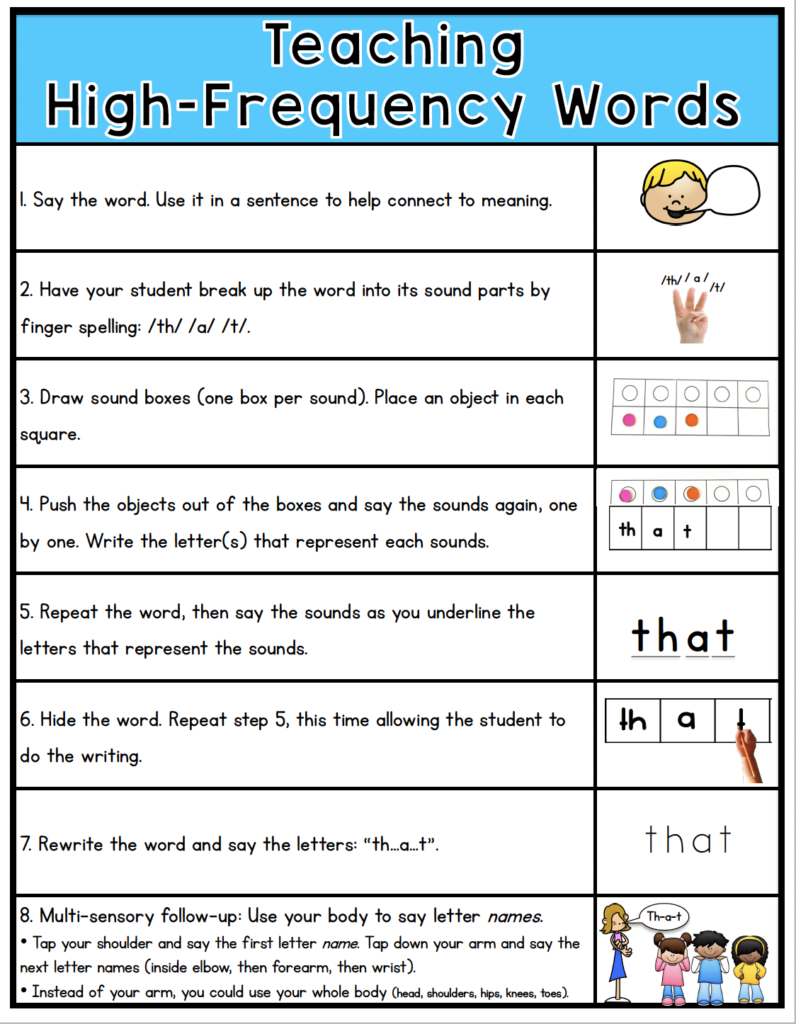

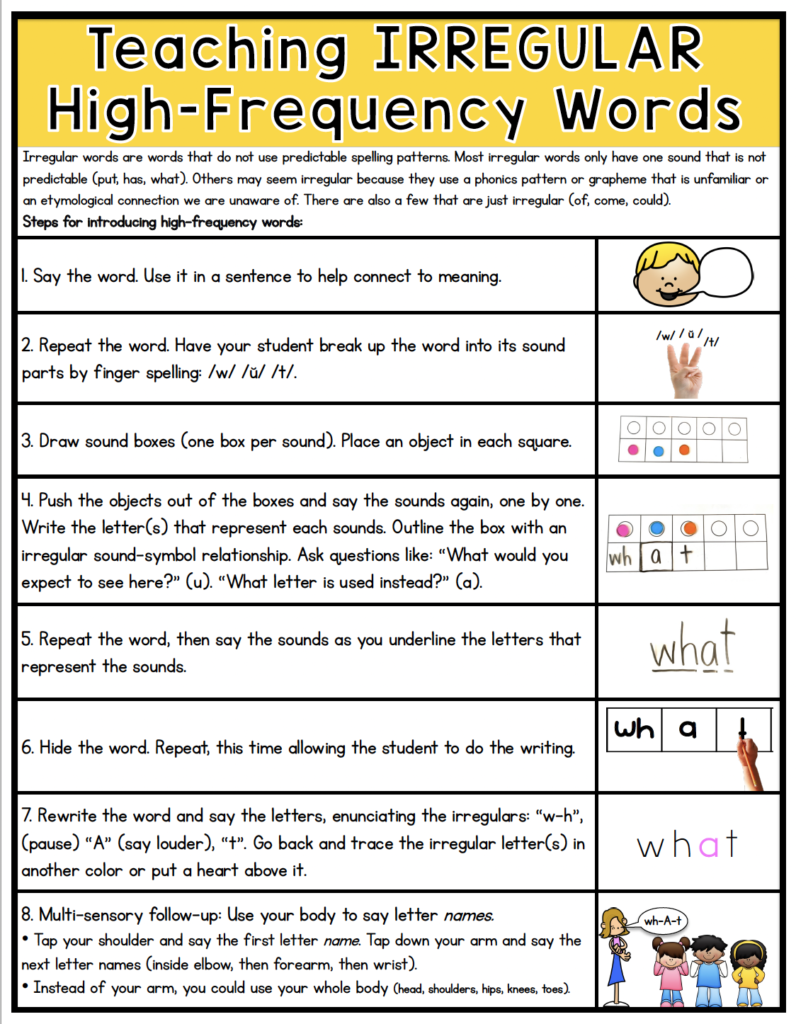

Now that I have a better understanding of how our brains learn new words, I’ve made some changes to how I approach sight words. Now, the first thing I do is introduce the word orally and explicitly teach the sound-symbol connections.

Step 1: Match the Sounds to the Correct Letters

Here are the steps to take;

- Introduce the word and show the student:

- Say the word.

- Write the word and show your students.

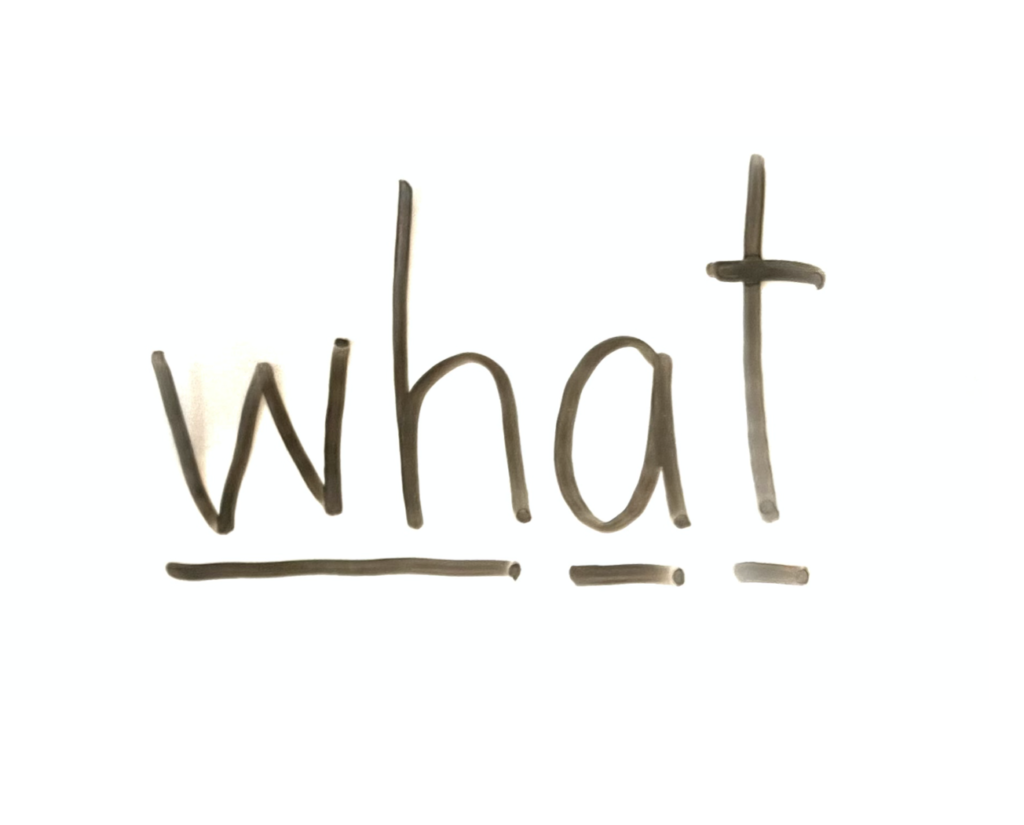

- Use your finger to tap under the letters as you break the word up into its sound parts. (For the word “what”, you would underline with your finger (or actual underline as shown below): <wh> as you say /w/, underline <a> as you say /u/ and <t> as you say /t/. Erase the word or move it away.

- Repeat the word

- Segment the word into its individual sounds.

- Draw dots, sound boxes, or use bingo chips to represent those sounds.

- Students will tap the sound boxes or slide the bingo chips as they say the sounds. For example: /w/ /u/ /t/.

- Discuss what letters you expect to see representing each sound.

- If there is a word that has an irregular sound-symbol relationship, I often outline that box in another color if I’m using sound boxes or use another color for the dot if I’m just making dots.

- Show the word you had written in the first step. Underline with your finger again the letters as you say each sound. Point out the unexpected sounds.

- Have your students write the letters that go with each sound in the sound boxes or above the dots.

Click HERE to download the printable below.

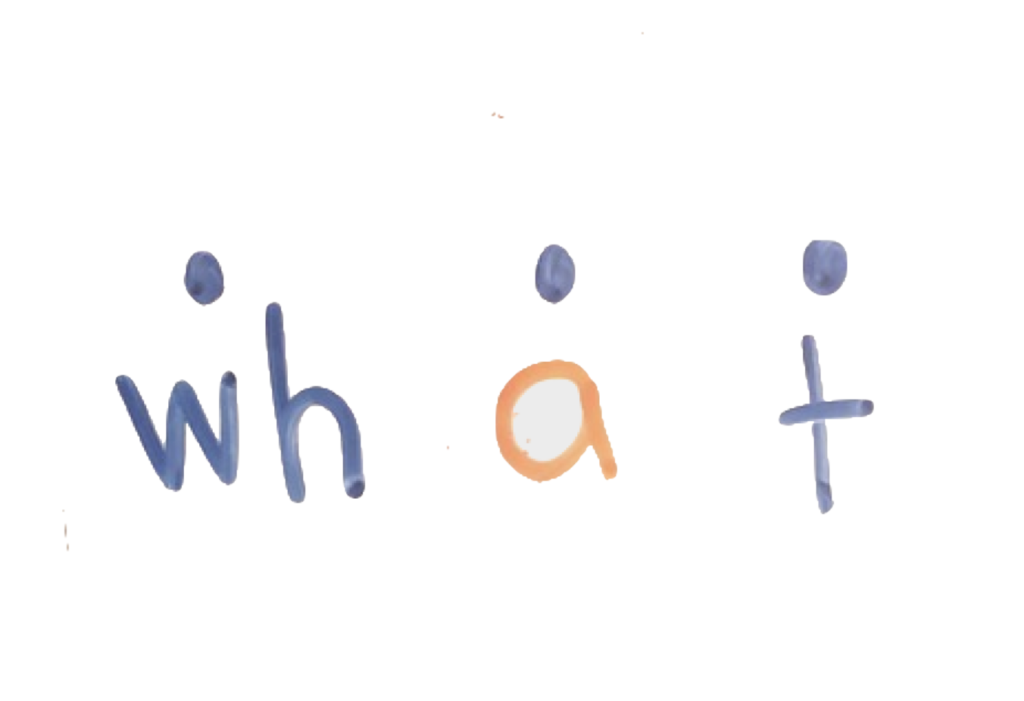

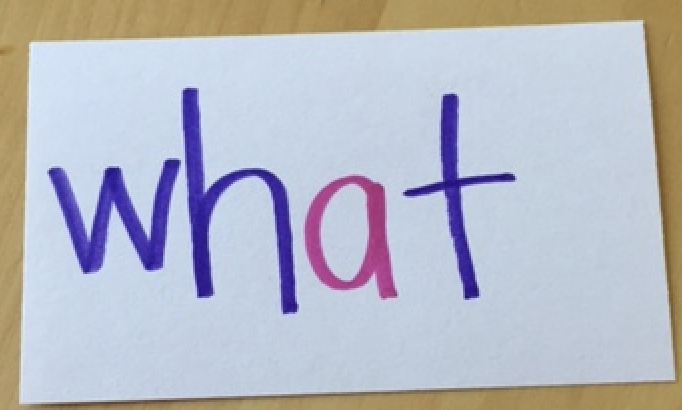

Highlight the “Irregular” or Unexpected Sound

This is another tip that I find very helpful. Somehow highlight the unexpected letter-sound relationship.

For example: Connect the sound /w/ with <wh>, /u/ with <a>, and /t/ with <t>. Then highlight, underline, or use another color for the letter <a>. You could also underline that letter.

Update: I have now learned of a method called “heart words” where people put a heart over the irregular sound-symbol relationship. When I originally wrote this post years ago, I had never heard of heart words, but I do love this idea!

Show your students the word with the highlighted “odd” or unexpected letter(s). Practice spelling the word as you did earlier (in the above tip.) This time enunciate the odd letter(s) vocally. “Wh-A-t” You could enunciate it with a louder voice or with an accent or with a funny voice- anything to get that letter to stick! Notice how I also said wh together. That is intentional because I want them to group those two letters since they are one grapheme representing the sound /w/.

A lot of times, there may actually be a reason for the unexpected sound-symbol connection. In this case, teach your student why that letter is used.

- For example, the word give and have end in the letter e. This makes our students think that it is not fully decodable. But actually, there is a reason for that e. Did you know an English word should not end in v? So that silent e has a purpose, just not one that they are used to. (The e is there to make sure the v isn’t the last letter.) Click here for more about the “rules” of spelling.

- In the word, around and about, the a says /uh/ which makes it trickier. Well, that is also a phonic thing called Schwa.

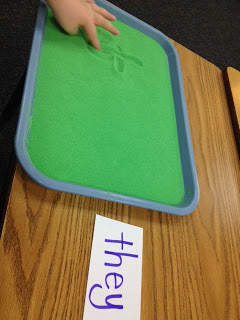

Step 2: Make it Multi-Sensory

This is nothing new but it’s always worth saying. Students need to see it, say it, write it, feel it, and hear it.

- Have students say the letters in the word as they trace the letters.

- Repeat. Say the word again.

- Have the student write the letters in the air AND on the table or a bumpy surface, saying the letters as they trace, repeating the whole word when they are done.

- After seeing and tracing the word, guide your student to try to take a “snapshot” of this word in their brain: Look at the word, say the letters, then close your eyes and try to see the word repeating the letters. I try to group letters together that go with sounds. For example, wh-A-t. I say the <wh> together because they make one sound together. I say the <a> louder because it is irregular.

To spice it up, use sand and/or add glue to the flashcards to give them a bumpier feel. I often use these foam sheets with different textures for students to trace on. If you don’t have all of these extra things, that is okay. Truly, multi-sensory just means uses multiple senses. That means multisensory can just mean you say, see it, hear it, and write it.

A popular method that Orton-Gillingham tutors use is the Arm Tap.

- Begin at the shoulder.

- Say the first letters as you tap your right shoulder with your left hand.

- Move down your arm and say the other letters as you tap down your arm.

- Once you’ve said all the letters, repeat the word as you slide your hand from your shoulder to your wrist.

For example, the word what would go like this: “w-h” (tap shoulder), “a” (say louder since it’s an oddball and tap inside elbow), and “t” (tap wrist). I’m not sure if there is actual research to back this method up, but it is another way to practice the word and it’s always nice to get kids moving!

Step 3: Repeat, Repeat, Repeat

This one is obvious, I know! Remember how a child with dyslexia needs to see a word 40+ times? That’s a lot of exposures for that little one. My challenge is always, how do I do this without boring my kids to tears?! I think playing games is a great way to get that repetition.

Below are some easy games to play (with free editable templates):

Spin and Read: You can make your own spinner using a metal fastener. Write the words you are working on in the spinner. Make a chart like the one shown next to the spinner. Write each word in the first column. After you spin, read the word you land on. Then write that word in the second column in the correct row.

Roll a Word: Make a chart like the one shown below (with the dice). Instead of the dice that are shown, simply write 1-6. Write a sight word in each box. Roll the die. Read the words under the number that you landed on.

Tic Tac Toe: Write your sight words on a stack of index cards. Draw a card. Read the word. Write the word on the Tic-Tac-Toe board. (Each player will have a different color marker.) The next player does the same. Continue as you would with Tic-Tac-Toe, trying to be the first to get three in a row.

Word-O: Draw a 3×3 or 4×4 grid. Ahead of time, each player writes the same sight words on their own board in different spaces. Write those same words on index cards. Draw an index card. Read the word. Then cross out that word on your board. Continue until someone gets three/four in a row or black out.

As fun as games are, it’s also so impactful to give them plenty of practice to write the words again using the sound boxes, making the connection from sound to symbol and reviewing any irregular part.

Using Flash Cards Effectively

After we’ve done phoneme-grapheme mapping, then I bring out the flashcards for students to practice. One common mistake I see/hear about a lot is not letting kids sound out the word when they are using flash cards. Teachers will say, “If they don’t know the word automatically, I tell them the word and then skip it and come back to it because they need to know it automatically.” I was also one of these teachers.

But think about it. If they don’t know the word, then it’s just a random sequence of letters to them or a shape. And that shape looks like many of the other shapes on those flashcards. So, you telling them the word and then simply bringing it back again doesn’t help them at all. It’s that look-say method that we learned doesn’t actually work for many students. If they don’t know the word on sight yet, that means they don’t have it stored yet. Letting them sound out the word is okay because they are trying to use what they know to figure out the word. I recommend following the steps I’ve listed before.

When reviewing words using flashcards, follow these steps if a student doesn’t remember a word or says an incorrect word (going back to step one from above):

- Hold up the flash card.

- Say the word.

- Repeat the word, this time slower to enunciate each sound. As you say the sounds, underline the letter(s) that say each sound with your finger (even if it is irregular).

- If there is an irregularity, ask, “What sound do you hear here? What letters make that sound for this word?”

- Say the word again, sliding your finger under the whole word.

- Repeat the “arm tap” or just say the letters of the word again. For example: “they. <th> <EY>. they”.

- Give them the opportunity to write that word again, saying the letters.

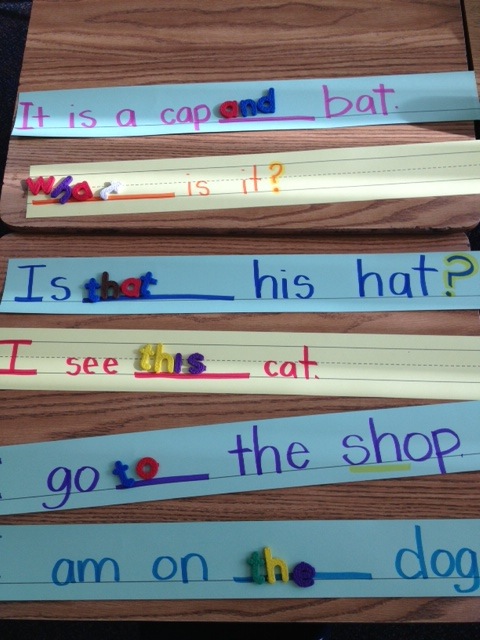

Step 4: Spot it in Context

This should be done after a word has been introduced and you’ve done phoneme-grapheme mapping. Research shows we want to move away from using context to guess words. Guessing is not a decoding strategy. However, I still feel like this activity is a good way to practice spelling words while thinking about meaning. It is not using context to decode. It is using context to apply meaning to the word.

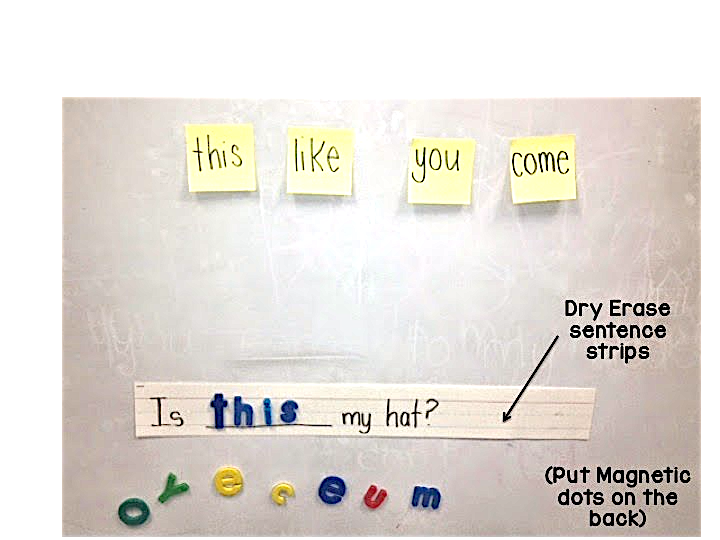

Write a sentence on sentence strips or on the whiteboard with a blank in the middle. Put the letters of a sight word scrambled next to or on the blank. Read the sentence, determine the word, then spell it correctly. Afterward, you can connect back to the sounds. Say the word, and point to the letters as you make their sounds. That means for a word like “what”, you would point to both <wh> for /w/.

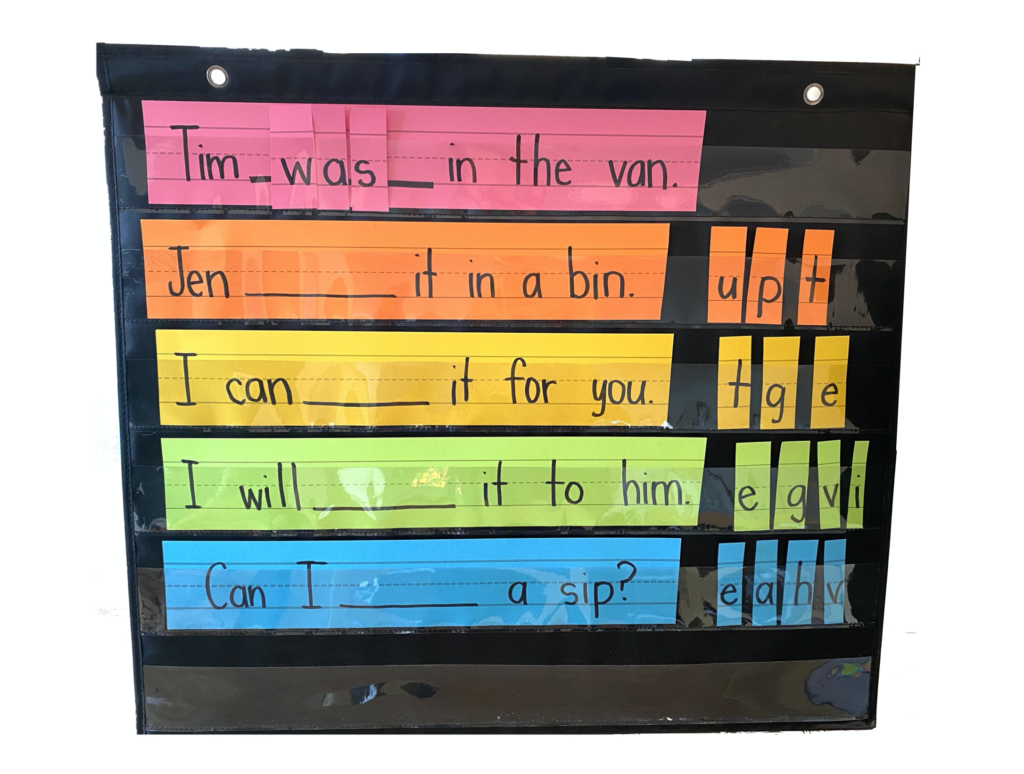

For a larger group, put the sentence strips in a pocket chart with the sight word chopped up into letters.

You could also write the sentence on a magnetic whiteboard and use letter magnets.

I just want to be clear that this is not used as a decoding activity to guess as a reading strategy. Admittedly, that’s how I used to use these! Since then, I’ve learned that we do not want to put too much focus on using context because it takes away from decoding and leads to bad habits. I think it’s a fine activity to use once words have been taught explicitly. Plus kids see it as a puzzle and it can be fun for them.

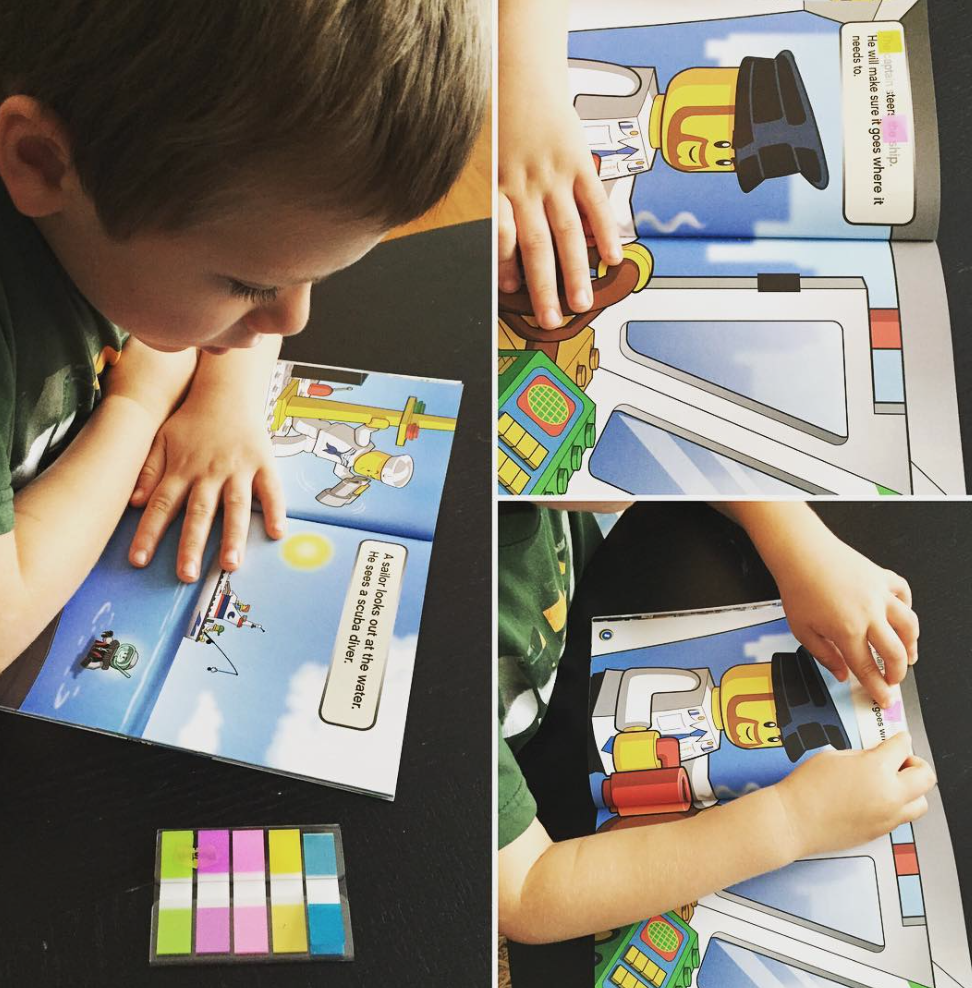

Sight Word “Hunts”

Get your students looking for those words! This can be a center, an independent activity, or a warm-up in reading groups. Have your kids look for a certain word in books or big poems.

I blogged about this picture already last year. Both of my boys loved to search for words like this. They would focus on one word and try to find it. This was nice in the beginning because they didn’t necessarily have to know the other words on the page yet. They were just looking for that one word. I have several pre-made word hunts that I will show at the end of this post!

Step 5: Build from Words to Phrases to Sentences

The purpose of mastering high-frequency words is to gain automaticity with these words so that eventually your students will become fluent readers when reading a book or reading passage. BUT sometimes we skip so many steps in between. I know I’ve been guilty of that. Okay, you know that word, sweet! Let’s read this huge passage then. Wait! Rewind. What I mean is, let’s give you those building blocks so that you can read that huge reading passage. Our struggling and beginning readers can be VERY intimidated by a huge reading passage without support. With that said, many of our students learn sight words quickly and are ready for huge passages pretty quickly. I’m more focusing on your students who need a little extra time and guidance.

Sight Word Phrases

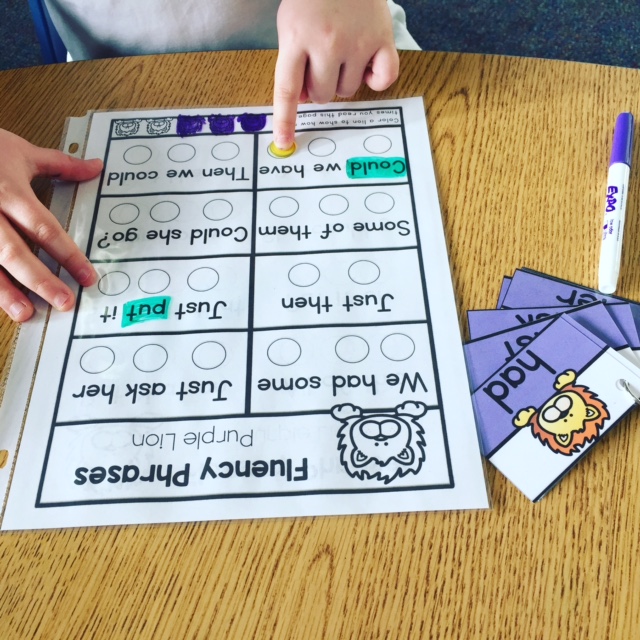

We’ve talked about practicing high-frequency words in isolation. Now we’re moving into reading those words in the context of a phrase, sentence, or reading passage. First, you can focus on phrases. These are the common phrases that go together. This is a great way to transition from word to sentence. It’s good for them to see these words in some context. You can actually find fluency phrases all over! Just google and there you will find tons.

I used these after my students had a little practice with the sight words individually. They are phrases, not complete sentences yet. It gives students the chance to practice reading with a little context.

Simple Sentences

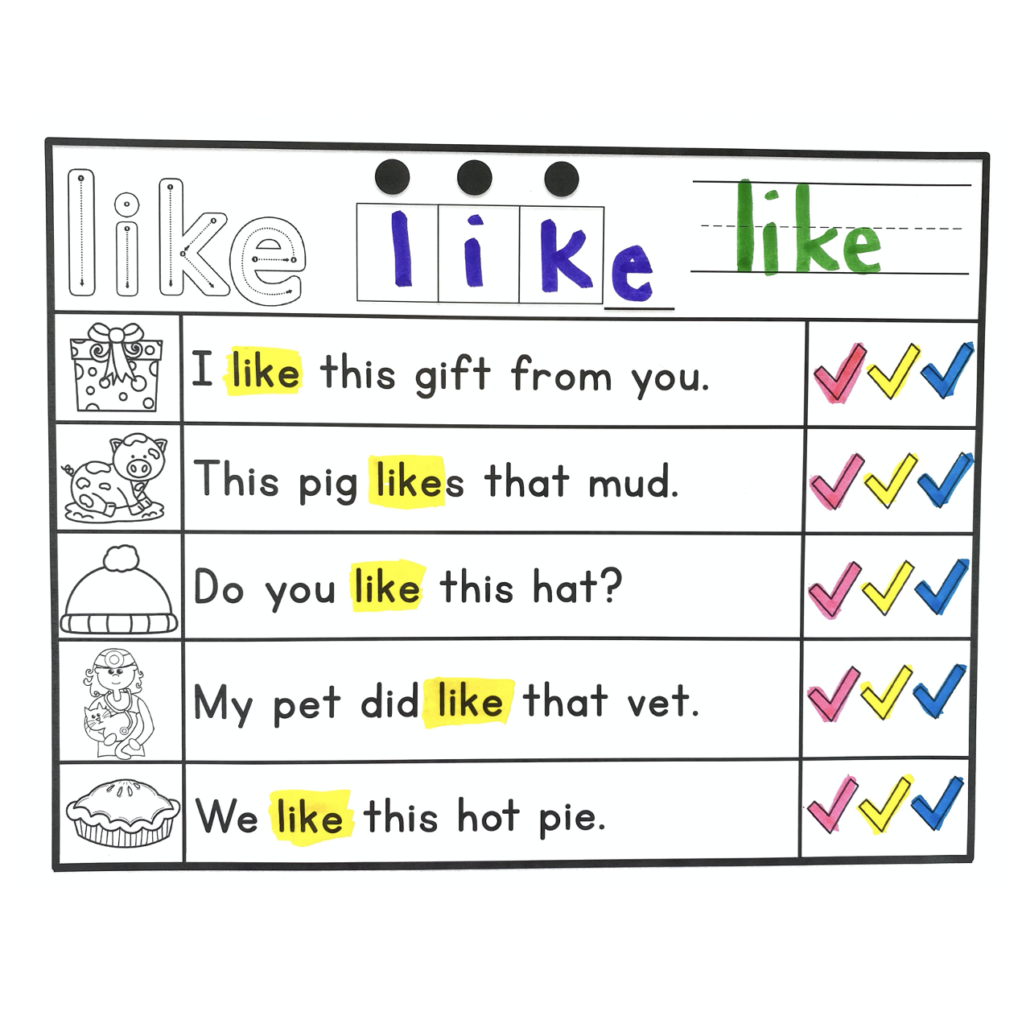

Here, I’ve made sentences with a focus on one high-frequency word. This one has the word “like” in each. I made sentences where the student could be successful using their knowledge of the new word, other high-frequency words they’ve already learned, and decodable words. This way, they can practice those words within connected text and be successful!

Give your students practice reading those words in context where they can be successful. You can write simple sentences using sentence strips or on chart paper, too!

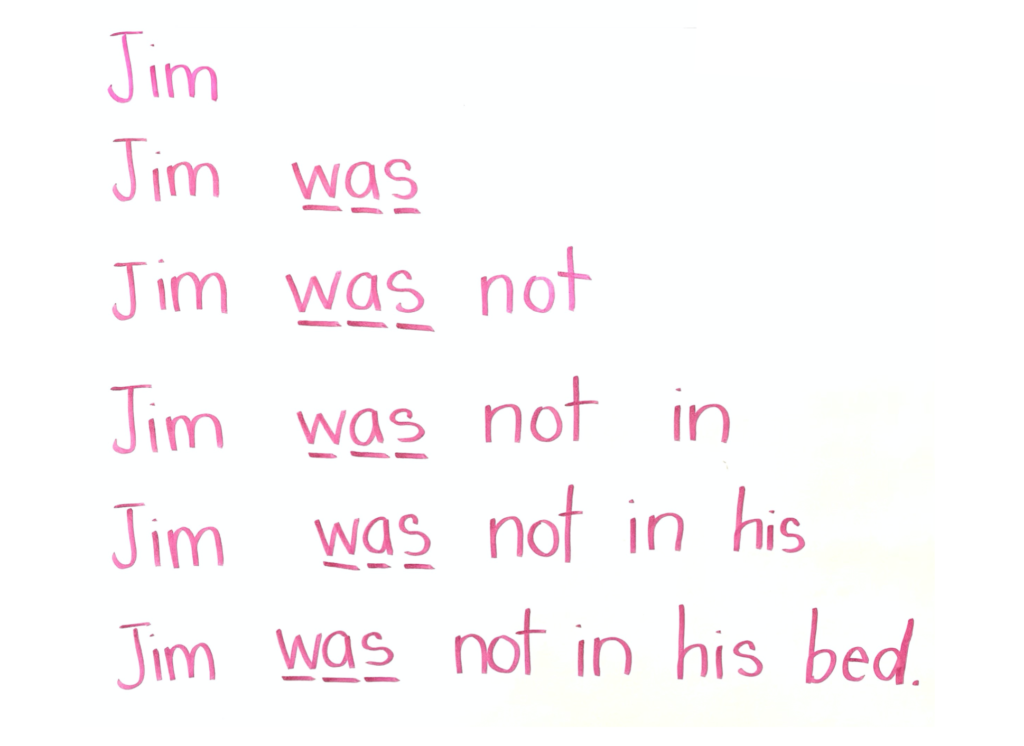

Sentence Ladders

Once students know a handful of sight words and are even reading those fluency phrases, we get a little excited about throwing them that reading passage or big ol’ book to read. And yes, absolutely that is our goal and many, many kids make that transfer seamlessly and quickly. However, some need a little extra something. I love making Sentence Ladders for my students. It gives them practice with sight words and helps develop fluency because they are rereading words in a sentence over and over.

Which List: Dolch, Fry…or Neither?

Originally, I was using the Dolch list. I created a ton of resources based around this list. I did and do love these resources and found they really helped my students. However, I also felt like these resources didn’t fit into my big picture instructionally. As I learned more about the science of reading, I started to rethink my approach.

Mainly, I was seeing that here I was teaching my kinder students to decode and spell CVC words. For my struggling readers, this was a lot. They would make gains with the right systematic, explicit instruction and were developing an understanding of how words work, at a pace that was appropriate. But then I’d also be like, “Oh yeah and we also have to learn the words “come”, “down”, and “find” because those are on the Dolch kindergarten pre-primer list and that’s just what we do. So, even though it felt like this just didn’t fit with everything else I was doing, I was still doing it. I created the Dolch resources you’ll see below and really tried my best to make them work. I think what I came up with was helpful considering these words were out of place with the rest of the curriculum.

Then I had an epiphany. Wait, I don’t have to teach high frequency words in this order, especially if the science is telling me otherwise. But not just the science. My students were showing me this too. I had already restructured the way I teach high-frequency words. Now I was going to change the order in which I teach them.

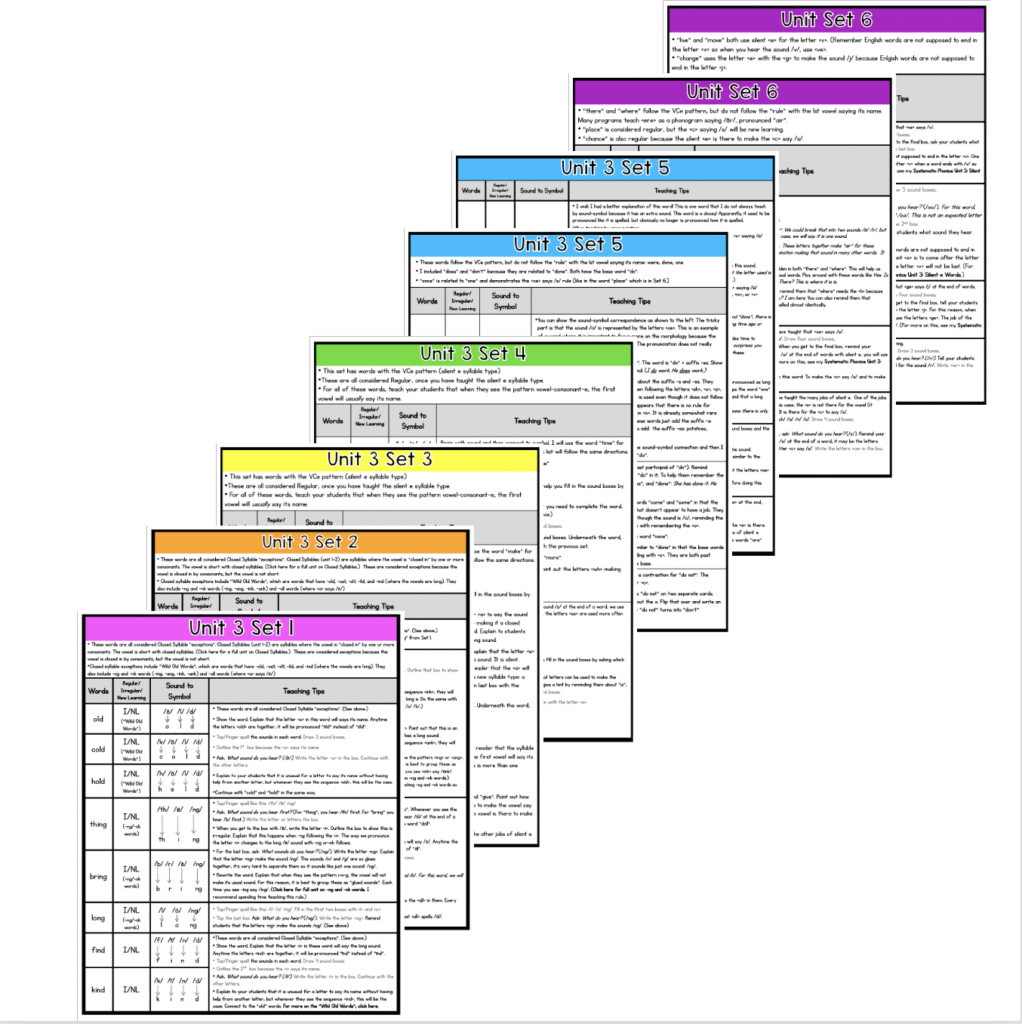

I looked over the Dolch and Fry lists and grouped the fully decodable words phonetically. Then I looked at the words that were decodable except for only one or two sound-symbol relationships. I placed those into the groups that made the most sense. Last, I looked at the real odd balls. These are the few words that really are irregular in my mind. I placed those where I felt they made the most sense instructionally.

Once I had a sequence, broke the words up into smaller, more manageable groups. This is one thing I had also done with the dolch list and it really helped my students. They felt more success when they mastered a small set of words (as opposed to looking at this huge list).

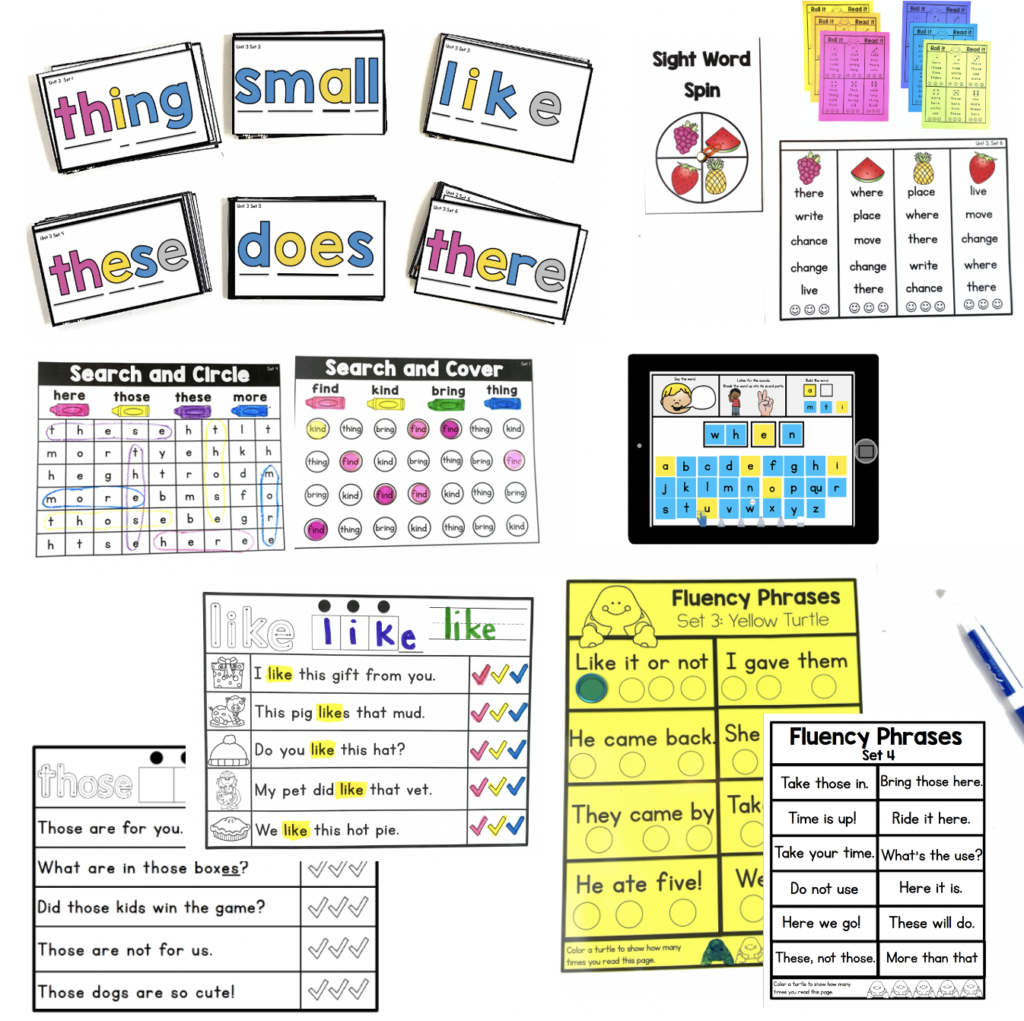

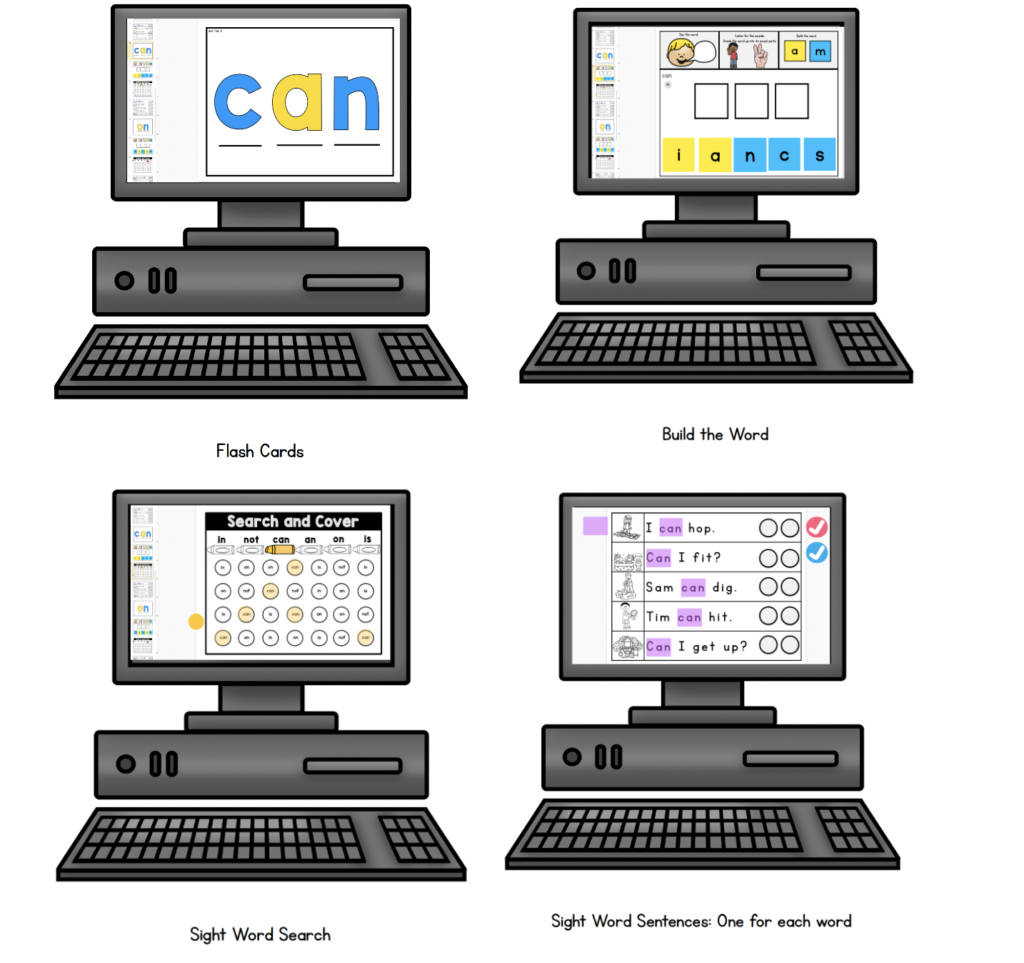

Then, I started making activities and teaching resources to go with those words and groups. I made flashcards that mirror the way I teach the words, fluency phrases for each group, sentences focusing on each sight word, word searches, and games.

Sight Word Instruction Resources

I have two different sight word resources. I explained above my evolution with sight word instruction. For this reason, I have two sets of sight word resources: Several resources based around the Dolch list and new resources using the phonetically-grouped list of words. I now use the phonetically-grouped list.

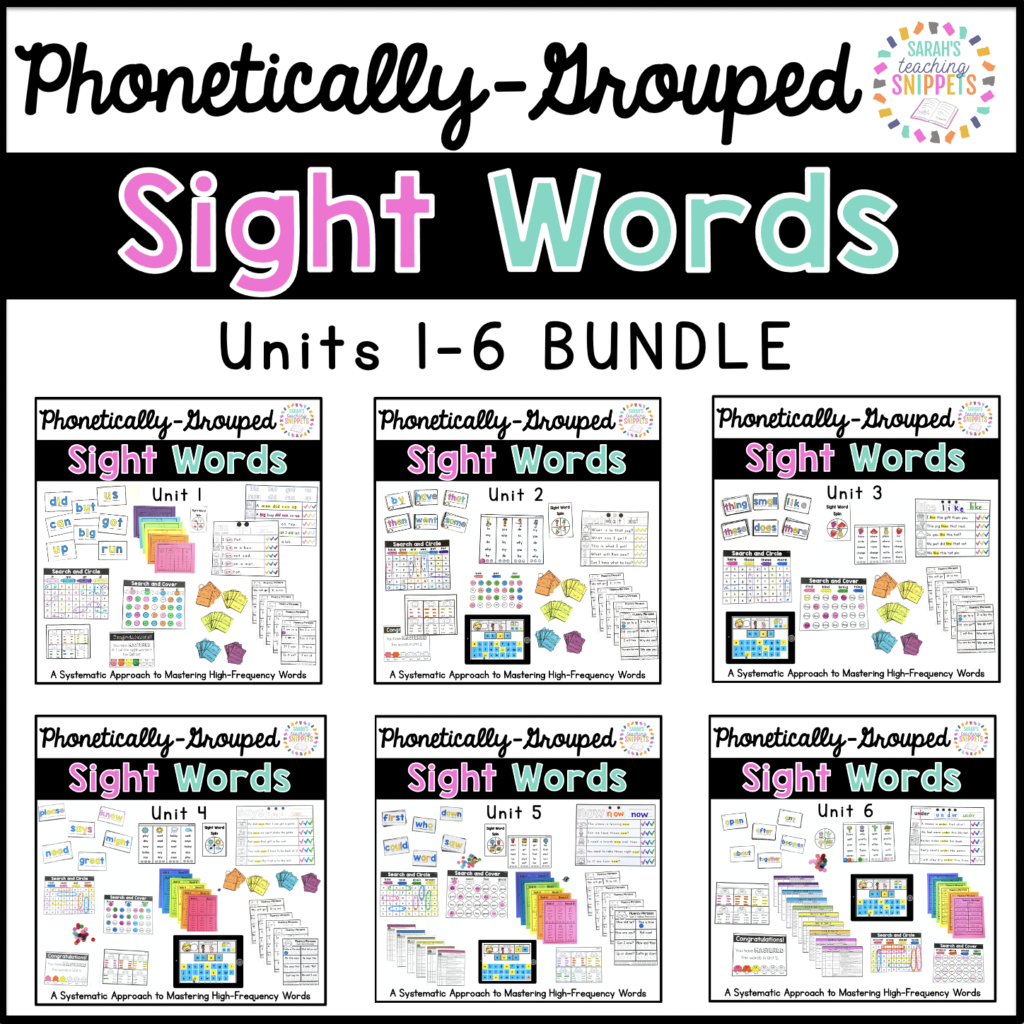

Phonetically-Grouped “Sight Word” Units

To integrate my “sight word” instruction into my existing phonics instruction, I grouped the high-frequency words phonetically. Like my Dolch units, I have one animal to represent each unit and then each unit is further divided into smaller sets, each with a color. In total, there are 6 units. See below for how the words are grouped:

This shows some of Unit 5.

- There are two choices for “flashcards“. One option is color-coordinated with vowels one color and consonants another color. There are also the underlines that represent sounds. (This is my favorite.)The other option is the more cutesie animals.

- There are “fluency phrases” (“printable” option and smaller cards to laminate). Those are just short phrases with high-frequency words from that set.

- Word Searches

- Automaticity games (one for each set): Spin and Read or Roll and Read

- Sentences: Each word has a whole page of 4-5 sentences and then another page that reviews all the words from that set. Option with pictures or without.

- Tracking sheets

There are also directions about how to teach the words using phoneme-grapheme mapping, along with any helpful tips.

I also made Google Slides:

THIS LINK will lead you to the bundle of all 6. If you just want to look at one unit, you will see a link to each individual unit from there.

References

David Kilpatrick’s books: Equipped for Reading Success and The Essentials of Assessing, Preventing, and Overcoming Reading Difficulties.

Louisa Moats: Speech to Print and LETRS books.

A Fresh Look at Phonics by Wiley Blevins.

Rethinking Sight Words. Article by Katharine Pace MilesGregory B. RubinSelenid Gonzalez‐Frey from the International Reading Association Journal.

Additional Posts about Sight Words

For another posts about sight words, click here. There, you will find ideas for the summer AND a printable pack for parents filled with ideas to practice sight words.

You can find this blog post here.