Types of Word Formation Processes

Compounding

Compounding forms a word out of two or more root morphemes. The words are called compounds or compound words.

In Linguistics, compounds can be either native or borrowed.

Native English roots are typically free morphemes, so that means native compounds are made out of independent words that can occur by themselves. Examples:

mailman (composed of free root mail and free root man)

mail carrier

dog house

fireplace

fireplug (a regional word for ‘fire hydrant’)

fire hydrant

dry run

cupcake

cup holder

email

e-ticket

pick-up truck

talking-to

Some compounds have a preposition as one of the component words as in the last 2 examples.

In Greek and Latin, in contrast to English, roots do not typically stand alone. So compounds are composed of bound roots. Compounds formed in English from borrowed Latin and Greek morphemes preserve this characteristic. Examples include photograph, iatrogenic, and many thousands of other classical words.

Note that compounds are written in various ways in English: with a space between the elements; with a hyphen between the elements; or simply with the two roots run together with no separation. The way the word is written does not affect its status as a compound. Over time, the convention for writing compounds can change, usually in the direction from separate words (e.g. email used to be written with a hyphen. In the 19th century, today and tomorrow were sometimes still written to-day and to-morrow. The to originally was the preposition to with an older meaning ‘at [a particular period of time]’. Clock work changed to clock-work and finally to one word with no break (clockwork). If you read older literature you might see some compound words that are now written as one word appearing with unfamiliar spaces or hyphens between the components.

Another thing to note about compounds is that they can combine words of different parts of speech. The list above shows mostly noun-noun compounds, which is probably the most common part of speech combination, but there are others, such as adjective-noun (dry run, blackbird, hard drive), verb-noun (pick-pocket, cut-purse, lick-spittle) and even verb-particle (where ‘particle’ means a word basically designating spatial expression that functions to complete a literal or metaphorical path), as in run-through, hold-over. Sometimes these compounds are different in the part of speech of the whole compound vs. the part of speech of its components. Note that the last two are actually nouns, despite their components.

Some compounds have more than two component words. These are formed by successively combining words into compounds, e.g. pick-up truck, formed from pick-up and truck , where the first component, pick-up is itself a compound formed from pick and up. Other examples are ice-cream cone, no-fault insurance and even more complex compounds like top-rack dishwasher safe.

There are a number of subtypes of compounds that do not have to do with part of speech, but rather the sound characteristics of the words. These subtypes are not mutually exclusive.

Rhyming compounds (subtype of compounds)

These words are compounded from two rhyming words. Examples:

There are words that are formally very similar to rhyming compounds, but are not quite compounds in English because the second element is not really a word—it is just a nonsense item added to a root word to form a rhyme. Examples:

This formation process is associated in English with child talk (and talk addressed to children), technically called hypocoristic language. Examples:

bunnie-wunnie

Henny Penny

snuggly-wuggly

Georgie Porgie

Piggie-Wiggie

Another word type that looks a bit like rhyming compounds comprises words that are formed of two elements that almost match, but differ in their vowels. Again, the second element is typically a nonsense form:

Derivation Derivation is the creation of words by modification of a root without the addition of other roots. Often the effect is a change in part of speech.

Affixation (Subtype of Derivation)

The most common type of derivation is the addition of one or more affixes to a root, as in the word derivation itself. This process is called affixation, a term which covers both prefixation and suffixation.

Blending

Blending is one of the most beloved of word formation processes in English. It is especially creative in that speakers take two words and merge them based not on morpheme structure but on sound structure. The resulting words are called blends.

Usually in word formation we combine roots or affixes along their edges: one morpheme comes to an end before the next one starts. For example, we form derivation out of the sequence of morphemes de+riv+at(e)+ion. One morpheme follows the next and each one has identifiable boundaries. The morphemes do not overlap.

But in blending, part of one word is stitched onto another word, without any regard for where one morpheme ends and another begins. For example, the word swooshtika ‘Nike swoosh as a logo symbolizing corporate power and hegemony’ was formed from swoosh and swastika. The swoosh part remains whole and recognizable in the blend, but the tika part is not a morpheme, either in the word swastika or in the blend. The blend is a perfect merger of form, and also of content. The meaning contains an implicit analogy between the swastika and the swoosh, and thus conceptually blends them into one new kind of thing having properties of both, but also combined properties of neither source. Other examples include glitterati (blending glitter and literati) ‘Hollywood social set’, mockumentary (mock and documentary) ‘spoof documentary’.

The earliest blends in English only go back to the 19th century, with wordplay coinages by Lewis Carroll in Jabberwocky. For example, he introduced to the language slithy, formed from lithe and slimy, and galumph, (from gallop and triumph. Interestingly galumph has survived as a word in English, but it now seems to mean ‘walk in a stomping, ungainly way’.

Some blends that have been around for quite a while include brunch (breakfast and lunch), motel (motor hotel), electrocute (electric and execute), smog (smoke and fog) and cheeseburger (cheese and hamburger). These go back to the first half of the twentieth century. Others, such as stagflation (stagnation and inflation), spork (spoon and fork), and carjacking (car and hijacking) arose since the 1970s.

Here are some more recent blends I have run across:

mocktail (mock and cocktail) ‘cocktail with no alcohol’

splog (spam and blog) ‘fake blog designed to attract hits and raise Google-ranking’

Britpoperati (Britpop and literati) ‘those knowledgable about current British pop music’

Clipping Clipping is a type of abbreviation of a word in which one part is ‘clipped’ off the rest, and the remaining word now means essentially the same thing as what the whole word means or meant. For example, the word rifle is a fairly modern clipping of an earlier compound rifle gun, meaning a gun with a rifled barrel. (Rifled means having a spiral groove causing the bullet to spin, and thus making it more accurate.) Another clipping is burger, formed by clipping off the beginning of the word hamburger. (This clipping could only come about once hamburg+er was reanalyzed as ham+burger.)

Acronyms

Acronyms are formed by taking the initial letters of a phrase and making a word out of it. Acronyms provide a way of turning a phrase into a word. The classical acronym is also pronounced as a word. Scuba was formed from self-contained underwater breathing apparatus. The word snafu was originally WW2 army slang for Situation Normal All Fucked Up. Acronyms were being used more and more by military bureaucrats, and soldiers coined snafu in an apparent parody of this overused device. Sometimes an acronym uses not just the first letter, but the first syllable of a component word, for example radar, RAdio Detection And Ranging and sonar, SOund Navigation and Ranging. Radar forms an analogical model for both sonar and lidar, a technology that measures distance to a target and and maps its surface by bouncing a laser off it. There is some evidence that lidar was not coined as an acronym, but instead as a blend of light and radar. Based on the word itself, either etymology appears to work, so many speakers assume that lidar is an acronym rather than a blend.

A German example that strings together the initial syllables of the words in the phrase, is Gestapo , from GEheime STAats POlizei ‘Sectret State Police’. Another is Stasi, from STAats SIcherheit ‘State Security’. Acronyms are a subtype of initialism. Initialisms also include words made from the initial letters of a Phrase but NOT pronounced as a normal word — it is instead pronounced as a string of letters. Organzation names aroften initialisms of his type. Examples:

NOW (National Organization of Women)

US or U.S., USA or U.S.A. (United States)

UN or U.N. (United Nations)

IMF (International Monetary Fund)

Some organizations ARE pronounced as a word: UNICEF

MADD (Mothers Against Drunk Driving)

The last example incorporates a meaning into the word that fits the nature of the organization. Sometimes this type is called a Reverse Acronym or a Backronym.

These can be thought of as a special case of acronyms.

Memos, email, and text messaging (text-speak) are modes of communication that give rise to both clippings and acronyms, since these word formation methods are designed to abbreviate. Some acronyms:

NB — Nota bene, literally ‘note well’. Used by scholars making notes on texts. (A large number of other scholarly acronyms from Latin are used, probably most invented in the medieval period or Renaissance, not originally in Latin)

BRB — be right back (from 1980s, 90s)

FYI — for your information (from mid 20th century)

LOL — laughing out loud (early 21st century) — now pronounced either /lol/ or /el o el/; has spawned compounds like Lolcats).

ROFL — rolling on the floor laughing

ROFLMAO — rolling on the floor laughing my ass off

Reanalysis

Sometimes speakers unconsciously change the morphological boundaries of a word, creating a new morph or making an old one unrecognizable. This happened in hamburger, which was originally Hamburger steak ‘chopped and formed steak in the Hamburg style, then hamburger (hamburg + er), then ham + burger

Folk etymology

A popular idea of a word’s origin that is not in accordance with its real origin.

Many folk etymologies are cases of reanalysis in which the word is not only reanalysis but it changes under the influence of the new understanding of its morphemes. The result is that speakers think it has a different origin than it does.

Analogy

Sometimes speakers take an existing word as a model and form other words using some of its morphemes as a fixed part, and changing one of them to something new, with an analogically similar meaning. Cheeseburger was formed on the analogy of hamburger, replacing a perceived morpheme ham with cheese. carjack and skyjack were also formed by analogy.

Novel creation

In novel creation, a speaker or writer forms a word without starting from other morphemes. It is as if the word if formed out of ‘whole cloth’, without reusing any parts.

Some examples of now-conventionalized words that were novel creations include blimp, googol (the mathematical term), bling, and possibly slang, which emerged in the last 200 years with no obvious etymology. Some novel creations seem to display ‘sound symbolism’, in which a word’s phonological form suggests its meaning in some way. For example, the sound of the word bling seems to evoke heavy jewelry making noise. Another novel creation whose sound seems to relate to its meaning is badonkadonk, ‘female rear end’, a reduplicated word which can remind English speakers of the repetitive movement of the rear end while walking.

Creative respelling

Sometimes words are formed by simply changing the spelling of a word that the speaker wants to relate to the new word. Product names often involve creative respelling, such as Mr. Kleen. © Suzanne Kemmer

Word Forms

Recognize meanings of noun, verb, adjective and adverb forms

Multiple Word Forms vs. Limited Word Forms

Imagination is an example of a noun with verb, adjective and adverb word forms. All share the meaning «the forming of images in the mind that are not actually present». Additional word definitions vary slightly and keep close to the central meaning.

His writing was

| MULTIPLE WORD FORMS, SHARED MEANING | |

|---|---|

| CONTEXT | WORD FORM |

| NOUN | |

| ADJECTIVE | |

| ADVERB | |

Revolution is an example of a word that has some but not all four word forms. Notice that the adjective and adverb forms have meanings that depart from «rebellion to authority» and take on a meaning closer to «rebellion of mind or feeling».

The singer sang about social

revolted. revolt (V) «rebelled «

revolutionary. (innovative, rebellious)

revolting¹. (disgusting or rebellious)

—none— «in a revolutionary manner»

imagination (N) — the natural ability of imagining, or of forming mental images or concepts of what is not actually present to the senses; the word can be both a count noun (He had quite an imagination! ) when speaking specifically and a noncount noun (He had imagination.) when speaking in general.

rebel (N) — go against or take action against a social convention (the usual way of doing things) or a government or institution

revolt (V) — (1) rebel or break away from authority; (2) turn away in mental rebellion, disgust; (3) rebel in feeling; (4) feel horror. (at) He revolted at seeing their brutality.

¹revolting (Adj) — (1) disgusting, repulsive, distasteful, awful; (2) rebellious They are revolting. (unclear meaning)

revolution (N) — (1) an overthrow of a government, a rebellion; (2) a radical change in society and the social structure; (3) a sudden, complete or marked change in something; (4) completion of a circular movement, one turn.

revolutionary (Adj) — (1) a sudden complete change; (2) radically new or innovative; outside or beyond established procedure, principles; (3) related to a country’s revolution (period); (3) revolving, turning around like a record

«John Lennon» by Charles LeBlanc licensed by CC BY-SA 2.0 (size changed and «poster» filter applied)

Word Form Entry into English

Source of word and the addition of other forms

Word Forms

Historically, a word entered the English language, or was borrowed, primarily as one form—a noun, a verb or an adjective. In time, additional forms were added to the original word so that it could function in other ways. The table below includes words and their approximate entry dates as well as additional word forms and their appearance dates.

There is no formal or exact way of knowing which suffix to add when changing a word from one form to another. The methods of adding suffix forms vary. Some patterns exist, depending on whether the origin of the word is M >uninterested, disinterested and not interested.

A word may not have all four word forms. For example, the noun fun is w >fun (1675-85) and funny (1750-60). But usage of fun as a verb is rare and as an adverb is non-existent.

A word may have two similar forms that co-exist. For example, a word may enter English or be borrowed more than once. The noun chief (leader) entered into usage in M >chef (head cook) from French in 1835-45.

A word may be newly coined (made up) and not yet have other forms. For example, the word selfie is w >twerk can be used as a verb, but can one say a twerk (noun), twerky (adjective) or twerkily (adverb)?

Bright Hub Education

Word Formation

Word formation occurs when compounding, clipping or blending existing words to create new words. Below we will cover the definition of these terms and give you several examples of each.

Compounding Words

Compounding words are formed when two or more lexemes combine into a single new word. Compound words may be written as one word or as two words joined with a hyphen. For example:

- noun-noun compound: note + book → notebook

- adjective-noun compound: blue + berry → blueberry

- verb-noun compound: work + room → workroom

- noun-verb compound: breast + feed → breastfeed

- verb-verb compound: stir + fry → stir-fry

- adjective-verb compound: high + light → highlight

- verb-preposition compound: break + up → breakup

- preposition-verb compound: out + run → outrun

- adjective-adjective compound: bitter + sweet → bittersweet

- preposition-preposition compound: in + to → into

Compounds may be compositional, meaning that the meaning of the new word is determined by combining the meanings of the parts, or non-compositional, meaning that the meaning of the new word cannot be determined by combining the meanings of the parts. For example, a blueberry is a berry that is blue. However, a breakup is not a relationship that was severed into pieces in an upward direction.

Compound nouns should not be confused with nouns modified by adjectives, verbs, and other nouns. For example, the adjective black of the noun phrase black bird is different from the adjective black of the compound noun blackbird in that black of black bird functions as a noun phrase modifier while the black of blackbird is an inseparable part of the noun: a black bird also refers to any bird that is black in color while a blackbird is a specific type of bird.

Clipping Words

Clipping is the word formation process in which a word is reduced or shortened without changing the meaning of the word. Clipping differs from back-formation in that the new word retains the meaning of the original word. For example:

- advertisement – ad

- alligator – gator

- examination – exam

- gasoline – gas

- gymnasium – gym

- influenza – flu

The four types of clipping are back clipping, fore-clipping, m >gas from gasoline. Fore-clipping is removing the beginning of a word as in gator from alligator. M >flu from influenza. Complex clipping is removing multiple parts from multiple words as in sitcom from situation comedy.

Blending Words

Blending is the word formation process in which parts of two or more words combine to create a new word whose meaning is often a combination of the original words. Below are examples of blending words.

- advertisement + entertainment → advertainment

- biographical + picture → biopic

- breakfast + lunch → brunch

- chuckle + snort → chortle

- cybernetic + organism → cyborg

- guess + estimate → guesstimate

- hazardous + material → hazmat

- motor + hotel → motel

- prim + sissy → prissy

- simultaneous + broadcast → simulcast

- smoke + fog → smog

- Spanish + English → Spanglish

- spoon + fork → spork

- telephone + marathon → telethon

- web + seminar → webinar

Blended words are also referred to as portmanteaus.

Word Formation Sample Downloads

For more complete lists of English words formed through compounding, clipping, and blending, please download the following free printable vocabulary lists:

Learning Vocabulary With Word Forms

How to Use Word Forms to Improve and Broaden Your English Vocabulary

- TESOL Diploma, Trinity College London

- M.A., Music Performance, Cologne University of Music

- B.A., Vocal Performance, Eastman School of Music

There are a wide variety of techniques used to learn vocabulary in English. This learning vocabulary technique focuses on using word forms as a way to broaden your English vocabulary. The great thing about word forms is that you can learn a number of words with just one basic definition. In other words, word forms relate to a specific meaning. Of course, not all of the definitions are the same. However, the definitions are often closely related.

Start off by quickly reviewing the eight parts of speech in English:

Examples

Not all eight parts of speech will have a form of each word. Sometimes, there are only noun and verb forms. Other times, a word will have related adjectives and adverbs. Here are some examples:

Noun: student

Verb: to study

Adjective: studious, studied, studying

Adverb: studiously

Some words will have more variations. Take the word care:

Noun: care, caregiver, caretaker, carefulness

Verb: to care

Adjective: careful, careless, carefree, careworn

Adverb: carefully, carelessly

Other words will be especially rich because of compounds. Compound words are words made up by taking two words and putting them together to create other words! Take a look at words derived from power:

Noun: power, brainpower, candlepower, firepower, horsepower, hydropower, powerboat, powerhouse, powerlessness, powerlifting, powerpc, powerpoint, superpower, willpower

Verb: to power, to empower, to overpower

Adjective: empowered, empowering, overpowered, overpowering, powerable, powered, powerful, powerless

Adverb: powerfully, powerlessly, overpoweringly

Not all words have so many compound word possibilities. However, there are some words that are used to construct numerous compound words. Here’s a (very) short list to get you started:

Exercises for Using Your Words in Context

Exercise 1: Write a Paragraph

Once you’ve made a list of a few words, the next step will be to give yourself the opportunity to put the words you’ve studied into context. There are a number of ways to do this, but one exercise I especially like is to write an extended paragraph. Let’s take a look at power again. Here’s a paragraph I’ve written to help me practice and remember words created with power:

Writing a paragraph is a powerful way to help you remember words. Of course, it takes plenty of brainpower. However, by writing out such a paragraph you will empower yourself to use this words. For example, you might find creating a paragraph in powerpoint on a PowerPC takes a lot of willpower. In the end, you won’t feel overpowered by all these words, you’ll feel empowered. No longer will you stand there powerlessly when confronted with words such as candlepower, firepower, horsepower, hydropower, because you’ll know that they are all different types of power used to power our overpowering society.

I’ll be the first to admit that writing out a paragraph, or even trying to read such a paragraph from memory might seem crazy. It certainly isn’t good writing style! However, by taking the time to try to fit as many words made up with a target word you’ll be creating all sorts of related context to your word list. This exercise will help you imagine what type of uses can be found for all these related words. Best of all, the exercise will help you ‘map’ the words in your brain!

Exercise 2: Write Sentences

An easier exercise is to write out individual sentences for each word in your list. It’s not as challenging, but it’s certainly an effective way to practice the vocabulary you’ve taken the time to learn.

Оценка статьи:

Загрузка…

Adblock

detector

| LIMITED WORD FORMS, VARYING IN MEANING | |

|---|---|

| CONTEXT | WORD FORM |

| NOUN | |

| ADJECTIVE | |

| ADVERB | |

There

are 2 main types of word form derivation:

1)

Those limited to change in the body of the word without help axulary

words (sensetic types).

2)

Those enplane the use of axulary (analytical).Besides there are a few

special cases of different forms of a word been derived from all

together different stamps.

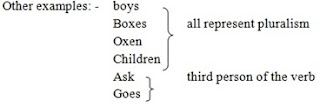

a)

Senstic types The

number of morphemes used for deriving word forms in modern English is

very small. Much smaller then in Latin, German, Ukrainian or

Russian.They may be annumerated in a very short space. There ia the

ending –s(-es) with 3 variants of pronunciation used to form the

plural of the noun. And the ending –en, (-ren) used for the same

propers in one or two words each (oxen, children).There is the ending

–is with the same 3 variants of pronunciation as for the plural:

ending used to form what is a generaly term case of nouns.For

adjectives

there are the endings: -er, -est for the degress of comparatives.For

verbs

the number of morphemes used to derived their forms is slitly

greater. There is the ending –s(-es) for the 3-d person singular

Pr. Ind. With the same 3 v. of pronouns.The ending –d(-ed) for the

Past Tense of certain verbs with the 3 v. of pronouns.The ending

–d(-ed) for the Participle ІІ of certain verbs. The ending –ing

for the Participle І and for the Gerund.The total number of

morphemes used to derive forms of words is 10 or so. It is mush less

then the number found in L. of a mainly sensetical structure.

b)

sound alternations (чредование гласных). By

sound alternation are can understand a way of expression grammatical

categories wich consist in changing a sound inside the root. These

method apperes in modern English in nouns then the root vowel [ ] of

a singular form man

is

changed into [e] to form the plural form –men

or similarly. The root vowel on of mouth

is changed into –i

in mice.

These method is much more used in verb such as write–wrote-written;

meet-met-met.

On

the whole vowel altonation does play some part among the means of

expressing the grammatical categories.

c)

analytical (вспомаг. глаголы) Analytical

types consists in using a word to express some grammatical category

of another word.The verbs: have, be, do – have no lexical meanings

of their own in these cases. The lexical meanen of the formations

presides in the Participle or Infinitive following the verb: have,

be, do.Some analytical types has been expressed about the formation

shall invite and will invite. There is a view that shall/will have a

lexical meanings: consides shall/will as verbs serving the form the

Future Tence of other verbs. Thus have, be,do,shall,will are what we

called axulary verbs. As such they constitute to typical feature of

the analytical structure of modern English. While the existans of

analytical forms of the Eng. verb can’t be destitute.The existents

of some forms in adjectives and adverbs is not nowadays universally

recognized. The question whether such formations as more vived the

most vived or more vivedly most vivedly are not analitical forms of

degress of comparatives.If these formations are recognized as

analytical forms of degrees of compression the words more/most have

to be numbered among the analytical means of morphology.

d)

suplative formation Besides

the sensetical and analytical means of building word in modern Eng.

There is another way of building them which stands quite a part and

is found in a very limited.By a sypletive formation one can mean

building a form of a word from an alltogether different steam (the

verb go

with its past Tence went;

the personal pronoun I

with

it’s objective case form me).In

the morphological system of modern Eng. suplative formation are very

insignificant elements but they consem a few very widly used words

among adjectives, pronouns and verbs.

Соседние файлы в предмете [НЕСОРТИРОВАННОЕ]

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

In linguistics, word formation is the creation of a new word. Word formation is sometimes contrasted with semantic change, which is a change in a single word’s meaning. The boundary between word formation and semantic change can be difficult to define: a new use of an old word can be seen as a new word derived from an old one and identical to it in form.

Word Formation tries to explain the processes through which we can create new word forms. We’ve already seen some of these at work when we looked at morphemes and word classes, but now we’ll investigate them a little more closely, initially using exploratory methods again, rather than just looking at long lists of morphemes and listing their functions.

This is the field or branch of morphology which studies different principles or processes which govern the conservation or formation of words in a particular language. I.e. it refers to the processes by which new words are formed or built in a particular language.

This process involves morphological processes (then formation of words through combinations of morphemes together with other different processes.

The process of word formation may involve the process whereby roots or stems received inflectional or derivational element (affixes) in order to form the new words.

NB: The roots, stems inflectional or derivational elements are all technique termed as morphemes

MORPHOLOGY

This is a component of grammar (sub branch) of linguistics which deals with the study of morphemes and their difference forms (Allomorphs) and how these units combine together in the formation of words. It also studies the structure and arrangement of words in the dictionary i.e. Morphology is the study of word formation and dictionary use.

DEFINITIONS OF KEY WORDS

1. Morpheme

This is the smallest grammatical or lexical unit in the structure of a language which may form a word or part of a word

E.g. nation — national

International

Internationally

Nationalization

Kind — kindness

Unkind

Unkindness

Take — takes

Taken

Taking

Discuss — discussion

Discussions

A morpheme may represent the lexical meaning or grammatical function.

2. Word

This is the minimal or smallest unit in the structure of a sentence in any language which may constitute on utterance or sentence on its own.

The word is usually formed by either one or several morphemes out it is the smallest unit in the sentence structure.

E.g. Yesterday I met him at Tabata- 6 words

We can words in a sentence and morphemes in a word

3. Stem

Is that part of a word that is in existence before any inflectional affixes have been added.

Or, Is that part of the word that inflectional affixes can be attached to.

For example:

— «cat» can take inflectional morpheme-‘S’

— «Worker» can take inflectional morpheme-‘S’

— «Winne» can take inflectional morpheme-‘S’

— «Short» can take inflectional morpheme-‘er’

— «friendship» can take inflectional morpheme-‘S’

— A stem is a root or roots of the word together with any derivation affixes to which inflectional affixes are added.

— A stem consists minimally of a root but may be analyzable word into a root plus derivation morphemes

4. Base

Is any unit whatsoever to which affixes of any kind can be added.

For example; in the word «playful»

‘play’ is a root and also a base

In the word ‘playfulness’ the root is still «play» but the base is ‘playful’

— «Instruct» is the base for forming instruction, instructor and re-instruct

NB: All roots can be bases but not all bases are roots.

1. Write ten words which you think are bases but they are not roots

2. Identify the inflectional affixes, derivational affixes, roots, base and stems in the following words faiths, faithfully, unfaithful, faithfulness, bookshops, window-cleaners, hardships

5. Root

This is a basic part of a word which normally carries lexical meaning corresponding to the concept, object or idea and which cannot be split into further parts

Roots in many languages may also be joined to other roots or take affixes or combing forms

E.g. Man manly, house hold, big

6. Affix

This is a morpheme, usually grammatical which is attached to another morpheme (stem) in the formation of a new word which may change the meaning, grammatical category or grammatical form of the stem.

E.g. Beautiful Mismanagement Disconnect

The affix maybe added either before, with or after the stem thus are three types of affixes.

i. Prefix

This is the affix which is added before the stem

E.g. Disconnect

Illogical

Unhappy

Empower

ii. Infix

This is the affix that is added within the stem. Thus type of affix is rare to be found in English words

E.g. meno — meino

iii. Suffix

This is the affix that is added after the stem.

E.g. Mismanagement

Beautiful

Dismissal

Kingdom

7. Allomorph

This refers to any of the difference forms of the same morpheme root they all represent the past participle (grammatical function)

CLASSIFICATION OF MORPHEMES

The morphemes are classified into several categories basing on several factor such as:-

Occurrence, meaning and function

There are two major types of morphemes

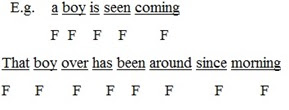

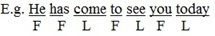

(i) Free morpheme

This is the morpheme that can stand or occur alone (on its own) as a separate word in the structure of a sentences in any language.

The free morpheme includes all parts of speech i.e. Nouns, Verbs, adjectives, adverbs, pronouns, prepositions, conjunctions, interjections, articles

The free morpheme is further divided into two categories

(a) Lexical morpheme

This is the type of frees morpheme which occurs on its own and carries a content of the message being conveyed i.e. It is the free morpheme which represents the actual lexical meaning of the concept, idea, object or action.

The lexical morphemes include the major word classes such as Noun, verbs (main verb), adjective and adverb.

E.g. House

Attend

Large

Tomorrow

(b) Functional morpheme / grammatical morpheme

This is the free morpheme which can stand alone as a separate word in a sentence but does not represent the actual lexical meaning of the concept, idea, object or action – it has little meaning when used alone and thus it usually occurs together with the lexical morpheme in order to give the lexical meaning

The functional morphemes includes the minor word classes such as pronouns, prepositions, conjunctions, interjections and articles, auxiliary verbs etc

(ii) Bound morpheme

This is the morpheme which can not normally stand alone as a separate word in the sentence structure as it is attached to another morpheme (lexical) free morpheme in the formation of the new word.

The Bound morpheme represents grammatical function such as word category tense aspect, person, number, participle, comparison etc.

Example ment, ism represents a noun, aly represent.

Adverb

Tense – ed, d, voice, number

Person – es

Aspect – ing – progressive aspect

Comparison – er, est

The Bound morpheme is farther divided in to two categories.

(a) Derivation morpheme

This is the bound morpheme which is used to form or make new words with different meanings and grammatical categories or class from the stem i.e. It is the morpheme which when added to the stem it changes the meaning and / or the word class of grammatical category of stem/ base Example unhappy, illogical, impossible, empower

National – noun to adjective

Derivation morpheme may occur either before or after or both before and after the stem in the formation of the new words i.e. they may occur either as prefixes or affixes example management, mismanage, mismanagement.

The derivation morpheme may also change the sub classification of the same word class such as concrete noun into abstract noun e.g. Kingdom, friendship, leadership, membership

Deviation morphemes are also used as indicators of word category example simplicity, modernize dare indicators of verb by indicator of adverbs.

(b) Inflectional morpheme

This is the type of bound morpheme which is not used to produce or form different words with different meaning but rather it is used to change grammatical form of the state i.e. Inflectional morpheme doesn’t change the meaning or word class but it only changes grammatical form of the sentence which represent grammatical function such as to mark the verb for tense aspect, participle voice etc

Example finished, Lorries, oxen

Past tense – finished

Past participle – proven

Number – Lorries, oxen, children

Inflectional morpheme also marks nouns and number.

They mark adverb and adjectives for comparison

E.g. smaller, smallest

The inflectional morpheme occur only after the stem (they are suffix)

FUNCTION OF MORPHEMES

The morphemes are analyzed as having three major functions that are directly linked with their types.

The following are the functions of morphemes:-

1. The morpheme (free morphemes) are used to form the bases or roots of the words i.e. a single free morpheme, lexical or functional forms the base or root of a word.

This function is therefore called

Base – form function

E.g. Tree, after, along

2. The morphemes (derivation bound morphemes) are used to change the lexical meaning and / or the grammatical category of the stem.

This function is called derivation function

E.g.

Dis

unity,

il

legal, beautif

ul

, quick

ly

, modern

ize

3. The morphemes (inflectional morphemes) are used to change the grammatical form or function of the stem without changing the meaning or word class.

This function is known as inflectional function

TASK

Read the following passage and answer the following question

A thick vegetation cover, such as tropical forests , acts as protection against physical weathering and also helps to slow the removal of the weathered layer in deserts and high mountains the absence of the vegetation accelerates the rate of weathering plants and animals, however, play a significant part in rock destruction, notably by chemical decomposition through the action of organic acidic solution the acids develop from water percolation through party decayed vegetation and animal matter.

Question

1. Identify

I. 7 lexical morphemes

II. 5 derivation morphemes

III. 2 inflectional morphemes

PROCESSES OF WORD FORMATION IN ENGLISH LANGUAGE

The formation of words in English language is archived in several processes or ways. These processes fall into two major categories

(i) The major processes which includes affixation compounding, Conversion and reduplication.

(ii) The minor processes which includes clipping Blending, Acronym, Borrowing, Back formation, Onomatopoeia, Coining/ coinage

I) The major processes of word formation

(a) AFFIXATION

The process of word formation whereby new words are formed by attaching or adding the affixes (prefix, infix or suffix) to the stem.

E.g. Shortly – suffix

Unusual – prefix

Belonging – suffix

Inhuman – prefix

Dismissal — suffix

(I) Prefixation

This is the process of forming new words by adding affixes before the stem/root. For example dislike , unhappy, amoral, decolonise, redo.

Classification of Prefix

Prefix are classified into several categories basing on the meaning they give when added to the stem

i. Negative prefixes

These give the meaning of “NOT” “the opposite of” or “lack of”

E.g.

I

nformal –

ir

relevant

Impossible – illegal

Immobile – illogical

Irregular – disobey

Disadvantage — amoral

Apolitical

ii. Restorative prefixes

These give the meaning of “Reverse an action”

E.g Undress – deforest

Uncover – depopulate

Disconnect – devalue

Disorganized

Decolonize

iii. Pejorative prefixes

These give the meaning of “unless. False, fake, unimportant. Wrong, badly or bad”

E.g. Malnutrition – pseudo name

Malpractice – pseudo intellectual

Misconduct – pseudo scientists

Mismanage

Misbehave

iv. Prefixes of degree or size

These express degree or size in terms of quality or quantity.

E.g. Arch (supreme or highest in rank)

Super (above or better)

Sir (over and above) e.g. Sir name

Sub (lower or less than) e.g. Substandard, subconscious

Over (too much) e.g. Over doss, over it, over confident

Under (too little) e.g. under paid, under look, under cook

Hyper (extremely or beyond) e.g. Hyper actives, Hyper sensitive

Ultra (extremely or beyond) e.g. Ultra modern, ultrasound

Mini (small) e.g. Mini bus, mini skirt

v. Prefixes of altitude

These include “Co-“(with or joined)

E.g. Co-operate, co- education, co- exist. “Counter” (in opposition to”) e.g. Counter attack, counter- revolution, and counter act

“Anti” (against) e.g. Antivirus, anticlockwise, anti body

“Pro” (instead of or on the side of) e.g. Pronoun, pro capitalism, Pro multiparty.

vi. Locative prefixes

These indicate location

E.g. Super (over or above) superstructure, super building, super imposed

Inter (between or among) international, inter school

Trans (across) Trans Saharan, trans plant, Trans Atlantic

vii. Prefixes of time and order

These include “fore” (before, front, first) e.g. Foreground, fore legs, fore knowledge, fore head

Pre – (before) e.g. Pre-mature

Pre- independence

Pre- form one

Pre- National

Pre- judge

Pre- war

Post – (after) e.g. Post- graduate

Post – independence

Post-election

Ex – (former) e.g. Ex – president

Ex – wife

Ex – husband

Ex – soldier

Re – (again or back) e.g.Re – write

Re call

Re evaluate

viii. Number prefixes

These show number

Uni-/ Mono – (means one) e.g.Uni- cellular

Mono party

Monolingual

Monocotyledon

Monosyllabic

Bi -/ Bi – (means two, double or twice) e.g. Bilingua

Bicycle

Ditransitive

Dicotyledon

Bi- annual

Tri (three) e.g. Triangle

Tricycle

Trilateral

Multi/ poly (many) e.g. Polyandry

Polygamy

Multi lingua

Multiparty

Multi disciplinary

ix. Conversion prefixes

Prefixes used to change a word from noun/adjective to verb

En – (make or become)

e.g. Enslave

Enlarge

Ensure

Enforce

Enrich

Enlightened

Be – (make or become)

e.g. Befriend

Be calm

Be witch

-A- (be or become)

e.g. a live

A sleep

A rise

x. Other prefixes

— Auto (self) – Auto biography

Autograph

Autocracy

— Neo (new or revived) e.g. Neo- colonialism

Neo-man

-Pan (all or worldwide) e.g. Pan-africanism

-Proto (original) e.g. Proto Bantu

Proto language

Proto type

-Semi (half) e.g. Semi-circle

Semi- hemisphere

Semi- final

Semi-model

TASK

1. Provide the meaning of the following prefixes and provide three examples of words/roots/stem which can be use these prefixes.

i) Sur —

ii) Proto —

iii) Hyper —

iv) Dis —

v) Neo —

2. With examples differentiate between pejorative prefixes and locative prefixes.

3. Use appropriate prefix(es)in each of the following words

i) Charge

ii) Type

iii) possible

iv) Navigation

v) Ability

4. i) Give three examples of reversative prefixes

ii) Write three examples of the prefix poly_

iii) What is the difference of the prefix «Un» in unhappy, unkind and in uncover, untie

(II) Suffixation

Is the process of adding morphemes after a system/root. So as to form new word. Unlike prefixation, suffixes frequently alter the word class of a root/stem.

Classification of suffix

The suffixes are classified according to the class of the new word formed after the addition of the suffixes.

There are four major types of suffixes

i) — Noun suffixes

ii) — Adjective suffixes

iii) — Adverb suffixes

iv) — Verb suffixes-let (small)

Noun Suffixes

are the suffixes added to the stem or bases of different word classes in the formation of the new word that are noun by category.

This falls into four categories;

(a) Noun to noun suffixes

— star (engaged in or belongs to)

E.g. – Young –star

Gang-star

— eer (engaged in or belongs to)

E.g. Engineer

Profiteer

Racketeer

— let (small)

E.g. Booklet

Leaflet

Piglet

— ette (small)

E.g. Kitchenette

Cigarette

Statuette

— ess (small) e.g. Lioness

Actress

Princess

— hood (in the state or status of) e.g. Brotherhood

Manhood

Neighborhood

Youth hood

Adulthood

— Ship (in the state or status of) E.g. Friendship

Relationship

— Dom (in the condition) E.g. Kingdom

Freedom

Boredom

Wisdom

— cracy (system of government) E.g. Bureaucracy

Democracy

— ery (behavior of or place an ac

E.g. Slavery

Machinery

Peasantry

Carpentry

Concrete – Abstract

(b) Noun to Adjective suffixes are the suffixes added to

— ist (member of) e.g. Socialist

Idealist

Capitalist

Ratio list

— ism (attitude or political movement)

E.g. Idealism

Communism

— ness (quality) or state

E.g. Happiness

Cleverness

— ity (state or quality) e.g. Stupidity

Ability

Salinity

(c) Verb to Noun suffixes

— er (instrumental or a genitive) e.g. Player

Reader

Writer

Farmer

Leader

— or (“ ) e.g. Actor

Investigator

Incubator

Insulator

— al (action of) e.g. Arrival

Dismissal

Withdrawal

Proposal

— age (an activity or)

E.g. Drainage

Marriage

Passage

Leakage

— ment (state or action of)

E.g. Government

Treatment

Achievement

Improvement

— ant (instrumental or adjective) E.g. Assistant

-ee (passive receiver) e.g. Employee

Payee

Trainee

Appointee

Interviewee

— (a) tion (state or action)

E.g. organization

Examination

Discussion

Globalization

Penetration

(ii) Adjective suffixes

They are used to change the bases of different word classes such as noun or verbs in order to form the new words that are Adjective by class.

(a) Verb to Adjective suffixes

— ive (which) e.g. Active

Respective

Comparative

Collective

— able /-ible E.g. Manageable

Sensible

Movable

Honorable

Noun to Adjective suffixes

— al (of or with) e.g. National

Accidental

Criminal

Historical

— (ii) an (member of) e.g. Tanzanian

Canadian

— ful (having or with)

E.g. Beautiful

Wonderful

— less (without)

E.g. Childless

Speechless

Harmless

Hopeless

Useless

— ly (having a quality of)

E.g. Manly

Friendly

Cowardly

— ish (belong to or having the character of)

E.g. Selfish

Turkish

Irish

Swedish

— ous (with or worth) e.g. Dangerous

Famous

— ese (a member or citizen of)

E.g. Chinese

Congolese

Japanese

— y (like, with or cover with)

E.g. Sandy

Muddy

Sugar

Healthy

Creamy

Hairy

— like (having a quality or behavior like)

E.g. Childlike

Fingerlike

(iii) Verb suffixes

These are the suffixes added to the stems or roots of Noun or adjectives to from the new words which are verbs by class.

These are three types of verb suffixes

-ify (cause or make) e.g. Identify

Simplify

Notify

Classify

Purify

-en (cause or make) e.g. Widen lengthen

Sharpen strengthen

Weaken

Sadden

Threaten

-ize/ — ise ( “ ) e.g. Apologize

Colonize

Socialize

Formalize

(iv) Adverb suffixes

These are the suffixes which when added to the roots or stems they produce a new word which is an adverb by class

-ly (in the manner of) e.g. quickly

Slowly

Quietly

Happily

Gradually

-ward (in the manner of or in the direction of)

E.g. Backward

Onwards

Inwards

Downwards

Upwards

-wise (as far as or in the manner of)

E.g. Education wise

Clockwise

Cultural wise

Political wise

TASK

1. Form verbs from the following words; family, type, popular, clear.

2. Form adjectives from the following words;expression, problem, progress, crime, courage.

3. With examples differentiate prefixes from suffixes

(b) COMPOUNDING

This is the process of words formation whereby two or more lexical morphemes are joined or combined together to form a new single word.

E.g. Classroom

Earth quake

Girlfriend

Tea spoon

Table mat

Easy-going

Washing-machine

NB: The new words formed as a result of the process of compounding are technique known as compound words or compounds.

Classification of compound words

The compound words are classified basing on two aspects;

i) The way they are written

ii) According to the meaning

i) The way they are written

— Solid/closed compound

These are the compound words that are written without leaving any space or gap between the bases.

E.g. Classroom

Teaspoon

Earthquake

Wallpaper

Textbook

Payphone

— Hyphenated compounds

These are the compound words that the written with the hyphen separating the two bases.

E.g. Fire-escape

High-grade

Colour-blind

Brother-in-law

Machine-gun

— Open Compounds

These are the compound words that are written by leaving the space (gap) between the two bases.

E.g. Sewing machine

Town planning

Tape measure

Baking powder

Washing machine

ii) According to the meaning

Transparent compounds

These are the compound whose meanings reflect the meaning of separate bases i.e. the compounds whose meanings are directly derived or related to the meaning of the separate bases which make them up.

E.g. Classroom

Girlfriend

Earthquake

Teaspoon

Washing machine

Opaque Compounds

These are the compounds whose meanings differ from the meanings of separate bases i.e. the compounds whose meanings are not derived or not directly related with the meanings of separate bases which make up

E.g. Honey moon wide spread

Daily word blue berry

Pass word call right

Sweet heart cow boy

Hot cake

Home sick

Sugar mummy

Day dream

Bahrain

These are the compound words whose meanings reflect the physical features or appearance of a person or object being reflected to.

E.g. Blackboard

White fluid

Block head

Feature weight

Red – eyed

Identification of the compound words

There are three ways of identifying the compound words

i. Through the entry in the dictionary

i.e. any compound word should occupy its own entry in the dictionary. It should be regarded as an independent word in the dictionary.

E.g. Bedroom

Classroom

National park

ii. Through the word class or category

i.e. Each compound word has its own class different from other word classes of the words constituting the compound

E.g. play boy – Noun

Play -Verb

Boy – noun

Madman – noun

Mad – adjective

Man – noun

Colour blind – adjective

Colour — noun

Blind — adjective

Well – known – adjective

Well – adverb

Known – verb

Through the meaning i.e. some words retain their original meaning after the combination but some of the words convey the meaning that are totally different from the meaning of the original word

E.g. Green fly, Sweet heart, Pass word

(c) CONVERSION

This is the process of word formation (derivation process) whereby a base is assigned a new word category (class) without an addition or reduction of any affix. I.e. it is the process whereby a new word is formed by the change of one class into another without the addition or reduction of affix or syllable such as noun into verb adjective – noun and vice – verse

E.g. Love (N) Love is blind.

Love (V) I love you.

Walk (N) The walk to Kilimanjaro was fantastic.

Walk (V) We usually walk on foot to school.

Drink (N) We didn’t get any drink at chalinze.

Drink (V) My parents drink beer daily.

Help (N) I need help.

Help (V) I used to help him.

Work (N) My brother has gone to work.

Work (V) They work day and night.

Doubt (N) I did not have any doubt on her.

Doubt (V) I doubt his ability.

Lower (V) May you please lower your voice?

Lower (Adj) He usually speaks in a lower voice.

Ship (N) She traveled by ship.

Ship (V) Slave traders ship travel to America every year.

Poor (N) we need to help the poor.

Poor (Adj) That poor person has been killed.

NB: There some words which change from noun into verb by either voice in the final consonant or by stress shift

(N) Use /just/

(V) Use /just/

Advice (N) I gave him advice.

Advice (V) I advised him.

Object – (N) give me that object.

Object – (V) why do you object?

Conduct – (N) he didn’t show as any good.

Conduct – (V) conduct discussion.

Protest (N) — The protest was between government and student of Dodoma University.

Protest (V) – The groups of women took to the streets to protest against the arrest.

Present (N) Adj – I was present.

— He has brought a nice present.

Present (V) — Present your work.TASK

1. Construct two sentences in each of the following words showing how they can be used in a different word classes without any affixation process

i) Water

ii) Import

iii) Produce

iv) Class

v) Cleaning

2. Write new sentences by changing each of the words in capital in to noun

I. What you PRESENT to day will automatically affect your future

II. We except to PRODUCE enough crops this year because there is enough rain

III. The names of evils doers were BLACKLISTED

IV. For the language to develop, it must borrow some vocabularies from other language.

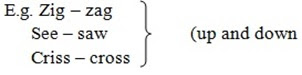

(d) REDUPLICATION

This is the process of word formation where by new words are formed through the repetition of the same or almost the same sounds i.e. It is the process whereby the new word are formed by repeating sound which are either similar or slightly different

E.g. Hush – hush

Sing – song

Tip – top

Tick – tock

Ding – dong

Zig – zag

Criss – cross

Poor – poor

Goody – goody

See – saw

Tom – tom

Bow – Bo

NB: The new words that are formed as a result of reduplication process are known as reduplicative

The reduplication have the following basic uses

1. To imitate sound

E.g. Ding – dong (sound of the bell)

Ha ha — (sound of laughter)

Bow – bow (dog barking)

Tick – tock (Clock sound)

2. To make things took more intense than they are.

(To intensify adjectives)

E.g. Tip – top – (top most)

Goody – goody (very good)

3. To suggest a state of disorder, instability, non-sense

E.g. Niggled – pigged (Un orderly/ mixed up)

Lodge – podge (disorganized)

Wishy – washy (weak)

Locus – pocus (Trickery)

Tick – tacky (cheap an of low quality)

Pool – pool (not working)

4. To suggest alternative movement of things

II. Minor processes of word information

(e) CLIPPING

This process of word formation whereby one of the syllables are omitted or subtracted from a word and the remaining syllables are regarded as a new word

This occurs when a word of more than one syllable is reduced to a shorter form which is regarded as a new word.

NB: The removal or emotion of a syllable may take place either at the beginning at the end of the word or both.

(f) BLENDING

This is the process of word formation whereby two or more parts, fragments or elements of two or more different words are put or joined together to form a new.

I.e. it is the process of talking only the beginning part of one word and joining it to (with) the beginning or the end of another word.

Example:

breakfast + lunch = Bruch

Motorist + hotel =motel

Cellular + telephone = cell phone

Mobile + telephone = mobile

Television + Broad cast = telecast

International + police = Interpol

Transfer + resister = transistor

Information + entertainment = infotainment

Gasoline + alcohol = gas

International + network = internet

Television + marathon = telethon

Motor + pedal = moped

Electronic + mail = email

Smoke + fog = smog

Helicopter + airport = heliport

Parachute + troops = paratroops

Travel + catalogue = travelogue

Binary + Digit = bit

(g) ACRONYM

This is the process of word formation whereby the initial or first letters of different words are put together as a new word.

The words that are formed from the initial letter are technique termed as acronyms.

There are two types of acronyms

i. Acronyms pronounced as a sequence of letter

E.g. C.O.D – cash on delivery

CID – Criminal Investigation Department

FBI – Federal bureau

UN – United Nations

IPA – International Phonetic Alphabet

CUF – Civil United Front

CPU- central processing unit

ii. Acronyms pronounced as words

E.g. NATO – North Atlantic Treaty Organization

TANESCO – Tanzania electricity Supply Company

UNO – United Nations Organization

UNESCO – United nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization

AIDS – Acquired immune Deficiency and Syndrome

CUF – Civil United Fronts

TANU – Tanganyika African National Union

TAMWA – Tanzania Media Women Association

(h) BACK FORMATION

This is the process of word formation whereby new words are created or formed by the removal of some parts (affixes) from an existing word.

I.e. it is the process whereby a word of one type (usually a noun) is reduced to form another word of different type (usually a verb)

E.g. Option = opt

Examination = Examine

Donation = Donate

Worker = Work

Television = Televised

Emotion = Emote

Discussion = Discuss

Action = act

(i) BORROWING

This is the process of taking over the words from one language and adopting or incorporating into another language. The borrowed words are termed as loan words.

English language has borrowed many words

E.g. alcohol — Arabic

Zebra — Bantu

Safari — Swahili

Garage – French

Piano – Italian

Chemistry – Arabic

Opera – Italian

Umbrella – Italian

Mosquito – Spanish

Zero – Arabic

Wagon – Dutch

Golf – Dutch

Calvary – Italian

Magazine Arabic

Bazaar – Persia

Boss – Dutch

Tycoon – Japanese

Algebra – Arabic

However other language have borrowed some words from English

(Shirt) English – shati — Swahili

Super market – suupaa – maketto – Japanese

Radio – rajio – Japanese

(j) COINING/ COINAGE

This is the process of word formation by which totally new words are incorporated into the language. This comes as a result of scientific discoveries in which new terms or words are introduced which name the product.

E.g. Aspirin

Website

Black berry

Toss

Hitachi

Samsung

Internet

Globalization

You – tube

(k) ONOMATOPOEIA

This is the process whereby words are formed by imitating the natural sounds made by objects or animal. The word formed by imitating the natural sounds made by objects or animals are termed as Onomatopoeic or Echo words

E.g. ding – dong (sound of a bell)

Bomb (explosion)

Bow bow (dog barking)

Bang (sudden loud noise of something)

Tick – tock – (clock sound)

Cuckoo – (sound of a bird)

Hah aha –( laughter)

Revision Question

1. Mention the word formation processes involved in the formation of the following words.

i. Exaggeration

ii. Vodacom

iii. Transistor

iv. Safari

v. Revlon

vi. Farmer

vii. Sugarcane

viii. Leader ship

ix. Book case

x. Motel

xi. Socialist

xii. Bookcase

xiii. Prof

xiv. Samsung

xv. Mini

xvi. Motorcycle

2. Make two different sentences for each of the following words. For each sentence the word has to belong to a different class.

i. A conflict

(i) ………………………………………………………………………………………………….

(ii) …………………………………………………………………………………………………..

ii. Abuse

(i) …………………………………………………………………………………………………..

(ii) …………………………………………………………………………………………….

iii. Insult

(i) ……………………………………………………………………………………………………

(ii) ……………………………………………………………………………………………………

iv. Narrow

(i) ……………………………………………………………………………………………………

(ii) ……………………………………………………………………………………………

v. Reject

(i) ……………………………………………………………………………………………………

(ii) …………………………………………………………………………………………..

3. Name the word formation processes involved in the formation of the words in brackets

I. Mwakifulefule had a (jacket less) book

II. Mayasa (parties) every Saturday night

III. Everybody must fight against (aids)

IV. Mufungwa has just got a new (car phone)

V. Kagaruki wants to be a (footballer)

NECTA 2012

1. Read the following complex sentence and then answer the questions that follow.

Tanzania government has been using teacher in trying to transform education system which was inherited from the colonialism in order to match it with its own new goals, aspirations and concepts of development.

Identify the following from the above given sentence.

a. Five stems

b. From 5 stems in part (a) show the roots

c. 5 derivation morphemes

d. 5 inflectional morpheme

2. a) Provide the adjectival forms the following words and write one Sentence for all

b) explain the process involved in the formation of the following groups of words

i. Alcohol, boos, piano, zebra

ii. Loan word, waste basket, water – bird, finger print

iii. Facsimile – fax, cabriolet – cab, advertisement – ad

iv. Telecast, hotel, heliport, brunch

vi. Telecast – television, opt- option, enthuse – enthusiasm, emote – emotion

Answers for question 1 & 2 (necta 2012)

1a. Government

Education

Colonialism

Aspiration

Development

b. Govern

Educate

Colony

Spice

Develop

c. meant

ion

ism

ion

met

d. -ing

-en

-s

-ed

2. a) Breakable

My pen is breakable.

b. Measurable

Ojiki’s thing is measurable

c. Mental

She visited the mental clinic

d. Memorable

Her birthday was a memorable event

e. Medical

She is a medical student

b) (i) Borrowing

(ii) Compounding

(iii) Clipping

(iv) Blending

(v) Back formation

Definitions of word form

-

noun

the phonological or orthographic sound or appearance of a word that can be used to describe or identify something

-

synonyms:

descriptor, form, signifier

see moresee less-

types:

- show 9 types…

- hide 9 types…

-

plural, plural form

the form of a word that is used to denote more than one

-

singular, singular form

the form of a word that is used to denote a singleton

-

ghost word

a word form that has entered the language through the perpetuation of an error

-

base, radical, root, root word, stem, theme

(linguistics) the form of a word after all affixes are removed

-

etymon, root

a simple form inferred as the common basis from which related words in several languages can be derived by linguistic processes

-

citation form, entry word, main entry word

the form of a word that heads a lexical entry and is alphabetized in a dictionary

-

abbreviation

a shortened form of a word or phrase

-

acronym

a word formed from the initial letters of the several words in the name

-

apocope

abbreviation of a word by omitting the final sound or sounds

-

type of:

-

word

a unit of language that native speakers can identify

DISCLAIMER: These example sentences appear in various news sources and books to reflect the usage of the word ‘word form’.

Views expressed in the examples do not represent the opinion of Vocabulary.com or its editors.

Send us feedback

EDITOR’S CHOICE

Look up word form for the last time

Close your vocabulary gaps with personalized learning that focuses on teaching the

words you need to know.

Sign up now (it’s free!)

Whether you’re a teacher or a learner, Vocabulary.com can put you or your class on the path to systematic vocabulary improvement.

Get started

- Top Definitions

- Synonyms

- Quiz

- Related Content

- Examples

- British

- Idioms And Phrases

This shows grade level based on the word’s complexity.

This shows grade level based on the word’s complexity.

noun

external appearance of a clearly defined area, as distinguished from color or material; configuration: a triangular form.

the shape of a thing or person.

a body, especially that of a human being.

a dummy having the same measurements as a human body, used for fitting or displaying clothing: a dressmaker’s form.

something that gives or determines shape; a mold.

a particular condition, character, or mode in which something appears: water in the form of ice.

the manner or style of arranging and coordinating parts for a pleasing or effective result, as in literary or musical composition: a unique form for the novel.

Fine Arts.

- the organization, placement, or relationship of basic elements, as lines and colors in a painting or volumes and voids in a sculpture, so as to produce a coherent image; the formal structure of a work of art.

- three-dimensional quality or volume, as of a represented object or anatomical part.

- an object, person, or part of the human body or the appearance of any of these, especially as seen in nature: His work is characterized by the radical distortion of the human form.

any assemblage of things of a similar kind constituting a component of a group, especially of a zoological group.

Crystallography. the combination of all the like faces possible on a crystal of given symmetry.

due or proper shape; orderly arrangement of parts; good order.

Philosophy.

- the structure, pattern, organization, or essential nature of anything.

- structure or pattern as distinguished from matter.

- (initial capital letter)Platonism. idea (def. 7c).

- Aristotelianism. that which places a thing in its particular species or kind.

Logic. the abstract relations of terms in a proposition, and of propositions to one another.

a set, prescribed, or customary order or method of doing something.

a set order of words, as for use in religious ritual or in a legal document: a form for initiating new members.

a document with blank spaces to be filled in with particulars before it is executed: a tax form.

a typical document to be used as a guide in framing others for like cases: a form for a deed.

a conventional method of procedure or behavior: society’s forms.

a formality or ceremony, often with implication of absence of real meaning: to go through the outward forms of a religious wedding.

procedure according to a set order or method.

conformity to the usages of society; formality; ceremony: the elaborate forms prevalent in the courts of renaissance kings.

procedure or conduct, as judged by social standards: Such behavior is very bad form.Good form demands that we go.

manner or method of performing something; technique: The violin soloist displayed tremendous form.

physical condition or fitness, as for performing: a tennis player in peak form.

Grammar.

- a word, part of a word, or group of words forming a construction that recurs in various contexts in a language with relatively constant meaning.Compare linguistic form.

- a particular shape of such a form that occurs in more than one shape. In I’m, ‘m is a form of am.

- a word with a particular inflectional ending or other modification. Goes is a form of go.

Linguistics. the shape or pattern of a word or other construction (distinguished from substance).

Building Trades. temporary boarding or sheeting of plywood or metal for giving a desired shape to poured concrete, rammed earth, etc.

a grade or class of pupils in a British secondary school or in certain U.S. private schools: boys in the fourth form.

British. a bench or long seat.

British Informal. a criminal record: She didn’t want to believe that her own mother had form.

Also British, forme. Printing. an assemblage of types, leads, etc., secured in a chase to print from.

verb (used with object)

to construct or frame.

to make or produce.

to serve to make up; serve as; compose; constitute: The remaining members will form the program committee.

to frame (ideas, opinions, etc.) in the mind.

to contract or develop (habits, friendships, etc.).

to give a particular form or shape to; fashion in a particular manner: Form the dough into squares.

to mold or develop by discipline or instructions: The sergeant’s job was to form boys into men.

Grammar.

- to make (a derivation) by some grammatical change: The suffix “-ly” forms adverbs from adjectives.

- to have (a grammatical feature) represented in a particular shape: English forms plurals in “-s”.

Military. to draw up in lines or in formation.

verb (used without object)

to take or assume form.

to be formed or produced: Ice began to form on the window.

to take a particular form or arrangement: The ice formed in patches across the window.

QUIZ

CAN YOU ANSWER THESE COMMON GRAMMAR DEBATES?

There are grammar debates that never die; and the ones highlighted in the questions in this quiz are sure to rile everyone up once again. Do you know how to answer the questions that cause some of the greatest grammar debates?

Which sentence is correct?

Origin of form

First recorded in 1175–1225; Middle English forme, from Old French, from Latin forma “form, figure, model, mold, sort,” Medieval Latin: “seat”

synonym study for form

1. Form, figure, outline, shape refer to an appearance that can be recognized. Form, figure, and shape are often used to mean an area defined by contour without regard to other identifying qualities, as color or material. Outline refers to the line that delimits a form, figure, or shape: the outline of a hill. Form often includes a sense of mass or volume: a solid form. Shape may refer to an outline or a form: an “S” shape; a woman’s shape. Figure often refers to a form or shape determined by its outline: the figure eight. Form and shape may also be applied to abstractions: the shape or form of the future. Form is applied to physical objects, mental images, methods of procedure, etc.; it is a more inclusive term than either shape or figure : the form of a cross, of a ceremony, of a poem.

OTHER WORDS FROM form

form·a·ble, adjectiveform·a·bly, adverbhalf-formed, adjectivemis·form, verb

mis·formed, adjectivenon·form, nounnon·form·ing, adjectiveo·ver·formed, adjectiveself-formed, adjectivesem·i·formed, adjectivesub·form, nounun·der·form, noun

WORDS THAT MAY BE CONFUSED WITH form

form , forum

Words nearby form

forky, Forlì, forlorn, forlorn hope, for love or money, form, formability, formal, formal cause, formaldehyde, formal equivalence

Other definitions for form (2 of 2)

a combining form meaning “having the form of”: cruciform.

Origin of -form

From the Latin suffix -fōrmis

Dictionary.com Unabridged

Based on the Random House Unabridged Dictionary, © Random House, Inc. 2023

Words related to form

design, fashion, mode, model, pattern, plan, scheme, structure, style, system, condition, object, shape, thing, behavior, law, manner, method, practice, process

How to use form in a sentence

-

This form of discrimination is against Google’s own personalized advertising policy.

-

If you truly believe in love in all its forms, strive to be as sweet and kind as possible, and like nice things, you’re a Charlotte.

-

In a tweet yesterday, Google announced lead form extensions for Search, Video, and Discovery ads.

-

Previously in beta, Google Ads announced its updated lead form extension which pops up a form directly from a click on an ad in search, Video, and Discovery.

-

The league already has called off the NFL scouting combine, at least in its traditional form in Indianapolis.

-

The same Pediatrics journal notes that 17 states have some form of exception to the standard parental consent requirement.

-

I mean, physically, mentally, you know, in every way, shape, and form.

-

And with regular clients that see him at least twice a month, relationships inevitably form.

-

I ask Atefeh and Monir if they see dancing as a form of income in the future, a potential career.

-

But probably because we co-edited the Deadline Artists anthologies with our friend Jesse Angelo, we feel a fidelity to the form.

-

Practise gliding in the form of inflection, or slide, from one extreme of pitch to another.

-

The supernaturalist alleges that religion was revealed to man by God, and that the form of this revelation is a sacred book.

-

Arches more graceful in form, or better fitted to defy the assaults of time, I have never seen.

-

As company after company appeared, we were able to form a pretty exact estimate of their numbers.

-

And remember it is by our hypothesis the best possible form and arrangement of that lesson.

British Dictionary definitions for form (1 of 3)

noun

the shape or configuration of something as distinct from its colour, texture, etc

the particular mode, appearance, etc, in which a thing or person manifests itselfwater in the form of ice; in the form of a bat

a type or kindimprisonment is a form of punishment

- a printed document, esp one with spaces in which to insert facts or answersan application form

- (as modifier)a form letter

physical or mental condition, esp good condition, with reference to ability to performoff form

the previous record of a horse, athlete, etc, esp with regard to fitness

British slang a criminal record

style, arrangement, or design in the arts, as opposed to content

a fixed mode of artistic expression or representation in literary, musical, or other artistic workssonata form; sonnet form

a mould, frame, etc, that gives shape to something

organized structure or order, as in an artistic work

education, mainly British a group of children who are taught together; class

manner, method, or style of doing something, esp with regard to recognized standards

behaviour or procedure, esp as governed by custom or etiquettegood form

formality or ceremony

a prescribed set or order of words, terms, etc, as in a religious ceremony or legal document

philosophy

- the structure of anything as opposed to its constitution or content

- essence as opposed to matter

- (often capital) (in the philosophy of Plato) the ideal universal that exists independently of the particulars which fall under itSee also Form

- (in the philosophy of Aristotle) the constitution of matter to form a substance; by virtue of this its nature can be understood

British a bench, esp one that is long, low, and backless

the nest or hollow in which a hare lives

a group of organisms within a species that differ from similar groups by trivial differences, as of colour

linguistics

- the phonological or orthographic shape or appearance of a linguistic element, such as a word

- a linguistic element considered from the point of view of its shape or sound rather than, for example, its meaning

taxonomy a group distinguished from other groups by a single characteristic: ranked below a variety

verb

to give shape or form to or to take shape or form, esp a specified or particular shape

to come or bring into existencea scum formed on the surface

to make, produce, or construct or be made, produced, or constructed

to construct or develop in the mindto form an opinion

(tr) to train, develop, or mould by instruction, discipline, or example

(tr) to acquire, contract, or developto form a habit

(tr) to be an element of, serve as, or constitutethis plank will form a bridge

(tr) to draw up; organizeto form a club

Derived forms of form

formable, adjective

Word Origin for form

C13: from Old French forme, from Latin forma shape, model

British Dictionary definitions for form (2 of 3)

noun