Just here for the exercises? Click here.

Introduction

Declarative sentences make a statement or state a fact. They can be positive or negative. In English grammar, the usual word order in declarative sentences is subject – predicate – object.

Learn about the order of nouns, verbs and other sentence components in declarative sentences with Lingolia’a simple grammar rules. In the exercises, you can practise word order in English sentences.

Example

|

The dog is catching the ball. |

|

|

|

There are some languages where word order doesn’t matter: the subject (the dog) or the object (the ball) can come first in the sentence. |

|

In English, however, we can’t change the word order, because then it would mean that the ball is the one doing the catching. |

|

| The ball is catching the dog. |

Word Order in Declarative Sentences

Positive and negative sentences

The usual word order for declarative sentences is subject – predicate – object – place – time.

* See negation for more information about negating in different English tenses.

Verbs with two objects

When a sentence has more than one object, the indirect object usually goes before the direct object.

- Example:

- My dog has brought me the ball.

Jack gave his dog a present.

However, when the indirect object with has a preposition, it goes after the direkt object.

- Example:

- My dog has brought the ball to me.

Jack gave a present to his dog.

Dependent clauses

A dependent clause forms a complex sentence together with a main clause. The word order in dependent clauses is the same, except that the clause begins with a conjunction.

- Example:

- Many people walk their dogs in the park on Sundays because they don’t have the time during the week.

In theory, every English sentence should begin with a subject – but then lengthy texts would sound very boring. In order to make texts more varied and interesting, the time or dependent clause at the beginning of the sentence instead.

- Example:

- On Sundays, many people walk their dogs in the park.

- Because they do not have to go to work at the weekend, many people walk their dogs in the park on Sundays.

Statements, or declarative sentences, can be in the form of simple, compound, or complex sentences.

This article describes standard word order in simple declarative sentences. Word order in compound sentences and complex sentences is described in Basic Word Order and Word Order in Complex Sentences in the section Grammar. Examples comparing standard word order and inverted word order can be found in Inversion in the section Miscellany.

Statements in the form of simple sentences are divided into unextended sentences and extended sentences. There are five parts of a sentence: the subject, the predicate, the object, the attribute, the adverbial modifier. The rules of word order indicate where their place in the sentence is.

Word order in simple unextended sentences

Standard word order in simple unextended declarative sentences is SUBJECT + PREDICATE.

Anna teaches.

Time flies.

We are reading.

He will understand.

Word order in simple extended sentences

Standard word order in simple extended declarative sentences is SUBJECT + PREDICATE + object + adverbial modifier.

Anna teaches mathematics.

Tom has returned my books.

We are reading a story now.

He will understand it later.

Adverbial modifiers are normally placed at the end of the sentence after the object (or after the verb, if there is no object). Attributes (adjectives, numerals, pronouns) usually stand before their nouns, and attributes in the form of nouns with prepositions are placed after their nouns.

Anna has classes on the second floor.

Tom has worked here for ten years.

He wrote two interesting articles about football.

The place of the subject

The subject is placed at the beginning of the sentence and is usually expressed by a noun or a pronoun. The subject group may include an article and an attribute.

Monkeys like bananas.

He writes short stories.

That student is from Rome.

Tom and Anna live in Boston.

His little son is learning to read.

The subject is placed after the verb in the structure «there is, there are» which is used when you want to say WHAT is in some place.

There is a table in the room.

There are two books on the table.

There was a car in front of the house.

The place of the predicate

The predicate stands after the subject and is usually represented by a main verb or by the combination of an auxiliary or modal verb with a main verb. Negative forms of auxiliary verbs can be full or contracted.

She likes chocolate.

I work at a small hotel.

The children are reading and writing new words.

She does not know him.

He hasn’t bought a car yet.

You shouldn’t do it.

We are not going to buy a new house this summer.

The verb «be» as a linking verb may be followed by a noun, an adjective, a numeral, or a pronoun as part of the predicate. (The use of the verb «be» is described in The Verb BE in the section Grammar.)

I am a teacher.

Tom is young.

The tea is too hot.

She was twenty.

He isn’t a doctor.

This isn’t she.

The place of the object

There are direct objects (without a preposition) and indirect objects (with or without a preposition). The object is placed after the main verb. If there are two objects after the verb, the word order is first the direct object, then the object with preposition.

Tom collects stamps.

He likes reading.

He likes to read.

He is waiting for a bus.

She gave two books to her brother.

Liz asked the boy about his father.

She made soup, salad, and roast beef for dinner.

Some transitive verbs (for example, bring, give, offer, sell, send, show, tell) are often followed by two objects without prepositions. In this case, the order after the verb is first the indirect object (without a preposition), then the direct object. Examples:

She gave him two books.

They offered me a good job.

He sent her a present.

The teacher told the students a story.

The place of the attribute

Attributes expressed by adjectives (or by pronouns, participles, numerals, nouns in the possessive case) usually stand before their nouns, i.e., before the noun in the subject, in the object, or in the adverbial modifier. Examples:

A good writer should know many things.

My old dog liked fresh apples.

We threw out several broken chairs.

Four students passed that difficult test.

The doctor’s new house is near a large park.

If there are several adjectives before a noun, a more specific adjective is placed closer to its noun than a more general adjective.

She bought a green sweater.

She bought a nice green woolen sweater.

Chicago is a big city.

Chicago is a beautiful big clean city.

My daughter likes soft blue, gray, and green colors.

My daughter likes soft gray, green, and blue colors.

Attributes in the form of a noun with a preposition or structures with participles are placed after the noun that they modify.

She bought a silk blouse with long sleeves.

Chicago is a big city in the Midwest.

I took the bus going through Springfield.

The waiter threw out the chairs broken in yesterday’s fight.

The place of the adverbial modifier

Adverbial modifiers of place, time, frequency, manner are often expressed by adverbs or by nouns with prepositions and are placed at the end of the sentence after the main verb or after the object if there is an object.

Adverbial modifiers of place

They live on Main Street.

The bedrooms are upstairs.

I went across the bridge.

She has to go to the bank.

They spent their vacation at the lake.

Adverbial modifiers of time

I’m going to see him tomorrow.

I spoke to him an hour ago.

He saw her before leaving.

I went to work after class.

She was sick yesterday.

The meeting was at ten o’clock last Friday.

Adverbial modifiers of frequency

She visits them sometimes.

They go to concerts often.

He calls her every day.

He writes to her regularly.

She goes shopping once or twice a week.

Adverbial modifiers of manner

He drives very fast.

He closed the door slowly.

He ate the food hungrily.

We came here by train.

He opened the door with a key.

Peculiarities of the position of adverbial modifiers

Adverbial modifiers consisting of two or more words are placed at the end of the sentence after the main verb (or after the object, if any). Possible positions of adverbial modifiers of time and frequency consisting of one word are described below.

One-word adverbs of frequency

One-word adverbs of frequency «often, frequently, rarely, regularly, sometimes» are often placed between the subject and the main verb in the simple tenses but may also be placed after the main verb (or after the object, if any).

He often goes to the park.

He goes to the park often.

We rarely buy food in that store.

He frequently visited them last year.

He visited them frequently last year.

Adverbs of frequency «usually, always, never, seldom» are placed between the subject and the main verb in the simple tenses but are usually placed after the verb «be».

They seldom talk about it.

She usually buys bread, cheese, and milk in this grocery store.

He always asks me this question.

He is always late.

He is never home before seven.

One-word adverbs of time

One-word adverbs of time «already, just, never, ever» are placed between the two parts of the predicate in the perfect tenses, though «already» can also stand after the main verb.

She has already left.

She has left already.

She has just called me.

I have never been to Mexico.

Have you ever seen this film?

They had already left for London by the time he arrived in Paris.

If there are two auxiliary verbs in a tense form, the adverb is usually placed after the first auxiliary verb. «Already» may also stand after the second auxiliary verb, for example, in the Future Perfect.

He has never been asked such questions.

He may already have called them.

His plane will already have landed by the time we get to the airport.

He will have already left for London by Friday.

Some one-word adverbs of time or frequency, for example, «today, tomorrow, yesterday, sometimes, usually», are sometimes placed at the beginning of the sentence before the subject (usually for emphasis).

Yesterday I talked to Jim.

Tomorrow we are leaving.

Suddenly the rain started.

Sometimes she stays at this hotel for a few days.

Usually, she has a cheese sandwich in the morning, but today she is eating scrambled eggs for breakfast.

Two-word adverbial modifiers

Two-word adverbs and adverbial modifiers with prepositions are placed at the end of the sentence after the verb (or after the object, if any). If there are several adverbial modifiers, the adverbial modifier of place is usually placed before the adverbial modifier of time.

They stayed in his house for about an hour.

Professor Benson usually has two classes at the university every day.

My new neighbors often read a good book in their garden after breakfast.

He arrived in Vienna by train at 7:00 a.m. on Thursday.

Порядок слов в повествовательных предложениях

Повествовательные предложения могут быть в виде простых, сложносочиненных или сложноподчиненных предложений.

Эта статья описывает стандартный порядок слов в простых повествовательных предложениях. Порядок слов в сложносочиненных и сложноподчиненных предложениях описан в статьях «Basic Word Order» и «Word Order in Complex Sentences» в разделе Grammar. Примеры, сравнивающие стандартный и обратный порядок слов, можно найти в статье «Inversion» в разделе Miscellany.

Простые повествовательные предложения делятся на нераспространенные предложения и распространенные предложения. Есть пять членов предложения: подлежащее, сказуемое, дополнение, определение, обстоятельство. Правила порядка слов указывают, где их место в предложении.

Порядок слов в простых нераспространенных предложениях

Стандартный порядок слов в простых нераспространенных повествовательных предложениях: подлежащее + сказуемое.

Анна преподает.

Время летит.

Мы читаем.

Он поймет.

Порядок слов в простых распространенных предложениях

Стандартный порядок слов в простых распространенных повествовательных предложениях: подлежащее + сказуемое + дополнение + обстоятельство.

Анна преподает математику.

Том вернул мои книги.

Мы читаем рассказ сейчас.

Он поймет это позже.

Обстоятельства обычно ставятся в конце предложения после дополнения (или после глагола, если дополнения нет). Определения (прилагательные, числительные, местоимения) обычно стоят перед своими существительными, а определения в форме существительных с предлогами ставятся после своих существительных.

У Анны занятия на втором этаже.

Том проработал здесь десять лет.

Он написал две интересные статьи о футболе.

Место подлежащего

Подлежащее ставится в начале предложения и обычно выражено существительным или местоимением. Группа подлежащего может включать артикль и определение.

Обезьяны любят бананы.

Он пишет короткие рассказы.

Тот студент – из Рима.

Том и Анна живут в Бостоне.

Его маленький сын учится читать.

Подлежащее ставится после глагола в конструкции «there is, there are», которая употребляется, когда вы хотите сказать, ЧТО именно находится в каком-то месте.

В комнате (находится) стол.

На столе (есть) две книги.

Перед домом был автомобиль.

Место сказуемого

Сказуемое стоит за подлежащим и обычно представлено основным глаголом или комбинацией вспомогательного или модального глагола с основным глаголом. Отрицательные формы вспомогательных глаголов могут быть полными или сокращенными.

Она любит шоколад.

Я работаю в маленькой гостинице.

Дети читают и пишут новые слова.

Она не знает его.

Он еще не купил машину.

Вам не следует этого делать.

Мы не собираемся покупать новый дом этим летом.

За глаголом «be» как за глаголом-связкой может следовать существительное, прилагательное, числительное или местоимение как часть сказуемого. (Употребление глагола «be» описано в статье «The Verb BE» в разделе Grammar.)

Я (есть) учитель.

Том молодой.

Чай слишком горячий.

Ей было двадцать.

Он не врач.

Это не она.

Место дополнения

Есть прямые дополнения (без предлога) и косвенные дополнения (с предлогом или без предлога). Дополнение ставится после основного глагола. Если есть два дополнения после глагола, порядок слов такой: сначала идет прямое дополнение, затем дополнение с предлогом.

Том собирает марки.

Он любит чтение.

Он любит читать.

Он ждет автобус.

Она дала две книги своему брату.

Лиз спросила мальчика о его отце.

Она приготовила суп, салат и ростбиф на обед.

За некоторыми переходными глаголами (например, принести, дать, предложить, продать, послать, показать, рассказать) часто следуют два дополнения без предлогов. В этом случае после глагола сначала идет косвенное дополнение (без предлога), а затем прямое дополнение. Примеры:

Она дала ему две книги.

Они предложили мне хорошую работу.

Он послал ей подарок.

Учитель рассказал студентам историю.

Место определения

Определения, выраженные прилагательными (или местоимениями, причастиями, числительными, существительными в притяжательном падеже), обычно стоят перед своими существительными, т.е. перед существительным в подлежащем, дополнении или обстоятельстве. Примеры:

Хороший писатель должен знать много вещей.

Моя старая собака любила свежие яблоки.

Мы выбросили несколько сломанных стульев.

Четыре студента сдали тот трудный тест.

Новый дом доктора находится возле большого парка.

Если есть несколько прилагательных перед существительным, более конкретизирующее прилагательное ставится ближе к своему существительному, чем более общее.

Она купила зеленый свитер.

Она купила хороший зеленый шерстяной свитер.

Чикаго большой город.

Чикаго красивый большой чистый город.

Моя дочь любит мягкие голубые, серые и зеленые цвета.

Моя дочь любит мягкие серые, зеленые и голубые цвета.

Определения в виде существительного с предлогом или конструкции с причастиями ставятся после существительного, которое они определяют.

Она купила шелковую блузку с длинными рукавами.

Чикаго большой город на Среднем Западе.

Я сел на автобус, идущий через Спрингфилд.

Официант выбросил стулья, сломанные во вчерашней драке.

Место обстоятельства

Обстоятельства места, времени, частоты действия, образа действия часто выражены наречиями или существительными с предлогами и ставятся в конце предложения после основного глагола или после дополнения, если есть дополнение.

Обстоятельства места

Они живут на Главной улице.

Спальни наверху.

Я перешел через мост.

Она должна пойти в банк.

Они провели свой отпуск у озера.

Обстоятельства времени

Я собираюсь увидеться с ним завтра.

Я говорил с ним час назад.

Он виделся с ней перед уходом.

Я пошел на работу после занятия.

Она была больна вчера.

Собрание было в десять часов в прошлую пятницу.

Обстоятельства частоты действия

Она их навещает иногда.

Они ходят на концерты часто.

Он звонит ей каждый день.

Он пишет ей регулярно.

Она ходит за покупками раз или два в неделю.

Обстоятельства образа действия

Он водит (машину) очень быстро.

Он закрыл дверь медленно.

Он с жадностью съел еду.

Мы приехали сюда поездом.

Он открыл дверь ключом.

Особенности расположения обстоятельств

Обстоятельства, состоящие из двух и более слов, ставятся в конце предложения после основного глагола (или после дополнения, если оно есть). Возможные варианты расположения обстоятельств времени и частоты действия, состоящих из одного слова, описаны ниже.

Наречия частоты действия из одного слова

Состоящие из одного слова наречия частоты действия «often, frequently, rarely, regularly, sometimes» часто ставятся между подлежащим и основным глаголом в простых временах, но могут также размещаться после основного глагола (или после дополнения, если оно есть).

Он часто ходит в парк.

Он ходит в парк часто.

Мы редко покупаем еду в том магазине.

Он часто навещал их в прошлом году.

Он навещал их часто в прошлом году.

Наречия частоты действия «usually, always, never, seldom» ставятся между подлежащим и основным глаголом в простых временах, но обычно ставятся после глагола «be».

Они редко говорят об этом.

Она обычно покупает хлеб, сыр и молоко в этом продуктовом магазине.

Он всегда задает мне этот вопрос.

Он всегда опаздывает.

Его никогда нет дома раньше семи.

Наречия времени из одного слова

Состоящие из одного слова наречия времени «already, just, never, ever» ставятся между двумя частями сказуемого в перфектных временах, хотя «already» может также стоять после основного глагола.

Она уже уехала.

Она уехала уже.

Она только что мне звонила.

Я никогда не бывал в Мексике.

Вы когда-либо видели этот фильм?

Они уже уехали в Лондон к тому времени, как он прибыл в Париж.

Если во временной форме два вспомогательных глагола, наречие обычно ставится после первого. «Already» может также стоять после второго вспомогательного глагола, например, во времени Future Perfect.

Ему никогда не задавали таких вопросов.

Он, возможно, уже позвонил им.

Его самолет уже приземлится к тому времени, как мы доберемся до аэропорта.

Он уже уедет в Лондон к пятнице.

Некоторые состоящие из одного слова наречия времени и частоты действия, например, «today, tomorrow, yesterday, sometimes, usually», иногда ставятся в начале предложения перед подлежащим (обычно для эмфатического выделения).

Вчера я поговорил с Джимом.

Завтра мы уезжаем.

Неожиданно начался дождь.

Иногда она останавливается в этой гостинице на несколько дней.

Обычно она ест бутерброд с сыром утром, но сегодня она ест яичницу на завтрак.

Обстоятельства из двух слов

Наречия из двух слов и обстоятельства с предлогами ставятся в конце предложения после глагола (или после дополнения, если оно есть). Если есть несколько обстоятельств, то обстоятельство места обычно ставится впереди обстоятельства времени.

Они оставались в его доме примерно час.

Профессор Бенсон обычно имеет два занятия в университете каждый день.

Мои новые соседи часто читают хорошую книгу в своем саду после завтрака.

Он приехал в Вену поездом в семь часов утра в четверг.

Word Order in Declarative Sentences

Declarative Sentences — повествовательные предложения — делятся на утвердительные (Affirmative) и отрицательные (Negative);

они имеют одинаковый порядок слов.

| Обстоятельство | Подлежащее | Сказуемое | Дополнение | Обстоятельство |

| Утвердительные предложения | ||||

| Boris Petrov | is a first-year student. | |||

| Yesterday | I | translated | the new text | quite well. |

| Tomorrow | Prof. Sokolov | will deliver | his lecture | at the club. |

| То learn well | one | must work | hard. | |

| The students of my group | had | practical work | last week. | |

| When I meet my friend | he | tells | me about his studies. | |

| This English article | was translated | by the students | at the last lesson. |

| Обстоятельство | Подлежащее | Сказуемое | Дополнение | Обстоятельство |

| Отрицательные предложения | ||||

| Boris Petrov | is not a first-year student. | |||

| Yesterday | I | did not translate | the new text | quite well. |

| Tomorrow | Prof. Sokolov | will not deliver | his lecture | at the club. |

| This English article | was not translated | by the students | at the last lesson. | |

| When I met my friend | he | did not tell | me anything about his studies. | |

| This text | cannot be translated | without a dictionary | as it is difficult. | |

| As the text is difficult | no one | can translate | it without a dictionary. |

Примечания:

- Определения (выделены в таблице) могут входить в состав любого члена предложения. Определения, выраженные отдельными словами, предшествуют определяемому существительному; определения, выраженные группой слов, следуют за определяемым существительным.

- В английском отрицательном предложении (в отличие от русского) бывает только одно отрицание, которое может входить в состав любого члена предложения.

No one can translate this article.

Никто не может перевести эту статью.

My friend did not tell me anything about it.

Мой друг ничего не сказал мне об этом.

We shall go nowhere tonight.

Мы никуда не пойдем сегодня вечером.

They have never been to the Urals.

Они никогда не были на Урале.

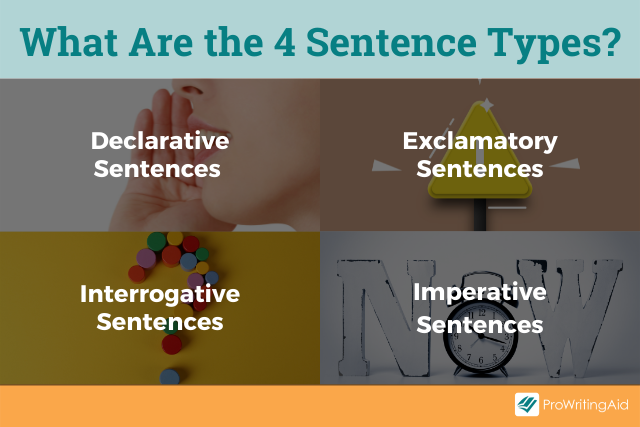

There are four types of sentences in the English language, and all of them accomplish different things.

If you want to be a successful writer, you’ll need to understand how to use each one. The most common of the four is called a declarative sentence.

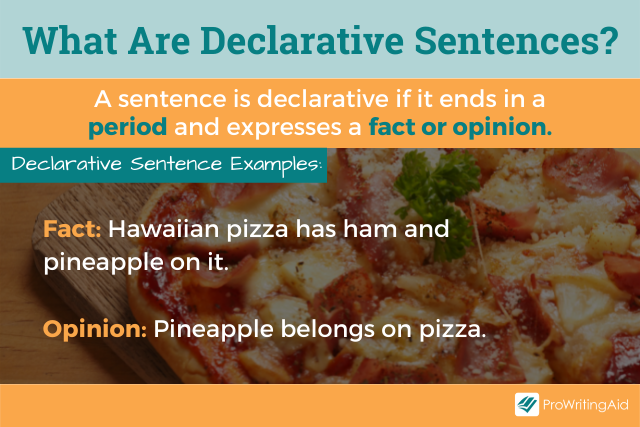

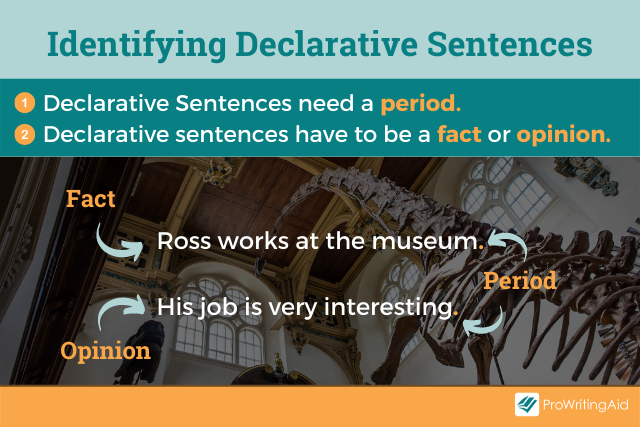

So what is a declarative sentence? The short answer is that a declarative sentence is a sentence that makes a statement and ends with a period.

This article will explain what a declarative sentence is and provide you with examples from literature.

What Is a Declarative Sentence?

A sentence is declarative if it ends in a period and expresses a fact or opinion.

Declarative sentences are aptly named because their purpose is to declare something. Every declarative sentence passes on some kind of information.

Here are some examples of declarative sentences:

- I’m going to be a published author someday.

- Two of her friends came late to her birthday party.

-

The Earth revolves around the sun.

What Are the Differences Between Declarative Sentences, Interrogative Sentences, Exclamatory Sentences, and Imperative Sentences?

Declarative sentences are one of four types of sentences.

The other three types of sentences are interrogative, exclamatory, and imperative sentences.

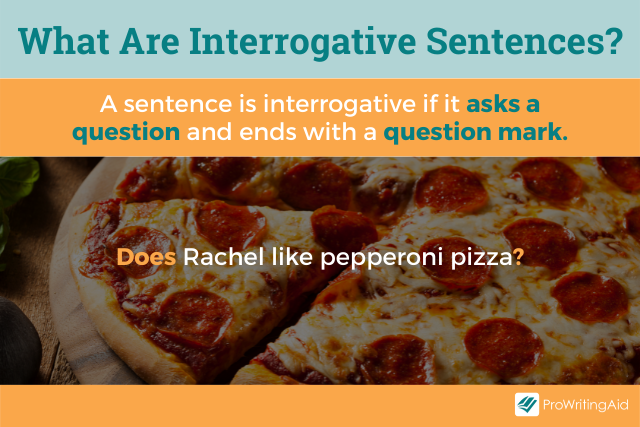

Interrogative Sentences

Interrogative sentences ask a question and end with a question mark.

Examples of interrogative sentences:

- Who are you?

- What’s going on here?

- Is that a llama or an alpaca over there?

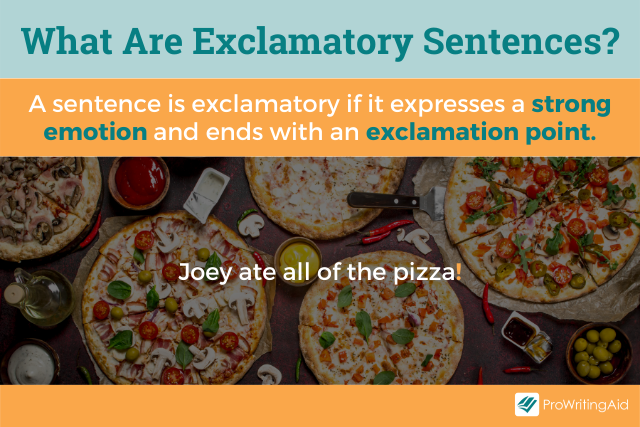

Exclamatory Sentences

Exclamatory sentences express a strong emotion—surprise, joy, anger, for example—and end with exclamation points.

Examples of exclamatory sentences:

- Hurray!

- Darn it!

- Aw, what a cute alpaca!

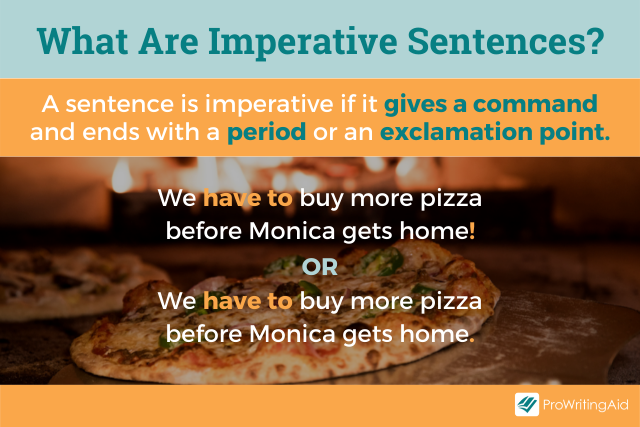

Imperative Sentences

Imperative sentences give a command, and end with either a period or an exclamation point.

Examples of imperative sentences:

- Go away!

- Dance like nobody’s watching.

-

Please let me pet that alpaca.

If a sentence asks a question, expresses a powerful emotion, or gives a command, you know it’s not a declarative sentence.

What Are Examples of Declarative Sentences in Literature?

Let’s take a look at some declarative sentence examples from successful books.

Notice how every sentence below ends in a period and states some kind of fact or opinion. They’re on all types of subjects, but they all declare something.

“I know it started being over with Joel when I’d open a bottle of wine and he wouldn’t drink it. Sharing things is how things get started, and not sharing things is how they end.”—Goodbye, Vitamin by Rachel Khong

“Having faith in God did not mean sitting back and doing nothing. It meant believing that you would find success if you did your best honestly and energetically.”—The Pillars of the Earth by Ken Follett

“Truth matters. Truth has always been the thing I’m after, the most important thing. But sometimes, to get to the truth, detours through fiction are necessary.”—Magic for Liars by Sarah Gailey

“The house was very still. Far off there was a sound which might have been beating surf or cars zooming along a highway, or wind in pine trees. It was the sea, of course, breaking far down below. I sat there and listened to it and thought long, careful thoughts.”—Farewell, My Lovely by Raymond Chandler

“The woman’s name is Essun. She is forty-two years old. She’s like most women of the midlats: tall when she stands, straight-backed and long-necked, with hips that easily bore two children and breasts that easily fed them, and broad, limber hands.”—The Fifth Season by N.K. Jemisin

“With me as the glaring exception, my father molded the world around him to his liking. The problem, of course, was that Baba saw the world in black and white. And he got to decide what was black and what was white. You can’t love a person who lives that way without fearing him too.”—The Kite Runner by Khaled Hosseini

“Time was simple, is simple. We can divide it into simple parts, measure it, arrange dinner by it, drink whisky to its passage. We can mathematically deploy it, use it to express ideas about the observable universe, and yet if asked to explain it in simple language to a child—in simple language which is not deceit, of course—we are powerless. The most it ever seems we know how to do with time is to waste it.”—The First Fifteen Lives of Harry August by Catherine Webb

“Perhaps, as we say in America, I wanted to find myself. This is an interesting phrase, not current as far as I know in the language of any other people, which certainly does not mean what it says but betrays a nagging suspicion that something has been misplaced. I think now that if I had had any intimation that the self I was going to find would turn out to be only the same self from which I had spent so much time in flight, I would have stayed at home.”—Giovanni’s Room by James Baldwin

“There is an unprecedented gathering of illusionists in the lobby of the theater. A gaggle of pristine suits and strategically placed silk handkerchiefs. Some have trunks and capes, others carry birdcages or silver-topped canes. They do not speak to each other as they wait to be called in, one at a time, referenced not by name (given or stage) but by a number written on a small slip of paper given to them upon arrival.”—The Night Circus by Erin Morgenstern

How Do You Construct a Simple Declarative Sentence?

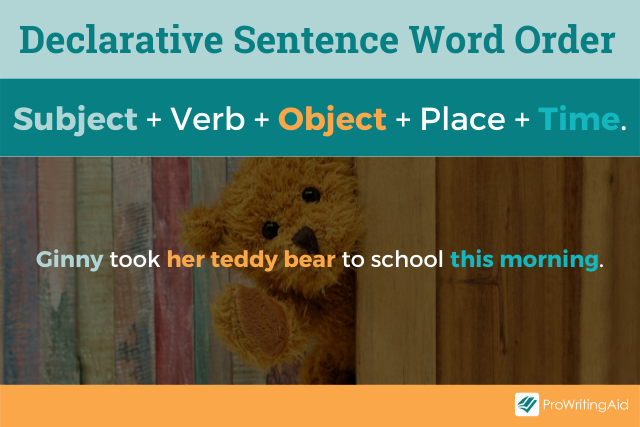

Most simple declarative sentences follow this word order: subject-verb-object-place-time.

The subject and the verb are the two crucial components. The rest are optional.

Here are some declarative sentences with just a subject and verb:

- I cooked.

- She drove.

- He wants to paint.

You can add an object.

- I cooked dumplings.

- She drove her sister’s car.

- He wants to paint his girlfriend’s portrait.

After that, you can add a place.

- I cooked dumplings at my friend’s house.

- She drove her sister’s car to work.

- He wants to paint his girlfriend’s portrait in his studio.

And finally, you can add a time as well.

- I cooked dumplings at my friend’s house yesterday.

- She drove her sister’s car to work this morning.

- He painted his girlfriend’s portrait in his studio tomorrow.

How Do You Use a Declarative Sentence to Ask a Question?

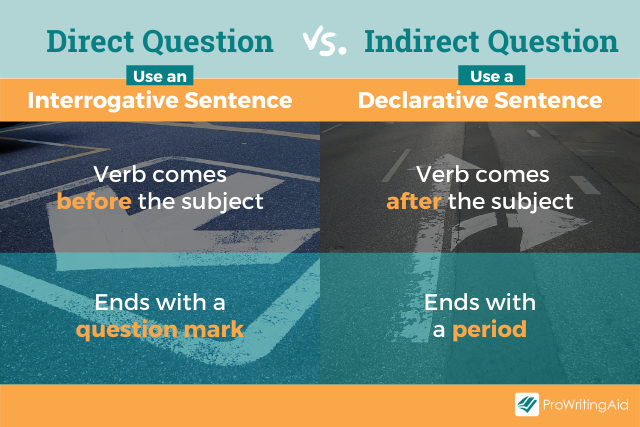

Not all sentences that ask questions have to be interrogative sentences.

Sometimes, you can use a declarative sentence to ask a question indirectly.

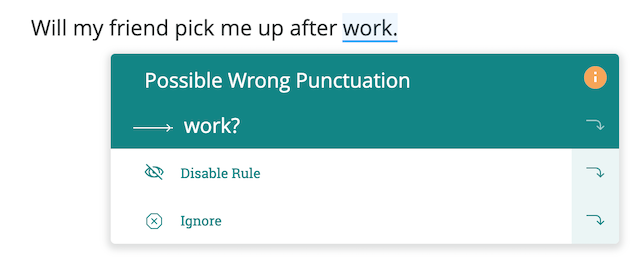

Take this sentence, for example: “I wonder if my friend will pick me up after work.”

In this case, the sentence includes a question, but it’s an indirect question, because it’s framed within a declarative sentence.

That’s why it still needs to end with a period, not a question mark.

The interrogative version of the question above would be: “Will my friend pick me up after work?” Because this is an interrogative sentence, the “will” comes before “my friend.”

ProWritingAid’s Realtime Grammar checker can help you determine the difference between declarative sentences and interrogative sentences by suggesting punctuation changes if necessary.

As you can see in the example, this is an interrogative sentence and therefore requires a question mark to make sense.

You can look at the word order to figure out whether the sentence is a declarative or interrogative one. The subject and verb usually get inverted for interrogative sentences.

- Declarative sentence (indirect question): My mother asked me what time I’d be home from the party.

- Interrogative sentence (direct question): What time will I be home from the party?

Final Words

Now you know how to identify and construct declarative sentences.

Was this article helpful? Let us know in the comments.

Are you prepared to write your novel? Download this free book now:

The Novel-Writing Training Plan

So you are ready to write your novel. Excellent. But are you prepared? The last thing you want when you sit down to write your first draft is to lose momentum.

This guide helps you work out your narrative arc, plan out your key plot points, flesh out your characters, and begin to build your world.

English

word order is strict and rather inflexible. As there are few endings

in English that show person, number, case, and tense, English relies

on word order to show relationships between words in a sentence.

In

Russian, we rely on word endings to tell us how words interact in a

sentence. You probably remember the phrase made up by Academician

L.V. Scherba to demonstrate the work of endings and suffixes in

Russian. (No English translation for this phrase.) Everything we need

to know about the interaction of the characters in this sentence, we

learn from the endings and the suffixes.

English

nouns do not have any case endings (only personal pronouns have some

case endings), so it is mostly the word order that tells you where

things are in a sentence, and how they interact. Compare:

The

dog sees the cat.

Собака

видит

кошку.

The

cat sees the dog.

Кошка

видит

собаку.

The

subject and the object in these sentences are completely the same in

form. How do you know who sees whom? The rules of English word order

tell you that.

Word order patterns

A

sentence is a group of words containing a subject and a predicate and

expressing a complete thought.

Word

order arranges separate words into sentences in a certain way and

indicates where to find the subject, the predicate, and the other

parts of the sentence. Word order and context help to identify the

meanings of individual words.

The

main pattern of basic word order in English declarative sentences is

SUBJECT + PREDICATE + OBJECT, often called SUBJECT + VERB + OBJECT,

for example: Tom writes stories. It means that if these three parts

of the sentence are present in a statement (a declarative sentence),

the subject is placed before the predicate, the predicate follows the

subject, and the object is placed after the predicate. Adverbial

modifiers are placed after the object, and adjectives are placed

before their nouns.

Of

course, some sentences may have just one word (Write!), or only a

subject and a predicate (Tom writes.), or have an adverbial modifier

and no object (Tom writes well.), and there are peculiarities,

exceptions, and preferences in word order, but the pattern SUBJECT +

PREDICATE + OBJECT (Tom writes stories.) is the most typical and the

most common pattern of standard word order in English that serves as

a basis for word order in different types of sentences.

Word order in different sentences

English

sentences are divided into statements, questions, commands, and

exclamatory sentences. Word order in different types of sentences has

certain peculiarities.

Statements (Declarative sentences)

Statements

(declarative sentences) are the most common type of sentences. A

standard statement uses the basic word order pattern, i.e. SUBJECT +

PREDICATE (+ object + adverbial modifier). Adverbial modifiers are

placed at the end of the sentence after the object (or after the verb

if there is no object). Attributes (adjectives, numerals) are placed

before their nouns, and attributes in the form of nouns with

prepositions are placed after their nouns.

Maria

works.

Questions (Interrogative sentences)

General

questions

Auxiliary

verb + subject + main verb (+ object + adverbial modifier):

Do

you smoke?

Special

questions

Question

word + auxiliary verb + subject + main verb (+ object + adverbial

modifier):

Where

does he live?

Alternative

questions

Alternative

questions have the same word order as general questions.

Does

he live in Paris or Rome?

Tag

questions

Tag

questions consist of two parts. The first part has the same word

order as statements, and the second part is a short general question

(the tag).

He

lives here, doesn’t he?

Commands

(Imperative sentences)

Commands

have the same word order as statements, but the subject (you) is

usually omitted.

Go

to your room.

Exclamatory

sentences

Exclamatory

sentences have the same word order as statements (i.e., the subject

is before the predicate).

She

is a great singer!

In

some types of exclamatory sentences, the subject (it, this, that) and

the linking verb are often omitted.

What

a pity!

35.

Syndetic

compound

sentences. Types of relations and their means of expression.

The

sentence is the central syntactic construction used as the minimal

communicative unit that has its primary predication, actualises a

definite structural scheme and possesses definite intonation

characteristics.

Compound

sentences:

A

compound sentence is a multiple sentence of two or more clauses

coordinated with each other. Clauses combined by means of

coordination are regarded as independent, they are linked in such a

way that there is no hierarchy in the syntactic relationship, they

have the same syntactic status. Two clauses are coordinated if they

are connected by a conjunct or a coordinator. Coordinated clauses are

sometimes called “conjoins”. Coordination can be asyndatic

or syndatic.

Syndetic

compound sentences:

In

s.c.c. the type of coordination is expressed explicitly by means of

coordinators, coordinating conjunctions and, but, for, so that The

lights went out, the curtain went up and the show began.

The peculiarity of and

and or is

that they can link more than two clauses. Coordinators can be divided

into one-member, or simple (and, but) and multi-member (either…or).

Coordinators

and conjuncts in a compound sentence express four logical types of

coordination: copulative, disjunctive, adversative and

causative-consecutive.

Form

the semantico-syntactic

point of view there are 2 basic types of connection:

1.Marked

coordinative connection

– copulative, causal, resultative, adversative, disjunctive, e.g.

We cannot go upstairs for we are too tired.

2.Unmarked

coordinative connection

— is realized by the coordinative connector “and” and also

asyndetically (copulative, enumerative, causal, resultative

relations), e.g.

Time passed,

and

she came to no conclusions. We cannot go upstairs, we are too tired.

Grammatical

structure of compound sentences:

The

semantic relations between the clauses making up the compound

sentence depend partly on the lexical meaning of the conjunction

uniting them, and partly on the meanings of the words making up the

clauses themselves:

—Copulative

conjunctions

— and, neither…nor

—Disjunctive

conjunctions

— or, otherwise, either…or

—Adversative

conjunctions

— but, yet, still, nevertheless, however

As

to the use of tenses in clauses making up a compound sentence, we

should note that there is no general rule of their interdependence.

However, in a number of cases we do find interdependence of

co-ordinate clauses from this point of view.

The

number of clauses in a compound sentence may be greater than 2, and

in this case the conjunctions uniting the clauses may be different.

The

length of the CS in terms of the number of its clausal parts is in

principle

unlimited,

since it is determined by the informative purpose of the speaker.

Соседние файлы в предмете [НЕСОРТИРОВАННОЕ]

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #