English word dance comes from Frankish *dansōn (To draw, pull, stretch.), Anglo-Norman dancer

Detailed word origin of dance

| Dictionary entry | Language | Definition |

|---|---|---|

| *dansōn | Frankish (frk) | To draw, pull, stretch. |

| dancer | Anglo-Norman (xno) | |

| *danciō | Vulgar Latin (la-vul) | |

| dancier | Old French (fro) | To dance. |

| dauncer | Anglo-Norman (xno) | |

| daunsen | Middle English (enm) | |

| dance | English (eng) | (heraldiccharge) A normally horizontal stripe called a fess that has been modified to zig-zag across the center of a coat of arms from dexter to sinister.. (uncountable) The art, profession, and study of dancing.. A genre of modern music characterised by sampled beats, repetitive rhythms and few lyrics.. A piece of music with a particular dance rhythm.. A sequence of rhythmic steps or […] |

Words with the same origin as dance

Table of Contents

- Who sang I Love to Love in the 70s?

- What year did Tina Charles I Love To Love?

- What hits did Tina Charles have?

- How old is the singer Tina Charles?

- When did I love to love but my Baby Loves to dance come out?

- When did the song I love to love come out?

- What do you mean by ” I Love Dance “?

- Who is the composer of Dance Little Lady?

The words “dance” and “dancing” come from an old German word “danson,” which means “to stretch.” All dancing is made up of stretching and relaxing. The muscles are tensed for leaping and then relaxed as we make what we hope will be a gentle and graceful landing.

Who sang I Love to Love in the 70s?

TINA became a singing sensation across Europe in 1976 with her number one single I Love To Love. She followed this up with a succession of chart songs and is now recording with Motown legend Lamont Dozier.

What year did Tina Charles I Love To Love?

1976

I Love To Love/Released

Tina Charles (born Tina Hoskins; 10 March 1954) is an English singer who achieved success as a disco artist in the mid to late 1970s. Her most successful single was the UK no. 1 hit “I Love to Love (But My Baby Loves to Dance)” in 1976.

What hits did Tina Charles have?

Tina Charles

| Date | Title, Artist | |

|---|---|---|

| 11.03. 1978 | I’LL GO WHERE YOUR MUSIC TAKES ME TINA CHARLES CBS | Buy Listen |

| amazon itunes | ||

| spotify deezer | ||

| 30.08. 1986 | I LOVE TO LOVE {1986} TINA CHARLES DMC | Buy |

How old is the singer Tina Charles?

67 years (March 10, 1954)

Tina Charles/Age

When did I love to love but my Baby Loves to dance come out?

Versions of “I Love to Love (But My Baby Loves to Dance)” include: Edson Cordeiro. Album Disco Clubbing ao Vivo (1998) ^ Shipments figures based on certification alone. ^ “Quebec scene reflects reach diversity”. Billboard. Nielsen Business Media, Inc.: 64– 2 October 1976. ISSN 0006-2510.

When did the song I love to love come out?

Reaching number 1 on the UK Singles Chart in March 1976 and topping the chart for three weeks, “I Love to Love…” was followed by seven more chart records for Charles; only her Top Ten entries “Dance Little Lady Dance” and “Doctor Love” reached the Top 20.

What do you mean by ” I Love Dance “?

Every once in a while I like to do a little twirl. When you dance, you express your feelings out lively. Dancing can tell stories. Just using your body can tell a story without using any words. That’s why dancing is still blooming in the world, continuing to share stories all over the globe . . .

Who is the composer of Dance Little Lady?

“Dance Little Lady”. (1987) “I Love to Love (But My Baby Loves to Dance)” was a popular single by Tina Charles, from her debut album, I Love to Love; the song was composed by Jack Robinson and James Bolden.

- Adyghe: къашъо (qaašʷo), удж (wudž)

- Afrikaans: dans (af)

- Albanian: vallëzim (sq)

- American Sign Language: V@NearPalm-FingerDown-OpenB@CenterTrunkhigh-PalmUp Sidetoside

- Amharic: ጭፈራ (č̣əfära)

- Antillean Creole: dans, zouk

- Arabic: رَقْص m (raqṣ)

- Egyptian Arabic: رقص m (raʾṣ)

- Hijazi Arabic: رقص m (ragṣ)

- Moroccan Arabic: شطيح (šṭīḥ)

- Armenian: պար (hy) (par)

- Assamese: নাচ (nas), নাচোন (nasün), নৃত্য (nriitto)

- Asturian: baille (ast) m

- Atayal: myugi, mzyugi

- Azerbaijani: rəqs (az), oyun (az)

- Baluchi: ناچ (nác), چاپ (cáp)

- Bashkir: бейеү (beyew)

- Basque: dantza

- Belarusian: та́нец m (tánjec)

- Bengali: নৃত্য (bn) (nritto)

- Bulgarian: танц (bg) m (tanc)

- Burmese: အက (my) (a.ka.)

- Catalan: ball (ca) m, dansa (ca) f

- Chechen: хелхар (xelxar)

- Chickasaw: hilha’

- Chinese:

- Cantonese: 舞蹈 (mou5 dou6), 跳舞 (tiu3 mou5)

- Dungan: тёву (ti͡ovu)

- Mandarin: 舞蹈 (zh) (wǔdǎo), 跳舞 (zh) (tiàowǔ)

- Min Nan: 舞蹈 (zh-min-nan) (bú-tō / bú-tō͘), 跳舞 (zh-min-nan) (thiàu-bú)

- Wu: 舞蹈 (hhu dau), 跳舞 (thiau vu)

- Crimean Tatar: oyun

- Czech: tanec (cs) m

- Danish: dans (da) c

- Dutch: dans (nl)

- Esperanto: danco (eo)

- Estonian: tants

- Ewe: ɣeɖuɖu

- Faroese: dansur m

- Finnish: tanssi (fi)

- French: danse (fr) f

- Galician: danza f, baile (gl) m

- Georgian: ცეკვა (ceḳva)

- German: Tanz (de) m

- Gothic: 𐌻𐌰𐌹𐌺𐍃 m (laiks)

- Greek: χορός (el) m (chorós)

- Ancient: χορός m (khorós), ὄρχησις f (órkhēsis), βαλλισμός m (ballismós)

- Greenlandic: please add this translation if you can

- Haitian Creole: (rhythmic movement) dans, (social gathering) bal

- Hebrew: רִקּוּד (he) m (riqúd), מָחוֹל (he) m (maḥól)

- Hindi: नाच (hi) m (nāc), नृत्य (hi) m (nŕtya)

- Hungarian: tánc (hu)

- Icelandic: dans (is) m

- Ido: danso (io)

- Indonesian: tari (id)

- Interlingua: dansa (ia)

- Irish: damhsa m, rince m

- Italian: ballo (it) m, danza (it) f

- Japanese: ダンス (ja) (dansu), 踊り (ja) (おどり, odori), 舞踊 (ja) (ぶよう, buyō)

- Javanese: joget

- Kabardian: къафэ (qaafe), удж (wudž)

- Kabuverdianu: badju, bóie

- Kalmyk: би (bi)

- Kannada: ನೃತ್ಯ (kn) (nṛtya)

- Kapampangan: terak

- Kashmiri: ناچ (nāc)

- Kazakh: би (kk) (bi)

- Khmer: របាំ (km) (rɔbam), នាដ (km) (niət)

- Korean: 춤 (ko) (chum), 댄스 (ko) (daenseu)

- Kurdish:

- Central Kurdish: لەنجە (lence), سەما (ckb) (sema)

- Northern Kurdish: dans (ku) f, sema (ku) f, reqis (ku) f, dîlan (ku) f, govend (ku) f, dawet (ku) f

- Kyrgyz: бий (ky) (biy), танец (ky) (tanets)

- Lao: ນັດຈະ (nat cha)

- Ladin: bal m

- Latin: saltatio f, tripudium n, saltatus m

- Latvian: deja f, dancis m (dated, folkloric)

- Lithuanian: šokis (lt) m

- Luxembourgish: Danz m

- Lü: please add this translation if you can

- Macedonian: танц m (tanc)

- Malay: tari

- Malayalam: ആട്ടം (ml) (āṭṭaṃ), നാട്യം (ml) (nāṭyaṃ), നൃത്തം (ml) (nr̥ttaṃ)

- Maltese: żfin

- Manchu: ᠮᠠᡴᠰᡳᠨ (maksin)

- Maori: kanikani

- Marathi: नाच (nāc), नृत्य (mr) (nrutya)

- Mongolian: бүжиг (mn) (büžig), танц (tanc)

- Navajo: azhish

- Neapolitan: ballà

- Norman: dànserie f (Guernsey), dans’sie f (Jersey), daunche f (continental Normandy)

- Northern Ohlone: irshah, hánaikis, ló̄le (women’s dance)

- Northern Sami: dánsa, dánsu

- Norwegian:

- Bokmål: dans (no) m

- Nynorsk: dans (no) m

- Ossetian: кафт (kaft)

- Old English: frīcian

- Pashto: رقص (ps) m (raqs), ډانس (ps) m (ḍāns), ناچ (ps) m (nāč), رخس m (raxs)

- Persian: رقص (fa) (raqs), دانس (fa) (dâns), پایکوبی (fa) (pâykubi) (archaic)

- Middle Persian: nart

- Plautdietsch: Dauns m

- Polish: taniec (pl) m, pląs m (literally)

- Portuguese: dança (pt) f, baile (pt) m

- Punjabi: ਡਾਂਸ (ḍāns)

- Quechua: tusuy (qu)

- Romagnol: bal m

- Romanian: dans (ro)

- Romansch: saut m (Rumantsch Grischun), sault m (Sursilvan), sòlt m (Sutsilvan), solt m (Surmiran), sot m (Puter, Vallader)

- Russian: та́нец (ru) m (tánec), пляс (ru) m (pljas), пля́ска (ru) f (pljáska)

- Rusyn: та́нець m (tánecʹ)

- Sanskrit: नटनम् (sa) n (naṭanam), नाट्यम् (sa) (nāṭyam), नृत्तम् (sa) (nṛttam), नट (sa) m (naṭa)

- Scottish Gaelic: dannsa m

- Serbo-Croatian:

- Cyrillic: плес m, игранка f, танац m

- Roman: ples (sh) m, igranka (sh) f, tanac (sh) m

- Shan: please add this translation if you can

- Slovak: tanec m

- Slovene: ples (sl) m

- Southern Altai: бийе (biye) , бије (biǰe)

- Southern Ohlone: ruune, mooloy (women’)

- Spanish: baile (es) m, danza (es) f

- Swahili: ngoma (sw), dansi, densi (sw)

- Swedish: dans (sv) c

- Sylheti: ꠘꠣꠌ (nas)

- Tagalog: sayaw, indak

- Tajik: рақс (tg) (raqs)

- Tamil: ஆடல் (ta) (āṭal), கூத்து (ta) (kūttu), நடனம் (ta) (naṭaṉam)

- Taos: tò’óne

- Telugu: నృత్యం (te) (nr̥tyaṁ)

- Thai: เต้นรำ (dtên-ram)

- Tibetan: ཞབས་བྲོ (zhabs bro)

- Turkish: dans (tr), raks (tr), bar (tr)

- Turkmen: tans

- Ugaritic: 𐎎𐎗𐎖𐎄 (mrqd)

- Ukrainian: та́нець m (tánecʹ), та́нок m (tánok)

- Urdu: رقص m (raqs), ناچ m (nāc), نرتیہ m (nŕtya)

- Uyghur: تانسا (tansa), رەقس (reqs)

- Uzbek: raqs (uz), tansa (uz)

- Vietnamese: (art) điệu múa, (movements and steps) điệu nhảy

- Volapük: danüd (vo), (sword) glävadanüd

- Walloon: danse (wa) f

- Welsh: dawns (cy)

- Yakut: үҥкүү (üñküü)

- Yiddish: טאַנץ (tants)

- Yucatec Maya: óok’ot

Dance is an art form consisting of sequences of body movements with aesthetic and often symbolic value, either improvised or purposefully selected.[nb 1] Dance can be categorized and described by its choreography, by its repertoire of movements, done simultaneously with music or with instruments; or by its historical period or place of origin.[4]

An important distinction is to be drawn between the contexts of theatrical and participatory dance,[5] although these two categories are not always completely separate; both may have special functions, whether social, ceremonial, competitive, erotic, martial, sacred or liturgical. Other forms of human movement are sometimes said to have a dance-like quality, including martial arts, gymnastics, cheerleading, figure skating, synchronized swimming, marching bands, and many other forms of athletics. Dance is not solely restricted to performance, though, as dance is used as a form of exercise and occasionally training for other sports and activities. Dance itself has also become a sport for some, with dancing competitions found across the world exhibiting various different styles and standards.

Dance requires an equal amount of cognitive focus as well as physical strength. The demanding yet evolving art form allows individuals to express themselves creatively through movement, while enabling them to adapt movement that possesses a rhythmical pattern and fluid motions that allure an audience either onstage or on film. Dance is considered to be a very aesthetically pleasing art form.[6]

Performance and participation[edit]

Members of an American jazz dance company perform a formal group routine in a concert dance setting

Theatrical dance, also called performance or concert dance, is intended primarily as a spectacle, usually a performance upon a stage by virtuoso dancers. It often tells a story, perhaps using mime, costume and scenery, or else it may interpret the musical accompaniment, which is often specially composed and performed in a theatre setting but it is not a requirement. Examples are western ballet and modern dance, Classical Indian dance such as Bharatanatyam and Chinese and Japanese song and dance dramas such as dragon dance. Most classical forms are centred upon dance alone, but performance dance may also appear in opera and other forms of musical theatre.[clarification needed]

Participatory dance, on the other hand, whether it be a folk dance, a social dance, a group dance such as a line, circle, chain or square dance, or a partner dance such as is common in Western ballroom dancing, is undertaken primarily for a common purpose, such as social interaction or exercise, or building flexibility of participants rather than to serve any benefit to onlookers. Such dance seldom has any narrative. A group dance and a corps de ballet, a social partner dance and a pas de deux, differ profoundly. Even a solo dance may be undertaken solely for the satisfaction of the dancer. Participatory dancers often all employ the same movements and steps but, for example, in the rave culture of electronic dance music, vast crowds may engage in free dance, uncoordinated with those around them. On the other hand, some cultures lay down strict rules as to the particular dances in which, for example, men, women, and children may or must participate.

History[edit]

Mesolithic dancers at Bhimbetka

Archaeological evidence for early dance includes 10,000-years-old paintings in Madhya Pradesh, India at the Rock Shelters of Bhimbetka,[7] and Egyptian tomb paintings depicting dancing figures, dated c. 3300 BC. It has been proposed that before the invention of written languages, dance was an important part of the oral and performance methods of passing stories down from one generation to the next.[8] The use of dance in ecstatic trance states and healing rituals (as observed today in many contemporary «primitive» cultures, from the Brazilian rainforest to the Kalahari Desert) is thought to have been another early factor in the social development of dance.[9]

Dancers and musicians on a Sasanian bowl, Iran

References to dance can be found in very early recorded history; Greek dance (horos) is referred to by Plato, Aristotle, Plutarch and Lucian.[10] The Bible and Talmud refer to many events related to dance, and contain over 30 different dance terms.[11] In Chinese pottery as early as the Neolithic period, groups of people are depicted dancing in a line holding hands,[12] and the earliest Chinese word for «dance» is found written in the oracle bones.[13] Dance is further described in the Lüshi Chunqiu.[14][15] Primitive dance in ancient China was associated with sorcery and shamanic rituals.[16]

Greek bronze statuette of a veiled and masked dancer, 3rd–2nd century BC, Alexandria, Egypt

During the first millennium BCE in India, many texts were composed which attempted to codify aspects of daily life. Bharata Muni’s Natyashastra (literally «the text of dramaturgy») is one of the earlier texts. It mainly deals with drama, in which dance plays an important part in Indian culture. It categorizes dance into four types—secular, ritual, abstract, and, interpretive—and into four regional varieties. The text elaborates various hand-gestures (mudras) and classifies movements of the various limbs, steps and so on. A strong continuous tradition of dance has since continued in India, through to modern times, where it continues to play a role in culture, ritual, and, notably, the Bollywood entertainment industry. Many other contemporary dance forms can likewise be traced back to historical, traditional, ceremonial, and ethnic dance.

Music[edit]

Dance is generally, however not exclusively, performed with the accompaniment of music and may or may not be performed in time to such music. Some dance (such as tap dance) may provide its own audible accompaniment in place of (or in addition to) music. Many early forms of music and dance were created for each other and are frequently performed together. Notable examples of traditional dance-music couplings include the jig, waltz, tango, disco, and salsa. Some musical genres have a parallel dance form such as baroque music and baroque dance; other varieties of dance and music may share nomenclature but developed separately, such as classical music and classical ballet. The choreography and music go hand in hand, as they complement each other to express a story told by the choreographer and or dancers.[17]

Rhythm[edit]

Rhythm and dance are deeply linked in history and practice. The American dancer Ted Shawn wrote; «The conception of rhythm which underlies all studies of the dance is something about which we could talk forever, and still not finish.»[18] A musical rhythm requires two main elements; first, a regularly-repeating pulse (also called the «beat» or «tactus») that establishes the tempo and, second, a pattern of accents and rests that establishes the character of the metre or basic rhythmic pattern. The basic pulse is roughly equal in duration to a simple step or gesture.

Dances generally have a characteristic tempo and rhythmic pattern. The tango, for example, is usually danced in 2

4 time at approximately 66 beats per minute. The basic slow step, called a «slow», lasts for one beat, so that a full «right–left» step is equal to one 2

4 measure. The basic forward and backward walk of the dance is so counted – «slow-slow» – while many additional figures are counted «slow – quick-quick.[19]

Just as musical rhythms (e.g., drum beats) are defined by a pattern of strong and weak beats, so repetitive body movements often depend on alternating «strong» and «weak» muscular movements.[20] Given this alternation of left-right, of forward-backward and rise-fall, along with the bilateral symmetry of the human body, it is natural that many dances and much music are in duple and quadruple meter. Since some such movements require more time in one phase than the other – such as the longer time required to lift a hammer than to strike – some dance rhythms fall equally naturally into triple metre.[21] Occasionally, as in the folk dances of the Balkans, dance traditions depend heavily on more complex rhythms. Further, complex dances composed of a fixed sequence of steps always require phrases and melodies of a certain fixed length to accompany that sequence.

Lululaund – The Dancing Girl (painting and silk cloth. A.L. Baldry 1901, before p. 107), The inscription reads; «Dancing is a form of rhythm/ Rhythm is a form of music/ Music is a form of thought/ And thought is a form of divinity.»

The very act of dancing, the steps themselves, generate an «initial skeleton of rhythmic beats» that must have preceded any separate musical accompaniment, while dance itself, as much as music, requires time-keeping[22] just as utilitarian repetitive movements such as walking, hauling and digging take on, as they become refined, something of the quality of dance.[20]

Musical accompaniment, therefore, arose in the earliest dance, so that ancient Egyptians attributed the origin of the dance to the divine Athotus, who was said to have observed that music accompanying religious rituals caused participants to move rhythmically and to have brought these movements into proportional measure. The same idea, that dance arises from musical rhythm, is still found in renaissance Europe in the works of the dancing master Guglielmo Ebreo da Pesaro who speaks of dance as a physical movement that arises from and expresses inward, spiritual motion agreeing with the «measures and perfect concords of harmony» that fall upon the human ear,[20] while, earlier, Mechthild of Magdeburg, seizing upon dance as a symbol of the holy life foreshadowed in Jesus’ saying «I have piped and ye have not danced»,[23] writes;

I can not dance unless thou leadest. If thou wouldst have me spring aloft, sing thou and I will spring, into love and from love to knowledge and from knowledge to ecstasy above all human sense[24]

Thoinot Arbeau’s celebrated 16th-century dance-treatise Orchésographie, indeed, begins with definitions of over eighty distinct drum-rhythms.[25]

As has been shown above, dance has been represented through the ages as having emerged as a response to music yet, as Lincoln Kirstein implied, it is at least as likely that primitive music arose from dance. Shawn concurs, stating that dance «was the first art of the human race, and the matrix out of which all other arts grew» and that even the «metre in our poetry today is a result of the accents necessitated by body movement, as the dancing and reciting was performed simultaneously»[18] – an assertion somewhat supported by the common use of the term «foot» to describe the fundamental rhythmic units of poetry.

Scholes, not a dancer but a musician, offers support for this view, stating that the steady measures of music, of two, three or four beats to the bar, its equal and balanced phrases, regular cadences, contrasts and repetitions, may all be attributed to the «incalculable» influence of dance upon music.[26]

Émile Jaques-Dalcroze, primarily a musician and teacher, relates how a study of the physical movements of pianists led him «to the discovery that musical sensations of a rhythmic nature call for the muscular and nervous response of the whole organism», to develop «a special training designed to regulate nervous reactions and effect a co-ordination of muscles and nerves» and ultimately to seek the connections between «the art of music and the art of dance», which he formulated into his system of eurhythmics.[27] He concluded that «musical rhythm is only the transposition into sound of movements and dynamisms spontaneously and involuntarily expressing emotion».[28]

Hence, though doubtless, as Shawn asserts, «it is quite possible to develop the dance without music and… music is perfectly capable of standing on its own feet without any assistance from the dance», nevertheless the «two arts will always be related and the relationship can be profitable both to the dance and to music»,[29] the precedence of one art over the other being a moot point. The common ballad measures of hymns and folk-songs takes their name from dance, as does the carol, originally a circle dance. Many purely musical pieces have been named «waltz» or «minuet», for example, while many concert dances have been produced that are based upon abstract musical pieces, such as 2 and 3 Part Inventions, Adams Violin Concerto and Andantino. Similarly, poems are often structured and named after dances or musical works, while dance and music have both drawn their conception of «measure» or «metre» from poetry.

Shawn quotes with approval the statement of Dalcroze that, while the art of musical rhythm consists in differentiating and combining time durations, pauses and accents «according to physiological law», that of «plastic rhythm» (i.e. dance) «is to designate movement in space, to interpret long time-values by slow movements and short ones by quick movements, regulate pauses by their divers successions and express sound accentuations in their multiple nuances by additions of bodily weight, by means of muscular innervations».

Shawn nevertheless points out that the system of musical time is a «man-made, artificial thing…. a manufactured tool, whereas rhythm is something that has always existed and depends on man not at all», being «the continuous flowing time which our human minds cut up into convenient units», suggesting that music might be revivified by a return to the values and the time-perception of dancing.[30]

The early-20th-century American dancer Helen Moller stated that «it is rhythm and form more than harmony and color which, from the beginning, has bound music, poetry and dancing together in a union that is indissoluble.»[31]

Approaches[edit]

Theatrical[edit]

Concert dance, like opera, generally depends for its large-scale form upon a narrative dramatic structure. The movements and gestures of the choreography are primarily intended to mime the personality and aims of the characters and their part in the plot.[32] Such theatrical requirements tend towards longer, freer movements than those usual in non-narrative dance styles. On the other hand, the ballet blanc, developed in the 19th century, allows interludes of rhythmic dance that developed into entirely «plotless» ballets in the 20th century[33] and that allowed fast, rhythmic dance-steps such as those of the petit allegro. A well-known example is The Cygnets’ Dance in act two of Swan Lake.

The ballet developed out of courtly dramatic productions of 16th- and 17th-century France and Italy and for some time dancers performed dances developed from those familiar from the musical suite,[34] all of which were defined by definite rhythms closely identified with each dance. These appeared as character dances in the era of romantic nationalism.

Ballet reached widespread vogue in the romantic era, accompanied by a larger orchestra and grander musical conceptions that did not lend themselves easily to rhythmic clarity and by dance that emphasised dramatic mime. A broader concept of rhythm was needed, that which Rudolf Laban terms the «rhythm and shape» of movement that communicates character, emotion and intention,[35] while only certain scenes required the exact synchronisation of step and music essential to other dance styles, so that, to Laban, modern Europeans seemed totally unable to grasp the meaning of «primitive rhythmic movements»,[36] a situation that began to change in the 20th century with such productions as Igor Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring with its new rhythmic language evoking primal feelings of a primitive past.[37]

Indian classical dance styles, like ballet, are often in dramatic form, so that there is a similar complementarity between narrative expression and «pure» dance. In this case, the two are separately defined, though not always separately performed. The rhythmic elements, which are abstract and technical, are known as nritta. Both this and expressive dance (nritya), though, are closely tied to the rhythmic system (tala). Teachers have adapted the spoken rhythmic mnemonic system called bol to the needs of dancers.

Japanese classical dance-theatre styles such as Kabuki and Noh, like Indian dance-drama, distinguish between narrative and abstract dance productions. The three main categories of kabuki are jidaimono (historical), sewamono (domestic) and shosagoto (dance pieces).[38] Somewhat similarly, Noh distinguishes between Geki Noh, based around the advancement of plot and the narration of action, and Furyū Noh, dance pieces involving acrobatics, stage properties, multiple characters and elaborate stage action.[39]

Participatory and social[edit]

A contra dance, a form of participatory social folk dance with mixed European roots

Social dances, those intended for participation rather than for an audience, may include various forms of mime and narrative, but are typically set much more closely to the rhythmic pattern of music, so that terms like waltz and polka refer as much to musical pieces as to the dance itself. The rhythm of the dancers’ feet may even form an essential part of the music, as in tap dance. African dance, for example, is rooted in fixed basic steps, but may also allow a high degree of rhythmic interpretation: the feet or the trunk mark the basic pulse while cross-rhythms are picked up by shoulders, knees, or head, with the best dancers simultaneously giving plastic expression to all the elements of the polyrhythmic pattern.[40]

Cultural traditions[edit]

Africa[edit]

Ugandan youth dance at a cultural celebration of peace

Dance in Africa is deeply integrated into society and major events in a community are frequently reflected in dances: dances are performed for births and funerals, weddings and wars.[41]: 13 Traditional dances impart cultural morals, including religious traditions and sexual standards; give vent to repressed emotions, such as grief; motivate community members to cooperate, whether fighting wars or grinding grain; enact spiritual rituals; and contribute to social cohesiveness.[42]

Thousands of dances are performed around the continent. These may be divided into traditional, neotraditional, and classical styles: folkloric dances of a particular society, dances created more recently in imitation of traditional styles, and dances transmitted more formally in schools or private lessons.[41]: 18 African dance has been altered by many forces, such as European missionaries and colonialist governments, who often suppressed local dance traditions as licentious or distracting.[42] Dance in contemporary African cultures still serves its traditional functions in new contexts; dance may celebrate the inauguration of a hospital, build community for rural migrants in unfamiliar cities, and be incorporated into Christian church ceremonies.[42][43]

Asia[edit]

An Indian classical dancer

In the Mintha Theater (Mandalay) a master teacher of the Inwa School of Performing Arts demonstrates traditional hand movements.

All Indian classical dances are to varying degrees rooted in the Natyashastra and therefore share common features: for example, the mudras (hand positions), some body positions, leg movement and the inclusion of dramatic or expressive acting or abhinaya. Indian classical music provides accompaniment and dancers of nearly all the styles wear bells around their ankles to counterpoint and complement the percussion.

There are now many regional varieties of Indian classical dance. Dances like «Odra Magadhi», which after decades-long debate, has been traced to present day Mithila, Odisha region’s dance form of Odissi (Orissi), indicate influence of dances in cultural interactions between different regions.[44]

The Punjab area overlapping India and Pakistan is the place of origin of Bhangra. It is widely known both as a style of music and a dance. It is mostly related to ancient harvest celebrations, love, patriotism or social issues. Its music is coordinated by a musical instrument called the ‘Dhol’. Bhangra is not just music but a dance, a celebration of the harvest where people beat the dhol (drum), sing Boliyaan (lyrics) and dance. It developed further with the Vaisakhi festival of the Sikhs.

The dances of Sri Lanka include the devil dances (yakun natima), a carefully crafted ritual reaching far back into Sri Lanka’s pre-Buddhist past that combines ancient «Ayurvedic» concepts of disease causation with psychological manipulation and combines many aspects including Sinhalese cosmology. Their influence can be seen on the classical dances of Sri Lanka.[45]

Indonesian dances reflect the richness and diversity of Indonesian ethnic groups and cultures. There are more than 1,300 ethnic groups in Indonesia, it can be seen from the cultural roots of the Austronesian and Melanesian peoples, and various cultural influences from Asia and the west. Dances in Indonesia originate from ritual movements and religious ceremonies, this kind of dance usually begins with rituals, such as war dances, shaman dances to cure or ward off disease, dances to call rain and other types of dances. With the acceptance of dharma religion in the 1st century in Indonesia, Hinduism and Buddhist rituals were celebrated in various artistic performances. Hindu epics such as the Ramayana, Mahabharata and also the Panji became the inspiration to be shown in a dance-drama called «Sendratari» resembling «ballet» in the western tradition. An elaborate and highly stylized dance method was invented and has survived to this day, especially on the islands of Java and Bali. The Javanese Wayang wong dance takes footage from the Ramayana or Mahabharata episodes, but this dance is very different from the Indian version, indonesian dances do not pay as much attention to the «mudras» as Indian dances: even more to show local forms. The sacred Javanese ritual dance Bedhaya is believed to date back to the Majapahit period in the 14th century or even earlier, this dance originated from ritual dances performed by virgin girls to worship Hindu Gods such as Shiva, Brahma, and Vishnu. In Bali, dance has become an integral part of the sacred Hindu Dharma rituals. Some experts believe that Balinese dance comes from an older dance tradition from Java. Reliefs from temples in East Java from the 14th century feature crowns and headdresses similar to the headdresses used in Balinese dance today. Islam began to spread to the Indonesian archipelago when indigenous dances and dharma dances were still popular. Artists and dancers still use styles from the previous era, replacing stories with more Islamic interpretations and clothing that is more closed according to Islamic teachings.[46]

The dances of the Middle East are usually the traditional forms of circle dancing which are modernized to an extent. They would include dabke, tamzara, Assyrian folk dance, Kurdish dance, Armenian dance and Turkish dance, among others.[47][48] All these forms of dances would usually involve participants engaging each other by holding hands or arms (depending on the style of the dance). They would make rhythmic moves with their legs and shoulders as they curve around the dance floor. The head of the dance would generally hold a cane or handkerchief.[47][49]

Europe and North America[edit]

Folk dances vary across Europe and may date back hundreds or thousands of years, but many have features in common such as group participation led by a caller, hand-holding or arm-linking between participants, and fixed musical forms known as caroles.[50] Some, such as the maypole dance are common to many nations, while others such as the céilidh and the polka are deeply-rooted in a single culture. Some European folk dances such as the square dance were brought to the New World and subsequently became part of American culture.

Two classical ballet dancers perform a sequence of The Nutcracker, one of the best known works of classical dance.

Ballet developed first in Italy and then in France from lavish court spectacles that combined music, drama, poetry, song, costumes and dance. Members of the court nobility took part as performers. During the reign of Louis XIV, himself a dancer, dance became more codified. Professional dancers began to take the place of court amateurs, and ballet masters were licensed by the French government. The first ballet dance academy was the Académie Royale de Danse (Royal Dance Academy), opened in Paris in 1661. Shortly thereafter, the first institutionalized ballet troupe, associated with the Academy, was formed; this troupe began as an all-male ensemble but by 1681 opened to include women as well.[8]

20th century concert dance brought an explosion of innovation in dance style characterized by an exploration of freer technique. Early pioneers of what became known as modern dance include Loie Fuller, Isadora Duncan, Mary Wigman and Ruth St. Denis. The relationship of music to dance serves as the basis for Eurhythmics, devised by Emile Jaques-Dalcroze, which was influential to the development of Modern dance and modern ballet through artists such as Marie Rambert. Eurythmy, developed by Rudolf Steiner and Marie Steiner-von Sivers, combines formal elements reminiscent of traditional dance with the new freer style, and introduced a complex new vocabulary to dance. In the 1920s, important founders of the new style such as Martha Graham and Doris Humphrey began their work. Since this time, a wide variety of dance styles have been developed; see Modern dance.

African American dance developed in everyday spaces, rather than in dance studios, schools or companies. Tap dance, disco, jazz dance, swing dance, hip hop dance, the lindy hop with its relationship to rock and roll music and rock and roll dance have had a global influence. Dance styles fusing classical ballet technique with African-American dance have also appeared in the 21st century, including Hiplet.[51]

Latin America[edit]

Street samba dancers perform in carnival parades and contests.

Dance is central to Latin American social life and culture. Brazilian Samba, Argentinian tango, and Cuban salsa are internationally popular partner dances, and other national dances—merengue, cueca, plena, jarabe, joropo, marinera, cumbia, bachata and others—are important components of their respective countries’ cultures.[52] Traditional Carnival festivals incorporate these and other dances in enormous celebrations.[53]

Dance has played an important role in forging a collective identity among the many cultural and ethnic groups of Latin America.[54] Dance served to unite the many African, European, and indigenous peoples of the region.[52] Certain dance genres, such as capoeira, and body movements, especially the characteristic quebradas or pelvis swings, have been variously banned and celebrated throughout Latin American history.[54]

Education[edit]

A dancer practices in a dance studio, the primary setting for training in classical dance and many other styles.

Dance studies are offered through the arts and humanities programs of many higher education institutions. Some universities offer Bachelor of Arts and higher academic degrees in Dance. A dance study curriculum may encompass a diverse range of courses and topics, including dance practice and performance, choreography, ethnochoreology, kinesiology, dance notation, and dance therapy. Most recently, dance and movement therapy has been integrated in some schools into math lessons for students with learning disabilities, emotional or behavioral disabilities, as well as for those with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).[55]

Occupations[edit]

Dancers[edit]

Professional dancers are usually employed on contract or for particular performances or productions. The professional life of a dancer is generally one of constantly changing work situations, strong competitive pressure and low pay. Consequently, professional dancers often must supplement their incomes to achieve financial stability. In the U.S. many professional dancers belong to unions (such as the American Guild of Musical Artists, Screen Actors Guild and Actors’ Equity Association) that establish working conditions and minimum salaries for their members. Professional dancers must possess large amounts of athleticism. To lead a successful career, it is advantageous to be versatile in many styles of dance, have a strong technical background and to use other forms of physical training to remain fit and healthy.[56]

Teachers[edit]

Dance teachers typically focus on teaching dance performance, or coaching competitive dancers, or both. They typically have performance experience in the types of dance they teach or coach. For example, dancesport teachers and coaches are often tournament dancers or former dancesport performers. Dance teachers may be self-employed, or employed by dance schools or general education institutions with dance programs. Some work for university programs or other schools that are associated with professional classical dance (e.g., ballet) or modern dance companies. Others are employed by smaller, privately owned dance schools that offer dance training and performance coaching for various types of dance.[57]

Choreographers[edit]

Choreographers are the ones that design the dancing movements within a dance, they are often university trained and are typically employed for particular projects or, more rarely may work on contract as the resident choreographer for a specific dance company.[58][59]

Competitions[edit]

A dance competition is an organized event in which contestants perform dances before a judge or judges for awards, and in some cases, monetary prizes. There are several major types of dance competitions, distinguished primarily by the style or styles of dances performed. Dance competitions are an excellent setting to build connections with industry leading faculty members, adjudicators, choreographers and other dancers from competing studios. A typical dance competition for younger pre-professional dancers can last anywhere between two and four days, depending whether it is a regional or national competition.

The purpose of dance competitions is to provide a fun and educative place for dancers and give them the opportunity to perform their choreographed routines from their current dance season onstage. Oftentimes, competitions will take place in a professional setting or may vary to non-performance spaces, such as a high school theatre. The results of the dancers are then dictated by a credible panel of judges and are evaluated on their performance than given a score. As far as competitive categories go, most competitions base their categories according to the dance style, age, experience level and the number of dancers competing in the routine.[60] Major types of dance competitions include:

- Dancesport, which is focused exclusively on ballroom and latin dance.

- Competitive dance, in which a variety of theater dance styles, such as acrobatics, ballet, jazz, hip-hop, lyrical, stepping, and tap, are permitted.

- Commercial Dance, consisting of as hip hop, jazz, locking, popping, breakdancing, contemporary etc.[60]

- Single-style competitions, such as; highland dance, dance team, and Irish dance, that only permit a single dance style.

- Open competitions, that permit a wide variety of dance styles. An example of this is the TV program So You Think You Can Dance.

- Olympic, Dance has been trying to be part of the Olympic sport since 1930s.

Televised Dance Competitions[edit]

There are numerous dance competition shows presented on television and other mass media outlets including, NBC’s World Of Dance, NBC’s Dancing With Myself, Dancing With The Stars, etc.

Dance diplomacy[edit]

During the 1950s and 1960s, cultural exchange of dance was a common feature of international diplomacy, especially amongst East and South Asian nations. The People’s Republic of China, for example, developed a formula for dance diplomacy that sought to learn from and express respect for the aesthetic traditions of recently independent states that were former European colonies, such as Indonesia, India, and Burma, as a show of anti-colonial solidarity.[61]

Health[edit]

Footwear[edit]

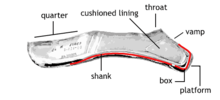

In most forms of dance the foot is the source of movement, and in some cases require specific shoes to aid in the health, safety ability of the dancer, depending on the type of dance, the intensity of the movements, and the surface that will be danced on.

Dance footwear can be potentially both supportive and or restrictive to the movement of the dancer.[62] The effectiveness of the shoe is related to its ability to help the foot do something it is not intended to do, or to make easier a difficult movement. Such effects relate to health and safety because of the function of the equipment as unnatural to the bodies usual mobility.

Ballet[edit]

Ballet is notable for the risks of injury due to the biomechanics of the ankle and the toes as the main support for the rest of the movements. With the pointe shoe, the design specifically brings all of the toes together to allow the toes to be stood on for longer periods of time.[63]

There are accessories associated with pointe shoes that help to mitigate injury and soothe pain while dancing, including things such as toe pads, toe tape, and cushions.[64]

Body Image[edit]

Dancers are publicly thought to be very preoccupied with their body image to fit a certain mold in the industry. Research indicates that dancers do have greater difficulty controlling their eating habits as a large quantity strive for the art-form’s ideal body mass. Some dancers often resort to abusive tactics to maintain a certain image. Common scenarios include dancers abusing laxatives for weight control and end up falling into unhealthy eating disorders. Studies show that a large quantity of dancers use at least one method of weight control including over exercising and food restriction. The pressure for dancers to maintain a below average weight affects their eating and weight controlling behaviours and their life-style.[65] Due to its artistic nature, dancers tend to have many hostile self-critical tendencies. Commonly seen in performers, it is likely that a variety of individuals may be resistant to concepts of self-compassion.[66]

Eating Disorders

Eating disorders in dancers are generally very publicly common. Through data analysis and studies published, sufficient data regarding the percentage and accuracy dancers have of realistically falling into unhealthy disordered eating habits or the development of an eating disorder were extracted. Dancers, in general, have a higher risk of developing eating disorders than the general public, primarily falling into anorexia nervosa and EDNOS. Research has yet to distinguish a direct correlation regarding dancers having a higher risk of developing bulimia nervosa. Studies concluded that dancers overall have a three times higher risk of developing eating disorders, more specifically anorexia nervosa and EDNOS.[67]

[edit]

TikTok[edit]

Dance has become a fundamental aspect of the popular app and a primary category influencing the youth’s culture today. Dance challenges have become a popular form of content across many social media platforms including TikTok. During 2020, TikTok dances offered an escape for isolated individuals to play and connect with one another through virtual format.[68] With TikTok’s easy accessibility to a variety of different filters and special effects, the app made filming yourself dancing to music a fun and easy past time. Since its debut back in 2017, the app attracted a small but growing audience of professional dancers in their early 20s to 30s. While the majority of this demographic is more accustomed to performing onstage, this app introduced a new era of dancing onscreen.[69]

Gallery[edit]

-

-

A contemporary dancer performs a stag split leap.

-

A dancer performs a «toe rise», in which she rises from a kneeling position to a standing position on the tops of her feet.

-

Latin Ballroom dancers perform the Tango.

-

Gumboot dance evolved from the stomping signals used as coded communication between labourers in South African mines.

-

-

-

Modern dance – a female dancer performs a leg split while balanced on the back of her partner.

-

A nineteenth century artist’s representation of a Flamenco dancer

-

Ritual dance – Armenian folk dancers celebrate a neo-pagan new year.

-

A latin ballroom couple perform a Samba routine at a dancesport event.

-

Folk dance – some dance traditions travel with immigrant communities, as with this festival dance performed by a Polish community in Turkey.

-

Street dance – a Breakdancer performs a handstand trick.

-

-

Ballet class of young girls wearing leotards and skirts in 2017

-

See also[edit]

- Art

- Outline of performing arts

- Outline of dance

- Index of dance articles

- List of dance awards

- Human body

- List of dancers

Notes[edit]

- ^ Many definitions of dance have been proposed. This definition is based on the following:

«Dance is human movement created and expressed for an aesthetic purpose. Dance is also a source of entertainment «[1]

«Dance is a transient mode of expression performed in a given form and style by the human body moving in space. Dance occurs through purposefully selected and controlled rhythmic movements; the resulting phenomenon is recognized as dance both by the performer and the observing members of a given group.»[2]

«Dance is human behaviour composed (from the dancer’s perspective, which is usually shared by the audience members of the dancer’s culture) of purposeful (individual choice and social learning play a role), intentionally rhythmical, and culturally patterned sequences of nonverbal body movement mostly other than those performed in ordinary motor activities. The motion (in time, space, and with effort) has an inherent and aesthetic value (the notion of appropriateness and competency as viewed by the dancer’s culture) and symbolic potential.»[3]

References[edit]

- ^ Sondra Horton Fraleigh (1987). Dance and the Lived Body: A Descriptive Aesthetics. University of Pittsburgh Pre. p. 49. ISBN 978-0-8229-7170-2.

- ^ Joann Kealinohomoku (1970). Copeland, Roger; Cohen, Marshall (eds.). An Anthropologist Looks at Ballet as a Form of Ethnic Dance (PDF). What is Dance? Readings in Theory and Criticism (1983 ed.). New York: Oxford University Press. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-01-04.

- ^ Judith Lynne Hanna (1983). The performer-audience connection: emotion to metaphor in dance and society. University of Texas Press. ISBN 978-0-292-76478-1.

- ^ Foster, Susan Leigh. (2011). Choreographing empathy : kinesthesia in performance. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-59656-5. OCLC 963558371.

- ^ «Canadian National Arts Centre – Dance Forms: An Introduction». Arts Alive. Archived from the original on Apr 16, 2021.

- ^ Carey, Katy; Moran, Aidan; Rooney, Brendan (2019-03-01). «Learning Choreography: An Investigation of Motor Imagery, Attentional Effort, and Expertise in Modern Dance». Frontiers in Psychology. 10: 422. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00422. ISSN 1664-1078. PMC 6405914. PMID 30881331.

- ^ Mathpal, Yashodhar (1984). Prehistoric Painting Of Bhimbetka. Abhinav Publications. p. 220. ISBN 9788170171935.

- ^ a b Nathalie Comte. «Europe, 1450 to 1789: Encyclopedia of the Early Modern World». Ed. Jonathan Dewald. Vol. 2. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 2004. pp 94–108.

- ^ Guenther, Mathias Georg. ‘The San Trance Dance: Ritual and Revitalization Among the Farm Bushmen of the Ghanzi District, Republic of Botswana.’ Journal, South West Africa Scientific Society, v. 30, 1975–76.

- ^ Raftis, Alkis, The World of Greek Dance Finedawn, Athens (1987) p25.

- ^ Kadman, Gurit (1952). «Yemenite Dances and Their Influence on the New Israeli Folk Dances». Journal of the International Folk Music Council. 4: 27–30. doi:10.2307/835838. JSTOR 835838.

- ^ «Basin with design of dancers». National Museum of China. Archived from the original on 2017-08-11. Retrieved 2017-05-23. Pottery from the Majiayao culture (3100 BC to 2700 BC)

- ^ Kʻo-fen, Wang (1985). The history of Chinese dance. Foreign Languages Press. p. 7. ISBN 978-0-8351-1186-7. OCLC 977028549.

- ^ Li, Zehou; Samei, Maija Bell (2010). The Chinese aesthetic tradition. University of Hawaiʻi Press. p. 5. ISBN 978-0-8248-3307-7. OCLC 960030161.

- ^ Sturgeon, Donald. «Lü Shi Chun Qiu». Chinese Text Project Dictionary (in Chinese). Retrieved 2017-05-23.

Original text: 昔葛天氏之樂,三人操牛尾,投足以歌八闋

- ^ Schafer, Edward H. (June 1951). «Ritual Exposure in Ancient China». Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies. 14 (1/2): 130–184. doi:10.2307/2718298. ISSN 0073-0548. JSTOR 2718298.

- ^ «The Relationship Between Dance And Music || Dotted Music». Retrieved 2021-10-27.

- ^ a b Shawn, Ted, Dance We Must, 1946, Dennis Dobson Ltd., London, p. 50

- ^ Imperial Society of Teachers of Dancing, Ballroom Dancing, Teach Yourself Books, Hodder and Stoughton, 1977, p. 38

- ^ a b c Lincoln Kirstein, Dance, Dance Horizons Incorporated, New York, 1969, p. 4

- ^ Shawn, Ted, Dance We Must, 1946, Dennis Dobson Ltd., London, p. 49

- ^ Lincoln Kirstein, Dance, Dance Horizons Incorporated, New York, 1969, p. 3

- ^ Matthew 11:17

- ^ Lincoln Kirstein, Dance, Dance Horizons Incorporated, New York, 1969, p. 108

- ^ Lincoln Kirstein, Dance, Dance Horizons Incorporated, New York, 1969, p. 157

- ^ Scholes, Percy A. (1977). «Dance». The Oxford Companion to Music (10 ed.). Oxford University Press.

- ^ Émile Jaques-Dalcroze, Rhythm, Music and Education, 1973, The Dalcroze Society, London, p. viii

- ^ Émile Jaques-Dalcroze, Rhythm, Music and Education, 1973, The Dalcroze Society, London, p. 181

- ^ Shawn, Ted, Dance We Must, 1946, Dennis Dobson Ltd., London, p. 54

- ^ Shawn, Ted, Dance We Must, 1946, Dennis Dobson Ltd., London, pp. 50–51

- ^ Moller, Helen and Dunham, Curtis, Dancing with Helen Moller, 1918, John Lane (New York and London), p. 74

- ^ Laban, Rudolf, The Mastery of Movement, MacDonald and Evans, London, 1960, p. 2

- ^ Minden, Eliza Gaynor, The Ballet Companion: A Dancer’s Guide, Simon and Schuster, 2007, p. 92

- ^ Thoinot Arbeau, Orchesography, trans. by Mary Stewart Evans, with notes by Julia Sutton, New York: Dover, 1967

- ^ Laban, Rudolf, The Mastery of Movement, MacDonald and Evans, London, 1960, pp. 2, 4 et passim

- ^ Laban, Rudolf, The Mastery of Movement, MacDonald and Evans, London, 1960, p. 86

- ^ Abigail Wagner, A Different Type of Rhythm, Lawrence University, Wisconsin

- ^ «Kabuki « MIT Global Shakespeares». Retrieved April 8, 2015.

- ^ Ortolani, Benito (1995). The Japanese theatre: from shamanistic ritual to contemporary pluralism. Princeton University Press. p. 132. ISBN 978-0-691-04333-3.

- ^ Ayansu, E.S. and Whitfield, P. (eds.), The Rhythms Of Life, Marshall Editions, 1982, p. 161

- ^ a b Kariamu Welsh; Elizabeth A. Hanley; Jacques D’Amboise (1 January 2010). African Dance. Infobase Publishing. ISBN 978-1-60413-477-3.

- ^ a b c Hanna, Judith Lynne (1973). «African Dance: the continuity of change». Yearbook of the International Folk Music Council. 5: 165–174. doi:10.2307/767501. JSTOR 767501.

- ^ Utley, Ian. (2009). Culture smart! Ghana customs & culture. Kuperard. OCLC 978296042.

- ^ Exoticindiaart.com, Dance: The Living Spirit of Indian Arts, by Prof. P.C. Jain and Dr. Daljeet.

- ^ Lankalibrary.com, «The yakun natima — devil dance ritual of Sri Lanka»

- ^ «The Indonesian Folk Dances». Indonesia Tourism. Archived from the original on 24 November 2010. Retrieved 30 November 2010.

- ^ a b Badley, Bill and Zein al Jundi. «Europe Meets Asia». 2000. In Broughton, Simon and Ellingham, Mark with McConnachie, James and Duane, Orla (Ed.), World Music, Vol. 1: Africa, Europe and the Middle East, pp. 391–395. Rough Guides Ltd, Penguin Books.

- ^ Recep Albayrak Hacaloğlu. Azeri Türkçesi dil kilavuzu. Hacaloğlu, 1992; p. 272.

- ^ Subhi Anwar Rashid, Mesopotamien, Abb 137

- ^ Carol Lee (2002). Ballet in Western Culture: A History of Its Origins and Evolution. pp. 10–11. ISBN 978-0-415-94257-7.

- ^ Kourlas, Gia (2016-09-02). «Hiplet: An Implausible Hybrid Plants Itself on Pointe». The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 2022-01-01. Retrieved 2016-12-03.

- ^ a b John Charles Chasteen (1 January 2004). National Rhythms, African Roots: The Deep History of Latin American Popular Dance. UNM Press. pp. 8–14. ISBN 978-0-8263-2941-7.

- ^ Margaret Musmon; Elizabeth A. Hanley; Jacques D’Amboise (2010). Latin and Caribbean Dance. Infobase Publishing. pp. 20–23. ISBN 978-1-60413-481-0.

- ^ a b Celeste Fraser Delgado; José Esteban Muñoz (1997). Everynight Life: Culture and Dance in Latin/o America. Duke University Press. pp. 9–41. ISBN 978-0-8223-1919-1.

- ^ «Dance/Movement Therapy’s Influence on Adolescents Mathematics, Social-Emotional and Dance Skills | ArtsEdSearch». www.artsedsearch.org. Retrieved 2020-03-18.

- ^ Sagolla, Lisa (April 24, 2008). «(untitled)». International Bibliography of Theatre & Dance. 15 (17): 1.

- ^ «Dance Teacher | Berklee». www.berklee.edu. Retrieved 2022-10-04.

- ^ Risner, Doug (December 2000). «Making Dance, Making Sense: Epistemology and choreography». Research in Dance Education. 1 (2): 155–172. doi:10.1080/713694259. ISSN 1464-7893. S2CID 143435623.

- ^ «dance — Choreography | Britannica». www.britannica.com. Retrieved 2022-10-04.

- ^ a b Schupp, Karen (2019-04-03). «Dance Competition Culture and Commercial Dance: Intertwined Aesthetics, Values, and Practices». Journal of Dance Education. 19 (2): 58–67. doi:10.1080/15290824.2018.1437622. ISSN 1529-0824. S2CID 150019666.

- ^ Wilcox, Emily (22 December 2017). «Performing Bandung: China’s dance diplomacy with India, Indonesia, and Burma, 1953–1962». Inter-Asia Cultural Studies. 18 (4): 518–539. doi:10.1080/14649373.2017.1391455. Retrieved 21 March 2023.

- ^ Russell, Jeffrey A. (2013-09-30). «Preventing dance injuries: current perspectives». Open Access Journal of Sports Medicine. 4: 199–210. doi:10.2147/OAJSM.S36529. ISSN 1179-1543. PMC 3871955. PMID 24379726.

- ^ Li, Fengfeng; Adrien, Ntwali; He, Yuhuan (2022-04-18). «Biomechanical Risks Associated with Foot and Ankle Injuries in Ballet Dancers: A Systematic Review». International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 19 (8): 4916. doi:10.3390/ijerph19084916. ISSN 1660-4601. PMC 9029463. PMID 35457783.

- ^ Center, Smithsonian Lemelson (2020-05-28). «A Better Pointe Shoe Is Sorely Needed». Lemelson Center for the Study of Invention and Innovation. Retrieved 2022-12-13.

- ^ Abraham, Suzanne (1996). «Eating and Weight Controlling Behaviours of Young Ballet Dancers». Psychopathology. 29 (4): 218–222. doi:10.1159/000284996. ISSN 1423-033X. PMID 8865352.

- ^ Walton, Courtney C.; Osborne, Margaret S.; Gilbert, Paul; Kirby, James (2022-03-04). «Nurturing self-compassionate performers». Australian Psychologist. 57 (2): 77–85. doi:10.1080/00050067.2022.2033952. ISSN 0005-0067. S2CID 247163600.

- ^ Arcelus, Jon; Witcomb, Gemma L.; Mitchell, Alex (2013-11-26). «Prevalence of Eating Disorders amongst Dancers: A Systemic Review and Meta-Analysis». European Eating Disorders Review. 22 (2): 92–101. doi:10.1002/erv.2271. ISSN 1072-4133. PMID 24277724.

- ^ TikTok cultures in the United States. Trevor Boffone. Abingdon, Oxon. 2022. ISBN 978-1-000-60215-9. OCLC 1295618580.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Warburton, Edward C. (2022-07-01). «TikTok challenge: dance education futures in the creator economy». Arts Education Policy Review: 1–11. doi:10.1080/10632913.2022.2095068. ISSN 1063-2913. S2CID 250233625.

Further reading[edit]

- Abra, Allison. «Going to the palais: a social and cultural history of dancing and dance halls in Britain, 1918–1960.» Contemporary British History (Sep 2016) 30#3 pp. 432–433.

- Blogg, Martin. Dance and the Christian Faith: A Form of Knowing, The Lutterworth Press (2011), ISBN 978-0-7188-9249-4

- Carter, A. (1998) The Routledge Dance Studies Reader. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-16447-8.

- Cohen, S, J. (1992) Dance As a Theatre Art: Source Readings in Dance History from 1581 to the Present. Princeton Book Co. ISBN 0-87127-173-7.

- Daly, A. (2002) Critical Gestures: Writings on Dance and Culture. Wesleyan University Press. ISBN 0-8195-6566-0.

- Miller, James, L. (1986) Measures of Wisdom: The Cosmic Dance in Classical and Christian Antiquity, University of Toronto Press. ISBN 0-8020-2553-6.

External links[edit]

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). «Dance» . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- Historic illustrations of dancing from 3300 BC to 1911 AD from Project Gutenberg

- United States National Museum of Dance and Hall of Fame

This is a big article about dance, because dance is a big subject.

This free dancing guide offers many helpful explanations, descriptions, and lots of other positive words, for creating notes and other content for effective, inspirational understanding, teaching and promotion of dancing.

Dancing is on this website because..

Dancing maintains and improves our quality of life more than any other human activity:

If you can think of any physical activity that offers as many benefits for human existence as dancing, then

please tell me

.

Dancing and learning to dance, and inspiring and teaching others to dance, also connect strongly with the many life/work/organizational development concepts on this website, for example:

This article explains dance and dancing from many important exciting perspectives:

This dance article explains the following main subjects, and this list is also a

summary of the many major benefits and opportunities that dance and dancing offer:

- Dance — a subject to study — history, theory, qualifications, cultural significance.

- Dancing as a life-changing subject to teach others.

- Dance and dancing terminology — definitions, glossary, technical descriptions.

- Dancing as an art form, performance, entertainment.

-

Dance music — especially dance music and musical rhythms and styles, as they define and determine different types of dances, and the culture and ‘feel’ and atmosphere that surrounds and ‘packages’ so many radically different dance genres and

styles. - Dancing — actually ‘how to dance’, and how to teach others to dance — different types of dances — principles, tips, methods.

- Dance choreography and dance notation — the different types of choreography, and how to choreograph.

- Dance as a creative and innovative art form or entertainment — as simply dance, or within larger entertainments, shows, and to support and bring movement and dynamism to music.

- Dancing as a motivational and relationship-building activity for groups, and communities.

- Dancing as a way to improve personal wellbeing — for kids, adults, everyone — mind, body, soul, spirit.

- Dancing as an inclusive activity — becoming increasingly accessible regardless of disability

- Dance and its specific benefits for health, fitness, stress-reduction, and a long life.

- Dancing as a social activity — for friendships, romantics, and fun.

- Dance as a job, or career, or business.

- Dance as a competitive activity — to be recognised, awarded, to become a champion.

- And other things that relate to and support dance and dancers — for example: dancing costumes, dance shoes, dancing books, dance-floor/stage and performance materials, equipment, and venues, etc.

This article aims to be a leading free online introduction and guide to dance and dancing. If you want to suggest ways to improve it, then

please tell me

.

This article has been written with help from

City Academy

, the London-based creative and performing arts training

company, and the

Dance Generation dance school

, also of London, which is gratefully acknowledged. I am open

to further suggestions and contributions.

1. Main Index — Dance and Dancing

This index also appears after each main subject.

-

Main Index

-

Introduction to dance and dancing

-

About this article and how to use it

-

Origins of dance — dancing in human history

-

Definitions of dance — word origins, language

-

Benefits of dance — physical, mental, workplace, society

-

Who can dance?.. Everyone can dance..

-

How to learn to dance and how to teach dance

-

Glossary of dance styles and different forms of dancing — summary of the major dance types

-

Choreography — dance choreography and dance notation

-

Glossary of interesting and significant dance-related terms and people

-

Acknowledgements

-

Dance information sources — references, dance associations, teaching bodies, etc.

2. Introduction to Dance and Dancing.. from Africa to Salsa, from Waltz to Bhangra, and Bollywood to Zumba®..

(This guide is written also to offer material to teachers/trainers/writers, so you can cut and paste from this content for your own study or training materials, subject to the

terms of the Businessballs website

.

Hence there’s a lot of content here.)

Dancing is fundamental in life.

Since people have walked, people have danced.

Human beings are born to dance — we have dancing in our genes, which means you do too.

Dancing improves quality of our lives, and the health of societies.

Ancient civilisations knew about the amazing powers of dance and dancing, and increasingly the modern world is re-discovering how important dance is for living happily and healthily and long, and how dancing can transform people in so many ways

Besides being great fun, dance delivers benefits that will amaze you. This extends to people you might teach or train or entertain or manage — or the children and the young people that you parent or care for.

For many thousands of years, across all cultures, nations and peoples, dancing has been vital to human life.

Dancing is in our genes. The urge to dance — and to watch others dance — is deeply rooted in all of us.

Dance is immensely significant in our health, wellbeing and overall happiness.

Dancing enriches us, and enriches our communities.

Dancing is truly global and its benefits and joys are infinite.

Dance is far more beneficial and potent than we might imagine — as a way of living a happy good life, and helping others to be happy and healthy too.

While experienced passionate brilliant dancers and dance teachers recognise and understand the wonderful powers that dancing gives people — of all ages — many people have yet to realise what dancing can do and enable.

Dance promotes incredible benefits, and brings dramatic improvements, in motivation, and personal development too.

Dancing offers fabulous ways to motivate people towards brilliant achievements.

Dancing also diffuses stress, and fosters wellbeing — really like nothing else can — in individuals and groups, and bigger communities and societies.

Dancing is deeply embedded within us all.

If the origins of humankind first appeared in Africa, then dancing first happened in Africa too, and this was at least 150,000 years ago.

If instead the emergence of humankind is considered to be at least six million years ago, when humans separated from apes.. then we have been dancing for six million years.

For those who believe that humankind was created with the world itself, then this is 14 billion years ago, and we have been dancing for 14 billion years.

From most perspectives, Africa usually represents the oldest origins of dance — dancing for joy, for work, for play, for pleasure, for rain, for mating, for child-rearing, for ceremony and ritual, for a happy body — dancing for whatever was meaningful.

Dance is as old as people’s existence on Earth, and arguably before — like we see many animal species ‘dancing’ — bobbing, swaying, nodding, jumping, soaring, moving and shaping, in response to the rhythms of nature — the wind in the trees — the

ebb of the tide — the fall of the rain.

And in modern times — after millions of years of dancing — we are still dancing..

We are dancing our most basic human ways, and in our most innovative modern ways.

We are dancing traditional dances and modern dances and folk dances and street dances.

Our dancing is increasingly and excitingly fused into countless different dance styles, reflecting the fabulous rhythmic diversity and creativity of people and cultures on our planet.

Variations of dancing styles grow ever more astoundingly, particularly accelerated now by the globalized digitally and socially-connected video-sharing age.. and by young people more empowered, inspired, educated and confident than any previous

generation.

Dance styles are borrowed, blended, invented, and combined from every imaginable dance type — in amazing ways — From Jazz and Jive, Bollywood and Bhangra, Samba and Zumba®, Waltzing and Quickstepping, Disco and Dancehall, to Ballet and Tap, Flamenco

and Folk, Breakdance and Swing, Belly and Burlesque, Hip-hop and Street..

Wherever there is humanity, there will be dance and dancers dancing.

- Main Index

- Introduction to dance and dancing

- About this article and how to use it

- Origins of dance — dancing in human history

- Definitions of dance — word origins, language

- Benefits of dance — physical, mental, workplace, society

- Who can dance?.. Everyone can dance..

- How to learn to dance and how to teach dance

- Glossary of dance styles and different forms of dancing — summary of the major dance types

- Choreography — dance choreography and dance notation

- Glossary of interesting and significant dance-related terms and people

- Acknowledgements

- Dance information sources — references, dance associations, teaching bodies, etc.

3. About this dance article and how to use it

This is a big article about dance, so here’s an explanation of its aims and how to use it..

This article intends to cover every main aspect of the subject of dance and dancing.

Firstly — please understand that this article is

a basic easy introduction to dancing

and its history, theory, terminology, etc — this is not a highly technical or complex explanation of dancing and how to dance.

The article aims to be accessible and easy to understand, especially for young people.

It is written in a relaxed non-technical way, so that people who are not experts in dance — or dance language — can understand it quickly and enjoyably.

That said, while the article is not academically complex, it certainly aims to be

academically useful and reliable,

as a basic introduction and guide to the subject of dance, for example for people beginning to

study dance

,

or considering

careers in dancing

, or who might want to

start a dance business

of some sort.

This article also aims to be a useful and reliable reference resource for people

researching dance

— or different types of dances, or what dancing can do for people.

Another main aim of this article is to explain the considerable and varied

things that dancing can enable

, that are seemingly quite unrelated to dance, but which dancing can influence and improve enormously in one way or another.

For example, how dance can

improve people’s health and happiness

— in life, and at work too — and extending this point, how dance is a wonderful activity to use in work and group situations as a means of motivating people, of

building relationships, and for improving wellbeing and fitness and mental attitude.

This article also seeks to explain how

dancing can transform the lives and feelings of young people

.

This article also offers lots of

definitions and descriptions for dances and dancing

, and a

glossary of dancing terminology

— so that the reader gains a solid platform for understanding the subject of dance, on which

further studies, research, work, and skills can be planned and built.

This article aims to offer a

fabulous free introduction

to the subject of dance, enabling further development or use of dance for every imaginable direction and purpose.

The

main index above

will help you

see in detail what this article covers

.

4. Origins of dance — dancing in human history

Since humans first began living together in small tribes over 100,000 years ago, and probably millions of years before this, people have enjoyed dancing and used dance in a variety of ways.

Our ancient ancestors began to dance as part of play and social interaction, and then later in worshipping their gods, and also as an important rite of passage to various

life stages

.

Dance has for thousands of years been a part of growing up and entering new life stages — from children to teenagers, to adults, to parenthood, to being wise elders.

Since people have lived in groups, dance has been used in rituals and celebrations and festivals of all sorts:

- for growing and harvesting,

- eating and drinking,

- farming and livestock,

- fishing,

- relationships and bondings,

- births and sickness and death,

- plagues and pestilence,

- the weather — the sunshine, the rain, the snow, the drought, the flood, the wind and storms,

- the elements — the fire, water, earth, the air,

- the heat and the cold

- the sky and stars,

- nature — the trees and hills, rivers and seas, mountains and streams, birds and bees, every animal on the earth, every plant every herb every shrub

- human conflict and wars

- families and tribes and nations,

- cultures and creeds,

- religion and rule, revolution and independence…

- and thank goodness peace and cooperation and love and harmony too.

It is difficult to suggest a single aspect of human existence and experience that is not connected to dancing. Everything that exists is at some time or place touched, celebrated, asked for, feared and defended, or otherwise the subject of a dance.

These dances might be performed by a single person for a few seconds, or these dances might be performed by millions of people for thousands of years.

And these dances might be private, or unseen, or might be watched by millions, or billions. And everything in between these extremes.

Throughout the development of human history, dance has developed too, in parallel, reflecting humanity and civilisation, in terms of:

- culture,

- variety,

- styles,

- structure and established patterns,

- rules and laws

- and learning and teaching and transfer through writing and media.

The earliest dancing, like the earliest singing, music and cooking, was instinctive, intuitive, experimental, and taught personally by demonstration and observation, shown person to person, tribe to tribe, and passed down from generation to generation

— thousands or millions of years before books and writing. This type of dancing, after evolving to varying degrees, persists as folk dancing, as it is commonly technically called.

For tens of thousands of years, dance in this most basic form was accompanied by people’s voices, and the most rudimentary of musical and percussive instruments, Later, when humans had evolved more and could make better tools, about 100,000 years

ago, dance became more commonly accompanied by percussion — basically wooden things (hollow logs, blocks, etc) that people would strike with smaller wooden things (sticks essentially). Various shakers made from seeds and husks and shells,

or sand/seeds in shells etc., would also have been used in prehistoric times around the world.

Incidentally the drum (with skin membrane stretched over a wooden shell) was invented in Chinese Neolithic culture around 5500BC (over 7,500 years ago). Shakers in natural forms (certain dried seeds in husks/outer coverings) such as the rainstick,

and dried seaweeds, animal bones and teeth, or other naturally occurring shakable percussive objects, certainly existed before the membrane drum, and were used as part of ceremonial activities along with smoke and fire and water, etc., at

the most basic times of human (homo sapiens) evolution. We know this from ancient archeological evidence, and more particularly from studying ‘lost’ tribes (especially in recent South America), whose cultures have not been touched or altered

for many thousands of years.

And this happened for hundreds of thousands of years relatively unchanged, until humankind developed the capability to write and draw on paper — to record and transfer knowledge — and to make more sophisticated musical instruments and music.

And so around 500 years ago, like most other human activities, dance interpretation and performance (in celebrations and ceremonies, and socially and as audience entertainment) exploded into far greater complexity and variety — because people

were able to build new ideas on previous dance concepts/movements, and share expertise and creativity. As part of this growth and development, in both cause and result, dancing became more formalised and structured — with descriptions, and

types and styles, and standards and rules, and all sorts of variations that could be recorded, and shared and taught and learned by everyone.

This stage of dance development coincided with the beginnings of the modern age and globalization, which dramatically influenced the evolution of dance. Humankind began to travel and communicate like never before. Social and political structures

became more organized around the world, and ideas and customs were shared and spread and blended, which is reflected in the development of dancing.

The age of the European colonial powers (mainly 14th-19th centuries) increasingly exported European rule and people and ideas into Africa, Asia and the Americas, and also moved ideas and people from these regions back into Europe and elsewhere,

especially from Africa to the Americas, through the appalling slave trade, and use of slavery particularly in the Americas and Caribbean. North America especially became a vast laboratory for the importing and blending of dances.

All over the world, early tribal and folk dances were preserved and clung to by people who were oppressed, relocated or disenfranchised. This is particularly significant in South and North America, where slaves, stripped of everything, and randomly

mixed together from different tribal origins, having no common languages, used percussion and song and dance as a way to bond, relate, and maintain and reform communities and social groups. Slave owners typically banned drums and other attempts

to create music. Slaves were largely treated far worse than animals.

Think about it..

Through generations, millions of African people were forced to work and live in the most desperate living conditions imaginable, having

only their voices for singing, and their bodies for dancing, and it is from these roots that much ‘Western’ and ‘Latin’ dancing grew, becoming absorbed and adopted into new national cultures and identities as slavery declined and ceased, and

the new countries of the Americas were formed. And all the time, these developments were imported back to Europe, often adapted, and then spread further, including back to where they’d been first found.

This is a very broad overview of the Africa-Americas dance history that can be regarded as an example of a major aspect of dance history internationally. Similar evolution of dance, alongside massive social and demographic movements, has always

happened in other parts of the world. Dance is a mirror of civilizations and societies, whether in the Americas, or the Far East, or the Russian Empire, or the Arab world, or India or Australasia. Dance grows and spreads and blends with the

changing world, especially when people are forced to live in very basic ways.

Across the globe, dance has been a central feature of human behaviour and culture for all religions, creeds, societies and ethnic groups.