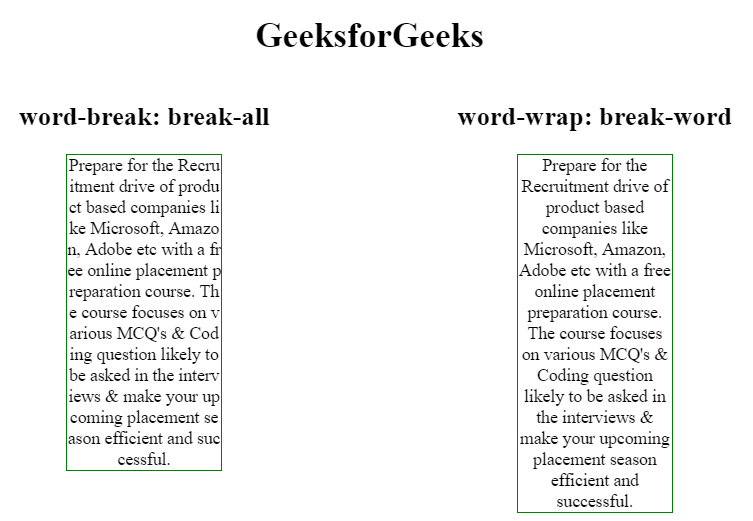

The definitions alone of word-break and word-wrap can easily make your head spin, but when comparing these two, specifically, it’s much easier to think of them like this:

First of all, you would probably like to use overflow: auto; as well, and you might want to try what using that alone looks like: if you can tolerate needing to scroll the text in the container rather than having arbitrary wrap positions, it might be just what you need.

Then keep in mind that in this context, a «word» is a string with no whitespaces in it.

word-break: break-all;

Prioritizes minimizing the space wasted while avoiding overflow, before keeping any words unbroken, so it never wraps anywhere but at the right margin. It even replaces line breaks with spaces in the contained text. This is useful if you want to avoid scrolling as much as possible and use a container that is enough wide for readability: however if your container is too narrow the result is in general not very satisfying, as Drkawashima noted.

word-wrap/overflow-wrap: break-word;

Prioritizes keeping any and all words unbroken while avoiding overflow, so if a word is too long to fit on the rest of the line, it wraps first and tries to fit the rest of the text on the next line even if it means leaving the line above as short as only one single character. This is useful if you want maximum readability while avoiding scrolling as much as possible and use a container that is enough wide: otherwise you might want to use only overflow: auto instead.

Regarding word-wrap, it isn’t really replaced (and maybe also more universally recognized than overflow-wrap by the browsers in use worldwide): it became an alias for overflow-wrap because all the big browsers and many many webpages had already adopted word-wrap although originally not being defined in the standards.

However, because of the widespread use, it wasn’t discarded when overflow-wrap was defined, but rather defined as the alias it is today, and for legacy reasons, UAs (User-Agents, e.g., web browsers) must treat word-wrap as a legacy name alias of the overflow-wrap property. So it has become a de facto standard of W3C and it isn’t going away any day soon (perhaps when the W3C standard becomes extinct or the entire web is universally updated by bots with AI).

5.5. Overflow Wrapping: the overflow-wrap/word-wrap property

overflow-wrap (MDN)

1. Introduction

This module describes the typesetting controls of CSS;

that is, the features of CSS that control the translation of

source text to formatted, line-wrapped text.

Various CSS properties provide control over case transformation, white space collapsing, text wrapping, line breaking rules and hyphenation, alignment and justification, spacing,

and indentation.

Further information about the typesetting requirements

of various languages and writing systems around the world

can be found in the Internationalization Working Group’s Language Enablement Index. [TYPOGRAPHY]

1.1. Module Interactions

This module, together with the CSS Text Decoration Module,

replaces and extends the text-level features defined in Cascading Style Sheets Level 2 chapter 16. [CSS-TEXT-DECOR-3] [CSS2]

In addition to the terms defined below,

other terminology and concepts used in this specification are defined

in Cascading Style Sheets Level 2 and the CSS Writing Modes Module. [CSS2] and [CSS-WRITING-MODES-4].

1.2. Value Definitions

This specification follows the CSS property definition conventions from [CSS2] using the value definition syntax from [CSS-VALUES-3].

Value types not defined in this specification are defined in CSS Values & Units [CSS-VALUES-3].

Combination with other CSS modules may expand the definitions of these value types.

In addition to the property-specific values listed in their definitions,

all properties defined in this specification

also accept the CSS-wide keywords as their property value.

For readability they have not been repeated explicitly.

1.3. Languages and Typesetting

Authors should accurately language-tag their content

for the best typographic behavior.

Many typographic effects vary by linguistic context.

Language and writing system conventions can affect

line breaking, hyphenation, justification, glyph selection,

and many other typographic effects. In CSS, language-specific typographic tailorings

are only applied when the content language is known (declared). Therefore,

higher quality typography requires authors to communicate to the UA

the correct linguistic context of the text in the document.

The content language of an element is the (human) language

the element is declared to be in, according to the rules of the document language.

Note that it is possible for the content language of an element

to be unknown—e.g. untagged content,

or content in a document language that does not have a language-tagging facility,

is considered to have an unknown content language.

Note: Authors can declare the content language using the global lang attribute in HTML

or the universal xml:lang attribute in XML.

See the rules for determining the content language of an HTML element in HTML,

and the rules for determining the content language of an XML element in XML 1.0. [HTML] [XML10]

The content language an element is declared to be in

also identifies the specific written form of that language used in that element,

known as the content writing system.

Depending on the document language’s facilities for identifying the content language,

this information can be explicit or implied.

See the normative Appendix F:

Identifying the Content Writing System.

Note: Some languages have more than one writing system tradition;

in other cases a language can be transliterated into a foreign writing system.

Authors should subtag such cases

so that the UA can adapt appropriately.

For example, Korean (ko) can be written in

Hangul (-Hang),

Hanja (-Hani),

or a combination (-Kore).

Historical documents written solely in Hanja

do not use word spaces and

are formatted more like modern Chinese than modern Korean.

In other words, for typographic purposes ko-Hani behaves more like zh-Hant than ko (ko-Kore).

As another example Japanese (ja) is typically written

in a combination (-Japn) of Hiragana (-Hira),

Katakana (-Kana), and Kanji (-Hani).

However, it can also be ”romanized” into Latin (-Latn)

for special purposes like language-learning textbooks,

in which case it should be formatted more like English than Japanese.

As a third example contemporary Mongolian is written in two scripts:

Cyrillic (-Cyrl, officially used in Mongolia)

and Mongolian (-Mong, more common in Inner Mongolia, part of China).

These have very different formatting requirements,

with Cyrillic behaving similar to Latin and Greek,

and Mongolian deriving from both Arabic and Chinese writing conventions.

1.4. Characters and Letters

The basic unit of typesetting is the character.

However, because writing systems are not always as simple as the basic English alphabet,

what a character actually is depends on the context in which the term is used.

For example, in Hangul (the Korean writing system),

each square representation of a syllable

(e.g. 한=Han)

can be considered a character.

However, the square symbol is really composed of multiple letters each representing a phoneme

(e.g. ㅎ=h, ㅏ=a, ㄴ=n)

and these also could each be considered a character.

A basic unit of computer text encoding, for any given encoding,

is also called a character,

and depending on the encoding,

a single encoding character might correspond

to the entire pre-composed syllabic character (e.g. 한),

to the individual phonemic character (e.g. ㅎ),

or to smaller units such as

a base letterform (e.g. ㅇ)

and any combining marks that vary it (e.g. extra strokes that represent aspiration).

In turn, a single encoding character can be represented in the data stream as one or more bytes;

and in programming environments one byte is sometimes also called a character.

Therefore the term character is fairly ambiguous where technical precision is required.

For text layout, we will refer to the typographic character unit as the basic unit of text.

Even within the realm of text layout,

the relevant character unit depends on the operation.

For example, line-breaking and letter-spacing will segment

a sequence of Thai characters that include U+0E33 ำ THAI CHARACTER SARA AM differently;

or the behavior of a conjunct consonant in a script such as Devanagari

may depend on the font in use.

So the typographic character represents a unit of the writing system—such as a Latin alphabetic letter (including its diacritics),

Hangul syllable,

Chinese ideographic character,

Myanmar syllable cluster—that is indivisible with respect to a particular typographic operation

(line-breaking, first-letter effects, tracking, justification, vertical arrangement, etc.).

Unicode Standard Annex #29: Text Segmentation defines a unit called the grapheme cluster which approximates the typographic character. [UAX29] A UA must use the extended grapheme cluster (not legacy grapheme cluster), as defined in UAX29,

as the basis for its typographic character unit.

However, the UA should tailor the definitions

as required by typographic tradition

since the default rules are not always appropriate or ideal—and is expected to tailor them differently

depending on the operation as needed.

Note: The rules for such tailorings are out of scope for CSS.

The following are some examples of typographic character unit tailorings

required by standard typesetting practice:

- In some scripts such as Myanmar or Devanagari,

the typographic character unit for both justification and line-breaking

is an entire syllable,

which can include more than one Unicode grapheme cluster. [UAX29] -

In other scripts such as Thai or Lao,

even though for line-breaking the typographic character matches Unicode’s default grapheme clusters,

for letter-spacing the relevant unit

is less than a Unicode grapheme cluster,

and may require decomposition or other substitutions

before spacing can be inserted. [UAX29]For instance,

to properly letter-space the Thai word คำ (U+0E04 + U+0E33),

the U+0E33 needs to be decomposed into U+0E4D + U+0E32,

and then the extra letter-space inserted before the U+0E32: คํ า.A slightly more complex example is น้ำ (U+0E19 + U+0E49 + U+0E33).

In this case, normal Thai shaping will first decompose the U+0E33 into U+0E4D + U+0E32

and then swap the U+0E4D with the U+0E49, giving U+0E19 + U+0E4D + U+0E49 + U+0E32.

As before the extra letter-space is then inserted before the U+0E32: นํ้ า. - Vertical typesetting can also require tailoring.

For example, when typesetting upright text,

Tibetan tsek and shad marks are kept with the preceding grapheme cluster,

rather than treated as an independent typographic character unit. [CSS-WRITING-MODES-4]

A typographic letter unit (or letter for the purpose of this specification)

is a typographic character unit belonging to one of the Letter or Number general categories.

See Appendix E:

Characters and Properties for how to determine the Unicode properties of a typographic character unit.

The rendering characteristics of a typographic character unit divided

by an element boundary is undefined.

Ideally each component should be rendered

according to the formatting requirements of its respective element’s properties

while maintaining correct shaping and positioning

of the typographic character unit as a whole.

However, depending on the nature of the formatting differences between its parts

and the capabilities of the font technology in use,

this is not always possible.

Therefore such a typographic character unit may be rendered as belonging to either side of the boundary,

or as some approximation of belonging to both.

Authors are forewarned that dividing grapheme clusters or ligatures

by element boundaries may give inconsistent or undesired results.

1.5. Text Processing

CSS is built on Unicode. [UNICODE] UAs that support Unicode must adhere to all normative requirements

of the Unicode Core Standard,

except where explicitly overridden by CSS.

UAs implemented on the basis of a non-Unicode text encoding model are still

expected to fulfill the same text handling requirements

by assuming an appropriate mapping and analogous behavior.

For the purpose of determining adjacency for text processing

(such as white space processing, text transformation, line-breaking, etc.),

and thus in general within this specification,

intervening inline box boundaries and out-of-flow elements

must be ignored.

With respect to text shaping, however, see § 7.3 Shaping Across Element Boundaries.

2. Transforming Text

2.1. Case Transforms: the text-transform property

| Name: | text-transform |

|---|---|

| Value: | none | [capitalize | uppercase | lowercase ] || full-width || full-size-kana |

| Initial: | none |

| Applies to: | text |

| Inherited: | yes |

| Percentages: | n/a |

| Computed value: | specified keyword |

| Canonical order: | n/a |

| Animation type: | discrete |

This property transforms text for styling purposes.

It has no effect on the underlying content,

and must not affect the content of a plain text copy & paste operation.

Authors must not rely on text-transform for semantic purposes;

rather the correct casing and semantics should be encoded

in the source document text and markup.

Values have the following meanings:

- none

- No effects.

- capitalize

- Puts the first typographic letter unit of each word, if lowercase, in titlecase;

other characters are unaffected. - uppercase

- Puts all letters in uppercase.

- lowercase

- Puts all letters in lowercase.

- full-width

- Puts all typographic character units in full-width form.

If a character does not have a corresponding full-width form,

it is left as is.

This value is typically used to typeset Latin letters and digits

as if they were ideographic characters. - full-size-kana

- Converts all small Kana characters to the equivalent full-size Kana.

This value is typically used for ruby annotation text,

where authors may want all small Kana to be drawn as large Kana

to compensate for legibility issues at the small font sizes typically used in ruby.

The following example converts the ASCII characters

used in abbreviations in Japanese text to their full-width variants

so that they lay out and line break like ideographs:

abbr:lang(ja) { text-transform: full-width; }

Note: The purpose of text-transform is

to allow for presentational casing transformations

without affecting the semantics of the document.

Note in particular that text-transform casing operations are lossy,

and can distort the meaning of a text.

While accessibility interfaces may wish to convey

the apparent casing of the rendered text to the user,

the transformed text cannot be relied on to accurately represent

the underlying meaning of the document.

In this example,

the first line of text is capitalized as a visual effect.

section > p:first-of-type::first-line {

text-transform: uppercase;

}

This effect cannot be written into the source document

because the position of the line break depends on layout.

But also, the capitalization is not reflecting a semantic distinction

and is not intended to affect the paragraph’s reading;

therefore it belongs in the presentation layer.

In this example,

the ruby annotations,

which are half the size of the main paragraph text,

are transformed to use regular-size kana

in place of small kana.

rt { font-size: 50%; text-transform: full-size-kana; }

:is(h1, h2, h3, h4) rt { text-transform: none; /* unset for large text*/ }

Note that while this makes such letters easier to see at small type sizes,

the transformation distorts the text:

the reader needs to mentally substitute small kana in the appropriate places—not unlike reading a Latin inscription

where all “U”s look like “V”s.

For example, if text-transform: full-size-kana were applied to the following source,

the annotation would read “じゆう” (jiyū), which means “liberty”,

instead of “じゅう” (jū), which means “ten”,

the correct reading and meaning for the annotated “十”.

<ruby>十<rt>じゅう</ruby>

2.1.1. Mapping Rules

For capitalize, what constitutes a “word“ is UA-dependent; [UAX29] is suggested (but not required)

for determining such word boundaries.

Out-of-flow elements and inline element boundaries

must not introduce a text-transform word boundary

and must be ignored when determining such word boundaries.

Note: Authors cannot depend on capitalize to follow

language-specific titlecasing conventions

(such as skipping articles in English).

The UA must use the full case mappings for Unicode characters,

including any conditional casing rules,

as defined in the Default Case Algorithms section of The Unicode Standard. [UNICODE] If (and only if) the content language of the element is,

according to the rules of the document language,

known,

then any appropriate language-specific rules must be applied as well.

These minimally include,

but are not limited to,

the language-specific rules in Unicode’s SpecialCasing.txt.

For example, in Turkish there are two “i”s,

one with a dot—“İ” and “i”—and one without—“I” and “ı”.

Thus the usual case mappings between “I” and “i”

are replaced with a different set of mappings

to their respective dotless/dotted counterparts,

which do not exist in English.

This mapping must only take effect

if the content language is Turkish

written in its modern Latin-based writing system (or another Turkic language that uses Turkish casing rules);

in other languages,

the usual mapping of “I” and “i” is required.

This rule is thus conditionally defined in Unicode’s SpecialCasing.txt file.

The definition of full-width and half-width forms

can be found in Unicode Standard Annex #11: East Asian Width. [UAX11] The mapping to full-width form is defined

by taking code points with the <wide> or the <narrow> tag

in their Decomposition_Mapping in Unicode Standard Annex #44: Unicode Character Database. [UAX44] For the <narrow> tag,

the mapping is from the code point to the decomposition

(minus <narrow> tag),

and for the <wide> tag,

the mapping is from the decomposition

(minus the <wide> tag)

back to the original code point.

The mappings for small Kana to full-size Kana are defined in Appendix G:

Small Kana Mappings.

2.1.2. Order of Operations

When multiple values are specified

and therefore multiple transformations need to be applied,

they are applied in the following order:

- capitalize, uppercase, and lowercase

- full-width

- full-size-kana

Text transformation happens after § 4.1.1 Phase I: Collapsing and Transformation but before § 4.1.2 Phase II: Trimming and Positioning.

This means that full-width only transforms

spaces (U+0020) to U+3000 IDEOGRAPHIC SPACE within preserved white space.

Note: As defined in Appendix A:

Text Processing Order of Operations,

transforming text affects line-breaking and other formatting operations.

3. White Space and Wrapping: the white-space property

| Name: | white-space |

|---|---|

| Value: | normal | pre | nowrap | pre-wrap | break-spaces | pre-line |

| Initial: | normal |

| Applies to: | text |

| Inherited: | yes |

| Percentages: | n/a |

| Computed value: | specified keyword |

| Canonical order: | n/a |

| Animation type: | discrete |

This property specifies two things:

- whether and how white space is collapsed

- whether lines may wrap at unforced soft wrap opportunities

Values have the following meanings,

which must be interpreted according to

the White Space Processing and Line Breaking rules:

- normal

- This value directs user agents to collapse sequences of white space into a single character

(or in some cases, no character).

Lines may wrap at allowed soft wrap opportunities,

as determined by the line-breaking rules in effect,

in order to minimize inline-axis overflow. - pre

- This value prevents user agents from collapsing sequences of white space. Segment breaks such as line feeds

are preserved as forced line breaks.

Lines only break at forced line breaks;

content that does not fit within the block container overflows it. - nowrap

- Like normal,

this value collapses white space;

but like pre, it does not allow wrapping. - pre-wrap

- Like pre,

this value preserves white space;

but like normal,

it allows wrapping. - break-spaces

-

The behavior is identical to that of pre-wrap,

except that:- Any sequence of preserved white space or other space separators always takes up space,

including at the end of the line. - A line breaking opportunity exists

after every preserved white space character

and after every other space separator (including between adjacent spaces).

Note: This value does not guarantee

that there will never be any overflow due to white space:

for example, if the line length is so short

that even a single white space character does not fit,

overflow is unavoidable. - Any sequence of preserved white space or other space separators always takes up space,

- pre-line

- Like normal,

this value collapses consecutive white space characters and allows wrapping,

but it preserves segment breaks in the source as forced line breaks.

White space that was not removed or collapsed due to white space processing

is called preserved white space.

Note: In some cases, preserved white space and other space separators can hang when at the end of the line;

this can affect whether they are measured for intrinsic sizing.

The following informative table summarizes the behavior

of various white-space values:

| New Lines | Spaces and Tabs | Text Wrapping | End-of-line spaces | End-of-line other space separators | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| normal | Collapse | Collapse | Wrap | Remove | Hang |

| pre | Preserve | Preserve | No wrap | Preserve | No wrap |

| nowrap | Collapse | Collapse | No wrap | Remove | Hang |

| pre-wrap | Preserve | Preserve | Wrap | Hang | Hang |

| break-spaces | Preserve | Preserve | Wrap | Wrap | Wrap |

| pre-line | Preserve | Collapse | Wrap | Remove | Hang |

See White Space Processing Rules for details on how white space collapses.

See Line Breaking for details on wrapping behavior.

4. White Space Processing & Control Characters

The source text of a document often contains formatting

that is not relevant to the final rendering:

for example, breaking the source into segments (lines) for ease of editing

or adding white space characters such as tabs and spaces to indent the source code.

CSS white space processing allows the author

to control interpretation of such formatting:

to preserve or collapse it away when rendering the document.

White space processing in CSS

(which is controlled with the white-space property)

interprets white space characters only for rendering:

it has no effect on the underlying document data.

Note: Depending on the document language,

segments can be separated by a particular newline sequence

(such as a line feed or CRLF pair),

or delimited by some other mechanism,

such as the SGML RECORD-START and RECORD-END tokens.

For CSS processing,

each document language–defined “segment break” or “newline sequence”—or if none are defined, each line feed (U+000A)—in the text is treated as a segment break,

which is then interpreted for rendering as specified by the white-space property.

In the case of HTML,

each newline sequence is normalized to a single line feed (U+000A)

for representation in the DOM,

so when an HTML document is represented as a DOM tree

each line feed (U+000A)

is treated as a segment break. [HTML] [DOM]

Note: In most common CSS implementations,

HTML does not get styled directly.

Instead, it is processed into a DOM tree,

which is then styled.

Unlike HTML,

the DOM does not give any particular meaning to carriage returns (U+000D),

so they are not treated as segment breaks.

If carriage returns (U+000D) are inserted into the DOM

by means other than HTML parsing,

they then get treated as defined below.

Note: A document parser might

not only normalize any segment breaks,

but also collapse other space characters or

otherwise process white space according to markup rules.

Because CSS processing occurs after the parsing stage,

it is not possible to restore these characters for styling.

Therefore, some of the behavior specified below

can be affected by these limitations and

may be user agent dependent.

Note: Anonymous blocks consisting entirely of collapsible white space are removed from the rendering tree.

Thus any such white space surrounding a block-level element is collapsed away.

See Cascading Style Sheets Level 2 Revision 1 (CSS 2.1) Specification § visuren#anonymous. [CSS2]

Control characters (Unicode category Cc)—other than tabs (U+0009),

line feeds (U+000A),

carriage returns (U+000D)

and sequences that form a segment break—must be rendered as a visible glyph

which the UA must synthesize if the glyphs found in the font are not visible,

and must be otherwise treated as any other character

of the Other Symbols (So) general category and Common script.

The UA may use a glyph provided by a font specifically for the control character,

substitute the glyphs provided for the corresponding symbol in the Control Pictures block,

generate a visual representation of its code point value,

or use some other method to provide an appropriate visible glyph.

As required by Unicode,

unsupported Default_ignorable characters

must be ignored for text rendering. [UNICODE]

Carriage returns (U+000D) are treated identically to spaces (U+0020) in all respects.

Note: For HTML documents,

carriage returns present in the source code

are converted to line feeds at the parsing stage

(see HTML § 13.2.3.5 Preprocessing the input stream and the definition of normalize newlines in Infra and therefore do no appear as U+000D CARRIAGE RETURN to CSS. [HTML] [INFRA])

However, the character is preserved—and the above rule observable—when encoded using an escape sequence (

).

4.1. The White Space Processing Rules

Except where specified otherwise,

white space processing in CSS affects only

the document white space characters: spaces (U+0020), tabs (U+0009), and segment breaks.

Note: The set of characters considered document white space (part of the document content)

and those considered syntactic white space

(part of the CSS syntax)

are not necessarily identical.

However, since both include spaces (U+0020), tabs (U+0009), and line feeds (U+000A)

most authors won’t notice any differences.

Besides space (U+0020)

and no-break space (U+00A0),

Unicode defines a number of additional space separator characters. [UNICODE] In this specification

all characters in the Unicode general category Zs

except space (U+0020)

and no-break space (U+00A0)

are collectively referred to as other space separators.

4.1.1. Phase I: Collapsing and Transformation

For each inline

(including anonymous inlines;

see Cascading Style Sheets Level 2 Revision 1 (CSS 2.1) Specification § visuren#anonymous [CSS2])

within an inline formatting context, white space characters are processed as follows

prior to line breaking and bidi reordering,

ignoring bidi formatting characters (characters with the Bidi_Control property [UAX9])

as if they were not there:

-

If white-space is set to normal, nowrap, or pre-line, white space characters are considered collapsible and are processed by performing the following steps:

- Any sequence of collapsible spaces and tabs immediately preceding or following a segment break is removed.

- Collapsible segment breaks are transformed for rendering

according to the segment break transformation rules. - Every collapsible tab is converted to a collapsible space (U+0020).

- Any collapsible space immediately following another collapsible space—even one outside the boundary of the inline containing that space,

provided both spaces are within the same inline formatting context—is collapsed to have zero advance width.

(It is invisible,

but retains its soft wrap opportunity,

if any.)

- If white-space is set to pre, pre-wrap, or break-spaces,

any sequence of spaces is treated as a sequence of non-breaking spaces.

However, for pre-wrap,

a soft wrap opportunity exists at the end of a sequence of spaces and/or tabs,

while for break-spaces,

a soft wrap opportunity exists after every space and every tab.

The following example illustrates

the interaction of white-space collapsing and bidirectionality.

Consider the following markup fragment, taking special note of spaces (with varied backgrounds and borders for emphasis and identification):

<ltr>A <rtl> B </rtl> C</ltr>where the <ltr> element represents a left-to-right embedding

and the <rtl> element represents a right-to-left embedding.

If the white-space property is set to normal,

the white-space processing model will result in the following:

- The space before the B ( )

will collapse with the space after the A ( ). - The space before the C ( )

will collapse with the space after the B ( ).

This will leave two spaces,

one after the A in the left-to-right embedding level,

and one after the B in the right-to-left embedding level.

The text will then be ordered according to the Unicode bidirectional algorithm,

with the end result being:

A BC

Note that there will be two spaces between A and B,

and none between B and C.

This is best avoided by putting spaces outside the element

instead of just inside the opening and closing tags

and, where practical,

by relying on implicit bidirectionality instead of explicit embedding levels.

4.1.2. Phase II: Trimming and Positioning

Then, the entire block is rendered.

Inlines are laid out,

taking bidi reordering into account,

and wrapping as specified by the white-space property.

As each line is laid out,

- A sequence of collapsible spaces at the beginning of a line

is removed. -

If the tab size is zero, preserved tabs are not rendered.

Otherwise, each preserved tab is rendered

as a horizontal shift that lines up

the start edge of the next glyph with the next tab stop.

If this distance is less than 0.5ch,

then the subsequent tab stop is used instead. Tab stops occur at points

that are multiples of the tab size from the starting content edge

of the preserved tab’s nearest block container ancestor.

The tab size is given by the tab-size property.Note: See the Unicode rules on how tabulation (U+0009) interacts with bidi. [UAX9]

-

A sequence of collapsible spaces at the end of a line is removed,

as well as any trailing U+1680 OGHAM SPACE MARK

whose white-space property is normal, nowrap, or pre-line.Note: Due to Unicode Bidirectional Algorithm rule L1,

a sequence of collapsible spaces located at the end of the line

prior to bidi reordering will also be at the end of the line after reordering. [UAX9] [CSS-WRITING-MODES-4] -

If there remains any sequence of white space, other space separators,

and/or preserved tabs at the end of a line

(after bidi reordering [CSS-WRITING-MODES-4]):- If white-space is set to normal, nowrap,

or pre-line,

the UA must hang this sequence (unconditionally). -

If white-space is set to pre-wrap,

the UA must (unconditionally) hang this sequence,

unless the sequence is followed by a forced line break,

in which case it must conditionally hang the sequence instead.

It may also visually collapse the character advance widths

of any that would otherwise overflow.Note: Hanging the white space rather than collapsing it

allows users to see the space when selecting or editing text. -

If white-space is set to break-spaces, spaces, tabs, and other space separators are treated the same as other visible characters:

they cannot hang nor have their advance width collapsed.Note: Such characters therefore take up space,

and depending on the available space

and applicable line breaking controls

will either overflow or cause the line to wrap.

- If white-space is set to normal, nowrap,

This example shows that conditionally hanging white space

at the end of lines with forced breaks

provides symmetry with the start of the line.

An underline is added to help visualize the spaces.

p {

white-space: pre-wrap;

width: 5ch;

border: solid 1px;

font-family: monospace;

text-align: center;

}

<p> 0 </p>

The sample above would be rendered as follows:

0

Since the final space is before a forced line break

and does not overflow,

it does not hang,

and centering works as expected.

This example illustrates the difference

between hanging spaces at the end of lines without forced breaks,

and conditionally hanging them at the end of lines with forced breaks.

An underline is added to help visualize the spaces.

p {

white-space: pre-wrap;

width: 3ch;

border: solid 1px;

font-family: monospace;

}

<p> 0 0 0 0 </p>

The sample above would be rendered as follows:

0

0 0

0

If p { text-align: right; } was added,

the result would be as follows:

0

0 0

0

As the preserved spaces at the end of lines without a forced break must hang,

they are not considered when placing the rest of the line during text alignment.

When aligning towards the end,

this means any such spaces will overflow,

and will not prevent the rest of the line’s content from being flush with the edge of the line.

On the other hand,

preserved spaces at the end of a line with a forced break conditionally hang.

Since the space at the end of the last line would not overflow in this example,

it does not hang and therefore is considered during text alignment.

In the following example,

there is not enough room on any line to fit the end-of-line spaces,

so they hang on all lines:

the one on the line without a forced break because it must,

as well as the one on the line with a forced break,

because it conditionally hangs and overflows.

An underline is added to help visualize the spaces.

p {

white-space: pre-wrap;

width: 3ch;

border: solid 1px;

font-family: monospace;

}

<p>0 0 0 0 </p>

0 0

0 0

The last line is not wrapped before the last 0 because characters that conditionally hang are not considered

when measuring the line’s contents for fit.

4.1.3. Segment Break Transformation Rules

When white-space is pre, pre-wrap, break-spaces, or pre-line, segment breaks are not collapsible and are instead transformed into a preserved line feed (U+000A).

For other values of white-space, segment breaks are collapsible,

and are collapsed as follows:

- First, any collapsible segment break immediately following another collapsible segment break is removed.

-

Then any remaining segment break is either transformed into a space (U+0020)

or removed

depending on the context before and after the break.

The rules for this operation are UA-defined in this level.Note: The white space processing rules have already

removed any tabs and spaces around the segment break before this context is evaluated.

The purpose of the segment break transformation rules

(and white space collapsing in general)

is to “unbreak” text that has been broken into segments to make the document source code easier to work with.

In languages that use word separators, such as English and Korean,

“unbreaking” a line requires joining the two lines with a space.

Here is an English paragraph that is broken into multiple lines in the source code so that it can be more easily read and edited in a text editor.

Here is an English paragraph that is broken into multiple lines in the source code so that it can be more easily read and edited in a text editor.

requires maintaining a space in its place.

In languages that have no word separators, such as Chinese,

“unbreaking” a line requires joining the two lines with no intervening space.

這個段落是那麼長, 在一行寫不行。最好 用三行寫。

這個段落是那麼長,在一行寫不行。最好用三行寫。

requires eliminating any intervening white space.

The segment break transformation rules can use adjacent context

to either transform the segment break into a space

or eliminate it entirely.

Note: Historically, HTML and CSS have unconditionally converted segment breaks to spaces,

which has prevented content authored in languages such as Chinese

from being able to break lines within the source.

Thus UA heuristics need to be conservative about where they discard segment breaks even as they strive to improve support for such languages.

4.2. Tab Character Size: the tab-size property

| Name: | tab-size |

|---|---|

| Value: | <number> | <length> |

| Initial: | 8 |

| Applies to: | text |

| Inherited: | yes |

| Percentages: | n/a |

| Computed value: | the specified number or absolute length |

| Canonical order: | n/a |

| Animation type: | by computed value type |

This property determines the tab size used to render preserved tab characters (U+0009).

A <number> represents the measure

as a multiple of the advance width of the space character (U+0020)

of the nearest block container ancestor of the preserved tab,

including its associated letter-spacing and word-spacing.

Negative values are not allowed.

5. Line Breaking and Word Boundaries

When inline-level content is laid out into lines, it is broken across line boxes.

Such a break is called a line break.

When a line is broken due to explicit line-breaking controls

(such as a preserved newline character),

or due to the start or end of a block,

it is a forced line break.

When a line is broken due to content wrapping (i.e. when the UA creates unforced line breaks

in order to fit the content within the measure),

it is a soft wrap break.

The process of breaking inline-level content into lines is called line breaking.

Wrapping is only performed at an allowed break point,

called a soft wrap opportunity.

When wrapping is enabled (see white-space),

the UA must minimize the amount of content overflowing a line

by wrapping the line at a soft wrap opportunity,

if one exists.

In most writing systems,

in the absence of hyphenation a soft wrap opportunity occurs only at word boundaries.

Many such systems use spaces or punctuation to explicitly separate words,

and soft wrap opportunities can be identified by these characters.

Scripts such as Thai, Lao, and Khmer, however,

do not use spaces or punctuation to separate words.

Although the zero width space (U+200B) can be used as an explicit word delimiter

in these scripts,

this practice is not common.

As a result, a lexical resource is needed

to correctly identify soft wrap opportunities in such texts.

In some other writing systems, soft wrap opportunities are based on orthographic syllable boundaries,

not word boundaries.

Some of these systems, such as Javanese and Balinese,

are similar to Thai and Lao in that they

require analysis of the text to find breaking opportunities.

In others such as Chinese (as well as Japanese, Yi, and sometimes also Korean),

each syllable tends to correspond to a single typographic letter unit,

and thus line breaking conventions allow the line to break

anywhere except between certain character combinations.

Additionally the level of strictness in these restrictions

varies with the typesetting style.

While CSS does not fully define where soft wrap opportunities occur,

some controls are provided to distinguish common variations:

- The line-break property allows choosing various levels of “strictness”

for line breaking restrictions. - The word-break property controls what types of letters

are glommed together to form unbreakable “words”,

causing CJK characters to behave like non-CJK text or vice versa. - The hyphens property controls whether automatic hyphenation

is allowed to break words in scripts that hyphenate. - The overflow-wrap property allows the UA to take a break anywhere

in otherwise-unbreakable strings that would otherwise overflow.

Note: Unicode Standard Annex #14: Unicode Line Breaking Algorithm defines a baseline behavior

for line breaking for all scripts in Unicode,

which is expected to be further tailored. [UAX14] More information on line breaking conventions

can be found in Requirements for Japanese Text Layout [JLREQ] and Formatting Rules for Japanese Documents [JIS4051] for Japanese, Requirements for Chinese Text Layout [CLREQ] and General Rules for Punctuation [ZHMARK] for Chinese.

See also the Internationalization Working Group’s Language Enablement Index which includes more information on additional languages. [TYPOGRAPHY] Any guidance on additional appropriate references

would be much appreciated.

5.1. Line Breaking Details

When determining line breaks:

- The interaction of line breaking and bidirectional text is defined by CSS Writing Modes 4 § 2.4 Applying the Bidirectional Reordering Algorithm and the Unicode Bidirectional Algorithm (UAX9§3.4 Reordering Resolved Levels in particular). [CSS-WRITING-MODES-4] [UAX9]

-

Preserved segment breaks, and—regardless of the white-space value—any Unicode character with the the

BKandNLline breaking class,

must be treated as forced line breaks. [UAX14]Note: The bidi implications of such forced line breaks are defined by the Unicode Bidirectional Algorithm. [UAX9]

- Except where explicitly defined otherwise

(e.g. for line-break: anywhere or overflow-wrap: anywhere)

line breaking behavior defined for

theWJ,ZW,GL,

andZWJUnicode line breaking classes

must be honored. [UAX14] - UAs that allow wrapping at punctuation

other than word separators in writing systems that use them should prioritize breakpoints.

(For example, if breaks after slashes are given a lower priority than spaces,

the sequence “check /etc” will never break between the «/» and the «e».)

As long as care is taken to avoid such awkward breaks,

allowing breaks at appropriate punctuation other than word separators is recommended,

as it results in more even-looking margins, particularly in narrow measures.

The UA may use the width of the containing block, the text’s language,

the line-break value,

and other factors in assigning priorities:

CSS does not define prioritization of line breaking opportunities.

Prioritization of word separators is not expected,

however,

if word-break: break-all is specified

(since this value explicitly requests line breaking behavior

not based on breaking at word separators)—and is forbidden under line-break: anywhere. - Out-of-flow elements

and inline element boundaries

do not introduce a forced line break or soft wrap opportunity in the flow. - For Web-compatibility

there is a soft wrap opportunity before and after each replaced element or other atomic inline,

even when adjacent to a character that would normally suppress them,

such as U+00A0 NO-BREAK SPACE. - For soft wrap opportunities created by characters

that disappear at the line break (e.g. U+0020 SPACE),

properties on the box directly containing that character

control the line breaking at that opportunity.

For soft wrap opportunities defined by the boundary between two characters,

the white-space property

on the nearest common ancestor of the two characters

controls breaking;

which elements’ line-break, word-break, and overflow-wrap properties

control the determination of soft wrap opportunities at such boundaries

is undefined in Level 3. - For soft wrap opportunities before the first

or after the last character of a box,

the break occurs immediately before/after the box

(at its margin edge)

rather than breaking the box

between its content edge and the content. - Line breaking in/around Ruby is defined

in CSS Ruby Annotation Layout 1 § 3.4 Breaking Across Lines. [CSS-RUBY-1] -

In order to avoid unexpected overflow,

if the user agent is unable to perform the requisite lexical

or orthographic analysis

for line breaking any content language that requires it—for example due to lacking a dictionary for certain languages—it must assume a soft wrap opportunity between pairs of typographic letter units in that writing system.Note: This provision is not triggered merely when

the UA fails to find a word boundary in a particular text run;

the text run may well be a single unbreakable word.

It applies for example

when a text run is composed of Khmer characters (U+1780 to U+17FF)

if the user agent does not know how to determine

word boundaries in Khmer.

5.2. Breaking Rules for Letters: the word-break property

| Name: | word-break |

|---|---|

| Value: | normal | keep-all | break-all | break-word |

| Initial: | normal |

| Applies to: | text |

| Inherited: | yes |

| Percentages: | n/a |

| Computed value: | specified keyword |

| Canonical order: | n/a |

| Animation type: | discrete |

This property specifies soft wrap opportunities between letters,

i.e. where it is “normal” and permissible to break lines of text.

Specifically it controls whether a soft wrap opportunity generally exists

between adjacent typographic letter units,

treating non-letter typographic character units belonging to the NU, AL, AI,

or ID Unicode line breaking classes

as typographic letter units for this purpose (only). [UAX14] It does not affect rules governing the soft wrap opportunities created by white space (as well as by other space separators)

and around punctuation.

(See line-break for controls affecting punctuation and small kana.)

For example,

in some styles of CJK typesetting,

English words are allowed to break between any two letters,

rather than only at spaces or hyphenation points;

this can be enabled with word-break:break-all.

being broken at an arbitrary point in the word.

As another example, Korean has two styles of line-breaking:

between any two Korean syllables (word-break: normal)

or, like English, mainly at spaces (word-break: keep-all).

각 줄의 마지막에 한글이 올 때 줄 나눔 기 준을 “글자” 또는 “어절” 단위로 한다.

각 줄의 마지막에 한글이 올 때 줄 나눔 기준을 “글자” 또는 “어절” 단위로 한다.

Ethiopic similarly has two styles of line-breaking,

either only breaking at word separators (word-break: normal),

or also allowing breaks between letters within a word (word-break: break-all).

ተወልዱ፡ኵሉ፡ሰብእ፡ግዑዛን፡ወዕሩያን፡ በማዕረግ፡ወብሕግ።ቦሙ፡ኅሊና፡ወዐቅል፡ ወይትጌበሩ፡አሐዱ፡ምስለ፡አሀዱ፡ በመንፈሰ፡እኍና።

ተወልዱ፡ኵሉ፡ሰብእ፡ግዑዛን፡ወዕሩያን፡በማ ዕረግ፡ወብሕግ።ቦሙ፡ኅሊና፡ወዐቅል፡ወይትጌ በሩ፡አሐዱ፡ምስለ፡አሀዱ፡በመንፈሰ፡እኍና።

Note: To enable additional break opportunities only in the case of overflow,

see overflow-wrap.

Values have the following meanings:

- normal

- Words break according to their customary rules,

as described above.

Korean, which commonly exhibits two different behaviors,

allows breaks between any two consecutive Hangul/Hanja.

For Ethiopic, which also exhibits two different behaviors,

such breaks within words are not allowed. - break-all

-

Breaking is allowed within “words”:

specifically,

in addition to soft wrap opportunities allowed for normal,

any typographic letter units (and any typographic character units resolving to theNU(“numeric”),AL(“alphabetic”),

orSA(“Southeast Asian”)

line breaking classes [UAX14])

are instead treated asID(“ideographic characters”)

for the purpose of line-breaking.

Hyphenation is not applied.Note: This value does not affect

whether there are soft wrap opportunities around punctuation characters.

To allow breaks anywhere, see line-break: anywhere.Note: This option enables the other common behavior for Ethiopic.

It is also often used in a context where

the text consists predominantly of CJK characters

with only short non-CJK excerpts,

and it is desired that the text be better distributed on each line. - keep-all

-

Breaking is forbidden within “words”:

implicit soft wrap opportunities between typographic letter units (or other typographic character units belonging to theNU,AL,AI,

orIDUnicode line breaking classes [UAX14])

are suppressed,

i.e. breaks are prohibited between pairs of such characters

(regardless of line-break settings other than anywhere)

except where opportunities exist due to dictionary-based breaking.

Otherwise this option is equivalent to normal.

In this style, sequences of CJK characters do not break.Note: This is the other common behavior for Korean

(which uses spaces between words),

and is also useful for mixed-script text where CJK snippets are mixed

into another language that uses spaces for separation.

Symbols that line-break the same way as letters of a particular category

are affected the same way as those letters.

Here’s a mixed-script sample text:

这是一些汉字 and some Latin و کمی خط عربی และตัวอย่างการเขียนภาษาไทย በጽሑፍ፡ማራዘሙን፡አንዳንድ፡

The break-points are determined as follows (indicated by ‘·’):

- word-break: normal

-

这·是·一·些·汉·字·and·some·Latin·و·کمی·خط·عربی·และ·ตัวอย่าง·การเขียน·ภาษาไทย·በጽሑፍ፡·ማራዘሙን፡·አንዳንድ፡

- word-break: break-all

-

这·是·一·些·汉·字·a·n·d·s·o·m·e·L·a·t·i·n·و·ﮐ·ﻤ·ﻰ·ﺧ·ﻁ·ﻋ·ﺮ·ﺑ·ﻰ·แ·ล·ะ·ตั·ว·อ·ย่·า·ง·ก·า·ร·เ·ขี·ย·น·ภ·า·ษ·า·ไ·ท·ย·በ·ጽ·ሑ·ፍ፡·ማ·ራ·ዘ·ሙ·ን፡·አ·ን·ዳ·ን·ድ፡

- word-break: keep-all

-

这是一些汉字·and·some·Latin·و·کمی·خط·عربی·และ·ตัวอย่าง·การเขียน·ภาษาไทย·በጽሑፍ፡·ማራዘሙን፡·አንዳንድ፡

Japanese is usually typeset allowing line breaks within words.

However, it is sometimes preferred to suppress these wrapping opportunities

and to only allow wrapping at the end of certain sentence fragments.

This is most commonly done in very short pieces of text,

such as headings and table or figure captions.

This can be achieved by marking the allowed wrapping points

with wbr or U+200B ZERO WIDTH SPACE,

and suppressing the other ones using word-break: keep-all.

For instance, the following markup can produce either of the renderings below,

depending on the value of the word-break property:

<h1>窓ぎわの<wbr>トットちゃん</h1>

h1 { word-break: normal }

|

h1 { word-break: keep-all }

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Expected rendering |

窓ぎわのトットちゃ ん |

窓ぎわの トットちゃん |

| Result in your browser | 窓ぎわのトットちゃん | 窓ぎわのトットちゃん |

When shaping scripts such as Arabic

are allowed to break within words due to break-all the characters must still be shaped

as if the word were not broken (see § 5.6 Shaping Across Intra-word Breaks).

For compatibility with legacy content,

the word-break property also supports

a deprecated break-word keyword.

When specified, this has the same effect as word-break: normal and overflow-wrap: anywhere,

regardless of the actual value of the overflow-wrap property.

5.3. Line Breaking Strictness: the line-break property

| Name: | line-break |

|---|---|

| Value: | auto | loose | normal | strict | anywhere |

| Initial: | auto |

| Applies to: | text |

| Inherited: | yes |

| Percentages: | n/a |

| Computed value: | specified keyword |

| Canonical order: | n/a |

| Animation type: | discrete |

This property specifies the strictness of line-breaking rules applied

within an element:

especially how wrapping interacts with punctuation and symbols.

Values have the following meanings:

- auto

- The UA determines the set of line-breaking restrictions to use,

and it may vary the restrictions based on the length of the line;

e.g., use a less restrictive set of line-break rules for short lines. - loose

- Breaks text using the least restrictive set of line-breaking

rules. Typically used for short lines, such as in newspapers. - normal

- Breaks text using the most common set of line-breaking rules.

- strict

- Breaks text using the most stringent set of line-breaking rules.

- anywhere

-

There is a soft wrap opportunity around every typographic character unit,

including around any punctuation character

or preserved white spaces,

or in the middle of words,

disregarding any prohibition against line breaks,

even those introduced by characters with theGL,WJ, orZWJline breaking classes

or mandated by the word-break property. [UAX14] The different wrapping opportunities must not be prioritized.

Hyphenation is not applied.Note: This value triggers the line breaking rules typically seen in terminals.

Note: anywhere only allows preserved white spaces at the end of the line

to be wrapped to the next line

when white-space is set to break-spaces,

because in other cases:- preserved white space at the end/start of the line is discarded

(normal, pre-line) - wrapping is forbidden altogether (nowrap, pre)

- the preserved white space hang (pre-wrap).

When it does have an effect on preserved white space,

with white-space: break-spaces,

it allows breaking before the first space of a sequence,

which break-spaces on its own does not. - preserved white space at the end/start of the line is discarded

CSS distinguishes between four levels of strictness

in the rules for text wrapping.

The precise set of rules in effect for each of loose, normal,

and strict is up to the UA

and should follow language conventions.

However, this specification does require that:

-

The following breaks are forbidden in strict line breaking

and allowed in normal and loose:- breaks before Japanese small kana

or the Katakana-Hiragana prolonged sound mark,

i.e. characters

from the Unicode line breaking classCJ. [UAX14]

- breaks before Japanese small kana

-

The following breaks are allowed for normal and loose line breaking

if the writing system is Chinese or Japanese,

and are otherwise forbidden:- breaks before certain CJK hyphen-like characters:

〜 U+301C,

゠ U+30A0

- breaks before certain CJK hyphen-like characters:

-

The following breaks are allowed for loose line breaking

if the preceding character

belongs to the Unicode line breaking classID[UAX14] (including when the preceding character

is treated asIDdue to word-break: break-all),

and are otherwise forbidden:- breaks before hyphens:

‐ U+2010, – U+2013

- breaks before hyphens:

-

The following breaks are forbidden for normal and strict line breaking

and allowed in loose:- breaks before iteration marks:

々 U+3005, 〻 U+303B, ゝ U+309D,

ゞ U+309E, ヽ U+30FD, ヾ U+30FE - breaks between inseparable characters

(such as ‥ U+2025, … U+2026)

i.e. characters from the Unicode line breaking classIN. [UAX14]

- breaks before iteration marks:

-

The following breaks are allowed for loose if the writing system is Chinese or Japanese and are otherwise forbidden:

- breaks before certain centered punctuation marks:

・ U+30FB,

: U+FF1A, ; U+FF1B, ・ U+FF65,

‼ U+203C,

⁇ U+2047, ⁈ U+2048, ⁉ U+2049,

! U+FF01, ? U+FF1F - breaks before suffixes:

Characters with the Unicode line breaking classPO[UAX14] and the East Asian Width property [UAX11]Ambiguous,Fullwidth,

orWide. - breaks after prefixes:

Characters with the Unicode line breaking classPR[UAX14] and the East Asian Width property [UAX11]Ambiguous,Fullwidth,

orWide.

- breaks before certain centered punctuation marks:

Note: The requirements listed above

only create distinctions in CJK text.

In an implementation that matches only the rules above,

and no additional rules, line-break would only affect CJK code points

unless the writing system is tagged as Chinese or Japanese.

Future levels may add additional specific rules

for other writing systems and languages

as their requirements become known.

As UAs can add additional distinctions

between strict/normal/loose modes,

these values can exhibit differences in other writing systems as well.

For example, a UA with sufficiently-advanced Thai language processing ability

could choose to map different levels of strictness in Thai line-breaking

to these keywords,

e.g. disallowing breaks within compound words in strict mode

(e.g. breaking ตัวอย่างการเขียนภาษาไทย as ตัวอย่าง·การเขียน·ภาษาไทย)

while allowing more breaks in loose (ตัวอย่าง·การ·เขียน·ภาษา·ไทย).

Note: The CSSWG recognizes that in a future edition of the specification

finer control over line breaking may be necessary

to satisfy high-end publishing requirements.

5.4. Hyphenation: the hyphens property

Hyphenation is the controlled splitting of words

where they usually would not be allowed to break

to improve the layout of paragraphs,

typically splitting words at syllabic or morphemic boundaries

and visually indicating the split

(usually by inserting a hyphen, U+2010).

In some cases, hyphenation may also alter the spelling of a word.

Regardless, hyphenation is a rendering effect only:

it must have no effect on the underlying document content

or on text selection or searching.

Hyphenation Across Languages

Hyphenation practices vary across languages,

and can involve not just inserting a hyphen before the line break,

but inserting a hyphen after the break (or both),

inserting a different character than U+2010,

or changing the spelling of the word.

| Language | Unbroken | Before | After |

|---|---|---|---|

| English | Unbroken | Un‐ | broken |

| Dutch | cafeetje | café‐ | tje |

| Hungarian | Összeg | Ösz‐ | szeg |

| Mandarin | tú’àn | tú‐ | àn |

| àizēng‐fēnmíng | àizēng‐ | ‐fēnmíng | |

| Uyghur | داميدى | داميـ | دى |

Hyphenation occurs

when the line breaks at a valid hyphenation opportunity,

which is a type of soft wrap opportunity that exists within a word where hyphenation is allowed.

In CSS hyphenation opportunities are controlled

with the hyphens property.

CSS Text Level 3 does not define the exact rules for hyphenation;

however UAs are strongly encouraged

to optimize their choice of break points

and to chose language-appropriate hyphenation points.

Note: The soft wrap opportunity introduced by

the U+002D — HYPHEN-MINUS character

or the U+2010 ‐ HYPHEN character

is not a hyphenation opportunity,

as no visual indication of the split is created when wrapping:

these characters are visible whether the line is wrapped at that point or not.

Hyphenation opportunities are considered when calculating min-content intrinsic sizes.

Note: This allows tables to hyphenate their contents

instead of overflowing their containing block,

which is particularly important in long-word languages like German.

| Name: | hyphens |

|---|---|

| Value: | none | manual | auto |

| Initial: | manual |

| Applies to: | text |

| Inherited: | yes |

| Percentages: | n/a |

| Computed value: | specified keyword |

| Canonical order: | n/a |

| Animation type: | discrete |

This property controls whether hyphenation is allowed to create more soft wrap opportunities within a line of text.

Values have the following meanings:

- none

-

Words are not hyphenated,

even if characters inside the word

explicitly define hyphenation opportunities.Note: This does not suppress the existing soft wrap opportunities introduced by always visible characters such as

U+002D — HYPHEN-MINUS

or U+2010 ‐ HYPHEN. - manual

-

Words are only hyphenated where there are characters inside the word

that explicitly suggest hyphenation opportunities.

The UA must use the appropriate language-specific hyphenation character(s)

and should apply any appropriate spelling changes

just as for automatic hyphenation at the same point.In Unicode, U+00AD is a conditional «soft hyphen»

and U+2010 is an unconditional hyphen. Unicode Standard Annex #14 describes the role of soft hyphens in Unicode line breaking. [UAX14] In HTML,

­ represents the soft hyphen character,

which suggests a hyphenation opportunity.ex­ample

- auto

- Words may be broken at hyphenation opportunities determined automatically by a language-appropriate hyphenation resource

in addition to those indicated explicitly by a conditional hyphen.

Automatic hyphenation opportunities elsewhere within a word must be ignored

if the word contains a conditional hyphen

(­ or U+00AD SOFT HYPHEN),

in favor of the conditional hyphen(s).

However, if, even after breaking at such opportunities,

a portion of that word is still too long to fit on one line,

an automatic hyphenation opportunity may be used.

Correct automatic hyphenation requires a hyphenation resource

appropriate to the language of the text being broken.

The UA must therefore only automatically hyphenate text

for which the content language is known

and for which it has an appropriate hyphenation resource.

Authors should correctly tag their content’s language (e.g. using the HTML lang attribute

or XML xml:lang attribute)

in order to obtain correct automatic hyphenation.

The UA may use language-tailored heuristics

to exclude certain words

from automatic hyphenation.

For example, a UA might try to avoid hyphenation in proper nouns

by excluding words matching certain capitalization and punctuation patterns.

Such heuristics are not defined by this specification.

(Note that such heuristics will need to vary by language:

English and German, for example, have very different capitalization conventions.)

For the purpose of the hyphens property,

what constitutes a “word” is UA-dependent.

However, inline element boundaries

and out-of-flow elements

must be ignored when determining word boundaries.

Any glyphs shown due to hyphenation

at a hyphenation opportunity created by a conditional hyphen character

(such as U+00AD SOFT HYPHEN)

are represented by that character

and are styled according to the properties applied to it.

When shaping scripts such as Arabic are allowed to break within words

due to hyphenation,

the characters must still be shaped

as if the word were not broken (see § 5.6 Shaping Across Intra-word Breaks).

For example, if the Uyghur word “داميدى”

were hyphenated, it would appear as ![[isolated DAL + isolated ALEF + initial MEEM +

medial YEH + hyphen + line-break + final DAL +

isolated ALEF MAKSURA]](https://www.w3.org/TR/css-text-3/images/uyghur-hyphenate-joined.png)

![[isolated DAL + isolated ALEF + initial MEEM +

final YEH + hyphen + line-break + isolated DAL +

isolated ALEF MAKSURA]](https://www.w3.org/TR/css-text-3/images/uyghur-hyphenate-unjoined.png)

5.5. Overflow Wrapping: the overflow-wrap/word-wrap property

| Name: | overflow-wrap, word-wrap |

|---|---|

| Value: | normal | break-word | anywhere |

| Initial: | normal |

| Applies to: | text |

| Inherited: | yes |

| Percentages: | n/a |

| Computed value: | specified keyword |

| Canonical order: | n/a |

| Animation type: | discrete |

This property specifies whether the UA may break

at otherwise disallowed points within a line

to prevent overflow,

when an otherwise-unbreakable string is too long to fit within the line box.

It only has an effect when white-space allows wrapping. Possible values:

- normal

- Lines may break only at allowed break points.

However,

the restrictions introduced by word-break: keep-all may be relaxed

to match word-break: normal if there are no otherwise-acceptable break points in the line. - anywhere

- An otherwise unbreakable sequence of characters may be broken at an arbitrary point

if there are no otherwise-acceptable break points in the line.

Shaping characters are still shaped

as if the word were not broken,

and grapheme clusters must stay together as one unit.

No hyphenation character is inserted at the break point. Soft wrap opportunities introduced by anywhere are considered when calculating min-content intrinsic sizes. - break-word

- As for anywhere except that soft wrap opportunities introduced by break-word are not considered

when calculating min-content intrinsic sizes.

For legacy reasons, UAs must treat word-wrap as a legacy name alias of the overflow-wrap property.

5.6. Shaping Across Intra-word Breaks

When shaping scripts such as Arabic wrap at unforced soft wrap opportunities within words

(such as when breaking due to word-break: break-all, line-break: anywhere, overflow-wrap: break-word, overflow-wrap: anywhere,

or when hyphenating)

the characters must still be shaped

(their joining forms chosen)

as if the word were still whole.

For example,

if the word “نوشتن” is broken between the “ش” and “ت”,

the “ش” still takes its initial form (“ﺷ”),

and the “ت” its medial form (“ﺘ”)—forming as in “ﻧﻮﺷ | ﺘﻦ”, not as in “نوش | تن”.

6. Alignment and Justification

Alignment and justification controls

how inline content is distributed within a line box.

6.1. Text Alignment: the text-align shorthand

| Name: | text-align |

|---|---|

| Value: | start | end | left | right | center | justify | match-parent | justify-all |

| Initial: | start |

| Applies to: | block containers |

| Inherited: | yes |

| Percentages: | see individual properties |

| Computed value: | see individual properties |

| Animation type: | discrete |

| Canonical order: | n/a |

This shorthand property sets the text-align-all and text-align-last properties

and describes how the inline-level content of a block

is aligned along the inline axis

if the content does not completely fill the line box.

Values other than justify-all or match-parent are assigned to text-align-all and reset text-align-last to auto.

Values have the following meanings:

- start

- Inline-level content is aligned

to the start edge of the line box. - end

- Inline-level content is aligned

to the end edge of the line box. - left

- Inline-level content is aligned

to the line-left edge of the line box.

(In vertical writing modes,

this can be either the physical top or bottom,

depending on writing-mode.) [CSS-WRITING-MODES-4] - right

- Inline-level content is aligned

to the line-right edge of the line box.

(In vertical writing modes,

this can be either the physical top or bottom,

depending on writing-mode.) [CSS-WRITING-MODES-4] - center

- Inline-level content is centered within the line box.

- justify

- Text is justified

according to the method specified by the text-justify property,

in order to exactly fill the line box.

Unless otherwise specified by text-align-last,

the last line before a forced break

or the end of the block

is start-aligned. - justify-all

- Sets both text-align-all and text-align-last to justify,

forcing the last line to justify as well. - match-parent

-

This value behaves the same as inherit (computes to its parent’s computed value)

except that an inherited value of start or end is interpreted against the parent’s direction value

and results in a computed value of either left or right.

Computes to start when specified on the root element.When specified on the text-align shorthand,

sets both text-align-all and text-align-last to match-parent.

A block of text

is a stack of line boxes.

This property specifies how the inline-level boxes within each line box

align with respect to the start and end sides of the line box.

Alignment is not with respect to the viewport or containing block.

In the case of justify,

the UA may stretch or shrink any inline boxes

by adjusting their text.

(See text-justify.)

If an element’s white space is not collapsible,

then the UA is not required to adjust its text

for the purpose of justification

and may instead treat the text

as having no justification opportunities.

If the UA chooses to adjust the text,

then it must ensure

that tab stops continue to line up as required by the white space processing rules.

If (after justification, if any)

the inline contents of a line box are too long to fit within it,

then the contents are start-aligned:

any content that doesn’t fit

overflows the line box’s end edge.

See § 8.3 Bidirectionality and Line Boxes for details on how to determine

the start and end edges

of a line box.

6.2. Default Text Alignment: the text-align-all property

| Name: | text-align-all |

|---|---|

| Value: | start | end | left | right | center | justify | match-parent |

| Initial: | start |

| Applies to: | block containers |

| Inherited: | yes |

| Percentages: | n/a |

| Computed value: | keyword as specified, except for match-parent which computes as defined above |

| Canonical order: | n/a |

| Animation type: | discrete |

This longhand of the text-align shorthand property specifies the inline alignment of all lines of inline content in the block container,

except for last lines

overridden by a non-auto value of text-align-last.

See text-align for a full description of values.

Authors should use the text-align shorthand instead of this property.

6.3. Last Line Alignment: the text-align-last property

| Name: | text-align-last |

|---|---|

| Value: | auto | start | end | left | right | center | justify | match-parent |

| Initial: | auto |

| Applies to: | block containers |

| Inherited: | yes |

| Percentages: | n/a |

| Computed value: | specified keyword |

| Canonical order: | n/a |

| Animation type: | discrete |

This property describes how the last line of a block or a line

right before a forced line break is aligned.

If auto is specified,

content on the affected line is aligned per text-align-all unless text-align-all is set to justify,

in which case it is start-aligned.

All other values are interpreted as described for text-align.

6.4. Justification Method: the text-justify property

| Name: | text-justify |

|---|---|

| Value: | auto | none | inter-word | inter-character |

| Initial: | auto |

| Applies to: | text |

| Inherited: | yes |

| Percentages: | n/a |

| Computed value: | specified keyword (except for the distribute legacy value) |

| Canonical order: | n/a |

| Animation type: | discrete |

This property selects the justification method

used when a line’s alignment is set to justify (see text-align).

The property applies to text,

but is inherited from block containers

to the root inline box containing their inline-level contents.

It takes the following values:

- auto

-

The UA determines the justification algorithm to follow,

based on a balance between performance and adequate presentation quality.

Since justification rules vary by writing system and language,

UAs should, where possible,

use a justification algorithm appropriate to the text.For example,

the UA could use by default a justification method

that is a simple universal compromise for all writing systems—such as primarily expanding word separators and between CJK typographic letter units along with secondarily expanding

between Southeast Asian typographic letter units.

Then, in cases where the content language of the paragraph is known,

it could choose a more language-tailored justification behavior

e.g. following the Requirements for Japanese Text Layout for Japanese [JLREQ],

using cursive elongation for Arabic,

using inter-word for German,

etc.An example of cursively-justified Arabic text,

rendered by Tasmeem.

Like English,

Arabic can be justified by adjusting the spacing between words,

but in most styles

it can also be justified by calligraphically elongating

or compressing the letterforms themselves.

In this example,

the upper text is extended to fill the line

by the use of elongated (kashida) forms and swash forms,

while the bottom line is compressed slightly

by using a stacked combination for the characters between ت and م.

By employing traditional calligraphic techniques,

a typesetter can justify the line while preserving flow and color,

providing a very high quality justification effect.

However, this is by its nature a very script-specific effect.Mixed-script text with text-justify: auto:

this interpretation uses a universal-compromise justification method,

expanding at spaces as well as between CJK and Southeast Asian letters.

This effectively uses inter-word + inter-ideograph spacing

for lines that have word-separators and/or CJK characters

and falls back to inter-cluster behavior for lines that don’t

or for which the space stretches too far. - none

-

Justification is disabled:

there are no justification opportunities within the text.Mixed-script text with text-justify: none Note: This value is intended for use in user stylesheets

to improve readability or for accessibility purposes. - inter-word

-

Justification adjusts spacing at word separators only

(effectively varying the used word-spacing on the line).

This behavior is typical for languages that separate words using spaces,

like English or Korean.Mixed-script text with text-justify: inter-word - inter-character

-

Justification adjusts spacing

between each pair of adjacent typographic character units (effectively varying the used letter-spacing on the line).

This value is sometimes used in East Asian systems such as Japanese.Mixed-script text with text-justify: inter-character For legacy reasons,

UAs must also support the alternate keyword distribute which must compute to inter-character,

thus having the exact same meaning and behavior.

UAs may treat this as a legacy value alias.

Since optimal justification is language-sensitive,

authors should correctly language-tag their content for the best results.

Note: The guidelines in this level of CSS

do not describe a complete justification algorithm.

They are merely a minimum set of requirements

that a complete algorithm should meet.

Limiting the set of requirements gives UAs some latitude

in choosing a justification algorithm

that meets their needs and desired balance of quality, speed, and complexity.

6.4.1. Expanding and Compressing Text

When justifying text,

the user agent takes the remaining space