A copyright is a type of intellectual property that gives its owner the exclusive right to copy, distribute, adapt, display, and perform a creative work, usually for a limited time.[1][2][3][4][5] The creative work may be in a literary, artistic, educational, or musical form. Copyright is intended to protect the original expression of an idea in the form of a creative work, but not the idea itself.[6][7][8] A copyright is subject to limitations based on public interest considerations, such as the fair use doctrine in the United States.

Some jurisdictions require «fixing» copyrighted works in a tangible form. It is often shared among multiple authors, each of whom holds a set of rights to use or license the work, and who are commonly referred to as rights holders.[9][10][11][12][13][better source needed] These rights frequently include reproduction, control over derivative works, distribution, public performance, and moral rights such as attribution.[14]

Copyrights can be granted by public law and are in that case considered «territorial rights». This means that copyrights granted by the law of a certain state do not extend beyond the territory of that specific jurisdiction. Copyrights of this type vary by country; many countries, and sometimes a large group of countries, have made agreements with other countries on procedures applicable when works «cross» national borders or national rights are inconsistent.[15]

Typically, the public law duration of a copyright expires 50 to 100 years after the creator dies, depending on the jurisdiction. Some countries require certain copyright formalities[5] to establishing copyright, others recognize copyright in any completed work, without a formal registration. When the copyright of a work expires, it enters the public domain.

History

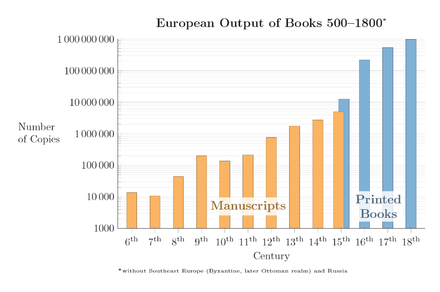

European output of books before the advent of copyright, 6th century to 18th century. Blue shows printed books. Log-lin plot; a straight line therefore shows an exponential increase.

Background

The concept of copyright developed after the printing press came into use in Europe[16] in the 15th and 16th centuries.[17] The printing press made it much cheaper to produce works, but as there was initially no copyright law, anyone could buy or rent a press and print any text. Popular new works were immediately re-set and re-published by competitors, so printers needed a constant stream of new material. Fees paid to authors for new works were high, and significantly supplemented the incomes of many academics.[18]

Printing brought profound social changes. The rise in literacy across Europe led to a dramatic increase in the demand for reading matter.[16] Prices of reprints were low, so publications could be bought by poorer people, creating a mass audience.[18] In German language markets before the advent of copyright, technical materials, like popular fiction, were inexpensive and widely available; it has been suggested this contributed to Germany’s industrial and economic success.[18] After copyright law became established (in 1710 in England and Scotland, and in the 1840s in German-speaking areas) the low-price mass market vanished, and fewer, more expensive editions were published; distribution of scientific and technical information was greatly reduced.[18][19]

Conception

The concept of copyright first developed in England. In reaction to the printing of «scandalous books and pamphlets», the English Parliament passed the Licensing of the Press Act 1662,[16] which required all intended publications to be registered with the government-approved Stationers’ Company, giving the Stationers the right to regulate what material could be printed.[20]

The Statute of Anne, enacted in 1710 in England and Scotland provided the first legislation to protect copyrights (but not authors’ rights). The Copyright Act of 1814 extended more rights for authors but did not protect British from reprinting in the US. The Berne International Copyright Convention of 1886 finally provided protection for authors among the countries who signed the agreement, although the US did not join the Berne Convention until 1989.[21]

In the US, the Constitution grants Congress the right to establish copyright and patent laws. Shortly after the Constitution was passed, Congress enacted the Copyright Act of 1790, modeling it after the Statute of Anne. While the national law protected authors’ published works, authority was granted to the states to protect authors’ unpublished works. The most recent major overhaul of copyright in the US, the 1976 Copyright Act, extended federal copyright to works as soon as they are created and «fixed», without requiring publication or registration. State law continues to apply to unpublished works that are not otherwise copyrighted by federal law.[21] This act also changed the calculation of copyright term from a fixed term (then a maximum of fifty-six years) to «life of the author plus 50 years». These changes brought the US closer to conformity with the Berne Convention, and in 1989 the United States further revised its copyright law and joined the Berne Convention officially.[21]

Copyright laws allow products of creative human activities, such as literary and artistic production, to be preferentially exploited and thus incentivized. Different cultural attitudes, social organizations, economic models and legal frameworks are seen to account for why copyright emerged in Europe and not, for example, in Asia. In the Middle Ages in Europe, there was generally a lack of any concept of literary property due to the general relations of production, the specific organization of literary production and the role of culture in society. The latter refers to the tendency of oral societies, such as that of Europe in the medieval period, to view knowledge as the product and expression of the collective, rather than to see it as individual property. However, with copyright laws, intellectual production comes to be seen as a product of an individual, with attendant rights. The most significant point is that patent and copyright laws support the expansion of the range of creative human activities that can be commodified. This parallels the ways in which capitalism led to the commodification of many aspects of social life that earlier had no monetary or economic value per se.[22]

Copyright has developed into a concept that has a significant effect on nearly every modern industry, including not just literary work, but also forms of creative work such as sound recordings, films, photographs, software, and architecture.

National copyrights

Often seen as the first real copyright law, the 1709 British Statute of Anne gave the publishers rights for a fixed period, after which the copyright expired.[23]

The act also alluded to individual rights of the artist. It began, «Whereas Printers, Booksellers, and other Persons, have of late frequently taken the Liberty of Printing … Books, and other Writings, without the Consent of the Authors … to their very great Detriment, and too often to the Ruin of them and their Families:».[24] A right to benefit financially from the work is articulated, and court rulings and legislation have recognized a right to control the work, such as ensuring that the integrity of it is preserved. An irrevocable right to be recognized as the work’s creator appears in some countries’ copyright laws.

The Copyright Clause of the United States, Constitution (1787) authorized copyright legislation: «To promote the Progress of Science and useful Arts, by securing for limited Times to Authors and Inventors the exclusive Right to their respective Writings and Discoveries.» That is, by guaranteeing them a period of time in which they alone could profit from their works, they would be enabled and encouraged to invest the time required to create them, and this would be good for society as a whole. A right to profit from the work has been the philosophical underpinning for much legislation extending the duration of copyright, to the life of the creator and beyond, to their heirs.

The original length of copyright in the United States was 14 years, and it had to be explicitly applied for. If the author wished, they could apply for a second 14‑year monopoly grant, but after that the work entered the public domain, so it could be used and built upon by others.

Copyright law was enacted rather late in German states, and the historian Eckhard Höffner argues that the absence of copyright laws in the early 19th century encouraged publishing, was profitable for authors, led to a proliferation of books, enhanced knowledge, and was ultimately an important factor in the ascendency of Germany as a power during that century.[25] However, empirical evidence derived from the exogenous differential introduction of copyright in Napoleonic Italy shows that «basic copyrights increased both the number and the quality of operas, measured by their popularity and durability».[26]

International copyright treaties

The Pirate Publisher—An International Burlesque that has the Longest Run on Record, from Puck, 1886, satirizes the then-existing situation where a publisher could profit by simply copying newly published works from one country, and publishing them in another, and vice versa.

The 1886 Berne Convention first established recognition of copyrights among sovereign nations, rather than merely bilaterally. Under the Berne Convention, copyrights for creative works do not have to be asserted or declared, as they are automatically in force at creation: an author need not «register» or «apply for» a copyright in countries adhering to the Berne Convention.[27] As soon as a work is «fixed», that is, written or recorded on some physical medium, its author is automatically entitled to all copyrights in the work, and to any derivative works unless and until the author explicitly disclaims them, or until the copyright expires. The Berne Convention also resulted in foreign authors being treated equivalently to domestic authors, in any country signed onto the Convention. The UK signed the Berne Convention in 1887 but did not implement large parts of it until 100 years later with the passage of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. Specially, for educational and scientific research purposes, the Berne Convention provides the developing countries issue compulsory licenses for the translation or reproduction of copyrighted works within the limits prescribed by the Convention. This was a special provision that had been added at the time of 1971 revision of the Convention, because of the strong demands of the developing countries. The United States did not sign the Berne Convention until 1989.[28]

The United States and most Latin American countries instead entered into the Buenos Aires Convention in 1910, which required a copyright notice on the work (such as all rights reserved), and permitted signatory nations to limit the duration of copyrights to shorter and renewable terms.[29][30][31] The Universal Copyright Convention was drafted in 1952 as another less demanding alternative to the Berne Convention, and ratified by nations such as the Soviet Union and developing nations.

The regulations of the Berne Convention are incorporated into the World Trade Organization’s TRIPS agreement (1995), thus giving the Berne Convention effectively near-global application.[32]

In 1961, the United International Bureaux for the Protection of Intellectual Property signed the Rome Convention for the Protection of Performers, Producers of Phonograms and Broadcasting Organizations. In 1996, this organization was succeeded by the founding of the World Intellectual Property Organization, which launched the 1996 WIPO Performances and Phonograms Treaty and the 2002 WIPO Copyright Treaty, which enacted greater restrictions on the use of technology to copy works in the nations that ratified it. The Trans-Pacific Partnership includes intellectual Property Provisions relating to copyright.

Copyright laws are standardized somewhat through these international conventions such as the Berne Convention and Universal Copyright Convention. These multilateral treaties have been ratified by nearly all countries, and international organizations such as the European Union or World Trade Organization require their member states to comply with them.

Obtaining protection

Ownership

The original holder of the copyright may be the employer of the author rather than the author themself if the work is a «work for hire».[33][34] For example, in English law the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 provides that if a copyrighted work is made by an employee in the course of that employment, the copyright is automatically owned by the employer which would be a «Work for Hire». Typically, the first owner of a copyright is the person who created the work i.e. the author.[35] But when more than one person creates the work, then a case of joint authorship can be made provided some criteria are met.

Eligible works

Copyright may apply to a wide range of creative, intellectual, or artistic forms, or «works». Specifics vary by jurisdiction, but these can include poems, theses, fictional characters, plays and other literary works, motion pictures, choreography, musical compositions, sound recordings, paintings, drawings, sculptures, photographs, computer software, radio and television broadcasts, and industrial designs. Graphic designs and industrial designs may have separate or overlapping laws applied to them in some jurisdictions.[36][37]

Copyright does not cover ideas and information themselves, only the form or manner in which they are expressed.[38] For example, the copyright to a Mickey Mouse cartoon restricts others from making copies of the cartoon or creating derivative works based on Disney’s particular anthropomorphic mouse, but does not prohibit the creation of other works about anthropomorphic mice in general, so long as they are different enough to not be judged copies of Disney’s.[38] Note additionally that Mickey Mouse is not copyrighted because characters cannot be copyrighted; rather, Steamboat Willie is copyrighted and Mickey Mouse, as a character in that copyrighted work, is afforded protection.

Originality

Typically, a work must meet minimal standards of originality in order to qualify for copyright, and the copyright expires after a set period of time (some jurisdictions may allow this to be extended). Different countries impose different tests, although generally the requirements are low; in the United Kingdom there has to be some «skill, labour, and judgment» that has gone into it.[39] In Australia and the United Kingdom it has been held that a single word is insufficient to comprise a copyright work. However, single words or a short string of words can sometimes be registered as a trademark instead.

Copyright law recognizes the right of an author based on whether the work actually is an original creation, rather than based on whether it is unique; two authors may own copyright on two substantially identical works, if it is determined that the duplication was coincidental, and neither was copied from the other.

Registration

In all countries where the Berne Convention standards apply, copyright is automatic, and need not be obtained through official registration with any government office. Once an idea has been reduced to tangible form, for example by securing it in a fixed medium (such as a drawing, sheet music, photograph, a videotape, or a computer file), the copyright holder is entitled to enforce their exclusive rights.[27] However, while registration is not needed to exercise copyright, in jurisdictions where the laws provide for registration, it serves as prima facie evidence of a valid copyright and enables the copyright holder to seek statutory damages and attorney’s fees.[40] (In the US, registering after an infringement only enables one to receive actual damages and lost profits.)

A widely circulated strategy to avoid the cost of copyright registration is referred to as the poor man’s copyright. It proposes that the creator send the work to themself in a sealed envelope by registered mail, using the postmark to establish the date. This technique has not been recognized in any published opinions of the United States courts. The United States Copyright Office says the technique is not a substitute for actual registration.[41] The United Kingdom Intellectual Property Office discusses the technique and notes that the technique (as well as commercial registries) does not constitute dispositive proof that the work is original or establish who created the work.[42][43]

Fixing

The Berne Convention allows member countries to decide whether creative works must be «fixed» to enjoy copyright. Article 2, Section 2 of the Berne Convention states: «It shall be a matter for legislation in the countries of the Union to prescribe that works in general or any specified categories of works shall not be protected unless they have been fixed in some material form.» Some countries do not require that a work be produced in a particular form to obtain copyright protection. For instance, Spain, France, and Australia do not require fixation for copyright protection. The United States and Canada, on the other hand, require that most works must be «fixed in a tangible medium of expression» to obtain copyright protection.[44] US law requires that the fixation be stable and permanent enough to be «perceived, reproduced or communicated for a period of more than transitory duration». Similarly, Canadian courts consider fixation to require that the work be «expressed to some extent at least in some material form, capable of identification and having a more or less permanent endurance».[44]

Note this provision of US law: c) Effect of Berne Convention.—No right or interest in a work eligible for protection under this title may be claimed by virtue of, or in reliance upon, the provisions of the Berne Convention, or the adherence of the United States thereto. Any rights in a work eligible for protection under this title that derive from this title, other Federal or State statutes, or the common law, shall not be expanded or reduced by virtue of, or in reliance upon, the provisions of the Berne Convention, or the adherence of the United States thereto.[45]

Copyright notice

A copyright symbol used in copyright notice

A copyright symbol embossed on a piece of paper.

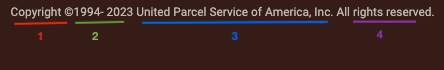

Before 1989, United States law required the use of a copyright notice, consisting of the copyright symbol (©, the letter C inside a circle), the abbreviation «Copr.», or the word «Copyright», followed by the year of the first publication of the work and the name of the copyright holder.[46][47] Several years may be noted if the work has gone through substantial revisions. The proper copyright notice for sound recordings of musical or other audio works is a sound recording copyright symbol (℗, the letter P inside a circle), which indicates a sound recording copyright, with the letter P indicating a «phonorecord». In addition, the phrase All rights reserved which indicates that the copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use was once required to assert copyright, but that phrase is now legally obsolete. Almost everything on the Internet has some sort of copyright attached to it. Whether these things are watermarked, signed, or have any other sort of indication of the copyright is a different story however.[48]

In 1989 the United States enacted the Berne Convention Implementation Act, amending the 1976 Copyright Act to conform to most of the provisions of the Berne Convention. As a result, the use of copyright notices has become optional to claim copyright, because the Berne Convention makes copyright automatic.[49] However, the lack of notice of copyright using these marks may have consequences in terms of reduced damages in an infringement lawsuit – using notices of this form may reduce the likelihood of a defense of «innocent infringement» being successful.[50]

Enforcement

Copyrights are generally enforced by the holder in a civil law court, but there are also criminal infringement statutes in some jurisdictions. While central registries are kept in some countries which aid in proving claims of ownership, registering does not necessarily prove ownership, nor does the fact of copying (even without permission) necessarily prove that copyright was infringed. Criminal sanctions are generally aimed at serious counterfeiting activity, but are now becoming more commonplace as copyright collectives such as the RIAA are increasingly targeting the file sharing home Internet user. Thus far, however, most such cases against file sharers have been settled out of court. (See Legal aspects of file sharing)

In most jurisdictions the copyright holder must bear the cost of enforcing copyright. This will usually involve engaging legal representation, administrative or court costs. In light of this, many copyright disputes are settled by a direct approach to the infringing party in order to settle the dispute out of court.

«…by 1978, the scope was expanded to apply to any ‘expression’ that has been ‘fixed’ in any medium, this protection granted automatically whether the maker wants it or not, no registration required.»[51]

Copyright infringement

For a work to be considered to infringe upon copyright, its use must have occurred in a nation that has domestic copyright laws or adheres to a bilateral treaty or established international convention such as the Berne Convention or WIPO Copyright Treaty. Improper use of materials outside of legislation is deemed «unauthorized edition», not copyright infringement.[52]

Statistics regarding the effects of copyright infringement are difficult to determine. Studies have attempted to determine whether there is a monetary loss for industries affected by copyright infringement by predicting what portion of pirated works would have been formally purchased if they had not been freely available.[53] Other reports indicate that copyright infringement does not have an adverse effect on the entertainment industry, and can have a positive effect.[54] In particular, a 2014 university study concluded that free music content, accessed on YouTube, does not necessarily hurt sales, instead has the potential to increase sales.[55]

According to the IP Commission Report the annual cost of intellectual property theft to the US economy «continues to exceed $225 billion in counterfeit goods, pirated software, and theft of trade secrets and could be as high as $600 billion.»[56] A 2019 study sponsored by the US Chamber of Commerce Global Innovation Policy Center (GIPC), in partnership with NERA Economic Consulting «estimates that global online piracy costs the U.S. economy at least $29.2 billion in lost revenue each year.»[57] An August 2021 report by the Digital Citizens Alliance states that «online criminals who offer stolen movies, TV shows, games, and live events through websites and apps are reaping $1.34 billion in annual advertising revenues.» This comes as a result of users visiting pirate websites who are then subjected to pirated content, malware, and fraud.[58]

Rights granted

According to World Intellectual Property Organisation, copyright protects two types of rights. Economic rights allow right owners to derive financial reward from the use of their works by others. Moral rights allow authors and creators to take certain actions to preserve and protect their link with their work. The author or creator may be the owner of the economic rights or those rights may be transferred to one or more copyright owners. Many countries do not allow the transfer of moral rights.[59]

Economic rights

With any kind of property, its owner may decide how it is to be used, and others can use it lawfully only if they have the owner’s permission, often through a license. The owner’s use of the property must, however, respect the legally recognised rights and interests of other members of society. So the owner of a copyright-protected work may decide how to use the work, and may prevent others from using it without permission. National laws usually grant copyright owners exclusive rights to allow third parties to use their works, subject to the legally recognised rights and interests of others.[59] Most copyright laws state that authors or other right owners have the right to authorise or prevent certain acts in relation to a work. Right owners can authorise or prohibit:

- reproduction of the work in various forms, such as printed publications or sound recordings;

- distribution of copies of the work;

- public performance of the work;

- broadcasting or other communication of the work to the public;

- translation of the work into other languages; and

- adaptation of the work, such as turning a novel into a screenplay.

Moral rights

Moral rights are concerned with the non-economic rights of a creator. They protect the creator’s connection with a work as well as the integrity of the work. Moral rights are only accorded to individual authors and in many national laws they remain with the authors even after the authors have transferred their economic rights. In some EU countries, such as France, moral rights last indefinitely. In the UK, however, moral rights are finite. That is, the right of attribution and the right of integrity last only as long as the work is in copyright. When the copyright term comes to an end, so too do the moral rights in that work. This is just one reason why the moral rights regime within the UK is often regarded as weaker or inferior to the protection of moral rights in continental Europe and elsewhere in the world.[60] The Berne Convention, in Article 6bis, requires its members to grant authors the following rights:

- the right to claim authorship of a work (sometimes called the right of paternity or the right of attribution); and

- the right to object to any distortion or modification of a work, or other derogatory action in relation to a work, which would be prejudicial to the author’s honour or reputation (sometimes called the right of integrity).

These and other similar rights granted in national laws are generally known as the moral rights of authors. The Berne Convention requires these rights to be independent of authors’ economic rights. Moral rights are only accorded to individual authors and in many national laws they remain with the authors even after the authors have transferred their economic rights. This means that even where, for example, a film producer or publisher owns the economic rights in a work, in many jurisdictions the individual author continues to have moral rights.[59] Recently, as a part of the debates being held at the US Copyright Office on the question of inclusion of Moral Rights as a part of the framework of the Copyright Law in United States, the Copyright Office concluded that many diverse aspects of the current moral rights patchwork – including copyright law’s derivative work right, state moral rights statutes, and contract law – are generally working well and should not be changed. Further, the Office concludes that there is no need for the creation of a blanket moral rights statute at this time. However, there are aspects of the US moral rights patchwork that could be improved to the benefit of individual authors and the copyright system as a whole.[61]

The Copyright Law in the United States, several exclusive rights are granted to the holder of a copyright, as are listed below:

- protection of the work;

- to determine and decide how, and under what conditions, the work may be marketed, publicly displayed, reproduced, distributed, etc.

- to produce copies or reproductions of the work and to sell those copies; (including, typically, electronic copies)

- to import or export the work;

- to create derivative works; (works that adapt the original work)

- to perform or display the work publicly;

- to sell or cede these rights to others;

- to transmit or display by radio, video or internet.[36]

The basic right when a work is protected by copyright is that the holder may determine and decide how and under what conditions the protected work may be used by others. This includes the right to decide to distribute the work for free. This part of copyright is often overseen. The phrase «exclusive right» means that only the copyright holder is free to exercise those rights, and others are prohibited from using the work without the holder’s permission. Copyright is sometimes called a «negative right», as it serves to prohibit certain people (e.g., readers, viewers, or listeners, and primarily publishers and would be publishers) from doing something they would otherwise be able to do, rather than permitting people (e.g., authors) to do something they would otherwise be unable to do. In this way it is similar to the unregistered design right in English law and European law. The rights of the copyright holder also permit him/her to not use or exploit their copyright, for some or all of the term. There is, however, a critique which rejects this assertion as being based on a philosophical interpretation of copyright law that is not universally shared. There is also debate on whether copyright should be considered a property right or a moral right.[62]

UK copyright law gives creators both economic rights and moral rights. While ‘copying’ someone else’s work without permission may constitute an infringement of their economic rights, that is, the reproduction right or the right of communication to the public, whereas, ‘mutilating’ it might infringe the creator’s moral rights. In the UK, moral rights include the right to be identified as the author of the work, which is generally identified as the right of attribution, and the right not to have your work subjected to ‘derogatory treatment’, that is the right of integrity.[60]

Indian copyright law is at parity with the international standards as contained in TRIPS. The Indian Copyright Act, 1957, pursuant to the amendments in 1999, 2002 and 2012, fully reflects the Berne Convention and the Universal Copyrights Convention, to which India is a party. India is also a party to the Geneva Convention for the Protection of Rights of Producers of Phonograms and is an active member of the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO) and United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). The Indian system provides both the economic and moral rights under different provisions of its Indian Copyright Act of 1957.[63]

Duration

Expansion of US copyright law (currently based on the date of creation or publication)

Copyright subsists for a variety of lengths in different jurisdictions. The length of the term can depend on several factors, including the type of work (e.g. musical composition, novel), whether the work has been published, and whether the work was created by an individual or a corporation. In most of the world, the default length of copyright is the life of the author plus either 50 or 70 years. In the United States, the term for most existing works is a fixed number of years after the date of creation or publication. Under most countries’ laws (for example, the United States[64] and the United Kingdom[65]), copyrights expire at the end of the calendar year in which they would otherwise expire.

The length and requirements for copyright duration are subject to change by legislation, and since the early 20th century there have been a number of adjustments made in various countries, which can make determining the duration of a given copyright somewhat difficult. For example, the United States used to require copyrights to be renewed after 28 years to stay in force, and formerly required a copyright notice upon first publication to gain coverage. In Italy and France, there were post-wartime extensions that could increase the term by approximately 6 years in Italy and up to about 14 in France. Many countries have extended the length of their copyright terms (sometimes retroactively). International treaties establish minimum terms for copyrights, but individual countries may enforce longer terms than those.[66]

In the United States, all books and other works, except for sound recordings, published before 1928 have expired copyrights and are in the public domain. The applicable date for sound recordings in the United States is before 1923.[67] In addition, works published before 1964 that did not have their copyrights renewed 28 years after first publication year also are in the public domain. Hirtle points out that the great majority of these works (including 93% of the books) were not renewed after 28 years and are in the public domain.[68] Books originally published outside the US by non-Americans are exempt from this renewal requirement, if they are still under copyright in their home country.

But if the intended exploitation of the work includes publication (or distribution of derivative work, such as a film based on a book protected by copyright) outside the US, the terms of copyright around the world must be considered. If the author has been dead more than 70 years, the work is in the public domain in most, but not all, countries.

In 1998, the length of a copyright in the United States was increased by 20 years under the Copyright Term Extension Act. This legislation was strongly promoted by corporations which had valuable copyrights which otherwise would have expired, and has been the subject of substantial criticism on this point.[69]

Limitations and exceptions

In many jurisdictions, copyright law makes exceptions to these restrictions when the work is copied for the purpose of commentary or other related uses. United States copyright law does not cover names, titles, short phrases or listings (such as ingredients, recipes, labels, or formulas).[70] However, there are protections available for those areas copyright does not cover, such as trademarks and patents.

Idea–expression dichotomy and the merger doctrine

The idea–expression divide differentiates between ideas and expression, and states that copyright protects only the original expression of ideas, and not the ideas themselves. This principle, first clarified in the 1879 case of Baker v. Selden, has since been codified by the Copyright Act of 1976 at 17 U.S.C. § 102(b).

The first-sale doctrine and exhaustion of rights

Copyright law does not restrict the owner of a copy from reselling legitimately obtained copies of copyrighted works, provided that those copies were originally produced by or with the permission of the copyright holder. It is therefore legal, for example, to resell a copyrighted book or CD. In the United States this is known as the first-sale doctrine, and was established by the courts to clarify the legality of reselling books in second-hand bookstores.

Some countries may have parallel importation restrictions that allow the copyright holder to control the aftermarket. This may mean for example that a copy of a book that does not infringe copyright in the country where it was printed does infringe copyright in a country into which it is imported for retailing. The first-sale doctrine is known as exhaustion of rights in other countries and is a principle which also applies, though somewhat differently, to patent and trademark rights. It is important to note that the first-sale doctrine permits the transfer of the particular legitimate copy involved. It does not permit making or distributing additional copies.

In Kirtsaeng v. John Wiley & Sons, Inc.,[71] in 2013, the United States Supreme Court held in a 6–3 decision that the first-sale doctrine applies to goods manufactured abroad with the copyright owner’s permission and then imported into the US without such permission. The case involved a plaintiff who imported Asian editions of textbooks that had been manufactured abroad with the publisher-plaintiff’s permission. The defendant, without permission from the publisher, imported the textbooks and resold on eBay. The Supreme Court’s holding severely limits the ability of copyright holders to prevent such importation.

In addition, copyright, in most cases, does not prohibit one from acts such as modifying, defacing, or destroying one’s own legitimately obtained copy of a copyrighted work, so long as duplication is not involved. However, in countries that implement moral rights, a copyright holder can in some cases successfully prevent the mutilation or destruction of a work that is publicly visible.

Fair use and fair dealing

Copyright does not prohibit all copying or replication. In the United States, the fair use doctrine, codified by the Copyright Act of 1976 as 17 U.S.C. Section 107, permits some copying and distribution without permission of the copyright holder or payment to same. The statute does not clearly define fair use, but instead gives four non-exclusive factors to consider in a fair use analysis. Those factors are:

- the purpose and character of one’s use;

- the nature of the copyrighted work;

- what amount and proportion of the whole work was taken;

- the effect of the use upon the potential market for or value of the copyrighted work.[72]

In the United Kingdom and many other Commonwealth countries, a similar notion of fair dealing was established by the courts or through legislation. The concept is sometimes not well defined; however in Canada, private copying for personal use has been expressly permitted by statute since 1999. In Alberta (Education) v. Canadian Copyright Licensing Agency (Access Copyright), 2012 SCC 37, the Supreme Court of Canada concluded that limited copying for educational purposes could also be justified under the fair dealing exemption. In Australia, the fair dealing exceptions under the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth) are a limited set of circumstances under which copyrighted material can be legally copied or adapted without the copyright holder’s consent. Fair dealing uses are research and study; review and critique; news reportage and the giving of professional advice (i.e. legal advice). Under current Australian law, although it is still a breach of copyright to copy, reproduce or adapt copyright material for personal or private use without permission from the copyright owner, owners of a legitimate copy are permitted to «format shift» that work from one medium to another for personal, private use, or to «time shift» a broadcast work for later, once and only once, viewing or listening. Other technical exemptions from infringement may also apply, such as the temporary reproduction of a work in machine readable form for a computer.

In the United States the AHRA (Audio Home Recording Act Codified in Section 10, 1992) prohibits action against consumers making noncommercial recordings of music, in return for royalties on both media and devices plus mandatory copy-control mechanisms on recorders.

Section 1008. Prohibition on certain infringement actions

No action may be brought under this title alleging infringement of copyright based on the manufacture, importation, or distribution of a digital audio recording device, a digital audio recording medium, an analog recording device, or an analog recording medium, or based on the noncommercial use by a consumer of such a device or medium for making digital musical recordings or analog musical recordings.

Later acts amended US Copyright law so that for certain purposes making 10 copies or more is construed to be commercial, but there is no general rule permitting such copying. Indeed, making one complete copy of a work, or in many cases using a portion of it, for commercial purposes will not be considered fair use. The Digital Millennium Copyright Act prohibits the manufacture, importation, or distribution of devices whose intended use, or only significant commercial use, is to bypass an access or copy control put in place by a copyright owner.[36][73][74] An appellate court has held that fair use is not a defense to engaging in such distribution.[citation needed]

EU copyright laws recognise the right of EU member states to implement some national exceptions to copyright. Examples of those exceptions are:

- photographic reproductions on paper or any similar medium of works (excluding sheet music) provided that the rightholders receives fair compensation;

- reproduction made by libraries, educational establishments, museums or archives, which are non-commercial;

- archival reproductions of broadcasts;

- uses for the benefit of people with a disability;

- for demonstration or repair of equipment;

- for non-commercial research or private study;

- when used in parody.

Accessible copies

It is legal in several countries including the United Kingdom and the United States to produce alternative versions (for example, in large print or braille) of a copyrighted work to provide improved access to a work for blind and visually impaired people without permission from the copyright holder.[75][76]

Religious Service Exemption

In the US there is a Religious Service Exemption (1976 law, section 110[3]), namely «performance of a non-dramatic literary or musical work or of a dramatico-musical work of a religious nature or display of a work, in the course of services at a place of worship or other religious assembly» shall not constitute infringement of copyright.[77]

Transfer, assignment and licensing

A copyright, or aspects of it (e.g. reproduction alone, all but moral rights), may be assigned or transferred from one party to another.[78] For example, a musician who records an album will often sign an agreement with a record company in which the musician agrees to transfer all copyright in the recordings in exchange for royalties and other considerations. The creator (and original copyright holder) benefits, or expects to, from production and marketing capabilities far beyond those of the author. In the digital age of music, music may be copied and distributed at minimal cost through the Internet; however, the record industry attempts to provide promotion and marketing for the artist and their work so it can reach a much larger audience. A copyright holder need not transfer all rights completely, though many publishers will insist. Some of the rights may be transferred, or else the copyright holder may grant another party a non-exclusive license to copy or distribute the work in a particular region or for a specified period of time.

A transfer or licence may have to meet particular formal requirements in order to be effective,[79] for example under the Australian Copyright Act 1968 the copyright itself must be expressly transferred in writing. Under the US Copyright Act, a transfer of ownership in copyright must be memorialized in a writing signed by the transferor. For that purpose, ownership in copyright includes exclusive licenses of rights. Thus exclusive licenses, to be effective, must be granted in a written instrument signed by the grantor. No special form of transfer or grant is required. A simple document that identifies the work involved and the rights being granted is sufficient. Non-exclusive grants (often called non-exclusive licenses) need not be in writing under US law. They can be oral or even implied by the behavior of the parties. Transfers of copyright ownership, including exclusive licenses, may and should be recorded in the U.S. Copyright Office. (Information on recording transfers is available on the Office’s web site.) While recording is not required to make the grant effective, it offers important benefits, much like those obtained by recording a deed in a real estate transaction.

Copyright may also be licensed.[78] Some jurisdictions may provide that certain classes of copyrighted works be made available under a prescribed statutory license (e.g. musical works in the United States used for radio broadcast or performance). This is also called a compulsory license, because under this scheme, anyone who wishes to copy a covered work does not need the permission of the copyright holder, but instead merely files the proper notice and pays a set fee established by statute (or by an agency decision under statutory guidance) for every copy made.[80] Failure to follow the proper procedures would place the copier at risk of an infringement suit. Because of the difficulty of following every individual work, copyright collectives or collecting societies and performing rights organizations (such as ASCAP, BMI, and SESAC) have been formed to collect royalties for hundreds (thousands and more) works at once. Though this market solution bypasses the statutory license, the availability of the statutory fee still helps dictate the price per work collective rights organizations charge, driving it down to what avoidance of procedural hassle would justify.

Free licenses

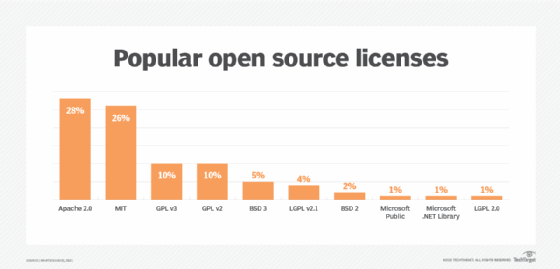

Copyright licenses known as open or free licenses seek to grant several rights to licensees, either for a fee or not. Free in this context is not as much of a reference to price as it is to freedom. What constitutes free licensing has been characterised in a number of similar definitions, including by order of longevity the Free Software Definition, the Debian Free Software Guidelines, the Open Source Definition and the Definition of Free Cultural Works. Further refinements to these definitions have resulted in categories such as copyleft and permissive. Common examples of free licences are the GNU General Public License, BSD licenses and some Creative Commons licenses.

Founded in 2001 by James Boyle, Lawrence Lessig, and Hal Abelson, the Creative Commons (CC) is a non-profit organization[81] which aims to facilitate the legal sharing of creative works. To this end, the organization provides a number of generic copyright license options to the public, gratis. These licenses allow copyright holders to define conditions under which others may use a work and to specify what types of use are acceptable.[81]

Terms of use have traditionally been negotiated on an individual basis between copyright holder and potential licensee. Therefore, a general CC license outlining which rights the copyright holder is willing to waive enables the general public to use such works more freely. Six general types of CC licenses are available (although some of them are not properly free per the above definitions and per Creative Commons’ own advice). These are based upon copyright-holder stipulations such as whether they are willing to allow modifications to the work, whether they permit the creation of derivative works and whether they are willing to permit commercial use of the work.[82] As of 2009 approximately 130 million individuals had received such licenses.[82]

Criticism

Some sources are critical of particular aspects of the copyright system. This is known as a debate over copynorms. Particularly to the background of uploading content to internet platforms and the digital exchange of original work, there is discussion about the copyright aspects of downloading and streaming, the copyright aspects of hyperlinking and framing.

Concerns are often couched in the language of digital rights, digital freedom, database rights, open data or censorship.[83][84][85] Discussions include Free Culture, a 2004 book by Lawrence Lessig. Lessig coined the term permission culture to describe a worst-case system. Good Copy Bad Copy (documentary) and RiP!: A Remix Manifesto, discuss copyright. Some suggest an alternative compensation system. In Europe consumers are acting up against the raising costs of music, film and books, and as a result Pirate Parties have been created. Some groups reject copyright altogether, taking an anti-copyright stance. The perceived inability to enforce copyright online leads some to advocate ignoring legal statutes when on the web.

Public domain

Copyright, like other intellectual property rights, is subject to a statutorily determined term. Once the term of a copyright has expired, the formerly copyrighted work enters the public domain and may be used or exploited by anyone without obtaining permission, and normally without payment. However, in paying public domain regimes the user may still have to pay royalties to the state or to an authors’ association. Courts in common law countries, such as the United States and the United Kingdom, have rejected the doctrine of a common law copyright. Public domain works should not be confused with works that are publicly available. Works posted in the internet, for example, are publicly available, but are not generally in the public domain. Copying such works may therefore violate the author’s copyright.

See also

- Adelphi Charter

- Artificial scarcity

- Authors’ rights and related rights, roughly equivalent concepts in civil law countries

- Conflict of laws

- Copyfraud

- Copyleft

- Copyright abolition

- Copyright Alliance

- Copyright alternatives

- Copyright for Creativity

- Copyright in architecture in the United States

- Copyright on the content of patents and in the context of patent prosecution

- Criticism of copyright

- Criticism of intellectual property

- Directive on Copyright in the Digital Single Market (European Union)

- Copyright infringement

- Copyright on religious works

- Copyright Remedy Clarification Act (CRCA)

- Digital rights management

- Digital watermarking

- Entertainment law

- Freedom of panorama

- Information literacies

- Intellectual property protection of typefaces

- List of Copyright Acts

- List of copyright case law

- Literary property

- Model release

- Paracopyright

- Philosophy of copyright

- Photography and the law

- Pirate Party

- Printing patent, a precursor to copyright

- Private copying levy

- Production music

- Rent-seeking

- Reproduction fees

- Samizdat

- Software copyright

- Threshold pledge system

- World Book and Copyright Day

References

- ^ «Definition of copyright». Oxford Dictionaries. Archived from the original on 29 September 2016. Retrieved 20 December 2018.

- ^ «Definition of Copyright». Merriam-Webster. Retrieved 20 December 2018.

- ^ Nimmer on Copyright, vol. 2, § 8.01.

- ^ «Intellectual property», Black’s Law Dictionary, 10th ed. (2014).

- ^ a b «Understanding Copyright and Related Rights» (PDF). www.wipo.int. p. 4. Retrieved 6 December 2018.

- ^ Stim, Rich (27 March 2013). «Copyright Basics FAQ». The Center for Internet and Society Fair Use Project. Stanford University. Retrieved 21 July 2019.

- ^ Daniel A. Tysver. «Works Unprotected by Copyright Law». Bitlaw.

- ^ Lee A. Hollaar. «Legal Protection of Digital Information». p. Chapter 1: An Overview of Copyright, Section II.E. Ideas Versus Expression.

- ^ Copyright, University of California, 2014, retrieved 15 December 2014

- ^ «Journal Conventions». Vanderbilt Journal of Entertainment & Technology Law. Archived from the original on 13 March 2014. Retrieved 7 November 2022.

- ^ Blackshaw, Ian S. (20 October 2011). Sports Marketing Agreements: Legal, Fiscal and Practical Aspects. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 9789067047937 – via Google Books.

- ^ Kaufman, Roy (16 July 2008). Publishing Forms and Contracts. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780190451264 – via Google Books.

- ^ Ahmad, Tabrez; Snehil, Soumya (2011). «Significance of Fixation in Copyright Law». SSRN. SSRN 1839527. Archived from the original on 3 June 2018. Retrieved 7 November 2022.

- ^ «Copyright Basics» (PDF). www.copyright.gov. U.S. Copyright Office. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 20 February 2019.

- ^ «International Copyright Law Survey». Mincov Law Corporation.

- ^ a b c Copyright in Historical Perspective, p. 136-137, Patterson, 1968, Vanderbilt Univ. Press

- ^ Joanna Kostylo, «From Gunpowder to Print: The Common Origins of Copyright and Patent», in Ronan Deazley et al., Privilege and Property: Essays on the History of Copyright (Cambridge: Open Book, 2010), 21-50; online at books.openedition.org/obp/1062

- ^ a b c d Thadeusz, Frank (18 August 2010). «No Copyright Law: The Real Reason for Germany’s Industrial Expansion?». Spiegel Online.

- ^ Lasar, Matthew (23 August 2010). «Did Weak Copyright Laws Help Germany Outpace The British Empire?». Wired.

- ^ Nipps, Karen (2014). «Cum privilegio: Licensing of the Press Act of 1662″ (PDF). The Library Quarterly. 84 (4): 494–500. doi:10.1086/677787. S2CID 144070638. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022.

- ^ a b c Day O’Connor, Sandra (2002). «Copyright Law from an American Perspective». Irish Jurist. 37: 16–22. JSTOR 44027015.

- ^ Bettig, Ronald V. (1996). Copyrighting Culture: The Political Economy of Intellectual Property. Westview Press. p. 9–17. ISBN 0-8133-1385-6.

- ^ Ronan, Deazley (2006). Rethinking copyright: history, theory, language. Edward Elgar Publishing. p. 13. ISBN 978-1-84542-282-0 – via Google Books.

- ^ «Statute of Anne». Copyrighthistory.com. Retrieved 8 June 2012.

- ^ Frank Thadeusz (18 August 2010). «No Copyright Law: The Real Reason for Germany’s Industrial Expansion?». Der Spiegel. Retrieved 11 April 2015.

- ^ Giorcelli, Michela; Moser, Petra (March 2020). «Copyright and Creativity. Evidence from Italian Opera During the Napoleonic Age». National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper Series. doi:10.3386/w26885.

- ^ a b «Berne Convention for the Protection of Literary and Artistic Works Article 5». World Intellectual Property Organization. Archived from the original on 11 September 2012. Retrieved 18 November 2011.

- ^ Garfinkle, Ann M; Fries, Janet; Lopez, Daniel; Possessky, Laura (1997). «Art conservation and the legal obligation to preserve artistic intent». JAIC 36 (2): 165–179.

- ^ «International Copyright Relations of the United States», U.S. Copyright Office Circular No. 38a, August 2003.

- ^ Parties to the Geneva Act of the Universal Copyright Convention Archived 25 June 2008 at the Wayback Machine as of 1 January 2000: the dates given in the document are dates of ratification, not dates of coming into force. The Geneva Act came into force on 16 September 1955, for the first twelve to have ratified (which included four non-members of the Berne Union as required by Art. 9.1), or three months after ratification for other countries.

- ^ 165 Parties to the Berne Convention for the Protection of Literary and Artistic Works Archived 6 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine as of May 2012.

- ^ MacQueen, Hector L; Charlotte Waelde; Graeme T Laurie (2007). Contemporary Intellectual Property: Law and Policy. Oxford University Press. p. 39. ISBN 978-0-19-926339-4 – via Google Books.

- ^ 17 U.S.C. § 201(b); Cmty. for Creative Non-Violence v. Reid, 490 U.S. 730 (1989)

- ^ Community for Creative Non-Violence v. Reid

- ^ Stim, Rich (27 March 2013). «Copyright Ownership: Who Owns What?». The Center for Internet and Society Fair Use Project. Stanford University. Retrieved 21 July 2019.

- ^ a b c

Yu, Peter K, ed. (30 December 2006). Intellectual property and information wealth: copyright and related rights. Westport, Connecticut, USA: Praeger. ISBN 978-0-275-98882-1. Praeger is part of the Greenwood Publishing Group. Hardcover. Possible alternative ISBN 978-0-275-98883-8. - ^ World Intellectual Property Organization (2016). Understanding Copyright and Related Rights (PDF). WIPO. p. 8. doi:10.34667/tind.36289. ISBN 9789280528046. Retrieved 1 December 2017.

- ^ a b Simon, Stokes (2001). Art and copyright. Hart Publishing. pp. 48–49. ISBN 978-1-84113-225-9 – via Google Books.

- ^ Express Newspaper Plc v News (UK) Plc, F.S.R. 36 (1991)

- ^ «Subject Matter and Scope of Copyright» (PDF). copyright.gov. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 4 June 2015.

- ^ «Copyright in General (FAQ)». U.S. Copyright Office. Retrieved 11 August 2016.

- ^ «Copyright Registers» Archived 5 October 2013 at the Wayback Machine, United Kingdom Intellectual Property Office

- ^ «Automatic right», United Kingdom Intellectual Property Office

- ^ a b See Harvard Law School, Module 3: The Scope of Copyright Law. See also Tyler T. Ochoa, Copyright, Derivative Works and Fixation: Is Galoob a Mirage, or Does the Form(GEN) of the Alleged Derivative Work Matter?, 20 Santa Clara High Tech. L.J. 991, 999–1002 (2003) («Thus, both the text of the Act and its legislative history demonstrate that Congress intended that a derivative work does not need to be fixed in order to infringe.»). The legislative history of the 1976 Copyright Act says this difference was intended to address transitory works such as ballets, pantomimes, improvised performances, dumb shows, mime performances, and dancing.

- ^ See US copyright law

- ^ Pub. L. 94–553: Copyright Act of 1976, 90 Stat. 2541, § 401(a) (19 October 1976)

- ^ Pub. L. 100–568: The Berne Convention Implementation Act of 1988 (BCIA), 102 Stat. 2853, 2857. One of the changes introduced by the BCIA was to section 401, which governs copyright notices on published copies, specifying that notices «may be placed on» such copies; prior to the BCIA, the statute read that notices «shall be placed on all» such copies. An analogous change was made in section 402, dealing with copyright notices on phonorecords.

- ^ Taylor, Astra (2014). The People’s Platform:Taking Back Power and Culture in the Digital Age. New York City, New York, USA: Picador. pp. 144–145. ISBN 978-1-250-06259-8.

- ^ «U.S. Copyright Office – Information Circular» (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 7 July 2012.

- ^ 17 U.S.C.§ 401(d)

- ^ Taylor, Astra (2014). The People’s Platform: Taking Back Power and Culture in the Digital Age. New York, New York: Picador. p. 148. ISBN 978-1-250-06259-8.

- ^ Owen, L. (2001). «Piracy». Learned Publishing. 14: 67–70. doi:10.1087/09531510125100313. S2CID 221957508.

- ^ Butler, S. Piracy Losses «Billboard» 199(36)

- ^ «Urheberrechtsverletzungen im Internet: Der bestehende rechtliche Rahmen genügt». Ejpd.admin.ch. Archived from the original on 19 August 2014. Retrieved 28 July 2020.

- ^ Tobias Kretschmer; Christian Peukert (2014). «Video Killed the Radio Star? Online Music Videos and Digital Music Sales». Cep Discussion Paper. Social Science Electronic Publishing. ISSN 2042-2695. SSRN 2425386.

- ^ «IP Commission Report» (PDF). NBR.org. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 1 September 2021.

- ^ «Impacts of Digital Piracy on the U.S. Economy» (PDF). GlobalInnovationPolicyCenter.com. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 2 September 2021.

- ^ «Advertising Fuels $1.34 Billion Illegal Piracy Market, Report by Digital Citizens Alliance and White Bullet Finds». Digital Citizens Alliance. Retrieved 2 September 2021.

- ^ a b c «World Intellectual Property Organisation (WIPO)» (PDF). 20 April 2019.

- ^ a b «THE MUTILATED WORK» (PDF). Copyright User. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022.

- ^ «authors, attribution, and integrity: examining moral rights in the united states» (PDF). U.S. Copyright Office. April 2019. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022.

- ^ Tom G. Palmer, «Are Patents and Copyrights Morally Justified?» Accessed 5 February 2013.

- ^ Dalmia, Vijay Pal (14 December 2017). «Copyright Law In India». Mondaq.

- ^ 17 U.S.C. § 305

- ^ The Duration of Copyright and Rights in Performances Regulations 1995, part II, Amendments of the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

- ^ Nimmer, David (2003). Copyright: Sacred Text, Technology, and the DMCA. Kluwer Law International. p. 63. ISBN 978-90-411-8876-2. OCLC 50606064 – via Google Books.

- ^ «Copyright Term and the Public Domain in the United States.», Cornell University.

- ^ See Peter B. Hirtle, «Copyright Term and the Public Domain in the United States 1 January 2015» online at footnote 8 Archived 26 February 2015 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Lawrence Lessig, Copyright’s First Amendment, 48 UCLA L. Rev. 1057, 1065 (2001)

- ^ «(2012) Copyright Protection Not Available for Names, Titles, or Short Phrases U.S. Copyright Office» (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022.

- ^ «John Wiley & Sons Inc. v. Kirtsaeng» (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 July 2017.

- ^ «US CODE: Title 17,107. Limitations on exclusive rights: Fair use». .law.cornell.edu. 20 May 2009. Retrieved 16 June 2009.

- ^ «The Digital Millennium Copyright Act of 1998» (PDF). Copyright Office. December 1998. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 October 2003. Retrieved 7 November 2022.

- ^ «Digital Millennium Copyright act». American Library Association. Archived from the original on 19 March 2012. Retrieved 7 November 2022.

- ^ «Chapter 1 – Circular 92 – U.S. Copyright Office». www.copyright.gov.

- ^ «Copyright (Visually Impaired Persons) Act 2002 comes into force». Royal National Institute of Blind People. 1 January 2011. Retrieved 11 August 2016.

- ^ General Guide to the Copyright Act of 1976, US Copyright Office, Ch.8, p.11, September 1977

- ^ a b WIPO Guide on the Licensing of Copyright and Related Rights. World Intellectual Property Organization. 2004. p. 15. ISBN 978-92-805-1271-7.

- ^ WIPO Guide on the Licensing of Copyright and Related Rights. World Intellectual Property Organization. 2004. p. 8. ISBN 978-92-805-1271-7.

- ^ WIPO Guide on the Licensing of Copyright and Related Rights. World Intellectual Property Organization. 2004. p. 16. ISBN 978-92-805-1271-7.

- ^ a b «Creative Commons Website». creativecommons.org. Retrieved 24 October 2011.

- ^ a b Rubin, R. E. (2010) ‘Foundations of Library and Information Science: Third Edition’, Neal-Schuman Publishers, Inc., New York, p. 341

- ^ «MEPs ignore expert advice and vote for mass internet censorship». European Digital Rights. 20 June 2018. Retrieved 24 June 2018.

- ^ «Copyright Week 2019: Copyright as a tool of censorship». European Digital Rights (EDRi). Retrieved 27 February 2021.

- ^ «Revealed: How copyright law is being misused to remove material from the internet». The Guardian. 23 May 2016. Retrieved 27 February 2021.

Further reading

- Dowd, Raymond J. (2006). Copyright Litigation Handbook (1st ed.). Thomson West. ISBN 0-314-96279-4.

- Ellis, Sara R. Copyrighting Couture: An Examination of Fashion Design Protection and Why the DPPA and IDPPPA are a Step Towards the Solution to Counterfeit Chic, 78 Tenn. L. Rev. 163 (2010), available at Copyrighting Couture: An Examination of Fashion Design Protection and Why the DPPA and IDPPPA are a Step Towards the Solution to Counterfeit Chic.

- Ghosemajumder, Shuman. Advanced Peer-Based Technology Business Models. MIT Sloan School of Management, 2002.

- Lehman, Bruce: Intellectual Property and the National Information Infrastructure (Report of the Working Group on Intellectual Property Rights, 1995)

- Lindsey, Marc: Copyright Law on Campus. Washington State University Press, 2003. ISBN 978-0-87422-264-7.

- Mazzone, Jason. Copyfraud. SSRN

- McDonagh, Luke. Is Creative use of Musical Works without a licence acceptable under Copyright? International Review of Intellectual Property and Competition Law (IIC) 4 (2012) 401–426, available at SSRN

- Nimmer, Melville; David Nimmer (1997). Nimmer on Copyright. Matthew Bender. ISBN 0-8205-1465-9.

- Patterson, Lyman Ray (1968). Copyright in Historical Perspective. Online Version. Vanderbilt University Press. ISBN 0-8265-1373-5.

- Rife, by Martine Courant. Convention, Copyright, and Digital Writing (Southern Illinois University Press; 2013) 222 pages; Examines legal, pedagogical, and other aspects of online authorship.

- Rosen, Ronald (2008). Music and Copyright. Oxford Oxfordshire: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-533836-2.

- Shipley, David E. «Thin But Not Anorexic: Copyright Protection for Compilations and Other Fact Works» UGA Legal Studies Research Paper No. 08-001; Journal of Intellectual Property Law, Vol. 15, No. 1, 2007.

- Silverthorne, Sean. Music Downloads: Pirates- or Customers?. Harvard Business School Working Knowledge, 2004.

- Sorce Keller, Marcello. «Originality, Authenticity and Copyright», Sonus, VII(2007), no. 2, pp. 77–85.

- Steinberg, S.H.; Trevitt, John (1996). Five Hundred Years of Printing (4th ed.). London and New Castle: The British Library and Oak Knoll Press. ISBN 1-884718-19-1.

- Story, Alan; Darch, Colin; Halbert, Deborah, eds. (2006). The Copy/South Dossier: Issues in the Economics, Politics and Ideology of Copyright in the Global South (PDF). Copy/South Research Group. ISBN 978-0-9553140-1-8. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 August 2013.

- Ransom, Harry Huntt (1956). The First Copyright Statute. Austin: University of Texas. ISBN 9780292732353.

- Rose, M. (1993), Authors and Owners: The Invention of Copyright, London: Harvard University Press

- Loewenstein, J. (2002), The Author’s Due: Printing and the Prehistory of Copyright, London: University of Chicago Press.

- Abbott, Madigan, Mossoff, Osenga, Rosen. «Holding States Accountable for Copyright Piracy» (PDF). Regulatory Transparency Project. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 15 May 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

External links

Wikimedia Commons has media related to Copyright.

Wikiquote has quotations related to Copyright.

Wikisource has original text related to this article:

- Moraes, Frank (2 October 2020). «Copyright Law In 2020 Explained In One Page». WhoIsHostingThis.com. A simplified guide.

- Copyright at Curlie

- WIPOLex from WIPO; global database of treaties and statutes relating to intellectual property

- Copyright Berne Convention: Country List List of the 164 members of the Berne Convention for the protection of literary and artistic works

- Copyright and State Sovereign Immunity, U.S. Copyright Office

- The Multi-Billion-Dollar Piracy Industry with Tom Galvin of Digital Citizens Alliance, The Illusion of More Podcast

- Education

- Copyright Cortex

- A Bibliography on the Origins of Copyright and Droit d’Auteur

- MIT OpenCourseWare 6.912 Introduction to Copyright Law Free self-study course with video lectures as offered during the January 2006, Independent Activities Period (IAP)

- USA

- Copyright Law of the United States Documents, US Government

- Compendium of Copyright Practices (3rd ed.) United States Copyright Office

- Copyright from UCB Libraries GovPubs

- Early Copyright Records From the Rare Book and Special Collections Division at the Library of Congress

- UK

- Copyright: Detailed information at the UK Intellectual Property Office

- Fact sheet P-01: UK copyright law (Issued April 2000, amended 25 November 2020) at the UK Copyright Service

Updated: 10/11/2021 by

A Copyright is a protection for any published work that helps to prevent that work from being used without prior authorization. A Copyright may be indicated by the word «Copyright,» or a C surrounded by a circle (©). The Copyright might also be followed by the published date and the author of the work.

When work is Copyrighted, it may not be reproduced in any fashion unless the owner of the work grants proper rights. Computer Hope is not meant for legal representation, and how a Copyright is interpreted could vary. If you have additional questions or concerns about legalities, consult a legal consultant or attorney.

Example of a Copyright

Copyright © 2023 Computer Hope

A Copyright for Computer Hope is at the bottom of each of our pages.

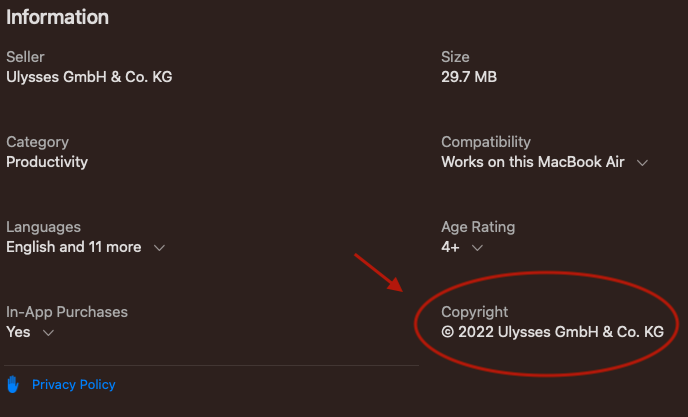

Software Copyright

Like any original work, software is also protected by Copyright laws. Copying or installing software you have not purchased is a breach of Copyright and a criminal offense. All software you use should be fully licensed for each computer and user using the program.

Should the word «Copyright» always be capitalized?

Yes.

Is a Copyright the same as a trademark?

No. A Copyright is a protection of intellectual property. A trademark is a protection of a brand, logo, motto, or another identifier. For example, the content on this page is Copyrighted and the company that owns the content, «Computer Hope,» is trademarked.

What is Copyright infringement?

Copyright infringement is any duplication, reproduction, or otherwise copied use or distribution of any Copyrighted material without the expressed permission of the Copyright holder. For example, downloading any MP3 music without paying for it or using it in a video without the owner’s consent is Copyright infringement.

Computer-related Copyright history

On June 17, 1980, Atari became the first company to register a Copyright for two computer games: «Asteroids» and «Lunar Landar.»

Business terms, Chilling effect, Cite, Copyleft, Creative commons, DMCA, DRM, Fair use, Footer, Freeware, License agreement, Orphan work, Patent, Plagiarism, Public domain, Watermark

Copyright law automatically protects your original materials and helps prevent theft and other unauthorized uses. But posting a copyright disclaimer on your website or app informs users that you know the law and retain certain rights over your content.

Continue reading to learn more about copyright notices and why you might need to post one on your website or app. Then, we’ll look at real-life copyright examples and teach you how to write your own copyright notice.

- What Is a Copyright?

- Copyright Examples & Types

- Do You Need a Copyright Notice?

- Benefits of a Copyright

- How To Write a Copyright Notice

- How and Where To Display a Copyright Notice

- Copyright Notice Examples

- Copyright FAQ

- Summary

What Is a Copyright?

A copyright is the exclusive legal right over how original content or materials you’ve made get copied, shared, reproduced, printed, performed, or published by others.

In other words, copyright provides you with exclusive rights to:

- Reproduce your work

- Distribute or sell your work

- Display or perform your work publicly

- Create derivative works based on the original work

It also allows you to authorize or restrict others in exercising these rights, further protecting your original works if they’re ever stolen or plagiarized.

A copyright usually consists of the following four components, which we’ll discuss in more detail later in the article:

- Copyright symbol © or the word “copyright”

- Year the material was published

- Name of the copyright owner

- What rights are retained by the copyright

Some examples of copyrighted works include:

- Art

- Literature

- Videos

- Images

- Photography

- Choreography

- Music

- Sound clips

Copyright Laws Around the World

Copyright laws vary around the world, and there is no global version of copyright, but many countries are part of the Berne Convention, which deals with protecting original works and the authors’ rights over them.

Established in 1886, countries under this convention agree to recognize a set of legal principles for protecting original content across country borders.

However, there are subtle differences in how copyright law works in each location, so we’ll briefly touch upon the relevant laws in the following countries, all of which are part of the Berne Convention:

- The United States

- The United Kingdom

- The European Union (EU)

- Australia

- Canada

Copyright in the US

In the US, your original materials are protected by copyright law as soon as you create something and release it publicly, even if you don’t post a copyright notice.

But if you want to ensure further protection of your works and potentially limit paying costly legal fees down the road, adding a copyright notice to your content may help deter:

- Copyright infringement

- Unauthorized reproduction, distribution, or displaying of copyrighted materials

You may also choose to register your copyright with the US Copyright Office.

Copyright in the UK

Copyright laws in the UK protect your original materials automatically. You do not have to apply for protection, register your work, or pay any fees for the law to protect your original creations, including:

- Literary works

- Dramatic works

- Music

- Works of art

Copyright in the EU

In the EU, copyright applies to your intellectual property until 70 years after your death or 70 years after the death of the last surviving author in cases of joint authorship.

But in the EU, there is no equivalent “fair use” doctrine, like in the US. Instead, there is a list of explicit exceptions that cover specific scopes.

Copyright in Australia

Like in the US, UK, and EU, Australia’s copyright law protects your creative works the moment you put your creative idea on paper, online, or any other form of documentation.

You do not need to register your work, as the protection is free and automatic under Australia’s Copyright Act 1968.

Copyright in Canada

As of 2022, copyright in Canada applies to your work automatically and lasts the author’s lifetime plus 70 years past their death.

Previously, the protection only lasted for 50 years past the author’s death.

What Is the Difference Between a Copyright and a Trademark?

The difference between a copyright and a trademark is the type of content each notice protects — trademarks apply to logos, slogans, and brand identity. In contrast, copyright applies to original tangible materials and creative works.

You technically own a trademark as soon as you start using a name or brand identity along with your goods or service, making it similar to how copyright law works.

While you’re not legally required to register your trademark with the United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO), doing so gives you broader rights and protections than when left unregistered.

For example, registering your trademark in the US grants you national recognition and creates nationwide rights.

Once registered, you can use the trademark symbol, which looks like an R with a circle around it: ®

But if your trademark is unregistered, you must use the abbreviation ‘TM’. However, if you’re trademarking a service, you may also use the initials’ SM’, meaning service mark, but both are still referred to as trademarks.

You can use the logo or abbreviations whenever you use your trademarked identity, as shown in the example screenshot below from the official International Olympics website.

However, if you prefer, you may also format it as superscript or subscript text.

Copyright Examples & Types

There are technically two types of copyright examples, one allows you to reuse copyrighted materials in specific ways for “fair use” purposes without the owners’ permission, and the other protects your content from reuse or reproduction as the owner of the work.

Let’s go over each type of copyright example in a little more detail in the following sections.

Copyrighting Works of Creative Expression

According to the US Copyright Office, copyright applies to all original works of creative expression captured in a tangible form and goes to the work’s original creator, who can choose to sell their rights to other parties.

Some examples of works that can be copyrighted include:

- Architectural works

- Sound recordings

- Audiovisual works — including motion pictures

- Artworks

- Dramatic works — including any accompanying music

- Musical works — including any accompanying words

- Literary works

- Choreographic works

That said, there are limitations to the types of work this protection applies to.

The following examples of content aren’t protected by copyright:

- Ideas, methods, systems, concepts, or discoveries

- Works that don’t have a tangible form (i.e., not captured in a physical medium)

- Titles, names, slogans

- Familiar symbols or designs

- Variations of typefaces or lettering

- Ingredient lists

“Fair Use” and Section 107 of the Copyright Act

You are allowed to legally reproduce or reuse certain aspects of a copyrighted work without the owners’ explicit permission for the following reasons, which qualify as “fair use” under section 107 of the Copyright Act:

- Commentary — i.e., copying paragraphs from a news article, scientific paper, or medical journal for educational purposes

- Criticism — i.e., quoting song lyrics or summarizing movie scenes for a critical review

- Parody — i.e., mimicking, making light of, or satirizing something in a comedic way

If you’re using someone else’s content for “fair use” purposes, it’s in your best interest to post a copyright disclaimer or a fair use disclaimer stating as much to help prevent an unfair or unnecessary copyright strike.

However, a disclaimer cannot guarantee that you won’t receive an unfair strike.

For this reason, we recommend getting explicit permission from the copyright owner to use their materials whenever possible.

While “fair use” copyrights are essential in many cases, the focus of this guide is primarily on the copyright that applies to protecting your usage rights over original content.

Do You Need a Copyright Notice?

While you don’t legally need a copyright notice for the law to cover your original works, it’s a best practice to put a disclaimer on all your published materials for the following reasons:

- Reason #1: Having a copyright notice posted on your website or app helps add an extra layer of protection if infringement does occur because you can prove that the infringer should’ve seen the copyright and been aware that your content was protected

- Reason #2: Copyright notices are very quick and easy to make and typically consist of four concise components

- Reason #3: Including one acts as a visual reminder to your users that your work is protected by copyright, and users may assume otherwise if they do not see a notice