-

#1

Hallo,

which is the correct abbreviation of «number»?

N.

N°.

Nr.

Thanks

Fede

-

#2

No.

that is how we do it in the UK.

-

#3

And in Oz, too.

»No. 2 Is up next»

Not sure if it’s universal but you can also use the symbol #

-

#4

Thank you both Sally and Sazza for the quick answer.

Sazza, what’s Oz?

Fede

-

#6

Hello and welcome, Fede F

You will find that different countries, and indeed different organisations, have different abbreviations.

No

No.

no

no.

… are commonly used — based on the Latin numero (from numerus, number).

In AE, # is often used and so is often found in places where AE-speak is understood. Members here would refer to post #23 for example.

-

#7

Hi all,

Is it correct to say “Nbr. of projects”, or “Nbr. of problems”?

If not, which would be the right way to write «the contraction of the word number”?

Thanks much!

-

#8

I’ve never seen «Nbr.» be used. The correct abbreviation for number is «No.»

-

#9

Thanks much edval89

-

#10

The abbreviation «No.» is used only in front of an actual number, e.g.,

No.5

Paragraph No.7

Husband No. 2

If you are using the word «number» as a regular noun, it cannot be abbreviated.

The number of projects…

A large number of problems…

-

#11

Idialegre, Then Ican not be write:

No. of projects, No. of problems, etc?? :O

-

#12

Yes you can, depending on the type of document. I wouldn’t suggest you use abbreviations in formal writings, but in tables, graphs, etc., abbreviations are acceptable.

-

#13

ok, thanks to you all, I got now the idea.

-

#14

Has anyone ever seen it abbreviated this way

«Nbr.«?

Thanks!

-

#15

Has anyone ever seen it abbreviated this way

«Nbr.«?

Thanks!

No, not until I read this post!

-

#16

Hello and welcome, Fede F

You will find that different countries, and indeed different organisations, have different abbreviations.

No

No.

no

no.

… are commonly used — based on the Latin numero (from numerus, number).In AE, # is often used and so is often found in places where AE-speak is understood. Members here would refer to post #23 for example.

Panjandrum, does that mean that «#» is not a common symbol for number in the British isles? (and yes, «No. 5» would be readily understood to mean «Number 5» in the US)

-

#17

I have seen both «Nbr.» and «Nr.» used, both only very rarely.

-

#18

Panjandrum, does that mean that «#» is not a common symbol for number in the British isles? (and yes, «No. 5» would be readily understood to mean «Number 5» in the US)

In many UK contexts #, meaning number, would have to be explained. Those of us more exposed to US culture — either comic strips or IT manuals — have come to understand the US #, and it also seems to pass without comment in this forum.

-

#19

In many UK contexts #, meaning number, would have to be explained. Those of us more exposed to US culture — either comic strips or IT manuals — have come to understand the US #, and it also seems to pass without comment in this forum.

Maybe because at least In Europe but I assume it is the case worldwide now that you use the # symbol when you have to enter a number on your mobile. Thus no doubt now everyone knows it means naturally number.

But only official abbreviation is no. (from Latin). <Moderator note: References to abbreviations in languages other than English have been removed. This English Only forum deals only with English usage.>

Last edited by a moderator: Sep 25, 2009

-

#20

I have seen both «Nbr.» and «Nr.» used, both only very rarely.

Yes, ‘Nbr’ or ‘Nr’ would just look ‘foreign’ (German, etc.).

N° would also be understood, but would also look ‘foreign’ (French, etc.).

-

#21

Maybe because at least In Europe but I assume it is the case worldwide now that you use the # symbol when you have to enter a number on your mobile. Thus no doubt now everyone knows it means naturally number.

The regular use of # for number in some BE contexts long precedes the introduction of mobile phones/ cell phones.

It’s rather an aside, but I never use the # key for this purpose on my phone.

But only official abbreviation is no. (from Latin). Others are just pure shortcuts, even though in Europe you see Nbr. or Nr. quite often I think (In French, we would still write Nbre for instance!)

There is no single official abbreviation. There are various conventions/standards.

-

#22

If you listen to automated instructions telling phone users what button to press you will often hear ‘that’ key called «the hash key» in the UK or «the pound key» in the US.

I would use «no.» as an abbreviation usually, but as Panj says, there isn’t a single convention. What I would advise is that, whichever convention you choose to use, you make sure you use it consistently.

-

#23

If you listen to automated instructions telling phone users what button to press you will often hear ‘that’ key called «the hash key» in the UK or «the pound key» in the US.

One of those little snippets of trivia that you’ll probably never need unless setting a wager in a pub is that the «#» is also called an octothorp — name coined by Bell Labs in the U.S. in 1973.

-

#24

Another thing about the # symbol, in some places it is referred to as ‘the number symbol’, ‘the pound key’ (when referencing a telephone key pad), or a ‘hash key’ (again, when referencing a telephone key pad).

In English Canada, # is far more common; but, N° is understood and seen often because it is preferred in French Canada.

Is there an alt-key short-cut for typing N°?

-

#25

A point that has not been touched upon here is whether the abbreviation «No.» should be capitalised:

My tax registration no. is xxx OR

My tax registration No. is xxx

To me the capitalised No. looks messy but some proofreaders seem to insist on it.

-

#26

A point that has not been touched upon here is whether the abbreviation «No.» should be capitalised:

My tax registration no. is xxx OR

My tax registration No. is xxxTo me the capitalised No. looks messy but some proofreaders seem to insist on it.

The abbreviation is not used in that context. It would have to be «My tax registration number is XXXX».

-

#27

I’m not sure about that. Obviously it’s just lazy and bad style to write, for example, «a no. of people attended», but in set expressions like telephone no., VAT no., serial no., etc. it is indeed used as an abbreviation in some styles (e.g. some legal docs and technical docs). And in those circumstances I would still be interested to hear some opinions about whether one would use «No.» or «no.» if found in the middle of a sentence.

-

#28

In the situations gls describes I would write No. or no. depending on whether I would write in full Number or number.

… Serial Number … -> … Serial No. …

… registration number … -> … registration no. …

-

#29

What is the abbreviation for «numbers»? For instance, I need to write «U.S. Pat. No. x,xxx,xxx; x,xxx,xxx; x,xxx,xxx». Should the abbreviation for «Numbers» be «No.» or «Nos.»?

-

#30

What is the abbreviation for «numbers»? For instance, I need to write «U.S. Pat. No. x,xxx,xxx; x,xxx,xxx; x,xxx,xxx». Should the abbreviation for «Numbers» be «No.» or «Nos.»?

In BrE we use Nos.

-

#31

From wikipedia:

In many parts of the world, including parts of Europe, Canada, Australia, and Russia,[citation needed] number sign refers instead to the «numero» sign № (Unicode code point U+2116), which is often written simply as No.

-

#32

Is there a space between the dot and the number itself?

E.g.

this brand holds the no.1 market position

or

this brand holds the no. 1 market position

Thanks

-

#33

I think it’s personal preference, but I wouldn’t put a space in between, simply to eliminate any doubt that there is a number missing in between, similar how you wouldn’t leave a space between a negative indicator and number : -5 ( as in negative 5).

-

#34

Also to add to this in case you think someone might confuse this for a decimal number, like 0.1 — there is not worry about it, since No. usually means that you are referring to a whole number. As in room No.23. But again I think it’s just a personal preference.

-

#35

In American English, # can stand either for «number» or «pound» (the unit of weight). Most commonly, it is the former meaning that is meant, except when referring to the # key on a telephone. In that case, you will find (at least in the USA) that automated voice menus accessed by telephones will sometimes direct you to «press the pound key,» though here it has nothing to do with weight. (I suspect the name for the key was chosen to avoid the inevitable confusion that «press the number key» would cause.)

Note that when abbreviating [No.], it is usually capitalized, since it is only used with a specific number, as mentioned in an earlier post; also, that the period should not be omitted, even informally (to avoid causing the reader to pause over the ambiguity with the word «no»).

-

#36

«N° would also be understood, but would also look ‘foreign’ (French, etc.).«

Is «N°» actually incorrect in English? Does anybody know?

Thanks,

Nicholas.

-

#37

I’ve never seen it before, and I wouldn’t know what it meant but for this thread. I don’t know if it’s incorrect, but it’s certainly not universally understood.

-

#38

Unlike those used in some other languages, American keyboards don’t include either a superior lower-case «o» (º) or «Nº» together as a single character. I don’t think keyboards for other English-speaking countries do either, even though there are some variations from the American keyboard (such as inclusion of «£»).

That suggests that «Nº» has never been used in English-speaking countries as an abbreviation for «Number» or anything else. I happen to know how to use an «º» in Windows but many Americans who know more about computers and data processing than I do not know how to do this, and in any case it requires extra keystrokes. It’s a lot like inverted question marks and exclamation points (¿¡), which English doesn’t use either.

Therefore, whether a particular reader whose native language is English will understand «Nº» to mean «number» is a chancy business. Those with extensive experience with the languages where it is used will recognize it, and some might figure it out from the context, but when writing in English it would be better to employ a more widely understood abbreviation, rather than to insist on one from one’s native language.

There seem to be some differences between British and American English in the most common abbrevation for «number,» as described earlier in this thread.

-

#39

Hi Pob14 and Fabulist,

Thanks both.

Yes, my UK keyboard doesn’t have one either, making º a rare chance to use «insert/symbol» in Word which breaks the tedium a bit!

I gather from your replies that it is probably correct to replace the exotic «N

º

» with a bog-standard «No.» in translating texts from other languages. No means no!

Nico.

-

#40

Is «N°» actually incorrect in English? Does anybody know?

Happy New Year, Nicholas/Nico!

As others have said, it is not common, but I wouldn’t say it is incorrect. It might suggest foreignness — or it might suggest old fashion. There was the tradition of raising the last letter of a contraction, as in this sign for Abbey Rd (note the raised, underscored D). I’ve also seen N

º

in this kind of context.

-

#41

To me, «No.» is most typical. «Nr.» is used by German speaking Dutch. Additional one not mentioend is «N

o

«, which was commonly used on printed forms in the old days for trades.

-

#42

<< …»N°. on the map.» or «No on map.» … >>

What is the best phrase in English ?

Last edited by a moderator: Nov 7, 2012

-

#43

The standard abbreviation of «number» is «No.»

p.s. Welcome to the forum SilviaVirus

-

#44

Please clarify the nature of your question, SilviaVirus.

And of course, Welcome to the Forum!

-

#45

Welcome, SilviaVirus. Not to anticipate your clarification, but just a general comment about No vs N°.

As No can easily be confused with the word «no», it’s generally best to include the stop: «No.» (even these days, when it’s acceptable to write many abbreviations without stops). The disadvantage with that is that the stop tends to break the sentence, as the eye may see it initially as a full stop after the word «No».

Personally I prefer N°, as it avoids all possible confusion.

Ws

-

#46

Is this about a phrase such as «The memorial is shown as No. 5 on the map?» In that case, the number after the abbreviation would clarify that «No» (if one does not use the period, BE stop or full stop) is short for «number,» not the word «no.» Still, this is a place where the U.S. practice of putting periods after all abbreviations can be helpful.

I’d consider the form with the little raised «o» to be archaic in English, though it’s still used in other languages. I might expect to see it in a nineteenth-century account book in an antique store, but not in anything written in the present century.

-

#47

I don’t think I’ve ever so much as seen it — except in one of those antique manuscripts. I guess I could figure out what it meant if it was followed by a number («N° 1″), but it would certainly make me look twice. I would not recommend it.

-

#48

I agree that ‘No.’ is the British abbreviation. I don’t remember ever encountering a situation where it could be confused with the word ‘no’. I would always include ‘.’

So: «No. on map.»

Last edited by a moderator: Nov 7, 2012

-

#49

Mod note: Silvia’s thread (post 42 onwards) has been merged with an earlier thread. Please read the earlier posts for more on the abbreviation for ‘number’.Welcome to the Forum, Silvia!

-

#50

[…] Personally I prefer N°, as it avoids all possible confusion. […]

Judging by the reactions of others, particularly AmE-speakers, it seems that «N°» isn’t universally accepted. Perhaps I’ve been influenced by my exposure to French usage.

I agree with Biffo that you’d be unlikely to confuse «No.» with the word «No» once you think about it. But I do occasionally experience a split-second hesitation when reading a sentence with «No.», particularly if there’s a space between it and the following number:

— «He said No. 13 is unlucky«.

Apparently I’m not entirely alone in that:

[…] also, that the period should not be omitted, even informally (to avoid causing the reader to pause over the ambiguity with the word «no»).

However the problem is considerably reduced by omitting the space.

— «He said No.13 is unlucky«.

Ws

Wiki User

∙ 7y ago

Want this question answered?

Be notified when an answer is posted

Study guides

Add your answer:

Earn +

20

pts

Q: What is the word contraction for the word number?

Write your answer…

Submit

Still have questions?

Related questions

People also asked

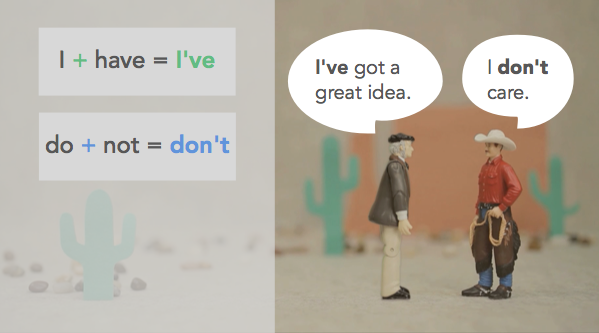

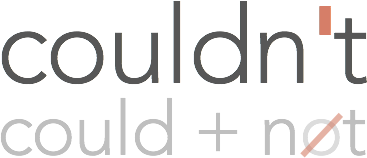

A contraction is a shortened version of the spoken and written forms of a word, syllable, or word group, created by omission of internal letters and sounds.

In linguistic analysis, contractions should not be confused with crasis, abbreviations and initialisms (including acronyms), with which they share some semantic and phonetic functions, though all three are connoted by the term «abbreviation» in layman’s terms.[1] Contraction is also distinguished from morphological clipping, where beginnings and endings are omitted.

The definition overlaps with the term portmanteau (a linguistic blend), but a distinction can be made between a portmanteau and a contraction by noting that contractions are formed from words that would otherwise appear together in sequence, such as do and not, whereas a portmanteau word is formed by combining two or more existing words that all relate to a singular concept that the portmanteau describes.

English[edit]

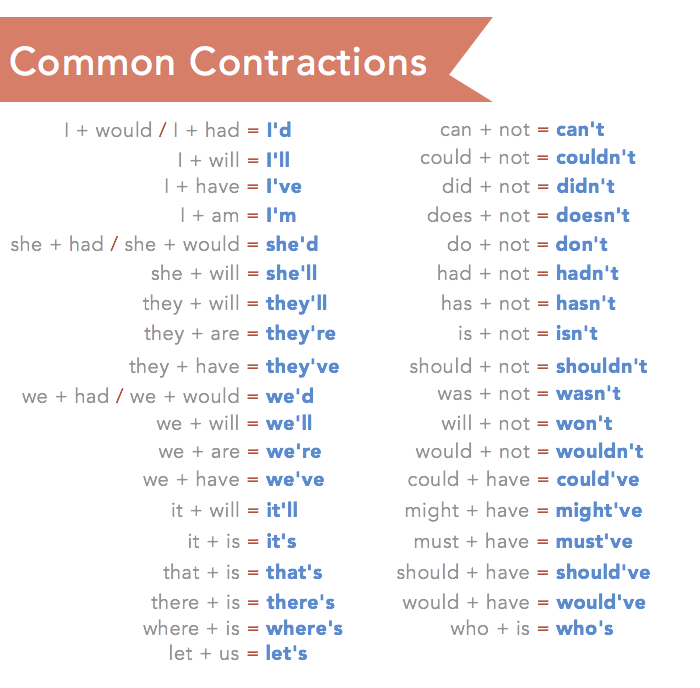

English has a number of contractions, mostly involving the elision of a vowel (which is replaced by an apostrophe in writing), as in I’m for «I am», and sometimes other changes as well, as in won’t for «will not» or ain’t for «am not». These contractions are common in speech and in informal writing, but tend to be avoided in more formal writing (with limited exceptions, such as the mandatory form of «o’clock»).

The main contractions are listed in the following table (for more explanation see English auxiliaries and contractions).

| Full form | Contracted | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| not | -n’t | informal; any auxiliary verb + not is often contracted, e.g. can’t, don’t, shan’t, shouldn’t, won’t, but not is rarely contracted with other parts of speech;

when a sentence beginning «I am not …» undergoes an interrogative inversion, contraction is to one of two irregular forms Aren’t I …? (standard) or Ain’t I …? (dialectical), both being far more common than uncontracted Am not I …? (rare and stilted) or Am I not …? |

| let us | let’s | informal, as in «Let’s do this.» |

| I am | I’m | informal, as in «I’m here.» |

| are | -‘re | informal; we’re /wɪər/ or /wɛər/ is, in most cases, pronounced differently from were /wɜr/. |

| does | -‘s | informal, as in «What’s he do there every day?» |

| is | informal, as in «He’s driving right now.» | |

| has | informal, as in «She’s been here before.» | |

| have | -‘ve | informal, as in «I’ve never done this before.» |

| had | -‘d | informal, e.g. «He’d already left.» or «We’d better go.» |

| did | informal, as in «Where’d she go?» | |

| would | informal, as in «We’d get in trouble if we broke the door.» | |

| will | -‘ll | informal, as in «they’ll call you later.» |

| shall | informal, as in «I’ll call you later.» | |

| of | o’- | standard in some fixed compounds,[Note 1] as in three o’clock, cat o’ nine tails, jack-o’-lantern, will-o’-wisp, man o’ war, run-o’-the-mill (but mother-o’-pearl is borderline); informal otherwise, as in «cup o’ coffee,» «barrel o’ monkeys,» «Land o’ Goshen» |

| of the | ||

| it was | ’twas | archaic, except in stock uses such as ‘Twas the night before Christmas |

| them | ’em | informal, partially from hem, the original dative and accusative of they[2][3] |

| you | y’- | 2nd person pronoun (you) has plurality marked in some varieties of English (e.g. Southern U.S.) by combining with e.g. all, which is then usually contracted to y’all — in which case it likely is standard[Note 2] |

| about | ’bout | ’bout is informal, e.g. I’ll come by ’bout noon. |

| because | ’cause | ’cause is very informal, e.g. Why did you do it? Just ’cause. |

Contraction is a type of elision, simplifying pronunciation through reducing (dropping or shortening) sounds occurring to a word group.

In subject–auxiliary inversion, the contracted negative forms behave as if they were auxiliaries themselves, changing place with the subject. For example, the interrogative form of He won’t go is Won’t he go?, whereas the uncontracted equivalent is Will he not go?, with not following the subject.

Chinese[edit]

The Old Chinese writing system (oracle bone script and bronzeware script) is well suited for the (almost) one-to-one correspondence between morpheme and glyph. Contractions, in which one glyph represents two or more morphemes, are a notable exception to this rule. About twenty or so are noted to exist by traditional philologists, and are known as jiāncí (兼詞, lit. ‘concurrent words’), while more words have been proposed to be contractions by recent scholars, based on recent reconstructions of Old Chinese phonology, epigraphic evidence, and syntactic considerations. For example, 非 [fēi] has been proposed to be a contraction of 不 (bù) + 唯/隹 (wéi/zhuī). These contractions are not generally graphically evident, nor is there a general rule for how a character representing a contraction might be formed. As a result, the identification of a character as a contraction, as well as the word(s) that are proposed to have been contracted, are sometimes disputed.

As vernacular Chinese dialects use sets of function words that differ considerably from Classical Chinese, almost all classical contractions listed below are now archaic and have disappeared from everyday use. However, modern contractions have evolved from these new vernacular function words. Modern contractions appear in all the major modern dialect groups. For example, 别 (bié) ‘don’t’ in Standard Mandarin is a contraction of 不要 (bùyào), while 覅 (fiào) ‘don’t’ in Shanghainese is a contraction of 勿要 (wù yào), as is apparent graphically. Similarly, in Northeast Mandarin 甭 (béng) ‘needn’t’ is both a phonological and graphical contraction of 不用 (bùyòng). Finally, Cantonese contracts 乜嘢 (mat1 ye5)[4] ‘what?’ to 咩 (me1).

- Table of Classical Chinese contractions

| Full form[5] | Transliteration[6] | Contraction[5] | Transliteration[6] | Notes[5] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 之乎 | tjə ga | 諸 | tjᴀ | In some rarer cases 諸 can also be contraction for 有之乎. 諸 can be used on its own with the meaning of «all, the class of», as in 諸侯 «the feudal lords.» |

| 若之何 | njᴀ tjə gaj | 奈何 | najs gaj | |

| [於之]note | ʔa tjə | 焉 | ʔrjan | 於之 is never used; only 焉. |

| 之焉 | tjə ʔrjan | 旃 | tjan | Rare. |

| [于之]note | wja tjə | 爰 | wjan | Rare. The prepositions 於, 于, and 乎 are of different origin, but used interchangeably (except that 乎 can also be used as a final question particle). |

| [如之]note | nja tjə | 然 | njan | |

| [曰之]note | wjot tjə | 云 | wjən | |

| 不之 | pjə tjə | 弗 | pjət | |

| 毋之 | mja tjə | 勿 | mjət | 弗 and 勿 were originally not contractions, but were reanalyzed as contractions in the Warring States period. |

| 而已 | njə ljəʔ | 耳 | njəʔ | |

| 胡不 | ga pjə | 盍 | gap | 胡 is a variant of 何. |

| 也乎 | ljᴀjʔ ga | 與 | ljaʔ | Also written 歟. |

| 也乎 | ljᴀjʔ ga | 邪 | zjᴀ | Also written 耶. Probably a dialectal variant of 與. |

| 不乎 | pjə ga | 夫 | pja | 夫 has many other meanings. |

Note: The particles 爰, 焉, 云, and 然 ending in [-j[a/ə]n] behave as the grammatical equivalents of a verb (or coverb) followed by 之 ‘him; her; it (third person object)’ or a similar demonstrative pronoun in the object position. In fact, 于/於 ‘(is) in; at’, 曰 ‘say’, and 如 ‘resemble’ are never followed by 之 ‘(third person object)’ or 此 ‘(near demonstrative)’ in pre-Qin texts. Instead, the respective ‘contractions’ 爰/焉, 云, and 然 are always used in their place. Nevertheless, no known object pronoun is phonologically appropriate to serve as the hypothetical pronoun that had undergone contraction. Hence, many authorities do not consider them to be true contractions. As an alternative explanation for their origin, Pulleyblank proposed that the [-n] ending is derived from a Sino-Tibetan aspect marker which later took on anaphoric character.[7]

Dutch[edit]

Some of the contractions in standard Dutch:

| Full form | Contracted | Translation | Note |

|---|---|---|---|

| des | ‘s | of | Genitive form of the Dutch article de «the» |

| een | ‘n | a, an | |

| haar | d’r | her | |

| hem | ‘m | him | |

| het | ‘t | it the |

|

| ik | ‘k | I | |

| mijn | m’n | my | |

| zijn | z’n | his | |

| zo een | zo’n | such a |

Informal Belgian Dutch utilizes a wide range of non-standard contractions, such as, for example, «hoe’s’t» (from «hoe is het?» — how are you?), «hij’s d’r» (from «hij is daar» — he’s there), «w’ebbe’ goe’ g’ete'» (from «we hebben goed gegeten» — we had eaten well) and «wa’s da’?» (from «wat is dat?» — what is that?. Some of these contractions:

| Full form | Contracted | Translation | Note |

|---|---|---|---|

| there | |||

| dat | da’ | that | |

| dat is | da’s | that is | |

| dat ik | da’k | that I | |

| ge | g’ | you | |

| is | ‘s | is | |

| wat | wa’ | what | |

| we | w’ | we | |

| ze | z’ | she |

French[edit]

The French language has a variety of contractions, similar to English but mandatory, as in C’est la vie («That’s life»), where c’est stands for ce + est («that is»). The formation of these contractions is called elision.

In general, any monosyllabic word ending in e caduc (schwa) will contract if the following word begins with a vowel, h or y (as h is silent and absorbed by the sound of the succeeding vowel; y sounds like i). In addition to ce → c’- (demonstrative pronoun «that»), these words are que → qu’- (conjunction, relative pronoun, or interrogative pronoun «that»), ne → n’- («not»), se → s’- («himself», «herself», «itself», «oneself» before a verb), je → j’- («I»), me → m’- («me» before a verb), te → t’- (informal singular «you» before a verb), le or la → l’- («the»; or «he», «she», «it» before a verb or after an imperative verb and before the word y or en), and de → d’- («of»). Unlike with English contractions, however, these contractions are mandatory: one would never say (or write) *ce est or *que elle.

Moi («me») and toi (informal «you») mandatorily contract to m’- and t’- respectively after an imperative verb and before the word y or en.

It is also mandatory to avoid the repetition of a sound when the conjunction si («if») is followed by il («he», «it») or ils («they»), which begin with the same vowel sound i: *si il → s’il («if it», if he»); *si ils → s’ils («if they»).

Certain prepositions are also mandatorily merged with masculine and plural direct articles: au for à le, aux for à les, du for de le, and des for de les. However, the contraction of cela (demonstrative pronoun «that») to ça is optional and informal.

In informal speech, a personal pronoun may sometimes be contracted onto a following verb. For example, je ne sais pas (IPA: [ʒənəsɛpa], «I don’t know») may be pronounced roughly chais pas (IPA: [ʃɛpa]), with the ne being completely elided and the [ʒ] of je being mixed with the [s] of sais.[original research?] It is also common in informal contexts to contract tu to t’- before a vowel, e.g., t’as mangé for tu as mangé.

Hebrew[edit]

In Modern Hebrew, the prepositional prefixes -בְּ /bə-/ ‘in’ and -לְ /lə-/ ‘to’ contract with the definite article prefix -ה (/ha-/) to form the prefixes -ב /ba/ ‘in the’ and -ל /la/ ‘to the’. In colloquial Israeli Hebrew, the preposition את (/ʔet/), which indicates a definite direct object, and the definite article prefix -ה (/ha-/) are often contracted to ‘ת (/ta-/) when the former immediately precedes the latter. Thus ראיתי את הכלב (/ʁaˈʔiti ʔet haˈkelev/, «I saw the dog») may become ראיתי ת’כלב (/ʁaˈʔiti taˈkelev/).

Italian[edit]

In Italian, prepositions merge with direct articles in predictable ways. The prepositions a, da, di, in, su, con and per combine with the various forms of the definite article, namely il, lo, la, l’, i, gli, gl’, and le.

| il | lo | la | l’ | i | gli | (gl’) | le | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a | al | allo | alla | all’ | ai | agli | (agl’) | alle |

| da | dal | dallo | dalla | dall’ | dai | dagli | (dagl’) | dalle |

| di | del | dello | della | dell’ | dei | degli | (degl’) | delle |

| in | nel | nello | nella | nell’ | nei | negli | (negl’) | nelle |

| su | sul | sullo | sulla | sull’ | sui | sugli | (sugl’) | sulle |

| con | col | (collo) | (colla) | (coll’) | coi | (cogli) | (cogl’) | (colle) |

| per | (pel) | (pello) | (pella) | (pell’) | (pei) | (pegli) | (pegl’) | (pelle) |

- Contractions with a, da, di, in, and su are mandatory, but those with con and per are optional.

- Words in parentheses are no longer very commonly used. However, there’s a difference between pel and pei, which are old-fashioned, and the other contractions of per, which are frankly obsolete. Col and coi are still common; collo, colla, cogli and colle are nowadays rare in the written language, but common in speaking.

- Formerly, gl’ was often used before words beginning with i, however it is no longer in very common (written) use.

The words ci and è (form of essere, to be) and the words vi and è are contracted into c’è and v’è (both meaning «there is»).

- «C’è / V’è un problema» – There is a problem

The words dove and come are contracted with any word that begins with e, deleting the -e of the principal word, as in «Com’era bello!» – «How handsome he / it was!», «Dov’è il tuo amico?» – «Where’s your friend?» The same is often true of other words of similar form, e.g. quale.

The direct object pronouns «lo» and «la» may also contract to form «l'» with a form of «avere», such as «L’ho comprato» — «I have bought it», or «L’abbiamo vista» — «We have seen her».[8]

Spanish[edit]

Spanish has two mandatory phonetic contractions between prepositions and articles: al (to the) for a el, and del (of the) for de el (not to be confused with a él, meaning to him, and de él, meaning his or, more literally, of him).

Other contractions were common in writing until the 17th century, the most usual being de + personal and demonstrative pronouns: destas for de estas (of these, fem.), daquel for de aquel (of that, masc.), dél for de él (of him) etc.; and the feminine article before words beginning with a-: l’alma for la alma, now el alma (the soul). Several sets of demonstrative pronouns originated as contractions of aquí (here) + pronoun, or pronoun + otro/a (other): aqueste, aqueso, estotro etc. The modern aquel (that, masc.) is the only survivor of the first pattern; the personal pronouns nosotros (we) and vosotros (pl. you) are remnants of the second. In medieval texts, unstressed words very often appear contracted: todol for todo el (all the, masc.), ques for que es (which is); etc. including with common words, like d’ome (d’home/d’homme) instead de ome (home/homme), and so on.

Though not strictly a contraction, a special form is used when combining con with mí, ti, or sí, which is written as conmigo for *con mí (with me), contigo for *con ti (with you sing.), consigo for *con sí (with himself/herself/itself/themselves (themself).)

Finally, one can hear[clarification needed] pa’ for para, deriving as pa’l for para el, but these forms are only considered appropriate in informal speech.

Portuguese[edit]

In Portuguese, contractions are common and much more numerous than those in Spanish. Several prepositions regularly contract with certain articles and pronouns. For instance, de (of) and por (by; formerly per) combine with the definite articles o and a (masculine and feminine forms of «the» respectively), producing do, da (of the), pelo, pela (by the). The preposition de contracts with the pronouns ele and ela (he, she), producing dele, dela (his, her). In addition, some verb forms contract with enclitic object pronouns: e.g., the verb amar (to love) combines with the pronoun a (her), giving amá-la (to love her).

Another contraction in Portuguese that is similar to English ones is the combination of the pronoun da with words starting in a, resulting in changing the first letter a for an apostrophe and joining both words. Examples: Estrela d’alva (A popular phrase to refer to Venus that means «Alb star», as a reference to its brightness) ; Caixa d’água (water tank).

German[edit]

In informal, spoken German prepositional phrases, one can often merge the preposition and the article; for example, von dem becomes vom, zu dem becomes zum, or an das becomes ans. Some of these are so common that they are mandatory. In informal speech, aufm for auf dem, unterm for unter dem, etc. are also used, but would be considered to be incorrect if written, except maybe in quoted direct speech, in appropriate context and style.

The pronoun es often contracts to ‘s (usually written with the apostrophe) in certain contexts. For example, the greeting Wie geht es? is usually encountered in the contracted form Wie geht’s?.

Local languages in German-speaking areas[edit]

Regional dialects of German, and various local languages that usually were already used long before today’s Standard German was created, do use contractions usually more frequently than German, but varying widely between different local languages. The informally spoken German contractions are observed almost everywhere, most often accompanied by additional ones, such as in den becoming in’n (sometimes im) or haben wir becoming hamwer, hammor, hemmer, or hamma depending on local intonation preferences. Bavarian German features several more contractions such as gesund sind wir becoming xund samma, which are schematically applied to all word or combinations of similar sound. (One must remember, however, that German wir exists alongside Bavarian mir, or mia, with the same meaning.) The Munich-born footballer Franz Beckenbauer has as his catchphrase «Schau mer mal» («Schauen wir einmal» — in English «We shall see.»). A book about his career had as its title the slightly longer version of the phrase, «Schau’n Mer Mal».

Such features are found in all central and southern language regions. A sample from Berlin: Sag einmal, Meister, kann man hier einmal hinein? is spoken as Samma, Meesta, kamma hier ma rin?

Several West Central German dialects along the Rhine River have built contraction patterns involving long phrases and entire sentences. In speech, words are often concatenated, and frequently the process of «liaison» is used. So, [Dat] kriegst Du nicht may become Kressenit, or Lass mich gehen, habe ich gesagt may become Lomejon haschjesaat.

Mostly, there are no binding orthographies for local dialects of German, hence writing is left to a great extent to authors and their publishers. Outside quotations, at least, they usually pay little attention to print more than the most commonly spoken contractions, so as not to degrade their readability. The use of apostrophes to indicate omissions is a varying and considerably less frequent process than in English-language publications.

Indonesian[edit]

In standard Indonesian, there are no contractions applied, although Indonesian contractions exist in Indonesian slang. Many of these contractions are terima kasih to makasih (thank you), kenapa to napa (why), nggak to gak (not), and sebentar to tar (a moment).

Norwegian[edit]

The use of contractions is not allowed in any form of standard Norwegian spelling; however, it is fairly common to shorten or contract words in spoken language. Yet, the commonness varies from dialect to dialect and from sociolect to sociolect—it depends on the formality etc. of the setting. Some common, and quite drastic, contractions found in Norwegian speech are «jakke» for «jeg har ikke», meaning «I do not have» and «dække» for «det er ikke», meaning «there is not». The most frequently used of these contractions—usually consisting of two or three words contracted into one word, contain short, common and often monosyllabic words like jeg, du, deg, det, har or ikke. The use of the apostrophe (‘) is much less common than in English, but is sometimes used in contractions to show where letters have been dropped.

In extreme cases, long, entire sentences may be written as one word. An example of this is «Det ordner seg av seg selv» in standard written Bokmål, meaning «It will sort itself out» could become «dånesæsæsjæl» (note the letters Å and Æ, and the word «sjæl», as an eye dialect spelling of selv). R-dropping, being present in the example, is especially common in speech in many areas of Norway[which?], but plays out in different ways, as does elision of word-final phonemes like /ə/.

Because of the many dialects of Norwegian and their widespread use it is often difficult to distinguish between non-standard writing of standard Norwegian and eye dialect spelling. It is almost universally true that these spellings try to convey the way each word is pronounced, but it is rare to see language written that does not adhere to at least some of the rules of the official orthography. Reasons for this include words spelled unphonemically, ignorance of conventional spelling rules, or adaptation for better transcription of that dialect’s phonemes.

Latin[edit]

Latin contains several examples of contractions. One such case is preserved in the verb nolo (I am unwilling/do not want), which was formed by a contraction of non volo (volo meaning «I want»). Similarly this is observed in the first person plural and third person plural forms (nolumus and nolunt respectively).

Japanese[edit]

Some contractions in rapid speech include ~っす (-ssu) for です (desu) and すいません (suimasen) for すみません (sumimasen). では (dewa) is often contracted to じゃ (ja). In certain grammatical contexts the particle の (no) is contracted to simply ん (n).

When used after verbs ending in the conjunctive form ~て (-te), certain auxiliary verbs and their derivations are often abbreviated. Examples:

| Original form | Transliteration | Contraction | Transliteration |

|---|---|---|---|

| ~ている/~ていた/~ています/etc. | -te iru / -te ita / -te imasu / etc. | ~てる/~てた/~てます/etc. | -te ru / -te ta / -te masu / etc. |

| ~ていく/~ていった/etc.* | -te iku / -te itta / etc.* | ~てく/~てった/etc.* | -te ku / -te tta / etc.* |

| ~ておく/~ておいた/~ておきます/etc. | -te oku / -te oita / -te okimasu / etc. | ~とく/~といた/~ときます/etc. | -toku / -toita / -tokimasu / etc. |

| ~てしまう/~てしまった/~てしまいます/etc. | -te shimau / -te shimatta / -te shimaimasu / etc. | ~ちゃう/~ちゃった/~ちゃいます/etc. | -chau / -chatta / -chaimasu / etc. |

| ~でしまう/~でしまった/~でしまいます/etc. | -de shimau / -de shimatta / -de shimaimasu / etc. | ~じゃう/~じゃった/~じゃいます/etc. | -jau / -jatta / -jaimasu / etc. |

| ~ては | -te wa | ~ちゃ | -cha |

| ~では | -de wa | ~じゃ | -ja |

| ~なくては | -nakute wa | ~なくちゃ | -nakucha |

* this abbreviation is never used in the polite conjugation, to avoid the resultant ambiguity between an abbreviated ikimasu (go) and the verb kimasu (come).

The ending ~なければ (-nakereba) can be contracted to ~なきゃ (-nakya) when it is used to indicate obligation. It is often used without an auxiliary, e.g., 行かなきゃ(いけない) (ikanakya (ikenai)) «I have to go.»

Other times, contractions are made to create new words or to give added or altered meaning:

- The word 何か (nanika) «something» is contracted to なんか (nanka) to make a colloquial word with a meaning along the lines of «sort of,» but that can be used with almost no meaning. Its usage is as a filler word is similar to English «like.»

- じゃない (ja nai) «is not» is contracted to じゃん (jan), which is used at the end of statements to show the speaker’s belief or opinion, often when it is contrary to that of the listener, e.g., いいじゃん! (ii jan!) «What, it’s fine!»

- The commonly used particle-verb phrase という (to iu) is often contracted to ~って/~て/~っつー (-tte/-te/-ttsū) to give a more informal or noncommittal feeling.

- といえば (to ieba), the conditional form of という (to iu) mentioned above, is contracted to ~ってば (-tte ba) to show the speaker’s annoyance at the listener’s failure to listen to, remember, or heed what the speaker has said, e.g., もういいってば! (mō ii tte ba!), «I already told you I don’t want to talk about it anymore!».

- The common words だ (da) and です (desu) are older contractions that originate from である (de aru) and でございます (de gozaimasu). These are fully integrated into the language now, and are not generally thought of as contractions; however in formal writing (e.g., literature, news articles, or technical/scientific writing), である (de aru) is used in place of だ (da).

- The first-person singular pronoun 私 is pronounced わたくし (watakushi) in very formal speech, but commonly contracted to わたし(watashi) in less formal speech, and further clipped in specifically younger women’s speech to あたし (atashi).

Various dialects of Japanese also use their own specific contractions that are often unintelligible to speakers of other dialects.

Polish[edit]

In the Polish language pronouns have contracted forms that are more prevalent in their colloquial usage. Examples are go and mu. The non-contracted forms are jego (unless it is used as a possessive pronoun) and jemu, respectively. The clitic -ń, which stands for niego (him) as in dlań (dla niego), is more common in literature. The non-contracted forms are generally used as a means to accentuate.[9]

Uyghur[edit]

Uyghur, a Turkic language spoken in Central Asia, includes some verbal suffixes that are actually contracted forms of compound verbs (serial verbs). For instance, sëtip alidu (sell-manage, «manage to sell») is usually written and pronounced sëtivaldu, with the two words forming a contraction and the [p] leniting into a [v] or [w].[original research?]

Filipino/Tagalog[edit]

In Filipino, most contractions need other words to be contracted correctly. Only words that end with vowels can make a contraction with words like «at» and «ay.» In this chart, the «@» represents any vowel.

| Full form | Contracted | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| ~@ at | ~@’t | |

| ~@ ay | ~@’y | |

| ~@ ng | ~@’n | Informal. as in «Isa’n libo» |

| ~@ ang | ~@’ng |

See also[edit]

- Apostrophe

- Blend

- Clipping (morphology)

- Contractions of negated auxiliary verbs in English

- Elision

- List of common English usage misconceptions

- Poetic contraction

- Synalepha

- Syncope (phonetics)

Notes[edit]

- ^ Fixed compound is a word phrase used grammatically as a noun or other part of speech (but in this case not a verb) where the phrase is invariant and widely understood. The phrase does not change no matter where it occurs in a sentence or elsewhere, nor can individual elements be substituted with synonyms (but alternatives to the compound may exist). May be considered idiomatic, though the meaning of most were transparent when coined. Many are usually written hyphenated, but this reflects a common preference to hyphenate English compounds (except verbs) containing prepositions. «Fixed» being a matter of degree, in this case it essentially means «standard»—that the contraction is not considered informal is the best sign that it is fixed.

- ^ In varieties that do not normally mark plurality (so use unmodified you as the pronoun when addressing a single person or group), there may be times when a speaker wants to make clear that they are addressing multiple people by employing you all (or both of you, etc.)—in which case the contraction y’all would never be used. (The contraction is a strong sign of an English variety that normally marks plurality.)

References[edit]

- ^ Roberts R; et al. (2005). New Hart’s Rules: The handbook of style for writers and editors. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-861041-6. : p.167

- ^ «Online Etymology Dictionary». Retrieved 27 May 2016.

- ^ «Online Etymology Dictionary». Retrieved 27 May 2016.

- ^ «乜嘢». Retrieved 27 May 2016.

- ^ a b c Edwin G. Pulleyblank (1995). Outline of Classical Chinese Grammar. University of British Columbia Press. ISBN 978-0-7748-0505-6.

- ^ a b Old Chinese reconstruction search Archived 2011-12-03 at the Wayback Machine containing William H. Baxter’s reconstructions.

- ^ Pulleyblank, Edwin G. (Edwin George), 1922- (1995). Outline of classical Chinese grammar. Vancouver: UBC Press. p. 80. ISBN 0774805056. OCLC 32087090.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ «Direct Object Pronouns in Italian: A Complete Guide to These Important Little Words». 13 January 2020.

- ^ http://nkjp.pl/settings/papers/NKJP_ksiazka.pdf (p.82)

-

EM

-

Articles

-

Usage

-

Punctuation

Summary

Contractions are shortened forms of words, in which some letters are omitted. An apostrophe generally marks the omission. Standard contractions include those that shorten the word not, the verbs be and have, and modal verbs. Here is a list of commonly used contractions.

| Contraction | Full form | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| n’t | not | don’t (do not), isn’t (is not) |

| ’s | is, has | she’s (she is, she has), what’s (what is, what has) |

| ’re | are | you’re (you are), we’re (we are) |

| ’ve | have | I’ve (I have), could’ve (could have) |

| ’d | had, would | I’d (I had, I would), we’d (we had, we would) |

| ’ll | will | I’ll (I will), you’ll (you will) |

| I’m | I am | |

| let’s | let us | |

| ma’am | madam |

(See also: List of standard contractions in English)

Contractions are often used in speech and lend an informal, personal tone to writing. Avoid using contractions in formal texts, such as academic papers.

Example

- Informal: We haven’t accounted for changes in pressure in this study.

Formal: We have not accounted for changes in pressure in this study.

What is a contraction in grammar?

A contraction is a word in which some sounds or letters are omitted. An apostrophe generally replaces the omitted letters. Contractions are common in speech and informal writing.

Examples

- What’s going on?

what is = what’s (an apostrophe replaces the “i” in is)

- I don’t know.

do not = don’t (an apostrophe indicates the omitted “o” in not)

I’m happy to help.

I am = I’m (an apostrophe replaces “a”)

Common contractions in English shorten the word not (isn’t, shouldn’t), the be verb (I’m, she’s, we’re), the have verb (you’ve, could’ve), and modal verbs (we’ll, they’d).

When should contractions be used?

Contractions lend an informal tone to writing and replace talking to your reader. In messages and personal communication, contractions sound normal and natural.

Examples

- I’m on my way.

- That’s fine. Don’t worry.

- It’s all right.

- Sorry I couldn’t take your call.

In contrast, in academic and other formal texts, avoiding contractions lends an air of formality to the document.

Examples

- Informal: We couldn’t collect sufficient real-world data.

Formal: We could not collect sufficient real-world data. - Informal: It’s important to account for bias.

Formal: It is important to account for bias.

In ad copy, marketing slogans, and other signage, contractions can help save space and make your message sound more friendly.

Examples

- It’s finger lickin’ good. (KFC)

- I’m lovin’ it. (McDonald’s)

- Because you’re worth it. (L’Oreal)

In creative writing as well, contractions, which are common in speech, can make dialogue sound more natural.

Example

- “Now you said you’d do it, now let’s see you do it.”

“Don’t you crowd me now; you better look out.”

“Well, you said you’d do it—why don’t you do it?”— Mark Twain, The Adventures of Tom Sawyer (1876)

Caution

Avoid using contractions in formal texts, such as academic papers, cover letters, and business proposals.

Example

- Informal: We haven’t reviewed the financial statements of the subsidiaries yet.

Formal: We have not reviewed the financial statements of the subsidiaries yet.

In this article, we discuss common contractions in English and when they are used.

Contractions with not

Not can be contracted to n’t when it is used with an auxiliary verb like can and have.

Examples

- I can’t believe you don’t have a phone. (cannot, do not)

- Haven’t you pressed the button yet? (have not)

- I won’t tell anyone what happened. (will not)

- Nesbit shouldn’t spend all his time indoors. (should not)

Can, which already ends in n, combines with not to form can’t. Will and shall lose their endings and combine with not to form won’t and shan’t.

Here is a list of not contractions in English: note how the adverb not combines with both primary (be, have, do) and modal auxiliary verbs (like can and could).

| Contraction | Full form |

|---|---|

| don’t | do not |

| didn’t | did not |

| isn’t | is not |

| wasn’t | was not |

| aren’t | are not (also am not) |

| weren’t | were not |

| hasn’t | has not |

| haven’t | have not |

| hadn’t | had not |

| can’t | cannot |

| couldn’t | could not |

| shan’t | shall not |

| shouldn’t | should not |

| won’t | will not |

| wouldn’t | would not |

| mightn’t | might not |

| mustn’t | must not |

| needn’t | need not |

Be verb with not

The be verb contracts with not in two ways: you can either contract the verb form itself (is, are, am) or contract not.

Examples

- Contracted not: Anita isn’t ready.

- Contracted be verb: She’s not ready.

The word not is contracted more often with nouns.

Examples

- Farley isn’t happy.

Seen more often than “Farley’s not happy.” (The name “Farley” of course is a noun.)

- The books aren’t here.

Seen more often than “The books’re not here.” (“The books” is a noun phrase.)

The be verb is contracted more often with pronouns.

Examples

- She’s not happy.

Seen more often than “She isn’t happy” (where “she” is a pronoun).

- They’re not here.

Seen more often than “They aren’t here.”

Amn’t or aren’t?

With the pronoun I, use aren’t not amn’t to frame questions.

Examples

- Aren’t I clever?

- I’m your friend, aren’t I?

for “I’m your friend,

am I not

?”

However, when the sentence is not a question but a statement, “I am not” is usually contracted to “I’m not” rather than “I aren’t.”

Example

- I’m not joking.

Generally preferred to “I aren’t joking.”

In some dialects (Scottish and Irish), amn’t is acceptable in speech but still avoided in writing.

Ain’t (nonstandard)

Ain’t is a nonstandard contraction used colloquially in some dialects, where it replaces the relatively more formal contractions isn’t and aren’t.

Examples

- I ain’t dead.

- They ain’t listenin’.

- That ain’t important now, is it?

- It ain’t done till I say it’s done.

It may occasionally also replace hasn’t or haven’t.

Example

- They ain’t made a lock yet our Nesbit can’t pick.

Caution

The contraction ain’t is considered nonstandard and used only very informally.

Be and have contractions

Be and have, which take the verb forms am, is, are, has, have, and had, can contract and combine with a noun or pronoun (and occasionally, an adverb).

Examples

- Lulu’s a dancer. (Lulu is)

- Your order’s being processed. (order is)

- I’m not ready. (I am)

- They’re already here. (they are)

- Lulu’s been baking again. (Lulu has been)

- They’ve found the answer. (they have found)

- She’d called me already before you got here. (she had called)

- Here’s your money. (here is)

- There’s no money in this purse. (there is)

- That’s the restaurant I was telling you about. (that is)

Note that the have verb is not contracted in writing when it is the main verb and means “to possess.”

Example

- Poor: Poco’s seven cars in his garage.

The main verb is has: Poco

has

. Don’t contract it.

Better: Poco has seven cars in his garage.

- Poor: We’d no money.

Better: We had no money. - Acceptable: Poco’s bought another car.

The main verb is bought: Poco has bought. Has functions as an auxiliary (or helping) verb and can be contracted.

- Acceptable: We’d discovered the cure by then.

but

Tip

Don’t use affirmative contractions at the end of a clause or a sentence.

Examples

- Incorrect:“Have you ordered the shoes?” “Yes, I’ve.”

Correct:“Have you ordered the shoes?” “Yes, I have.” - Incorrect:“Are you ready?” “I don’t know that I’m.”

Correct:“Are you ready?” “I don’t know that I am.” - Incorrect:“Would you help me if you could?” “Of course I’d.”

Correct: “Would you help me if you could?” “Of course I would.”

In contrast, negative contractions are acceptable at the end of a clause or a sentence.

Examples

- Correct: No, I haven’t.

- Correct: Of course I wouldn’t.

Contractions with pronouns

Personal pronouns like I, you, and they combine with the be and have verbs (am, is, are, has, have) to form standard contractions. These pronouns also combine with the modal verbs will and would.

Examples

- Hi, I’m Maya. (I am)

- You’re coming with me. (you are)

- It’s my first day at work. (it is)

- We’re happy to help. (we are)

- She’s had a long day. (she has)

- They’ve all gone on a picnic together. (they have)

- I knew he’d been fighting. (he had)

- Of course I’ll help you. (I will)

- She’d know if we were lying. (she would)

The following table shows how contractions for personal pronouns are formed.

| Contraction | Full form | Pronoun contraction |

|---|---|---|

| ’m | am | I’m |

| ’s | is, has | she’s, he’s, it’s |

| ’re | are | we’re, you’re, they’re |

| ’ve | have | I’ve, you’ve, we’ve, they’ve |

| ’d | had, would | I’d, you’d, he’d, she’d, it’d, we’d, they’d |

| ’ll | will | I’ll, you’ll, he’ll, she’ll, it’ll, we’ll, they’ll |

Note how contractions with ’s can be short for either is or has: “He’s” can mean “he is” or “he has.” Similarly, contractions with ’d can stand for either had or would: “I’d” means both “I had” and “I would.”

Caution

The contraction of “you are” is you’re, not your.

Examples

- Incorrect: Your not wrong.

Correct: You’re not wrong. (you are) - Incorrect: Your your own worst enemy.

Correct: You’re your own worst enemy. (you are)

Your is a possessive that appears before a noun.

Examples

- Your answers are not wrong.

- The enemy of your enemy is your friend.

Tip

Insert an apostrophe in its only if it is a contraction of “it is” or “it has.” Omit the apostrophe when it is a possessive.

Examples

- It’s raining.

it’s = it is (contraction)

- It’s stopped raining.

it’s = it has (contraction)

The kitten is chasing its tail.

its tail = the kitten’s tail (possessive; no apostrophe)

Other pronouns like that, which, and who can also form contractions with be and have in informal usage.

Examples

- That’s not true! (that is)

- The report that’s being released today is misleading. (that is)

- My friend Farley, who’s an astronaut, is afraid of heights. (who is)

- The person who’s been eating all the cookies is me. (who has)

- These reports, which’ve already been released, are misleading. (which have)

Contractions with nouns

In speech, nouns form contractions with is and has (singular forms of the be and have verbs). These contractions are not generally seen in writing, and never in formal texts.

Examples

- Rita’s my sister. (Rita is)

- Farley’s in quarantine this week. (Farley is)

- Your money’s on the way. (money is)

- My daughter’s going to Thailand in May. (daughter is)

- The cat’s been eating all the cheese again. (cat has)

- Anita’s found the answer! (Anita has)

It is rarer for the plural verbs are and have to join with nouns (cakes’re baked; the cats’ve been eating).

Contractions with adverbs

Adverbs like now, here, and there combine with is to form contractions in informal usage.

Examples

- Now’s your chance! (now is)

- Here’s the entrance to the cave. (here is)

- There’s a slight chance I might be wrong. (there is)

There can also form a contraction with has.

Example

- There’s been no change in status since we last spoke. (there has)

Plural contractions are rarer: there’re, there’ve.

Contractions with modal verbs

Modal verbs like could and would combine with have.

Examples

- You could’ve done better, but you didn’t even try. (could have)

- (would have)

- You should’ve given her a chance to explain. (should have)

Caution

Could have and should have are contracted to could’ve and should’ve, not could of or should of. Could’ve is sometimes incorrectly written as could of because of how this contraction is pronounced.

Examples

- You

could of/could’ve told me you had an extra phone. - I

should of/should’ve realized this would be a problem.

Will and would are contracted to ’ll and ’d in casual communication.

Examples

- Anita’ll never believe what just happened. (Anita will)

- I’ll buy the flowers myself. (I will)

- You’ll call me, won’t you? (you will)

- They’ll call us tomorrow. (they will)

- You’d never know she was lying. (you would)

- We’d like to cancel our membership. (we would)

Modal verbs can also form contractions with not.

Examples

- Farley can’t find his shoes. (cannot)

- She won’t tell anyone. (will not)

- I wouldn’t know where to begin. (would not)

- It shouldn’t be this hard. (should not)

Here is a list of contractions with modal verbs.

| Contraction | Full form |

|---|---|

| could’ve | could have |

| should’ve | should have |

| would’ve | would have |

| might’ve | might have |

| must’ve | must have |

| ’ll | will (I’ll, you’ll, we’ll) |

| ’d | would (I’d, she’d, they’d) |

| can’t | cannot |

| couldn’t | could not |

| shan’t | shall not |

| shouldn’t | should not |

| won’t | will not |

| wouldn’t | would not |

| mightn’t | might not |

| mustn’t | must not |

| oughtn’t | ought not |

| needn’t | need not |

Contractions in questions

Negative forms using not are contracted in questions, not only in speech but also in formal usage.

Examples

- Hasn’t Rita returned from Neptune yet?

Not “

Has not

Rita returned yet?,” which would sound odd and archaic.

- Don’t you want to get paid?

- Couldn’t you find the answer?

- Can’t you see I’m busy?

Negative question tags are also always contracted.

Examples

- Farley should be given another chance, shouldn’t he?

Not “Should not he?”

- Rita has come back, hasn’t she?

- Help me out, won’t you?

Forms of be and have can combine with question words like who and what in speech.

Examples

- What’s going on? (what is)

- What’s happened to him? (what has)

- What’ve you done? (what have)

- Where’s Anita when you need her? (where is)

- Where’s she gone? (where has)

- Where’ve you been? (where have)

- Who’s that? (who is)

- Who’s been eating all my porridge? (who has)

- Who’ve you been talking to? (who have)

Contractions of words like what, where, and there with the plural verb are (what’re, where’re, there’re) are less common than singular forms (what’s, where’s, there’s).

Tip

Who’s is a contraction of who is, while whose is a possessive.

Examples

- Who’s/

Whosethat at the window?who’s = who is (contraction)

- Who’s/

Whosebeen sitting in my chair?who’s = who has (contraction)

Who’s/Whose chair is this?whose = whom does it belong to (possessive)

Double contractions

Double contractions with have occur in speech but not in writing.

Examples

- Rita couldn’t’ve planned this all by herself. (could not have)

- Poco shouldn’t’ve bought that new car. (should not have)

- I’d’ve known if she’d been lying. (I would have)

The be verb doesn’t form double contractions.

Examples

- Incorrect: She’sn’t not happy.

Correct: She’s not happy.

Correct: She isn’t happy. - Incorrect: I’mn’t going on holiday this year.

Correct: I’m not going on holiday this year.

Other contractions

Certain words like ma’am are contracted in speech. An apostrophe is used to signify the omitted sounds.

Examples

- Yes, ma’am. I’ll send you the report today. (for madam)

- Call the bo’s’n! (for boatswain)

Let’s

The contraction let’s, used often in speech, is a contraction of let us, not let is. Use let’s to make suggestions.

Examples

- Let’s go watch a movie. (let us)

- Let’s play a game, shall we? (let us)

O’clock (contracted of)

The contraction o’clock is short for “of the clock” and is used to indicate time.

Examples

- Is it nine o’clock already?

- I usually wake up at six o’clock.

The word of is also contracted in other terms like man-o’-war, will-o’-the-wisp, cat-o’-nine-tails, and jack-o’-lantern.

G-dropping

In some dialects of English, the final sound of a word ending in -ing is not pronounced. When such speech is transcribed, an apostrophe is used to indicate the omitted “g.”

Examples

- We were just singin’ and dancin’ in the rain.

- Well, you know he’s a ramblin’ man.

Relaxed pronunciation

Phrases such as kind of and sort of, commonly used in casual conversation, are often contracted to kinda and sorta.

Examples

- I’m kinda confused about this layout.

- I’m sorta impressed by what she has done here.

- Would you like a cuppa tea?

In everyday speech, the infinitive marker to is sometimes combined with words such as going and want. Note that these are colloquialisms never used in formal writing.

Examples

- I wanna fly like a bird.

- I’m gonna go now.

- I hafta find out what happened.

Aphaeresis, syncope, apocope

In informal speech, the first unstressed syllable of a word is sometimes dropped (by a process called aphaeresis.) An apostrophe marks the missing syllable.

Examples

- I ain’t talkin’ ’bout that.

about

- You’ll do it ’cause I asked you to.

because

When a syllable or sound from the middle of a word is dropped, it is called syncope. An apostrophe marks the elision. It is often found in poetry, where meter is helped by the dropping of a sound.

Examples

- They flew o’er hills and mountains.

- Yes, ma’am, we have rooms available.

The omission or elision of syllables at the end of a word is called apocope.

Examples

- Did you watch the match on tele last night? (short for television)

- Have you uploaded the photo? (for photograph)

Poetic contractions

Words may be contracted in poetry for the sake of rhythm and meter. Such contractions are not otherwise found in writing. These include words like o’er (over), ’tis (it is), ’twas (it was), e’er (ever), and ne’er (never). Note that modern poets do not often require or use poetic contractions.

Examples

It ate the food it ne’er had eat,

And round and round it flew.I, smiling at him, shook my head:

’Tis now we’re tired, my heart and I.Gliding o’er all, through all,

Through Nature, Time, and Space . . .

Note

A contraction is a form of elision, in which sounds or syllables are elided or omitted for ease of speaking or for the sake of meter.

List of standard contractions in English

Here is a list of over 70 commonly used contractions in English.

| Contraction | Full form |

|---|---|

| don’t | do not |

| didn’t | did not |

| isn’t | is not |

| wasn’t | was not |

| aren’t | are not (also am not) |

| weren’t | were not |

| hasn’t | has not |

| haven’t | have not |

| hadn’t | had not |

| can’t | cannot |

| couldn’t | could not |

| shan’t | shall not |

| shouldn’t | should not |

| won’t | will not |

| wouldn’t | would not |

| mightn’t | might not |

| mustn’t | must not |

| oughtn’t | ought not |

| needn’t | need not |

| could’ve | could have |

| should’ve | should have |

| would’ve | would have |

| might’ve | might have |

| must’ve | must have |

| I’m | I am |

| you’re | you are |

| she’s | she is, she has |

| he’s | he is, he has |

| it’s | it is, it has |

| we’re | we are |

| they’re | they are |

| I’ve | I have |

| you’ve | you have |

| we’ve | we have |

| they’ve | they have |

| I’ll | I will |

| you’ll | you will |

| he’ll | he will |

| she’ll | she will |

| it’ll | it will |

| we’ll | we will |

| they’ll | they will |

| I’d | I had, I would |

| you’d | you had, you would |

| she’d | she had, she would |

| he’d | he had, he would |

| it’d | it had, it would |

| we’d | we had, we would |

| they’d | they had, they would |

| that’s | that is, that has |

| that’ve | that have |

| that’d | that would |

| which’ve | which have |

| who’s | who is, who has |

| who’re | who are |

| who’ve | who have |

| who’d | who had, who would |

| who’ll | who will |

| what’s | what is, what has, what does |

| what’re | what are |

| what’ll | what will |

| where’s | where is, where has |

| where’d | where did |

| when’s | when is, when has |

| why’s | why is, why has |

| why’d | why did |

| how’s | how is, how has |

| here’s | here is |

| there’s | there is, there has |

| there’ll | there will |

| there’d | there had, there would |

| let’s | let us |

| ma’am | madam |

| o’clock | of the clock |

When I want to express the count of something, can I say «xxx number» instead of «the number of xxx»?

For example:

«Location number» to mean the number of locations.

«Apple number» to mean the number of apples.

If putting the word «number» after the counted thing like this applies conditionally, what’s the conditions?

Thank you for your help.

asked Jan 9, 2015 at 6:32

0

You can use the word count though.

‘Location count‘ refers to the total number of locations.

‘Apple count‘ refers to the total number of apples.

answered Jan 9, 2015 at 6:54

JimJim

33.2k10 gold badges74 silver badges126 bronze badges

0

If I understand you correctly, then I don’t think what you’re asking is acceptable usage. If you said «target number 3» or even «target 3», I would assume that you were indicating a label, not the amount. I would assume you’re talking about the third in a series of targets, but I wouldn’t assume I have any information about how many targets there are total.

answered Jan 9, 2015 at 6:36

1

As others have said, you can’t generally use the word number to mean count. That is, you can’t say «Location number: three» to mean «There are three locations».

There does exist one specialist, specific instance where number does mean count: in inventory listings.

- Screws, large, 24 number

- Screws, small, one gross

It’s not very common, and it is rather old-fashioned. It’s probably used to ensure that the meaning of 24 [in this case] is understood as a number of items rather than anything else, and could be a contraction of in number.

For your locations example, you might be able to use «24 in number».

[In such listings, off is also used to indicate the number (the phrase «one-off» is still current), but I have seen number used in this way.]

answered Jan 16, 2015 at 11:50

Andrew Leach♦Andrew Leach

98.3k12 gold badges188 silver badges306 bronze badges

As you can tell from the term, contractions are used in English grammar to compress words or sentences. A contraction lowers the length of a word or phrase by omitting letters. In written texts, an apostrophe is used to indicate missing letters. You will learn more about the importance of it along with some examples here. In this article, you will learn the basics and importance of contractions in English grammar.

What are Contractions in English Grammar?

We come across contractions in our daily lives. Contractions are frequently used in casual writings and casual speaking. Verbs are frequently at the heart of any contraction. “Shouldn’t” is an instance of a contraction.

It’s the abbreviated version of the term “should not”. Here you can see that the “o” letter is missing and the word is smaller now with an addition of an apostrophe. Now, that you know the contractions meaning in English grammar, let’s move on to the next section on why we use them.

Why Do We Use Contractions?

Every day, we converse with others and utilise contractions. These words reduce the amount of time we spend speaking. The fewer words make it easier for individuals to get to the essence of the topic.

Hearing contractions mispronounced leads to grammatical errors. When spoken quickly, for instance, may sound like words. It might be perplexing for pupils to learn English as a second language. These students assume the terms “would of” and “would’ve” produce it as “would’ve.”

When to Use Contractions?

Contractions, according to certain writers, have no place in any written language. These folks don’t realise that the way you employ them affects the tone of your voice. They are used in informal writing to produce a more appealing tone of speech. A professional piece of writing, on the other hand, needs an authoritative tone.

The tone of voice you want to use in your content says a lot. Is your target audience welcoming? Is it a sombre occasion? It’s crucial to know who you’re attempting to speak with. Consider your intended readers before writing something with them.

Different Types of Contractions

Contractions Using Nouns and Pronouns

The greatest location to hear a contracted term uttered is in a casual conversation. When placed next to a verb, a noun can form part of a contraction. We frequently hear a word like mom used in conjunction with the verb will. A contracted noun is something like “Mom’ll.” In writing, we seldom use this form of contraction.

In writing, however, contracted pronouns are more common. Pronoun contractions include I’ll, He’d, and He’s. Words like “is” and “has” combine pronouns.

Also Read: How to Learn English Through Movies? How to Learn English Quickly?

Ambiguous Contractions

When reading, you may come across an unclear contraction. Without the correct context, they might be perplexing. It would be hard to know whether “he’d” referred to the sentence “he would” or “he had” without context. The letters “s” and “d” are commonly used to conclude ambiguous contractions.

Examples

# She’s 5 years old.

# She’s got 100 dollars in her account.

“She’s” signifies “she is” in the first line. In this context, “she has” makes no sense at all. “She’s” alludes to “she has” in the second phrase. The second option is wrong.

Informal Contractions

When individuals speak casually, their words are shorter. These terms are frequently misunderstood as slang. We frequently hear individuals using terms like “gonna to” in casual contexts. This word came about as a result of people pronouncing “going to” very quickly.

Apostrophes are not required for informal contractions. In the United States of America, they are increasingly common.

# Whatcha gonna do?

# The girl’s kinda cute.

Also Read: The Formula of Present Perfect Continuous Tense: Facts and Rules to Know

Contractions Examples List

Find all the contractions that are used while speaking and writing in the table below:

| Contraction | Word |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Also Read: Pronunciations You Should Avoid: Tips to Work on English Pronunciation

What is the Importance of Contractions in Grammar?

Despite the fact that thousands of words are contracted every day, we’ll concentrate on only one today: “not.”

But first, there are two things to keep in mind. The first is that not using contractions might indicate that you are not a native English speaker. This is due to the frequency with which contractions are employed.

Number two, and most crucially, not using contractions indicates to your audience that you are attempting to emphasise the words you are speaking. This implies that if you don’t contract “not,” for example, you’re emphasising the negative word, implying that you’re angry, unhappy, or otherwise negative.Conclusion

Whether you’ve been learning English for a long period of time or are just getting started, you’ve probably heard a lot of native English speakers use contractions.

When it comes to learning and comprehending English, contractions, or shorter variants of a word created by substituting a letter or sounds with an apostrophe (‘), are extremely significant. Using these shorter terms will improve your ability to comprehend a conversation and suggest that you have a greater degree of pronunciation fluency.

If you want to learn more about English language basics, visit The Fluent Life now!

Also Read: Trick to be Fluent in English: Why is Fluency so Important?

Contractions in English are the shortening of words, phrases, or numerals by omitting characters and replacing them with an apostrophe. The apostrophe represents the missing letters or numbers.

You likely use contractions daily in your communications. In writing and speech, they help us save time in exchanging thoughts and ideas. They conserve space and length in our writing as well. This can be particularly useful in text messages and in media such as commercial and classified advertising.

Contractions in English also contribute to a more-relaxed tone between people. In the proper context, they can show a comfort with someone. In certain cases in business correspondence, they can also establish an image or personality of being trustworthy and “real” as opposed to aloof and clinical.

You are probably familiar with contractions in uses such as:

| he will | he’ll | of the clock | o’clock | |

| they would | they’d | doing | doin’ | |

| rock and roll | rock ‘n’ roll | will not | won’t | |

| class of 1987 | class of ’87 | I am | I’m |

Note that in contractions the apostrophe curves toward—not away from—the missing letters or numbers.

Contractions can often appear within regional dialects. For example, in some parts of the U.S., one might hear or even read (in casual or informal writing) words such as doin’ (doing), goin’ (going), ma’am (madam), and y’all (you all).

It’s also common in American English to contract nouns and immediately following auxiliary (modal) verbs.

Examples

My mom’ll (mom will) be there tomorrow.

Who’s (Who is) going with us to the pot-luck dinner?

Daryl’s (Daryl has) been to Vancouver three times.