In syntactic analysis, a constituent is a word or a group of words that function as a single unit within a hierarchical structure. The constituent structure of sentences is identified using tests for constituents.[1] These tests apply to a portion of a sentence, and the results provide evidence about the constituent structure of the sentence. Many constituents are phrases. A phrase is a sequence of one or more words (in some theories two or more) built around a head lexical item and working as a unit within a sentence. A word sequence is shown to be a phrase/constituent if it exhibits one or more of the behaviors discussed below. The analysis of constituent structure is associated mainly with phrase structure grammars, although dependency grammars also allow sentence structure to be broken down into constituent parts.

Tests for constituents in English[edit]

Tests for constituents are diagnostics used to identify sentence structure. There are numerous tests for constituents that are commonly used to identify the constituents of English sentences. 15 of the most commonly used tests are listed next: 1) coordination (conjunction), 2) pro-form substitution (replacement), 3) topicalization (fronting), 4) do-so-substitution, 5) one-substitution, 6) answer ellipsis (question test), 7) clefting,

The order in which these 15 tests are listed here corresponds to the frequency of use, coordination being the most frequently used of the 15 tests and RNR being the least frequently used. A general word of caution is warranted when employing these tests, since they often deliver contradictory results. The tests are merely rough-and-ready tools that grammarians employ to reveal clues about syntactic structure. Some syntacticians even arrange the tests on a scale of reliability, with less-reliable tests treated as useful to confirm constituency though not sufficient on their own. Failing to pass a single test does not mean that the test string is not a constituent, and conversely, passing a single test does not necessarily mean the test string is a constituent. It is best to apply as many tests as possible to a given string in order to prove or to rule out its status as a constituent.

The 15 tests are introduced, discussed, and illustrated below mainly relying on the same one sentence:[2]

-

- Drunks could put off the customers.

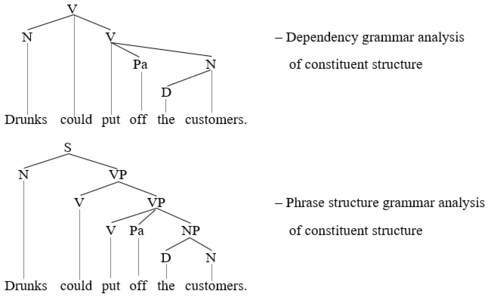

By restricting the introduction and discussion of the tests for constituents below mainly to this one sentence, it becomes possible to compare the results of the tests. To aid the discussion and illustrations of the constituent structure of this sentence, the following two sentence diagrams are employed (D = determiner, N = noun, NP = noun phrase, Pa = particle, S = sentence, V = Verb, VP = verb phrase):

These diagrams show two potential analyses of the constituent structure of the sentence. A given node in a tree diagram is understood as marking a constituent, that is, a constituent is understood as corresponding to a given node and everything that that node exhaustively dominates. Hence the first tree, which shows the constituent structure according to dependency grammar, marks the following words and word combinations as constituents: Drunks, off, the, the customers, and put off the customers.[3] The second tree, which shows the constituent structure according to phrase structure grammar, marks the following words and word combinations as constituents: Drunks, could, put, off, the, customers, the customers, put off the customers, and could put off the customers. The analyses in these two tree diagrams provide orientation for the discussion of tests for constituents that now follows.

Coordination[edit]

The coordination test assumes that only constituents can be coordinated, i.e., joined by means of a coordinator such as and, or, or but:[4] The next examples demonstrate that coordination identifies individual words as constituents:

-

- Drunks could put off the customers.

- (a) [Drunks] and [bums] could put off the customers.

- (b) Drunks [could] and [would] put off the customers.

- (c) Drunks could [put off] and [drive away] the customers.

- (d) Drunks could put off the [customers] and [neighbors].

The square brackets mark the conjuncts of the coordinate structures. Based on these data, one might assume that drunks, could, put off, and customers are constituents in the test sentence because these strings can be coordinated with bums, would, drive away, and neighbors, respectively. Coordination also identifies multi-word strings as constituents:

-

- (e) Drunks could put off [the customers] and [the neighbors].

- (f) Drunks could [put off the customers] and [drive away the neighbors].

- (g) Drunks [could put off the customers] and [would drive away the neighbors].

These data suggest that the customers, put off the customers, and could put off the customers are constituents in the test sentence.

Examples such as (a-g) are not controversial insofar as many theories of sentence structure readily view the strings tested in sentences (a-g) as constituents. However, additional data are problematic, since they suggest that certain strings are also constituents even though most theories of syntax do not acknowledge them as such, e.g.

-

- (h) Drunks [could put off] and [would really annoy] the customers.

- (i) Drunks could [put off these] and [piss off those] customers.

- (j) [Drunks could], and [they probably would], put off the customers.

These data suggest that could put off, put off these, and Drunks could are constituents in the test sentence. Most theories of syntax reject the notion that these strings are constituents, though. Data such as (h-j) are sometimes addressed in terms of the right node raising (RNR) mechanism.

The problem for the coordination test represented by examples (h-j) is compounded when one looks beyond the test sentence, for one quickly finds that coordination suggests that a wide range of strings are constituents that most theories of syntax do not acknowledge as such, e.g.

-

- (k) Sam leaves [from home on Tuesday] and [from work on Wednesday].

- (l) Sam leaves [from home on Tuesday on his bicycle] and [from work on Wednesday in his car].

- (m) Sam leaves [from home on Tuesday], and [from work].

The strings from home on Tuesday and from home on Tuesday on his bicycle are not viewed as constituents in most theories of syntax, and concerning sentence (m), it is very difficult there to even discern how one should delimit the conjuncts of the coordinate structure. The coordinate structures in (k-l) are sometimes characterized in terms of non-constituent conjuncts (NCC), and the instance of coordination in sentence (m) is sometimes discussed in terms of stripping and/or gapping.

Due to the difficulties suggested with examples (h-m), many grammarians view coordination skeptically regarding its value as a test for constituents. The discussion of the other tests for constituents below reveals that this skepticism is warranted, since coordination identifies many more strings as constituents than the other tests for constituents.[5]

Proform substitution (replacement)[edit]

Proform substitution, or replacement, involves replacing the test string with the appropriate proform (e.g. pronoun, pro-verb, pro-adjective, etc.). Substitution normally involves using a definite proform like it, he, there, here, etc. in place of a phrase or a clause. If such a change yields a grammatical sentence where the general structure has not been altered, then the test string is likely a constituent:[6]

-

- Drunks could put off the customers.

- (a) They could put off the customers. (They = Drunks)

- (b) Drunks could put them off. (them = the customers; note that shifting of them and off has occurred here.)

- (c) Drunks could do it. (do it = put off the customers)

These examples suggest that Drunks, the customers, and put off the customers in the test sentence are constituents. An important aspect of the proform test is the fact that it fails to identify most subphrasal strings as constituents, e.g.

-

- (d) *Drunks do so/it put off the customers (do so/it = could)

- (e) *Drunks could do so/it off the customers (do so/it = put)

- (f) *Drunks could put so/it the customers (so/it = off)

- (g) *Drunks could put off the them. (them = customers)

These examples suggest that the individual words could, put, off, and customers should not be viewed as constituents. This suggestion is of course controversial, since most theories of syntax assume that individual words are constituents by default. The conclusion one can reach based on such examples, however, is that proform substitution using a definite proform identifies phrasal constituents only; it fails to identify sub-phrasal strings as constituents.

Topicalization (fronting)[edit]

Topicalization involves moving the test string to the front of the sentence. It is a simple movement operation.[7] Many instances of topicalization seem only marginally acceptable when taken out of context. Hence to suggest a context, an instance of topicalization can be preceded by …and and a modal adverb can be added as well (e.g. certainly):

-

- Drunks could put off the customers.

- (a) …and the customers, drunks certainly could put off.

- (b) …and put off the customers, drunks certainly could.

These examples suggest that the customers and put off the customers are constituents in the test sentence. Topicalization is like many of the other tests in that it identifies phrasal constituents only. When the test sequence is a sub-phrasal string, topicalization fails:

-

- (c) *…and customers, drunks certainly could put off the.

- (d) *…and could, drunks certainly put off the customers.

- (e) *…and put, drunks certainly could off the customers.

- (f) *…and off, drunks certainly could put the customers.

- (g) *…and the, drunks certainly could put off customers.

These examples demonstrate that customers, could, put, off, and the fail the topicalization test. Since these strings are all sub-phrasal, one can conclude that topicalization is unable to identify sub-phrasal strings as constituents.

Do-so-substitution[edit]

Do-so-substitution is a test that substitutes a form of do so (does so, did so, done so, doing so) into the test sentence for the target string. This test is widely used to probe the structure of strings containing verbs (because do is a verb).[8] The test is limited in its applicability, though, precisely because it is only applicable to strings containing verbs:

-

- Drunks could put off the customers.

- (a) Drunks could do so. (do so = put off the customers)

- (b) Drunks do so. (do so ≠ could put off the customers)

The ‘a’ example suggests that put off the customers is a constituent in the test sentence, whereas the b example fails to suggest that could put off the customers is a constituent, for do so cannot include the meaning of the modal verb could. To illustrate more completely how the do so test is employed, another test sentence is now used, one that contains two post-verbal adjunct phrases:

-

- We met them in the pub because we had time.

- (c) We did so in the pub because we had time. (did so = met them)

- (d) We did so because we had time. (did so = met them in the pub)

- (e) We did so. (did so = met them in the pub because we had time)

These data suggest that met them, met them in the pub, and met them in the pub because we had time are constituents in the test sentence. Taken together, such examples seem to motivate a structure for the test sentence that has a left-branching verb phrase, because only a left-branching verb phrase can view each of the indicated strings as a constituent. There is a problem with this sort of reasoning, however, as the next example illustrates:

-

- (f) We did so in the pub. (did so = met them because we had time)

In this case, did so appears to stand in for the discontinuous word combination consisting of met them and because we had time. Such a discontinuous combination of words cannot be construed as a constituent. That such an interpretation of did so is indeed possible is seen in a fuller sentence such as You met them in the cafe because you had time, and we did so in the pub. In this case, the preferred reading of did so is that it indeed simultaneously stands in for both met them and because we had time.

One-substitution[edit]

The one-substitution test replaces the test string with the indefinite pronoun one or ones.[9] If the result is acceptable, then the test string is deemed a constituent. Since one is a type of pronoun, one-substitution is only of value when probing the structure of noun phrases. In this regard, the test sentence from above is expanded in order to better illustrate the manner in which one-substitution is generally employed:

-

- Drunks could put off the loyal customers around here who we rely on.

- (a) Drunks could put off the loyal ones around here who we rely on. (ones = customers)

- (b) Drunks could put off the ones around here who we rely on. (ones = loyal customers)

- (c) Drunks could put off the loyal ones who we rely on. (ones = customers around here)

- (d) Drunks could put off the ones who we rely on. (ones = loyal customers around here)

- (e) Drunks could put off the loyal ones. (ones = customers around here who we rely on)

These examples suggest that customers, loyal customers, customers around here, loyal customers around here, and customers around here who we rely on are constituents in the test sentence. Some have pointed to a problem associated with the one-substitution in this area, however. This problem is that it is impossible to produce a single constituent structure of the noun phrase the loyal customers around here who we rely on that could simultaneous view all of the indicated strings as constituents.[10] Another problem that has been pointed out concerning the one-substitution as a test for constituents is the fact that it at times suggests that non-string word combinations are constituents,[11] e.g.

-

- (f) Drunks would put off the ones around here. (ones = loyal customers who we rely on)

The word combination consisting of both loyal customers and who we rely on is discontinuous in the test sentence, a fact that should motivate one to generally question the value of one-substitution as a test for constituents.

Answer fragments (answer ellipsis, question test, standalone test)[edit]

The answer fragment test involves forming a question that contains a single wh-word (e.g. who, what, where, etc.). If the test string can then appear alone as the answer to such a question, then it is likely a constituent in the test sentence:[12]

-

- Drunks could put off the customers.

- (a) Who could put off the customers? — Drunks.

- (b) Who could drunks put off? — The customers.

- (c) What would drunks do? — Put off the customers.

These examples suggest that Drunks, the customers, and put off the customers are constituents in the test sentence. The answer fragment test is like most of the other tests for constituents in that it does not identify sub-phrasal strings as constituents:

-

- (d) What about putting off the customers? — *Could.

- (e) What could drunks do about the customers? — *Put.

- (f) *What could drunks do about putting the customers? — *Off.

- (g) *Who could drunks put off the? — *Customers.

These answer fragments are all grammatically unacceptable, suggesting that could, put, off, and customers are not constituents. Note as well that the latter two questions themselves are ungrammatical. It is apparently often impossible to form the question in a way that could successfully elicit the indicated strings as answer fragments. The conclusion, then, is that the answer fragment test is like most of the other tests in that it fails to identify sub-phrasal strings as constituents.

Clefting[edit]

Clefting involves placing the test string X within the structure beginning with It is/was: It was X that….[13] The test string appears as the pivot of the cleft sentence:

-

- Drunks could put off the customers.

- (a) It is drunks that could put off the customers.

- (b) It is the customers that drunks could put off.

- (c) ??It is put off the customers that drunks could do.

These examples suggest that Drunks and the customers are constituents in the test sentence. Example c is of dubious acceptability, suggesting that put off the customers may not be constituent in the test string. Clefting is like most of the other tests for constituents in that it fails to identify most individual words as constituents:

-

- (d) *It is could that drunks put off the customers.

- (e) *It is put that drunks could off the customers.

- (f) *It is off that drunks could put the customers.

- (g) *It is the that drunks could put off customers.

- (h) *It is customers that drunks could put off the.

The examples suggest that the each of the individual words could, put, off, the, and customers are not constituents, contrary to what most theories of syntax assume. In this respect, clefting is like many of the other tests for constituents in that it only succeeds at identifying certain phrasal strings as constituents.

VP-ellipsis (verb phrase ellipsis)[edit]

The VP-ellipsis test checks to see which strings containing one or more predicative elements (usually verbs) can be elided from a sentence. Strings that can be elided are deemed constituents:[14] The symbol ∅ is used in the following examples to mark the position of ellipsis:

-

- Beggars could immediately put off the customers when they arrive, and

- (a) *drunks could immediately also ∅ the customers when they arrive. (∅ = put off)

- (b) ?drunks could immediately also ∅ when they arrive. (∅ = put off the customers)

- (c) drunks could also ∅ when they arrive. (∅ = immediately put off the customers)

- (d) drunks could immediately also ∅. (∅ = put off the customers when they arrive)

- (e) drunks could also ∅. (∅ = immediately put off the customers when they arrive)

These examples suggest that put off is not a constituent in the test sentence, but that immediately put off the customers, put off the customers when they arrive, and immediately put off the customers when they arrive are constituents. Concerning the string put off the customers in (b), marginal acceptability makes it difficult to draw a conclusion about put off the customers.

There are various difficulties associated with this test. The first of these is that it can identify too many constituents, such as in this case here where it is impossible to produce a single constituent structure that could simultaneously view each of the three acceptable examples (c-e) as having elided a constituent. Another problem is that the test can at times suggest that a discontinuous word combination is a constituent, e.g.:

-

- (f) Frank will help tomorrow in the office, and Susan will ∅ today. (∅ = help…in the office)

In this case, it appears as though the elided material corresponds to the discontinuous word combination including help and in the office.

Pseudoclefting[edit]

Pseudoclefting is similar to clefting in that it puts emphasis on a certain phrase in a sentence. There are two variants of the pseudocleft test. One variant inserts the test string X in a sentence starting with a free relative clause: What…..is/are X; the other variant inserts X at the start of the sentence followed by the it/are and then the free relative clause: X is/are what/who… Only the latter of these two variants is illustrated here.[15]

-

- Drunks would put off the customers.

- (a) Drunks are who could put off the customers.

- (b) The customers are who drunks could put off.

- (c) Put off the customers is what drunks could do.

These examples suggest that Drunks, the customers, and put off the customers are constituents in the test sentence. Pseudoclefting fails to identify most individual words as constituents:

-

- (d) *Could is what drunks put off the customers.

- (e) *Put is what drunks could off the customers.

- (f) *Off is what drunks could put the customers.

- (g) *The is who drunks could put off customers.

- (h) *Customers is who drunks could put off the.

The pseudoclefting test is hence like most of the other tests insofar as it identifies phrasal strings as constituents, but does not suggest that sub-phrasal strings are constituents.

Passivization[edit]

Passivization involves changing an active sentence to a passive sentence, or vice versa. The object of the active sentence is changed to the subject of the corresponding passive sentence:[16]

-

- (a) Drunks could put off the customers.

- (b) The customers could be put off by drunks.

The fact that sentence (b), the passive sentence, is acceptable, suggests that Drunks and the customers are constituents in sentence (a). The passivization test used in this manner is only capable of identifying subject and object words, phrases, and clauses as constituents. It does not help identify other phrasal or sub-phrasal strings as constituents. In this respect, the value of passivization as test for constituents is very limited.

Omission (deletion)[edit]

Omission checks whether the target string can be omitted without influencing the grammaticality of the sentence. In most cases, local and temporal adverbials, attributive modifiers, and optional complements can be safely omitted and thus qualify as constituents.[17]

-

- Drunks could put off the customers.

- (a) Drunks could put off customers. (the has been omitted.)

This sentence suggests that the definite article the is a constituent in the test sentence. Regarding the test sentence, however, the omission test is very limited in its ability to identify constituents, since the strings that one wants to check do not appear optionally. Therefore, the test sentence is adapted to better illustrate the omission test:

-

- The obnoxious drunks could immediately put off the customers when they arrive.

- (b) The drunks could immediately put off the customers when they arrive. (obnoxious has been successfully omitted.)

- (c) The obnoxious drunks could put off the customers when they arrive. (immediately has been successfully omitted.)

- (d) The obnoxious drunks could put off the customers. (when they arrive has been successfully omitted.)

The ability to omit obnoxious, immediately, and when they arrive suggests that these strings are constituents in the test sentence. Omission used in this manner is of limited applicability, since it is incapable of identifying any constituent that appears obligatorily. Hence there are many target strings that most accounts of sentence structure take to be constituents but that fail the omission test because these constituents appear obligatorily, such as subject phrases.

Intrusion[edit]

Intrusion probes sentence structure by having an adverb «intrude» into parts of the sentence. The idea is that the strings on either side of the adverb are constituents.[18]

-

- Drunks could put off the customers.

- (a) Drunks definitely could put off the customers.

- (b) Drunks could definitely put off the customers.

- (c) *Drunks could put definitely off the customers.

- (d) *Drunks could put off definitely the customers.

- (e) *Drunks could put off the definitely customers.

Example (a) suggests that Drunks and could put off the customers are constituents. Example (b) suggests that Drunks could and put off the customers are constituents. The combination of (a) and (b) suggest in addition that could is a constituent. Sentence (c) suggests that Drunks could put and off the customers are not constituents. Example (d) suggests that Drunks could put off and the customers are not constituents. And example (e) suggests that Drunks could put off the and customers are not constituents.

Those that employ the intrusion test usually use a modal adverb like definitely. This aspect of the test is problematic, though, since the results of the test can vary based upon the choice of adverb. For instance, manner adverbs distribute differently than modal adverbs and will hence suggest a distinct constituent structure from that suggested by modal adverbs.

Wh-fronting[edit]

Wh-fronting checks to see if the test string can be fronted as a wh-word.[19] This test is similar to the answer fragment test insofar it employs just the first half of that test, disregarding the potential answer to the question.

-

- Drunks would put off the customers.

- (a) Who would put off the customers? (Who ↔ Drunks)

- (b) Who would drunks put off? (Who ↔ the customers)

- (c) What would drunks do? (What…do ↔ put off the customers)

These examples suggest that Drunks, the customers, and put off the customers are constituents in the test sentence. Wh-fronting is like a number of the other tests in that it fails to identify many subphrasal strings as constituents:

-

- (d) *Do what drunks put off the customers? (Do what ↔ would)

- (e) *Do what drunks would off the customers? (Do what ↔ put)

- (f) *What would drunks put the customers? (What ↔ off)

- (g) *What would drunks put off customers? (What ↔ the)

- (h) *Who would drunks put off the? (Who ↔ customers)

These examples demonstrate a lack of evidence for viewing the individual words would, put, off, the, and customers as constituents.

General substitution[edit]

The general substitution test replaces the test string with some other word or phrase.[20] It is similar to proform substitution, the only difference being that the replacement word or phrase is not a proform, e.g.

-

- Drunks could put off the customers.

- (a) Beggars could put off the customers. (Beggars ↔ Drunks)

- (b) Drunks could put off our guests. (our guests ↔ the customers)

- (c) Drunks would put off the customers. (would ↔ could)

These examples suggest that the strings Drunks, the customers, and could are constituents in the test sentence. There is a major problem with this test, for it is easily possible to find a replacement word for strings that the other tests suggest are clearly not constituents, e.g.

-

- (d) Drunks piss off the customers. (piss ↔ could put)

- (e) Beggars put off the customers. (Beggars ↔ Drunks could)

- (f) Drunks like customers. (like ↔ could put off the)

These examples suggest that could put, Drunks could, and could put of the are constituents in the test sentence. This is contrary to what the other tests reveal and to what most theories of sentence structure assume. The value of general substitution as test for constituents is therefore suspect. It is like the coordination test in that it suggests that too many strings are constituents.

Right node raising (RNR)[edit]

Right node raising, abbreviated as RNR, is a test that isolates the test string on the right side of a coordinate structure.[21] The assumption is that only constituents can be shared by the conjuncts of a coordinate structure, e.g.

-

- Drunks could put off the customers.

- (a) [Drunks] and [beggars] could put off the customers.

- (b) [Drunks could], and [they probably would], put off the customers.

- (c) [Drunks could approach] and [they would then put off] the customers.

These examples suggest that could put off the customers, put off the customers, and the customers are constituents in the test sentence. There are two problems with the RNR diagnostic as a test for constituents. The first is that it is limited in its applicability, since it is only capable of identifying strings as constituents if they appear on the right side of the test sentence. The second is that it can suggest strings to be constituents that most of the other tests suggest are not constituents. To illustrate this point, a different example must be used:

-

- Frank has given his bicycle to us to use if need be.

- (d) [Frank has offered], and [Susan has already loaned], their bicycles to us to use if need be.

- (e) [Frank has offered his bicycle] and [Susan has already loaned her bicycle] to us to use if need be.

- (f) [Frank has offered his bicycle to us] and [Susan has already loaned her bicycle to us] to use if need be.

These examples suggest that their bicycles (his bicycle) to us to use if need be, to us to use if need be, and to use if need be are constituents in the test sentence. Most theories of syntax do not view these strings as constituents, and more importantly, most of the other tests suggest that they are not constituents.

In short, these tests are not taken for granted because a constituent may pass one test and fail to pass many others. We need to consult our intuitive thinking when judging the constituency of any set of words.

Other languages[edit]

A word of caution is warranted concerning the tests for constituents as just discussed above. These tests are found in textbooks on linguistics and syntax that are written mainly with the syntax of English in mind, and the examples that are discussed are mainly from English. The tests may or may not be valid and useful when probing the constituent structure of other languages. Ideally, a battery of tests for constituents can and should be developed for each language, catered to the idiosyncrasies of the language at hand.

Competing theories[edit]

Constituent structure analyses of sentences are a central concern for theories of syntax. The one theory can produce an analysis of constituent structure that is quite unlike the next. This point is evident with the two tree diagrams above of the sentence Drunks could put off the customers, where the dependency grammar analysis of constituent structure looks very much unlike the phrase structure analysis. The crucial difference across the two analyses is that the phrase structure analysis views every individual word as a constituent by default, whereas the dependency grammar analysis sees only those individual words as constituents that do not dominate other words. Phrase structure grammars therefore acknowledge many more constituents than dependency grammars.

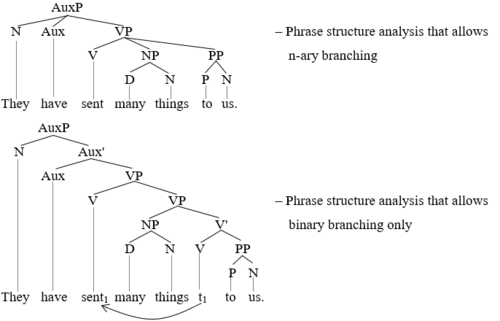

A second example further illustrates this point (D = determiner, N = noun, NP = noun phrase, Pa = particle, S = sentence, V = Verb, V’ = verb-bar, VP = verb phrase):

The dependency grammar tree shows five words and word combinations as constituents: who, these, us, these diagrams, and show us. The phrase structure tree, in contrast, shows nine words and word combinations as constituents: what, do, these, diagrams, show, us, these diagrams, show us, and do these diagrams show us. The two diagrams thus disagree concerning the status of do, diagrams, show, and do these diagrams show us, the phrase structure diagram showing them as constituents and the dependency grammar diagram showing them as non-constituents. To determine which analysis is more plausible, one turns to the tests for constituents discussed above.[22]

Within phrase structure grammars, views about of constituent structure can also vary significantly. Many modern phrase structure grammars assume that syntactic branching is always binary, that is, each greater constituent is necessarily broken down into two lesser constituents. More dated phrase structures analyses are, however, more likely to allow n-ary branching, that is, each greater constituent can be broken down into one, two, or more lesser constituents. The next two trees illustrate the distinction (Aux = auxiliary verb, AuxP = auxiliary verb phrase, Aux’ = Aux-bar, D = determiner, N = noun, NP = noun phrase, P = preposition, PP = prepositional phrase, Pa = particle, S = sentence, t = trace, V = Verb, V’ = verb-bar, VP = verb phrase):

The details in the second diagram here not crucial to the point at hand. This point is that the all branching there is strictly binary, whereas in the first tree diagram ternary branching is present twice, for the AuxP and for the VP. Observe in this regard that strictly binary branching analyses increase the number of (overt) constituents to what is possible. The word combinations have sent many things to us and many things to us are shown as constituents in the second tree diagram but not in the first. Which of these two analyses is better is again at least in part a matter of what the tests for constituents can reveal.

See also[edit]

- Catena (linguistics)

- Finite verb

- Non-finite verb

Notes[edit]

- ^ Osborne (2018) provides a detailed and comprehensive discussion of tests for constituents, having surveyed dozens of textbooks on the topic. Osborne’s article is available here: Tests for constituents: What they really reveal about the nature of syntactic structure Archived 2018-11-27 at the Wayback Machine. See also Osborne (2019: 2-6, 73-94).

- ^ This one sentence has been adapted slightly from Radford 1988:91. Radford uses this sentence to introduce and illustrate sentence structure and tests for constituents that identify this structure.

- ^ Two prominent sources on dependency grammar are Tesnière (1959) and Ágel, et al. (2003/2006).

- ^ For examples of coordination used as a test for constituent structure, see Baker 1978:269–76; Radford 1981:59–60; Atkinson et al. 1982:172–3; Radford 1988:75–8; Akmajian et al. 1990:152–3; Borsley 1991:25–30; Cowper 1992:34–7; Napoli 1993:159–61; Ouhalla 1994:17; Radford 1997:104–7; Burton–Roberts 1997:66–70; Haegeman and Guéron 1999:27; Fromkin 2000:160–2; Lasnik 2000:11; Lobeck 2000:61–3; Börjars and Burridge 2001:27–31; Huddleston and Pullum 2002:1348–9; van Valin 2001:113–4; Poole 2002:31–2; Adger 2003:125–6; Sag et al. 2003:30; Radford 2004:70–1; Kroeger 2005:91, 218–9; Tallerman 2005:144–6; Haegeman 2006:89–92; Payne 2006:162; Kim and Sells 2008:22; Carnie 2010:115–6, 125; Quirk et al. 2010:46–7; Sobin 2011:31–2; Carnie 2013:99–100; Sportiche et al. 2014:62–8; Müller 2016:10, 16–7

- ^ The problems with coordination as a test for constituent structure have been pointed out in numerous places in the literature. See for instance Baker 1989:425; McCawley 1998:63; Adger 2003:125; Payne 2006:162; Kim and Sells 2008:22; Carnie 2010:21; Carnie 2013:100; Sportiche et al. 2014:66; Müller 2016:16-7.

- ^ For examples of pro-form substitution used as a test for constituents, see Allerton 1979:113–4; Radford 1981:63–6; Atkinson et al 1982:173–4; Radford 1988:78–81, 98–9; Thomas 1993:10–12; Napoli 1993:168; Ouhalla 1994:19; Radford 1997:109; Haegeman and Guéron 1999:46; Fromkin 2000:155–8; Lasnik 2000:9–10; Lobeck 2000:53–7; Börjars and Burridge 2001:24–5; van Valin 2001: 111–2; Poole 2002:29–31; Adger 2003:63; Radford 2004:71; Tallerman 2005:140–2; Haegeman 2006:74–9; Moravcsik 2006:123; Kim and Sells 2008:21–2; Culicover 2009:81; Carnie 2010:19–20; Quirk et al. 2010:75–7; Miller 2011:54–5; Sobin 2011:32; Carnie 2013:98; Denham and Lobeck 2013:262–5; Sportiche et al. 2014:50; Müller 2016:8.

- ^ For examples of topicalization used as a test for constituents, see Allerton 1979:114; Atkinson et al. 1982:171–2; Radford 1988:95; Borsley 1991:24; Haegeman 1991:27; Napoli 1993:422; Ouhalla 1994:20; Burton–Roberts 1997:17–8; Haegeman and Guéron 1999:46; Fromkin 2000:151; Lasnik 2000:10; Lobeck 2000:47–9; Börjars and Burridge 2001:26; van Valin 2001:112; Poole 2002:32; Adger 2003:65; Sag et al. 2003:33; Radford 2004:72; Kroeger 2005:31; Downing and Locke 2006:10; Haegeman 2006:79; Payne 2006:160; Culicover 2009:84; Quirk et al. 2010:51; Miller 2011:55; Sobin 2011:31; Sportiche et al. 2014:68; Müller 2016:10.

- ^ For examples of the use of do-so-substitution as a test for constituents, see Baker 1978:261–8; Aarts and Aarts 1982:56, Atkinson et al. 1982:174; Borsley 1991:63; Haegeman 1991:79–82; Cowper 1992:31; Napoli 1993:423–5; Burton–Roberts 1997:104–7; Haegeman and Guéron 1999:74; Fromkin 2000:156–7; van Valin 2001:123, 127; Poole 2002:41–3; Tallerman 2005:130–1, 141; Haegeman 2006:75–6; Payne 2006:162; Culicover 2009:81; Carnie 2010:115–6; Quirk et al. 2010:76, 82; Miller 2011:54–5; Sobin 2011:33; Carnie 2013:169–70; Denham and Lobeck 2013:265; Sportiche et al. 2014:61.

- ^ For examples of one-substitution used as a test for constituents, see Baker 1978:327–40, 413–25; Radford 1981:92, 96–100; Aarts and Aarts 1982:57; Haegeman 1991: 26, 88–9; Cowper 1992:26; Napoli 1993:423–5; Burton–Roberts 1997:182–9; McCawley 1998:183; Haegeman and Guéron 1999:75–6; Fromkin 2000: 157–8; van Valin 2001:122, 126, 128, Poole 2002:37–9; Adger 2003:63; Radford 2004:37; Kroeger 2005:97–8; Tallerman 2005:150; Haegeman 2006:109; Carnie 2010:114–5; Quirk et al. 2010:75; Carnie 2013:166–7; Sportiche et al. 2014:52, 57, 60.

- ^ Concerning the inability of a single constituent structure to simultaneously acknowledge all of the strings that one-substitution suggests are constituents, see Cowper 1992:30, Napoli 1993: 425, Burton-Roberts 1997: 187, and Carnie 2013: 190–2.

- ^ The fact that one-substitution at times suggests that non-string word combinations are constituents is illustrated and discussed by Culicover and Jackendoff 2005:136–9 and Goldberg and Michaelis 2017:4–6.

- ^ For examples of answer fragments used as a test for constituents, see Brown and Miller 1980:25; Radford 1981:72, 92; Radford 1988:91; Burton–Roberts 1997:15–8; Radford 1997:107; Börjars and Burridge 2001:25; Kroeger 2005:31; Tallerman 2005:125; Downing and Locke 2006:10; Haegeman 2006:82; Moravcsik 2006:123; Herbst and Schüler 2008:6–7; Kim and Sells 2008:20; Carnie 2010:18; Sobin 2011:31; Carnie 2013:98.

- ^ For examples of clefting used as a test for constituents, see Brown and Miller 1980:25; Radford 1981:109–10; Aarts and Aarts 1982:97–8; Akmajian et al. 1990:150; Borsley 1991:23; Napoli 1993:148; McCawley 1998:64; Haegeman and Guéron 1999:49; Börjars and Burridge 2001:27; Adger 2003:67; Sag et al. 2003:33; Tallerman 2005:127; Downing and Locke 2006:10; Haegeman 2006:85; Kim and Sells 2008:19; Carnie 2013: 98; Sportiche et al. 2014:70.

- ^ For examples of VP-ellipsis used to test constituent structure, see Radford 1981:67, 1988:101; Napoli 1993:424; Ouhalla 1994:20; Radford 1997:110; McCawley 1998:67; Fromkin 2000:158; Adger 2003:65; Kroeger 2005:82; Tallerman 2005:141; Haegeman 2006:84–5; Payne 2006:163; Culicover 2009:80; Denham and Lobeck 2013:273–4; Sportiche et al. 2014:58–60.

- ^ For examples of pseudoclefting used as a test for constituents, see Brown and Miller 1980:25; Aarts and Aarts 1982:98; Borsley 1991:24; Napoli 1993:168; McCawley 1998:64; Haegeman and Guéron 1999:50; Kroeger 2005:82; Downing and Locke 2006:10; Haegeman 2006:88; Payne 2006:160; Culicover 2009:89; Miller 2011:56; Carnie 2013:99; Sportiche et al. 2014:71.

- ^ For examples of passivization used as a test for constituents, see Brown and Miller 1980:25; Borsley 1991:24; Thomas 1993:10; Lobeck 2000:49–50; Downing and Locke 2006:10; Carnie 2010:21; Sobin 2011:30; Carnie 2013:99; Denham and Lobeck 2013:277.

- ^ For examples of omission used as a test for constituents, see Allerton 1979: 113–9; Aarts and Aarts 1982: 60–1, 65–7; Burton–Roberts 1997: 14–5; Börjars and Burridge 2001: 33–4; Payne 2006: 163–5; Carnie 2010: 19; Hudson 2010: 147; Quirk et al. 2010: 41, 51, 61; Miller 2011: 54; Sobin 2011: 33).

- ^ For examples of intrusion used as a test for constituents, see Radford 1981:60–2; 1988:93; McCawley 1998:68–70; Fromkin 2000:147–51; Börjars and Burridge 2001:34; Huddleston and Pullum 2002:21; Moravcsik 2006:123; Payne 2006:162.

- ^ For examples of wh-fronting used as a test for constituents, see Radford 1981:108; Haegeman 1991:28; Haegeman and Guéron 1999:46–7; Lobeck 2000:57–9; Payne 2006:160; Culicover 2009:90–1; Denham and Lobeck 2013:279–81; Sportiche et al. 2014:58–60; Müller 2016:9.

- ^ For examples of the general substitution test, see Allerton 1979: 113; Brown and Miller 1980: 38; Aarts and Aarts 1982: 11; Radford 1988: 89–91; Moravcsik 2006: 123–4; Culicover 2009: 37; Quirk et al. 2010: 41; Müller 2016: 7–8.

- ^ For examples of RNR used as test for constituents, see Radford 1988: 77–8, 97; Radford 1997: 106; McCawley 1998: 60–1; Haegeman and Guéron 1999: 52, 77; Sportiche et al. 2014: 67–8.

- ^ For a comparison of these two competing views of constituent structure, see Osborne (2019:73-94).

References[edit]

- Adger, D. 2003. Core syntax: A minimalist approach. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

- Ágel, V., L. Eichinger, H.-W. Eroms, P. Hellwig, H. Heringer, and H. Lobin (eds.) 2003/6. Dependency and valency: An international handbook of contemporary research. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter.

- Akmajian, A., R. Demers, A. Farmer and R. Harnish. 2001. Linguistics: An introduction to language and communication, 5th edn. Cambridge: MIT Press.

- Allerton, D. 1979. Essentials of grammatical theory: A consensus view of syntax and morphology. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul.

- Aarts, Flor and Jan Aarts. 1982. English syntactic structures: Functions & categories in sentence analysis. Oxford, UK: Pergamon Press and Bohn: Scheltema & Holkema.

- Atkinson, M., D. Kilby, and Iggy Roca. 1982. Foundations of general linguistics, second edition. London: Unwin Hyman.

- Baker, C. L. 1978. Introduction to generative transformational grammar. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

- Baker, C. L. 1988. English syntax. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

- Börjars, K. and K. Burridge. 2001. Introducing English grammar. London: Arnold.

- Borsley, R. 1991. Syntactic theory: A unified approach. London: Edward Arnold.

- Brinker, K. 1972. Konstituentengrammatik und operationale Satzgliedanalyse: Methodenkritische Untersuchungen zur Syntax des einfachen deutschen Satzes. Frankfurt a. M.: Athenäum.

- Brown, K. and J. Miller 1980. Syntax: A linguistic introduction to sentence structure. London: Hutchinson.

- Burton-Roberts, N. 1997. Analysing sentences: An introduction to English syntax. 2nd Edition. Longman.

- Carnie, A. 2002. Syntax: A generative introduction. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Carnie, A. 2010. Constituent Structure. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Carnie, A. 2013. Syntax: A generative introduction. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Cowper, E. 1992. A concise introduction to syntactic theory: The government-binding approach. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

- Culicover, P. 2009. Natural language syntax. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

- Culicover, P. and . Jackendoff. 2005. Simpler syntax. New York: Oxford University

- Dalrymple, M. 2001. Lexical functional grammar. Syntax and semantics 34. San Diego: Academic Press.

- Denham, K. and A. Lobeck. 2013. Linguistics for everyone: An introduction. Boston: Wadsworth Cengage Learning.

- Downing, A. and P. Locke. 2006. English grammar: A university course, 2nd edition. London: Routledge.

- Fromkin, V. A. (ed.). 2000. An introduction to linguistic theory. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing.

- Goldberg, A. and L. Michaelis. 2017. One among many: Anaphoric one and its relationship with numeral one. Cognitive Science, 41.S2: 233–258.

- Haegeman, L. 1991. Introduction to Government and Binding Theory. Oxford, UK: Blackwell.

- Haegeman, L. 2006. Thinking syntactically: A guide to argumentation and analysis. Malden, MA: Blackwell.

- Haegeman, L. and J. Guéron 1999. English grammar: A generative perspective. Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

- Herbst, T. and S. Schüller. 2008. Introduction to syntactic analysis: A valency approach. Tübingen: Narr.

- Huddleston, R. and G. Pullum. 2002. The Cambridge grammar of the English language. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Hudson, R. 2010. An introduction to Word Grammar. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Jacobson, P. 1996. Constituent structure. In Concise encyclopedia of syntactic theories. Cambridge: Pergamon.

- Kim, J. and P. Sells. 2008. English syntax: An introduction. Stanford: CSLI Publications.

- Kroeger, P. 2005. Analyzing grammar: An introduction. Cambridge University Press.

- Lasnik, H. 2000. Syntactic structures revisited: Contemporary lectures on classic transformational theory. Cambridge: MIT Press.

- Lobeck, A. 2000. Discovering grammar: An introduction to English sentence structure. New York: Oxford University Press.

- McCawley, J. 1998. The syntactic phenomena of English, 2nd edn. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Miller, J. 2011. A critical introduction to syntax. London: Continuum.

- Moravcsik, E. 2006. An introduction to syntax: Fundamentals of syntactic analysis. London: Continuum.

- Müller, Stefan. 2016. Grammatical theory: From transformational grammar to constraint-based approaches (Textbooks in Language Sciences 1). Berlin: Language Science Press.

- Napoli, D. 1993. Syntax: Theory and problems. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Nerbonne, J. 1994. Partial verb phrases and spurious ambiguities. In: J. Nerbonne, K. Netter and C. Pollard (eds.), German in Head-Driven Phrase Structure Grammar, CSLI Lecture Notes Number 46. 109–150. Stanford: CSLI Publications.

- Osborne, Timothy. 2018. Tests for constituents: What they really reveal about the nature of syntactic structure. Language Under Discussion 5, 1, 1–41.

- Osborne, T. 2019. A Dependency Grammar of English: An Introduction and Beyond. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. https://doi.org/10.1075/z.224

- Ouhalla, J. 1994. Introducing transformational grammar: From rules to principles and parameters. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Payne, T. 2006. Exploring language structure: A student’s guide. New York: Cam-bridge University Press.

- Poole, G. 2002. Syntactic theory. New York: Palgrave.

- Quirk, R., S. Greenbaum, G. Leech, and J. Svartvik. 2010. A com-prehensive grammar of the English language. Dorling Kindersley: Pearson.

- Radford, A. 1981. Transformational syntax: A student’s guide to Chomsky’s Ex-tended Standard Theory. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Radford, A. 1988. Transformational grammar: A first course. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Radford, A. 1997. Syntactic theory and the structure of English: A minimalist approach. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Radford, A. 2004. English syntax: An introduction. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Sag, I., T. Wasow, and E. Bender. 2003. Syntactic theory: A formal introduction, 2nd edition. Stanford: CSLI Publications.

- Santorini, B. and A. Kroch 2000. The syntax of natural language: An online introduction using the trees program. Available at (accessed on March 14, 2011): http://www.ling.upenn.edu/~beatrice/syntax-textbook/00/index.html.

- Sobin, N. 2011. Syntactic analysis: The basics. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Sportiche, D., H. Koopman, and Edward Stabler. 2014. An introduction to syntactic analysis. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Tallerman, M. 2005. Understanding syntax. London: Arnold.

- Tesnière, L. 1959. Éléments de syntaxe structurale. Paris: Klincksieck.

- van Valin, R. 2001. An introduction to syntax. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

MORPHEMIC STRUCTURE OF THE

WORD

The

morphological system of language reveals its properties through the

morphemic structure of the word. Morphology as part of the

grammatical theory faces the two segmental units: the morpheme and

the word. The morpheme is identified as part of the word, the

functions of the morpheme are effected only as the corresponding

constituent functions of the word as a whole. For instance, the form

of the verbal past tense is built up by means of the dental

grammatical suffix: train-ed

[-d]; publish-ed

[-t], meditate-ed

[-id].

The

morpheme is

a meaningful segmental component of the word; the morpheme is formed

by phonemes; as a meaningful component of the word it is elementary

(i.e. indivisible into smaller segments as regards its significative

function).

The

word is

a nominative unit of language; it is formed by morphemes; it enters

the lexicon of language as its elementary component (i.e. a component

indivisible into smaller segments as regards its nominative

function). Together with other nominative units the word is used for

the formation of the sentence – a unit of information in the

communication process.

In

traditional grammar the study of the morphemic structure of the word

was conducted in the light of the

two basic criteria: positional criterion

(the location of the marginal morphemes in relation to the central

ones) and

semantic or functional criterion

(the correlative contribution of the morphemes to the general meaning

of the word). The combination of these two criteria in an integral

description has led to the rational classification of morphemes that

is widely used both in research linguistic work and in practical

language teaching.

In accord with the

traditional classification, morphemes are divided into root-morphemes

(roots) and affixal morphemes (affixes). The roots express the

concrete, “material” part of the meaning of the word, while the

affixes express the specificational part of the meaning of the word;

the specifications being of lexico-semantic and grammatico-semantic

character.

The roots of notional words

are classical lexical morphemes.

The affixal morphemes include

prefixes, affixes, and inflexions. Of these, prefixes and lexical

suffixes have word-building functions, together with the root they

form the stem of the word; inflexions (grammatical suffixes) express

different morphological categories.

The root is obligatory for

any word, while affixes are not obligatory. Therefore one and the

same morphemic segment of functional status, depending on various

morphemic environment, can be used now as an affix, now as a root,

e.g.:

Out

– a root-word (preposition, adverb, verbal postposition, adjective,

noun, verb);

Throughout

–

a composite word in which

–out serves

as one of the roots;

Outing –

a two-morpheme word in which

out- is

a root, and –ing

is a suffix;

Outlook,

outline –

words in which out-

serves

as a prefix;

Look-out,

time-out –

words in which

–out serves

as a suffix.

As

a result of the distributional analysis

(the analysis of the environment of a unit), different types of

morphemes have been discriminated.

On the

basis of the degree

of self-dependence,

“free” morphemes and “bound” morphemes are distinguished.

Bound morphemes cannot form words by themselves, they are identified

only as component segmental parts of words. As different from this,

free morphemes can build up words by themselves, i.e. can be used

“freely”. For instance, in the word handful

the root hand

is

a free morpheme, while the suffix –ful

is a bound morpheme.

On the

basis of formal

presentation, “overt”

morphemes and “covert” morphemes are distinguished. Overt

morphemes are genuine, explicit morphemes building up words; the

covert morpheme is identified as a contrastive absence of morpheme

expressing a certain function. The notion of covert morpheme

coincides with the notion of zero morpheme in the oppositional

description of grammatical categories. For instance, the word-form

clocks

consists

of two overt morphemes: one lexical (root) and one grammatical

expressing the plural. The one- morpheme word-form clock,

since it expresses the singular, is also considered as consisting of

two morphemes, i.e. of the overt root and the covert (implicit)

grammatical suffix of the singular. The usual symbol for the covert

morpheme employed by linguists is the sign of the empty set: Ø.

On the

basis of segmental

relation, “segmental”

morphemes and “supra-segmental” morphemes are distinguished.

Interpreted as supra-segmental morphemes are intonation contours,

accents, pauses.

On the

basis of grammatical

alternation, “additive”

morphemes and “replacive” morphemes are distinguished.

Interpreted as additive morphemes are outer grammatical suffixes,

since, as a rule, they are opposed to the absence of morphemes in

grammatical alternation, e.g. look + ed, small + er, etc. In

distinction to these, the root phonemes pf grammatical interchange

are considered as replacive morphemes, since they replace one another

in the paradigmatic forms, e.g. dr-i-ve – dr-o-ve – dr-i-ven;

m-a-n – m-e-n, etc.

On the

basis of linear

characteristic, “continuous”

(or “linear”) morphemes and “discontinuous” morphemes are

distinguished. By the discontinuous morpheme, opposed to the common,

i.e. uninterruptedly expressed, continuous morpheme, a two-element

grammatical unit is meant which is identified in the analytical

grammatical form comprising an auxiliary word and a grammatical

suffix. These two elements, as it were, embed the notional stem;

hence, they are symbolically represented as follows:

Be …

ing –

for the continuous verb forms (e.g. is going);

Have …

en –

for the perfect verb forms (e.g. has gone);

Be …

en –

for the passive verb forms (e.g. is taken).

It is easy to see that the

notion of morpheme applied to the analytical form of the word

violates the principle of the identification of morpheme as an

elementary meaningful segment: the analytical “framing” consists

of two meaningful segments, i.e. of two different morphemes. On the

other hand, the general notion “discontinuous constituent” (or

unit) is quite rational and can be helpfully used in linguistic

description in its proper place.

3

Соседние файлы в предмете [НЕСОРТИРОВАННОЕ]

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

WORD STRUCTURE IN MODERN ENGLISH

I. The morphological structure of a word. Morphemes. Types of morphemes. Allomorphs.

II. Structural types of words.

III. Principles of morphemic analysis.

IV. Derivational level of analysis. Stems. Types of stems. Derivational types of words.

I. The morphological structure of a word. Morphemes. Types of Morphemes. Allomorphs.

There are two levels of approach to the study of word- structure: the level of morphemic analysis and the level of derivational or word-formation analysis.

Word is the principal and basic unit of the language system, the largest on the morphologic and the smallest on the syntactic plane of linguistic analysis.

It has been universally acknowledged that a great many words have a composite nature and are made up of morphemes, the basic units on the morphemic level, which are defined as the smallest indivisible two-facet language units.

The term morpheme is derived from Greek morphe “form ”+ -eme. The Greek suffix –eme has been adopted by linguistic to denote the smallest unit or the minimum distinctive feature.

The morpheme is the smallest meaningful unit of form. A form in these cases a recurring discrete unit of speech. Morphemes occur in speech only as constituent parts of words, not independently, although a word may consist of single morpheme. Even a cursory examination of the morphemic structure of English words reveals that they are composed of morphemes of different types: root-morphemes and affixational morphemes. Words that consist of a root and an affix are called derived words or derivatives and are produced by the process of word building known as affixation (or derivation).

The root-morpheme is the lexical nucleus of the word; it has a very general and abstract lexical meaning common to a set of semantically related words constituting one word-cluster, e.g. (to) teach, teacher, teaching. Besides the lexical meaning root-morphemes possess all other types of meaning proper to morphemes except the part-of-speech meaning which is not found in roots.

Affixational morphemes include inflectional affixes or inflections and derivational affixes. Inflections carry only grammatical meaning and are thus relevant only for the formation of word-forms. Derivational affixes are relevant for building various types of words. They are lexically always dependent on the root which they modify. They possess the same types of meaning as found in roots, but unlike root-morphemes most of them have the part-of-speech meaning which makes them structurally the important part of the word as they condition the lexico-grammatical class the word belongs to. Due to this component of their meaning the derivational affixes are classified into affixes building different parts of speech: nouns, verbs, adjectives or adverbs.

Roots and derivational affixes are generally easily distinguished and the difference between them is clearly felt as, e.g., in the words helpless, handy, blackness, Londoner, refill, etc.: the root-morphemes help-, hand-, black-, London-, fill-, are understood as the lexical centers of the words, and –less, -y, -ness, -er, re- are felt as morphemes dependent on these roots.

Distinction is also made of free and bound morphemes.

Free morphemes coincide with word-forms of independently functioning words. It is obvious that free morphemes can be found only among roots, so the morpheme boy- in the word boy is a free morpheme; in the word undesirable there is only one free morpheme desire-; the word pen-holder has two free morphemes pen- and hold-. It follows that bound morphemes are those that do not coincide with separate word- forms, consequently all derivational morphemes, such as –ness, -able, -er are bound. Root-morphemes may be both free and bound. The morphemes theor- in the words theory, theoretical, or horr- in the words horror, horrible, horrify; Angl- in Anglo-Saxon; Afr- in Afro-Asian are all bound roots as there are no identical word-forms.

It should also be noted that morphemes may have different phonemic shapes. In the word-cluster please , pleasing , pleasure , pleasant the phonemic shapes of the word stand in complementary distribution or in alternation with each other. All the representations of the given morpheme, that manifest alternation are called allomorphs/or morphemic variants/ of that morpheme.

The combining form allo- from Greek allos “other” is used in linguistic terminology to denote elements of a group whose members together consistute a structural unit of the language (allophones, allomorphs). Thus, for example, -ion/ -tion/ -sion/ -ation are the positional variants of the same suffix, they do not differ in meaning or function but show a slight difference in sound form depending on the final phoneme of the preceding stem. They are considered as variants of one and the same morpheme and called its allomorphs.

Allomorph is defined as a positional variant of a morpheme occurring in a specific environment and so characterized by complementary description.

Complementary distribution is said to take place, when two linguistic variants cannot appear in the same environment.

Different morphemes are characterized by contrastive distribution, i.e. if they occur in the same environment they signal different meanings. The suffixes –able and –ed, for instance, are different morphemes, not allomorphs, because adjectives in –able mean “ capable of beings”.

Allomorphs will also occur among prefixes. Their form then depends on the initials of the stem with which they will assimilate.

Two or more sound forms of a stem existing under conditions of complementary distribution may also be regarded as allomorphs, as, for instance, in long a: length n.

II. Structural types of words.

The morphological analysis of word- structure on the morphemic level aims at splitting the word into its constituent morphemes – the basic units at this level of analysis – and at determining their number and types. The four types (root words, derived words, compound, shortenings) represent the main structural types of Modern English words, and conversion, derivation and composition the most productive ways of word building.

According to the number of morphemes words can be classified into monomorphic and polymorphic. Monomorphic or root-words consist of only one root-morpheme, e.g. small, dog, make, give, etc. All polymorphic word fall into two subgroups: derived words and compound words – according to the number of root-morphemes they have. Derived words are composed of one root-morpheme and one or more derivational morphemes, e.g. acceptable, outdo, disagreeable, etc. Compound words are those which contain at least two root-morphemes, the number of derivational morphemes being insignificant. There can be both root- and derivational morphemes in compounds as in pen-holder, light-mindedness, or only root-morphemes as in lamp-shade, eye-ball, etc.

These structural types are not of equal importance. The clue to the correct understanding of their comparative value lies in a careful consideration of: 1)the importance of each type in the existing wordstock, and 2) their frequency value in actual speech. Frequency is by far the most important factor. According to the available word counts made in different parts of speech, we find that derived words numerically constitute the largest class of words in the existing wordstock; derived nouns comprise approximately 67% of the total number, adjectives about 86%, whereas compound nouns make about 15% and adjectives about 4%. Root words come to 18% in nouns, i.e. a trifle more than the number of compound words; adjectives root words come to approximately 12%.

But we cannot fail to perceive that root-words occupy a predominant place. In English, according to the recent frequency counts, about 60% of the total number of nouns and 62% of the total number of adjectives in current use are root-words. Of the total number of adjectives and nouns, derived words comprise about 38% and 37% respectively while compound words comprise an insignificant 2% in nouns and 0.2% in adjectives. Thus it is the root-words that constitute the foundation and the backbone of the vocabulary and that are of paramount importance in speech. It should also be mentioned that root words are characterized by a high degree of collocability and a complex variety of meanings in contrast with words of other structural types whose semantic structures are much poorer. Root- words also serve as parent forms for all types of derived and compound words.

III. Principles of morphemic analysis.

In most cases the morphemic structure of words is transparent enough and individual morphemes clearly stand out within the word. The segmentation of words is generally carried out according to the method of Immediate and Ultimate Constituents. This method is based on the binary principle, i.e. each stage of the procedure involves two components the word immediately breaks into. At each stage these two components are referred to as the Immediate Constituents. Each Immediate Constituent at the next stage of analysis is in turn broken into smaller meaningful elements. The analysis is completed when we arrive at constituents incapable of further division, i.e. morphemes. These are referred to Ultimate Constituents.

A synchronic morphological analysis is most effectively accomplished by the procedure known as the analysis into Immediate Constituents. ICs are the two meaningful parts forming a large linguistic unity.

The method is based on the fact that a word characterized by morphological divisibility is involved in certain structural correlations. To sum up: as we break the word we obtain at any level only ICs one of which is the stem of the given word. All the time the analysis is based on the patterns characteristic of the English vocabulary. As a pattern showing the interdependence of all the constituents segregated at various stages, we obtain the following formula:

un+ { [ ( gent- + -le ) + -man ] + -ly}

Breaking a word into its Immediate Constituents we observe in each cut the structural order of the constituents.

A diagram presenting the four cuts described looks as follows:

1. un- / gentlemanly

2. un- / gentleman / — ly

3. un- / gentle / — man / — ly

4. un- / gentl / — e / — man / — ly

A similar analysis on the word-formation level showing not only the morphemic constituents of the word but also the structural pattern on which it is built.

The analysis of word-structure at the morphemic level must proceed to the stage of Ultimate Constituents. For example, the noun friendliness is first segmented into the ICs: [frendlı-] recurring in the adjectives friendly-looking and friendly and [-nıs] found in a countless number of nouns, such as unhappiness, blackness, sameness, etc. the IC [-nıs] is at the same time an UC of the word, as it cannot be broken into any smaller elements possessing both sound-form and meaning. Any further division of –ness would give individual speech-sounds which denote nothing by themselves. The IC [frendlı-] is next broken into the ICs [-lı] and [frend-] which are both UCs of the word.

Morphemic analysis under the method of Ultimate Constituents may be carried out on the basis of two principles: the so-called root-principle and affix principle.

According to the affix principle the splitting of the word into its constituent morphemes is based on the identification of the affix within a set of words, e.g. the identification of the suffix –er leads to the segmentation of words singer, teacher, swimmer into the derivational morpheme – er and the roots teach- , sing-, drive-.

According to the root-principle, the segmentation of the word is based on the identification of the root-morpheme in a word-cluster, for example the identification of the root-morpheme agree- in the words agreeable, agreement, disagree.

As a rule, the application of these principles is sufficient for the morphemic segmentation of words.

However, the morphemic structure of words in a number of cases defies such analysis, as it is not always so transparent and simple as in the cases mentioned above. Sometimes not only the segmentation of words into morphemes, but the recognition of certain sound-clusters as morphemes become doubtful which naturally affects the classification of words. In words like retain, detain, contain or receive, deceive, conceive, perceive the sound-clusters [rı-], [dı-] seem to be singled quite easily, on the other hand, they undoubtedly have nothing in common with the phonetically identical prefixes re-, de- as found in words re-write, re-organize, de-organize, de-code. Moreover, neither the sound-cluster [rı-] or [dı-], nor the [-teın] or [-sı:v] possess any lexical or functional meaning of their own. Yet, these sound-clusters are felt as having a certain meaning because [rı-] distinguishes retain from detain and [-teın] distinguishes retain from receive.

It follows that all these sound-clusters have a differential and a certain distributional meaning as their order arrangement point to the affixal status of re-, de-, con-, per- and makes one understand —tain and –ceive as roots. The differential and distributional meanings seem to give sufficient ground to recognize these sound-clusters as morphemes, but as they lack lexical meaning of their own, they are set apart from all other types of morphemes and are known in linguistic literature as pseudo- morphemes. Pseudo- morphemes of the same kind are also encountered in words like rusty-fusty.

IV. Derivational level of analysis. Stems. Types of Stems. Derivational types of word.

The morphemic analysis of words only defines the constituent morphemes, determining their types and their meaning but does not reveal the hierarchy of the morphemes comprising the word. Words are no mere sum totals of morpheme, the latter reveal a definite, sometimes very complex interrelation. Morphemes are arranged according to certain rules, the arrangement differing in various types of words and particular groups within the same types. The pattern of morpheme arrangement underlies the classification of words into different types and enables one to understand how new words appear in the language. These relations within the word and the interrelations between different types and classes of words are known as derivative or word- formation relations.

The analysis of derivative relations aims at establishing a correlation between different types and the structural patterns words are built on. The basic unit at the derivational level is the stem.

The stem is defined as that part of the word which remains unchanged throughout its paradigm, thus the stem which appears in the paradigm (to) ask ( ), asks, asked, asking is ask-; thestem of the word singer ( ), singer’s, singers, singers’ is singer-. It is the stem of the word that takes the inflections which shape the word grammatically as one or another part of speech.

The structure of stems should be described in terms of IC’s analysis, which at this level aims at establishing the patterns of typical derivative relations within the stem and the derivative correlation between stems of different types.

There are three types of stems: simple, derived and compound.

Simple stems are semantically non-motivated and do not constitute a pattern on analogy with which new stems may be modeled. Simple stems are generally monomorphic and phonetically identical with the root morpheme. The derivational structure of stems does not always coincide with the result of morphemic analysis. Comparison proves that not all morphemes relevant at the morphemic level are relevant at the derivational level of analysis. It follows that bound morphemes and all types of pseudo- morphemes are irrelevant to the derivational structure of stems as they do not meet requirements of double opposition and derivative interrelations. So the stem of such words as retain, receive, horrible, pocket, motion, etc. should be regarded as simple, non- motivated stems.

Derived stems are built on stems of various structures though which they are motivated, i.e. derived stems are understood on the basis of the derivative relations between their IC’s and the correlated stems. The derived stems are mostly polymorphic in which case the segmentation results only in one IC that is itself a stem, the other IC being necessarily a derivational affix.

Derived stems are not necessarily polymorphic.

Compound stems are made up of two IC’s, both of which are themselves stems, for example match-box, driving-suit, pen-holder, etc. It is built by joining of two stems, one of which is simple, the other derived.

In more complex cases the result of the analysis at the two levels sometimes seems even to contracted one another.

The derivational types of words are classified according to the structure of their stems into simple, derived and compound words.

Derived words are those composed of one root- morpheme and one or more derivational morpheme.

Compound words contain at least two root- morphemes, the number of derivational morphemes being insignificant.

Derivational compound is a word formed by a simultaneous process of composition and derivational.

Compound words proper are formed by joining together stems of word already available in the language.

Теги:

Word structure in modern english

Реферат

Английский

Просмотров: 27488

Найти в Wikkipedia статьи с фразой: Word structure in modern english

Скачать материал

Скачать материал

- Сейчас обучается 398 человек из 63 регионов

Описание презентации по отдельным слайдам:

-

1 слайд

WORD-STRUCTURE

Morphemic Structure of Words

Lecture 8 -

2 слайд

1. Word-Structure and Morphemes

Morphe – ‘form’ + -eme. The Greek suffix – eme has been adopted by linguists to denote the smallest unit (phoneme, sememe, lexeme)

Word-structure is internal organization of words.

The morpheme is the smallest indivisible two-facet language unit. -

3 слайд

MORPHEMES

Morphemes cannot be segmented into smaller units without losing their constitutive essence (two-facetedness) – association of a certain meaning with a certain sound-pattern.

Morphemes occur in speech only as constituent parts of words but not independently. -

4 слайд

SEGMENTATION OF WORDS

INTO MORPHEMES

Boiler = boil- + er;

Driller = drill- + er ;

recurrence of the morpheme -er in these and other similar words and of the morphemes boil- and drill- in

to boil, a boil, boiling and

to drill, a drill, drilling, a drill-press, etc. -

5 слайд

SEGMENTATION OF WORDS

INTO MORPHEMES

flower-pot = flower- + -pot;

shoe-lace = shoe- + -lace;

Like a word a morpheme is a two-facet language unit, an association of a certain meaning with a certain sound-pattern.

Unlike a word a morpheme is not an autonomous unit and can occur in speech only as a constituent part of the word.

Lace [l], [ei] ,[s] — without meaning. -

6 слайд

Word-cluster

please pleasing pleasure pleasant

[pli:z] [pli:z] [pleʒ] [plez]All the representations of the given morpheme that manifest alteration are called allomorphs of that morpheme or morpheme variants.

Thus, [pli:z], [plez] and [рlеʒ] are allomorphs of оnе and the same morpheme. -

7 слайд

The root-morphemes

in the word-clusters

Duke [dju:k], ducal [‘dju:kl],

duchess [‘d˄tʃiƨ], duchy [‘d˄tʃi]

or

Poor [puə] , poverty [‘povəti] —

are the allomorphs of one morpheme -

8 слайд

2.1. Semantic Classification of Morphemes

Root-morphemes (radicals) — the lexical nucleus of words, which has an individual lexical meaning shared by no other morpheme of the language:

Helpless, handy, rewrite, hopeful, disorder

Help- hand- -write hope- -order

The root-morpheme is isolated as the morpheme common to a set of words making up a word-cluster:

work- in to work, worker, working or

theor- in theory, theorist, theoretical, etc. -

9 слайд

Non-root morphemes

Non-root morphemes include inflectional morphemes (inflections) and affixational morphemes (affixes). Inflections carry only grammatical meaning.

Lexicology is concerned only with affixational morphemes.

A prefix: understand – mis-understand, correct – in-correct).

A suffix: (-en, -y, -less in heart-en heart-y, heart-less). -

10 слайд

2.2. Structural Classification of Morphemes

A free morpheme — one that coincides with the stem or a word-form. Many root-morphemes are free morphemes, for example, use − of the noun useless is a free morpheme because it coincides with one of the forms of the noun use.

A bound morpheme — a morpheme that must be attached to another element. It occurs only as a constituent part of a word. Affixes are bound morphemes for they always make part of a word, for example:-ness, -ship in the words kind-ness, friend-ship; un-, dis- in the words un-tidy, dis-like. -

11 слайд

All unique roots and pseudo-roots are-bound morphemes.

Such are the root-morphemes theor- in theory, theoretical, etc.,

barbar-in barbarism, barbarian, etc.,

-ceive in conceive, perceive, etc. -

12 слайд

Semi-bound (semi-free) morphemes -morphemes that can function in a morphemic sequence both as an affix and as a free morpheme: the morpheme well and half can occur as free morphemes: sing well, half a month.

They can also occur as bound morphemes in words like well-known, half-eaten, half-done. -

13 слайд

The relationship between the two classifications of morphemes

-

14 слайд

Word-structure

on the morphemic level:

1st Group — Combining forms are morphemes borrowed namely from Greek or Latin in which they exist as free forms. They are considered to be bound roots: tele-phone consists of two bound roots.

Phonoscope = ‘sound’ + ‘seeing’;

Microscope = ‘smallness’ + ‘seeing’;

Telegraph = ‘far’ + ‘writing’; -

15 слайд

The 2nd Group embraces morphemes occupying a kind of intermediate position, morphemes that are changing their class membership.

Root morpheme man – in postman, fisherman, gentleman, etc. in comparison with man-made, man-servant.

-man = -er; in cabman, chairman, tradesman

Not a male adult But agent!

* She is an Englishman

*All women are tradesmen. -

16 слайд

3. TYPES OF MEANING IN MORPHEMES

In morphemes can be singled out different types of meaning depending on the semantic class they belong to.

Root-morphemes have lexical, differential and distributional types of meaning.

Affixational morphemes have lexical, part of-speech, differential and distributional types of meaning.

Both root-morphemes and affixational morphemes are devoid of grammatical meaning. -

17 слайд

3.1. LEXICAL MEANING

Root-morphemes have an individual lexical meaning shared by no other morphemes in the language: light, deaf, deep, etc.

Affixational morphemes have a more generalizing character of lexical meaning: the suffix –en carries the meaning “the change of a quality”, e.g. to lighten – to become lighter, to deafen – to make somebody deaf. -

18 слайд

Morphemes may be also analyzed into denotational and connotational components:

The connotational component of meaning may be found in affixational morphemes: -ette (kitchenette); -ie (dearie, girlie); -ling (duckling) bear a heavy emotive charge.

-

19 слайд