This article is about the unit of speech and writing. For the computer software, see Microsoft Word. For other uses, see Word (disambiguation).

Codex Claromontanus in Latin. The practice of separating words with spaces was not universal when this manuscript was written.

A word is a basic element of language that carries an objective or practical meaning, can be used on its own, and is uninterruptible.[1] Despite the fact that language speakers often have an intuitive grasp of what a word is, there is no consensus among linguists on its definition and numerous attempts to find specific criteria of the concept remain controversial.[2] Different standards have been proposed, depending on the theoretical background and descriptive context; these do not converge on a single definition.[3]: 13:618 Some specific definitions of the term «word» are employed to convey its different meanings at different levels of description, for example based on phonological, grammatical or orthographic basis. Others suggest that the concept is simply a convention used in everyday situations.[4]: 6

The concept of «word» is distinguished from that of a morpheme, which is the smallest unit of language that has a meaning, even if it cannot stand on its own.[1] Words are made out of at least one morpheme. Morphemes can also be joined to create other words in a process of morphological derivation.[2]: 768 In English and many other languages, the morphemes that make up a word generally include at least one root (such as «rock», «god», «type», «writ», «can», «not») and possibly some affixes («-s», «un-«, «-ly», «-ness»). Words with more than one root («[type][writ]er», «[cow][boy]s», «[tele][graph]ically») are called compound words. In turn, words are combined to form other elements of language, such as phrases («a red rock», «put up with»), clauses («I threw a rock»), and sentences («I threw a rock, but missed»).

In many languages, the notion of what constitutes a «word» may be learned as part of learning the writing system.[5] This is the case for the English language, and for most languages that are written with alphabets derived from the ancient Latin or Greek alphabets. In English orthography, the letter sequences «rock», «god», «write», «with», «the», and «not» are considered to be single-morpheme words, whereas «rocks», «ungodliness», «typewriter», and «cannot» are words composed of two or more morphemes («rock»+»s», «un»+»god»+»li»+»ness», «type»+»writ»+»er», and «can»+»not»).

Definitions and meanings

Since the beginning of the study of linguistics, numerous attempts at defining what a word is have been made, with many different criteria.[5] However, no satisfying definition has yet been found to apply to all languages and at all levels of linguistic analysis. It is, however, possible to find consistent definitions of «word» at different levels of description.[4]: 6 These include definitions on the phonetic and phonological level, that it is the smallest segment of sound that can be theoretically isolated by word accent and boundary markers; on the orthographic level as a segment indicated by blank spaces in writing or print; on the basis of morphology as the basic element of grammatical paradigms like inflection, different from word-forms; within semantics as the smallest and relatively independent carrier of meaning in a lexicon; and syntactically, as the smallest permutable and substitutable unit of a sentence.[2]: 1285

In some languages, these different types of words coincide and one can analyze, for example, a «phonological word» as essentially the same as «grammatical word». However, in other languages they may correspond to elements of different size.[4]: 1 Much of the difficulty stems from the eurocentric bias, as languages from outside of Europe may not follow the intuitions of European scholars. Some of the criteria for «word» developed can only be applicable to languages of broadly European synthetic structure.[4]: 1-3 Because of this unclear status, some linguists propose avoiding the term «word» altogether, instead focusing on better defined terms such as morphemes.[6]

Dictionaries categorize a language’s lexicon into individually listed forms called lemmas. These can be taken as an indication of what constitutes a «word» in the opinion of the writers of that language. This written form of a word constitutes a lexeme.[2]: 670-671 The most appropriate means of measuring the length of a word is by counting its syllables or morphemes.[7] When a word has multiple definitions or multiple senses, it may result in confusion in a debate or discussion.[8]

Phonology

One distinguishable meaning of the term «word» can be defined on phonological grounds. It is a unit larger or equal to a syllable, which can be distinguished based on segmental or prosodic features, or through its interactions with phonological rules. In Walmatjari, an Australian language, roots or suffixes may have only one syllable but a phonologic word must have at least two syllables. A disyllabic verb root may take a zero suffix, e.g. luwa-ø ‘hit!’, but a monosyllabic root must take a suffix, e.g. ya-nta ‘go!’, thus conforming to a segmental pattern of Walmatjari words. In the Pitjantjatjara dialect of the Wati language, another language form Australia, a word-medial syllable can end with a consonant but a word-final syllable must end with a vowel.[4]: 14

In most languages, stress may serve a criterion for a phonological word. In languages with a fixed stress, it is possible to ascertain word boundaries from its location. Although it is impossible to predict word boundaries from stress alone in languages with phonemic stress, there will be just one syllable with primary stress per word, which allows for determining the total number of words in an utterance.[4]: 16

Many phonological rules operate only within a phonological word or specifically across word boundaries. In Hungarian, dental consonants /d/, /t/, /l/ or /n/ assimilate to a following semi-vowel /j/, yielding the corresponding palatal sound, but only within one word. Conversely, external sandhi rules act across word boundaries. The prototypical example of this rule comes from Sanskrit; however, initial consonant mutation in contemporary Celtic languages or the linking r phenomenon in some non-rhotic English dialects can also be used to illustrate word boundaries.[4]: 17

It is often the case that a phonological word does not correspond to our intuitive conception of a word. The Finnish compound word pääkaupunki ‘capital’ is phonologically two words (pää ‘head’ and kaupunki ‘city’) because it does not conform to Finnish patterns of vowel harmony within words. Conversely, a single phonological word may be made up of more than one syntactical elements, such as in the English phrase I’ll come, where I’ll forms one phonological word.[3]: 13:618

Lexemes

A word can be thought of as an item in a speaker’s internal lexicon; this is called a lexeme. Nevertheless, it is considered different from a word used in everyday speech, since it is assumed to also include inflected forms. Therefore, the lexeme teapot refers to the singular teapot as well as the plural, teapots. There is also the question to what extent should inflected or compounded words be included in a lexeme, especially in agglutinative languages. For example, there is little doubt that in Turkish the lexeme for house should include nominative singular ev or plural evler. However, it is not clear if it should also encompass the word evlerinizden ‘from your houses’, formed through regular suffixation. There are also lexemes such as «black and white» or «do-it-yourself», which, although consist of multiple words, still form a single collocation with a set meaning.[3]: 13:618

Grammar

Grammatical words are proposed to consist of a number of grammatical elements which occur together (not in separate places within a clause) in a fixed order and have a set meaning. However, there are exceptions to all of these criteria.[4]: 19

Single grammatical words have a fixed internal structure; when the structure is changed, the meaning of the word also changes. In Dyirbal, which can use many derivational affixes with its nouns, there are the dual suffix -jarran and the suffix -gabun meaning «another». With the noun yibi they can be arranged into yibi-jarran-gabun («another two women») or yibi-gabun-jarran («two other women») but changing the suffix order also changes their meaning. Speakers of a language also usually associate a specific meaning with a word and not a single morpheme. For example, when asked to talk about untruthfulness they rarely focus on the meaning of morphemes such as -th or -ness.[4]: 19-20

Semantics

Leonard Bloomfield introduced the concept of «Minimal Free Forms» in 1928. Words are thought of as the smallest meaningful unit of speech that can stand by themselves.[9]: 11 This correlates phonemes (units of sound) to lexemes (units of meaning). However, some written words are not minimal free forms as they make no sense by themselves (for example, the and of).[10]: 77 Some semanticists have put forward a theory of so-called semantic primitives or semantic primes, indefinable words representing fundamental concepts that are intuitively meaningful. According to this theory, semantic primes serve as the basis for describing the meaning, without circularity, of other words and their associated conceptual denotations.[11][12]

Features

In the Minimalist school of theoretical syntax, words (also called lexical items in the literature) are construed as «bundles» of linguistic features that are united into a structure with form and meaning.[13]: 36–37 For example, the word «koalas» has semantic features (it denotes real-world objects, koalas), category features (it is a noun), number features (it is plural and must agree with verbs, pronouns, and demonstratives in its domain), phonological features (it is pronounced a certain way), etc.

Orthography

Words made out of letters, divided by spaces

In languages with a literary tradition, the question of what is considered a single word is influenced by orthography. Word separators, typically spaces and punctuation marks are common in modern orthography of languages using alphabetic scripts, but these are a relatively modern development in the history of writing. In character encoding, word segmentation depends on which characters are defined as word dividers. In English orthography, compound expressions may contain spaces. For example, ice cream, air raid shelter and get up each are generally considered to consist of more than one word (as each of the components are free forms, with the possible exception of get), and so is no one, but the similarly compounded someone and nobody are considered single words.

Sometimes, languages which are close grammatically will consider the same order of words in different ways. For example, reflexive verbs in the French infinitive are separate from their respective particle, e.g. se laver («to wash oneself»), whereas in Portuguese they are hyphenated, e.g. lavar-se, and in Spanish they are joined, e.g. lavarse.[a]

Not all languages delimit words expressly. Mandarin Chinese is a highly analytic language with few inflectional affixes, making it unnecessary to delimit words orthographically. However, there are many multiple-morpheme compounds in Mandarin, as well as a variety of bound morphemes that make it difficult to clearly determine what constitutes a word.[14]: 56 Japanese uses orthographic cues to delimit words, such as switching between kanji (characters borrowed from Chinese writing) and the two kana syllabaries. This is a fairly soft rule, because content words can also be written in hiragana for effect, though if done extensively spaces are typically added to maintain legibility. Vietnamese orthography, although using the Latin alphabet, delimits monosyllabic morphemes rather than words.

Word boundaries

The task of defining what constitutes a «word» involves determining where one word ends and another word begins, that is identifying word boundaries. There are several ways to determine where the word boundaries of spoken language should be placed:[5]

- Potential pause: A speaker is told to repeat a given sentence slowly, allowing for pauses. The speaker will tend to insert pauses at the word boundaries. However, this method is not foolproof: the speaker could easily break up polysyllabic words, or fail to separate two or more closely linked words (e.g. «to a» in «He went to a house»).

- Indivisibility: A speaker is told to say a sentence out loud, and then is told to say the sentence again with extra words added to it. Thus, I have lived in this village for ten years might become My family and I have lived in this little village for about ten or so years. These extra words will tend to be added in the word boundaries of the original sentence. However, some languages have infixes, which are put inside a word. Similarly, some have separable affixes: in the German sentence «Ich komme gut zu Hause an«, the verb ankommen is separated.

- Phonetic boundaries: Some languages have particular rules of pronunciation that make it easy to spot where a word boundary should be. For example, in a language that regularly stresses the last syllable of a word, a word boundary is likely to fall after each stressed syllable. Another example can be seen in a language that has vowel harmony (like Turkish):[15]: 9 the vowels within a given word share the same quality, so a word boundary is likely to occur whenever the vowel quality changes. Nevertheless, not all languages have such convenient phonetic rules, and even those that do present the occasional exceptions.

- Orthographic boundaries: Word separators, such as spaces and punctuation marks can be used to distinguish single words. However, this depends on a specific language. East-asian writing systems often do not separate their characters. This is the case with Chinese, Japanese writing, which use logographic characters, as well as Thai and Lao, which are abugidas.

Morphology

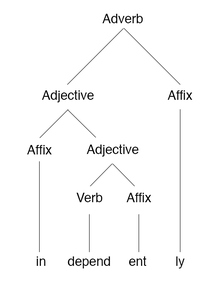

A morphology tree of the English word «independently»

Morphology is the study of word formation and structure. Words may undergo different morphological processes which are traditionally classified into two broad groups: derivation and inflection. Derivation is a process in which a new word is created from existing ones, often with a change of meaning. For example, in English the verb to convert may be modified into the noun a convert through stress shift and into the adjective convertible through affixation. Inflection adds grammatical information to a word, such as indicating case, tense, or gender.[14]: 73

In synthetic languages, a single word stem (for example, love) may inflect to have a number of different forms (for example, loves, loving, and loved). However, for some purposes these are not usually considered to be different words, but rather different forms of the same word. In these languages, words may be considered to be constructed from a number of morphemes.

In Indo-European languages in particular, the morphemes distinguished are:

- The root.

- Optional suffixes.

- A inflectional suffix.

Thus, the Proto-Indo-European *wr̥dhom would be analyzed as consisting of

- *wr̥-, the zero grade of the root *wer-.

- A root-extension *-dh- (diachronically a suffix), resulting in a complex root *wr̥dh-.

- The thematic suffix *-o-.

- The neuter gender nominative or accusative singular suffix *-m.

Philosophy

Philosophers have found words to be objects of fascination since at least the 5th century BC, with the foundation of the philosophy of language. Plato analyzed words in terms of their origins and the sounds making them up, concluding that there was some connection between sound and meaning, though words change a great deal over time. John Locke wrote that the use of words «is to be sensible marks of ideas», though they are chosen «not by any natural connexion that there is between particular articulate sounds and certain ideas, for then there would be but one language amongst all men; but by a voluntary imposition, whereby such a word is made arbitrarily the mark of such an idea».[16] Wittgenstein’s thought transitioned from a word as representation of meaning to «the meaning of a word is its use in the language.»[17]

Classes

Each word belongs to a category, based on shared grammatical properties. Typically, a language’s lexicon may be classified into several such groups of words. The total number of categories as well as their types are not universal and vary among languages. For example, English has a group of words called articles, such as the (the definite article) or a (the indefinite article), which mark definiteness or identifiability. This class is not present in Japanese, which depends on context to indicate this difference. On the other hand, Japanese has a class of words called particles which are used to mark noun phrases according to their grammatical function or thematic relation, which English marks using word order or prosody.[18]: 21–24

It is not clear if any categories other than interjection are universal parts of human language. The basic bipartite division that is ubiquitous in natural languages is that of nouns vs verbs. However, in some Wakashan and Salish languages, all content words may be understood as verbal in nature. In Lushootseed, a Salish language, all words with ‘noun-like’ meanings can be used predicatively, where they function like verb. For example, the word sbiaw can be understood as ‘(is a) coyote’ rather than simply ‘coyote’.[19][3]: 13:631 On the other hand, in Eskimo–Aleut languages all content words can be analyzed as nominal, with agentive nouns serving the role closest to verbs. Finally, in some Austronesian languages it is not clear whether the distinction is applicable and all words can be best described as interjections which can perform the roles of other categories.[3]: 13:631

The current classification of words into classes is based on the work of Dionysius Thrax, who, in the 1st century BC, distinguished eight categories of Ancient Greek words: noun, verb, participle, article, pronoun, preposition, adverb, and conjunction. Later Latin authors, Apollonius Dyscolus and Priscian, applied his framework to their own language; since Latin has no articles, they replaced this class with interjection. Adjectives (‘happy’), quantifiers (‘few’), and numerals (‘eleven’) were not made separate in those classifications due to their morphological similarity to nouns in Latin and Ancient Greek. They were recognized as distinct categories only when scholars started studying later European languages.[3]: 13:629

In Indian grammatical tradition, Pāṇini introduced a similar fundamental classification into a nominal (nāma, suP) and a verbal (ākhyāta, tiN) class, based on the set of suffixes taken by the word. Some words can be controversial, such as slang in formal contexts; misnomers, due to them not meaning what they would imply; or polysemous words, due to the potential confusion between their various senses.[20]

History

In ancient Greek and Roman grammatical tradition, the word was the basic unit of analysis. Different grammatical forms of a given lexeme were studied; however, there was no attempt to decompose them into morphemes. [21]: 70 This may have been the result of the synthetic nature of these languages, where the internal structure of words may be harder to decode than in analytic languages. There was also no concept of different kinds of words, such as grammatical or phonological – the word was considered a unitary construct.[4]: 269 The word (dictiō) was defined as the minimal unit of an utterance (ōrātiō), the expression of a complete thought.[21]: 70

See also

- Longest words

- Utterance

- Word (computer architecture)

- Word count, the number of words in a document or passage of text

- Wording

- Etymology

Notes

- ^ The convention also depends on the tense or mood—the examples given here are in the infinitive, whereas French imperatives, for example, are hyphenated, e.g. lavez-vous, whereas the Spanish present tense is completely separate, e.g. me lavo.

References

- ^ a b Brown, E. K. (2013). The Cambridge dictionary of linguistics. J. E. Miller. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 473. ISBN 978-0-521-76675-3. OCLC 801681536.

- ^ a b c d Bussmann, Hadumod (1998). Routledge dictionary of language and linguistics. Gregory Trauth, Kerstin Kazzazi. London: Routledge. p. 1285. ISBN 0-415-02225-8. OCLC 41252822.

- ^ a b c d e f Brown, Keith (2005). Encyclopedia of Language and Linguistics: V1-14. Keith Brown (2nd ed.). ISBN 1-322-06910-7. OCLC 1097103078.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Word: a cross-linguistic typology. Robert M. W. Dixon, A. Y. Aikhenvald. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 2002. ISBN 0-511-06149-8. OCLC 57123416.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ a b c Haspelmath, Martin (2011). «The indeterminacy of word segmentation and the nature of morphology and syntax». Folia Linguistica. 45 (1). doi:10.1515/flin.2011.002. ISSN 0165-4004. S2CID 62789916.

- ^ Harris, Zellig S. (1946). «From morpheme to utterance». Language. 22 (3): 161–183. doi:10.2307/410205. JSTOR 410205.

- ^ The Oxford handbook of the word. John R. Taylor (1st ed.). Oxford, United Kingdom. 2015. ISBN 978-0-19-175669-6. OCLC 945582776.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Chodorow, Martin S.; Byrd, Roy J.; Heidorn, George E. (1985). «Extracting semantic hierarchies from a large on-line dictionary». Proceedings of the 23rd Annual Meeting on Association for Computational Linguistics. Chicago, Illinois: Association for Computational Linguistics: 299–304. doi:10.3115/981210.981247. S2CID 657749.

- ^ Katamba, Francis (2005). English words: structure, history, usage (2nd ed.). London: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-29892-X. OCLC 54001244.

- ^ Fleming, Michael; Hardman, Frank; Stevens, David; Williamson, John (2003-09-02). Meeting the Standards in Secondary English (1st ed.). Routledge. doi:10.4324/9780203165553. ISBN 978-1-134-56851-2.

- ^ Wierzbicka, Anna (1996). Semantics : primes and universals. Oxford [England]: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-870002-4. OCLC 33012927.

- ^ «The search for the shared semantic core of all languages.». Meaning and universal grammar. Volume II: theory and empirical findings. Cliff Goddard, Anna Wierzbicka. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Pub. Co. 2002. ISBN 1-58811-264-0. OCLC 752499720.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Adger, David (2003). Core syntax: a minimalist approach. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-924370-0. OCLC 50768042.

- ^ a b An introduction to language and linguistics. Ralph W. Fasold, Jeff Connor-Linton. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. 2006. ISBN 978-0-521-84768-1. OCLC 62532880.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Bauer, Laurie (1983). English word-formation. Cambridge [Cambridgeshire]. ISBN 0-521-24167-7. OCLC 8728300.

- ^ Locke, John (1690). «Chapter II: Of the Signification of Words». An Essay Concerning Human Understanding. Vol. III (1st ed.). London: Thomas Basset.

- ^ Biletzki, Anar; Matar, Anat (2021). Ludwig Wittgenstein. The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Winter 2021 ed.). Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University.

- ^ Linguistics: an introduction to language and communication. Adrian Akmajian (6th ed.). Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press. 2010. ISBN 978-0-262-01375-8. OCLC 424454992.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Beck, David (2013-08-29), Rijkhoff, Jan; van Lier, Eva (eds.), «Unidirectional flexibility and the noun–verb distinction in Lushootseed», Flexible Word Classes, Oxford University Press, pp. 185–220, doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199668441.003.0007, ISBN 978-0-19-966844-1, retrieved 2022-08-25

- ^ De Soto, Clinton B.; Hamilton, Margaret M.; Taylor, Ralph B. (December 1985). «Words, People, and Implicit Personality Theory». Social Cognition. 3 (4): 369–382. doi:10.1521/soco.1985.3.4.369. ISSN 0278-016X.

- ^ a b Robins, R. H. (1997). A short history of linguistics (4th ed.). London. ISBN 0-582-24994-5. OCLC 35178602.

Bibliography

Wikimedia Commons has media related to Words.

Wikiquote has quotations related to Word.

Look up word in Wiktionary, the free dictionary.

- Barton, David (1994). Literacy: an introduction to the ecology of written language. Oxford, UK: Blackwell. p. 96. ISBN 0-631-19089-9. OCLC 28722223.

- The encyclopedia of language & linguistics. E. K. Brown, Anne Anderson (2nd ed.). Amsterdam: Elsevier. 2006. ISBN 978-0-08-044854-1. OCLC 771916896.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - Crystal, David (1995). The Cambridge encyclopedia of the English language. Cambridge [England]: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-40179-8. OCLC 31518847.

- Plag, Ingo (2003). Word-formation in English. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-511-07843-9. OCLC 57545191.

- The Oxford English Dictionary. J. A. Simpson, E. S. C. Weiner, Oxford University Press (2nd ed.). Oxford: Clarendon Press. 1989. ISBN 0-19-861186-2. OCLC 17648714.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link)

What Is the Definition of Word?

«The trouble with words,» said British dramatist Dennis Potter, «is that you never know whose mouths they’ve been in.».

ZoneCreative S.r.l./Getty Images

A word is a speech sound or a combination of sounds, or its representation in writing, that symbolizes and communicates a meaning and may consist of a single morpheme or a combination of morphemes.

The branch of linguistics that studies word structures is called morphology. The branch of linguistics that studies word meanings is called lexical semantics.

Etymology

From Old English, «word»

Examples and Observations

- «[A word is the] smallest unit of grammar that can stand alone as a complete utterance, separated by spaces in written language and potentially by pauses in speech.»

-David Crystal, The Cambridge Encyclopedia of the English Language. Cambridge University Press, 2003 - «A grammar . . . is divided into two major components, syntax and morphology. This division follows from the special status of the word as a basic linguistic unit, with syntax dealing with the combination of words to make sentences, and morphology with the form of words themselves.» -R. Huddleston and G. Pullum, The Cambridge Grammar of the English Language. Cambridge University Press, 2002

- «We want words to do more than they can. We try to do with them what comes to very much like trying to mend a watch with a pickaxe or to paint a miniature with a mop; we expect them to help us to grip and dissect that which in ultimate essence is as ungrippable as shadow. Nevertheless there they are; we have got to live with them, and the wise course is to treat them as we do our neighbours, and make the best and not the worst of them.»

-Samuel Butler, The Note-Books of Samuel Butler, 1912 - Big Words

«A Czech study . . . looked at how using big words (a classic strategy for impressing others) affects perceived intelligence. Counter-intuitvely, grandiose vocabulary diminished participants’ impressions of authors’ cerebral capacity. Put another way: simpler writing seems smarter.»

-Julie Beck, «How to Look Smart.» The Atlantic, September 2014 - The Power of Words

«It is obvious that the fundamental means which man possesses of extending his orders of abstractions indefinitely is conditioned, and consists in general in symbolism and, in particular, in speech. Words, considered as symbols for humans, provide us with endlessly flexible conditional semantic stimuli, which are just as ‘real’ and effective for man as any other powerful stimulus. - Virginia Woolf on Words

«It is words that are to blame. They are the wildest, freest, most irresponsible, most un-teachable of all things. Of course, you can catch them and sort them and place them in alphabetical order in dictionaries. But words do not live in dictionaries; they live in the mind. If you want proof of this, consider how often in moments of emotion when we most need words we find none. Yet there is the dictionary; there at our disposal are some half-a-million words all in alphabetical order. But can we use them? No, because words do not live in dictionaries, they live in the mind. Look once more at the dictionary. There beyond a doubt lie plays more splendid than Antony and Cleopatra; poems lovelier than the ‘Ode to a Nightingale’; novels beside which Pride and Prejudice or David Copperfield are the crude bunglings of amateurs. It is only a question of finding the right words and putting them in the right order. But we cannot do it because they do not live in dictionaries; they live in the mind. And how do they live in the mind? Variously and strangely, much as human beings live, ranging hither and thither, falling in love, and mating together.»

-Virginia Woolf, «Craftsmanship.» The Death of the Moth and Other Essays, 1942 - Word Word

«Word Word [1983: coined by US writer Paul Dickson]. A non-technical, tongue-in-cheek term for a word repeated in contrastive statements and questions: ‘Are you talking about an American Indian or an Indian Indian?’; ‘It happens in Irish English as well as English English.'»

-Tom McArthur, The Oxford Companion to the English Language. Oxford University Press, 1992

There

are broadly speaking two schools of thought in present-day

linguistics representing the main lines of contemporary thinking on

the problem: the referential approach which seeks to formulate the

essence of meaning by establishing the interdependence between words

and things or concepts they denote, and the functional approach,

which studies the functions of a word in speech and is less concerned

with what meaning is than with how it works.

All

major works on semantic theory have so far been based on referential

concepts of meaning. The essential feature of this approach is that

it distinguishes between the three components closely connected with

meaning: the sound form of the linguistic sign, the concept

underlying this sound form and the referent, i.e. that part or that

aspect of reality to which the linguistic sign refers. The best known

referential model of meaning is the so-called “basic triangle”.

CONCEPT

SOUND

FORM –––––––––– REFERENT

As

can be seen from the diagram the sound form of the linguistic sign,

e.g. [teibl]

, is connected with our concept of the piece of furniture which it

denotes and through it with the referent, i.e. the actual table. The

common feature of any referential approach is the implication that

meaning is in some form or other connected with the referent.

Meaning

and Sound Form

The

sound form of the word is not identical with its meaning, e.g. [d

v]

is the sound form used to denote a pearl-grey bird. There are no

inherent connections, however, between this particular sound cluster

and the meaning of the word dove. The connections are conventional

and arbitrary. This can be easily proved by comparing the sound forms

of different languages conveying the same meaning: стіл-

стол-

table – tisch.

It

can also be proved by comparing almost identical sound forms that

possess different meanings in different languages. E.g.: [

ni:s]

— a daughter of a brother or a sister (English); ніс

—

a

part of a face (Ukrainian).

For

more convincing evidence of the conventional and arbitrary nature of

the connection between sound form and meaning all we have to do is to

point to homonyms. The word case means something that has happened

and case also means a box, a container.

Besides,

if meaning were inherently connected with the sound form of a

linguistic unit, it would follow that a change in the sound form of

the word in the course of its historical development does not

necessarily affect its meaning.

Meaning

and Concept

When

we examine a word we see that its meaning though closely connected

with the underlying concept or concepts is not identical with them.

Concept

is the category of human cognition. Concept is the thought of the

object that singles out its essential features. Our concepts reflect

the most common and typical features of different objects. Being the

result of abstraction and generalisation all concepts are thus almost

the same for the whole of humanity in one and the same period of its

historical development. That is to say, words expressing identical

concepts in English and Ukrainian differ considerably.

e.g.:

The concept of the physical organism is expressed in English by the

word body, in Ukrainian by тіло,

but the semantic range of the English word is not identical with that

of Ukrainian. The word body is known to have developed a number of

secondary meanings and may denote: a number of persons and things, a

collective whole (the body of electors) as distinguished from the

limbs and the head; hence, the main part as of an army, a structure

of a book (the body of a book). As it is known, such concepts are

expressed in Ukrainian by other words.

The

difference between meaning and concept can also be observed by

comparing synonymous words and word-groups expressing the same

concepts but possessing a linguistic meaning which is felt as

different in each of the units under consideration.

e.g.:

—

to

fail the exam, to come down, to muff;

—

to be ploughed, plucked, pipped.

Соседние файлы в предмете [НЕСОРТИРОВАННОЕ]

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

The word, a thorny concept.

All of us who speak, we know that we speak through words. Any of us is able to divide what he says into independent words, which means that we know how to count how many words are in a given sentence without hesitation. But certainly they put us in a bind if we ask for a definition of the word .

Why? We would all agree that if , you come, you and I hope are words, because we are able to divide the statement if you come, I hope in these basic units. What happens is that the issue becomes more complicated with units such as round table, twenty four , etc., of which we cannot say with the same assurance whether they are words or groups of words. At first glance, we say that round table consists of two words that can separate table of round and the result table , attach it to other adjectives: square table, blue table, etc. This raises the problem that by saying that a round table is held in the Cultural Center of the neighborhood, the two words express a single concept similar to that expressed in the word debate . The meaning of the round table is not equal to the sum of the meanings of its components: a new lexical element has been created in which both words are inextricably linked that have a new meaning. This is the same as saying that a new word has been created. If we consider them as two words, it is because we write them separately and because they maintain a characteristic accentual independence, but this set should appear in the dictionary with its new meaning.

There are many similar cases: Twenty-one is one word. But thirty- one or two hundred fifty-six , are they one or more words? What happens with the day before yesterday and its synonym before yesterday ? ¿ And with that in because I please, and so on for your information ? We could provide many more examples.

Linguistics has not yet found a valid and general definition for the word concept, but it is not surprising that this is so: it is an intuitive concept, of use, not valid for the analysis as it is proposed today; This leaves us with the curious fact that this science, linguistics, cannot define one of its basic units.

What to do then? When linguistics is reorganized and seeks new paths at the beginning of the 20th century, it finds that with the new concepts that it has to handle, there is no place for the word as we intuitively understand it: it must find a unit that encompasses both round table and blue, always, that, Miguel, ay, plain, book and bookstore , and that in addition, it is possible that you should also include in that group elements such as hetero -, – cardia , tele-, pro -, – mitir ( heterosexual, tachycardia, cable car, promise, resign ), etc. , and look for solutions. Let’s see below some of the answers you have given.

The paradox we are dealing with has its origin in the fact that the usual concept of the word conceals several different realities from each other. Let’s consider several word lists:

- singing(rolled)

- singing( singing action)

- singing(of a hard)

- have, have, have, had, had, have had.

- clean, clean, clean, clean.

- Rosa,rosam , rosae , roses, rosarum , rosis .

- Drink, drink,beburcio , drinker.

- dignified, dignified, dignified, dignified.

In (1) we have three words with different meanings and also different origins, which have in common the phonic (and graphic) form: they are different but homonymous words ; We will say of each of them that it is a grammatical word , because in the lexicon of Spanish (the lexical component, remember) each would have an entry.

The case in (2) is different: each set of words has only one entry in the dictionary, and it seems logical: (2a) is a list of conjugated forms of the verb to have ; (2b) is the clean adjective flexed in gender and number, (2c.) Is the list of forms that the Latin word rosa can taketo be declined It is clear that in (2a) we have several forms of the same word , and that in each of the lists it is the first of these forms that we use as a form of appointment, that is, the form we choose as a representative of the complete list . It seems logical that all of them are part of the same lexical entry because, knowing Spanish as we know it, we know that it is automatic to obtain all these forms from the citation form.

In (3) the same does not happen: although there is an obvious relationship between the four words that make up each group, all of them are different words that we use in different environments: some are verbs; others, adjectives; others, nouns and others, adverbs. They are independent words but – as we said in thecole – “from the same family”.

As we see, you have to be very careful with words. Among them they adopt very diverse relationships and the way they are formed is determined by the role they will play.

In (1) there is no relationship other than the phonic between them; in (2), there is a regular flexion process , which we will see next; in (3) another process, that is given derivation . Another possible process is that which appears in a round table , similar (not identical) to the one we have in icebreakers, that of the composition . We will talk about all of them in this topic.

The morphological units lower than the word.

If it is no possible to give a definition of the intuitive concept of word because it is not functional in the linguistic description, we will have to look for the units we need in the word. Through the previous examples we have been able to suspect the existence of lower-level units whose combination creates a morphological structure that is what we call word .

These units exist, and we check this by contrasting several forms of word or several words “of the same family”. Take the examples of (2b): leaving only what they have in common, we are left clean . This part of all these words is what we traditionally called root . It is an indivisible element in smaller units with meaning: nothing shorter than clean – has meaning related or not with the idea of cleaning, cleaning, etc., and is limited to being a set of phonemes that lack semantic value. What remains of those words, -o, -a, -os, -as is also divisible into two groups of units, – or and – a , which indicate male and female gender, respectively, and -s , which indicates grammatical plurality. Its significant value, as we see, is different from that of limp -. This refers to something of reality (the concept of cleanliness), while -o , – a and – s have a purely grammatical meaning: the concepts they refer to have no existence in extra linguistic reality. There are, then, units lower than the word and are, at least of two types:

A minimum units with meaning (ie, which are smaller than the word and are indivisible elements having meaning) we call monemes (in American school, morphemes ), and come in two types: the lexeme s or morphemes lexicons , which have lexical meaning , which refer to concepts of reality and morphemes to dry or grammatical morphemes , which have a purely grammatical meaning.

The word from the monem point of view :

Lexemes form words alone, or more commonly, accompanied by morphemes. In the case of a tree we have the seemingly only lexeme [1] ; in trees, trees, trees, peaks , etc., they are accompanied by morphemes. Words carrying lexemes are nouns, adjectives, verbs and most of what we call adverbs.

Morphemes can also appear in isolation (case of prepositions, conjunctions, article and auxiliary verb) or, as we have seen, being part of words. Is I speak thus of free morphemes (those who form words by themselves: see, yesterday, with, though ) and morphemes linked s (which must appear necessarily part of a word: re – ado , – eda , -ista , etc.)

So the word is a linguistic unit consisting of one or more monemes that follow a fixed order (we can not change the order of monemes in disembarking to say, eg *.. BARC – em -des- ar ) and form a block inseparable. If a word has one or more lexemes ( unconstitutional , eg), its meaning is lexical; that is, it appears in the dictionary. If, on the contrary, it lacks lexemes, its meaning is grammatical (or relational), and in the dictionary an explanation of its value and its uses will appear without being able to grant a referential value (it does not refer to any object, action or quality) . Ancient Chinese grammarians called the first words fulland the second, empty words.

The types of money.

Within bound morphemes (which is also called dependent and locked ) we must make a distinction according to their function: they serve to create different forms of the same word (wiped or , wiped os ) are called inflections and that serve to create new words from existing ones are called derivative morphemes s or affixes s , and according to their placement with respect to the lexeme they are called prefix s, if they are placed in front: anti gas, pre fixed; infix s or interfix sif they placed between the stem and the prefix or suffix in s Anchar, POLV ar eda; and suffix s if placed after the lexeme: camin ito , lapic ero .

One issue that can pose problems is to delimit exactly what lexical meaning means from what grammatical meaning means : morphemes -o, -s, -aba , etc., are units with grammatical meaning (that is, they shape purely grammatical) concepts, but – able , – ifica r, pseudo- , etc., they seem to have a lexical meaning and ungrammatical (possibility, causation, falsehood). To explain that despite this they are grammatical morphemes we have to introduce the concept of grammaticalization [2]: Although their meanings originate from non-grammatical realities, these morphemes cannot be words by themselves. They are forms enabled to cover a grammatical need: a linked form is enabled to allow the expression of meanings that are not specific to grammar. Some languages grammatize some concepts, others others: roundness is not a concept that has a morpheme in Spanish that covers it, but the Navajo does; neither intentionality (which the Eskimo does), nor the season or time (yes the Basque: es – aldia ), nor the idea that something we refer to is not an opinion of our own, but that we reflect what another has said, whether or not we agree with our opinion (the Bulgarian does) … Curiously, the tendency to be something but without ever being completely it is grammaticalized in Spanish: it is one of the values of the suffix – oide : intellectual oide . We also grammatize in Spanish the size (by means of the augmentative and diminutive suffixes), the contempt for something (with the derogatory), the concept of fruit tree ( -ero in peach tree , lemon tree , etc., -al in pear tree) and many other non-grammatical, but grammaticalized concepts. The value of these morphemes is, in short, purely grammatical, not lexical. Gramaticalización are other examples of tele – with the value of “television” in Couch Potatoes or , Euro in Euro MP , bus in bonobos , etc. They are morphemes with originally grammatical meaning that indicate gender, number, case, person, voice, time, mode, aspect, grade, and few more; that is, those that belong to the category of flexible morphemes. The morphemes from grammatization are many more and are used to create new words through the process of derivation, which we will study later. They are called derivative morphemes .

Another thing that we have to keep in mind is that the morpheme is a formally minimal unit, not semantically: a morpheme is a unit that cannot be formally divided into smaller segments even if its meaning (the concept it shapes) is decomposable into semantically more basic units : we can decompose the meaning of a rifle into several concepts whose meaning is more general than that of this word: 1. weapon – 2. of fire – 3. portable – 4. used by the infantry, but we cannot segment that word (said lexeme ) in smaller morphological units: ni fu – ni silnor any other segment in which we can divide this word means anything. The smallest unit with meaning (the monema) is rifle and not any of its parts in isolation.

With some morphemes us complicates the picture: what lexical or grammatical meaning has re common in redo, cut and resent ? Of course, the three re- do not seem to mean the same . Because of examples like this, many authors believe that the important thing when identifying a monema is not that it can be given a specific meaning, but that it can be isolated in a morphological segmentation and that it fulfills a function of lexical distinction ( refer and confer differ precisely by the presence of a different morpheme in each). In all these cases we will agree that the morpho re has appeared-, let’s give it the value we give it. It is isolated by segmentation and that could be enough to postulate its existence. We say that could be because the recourse to meaning must always have the last word: no segmental boudoir as Sal on -C- it simply because the word – or salt exists in Castilian and the other morphemes are recognizable in other units: recognize by its meaning a relationship between room and room that does not exist between salt and the last. In the morphological analysis we should take into account morphological, semantic and history factors of the language.

Morphemes, allomorphs and morphs .

Let us return to example 2a: have, have, have, had, had, have had. We will agree that in all these cases we have different forms of the word have , and that they are part of the conjugation of this verb. However, unlike what we have seen so far, these words do not share the same way lexematic : some have the lexeme TEN (have, have had, I’ve had) but there are others with tien – and tuv – . They are different forms, but all will agree Spanish speakers say they are merely variants in the same way TEN . We can postulate that this formten- , is the abstract monema of which the forms ten-, tien – and tuv – are nothing more than concrete realizations in certain phonic environments. We can compare this differentiation with what happens with phonemes, abstract phonic entities that have conditioned virtual variants that we call allophones that are made by means of concrete sounds. Following this parallel, we will say that the morpheme TEN has about alomorf you or virtual variants conditioned by morphological and phonological rules that are made by morpho s :

phonology : phoneme -> allophone -> sound

morphology : morpheme -> allomorph -> morpho

In the case of we have a lexeme (or lexical morpheme) with three possible allomorphs that are made in speech through the three morphs ten-, tien -, tuv – . This also happens with grammatical morphemes: the plural morpheme can appear in the form of several allomorphs:

house / house s armchair / armchair is Monday / Monday ø .

In the previous examples we have seen the three morphs by which we can perform the plural morpheme (of the nouns) in Spanish: -s, -es – ø , (where ø is the absence of morph ).

With the things, it seems very clear the difference between alomorfo and morpho : we will see clearer if we think that abstract morpheme person and number appear inextricably together in a single morpho -amos- in verbal love. There is only one morph that is shared by two morphemes. If we extend the phoneme-monema and allophone-allomorph parallelism to the morphs , we can say that a morph is the concretion in a set of phonemes of one or more monemas, just as a sound is the concretion of a phoneme in speech.

Amalgam morphemes, zero morpheme and discontinuous morphemes.

We have just seen that there are times when in the same morpho two or more morphemes are mixed inseparably: in love we cannot separate in the – é a morph for the notion of “past tense”, another for that of “perfective aspect”, another for “first person” and one for “unique” and various grammatical concepts more like yes we can do it (in part) am -to- ba -s . A single morph “blanket” within itself to several morphemes. These morphs that shape various morphemes are called amalgam ( morphs ) or morphs “portemantea u ” (the French word meaning ‘coat hanger’).

We have also seen that a morpheme can be performed through the absence of morph . These morphs are often called zero morphemes or ø morphemes . This is common in Spanish, which generally has the plural morphs “full” (= no zero ), while the singular is systematically represented by zero morpheme: libroø / books. We can therefore say that a zero morpheme is the significant absence of a morpheme. That there is no morph implies the existence of the opposition with a morpheme that may appear in that position.

Another curiosity that we can find is the fact that there are morphemes represented by two separate morphs . If we take any Spanish verb forms, we realize that there are times that are identified by a final morpheme (ama ste , loves ba s, loves ra s, love would s …) and others who have a morpheme front the lexeme and another after him you love do , you’d love to do , etc. Something similar happens with certain derivational morphemes: a dorm ecer , a bast ecer , in Jaular , in ar paper , etc. that form derivatives of sleep, coarse, cage and paper . In all these examples there are not two morphemes that “collaborate” to create the word in question, but only one, divided into two parts. These types of morphemes are known as discontinuous morphemes .

The word formation systems.

Imagine the following dialogue:

Well, Paco, what are you working on now?

Well, I’m drumming drums for a company in Burgos …

That has to be tough, right?

It depends on whether the drums are easily pambables or not. A normal drumo takes about five minutes, but the pambado of some can take twenty-five or thirty.

It is clear that a normal Spanish speaker will not have understood what the conversation is about. He does not know what a drumo can be and what it is subjected to when he is pambado , but if he is explained what the words pambando and drumos mean , he will have no problem understanding the entire dialogue. This ability to recognize new words is because there is a clear regularity in the processes that serve to form new words in a language. Therefore will not need to be going to explain the meanings of pambable s, pambad or or drumo , as from pambando and drumosYou can obtain the different forms used in the dialogue with the use of word formation systems that work in Spanish. These systems are the bending , the derivation and composition :

Flexion

The bending is the system by which we create new forms of a word by binding inflections a basis , which can be either a lexeme, either a core lexematic formed by more than one morpheme: from lexeme blanc – we create by flexion the word forms white, white, white, white, very white, very white, etc. If instead of taking as a lexematic core a simple lexeme, we start from the blanquead- base , in which we have the lexema blanc – plus the morphemes – ea (cf. blanquear) and the morpheme of participle, we obtain bleached, bleached, etc., following exactly the same processes. Flexion gives a class of flexive morphemes to each lexical category, and so, as we shall see soon, adjectives are given morphemes of gender, number and degree ( -o, -s, – ísim – , etc.), substantive only morphemes number, the adverbs the grade ( lejísimos ), etc., many of which are mandatory for a word can be used (not word blanc – until it does not add a morpheme gender and other number).

When talking about grammarization, we already have an impact on the fact that one language can grammatize some concepts and another, others, but perhaps the most surprising of all this is the fact that grammaticalization itself gives rise to the need for grammatical agreement with some characteristic of the external references with which these morphemes are related. Proof of this is in Spanish the fact that we have to use the female morpheme when talking about a girl and the male morpheme when referring to her brother, or that when telling something that happened yesterday we have to do it using the past forms of verb. There are languages in which gender is not something that characterizes nouns,father / mother in front of brother / sister . In English, for example, a noun has no gender, and something will be masculine or feminine depending on whether its referent belongs to the masculine or feminine sex . For an Englishman it is absurd that the hand is female and the foot male, for example. We will never refer to them using he or she , but it .

Other languages go further by using the so-called classifiers , which are a series of flexible morphemes that must necessarily appear as part of the word, making it “agree” with the object they designate in a series of characteristics such as the fact of being elongated, round or liquid, for example. Imagine that there was a flexible morpheme in Spanish that indicated roundness, say – ondo ; We would have to say things as two manzanondos a pelotondo or bombillondo , for example. We should not be surprised by this: remember the sister / brother opposition. Just as in Spanish, there can be no noun without a number morpheme (even if it is a zero morpheme), or a personal verb without morphemes of time, appearance, person, etc., in these languages you cannot say apple without the Word have a roundness morpheme. And in addition, it must agree with the determinants and adjectives that accompany it: a small apple- shaped apple ring .

Flexive morphemes form closed paradigms. This means that the list of all the flexible morphemes of a language is (synchronously) closed to the admission of new members, unlike what happens with the list of derivative morphemes: think for example of the suffix -ata , so productive in our days: bocata, tocata, drug , etc. On the contrary, it is hard to imagine the appearance of a new plural morpheme of nouns or of appearance in verbs, for example. This is an advantage, because if we could expand the number of flexible morphemes without limits, since all of them would be mandatory for one category or another, our words would be very complicated and endless.

The derivation

The derivation is the formation of new grammatical words (not of forms of the same word, as in flexion) by means of the attachment of derivative morphemes (prefixes, infixes or suffixes) to a base: trough, garbage dump; training, exclusion, work, intellectualoid , reread, flutter, dance, and so on.

Derivative morphemes allow us to use the idea expressed by a lexical base in categories other than the original: we have the white adjective , but if we want to refer to the abstract quality of the white, we have to create a noun derived from the adjective: it is whiteness . If we want to name the action of putting something blank, we must create the derived verb whiten, etc. We jump like this from the lexical category with the lexeme under the arm and transfer it from an adjective notion to a nominal or verbal one, which represents a huge economy of lexemes (or better, lexical bases). Anyway, not always that we use the derivation we change the lexical category of the original word: if instead of using suffixes we derive by means of prefixes or infixes, we will not alter the category: paint> repaint; dance> dance , etc., as we will not do when using augmentative, diminutive and derogatory suffixes.

It is possible to move from any of the major lexical categories to the others: create adjective nouns (that is, coming from adjectives, such as whiteness ), deverbal ( bleaching ) or adverbial ( remoteness ); adjectives denominal ( TV ), deverbales ( deformable ) or adverbiales ( distant ); verbs denominal ( racketeering, alunizar ), adjetivales ( fake ) or adverbiales ( away ) adverbs de adjetivales (all those who finish in -mente and some more) and, more difficultly (?), denominational and deverbal.

Differences between flexion and derivation.

According to Ignacio Bosque (1981: 133-134), these would be the main differences between the way of acting the flexion and the derivation:

Regularity : The meaning of a word with flexive morphemes is easily predictable from the meanings of lexeme and morphemes; this does not happen in words that have derivational morphemes: If old is Old Style + female + plural , we predict that good is good + female + plural , but we can not predict from caning , where we stick + blow from that big dog it means ‘hit with a dog’, for example; if a dumpIt is the place where garbage is thrown, a hat is not the place where shadows are thrown or a truck driver can throw trucks without serious risk of his life.

It is common in languages such as ours that the same morph serves to represent various morphemes: in flexion we have that -or serves in nominal flexion (that of nouns, adjectives and -some-pronouns) to indicate masculine gender, while in verbal inflection indicates first person singular present indicative active: carr or Old Style or against am or . In the derivation the same thing happens: we have already seen that the suffix -ero admits a multitude of different meanings according to the base to which it is attached; the same goes for your doublet -ario ( librarian, bank ) or with -ista : machinist, socialist, revanchist .

Universality within a class. All nouns admit plural morphemes (even if they are zero morphemes), but not all verbs admit the same morphemes: sleep, heal, give birth and labor admit the morpheme – orio with the value of ‘place where the action indicated by the verb ‘: bedroom, hospital, maternity ward, laboratory , but admit not teach, run, smoking , etc.

Derivative morphemes are not necessary to express a certain content because they always admit paraphrases: their meaning can be expressed by lexical means: small house and small house ; unnecessary and not necessary, etc. Inflectional not support this paraphrases (except, of course, the metalanguage: houses equals home + plural )

As we have already mentioned, derivative morphemes can change the lexical category of the base, while flexives always maintain it.

(6 de Bosque) Flexive morphemes are frequently demanded by the syntactic structure. The verb, the adjective, the article, etc., contain a number morpheme to fulfill the grammatical need to agree with a noun; derivative morphemes appear only due to lexical or expressive needs.

The composition.

The composition differs from the previous systems in the fact that it does not start from the union of morphemes to a base, but from the union in the same lexical unit of more than one base , or – according to the more traditional idea of the union two or more words . The degree of formal and semantic component integration can range from a peak melting ( noon sordomudo, stamp, umbrella ) to the relative semantic-formal independence of the members ( floor-pilot, living room, bedroom community , etc.) . To determine this degree of fusion must take into account:

If the two components maintain their accent or if they share one for both: noon has an accent, sleeper with two.

If the plural affects only the second member (total fusion) or the first, noons , but sleeping cars .

It is true that in the composition can only join the core base character is lexemátic or, as they are also compound words but, because , etc., which have joined independent morphemes. This leads us to consider that the composition always starts from the union of several monemas, each of which can function autonomously in the language, and that would allow us to differentiate the composition more clearly from the derivation with grammaticalized morphemes. According to this criterion, the eureaucrat is a derivative and non-compound word, since there are neither * euro nor * crata as autonomous words in Spanish (but see below).

Other ways to create words.

Apart from these more or less regular systems of word formation, there are other less common ones, but they are especially interesting for the speech therapist. Let’s list some:

Lexical coinage : It is the creation of totally new words without (apparently at least) motivation in their origin: gas, kódak .

Language loan or adoption : Very common throughout the history of a language, the loan consists in the adoption and adaptation of a foreign word to the flow of a language. Current cases are, for example, software, parking , etc., even with the original spelling ( crude loan or xenism ), or football, ambigu , etc., already adapted (more or less!) To Spanish.

A special type of loan is the tracing , consisting in the translation of the terms with which a concept is designated to the “borrower” language: tracing cases are skyscrapers (from skyscraper ), mouse -in computing-, which is and while tracing metaphor shuttle space -ing. space shuttle -, re ( tro ) power -ing. feedback , etc.

Cross-linking [5] : Consists of taking only part of each of the words that enter the compound. In Spanish it is relatively rare ( bus , from automobile omnibus -lat technical ‘car colectivo’- and there. Bookmobile ‘ bus-library ‘, and many trade names: Banesto, of Ban Co ‘s locker CREDI to , Bancaya , of Ban co Viz caya ), but we have examples in other languages, such as English smog of smoke + fog , motel , of mo tor + ho tel or Russian Komsomol , of KOMmunistícheskiï Soyu z Molodezh i ‘Union of Communist Youth. ” If we consider that eurócrata is made not by the morpheme euro more – Democrat , but by the prefix Euro plus a shortened form of bureaucrat , we will have the explanation as to why this word is not made but derivative. [6]

Acronymy : It is the creation of words through the union of the initials of several other words: UN, RENFE, UFO, laser, INRI, and so on. : The curious phenomenon that can occur on acronyms bypass occurs peceros ‘PCE militants’ ucedista , laser , etc.

Morphological subtraction : It is the creation of words from the apocope of others: metro ( politano ), cole ( gio ), bike ( cleta ).

Improper qualification or derivation [7] : Use of a word belonging to a lexical category as if it belonged to another: saying in is a saying , where saying has gone from being a verb to a noun; the reds , where we have a noun from an adjective, etc. Sometimes the problem may arise as to whether the transition from one category to another is due to morphological reasons (habilitation) or syntactic means, (substantiation). On this issue, v. Forest (1990: 183-191).

Word is a unit of language that serves as a principal carrier of meaning, consisting of one or more spoken sounds or their written representation. One may define a word as the blocks from which sentences are made. Words consist of one or more morphemes that can be of independent use or consist of two or three such units combined under some connection. Words are usually divided into writing by spaces and in many languages. They are differentiated phonologically, as by accent.

Idioms beginning with Words:

-

word for word

-

word of honour

-

word of mouth

-

words fail me

-

words of one syllable,

-

words stick in one’s throat

-

words to that effect

-

word to the wise

Types of a Word

Word is a speech sound or sequence of speech sounds that typically symbolize and express a message without being divisible into smaller units that can be used separately.

Word is the whole range of linguistic forms generated by combining a single basis with different inflectional elements without altering the part of speech elements.

-

Any part of a written or printed expression that normally occurs between spaces or between a space and a punctuation mark.

-

The act of speaking or talking verbally. A short comment or conversation

-

I just want to have a chat with you.

-

A number of bytes that are processed as a unit and convey a quantity of contact and computer work information

-

To form phrases, we combine words. Typically, a term serves the same purpose as a word from some other class of terms.

What makes a Word Real Word?

In English, the word has a broad variety of meanings and uses. Yet one of the pieces of word-related knowledge most commonly searched for is not something that can be included in its meaning. Instead, what makes a word a real word is some variant of the question?

Vocabulary is one of English’s most prolific fields of change and variation; new terms are constantly being invented to name or characterize new technologies or developments or to better classify aspects of our rapidly changing culture. Time, resources and personnel constraints would make it impossible for any dictionary to capture a completely comprehensive account of all the terms in the language, no matter how big. Most general English dictionaries are intended to contain only terms that fulfil certain usage requirements in large areas and over long periods (for more information about how words are selected for entry in the dictionary).

Classification of Words

Words are grouped in English into parts of speech. The functional adjective and functional adverb are functional derivations.

Noun

A noun is an identifying word:

Eg: An individual (man, female, engineer, friend)

Verb

What a person or thing does or what happens is represented by a verb.

Eg: A case, An action

Adjective

An adjective is a term that identifies a noun, offering additional details about it.

Eg: A thrilling adventure

Adverb

An adverb is a word used to give a verb, adjective or other adverb details. They can make stronger or weaker the meaning of a noun, adjective, or other adverbs, and sometimes appear between the subject and its verb.

Eg: She almost lost everything.

Pronoun

In place of a noun that is already recognized or has already been mentioned, pronouns are used. To stop repeating the noun, this is always done.

Eg: Since she was tired, Laura left early.

Preposition

A preposition is a concept like after, in to, on, and with. Prepositions are normally used in front of nouns or pronouns and illustrate the connection in a sentence between the noun or pronoun and other words.

Conjunction

A conjunction is a term such as and because, but for, if or, and when A conjunction (also called a connective). Conjunctions are used to connect words, clauses, and sentences.

Determiner

A determiner is a phrase that introduces a noun, such as a/an, the any, this, others, or many (as in a dog, the dog, this dog, those dogs, each dog, many dogs).

Exclamation

A word or expression that expresses strong emotions, such as surprise, pleasure, or rage, is an exclamation (also called an interjection). Exclamations sometimes stand on their own.