1)General

features of word-compounding.

2)Structural

and semantic peculiarities of English compounds.

3)Classification

of compounds.

4)The

meaning of compounds.

5)Motivation

of English compounds.

6)Special

groups of compounds.

Word-compounding

is

a way of forming new words combining two or more stems. It’s

important to distinguish between compound words and

word-combinations, because sometimes they look or sound alike. It

happens because compounds originate directly from word-combinations.

The

major feature of compounds is their inseparability

of various kinds: graphic, semantic, phonetic, morphological.

There

is also a syntactic

criterion which helps us to distinguish between words and word

combinations. For example, between the constituent parts of the

word-group other words can be inserted (a

tall handsome

boy).

In

most cases the structural and semantic centre of the compound word

lies on the second component. It shows what part of speech the word

is. The function of the first element is to modify, to determine the

second element. Such compounds (with the structural and semantic

centre “in” the word) are called endocentric.

There

are also exocentric

compounds where the centre lies outside (pickpocket).

Another

type of compound words is called bahuvrihi

– compound nouns or adjectives consisting of two parts: the first

being an adjective, the second – a noun.

There

are several ways to classify compounds. Firstly, they can be grouped

according to their part of speech. Secondly, compounds are grouped

according to the

way the stems are linked together:

morphological compounds (few in number); syntactic compounds (from

segments of speech, preserving articles, prepositions, adverbs).

The

third classification is according to the combinability of compounding

with

other

ways of word-formation:

1) compounds proper (formed by a mere juxtaposition of two stems);

2)

derived or derivational compounds (have affixes in their structure);

3)

converted compounds;

4)

contractive compounds (based on shortening);

5)

compounds based on back formation;

Beside

lexical meanings the components of a compound word have

distributional

and

differential

meanings.

By distributional

meaning

we understand the order, the arrangement of the stems in the word.

The differential

meaning

helps to distinguish two compounds possessing the same element.

The

structural

meaning

of a compound may be described through the interrelation of its

components. e.g. N + Adj (heart-sick

– the relation of cpmparison).

In

most cases compounds are

motivated.

They can be completely motivated, partially motivated, unmotivated.

In partially motivated compounds one of the components (or both) has

changed its original meaning. The meaning of unmotivated compounds

has nothing to do with the meanings of their individual parts.

As

for special groups of compounds, here we distinguish:

a)

reduplicative compounds;

b)

ablaut combinations;

c)

rhyme combinations.

There’s

a certain group of words that stand between compounds and derived.

These are words with so called semi-affixes:

kiss proof

(about

lipstick), fireproof,

foolproof.

Conversion

1)General

problems of conversion in English.

2)Semantic

relations between conversion pairs.

3)

Sources and productivity of conversion.

In

linguistics conversion

is

a type of word-formation; it is a process of creating a new word in a

different part of speech without adding any derivational element. The

morphemic shape of the original word remains unchanged. There are

changes in the syntactical function of the original word, its part of

speech and meaning.

The

question of conversion

has been a controversial one in several aspects. The term conversion

was first used by Henry Sweet at the end of the 19th

century. The nature of conversion has been analyzed by several

linguists. A number of terms have been offered to describe the

process in question.

The

most objective treatment of conversion belongs to Victoria Nikolaevna

Yartseva. According to her, it is a combined morphological,

syntactical and semantic way of word-formation.

The

process was called “non-affixal

derivation”

(Galperin) or “zero

derivation”.

These terms have drawbacks, because there can be other examples of

non-affixal or zero derivation which are not connected with the

process described at the beginning of the lecture.

The

term “functional

change”

(by Arthur Kennedy) also has short-comings. The term implies that the

first word merely changes its function and no new word appears. It

isn’t possible.

The

word conversion

we

use talking about this way of word-formation is not perfect as well.

It means the transformation of something into another thing, the

disappearance of the first word. But the old and the new words exist

together.

The

largest group

related through conversion consists of verbs

converted from nouns.

The relations of the conversion pair in this case can be of the

following kind:

1)

instrumental relations;

2)

relations reflecting some characteristic of the object;

3)

locative relations;

4)

relations of the reverse process, the deprivation of the object.

The

second major division of converted words is deverbial

nouns

(nouns converted from verbs).

They

denote:

1)

an instance of some process;

2)

the object or the result of some action;

3)

the place where the action occurs;

4)

the agent or the instrument of the action.

Conversion

is not only a highly productive but also a particularly English way

of word-building. There are a lot of words in the English language

that are short and morphologically unmarked (don’t indicate any

part of speech). By short words we mean monosyllables, such words are

naturally more mobile and flexible than polysyllables.

In

English verbs and nouns are specially affected by conversion.

Conversion has restrictions. It’s impossible to use conversion if

verbs cannot represent some process as a succession of isolated

actions. Besides, the structure of the first word shouldn’t be

complicated.

Conversion

is typical not only of nouns, verbs and adjectives, but other parts

of speech as well, even such minor elements as interjections and

prepositions or shortened words.

Shortening

1.

General problems of shortening.

2.

Peculiarities of shortenings.

Shortening

stands apart from other ways of word-formation because it doesn’t

produce new words. It produces variants of the same word. The

differences between the new and the original word are in style,

sometimes in their meaning.

There

are two major groups of shortenings (colloquial and written

abbreviations). Among shortenings there can be polysemantic units as

well.

Shortenings

are classified a) according to the position of the shortened part of

the word (clipped words), b) into shortened word combinations, c)

into abbreviations, d) into blendings.

Among

clipped words there are cases of apocope, aphaeresis, and syncope.

Abbreviations can be read as in the alphabet, as one word.

The

Semantic Structure of English Words

1.General

problems of semasiology. The referential and the functional

approaches to the meaning of English words.

2.Types

of meaning.

3.Change

of meaning.

4.Polysemy.

5.Homonymy.

6.Synonyms,

antonyms and other semantic groupings.

The

branch of linguistic which specializes in the study of meaning is

called semantics or semasiology. The modern approach to semantics is

based on the fact that any word has its inner form which is called

the semantic structure.

There

are two main approaches to the meaning of a word: referential and

functional.

The

referential approach is based on the notion of the referent (the

object the word is devoted to). It also operates the notions of the

concept and word. The word and the referent are related only through

the concept. The drawback of the approach is in the fact that it

deals with psychology mostly.

According

to the functional approach the meaning of a word depends on the

function of the word in a sentence. The approach is not perfect

because it can help us only to compare the meanings of words.

Speaking about the meaning of a word both approaches should be

combined.

The

meaning of a word can be divided into grammatical

and

lexical.

The latter is divided into denotational

and

connotational

meanings. The denotational meaning gives the general idea which is

characteristic of a certain word. The connotational meaning combines

the emotive colour and the stylistic value of a word.

The

smallest elements of meaning are called semes.

There

are words with either only the denotational or the connotational

meaning.

Causes

of semantic changes can be extra

linguistic and

linguistic.

Extra linguistic causes are historical in their nature. Among

linguistic causes we distinguish discrimination of synonyms,

ellipsis, linguistic analogy.

As

for the nature of semantic changes, it is connected with some sort of

association between the old and the new meanings. These associations

can be of two types: of similarity (linguistic metaphor), of

contiguity (linguistic metonymy).

The

result of semantic changes can be seen in denotational and

connotational meanings. The denotational meaning can be generalized

or specialized. The connotational meaning can be worsened or

elevated.

Most

words are polysemantic. Monosemantic words are usually found among

terms and scientific words. The ability of words to have more than

one meaning is called polysemy.

Polysemy exists only in the language system.

The

semantic structure of a polysemantic word may be described as a

combination of its semantic variants. Each variant can be described

from the point of view of their denotational and connotational

meaning.

Polysemy

is closely connected with the notion of the context

(the minimum stretch of speech which is sufficient to understand the

meaning of a word). The main types of context are lexical and

grammatical.

Homonyms

are words identical in sound and spelling or at least in one of these

aspects, but different in their meaning. According to Profesor

Smirnitsky homonyms can be divided into two groups: full homonyms

(represent the same part of speech and have the same paradigm),

partial homonyms (don’t coincide either in their spelling or

paradigm).

Another

classification of homonyms deals with homophones

and homographs.

The

sources of homonyms are phonetic changes, borrowing, word-building

(especially conversion), shortening.

There

are several classifications of various word groups. The semantic

similarity and polarity are connected with synonyms and antonyms.

Synonyms

are words different in sound-form but similar in meaning. According

to Vinogradov synonyms can be divided ideographic, stylistic and

absolute. A dominant

synonym

(in any row of synonyms) is more frequent in communication and

contains the major denotational component of the synonyms in

question.

Antonyms

are words belonging to the same part of speech with some opposite

meaning.

As

for other groups of words, there are hyponyms, hyperonyms, semantic

fields, thematic groups.

The

development of the English vocabulary

1.The

development of the vocabulary. Structural and semantic peculiarities

of new vocabulary

units.

2.Ways

of enriching the vocabulary.

If

the language is not dead, it’s developing all the time. The items

that disappear are called archaisms.

They can be found among numerous lexical units and grammatical forms.

New

words or expressions, new meanings of older words are called

neologisms.

The introduction of new words reflects developments and innovations

in the world at large and in society.

Apart

from political terms, neologisms come from the financial world,

computing, pop scene, drug dealing, crime life, youth culture,

education.

Neologisms

come into the language through

1)productive

ways of word formation;

2)ways

without any pattern;

3)semantic

changes of old words;

4)borrowing

from other languages.

There

are numerous cases of blending, compounding, conversion. Borrowed

words mostly come from French, Japanese, the American variant of the

English language.

Соседние файлы в предмете [НЕСОРТИРОВАННОЕ]

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION 3

CHAPTER 1. THEORETICAL BACKGROUNDS OF WORD-COMPOSITION AS A WAY OF

WORD-FORMATION IN ENGLISH 6

1.1 The means of word-formation in English language 6

1.2 The concept and the essence word-composition 14

CHAPTER 2. STRUCTURAL-SEMANTIC AND FUNCTIONAL FEATURES OF COMPOUND WORDS 19

2.1 The analysis of semantic features of compound words 19

2.2 The analysis of functional features of compound words 24

CHAPTER 3. ANALYTICAL BASES OF USE OF WORD-COMPOSITION 36

3.1 Practical examples of compound words in modern English 36

3.2 New tendencies of use of word-composition as a way of word-formation in

English 38

CONCLUSION 41

LITERATURE 44

APPENDIXES 46

Appendix 1 46

Appendix 2 49

Appendix 3 52

Appendix 4 54

INTRODUCTION

In linguistics, word formation is the creation of a new word. Word formation is sometimes contrasted with semantic

change, which is a change in a

single word’s meaning. The line between word formation and semantic

change is sometimes a bit

blurry; what one person views as a new use of an old word, another person might

view as a new word derived from an old one and identical to it in form. Word

formation can also be contrasted with the formation of idiomatic expressions, though sometimes words can form from

multi-word phrases.

The

subject-matter of the Course Paper is to investigate the

word – composition in the English system of word – formation.

The

topicality of the problem results from the necessity to devote

to description of theoretical bases of allocation of word-composition as way of

word-formation in modern English language.

The

novelty of the problem arises from the necessity to define the

role of word-composition way which is, along with abbreviations, stays one of

the most productive for last decades..

The

main aim of the Course Paper is to summarize and systemize

different methods of word — composition in English.

The

aim

of the course Paper presupposes the solutions of the following tasks:

·

To

expand and update the definition of the term “word — composition”

·

to

define the role of word-composition

According the tasks of the Course

Paper its structure is arranged in the following way:

Introduction,

the Main Part, Conclusion, Resume, Literature, test of Reference Material, List

of Electronic References.

In

the Introduction we provide the explanation of the theme choice, state the

topicality of it, establish the main aim, and the practical tasks of the Paper.

In

the main part we analyze

the character features of the modern classification of word – composition in

the English system of word – formation.

In conclusion we

generalize the results achieved.

CHAPTER 1. THEORETICAL BACKGROUNDS OF WORD-COMPOSITION AS A

WAY OF WORD-FORMATION IN ENGLISH LANGUAGE.

1.1 The means of word-composition in English language The chapter is devoted to

description of theoretical bases of allocation of word-composition as way of

word-formation in modern English language. We try to define the role of

word-composition way which is, along with abbreviations, stays one of the most

productive for last decades. The main way of enrichment of lexicon of any

language is word-formation. All innovations in branches of human knowledge are

fixed in new words and expressions.

The

word-formation system of language is in constant development, as it reflects

evolution of the language. At different stages of language development ways of

word-formation become more or less productive. However there are also ways of

the word-formation which stay productive for a very long time. One of such

methods is word-composition.

Word-composition is a very ancient way of word-formation, and it

serves as powerful tool of the replenishment of language and its grammatical

system perfection for hundred years.

Many researches are devoted composition studying. So, the

considerable contribution to studying of this problem was brought by V.Guz’s,

G.Marchand’s, S.Ulman’s researches, and also the studies of I.V.Arnold,

N.V.Kosarev, E.S.Kubrjakov, O.D.Meshkova, V.J.Ryazanov, A.I.Smirnitsky,

M.D.Stepanova, M.V.Tsareva. That is the problem is widely studied both in domestic,

and in foreign practice.

However it should be noticed that the majority of word-composition studies

concern 70-80 years of the last century, and during last 20 years no serious

researches appeared.

Besides,

the analysis of researches reveals considerable confrontation in opinions of

different authors both in questions of defying the concept of word-formation,

and in approaches of classification of its kinds. There

are different

opinions in concerning quantity of ways of word-formation.

These divergences speak that various ways change the activity and

become more or less productive in a definite period. Anyhow, it is conventional

that modern English has different ways of word-formation: Affixation, suffixation, shortening, prefixation, conversion and

composition or compound. Compounding or word-composition is

one of the productive types of word-formation in Modern English. Composition

like all other ways of deriving words has its own peculiarities as to the means used, the nature of

bases and their distribution, as to the range of application, the scope of

semantic classes and the factors conducive to productivity. Compounding or

word composition is one of the productive types of

word-formation in Modern English. Composition like all other ways of deriving

words has its own peculiarities as to the means used , the nature of bases

and their distribution , as to the range of application , the scope of

semantic classes and the factors conducive to productivity. Compounds are

made up of two ICs which are both derivational bases. Compound words are

inseparable vocabulary units. They are formally and semantically dependent on

the constituent bases and the semantic relations between them which mirror the

relations between the motivating units. The ICs of compound words represent

bases of all three structural types.

1.

The

bases built on stems may be of different degree

2. Of complexity as,

e.g., week-end,

office-management, postage-stamp, aircraft-carrier, fancy-dress-maker, etc. However, this complexity of

structure of bases is not typical of the bulk of Modern English compounds. In this connection

care should be taken not to confuse compound words with polymorphic words of

secondary derivation, i.e. derivatives built according to an affixal

pattern but on a compound stem for its base such as, e.g., school-mastership ([n+n]+suf), ex—housewife (prf+[n+n]),to weekend, to

spotlight ([n+n]+conversion).

CHAPTER 2. STRUCTURAL-SEMANTIC AND FUNCTIONAL

FEATURES OF COMPOUND WORDS

2.1 Structural

features

Compound words like all

other inseparable vocabulary units take shape in a definite system of

grammatical forms, syntactic and semantic features. Compounds, on the one hand,

are generally clearly distinguished from and often opposed to free word-groups,

on the other hand they lie astride the border-line between words and

word-groups and display close ties and correlation with the system of free

word-groups. The structural inseparability of compound words

finds expression in the unity of their specific

distributional pattern and specific

stress

and spelling pattern.

Structurally compound

words are characterized by the specific order and arrangement in which bases

follow one another. The order in which the two bases are placed within a

compound is rigidly fixed in

Modern English and it is the second IC that makes the head-member of the word,

i.e. its structural and semantic centre. The head-member is of basic importance

as it preconditions both the lexico-grammatical and semantic features of the

first component. It is of interest to note that the difference between stems

(that serve as bases in compound words) and word-forms they coincide with is most

obvious in some compounds, especially in compound adjectives. Adjectives

like long, wide,

rich are

characterized by grammatical forms of degrees of comparison longer, wider, richer. The

corresponding stems functioning as bases in compound words lack grammatical

independence and forms proper to the words and retain only the part-of-speech

meaning; thus compound adjectives with adjectival stems for their second

components, e. g. age-long, oil-rich, inch-wide, do not form degrees of comparison as the compound

adjective oil-rich does not form

them the way the word rich does, but conforms to the general rule of

polysyllabic adjectives and has analytical forms of degrees of comparison. The

same difference between words and stems is not so noticeable in compound nouns

with the noun-stem for the second component.

Phonetically compounds

are also marked by a specific structure of their own. No phonemic changes of

bases occur in composition but the compound word acquires a new stress pattern,

different from the stress in the motivating words, for example words key and hole or hot and house each possess

their own stress but when the stems of these words are brought together to make

up a new compound word, ‘keyhole — ‘a hole in a lock into which a key fits’, or ‘hothouse — ‘a heated

building for growing delicate plants’, the latter is given a different stress

pattern — a unity stress on the first component in our case. Compound words

have three stress patterns: a high or unity stress on the first component as

in ‘honeymoon,

‘doorway, etc. a double stress, with a primary stress on the first

component and a weaker, secondary stress on the second component, e. g. ‘blood-ֻvessel, ‘mad-ֻdoctor, ‘washing-ֻmachine,

etc. It is not infrequent, however, for both ICs to have level stress as in,

for instance, ‘arm-‘chair,

‘icy-‘cold, ‘grass-‘green, etc.

Graphically most

compounds have two types of spelling — they are spelt either solidly or with a

hyphen. Both types of spelling when accompanied by structural and phonetic

peculiarities serve as a sufficient indication of inseparability of compound

words in contradistinction to phrases. It is true that hyphenated spelling by

itself may be sometimes misleading, as it may be used in word-groups to

emphasize their phraseological character as in e. g. daughter-in-law, man-of-war,

brother-in-arms or in longer combinations of words to indicate

the semantic unity of a string of words used attributively as, e.g., I-know-what-you’re-going-to-say

expression, we-are-in-the-know jargon, the young-must-be-right attitude. The two types of

spelling typical of compounds, however, are not rigidly observed and there are

numerous fluctuations between solid or hyphenated spelling on the one hand and

spelling with a break between the components on the other, especially in

nominal compounds of then+n type. The spelling of these compounds varies

from author to author and from dictionary to dictionary. For example, the

words war-path,

war-time, money-lender are spelt both with a hyphen and solidly; blood-poisoning, money-order,

wave-length, war-ship— with a hyphen and with a break; underfoot, insofar, underhand—solidly

and with a break25.

It is noteworthy that new compounds of this type tend to solid or hyphenated

spelling. This inconsistency of spelling in compounds, often accompanied by a

level stress pattern (equally typical of word-groups) makes the problem of

distinguishing between compound words (of the n + n type in particular) and word-groups

especially difficult.

In

this connection it should be stressed that Modern English nouns (in the Common

Case, Sg.) as has been universally recognized possess an attributive function

in which they are regularly used to form numerous nominal phrases as, e.

g. peace years,

stone steps, government office, etc. Such variable nominal phrases are semantically

fully derivable from the meanings of the two nouns and are based on the

homogeneous attributive semantic relations unlike compound words. This system

of nominal phrases exists side by side with the specific and numerous classes

of nominal compounds which as a rule carry an additional semantic component

not found in phrases.

It

is also important to stress that these two classes of vocabulary units —

compound words and free phrases — are not only opposed but also stand in close

correlative relations to each other.

2.2

Semantic features

Semantically compound

words are generally motivated units. The meaning of the compound is first of

all derived from the combined lexical meanings of its components. The semantic

peculiarity of the derivational bases and the semantic difference between the

base and the stem on which the latter is built is most obvious in compound

words. Compound words with a common second or first component can serve as

illustrations. The stem of the word board is polysemantic and its multiple meanings serve as

different derivational bases, each with its own selective range for the

semantic features of the other component, each forming a separate set of

compound words, based on specific derivative relations. Thus the base board meaning ‘a flat

piece of wood square or oblong’ makes a set of compounds chess-board, notice-board,

key-board, diving-board, foot-board, sign-board; compounds paste-board, cardboard are built on the

base meaning ‘thick, stiff paper’; the base board– meaning ‘an authorized body of men’, forms

compounds school-board,

board-room. The

same can be observed in words built on the polysemantic stem of the word foot. For example,

the base foot– in foot-print, foot-pump,

foothold, foot-bath, foot-wear has the meaning of ‘the terminal

part of the leg’, in foot-note, foot-lights, foot-stone the base foot– has the

meaning of ‘the lower part’, and in foot-high, foot-wide, footrule — ‘measure of

length’. It is obvious from the above-given examples that the meanings of the

bases of compound words are interdependent and that the choice of each is

delimited as in variable word-groups by the nature of the other IC of the word.

It thus may well be said that the combination of bases serves as a kind of

minimal inner context distinguishing the particular individual lexical meaning

of each component. In this connection we should also remember the significance

of the differential meaning found in both components which becomes especially

obvious in a set of compounds containing identical bases.

CLASSIFICATION

OF WORD — COMPOSITION

Compound

words can be described from different points of view and consequently may be

classified according to different principles. They may be viewed from the point

of view:

·

of

general relationship and degree of semantic independence of components;

·

of

the parts of speech compound words represent;

·

of

the means of composition used to link the two ICs together;

·

of

the type of ICs that are brought together to form a compound;

·

of

the correlative relations with the system of free word-groups.

From the point of view of degree of semantic independence there are two types

of relationship between the ICs of compound words that are generally

recognized in linguistic literature: the relations of coordination and

subordination, and accordingly compound words fall into two classes: coordinative compounds (often

termed copulative or additive) and subordinative (often termed determinative).

In coordinative compounds

the two ICs are semantically equally important as in fighter-bomber, oak-tree,

girl-friend, Anglo-American. The constituent bases belong to the

same class and той often to the same

semantic group. Coordinative compounds make up a comparatively small group of

words. Coordinative compounds fall into three groups:

1.

Reduplicative compounds

which are made up by the repetition of the same base as in goody-goody, fifty-fifty,

hush-hush, pooh-pooh. They are all only partially motivated.

2.

Compounds

formed by joining the phonically variated rhythmic twin forms which either

alliterate with the same initial consonant but vary the vowels as in chit-chat, zigzag, sing-song, or

rhyme by varying the initial consonants as in clap-trap, a walky-talky, helter-skelter. This subgroup

stands very much apart. It is very often referred to pseudo-compounds and

considered by some linguists irrelevant to productive word-formation owing to

the doubtful morphemic status of their components. The constituent members of

compound words of this subgroup are in most cases unique, carry very vague or

no lexical meaning of their own, are not found as stems of independently

functioning words. They are motivated mainly through the rhythmic doubling of

fanciful sound-clusters.

3.

Coordinative compounds of both subgroups

(a, b) are mostly restricted to the colloquial layer, are marked by a heavy

emotive charge and possess a very small degree of productivity.

The bases of additive compounds such as a queen-bee, an actor-manager,

unlike the compound words of the first two subgroups, are built on stems of the

independently functioning words of the same part of speech. These bases often

semantically stand in the genus-species relations. They denote a person or an

object that is two things at the same time. A secretary-stenographer is thus a person who is

both a stenographer and a secretary, a bed-sitting-room (a bed-sitter) is both a bed-room and a sitting-room at

the same time. Among additive compounds there is a specific subgroup of

compound adjectives one of ICs of which is a bound root-morpheme. This group is

limited to the names of nationalities such as Sino-Japanese, Anglo-Saxon, Afro-Asian, etc.

Additive compounds of this group are

mostly fully motivated but have a very limited degree of productivity.

However it must be stressed that though

the distinction between coordinative and subordinative compounds is generally

made, it is open to doubt and there is no hard and fast border-line between

them. On the contrary, the border-line is rather vague. It often happens that

one and the same compound may with equal right be interpreted either way — as a

coordinative or a subordinative compound, e. g. a woman-doctor may be

understood as ‘a woman who is at the same time a doctor’ or there can be traced

a difference of importance between the components and it may be primarily felt

to be ‘a doctor who happens to be a woman’ (also a mother-goose, a clock-tower). In

subordinative compounds the components are neither structurally nor

semantically equal in importance but are based on the domination of the

head-member which is, as a rule, the second IC. The second IC thus is the

semantically and grammatically dominant part of the word, which preconditions

the part-of-speech meaning of the whole compound as in stone-deaf, age-long which

are obviously adjectives, a wrist-watch, road-building, a baby-sitter which

are nouns.

Functionally compounds are viewed as words

of different parts of speech. It is the head-member of the compound, i.e. its

second IC that is indicative of the grammatical and lexical category the

compound word belongs to.

Compound words are found in all parts of

speech, but the bulk of compounds are nouns and adjectives. Each part of

speech is characterized by its set of derivational patterns and their semantic

variants. Compound adverbs, pronouns and connectives are represented by an

insignificant number of words, e. g. somewhere, somebody, inside, upright, otherwise moreover,

elsewhere, by means of, etc. No new compounds are coined on this pattern.

Compound pronouns and adverbs built on the repeating first and second IC

like body, ever,

thing make

closed sets of words

SOME |

+ |

BODY |

ANY |

THING |

|

EVERY |

ONE |

|

NO |

WHERE |

On the whole composition is not productive

either for adverbs, pronouns or for connectives. Verbs are of special

interest. There is a small group of compound verbs made up of the combination

of verbal and adverbial stems that language retains from earlier stages, e.

g. to bypass, to

inlay, to offset. This type according to some authors, is no longer

productive and is rarely found in new compounds. There are many polymorphic

verbs that are represented by morphemic sequences of two root-morphemes,

like to weekend,

to gooseflesh, to spring-clean, but derivationally they are all words of secondary

derivation in which the existing compound nouns only serve as bases for

derivation. They are often termed pseudo-compound verbs. Such polymorphic

verbs are presented by two groups: 1)verbs formed by means of conversion from

the stems of compound nouns as in to spotlight from a spotlight, to sidetrack from a side-track, to

handcuff from handcuffs, to blacklist from a blacklist, to

pinpoint from a pin-point;

2) verbs formed by back-derivation from

the stems of compound nouns, e. g. to baby-sit from a baby-sitter, to playact from play-acting, to

housekeep from house-keeping, to spring-clean from spring-cleaning.

From the point of view of the means by

which the components are joined together, compound words may be classified

into:

Words formed by merely placing one constituent

after another in a definite order which thus is indicative of both

the semantic value and the morphological unity of the compound, e. g. rain-driven, house-dog,

pot-pie (as opposed to dog-house, pie-pot). This means of linking

the components is typical of the majority of Modern English compounds in all

parts of speech.

As to the order of components,

subordinative compounds are often classified as:

Ø asyntactic compounds in which the order of

bases runs counter to the order in which the motivating words can be brought

together under the rules of syntax of the language. For example, in variable

phrases adjectives cannot be modified by preceding adjectives and noun

modifiers are not placed before participles or adjectives, yet this kind of

asyntactic arrangement is typical of compounds, e. g. red-hot, bluish-black,

pale-blue, rain-driven, oil-rich. The asyntactic order is

typical of the majority of Modern English compound words;

Ø syntactic compounds whose components are

placed in the order that resembles the order of words in free phrases arranged

according to the rules of syntax of Modern English. The order of the components

in compounds like blue-bell, mad-doctor, blacklist ( a + n ) reminds one of the order and

arrangement of the corresponding words in phrases a blue bell, a mad doctor, a

black list (

A + N ), the order of compounds of the typedoor-handle, day-time,

spring-lock (

n + n ) resembles the order of words in nominal phrases with

attributive function of the first noun ( N + N ),e. g. spring time, stone steps, peace movement.

Ø Compound words whose ICs are joined

together with a

special linking-element — the linking vowels [ou] and occasionally

[i] and the linking consonant [s/z] — which is indicative of composition as in,

for example, speedometer,

tragicomic, statesman. Compounds of this type can be both nouns and

adjectives, subordinative and additive but are rather few in number since they

are considerably restricted by the nature of their components. The additive

compound adjectives linked with the help of the vowel [ou] are limited to the

names of nationalities and represent a specific group with a bound root for the

first component, e. g. Sino-Japanese, Afro-Asian, Anglo-Saxon.

In subordinative adjectives and nouns the

productive linking element is also [ou] and compound words of the type are most

productive for scientific terms. The main peculiarity of compounds of the type

is that their constituents are non-assimilated bound roots borrowed mainly from

classical languages, e. g. electro-dynamic, filmography, technophobia, videophone,

sociolinguistics, videodisc.

A small group of compound nouns may also

be joined with the help of linking consonant [s/z], as in sportsman, landsman,

saleswoman, bridesmaid.This small group of words is restricted by the second

component which is, as a rule, one of the three bases man–, woman–, people–.

The commonest of them is man–.

Compounds may be also classified according

to the nature of the bases and the interconnection with other ways of

word-formation into the so-called compounds proper and derivational compounds.

Compounds

proper are formed by joining together bases

built on the stems or on the word-forms of independently functioning words with

or without the help of special linking element such as doorstep, age-long,

baby-sitter, looking-glass, street-fighting, handiwork, sportsman. Compounds

proper constitute the bulk of English compounds in all parts of speech, they

include both subordinative and coordinative classes, productive and

non-productive patterns.

Derivational

compounds, e. g. long-legged, three-cornered, a

break-down, a pickpocket differ from compounds proper in the nature of bases

and their second IC. The two ICs of the compound long-legged — ‘having long

legs’ — are the suffix –ed meaning ‘having’ and the base built on a free

word-group long

legs whose

member words lose their grammatical independence, and are reduced to a single

component of the word, a derivational base. Any other segmentation of such

words, say into long– and legged– is impossible

because firstly, adjectives like *legged do not exist in Modern English and secondly, because

it would contradict the lexical meaning of these words. The derivational

adjectival suffix –ed converts this newly formed base into a word. It can be

graphically represented as long legs à [ (long–leg) + –ed] à long–legged.

The suffix –ed becomes the grammatically

and semantically dominant component of the word, its head-member. It imparts

its part-of-speech meaning and its lexical meaning thus making an adjective

that may be semantically interpreted as ‘with (or having) what is denoted by

the motivating word-group’. Comparison of the pattern of compounds proper

like baby-sitter,

pen-holder

[ n +

( v + –er ) ] with the pattern of derivational compounds

like long-legged [ (a + n) + –ed ] reveals the

difference: derivational compounds are formed by a derivational means, a suffix

in case if words of the long-legged type, which is applied to a base that each time is

formed anew on a free word-group and is not recurrent in any other type if

words. It follows that strictly speaking words of this type should be treated

as pseudo-compounds or as a special group of derivatives. They are habitually

referred to derivational compounds because of the peculiarity of their

derivational bases which are felt as built by composition, i.e. by bringing

together the stems of the member-words of a phrase which lose their

independence in the process. The word itself, e. g. long-legged, is built by the

application of the suffix, i.e. by derivation and thus may be described as a

suffixal derivative.

Derivational compounds or pseudo-compounds

are all subordinative and fall into two groups according to the type of variable

phrases that serve as their bases and the derivational means used:

Ø derivational

compound adjectives formed

with the help of the highly-productive adjectival suffix –ed applied to bases

built on attributive phrases of the A + N, Num + N, N + N type, e. g. long legs, three corners, doll

face. Accordingly

the derivational adjectives under discussion are built after the patterns [ (a + n ) + –ed], e.

g. long-legged,

flat-chested, broad-minded; [ ( пит + n) + –ed], e. g. two-sided, three-cornered; [ (n + n ) + –ed], e. g. doll-faced, heart-shaped.

Ø derivational

compound nouns formed

mainly by conversion applied to bases built on three types of variable phrases

— verb-adverb phrase, verbal-nominal and attributive phrases.

The commonest type of phrases that serves

as derivational bases for this group of derivational compounds is the V + Adv type

of word-groups as in, for instance, a breakdown, a breakthrough, a castaway, a layout.

Semantically derivational compound nouns form lexical groups typical of

conversion, such as an act or instance of the action, e. g. a holdup — ‘a delay in

traffic’’ from to

hold up — ‘delay, stop by use of force’; a result of the

action, e. g. a

breakdown —

‘a failure in machinery that causes work to stop’ from to break down — ‘become

disabled’; an active agent orrecipient of the action, e. g. cast-offs — ‘clothes that he

owner will not wear again’ from to cast off — ‘throw away as unwanted’; a show-off —

‘a person who shows off’ from to show off — ‘make a display of one’s abilities

in order to impress people’. Derivational compounds of this group are spelt

generally solidly or with a hyphen and often retain a level stress.

Semantically they are motivated by transparent derivative relations with the

motivating base built on the so-called phrasal verb and are typical of the

colloquial layer of vocabulary. This type of derivational compound nouns is

highly productive due to the productivity of conversion.

The semantic subgroup of derivational

compound nouns denoting agents calls for special mention. There is a group of

such substantives built on an attributive and verbal-nominal type of phrases.

These nouns are semantically only partially motivated and are marked by a heavy

emotive charge or lack of motivation and often belong to terms as, for

example, a

kill-joy, a wet-blanket — ‘one who kills enjoyment’; a turnkey —

‘keeper of the keys in prison’; a sweet-tooth — ‘a person who likes sweet

food’; a

red-breast — ‘a bird called the robin’. The analysis of these

nouns easily proves that they can only be understood as the result of

conversion for their second ICs cannot be understood as their structural or

semantic centres, these compounds belong to a grammatical and lexical groups

different from those their components do. These compounds are all animate

nouns whereas their second ICs belong to inanimate objects. The meaning of the

active agent is not found in either of the components but is imparted as a

result of conversion applied to the word-group which is thus turned into a

derivational base.

These compound nouns are often referred to

in linguistic literature as «bahuvrihi» compounds or exocentric compounds, i.e.

words whose semantic head is outside the combination. It seems more correct to

refer them to the same group of derivational or pseudo-compounds as the above

cited groups.

This small group of derivational nouns is

of a restricted productivity, its heavy constraint lies in its idiomaticity and

hence its stylistic and emotive colouring.

The linguistic analysis of extensive language

data proves that there exists a regular correlation between the system of free

phrases and all types of subordinative (and additive) compounds26. Correlation

embraces both the structure and the meaning of compound words, it underlies the

entire system of productive present-day English composition conditioning the

derivational patterns and lexical types of compounds.

Compounds are words produced by combining

two or more stems which occur in the language as free forms. They may be classified

proceeding from different criteria:

according to the parts of speech to which

they belong;

according to the means of composition used

to link their ICs together;

according to the structure of their ICs;

according to their semantic characteristics.

3.1 Correlation

types of compounds

The

description of compound words through the correlation with variable word-groups

makes it possible to classify them into four major classes: adjectival-nominal,

verbal-nominal, nominal and verb – adverb compounds.

I. A d j e c t i v a l — n o m i n a l

comprise four subgroups of compound

adjectives, three of them are proper

compounds and one derivational.

All four subgroups are productive and

semantically as a rule motivated.

The main constraint on the productivity in

all the four subgroups is

the lexical-semantic types of the

head-members and the lexical valency of

the head of the correlated word-groups.

Adjectival-nominal compound adjectives

have the following patterns:

1) the polysemantic n+a

pattern

that gives rise to two types:

a) compound adjectives based on semantic

relations of resemblance

with adjectival bases denoting most

frequently colours, size, shape, etc. for

the second IC. The type is correlative

with phrases of comparative type as

A +as + N,

e.g.

snow-white,

skin-deep, age-long, etc.

b) compound adjectives based on a variety

of adverbial relations. The

type is correlative with one of the most

productive adjectival phrases of

the A +

prp

+

N

type

and consequently semantically varied, cf. colourblind,

road-weary, care-free, etc.

2) the monosemantic pattern n+ven

based

mainly on the instrumental, locative and temporal relations between the ICs

which are:

conditioned by the lexical meaning and

valency of the verb, e.g. stateowned,

home-made. The type is highly

productive. Correlative relations

are established with word-groups of the Ven+

with/by

+

N

type.

3) the monosemantic пит

+

п pattern

which gives rise to a small and

peculiar group of adjectives, which are

used only attributively, e.g. (a) twoday

(beard), (a) seven-day

(week),

etc. The type correlates with attributive

phrases with a numeral for their first

member.

4) a highly productive monosemantic

pattern of derivational compound

adjectives based on semantic relations of

possession conveyed by the suffix

-ed. The basic variant is [(a+n)+ -ed],

e.g.

low-ceilinged,

long- legged.

The pattern has two more variants: [(пит

+

n)

+

-ed),

l(n+n)+ -ed], e.g.

one-sided, bell-shaped, doll-faced. The

type correlates accordingly with

phrases with (having) + A+N,

with

(having) + Num +

N,

with

+

N + N

or with +

N + of + N.

The system of productive types of compound

adjectives is summarised

in Table 1. (Appendix)

II. V e r b a l — n o m i n a l compounds

may be described through one derivational structure n+nv,

i.e.

a combination of a noun-base (in most

cases simple) with a deverbal, suffixal

noun-base. The structure includes

four patterns differing in the character

of the deverbal noun- stem and accordingly

in the semantic subgroups of compound

nouns. All the patterns

correlate in the final analysis with V+N

and

V+prp+N

type

which depends

on the lexical nature of the verb:

1) [n+(v+-er)],

e.g.

bottle-opener,

stage-manager, peace-fighter. The

pattern is monosemantic and is based on

agentive relations that can be interpreted

‘one/that/who does smth’.

2) [n+(v+

-ing)],

e.g.

stage-managing,

rocket-flying. The pattern is

monosemantic and may be interpreted as

‘the act of doing smth’. The pattern

has some constraints on its productivity

which largely depends on the

lexical and etymological character of the

verb.

3) [n+(v+ -tion/ment)], e.g.

office-management,

price-reduction. The

pattern is a variant of the above-mentioned

pattern (No 2). It has a heavy

constraint which is embedded in the

lexical and etymological character of

the verb that does not permit

collocability with the suffix -ing or deverbal

nouns.

4) [n+(v +

conversion)],

e.g.

wage-cut,

dog-bite, hand-shake, the pattern

is based on semantic relations of result,

instance, agent, etc.

III. N o m i n a l c o m p o u n d s are

all nouns with the most

polysemantic and highly-productive

derivational pattern n+n; both bases

re generally simple stems, e.g. windmill,

horse-race, pencil-case. The

pattern conveys a variety of semantic

relations, the most frequent are the

relations of purpose, partitive, local and

temporal relations. The pattern

correlates with nominal word-groups of the

N+prp+N

type.

IV. V e r b — a d v e r b compounds are

all derivational nouns, highly

productive and built with the help of

conversion according to the pattern l(v + adv) + conversion].

The

pattern correlates with free phrases

V + Adv

and

with all phrasal verbs of different degree of stability. The pattern

is polysemantic and reflects the manifold

semantic relations typical of

conversion pairs.

The system of productive types of compound

nouns is summarized in

Table

2. (Appendix)

ANALYTICAL BASES

OF USE OF WORD-COMPOSITION 36

3.1 Practical examples of compound words.

Here are the

practical examples of compound words in “Theater” of W. Somerset Maugham.

Business – like [n+(v

+

conversion)],

is

based on semantic relations of result, – довольно по

деловому

(ch.1 p 3)

well – known

(ch

1 p

4) [a+v]

– хорошо известный

ink – stand (ch 1 p 4) [n+v] —

чернильница

heavily – painted lips (ch 1 p 5)

[a+v+ed] ярко- накрашенные губы

dressing – table (ch 1 p

туалетный

столик

eyebrow — (ch 1 p

satinwood — (ch 1 p

атласное дерево

CONCLUSION

1. Compound words are made up of two ICs,

both of which are derivational bases.

2. The structural and semantic centre of

acompound, i.e. its head-member, is its second IC, which preconditions the part

of speech the compound belongs to and its lexical class.

3. Phonetically compound words are marked

by three stress patterns

— a unity stress, a double stress and a

level stress. The first two are the

commonest stress patterns in compounds.

4. Graphically as a rule compounds are

marked by two types of spelling

— solid spelling and hyphenated spelling.

Some types of compound

words are characterised by fluctuations

between hyphenated spelling and

spelling with a space between the components.

5. Derivational patterns in compound words

may be mono- and

polysemantic, in which case they are based

on different semantic relations

between the components.

6. The meaning of compound words is

derived from the combined

lexical meanings of the components and the

meaning of the derivational

pattern.

7. Compound words may be described from

different points of view:

a) According to the degree of semantic

independence of components

compounds are classified into coordinative

and subordinative. The bulk of

present-day English compounds are

subordinative.

b) According to different parts of speech.

Composition is typical in

Modern English mostly of nouns and

adjectives.

c) According to the means by which

components are joined together

they are classified into compounds formed

with the help of a linking element

and without. As to the order of ICs it may

be asyntactic and syntactic.

d) According to the type of bases

compounds are classified into compounds

proper and derivational compounds.

e) According to the structural semantic

correlation with free phrases

compounds are subdivided into

adjectival-nominal compound adjectives,

verbal-nominal, verb-adverb and nominal

compound nouns.

8. Structural and semantic correlation is

understood as a regular interdependence

between compound words and variable

phrases. A potential

possibility of certain types of phrases

presupposes a possibility of compound

words

conditioning their structure and semantic type.

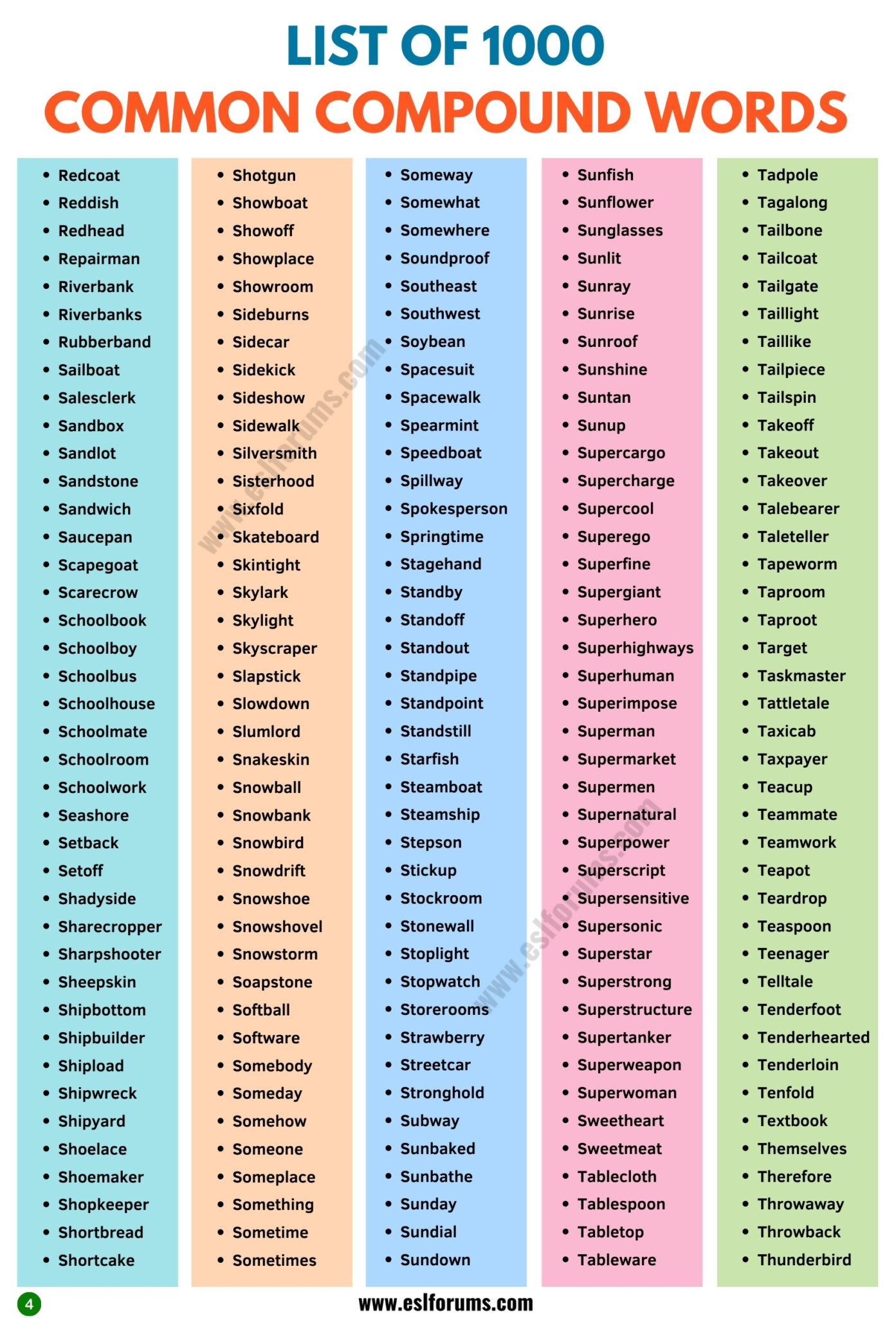

APPENDIX

TABLE 1. Productive Types of

Compound Adjectives

|

Free |

Compound |

|||

|

Compounds |

Derivational Compounds |

Pattern |

Semantic |

|

|

1) (a). as white |

snow-white |

— |

n |

relations |

|

(b). in tired care-free, |

oil-rich, power-greedy, pleasuretired |

— |

— |

various adverbial relations |

|

2.c bound |

snow-covered duty-bound |

n |

instrumental (or agentive relations |

|

|

3. two days |

(a) two-day (beard) (b) seven-year (plan) |

— |

num |

quantitative |

|

wi t h ( h a v i |

long-legged |

[(a |

possessive |

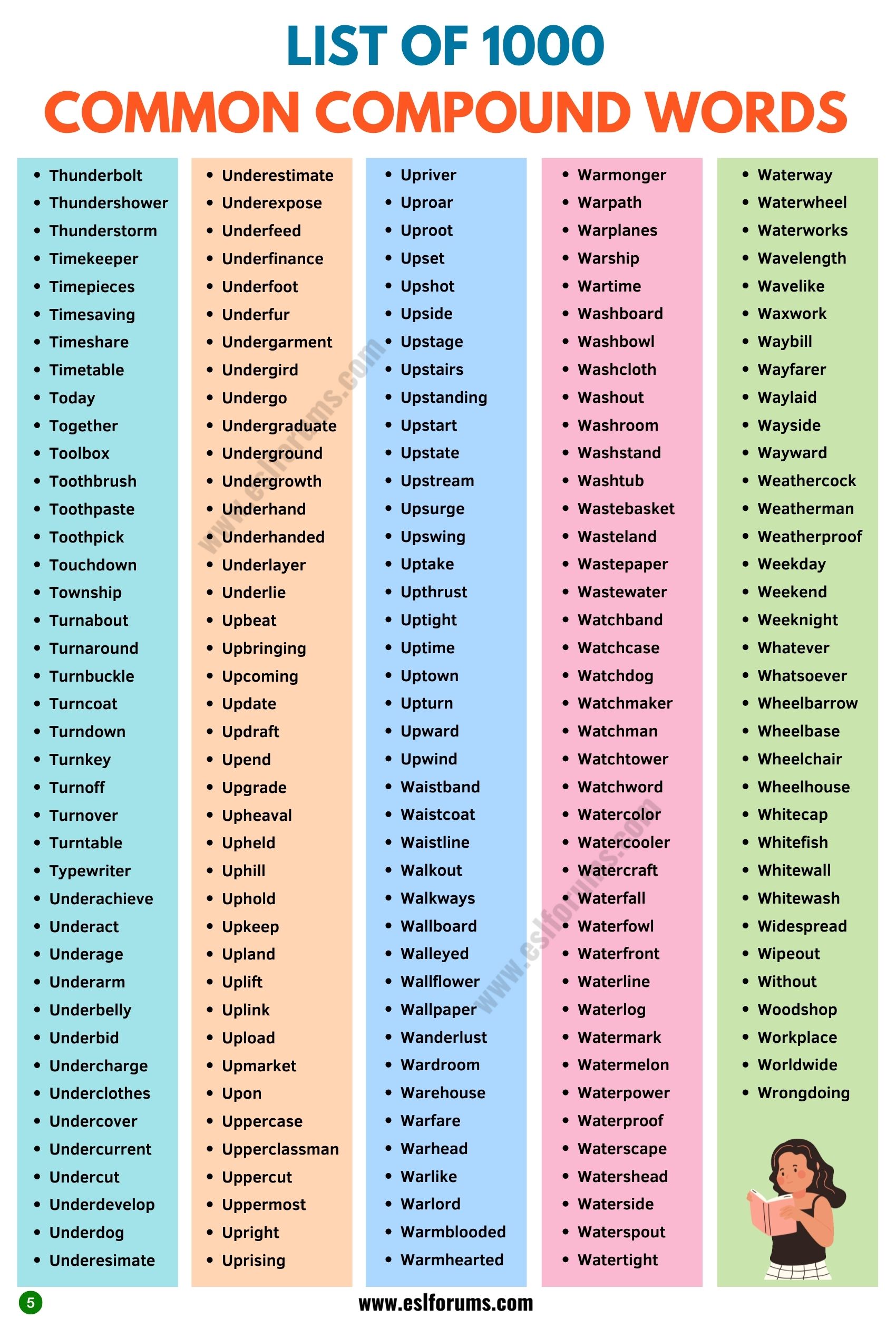

APENDIX 2.

TABLE 2. Productive Types of Compound Nouns

|

Free |

Compound |

||

|

Compounds Proper |

Derivational Compounds |

Pattern |

|

|

Verbal prices prices shake |

1) price-reducing price-reduction hand-shake |

— |

— -ing)] ment)] |

|

Nominal ashes a run woman sword |

1) neck house 5) 6) |

— |

— [n’ + |

|

Verb to away |

a break-down a castaway a runaway |

[(v + |