As the other answers say, the general rule is adjective before noun

(or, more generally, the noun comes after the word describing it1),

so your specific phrases should be “phone number”, “file type”,

and “school bag”.

A “bag school” would be a school that taught something about bags.

It sounds boring to me,

but it might be a job prerequisite for baggage handlers

(e.g., for hotels and airports) or grocery store clerks.

To give a perhaps slightly more mundane example,

a “clown class” would be a course of education in how to be a clown

(I’ve never heard of such a thing, but they probably exist),

whereas a “class clown” is a person who behaves in a clown-like way

while in class (and this is a common idiom).

This is the general (99%) rule.

See Why do some adjectives follow the nouns they modify? for a discussion.

It references the Wikipedia article on Postpositive adjectives,

which says that the adjective-after-noun structure

- is normal in some non-English languages,

- is rarely used in modern English: for example, “attorney general”, “heir apparent”, “professor emeritus”, “proof positive”, “time immemorial”, “Amnesty International” (and other names), “code red”, “devil incarnate”, and “chicken supreme”.

_________

1 As the other answers don’t point out,

your question is interesting because it’s not about adjective+noun phrases;

it’s about two-noun phrases.

But the guidance is the same:

the word for the thing that you’re talking about comes last

(99% of the time). For example, “water faucet” is plumbing,

but “tap water” is the liquid that comes out of it.

This is the third part of the “Rebuilding the spellchecker” series, dedicated to the explanation of how the world’s most popular spellchecker Hunspell works.

Quick recap:

- In the first part, I’ve described what Hunspell is; and why I decided to rewrite it in Python. It is an explanatory rewrite dedicated to uncovering the knowledge behind the Hunspell by “translating” it into a high-level language, with a lot of comments.

- In the second part I’ve covered the basics of the lookup (word correctness check through the dictionary) algorithm, including affix compression.

This part is a carry-over of lookup algorithm explanation, dedicated to word compounding and some less complicated but nonetheless important concerns: word case and word-breaking. To understand this part, reading the previous one is strongly suggested. At very least you should remember that there are stems with flags, specified by .dic-file, with the meaning of flags defined in .aff-file.

Word compounding

Many languages, like German, Dutch, or Norvegian, have word compounding: two stems can be joined together, producing the new word. To check the spelling of the word in the language with compounding, the spellchecker needs to break it into all possible parts, and check if there exists a combination of parts such that all parts would be correct words that are allowed inside compound words.

Hunspell has two independent mechanisms to specify the compounding logic of a language in aff-file: per-stem flags, and regexp-like rules. Sometimes both mechanisms are used in the same dictionary.

Per-stem flag checks

There is a generic COMPOUNDFLAG directive to specify a flag, which, when attached to a stem, means “this stem can be anywhere in a compound” (examples from LibreOffice’s Norvegian dictionary):

# In nb_NO.aff:

...

# Directive defines: any word with "z" flag is allowed to be in a compound

COMPOUNDFLAG z

# In nb_NO.dic:

...

fritt/CEGKVz

...

røyk/AEGKVWz

Both fritt (“free”) and røyk (“smoke”) have z flag, which means they could be in any place in compound word, and thus, “røykfritt” (“smoke-free” = “non-smoking”) is a valid one—and “frittrøyk” too1.

There are also more precise COMPOUNDBEGIN/COMPOUNDMIDDLE/COMPOUNDEND directives, setting the flags for stems which can be only at a certain place in compounds. Flags designated by those directives could be freely mixed: a compound can consist of a part marked with generic COMPOUNDFLAG, and another part marked with COMPOUNDEND.

To check the compound word for correctness, Hunspell needs to chop off the beginning of the word, of every possible length, and check if it is a valid stem which is allowed at the beginning of the compound. If so, the algorithm recursively chops the next parts, till the whole word is split into compound parts (or no suitable parts found).

Note that depending on the word’s length, and on how many dictionary words are allowed to be in compounds, the loop can take quite some time: the process we described in the previous part (affix-based search of the correct form) can be repeated dozens of times for various “part candidates”.

Let

Lookup.compound_by_flagsin Spylls documentation be your guide!

Defining compounds as regexp-like rules

There is another way to specify compounding logic. It is implemented by COMPOUNDRULE directive, with statements like A*B?C (meaning, “correct compound consists of any number of words with the flag A, then one or zero words with the flag B, then a mandatory word with the flag C”). The most common use of it is specifying suffixes in numerals. For example, in the en_US dictionary:

# en_US.aff

COMPOUNDRULE 2 # we have 2 compound rules listed below

COMPOUNDRULE n*1t # rule 1: any number (*) of "n"-marked stems, then "1"-marked stem, then "t"-marked stem

COMPOUNDRULE n*mp # rule 2: any number (*) of "n"-marked stems, then "m"-marked stem, then "p"-marked stem

# en_US.dic

# ...defines numbers as "stems" for this rule:

0/nm

1/n1

2/nm

3/nm

4/nm

5/nm

6/nm

7/nm

8/nm

9/nm

# ...and numerical suffixes as stems, with different flags, too!

0th/pt

1st/p

1th/tc

2nd/p

2th/tc

3rd/p

3th/tc

4th/pt

5th/pt

6th/pt

7th/pt

8th/pt

9th/pt

This leads to Hunspell being able to say that “1201st” is correct (the rule n*mp matched: “1” and “2” with “n” flags, “0” with “m”, and “1st” with “p”), and “1211th” is correct (another rule in action: n*1t), but “1211st” is not.

Handling the word correctness check in a presence of the COMPOUNDRULE requires to again recursively split word into possible parts—but this time already found parts should be checked for a partial match against known rules.

Lookup.compound_by_rules implements this in a complicated, yet concise way.

But wait, there is more!

To make things more complicated To match the complexity of real life, both algorithms of compound words checking need to consider:

- Numeric limitations: some dictionaries might limit the minimum size of a part of the compound, or the maximum number of parts.

- Affixes: By default, any prefix is allowed at the beginning of the compound word, and any suffix is allowed at the end; and yet, some affixes might have flags saying “it should never be in any compound”, and some others might have flags saying “it is allowed in the middle of the compound” (e.g. prefix to non-first or suffix to a non-last part).

- Several rules that, being present in aff-file, reject some compound words with seemingly correct parts as incorrect: for example, if the letter at the boundary of the compound is tripled (

fall+lucka); if some parts of the compound are repeated (dubb+bon+bon); if the non-first part of the compound is capitalized, or “this regexp-like pattern is prohibited at the boundary of the compound parts”, and so on. - Some of those settings might lead to a whole new word checking loop in the middle of compound checking: for example,

CHECKCOMPOUNDREPsetting tells the algorithm: use theREP-table specified in aff-file (typical misspelled sequences of letters, like “f=>ph”, usually used on suggest) to check if some part of the compound, with replacement applied, is the valid word. If yes, then it is an incorrect compound! E.g. “badabum” split into parts “ba”, “da”, “bum”, but then, if we apply the replacement “u=>oo”, turns out “daboom” is a correct non-compound word… Then we should consider “badabum” a misspelling, and the “ba daboom” is most probably what was misspelled.

Are you thrilled? Then follow the

Lookup.compound_formsdocs to uncover even more dirty details.

…and other complications

Affix check and (de)compounding are the main parts of the algorithm, yet there is more! Just a brief overview to give you some taste:

- Words case: “kitten” can be spelled “Kitten” or “KITTEN”, but “Paris” can’t be spelled “paris”

- …but, the word might have a flag defined as

KEEPCASEin aff-file, meaning it should be ONLY in the exact case as in the dictionary; - …and there are complications with the German language: “SS” can be downcased as “ss” or “ß” (“sharp s”), and both should be checked through the dictionary, and also, when the word is uppercased, it is allowed to have “ß”: “STRAßE”;

- …and in Turkic languages casing rules for “i” are different: “i=>İ” and “I=>ı”;

- …and the ending part of the compound might have a flag saying “this compound should be titlecased”: in Swedish dictionary, there are special words like “afrika”, which are allowed only at the end of compounds, and require the whole compound to be in titlecase: “Sydafrika” (South Afrika);

- …but, the word might have a flag defined as

- Word breaking: “foo-bar” should be checked as the whole word, and also as two separate words “foo” and “bar”

- …unless aff-file redefines this, by prohibiting word-breaking, or changing by which patterns words should be broken.

- Some words might be present in the dictionary with a flag defined as

FORBIDDENWORD: it is used to disallow words that are logically possible (allowed stem with allowed suffix), but this specific combination is incorrect in the language. - There might be an

ICONV(“input conversions”) directive defined in aff-file, saying which chars convert before the spellchecking: for example, replacement of several kinds of typographic apostrophes with simple'to simplify the dictionary, or unpacking the ligatures (fi→fi).- But this feature can be used not only for handling fancy typography: for example, the Dutch dictionary uses it for enforcing proper case of “ij”: In Dutch, it is considered a single entity and both letters should always have the same case. It is achieved by

ICONV-ing to ligatures:ij→ijandIJ→IJ(butIjwouldn’t be converted, and wouldn’t be found in a dictionary, as all dictionary words also contain ligatures).

- But this feature can be used not only for handling fancy typography: for example, the Dutch dictionary uses it for enforcing proper case of “ij”: In Dutch, it is considered a single entity and both letters should always have the same case. It is achieved by

- An

IGNOREdirective, defined in aff-file, says which characters to drop before spellchecking (in Arabic and Semitic languages, where vowels may be present but should be ignored).

That’s mostly the size of it!

To go for the full ride, start reading the Spylls docs from the

Lookup.__call__method. You won’t be disappointed!

Lookup: takeout

To reiterate on everything said above: There are good and useful dictionaries for spellchecking of many languages, freely available in Hunspell’s format, and one might be tempted to reuse them in own code. But the process of going from the not-that-complicated input format to a full reliable spellchecking includes at least:

- Reading of aff-files (consisting of multiple directive “types”, with reading logic depending on particular directive) and dic-files (words with flags)—we’ll talk about this interesting task in later installments2;

- Affix analysis: either on-the-fly (how Hunspell and Spylls do), or once: “unpack” the list of stems with flags into words with affixes;

- Compounding analysis—unless you just want to omit the support for languages with compounding (this apparently can’t be solved with a pre-generated list of “all correct compound words”);

- Handling of complications with word breaking, text case, special characters, and whatnot.

Some of those tasks are directly related to how Hunspell is built and could’ve been done differently. But mostly, this chapter tries to show that “check if the word spelled correctly”, especially in languages other than English, should be seen as a not-that-trivial task, to say the least.

And we haven’t even started on corrections suggestion yet, which we’ll gladly do in the next part. Follow me on Twitter or subscribe to my mailing list if you don’t want to miss the follow-up!

PS: Huge thanks to @squadette, my faithful editor. Without his precious help, the text would be even more convoluted!

1)General

features of word-compounding.

2)Structural

and semantic peculiarities of English compounds.

3)Classification

of compounds.

4)The

meaning of compounds.

5)Motivation

of English compounds.

6)Special

groups of compounds.

Word-compounding

is

a way of forming new words combining two or more stems. It’s

important to distinguish between compound words and

word-combinations, because sometimes they look or sound alike. It

happens because compounds originate directly from word-combinations.

The

major feature of compounds is their inseparability

of various kinds: graphic, semantic, phonetic, morphological.

There

is also a syntactic

criterion which helps us to distinguish between words and word

combinations. For example, between the constituent parts of the

word-group other words can be inserted (a

tall handsome

boy).

In

most cases the structural and semantic centre of the compound word

lies on the second component. It shows what part of speech the word

is. The function of the first element is to modify, to determine the

second element. Such compounds (with the structural and semantic

centre “in” the word) are called endocentric.

There

are also exocentric

compounds where the centre lies outside (pickpocket).

Another

type of compound words is called bahuvrihi

– compound nouns or adjectives consisting of two parts: the first

being an adjective, the second – a noun.

There

are several ways to classify compounds. Firstly, they can be grouped

according to their part of speech. Secondly, compounds are grouped

according to the

way the stems are linked together:

morphological compounds (few in number); syntactic compounds (from

segments of speech, preserving articles, prepositions, adverbs).

The

third classification is according to the combinability of compounding

with

other

ways of word-formation:

1) compounds proper (formed by a mere juxtaposition of two stems);

2)

derived or derivational compounds (have affixes in their structure);

3)

converted compounds;

4)

contractive compounds (based on shortening);

5)

compounds based on back formation;

Beside

lexical meanings the components of a compound word have

distributional

and

differential

meanings.

By distributional

meaning

we understand the order, the arrangement of the stems in the word.

The differential

meaning

helps to distinguish two compounds possessing the same element.

The

structural

meaning

of a compound may be described through the interrelation of its

components. e.g. N + Adj (heart-sick

– the relation of cpmparison).

In

most cases compounds are

motivated.

They can be completely motivated, partially motivated, unmotivated.

In partially motivated compounds one of the components (or both) has

changed its original meaning. The meaning of unmotivated compounds

has nothing to do with the meanings of their individual parts.

As

for special groups of compounds, here we distinguish:

a)

reduplicative compounds;

b)

ablaut combinations;

c)

rhyme combinations.

There’s

a certain group of words that stand between compounds and derived.

These are words with so called semi-affixes:

kiss proof

(about

lipstick), fireproof,

foolproof.

Conversion

1)General

problems of conversion in English.

2)Semantic

relations between conversion pairs.

3)

Sources and productivity of conversion.

In

linguistics conversion

is

a type of word-formation; it is a process of creating a new word in a

different part of speech without adding any derivational element. The

morphemic shape of the original word remains unchanged. There are

changes in the syntactical function of the original word, its part of

speech and meaning.

The

question of conversion

has been a controversial one in several aspects. The term conversion

was first used by Henry Sweet at the end of the 19th

century. The nature of conversion has been analyzed by several

linguists. A number of terms have been offered to describe the

process in question.

The

most objective treatment of conversion belongs to Victoria Nikolaevna

Yartseva. According to her, it is a combined morphological,

syntactical and semantic way of word-formation.

The

process was called “non-affixal

derivation”

(Galperin) or “zero

derivation”.

These terms have drawbacks, because there can be other examples of

non-affixal or zero derivation which are not connected with the

process described at the beginning of the lecture.

The

term “functional

change”

(by Arthur Kennedy) also has short-comings. The term implies that the

first word merely changes its function and no new word appears. It

isn’t possible.

The

word conversion

we

use talking about this way of word-formation is not perfect as well.

It means the transformation of something into another thing, the

disappearance of the first word. But the old and the new words exist

together.

The

largest group

related through conversion consists of verbs

converted from nouns.

The relations of the conversion pair in this case can be of the

following kind:

1)

instrumental relations;

2)

relations reflecting some characteristic of the object;

3)

locative relations;

4)

relations of the reverse process, the deprivation of the object.

The

second major division of converted words is deverbial

nouns

(nouns converted from verbs).

They

denote:

1)

an instance of some process;

2)

the object or the result of some action;

3)

the place where the action occurs;

4)

the agent or the instrument of the action.

Conversion

is not only a highly productive but also a particularly English way

of word-building. There are a lot of words in the English language

that are short and morphologically unmarked (don’t indicate any

part of speech). By short words we mean monosyllables, such words are

naturally more mobile and flexible than polysyllables.

In

English verbs and nouns are specially affected by conversion.

Conversion has restrictions. It’s impossible to use conversion if

verbs cannot represent some process as a succession of isolated

actions. Besides, the structure of the first word shouldn’t be

complicated.

Conversion

is typical not only of nouns, verbs and adjectives, but other parts

of speech as well, even such minor elements as interjections and

prepositions or shortened words.

Shortening

1.

General problems of shortening.

2.

Peculiarities of shortenings.

Shortening

stands apart from other ways of word-formation because it doesn’t

produce new words. It produces variants of the same word. The

differences between the new and the original word are in style,

sometimes in their meaning.

There

are two major groups of shortenings (colloquial and written

abbreviations). Among shortenings there can be polysemantic units as

well.

Shortenings

are classified a) according to the position of the shortened part of

the word (clipped words), b) into shortened word combinations, c)

into abbreviations, d) into blendings.

Among

clipped words there are cases of apocope, aphaeresis, and syncope.

Abbreviations can be read as in the alphabet, as one word.

The

Semantic Structure of English Words

1.General

problems of semasiology. The referential and the functional

approaches to the meaning of English words.

2.Types

of meaning.

3.Change

of meaning.

4.Polysemy.

5.Homonymy.

6.Synonyms,

antonyms and other semantic groupings.

The

branch of linguistic which specializes in the study of meaning is

called semantics or semasiology. The modern approach to semantics is

based on the fact that any word has its inner form which is called

the semantic structure.

There

are two main approaches to the meaning of a word: referential and

functional.

The

referential approach is based on the notion of the referent (the

object the word is devoted to). It also operates the notions of the

concept and word. The word and the referent are related only through

the concept. The drawback of the approach is in the fact that it

deals with psychology mostly.

According

to the functional approach the meaning of a word depends on the

function of the word in a sentence. The approach is not perfect

because it can help us only to compare the meanings of words.

Speaking about the meaning of a word both approaches should be

combined.

The

meaning of a word can be divided into grammatical

and

lexical.

The latter is divided into denotational

and

connotational

meanings. The denotational meaning gives the general idea which is

characteristic of a certain word. The connotational meaning combines

the emotive colour and the stylistic value of a word.

The

smallest elements of meaning are called semes.

There

are words with either only the denotational or the connotational

meaning.

Causes

of semantic changes can be extra

linguistic and

linguistic.

Extra linguistic causes are historical in their nature. Among

linguistic causes we distinguish discrimination of synonyms,

ellipsis, linguistic analogy.

As

for the nature of semantic changes, it is connected with some sort of

association between the old and the new meanings. These associations

can be of two types: of similarity (linguistic metaphor), of

contiguity (linguistic metonymy).

The

result of semantic changes can be seen in denotational and

connotational meanings. The denotational meaning can be generalized

or specialized. The connotational meaning can be worsened or

elevated.

Most

words are polysemantic. Monosemantic words are usually found among

terms and scientific words. The ability of words to have more than

one meaning is called polysemy.

Polysemy exists only in the language system.

The

semantic structure of a polysemantic word may be described as a

combination of its semantic variants. Each variant can be described

from the point of view of their denotational and connotational

meaning.

Polysemy

is closely connected with the notion of the context

(the minimum stretch of speech which is sufficient to understand the

meaning of a word). The main types of context are lexical and

grammatical.

Homonyms

are words identical in sound and spelling or at least in one of these

aspects, but different in their meaning. According to Profesor

Smirnitsky homonyms can be divided into two groups: full homonyms

(represent the same part of speech and have the same paradigm),

partial homonyms (don’t coincide either in their spelling or

paradigm).

Another

classification of homonyms deals with homophones

and homographs.

The

sources of homonyms are phonetic changes, borrowing, word-building

(especially conversion), shortening.

There

are several classifications of various word groups. The semantic

similarity and polarity are connected with synonyms and antonyms.

Synonyms

are words different in sound-form but similar in meaning. According

to Vinogradov synonyms can be divided ideographic, stylistic and

absolute. A dominant

synonym

(in any row of synonyms) is more frequent in communication and

contains the major denotational component of the synonyms in

question.

Antonyms

are words belonging to the same part of speech with some opposite

meaning.

As

for other groups of words, there are hyponyms, hyperonyms, semantic

fields, thematic groups.

The

development of the English vocabulary

1.The

development of the vocabulary. Structural and semantic peculiarities

of new vocabulary

units.

2.Ways

of enriching the vocabulary.

If

the language is not dead, it’s developing all the time. The items

that disappear are called archaisms.

They can be found among numerous lexical units and grammatical forms.

New

words or expressions, new meanings of older words are called

neologisms.

The introduction of new words reflects developments and innovations

in the world at large and in society.

Apart

from political terms, neologisms come from the financial world,

computing, pop scene, drug dealing, crime life, youth culture,

education.

Neologisms

come into the language through

1)productive

ways of word formation;

2)ways

without any pattern;

3)semantic

changes of old words;

4)borrowing

from other languages.

There

are numerous cases of blending, compounding, conversion. Borrowed

words mostly come from French, Japanese, the American variant of the

English language.

Соседние файлы в предмете [НЕСОРТИРОВАННОЕ]

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

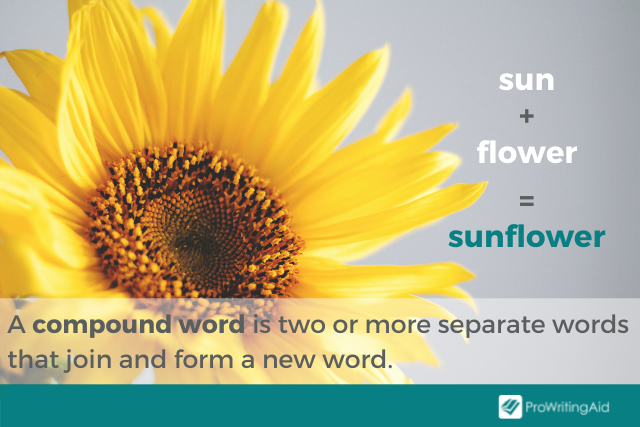

The words pancake, living room, and merry-go-round have something in common.

They are all examples of compound words.

The noun compound means something made up of two or more separate components. Compound can also be an adjective meaning consisting of two or more parts or components.

A compound word is one word, or one unit of meaning, that is created by joining two or more separate words together.

What Are Compound Words?

A compound word is a word made up of usually two but sometimes more words that are joined together. The two (or more) that make the compound word are independent words; they have their own distinct meanings. When those words are joined and form a compound word, that compound word has its own new meaning.

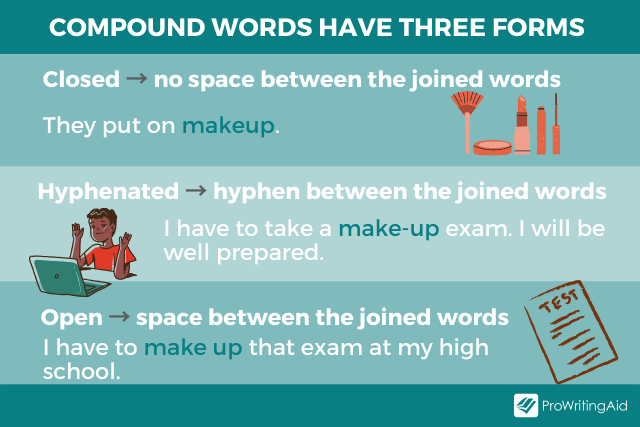

The Three Types of Compound Words

Compound words can take three possible forms: closed, open, or hyphenated. In closed form, there is no space between the joined words. In open form, there is a space between the “joined” words that still act as one unit, and in hyphenated form—you guessed it! There is a hyphen between the joined words.

These general “rules”—which are somewhat fluid and flexible—provide guidance as to what format a compound word takes.

-

Closed compound words are usually nouns: They put on makeup.

-

Open compound words are usually nouns or verbs: I have to make up (verb) that exam at my high school. (noun)

-

Hyphenated compound words are usually adjectives or adverb-adjective combinations: I have to take a make-up (adjective) exam. I will be well-prepared. (adverb + adjective)

The key word in each of those examples is “usually.” Some compound words break the rules. We’ll see how soon.

1. Closed Compound Words

To review: closed compound words are usually made up of two separate words that are put together to form a new word. There is no space between the two words in a closed-form compound word; the compound appears as one single word.

Examples of Closed Compound Words

-

Cup + cake becomes cupcake

-

Basket + ball becomes basketball

-

Key + board becomes keyboard

-

Extra + ordinary becomes extraordinary

-

Birth + day becomes birthday

You can see through these examples that the meaning of the compound word is not just a merger of the independent definitions of the individual words that join together to make that compound.

However, there is a relationship between the individual word meanings and the compounds. Compound words have been integrated into language as speakers have discovered those relationships. It makes perfect sense to call a cake that could fit into a cup a cupcake and to call a ball thrown through a basket (now a hoop) a basketball.

The rules for compound words, listed earlier in the post, include the word usually. That word means the rules are not hard and fast, and there are examples of compound words that break those rules.

For example, compound words that are verbs are usually open form, but here are rule-breaking closed-form compound verbs that remind us to hold those rules loosely:

-

I need to proofread my essay.

-

I think the clerk shortchanged me.

-

I have to babysit my little sister.

2. Open Compound Words

In an open compound word, there is a space between the two independent words, though they are still treated as one unit with a new “compound meaning.”

Examples of Open Compound Words

-

Living room: as a unit, this compound noun refers to a room in a house.

-

High school: as a unit, this compound noun refers to a school that has students in grades 9-12.

-

Post office: as a unit, this compound refers to a building where mail is collected, sorted, and sent.

-

Give up: as a unit, this compound verb means to stop trying.

-

Ask for: as a unit, this compound verb means to request something.

3. Hyphenated Compound Words

Hyphenated compound words have hyphens between each of the independent words that serve as connectors. The hyphens are a visual cue that the words form one unit.

Some compound words are always hyphenated.

-

Merry-go-round

-

Mother-in-law (and brother-, sister-, and father-in-law)

-

Self-esteem

Did you notice that all of those examples are nouns? Remember: the rules are flexible!

Examples of Hyphenated Compound Adjectives:

When compound words are used as adjectives (officially known as compound adjectives), the hyphenation rules change depending on where the compound adjective comes in the sentences.

If the compound adjective comes before the noun it modifies (describes), you should usually add a hyphen:

-

High-speed chase

-

Part-time employee

-

Full-time job

-

Fire-resistant pajamas

-

Good-looking person

-

Well-respected politician

-

Up-to-date records

Of course, there are exceptions. Remember, those “rules” are flexible. Some compound adjectives that precede the nouns they modify never take a hyphen. For example, ice cream and high school:

- High school students

- Ice cream sundae

There’s really no “why” to explain these exceptions; we’ve just adopted these forms and made them part of our language.

Examples of Open-Form Compound Adjectives

If the compound adjective comes after the noun it modifies, the hyphen is usually omitted.

-

Make sure the files are up to date. “Up to date” modifies, but comes after, the noun “files.”

-

The cat is two years old. “Two years old” modifies, but comes after, the noun “cat.”

Though post-noun modifiers don’t technically take hyphens, according to Merriam-Webster, usage trends indicate the hyphens are often included anyway, if the compounds “continue to function as unit modifiers.” So there’s that flexibility again.

What About Adverb Compounds?

It’s easy to find examples of closed, open, and hyphenated adverbs.

As for the closed-form examples, we probably don’t even register them as compound words much of the time.

-

Sometimes

-

Thereafter

-

Somewhere

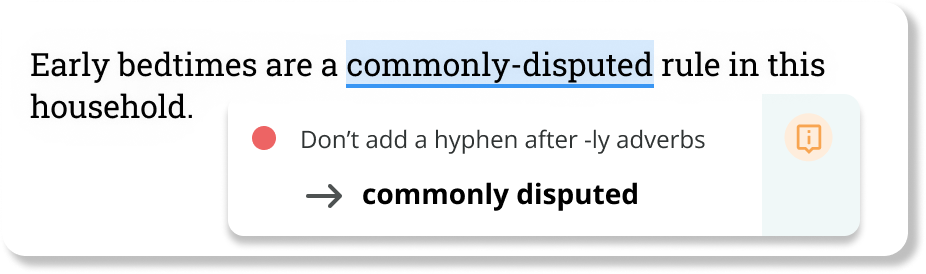

Open-form adverbs occur when the adverb is the first word in the compound and ends in —ly. You should not hyphenate after an —ly adverb.

-

We made the discovery early on.

-

Her opinion is highly regarded.

-

They entered the dimly lit room.

What to Do If You’re Not Sure Which Form Is Right

While those flexible rules can help you, there may still be times when you feel confused about which compound form to use. Don’t stress too much.

According to Merriam Webster, the rules are more like patterns. You may see differences in different publications depending on editorial choice and style. For example, I looked on Amazon for a teapot. I saw mostly teapots, but also a few tea pots. Out of curiosity I put “tea pot” into a New York Times search bar, and found articles from the 1800s that included “tea-pot” in the title!

While interesting, those stylistic changes and choices shouldn’t be too surprising. Language is fluid and ever-evolving. Compound words themselves are proof of that evolution.

Keep Clarity the Focus

The purpose of hyphens in compound words is to ensure clarity. For example,

-

I bought over-the-counter medication.

-

He passed the medicine over the counter.

In the first example, I know by the hyphen that the medicine «I» bought did not require a prescription. «Over-the-counter» is one unit—one compound—describing a type of medicine.

In the second example, «over the counter» is serving another purpose and, while the words form a phrase to tell me where «he» passed the medicine, hyphens do nothing to make the purpose of the phrase clear and are therefore unnecessary.

Now look at these examples:

- He owned a little-used car.

- He owned a little used car.

In the first example, I know the man owns a car that has not been driven much. The car is described by the compound modifier «little-used.»

In the second example, it seems that the man owns a used car that is also small, or little. In this example, putting a comma after «little» would help to separate the two words, «little» and «used,» and show that they aren’t intended to work as a compound.

ProWritingAid Can Help

Though you’re a compound-word expert now, if you find yourself with lingering doubts, remember that ProWritingAid is here to help. It will let you know if you’ve added an unnecessary hyphen after an -ly adverb, or if you’ve left one out of a pre-noun compound adjective. You don’t have to write alone!