Asked by: Ms. Esther Lang I

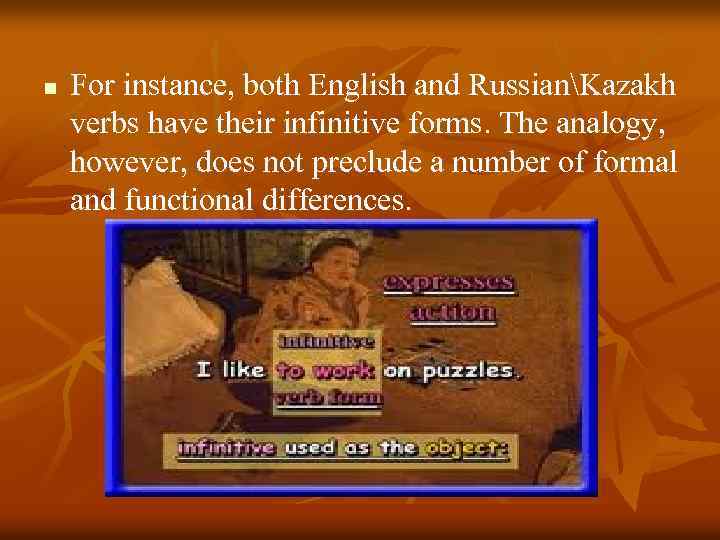

Score: 4.3/5

(50 votes)

Don’t worry, commonest is the word and many dictionaries define it. commonest (adj) — Occurring, found, or done often; prevalent. However, if you find it on Ngram, most common is more popular than commonest especially in recent years.

Is it correct to say commonest?

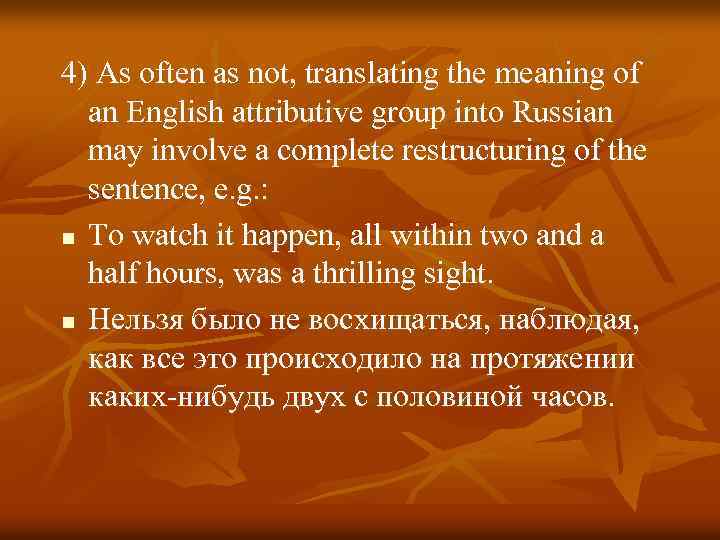

The comparative and superlative forms of common are usually more common and most common. Commonest is sometimes used instead of most common in front of a noun.

Do we say most common or commonest?

According to Swan (my grammar bible), common can equally be used with -er and -est as well as more and most. And it’s most common to say ‘most common’ (3,150,000). ‘Commonest’ only has 101,000. Comparatives and superlatives for words of three or more syllables invariably use more and most.

Is commonest a word UK?

Indeed, the word commonest has led a fairly different life in British English. … survey was published in 1970 by Oxford University Press, close to the height of this word’s usage in British English. It makes sense, then, that it was used in the same way that I would use most common.

What is the superlative for the word common?

Adjective. common (comparative commoner or more common, superlative commonest or most common)

33 related questions found

What part of speech is commonest?

adjective, com·mon·er, com·mon·est. widespread; general; universal: common knowledge.

What type of word is common?

adjective, com·mon·er, com·mon·est. belonging equally to, or shared alike by, two or more or all in question: common property;common interests. pertaining or belonging equally to an entire community, nation, or culture; public: a common language or history;a common water-supply system.

How do you use commonest in a sentence?

Common sentence example

- She will only utilize it for common good. …

- We have a lot in common , you know? …

- The only thing they had in common was looks! …

- I mean, we grew up together, so we have a lot in common , but… …

- Carmen took her to the doctor, but he said there was no cure for the common cold and not to worry about it.

Is OK an English word?

OK (spelling variations include okay, O.K., ok and Ok) is an English word (originally American English) denoting approval, acceptance, agreement, assent, acknowledgment, or a sign of indifference. OK is frequently used as a loanword in other languages. … The origins of the word are disputed.

What is the most unused word?

The 15 most unusual words you’ll ever find in English

- Serendipity. This word appears in numerous lists of untranslatable words and is a mystery mostly for non native speakers of English. …

- Gobbledygook. …

- Scrumptious. …

- Agastopia. …

- Halfpace. …

- Impignorate. …

- Jentacular. …

- Nudiustertian.

What is the least common word?

1.abate: reduce or lesson. 2.abdicate: give up a position. 3.aberration: something unusual, different from the norm. 4.abhor: to really hate.

What is an example of common?

The definition of common is something that belongs to or is shared by two or more people or the community at large. An example of common is the knowledge of drivers to stop at a red light.

What are common nouns?

A common noun is the generic name for a person, place, or thing in a class or group. Unlike proper nouns, a common noun is not capitalized unless it either begins a sentence or appears in a title. … Usually, it will be quite obvious if a specific person, place, or thing is being named.

What are common nouns examples?

A common noun is a non-specific person, place, or thing. For example, dog, girl, and country are examples of common nouns. In contrast, proper nouns name a specific person, place, or thing. Common nouns are typically not capitalized, but there are two exceptions to this rule.

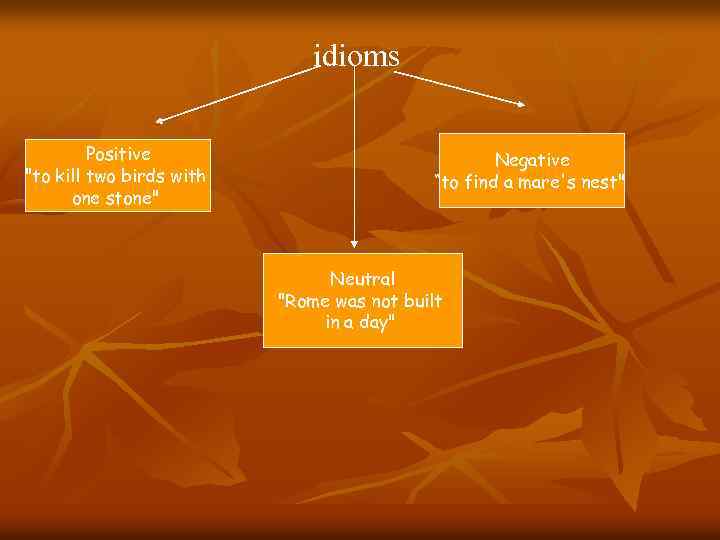

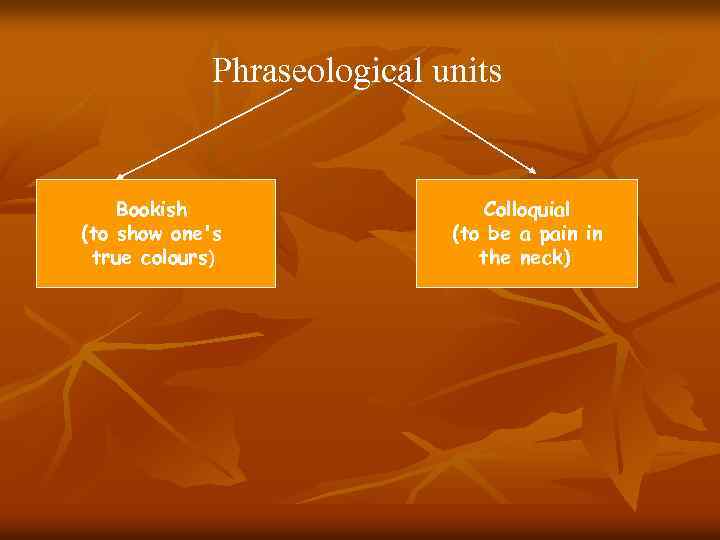

What is a common term?

Noun. Language regarded as very informal and restricted to a particular context or group of people. vulgarism. idiom. colloquialism.

What does commen mean?

Definition of «commen» [commen]

An old form of common.

Does common Mean same?

As adjectives the difference between common and same

is that common is mutual; shared by more than one while same is not different or other; not another or others; not different as regards self; selfsame; identical.

What type of speech is the word common?

common adjective (SHARED)

What’s the synonym for Boston?

In this page you can discover 24 synonyms, antonyms, idiomatic expressions, and related words for boston, like: capital of Massachusetts, the Hub, Hub of the Universe, beantown, Athens of America, home of the bean and the cod, cradle of liberty, Bean Town, chicago, philadelphia and baltimore.

What word has all 26 letters in it?

An English pangram is a sentence that contains all 26 letters of the English alphabet. The most well known English pangram is probably “The quick brown fox jumps over the lazy dog”. My favorite pangram is “Amazingly few discotheques provide jukeboxes.”

What word takes 3 hours to say?

The chemical name of titin was first kept in the English dictionary, but it was later removed from the dictionary when the name caused trouble. It is now known only as Titin. Titin protein was discovered in 1954 by Reiji Natori.

common

(redirected from commonest)

Also found in: Thesaurus, Legal, Idioms, Encyclopedia.

com·mon

(kŏm′ən)

adj. com·mon·er, com·mon·est

1.

a. Belonging equally to or shared equally by two or more; joint: common interests.

b. Of or relating to the community as a whole; public: for the common good.

2. Widespread; prevalent: Gas stations became common as the use of cars grew.

3.

a. Occurring frequently or habitually; usual: It is common for movies to last 90 minutes or more.

b. Most widely known; ordinary: the common housefly.

4. Having no special designation, status, or rank: a common sailor.

5.

a. Not distinguished by superior or noteworthy characteristics; average: the common spectator.

b. Of no special quality; standard: common procedure.

c. Of mediocre or inferior quality; second-rate: common cloth.

6. Unrefined or coarse in manner; vulgar: behavior that branded him as common.

7. Grammar

a. Either masculine or feminine in gender.

b. Representing one or all of the members of a class; not designating a unique entity.

n.

1. commons The common people; commonalty.

2. commons(used with a sing. or pl. verb)

a. The social class composed of commoners.

b. The parliamentary representatives of this class.

3. Commons The House of Commons.

4. A tract of land, usually in a centrally located spot, belonging to or used by a community as a whole: a band concert on the village common.

5. The legal right of a person to use the lands or waters of another, as for fishing.

6. commons(used with a sing. verb) A building or hall for dining, typically at a university or college.

7. Common stock.

8. Ecclesiastical A service used for a particular class of festivals.

Idiom:

in common

Equally with or by all.

[Middle English commune, from Old French commun, from Latin commūnis; see mei- in Indo-European roots.]

com′mon·ly adv.

com′mon·ness n.

Synonyms: common, ordinary, familiar

These adjectives describe what is generally known or frequently encountered. Common applies to what takes place often, is widely used, or is well known: The botanist studied the common dandelion. The term also implies coarseness or a lack of distinction: My wallet was stolen by a common thief. Ordinary describes something usual that is indistinguishable from others, sometimes derogatorily: «His neighbors were all climbing into their cars and trucks and heading off to work as if nothing miraculous had happened and this were just another ordinary day» (Steve Yarbrough).

Familiar applies to what is well known or quickly recognized: Most children can recite familiar nursery rhymes. See Also Synonyms at general.

American Heritage® Dictionary of the English Language, Fifth Edition. Copyright © 2016 by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company. Published by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company. All rights reserved.

common

(ˈkɒmən)

adj

1. belonging to or shared by two or more people: common property.

2. belonging to or shared by members of one or more nations or communities; public: a common culture.

3. of ordinary standard; average: common decency.

4. prevailing; widespread: common opinion.

5. widely known or frequently encountered; ordinary: a common brand of soap.

6. widely known and notorious: a common nuisance.

7. derogatory considered by the speaker to be low-class, vulgar, or coarse: a common accent.

8. (prenominal) having no special distinction, rank, or status: the common man.

9. (Mathematics) maths

a. having a specified relationship with a group of numbers or quantities: common denominator.

b. (of a tangent) tangential to two or more circles

10. (Phonetics & Phonology) prosody (of a syllable) able to be long or short, or (in nonquantitative verse) stressed or unstressed

11. (Grammar) grammar (in certain languages) denoting or belonging to a gender of nouns, esp one that includes both masculine and feminine referents: Latin sacerdos is common.

12. (Anatomy) anatomy

a. having branches: the common carotid artery.

b. serving more than one function: the common bile duct.

13. (Ecclesiastical Terms) Christianity of or relating to the common of the Mass or divine office

14. common or garden informal ordinary; unexceptional

n

15. (Physical Geography) (sometimes plural) a tract of open public land, esp one now used as a recreation area

16. (Law) law the right to go onto someone else’s property and remove natural products, as by pasturing cattle or fishing (esp in the phrase right of common)

17. (Ecclesiastical Terms) Christianity

a. a form of the proper of the Mass used on festivals that have no special proper of their own

b. the ordinary of the Mass

18. archaic the ordinary people; the public, esp those undistinguished by rank or title

19. in common mutually held or used with another or others

[C13: from Old French commun, from Latin commūnis general, universal]

ˈcommonness n

Collins English Dictionary – Complete and Unabridged, 12th Edition 2014 © HarperCollins Publishers 1991, 1994, 1998, 2000, 2003, 2006, 2007, 2009, 2011, 2014

com•mon

(ˈkɒm ən)

adj. -er, -est,

n. adj.

1. belonging equally to, or shared alike by, two or more or all in question: common objectives.

2. pertaining or belonging equally to an entire community, nation, or culture: a common language.

3. joint; united: a common defense.

4. widespread; general; universal: common knowledge.

5. of frequent occurrence; usual; familiar: a common mistake.

6. of mediocre or inferior quality; mean: a rough, common fabric.

7. coarse; vulgar: common manners.

8. lacking rank, station, distinction, etc.; ordinary: a common soldier.

9. in keeping with accepted standards; fundamental: common decency.

10. (of a syllable) able to be considered as either long or short.

11.

a. (of a grammatical case) fulfilling different functions that in some languages would require different inflected forms: English nouns used as subject or object are in the common case.

b. of or pertaining to a word or gender that may refer to either a male or female: Frenchélève “pupil” has common gender.

c. constituting a gender comprising nouns that were formerly masculine or feminine: Dutch nouns are either common or neuter in gender.

12. bearing a similar mathematical relation to two or more entities.

13. of or pertaining to common stock.

n.

14. Often, commons. a tract of land owned or used jointly by the residents of a community, as a central square or park in a city or town.

15. the right, in common with other persons, to pasture animals on another’s land or to fish in another’s waters.

16. commons,

a. the common people; commonalty.

b. the body of people not of noble birth, as represented by the House of Commons.

c. (cap.) (used with a sing. v.) the House of Commons.

17. commons,

a. (used with a sing. v.) a large dining room, esp. at a university or college.

b. (usu. with a pl. v.) food or provisions for any group.

18. (sometimes cap.)

a. an ecclesiastical office or form of service used on a festival of a particular kind.

b. the ordinary of the Mass, esp. those parts sung by the choir.

Idioms:

in common, in joint possession or use; shared equally.

[1250–1300; Middle English comun < Anglo-French, Old French < Latin commūnis common <com- + mūnus task, duty, gift, c. mean2]

com′mon•ly, adv.

com′mon•ness, n.

syn: common, ordinary, vulgar refer, often with derogatory connotations, to what is usual or most often experienced. common applies to what is widespread or unexceptional; it often suggests inferiority or coarseness: common servants; common cloth. ordinary refers to what is to be expected in the usual order of things; it suggests being average or below average: a high price for something of such ordinary quality. vulgar means belonging to the people or characteristic of common people; it suggests low taste, coarseness, or ill breeding: vulgar manners; vulgar speech. See also general.

Random House Kernerman Webster’s College Dictionary, © 2010 K Dictionaries Ltd. Copyright 2005, 1997, 1991 by Random House, Inc. All rights reserved.

common

If something is common, it is found in large numbers or it happens often.

His name was Hansen, a common name in Norway.

These days, it is common to see adults returning to study.

The comparative and superlative forms of common are usually more common and most common. Commonest is sometimes used instead of more common in front of a noun.

Job sharing has become more common.

The disease is most common in adults over 40.

Stress is one of the commonest causes of insomnia.

Be Careful!

Don’t use a that-clause after common. Don’t say, for example, ‘It is quite common that motorists fall asleep while driving‘. You say ‘It is quite common for motorists to fall asleep while driving’.

It is common for a child to become deaf after even a moderate ear infection.

Collins COBUILD English Usage © HarperCollins Publishers 1992, 2004, 2011, 2012

ThesaurusAntonymsRelated WordsSynonymsLegend:

| Noun | 1. | common — a piece of open land for recreational use in an urban area; «they went for a walk in the park»

commons, green, park amusement park, funfair, pleasure ground — a commercially operated park with stalls and shows for amusement parcel of land, piece of ground, piece of land, tract, parcel — an extended area of land populated area, urban area — a geographical area constituting a city or town village green — a village park consisting of a plot of grassy land |

| Adj. | 1. | common — belonging to or participated in by a community as a whole; public; «for the common good»; «common lands are set aside for use by all members of a community»

joint — united or combined; «a joint session of Congress»; «joint owners» individual, single — being or characteristic of a single thing or person; «individual drops of rain»; «please mark the individual pages»; «they went their individual ways» |

| 2. | common — having no special distinction or quality; widely known or commonly encountered; average or ordinary or usual; «the common man»; «a common sailor»; «the common cold»; «a common nuisance»; «followed common procedure»; «it is common knowledge that she lives alone»; «the common housefly»; «a common brand of soap»

usual — occurring or encountered or experienced or observed frequently or in accordance with regular practice or procedure; «grew the usual vegetables»; «the usual summer heat»; «came at the usual time»; «the child’s usual bedtime» ordinary — not exceptional in any way especially in quality or ability or size or degree; «ordinary everyday objects»; «ordinary decency»; «an ordinary day»; «an ordinary wine» uncommon — not common or ordinarily encountered; unusually great in amount or remarkable in character or kind; «uncommon birds»; «frost and floods are uncommon during these months»; «doing an uncommon amount of business»; «an uncommon liking for money»; «he owed his greatest debt to his mother’s uncommon character and ability» |

|

| 3. | common — common to or shared by two or more parties; «a common friend»; «the mutual interests of management and labor»

mutual shared — have in common; held or experienced in common; «two shared valence electrons forming a bond between adjacent nuclei»; «a shared interest in philately» |

|

| 4. | common — commonly encountered; «a common (or familiar) complaint»; «the usual greeting»

usual familiar — within normal everyday experience; common and ordinary; not strange; «familiar ordinary objects found in every home»; «a familiar everyday scene»; «a familiar excuse»; «a day like any other filled with familiar duties and experiences» |

|

| 5. | common — being or characteristic of or appropriate to everyday language; «common parlance»; «a vernacular term»; «vernacular speakers»; «the vulgar tongue of the masses»; «the technical and vulgar names for an animal species»

vernacular, vulgar informal — used of spoken and written language |

|

| 6. |  common — of or associated with the great masses of people; «the common people in those days suffered greatly»; «behavior that branded him as common»; «his square plebeian nose»; «a vulgar and objectionable person»; «the unwashed masses» common — of or associated with the great masses of people; «the common people in those days suffered greatly»; «behavior that branded him as common»; «his square plebeian nose»; «a vulgar and objectionable person»; «the unwashed masses»

plebeian, unwashed, vulgar lowborn — of humble birth or origins; «a topsy-turvy society of lowborn rich and blue-blooded poor» |

|

| 7. | common — of low or inferior quality or value; «of what coarse metal ye are molded»- Shakespeare; «produced…the common cloths used by the poorer population»

coarse inferior — of low or inferior quality |

|

| 8. |  common — lacking refinement or cultivation or taste; «he had coarse manners but a first-rate mind»; «behavior that branded him as common»; «an untutored and uncouth human being»; «an uncouth soldier—a real tough guy»; «appealing to the vulgar taste for violence»; «the vulgar display of the newly rich» common — lacking refinement or cultivation or taste; «he had coarse manners but a first-rate mind»; «behavior that branded him as common»; «an untutored and uncouth human being»; «an uncouth soldier—a real tough guy»; «appealing to the vulgar taste for violence»; «the vulgar display of the newly rich»

rough-cut, uncouth, vulgar, coarse unrefined — (used of persons and their behavior) not refined; uncouth; «how can a refined girl be drawn to such an unrefined man?» |

|

| 9. | common — to be expected; standard; «common decency»

ordinary — not exceptional in any way especially in quality or ability or size or degree; «ordinary everyday objects»; «ordinary decency»; «an ordinary day»; «an ordinary wine» |

Based on WordNet 3.0, Farlex clipart collection. © 2003-2012 Princeton University, Farlex Inc.

common

adjective

1. usual, standard, daily, regular, ordinary, familiar, plain, conventional, routine, frequent, everyday, customary, commonplace, vanilla (slang), habitual, run-of-the-mill, humdrum, stock, workaday, bog-standard (Brit. & Irish slang), a dime a dozen Earthquakes are fairly common in this part of the world.

usual strange, rare, unusual, outstanding, unknown, abnormal, scarce, uncommon, infrequent

5. vulgar, low, inferior, coarse, plebeian She might be a little common at times, but she was certainly not boring.

vulgar cultured, sensitive, distinguished, gentle, sophisticated, noble, refined

Collins Thesaurus of the English Language – Complete and Unabridged 2nd Edition. 2002 © HarperCollins Publishers 1995, 2002

common

adjective

1. Belonging to, shared by, or applicable to all alike:

2. Belonging or relating to the whole:

3. Occurring quite often:

5. Lacking high station or birth:

6. Being of no special quality or type:

average, commonplace, cut-and-dried, formulaic, garden, garden-variety, indifferent, mediocre, ordinary, plain, routine, run-of-the-mill, standard, stock, undistinguished, unexceptional, unremarkable.

7. Of moderately good quality but less than excellent:

acceptable, adequate, all right, average, decent, fair, fairish, goodish, moderate, passable, respectable, satisfactory, sufficient, tolerable.

8. Of low or lower quality:

9. Known widely and unfavorably:

noun

1. The common people.Used in plural:

commonality, commonalty, commoner (used in plural), crowd, hoi polloi, mass (used in plural), mob, pleb (used in plural), plebeian (used in plural), populace, public, ruck, third estate.

2. A tract of cultivated land belonging to and used by a community:

The American Heritage® Roget’s Thesaurus. Copyright © 2013, 2014 by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company. Published by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company. All rights reserved.

Translations

أرْض عامَّه ، أرْض مَشاعإسْم عامخَشِن، فَظ، لِعامّة النّاسشَائِعشائِع

обикновенобщ

comúcomuna

běžnýspolečnýobyčejnýprostýsprostý

fællesfællesarealfælleskønfællesnavnjævn

yleinentavallinenyhteinen

čest

közlegelõköznévordenáré

algenguralmennings-almenninguróbreyttur; alòÿîanruddalegur, ókurteis

普通の

흔한

banalusbe¹drabendrasis kambarysbendrinisBendroji rinka

izplatītskopējskopīgslaukums sabiedriskiem pasākumiemparasts

obecný pozemok

običajenpogostprostaškiskupen

vanligallmängemensam

ที่เกิดขึ้นทุกวัน

phổ biếnthông thườngthườngbình thườngchung

common

[ˈkɒmən]

B. N

2. (Brit) (Pol) the Commons → (la Cámera de) los Comunes

see also House A3

Collins Spanish Dictionary — Complete and Unabridged 8th Edition 2005 © William Collins Sons & Co. Ltd. 1971, 1988 © HarperCollins Publishers 1992, 1993, 1996, 1997, 2000, 2003, 2005

common

[ˈkɒmən]

adj

(in common) [cause] → commun(e)

it’s common knowledge that … → il est bien connu que …, il est bien notoire que …

for the common good → pour le bien de tous, dans l’intérêt général

Collins English/French Electronic Resource. © HarperCollins Publishers 2005

common

adj (+er)

(= frequently seen or heard etc) → häufig; word also → weitverbreitet, weit verbreitet, geläufig; experience also → allgemein; animal, bird → häufig pred, → häufig anzutreffend attr; belief, custom, animal, bird → (weit)verbreitet, weit verbreitet; (= customary, usual) → normal; it’s quite a common sight → das sieht man ziemlich häufig; it’s common for visitors to feel ill here → Besucher fühlen sich hier häufig krank; nowadays it’s quite common for the man to do the housework → es ist heutzutage ganz normal, dass der Mann die Hausarbeit macht

n

(= land) → Anger m, → Gemeindewiese f

nothing out of the common → nichts Besonderes

to have something in common (with somebody/something) → etw (mit jdm/etw) gemein haben; to have a lot/nothing in common → viel/nichts miteinander gemein haben, viele/keine Gemeinsamkeiten haben; we do at least have that in common → wenigstens das haben wir gemein; in common with many other people/towns/countries → (ebenso or genauso) wie viele andere (Leute)/Städte/Länder …; I, in common with … → ich, ebenso wie …

common

:

Common Entrance (Examination)

common

:

common

:

common

:

common

:

common stock

n (US St Ex) → Stammaktien pl

Collins German Dictionary – Complete and Unabridged 7th Edition 2005. © William Collins Sons & Co. Ltd. 1980 © HarperCollins Publishers 1991, 1997, 1999, 2004, 2005, 2007

common

[ˈkɒmən]

1. adj

b. (pej) (vulgar) → volgare, grossolano/a

2. n

b. we have a lot in common → abbiamo molto in comune

Collins Italian Dictionary 1st Edition © HarperCollins Publishers 1995

common

(ˈkomən) adjective

1. seen or happening often; quite normal or usual. a common occurrence; These birds are not so common nowadays.

2. belonging equally to, or shared by, more than one. This knowledge is common to all of us; We share a common language.

3. publicly owned. common property.

4. coarse or impolite. She uses some very common expressions.

5. of ordinary, not high, social rank. the common people.

6. of a noun, not beginning with a capital letter (except at the beginning of a sentence). The house is empty.

noun

(a piece of) public land for everyone to use, with few or no buildings. the village common.

ˈcommoner noun

a person who is not of high rank. The royal princess married a commoner.

common knowledge

something known to everyone or to most people. Surely you know that already – it’s common knowledge.

common ˈlaw noun

a system of unwritten laws based on old customs and on judges’ earlier decisions.

ˈcommon-law adjective

referring to a relationship between two people who are not officially married, but have the same rights as husband and wife. a common-law marriage; a common-law wife/husband.

ˈcommonplace adjective

very ordinary and uninteresting. commonplace remarks.

ˈcommon-room noun

in a college, school etc a sitting-room for the use of a group.

common sense

practical good sense. If he has any common sense he’ll change jobs.

the Common Market

(formerly) an association of certain European countries to establish free trade (without duty, tariffs etc) among them, now replaced by the European Union.

the (House of) Commons

the lower house of the British parliament.

in common

(of interests, attitudes, characteristics etc) shared or alike. They have nothing in common – I don’t know why they’re getting married.

Kernerman English Multilingual Dictionary © 2006-2013 K Dictionaries Ltd.

common

→ شَائِع běžný fælles weitverbreitet συνήθης común yleinen commun čest comune 普通の 흔한 veelvoorkomend vanlig wspólny comum общий vanlig ที่เกิดขึ้นทุกวัน yaygın phổ biến 常见的

Multilingual Translator © HarperCollins Publishers 2009

common

a. común, corriente;

___ name → nombre ___;

___ place → lugar ___;

___ sense → sentido ___.

English-Spanish Medical Dictionary © Farlex 2012

common

adj común; a common problem..un problema común; — sense sentido común

English-Spanish/Spanish-English Medical Dictionary Copyright © 2006 by The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. All rights reserved.

There are two systems for the forms of comparisons of adjectives:

One-syllable adjectives such as long have long, longer, longest.

Adjectives with three and more syllables such as curious have curious, more curious, most curious.

For two-syllable adjectives there is no simple and rigid rule.

Grammarians have listed some endings where system 1 is to be used.

But, I think, people don’t have this list of endings in mind.

Though grammars say it is common, commoner, commonest

people prefer common, more common, most common.

I don’t think that the word communist has an influence in this matter. With «communist» you use different structures.

Either you say: He is a communist — or you say: the communist system.

I think people prefer «more common, most common» because it is easier to speak. Say three times «commoner, commonest»

then you probably feel that hasn’t the right «flow», somehow the two syllables with a weak vowel at the end are against the flow of

speaking.

-

#1

Hi,

pls would you say

«the most common mistake of all» or «the commonest mistake of all»?

Is one of the possibilities comletely incorrect?

Thank you

-

#2

*completely

I have never heard «commonest», «most common» is used more.

-

#3

The most common..is correct

Rocstar

-

#4

Hi,

pls would you say«the most common mistake of all» or «the commonest mistake of all»?

Is one of the possibilities comletely incorrect?

Thank you

I think that they’re both correct although I absolutely LOATHE «commonest» and would never use it.

-

#6

Well, «commonest» is listed HERE, so I assume that both are correct.

EDIT: 2,710,000 matches on google for «commonest»

-

#7

I think it depends on your meaning.

If common = plentiful (the opposite of rare), then without doubt, most common is preferable.

However, sometimes, common is used to mean «uncultured, dirty, lower-class». It’s maybe not very polite, but some people do use it. In this case, it is useful to use commonest, to make it clear that you are not talking about the frequency of occurrence.

That’s a distinction that’s been used by writers I’ve worked with. It might just be a British thing, because we have a greater concept of social class than other English-speaking countries.

-

#8

Commonest is poor grammar. Widely used, but makes me shudder.

-

#9

Sorry to resurrect an ancient thread, but «commoner, commonest» is an irregular comparative/superlative form. To my mind, using more and most common demonstrates ignorance of the irregular form. However, Merriam Webster doesn’t list the forms, implying that «common» is considered regular. Perhaps this is one of the manifold BE/AE stylistic differences?

-

#10

I didn’t know there was any stigma attached to «commonest», so I think Twoflower may be right about a BE/AE stylistic difference.

-

#11

I think that they’re both correct although I absolutely LOATHE «commonest» and would never use it.

![Frown :( :(]()

I presume you think that only the commonest people would actually say «commonest» ?

-

#12

Isn’t the general rule of comparative and superlative : -er and -est for adjectives of one or two syllables, more and most for those longer?

Which would make commonest correct, if a little inelegant.

I can hear in my head the narrative on TV nature programmes «One of the commonest forms of insect life on the planet is…………»

-

#13

But we add ‘-er’ and ‘-est’ only with two syllable adjectives that end in ‘-y’ like ‘happy’, ‘lucky’, ‘lazy’, etc. I’ve been also taught that we could use ‘more’ and ‘most’ with them when the situation is informal, e.g. writing a letter to a friend, although some grammarians and teachers don’t consider it correct. However, I have seen such examples in my textbook, which is written by native speakers. The Oxford Dictionary gives the comparative and superlative forms as ‘commoner’ and ‘commonest’.

-

#14

No, there are a number of two-syllable patterns that can be inflected, most commonly -le/-el as in subtler, simplest, cruellest; beyond that, we get into individual words rather than patterns, as it can be hard to think of multiple examples for each type, but certainly yellower, quieter, bitterest, all sound fairly natural. The thing about the -y adjectives is that we usually inflect them, whereas with the other disyllables that allow it (and not all do, most prominently those in -ing, -ish), it’s an alternative choice.

-

#15

I didn’t know there was any stigma attached to «commonest», so I think Twoflower may be right about a BE/AE stylistic difference.

I have no objections whatsoever to commoner/commonest: I happily use them whether the meaning is ‘occurring frequently’ or ‘lacking in social polish’. To suggest that they’re ‘mistakes’ in British English is … well, mistaken.

-

#16

Oxford Dictionary lists «commoner» and «commonest» as the comparative and superlative forms of «common». The Oxford Dictionary cannot be wrong.

-

#17

There is a usage note in the Collins Cobuild which makes a distinction between the available attributive and predicative forms:

The comparative and superlative forms of common are usually more common and most common. Commonest is sometimes used instead of most common in front of a noun.

Job sharing has become more common.

The disease is most common in adults over 40.

Stress is one of the commonest causes of insomnia.

-

#18

Still baffled.

I’d happily say/write:

Job-sharing is commoner today than it was 20 years ago.

The disease is commonest in adults over 40.

-

#19

Still baffled.

I’d happily say/write:

Job-sharing is commoner today than it was 20 years ago.

The disease is commonest in adults over 40.

Yuck.

Job sharing is commoner than Miss Brahms on Keeping Up Appearances (showing a lack of taste and refinement). What part of London is it from?

-

#20

Still baffled.

I’d happily say/write:

Job-sharing is commoner today than it was 20 years ago.

The disease is commonest in adults over 40.

I’m baffled too.

As Edison correctly points out (post #16) Oxford Dictionaries Online lists the forms commoner, commonest. So it seems odd to me that people are apparently trying to claim there’s something wrong with them.

Or maybe it’s just an AE/BE thing.

-

#21

Mystified by the Collins Cobuild entry quoted by Nat, the more so since it appears to be descriptive, not prescriptive; happy with Ewie’s sample sentences.

-

#22

Unlike Oxford Online, the editors of the OED clearly don’t think there is any need to list a standard form of the superlative. They use «commonest» themselves in 46 of their definitions and 21 of their etymologies. There’s also 424 quotations which use «commonest». «Most common» features in 99 definitions and 35 etymologies, and appears in 836 quotations.

-

#23

I think it depends on your meaning.

If common = plentiful (the opposite of rare), then without doubt, most common is preferable.

However, sometimes, common is used to mean «uncultured, dirty, lower-class». It’s maybe not very polite, but some people do use it. In this case, it is useful to use commonest, to make it clear that you are not talking about the frequency of occurrence.

That’s a distinction that’s been used by writers I’ve worked with. It might just be a British thing, because we have a greater concept of social class than other English-speaking countries.

I thought «commoner» means from a lower social class, when referred to as a noun, now I am confused about the difference between saying » a commoner » and » a commonest «. Would you please explain that?

-

#24

You are asking about the noun «commoner», which does not mean «from a lower social class», it means a person who is not a member of the aristocracy or royalty. This thread is about the comparative and superlative forms of the adjective «common». «A commonest» has no meaning.

Last edited: Nov 15, 2015

-

#25

The AHD agrees with the OED: commoner and commonest are standard as the comparative and superlative, respectively, of the adjective common.

That doesn’t mean one has to like them or use them. I don’t.

Предложения с «common words»

|

Avoid including your name or common words . |

Не используйте в пароле свое имя или общие слова . |

|

She could not speak even the common words of farewell. |

Она не смогла произнести даже общепринятые слова прощания. |

|

I am interested in a printed dictionary of common words concerning all PC-vocabulary. |

Меня интересует печатный словарь общих слов, касающихся всего ПК — словаря . |

|

Implementations of tag clouds also include text parsing and filtering out unhelpful tags such as common words , numbers, and punctuation. |

Реализация облаков тегов также включает синтаксический анализ текста и фильтрацию бесполезных тегов, таких как общие слова , цифры и знаки препинания. |

|

It has been estimated that over two thirds of the 3,000 most common words in modern Standard Chinese are polysyllables, the vast majority of those being disyllables. |

Было подсчитано, что более двух третей из 3000 наиболее распространенных слов в современном стандартном китайском языке являются многосложными, причем подавляющее большинство из них являются несложными. |

|

Studies that estimate and rank the most common words in English examine texts written in English. |

Исследования, оценивающие и ранжирующие наиболее распространенные слова в английском языке, изучают тексты, написанные на английском языке. |

|

As far as I know, the most common words for bishop in Greek are episkopos and presbuteros. |

Насколько мне известно, наиболее распространенными словами для обозначения епископа в греческом языке являются episkopos и presbuteros. |

|

A selected list of common words is presented below, under Documented list of common misspellings. |

Выбранный список общих слов представлен ниже, в разделе документированный список распространенных орфографических ошибок. |

|

There are also a few common words that have variable tone. |

Есть также несколько общих слов, которые имеют переменный тон. |

|

However, for the most common words , even that can be omitted. |

Однако для самых распространенных слов даже это можно опустить. |

|

Another similar one is words ending in -cion, of which the common words are coercion, scion, and suspicion. |

Еще один подобный пример — это слова , заканчивающиеся на — Цион, из которых наиболее распространенными являются слова принуждение, отпрыск и подозрение. |

|

A list of common words borrowed from local languages such as Hokkien and Malay appears in an appendix. |

Список общих слов, заимствованных из местных языков, таких как Хокиен и Малайский, приводится в приложении. |

|

It’s held in — the German word is the volk — in the people, in the common, instinctive wisdom of the plain people. |

Это лексема, олицетворяющая народ, — Volk с немецкого люди — общую, самобытную мудрость простых людей. |

|

I started to think about what makes words real, because a lot of people ask me, the most common thing I got from people is, Well, are these words made up? |

Я начал задумываться над тем, что делает слова реальными, потому что многие спрашивают чаще всего так: Эти слова что, придуманы? |

|

It had to be a coincidence, a common series of sounds that just happened to match an English word. |

Наверное, это всего лишь совпадение, случайный набор звуков, напоминающий английское слово . |

|

Besides, all these people need is some common sense advice and some kind words . |

Кроме того, все эти люди нуждаются в каком — нибудь здравом совете и каком — то добром слове . |

|

Hearteningly, that call is now bearing fruit in the form of A Common Word, in which Muslim and Christian clergy from around the world have engaged with each other. |

К счастью, этот призыв принес свои плоды в форме «Общего слова », в котором мусульманское и христианское духовенство заявили о необходимости сотрудничества друг с другом. |

|

For instance, the word said was used in messaging instead of was like, a common informal spoken phrase. |

Например, слово говорил использовалось сообщениях вместо а он такой говорит, что является неформальным разговорным выражением. |

|

The analysis measured the overlap in media consumed by users — in other words , the extent to which two randomly selected users consumed media in common. |

В анализе мы проследили, насколько совпадали используемые ими ресурсы, то есть установили общие границы использования СМИ у двух случайных лиц. |

|

And what puts us together is that we have a common, at least, global understanding of what the word business is, or what it should be. |

А соединяет нас вместе общее глубокое понимание значение слова бизнес, или того, чем это слово должно быть. |

|

Sunlight also found that members of Congress rarely use the 100 most common SAT words , which are likely very familiar to high school students. |

Sunlight также выяснил, что члены Конгресса редко используют 100 самых употребительных слов из школьного оценочного теста, которые должны быть хорошо известны школьникам старших классов. |

|

For non-common actions, you must type in the complete word and press save. |

Название нестандартного действия необходимо ввести полностью и нажать кнопку Сохранить. |

|

The words common and courtesy have opposite values. |

У слов взаимная и вежливость противоположные значения. |

|

What our common ancestors once darkly felt or clearly thought, this matter of millennia we today summarize in the short word shinto. |

То, что ясно или смутно тысячелетиями ощущали наши предки сегодня мы называем коротким словом синто. |

|

And how suffer him to leave her without saying one word of gratitude, of concurrence, of common kindness! |

Как допустила, чтобы они расстались без слова благодарности, без слова согласия с ее стороны — вообще без единого доброго слова ! |

|

Now as he had his wit (to use that word in its common signification) always ready, he bethought himself of making his advantage of this humour in the sick man. |

А так как был он человек, как говорится, себе на уме, то решил поживиться за счет причуды больного. |

|

They were common everyday words-the familiar, vague sounds exchanged on every waking day of life. |

То были банальные, повседневные слова , знакомые неясные звуки, какие можно услышать в любой день. |

|

They were speaking of common acquaintances, keeping up the most trivial conversation, but to Kitty it seemed that every word they said was determining their fate and hers. |

Они говорили об общих знакомых, вели самый ничтожный разговор, но Кити казалось, что всякое сказанное ими слово решало их и ее судьбу. |

|

It’s not a computer in the common sense of the word… it’s rather an electronic simulation system… with immense memory capacity. |

Это не компьютер в обычном понимании этого слова . Это скорее электронная имитационная система с повышенным объемом памяти. |

|

They’d like a word with you about the common cold. |

Они хотели бы поговорить с тобой о простуде. |

|

Two men who have a secret in common, and who, by a sort of tacit agreement, exchange not a word on the subject, are less rare than is commonly supposed. |

Два человека, связанные общей тайной, которые, как бы по молчаливому согласию, не перемолвятся о ней ни словом , далеко не такая редкость, как может показаться. |

|

Together they discovered that their faces… had many common features… often they were saying the same thing with the same words . |

Общими усилиями они обнаружили, что их лица имели много сходных черт. Часто бывало, что и говорили об одном и том же теми же словами . |

|

The use of English expressions is very common in the youth language, which combines them with verlan wordplay . |

Использование английских выражений очень распространено в молодежном языке, который сочетает их с игрой слов verlan. |

|

The boy could read and write all letters in the alphabet; however, had difficult in reading common monosyllabic words . |

Мальчик умел читать и писать все буквы алфавита; однако ему было трудно читать обычные односложные слова . |

|

In other words , the issue preclusion or collateral estoppel found in the common law doctrine of res judicata is not present in the civilian doctrine. |

Другими словами , вопрос о преюдиции или залоговом эстоппеле, встречающийся в доктрине общего права res judicata, отсутствует в гражданской доктрине. |

|

It therefore includes words such as mukluk, Canuck, and bluff, but does not list common core words such as desk, table or car. |

Поэтому он включает такие слова , как mukluk, Canuck и bluff, но не перечисляет общие ключевые слова , такие как стол, стол или автомобиль. |

|

Each word has a denotation common for all as well as a connotation that is unique for each individual. |

Каждое слово имеет общее для всех значение, а также коннотацию, которая уникальна для каждого человека. |

|

The common Chinese word wú 無 was adopted in the Sino-Japanese, Sino-Korean, and Sino-Vietnamese vocabularies. |

Общее китайское слово wú 無 было принято в китайско — японском, китайско — корейском и Китайско — вьетнамском словарях . |

|

Homonymic puns, another common type, arise from the exploitation of words which are both homographs and homophones. |

Омонимические каламбуры, еще один распространенный тип, возникают из эксплуатации слов, которые являются одновременно омографами и омофонами. |

|

Of course, it takes a lot more than having two words in common to cause a piece of music to be an adaptation. |

Конечно, требуется гораздо больше, чем два общих слова , чтобы заставить музыкальное произведение быть адаптацией. |

|

In the expression, the word spade refers to the instrument used to move earth, a very common tool. |

В этом выражении слово лопата относится к инструменту, используемому для перемещения Земли, очень распространенному инструменту. |

|

Of course, if South African English and British English use different spellings for a common word I didn’t know existed, my head will explode. |

Конечно, если южноафриканский английский и британский английский используют разные варианты написания для общего слова , о существовании которого я не знал, моя голова взорвется. |

|

In vernacular Arabic, contractions are a common phenomenon, in which mostly prepositions are added to other words to create a word with a new meaning. |

В просторечном арабском языке сокращения являются обычным явлением, в котором в основном предлоги добавляются к другим словам , чтобы создать слово с новым значением. |

|

Word play is quite common in oral cultures as a method of reinforcing meaning. |

Игра слов довольно распространена в устных культурах как метод усиления смысла. |

|

Word play can enter common usage as neologisms. |

Игра слов может войти в общее употребление как неологизмы. |

|

The beso-beso which originated from the Spanish word for kiss, is a common greeting in the Philippines similar to the mano. |

Beso — Бесо, которое произошло от испанского слова , означающего поцелуй, является распространенным приветствием на Филиппинах, похожим на mano. |

|

Thus native speakers will have similar but not identical scripts for words they have in common. |

Таким образом, носители языка будут иметь похожие, но не идентичные сценарии для слов, которые они имеют в общем. |

|

The word Bangla became the most common name for the region during the Islamic period. |

Слово Бангла стало самым распространенным названием этого региона в исламский период. |

|

The court ruled against Ren, claiming his name is a collection of common characters and as a result the search results were derived from relevant words . |

Суд вынес решение против Рена, утверждая, что его имя представляет собой набор общих символов, и в результате Результаты поиска были получены из соответствующих слов. |

|

At one time, common word-processing software adjusted only the spacing between words , which was a source of the river problem. |

В свое время распространенное программное обеспечение для обработки текстов регулировало только интервал между словами , что было источником проблемы с рекой. |

|

This usage mirrors the common meaning of the word’s etymological cousins in languages such as French and Spanish. |

Это употребление отражает общее значение этимологических двоюродных братьев слова в таких языках, как французский и испанский. |

|

In general, do not create links to plain English words , including common units of measurement. |

В общем, не создавайте ссылок на простые английские слова , включая общие единицы измерения. |

|

The word is possibly a portmanteau from Latin sylvestris and nympha, sylvestris being a common synonym for sylph in Paracelsus. |

Это слово , возможно, является переносным от латинского sylvestris и nympha, sylvestris является общим синонимом сильфы в Парацельсе. |

|

In Northern England, Including the Lake District and Yorkshire Dales, fellwalking describes hill or mountain walks, as fell is the common word for both features there. |

В Северной Англии, включая Озерный край и йоркширские долины, fellwalking описывает горные или горные прогулки,поскольку fell — это общее слово для обоих признаков. |

|

Antidisestablishmentarianism is the longest common example of a word formed by agglutinative construction. |

Антидисстаблишментаризм — самый длинный распространенный пример слова , образованного агглютинативной конструкцией. |

|

In general, it is common practice to use standard characters to transcribe Chinese dialects when obvious cognates with words in Standard Mandarin exist. |

В целом, общепринятой практикой является использование стандартных символов для транскрипции китайских диалектов, когда существуют очевидные родственные связи со словами в стандартном мандаринском языке. |

|

The word was assimilated into English as orthopædics; the ligature æ was common in that era for ae in Greek- and Latin-based words . |

Это слово было ассимилировано в английском языке как orthopædics; лигатура æ была распространена в ту эпоху для ae в греческих и латинских словах . |

|

As with dharma, the word adharma includes and implies many ideas; in common parlance, adharma means that which is against nature, immoral, unethical, wrong or unlawful. |

Как и в случае с Дхармой, слово адхарма включает в себя и подразумевает множество идей; в просторечии адхарма означает то, что противоречит природе, аморально, неэтично, неправильно или незаконно. |

|

It is an affectation, indeed, not very common among merchants, and very few words need be employed in dissuading them from it. |

Это действительно притворство, не очень распространенное среди торговцев, и очень мало слов нужно употребить, чтобы отговорить их от него. |

|

Today, it is common to require the actors to mime their hints without using any spoken words , which requires some conventional gestures. |

Сегодня принято требовать от актеров мимических намеков без использования каких — либо произносимых слов, что требует некоторых условных жестов. |

The

outline of the problem discussed

1.

The main types of words in English and their morphological structure.

2.

Affixation (or derivation).

3.

Compounding.

4.

Conversion.

5.

Abbreviation (shortening).

Word-formation

is the process of creating new words from the material

available

in the language.

Before

turning to various processes of word-building in English, it would be

useful

to analyze the main types of English words and their morphological

structure.

If

viewed structurally, words appear to be divisible into smaller units

which are

called

morphemes.

Morphemes

do not occur as free forms but only as constituents of

words.

Yet they possess meanings of their own.

All

morphemes are subdivided into two large classes: roots

(or

radicals)

and

affixes.

The

latter, in their turn, fall into prefixes

which

precede the root in the

structure

of the word (as in re-real,

mis-pronounce, un-well) and

suffixes

which

follow

the root (as in teach-er,

cur-able, dict-ate).

Words

which consist of a root and an affix (or several affixes) are called

derived

words or

derivatives

and

are produced by the process of word-building

known

as affixation

(or

derivation).

Derived

words are extremely numerous in the English vocabulary.

Successfully

competing with this structural type is the so-called root

word which

has

only

a root morpheme in its structure. This type is widely represented by

a great

number

of words belonging to the original English stock or to earlier

borrowings

(house,

room, book, work, port, street, table, etc.), and,

in Modern English, has been

greatly

enlarged by the type of word-building called conversion

(e.g.

to

hand, v.

formed

from the noun hand;

to can, v.

from can,

n.;

to

pale,

v. from pale,

adj.;

a

find,

n.

from to

find, v.;

etc.).

Another

wide-spread word-structure is a compound

word consisting

of two or

more

stems (e.g. dining-room,

bluebell, mother-in-law, good-for-nothing).

Words of

this

structural type are produced by the word-building process called

composition.

The

somewhat odd-looking words like flu,

lab, M.P., V-day, H-bomb are

called

curtailed

words and

are produced by the way of word-building called shortening

(abbreviation).

The

four types (root words, derived words, compounds, shortenings)

represent

the

main structural types of Modern English words, and affixation

(derivation),

conversion,

composition and shortening (abbreviation) — the most productive ways

of

word-building.

83

The

process of affixation

consists

in coining a new word by adding an affix or

several

affixes to some root morpheme. The role of the affix in this

procedure is very

important

and therefore it is necessary to consider certain facts about the

main types

of

affixes.

From

the etymological point of view affixes are classified into the same

two

large

groups as words: native and borrowed.

Some

Native Suffixes

-er

worker,

miner,

teacher,

painter,

etc.

-ness

coldness,

loneliness,

loveliness,

etc.

-ing

feeling,

meaning,

singing,

reading,

etc.

-dom

freedom,

wisdom,

kingdom,

etc.

-hood

childhood,

manhood,

motherhood,

etc.

-ship

friendship,

companionship,

mastership,

etc.

Noun-forming

-th

length,

breadth,

health,

truth,

etc.

-ful

careful,

joyful,

wonderful,

sinful,

skilful,

etc.

-less

careless,

sleepless,

cloudless,

senseless,

etc.

-y

cozy,

tidy,

merry,

snowy,

showy,

etc.

-ish

English,

Spanish,

reddish,

childish,

etc.

-ly

lonely,

lovely,

ugly,

likely,

lordly,

etc.

-en

wooden,

woollen,

silken,

golden,

etc.

Adjective-forming

-some

handsome, quarrelsome, tiresome, etc.

Verb-

forming

-en

widen,

redden,

darken,

sadden,

etc.

Adverb-

forming

-ly

warmly,

hardly,

simply,

carefully,

coldly,

etc.

Borrowed

affixes, especially of Romance origin are numerous in the English

vocabulary.

We can recognize words of Latin and French origin by certain suffixes

or

prefixes;

e. g. Latin

affixes:

-ion,

-tion, -ate,

-ute

,

-ct,

-d(e), dis-, -able, -ate,

-ant,

—

ent,

-or, -al, -ar in

such words as opinion,

union, relation, revolution, appreciate,

congratulate,

attribute, contribute, , act, collect, applaud, divide, disable,

disagree,

detestable,

curable, accurate, desperate, arrogant, constant, absent, convenient,

major,

minor, cordial, familiar;

French

affixes –ance,

—ewe,

-ment, -age, -ess, -ous,

en-

in

such words as arrogance,

intelligence, appointment, development, courage,

marriage,

tigress, actress, curious, dangerous, enable, enslaver.

Affixation

includes a) prefixation

–

derivation of words by adding a prefix to

full

words and b) suffixation

–

derivation of words by adding suffixes to bound

stems.

Prefixes

and suffixes have their own valency, that is they may be added not to

any

stem at random, but only to a particular type of stems:

84

Prefix

un-

is

prefixed to adjectives (as: unequal,

unhealthy), or

to adjectives

derived

from verb stems and the suffix -able

(as:

unachievable,

unadvisable), or

to

participial

adjectives (as: unbecoming,

unending, unstressed, unbound); the

suffix —

er

is

added to verbal stems (as: worker,

singer, or

cutter,

lighter), and

to substantive

stems

(as: glover,

needler); the

suffix -able

is

usually tacked on to verb stems (as:

eatable,

acceptable); the

suffix -ity

in

its turn is usually added to adjective stems

with

a passive meaning (as: saleability,

workability), but

the suffix —ness

is

tacked on

to

other adjectives, having the suffix -able

(as:

agreeableness.

profitableness).

Prefixes

and suffixes are semantically distinctive, they have their own

meaning,

while the root morpheme forms the semantic centre of a word. Affixes

play

a

dependent role in the meaning of the word. Suffixes have a

grammatical meaning,

they

indicate or derive a certain part of speech, hence we distinguish:

noun-forming

suffixes,

adjective-forming suffixes, verb-forming suffixes and adverb-forming

suffixes.

Prefixes change or concretize the meaning of the word, as: to

overdo (to

do

too

much),

to underdo (to

do less than one can or is proper),

to outdo (to

do more or

better

than),

to undo (to

unfasten, loosen, destroy the result, ruin),

to misdo (to

do

wrongly

or unproperly).

A

suffix indicates to what semantic group the word belongs. The suffix

-er

shows

that the word is a noun bearing the meaning of a doer of an action,

and the

action

is denoted by the root morpheme or morphemes, as: writer,

sleeper, dancer,

wood-pecker,

bomb-thrower, the

suffix -ion/-tion,

indicates

that it is a noun

signifying

an action or the result of an action, as: translation

‘a

rendering from one

language

into another’ (an

act, process) and

translation

‘the

product of such

rendering’;

nouns with the suffix -ism

signify

a system, doctrine, theory, adherence to

a

system, as: communism,

realism; coinages

from the stem of proper names are

common,.

as Darwinism.

Affixes

can also be classified into productive

and

non-productive

types.

By

productive

affixes we

mean the ones, which take part in deriving new words in a

particular

period of language development. The best way to identify productive

affixes

is to look for them among neologisms

and

so-called nonce-words,

i.e.

words

coined

and used only for this particular occasion. The latter are usually

formed on the

level

of living speech and reflect the most productive and progressive

patterns in

word-building.

When a literary critic writes about a certain book that it is an

unputdownable

thriller, we

will seek in vain this strange and impressive adjective in

dictionaries,

for it is a nonce-word coined on the current pattern of Modern

English

and

is evidence of the high productivity of the adjective-forming

borrowed suffix –

able

and

the native prefix un-,

e.g.: Professor Pringle was a thinnish, baldish,

dyspeptic-lookingish

cove with an eye like a haddock.(From

Right-Ho, Jeeves by P.G.

Wodehouse)

The

adjectives thinnish

and

baldish

bring

to mind dozens of other adjectives

made

with the same suffix: oldish,

youngish, mannish, girlish, fattish, longish,

yellowish,

etc. But

dyspeptic-lookingish

is

the author’s creation aimed at a humorous

effect,

and, at the same time, providing beyond doubt that the suffix –ish

is

a live and

active

one.

85

The

same is well illustrated by the following popular statement: “I

don’t like

Sunday

evenings: I feel so Mondayish”. (Mondayish is

certainly a nonce-word.)

One

should not confuse the productivity of affixes with their frequency

of

occurrence

(use). There are quite a number of high-frequency affixes which,

nevertheless,

are no longer used in word-derivation (e.g. the adjective-forming

native

suffixes

–ful,

-ly; the

adjective-forming suffixes of Latin origin –ant,

-ent, -al which

are

quite frequent).

Some

Productive Affixes

Some

Non-Productive Affixes

Noun-forming

suffixes

-th,

-hood

Adjective-forming

suffixes

—ly,

-some, -en, -ous

Verb-forming

suffix -en

Compound

words are

words derived from two or more stems. It is a very old

word-formation

type and goes back to Old English. In Modern English compounds

are

coined by joining one stem to another by mere juxtaposition, as

raincoat,

keyhole,

pickpocket,

red-hot, writing-table. Each

component of a compound coincides

with

the word. Compounds are the commonest among nouns and adjectives.

Compound

verbs are few in number, as they are mostly the result of conversion

(as,

to

weekend) and

of back-formation (as, to

stagemanage).

From

the point of view of word-structure compounds consist of free stems

and

may

be of different structure: noun stems + noun stem (raincoat);

adjective

stem +

noun

stem (bluebell);

adjective

stem + adjective stem (dark-blue);

gerundial

stem +

noun

stem (writing-table);

verb

stem + post-positive stem (make-up);

adverb

stem +

adjective

stem (out-right);

two

noun stems connected by a preposition (man-of-war)

and

others. There are compounds that have a connecting vowel (as,

speedometer,

handicraft),

but

it is not characteristic of English compounds.

Compounds

may be idiomatic

and

non-idiomatic.

In idiomatic compounds the

meaning

of each component is either lost or weakened, as buttercup

(лютик),

chatter-box

(болтун).

These

are entirely

demotivated compounds. There

are also motivated

compounds,

as lifeboat

(спасательная

лодка). In non-idiomatic compounds the

Noun-forming

suffixes

—er,

-ing,

—ness,

-ism (materialism),

-ist

(impressionist),

-ance

Adjective-forming

suffixes

—y,

-ish, -ed (learned),

—able,

—less

Adverb-forming

suffix

—ly

Verb-forming

suffixes

—ize/-ise

(realize),

—ate

Prefixes

un-

(unhappy),re-

(reconstruct),

dis-

(disappoint)

86

meaning

of each component is retained, as apple-tree,

bedroom, sunlight. There

are

also

many border-line cases.

The

components of compounds may have different semantic relations; from

this

point of view we can roughly classify compounds into endocentric

and

exocentric

compounds.

In endocentric compounds the semantic centre is found

within

the compound and the first element determines the other, as

film-star,

bedroom,

writing-table.

In

exocentric compounds there is no semantic centre, as

scarecrow.

In

Modern English, however, linguists find it difficult to give criteria

for

compound

nouns; it is still a question of hot dispute. The following criteria

may be

offered.

A compound noun is characterized by a) one word or hyphenated

spelling, b)

one

stress, and by c) semantic integrity. These are the so-called

“classical

compounds”.

It

is possible that a compound has only two of these criteria, for

instance, the

compound

words headache,

railway have

one stress and hyphenated or one-word

spelling,

but do not present a semantic unity, whereas the compounds

motor-bike,

clasp-knife

have

hyphenated spelling and idiomatic meaning, but two even stresses

(‘motor-‘bike,

‘clasp-‘knife).

The word apple-tree

is

also a compound; it is spelt either

as

one word or is hyphenated, has one stress (‘apple-tree),

but it is not idiomatic. The

difficulty

of defining a compound lies in spelling which might be misleading, as

there

are

no hard and fast rules of spelling the compounds: three ways of

spelling are

possible:

(‘dockyard,

‘dock yard and

dock-yard).

The

same holds true for the stress

that

may differ from one reference-book to another.

Since

compounds may have two stresses and the stems may be written

separately,

it is difficult to draw the line between compounds proper and nominal

word-combinations

or syntactical combinations. In a combination of words each

element

is stressed and written separately. Compare the attributive

combination

‘black

‘board, a

board which is black (each element has its own meaning; the first

element

modifies the second) and the compound ‘blackboard’,

a

board or a sheet of

slate

used in schools for teaching purposes (the word has one stress and

presents a

semantic

unit). But it is not always easy as that to draw a distinction, as

there are

word-combinations

that may present a semantic unity, take for instance: green

room

(a

room in a theatre for actors and actresses).

Compound

derivatives are

words, usually nouns and adjectives, consisting of

a

compound stem and a suffix, the commonest type being such nouns as:

firstnighter,

type-writer,

bed-sitter, week-ender, house-keeping, well-wisher, threewheeler,

old-timer,

and

the adjectives: blue-eyed,

blond-haired, four-storied, mildhearted,

high-heeled.

The

structure of these nouns is the following: a compound stem

+

the suffix -er,

or

the suffix -ing.

Adjectives

have the structure: a compound stem, containing an adjective (noun,

numeral)

stem and a noun stem + the suffix -ed.

In

Modern English it is an extremely

productive

type of adjectives, e.g.: big-eyed,

long-legged, golden-haired.

In

Modern English it is common practice to distinguish also

semi-suffixes, that

is

word-formative elements that correspond to full words as to their

lexical meaning

and

spelling, as -man,

-proof, -like: seaman, railroadman, waterproof, kiss-proof,

ladylike,

businesslike. The

pronunciation may be the same (cp. proof

[pru:f]

and

87

waterproof

[‘wL:tq

pru:f],

or differ, as is the case with the morpheme -man

(cp.

man

[mxn]

and seaman

[‘si:mqn].

The

commonest is the semi-suffix -man

which

has a more general meaning —

‘a

person of trade or profession or carrying on some work’, as: airman,

radioman,

torpedoman,

postman, cameramen, chairman and

others. Many of them have

synonyms

of a different word structure, as seaman

— sailor, airman — flyer,

workman

— worker; if

not a man but a woman

of

the trade or profession, or a person

carrying

on some work is denoted by the word, the second element is woman,

as

chairwoman,

air-craftwoman, congresswoman, workwoman, airwoman.

Conversion

is

a very productive way of forming new words in English, chiefly

verbs

and not so often — nouns. This type of word formation presents one

of the

characteristic

features of Modern English. By conversion we mean derivation of a

new

word from the stem of a different part of speech without the addition

of any

formatives.

As a result the two words are homonymous, having the same

morphological

structure and belonging to different parts of speech.

Verbs

may be derived from the stem of almost any part of speech, but the

commonest

is the derivation from noun stems as: (a)

tube — (to) tube; (a) doctor —

(to)

doctor, (a) face—(to) face; (a) waltz—(to) waltz; (a) star—(to)

star; from

compound

noun stems as: (a)

buttonhole — (to) buttonhole; week-end — (to) weekend.

Derivations

from the stems of other parts of speech are less common: wrong—

(to)

wrong; up — (to) up; down — (to) down; encore — (to) encore.

Nouns

are

usually

derived from verb stems and may be instanced by such nouns as: (to)

make—

a

make; (to) cut—(a) cut; to bite — (a) bite, (to) drive — (a)

drive; to smoke — (a)

smoke;

(to) walk — (a) walk. Such

formations frequently make part of verb — noun

combinations

as: to

take a walk, to have a smoke, to have a drink, to take a drive, to

take

a bite, to give a smile and

others.

Nouns

may be also derived from verb-postpositive phrases. Such formations

are

very common in Modern English, as for instance: (to)

make up — (a) make-up;

(to)

call up — (a) call-up; (to) pull over — (a) pullover.

New

formations by conversion from simple or root stems are quite usual;

derivatives

from suffixed stems are rare. No verbal derivation from prefixed

stems is

found.

The

derived word and the deriving word are connected semantically. The

semantic

relations between the derived and the deriving word are varied and

sometimes

complicated. To mention only some of them: a) the verb signifies the

act

accomplished

by or by means of the thing denoted by the noun, as: to

finger means

‘to

touch with the finger, turn about in fingers’; to

hand means

‘to give or help with

the

hand, to deliver, transfer by hand’; b) the verb may have the meaning

‘to act as the

person

denoted by the noun does’, as: to

dog means

‘to follow closely’, to

cook — ‘to

prepare

food for the table, to do the work of a cook’; c) the derived verbs

may have

the

meaning ‘to go by’ or ‘to travel by the thing denoted by the noun’,

as, to

train

means

‘to go by train’, to

bus — ‘to

go by bus’, to

tube — ‘to

travel by tube’; d) ‘to

spend,

pass the time denoted by the noun’, as, to

winter ‘to pass

the winter’, to

weekend

— ‘to

spend the week-end’.

88

Derived

nouns denote: a) the act, as a

knock, a hiss, a smoke; or

b) the result of

an

action, as a

cut, a find, a call, a sip, a run.

A

characteristic feature of Modern English is the growing frequency of

new

formations

by conversion, especially among verbs.

Note.

A grammatical homonymy of two words of different parts of speech —

a

verb

and a noun, however, does not necessarily indicate conversion. It may

be the

result

of the loss of endings as well. For instance, if we take the

homonymic pair love

— to

love and

trace it back, we see that the noun love

comes

from Old English lufu,

whereas

the verb to

love—from

Old English lufian,

and

the noun answer

is

traced

back

to the Old English andswaru,

but

the verb to

answer to

Old English

andswarian;

so

that it is the loss of endings that gave rise to homonymy. In the

pair

bus

— (to) bus, weekend — (to) weekend homonymy

is the result of derivation by

conversion.

Shortenings

(abbreviations)

are words produced either by means of clipping

full

word or by shortening word combinations, but having the meaning of

the full

word

or combination. A distinction is to be observed between graphical

and

lexical

shortenings;

graphical abbreviations are signs or symbols that stand for the full

words

or combination of words only in written speech. The commonest form is

an

initial

letter or letters that stand for a word or combination of words. But

to prevent

ambiguity

one or two other letters may be added. For instance: p.

(page),

s.

(see),

b.

b.

(ball-bearing).

Mr

(mister),

Mrs

(missis),

MS

(manuscript),

fig.

(figure). In oral

speech

graphical abbreviations have the pronunciation of full words. To

indicate a

plural

or a superlative letters are often doubled, as: pp.

(pages). It is common practice

in

English to use graphical abbreviations of Latin words, and word

combinations, as:

e.

g. (exampli

gratia), etc.

(et cetera), i.

e. (id

est). In oral speech they are replaced by

their

English equivalents, ‘for

example’,

‘and

so on’,

‘namely‘,

‘that

is’,

‘respectively’.

Graphical

abbreviations are not words but signs or symbols that stand for the

corresponding

words. As for lexical

shortenings,

two main types of lexical

shortenings

may be distinguished: 1) abbreviations

or

clipped

words (clippings)

and

2) initial

words (initialisms).

Abbreviation

or

clipping

is

the result of reduction of a word to one of its

parts:

the meaning of the abbreviated word is that of the full word. There

are different

types

of clipping: 1) back-clipping—the

final part of the word is clipped, as: doc

—

from

doctor,

lab — from

laboratory,

mag — from

magazine,

math — from

mathematics,

prefab —

from prefabricated;

2) fore-clipping

—

the first part of the

word

is clipped as: plane

— from

aeroplane,

phone — from

telephone,

drome —

from

aerodrome.

Fore-clippings

are less numerous in Modern English; 3) the

fore

and

the back parts of the word are clipped and the middle of the word is

retained,

as: tec

— from

detective,

flu — from

influenza.

Words

of this type are few

in

Modern English. Back-clippings are most numerous in Modern English

and are

characterized

by the growing frequency. The original may be a simple word (as,

grad—from

graduate),

a

derivative (as, prep—from

preparation),

a

compound, (as,

foots

— from

footlights,

tails — from

tailcoat),

a

combination of words (as pub —

from

public

house, medico — from

medical

student). As

a result of clipping usually

nouns

are produced, as pram

— from

perambulator,