As already

mentioned, only those combinations of words (or single

words) which convey communication are sentences —

the

object of

syntax. All other combinations of words regularly formed in the

process of speech are the object of morphology as well as single

words. Like separate words they name things, phenomena, actions,

qualities, etc., but in a complex way, for example: manners

and

table

manners, blue and

dark

blue, speak and

speak

loudly. Like

separate words they serve as a building material for sentences.

70

21

The

combinability of words is as a rule determined by their meanings,

not their forms. Therefore not every sequence of words may be

regarded as a combination of words. In the sentence Frankly,

my friend, I have told you the truth neither

Frankly,

my friend nor

friend,

I …

are

combinations of words since their meanings are detached and do not

unite them.

On the

other hand, some words may be inserted between the components of a

word combination without breaking it. Compare: a) read

books; b)

read

many books; c)

read

very many books. In

case (a) the combination read

books is

uninterrupted.

In

cases (b) and (c) it is interrupted,

or

discontinuous

(read

…

books).

The

combinability of words depends on their lexical, grammatical and

lexico-grammatical meanings. It is owing to lexical meanings of the

corresponding lexemes that the word hot

can be

combined with the words water,

temper, news, dog and

is hardly combinable with the words ice,

square, information, cat.

The

lexico-grammatical meanings of -er

in

runner

(a

noun) and -ly

in

quickly

(an

adverb) do not go together and prevent these words from forming a

combination, whereas quick

runner and

run

quickly are

regular word combinations.

The

combination ^students

writes is

impossible owing to the grammatical meanings of the corresponding

grammemes (Remark:

with «*»

we

mark grammatically incorrect word-combinations or sentences).

Thus one

may speak of lexical,

grammatical and

lexico-grammatical

combinability,

or the combinability of lexemes, grammemes and parts of speech.

Each word

belonging to a certain part of speech is characterized by valency

(валентнють)

or,

in other words, the combinability of lexical

units. For example, in the sentence /

tell

you a joke the

verb tell

is

two valent, and in the sentence /

will

tell you a joke about a Scotchman —

three

valent. We can also say that modal verbs are valent for infinitives

and not valent for gerunds, e.g. I

can’t sing; nouns

are valent for an article, e.g. a

(the) table, that

is modal verbs are combined with infinitives not gerunds, and nouns

are practically the only part of speech that can be combined with

articles.

It is

convenient to distinguish right-hand

and

left-hand

l

onnections or combinability. In the combination my

friend the

word my

has

a right-hand connection with the word friend

and

the latter has n lelt-hand connection with the word my.

With

analytical forms inside

and

outside

connections

are also possible.

In the combination has

already done the

verb has an inside connection

with the adverb and the latter has an outside connection with the

verb.

It

will also be expedient to distinguish unilateral,

bilateral and

multilateral

combinability

(одностороння,

двостороння та багатосто-роння

сполучуванкяъ). For

instance, we may say that the articles in English have unilateral

right-hand connections with nouns: a

book, the hoy. Such

linking words as prepositions, conjunctions, link verbs and modal

verbs are characterized by bilateral combinability: book

of John, John and Marry, this is John, the boy must leave. Most

verbs may have:

/его (Go!),

unilateral

(boys

<r-jump),

bilateral

(Krdid-^-it),

p 1

i у

and

multilateral (Yesterday

I <—

saw—>

him

there) I

Onnections. In other words, the combinability of verbs is variable.

One

should also distinguish direct

and

indirect

connections.

In (he

combination Look

at him the

connection between look

and

at,

be!

ween at

and

him

are

direct, whereas the connection between look

ind

him

is

indirect, though the preposition at

[24;

28-31].

■ 5. The

notions of grammatical opposition

and grammatical category

There

is essential difference in the way lexical and grammatical meanings

exist in the language and occur in speech. Lexical meanings i

in be found in a bunch only in a dictionary or in a memory of a man,

0Г,

scientifically,

in the lexical system of a language. In actual speech .i lexical

morpheme displays only one meaning of the bunch in each case,

and that meaning is singled out by the context or the situation of

ipeech

(in grammar terms, syntagmatically). As mentioned already, words

of the same lexeme convey different meanings in different

lurroundings.

22

23

The

meanings of a grammatical morpheme always come together in the word.

In accordance with their relative nature they can be singled out

only relatively in contrast to the meanings of other grammatical

morphemes (in grammar terms, paradigmatically).

Supposing

we want to single out the meaning of «non-continuous aspect»

in the word runs.

We

have then to find another word

which has all the meanings of the word runs except that of

«non-continuous

aspect». The only word that meets these requirements is the

analytical word is

running. Run and

is

running belong

to the same lexeme

and their lexical meanings are identical. As to the grammatical

meanings

the two words do not differ in tense («present»), number

(«singular»), person («third»), mood

(«indicative»), etc. They differ only in aspect. The word

runs

has

the meaning of «non-continuous aspect» and is

running —

that

of «continuous aspect».

When

opposed, the two words, runs

and

is

running, form

a particular language unit. All their meanings but those of aspects

counterbalance

one another and do not count. Only the two particular

meanings

of «non-continuous» and «continuous» aspect

united by the general

meaning

of «aspect» are revealed in this opposition

or

opposeme.

The

general meaning of this opposeme («aspect») manifests

itself in the two particular meanings («non-continuous aspect»

and «continuous aspect») of the opposite

members (or

opposites)

[24;

22-24].

Thus,

the elements which the opposition/opposeme is composed of

are called opposites

or

members

of the opposition. Opposites

can be different: 1)

non-marked,

2) marked.

Compare the pair of noun forms table

—

tables.

Together

they create the «number» opposeme, where table

represents

the singular number expressed by a zero morpheme that is why it is

called the non-marked member of the opposition, and tables

— the

plural number expressed by the positive morpheme -s

is

called the marked member of the opposition. Non-marked opposite is

used more often than the marked opposite is. The marked opposite is

peculiar by its limited use.

Ferdinand

de Saussure claimed that everything in language is based

on opposition. On phonetic level we have opposition of sounds. On

all levels of the language we have opposition. Any grammatical

form has got its contrast or

counterpart. Together they make up a grammatical category.

A part

of speech is

characterized by its grammatical

categories manifested

in the opposemes

(the

elements of the opposition

—

оппозема, член опозицп) and

paradigms of its lexemes. Nouns have

the categories of number and case. Verbs possess the categories of

tense, voice, mood etc. That is why paradigms belonging to different

parts of speech are different. The paradigm of a verb lexeme is

long: write,

writes, wrote, will write, is writing etc.

The paradigm of n noun lexeme is much shorter: sister,

sister’s, sisters, sisters’. The

paradigm of an adjective lexeme is still shorter: cold,

colder, coldest. The

paradigm of an adverb always

consists

only of one word.

Thus, the paradigm of a

lexeme shows what part of speech the lexeme belongs to.

It

must be borne in mind, however, that not all the lexemes of a pari

of speech have the same paradigms. Compare:

sister book information

sister’s books —

sisters — —

sisters‘ — —

The

first lexeme has opposemes of two grammatical categories: number and

case. The second lexeme has only one opposeme —

that

of number.

It has no case opposemes. The third lexeme is outside both

I’iilegories:

it has no opposemes at all. We may say that the number (■pposeme

with its opposite grammatical meanings of «singularity»

iind «plurality» is neutralized

in

nouns like information,

bread, milk etc.

owing to their lexical meaning which can hardly be associated wilh

«oneness» or «more-than-oneness».

We may

define neutralization

as

the

reduction of an opposeme to one of its members under certain

circumstances. This

member may be

tailed

the

member of neutralization. Usually

it is the unmarked member

of an opposeme.

The term

grammatical

category implies

that: I) there

exist different morphological forms in the words of a pari

of speech possessing different referential meanings;

7Л

25

2) the

oppositions of different forms possessing referential meanings

are systematic that is they cover the whole class of words of that

part of speech.

In other

words a grammatical

category is

a systematic

opposition of different morphological forms possessing different

referential meanings. Each

grammatical category is composed of at least two contrasting forms.

Otherwise category would stop existing.

In

general, an opposeme of any grammatical category consists of as many

members (or opposites) as there are particular manifestations of the

general meaning. Thus, a morphological

opposeme is

a

minimum set of words revealing (by the difference in their forms)

only (and all) the particular manifestations of some general

grammatical meaning. Any morphological category is the system of

such opposemes whose members differ in form to express only (and

all) the particular manifestations of the general meaning of the

category [24;

23-24].

Grammatical

category unites

in itself particular grammatical

meanings. For

example, the grammatical category of gender unites the meanings of

the masculine, feminine, neuter and common genders in

the Ukrainian language. Each grammatical category is connected, as a

minimum, with two forms. For example, the grammatical category of

number comprises the forms of singularity and plurality.

Grammatical

meaning is

an abstract meaning added to the lexical meaning of a word,

expressing its relations other words or classes

of words. As a rule, a word has several grammatical meanings.

Grammatical

meanings are realized in a grammatical

word form.

Grammatical

form of a word is

the variety of the same word differing from other forms of this word

by its grammatical meaning. For example, in the Ukrainian word-form

батьку

the

ending -y

expresses

the grammatical meaning of the masculine gender, singular number,

dative case.

Grammatical

form of a word can be simple

(synthetic), in

which the grammatical meanings are formed by the ending, suffix,

prefix or stress, etc. (дощ

— дощ — дощем); or

composite

(analytical), created

by adding several words (буду

говорити, быыи привабливий). The

analytical-synthetic

grammatical

word form is a

I

ombination of two previous types of word forms. For example, в

xuiaepcumemi

(the

local case is expressed by the flexion and the preposition); малював

би, малювала б (the

grammatical meaning of number

and gender is expressed by the form of the main verb, and the

meaning

of the conditional mood —

by

the particle би)

[2; 40-41].

Соседние файлы в предмете [НЕСОРТИРОВАННОЕ]

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

As already mentioned, only those combinations of words (or single words) which convey communication are sentences – the object of syntax. All other combinations of words regularly formed in the process of speech are the object of morphology as well as single words. Like separate words they name things, phenomena, actions, qualities, etc., but in a complex way, for example: manners and table manners, blue and dark blue, speak and speak loudly. Like separate words they serve as a building material for sentences.

The combinability of words is as a rule determined by their meanings, not their forms. Therefore not every sequence of words may be regarded as a combination of words. In the sentence Frankly, my friend, I have told you the truth neither Frankly, my friend nor friend, I … are combinations of words since their meanings are detached and do not unite them.

On the other hand, some words may be inserted between the components of a word combination without breaking it. Compare:

a) read books; b) read many books; c) read very many books.

In case (a) the combination read books is uninterrupted. In cases (b) and (c) it is interrupted, or discontinuous (read … books).

The combinability of words depends on their lexical, grammatical and lexico-grammatical meanings. It is owing to lexical meanings of the corresponding lexemes that the word hot can be combined with the words water, temper, news, dog and is hardly combinable with the words ice, square, information, cat.

The lexico-grammatical meanings of -er in runner (a noun) and -ly in quickly (an adverb) do not go together and prevent these words from forming a combination, whereas quick runner and run quickly are regular word combinations.

The combination * students writes is impossible owing to the grammatical meanings of the corresponding grammemes (Remark: with “*” we mark grammatically incorrect word-combinations or sentences).

Thus one may speak of lexical, grammatical and lexico-grammatical combinability, or the combinability of lexemes, grammemes and parts of speech.

Each word belonging to a certain part of speech is characterized by valency (валентність) or, in other words, the combinability of lexical units. For example, in the sentence I tell you a joke the verb tell is two valent, and in the sentence I will tell you a joke about a Scotchman – three valent. We can also say that modal verbs are valent for infinitives and not valent for gerunds, e.g. I can’t sing; nouns are valent for an article, e.g. a (the) table, that is modal verbs are combined with infinitives not gerunds, and nouns are practically the only part of speech that can be combined with articles.

It is convenient to distinguish right-hand and left-hand connections or combinability. In the combination my friend the word my has a right-hand connection with the word friend and the latter has a left-hand connection with the word my.

With analytical forms inside and outside connections are also possible. In the combination has already done the verb has an inside connection with the adverb and the latter has an outside connection with the verb.

It will also be expedient to distinguish unilateral, bilateral and multilateral combinability (одностороння, двостороння та багатостороння сполучуваність). For instance, we may say that the articles in English have unilateral right-hand connections with nouns: a book, the boy. Such linking words as prepositions, conjunctions, link verbs and modal verbs are characterized by bilateral combinability: book of John, John and Marry, this is John, the boy must leave. Most verbs may have:

– zero (Go!),

– and multilateral (Yesterday I saw him there) connections. In other words, the combinability of verbs is variable.

One should also distinguish direct and indirect connections. In the combination Look at him the connection between look and at, between at and him are direct, whereas the connection between look and him is indirect, though the preposition at [24; 28–31].

5. The notions of grammatical opposition

and grammatical category

There is essential difference in the way lexical and grammatical meanings exist in the language and occur in speech. Lexical meanings can be found in a bunch only in a dictionary or in a memory of a man, or, scientifically, in the lexical system of a language. In actual speech a lexical morpheme displays only one meaning of the bunch in each case, and that meaning is singled out by the context or the situation of speech (in grammar terms, syntagmatically). As mentioned already, words of the same lexeme convey different meanings in different surroundings.

The meanings of a grammatical morpheme always come together in the word. In accordance with their relative nature they can be singled out only relatively in contrast to the meanings of other grammatical morphemes (in grammar terms, paradigmatically).

Supposing we want to single out the meaning of “non-continuous aspect” in the word runs. We have then to find another word which has all the meanings of the word runs except that of “non-continuous aspect”. The only word that meets these requirements is the analytical word is running. Run and is running belong to the same lexeme and their lexical meanings are identical. As to the grammatical meanings the two words do not differ in tense (“present”), number (“singular”), person (“third”), mood (“indicative”), etc. They differ only in aspect. The word runs has the meaning of “non-continuous aspect” and is running – that of “continuous aspect”.

When opposed, the two words, runs and is running, form a particular language unit. All their meanings but those of aspects counterbalance one another and do not count. Only the two particular meanings of “non-continuous” and “continuous” aspect united by the general meaning of “aspect” are revealed in this opposition or opposeme. The general meaning of this opposeme (“aspect”) manifests itself in the two particular meanings (“non-continuous aspect” and “continuous aspect”) of the opposite members (or opposites) [24; 22–24].

Thus, the elements which the opposition/opposeme is composed of are called opposites or members of the opposition. Opposites can be different: 1) non-marked, 2) marked. Compare the pair of noun forms table – tables. Together they create the “number” opposeme, where table represents the singular number expressed by a zero morpheme that is why it is called the non-marked member of the opposition, and tables – the plural number expressed by the positive morpheme -s is called the marked member of the opposition. Non-marked opposite is used more often than the marked opposite is. The marked opposite is peculiar by its limited use.

Ferdinand de Saussure claimed that everything in language is based on opposition. On phonetic level we have opposition of sounds. On all levels of the language we have opposition. Any grammatical form has got its contrast or counterpart. Together they make up a grammatical category.

A part of speech is characterized by its grammatical categories manifested in the opposemes (the elements of the opposition – оппозема, член опозиції) and paradigms of its lexemes. Nouns have the categories of number and case. Verbs possess the categories of tense, voice, mood etc. That is why paradigms belonging to different parts of speech are different. The paradigm of a verb lexeme is long: write, writes, wrote, will write, is writing etc. The paradigm of a noun lexeme is much shorter: sister, sister’s, sisters, sisters’. The paradigm of an adjective lexeme is still shorter: cold, colder, coldest. The paradigm of an adverb always consists only of one word.

Thus, the paradigm of a lexeme shows what part of speech the lexeme belongs to.

It must be borne in mind, however, that not all the lexemes of a part of speech have the same paradigms. Compare:

sister book information

sister’s books –

sisters – –

sisters’ – –

The first lexeme has opposemes of two grammatical categories: number and case. The second lexeme has only one opposeme – that of number. It has no case opposemes. The third lexeme is outside both categories: it has no opposemes at all. We may say that the number opposeme with its opposite grammatical meanings of “singularity” and “plurality” is neutralized in nouns like information, bread, milk etc. owing to their lexical meaning which can hardly be associated with “oneness” or “more-than-oneness”.

We may define neutralization as the reduction of an opposeme to one of its members under certain circumstances. This member may be called the member of neutralization. Usually it is the unmarked member of an opposeme.

The term grammatical category implies that:

1) there exist different morphological forms in the words of a part of speech possessing different referential meanings;

2) the oppositions of different forms possessing referential meanings are systematic that is they cover the whole class of words of that part of speech.

In other words a grammatical category is a systematic opposition of different morphological forms possessing different referential meanings. Each grammatical category is composed of at least two contrasting forms. Otherwise category would stop existing.

In general, an opposeme of any grammatical category consists of as many members (or opposites) as there are particular manifestations of the general meaning. Thus, a morphological opposeme is a minimum set of words revealing (by the difference in their forms) only (and all) the particular manifestations of some general grammatical meaning. Any morphological category is the system of such opposemes whose members differ in form to express only (and all) the particular manifestations of the general meaning of the category [24; 23–24].

Grammatical category unites in itself particular grammatical meanings. For example, the grammatical category of gender unites the meanings of the masculine, feminine, neuter and common genders in the Ukrainian language. Each grammatical category is connected, as a minimum, with two forms. For example, the grammatical category of number comprises the forms of singularity and plurality.

Grammatical meaning isan abstract meaning added to the lexical meaning of a word, expressing its relations other words or classes of words. As a rule, a word has several grammatical meanings. Grammatical meanings are realized in a grammatical word form.

Grammatical form of a word is the variety of the same word differing from other forms of this word by its grammatical meaning. For example, in the Ukrainian word-form батьку the ending -у expresses the grammatical meaning of the masculine gender, singular number, dative case.

Grammatical form of a word can be simple (synthetic), in which the grammatical meanings are formed by the ending, suffix, prefix or stress, etc. (дощ – дощ – дощем); or composite (analytical), created by adding several words (буду говорити, більш привабливий). The analytical-synthetic grammatical word form is a combination of two previous types of word forms. For example, в університеті (the local case is expressed by the flexion and the preposition); малював би, малювала б (the grammatical meaning of number and gender is expressed by the form of the main verb, and the meaning of the conditional mood – by the particle би) [2; 40–41].

|

Функция спроса населения на данный товар Функция спроса населения на данный товар: Qd=7-Р. Функция предложения: Qs= -5+2Р,где… |

Аальтернативная стоимость. Кривая производственных возможностей В экономике Буридании есть 100 ед. труда с производительностью 4 м ткани или 2 кг мяса… |

Вычисление основной дактилоскопической формулы Вычислением основной дактоформулы обычно занимается следователь. Для этого все десять пальцев разбиваются на пять пар… |

Расчетные и графические задания Равновесный объем — это объем, определяемый равенством спроса и предложения… |

Подборка по базе: Документ Microsoft Word (3).docx, Документ Microsoft Word (3).docx, Документ Microsoft Word (2).docx, Документ Microsoft Word.docx, Документ Microsoft Word (2).docx, Документ Microsoft Word (3).docx, Документ Microsoft Word (2).docx, Microsoft Word Document.docx, Документ Microsoft Word.docx, Документ Microsoft Word.docx

Семинар 6 Combinability. Word Groups

KEY TERMS

Syntagmatics — linear (simultaneous) relationship of words in speech as distinct from associative (non-simultaneous) relationship of words in language (paradigmatics). Syntagmatic relations specify the combination of elements into complex forms and sentences.

Distribution — The set of elements with which an item can cooccur

Combinability — the ability of linguistic elements to combine in speech.

Valency — the potential ability of words to occur with other words

Context — the semantically complete passage of written speech sufficient to establish the meaning of a given word (phrase).

Clichе´ — an overused expression that is considered trite, boring

Word combination — a combination of two or more notional words serving to express one concept. It is produced, not reproduced in speech.

Collocation — such a combination of words which conditions the realization of a certain meaning

TOPICS FOR DISCUSSION AND EXERCISES

1. Syntagmatic relations and the concept of combinability of words. Define combinability.

Syntagmatic relation defines the relationship between words that co-occur in the same sentence. It focuses on two main parts: how the position and the word order affect the meaning of a sentence.

The syntagmatic relation explains:

• The word position and order.

• The relationship between words gives a particular meaning to the sentence.

The syntagmatic relation can also explain why specific words are often paired together (collocations)

Syntagmatic relations are linear relations between words

The adjective yellow:

1. color: a yellow dress;

2. envious, suspicious: a yellow look;

3. corrupt: the yellow press

TYPES OF SEMANTIC RELATIONS

Because syntagmatic relations have to do with the relationship between words, the syntagms can result in collocations and idioms.

Collocations

Collocations are word combinations that frequently occur together.

Some examples of collocations:

- Verb + noun: do homework, take a risk, catch a cold.

- Noun + noun: office hours, interest group, kitchen cabinet.

- Adjective + adverb: good enough, close together, crystal clear.

- Verb + preposition: protect from, angry at, advantage of.

- Adverb + verb: strongly suggest, deeply sorry, highly successful.

- Adjective + noun: handsome man, quick shower, fast food.

Idioms

Idioms are expressions that have a meaning other than their literal one.

Idioms are distinct from collocations:

- The word combination is not interchangeable (fixed expressions).

- The meaning of each component is not equal to the meaning of the idiom

It is difficult to find the meaning of an idiom based on the definition of the words alone. For example, red herring. If you define the idiom word by word, it means ‘red fish’, not ‘something that misleads’, which is the real meaning.

Because of this, idioms can’t be translated to or from another language because the word definition isn’t equivalent to the idiom interpretation.

Some examples of popular idioms:

- Break a leg.

- Miss the boat.

- Call it a day.

- It’s raining cats and dogs.

- Kill two birds with one stone.

Combinability (occurrence-range) — the ability of linguistic elements to combine in speech.

The combinability of words is as a rule determined by their meanings, not their forms. Therefore not every sequence of words may be regarded as a combination of words.

In the sentence Frankly, father, I have been a fool neither frankly, father nor father, I … are combinations of words since their meanings are detached and do not unite them, which is marked orally by intonation and often graphically by punctuation marks.

On the other hand, some words may be inserted between the components of a word-combination without breaking it.

Compare,

a) read books

b) read many books

c) read very many books.

In case (a) the combination read books is uninterrupted.In cases (b) and (c) it is interrupted, or discontinuous(read… books).

The combinability of words depends on their lexical, grammatical and lexico-grammatical meanings. It is owing to the lexical meanings of the corresponding lexemes that the word wise can be combined with the words man, act, saying and is hardly combinable with the words milk, area, outline.

The lexico-grammatical meanings of -er in singer (a noun) and -ly in beautifully (an adverb) do not go together and prevent these words from forming a combination, whereas beautiful singer and sing beautifully are regular word-combinations.

The combination * students sings is impossible owing to the grammatical meanings of the corresponding grammemes.

Thus one may speak of lexical, grammatical and lexico-grammatical combinability, or the combinability of lexemes, grammemes and parts of speech.

The mechanism of combinability is very complicated. One has to take into consideration not only the combinability of homogeneous units, e. g. the words of one lexeme with those of another lexeme. A lexeme is often not combinable with a whole class of lexemes or with certain grammemes.

For instance, the lexeme few, fewer, fewest is not combinable with a class of nouns called uncountables, such as milk, information, hatred, etc., or with members of ‘singular’ grammemes (i. e. grammemes containing the meaning of ‘singularity’, such as book, table, man, boy, etc.).

The ‘possessive case’ grammemes are rarely combined with verbs, barring the gerund. Some words are regularly combined with sentences, others are not.

It is convenient to distinguish right-hand and left-hand connections. In the combination my hand (when written down) the word my has a right-hand connection with the word hand and the latter has a left-hand connection with the word my.

With analytical forms inside and outside connections are also possible. In the combination has often written the verb has an inside connection with the adverb and the latter has an outside connection with the verb.

It will also be expedient to distinguish unilateral, bilateral and multilateral connections. By way of illustration we may say that the articles in English have unilateral right-hand connections with nouns: a book, the child. Such linking words as prepositions, conjunctions, link-verbs, and modal verbs are characterized by bilateral connections: love of life, John and Mary, this is John, he must come. Most verbs may have zero

(Come!), unilateral (birds fly), bilateral (I saw him) and multilateral (Yesterday I saw him there) connections. In other words, the combinability of verbs is variable.

One should also distinguish direct and indirect connections. In the combination Look at John the connection between look and at, between at and John are direct, whereas the connection between look and John is indirect, through the preposition at.

2. Lexical and grammatical valency. Valency and collocability. Relationships between valency and collocability. Distribution.

The appearance of words in a certain syntagmatic succession with particular logical, semantic, morphological and syntactic relations is called collocability or valency.

Valency is viewed as an aptness or potential of a word to have relations with other words in language. Valency can be grammatical and lexical.

Collocability is an actual use of words in particular word-groups in communication.

The range of the Lexical valency of words is linguistically restricted by the inner structure of the English word-stock. Though the verbs ‘lift’ and ‘raise’ are synonyms, only ‘to raise’ is collocated with the noun ‘question’.

The lexical valency of correlated words in different languages is different, cf. English ‘pot plants’ vs. Russian ‘комнатные цветы’.

The interrelation of lexical valency and polysemy:

• the restrictions of lexical valency of words may manifest themselves in the lexical meanings of the polysemantic members of word-groups, e.g. heavy, adj. in the meaning ‘rich and difficult to digest’ is combined with the words food, meals, supper, etc., but one cannot say *heavy cheese or *heavy sausage;

• different meanings of a word may be described through its lexical valency, e.g. the different meanings of heavy, adj. may be described through the word-groups heavy weight / book / table; heavy snow / storm / rain; heavy drinker / eater; heavy sleep / disappointment / sorrow; heavy industry / tanks, and so on.

From this point of view word-groups may be regarded as the characteristic minimal lexical sets that operate as distinguishing clues for each of the multiple meanings of the word.

Grammatical valency is the aptness of a word to appear in specific grammatical (or rather syntactic) structures. Its range is delimited by the part of speech the word belongs to. This is not to imply that grammatical valency of words belonging to the same part of speech is necessarily identical, e.g.:

• the verbs suggest and propose can be followed by a noun (to propose or suggest a plan / a resolution); however, it is only propose that can be followed by the infinitive of a verb (to propose to do smth.);

• the adjectives clever and intelligent are seen to possess different grammatical valency as clever can be used in word-groups having the pattern: Adj. + Prep. at +Noun(clever at mathematics), whereas intelligent can never be found in exactly the same word-group pattern.

• The individual meanings of a polysemantic word may be described through its grammatical valency, e.g. keen + Nas in keen sight ‘sharp’; keen + on + Nas in keen on sports ‘fond of’; keen + V(inf)as in keen to know ‘eager’.

Lexical context determines lexically bound meaning; collocations with the polysemantic words are of primary importance, e.g. a dramatic change / increase / fall / improvement; dramatic events / scenery; dramatic society; a dramatic gesture.

In grammatical context the grammatical (syntactic) structure of the context serves to determine the meanings of a polysemantic word, e.g. 1) She will make a good teacher. 2) She will make some tea. 3) She will make him obey.

Distribution is understood as the whole complex of contexts in which the given lexical unit(word) can be used. Есть даже словари, по которым можно найти валентные слова для нужного нам слова — так и называются дистрибьюшн дикшенери

3. What is a word combination? Types of word combinations. Classifications of word-groups.

Word combination — a combination of two or more notional words serving to express one concept. It is produced, not reproduced in speech.

Types of word combinations:

- Semantically:

- free word groups (collocations) — a year ago, a girl of beauty, take lessons;

- set expressions (at last, point of view, take part).

- Morphologically (L.S. Barkhudarov):

- noun word combinations, e.g.: nice apples (BBC London Course);

- verb word combinations, e.g.: saw him (E. Blyton);

- adjective word combinations, e.g.: perfectly delightful (O. Wilde);

- adverb word combinations, e.g.: perfectly well (O, Wilde);

- pronoun word combinations, e.g.: something nice (BBC London Course).

- According to the number of the components:

- simple — the head and an adjunct, e.g.: told me (A. Ayckbourn)

- Complex, e.g.: terribly cold weather (O. Jespersen), where the adjunct cold is expanded by means of terribly.

Classifications of word-groups:

- through the order and arrangement of the components:

• a verbal — nominal group (to sew a dress);

• a verbal — prepositional — nominal group (look at something);

- by the criterion of distribution, which is the sum of contexts of the language unit usage:

• endocentric, i.e. having one central member functionally equivalent to the whole word-group (blue sky);

• exocentric, i.e. having no central member (become older, side by side);

- according to the headword:

• nominal (beautiful garden);

• verbal (to fly high);

• adjectival (lucky from birth);

- according to the syntactic pattern:

• predicative (Russian linguists do not consider them to be word-groups);

• non-predicative — according to the type of syntactic relations between the components:

(a) subordinative (modern technology);

(b) coordinative (husband and wife).

4. What is “a free word combination”? To what extent is what we call a free word combination actually free? What are the restrictions imposed on it?

A free word combination is a combination in which any element can be substituted by another.

The general meaning of an ordinary free word combination is derived from the conjoined meanings of its elements

Ex. To come to one’s sense –to change one’s mind;

To fall into a rage – to get angry.

Free word-combinations are word-groups that have a greater semantic and structural independence and freely composed by the speaker in his speech according to his purpose.

A free word combination or a free phrase permits substitution of any of its elements without any semantic change in the other components.

5. Clichе´s (traditional word combinations).

A cliché is an expression that is trite, worn-out, and overused. As a result, clichés have lost their original vitality, freshness, and significance in expressing meaning. A cliché is a phrase or idea that has become a “universal” device to describe abstract concepts such as time (Better Late Than Never), anger (madder than a wet hen), love (love is blind), and even hope (Tomorrow is Another Day). However, such expressions are too commonplace and unoriginal to leave any significant impression.

Of course, any expression that has become a cliché was original and innovative at one time. However, overuse of such an expression results in a loss of novelty, significance, and even original meaning. For example, the proverbial phrase “when it rains it pours” indicates the idea that difficult or inconvenient circumstances closely follow each other or take place all at the same time. This phrase originally referred to a weather pattern in which a dry spell would be followed by heavy, prolonged rain. However, the original meaning is distanced from the overuse of the phrase, making it a cliché.

Some common examples of cliché in everyday speech:

- My dog is dumb as a doorknob. (тупой как пробка)

- The laundry came out as fresh as a daisy.

- If you hide the toy it will be out of sight, out of mind. (с глаз долой, из сердца вон)

Examples of Movie Lines that Have Become Cliché:

- Luke, I am your father. (Star Wars: The Empire Strikes Back)

- i am Groot. (Guardians of the Galaxy)

- I’ll be back. (The Terminator)

- Houston, we have a problem. (Apollo 13)

Some famous examples of cliché in creative writing:

- It was a dark and stormy night

- Once upon a time

- There I was

- All’s well that ends well

- They lived happily ever after

6. The sociolinguistic aspect of word combinations.

Lexical valency is the possibility of lexicosemantic connections of a word with other word

Some researchers suggested that the functioning of a word in speech is determined by the environment in which it occurs, by its grammatical peculiarities (part of speech it belongs to, categories, functions in the sentence, etc.), and by the type and character of meaning included into the semantic structure of a word.

Words are used in certain lexical contexts, i.e. in combinations with other words. The words that surround a particular word in a sentence or paragraph are called the verbal context of that word.

7. Norms of lexical valency and collocability in different languages.

The aptness of a word to appear in various combinations is described as its lexical valency or collocability. The lexical valency of correlated words in different languages is not identical. This is only natural since every language has its syntagmatic norms and patterns of lexical valency. Words, habitually collocated, tend to constitute a cliché, e.g. bad mistake, high hopes, heavy sea (rain, snow), etc. The translator is obliged to seek similar cliches, traditional collocations in the target-language: грубая ошибка, большие надежды, бурное море, сильный дождь /снег/.

The key word in such collocations is usually preserved but the collocated one is rendered by a word of a somewhat different referential meaning in accordance with the valency norms of the target-language:

- trains run — поезда ходят;

- a fly stands on the ceiling — на потолке сидит муха;

- It was the worst earthquake on the African continent (D.W.) — Это было самое сильное землетрясение в Африке.

- Labour Party pretest followed sharply on the Tory deal with Spain (M.S.1973) — За сообщением о сделке консервативного правительства с Испанией немедленно последовал протест лейбористской партии.

Different collocability often calls for lexical and grammatical transformations in translation though each component of the collocation may have its equivalent in Russian, e.g. the collocation «the most controversial Prime Minister» cannot be translated as «самый противоречивый премьер-министр».

«Britain will tomorrow be welcoming on an official visit one of the most controversial and youngest Prime Ministers in Europe» (The Times, 1970). «Завтра в Англию прибывает с официальным визитом один из самых молодых премьер-министров Европы, который вызывает самые противоречивые мнения».

«Sweden’s neutral faith ought not to be in doubt» (Ib.) «Верность Швеции нейтралитету не подлежит сомнению».

The collocation «documentary bombshell» is rather uncommon and individual, but evidently it does not violate English collocational patterns, while the corresponding Russian collocation — документальная бомба — impossible. Therefore its translation requires a number of transformations:

«A teacher who leaves a documentary bombshell lying around by negligence is as culpable as the top civil servant who leaves his classified secrets in a taxi» (The Daily Mirror, 1950) «Преподаватель, по небрежности оставивший на столе бумаги, которые могут вызвать большой скандал, не менее виновен, чем ответственный государственный служащий, забывший секретные документы в такси».

8. Using the data of various dictionaries compare the grammatical valency of the words worth and worthy; ensure, insure, assure; observance and observation; go and walk; influence and влияние; hold and держать.

| Worth & Worthy | |

| Worth is used to say that something has a value:

• Something that is worth a certain amount of money has that value; • Something that is worth doing or worth an effort, a visit, etc. is so attractive or rewarding that the effort etc. should be made. Valency:

|

Worthy:

• If someone or something is worthv of something, they deserve it because they have the qualities required; • If you say that a person is worthy of another person you are saying that you approve of them as a partner for that person. Valency:

|

| Ensure, insure, assure | ||

| Ensure means ‘make certain that something happens’.

Valency:

|

Insure — make sure

Valency:

|

Assure:

• to tell someone confidently that something is true, especially so that they do not worry; • to cause something to be certain. Valency:

|

| Observance & Observation | |

| Observance:

• the act of obeying a law or following a religious custom: religious observances such as fasting • a ceremony or action to celebrate a holiday or a religious or other important event: [ C ] Memorial Day observances [ U ] Financial markets will be closed Monday in observance of Labor Day. |

Observation:

• the act of observing something or someone; • the fact that you notice or see something; • a remark about something that you have noticed. Valency:

|

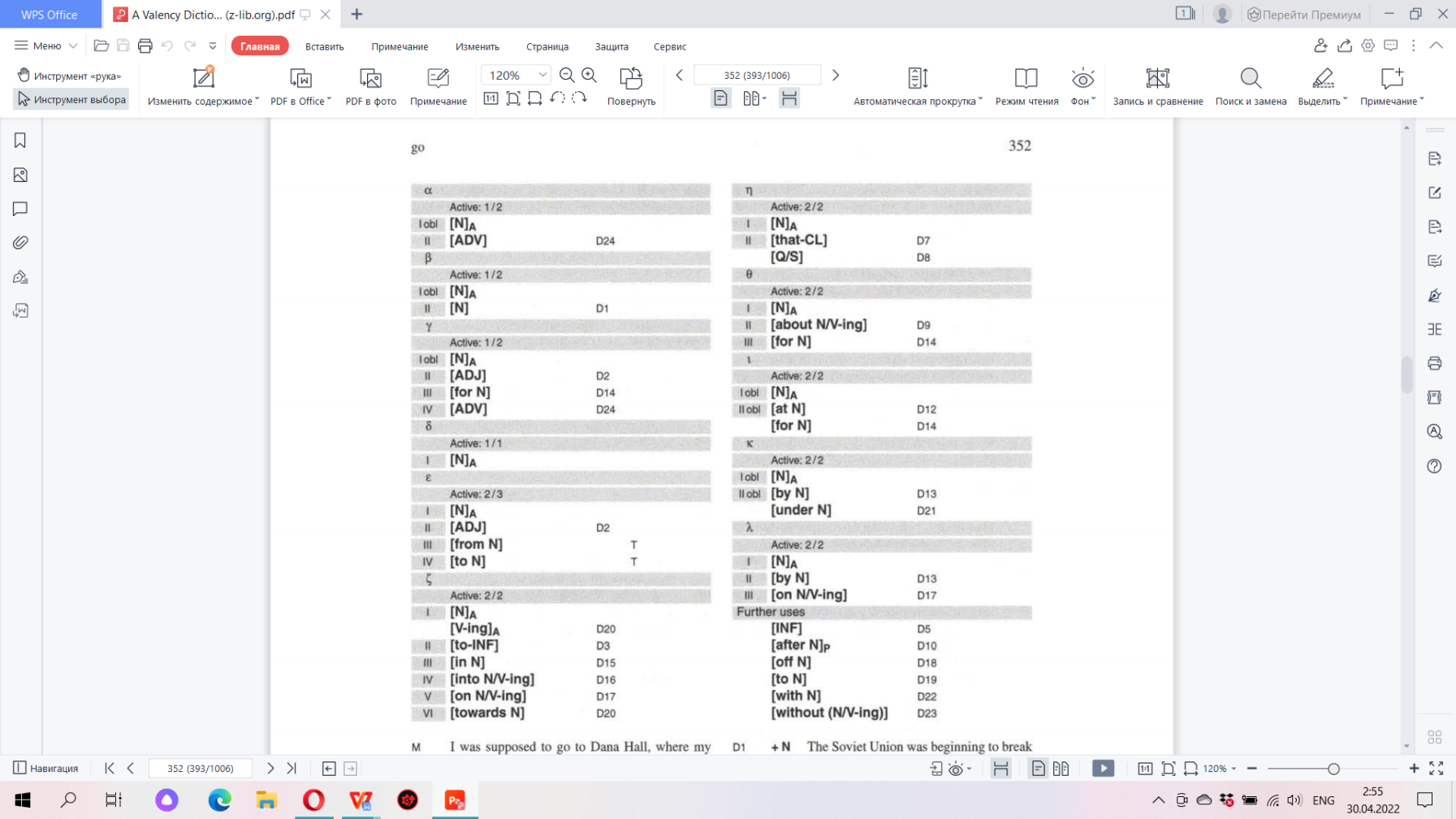

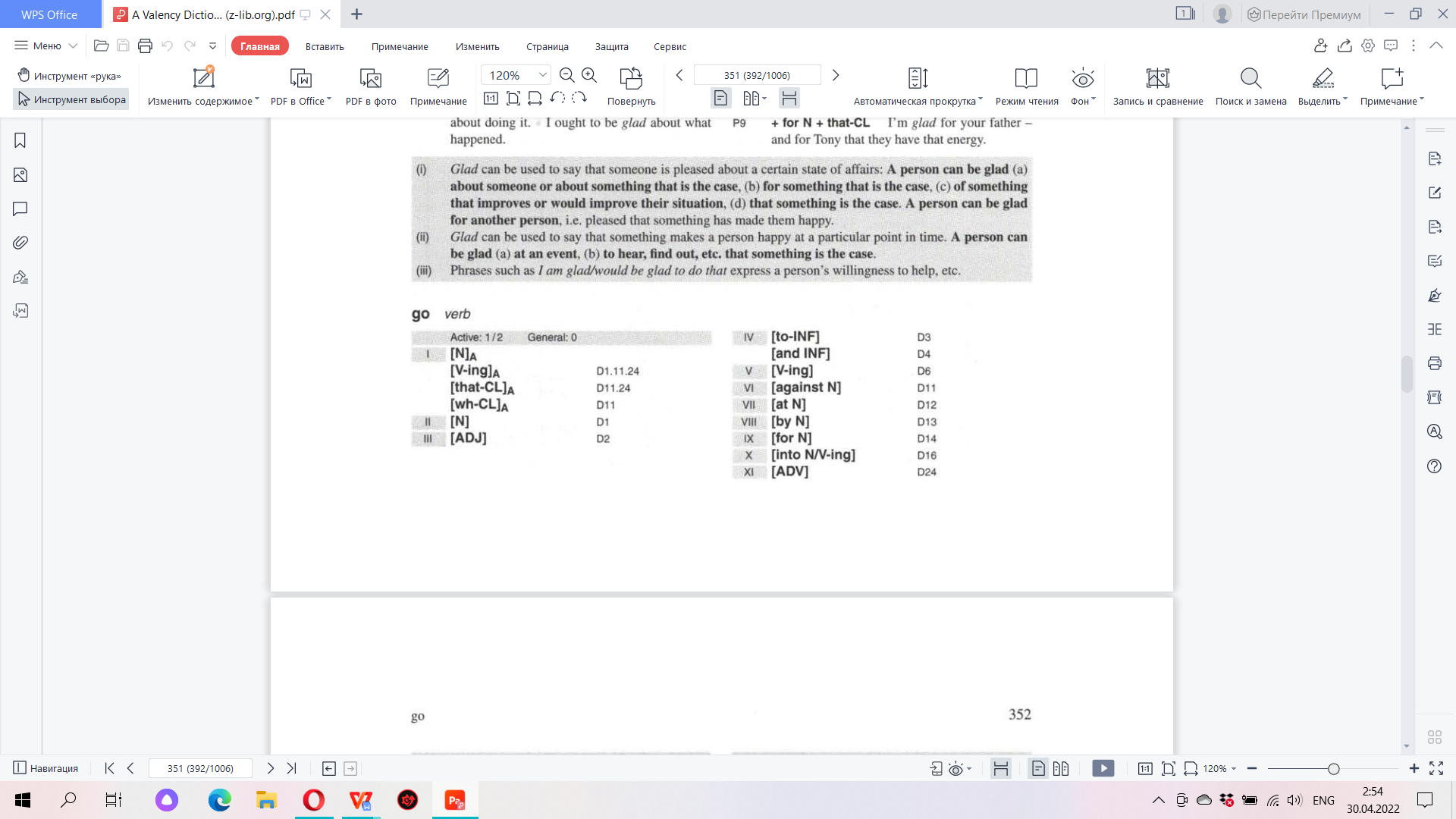

| Go & Walk | |

|

Walk can mean ‘move along on foot’:

• A person can walk an animal, i.e. exercise them by walking. • A person can walk another person somewhere , i.e. take them there, • A person can walk a particular distance or walk the streets. Valency:

|

| Influence & Влияние | |

| Influence:

• A person can have influence (a) over another person or a group, i.e. be able to directly guide the way they behave, (b) with a person, i.e. be able to influence them because they know them well. • Someone or something can have or be an influence on or upon something or someone, i.e. be able to affect their character or behaviour in some way Valency:

|

Влияние — Действие, оказываемое кем-, чем-либо на кого-, что-либо.

Сочетаемость:

|

| Hold & Держать | |

| Hold:

• to take and keep something in your hand or arms; • to support something; • to contain or be able to contain something; • to keep someone in a place so that they cannot leave. Valency:

|

Держать — взять в руки/рот/зубы и т.д. и не давать выпасть

Сочетаемость:

|

- Contrastive Analysis. Give words of the same root in Russian; compare their valency:

| Chance | Шанс |

|

|

| Situation | Ситуация |

|

|

| Partner | Партнёр |

|

|

| Surprise | Сюрприз |

|

|

| Risk | Риск |

|

|

| Instruction | Инструкция |

|

|

| Satisfaction | Сатисфакция |

|

|

| Business | Бизнес |

|

|

| Manager | Менеджер |

|

|

| Challenge | Челлендж |

|

|

10. From the lexemes in brackets choose the correct one to go with each of the synonyms given below:

- acute, keen, sharp (knife, mind, sight):

• acute mind;

• keen sight;

• sharp knife;

- abysmal, deep, profound (ignorance, river, sleep);

• abysmal ignorance;

• deep river;

• profound sleep;

- unconditional, unqualified (success, surrender):

• unconditional surrender;

• unqualified success;

- diminutive, miniature, petite, petty, small, tiny (camera, house, speck, spite, suffix, woman):

• diminutive suffix;

• miniature camera/house;

• petite woman;

• petty spite;

• small speck/camera/house;

• tiny house/camera/speck;

- brisk, nimble, quick, swift (mind, revenge, train, walk):

• brisk walk;

• nimble mind;

• quick train;

• swift revenge.

11. Collocate deletion: One word in each group does not make a strong word partnership with the word on Capitals. Which one is Odd One Out?

1) BRIGHT idea green

smell

child day room

2) CLEAR

attitude

need instruction alternative day conscience

3) LIGHT traffic

work

day entertainment suitcase rain green lunch

4) NEW experience job

food

potatoes baby situation year

5) HIGH season price opinion spirits

house

time priority

6) MAIN point reason effect entrance

speed

road meal course

7) STRONG possibility doubt smell influence

views

coffee language

advantage

situation relationship illness crime matter

- Write a short definition based on the clues you find in context for the italicized words in the sentence. Check your definitions with the dictionary.

| Sentence | Meaning |

| The method of reasoning from the particular to the general — the inductive method — has played an important role in science since the time of Francis Bacon. | The way of learning or investigating from the particular to the general that played an important role in the time of Francis Bacon |

| Most snakes are meat eaters, or carnivores. | Animals whose main diet is meat |

| A person on a reducing diet is expected to eschew most fatty or greasy foods. | deliberately avoid |

| After a hectic year in the city, he was glad to return to the peace and quiet of the country. | full of incessant or frantic activity. |

| Darius was speaking so quickly and waving his arms around so wildly, it was impossible to comprehend what he was trying to say. | grasp mentally; understand.to perceive |

| The babysitter tried rocking, feeding, chanting, and burping the crying baby, but nothing would appease him. | to calm down someone |

| It behooves young ladies and gentlemen not to use bad language unless they are very, very angry. | necessary |

| The Academy Award is an honor coveted by most Hollywood actors. | The dream about some achievements |

| In the George Orwell book 1984, the people’s lives are ruled by an omnipotent dictator named “Big Brother.” | The person who have a lot of power |

| After a good deal of coaxing, the father finally acceded to his children’s request. | to Agree with some request |

| He is devoid of human feelings. | Someone have the lack of something |

| This year, my garden yielded several baskets full of tomatoes. | produce or provide |

| It is important for a teacher to develop a rapport with his or her students. | good relationship |

|

License Agreement on scientific materials use. |

||

| Vlavatskaya Marina Vital’evna Novosibirsk State Technical University |

||

|

Abstract. The article is devoted to investigating the norm of combinability of words and its violation. In this aspect the basic principle for distinguishing word combinations is the following one: «norm — acceptability — substandard». To the normative we refer codified word combinations fixed in the authoritative lexicographical guides and usually used basically in the mass media and journalism. To the acceptable we should refer occasional word combinations being an original creation of an author. Communicative failures conditioned by incompetence in combinability of words can be classified as substandard word combinations. |

||

|

Key words and phrases: сочетаемость слов, нормативные словосочетания, кодифицированные словосочетания, узуальные словосочетания, окказиональные словосочетания, нарушение сочетаемости слов, речевые ошибки, combinability of words, normative word combinations, codified word combinations, usual word combinations, occasional word combinations, violation of combinability of words, communicative failures |

||

|

||

References:

|