If

we describe a wоrd

as an autonomous unit of language in which a

particular meaning is associated with a particular sound complex and

which is capable of a particular grammatical employment and able to

form a sentence by itself (see p. 9),

we

have the possibility to distinguish it from the other fundamental

language unit, namely, the morpheme.

A

morpheme is

also an association of a given meaning with a given sound pattern.

But unlike a word it is not autonomous. Morphemes occur in speech

only as constituent parts of words, not independently, although a

word may consist of a single morpheme. Nor are they divisible into

smaller meaningful units. That is why the morpheme may be defined as

the minimum meaningful language unit.

The

term morpheme

is derived from Gr morphe

‘form’

+

-eme.

The

Greek suffix -erne

has

been adopted by linguists to denote the smallest significant or

distinctive

unit.

(Cf. phoneme,

sememe.) The

morpheme is the smallest meaningful unit of form. A form in these

cases is a recurring discrete unit of speech.

A

form is said to be free if it may stand alone without changing its

meaning;

if not, it is a bound

form, so called because it is always bound

to something else. For example, if we compare the words sportive

and

elegant

and

their parts, we see that sport,

sportive, elegant may

occur alone as utterances, whereas eleg-,

-ive, -ant are

bound forms because they never occur alone. A word is, by L.

Bloomfield’s definition, a minimum free form. A morpheme is said to

be either bound or free. This statement should bе

taken

with caution. It means that some morphemes are capable of forming

words without adding other morphemes: that is, they are homonymous to

free forms.

According

to the role they play in constructing words, morphemes are subdivided

into roots

and affixes.

The latter are further subdivided, according to their position, into

prefixes,

suffixes

and

infixes,

and according to their function and meaning, into derivational

and functional

.affixes,

the latter also called endings

or outer

formatives.

When

a derivational or functional affix is stripped from the word, what

remains is a stem

(or astern base).

The stem expresses the lexical and the part of speech meaning. For

the word hearty

and

for the paradigm heart

(sing.)

—hearts

(pi.)1

the stem may be represented as heart-.

This

stem is a single morpheme, it contains nothing but the root, so it is

a simple

stem.

It is also a

free

stem

because it is homonymous to the word heart.

A

stem

may also be defined as the part of the word that remains unchanged

throughout its paradigm. The stem of the paradigm hearty

—

heartier

—

(the)

heartiest

is

hearty-.

It

is a free stem, but as it consists of a root morpheme and an affix,

it is not simple but derived. Thus, a stem containing one or more

affixes is

a derived

stem.

If after deducing the affix the remaining stem is not homonymous to a

separate word of the same root, we call it abound

stem.

Thus, in the word cordial

‘proceeding

as if from the heart’, the adjective-forming suffix can be

separated on the analogy with such words as bronchial,

radial, social. The

remaining stem, however, cannot form a separate word by itself, it is

bound. In cordially

and

cordiality,

on

the other hand, the derived stems are free.

Bound

stems are especially characteristic of loan words. The point may

be illustrated by the following French borrowings: arrogance,

charity,

courage, coward, distort, involve, notion, legible and

tolerable,

to

give but a few.2

After the affixes of these words are taken away the remaining

elements are: arrog-,

char-, cour-, cow-, -tort, -volve, not-, leg-, toler-, which

do not coincide with any semantically related independent words.

Roots

are main morphemic vehicles of a given idea in a given language at a

given stage of its development. A root may be also regarded as the

ultimate constituent element which remains after the removal of all

functional and derivational affixes and does not admit any further

analysis.

It is the common element of words within a word-family.

Thus,

-heart-

is

the common root of the following series of words: heart,

hearten,

dishearten, heartily, heartless, hearty, heartiness, sweetheart,

heart-broken, kind-hearted, whole-heartedly, etc.

In some of these, as, for example,

in hearten,

there

is only one root; in others the root -heart

is

combined with some other root, thus forming a compound like

sweetheart.

The

root word heart

is

unsegmentable, it is non-motivated morphologically. The morphemic

structure of all the other words in this word-family is obvious —

they

are segmentable as consisting of at least two distinct morphemes.

They may be further subdivided into: 1)

those

formed by affixation or

affixational

derivatives

consisting of a root morpheme and one or more affixes: hearten,

dishearten, heartily, heartless,

hearty, heartiness; 2)

compounds,

in which two, or very rarely

more, stems simple or derived are combined into a lexical unit:

sweetheart,

heart-shaped, heart-broken or3)

derivational

compounds

where words of a phrase are joined together by composition and

affixation: kind-hearted.

This

last process is also called phrasal derivation

((kind

heart) + -ed)).

There

exist word-families with several tmsegmentable members, the

derived elements being formed by conversion or clipping. The

word-family

with the noun father

as its centre

contains alongside affixational derivatives fatherhood,

fatherless, fatherly a

verb father

‘to

adopt’ or ‘to originate’ formed by conversion.

We

shall now present the different types of morphemes starting with the

root.

It

will at once be noticed that the root in English is very often

homonymous

with the word. This fact is of fundamental importance as it is

one of the most specific features of the English language arising

from its general grammatical system on the one hand, and from its

phonemic system on the other. The influence of the analytical

structure of the language

is obvious. The second point, however, calls for some explanation.

Actually

the usual phonemic shape most favoured in English is one single

stressed syllable: bear,

find, jump, land, man, sing, etc.

This does not

give much space for a second morpheme to add classifying

lexico-grammatical

meaning to the lexical meaning already present in the root-stem,

so the lexico-grammatical meaning must be signalled by distribution.

In

the phrases a

morning’s drive, a morning’s ride, a morning’s walk the

words drive,

ride and

walk

receive

the lexico-grammatical meaning of a noun not due to the structure of

their stems, but because they are preceded by a genitive.

An

English word does not necessarily contain formatives indicating to

what part of speech it belongs. This holds true even with respect to

inflectable

parts of speech, i.e. nouns, verbs, adjectives. Not all roots are

free forms, but productive

roots,

i.e. roots capable of producing

new words, usually are. The semantic realisation of an English word

is therefore very specific. Its dependence on context is further

enhanced

by the widespread occurrence of homonymy both among root morphemes

and affixes. Note how many words in the following statement

might be ambiguous if taken in isolation: A

change of work is as good

as a rest.

The

above treatment of the root is purely synchronic, as we have taken

into consideration only the facts of present-day English. But the

same

problem of the morpheme serving as the main signal of a given lexical

meaning is studied in etymology.

Thus, when approached historically

or diachronically the word heart

will

be classified as Common Germanic.

One will look for cognates,

i.e. words descended from a

common ancestor. The cognates of heart

are

the Latin cor,

whence

cordial

‘hearty’,

‘sincere’, and so cordially

and

cordiality,

also

the Greek kardia,

whence

English cardiac

condition. The

cognates outside the English

vocabulary are the Russian cepдце,

the

German Herz,

the

Spanish corazon

and

other words.

To

emphasise the difference between the synchronic and the diachronic

treatment, we shall call the common element of cognate words in

different

languages not their root but their radical

element. These

two types of approach, synchronic and diachronic, give rise to two

different principles of arranging morphologically related words into

groups. In the first case series of words with a common root morpheme

in which derivatives are opposable to their unsuffixed and unprefixed

bases, are combined, сf.

heart,

hearty, etc.

The second grouping results in families of historically cognate

words, сf.

heart,

cor (Lat),

Herz

(Germ),

etc.

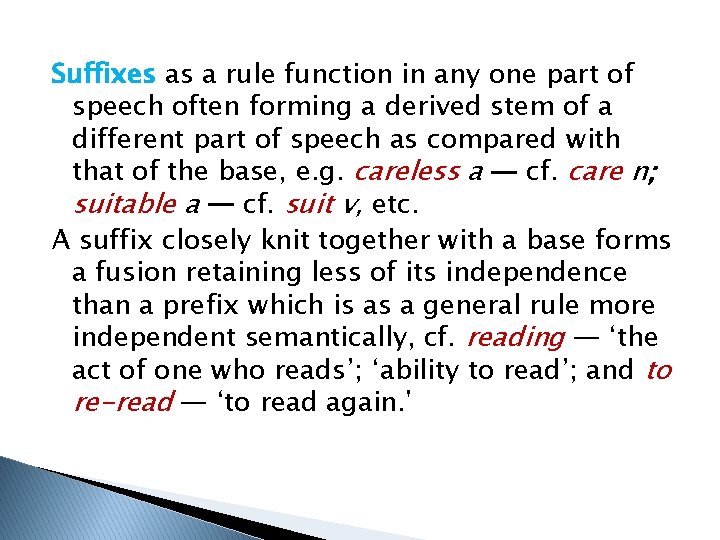

Unlike

roots, affixes are always bound forms. The difference between

suffixes and prefixes, it will be remembered, is not confined to

their respective position, suffixes being “fixed after” and

prefixes “fixed before” the stem. It also concerns their function

and meaning.

A

suffix

is

a derivational morpheme following the stem and forming a new

derivative in a different part of speech or a different word class,

сf.

-en,

-y, -less in

hearten,

hearty, heartless. When

both the underlying and the resultant forms belong to the same part

of speech, the suffix serves to differentiate between

lexico-grammatical classes by rendering some very general

lexico-grammatical meaning. For instance, both -ify

and

-er

are

verb suffixes, but the first characterises causative verbs, such as

horrify,

purify, rarefy, simplify, whereas

the second is mostly typical of frequentative verbs: flicker,

shimmer, twitter and

the like.

If we realise that suffixes

render the most general semantic component of the word’s lexical

meaning by marking the general class of phenomena to which the

referent of the word belongs, the reason why suffixes are as a rule

semantically fused with the stem stands explained.

A

prefix

is a derivational morpheme standing before the root and modifying

meaning, cf.

hearten

—

dishearten.

It

is only with verbs and statives that a prefix may serve to

distinguish one part of speech from another, like in earth

n

—

unearth

v,

sleep

n

—

asleep

(stative).

It

is interesting that as a prefix en-

may

carry the same meaning of being or bringing into a certain state as

the suffix -en,

сf.

enable,

encamp, endanger,

endear, enslave and

fasten,

darken, deepen, lengthen, strengthen.

Preceding

a verb stem, some prefixes express the difference between a

transitive and an intransitive verb: stay

v

and outstay

(sb)

vt. With a few exceptions prefixes modify the stem for time (pre-,

post-), place

(in-,

ad-) or

negation (un-,

dis-) and

remain semantically rather independent of the stem.

An

infix

is an affix placed within the word, like -n-

in

stand.

The

type is not productive.

An

affix should not be confused with a

combining

form.

A

combining form is also a bound form but it can be distinguished from

an affix historically by the fact that it is always borrowed from

another language, namely, from Latin or Greek, in which it existed as

a free form, i.e. a separate word, or also as a combining form.

DERIVATIONAL AND

FUNCTIONAL AFFIXES

Lexicology

is primarily concerned with derivational

affixes,

the other group being the domain of grammarians. The derivational

affixes in fact, as well as the whole problem of word-formation, form

a boundary area between lexicology and grammar and are therefore

studied in both.

Language being a system in

which the elements of vocabulary and grammar are closely

interrelated, our study of affixes cannot be complete without some

discussion of the similarity and difference between derivational and

functional morphemes.

The

similarity is obvious as they are so often homonymous (for the most

important cases of homonymy between derivational and functional

affixes see p. 18).

Otherwise

the two groups are essentially different because they render

different types of meaning.

Functional

affixes serve to convey grammatical meaning. They build different

forms of one and the same word. A word

form,

or

the form of a word, is defined as one of the different aspects a word

may take as a result of inflection. Complete sets of all the various

forms of

a word when considered as inflectional patterns, such as declensions

or conjugations, are termed paradigms. A paradigm

has been defined in grammar as the system of grammatical forms

characteristic of a word, e. g. near,

nearer, nearest; son, son’s, sons, sons’ (see1

p. 23).

Derivational

affixes serve to supply the stem with components of lexical and

lexico-grammatical meaning, and thus form4different

words. One and the same lexico-grammatical meaning of the affix is

sometimes accompanied by different combinations of various lexical

meanings. Thus, the lexico-grammatical meaning supplied by the suffix

-y

consists

in the ability to express the qualitative idea peculiar to adjectives

and creates adjectives from noun stems. The lexical meanings of the

same suffix are somewhat variegated: ‘full of, as in bushy

or

cloudy,

‘composed

of, as in stony,

‘having

the quality of, as in slangy,

‘resembling’,

as in baggy,

‘covered

with’, as in hairy

and

some more. This suffix sometimes conveys emotional components of

meaning. E.g.: My

school reports used to say: “Not amenable to discipline; too fond

of organising,”

which was only a kind way of saying: “Bossy.” (M.

Dickens) Bossy

not

only means ‘having the quality of a boss’ or ‘behaving like a

boss’; it is also a derogatory word.

This fundamental difference in

meaning and function of the two groups of affixes results in an

interesting relationship: the presence of a derivational affix does

not prevent a word from being equivalent to another word, in which

this suffix is absent, so that they can be substituted for one

another in context. The presence of a functional affix changes the

distributional properties of a word so much that it can never be

substituted for a simple word without violating grammatical standard.

To see this point consider the following familiar quotation from

Shakespeare:

Cowards

die many times before their deaths; The

valiant never taste of death but once.

Here

no one-morpheme word can be substituted for the words cowards,

times or

deaths

because

the absence of a plural mark will make the sentence ungrammatical.

The words containing derivational affixes can be substituted by

morphologically different words, so that the derivative valiant

can

be substituted by a root word like brave.

In

a statement like

I

wash

my hands of the whole affair (Du

Maurier) the word affair

may

be replaced by the derivative business

or

by the simple word thing

because

their distributional properties are the same. It is, however,

impossible to replace it by a word containing a functional affix

(affairs

or

things),

as

this would require a change in the rest of the sentence.

The

American structuralists B. Bloch and G. Trager formulate this point

as follows: “A suffixal derivative is a two-morpheme word which is

grammatically equivalent to (can be substituted for) any simple word

in all the constructions where it occurs.»1

This

rule is not to be taken as an absolutely rigid one because the word

building potential and productivity of stems depend on several

factors. Thus, no further addition of suffixes is possible after

-ness,

-ity, -dom, -ship and

-hood.

A

derivative is mostly capable of further derivation and is therefore

homonymous to a stem. Foolish,

for

instance, is derived from the stem fool-

and

is homonymous to the stem foolish-

occurring

in the words foolishness

and

foolishly.

Inflected

words cease to be homonymous to stems. No further derivation is

possible from the word form fools,

where

the stem fool-

is

followed by the functional affix -s.

Inflected

words are neither structurally nor functionally equivalent to the

morphologically simple words belonging to the same part of speech.

Things

is

different from business

functionally,

because these two words cannot occur in identical contexts, and

structurally, because of the different character of their immediate

constituents and different word-forming possibilities. After having

devoted special attention to the difference in semantic

characteristics of various kinds of morphemes we notice that they are

different positionally. A functional affix marks the word boundary,

it can only follow the affix of derivation and come last, so that no

further derivation is possible for a stem to which a functional affix

is added. That is why functional affixes are called by E. Nida the

outer

formatives

as contrasted to the inner

formatives

which is equivalent to our term derivational

affixes.

It

might be argued that the outer position of functional affixes is

disproved by such examples as the

disableds, the unwanteds. It

must be noted, however, that in these words -ed

is

not a functional affix, it receives derivational force so that the

disableds is

not a form of the verb to

disable, but

a new word —

a

collective noun.

A word containing no outer

formatives is, so to say, open, because it is homonymous to a stem

and further derivational affixes may be added to it. Once we add an

outer formative, no further derivation is possible. The form may be

regarded as closed.

The

semantic, functional and positional difference that has already been

stated is supported by statistical properties and difference in

valency (combining possibilities). Of the three main types of

morphemes, namely roots, derivational affixes and functional affixes

(formatives), the roots are by far the most numerous. There are many

thousand roots in the English language; the derivational affixes,

when listed, do not go beyond a few scores. The list given in

“Chambers’s Twentieth Century Dictionary” takes up five pages

and a half, comprising all the detailed explanations of their origin

and meaning, and even then the actual living suffixes are much fewer.

As to the functional affixes there are hardly more than ten of them.

Regular English verbs, for instance, have only four forms: play,

plays, played, playing, as

compared to the German verbs

which have as many as sixteen.

The

valency of these three groups of morphemes is naturally in inverse

proportion to their number. Functional affixes can be appended,

with a few exceptions, to any element belonging to the part

of speech they serve. The regular correlation of singular and plural

forms of nouns can serve to illustrate this point. Thus, heart

: : hearts; boy :

: boys,

etc.

The relics of archaic forms, such as child

:

: children,

or

foreign plurals like criterion

:

: criteria

are

very few in comparison with these.

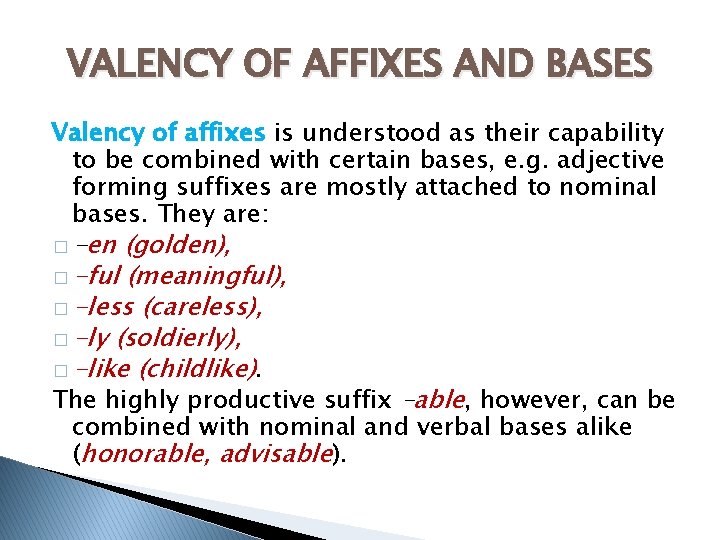

Derivational

affixes do not combine so freely and regularly. The suffix -en

occurring

in golden

and

leaden

cannot

be added to the root steel-.

Nevertheless,

as they serve to mark certain groups of words, their correlations are

never isolated and always contain more than two oppositions,

e. g. boy

:

: boyish,

child :

: childish,

book :

: bookish,

gold :

: golden,

lead :

: leaden,

wood :

: wooden.

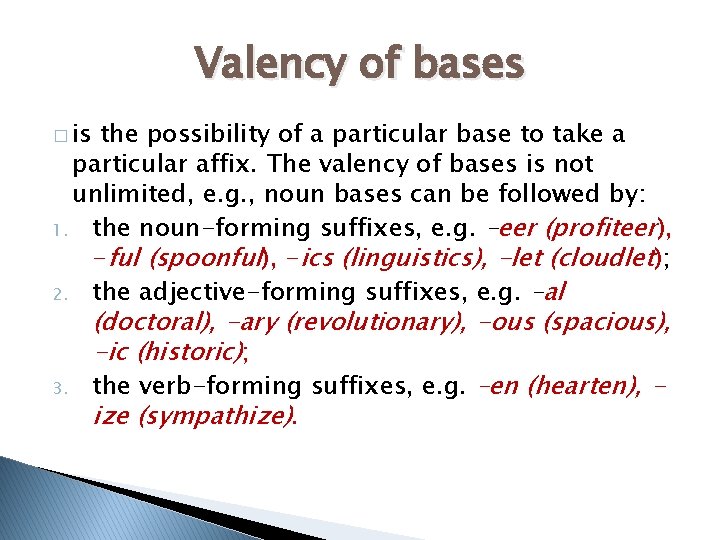

The

valency of roots is of a very different order and the oppositions may

be sometimes isolated. It is for instance difficult to find another

pair with the root heart

and

the same relationship as in heart

:

: sweetheart.

Knowing

the plural functional suffix -s

we

know how the countable nouns are inflected. The probability of a

mistake is not great.

With

derivational affixes the situation is much more intricate. Knowing,

for instance, the complete list of affixes of feminisation, i.e.

formation of feminine nouns from the stems of masculine ones by

adding a characteristic suffix, we shall be able to recognise a new

word if we know the root. This knowledge, however, will not enable us

to construct words acceptable for English vocabulary, because

derivational affixes are attached to their particular stems in a

haphazard and unpredictable manner.

Why, for instance, is it impossible to call a lady-guest —

a

guestess on

the

pattern of host

:

: hostess?

Note

also: lion

:

: lioness,

tiger :

: tigress,

but

bear

:

: she-bear,

elephant :

: she-elephant,

wolf :

: she-wolf;

very

often the

correlation is assured by suppletion, therefore we have boar

:

: sow,

buck :

: doe,

bull :

: cow,

cock :

: hen,

ram :

: ewe.

Similarly

in toponymy: the inhabitant of London is called a

Londoner, the

inhabitant of Moscow is a

Muscovite, of

Vienna —

a

Viennese, of

Athens —

an

Athenian.

On

the whole this state of things is more or less common to many

languages; but English has stricter constraints in this respect than,

for example, Russian; indeed the range of possibilities in English is

very narrow. Russian not only possesses a greater number of

diminutive affixes but can add many of them to the same stem:

мальчик,

мальчишка,

мальчишечка,

мальчонка,

мальчуган,

мальчугашка.

Nothing

of the kind is

possible for the English noun stem boy.

With

the noun stem girl

the

diminutive -ie

can

be added but not -ette,

-let, -kin / -kins. The

same holds true even if the corresponding noun stems have much in

common: a short lecture is a

lecturette but

a small picture is never called a

picturette. The

probability that a given stem will combine with a given affix is thus

not easily established.

To sum up: derivational and

functional morphemes may happen to be identical in sound form, but

they are substantially different in meaning, function, valency,

statistical characteristics and structural properties.

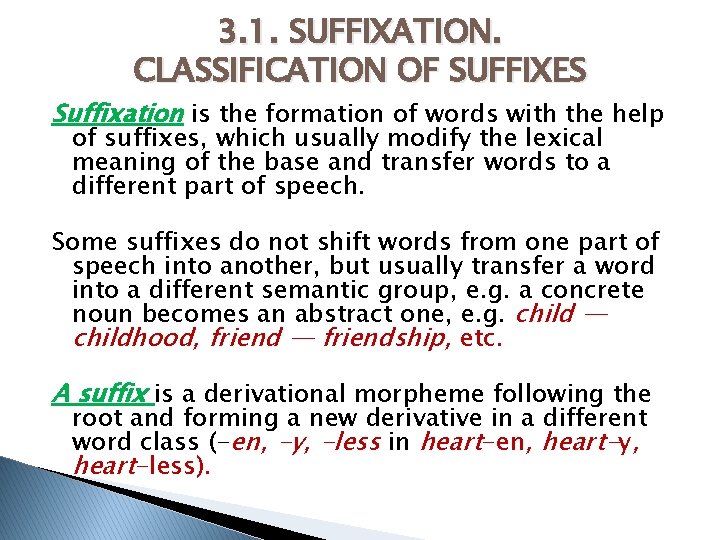

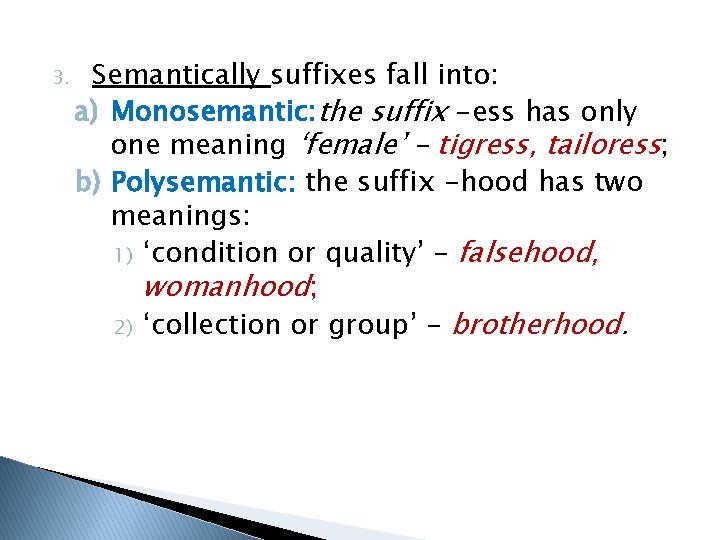

CLASSIFICATION OF AFFIXES

Depending on the purpose of

research, various classifications of suffixes have been used and

suggested. Suffixes have been classified according to their origin,

parts of speech they served to form, their frequency, productivity

and other characteristics.

Within the parts of speech

suffixes have been classified semantically according to

lexico-grammatical groups and semantic fields, and last but not

least, according to the types of stems they are added to.

In

conformity with our primarily synchronic approach it seems convenient

to begin with the classification according to the part of speech in

which the most frequent suffixes of present-day English occur. They

will be listed together with words illustrating their possible

semantic force.1

Noun-forming

suffixes:

-age

(bondage,

breakage, mileage, vicarage); -ance/-ence2

(assistance,

reference); -ant/-ent

(disinfectant,

student); -dom

(kingdom,

freedom, officialdom);

—ее

(employee);

-eer

(profiteer);

-er

(writer,

type-writer); -ess

(actress,

lioness); -hood

(manhood);

-ing

(building,

meaning, washing); -ion/-sion/-tion/-ation

(rebellion,

tension, creation, explanation); -ism/-icism

(heroism,

criticism); -ist

(novelist,

communist); -ment

(government,

nourishment); -ness

(tenderness);

-ship

(friendship);

-(i)ty

(sonority).

Adjective-forming

suffixes:

-able/-ible/-uble

(unbearable,

audible, soluble); -al

(formal);

-ic

(poetic);

-ical

(ethical);

-ant/-ent

(repentant,

dependent); -ary

(revolutionary);

-ate/-ete

(accurate,

complete); -ed/-d

(wooded);

-ful

(delightful);

-an/-ian

(African,

Australian); -ish

(Irish,

reddish, childish);

-ive

(active);

-less

(useless);

-like

(lifelike);

-ly

(manly);

-ous/-ious

(tremendous,

curious); -some

(tiresome);

-y

(cloudy,

dressy).

Numeral-forming

suffixes:

-fold

(twofold);

-teen

(fourteen);

-th

(seventh);

-ty

(sixty).

Verb-forming

suffixes:

-ate

(facilitate);

-er

(glimmer);

-en

(shorten);

-fy/-ify

(terrify,

speechify, solidify); -ise/-ize

(equalise);

-ish

(establish).

Adverb-forming

suffixes:

—ly

(coldly);

-ward/-wards

(upward,

northwards); -wise

(likewise).

If we change our approach and

become interested in the lexico-grammatical meaning the suffixes

serve to signalise, we obtain within each part of speech more

detailed lexico-grammatical classes or subclasses.

Taking up nouns we can

subdivide them into proper and common nouns. Among common nouns we

shall distinguish personal names, names of other animate beings,

collective nouns, falling into several minor groups, material nouns,

abstract nouns and names of things.

Abstract

nouns are signalled by the following suffixes: -age,

-ance/ -ence, -ancy/-ency, -dom, -hood, -ing, -ion/-tion/-ation,

-ism, -ment, -ness, -ship, -th, -ty.1

Personal

nouns that are emotionally neutral occur with the following suffixes:

-an

{grammarian),

-ant/-ent

(servant,

student), -arian

(vegetarian),

—ее

(examinee),

-er

(porter),

-ician

(musician),

-ist

(linguist),

-ite

(sybarite),

-or

(inspector),

and

a few others.

Feminine

suffixes may be classed as a subgroup of personal noun suffixes.

These are few and not frequent: -ess

(actress),

-ine

(heroine),

-rix

(testatrix),

-ette

(cosmonette).

The

above classification should be accepted with caution. It is true that

in a polysemantic word at least one of the variants will show the

class meaning signalled by the affix. There may be other variants,

however, whose different meaning will be signalled by a difference in

distribution, and these will belong to some other lexico-grammatical

class. Cf.

settlement,

translation denoting

a process and its result, or beauty

which,

when denoting qualities that give pleasure to the eye or to the mind,

is an abstract noun, but occurs also as a personal noun denoting a

beautiful woman. The word witness

is

more often used in its several personal meanings than (in accordance

with its suffix) as an abstract noun meaning ‘evidence’ or

‘testimony’. The coincidence of two classes in the semantic

structure of some words may be almost regular. Collectivity, for

instance, may be signalled by such suffixes as -dom,

-ery-, -hood, -ship. It must

be borne in mind, however, that words with these suffixes are

polysemantic and show a regular correlation of the abstract noun

denoting state and a collective noun denoting a group of persons of

whom this state is characteristic, сf.

knighthood.

Alongside

with adding some lexico-grammatical meaning to the stem, certain

suffixes charge it with emotional force. They may be derogatory: -ard

(drunkard),

-ling

(underling);

-ster

(gangster),

-ton

(simpleton),

These

seem to be more numerous in English than the suffixes of endearment.

Emotionally

coloured diminutive

suffixes rendering also endearment differ from the derogatory

suffixes in that they are used to name not only persons but things as

well. This point may be illustrated by

the suffix -y/-ie/-ey

(auntie,

cabbie (cabman), daddy), but

also: hanky

(handkerchief),

nightie (night-gown). Other

suffixes that express smallness are -kin/-kins

(mannikin);

-let

(booklet);

-ock

(hillock);

-ette

(kitchenette).

The

connotation

(see p. 47ff) of some diminutive suffixes is not one of endearment

but of some outlandish elegance and novelty, particularly in the case

of the borrowed suffix -ette

(kitchenette,

launderette, lecturette, maisonette, etc.).

Derivational

morphemes affixed before the stem are called prefixes.

Prefixes modify the lexical meaning of the stem, but in so doing they

seldom affect its basic lexico-grammatical component. Therefore both

the simple word and its prefixed derivative mostly belong to the same

part of speech. The prefix mis-,

for

instance, when added to verbs, conveys the meaning ‘wrongly’,

‘badly’, ‘unfavourably’; it does not suggest any other part

of speech but the verb. Compare the following oppositions: behave

:

: misbehave,

calculate :

: miscalculate,

inform :

: misinform,

lead :

: mislead,

pronounce :

: mispronounce.

The

above oppositions

are strictly proportional

semantically,

i.e. the same relationship between elements holds throughout the

series. There may be other cases where the semantic relationship is

slightly different but the general lexico-grammatical meaning

remains, cf.

giving

:

: misgiving

‘foreboding’

or ‘suspicion’; take

:

: mistake

and

trust

:

: mistrust.

The

semantic effect of a prefix may be termed adverbial because it

modifies the idea suggested by the stem for manner, time, place,

degree and so on. A few examples will prove the point. It has been

already shown that the prefix mis-

is

equivalent to the adverbs wrongly

and

badly,

therefore

by expressing evaluation it modifies the corresponding verbs for

manner.1

The prefixes pre-

and

post-

refer

to time and order, e. g. historic

::

pre-historic,

pay ::

prepay,

view ::

preview.

The

last word means ‘to

view a film or a play before it is submitted to the general public’.

Compare also: graduate

::

postgraduate

(about

the course of study carried on after graduation), Impressionism

::

Post-impressionism.

The

latter is so called because it came after Impressionism as a reaction

against it. The prefixes in-,

a-, ab-, super-, sub-, trans- modify

the stem for place, e. g. income,

abduct ‘to

carry away’, subway,

transatlantic. Several

prefixes serve to modify the meaning of the stem for degree and size.

The examples are out-,

over- and under-. The

prefix out-

has

already been described (see p. 95).

Compare

also the modification for degree in such verbs as overfeed

and

undernourish,

subordinate.

The

group of negative prefixes is so numerous that some scholars even

find it convenient to classify prefixes into negative and

non-negative ones. The negative ones are: de-,

dis-, in-/im-/il-/ir-, поп-,

ип-.

Part

of this group has been also more accurately classified as prefixes

giving negative, reverse or opposite meaning.2

The

prefix de-

occurs

in many neologisms, such as decentralise,

decontaminate

‘remove

contamination from the area or the clothes’, denazify,

etc.

The

general idea of negation is expressed by dis-;

it

may mean ‘not’, and be simply negative or ‘the reverse of,

‘asunder’, ‘away’, ‘apart’ and then it is called

reversative. Cf.

agree

:

: disagree

‘not

to agree’ appear

:

: disappear

(disappear

is the reverse of appear), appoint

:

: dis-.

appoint ‘to

undo the appointment and thus frustrate the expectation’, disgorge

‘eject

as from the throat’, dishouse

‘throw

out, evict’. /n-/

im-/ir-/il

have

already been discussed, so there is no necessity to dwell upon them.

Non-

is

often used in abstract verbal nouns such as noninterference,

nonsense or

non-resistance,

and

participles or former participles like non-commissioned

(about

an officer in the army below the rank of

a commissioned officer), non-combatant

(about

any one who is connected

with the army but is there for some purpose other than fighting, as,

for instance, an army surgeon.)

Non-

used

to be restricted to simple unemphatic negation. Beginning with the

sixties non-

indicates

not so much the opposite of something but rather that something is

not real or worthy of the name. E. g. non-book

—

is

a book published to be purchased rather than to be read, non-thing

—

something

insignificant and meaningless.

The

most frequent by far is the prefix un-;

it

should be noted that it may convey two different meanings, namely:

-

Simple

negation, when attached to adjective stems or to participles: happy

:

: unhappy,

kind :

: unkind,

even :

: uneven.

It

is immaterial whether the stem is native or borrowed, as the suffix

un-

readily

combines with both groups. For instance, uncommon,

unimportant, etc.

are hybrids. -

The

meaning is reversative when un-

is

used with verbal stems. In that case it shows action contrary to

that of the simple word: bind

:

:

unbind,

do :

: undo,

mask :

: unmask,

pack :

: unpack.

A

very frequent prefix with a great combining power is re-

denoting

repetition of the action expressed by the stem. It may be prefixed to

almost any verb or verbal noun: rearrange

v,

recast

v

‘put into new shape’, reinstate

v

‘to place again in a former position’, refitment

n

‘repairs and renewal’, remarriage

n,

etc. There are, it must be remembered, some constraints. Thus, while

reassembled

or

revisited

are

usual, rereceived

or

reseen

do

not occur at all.

The meaning of a prefix is not

so completely fused with the meaning of the primary stem as is the

case with suffixes, but retains a certain degree of semantic

independence.

It will be noted that among

the above examples verbs predominate. This is accounted for by the

fact that prefixation in English is chiefly characteristic of verbs

and words with deverbal stems.

The

majority of prefixes affect only the lexical meaning of words but

there are three important cases where prefixes serve to form words

belonging to different parts of speech as compared with the original

word.

These

are in the first place the verb-forming prefixes be-

and

en-,

which

combine functional meaning with a certain variety of lexical

meanings.1

Be-

forms

transitive verbs with adjective, verb and noun stems and changes

intransitive verbs into transitive ones. Examples are: belittle

v

‘to make little’, benumb

v

‘to make numb’, befriend

v

‘to treat

like

a friend’, becloud

v

(bedew

v,

befoam

v)

‘to cover with clouds (with dew

or with foam)’, bemadam

v

‘to call madam’, besiege

v

‘to lay siege

on’. Sometimes the lexical meanings are very different; compare,

for instance, bejewel

v

‘to deck with jewels’ and behead

v

which has the meaning of ‘to cut the head from’. There are on the

whole about six semantic verb-forming varieties and one that makes

adjectives from noun stems following the pattern be-

+

noun

stem +

-ed,

as

in benighted,

bespectacled, etc.

The pattern is often connected with a contemptuous emotional

colouring.

The

prefix en-/em-

is

now used to form verbs from noun stems with the meaning ‘put (the

object) into, or on, something’, as in embed,

engulf, encamp, and

also to form verbs with adjective and noun stems with the meaning ‘to

bring into such condition or state’, as in enable

v,

enslave

v,

encash

v.

Sometimes the prefix en-/em—

has an intensifying function, cf. enclasp.

The

prefix a-

is

the characteristic feature of the words belonging to statives:

aboard,

afraid, asleep, awake, etc.

1

As a prefix forming the words of the category of state a- represents:

(1) OE preposition on,

as

abed,

aboard, afoot; (2)

OE preposition of,

from, as

in anew,

(3)

OE prefixes ge-

and

y-

as

in aware.

This

prefix has several homonymous morphemes which modify only the lexical

meaning of the stem, cf. arise

v,

amoral

a.

The

prefixes pre-,

post-, non-, anti-, and

some other Romanic and Greek prefixes very productive in present-day

English serve to form adjectives retaining at the same time a very

clear-cut lexical meaning, e. g. anti-war,

pre-war, post-war, non-party, etc.

From

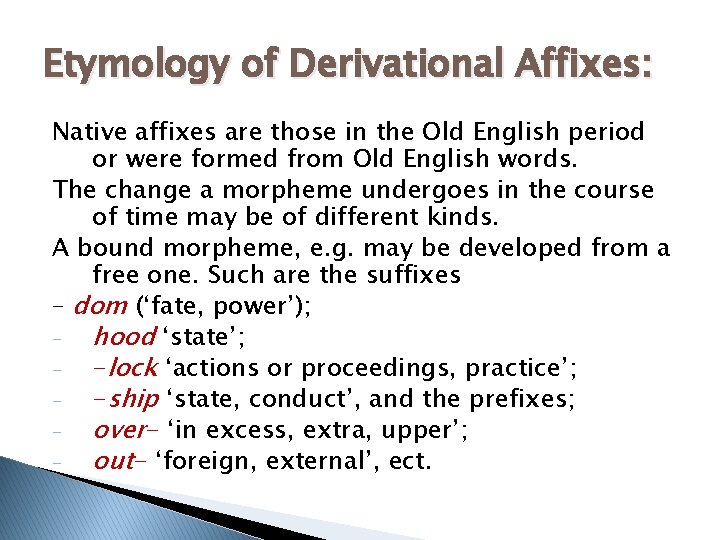

the point of view of etymology affixes are subdivided into two main

classes: the native affixes and the borrowed affixes. By native

affixes we

shall mean those that existed in English in the Old English period or

were formed from Old English words. The latter category needs some

explanation. The changes a morpheme undergoes in the course of

language history may be of very different kinds. A bound form, for

instance, may be developed from a free one. This is precisely the

case with such English suffixes as —dom,

-hood,

-lock, -ful, -less, -like, -ship, e.

g. ModE -dom

<

OE dom

‘fate’,

‘power’, cf. ModE doom.

The

suffix -hood

that

we see in childhood,

boyhood is

derived from OE had

‘state’.

The OE lac

was

also a suffix denoting state. The process may be summarised

as follows: first lac

formed

the second element of compound words, then

it became a suffix and lastly was so fused with the stem as to become

a dead suffix in wedlock.

The

nouns freedom,

wisdom, etc.

were originally

compound words.

The

most important native suffixes are: -d,

-dom, -ed, -en, -fold, -ful, -hood, -ing, -ish, -less, -let, -like,

-lock, -ly, -ness, -oc, -red, -ship, -some, -teen, -th, -ward, -wise,

-y.

The

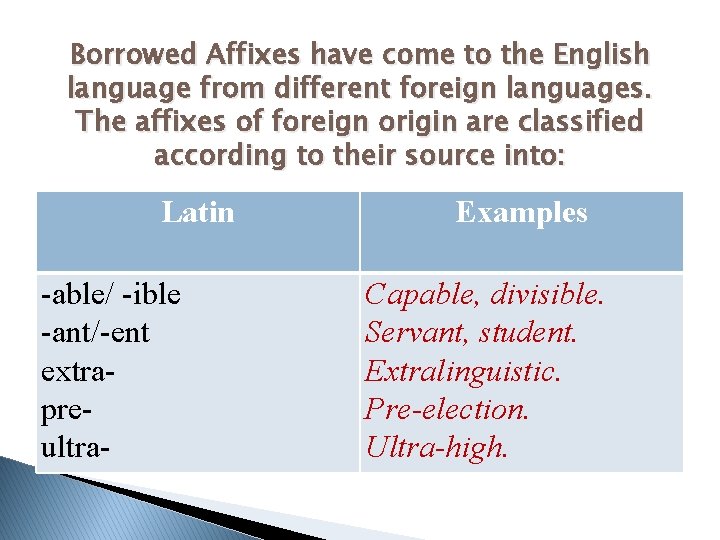

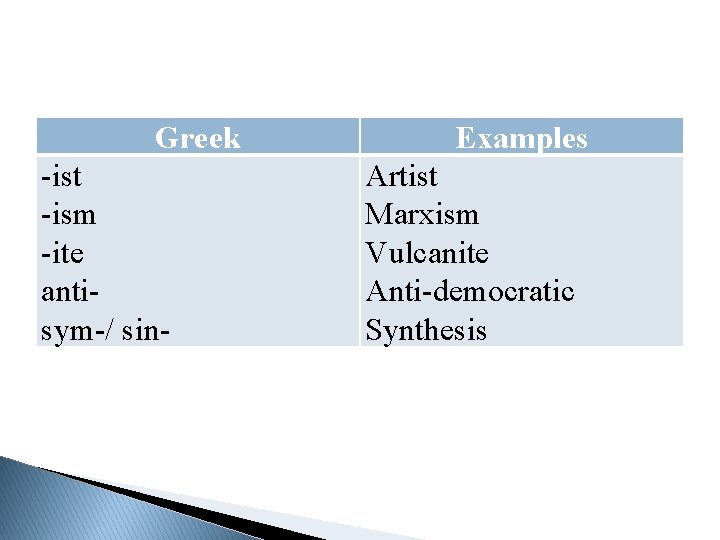

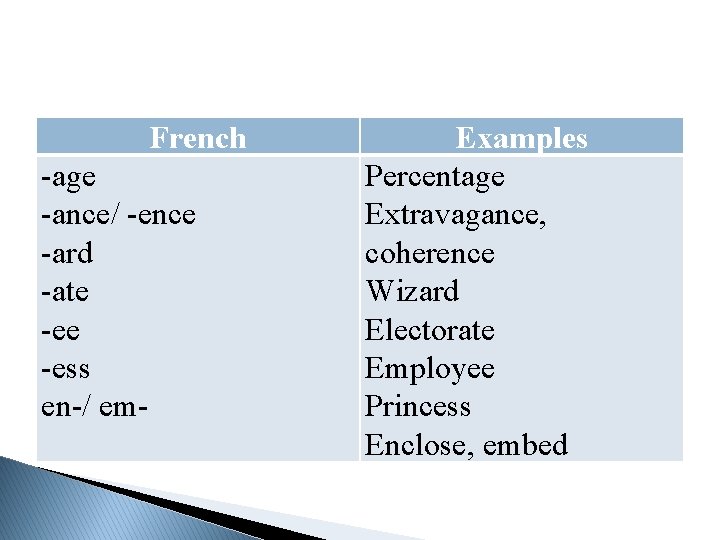

suffixes of foreign origin are classified according to their source

into Latin (-able/-ible,

-ant/-ent), French

(-age,

-ance/-ence, -ancy/-ency, -ard, -ate, -sy), Greek

(-ist,

-ism, -ite), etc.

The

term borrowed

affixes

is not very exact as affixes are never

borrowed as such, but only as parts of loan

words.

To enter the morphological system of the English language a borrowed

affix has to satisfy certain conditions. The borrowing of the affixes

is possible only if the number of words containing this affix is

considerable, if its meaning and function are definite and clear

enough, and also if its structural pattern corresponds to the

structural patterns already existing in the language.

If

these conditions are fulfilled, the foreign affix may even become

productive and combine with native stems or borrowed stems within the

system of English vocabulary like

-able <

Lat

-abilis

in

such words as laughable

or

unforgettable

and

unforgivable.

The

English words balustrade,

brigade, cascade are

borrowed from French. On the analogy with these in the English

language itself such words as blockade

are

coined.

It should be noted that many

of the borrowed affixes are international and occur not only in

English but in several other European languages as well.

“THE

STONE

WALL PROBLEM”

The

so-called stone

wall problem

concerns the status of the complexes like stone

wall, cannon ball or

rose

garden. Noun

premodifiers of other nouns often become so closely fused together

with what they modify that it is difficult to say whether the result

is a compound or a syntactical free phrase. Even if this difficulty

is solved and we agree that these are phrases and not words, the

status of the first element remains to be determined. Is it a noun

used as an attribute or is it to be treated as an adjective?

The

first point to be noted is that lexicographers differ in their

treatment. Thus, “The Heritage Dictionary of the English Language”

combines in one entry the noun stone

and

the adjective stone

pertaining

to or made of stone’ and gives as an example this very combination

stone

wall. In

his dictionary A.S. Hornby, on the other hand, when beginning the

entry —

stone

as

an uncountable noun, adds that it is often used attributively and

illustrates this statement with the same example —

stone

wall.

R.

Quirk and his colleagues in their fundamental work on the grammar of

contemporary English when describing premodification of nouns by

nouns emphasise the fact that they become so closely associated as to

be regarded as compounds. The meaning of noun premodification may

correspond to an of-phrase as in the following the

story of his life —

his

life story, or

correlate with some other prepositional phrase as in a

war story

—

a

story about war, an arm chair —

a

chair with arms, a dish cloth —

a

cloth for dishes.

There

is no consistency in spelling, so that in the A.S. Hornby’s

Dictionary both arm-chair

and

dish-cloth

are

hyphenated.

R.

Quirk finds orthographic criteria unreliable, as there are no hard

and fast rules according to which one may choose solid, hyphenated or

open spelling. Some examples of complexes with open spelling that he

treats as compound words are: book

review, crime report, office management,

steel production, language teacher. They

are placed in different structural

groups according to the grammatical process they reflect. Thus,

book

review, crime report and

haircut

are

all compound count nouns formed

on the model object+deverbal

noun: X

reviews books →

the

reviewing

of books →

book

review. We

could reasonably take all the above examples

as free syntactic phrases, because the substitution of some equonym

for the first element would leave the meaning of the second intact.

We could speak about nickel

production or

a

geography teacher. The

first elements may be modified by an adjective —

an

English language teacher especially

because the meaning of the whole can be inferred from the meaning of

the parts.

H.

Marchand also mentions the fact that ‘stone

‘wall is

a two-stressed combination, and the two-stressed pattern never shows

the intimate permanent semantic relationship between the two

components that is characteristic of compound words. This stress

pattern stands explained if we interpret the premodifying element as

an adjective or at least emphasise its attributive function. The same

explanation may be used to account for the singularisation that takes

place, i.e. the compound is an

arm-chair not

*an

arms-chair.

Singularisation

is observed even with otherwise

invariable plural forms. Thus, the game is called billiards

but

a table for it is a

billiard table and

it stands in a

billiard-room. A

similar example is a

scissor sharpener that

is a sharpener for scissors. One further theoretical point may be

emphasised, this is the necessity of taking into account the context

in which these complexes are used. If the complex is used

attributively before a third noun, this attributive function joins

them more intimately. For example:

I

telephoned:

no air-hostess trainees had been kept late (J.

Fowles).

It

is especially important in case a compound of this type is an

author’s neologism. E. g. :

The

train was full of soldiers. I once again felt the great current of

war, the European death-wish (J.

Fowles).

It

should, perhaps, be added that an increasing number of linguists are

now agreed —

and

the evidence at present available seems to suggest they are right —

that

the majority of English nouns are regularly used to form nominal

phrases that are semantically derivable from their components but in

most cases develop some unity of referential meaning. This

set of nominal phrases exists alongside the set of nominal compounds.

The

boundaries between the two sets are by no means rigid, they are

correlated and many compounds originated as free phrases.

Lecture 6 Word-structure and Word-formation

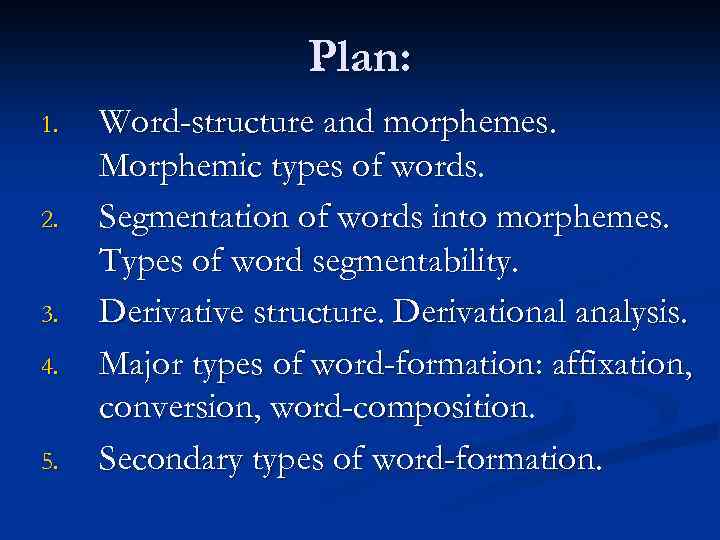

Plan: 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. Word-structure and morphemes. Morphemic types of words. Segmentation of words into morphemes. Types of word segmentability. Derivative structure. Derivational analysis. Major types of word-formation: affixation, conversion, word-composition. Secondary types of word-formation.

1. Word-structure and morphemes. Morphemic types of words

The Morpheme: the smallest ____ indivisible two-facet language unit.

Meaning of word building morphemes: 1. lexical meaning: — ______ (serves a linguistic expression for a concept or a name for an individual object) Especially revealed in root-morphemes. E. g. -girl- -ly, -like, -ish ; – similarity — ______ (an emotional content of the morpheme) E. g. the suffix in piglet has a diminutive meaning.

Word building morphemes do not possess grammatical meaning.

Meaning of word building morphemes: 2. part-of-speech meaning (is proper only to _______) (government, teach-er)

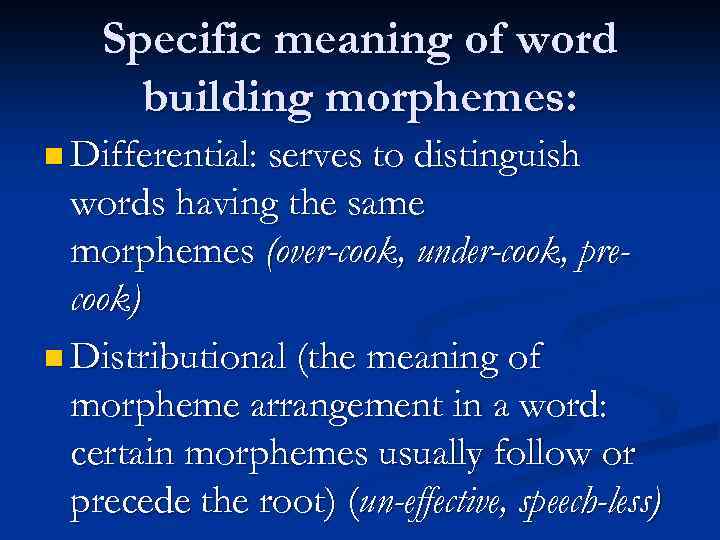

Specific meaning of word building morphemes: n Differential: serves to distinguish words having the same morphemes (over-cook, under cook, precook) n Distributional (the meaning of morpheme arrangement in a word: certain morphemes usually follow or precede the root) (un-effective, speech-less)

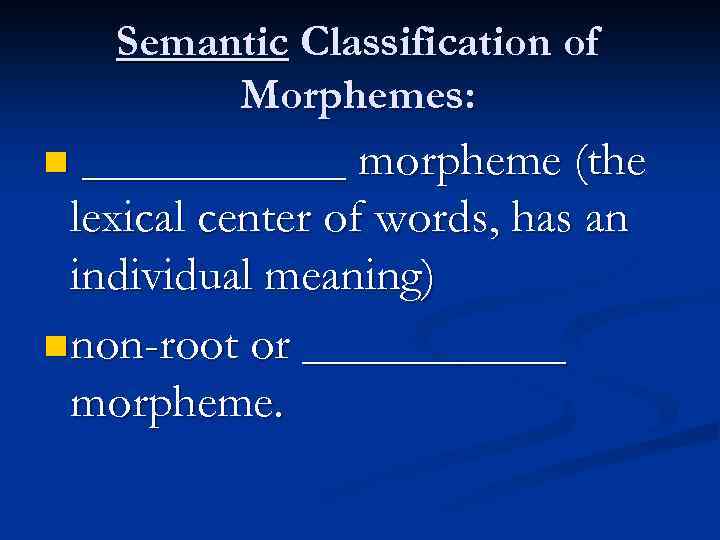

Semantic Classification of Morphemes: ______ morpheme (the lexical center of words, has an individual meaning) n non-root or ______ morpheme. n

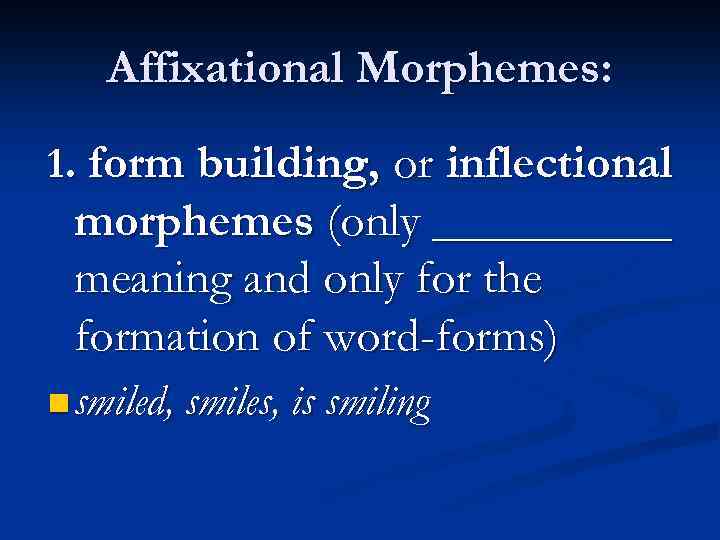

Affixational Morphemes: 1. form building, or inflectional morphemes (only _____ meaning and only for the formation of word-forms) n smiled, smiles, is smiling

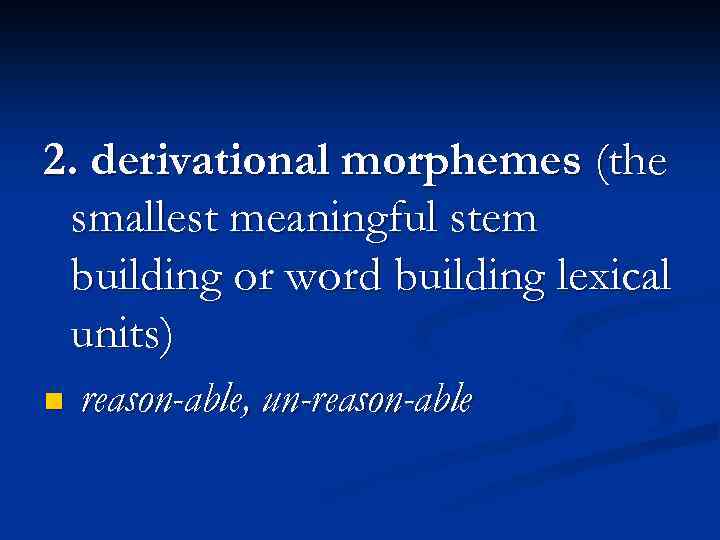

2. derivational morphemes (the smallest meaningful stem building or word building lexical units) n reason-able, un-reason-able

Derivational morphemes: n prefixes n suffixes

Structural classification: 1. ______ morphemes (may function independently. Most roots are free) n friend- in the word friendship 2. ______ morphemes (function only as a constituent part of a word). Affixes are bound morphemes.

3. semi-free (semi-bound) morphemes (can function both as an ______ and as a ______ morpheme). n • • the morpheme well: the stem and the word-form in the utterance like sleep well; a bound morpheme in the word wellknown.

According to the Number of the Morphemes: § monomorphic words § polymorphic

Monomorphic or root -words: only one rootmorpheme. § small, dog.

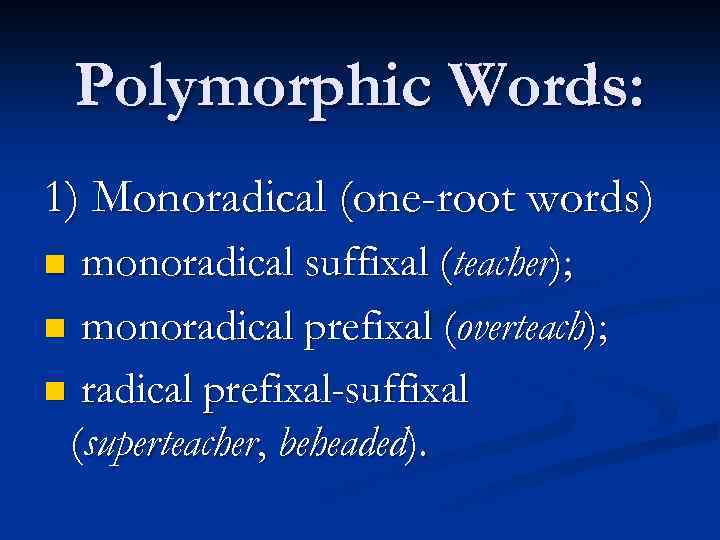

Polymorphic Words: 1) Monoradical (one-root words) monoradical suffixal (teacher); n monoradical prefixal (overteach); n radical prefixal-suffixal (superteacher, beheaded). n

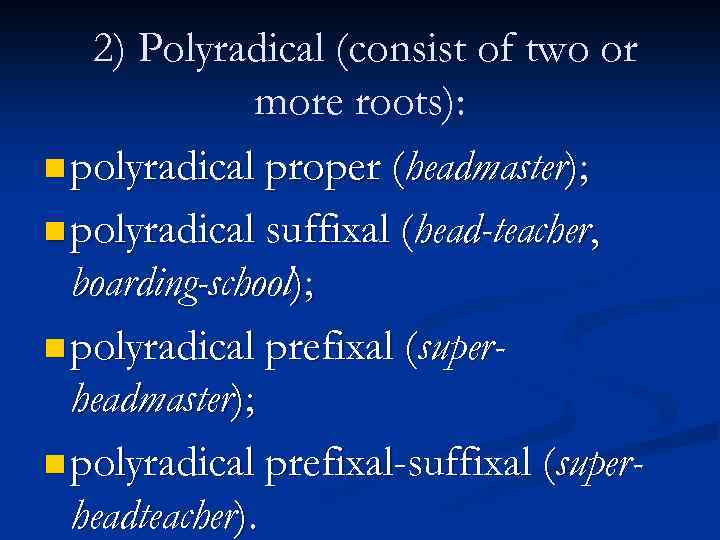

2) Polyradical (consist of two or more roots): n polyradical proper (headmaster); n polyradical suffixal (head-teacher, boarding-school); n polyradical prefixal (superheadmaster); n polyradical prefixal-suffixal (superheadteacher).

2. Segmentation of words into morphemes. Types of word segmentability

According to the complexity of the morphemic structure: 1. segmentable words (allowing of segmentation into morphemes). n agreement, information, quickly. 2. non-segmentable words. n house, girl, woman.

Levels of the Analysis of the Word Structure: n Morphemic: its aim is to state the number and type of morphemes the word consists of. Basic units: ______ mislead — polymorphic, monoradical, radical-prefixal.

n Derivational: its aim is to establish the correlations between different types of words and to establish a word’s derivational structure. Basic units: derivational bases, derivational affixes, derivational patterns.

The Morphemic Analysis: the operation of breaking a segmentable word into the constituent morphemes.

The method of Immediate and Ultimate constituents (the IC and UC method): to know how many _____ parts are there in a word.

At every stage the word is broken into 2 components (IC-s) unless we achieve units incapable of further division – the so-called ultimate constituents.

Friendliness: 1. is divided into the component friendly-, occurring in such words as friendly, friendly-looking, and the component ness- as in dark-ness, happy-ness. 2. is divided into friend- and -ly which are ultimate constituents.

Types of Morphemic Segmentability of Words: 1. complete 2. conditional 3. defective

Complete Segmentability: one can easily divide a word into morphemes. The constituent morphemes of the word recur with the same meaning in a number of other words. n teacher: teach- — in to teach and teaching. -er – in words like worker, builder, etc.

Conditional Segmentability: when segmentation is doubtful for ____ reasons, as the segments (pseudo-morphemes) regularly occurring in other words can hardly possess any definite lexical meaning.

n retain, detain, contain or receive, conceive, perceive: sound-clusters [rı-], [dı-], [kən-] seem to be singled out quite easily due to their recurrence in a number of words, but they have nothing in common with the phonetically identical morphemes like re-, de- as in words rewrite, re-organize, decode.

Defective Segmentability: when segmentation is doubtful for ______ reasons because one of the components (a unique morpheme) has a specific lexical meaning but seldom or never occurs in other words.

n streamlet, ringlet, leaflet: the morpheme -let has the denotational meaning of diminutiveness and is combined with the morphemes stream-, ring-, leaf-, each having a clear denotational meaning. n hamlet – the morpheme -let retains the same meaning of diminutiveness, but the soundcluster [hæm] does not occur in any English word with the meaning it has in the word hamlet.

Morphological analysis: + reveals the number of meaningful constituents in a word and their usual sequence. — does not reveal the way the word is constructed.

3. Derivative structure. Derivational analysis

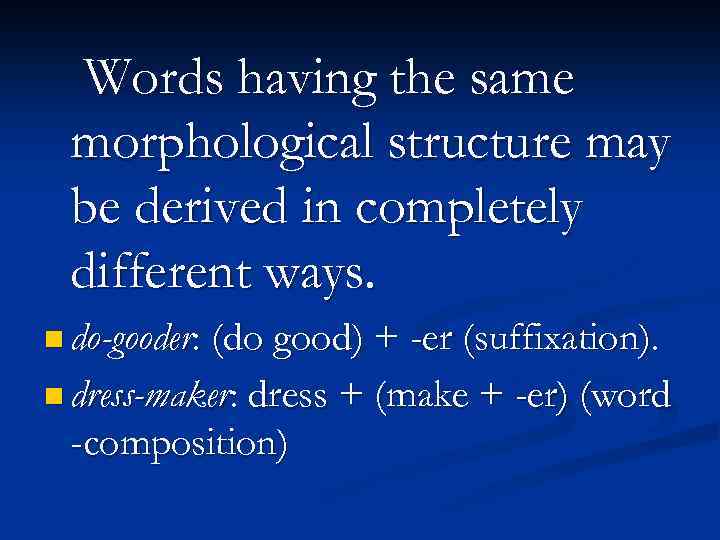

Words having the same morphological structure may be derived in completely different ways. n do-gooder: (do good) + -er (suffixation). n dress-maker: dress + (make + -er) (word -composition)

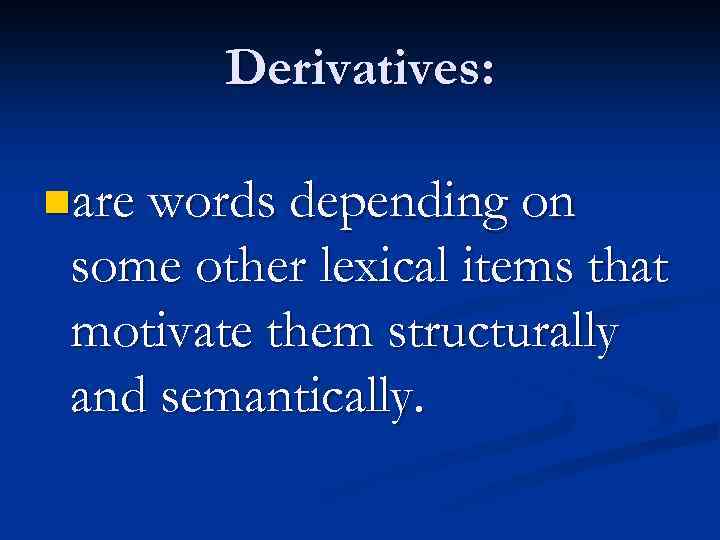

Derivatives: nare words depending on some other lexical items that motivate them structurally and semantically.

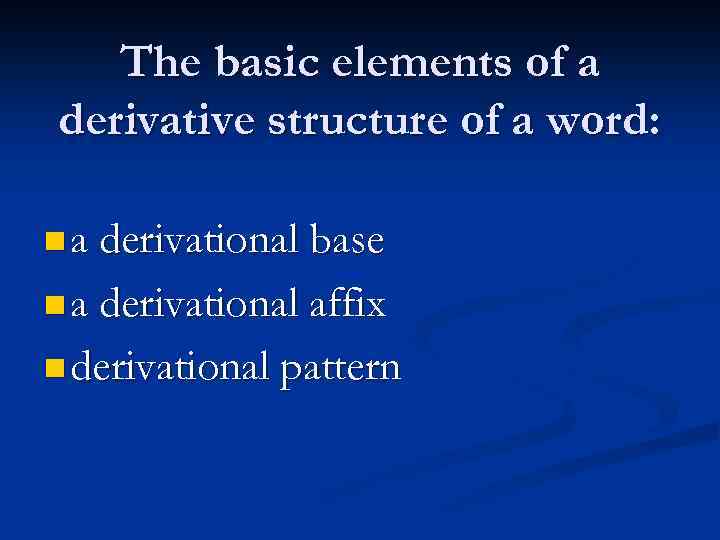

The basic elements of a derivative structure of a word: n a derivational base n a derivational affix n derivational pattern

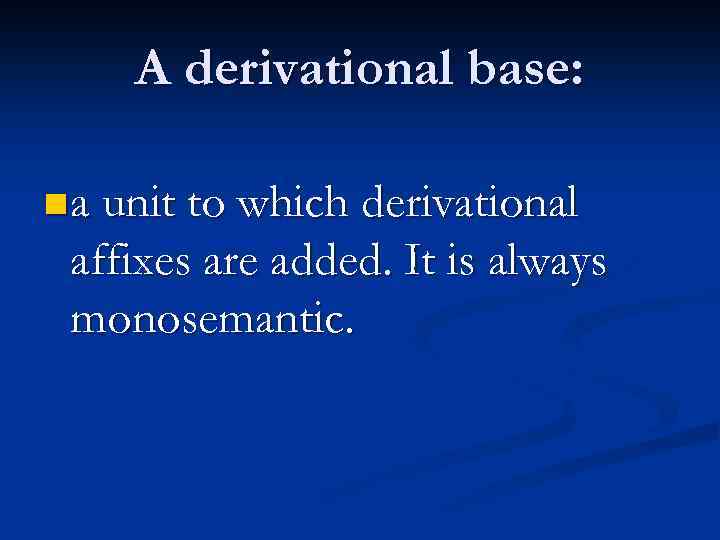

A derivational base: n a unit to which derivational affixes are added. It is always monosemantic.

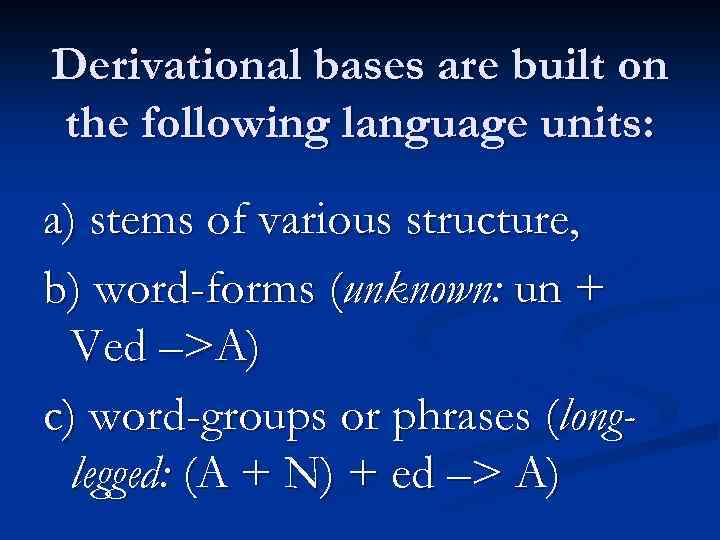

Derivational bases are built on the following language units: a) stems of various structure, b) word-forms (unknown: un + Ved –>A) c) word-groups or phrases (longlegged: (A + N) + ed –> A)

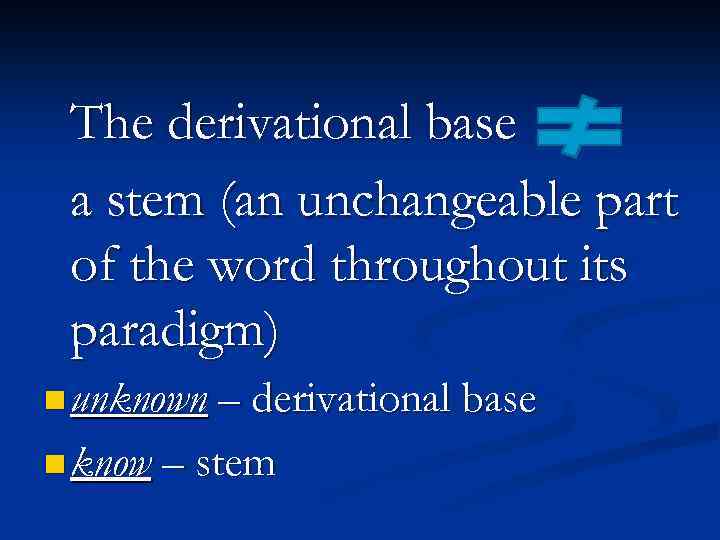

The derivational base a stem (an unchangeable part of the word throughout its paradigm) n unknown – derivational base n know – stem

A derivational affix is added to a derivational base.

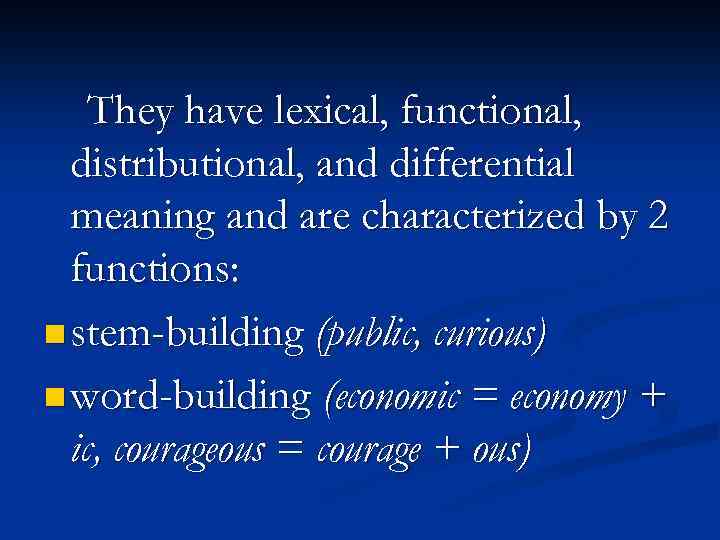

They have lexical, functional, distributional, and differential meaning and are characterized by 2 functions: n stem-building (public, curious) n word-building (economic = economy + ic, courageous = courage + ous)

A derivational pattern: a scheme of order and arrangement of the IC-s of the word. n v + -er =N (teach-teacher, build- builder) n re + v = V (re + write — rewrite)

4. Major types of wordformation: affixation, conversion, wordcomposition

In English there are three major types of word-formation: affixation, n zero derivation (conversion), n composition (compounding). n

Affixation. Prefixation. Classifications of prefixes. Suffixation. Classifications of suffixes. Productivity of suffixes.

Affixation has been one of the most productive ways of word-building throughout the history of English.

Affixation: n formation of new words by adding _____ affixes to different types of derivational bases.

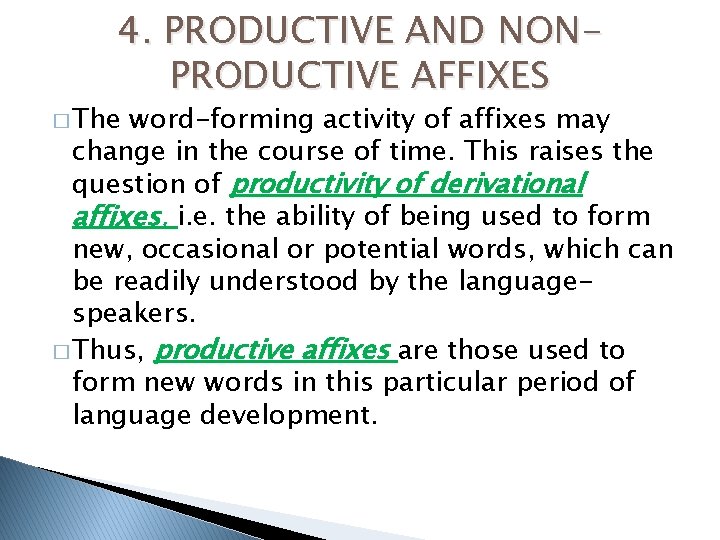

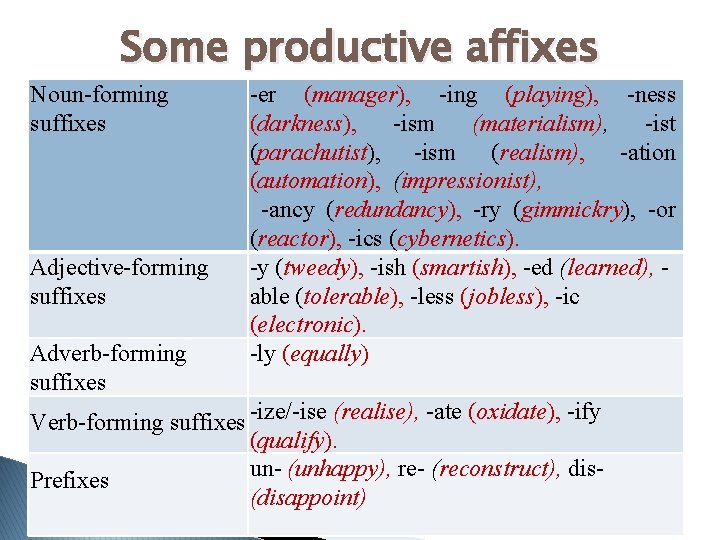

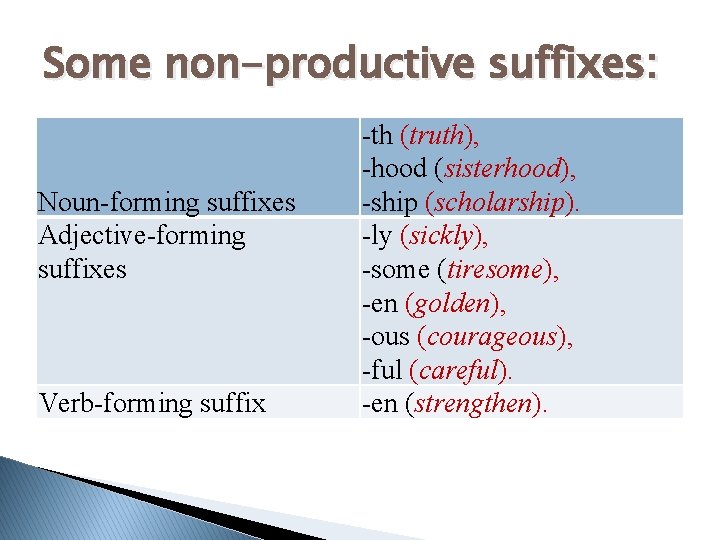

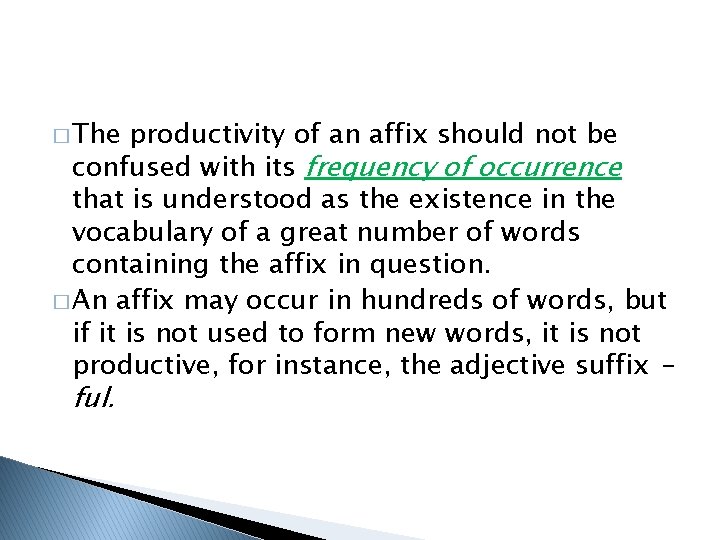

Affixes: n ______ (take part in deriving new words in the particular period of language development. To identify productive affixes one should look for them among neologisms). E. g. -er, -able. n ______. E. g. -hood, -ous.

The productivity of affixes their frequency of occurrence: there are some high-frequency affixes which are no longer used in word derivation (the adjective-forming suffixes -ful, -ly, etc. ).

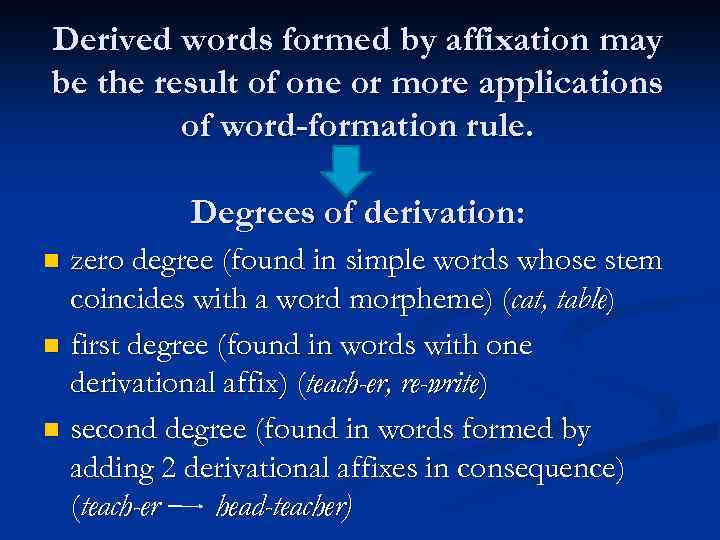

Derived words formed by affixation may be the result of one or more applications of word-formation rule. Degrees of derivation: zero degree (found in simple words whose stem coincides with a word morpheme) (cat, table) n first degree (found in words with one derivational affix) (teach-er, re-write) n second degree (found in words formed by adding 2 derivational affixes in consequence) (teach-er head-teacher) n

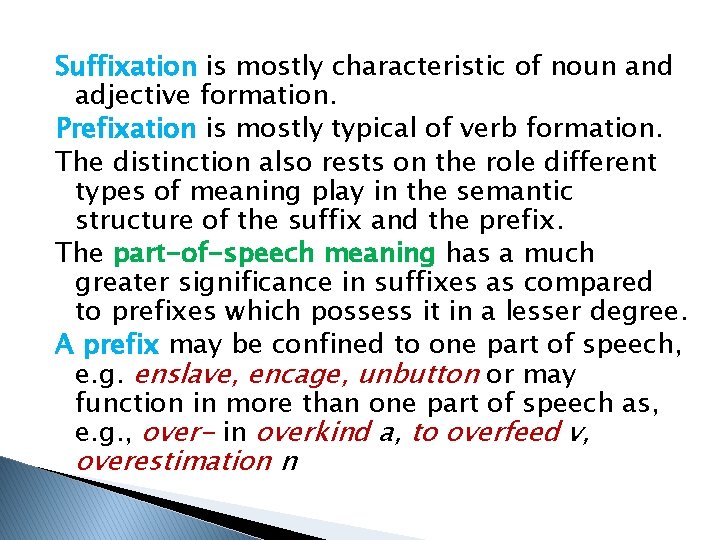

Affixation: n suffixation n prefixation

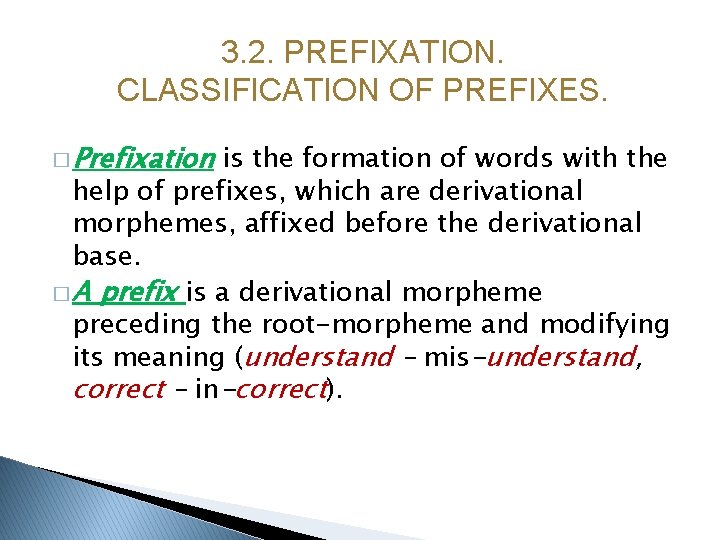

Prefixation is the formation of words by means of adding a ______ to the stem. There about 51 prefixes in the system of Modern English word-formation.

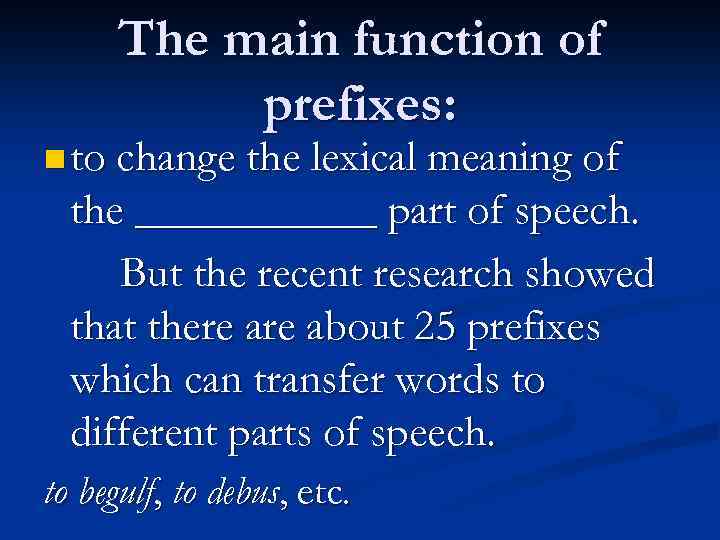

The main function of prefixes: n to change the lexical meaning of the ______ part of speech. But the recent research showed that there about 25 prefixes which can transfer words to different parts of speech. to begulf, to debus, etc.

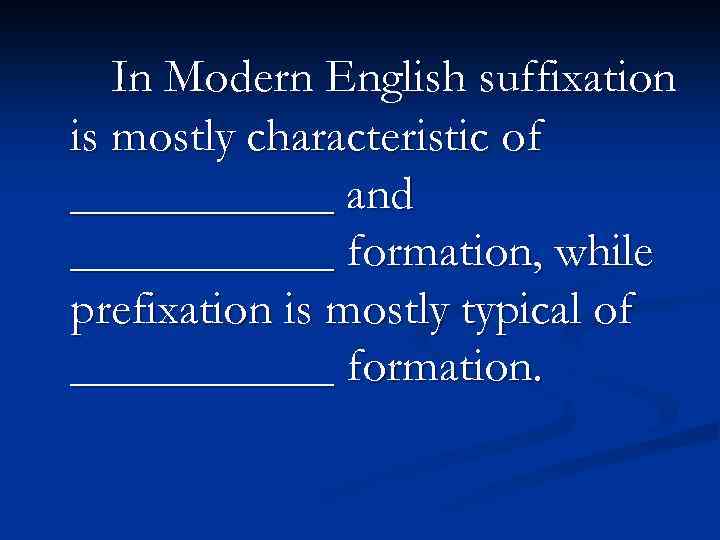

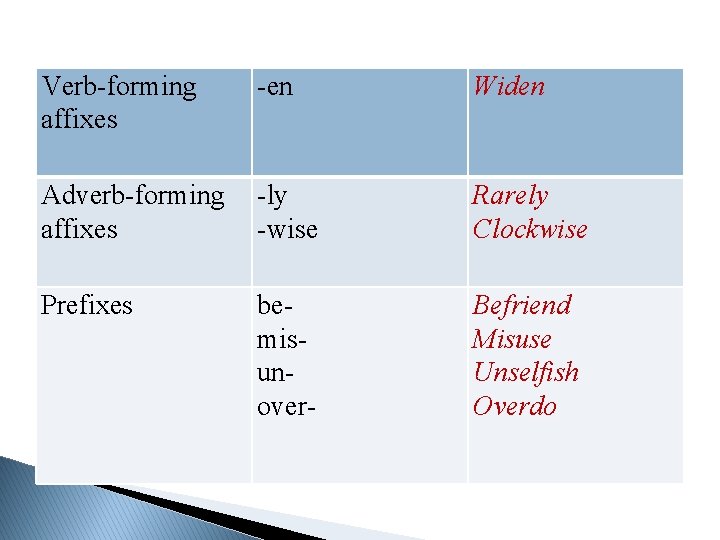

In Modern English suffixation is mostly characteristic of ______ and ______ formation, while prefixation is mostly typical of ______ formation.

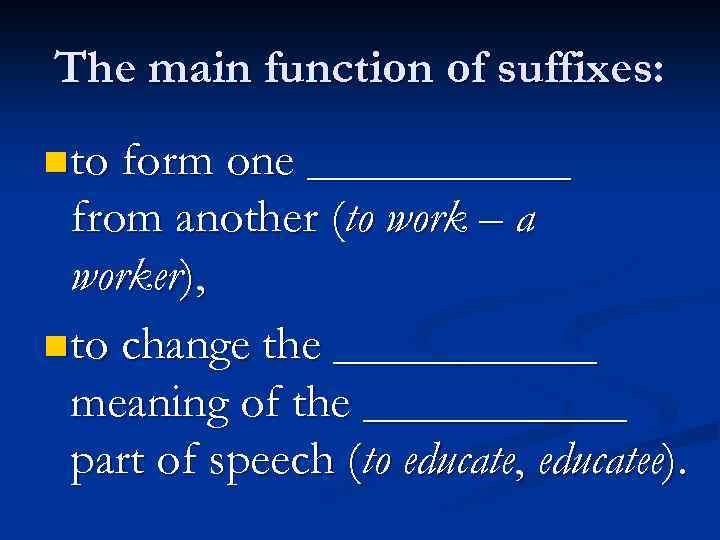

The main function of suffixes: n to form one ______ from another (to work – a worker), n to change the ______ meaning of the ______ part of speech (to educate, educatee).

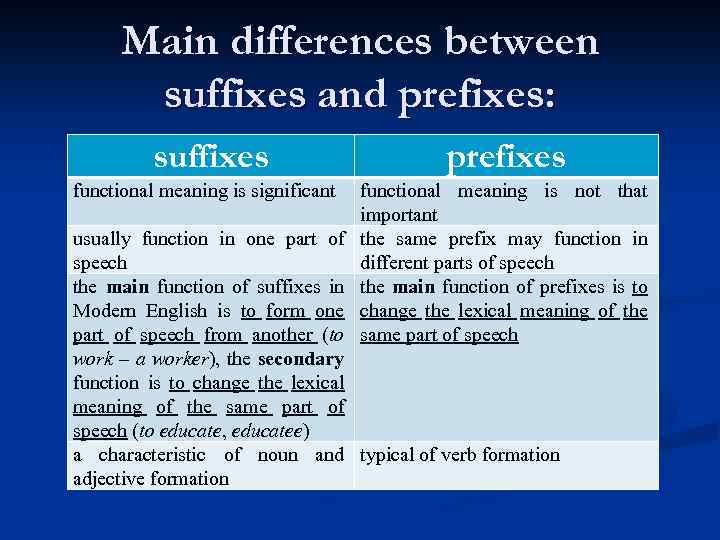

Main differences between suffixes and prefixes: suffixes functional meaning is significant prefixes functional meaning is not that important the same prefix may function in different parts of speech the main function of prefixes is to change the lexical meaning of the same part of speech usually function in one part of speech the main function of suffixes in Modern English is to form one part of speech from another (to work – a worker), the secondary function is to change the lexical meaning of the same part of speech (to educate, educatee) a characteristic of noun and typical of verb formation adjective formation

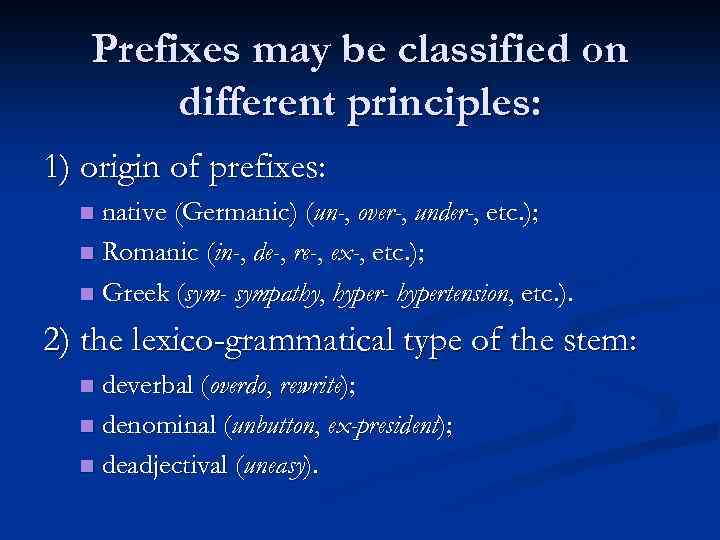

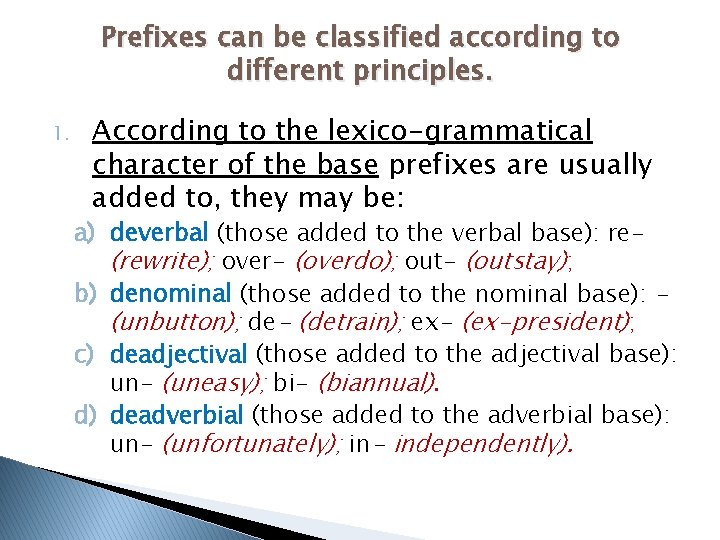

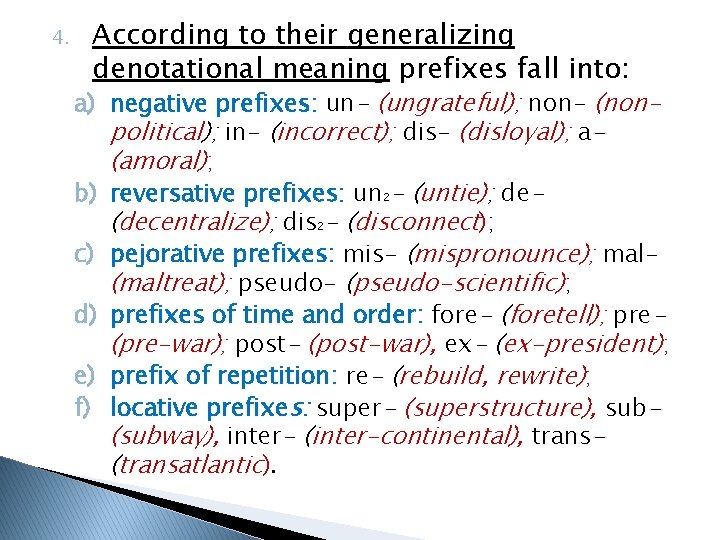

Prefixes may be classified on different principles: 1) origin of prefixes: native (Germanic) (un-, over-, under-, etc. ); n Romanic (in-, de-, re-, ex-, etc. ); n Greek (sym- sympathy, hyper- hypertension, etc. ). n 2) the lexico-grammatical type of the stem: deverbal (overdo, rewrite); n denominal (unbutton, ex-president); n deadjectival (uneasy). n

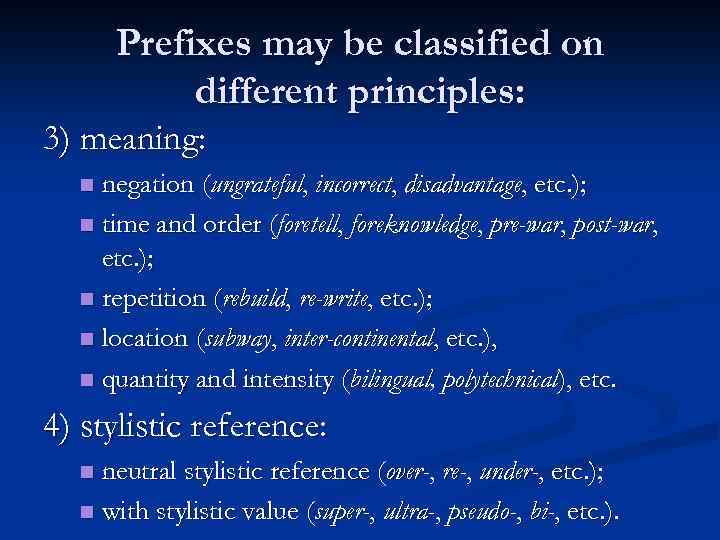

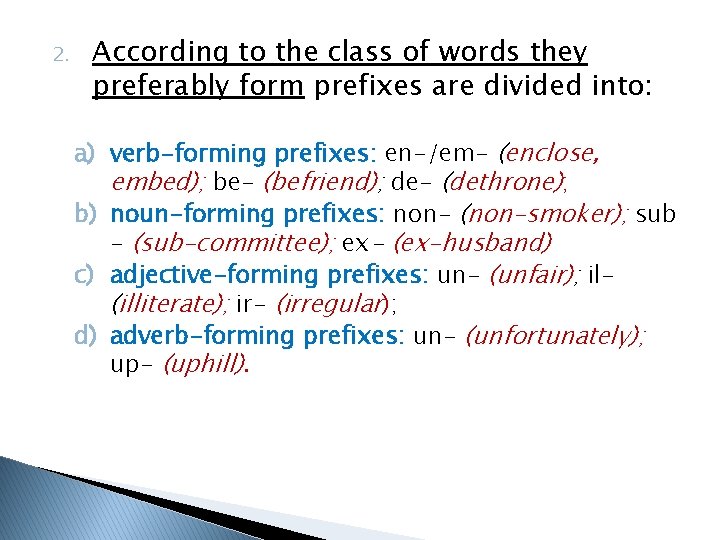

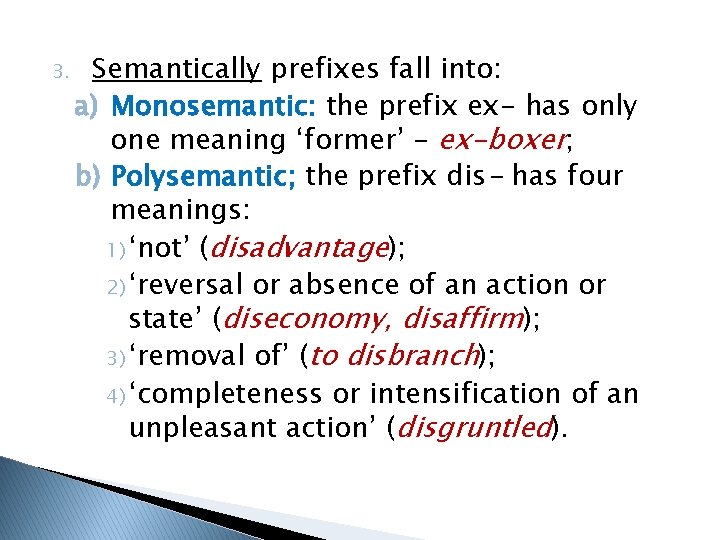

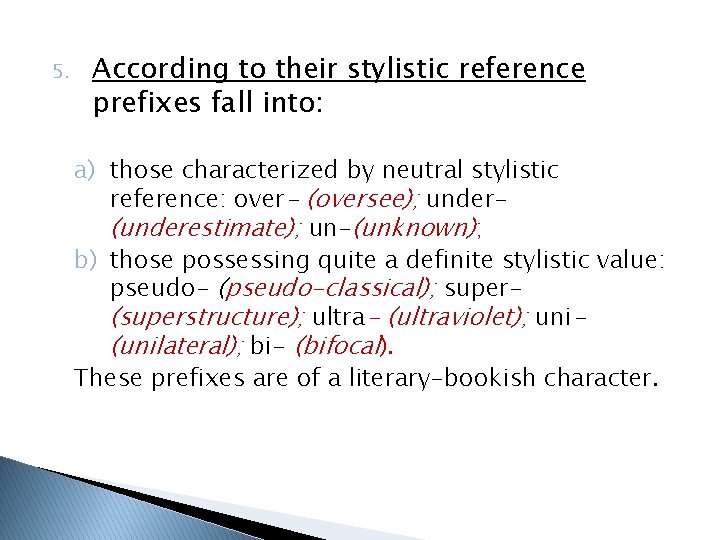

Prefixes may be classified on different principles: 3) meaning: negation (ungrateful, incorrect, disadvantage, etc. ); n time and order (foretell, foreknowledge, pre-war, post-war, etc. ); n repetition (rebuild, re-write, etc. ); n location (subway, inter-continental, etc. ), n quantity and intensity (bilingual, polytechnical), etc. n 4) stylistic reference: neutral stylistic reference (over-, re-, under-, etc. ); n with stylistic value (super-, ultra-, pseudo-, bi-, etc. ). n

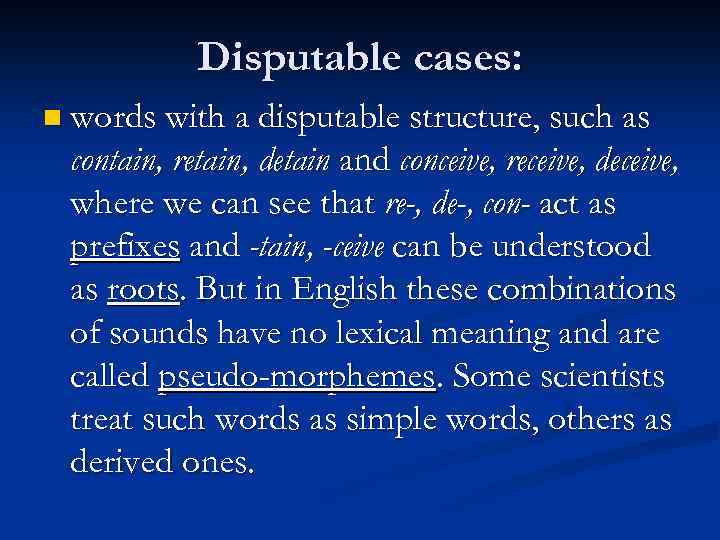

Disputable cases: n words with a disputable structure, such as contain, retain, detain and conceive, receive, deceive, where we can see that re-, de-, con- act as prefixes and -tain, -ceive can be understood as roots. But in English these combinations of sounds have no lexical meaning and are called pseudo-morphemes. Some scientists treat such words as simple words, others as derived ones.

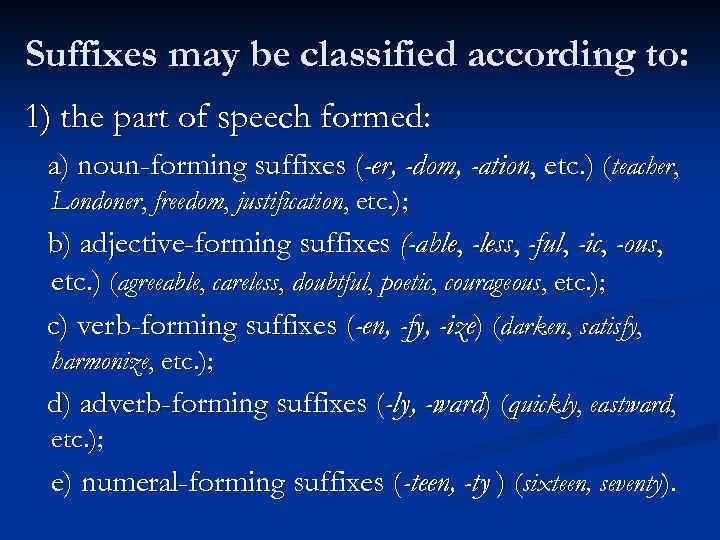

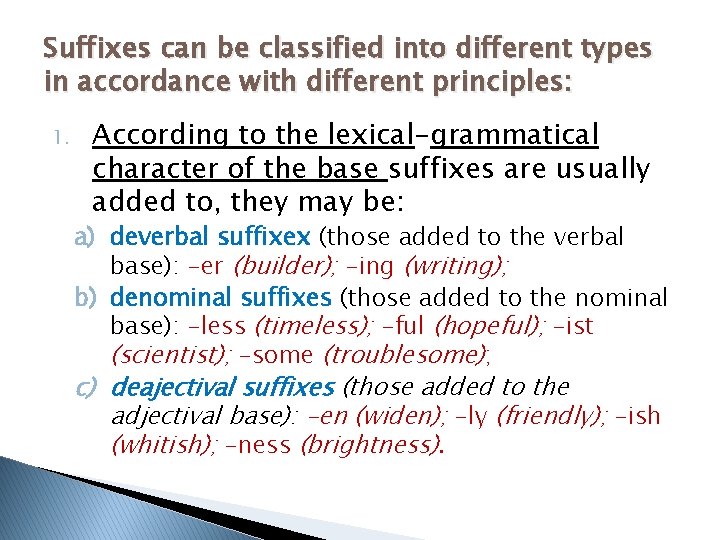

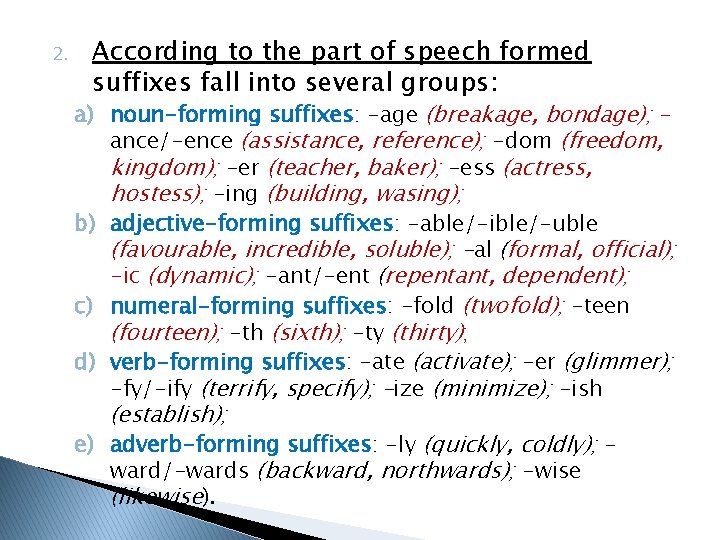

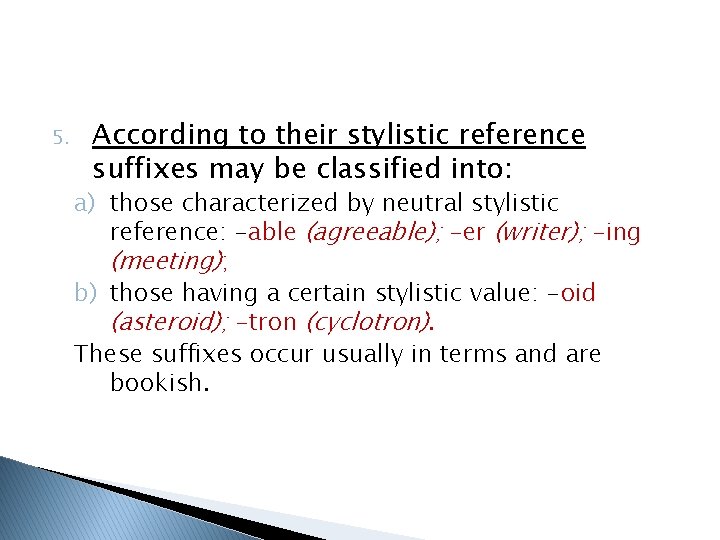

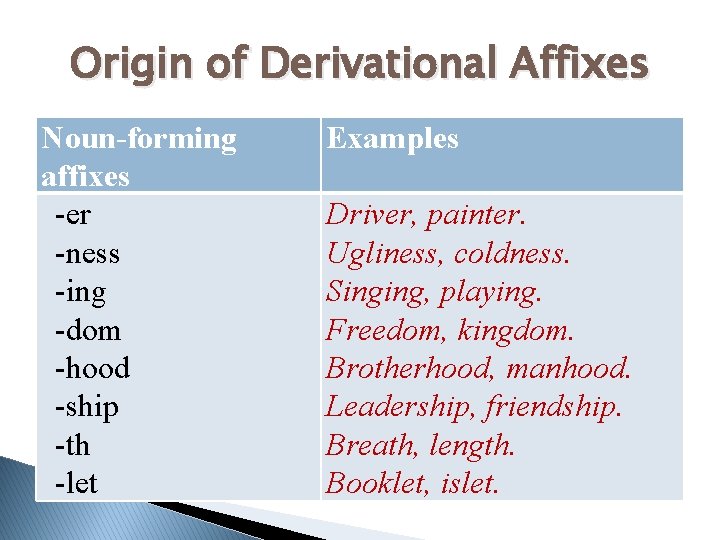

Suffixes may be classified according to: 1) the part of speech formed: a) noun-forming suffixes (-er, -dom, -ation, etc. ) (teacher, Londoner, freedom, justification, etc. ); b) adjective-forming suffixes (-able, -less, -ful, -ic, -ous, etc. ) (agreeable, careless, doubtful, poetic, courageous, etc. ); c) verb-forming suffixes (-en, -fy, -ize) (darken, satisfy, harmonize, etc. ); d) adverb-forming suffixes (-ly, -ward) (quickly, eastward, etc. ); e) numeral-forming suffixes (-teen, -ty ) (sixteen, seventy).

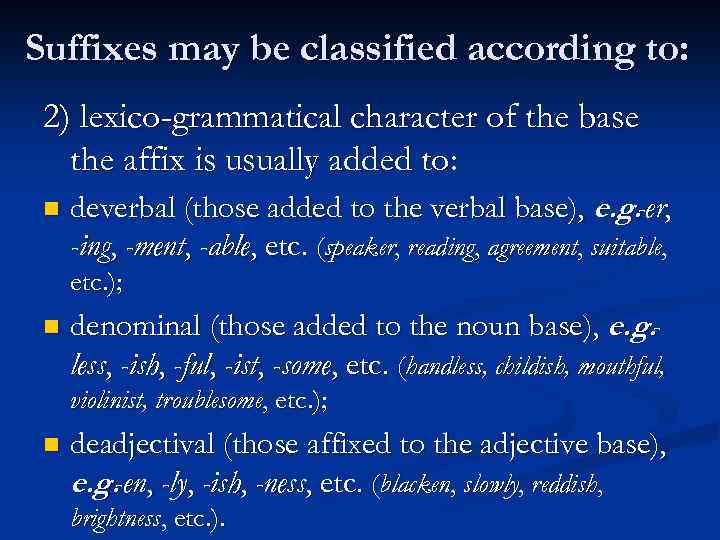

Suffixes may be classified according to: 2) lexico-grammatical character of the base the affix is usually added to: n deverbal (those added to the verbal base), e. g. -er, -ing, -ment, -able, etc. (speaker, reading, agreement, suitable, etc. ); n denominal (those added to the noun base), e. g. less, -ish, -ful, -ist, -some, etc. (handless, childish, mouthful, violinist, troublesome, etc. ); n deadjectival (those affixed to the adjective base), e. g. -en, -ly, -ish, -ness, etc. (blacken, slowly, reddish, brightness, etc. ).

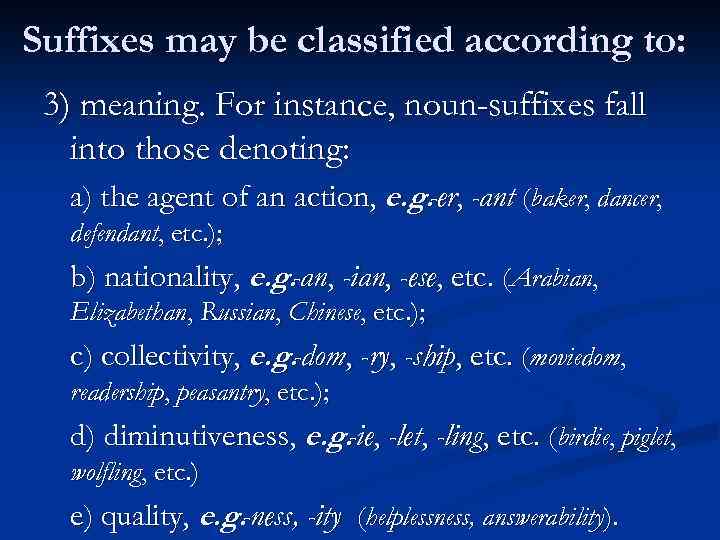

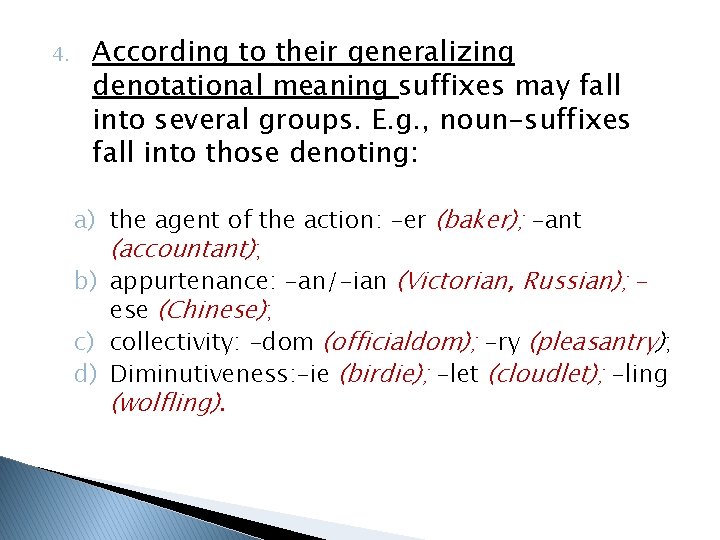

Suffixes may be classified according to: 3) meaning. For instance, noun-suffixes fall into those denoting: a) the agent of an action, e. g. -er, -ant (baker, dancer, defendant, etc. ); b) nationality, e. g. -an, -ian, -ese, etc. (Arabian, Elizabethan, Russian, Chinese, etc. ); c) collectivity, e. g. -dom, -ry, -ship, etc. (moviedom, readership, peasantry, etc. ); d) diminutiveness, e. g. -ie, -let, -ling, etc. (birdie, piglet, wolfling, etc. ) e) quality, e. g. -ness, -ity (helplessness, answerability).

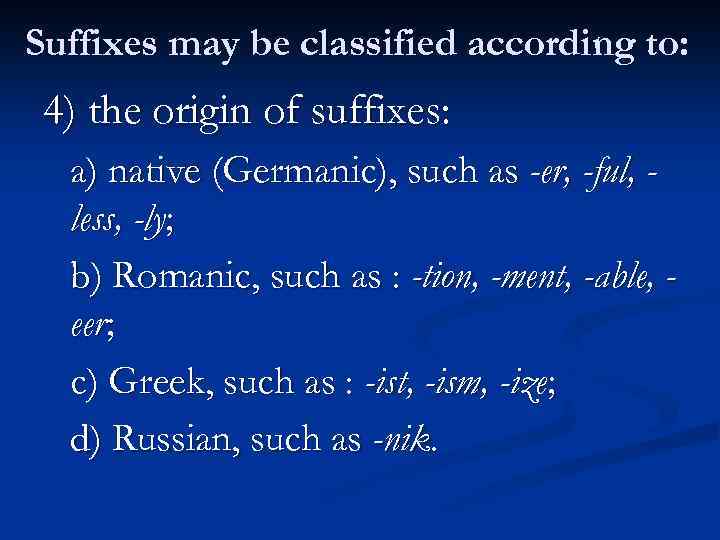

Suffixes may be classified according to: 4) the origin of suffixes: a) native (Germanic), such as -er, -ful, less, -ly; b) Romanic, such as : -tion, -ment, -able, eer; c) Greek, such as : -ist, -ism, -ize; d) Russian, such as -nik.

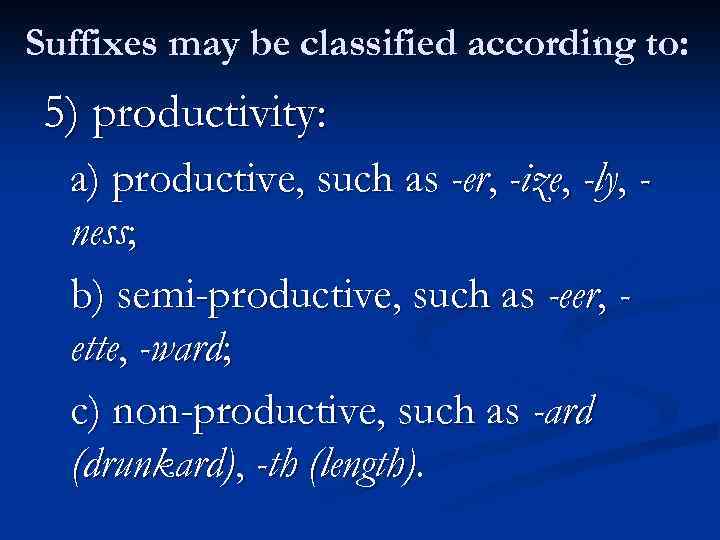

Suffixes may be classified according to: 5) productivity: a) productive, such as -er, -ize, -ly, ness; b) semi-productive, such as -eer, ette, -ward; c) non-productive, such as -ard (drunkard), -th (length).

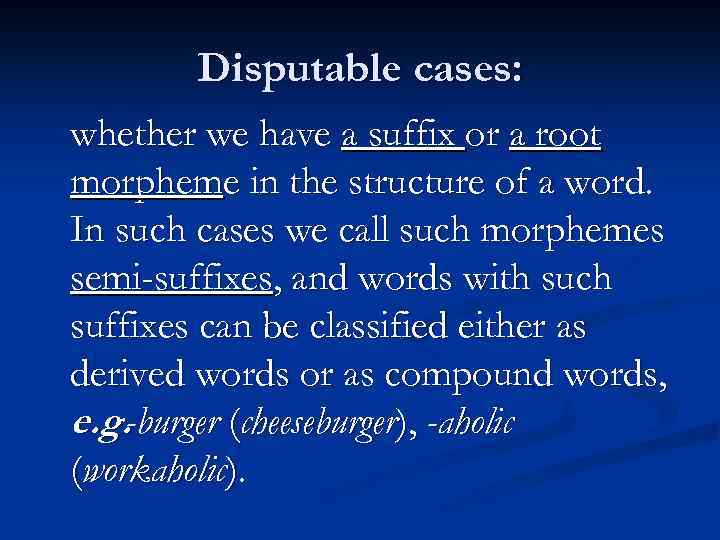

Disputable cases: whether we have a suffix or a root morpheme in the structure of a word. In such cases we call such morphemes semi-suffixes, and words with such suffixes can be classified either as derived words or as compound words, e. g. -burger (cheeseburger), -aholic (workaholic).

Conversion. Typical semantic relations. Productivity of conversion.

The term conversion was first mentioned by H. _______ in 1891.

Conversion: n a morphological way of forming words when one part of speech is formed from another part of speech by changing its ______ The morphological paradigms of the word eye n as a noun: eye — eyes n as a verb: to eye, eyes, eyed, will eye

The clearest cases of conversion are observed between verbs and nouns, and this term is now mostly used in this narrow sense.

Conversion is very active both in nouns for verb formation: doctor to doctor, shop to shop in verbs to form nouns: to smile a smite, to offer an offer).

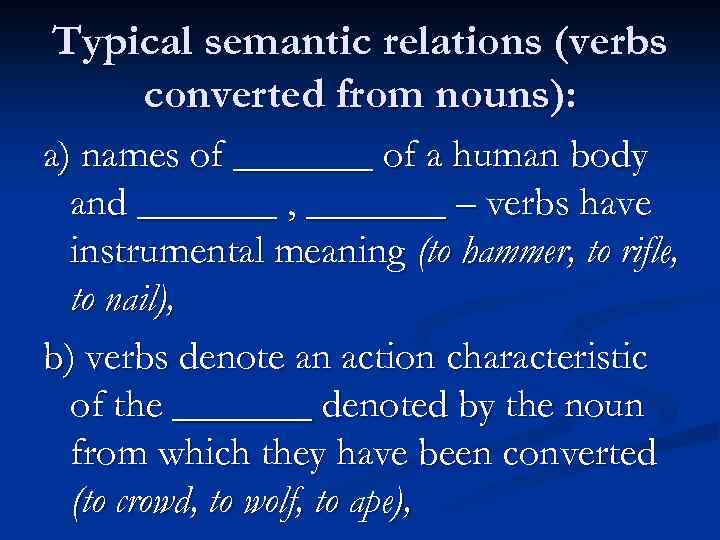

Typical semantic relations (verbs converted from nouns): a) names of _______ of a human body and _______ , _______ – verbs have instrumental meaning (to hammer, to rifle, to nail), b) verbs denote an action characteristic of the _______ denoted by the noun from which they have been converted (to crowd, to wolf, to ape),

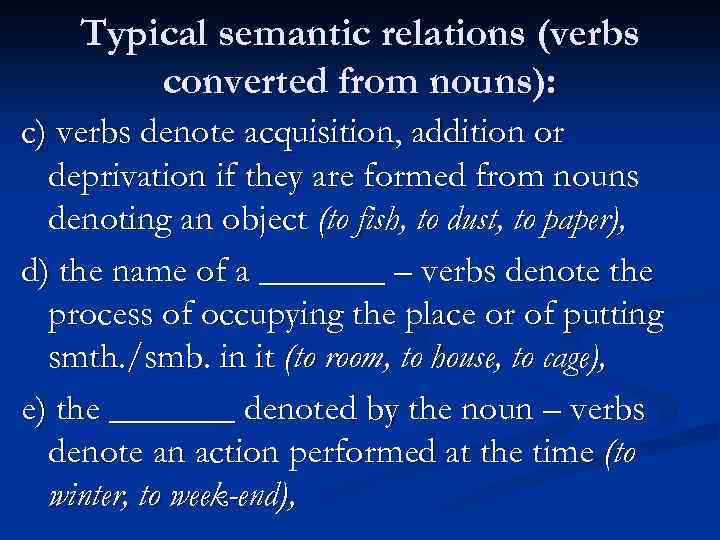

Typical semantic relations (verbs converted from nouns): c) verbs denote acquisition, addition or deprivation if they are formed from nouns denoting an object (to fish, to dust, to paper), d) the name of a _______ – verbs denote the process of occupying the place or of putting smth. /smb. in it (to room, to house, to cage), e) the _______ denoted by the noun – verbs denote an action performed at the time (to winter, to week-end),

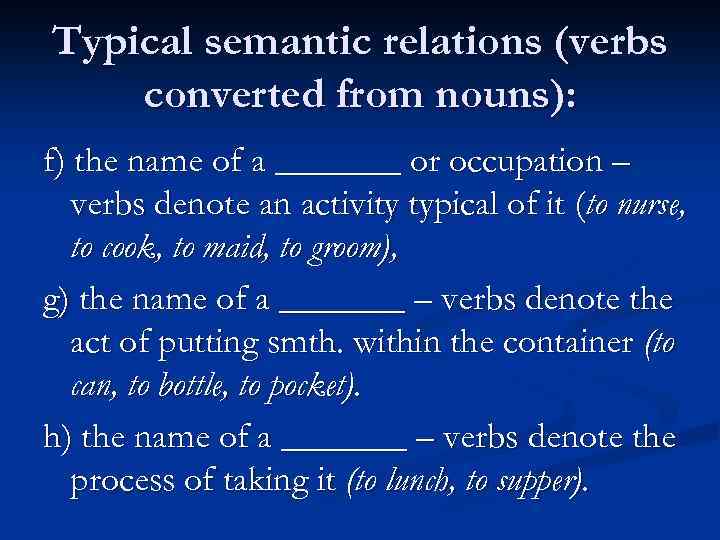

Typical semantic relations (verbs converted from nouns): f) the name of a _______ or occupation – verbs denote an activity typical of it (to nurse, to cook, to maid, to groom), g) the name of a _______ – verbs denote the act of putting smth. within the container (to can, to bottle, to pocket). h) the name of a _______ – verbs denote the process of taking it (to lunch, to supper).

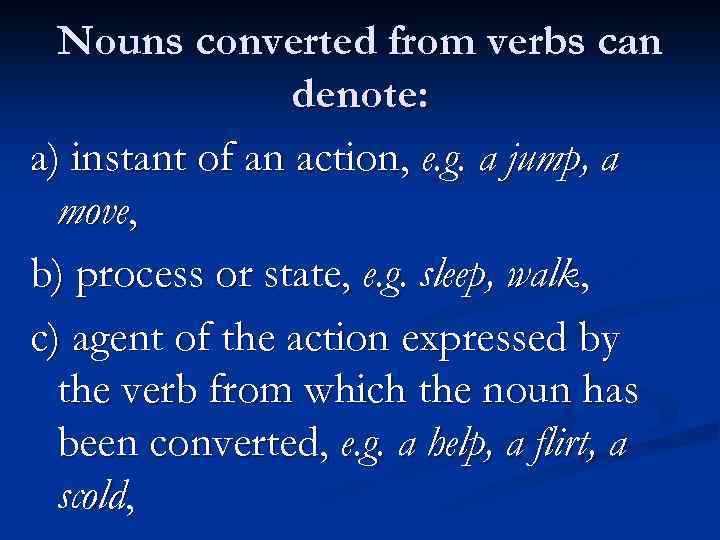

Nouns converted from verbs can denote: a) instant of an action, e. g. a jump, a move, b) process or state, e. g. sleep, walk, c) agent of the action expressed by the verb from which the noun has been converted, e. g. a help, a flirt, a scold,

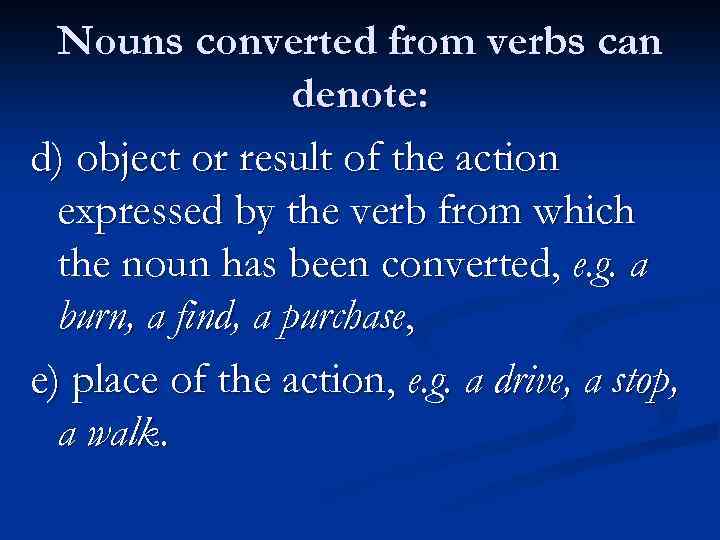

Nouns converted from verbs can denote: d) object or result of the action expressed by the verb from which the noun has been converted, e. g. a burn, a find, a purchase, e) place of the action, e. g. a drive, a stop, a walk.

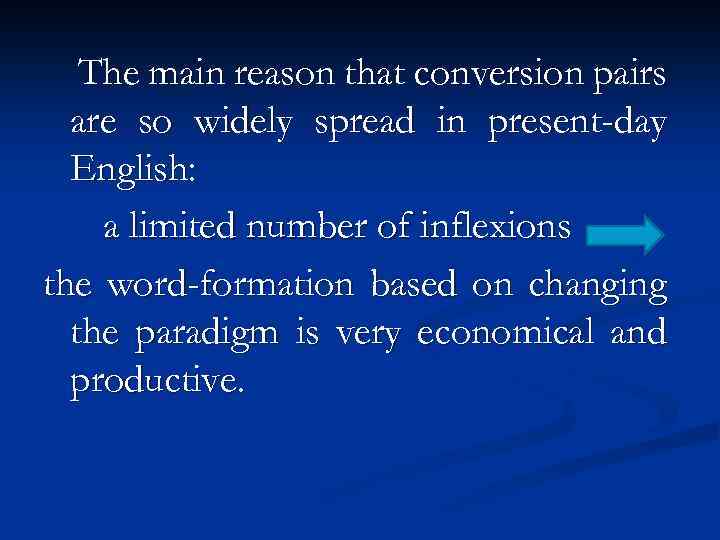

The main reason that conversion pairs are so widely spread in present-day English: a limited number of inflexions the word-formation based on changing the paradigm is very economical and productive.

Word-composition. Features of compoundwords. Classifications of compound-words.

Composition nthe way of word building when a word is formed by joining two or more _______ to form one word.

As English compounds consist of free forms, it is difficult to distinguish them from phrases.

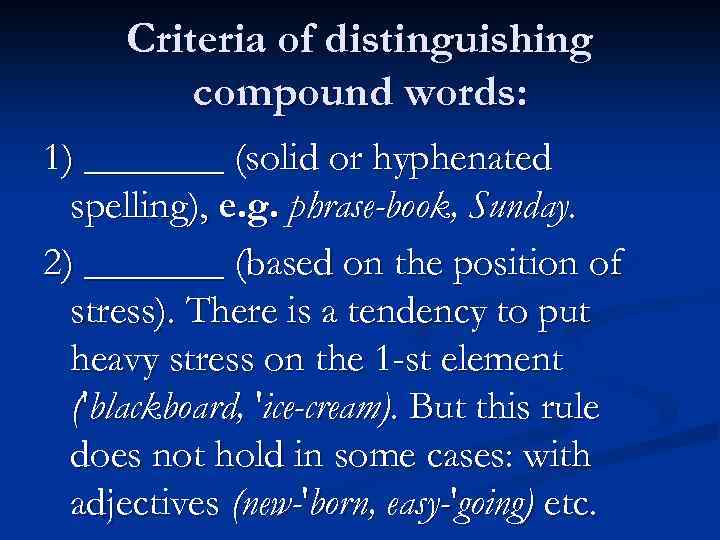

Criteria of distinguishing compound words: 1) _______ (solid or hyphenated spelling), e. g. phrase-book, Sunday. 2) _______ (based on the position of stress). There is a tendency to put heavy stress on the 1 -st element (‘blackboard, ‘ice-cream). But this rule does not hold in some cases: with adjectives (new-‘born, easy-‘going) etc.

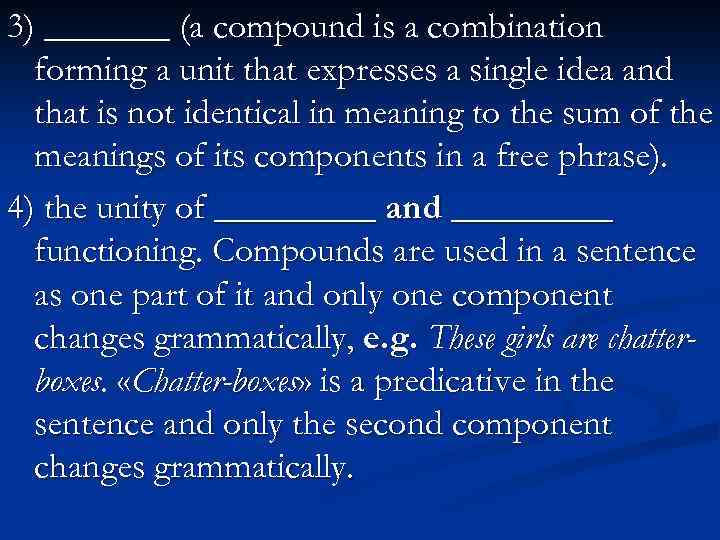

3) _______ (a compound is a combination forming a unit that expresses a single idea and that is not identical in meaning to the sum of the meanings of its components in a free phrase). 4) the unity of _____ and _____ functioning. Compounds are used in a sentence as one part of it and only one component changes grammatically, e. g. These girls are chatterboxes. «Chatter-boxes» is a predicative in the sentence and only the second component changes grammatically.

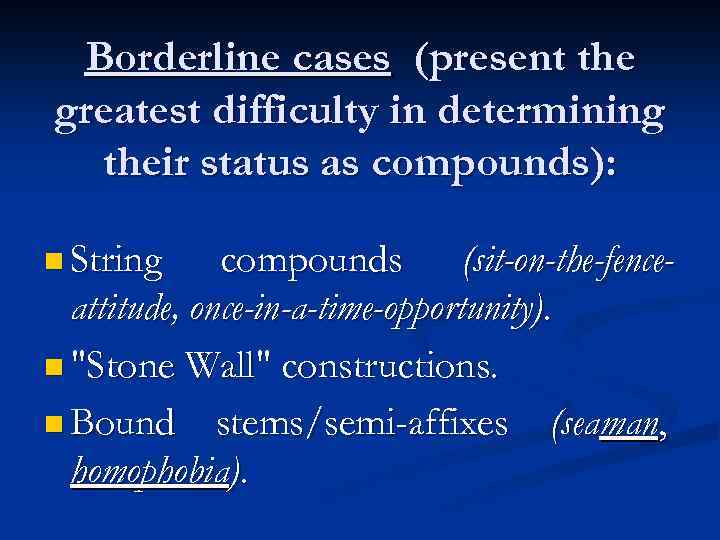

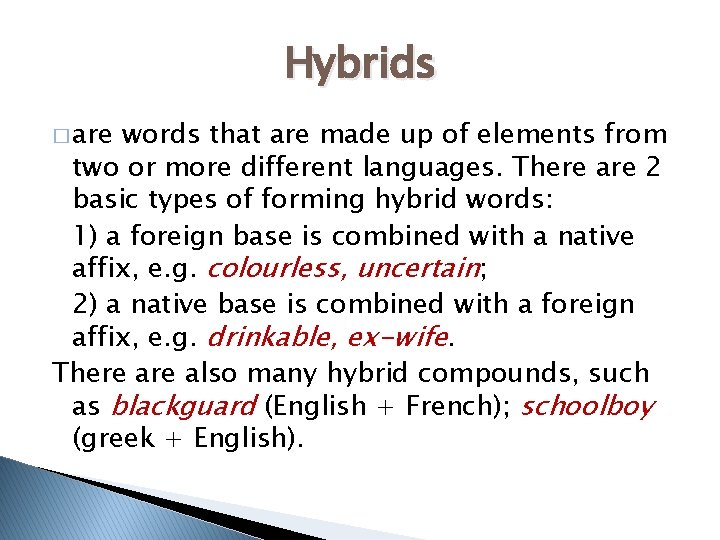

Borderline cases (present the greatest difficulty in determining their status as compounds): n String compounds (sit-on-the-fenceattitude, once-in-a-time-opportunity). n «Stone Wall» constructions. n Bound stems/semi-affixes (seaman, homophobia).

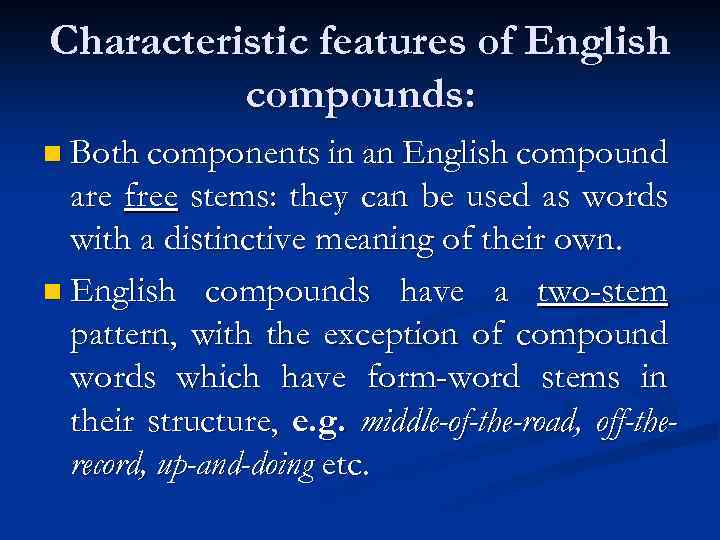

Characteristic features of English compounds: n Both components in an English compound are free stems: they can be used as words with a distinctive meaning of their own. n English compounds have a two-stem pattern, with the exception of compound words which have form-word stems in their structure, e. g. middle-of-the-road, off-therecord, up-and-doing etc.

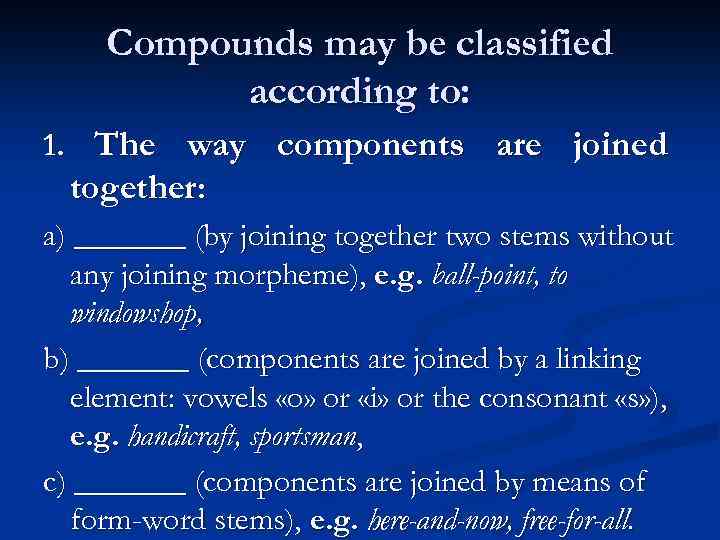

Compounds may be classified according to: 1. The way components are joined together: a) _______ (by joining together two stems without any joining morpheme), e. g. ball-point, to windowshop, b) _______ (components are joined by a linking element: vowels «o» or «i» or the consonant «s» ), e. g. handicraft, sportsman, c) _______ (components are joined by means of form-word stems), e. g. here-and-now, free-for-all.

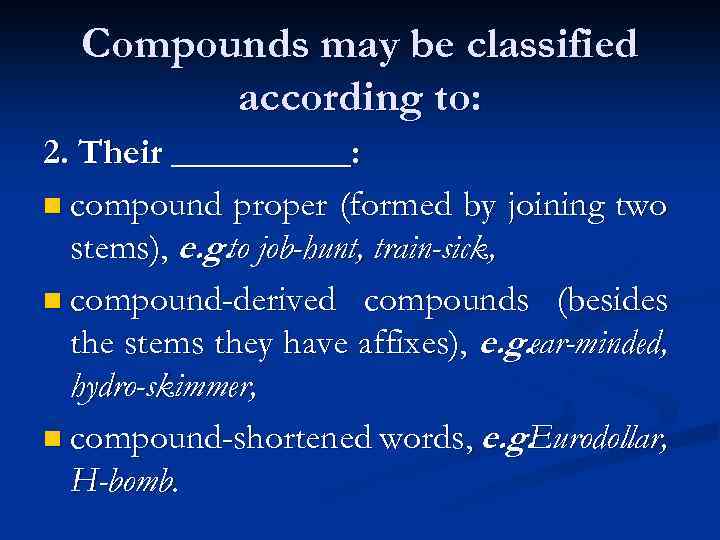

Compounds may be classified according to: 2. Their _____: n compound proper (formed by joining two stems), e. g. to job-hunt, train-sick, n compound-derived compounds (besides the stems they have affixes), e. g. ear-minded, hydro-skimmer, n compound-shortened words, e. g. Eurodollar, H-bomb.

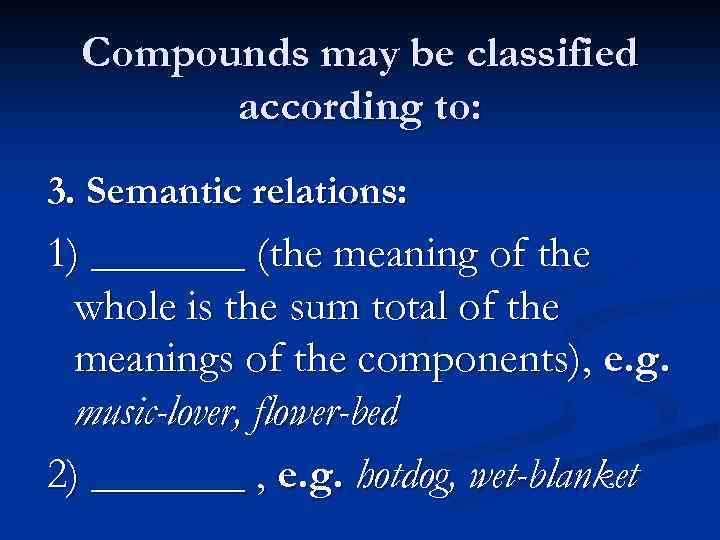

Compounds may be classified according to: 3. Semantic relations: 1) _______ (the meaning of the whole is the sum total of the meanings of the components), e. g. music-lover, flower-bed 2) _______ , e. g. hotdog, wet-blanket

5. Secondary types of word-formation

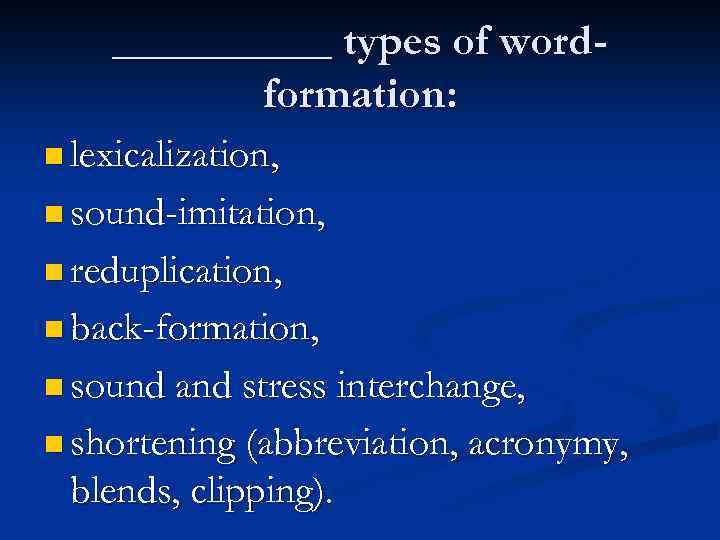

_____ types of wordformation: n lexicalization, n sound-imitation, n reduplication, n back-formation, n sound and stress interchange, n shortening (abbreviation, acronymy, blends, clipping).

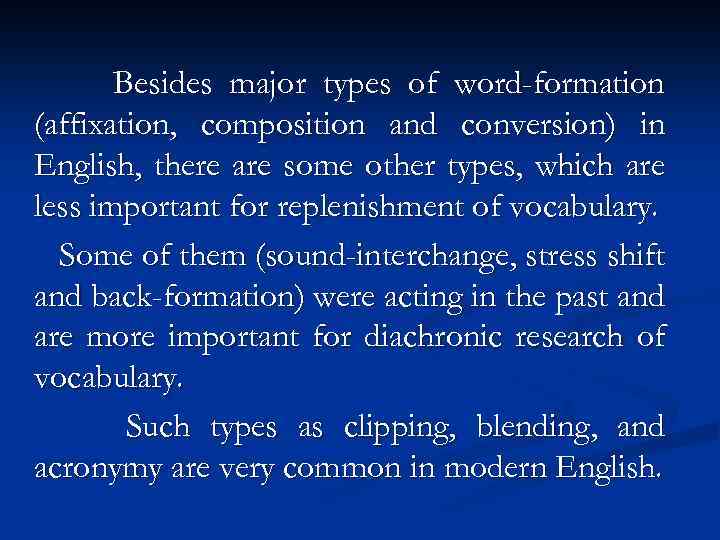

Besides major types of word-formation (affixation, composition and conversion) in English, there are some other types, which are less important for replenishment of vocabulary. Some of them (sound-interchange, stress shift and back-formation) were acting in the past and are more important for diachronic research of vocabulary. Such types as clipping, blending, and acronymy are very common in modern English.

Lexicalization: the process, when due to some semantic and syntactic reasons, the grammatical flexion in some word forms loses its _____ meaning and becomes isolated from the paradigm e. g. the plural of nouns like arms, colours of the words arm and colours. As the result these word forms (arms, colours) develop a different lexical meaning (arms = weapons and colours = flag) and become independent words. n

Sound-imitation: n the way of word-building when a word is formed by _______ different sounds. E. g. to whisper, to sneeze, to whistle, to buzz, to bark, to bubble.

Reduplication: n the way of word-formation within which new words are formed by _____ a stem, either without any phonetic changes or with a variation of the root-vowel or consonant. E. g. bye-bye, gee- gee, hush-hush, ping-pong, dilly-dally.

Back-formation: n the creation of new words by losing a _______ morpheme (babysitter to baby-sit, editor to edit, beggar to beg). It is opposite to suffixation, that is why it is called back-formation.

Sound-interchange n the creation of new words by changing the _____ (to breathe – breath, food – feed)

Stress-shift: n the process of forming new words by replacement of _______ from one syllable to another (‘import – to im’port, ‘record – to re’cord).

Types of Shortening: n substantivisation n acronyms and letter abbreviations n blends (сращения) n clippings (усечения)

Substantivisation: n is dropping of the final nominal member of a frequently used attributive word-group. The remaining adjective takes on the meaning and all syntactic functions of the noun and, in this way, develops into a new word. A number of nouns in English appeared in this way (documentary – a doc. film; finals – final examination; an editorial – an editorial article).

Abbreviation: na _____ form of a _____ word or a phrase used in a text in place of the whole for economy of space and effort.

Main types of shortenings: n _______ abbreviations (the result of shortening of words and word-groups only in written speech while orally the corresponding full forms are used. They are used for the economy of space and effort in writing), e. g. Mon — Monday, April, Mr. , Dr. n _______ abbreviations

Acronyms and letter abbreviations: Though the border-line between them is rather vague scholars make distinction between these 2 notions.

Letter abbreviations: n are mere replacements of longer phrases including names of well-known organizations, agencies, institutions, political parties, official offices. They are pronounced ______ and, as a rule, possess no linguistic forms proper to words (ITV = Independent Television; SST = Supersonic Transport)

Acronyms n are regular vocabulary units spoken as _______ (CLASS, yuppie). All acronyms, unlike letter abbreviations, perform the syntactic functions of ordinary words and can have grammatical inflexions. n Eg. : MP-MP’s-MPs

Acronyms may be formed in different ways: n from the initial letters or syllables of a phrase (NATO = North Atlantic Treaty Organization; UNO = United Nations Organization) n from the initial syllables of each word of a phrase (Interpol = international police)

Blends: n are words created when _______ and _______ segments of two words are joined together (smog = smoke + fog; brunch = breakfast + lunch).

Clipping: n is creation of new words by shortening a word of 2 or more _______ without changing its class membership (van = caravan, advantage (in tennis); dub = double; mike = microphone).

As a rule, lexical meanings of the clipped and the original word do not coincide. E. g. : Doc refers only to «sb. who practises medicine», while doctor denotes also «the higher degree given by a University, and a person who has received it» – Doctor of Philosophy, Doctor of Law).

Clippings fall into: n initial (van = advantage) n medial (specs = spectacles, maths = mathematics) n final (fan = fanatic)

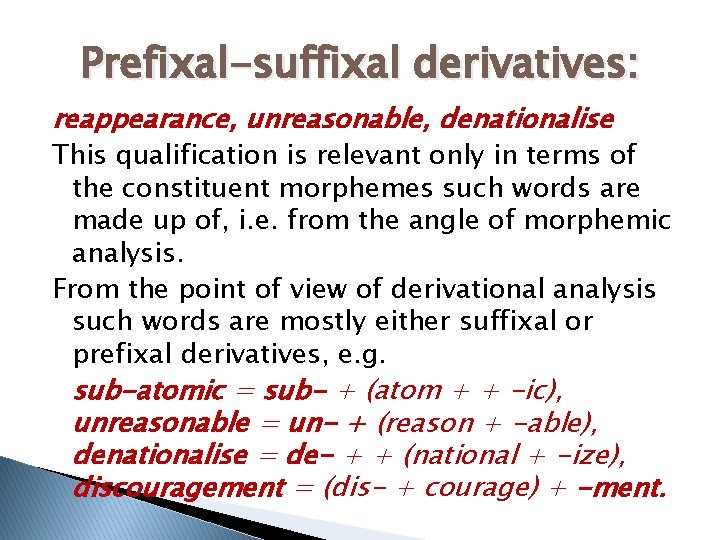

Types of Forming Words. Affixation. Lecture 10

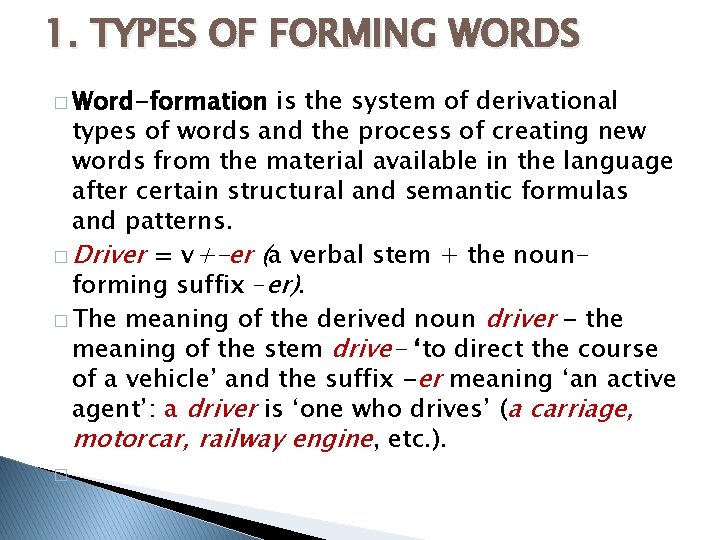

1. TYPES OF FORMING WORDS � Word-formation is the system of derivational types of words and the process of creating new words from the material available in the language after certain structural and semantic formulas and patterns. � Driver = v+-er (a verbal stem + the nounforming suffix –er). � The meaning of the derived noun driver — the meaning of the stem drive- ‘to direct the course of a vehicle’ and the suffix -er meaning ‘an active agent’: a driver is ‘one who drives’ (a carriage, motorcar, railway engine, etc. ). �

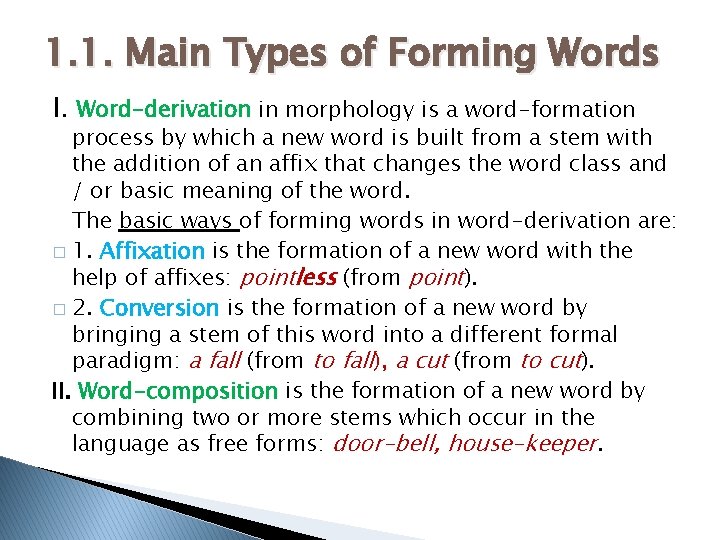

1. 1. Main Types of Forming Words I. Word-derivation in morphology is a word-formation process by which a new word is built from a stem with the addition of an affix that changes the word class and / or basic meaning of the word. The basic ways of forming words in word-derivation are: � 1. Affixation is the formation of a new word with the help of affixes: pointless (from point). � 2. Conversion is the formation of a new word by bringing a stem of this word into a different formal paradigm: a fall (from to fall), a cut (from to cut). II. Word-composition is the formation of a new word by combining two or more stems which occur in the language as free forms: door-bell, house-keeper.

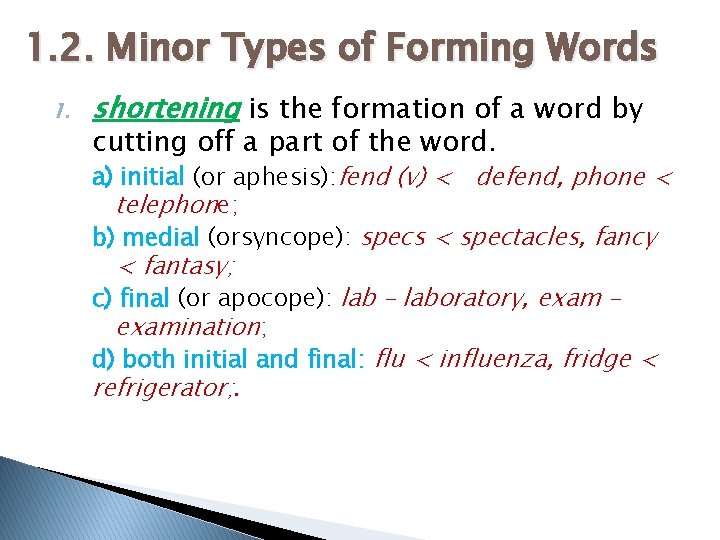

1. 2. Minor Types of Forming Words 1. shortening is the formation of a word by cutting off a part of the word. a) initial (or aphesis): fend (v) < defend, phone < telephone; b) medial (orsyncope): specs < spectacles, fancy < fantasy; c) final (or apocope): lab – laboratory, exam – examination; d) both initial and final: flu < influenza, fridge < refrigerator; .

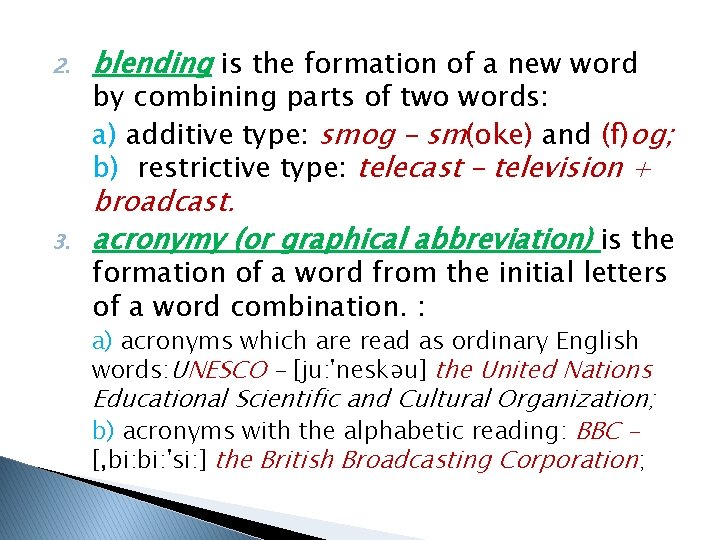

2. blending is the formation of a new word 3. broadcast. acronymy (or graphical abbreviation) is the by combining parts of two words: a) additive type: smog – sm(oke) and (f)og; b) restrictive type: telecast – television + formation of a word from the initial letters of a word combination. : a) acronyms which are read as ordinary English words: UNESCO – [ju: ‘neskəu] the United Nations Educational Scientific and Cultural Organization; b) acronyms with the alphabetic reading: BBC – [, bi: ‘si: ] the British Broadcasting Corporation;

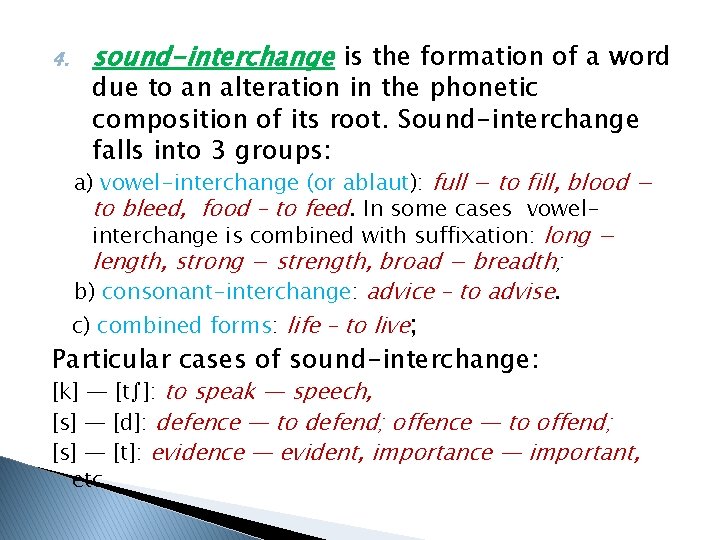

4. sound-interchange is the formation of a word due to an alteration in the phonetic composition of its root. Sound-interchange falls into 3 groups: a) vowel-interchange (or ablaut): full − to fill, blood − to bleed, food – to feed. In some cases vowelinterchange is combined with suffixation: long − length, strong − strength, broad − breadth; b) consonant-interchange: advice – to advise. c) combined forms: life – to live; Particular cases of sound-interchange: [k] — [t∫]: to speak — speech, [s] — [d]: defence — to defend; offence — to offend; [s] — [t]: evidence — evident, importance — important, etc.

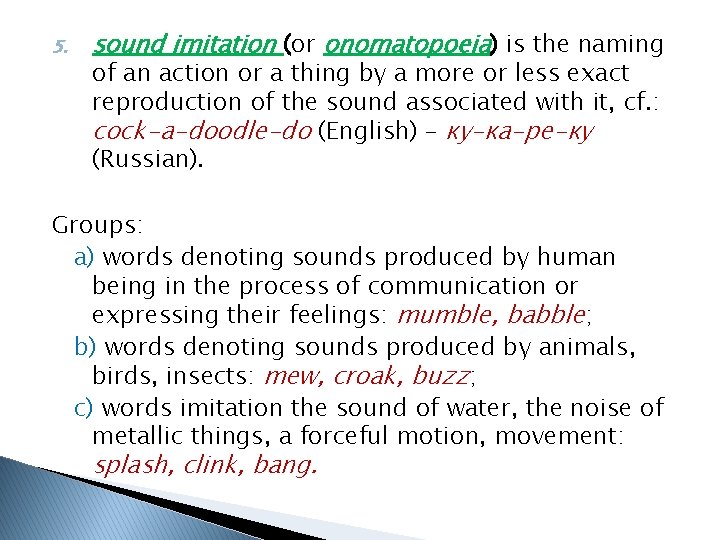

5. sound imitation (or onomatopoeia) is the naming of an action or a thing by a more or less exact reproduction of the sound associated with it, cf. : cock-a-doodle-do (English) – ку-ка-ре-ку (Russian). Groups: a) words denoting sounds produced by human being in the process of communication or expressing their feelings: mumble, babble; b) words denoting sounds produced by animals, birds, insects: mew, croak, buzz; c) words imitation the sound of water, the noise of metallic things, a forceful motion, movement: splash, clink, bang.

6. back-formation is the formation of a new word 7. distinctive stress is the formation of a new word by subtracting a real or supposed suffix from the existing words. The process is based on analogy: the word to butle ‘to act or serve as a butler’ is derived by subtraction of –er from a supposedly verbal stem in the noun butler; by means of the shift of the stress in the source word, cf. : export (n) — to ex´port; ´import (n) — to im´port; ‘

2. Word-formation as the Subject of Study � is that branch of Lexicology which studies the derivative structure of existing words and the patterns on which the English language, builds new words. Word-formation can deal only with words which are analysable both structurally and semantically, i. e. with all types of Complexes.

Word-formation may be studied: 1. 2. Synchronically – investigation of the existing system of the types of word-formation. The derived word is regarded as having a more complex structure than its correlated word regardless of the fact whether it was derived from a simpler base or a more complex base; Diachronically – chronological order of formation of one word from some other word that is relevant.

� In the history of the English language there are cases when a word structurally more complex served as the original element from which a simpler word was derived => back-formation (or back-derivation) : � cf. beggar — to beg; editor — to edit; chauffeur — to chauff � The fact that historically the verbs to beg, to edit, etc. were derived from the corresponding agent-nouns is of no synchronous relevance.

3. AFFIXATION � Affixation is the formation of words by adding derivational affixes to different types of bases. � An affix is not-root or a bound morpheme that modifies the meaning and / or syntactic category of the stem in some way. � Affixes are classified into prefixes and suffixes.

Degrees of Derivation 1. 2. 3. Zero — degree of derivation is ascribed to simple words, i. e. words whose stem is homonymous with a word-form and often with a root-morpheme, e. g. atom, haste, devote, anxious, horror, etc. First — derived words whose bases are built on simple stems and thus are formed by the application of one derivational affix, e. g. atomic, hasty, devotion, etc. Second — derived words formed by two consecutive stages of coining, e. g. atomical, hastily, devotional, etc.