The

development and change of the semantic structure of a word is always

a source of qualitative and quantitative development of the

vocabulary.

All

the types of semantic change depend upon comparison between the

earlier and the new meaning of the given word. This comparison may be

based on the difference between notions expressed or referents in the

real world that are pointed out, on the type of psychological

association, on evaluation by the speaker or on some other feature.

The

first diachronic classification of various types of semantic change

was introduced by M. Breal and H. Paul.

M. Breal was the first to emphasize the fact that in passing from

general usage into some special sphere of communication a word as a

rule undergoes some sort of specialization of its meaning. The word

case, for instance, alongside its general meaning of “circumstances

in which a person or thing is possesses special meanings”: in law

(a lawsuit), in grammar (e.g. the Possessive case), in medicine (a

patient, an illness).

The

difference is revealed in contexts, in which these words occur, in

their different valency. Words connected with illness and medicine

and words connected with law and court procedures form the semantic

paradigm of the word case. The same applies to the noun cell as used

by a biologist, an electrician, a nun or a representative of the law.

The

best-known examples of specialization are the following:

Deer:

any beast> a certain kind of beast

Meat:

any food> a certain food product

Fowl:

any bird> domestic bird

Hound:

a dog> a species of hunting dog

A

special group belonging to the same type is the formation of proper

nouns from common nouns chiefly in toponymics,

i.e. place names. For instance, the City – the business part of

London, the Highlands – the mountainous part of Scotland, Oxford –

University town in England from ox + ford, i.e. place where oxen

could ford the river, the Tower – originally a fortress and palace,

later a state prison, now a museum.

In

the examples the change of meaning occurred without change of sound

form and without any intervention of morphological processes. In many

cases, however, the

two processes, semantic and morphological,

go hand in hand. For instance, when suffix –ist is added to the

noun stem art- we must expect the whole to mean any person occupied

in art, a representative of any kind of art, but usage specializes

the meaning of the word artist and restricts it to a synonym of

painter.

The

process reverse to specialization is termed generalization or

widening of meaning. In

that case the scope of the new notion is wider than that of the

original one. For instance, the verb to arrive (French borrowing)

began its life in English in the narrow meaning “to come to shore,

to land”. In Modern English it has greatly widened its

combinability and developed the general meaning “to come”.

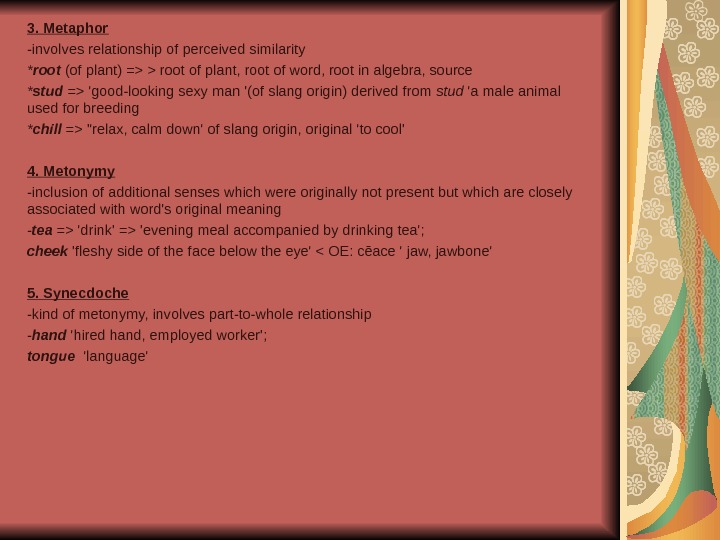

Metaphor

A

metaphor is a transfer of name based on the association of

similarity. Metaphor is a hidden comparison. A new meaning appears as

a result of associating two objects (phenomena, qualities, etc) due

to their outward similarity. A cunning person, for instance is

referred to as a fox. A woman may be called a peach, a lemon, a cat,

a goose, etc. The noun star based on the meaning “heavenly body”

developed the meaning “famous actor or actress”. Nowadays the

meaning has considerably widened its range, and the word is applied

not only to screen idols, but also, to popular sportsmen,

pop-singers.

Соседние файлы в предмете Лексикология

- #

- #

- #

Semantics refers to the study of meaning. There are two types of semantics: logical and lexical. Logical semantics is the study of reference (the symbolic relationship between language and real-world objects) and implication (the relationship between two sentences). Lexical semantics is the analysis of word meaning.

What is semantic change?

The term semantic change refers to how the meaning of words changes over time. We will cover five types of semantic change: narrowing, broadening, amelioration, pejoration, and semantic reclamation.

Let’s learn about the causes of semantic change, the different types of semantic change, and look at some examples.

The term ‘semantic shift’ can also be used to refer to the changing meanings of words.

The nature of semantic change

It is important to remember that the nature of semantic change is a gradual process. The meaning of a word doesn’t just change in an instant, it can take many years.

Semantic change often occurs as societal values change. This means that different social or ethnic groups may experience semantic change differently for different words.

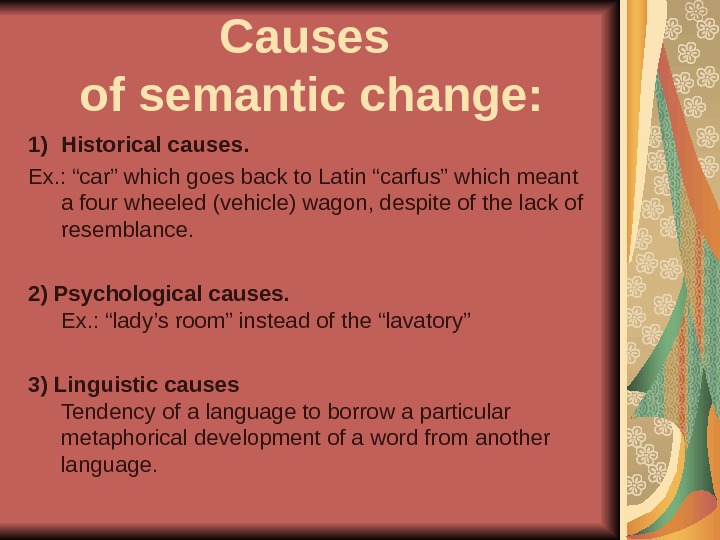

Causes of semantic change

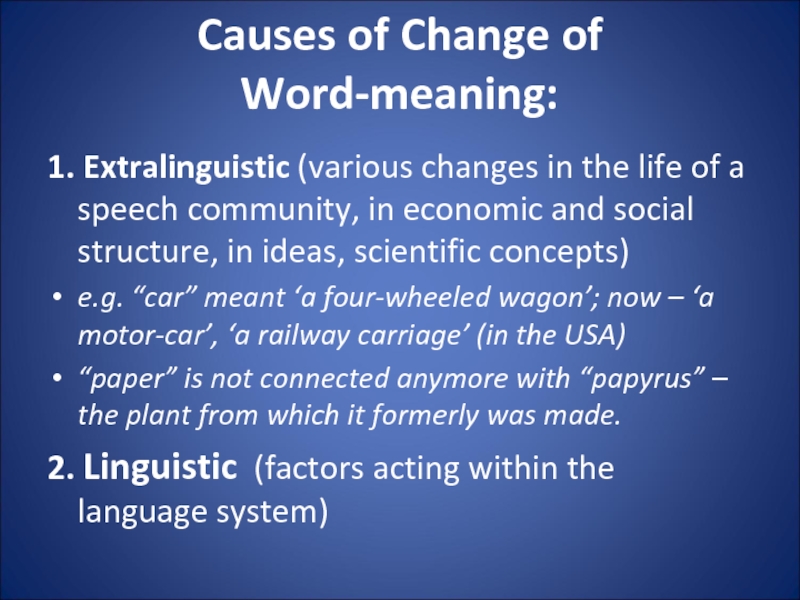

There are two different causes of semantic change. These are extralinguistic causes (not involving language) and linguistic causes (involving language).

Extralinguistic causes

Extralinguistic causes in semantic change are mainly to do with the social or historical causes of semantic change. If we break the term ‘extralinguistic’ down we can see that it refers to factors that are ‘extra’ so exist outside the language itself. Linguist Andreas Blank breaks down this factor into three main subcategories.

1. Psychological factors

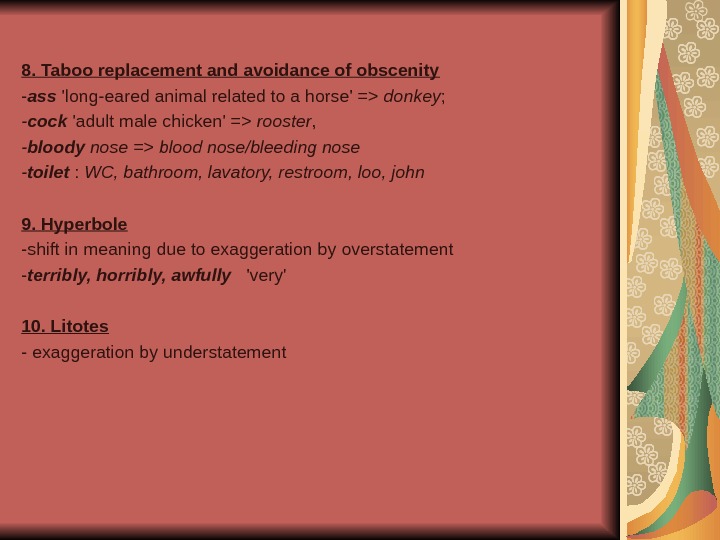

Psychological factors are factors that affect how people view a word and its meaning. If a word’s original meaning is unclear, it is given new meaning. The meaning of a word may also become taboo or is used as a euphemism, eg. the term ‘pass away’ can be used to describe someone dying.

2. Sociocultural factors

This is perhaps the most common factor for extralinguistic causes of semantic change. Changes in the social, economical or political status of a country can have a significant impact on semantics. An example of this is how the meaning of words changed following the Industrial Revolution e.g. the meaning of the word ‘engine’ changed from describing general devices used in war to describing a specific mechanical device. This means that the word went the semantic change (more specifically narrowing).

3. Cultural/encyclopaedic factors

These factors refer to the cultural reasons why a word’s meaning may change. This can be because of cultural changes that lead to a change in how the word is categorised (causing a semantic change). For example, the word ‘cool’ was originally used in the context of jazz music but as the popularity of jazz increased, the word became associated with anything trendy.

| Extralinguistic causes |

| The fuzziness of a meaning |

| Cultural importance changes |

| Word becomes taboo |

| Change in a word’s popularity |

| Communicative changes |

| Changes in worldview |

Linguistic causes

Linguistic causes of semantic change are factors that occur within the system of the language spoken. Natural language changes tend to take longer than extralinguistic causes. We see this throughout history, for example, Old English took centuries to develop into Middle English.

Linguistic factors can include:

Metonymy

Metonymy occurs when the name of an object is substituted for an attribute or adjective. For example, sometimes when discussing horse racing, the tracks are referred to as ‘turf’.

Metaphors

Metaphors may also affect what certain words are associated with. The meaning words may be extended to show a connection between two similar things.

Ellipsis

This occurs when two words are consistently used together in a sentence until they acquire the same meaning. For example, the verb ‘to starve’ originally meant ‘to die’; however, it was frequently used in sentences about hunger. This led to the word’s meaning to die of hunger.

There are factors within these causes that will also impact semantic changes. Have a look at the table below to see some examples of extralinguistic and linguistic causes of semantic change.

| Linguistic causes |

| Metonymy / metaphor |

| Ellipses |

| Changes in the referents (what is being referred to) |

| Excessive length |

| Wordplay and puns |

| Disguising language / misnomers (i.e. an inaccurate name) |

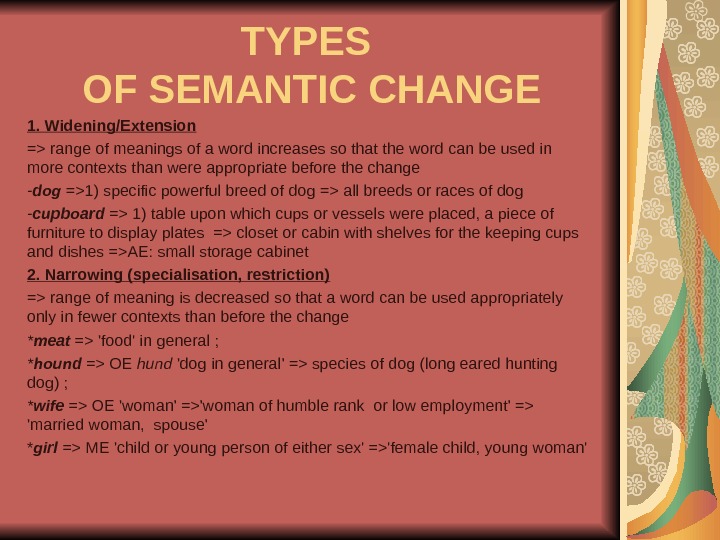

Different types of semantic change

There are five major types of semantic change. These changes occur for either extralinguistic or linguistic reasons. The five major kinds of semantic change are: narrowing, broadening, amelioration, pejoration, and semantic reclamation.

Below, we will discuss the characteristics of these, and look at examples of each type of semantic change.

Narrowing

Semantic narrowing is the process by which a word’s meaning becomes less generalised (in other words more specific) over time. This means that the new meaning derives directly from the original meaning. Typically this process is caused by linguistic factors, such as ellipses, and can take many years to occur. Narrowing can also be referred to as semantic specialisation or semantic restriction.

Let’s look at two examples of semantic narrowing:

Hound

The word ‘hound’, traditionally was used to refer to any type of dog. However, over the centuries the meaning narrowed until it was only used when discussing dogs used when hunting (such as beagles and bloodhounds).

Meat

Similarly, ‘meat’, has also undergone semantic narrowing over the years. The word originally just meant ‘food’. This meaning grew more specific until the word ‘meat’ was only used when relating to one type of food (animal flesh).

Broadening

Broadening is the process in which the meaning of a word becomes more generalised over time. In order words, the word can be used in more contexts than it could originally. This is sometimes referred to as semantic generalisation.

Semantic broadening is the antonym of semantic narrowing, as the process that takes place is the opposite. However, like semantic narrowing, this process often occurs over the course of many years. Broadening can be caused by both extralinguistic and linguistic causes, such as a change in worldview, or linguistic analogy.

Below are two examples of semantic broadening:

Business

The word, ‘business’ originally was only used to refer to being busy. However, over the years, the meaning of this word broadened to refer to any type of work or job.

Cool

The term, ‘cool’, was popular within the language of jazz musicians, as it referred to a specific style of music (‘cool jazz’)! Over time, as jazz music grew in popularity, the word started to be used in other contexts.

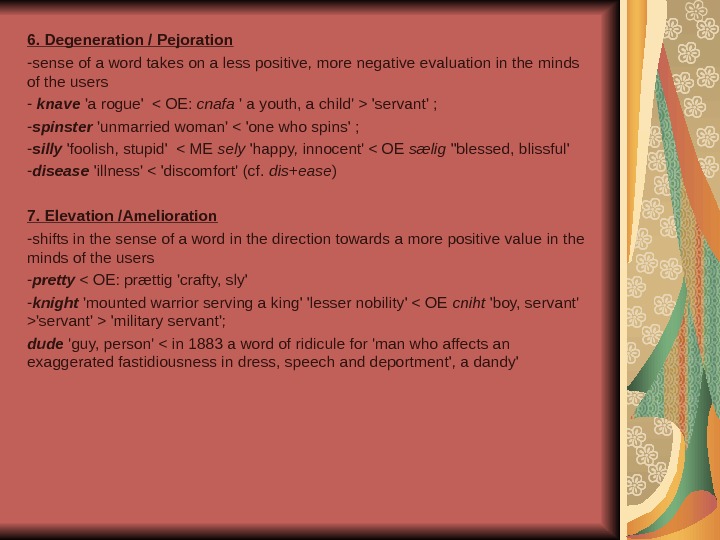

Amelioration

Amelioration is a term that refers to when a word acquires a more positive meaning over time. It may also be referred to as semantic amelioration or semantic elevation. Typically this process occurs due to different extralinguistic reasons, such as cultural and worldview changes occurring.

The word ‘nice’ is possibly the most well-known example of amelioration. In the 1300s, the word originally meant that a person was foolish or silly. However, by the 1800s, the process of amelioration had changed this, and the word came to mean that someone was kind and thoughtful. From this, we can see that amelioration is a process that can take centuries to occur.

Sick

Many slang terms, such as ‘sick’, have undergone the process of amelioration over the years. Terms such as ‘sick’ or ‘wicked’ now also have positive connotations. This is because when used as slang, they gain a new, positive, meaning and are associated with the word, ‘cool’.

Pejoration

Pejoration is a term used to describe the process where a word that once had a positive meaning acquires a negative one. It is sometimes also referred to as semantic deterioration. This type of semantic change usually occurs due to extralinguistic causes. This can include a word becoming taboo, or being linked with a taboo within the culture.

Below, we will look at two different examples of pejoration:

Silly

The word, ‘silly’, is a common example of pejoration. In Old and Middle English, the term was used to mean that someone was happy, or spiritually blessed. However, over the centuries, this changed and by the 1500s, the word became associated with acting foolishly — as it is today!

Attitude

This word was originally used to refer to someone’s pose or posture. The meaning of the word changed, referring to someone’s way of thinking instead. From this, the term began to be used colloquially which led it to be associated with acting rude or unkind. A phrase such as ‘he has a bad attitude’ can become shortened to ‘he has an attitude’, showing that the word has gained a negative meaning.

Semantic change: reclamation

Semantic reclamation occurs when a group of people who have been oppressed reclaim (or take back) a word that has been used in the past to disparage them. The people who reclaim these words use them in a positive context and in doing this, the word is stripped of its power to disparage the group.

Semantic reclamation is often a political and controversial act, as these words become special to one particular group. Words have been reclaimed by groups such as women, ethnic minorities and the LGBTQIA community.

It is important to remember when discussing this form of semantic change that, unlike amelioration, the word may still also be used in the pejorative sense.

Words that have undergone semantic change

We’ve discussed examples of the different types of semantic change. However, here are a few more interesting examples that show the change of the English language over time!

- Girl (narrowing)- originally referred to a child of either gender. The meaning narrowed to refer to a female child.

- Playdough (broadening)- was originally the brand name. The meaning broadened to refer to the product as well.

- Fun (amelioration)- originally had negative connotations meaning ‘to cheat or trick’. The meaning now has positive connotations of amusement.

- Stench (pejoration)- originally meant ‘smell, odour, or fragrance’. The meaning now has negative connotations of a bad or unpleasant smell.

Semantic Change — Key Takeaways

- Semantic change refers to a type of language change in which the meaning of a word changes over time. Semantic change can be caused by extralinguistic and linguistic factors.

- Narrowing is when a word’s meaning becomes more specialised in time.

- Broadening is when a word becomes more generalised and gains additional meanings.

- Amelioration is when a word’s meaning changes from negative to positive.

- Pejoration is when a word’s meaning changes from positive to negative.

- Semantic reclamation is a process where a word that was once used to disparage a group of people is reclaimed by the group.

- Размер: 288.5 Кб

- Количество слайдов: 30

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

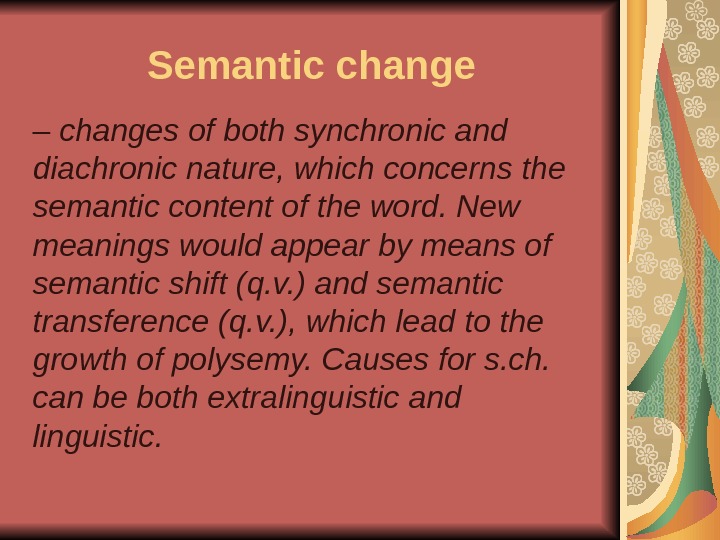

Semantic change (also semantic shift, semantic progression, semantic development, or semantic drift) is a form of language change regarding the evolution of word usage—usually to the point that the modern meaning is radically different from the original usage. In diachronic (or historical) linguistics, semantic change is a change in one of the meanings of a word. Every word has a variety of senses and connotations, which can be added, removed, or altered over time, often to the extent that cognates across space and time have very different meanings. The study of semantic change can be seen as part of etymology, onomasiology, semasiology, and semantics.

Examples in English[edit]

- Awful — Literally «full of awe», originally meant «inspiring wonder (or fear)», hence «impressive». In contemporary usage, the word means «extremely bad».

- Awesome — Literally «awe-inducing», originally meant «inspiring wonder (or fear)», hence «impressive». In contemporary usage, the word means «extremely good».

- Terrible — Originally meant «inspiring terror», shifted to indicate anything spectacular, then to something spectacularly bad.

- Terrific — Originally meant «inspiring terror», shifted to indicate anything spectacular, then to something spectacularly good.[1]

- Nice — Originally meant «foolish, ignorant, frivolous, senseless.» from Old French nice (12c.) meaning «careless, clumsy; weak; poor, needy; simple, stupid, silly, foolish,» from Latin nescius («ignorant or unaware»). Literally «not-knowing,» from ne- «not» (from PIE root *ne- «not») + stem of scire «to know» (compare with science). «The sense development has been extraordinary, even for an adj.» [Weekley] — from «timid, faint-hearted» (pre-1300); to «fussy, fastidious» (late 14c.); to «dainty, delicate» (c. 1400); to «precise, careful» (1500s, preserved in such terms as a nice distinction and nice and early); to «agreeable, delightful» (1769); to «kind, thoughtful» (1830).

- Naïf or Naïve —Initially meant «natural, primitive, or native» . From French naïf, literally «native«. The masculine form of the French word, but used in English without reference to gender. As a noun, «natural, artless, naive person,» first attested 1893, from French, where Old French naif also meant «native inhabitant; simpleton, natural fool.»

- Demagogue — Originally meant «a popular leader». It is from the Greek dēmagōgós «leader of the people», from dēmos «people» + agōgós «leading, guiding». Now the word has strong connotations of a politician who panders to emotions and prejudice.

- Egregious — Originally described something that was remarkably good (as in Theorema Egregium). The word is from the Latin egregius «illustrious, select», literally, «standing out from the flock», which is from ex—»out of» + greg—(grex) «flock». Now it means something that is remarkably bad or flagrant.

- Gay — Originally meant (13th century) «lighthearted», «joyous» or (14th century) «bright and showy», it also came to mean «happy»; it acquired connotations of immorality as early as 1637, either sexual e.g., gay woman «prostitute», gay man «womaniser», gay house «brothel», or otherwise, e.g., gay dog «over-indulgent man» and gay deceiver «deceitful and lecherous». In the United States by 1897 the expression gay cat referred to a hobo, especially a younger hobo in the company of an older one; by 1935, it was used in prison slang for a homosexual boy; and by 1951, and clipped to gay, referred to homosexuals. George Chauncey, in his book Gay New York, would put this shift as early as the late 19th century among a certain «in crowd», knowledgeable of gay night-life. In the modern day, it is most often used to refer to homosexuals, at first among themselves and then in society at large, with a neutral connotation; or as a derogatory synonym for «silly», «dumb», or «boring».[2]

- Guy — Guy Fawkes was the alleged leader of a plot to blow up the English Houses of Parliament on 5 November 1605. The day was made a holiday, Guy Fawkes Day, commemorated by parading and burning a ragged manikin of Fawkes, known as a Guy. This led to the use of the word guy as a term for any «person of grotesque appearance» and then by the late 1800s—especially in the United States—for «any man», as in, e.g., «Some guy called for you.» Over the 20th century, guy has replaced fellow in the U.S., and, under the influence of American popular culture, has been gradually replacing fellow, bloke, chap and other such words throughout the rest of the English-speaking world. In the plural, it can refer to a mixture of genders (e.g., «Come on, you guys!» could be directed to a group of mixed gender instead of only men).

Evolution of types[edit]

A number of classification schemes have been suggested for semantic change.

Recent overviews have been presented by Blank[3] and Blank & Koch (1999). Semantic change has attracted academic discussions since ancient times, although the first major works emerged in the 19th century with Reisig (1839), Paul (1880), and Darmesteter (1887).[4] Studies beyond the analysis of single words have been started with the word-field analyses of Trier (1931), who claimed that every semantic change of a word would also affect all other words in a lexical field.[5] His approach was later refined by Coseriu (1964). Fritz (1974) introduced Generative semantics. More recent works including pragmatic and cognitive theories are those in Warren (1992), Dirk Geeraerts,[6] Traugott (1990) and Blank (1997).

A chronological list of typologies is presented below. Today, the most currently used typologies are those by Bloomfield (1933) and Blank (1999).

Typology by Reisig (1839)[edit]

Reisig’s ideas for a classification were published posthumously. He resorts to classical rhetorics and distinguishes between

- Synecdoche: shifts between part and whole

- Metonymy: shifts between cause and effect

- Metaphor

Typology by Paul (1880)[edit]

- Generalization: enlargement of single senses of a word’s meaning

- Specialization on a specific part of the contents: reduction of single senses of a word’s meaning

- Transfer on a notion linked to the based notion in a spatial, temporal, or causal way

Typology by Darmesteter (1887)[edit]

- Metaphor

- Metonymy

- Narrowing of meaning

- Widening of meaning

The last two are defined as change between whole and part, which would today be rendered as synecdoche.

Typology by Bréal (1899)[edit]

- Restriction of sense: change from a general to a special meaning

- Enlargement of sense: change from a special to a general meaning

- Metaphor

- «Thickening» of sense: change from an abstract to a concrete meaning

Typology by Stern (1931)[edit]

- Substitution: Change related to the change of an object, of the knowledge referring to the object, of the attitude toward the object, e.g., artillery «engines of war used to throw missiles» → «mounted guns», atom «inseparable smallest physical-chemical element» → «physical-chemical element consisting of electrons», scholasticism «philosophical system of the Middle Ages» → «servile adherence to the methods and teaching of schools»

- Analogy: Change triggered by the change of an associated word, e.g., fast adj. «fixed and rapid» ← faste adv. «fixedly, rapidly»)

- Shortening: e.g., periodical ← periodical paper

- Nomination: «the intentional naming of a referent, new or old, with a name that has not previously been used for it» (Stern 1931: 282), e.g., lion «brave man» ← «lion»

- Regular transfer: a subconscious Nomination

- Permutation: non-intentional shift of one referent to another due to a reinterpretation of a situation, e.g., bead «prayer» → «pearl in a rosary»)

- Adequation: Change in the attitude of a concept; distinction from substitution is unclear.

This classification does not neatly distinguish between processes and forces/causes of semantic change.

Typology by Bloomfield (1933)[edit]

The most widely accepted scheme in the English-speaking academic world[according to whom?] is from Bloomfield (1933):

- Narrowing: Change from superordinate level to subordinate level. For example, skyline formerly referred to any horizon, but now in the US it has narrowed to a horizon decorated by skyscrapers.[7]

- Widening: There are many examples of specific brand names being used for the general product, such as with Kleenex.[7] Such uses are known as generonyms: see genericization.

- Metaphor: Change based on similarity of thing. For example, broadcast originally meant «to cast seeds out»; with the advent of radio and television, the word was extended to indicate the transmission of audio and video signals. Outside of agricultural circles, very few use broadcast in the earlier sense.[7]

- Metonymy: Change based on nearness in space or time, e.g., jaw «cheek» → «mandible».

- Synecdoche: Change based on whole-part relation. The convention of using capital cities to represent countries or their governments is an example of this.

- Hyperbole: Change from weaker to stronger meaning, e.g., kill «torment» → «slaughter»

- Meiosis: Change from stronger to weaker meaning, e.g., astound «strike with thunder» → «surprise strongly».

- Degeneration: e.g., knave «boy» → «servant» → «deceitful or despicable man»; awful «awe-inspiring» → «very bad.»

- Elevation: e.g., knight «boy» → «nobleman»; terrific «terrifying» → «astonishing» → «very good».

Typology by Ullmann (1957, 1962)[edit]

Ullmann distinguishes between nature and consequences of semantic change:

- Nature of semantic change

- Metaphor: change based on a similarity of senses

- Metonymy: change based on a contiguity of senses

- Folk-etymology: change based on a similarity of names

- Ellipsis: change based on a contiguity of names

- Consequences of semantic change

- Widening of meaning: rise of quantity

- Narrowing of meaning: loss of quantity

- Amelioration of meaning: rise of quality

- Pejoration of meaning: loss of quality

Typology by Blank (1999)[edit]

However, the categorization of Blank (1999) has gained increasing acceptance:[8]

- Metaphor: Change based on similarity between concepts, e.g., mouse «rodent» → «computer device».

- Metonymy: Change based on contiguity between concepts, e.g., horn «animal horn» → «musical instrument».

- Synecdoche: A type of metonymy involving a part to whole relationship, e.g. «hands» from «all hands on deck» → «bodies»

- Specialization of meaning: Downward shift in a taxonomy, e.g., corn «grain» → «wheat» (UK), → «maize» (US).

- Generalization of meaning: Upward shift in a taxonomy, e.g., hoover «Hoover vacuum cleaner» → «any type of vacuum cleaner».

- Cohyponymic transfer: Horizontal shift in a taxonomy, e.g., the confusion of mouse and rat in some dialects.

- Antiphrasis: Change based on a contrastive aspect of the concepts, e.g., perfect lady in the sense of «prostitute».

- Auto-antonymy: Change of a word’s sense and concept to the complementary opposite, e.g., bad in the slang sense of «good».

- Auto-converse: Lexical expression of a relationship by the two extremes of the respective relationship, e.g., take in the dialectal use as «give».

- Ellipsis: Semantic change based on the contiguity of names, e.g., car «cart» → «automobile», due to the invention of the (motor) car.

- Folk-etymology: Semantic change based on the similarity of names, e.g., French contredanse, orig. English country dance.

Blank considered it problematic to include amelioration and pejoration of meaning (as in Ullman) as well as strengthening and weakening of meaning (as in Bloomfield). According to Blank, these are not objectively classifiable phenomena; moreover, Blank has argued that all of the examples listed under these headings can be grouped under other phenomena, rendering the categories redundant.

Forces triggering change[edit]

Blank[9] has tried to create a complete list of motivations for semantic change. They can be summarized as:

- Linguistic forces

- Psychological forces

- Sociocultural forces

- Cultural/encyclopedic forces

This list has been revised and slightly enlarged by Grzega (2004):[10]

- Fuzziness (i.e., difficulties in classifying the referent or attributing the right word to the referent, thus mixing up designations)

- Dominance of the prototype (i.e., fuzzy difference between superordinate and subordinate term due to the monopoly of the prototypical member of a category in the real world)

- Social reasons (i.e., contact situation with «undemarcation» effects)

- Institutional and non-institutional linguistic pre- and proscriptivism (i.e., legal and peer-group linguistic pre- and proscriptivism, aiming at «demarcation»)

- Flattery

- Insult

- Disguising language (i.e., «misnomers»)

- Taboo (i.e., taboo concepts)

- Aesthetic-formal reasons (i.e., avoidance of words that are phonetically similar or identical to negatively associated words)

- Communicative-formal reasons (i.e., abolition of the ambiguity of forms in context, keyword: «homonymic conflict and polysemic conflict»)

- Wordplay/punning

- Excessive length of words

- Morphological misinterpretation (keyword: «folk-etymology», creation of transparency by changes within a word)

- Logical-formal reasons (keyword: «lexical regularization», creation of consociation)

- Desire for plasticity (creation of a salient motivation of a name)

- Anthropological salience of a concept (i.e., anthropologically given emotionality of a concept, «natural salience»)

- Culture-induced salience of a concept («cultural importance»)

- Changes in the referents (i.e., changes in the world)

- Worldview change (i.e., changes in the categorization of the world)

- Prestige/fashion (based on the prestige of another language or variety, of certain word-formation patterns, or of certain semasiological centers of expansion)

The case of reappropriation[edit]

A specific case of semantic change is reappropriation, a cultural process by which a group reclaims words or artifacts that were previously used in a way disparaging of that group, for example like with the word queer. Other related processes include pejoration and amelioration.[11]

Practical studies[edit]

Apart from many individual studies, etymological dictionaries are prominent reference books for finding out about semantic changes. A recent survey lists practical tools and online systems for investigating semantic change of words over time.[12] WordEvolutionStudy is an academic platform that takes arbitrary words as input to generate summary views of their evolution based on Google Books ngram dataset and the Corpus of Historical American English.[13]

See also[edit]

- Calque

- Dead metaphor

- Euphemism treadmill

- False friend

- Genericized trademark

- Language change

- Lexicology and lexical semantics

- List of calques

- Newspeak

- Phono-semantic matching

- Q-based narrowing

- Semantic field

- Skunked term

- Retronym

Notes[edit]

- ^ «13 Words That Changed From Negative to Positive Meanings (or Vice Versa)». Mental Floss. July 9, 2015. Retrieved May 7, 2022.

- ^ Lalor, Therese (2007). «‘That’s So Gay’: A Contemporary Use of Gay in Australian English». Australian Journal of Linguistics. 27 (200): 147–173. doi:10.1080/07268600701522764. hdl:1885/30763. S2CID 53710541.

- ^ Blank (1997:7–46)

- ^ in Ullmann (1957), and Ullmann (1962)

- ^ An example of this comes from Old English: meat (or rather mete) referred to all forms of solid food while flesh (flæsc) referred to animal tissue and food (foda) referred to animal fodder; meat was eventually restricted to flesh of animals, then flesh restricted to the tissue of humans and food was generalized to refer to all forms of solid food Jeffers & Lehiste (1979:130)

- ^ in Geeraerts (1983) and Geeraerts (1997)

- ^ a b c Jeffers & Lehiste (1979:129)

- ^ Grzega (2004) paraphrases these categories (except ellipses and folk etymology) as «similar-to» relation, «neighbor-of» relation, «part-of» relation, «kind-of» relation (for both specialization and generalization), «sibling-of» relation, and «contrast-to» relation (for antiphrasis, auto-antonymy, and auto-converse), respectively

- ^ in Blank (1997) and Blank (1999)

- ^ Compare Grzega (2004) and Grzega & Schöner (2007)

- ^ Anne Curzan (May 8, 2014). Fixing English: Prescriptivism and Language History. Cambridge University Press. pp. 146–148. ISBN 978-1-107-02075-7.

- ^ Adam Jatowt, Nina Tahmasebi, Lars Borin (2021). Computational Approaches to Lexical Semantic Change: Visualization Systems and Novel Applications. Language Science Press. pp. 311–340.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Adam Jatowt (2018). «Every Word has its History: Interactive Exploration and Visualization of Word Sense Evolution» (PDF). ACM Press. pp. 1988–1902.

References[edit]

- Blank, Andreas (1997), Prinzipien des lexikalischen Bedeutungswandels am Beispiel der romanischen Sprachen (Beihefte zur Zeitschrift für romanische Philologie 285), Tübingen: Niemeyer

- Blank, Andreas (1999), «Why do new meanings occur? A cognitive typology of the motivations for lexical Semantic change», in Blank, Andreas; Koch, Peter (eds.), Historical Semantics and Cognition, Berlin/New York: Mouton de Gruyter, pp. 61–90

- Blank, Andreas; Koch, Peter (1999), «Introduction: Historical Semantics and Cognition», in Blank, Andreas; Koch, Peter (eds.), Historical Semantics and Cognition, Berlin/New York: Mouton de Gruyter, pp. 1–16

- Bloomfield, Leonard (1933), Language, New York: Allen & Unwin

- Bréal, Michel (1899), Essai de sémantique (2nd ed.), Paris: Hachette

- Coseriu, Eugenio (1964), «Pour une sémantique diachronique structurale», Travaux de Linguistique et de Littérature, 2: 139–186

- Darmesteter, Arsène (1887), La vie des mots, Paris: Delagrave

- Fritz, Gerd (1974), Bedeutungswandel im Deutschen, Tübingen: Niemeyer

- Geeraerts, Dirk (1983), «Reclassifying Semantic change», Quaderni di Semantica, 4: 217–240

- Geeraerts, Dirk (1997), Diachronic prototype Semantics: a contribution to historical lexicology, Oxford: Clarendon

- Grzega, Joachim (2004), Bezeichnungswandel: Wie, Warum, Wozu? Ein Beitrag zur englischen und allgemeinen Onomasiologie, Heidelberg: Winter

- Grzega, Joachim; Schöner, Marion (2007), English and general historical lexicology: materials for onomasiology seminars (PDF), Eichstätt: Universität

- Jeffers, Robert J.; Lehiste, Ilse (1979), Principles and methods for historical linguistics, MIT press, ISBN 0-262-60011-0

- Paul, Hermann (1880), Prinzipien der Sprachgeschichte, Tübingen: Niemeyer

- Reisig, Karl (1839), «Semasiologie oder Bedeutungslehre», in Haase, Friedrich (ed.), Professor Karl Reisigs Vorlesungen über lateinische Sprachwissenschaft, Leipzig: Lehnhold

- Stern, Gustaf (1931), Meaning and change of meaning with special reference to the English language, Göteborg: Elander

- Traugott, Elizabeth Closs (1990), «From less to more situated in language: the unidirectionality of Semantic change», in Adamson, Silvia; Law, Vivian A.; Vincent, Nigel; Wright, Susan (eds.), Papers from the Fifth International Conference on English Historical Linguistics, Amsterdam: Benjamins, pp. 496–517

- Trier, Jost (1931), Der deutsche Wortschatz im Sinnbezirk des Verstandes (dissertation)

- Ullmann, Stephen (1957), Principles of Semantics (2nd ed.), Oxford: Blackwell

- Ullmann, Stephen (1962), Semantics: An introduction to the science of meaning, Oxford: Blackwell

- Vanhove, Martine (2008), From Polysemy to Semantic change: Towards a Typology of Lexical Semantic Associations, Studies in Language Companion Series 106, Amsterdam, New York: Benjamins.

- Warren, Beatrice (1992), Sense Developments: A contrastive study of the development of slang senses and novel standard senses in English, [Acta Universitatis Stockholmiensis 80], Stockholm: Almqvist & Wiksell

- Zuckermann, Ghil’ad (2003), Language Contact and Lexical Enrichment in Israeli Hebrew. Palgrave Macmillan, ISBN 1-4039-1723-X.

Further reading[edit]

- AlBader, Yousuf B. (2015) «Semantic Innovation and Change in Kuwaiti Arabic: A Study of the Polysemy of Verbs»

- AlBader, Yousuf B. (2016) «From dašš l-ġōṣ to dašš twitar: Semantic Change in Kuwaiti Arabic»

- AlBader, Yousuf B. (2017) «Polysemy and Semantic Change in the Arabic Language and Dialects»

- Grzega, Joachim (2000), «Historical Semantics in the Light of Cognitive Linguistics: Aspects of a new reference book reviewed», Arbeiten aus Anglistik und Amerikanistik 25: 233–244.

- Koch, Peter (2002), «Lexical typology from a cognitive and linguistic point of view», in: Cruse, D. Alan et al. (eds.), Lexicology: An international handbook on the nature and structure of words and vocabularies/lexikologie: Ein internationales Handbuch zur Natur und Struktur von Wörtern und Wortschätzen, [Handbücher zur Sprach- und Kommunikationswissenschaft 21], Berlin/New York: Walter de Gruyter, vol. 1, 1142–1178.

- Wundt, Wilhelm (1912), Völkerpsychologie: Eine Untersuchung der Entwicklungsgesetze von Sprache, Mythus und Sitte, vol. 2,2: Die Sprache, Leipzig: Engelmann.

External links[edit]

- Onomasiology Online (internet platform by Joachim Grzega, Alfred Bammesberger and Marion Schöner, including a list of etymological dictionaries)

- Etymonline, Online Etymology Dictionary of the English language.

- Exploring Word Evolution An online analysis tool for studying evolution of any input words based on Google Books n-gram dataset and the Corpus of Historical American English (COHA).

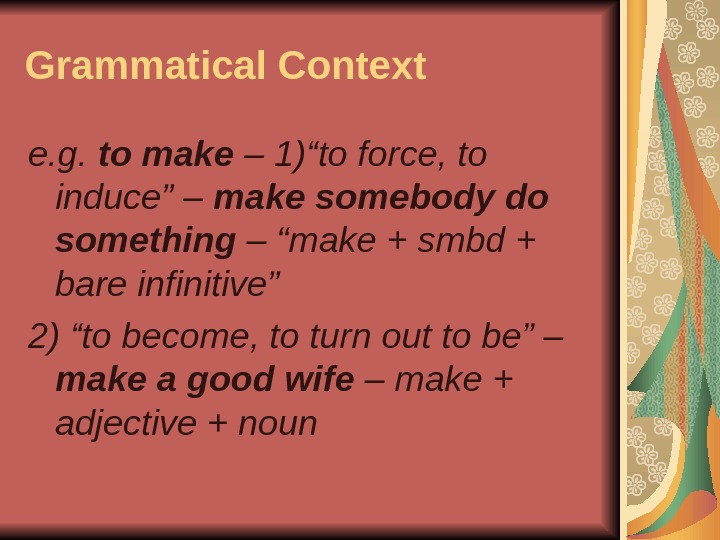

Слайд 1Lecture 3

Semantic Structure of the Word and Its Changes

Слайд 2Plan:

Semantics / semasiology. Different approaches to word-meaning.

Types of word-meaning.

Polysemy. Semantic

structure of words. Meaning and context.

Change of word-meaning: the causes, nature and results.

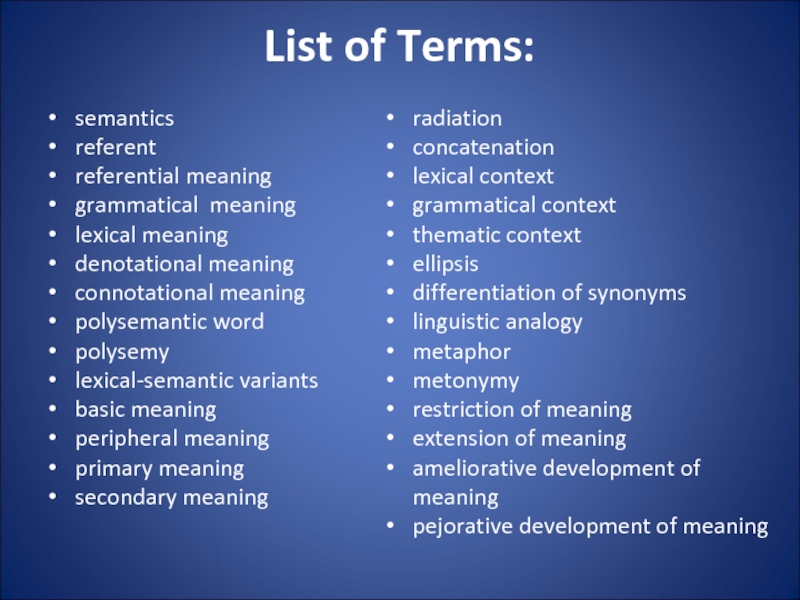

Слайд 3List of Terms:

semantics

referent

referential meaning

grammatical meaning

lexical meaning

denotational meaning

connotational meaning

polysemantic word

polysemy

lexical-semantic variants

basic meaning

peripheral

meaning

primary meaning

secondary meaning

radiation

concatenation

lexical context

grammatical context

thematic context

ellipsis

differentiation of synonyms

linguistic analogy

metaphor

metonymy

restriction of meaning

extension of meaning

ameliorative development of meaning

pejorative development of meaning

Слайд 4

It is meaning that makes language useful.

George A. Miller,

The science of word, 1991

Слайд 5

1. Semantics / semasiology. Different approaches to word-meaning

Слайд 6

The function of the word as a unit of

communication is possible by its possessing a meaning.

Among the word’s various characteristics meaning is the most important.

Слайд 7

«The Meaning of Meaning» (1923) by C.K. Ogden and I.A. Richards

– about 20 definitions of meaning

Слайд 8Meaning of a linguistic unit, or linguistic meaning, is studied by

semantics

(from Greek – semanticos ‘significant’)

Слайд 9

This linguistic study was pointed out in 1897 by

M. Breal

Слайд 10

Semasiology is a synonym for ‘semantics’

(from

Gk. semasia ‘meaning’ + logos ‘learning’)

Слайд 11Different Approaches to Word Meaning:

ideational (or conceptual)

referential

functional

Слайд 12

The ideational theory can be considered the earliest theory

of meaning.

It states that meaning originates in the mind in the form of ideas, and words are just symbols of them.

Слайд 13A difficulty:

not clear why communication and understanding are possible if

linguistic expressions stand for individual personal ideas.

Слайд 14Meaning:

a concept with specific structure.

Слайд 15

Do people speaking different languages have different conceptual systems?

If people

speaking different languages have the same conceptual systems why are identical concepts expressed by correlative words having different lexical meanings?

Слайд 16

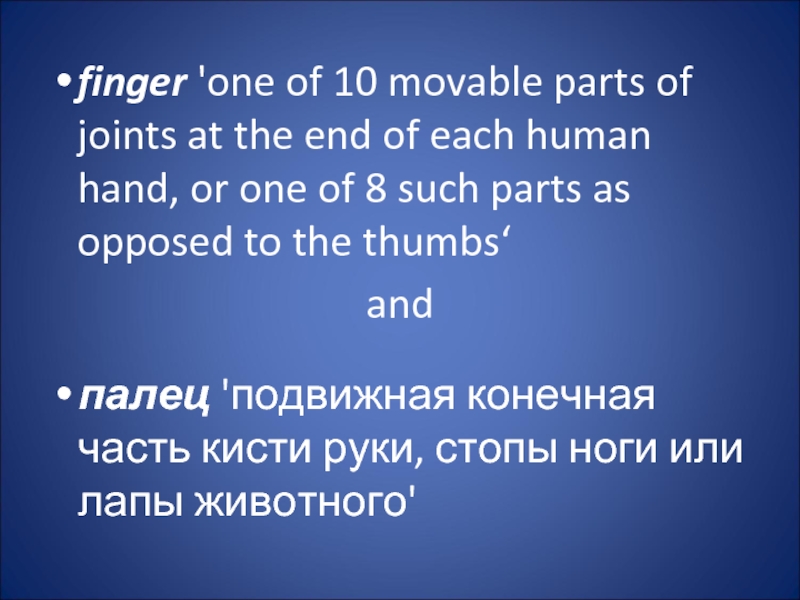

finger ‘one of 10 movable parts of joints at the end

of each human hand, or one of 8 such parts as opposed to the thumbs‘

and

палец ‘подвижная конечная часть кисти руки, стопы ноги или лапы животного’

Слайд 17

Referential theory is based on interdependence of things,

their concepts and names.

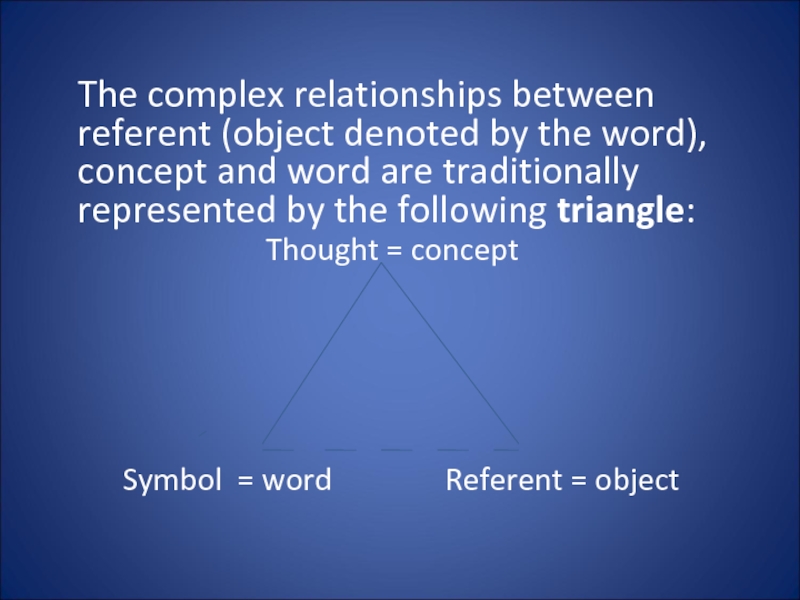

Слайд 18

The complex relationships between referent (object denoted by the

word), concept and word are traditionally represented by the following triangle:

Thought = concept

Symbol = word Referent = object

Слайд 19

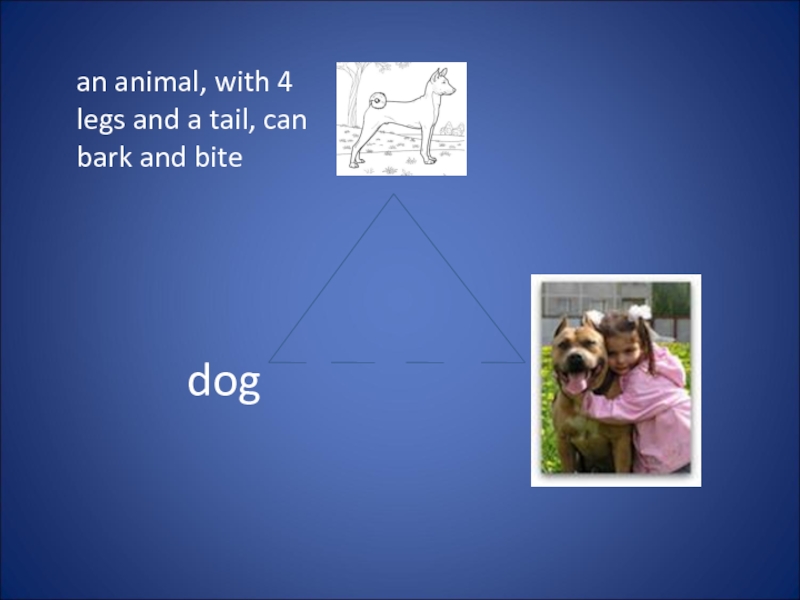

an animal, with 4

legs and a tail, can bark and

bite

dog

Слайд 20Meaning concept

different words having different meanings may be

used to express the same concept

Слайд 21Concept of dying

die

pass away

kick the bucket

join the majority,

etc

Слайд 22Meaning symbol

In different languages:

a word with the same

meaning have different sound forms (dog, собака)

words with the same sound forms have different meaning (лук, look)

Слайд 23Meaning referent

to denote one and the same object

we can give it different names

Слайд 24A horse

in various contexts:

horse,

animal,

creature,

it, etc.

Слайд 25Word meaning:

the interrelation of all three components of

the semantic triangle: symbol, concept and referent, though meaning is not equivalent to any of them.

Слайд 26

Functionalists study word meaning by analysis of the way

the word is used in certain contexts.

Слайд 27

The meaning of a word is its use

in language.

Слайд 28cloud and cloudy

have different meanings because in speech they function

differently and occupy different positions in relation to other words.

Слайд 29Meaning:

a component of the word through which a concept

is communicated

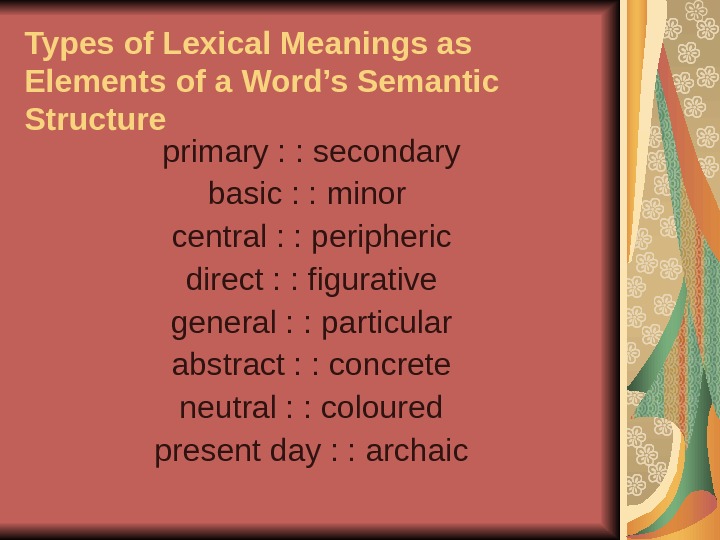

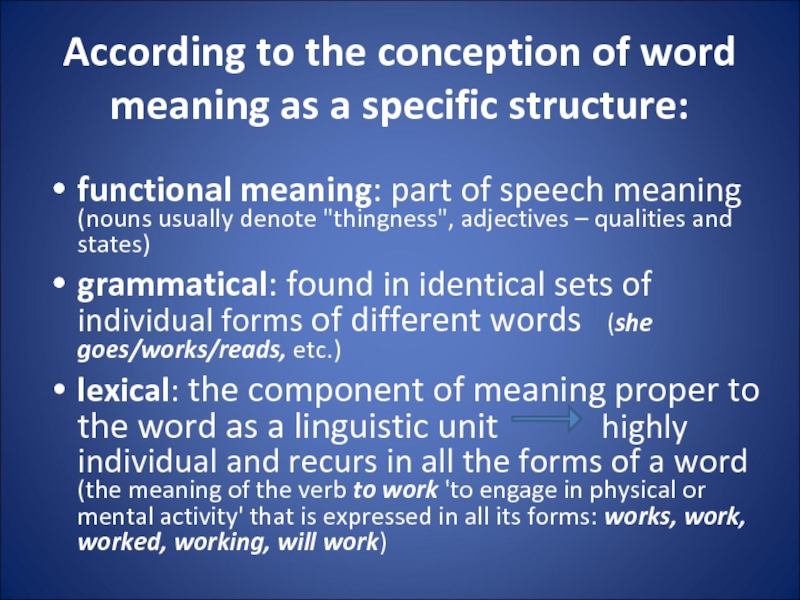

Слайд 31According to the conception of word meaning as a specific structure:

functional

meaning: part of speech meaning (nouns usually denote «thingness», adjectives – qualities and states)

grammatical: found in identical sets of individual forms of different words (she goes/works/reads, etc.)

lexical: the component of meaning proper to the word as a linguistic unit highly individual and recurs in all the forms of a word (the meaning of the verb to work ‘to engage in physical or mental activity’ that is expressed in all its forms: works, work, worked, working, will work)

Слайд 32Lexical Meaning:

denotational

connotational

Слайд 33

Denotational lexical meaning provides correct reference of a word to an

individual object or a concept.

It makes communication possible and is explicitly revealed in the dictionary definition (chair ‘a seat for one person typically having four legs and a back’).

Слайд 35

Connotational lexical meaning is an emotional colouring of the

word. Unlike denotational meaning, connotations are optional.

Слайд 36Connotations:

Emotive charge may be inherent in word meaning (like in attractive,

repulsive) or may be created by prefixes and suffixes (like in piggy, useful, useless).

It’s always objective because it doesn’t depend on a person’s perception.

Слайд 37

2. Stylistic reference refers the word to a certain style:

neutral words

colloquial

bookish,

or literary words

Eg. father – dad – parent .

Слайд 38

3. Evaluative connotations express approval or disapproval (charming, disgusting).

4. Intensifying connotations

are expressive and emphatic (magnificent, gorgeous)

Слайд 39

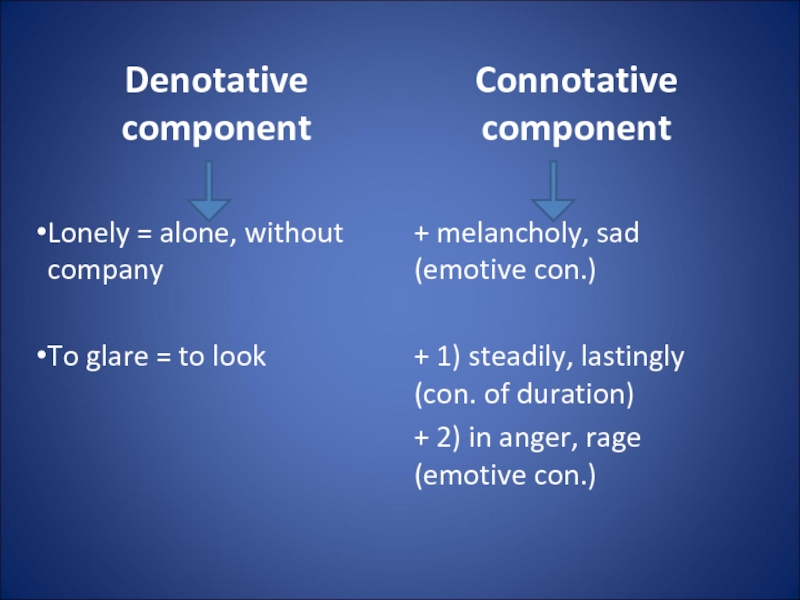

Denotative component

Lonely = alone, without company

To glare = to look

Connotative component

+ melancholy, sad (emotive con.)

+ 1) steadily, lastingly (con. of duration)

+ 2) in anger, rage (emotive con.)

Слайд 40

3. Polysemy. Semantic structure of words. Meaning and context

Слайд 41

A polysemantic word is a word having more than one meaning.

Polysemy

is the ability of words to have more than one meaning.

Слайд 42

Most English words are polysemantic.

A well-developed polysemy is a great advantage in a language.

Слайд 43Monosemantic Words:

terms (synonym, bronchitis, molecule),

pronouns (this, my, both),

numerals, etc.

Слайд 44The main causes of polysemy:

a large number of:

1) monosyllabic words;

2) words of long duration (that existed for centuries).

Слайд 45The sources of polysemy:

1) the process of meaning change (meaning specialization:

is used in more concrete spheres);

2) figurative language (metaphor and metonymy);

3) homonymy;

4) borrowing of meanings from other languages.

Слайд 46blanket

a woolen covering used on beds,

a covering for keeping a house

warm,

a covering of any kind (a blanket of snow),

covering in most cases (used attributively), e.g. we can say: a blanket insurance policy.

Слайд 47

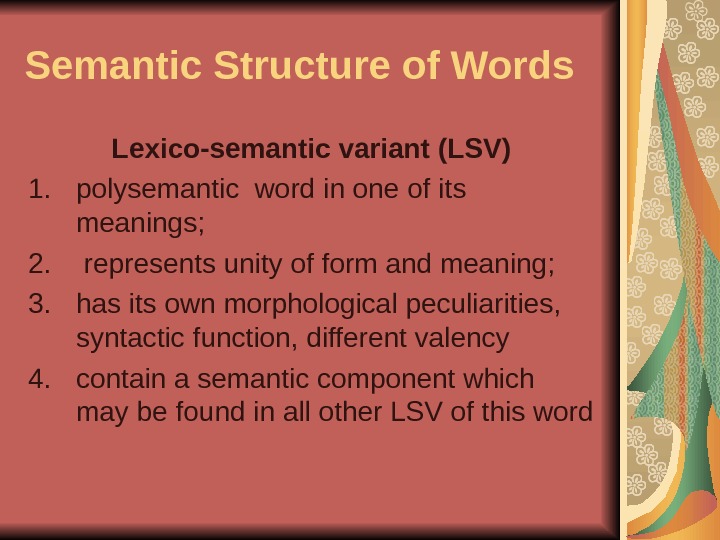

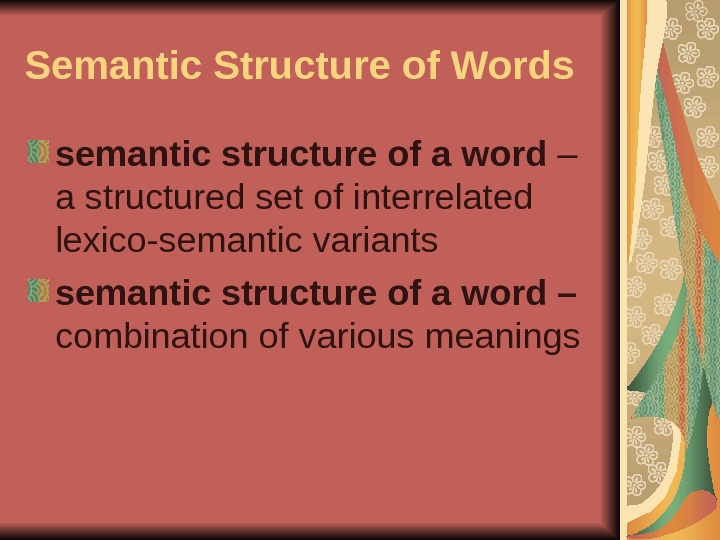

Meanings of a polysemantic word are organized in a

semantic structure

Слайд 48Lexical-semantic variant

one of the meanings of a polysemantic word used

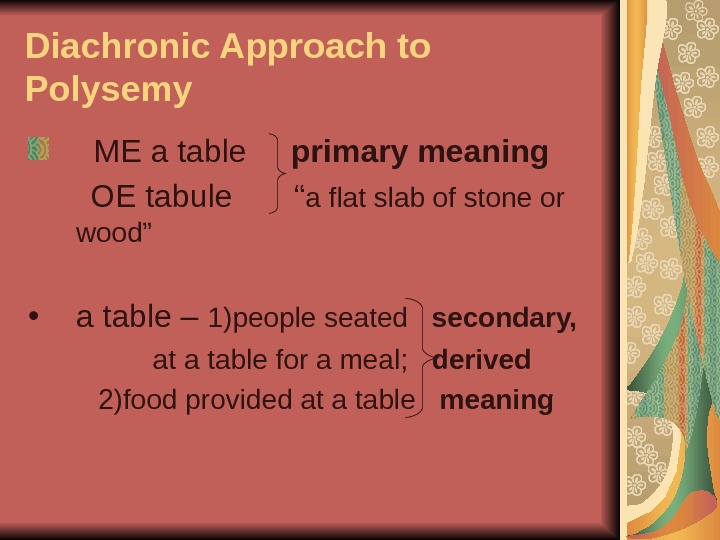

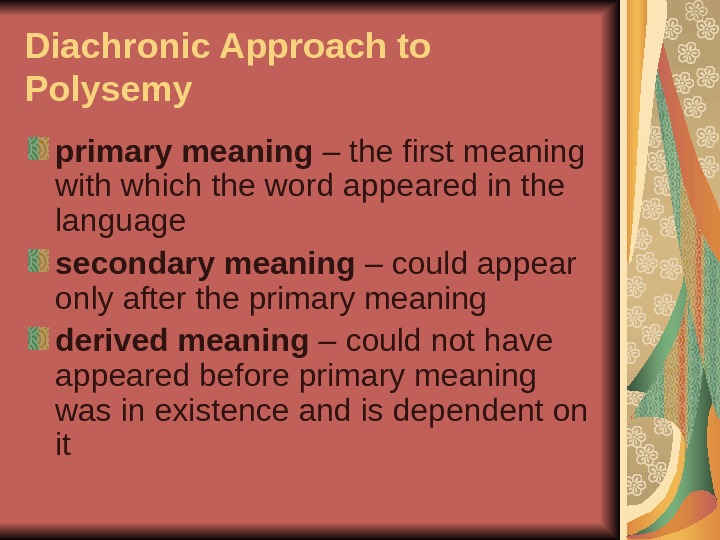

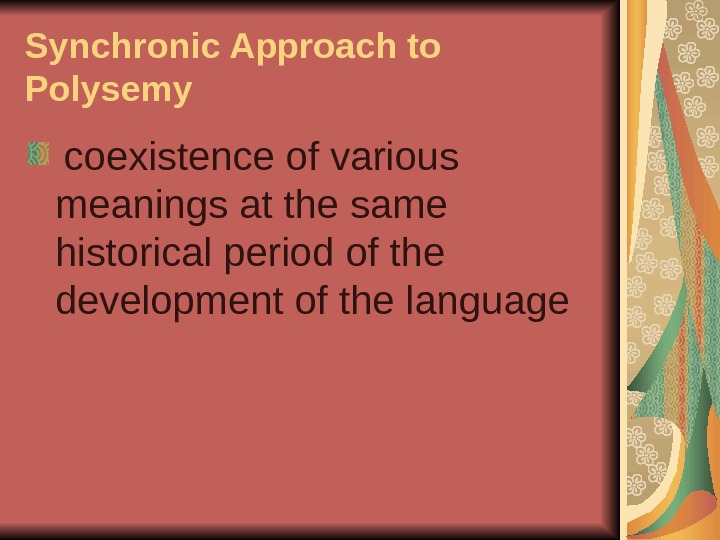

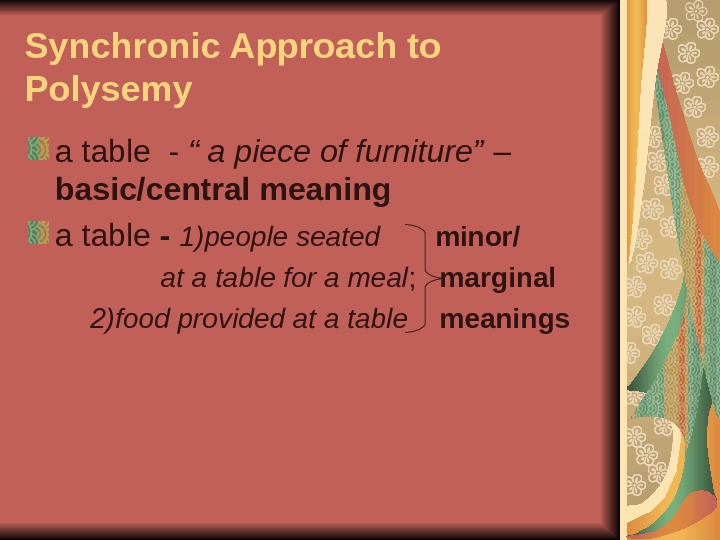

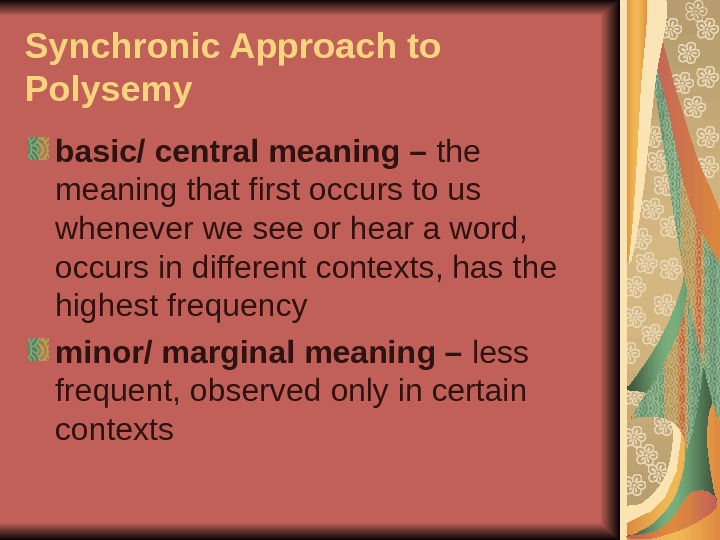

Слайд 49A Word’s Semantic Structure Is Studied:

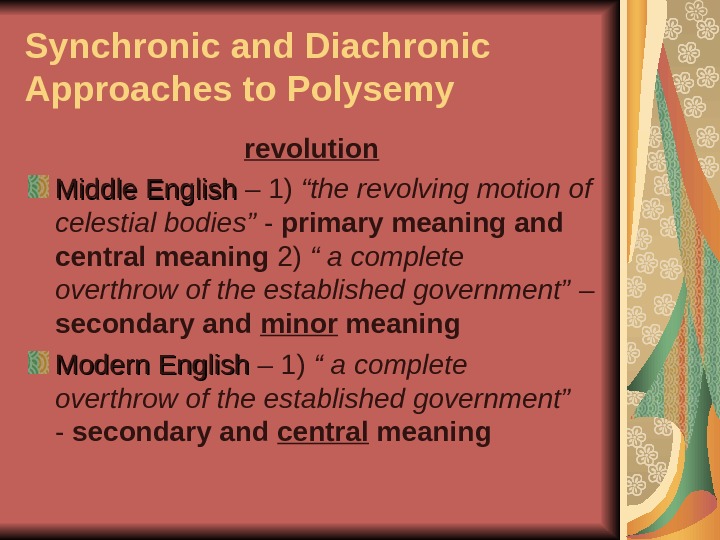

Diachronically (in the process of its

historical development): the historical development and change of meaning becomes central. Focus: the process of acquiring new meanings.

Synchronically (at a certain period of time): a co-existence of different meanings in the semantic structure of the word at a certain period of language development. Focus: value of each individual meaning and frequency of its occurrence.

Слайд 50

The meaning first registered in the language is called primary.

Other

meanings are secondary, or derived, and are placed after the primary one.

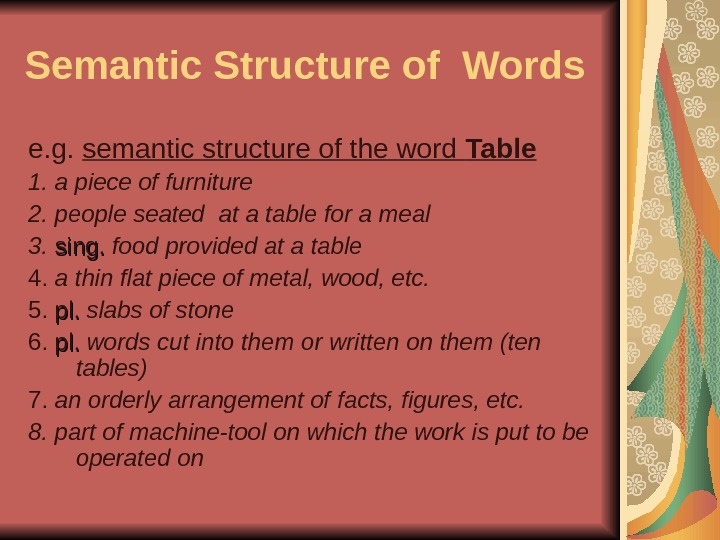

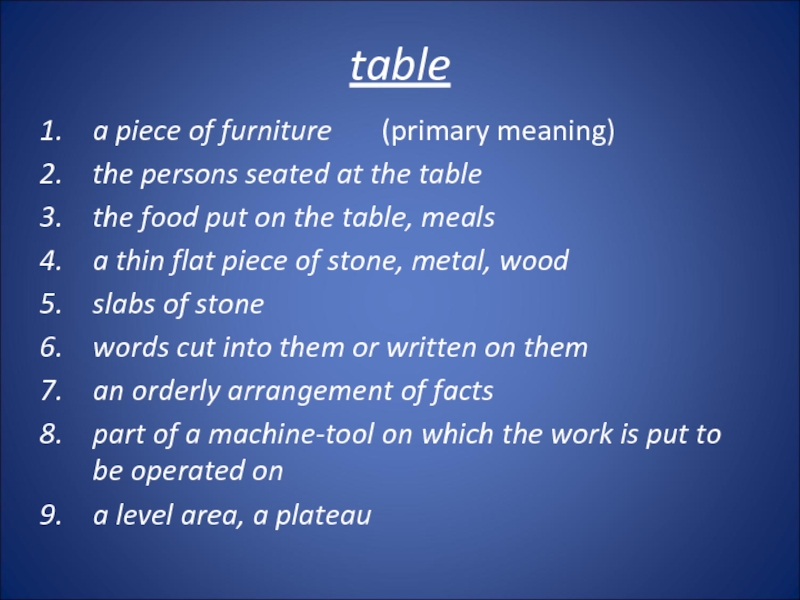

Слайд 51table

a piece of furniture (primary meaning)

the persons

seated at the table

the food put on the table, meals

a thin flat piece of stone, metal, wood

slabs of stone

words cut into them or written on them

an orderly arrangement of facts

part of a machine-tool on which the work is put to be operated on

a level area, a plateau

Слайд 52

The meaning that first occurs to our mind, or is understood

without a special context is called the basic or main meaning.

Other meanings are called peripheral or minor.

Слайд 53Fire

1. flame (main meaning)

2. an instance of destructive burning

e.g. a forest fire

4. the shooting of guns

e.g. to open fire

3. burning material in a stone, fireplace

e.g. a camp fire

5. strong feeling, passion

e.g. speech lacking fire

Слайд 54Processes of the Semantic Development of a Word:

radiation (the primary meaning

stands in the center and the secondary meanings proceed out of it like rays. Each secondary meaning can be traced to the primary meaning)

concatenation (secondary meanings of a word develop like a chain. It is difficult to trace some meanings to the primary one)

Слайд 55crust

hard outer part of bread

hard part of anything (a

pie, a cake)

harder layer over soft snow

a sullen gloomy person

Impudence

Слайд 56

Polysemy exists not in speech but in the language.

It’s

easy to identify the main meaning of a separate word. Other meanings are revealed in context.

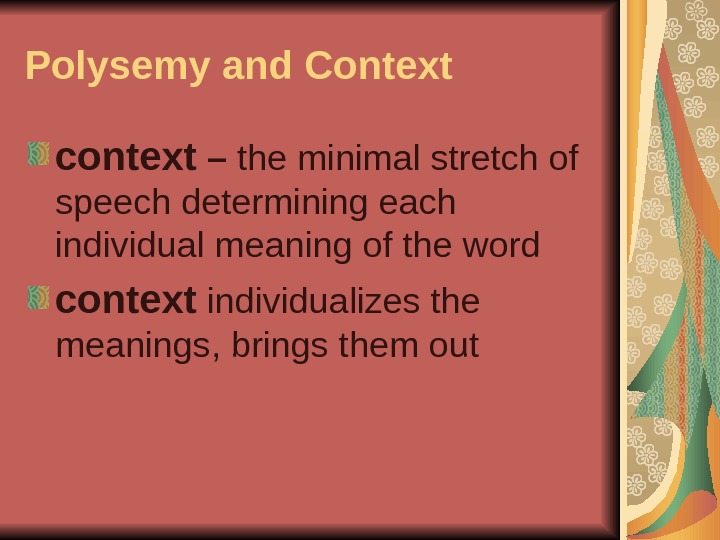

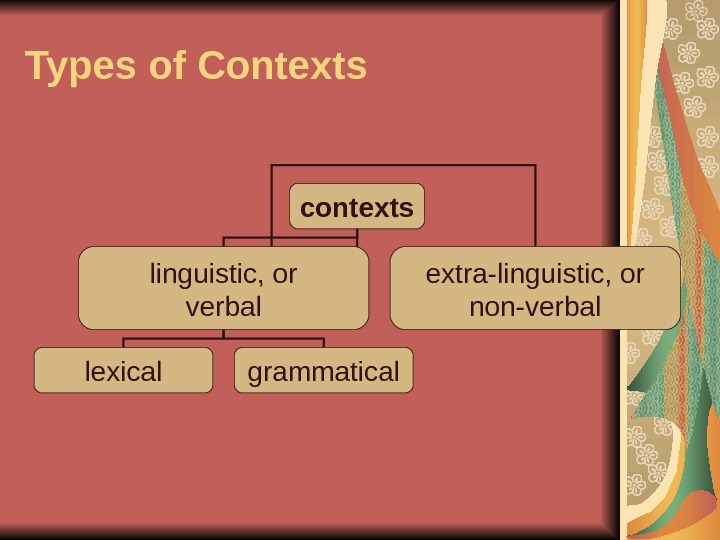

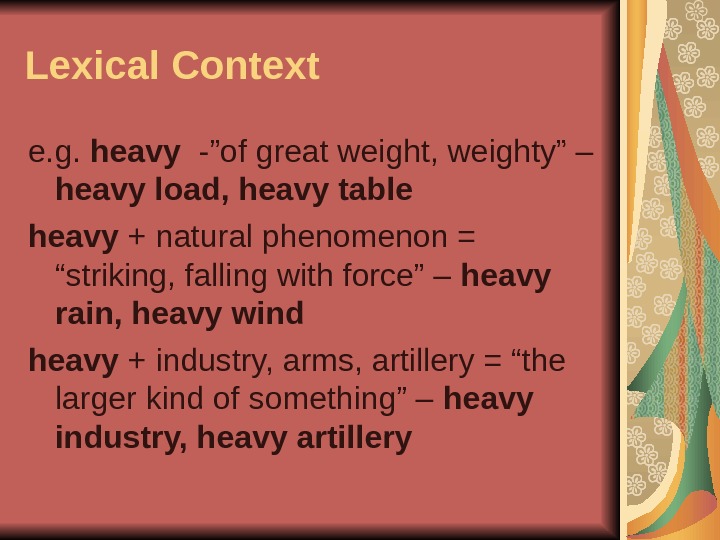

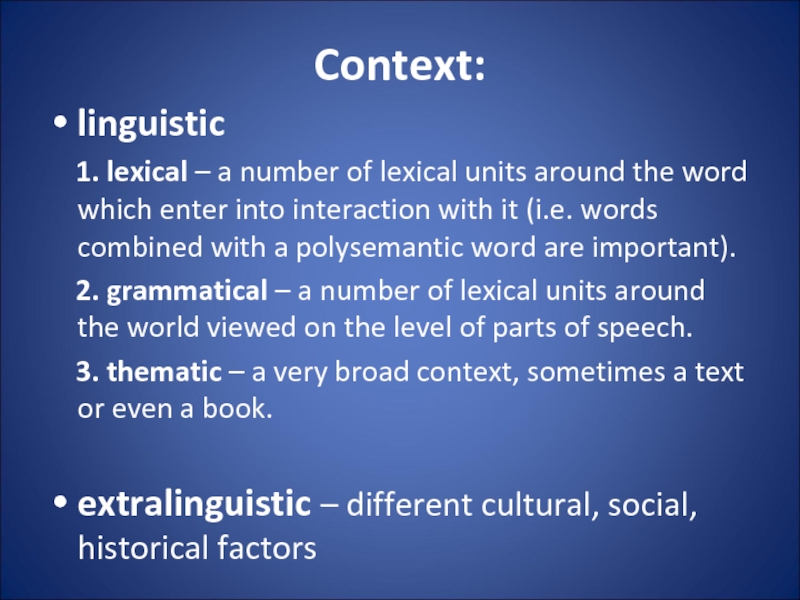

Слайд 57Context:

linguistic

1. lexical – a number of lexical units

around the word which enter into interaction with it (i.e. words combined with a polysemantic word are important).

2. grammatical – a number of lexical units around the world viewed on the level of parts of speech.

3. thematic – a very broad context, sometimes a text or even a book.

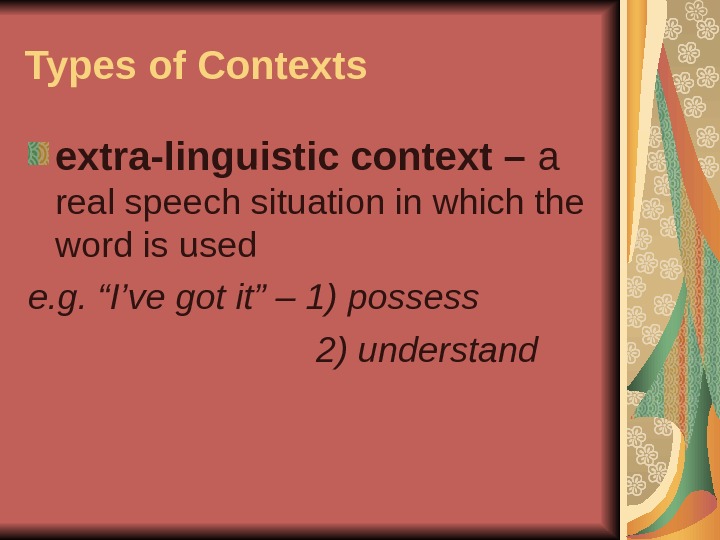

extralinguistic – different cultural, social, historical factors

Слайд 58

4. Change of word-meaning: the causes, nature and results

Слайд 59

The meaning of a word can change in a course

of time.

Слайд 60Causes of Change of

Word-meaning:

1. Extralinguistic (various changes in the life

of a speech community, in economic and social structure, in ideas, scientific concepts)

e.g. “car” meant ‘a four-wheeled wagon’; now – ‘a motor-car’, ‘a railway carriage’ (in the USA)

“paper” is not connected anymore with “papyrus” – the plant from which it formerly was made.

2. Linguistic (factors acting within the language system)

Слайд 61Linguistic Causes:

1. ellipsis – in a phrase made up of two

words one of these is omitted and its meaning is transferred to its partner.

e.g. “to starve” in O.E. = ‘to die’ + the word “hunger”. In the 16th c. “to starve” = ‘to die of hunger’.

e.g. daily = daily newspaper

Слайд 62Linguistic Causes:

2. differentiation (discrimination) of synonyms – when a new

word is borrowed it may become a perfect synonym for the existing one. They have to be differentiated; otherwise one of them will die.

e.g. “land” in O.E. = both ‘solid part of earth’s surface’ and ‘the territory of the nation’. In the middle E. period the word “country” was borrowed as its synonym; ‘the territory of a nation’ came to be denoted mainly by “country”.

Слайд 63Linguistic Causes:

3. linguistic analogy – if one of the members of

the synonymic set acquires a new meaning, other members of this set change their meaning too.

e.g. “to catch” acquired the meaning ‘to understand’; its synonyms “to grasp” and “to get” acquired this meaning too.

Слайд 64

The nature of semantic changes is based on the

secondary application of the word form to name a different yet related concept.

Conditions to any semantic change: some connection between the old meaning and the new.

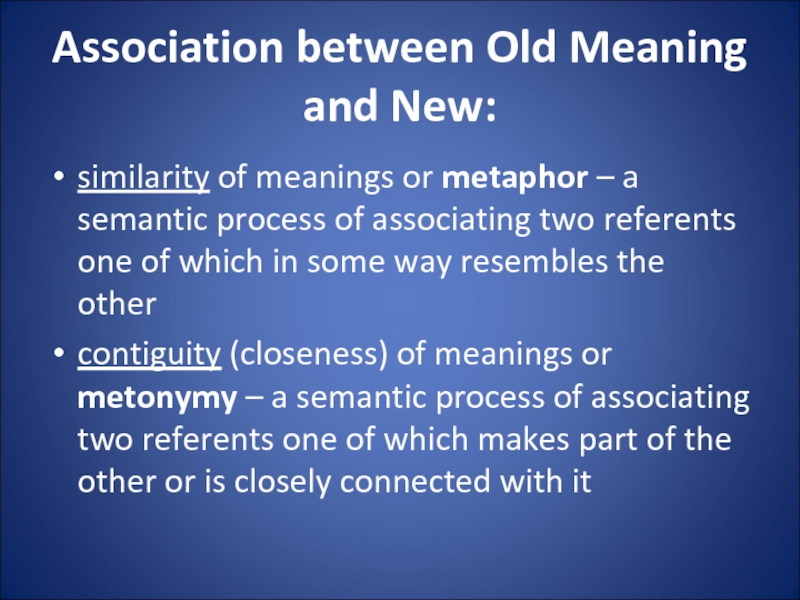

Слайд 65Association between Old Meaning and New:

similarity of meanings or metaphor –

a semantic process of associating two referents one of which in some way resembles the other

contiguity (closeness) of meanings or metonymy – a semantic process of associating two referents one of which makes part of the other or is closely connected with it

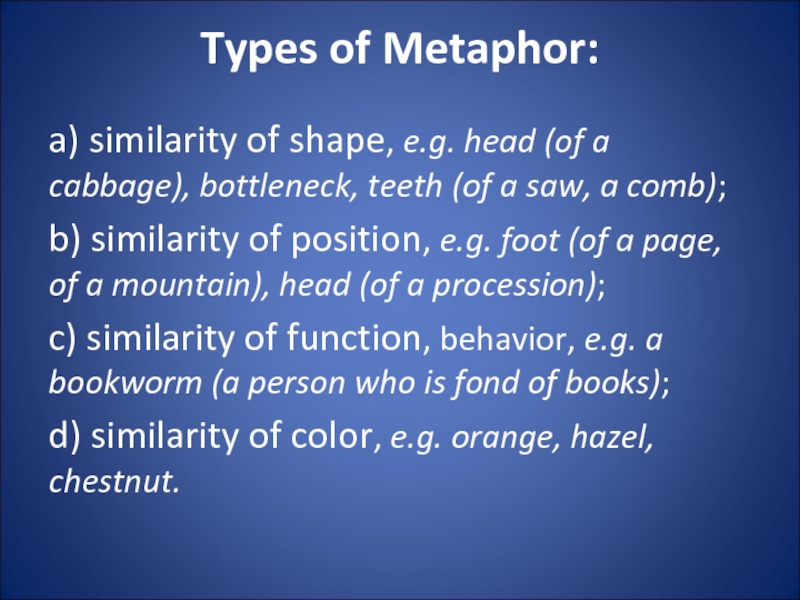

Слайд 66Types of Metaphor:

a) similarity of shape, e.g. head (of a cabbage),

bottleneck, teeth (of a saw, a comb);

b) similarity of position, e.g. foot (of a page, of a mountain), head (of a procession);

c) similarity of function, behavior, e.g. a bookworm (a person who is fond of books);

d) similarity of color, e.g. orange, hazel, chestnut.

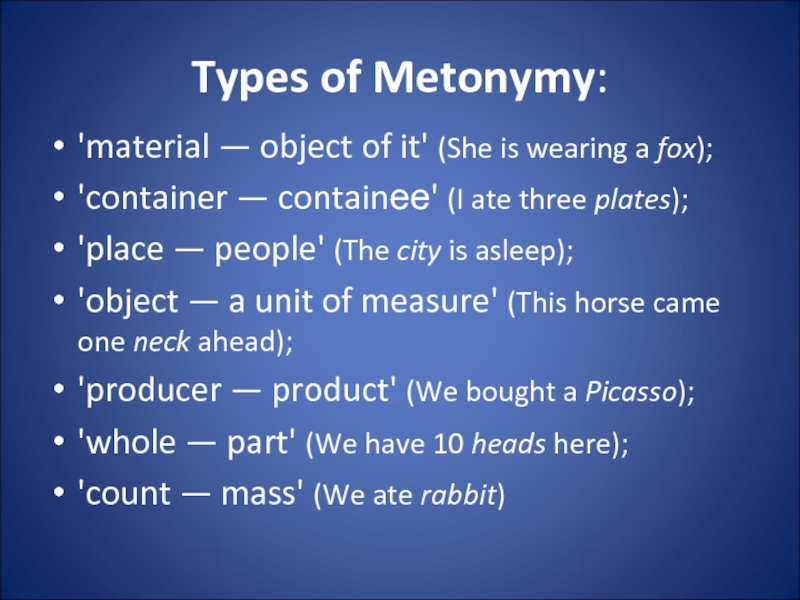

Слайд 67Types of Metonymy:

‘material — object of it’ (She is wearing a

fox);

‘container — containее’ (I ate three plates);

‘place — people’ (The city is asleep);

‘object — a unit of measure’ (This horse came one neck ahead);

‘producer — product’ (We bought a Picasso);

‘whole — part’ (We have 10 heads here);

‘count — mass’ (We ate rabbit)

Слайд 68Results of Semantic Change:

changes in the denotational component

changes in the connotational

meaning

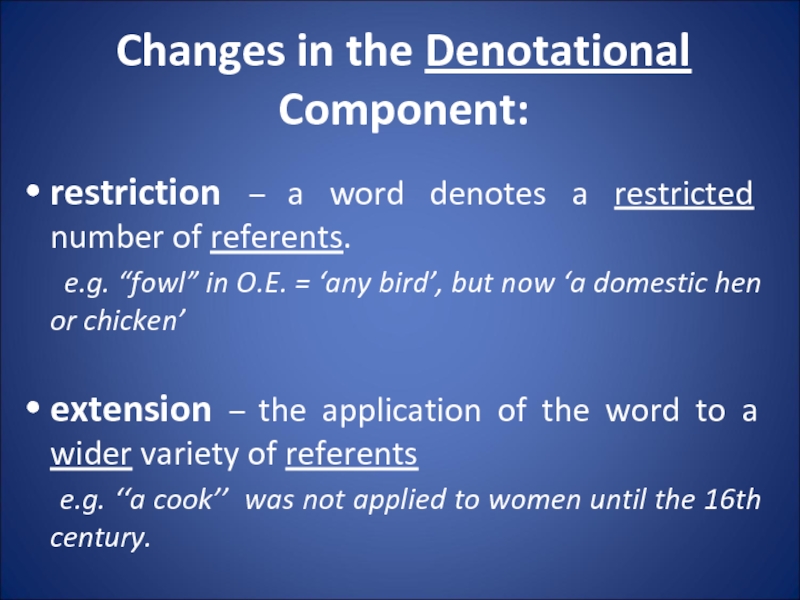

Слайд 69Changes in the Denotational Component:

restriction – a word denotes a restricted

number of referents.

e.g. “fowl” in O.E. = ‘any bird’, but now ‘a domestic hen or chicken’

extension – the application of the word to a wider variety of referents

e.g. ‘‘a cook’’ was not applied to women until the 16th century.

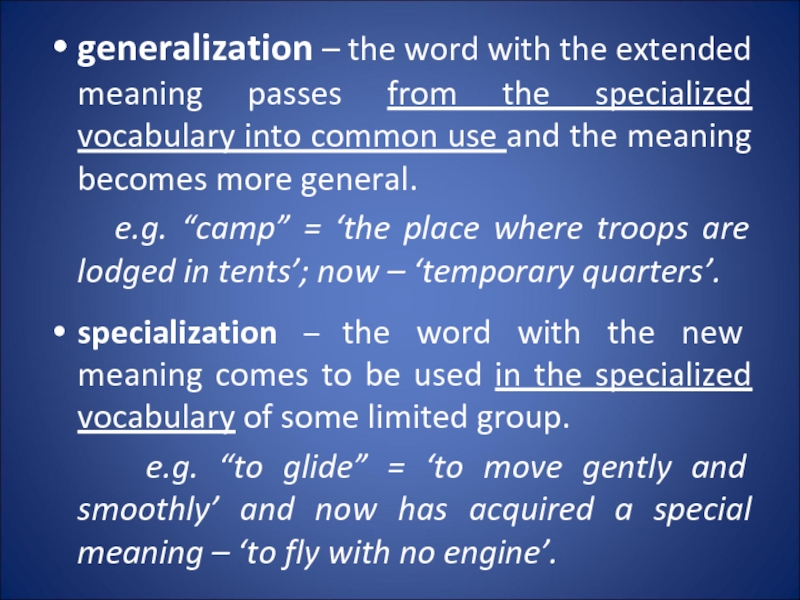

Слайд 70

generalization – the word with the extended meaning passes from the

specialized vocabulary into common use and the meaning becomes more general.

e.g. “camp” = ‘the place where troops are lodged in tents’; now – ‘temporary quarters’.

specialization – the word with the new meaning comes to be used in the specialized vocabulary of some limited group.

e.g. “to glide” = ‘to move gently and smoothly’ and now has acquired a special meaning – ‘to fly with no engine’.

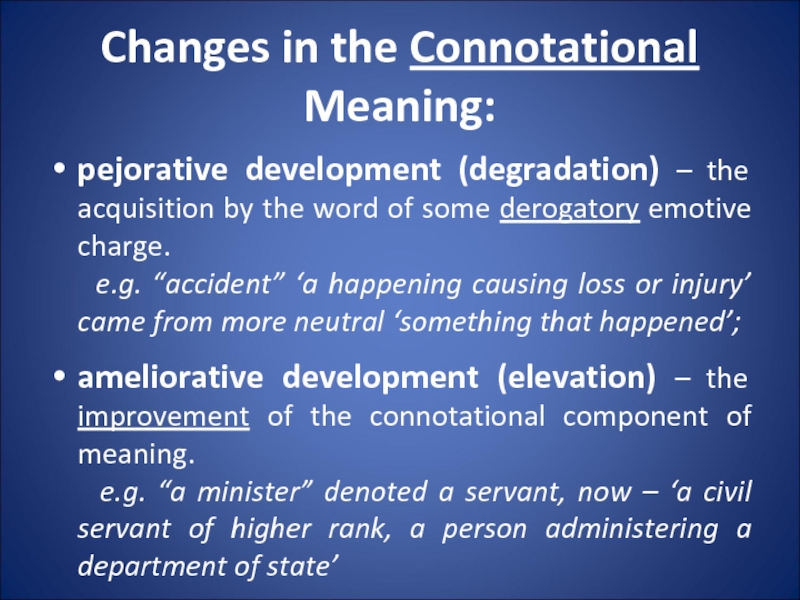

Слайд 71Changes in the Connotational Meaning:

pejorative development (degradation) – the acquisition by

the word of some derogatory emotive charge.

e.g. “accident” ‘a happening causing loss or injury’ came from more neutral ‘something that happened’;

ameliorative development (elevation) – the improvement of the connotational component of meaning.

e.g. “a minister” denoted a servant, now – ‘a civil servant of higher rank, a person administering a department of state’

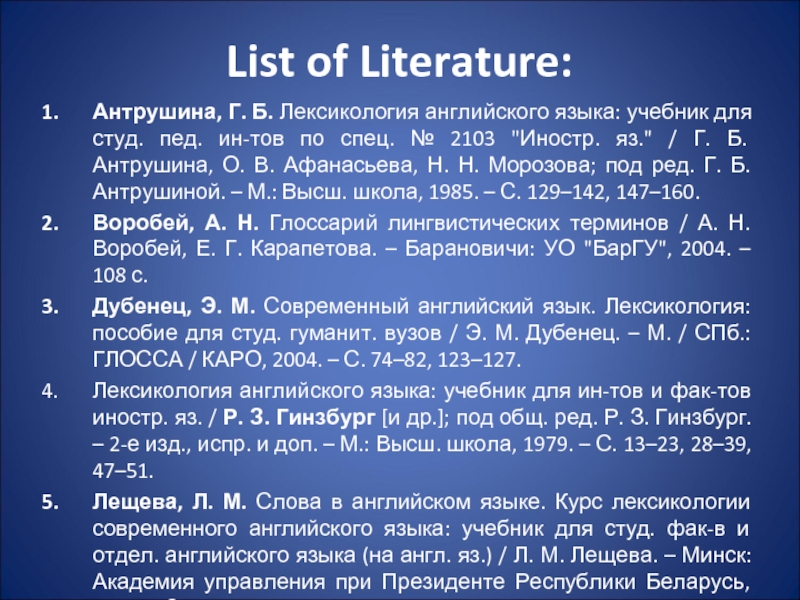

Слайд 72List of Literature:

Антрушина, Г. Б. Лексикология английского языка: учебник для студ.

пед. ин-тов по спец. № 2103 «Иностр. яз.» / Г. Б. Антрушина, О. В. Афанасьева, Н. Н. Морозова; под ред. Г. Б. Антрушиной. – М.: Высш. школа, 1985. – С. 129–142, 147–160.

Воробей, А. Н. Глоссарий лингвистических терминов / А. Н. Воробей, Е. Г. Карапетова. – Барановичи: УО «БарГУ», 2004. – 108 с.

Дубенец, Э. М. Современный английский язык. Лексикология: пособие для студ. гуманит. вузов / Э. М. Дубенец. – М. / СПб.: ГЛОССА / КАРО, 2004. – С. 74–82, 123–127.

Лексикология английского языка: учебник для ин-тов и фак-тов иностр. яз. / Р. З. Гинзбург [и др.]; под общ. ред. Р. З. Гинзбург. – 2-е изд., испр. и доп. – М.: Высш. школа, 1979. – С. 13–23, 28–39, 47–51.

Лещева, Л. М. Слова в английском языке. Курс лексикологии современного английского языка: учебник для студ. фак-в и отдел. английского языка (на англ. яз.) / Л. М. Лещева. – Минск: Академия управления при Президенте Республики Беларусь, 2001. – С. 36–56.