In this blog post, we look at a useful way to help us remember vocabulary – putting words into groups. We find out how to harness our brain’s natural tendency to understand the world through association (this object is green and has leaves – it must be a plant!) to help us create groups of related words that will help us learn and remember them. We can create groups based on different things: themes, verbs/nouns and adjectives, synonyms, prefixes – these are just a few that we explore here.

I know what you’re thinking, another post on learning vocabulary! But this technique is different from the visualisation technique or the recognising cognates technique we explored in other blog posts. And remember, everyone is different and so everyone learns a language differently – and once you have worked out which type of language learner you are and which techniques work for you, you will have a recipe for success!

Grouping By Theme/Context

You will have heard it before, context is key to language learning. Children learn that “hello” means “hello” because people say it to them when they see them for the first time and not when they are going away (that’s “bye bye”). They learn that “yummy” is an adjective to describe food but not, say books. We are no different from children in the way we learn. When we associate words with a context, we learn and remember them more quickly. I can assure you that you will remember that “cucchiaio” means “spoon” in Italian much more readily if you are using it to eat soup with than if you ask, “how do you say ‘spoon’?” in a car trip across the Alps and then try to remember it after a fun day’s skiing.

So, how do you group words by theme? Try drawing and labelling a picture. Draw a picture of the kitchen in your house and label all the things in there, draw a picture of the human body and label the parts, draw a picture of a car and label that. If you are learning words that go together or make up a whole, you will remember them more easily. Learn words about the weather together, learn how to say whether you are well/ill/have a headache/have a toothache together. Learn words you will use in the classroom together. Learn words and phrases you will need to use in a restaurant (“I’ll have a…”, “the bill, please!”). You will remember them better than if you are learning random clusters of words.

Making Nouns and Adjectives out of Verbs

I remember when I learnt this technique to learn three words for the price of one – I was literally excited because it opened my eyes to a new, efficient way of learning!

Think of a verb in the language you are learning. Let’s take “éclairer” (to brighten/become clear/clarify) in French. If we look in a dictionary near “éclairer”, we will see “éclaircie” – a clear patch in a cloudy sky (which metaphorically means an improvement in a difficult situation), and “éclaircissement”, clarification. We will also see the adjective “éclairé”, informed/enlightened. With this exercise, we have just learnt four words instead of just one. Try this with verbs you can think of. You can combine this grouping technique with tools such as tables and diagrams if this will help you.

Learning Synonyms

Another way to learn several words instead of just one word at a time is to learn synonyms. It is a good idea to use a thesaurus for this exercise. Think of the word “hungry” in English. How many synonyms can you think of? “Famished”? “Starving”? “Ravenous”? “Peckish”? Try looking up synonyms in the language you are learning and use them in conversation instead of the standard word. This will help you remember them because you are using them and may impress your friends!

Grouping Words by Prefix

It is likely that the language you are learning will use prefixes (beginnings of words) that have a specific meaning. Let’s look at Spanish. If we know that “des-“ means “un-“ or “not”, we can work out that “desconocido” (des-conocido) means “unknown” and “desbloquear” means “to unblock”. “Descubrir”, literally “to uncover”, means “to find out/discover” (it’s similar in English). This amazing word is similar in a lot of languages – “scoprire” in Italian is “to uncover” or “discover”, “ontdekken” in Dutch is the same and “odkrywać” in Polish is similar. These words all have prefixes (s-, ont-, od-) which also mean “un-”, “away” or “from” in the respective languages. If we identify these little parts of words, we can understand the gist if not the meaning of new words and remember them because of their theme (such as “un-“ meanings).

Can you think of other ways to group vocabulary together? Share them with us in the comments!

Suzannah Young

- Размер: 211 Кб

- Количество слайдов: 39

Download Article

Download Article

Memorizing words quickly is often a very daunting task. Sometimes we have word lists — like a list of vocabulary words — that are so overwhelming that we are overcome by the magnitude of the task rather than spending our time getting started. Fortunately, there are a number of methods of memorizing words quickly that take a potentially overwhelming task and make it fun. Ultimately, you need to remember that knowing words and vocabulary is not a bad thing – it will help you meet your goal and enrich your intellect in the process.

-

1

Have the words you need to memorize printed out in front of you. It doesn’t matter what the source of the words is — a textbook, a vocabulary list your teacher gave you, a list of words from the internet — as long as you have them in front of you so you can work on memorizing them. You may even want to write down the words yourself to help even more with your memorization.

- For example, if you’re trying to memorize a list of vocabulary words in a textbook, you could write out the words by hand on a sheet of paper.

-

2

Break the words up into smaller groups. Divide the words into smaller, more manageable groups. Breaking your words up will make it so you can more easily create word association and mnemonic devices to memorize your words. If you want to memorize them in order, that’s okay — you don’t need to break the words up into smaller groups.[1]

- Use your best judgement when and if you’ll be breaking your list up and moving words around.

Advertisement

-

3

Underline the first letter of every word in the groups. You’re going to use the first letter of every word to create memory devices that will make it easier to memorize the words. You’ll do this two ways: either creating a sentence or an acronym.[2]

- The first letter of every word will create an acronym.

- For the order of operations in math (Parentheses, Exponents, Multiplication, Division, Addition, Subtraction), you’ll have p, e, m, d, a, and s. This will spell P.E.M.D.A.S.

- This works best with word lists of 10 or less.

-

4

Memorize the acronym. Now spend a little time memorizing your acronym (P.E.M.D.A.S.) This shouldn’t take too long, and before long you’ll have it memorized. This might be as far as you need to go with this approach.[3]

-

5

Create a sentence to remember based on the first letter of every word. If you want to take an extra step to memorize your word groups, take the first letter of every word (your acronym), and create a sentence based on those letters. You’ll do this by using any word that begins with the first letter of the words in your word groups. For instance:

- You won’t be using the original word, simply another word that begins with the same first letter.

- To remember the order of operations in math (Parentheses, Exponents, Multiplication, Division, Addition, Subtraction), take P.E.M.D.A.S. and assign words to it.

- P.E.M.D.A.S. can be transformed into “Please excuse my dear aunt Sally” or any other number of short sentences.[4]

-

6

Review your word groups, acronyms and mnemonic devices. After you’ve memorized a few of your word groups, stop and review them. Don’t spend hours doing this, as your brain will probably be overloading. This method works best when you provide enough time in between memorization.[5]

Advertisement

-

1

Have the list of words you need to memorize printed out in front of you. These words can come from a textbook, the internet, or a handout you got from a teacher. Either way, it’s best to have the words right in front of you so you can memorize them more easily.

- You can also write the words out by hand on a piece of paper, which will help you memorize them even more.

-

2

Draw a picture for each word. Drawing a picture that describes each word will help you remember it better. Make sure to maintain the original meaning of each word as best as you can.[6]

- Nouns might be easiest, as you’ll just have to draw the person, place, or thing.

- Adjectives will be somewhat easy. Words like “big” and “beautiful” will be relatively easy to draw.

- Verbs might be more difficult. For a word like “associate” try to draw its meaning (the connection between things).

-

3

Create a word association web. Word association webs will help you remember words by associating them with other words. This is a great visual way of memorizing words quickly and will complement other visual approaches to memorization.

- Write the word you want to remember on the center of a sheet of paper.

- Draw lines outward from the center connecting the center word to other words that you associate with it. For example, if the word is “winter” draw a line outward connecting it to “snow” and another line on the other side connecting it to “freezing” and another line on the side connecting it to “ice.” Repeat this process outward until you’re confident you will remember it.

- This should not take more than 3-5 minutes per word.

-

4

Create a picture story. Creating a picture story is similar to creating a word or sentence story, but instead of writing it out, you’ll be drawing your story. This method works great for very visual and artistic learners who might be overwhelmed with writing out vocabulary words.

- Take your list of words and quickly draw a picture for each word.

- Try to maintain the original meaning of the word, if you can.

- Organize the pictures so they make a story you can remember.

- This will work great when paired with word association and mnemonic devices.

-

5

Spend time reviewing your picture, your web, and your story. The more time you spend looking at and thinking about your visual aids, the better prepared you’ll be and the better you’ll remember your word list. Spread this out over a couple days if possible. Review your visual aids when you have time. Consider:

- Reviewing them while eating.

- Looking at them when you have downtime in between other tasks and projects.

- Spending a couple minutes looking at them and thinking about them when you wake up and before you go to sleep.

Advertisement

-

1

Place the list of words you need to learn right in front of you. Having your list of vocabulary words — whether they came from a textbook, the internet, or somewhere else — directly in front of you will make them easier to memorize.

- Handwriting your list of words on a sheet of paper is a great way to kick off the memorization process.

-

2

Arrange the words in story or sentence form. After you’ve got your list, arrange the words in a way so that you can create a couple sentences or a story with the words. You don’t want to just build clunky sentences, though. Consider:

- Rhyming words.

- Pairing words cleverly.

- This works best if you don’t have to know the words in a certain order.

- You will be keeping the meaning of each word.

-

3

Find a memorable tune to accompany your words. Finding a memorable tune to accompany your arranged words will help you remember them more easily. Think about popular songs or songs that you can easily remember the tune to. Consider the tunes from:[7]

- Your current favorite pop songs.

- Traditional folk tunes like “Molly Malone” or “John Brown’s Body.”

- Pledges, anthems, or hymns, like the American Pledge of Allegiance, the American Marine hymn, or Hail Britannia.

-

4

Say or sing the words and their meaning to a tune. After you’ve arranged your words, say the words to yourself out loud. Afterwards, sing or rap the words. This way, you’ve taken your word list, associated with a tune, and now have your own song to memorize! You can sing it to yourself when you’re taking a test or trying to remember your word list.

-

5

Sing, repeat or play the song or tune. As you go about your daily chores or travel, sing or repeat the song or tune over and over again. If you’ve recorded the song or tune (you singing/saying the words over and over), play it back while you’re resting, or even sleeping. If you do record it, put the tune, rap or song on loop.

-

6

Continue this until you are comfortable. Keep doing this until it feels as if the words and their meanings have stuck in your memory. Music is a great aid to memory, which is why it’s so easy to remember pop songs. As a result, this should be a very pleasant and potentially enjoyable way of getting your work done.

Advertisement

Add New Question

-

Question

How can I memorize a test quickly?

Christopher Taylor is an Adjunct Assistant Professor of English at Austin Community College in Texas. He received his PhD in English Literature and Medieval Studies from the University of Texas at Austin in 2014.

English Professor

Expert Answer

-

Question

How can I remember vocabulary words?

Christopher Taylor is an Adjunct Assistant Professor of English at Austin Community College in Texas. He received his PhD in English Literature and Medieval Studies from the University of Texas at Austin in 2014.

English Professor

Expert Answer

Support wikiHow by

unlocking this expert answer.To remember vocabulary words, try to create associations with the words, whether through mnemonic devices, sound patterns, or by visualizing the words. Since flashcards encourage «active recall,» they are also an effective method for tasks related to repetition and memorization.

-

Question

How can I memorize faster?

Christopher Taylor is an Adjunct Assistant Professor of English at Austin Community College in Texas. He received his PhD in English Literature and Medieval Studies from the University of Texas at Austin in 2014.

English Professor

Expert Answer

See more answers

Ask a Question

200 characters left

Include your email address to get a message when this question is answered.

Submit

Advertisement

-

Try using the words in your day-to-day life with people you come across every day. It will make you even more confident.

-

It helps to Google images to find things that might inspire you.

-

Read/write the word over and over again saying each letter.

Show More Tips

Advertisement

-

Do not make your word association too complicated, use what comes first to your mind.

Advertisement

References

About This Article

Article SummaryX

To memorize words quickly, start by writing the words down in a list to study from, since just writing it out can help you remember. Then, underline the first letter of each word and create an acronym that you can easily remember. For simple words, try drawing pictures of each word, keeping the original meaning as much as you can. If these tricks don’t work, set the words to a catchy song and sing it repeatedly until you’ve memorized it. For tips from our Language reviewer on more ways to memorize words, keep reading!

Did this summary help you?

Thanks to all authors for creating a page that has been read 376,379 times.

Reader Success Stories

-

«It’s the best way to memorize vocabulary by listening to music.»

Did this article help you?

By

Last updated:

December 7, 2022

There are many effective ways to learn English vocabulary—and you can find the perfect one for you right here.

For some people, simply memorizing a word’s definition is enough. Others need entertaining or unique techniques to truly remember a word.

No matter what type of learner you are, we’ll show you how to learn English vocabulary successfully.

Contents

- Make Vocabulary Building Easier by Knowing Your Personal Learning Style

- These 13 Questions Will Reveal the Best Way to Learn English Vocabulary for You

-

- 1. Do Keep To-do Lists?

- 2. Do You Love a Good Conversation?

- 3. Do You Spend Your Weekends Playing Board Games?

- 4. Are You a Movie Buff?

- 5. Are You Good at Spotting Patterns?

- 6. Does Traditional Studying Work for You?

- 7. Are You a Writer (or a Future Writer)?

- 8. Are You Detail-oriented?

- 9. Are You a Bookworm?

- 10. Do You Learn by Doing?

- 11. Do You Love to Travel?

- 12. Are You a Social Butterfly?

- 13. Are You Curious and Always Asking Questions?

Download:

This blog post is available as a convenient and portable PDF that you

can take anywhere.

Click here to get a copy. (Download)

Make Vocabulary Building Easier by Knowing Your Personal Learning Style

What kind of learner are you?

Some people learn best by listening, others learn best by writing. You can’t know which learning tips and methods will work best for you until you know which kind of learner you are.

For example, if you remember words better when you write them down, you should try something fun and productive that involves writing. Try writing a blog.

If you remember words better through repetition, use English vocabulary exercises to boost your knowledge.

It all depends on how you learn best.

Once you figure that out, you are ready to start really learning!

If you are not sure which learning style works best for you, then you can try all of the suggested ways to learn English below. You will learn a lot about yourself and your brain by trying different methods.

These 13 Questions Will Reveal the Best Way to Learn English Vocabulary for You

Words are all around us. Sitting down and looking up words in a dictionary is not the only way to learn English words. You can improve English vocabulary by talking with English speakers, watching TV shows in English, writing in a journal… we’ll show you all of it and more below.

Remember, you may answer “yes” to more than one of our questions below. That’s okay! You can try multiple methods to learn English vocabulary, and mix and match the best ones for you.

1. Do Keep To-do Lists?

Your best way to learn English vocabulary: write down all the new words you hear.

If you’re the kind of person who loves keeping lists—like grocery lists, to-do lists for errands, project ideas, etc.—then use that to your advantage.

Keep a vocabulary list to remember new words that you encounter in English. Put this list somewhere portable (easy to carry around) like a little notebook or your phone, so you can access it from anywhere.

As you find words you don’t know, write them down. Make sure to keep plenty of space between words so that you can write more about the words later. When you get the chance (at the end of the day, or at the end of the week) find out what these words mean. You can write the definition however you want, translated to your native language, copied from the English dictionary or written in your own original words.

However you do it, we recommend also writing down the part of speech (e.g., verb, noun, adjective), different versions of the word (for example, if you write down the word “fish” you could also write down information for fishing, fishy, fisherman, etc.), and a full sentence using the word.

After you have been recording lists for a while, go back and read your old lists. How well do you remember those words from the older lists? Take any words you have forgotten from your old lists and add them to your new list. This is a good way to make sure you continue to improve English vocabulary as you advance.

2. Do You Love a Good Conversation?

Your best way to learn English vocabulary: use new words in conversation.

It can be easy to forget about words you’ve already learned as you move on to new ones. This is especially true for common words and words that you’re not sure how to use.

Try using your new words during the week as often as you can. The more you use the words in English conversations, the better you’ll remember them.

An English language exchange offers a great opportunity to use your new English words in real conversations. If you’re not able to have as many English conversations as you’d like, keep a diary and simply write about your day using the words, or just talk to yourself!

3. Do You Spend Your Weekends Playing Board Games?

Your best way to learn English vocabulary: play English-language board games.

Who said that studying can’t be all fun and games?

English board games like Scrabble offer great ways to learn new words.

There are lots of games you can play to strengthen your vocabulary. In fact, you can find a list of vocabulary board games right here!

Games are a good way to learn because they make learning fun, and they help give you context for your new words. That means you’re giving the word you learn an extra meaning.

For example, you might remember the way that the word was used during the game. You might remember your friend laughing about how the word was used. You might remember that it was very hard to think of that word the first time while playing! Having a real-life memory attached to that word makes it much more memorable.

4. Are You a Movie Buff?

One great way to learn English vocabulary: watch real English language movie clips online.

One of the best ways to learn new vocabulary words is to hear them being used. When you’re talking to an actual person, you might not have time to write down any new words or to look them up in the dictionary.

That’s why videos are a great option for vocabulary learning. Movie clips specifically can help you improve your English vocabulary without being overwhelming. Some virtual immersion platforms make use of movie clips and other videos to teach English.

FluentU, for example, has a dedicated section for excerpts from movies and TV shows. Each video has interactive subtitles that you can click for definitions and example sentences. And you can take a review quiz afterward to test your knowledge of the material.

5. Are You Good at Spotting Patterns?

Your best way to learn English vocabulary: group similar English words together.

As we already mentioned, it is better (and easier) to learn new vocabulary words by giving them some context. One way to do this is to remember words in a sentence. This is a great option because you will not only know the word, but you will also know exactly how to use it in conversation.

Another easy way to learn English vocabulary is to remember words by groups. If you just learned the word “humongous” (very large), you can memorize it by thinking of a group of words getting bigger and bigger—large, huge, humongous. This also gives the chance to learn even more words at the same time.

For example: large, humongous, gargantuan. What do you think “gargantuan” means?

6. Does Traditional Studying Work for You?

Your best way to learn English vocabulary: use English dictionary websites.

Sure, you can use an old-fashioned dictionary to look up a word. But many dictionary websites these days have so much more to offer!

Explore dictionary websites like Vocabulary.com and Dictionary.com and you’ll find lots of resources and things to do or read that can help you learn new words. Online dictionaries often have interesting word-related blogs, games you can play and “word of the day” newsletter subscriptions.

Merriam-Webster even has a learner’s dictionary (with a “word of the day” option that teaches you a new English word every day) with useful words for people learning English. Perfect!

7. Are You a Writer (or a Future Writer)?

Your best way to learn English vocabulary: keep an English writing blog.

Reading blogs is a nice way to learn new words, but writing a blog is even better!

You can start a free blog on many websites like WordPress and Tumblr. What you write in your blog and who sees it is all up to you. You can write about fashion or cats… or cat fashion—write about whatever interests you.

As you write, you will probably need to look up words in a dictionary. As you look up words, you will start to remember many of them! Using them in your blog gives them great context which will help your memory. You will learn exactly how to use them in writing.

Choose a list of words that you want to use before you write the blog. Writing with these words will help you practice and remember them.

Share your blog posts with friends and native speakers. Ask them for feedback. This will help make sure you used your words correctly.

8. Are You Detail-oriented?

Your best way to learn English vocabulary: break words into their parts.

Many words can be broken down into smaller parts. For example, the word “dictionary” comes from the Latin word dictio, which means “to speak.”

This is called the root of the word. A root word is a base used to create many words. Now that you know the root word dictio, you might notice it in other words too, like dictate, dictator and contradict. Even if you don’t know what the words mean, you now know that they have something to do with speaking.

Learning word parts is a great idea because you don’t just learn one word, you also learn other words that use these parts. You will also be better at guessing the meanings of new English words, because you will know what some parts of these words mean.

There are more parts to words than roots. Along with roots, words use prefixes (word parts that come in the beginning of the word) and suffixes (word parts that come at the end of a word).

Many dictionaries break down the word into these parts and tell you where these parts are from. You can find a list of word roots on LearnThatWord, and a more complete list that includes prefixes and suffixes on Macroevolution.

9. Are You a Bookworm?

Your best way to learn English vocabulary: read English books.

Reading is a good way to learn new words, but what you read can also make a huge difference in how much you learn.

Choose books that are a little bit challenging for you, and you will learn a lot more than if you read at your level. If you read a book at your level, you may already know all the words. If you read a challenging book, you will need to learn many new words.

You can also try reading special vocabulary books. These are fiction books that include over 1,000 vocabulary words and their definitions! These books are available to buy online, and can be found at ThriftBooks or by searching Amazon.

10. Do You Learn by Doing?

Your best way to learn English vocabulary: take English vocabulary quizzes.

For many people, memorization is simply not enough. You have to practice and apply what you’ve learned—in other words, “learn by doing”—to truly remember the information.

Try using quizzes to make sure you still remember each word you learned, and to remind yourself of the words you learned a while ago. There are many vocabulary quizzes you can use to test yourself. You can find some at Vocabtest, Merriam-Webster and Vocabulary.com, among many others. Don’t forget that FluentU will always keep you practicing the vocabulary words you learned while watching videos!

11. Do You Love to Travel?

Your best way to learn English vocabulary: link new words to English-speaking cultures.

There are a number of different kinds of English around the world. British and American English might seem the same, but there are many little differences.

If you love to travel and discover new cultures, consider how English words are used, pronounced or spelled in different cultures. This will make them seem more interesting and memorable to you—plus, it will be helpful if you visit different English-speaking countries!

The word color, for example, is spelled as “colour” in British English. British people used the words “brilliant” and “cheers” often, but Americans prefer to say “cool” instead of “brilliant” and “see you” instead of “cheers.”

This is also a helpful idea if you’re already focused on one specific type of English. When you are learning new words, keep in mind which country you plan to visit, live in or work in. You should learn British English if you plan to go to England, American English if you plan to go to the U.S., and so on.

12. Are You a Social Butterfly?

Your best way to learn English vocabulary: study new words with English learning friends.

Learning is easier and more fun when you do it with others!

Find a group of friends who want to learn English with you, get an online native speaking buddy or join a website with other learners. Whatever you choose to do, you will benefit greatly from working with others.

One excellent group learning program you can join is called Toastmasters. This group has meeting spots all over the world, and it helps people learn to speak in public. This can be a huge help to you if you have trouble speaking English with others!

Another great idea is to talk to other English learners on Facebook. There are many Facebook pages for English learners. Some are pages where English learners have created an online community for support and friendship. Other pages have actual native speakers helping the group learn. Find one, and your studying will suddenly get much easier.

13. Are You Curious and Always Asking Questions?

Your best way to learn English vocabulary: ask “what does that mean?” as often as you can!

Finally, never be afraid to ask questions!

If someone uses words you don’t understand, ask them “what does that mean?” Many people are very patient and understanding if you tell them that you’re learning English. In fact, many will actually enjoy helping you!

So, have you found your personal best way to learn English vocabulary? Don’t be afraid to try everything and discover how to learn English vocabulary in a way that works for you. Study hard but have fun, and before you know if you’ll have a gargantuan vocabulary!

Download:

This blog post is available as a convenient and portable PDF that you

can take anywhere.

Click here to get a copy. (Download)

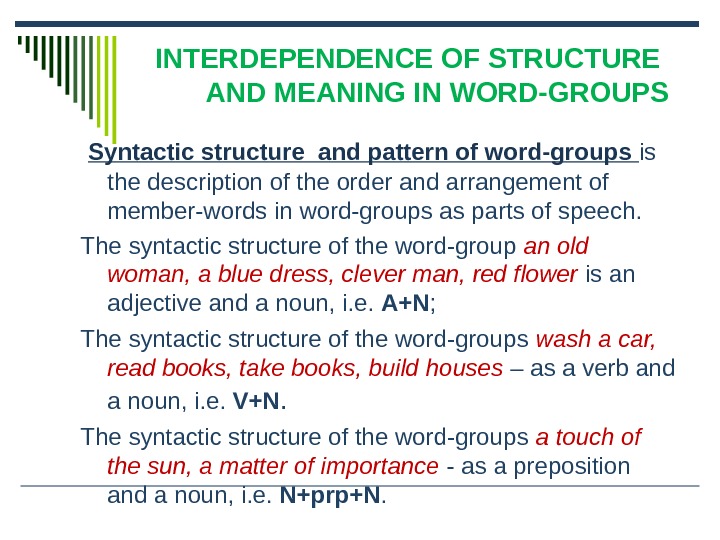

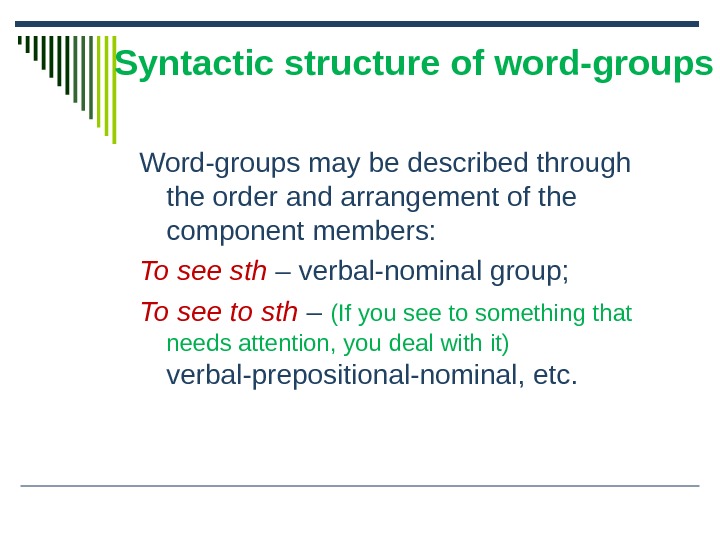

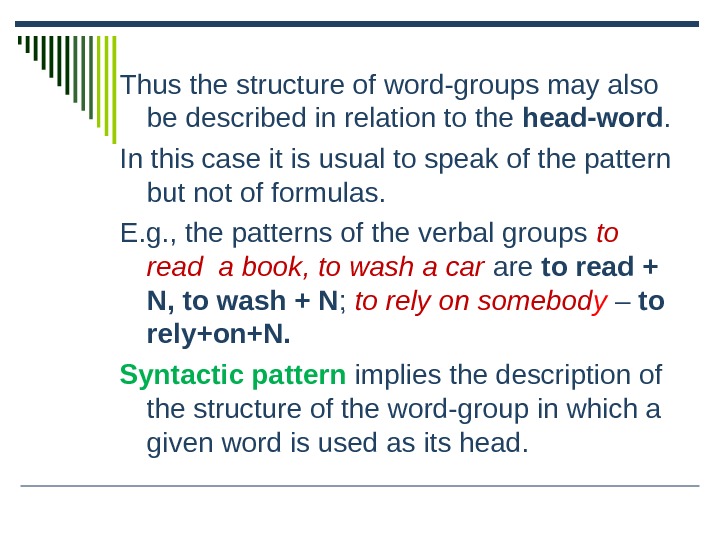

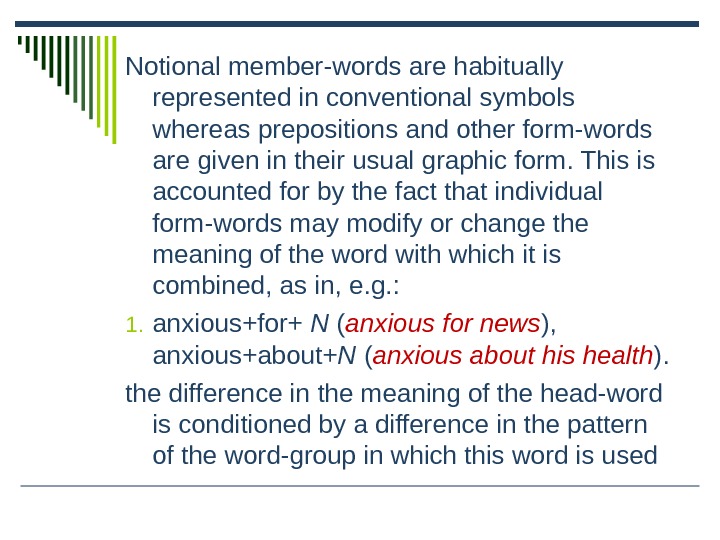

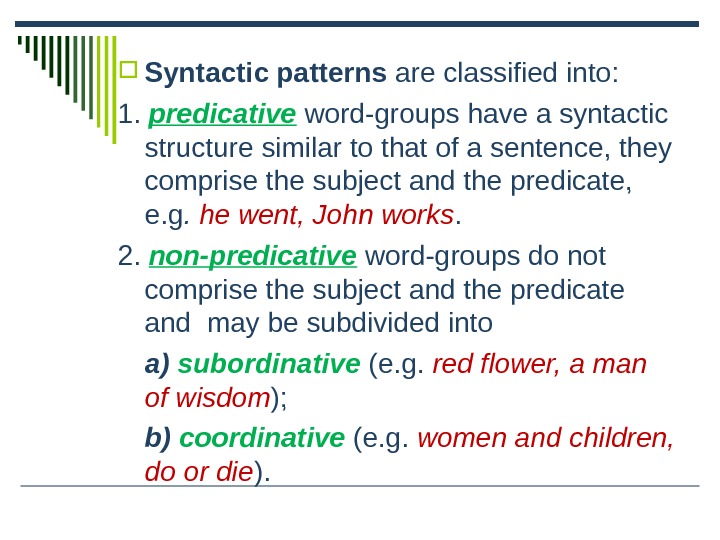

The word-group theory in Modern English

word-group

theory in Modern English

Content

Introduction

.

Definition and general characteristics of the

word-group

.

Classification of word-groups

.

Semantic features of word-groups

.

Motivated and non-motivated word-groups

.

Phraseological word-groups

Introduction

is a branch of linguistics — the

science of language. Lexicology as a branch of linguistics has its own aims and

methods of scientific research. Its basic task — being a study and systematic

description of vocabulary in respect to its origin, development and its current

use. Lexicology is concerned with words, variable word-groups, phraseological

units and morphemes which make up words.the object of the linguistic research

within the frameworks of the lexicological analysis, word-groups draw much

attention of different scientists at different stages of the research

history.linguists as Shveitser, Arnold, Nikitin, Akhmanova, Marchenko, and many

others devoted their research papers to the matter of the word-groups, their

classification, semantic features, and other specific characteristics. They

have contributed linguistic research with a number of works, connected with

this lexical units. The matter of the word-group thorough study is topical with

a glance at their specific features, some phraseological peculiarities and

semantic-grammatical structure.above-mentioned aspects have predetermined our

choice of the topic of the present report «The word-group theory in Modern

English».object of the investigation are word-groups of Modern

English.subject of the present report includes specific features and

characteristics of word-groups.purpose of the report writing is to investigate

word-groups functioning in the Modern English language.purporse of the report

has predetermined the following tasks of the investigation:

to define the notion of the

word-group and outline its general characteristics;

to suggest the classification of the

word-group;

to consider semantic features of

word-groups;

to characterize motivated and

non-motivated word-groups;

to specify peculiar features of

phraseological word-groups.practical value of the present report is performed

by the possibility of using its materials for the further thorough study of

this matter.

1. Definition and general

characteristics of the word-group

word group is the simplest

nonpredicative (as contrasted to the sentence) unit of speech. The word group

is formed on a syntactic pattern and based on a subordinating grammatical

relationship between two or more content words. This relationship may be one of

agreement, government, or subordination. The grammatically predominant word is

the main element of the word group, and the grammatically subordinated word the

dependent element.word group denotes a fragment of extralinguistic reality. The

word group combines formally syntactic and semantically syntactic features.

Such features reveal the compatibility of grammatical and lexical meanings with

the structure of the object-logical relations that these meanings

reflect.groups may be free or phraseological. Free word groups are formed in

accordance with regular and productive combinative principles; their meanings

may be deduced from those of the component words.are a lot of definitions

concerning the word-group. The most adequate one seems to be the following: the

word-group is a combination of at least two notional words which do not

constitute the sentence but are syntactically connected. According to some

other scholars (the majority of Western scholars and professors B.Ilyish and

V.Burlakova — in Russia), a combination of a notional word with a function word

(on the table) may be treated as a word-group as well. The problem is

disputable as the role of function words is to show some abstract relations and

they are devoid of nominative power. On the other hand, such combinations are

syntactically bound and they should belong somewhere.characteristics of the

word-group are:

) As a naming unit it differs from a

compound word because the number of constituents in a word-group corresponds to

the number of different denotates: a black bird — чорний птах (2), a blackbird

— дрізд (1);loud speaker (2), a loudspeaker (1).

) Each component of the word-group

can undergo grammatical changes without destroying the identity of the whole

unit: to see a house — to see houses.

) A word-group is a dependent

syntactic unit, it is not a communicative unit and has no intonation of its own

[4; p. 28].

groups can be classified on the

basis of several principles:

a)

According to the type of syntagmatic

relations: coordinate (you and me), subordinate (to see a house, a nice dress),

predicative (him coming, for him to come),

b)

According to the structure: simple

(all elements are obligatory), expanded (to read and translate the text —

expanded elements are equal in rank), extended (a word takes a dependent

element and this dependent element becomes the head for another word: a beautiful

flower — a very beautiful flower).

1) Subordinate

word-groups.word-groups are based on the relations of dependence between the

constituents. This presupposes the existence of a governingwhich is called the

head and the dependent element which is called the adjunct (in noun-phrases) or

the complement (in verb-phrases).to the nature of their heads, subordinate

word-groups fall into noun-phrases (NP) — a cup of tea, verb-phrases (VP) — to

run fast, to see a house, adjective phrases (AP) — good for you, adverbial

phrases (DP) — so quickly, pronoun phrases (IP) — something strange, nothing to

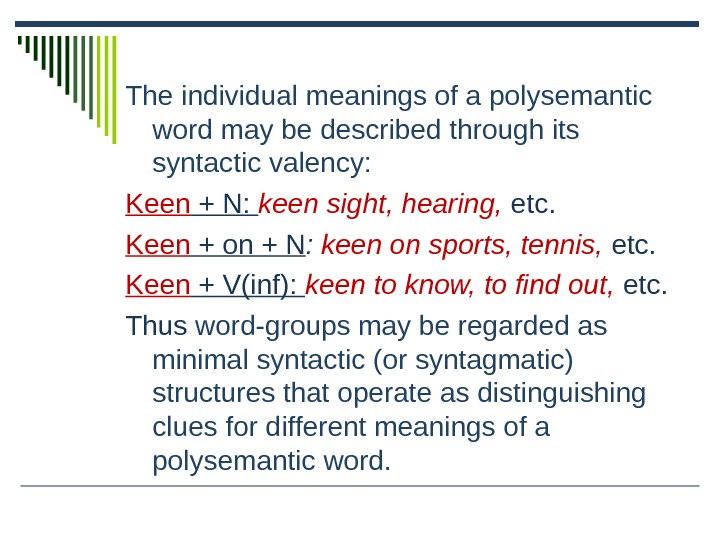

do.formation of the subordinate word-group depends on the valency of its

constituents. Valency is a potential ability of words to combine. Actual

realization of valency in speech is called combinability [6; p. 162-163].

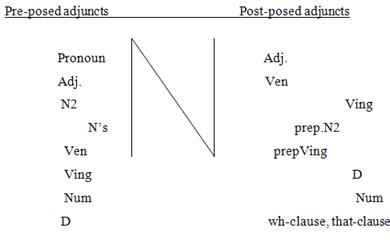

) The noun-phrase (NP).word-groups

are widely spread in English. This may be explained by a potential ability of

the noun to go into combinations with practically all parts of speech. The NP

consists of a noun-head and an adjunct or adjuncts with relations of

modification between them. Three types of modification are distinguished here:

a)

Premodification that comprises all

the units placed before the head: two smart hard-working students. Adjuncts used

in pre-head position are called pre-posed adjuncts.

b)

Postmodification that comprises all

the units all the units placed after the head: students from Boston. Adjuncts

used in post-head position are called post-posed adjuncts.

c)

Mixed modification that comprises

all the units in both pre-head and post-head position: two smart hard-working

students from Boston.

) Noun-phrases with pre-posed

adjuncts.noun-phrases with pre-posed modifiers we generally find adjectives, pronouns,

numerals, participles, gerunds, nouns, nouns in the genitive case (see the

table) [8; p. 43]. According to their position all pre-posed adjuncts may be

divided into pre-adjectivals and adjectiavals. The position of adjectivals is

usually right before the noun-head. Pre-adjectivals occupy the position before

adjectivals. They fall into two groups: a) limiters (to this group belong

mostly particles): just, only, even, etc. and b) determiners (articles,

possessive pronouns, quantifiers — the first, the last).of nouns by nouns (N+N)

is one of the most striking features about the grammatical organization of

English. It is one of devices to make our speech both laconic and expressive at

the same time. Noun-adjunct groups result from different kinds of transformational

shifts. NPs with pre-posed adjuncts can signal a striking variety of

meanings:peace — peace all over the worldbox — a box made of silverlamp — lamp

for tableslegs — the legs of the tablesand — sand from the riverchild — a child

who goes to schoolgrammatical relations observed in NPs with pre-posed adjuncts

may convey the following meanings:

1)

subject-predicate relations: weather

change;

2)

object relations: health service,

women hater;

3)

adverbial relations: a) of time:

morning star,

b) place: world peace, country

house,) comparison: button eyes,) purpose: tooth brush.is important to remember

that the noun-adjunct is usually marked by a stronger stress than the

head.special interest is a kind of ‘grammatical idiom’ where the modifier is

reinterpreted into the head: a devil of a man, an angel of a girl.

) Noun-phrases with post-posed

adjuncts.with post-posed may be classified according to the way of connection

into prepositionless and prepositional. The basic prepositionless NPs with post-posed

adjuncts are: Nadj. — tea strong, NVen — the shape unknown, NVing — the girl

smiling, ND — the man downstairs, NVinf — a book to read, NNum — room

ten.pattern of basic prepositional NPs is N1 prep. N2. The most common

preposition here is ‘of’ — a cup of tea, a man of courage. It may have quite

different meanings: qualitative — a woman of sense, predicative — the pleasure

of the company, objective — the reading of the newspaper, partitive — the roof

of the house.

) The verb-phrase.VP is a definite

kind of the subordinate phrase with the verb as the head. The verb is

considered to be the semantic and structural centre not only of the VP but of

the whole sentence as the verb plays an important role in making up primary

predication that serves the basis for the sentence. VPs are more complex than

NPs as there are a lot of ways in which verbs may be combined in actual usage.

Valent properties of different verbs and their semantics make it possible to

divide all the verbs into several groups depending on the nature of their

complements [7; p. 91].of verb-phrases.can be classified according to the

nature of their complements — verb complements may be nominal (to see a house)

and adverbial (to behave well). Consequently, we distinguish nominal, adverbial

and mixed complementation.complementation takes place when one or more nominal

complements (nouns or pronouns) are obligatory for the realization of potential

valency of the verb: to give smth. to smb., to phone smb., to hear smth.(smb.),

etc.complementation occurs when the verb takes one or more adverbial elements

obligatory for the realization of its potential valency: He behaved well, I

live …in Kyiv (here).complementation — both nominal and adverbial elements are

obligatory: He put his hat on he table (nominal-adverbial).to the structure VPs

may be basic or simple (to take a book) — all elements are obligatory; expanded

(to read and translate the text, to read books and newspapers) and extended (to

read an English book).

) Predicative word-groups.word

combinations are distinguished on the basis of secondary predication. Like

sentences, predicative word-groups are binary in their structure but actually

differ essentially in their organization. The sentence is an independent

communicative unit based on primary predication while the predicative

word-group is a dependent syntactic unit that makes up a part of the sentence.

The predicative word-group consists of a nominal element (noun, pronoun) and a

non-finite form of the verb: N + Vnon-fin. There are Gerundial, Infinitive and

Participial word-groups (complexes) in the English language: his reading, for

me to know, the boy running, etc.)

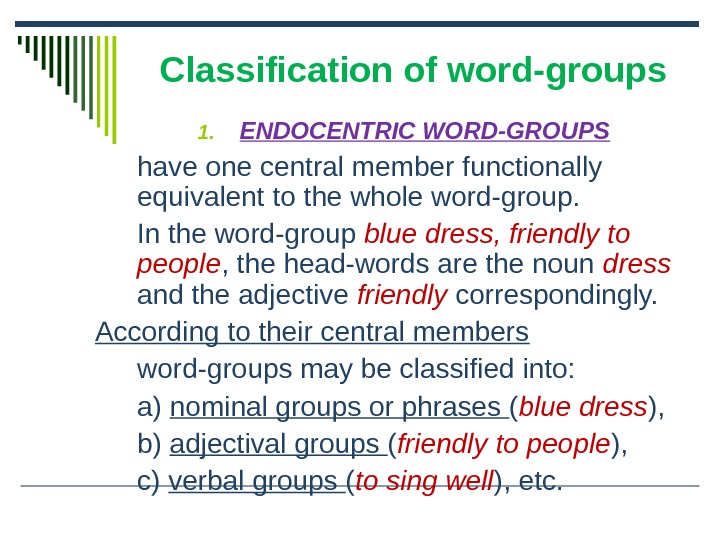

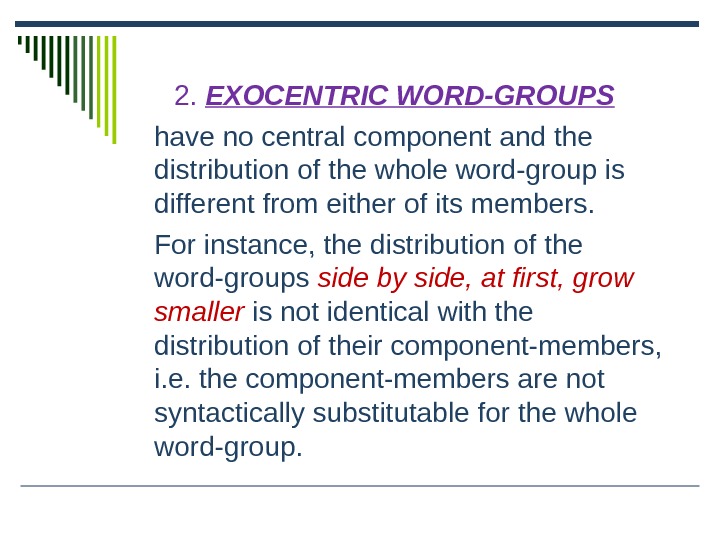

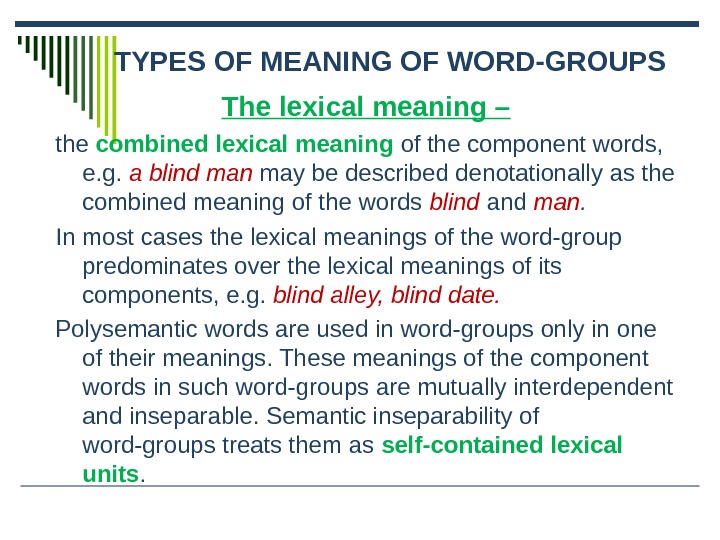

. Semantic features of word-groups

word-group is the largest two-facet

lexical unit comprising more than one word but expressing one global

concept.lexical meaning of the word groups is the combined lexical meaning of

the component words. The meaning of the word groups is motivated by the

meanings of the component members and is supported by the structural pattern.

But it’s not a mere sum total of all these meanings! Polysemantic words are

used in word groups only in 1 of their meanings. These meanings of the

component words in such word groups are mutually interdependent and inseparable

(blind man — «a human being unable to see», blind type — «the

copy isn’t readable).groups possess not only the lexical meaning, but also the

meaning conveyed mainly by the pattern of arrangement of their constituents.

The structural pattern of word groups is the carrier of a certain semantic component

not necessarily dependent on the actual lexical meaning of its members (school

grammar — «grammar which is taught in school», grammar school —

«a type of school»). We have to distinguish between the structural

meaning of a given type of word groups as such and the lexical meaning of its

constituents [11; p. 62-64].is often argued that the meaning of word groups is

also dependent on some extra-linguistic factors — on the situation in which

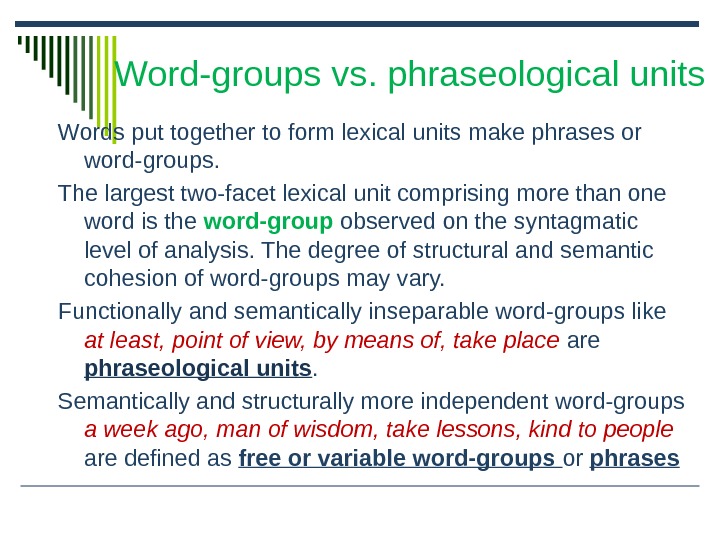

word groups are habitually used by native speakers.put together to form lexical

units make phrases or word-groups. One must recall that lexicology deals with

words, word-forming morphemes and word-groups.degree of structural and semantic

cohesion of word-groups may vary. Some word-groups, e.g. at least, point of

view, by means, to take place, etc. seem to be functionally and semantically

inseparable. They are usually described as set phrases, word-equivalents or

phraseological units and are studied by the branch of lexicology which is known

as phraseology. In other word-groups such as to take lessons, kind to people, a

week ago, the component-members seem to possess greater semantic and structural

independence. Word-groups of this type are defined as free word-groups or

phrases and are studied in syntax.discussing phraseology it is necessary to

outline the features common to various word-groups irrespective of the degree

of structural and semantic cohesion of the component-words [18; p. 231].are two

factors which are important in uniting words into word-groups:

the lexical valency of words;

. Motivated and non-motivated

word-groups

word group semantic

motivated

The term motivation is used to

denote the relationship existing between the phonemic or morphemic composition

and structural pattern of the word on the one hand and its meaning on the

other.are three main types of motivation:

) phonetical

) morphological

) semantic

. Phonetical motivation is used when

there is a certain similarity between the sounds that make up the word. For

example: buzz, cuckoo, gigle. The sounds of a word are imitative of sounds in

nature, or smth that produces a characteristic sound. This type of motivation

is determined by the phonological system of each language.

. Morphological motivation — the

relationship between morphemic structure and meaning. The main criterion in

morphological motivation is the relationship between morphemes. One-morphemed

words are non-motivated. Ex — means «former» when we talk about humans

ex-wife, ex-president. Re — means «again»: rebuild, rewrite. In

borrowed words motivation is faded: «expect, export, recover (get

better)». Morphological motivation is especially obvious in newly coined

words, or in the words created in this century. In older words motivation is

established etymologically.structure-pattern of the word is very important too:

«finger-ring» and «ring-finger». Though combined lexical

meaning is the same. The difference of meaning can be explained by the arrangement

of the components.motivation has some irregularities: «smoker» — si

not «the one who smokes», it is «a railway car in which

passenger may smoke».degree of motivation can be different:

«endless» is completely

motivated

«cranberry» is partially

motivated: morpheme «cran-» has no lexical meaning.

. Semantic motivation is based on

the co-existence of direct and figurative meanings of the same word within the

same synchronous system. «Mouth» denotes a part of the human face and

at the same time it can be applied to any opening: «the mouth of a

river». «Ermine» is not only the anme of a small animal, but

also a fur. In their direct meaning «mouth» and «ermine»

are not motivated [13; p. 86].compound words it is morphological motivation

when the meaning of the whole word is based on direct meanings of its

components and semantic motivation is when combination of components is used

figuratively. For example «headache» is «pain in the head»

(morphological) and «smth. annoying» (sematic).the connection between

the meaning of the word and its form is conventional (there is no perceptible

reason for the word having this phonemic and morphemic composition) the word is

non-motivated (for the present state of language development). Words that seem

non-motivated now may have lost their motivation: «earn» is derived

from «earnian — to harvest», but now this word is non-motivated.to

compounds, their motivation is morphological if the meaning of the whole is

based on the direct meaning of the components, and semantic if the combination

is used figuratively: watchdog — a dog kept for watching property

(morphologically motivated); — a watchful human guardian (semantically

motivated) [5; p. 94-95].vocabulary is in a state of constant development.

Words that seem non-motivated at present may have lost their motivation [16; p.

34]. When some people recognize the motivation, whereas others do not,

motivation is said to be faded.all word-groups may be classified into motivated

and non-motivated. Non-motivated word-groups are usually described as phraseological

units or idioms.groups may be described as lexically motivated if the combined

lexical meaning of the groups is based on the meaning of their components. Thus

take lessons is motivated; take place — ‘occur’ is lexically

non-motivated.groups are said to be structurally motivated if the meaning of

the pattern is deduced from the order and arrangement of the member-words of

the group. Red flower is motivated as the meaning of the pattern quality —

substance can be deduced from the order and arrangement of the words red and

flower, whereas the seemingly identical pattern red tape (‘official

bureaucratic methods’) cannot be interpreted as quality — substance.identical

word-groups are sometimes found to be motivated or non-motivated depending on

their semantic interpretation. Thus apple sauce, e.g., is lexically and

structurally motivated when it means ‘a sauce made of apples’ but when used to

denote ‘nonsense’ it is clearly non-motivated [15; p. 90].groups like words may

be also analyzed from the point of view of their motivation. Word-groups may be

called as lexically motivated if the combined lexical meaning of the group is

deducible from the meaning of the components. All free phrases are completely

motivated.follows from the above discussion that word-groups may be also

classified into motivated and non-motivated units. Non-motivated word-groups

are habitually described as phraseological units or idioms.

. Phraseological word-groups

of English phraseology began not

long ago. English and American linguists as a rule are busy collecting

different words, word-groups and sentences which are interesting from the point

of view of their origin, style, usage or some other features. All these units

are habitually described as «idioms», but no attempt has been made to

describe these idioms as a separate class of linguistic units or a specific

class of word-groups.in terminology («set-phrases»,

«idioms» and «word-equivalents») reflects certain

differences in the main criteria used to distinguish types of phraseological

units and free word-groups. The term «set phrase» implies that the

basic criterion of differentiation is stability of the lexical components and

grammatical structure of word-groups.is a certain divergence of opinion as to

the essential features of phraseological units as distinguished from other

word-groups and the nature of phrases that can be properly termed

«phraseological units». The habitual terms «set-phrases»,

«idioms», «word-equivalents» are sometimes treated

differently by different linguists. However these terms reflect to certain

extend the main debatable points of phraseology which centre in the divergent

views concerning the nature and essential features of phraseological units as

distinguished from the so-called free word-groups.term «set

expression» implies that the basic criterion of differentiation is

stability of the lexical components and grammatical structure of

word-groups.term «word-equivalent» stresses not only semantic but

also functional inseparability of certain word-groups, their aptness to

function in speech as single words [10; p. 31].term «idioms»

generally implies that the essential feature of the linguistic units under

consideration is idiomaticity or lack of motivation. Uriel Weinreich expresses

his view that an idiom is a complex phrase, the meaning of which cannot be

derived from the meanings of its elements. He developed a more truthful

supposition, claiming that an idiom is a subset of a phraseological unit. Ray

Jackendoff and Charles Fillmore offered a fairly broad definition of the idiom,

which, in Fillmore’s words, reads as follows: «…an idiomatic expression or

construction is something a language user could fail to know while knowing

everything else in the language». Chafe also lists four features of idioms

that make them anomalies in the traditional language unit paradigm:

non-compositionality, transformational defectiveness, ungrammaticality and

frequency asymmetry.work in this field has been done by the outstanding Russian

linguist A. Shakhmatov in his work «Syntax». This work was continued

by Acad. V.V. Vinogradov. Great investigations of English phraseology were done

by Prof. A. Cunin, I. Arnold and others [1; p. 121].units are habitually

defined as non-motivated word-groups that cannot be freely made up in speech

but are reproduced as ready-made units; the other essential feature of

phraseological units is stability of the lexical components and grammatical

structure.components of free word-groups which may vary according to the needs

of communication, member-words of phraseological units are always reproduced as

single unchangeable collocations. E.g., in a red flower (a free phrase) the

adjective red may be substituted by another adjective denoting colour, and the

word-group will retain the meaning: «the flower of a certain colour»

[2; p. 54].the phraseological unit red tape (bürokratik

metodlar) no such substitution is possible, as a change of the adjective would

cause a complete change in the meaning of the group: it would then mean «tape

of a certain colour». It follows that the phraseological unit red tape is

semantically non-motivated, i.e. its meaning cannot be deduced from the meaning

of its components, and that it exists as a ready-made linguistic unit which

does not allow any change of its lexical components and its grammatical

structure [9; p. 45-46].structure of phraseological units is to a certain

degree also stable:tape — a phraseological unit;tapes — a free word-group;go to

bed — a phraseological unit;go to the bed — a free word-group.ways of forming

phraseological units are those when a unit is formed on the basis of a free

word-group

phraseological units by means of transferring the meaning of terminological

word-groups, e.g. in cosmic technique we can point out the following phrases:

«launching pad» in its terminological meaning is «стартова

площадка», in its transferred meaning — «відправний пункт»,

«to link up» — «cтикуватися, стикувати космічні човни» in

its tranformed meaning it means -«знайомитися»;) a large group of

phraseological units was formed from free word groups by transforming their

meaning, e.g. «granny farm» — «пансионат для старих людей»,

«Troyan horse» — «компьютерна програма, яка навмиснестворена для

пвиведення з ладу компьютера»;) phraseological units can be formed by

means of alliteration, e.g. «a sad sack» — «нещасний

випадок», «culture vulture» — «людина, яка цікавиться

мистецтвом», «fudge and nudge» — «ухильність».) they

can be formed by means of expressiveness, especially it is characteristic for

forming interjections, e.g. «My aunt!», «Hear, hear !» etc)

they can be formed by means of distorting a word group, e.g. «odds and

ends» was formed from «odd ends»,) they can be formed by using

archaisms, e.g. «in brown study» means «in gloomy

meditation» where both components preserve their archaic meanings,) they

can be formed by using a sentence in a different sphere of life, e.g.

«that cock won’t fight» can be used as a free word-group when it is

used in sports (cock fighting ), it becomes a phraseological unit when it is

used in everyday life, because it is used metaphorically,) they can be formed

when we use some unreal image, e.g. «to have butterflies in the

stomach» — «відчувати хвилювання», «to have green

fingers» — «досягати успіхів як садовод-любитель» etc.) they can

be formed by using expressions of writers or polititions in everyday life, e.g.

«corridors of power» (Snow), «American dream» (Alby)

«locust years» (Churchil) , «the winds of change» (Mc

Millan).into consideration mainly the degree of idiomaticity phraseological

units may be classified into three big groups. This classification was first

suggested by Acad. V.V. Vinogradov. These groups are:

phraseological fusions,

phraseological unities,

phraseological collocations, or

habitual collocations.fusions are completely non-motivated word-groups.

Themeaning of the components has no connection at least synchronically with the

meaning of the whole group. Idiomaticity is combined with complete stability of

the lexical components and the grammatical structure of the fusion [19; p.

37].unities are partially non-motivated word-groups as their meaning can

usually be understood through (deduced from) the metaphoric meaning of the

whole phraseological unit [3; p. 84].unities are usually marked by a

comparatively high degree of stability of the lexical components and

grammatical structure. Phraseological unities can have homonymous free phrases,

used in direct meanings.

§ to skate on thin

ice — to skate on thin ice (to risk);

§ to wash one’s hands

off dirt — to wash one’s hands off (to withdraw from participance);

§ to play the first

role in the theatre — to play the first role (to dominate).must be not less

than two notional wordsin metaphorical meanings.collocations are partially

motivated but they are made up of words having special lexical valency which is

marked by a certain degree of stability in such word-groups. In phraseological

collocations variability of components is strictly limited. They differ from

phraseological unities by the fact that one of the components in them is used

in its direct meaning, the other — in indirect meaning, and the meaning of the

whole group dominates over the meaning of its components. As figurativeness is

expressed only in one component of the phrase it is hardly felt [14; p. 69].

§ to pay a visit,

tribute, attention, respect;

Conclusions

the course of the present report

writing we have specified the definition of the word-group and determined its

general characteristics. Specific attention has been drawn to the

classification of word-groups. We have thoroughly analyzed semantic features of

word-groups, their motivated and non-motivated types and their specific

subtype, i.e. phraseological word-groups.completed the report writing, we have

come to the following conclusions.word-group is a combination of at least two

notional words which do not constitute the sentence but are syntactically

connected.have concluded that according to the type of syntagmatic relations,

word-groups can be coordinate, subordinate and predicative, according to the

structure they are divided into simple, expanded and extended.lexical meaning

of the word groups is the combined lexical meaning of the component words. The

meaning of the word groups is motivated by the meanings of the component

members and is supported by the structural pattern.term motivation is used to

denote the relationship existing between the phonemic or morphemic composition

and structural pattern of the word on the one hand and its meaning on the

other.have come to the conclusion, that here are three main types of

motivation: 1) phonetical; 2) morphological; 3) semantic.have concluded,

phraseological units are created from free word-groups. But in the course of

time some words — constituents of phraseological units may drop out of the

language; the situation in which the phraseological unit was formed can be

forgotten, motivation can be lost and these phrases become phraseological

fusions.

Bibliography

1. Арнольд

И.В. Аспекты семантических исследований. — М., 1980.

2. Арнольд

И.В. Стилистика современного английского языка. — М., 1973.

. Кунин

А.В. Фразеология современного английского языка. — М., 1970

. Маковский

М.М. Английская этимология. — М., 1986

. Мешков

О.Д. Словообразование современного английского языка. -М., 1976

. Мостовий

М.I. Лексикологiя

англiйськоi

мови. — Харькiв, 1993

. Никитин

М.В. Лексическое значение слова (структура и комбинаторика). — М., 1983

Смирницкий А.И. Лексикология английского языка. — М., 1956

. Никитин

М.В. О предмете и понятиях комбинаторной семантики / Проблемы лексической и

грамматической семасиологии. Владимир, 1974 год выпуска

9. Смит

Л.П. Фразеология английского языка. — М., 1959

. Старикова

Е.Н.. Раевская Н.Н., Медведева Л.М. Лингвистические чтения. Проблемы

словообразования. Лингвистика текста. — К., 1985

11. Телия

В.Н. Типы языковых значений. Связанное значение слова в языке — М., 1981

Теоретические проблемы социальной лингвистики. — М., 1981

. Харитончик

З.А. Лексикология английского языка. — Минск, 1992

. Швейцер

А.Д. Очерк современного английского языка США. — М.. 1963

. Akhmanova

O. Lexicology. Theory and Method. — M., 1972 Ginsburg R.S. A Course in Modern

English Lexicology. M., 1979.

. Arnold

I.V. The English Word. — M., 1986

. Kuznetsova

V.S. Notes on English Lexicology.- K., 1968.

. L.P.

Smith, Semantics. An introduction to the science of meaning. Oxford University

Press, 1962.

. Vinogradov

V.V. Pixon P.G. Handbook of American Idioms and Idiomatic Usage, 1973.