In English, it is often possible to understand what has an effect on only by the mutual arrangement of the members of the sentence, therefore constant word order is especially important in it. Changing the order of words in an English sentence can completely change its meaning: Jim hit Billy. Jim hit Billy.

In English, the word order in a sentence is fixed. This means that we cannot rearrange the words as we like. They must stand in their specific places. It is difficult for beginners to learn English to understand and get used to it.

What is the word order in English?

The direct word order in an English sentence is as follows: the subject is in the first place, the predicate is in the second, and the complement is in the third. In some cases, the circumstance may come first. In an English sentence, an auxiliary verb may appear in the main verb.

What is the word order in an English declarative sentence?

A characteristic and distinctive feature of declarative affirmative sentences in English is the observance of a firm (direct) word order. This means that in the first place in a sentence the subject is usually put, in the second place — the predicate, in the third place — the addition and then the circumstances.

What is the word order in an English affirmative sentence?

In an affirmative sentence, the subject is in the first place, the predicate is in the second place, and the secondary members of the sentence are in the third place.

Can I change the order of words in an English sentence?

Changing the order of words in an English sentence can completely change its meaning: … Usually the word order in an English sentence is as follows: Subject takes first place followed by Predict

In what order should you put adjectives in English?

The order of adjectives in English

- Article or other qualifier (a, the, his)

- Rating, opinion (good, bad, terrible, nice)

- Size (large, little, tiny)

- Age (new, young, old)

- Shape (square, round)

- Color (red, yellow, green)

- Origin (French, lunar, American, eastern, Greek)

What is the word order in the English interrogative sentence?

In the first place the necessary QUESTIONAL WORD is put, in the second — the FAVORABLE, in the third place — the SUBJECT, in the fourth place are the SECONDARY members of the sentence.

How to build sentences correctly?

The subject is usually placed before the predicate. The agreed definition is before the word being defined, the circumstance of the mode of action is before the predicate, and the rest of the circumstances and addition are after the predicate. This word order is called direct. In speech, the specified order of the members of the sentence is often violated.

How many words are there in English?

Let’s try to find out the number of words in English by looking in the dictionary: The second edition of the 20-volume Oxford English Dictionary contains 171 words currently in use, and 476 obsolete words. To this can be added about 47 derivative words.

How to determine what time a sentence is in English?

The tense in an English sentence is determined by the verb. Note, not by additional words, but by the predicate verb.

What is a big word order sentence?

In direct word order, the subject precedes the predicate, i.e. comes first. In the reverse order of words, the subject is placed immediately after the predicate (its conjugated part).

How to make negative sentences in English?

To make sentences negative, you must put the word «not» after the modal verb. For example, we have an affirmative sentence: He can swim. He can swim.

What sentences are there in English?

The following types of sentences are distinguished in English, as in Russian, depending on the purpose of the statement: declarative, interrogative, negative and exclamatory.

What are the tenses in English?

There are also three English tenses — present, past and future, but depending on whether the action is complete or prolonged, each of these tenses can be of four types — simple, continuous, perfect and perfect continuous.

Where are adverbs in English?

Usually adverbs in English are placed after verbs, but before adjectives, other adverbs or participles. For example: I slept well this night.

Standard Word Order

Here’s our example sentence with many components, using standard word order:

The men delivered the sandwiches to everyone at the shop before lunchtime.

We have Subject (The men) Verb (delivered) Direct Object (the sandwiches) Prepositional Phrases (to everyone at the shop) Time (before lunchtime). To rewrite the sentence, we now have a number of options.

Playing with Tenses

As a relatively simple starting point, there are a number of ways we can manipulate a tense to change a sentence. For example we could replace the verb with a different form, with the same meaning (in this case changing the Verb and Object):

The men made a delivery of sandwiches to everyone at the shop before lunchtime.

The opportunities to do this will depend on the sentence. In some cases it will not be possible, in others (such as when writing a future simple sentence) there may be many options.

If the subject is not important, or we want to make text seem more neutral or less direct, we can use the passive tense. This reverses the position of the Object and adds a to be + past participle structure:

The sandwiches were delivered to everyone at the shop before lunchtime.

In this case we are more interested in the result than who did the action.

When we have had the opportunity to introduce a different verb structure, we could also combine this with a passive tense:

A delivery of sandwiches was made to everyone at the shop before lunchtime.

Moving the Time

Time phrases, and clauses, can come at the beginning or the end of the sentence. Times at the start add emphasis, framing the sentence rather than providing a time as additional information.

Before lunchtime, the men delivered the sandwiches to everyone at the shop.

Slightly less natural, we can also insert the time after the Subject or Object, between commas. This should be done rarely, as it really adds emphasis to the time in a particular place, where it might be surprising:

The men delivered the sandwiches, before lunchtime, to everyone at the shop.

In this case you would place the time there to draw especial attention to when the delivery was made, as opposed to who it was for. Placing the time after the Subject (The men, before lunchtime, delivered…) would add even more emphasis, and sound quite unnatural – but that’s precisely the point, if you ever needed to use such a structure.

Moving the time, though I’ve separated it here, is actually a case of moving prepositional phrase. I’ve dealt with it separately to provide a clear example of switching a phrase’s location. Getting into prepositional phrases in general, though, rewriting sentences can become more complicated.

Prepositional Phrases

Prepositional phrases add additional information that can relate to the sentence in a variety of ways, allowing for lots of different rewrites. In the example sentence we have two prepositional phrases that add additional information other than time: to everyone and at the shop.

The preposition to, in this case, serves as a direction (where the delivery was directed) and a purpose (who were the sandwiches for). The prepositional phrase at the shop gives us a location which can either define the place that the sandwiches were delivered to or define the preceding object – everyone (the people at the shop).

When you break down the reasons for the prepositional phrases in this way, you can start to create opportunities to change the sentence. Firstly, you might use different phrases with similar meanings.

The men delivered the sandwiches for everyone at the shop before lunchtime.

The men delivered the sandwiches to everyone in the shop before lunchtime.

These are very basic changes that create slight differences, in this case differences that should not change the understanding of the sentence. But this could change the meaning. In the first example, for instance, it could be understood that the delivery was made on everyone’s behalf (they requested it), not necessarily for them to receive (though without further information we may assume that on their behalf means for them to receive). More alterations could make this different meaning more distinct:

The men delivered the sandwiches for the people of the shop before lunchtime.

In this example, the people are not given a location, just a defining characteristic (that they belong to the shop), giving the delivery a purpose without a specific destination.

Knowing that the sandwiches were for someone, though, we have other options than simply swapping prepositions. For in particular usually gives us a chance to use possessives, or possessive pronouns, instead of prepositional phrases:

The men delivered everyone’s sandwiches to the shop before lunchtime.

The men delivered everyone their sandwiches at the shop before lunchtime.

However, this is a technique that’s effectiveness will vary a lot depending on the verb you are using, and the relationship between the Object and Indirect Object. In this example, using an Indirect Object sounds a little strange after deliver. With a different verb it could sound more natural.

The men gave everyone their sandwiches at the shop before lunchtime.

It is more flexible, though, if the Indirect Object is a pronoun (when the object it refers to is already understood):

The men delivered them their sandwiches at the shop before lunchtime.

You may have noticed that the second prepositional phrase may be affected when we start making these changes. In the original sentence, it is quite clear that everyone is at the shop. We assume this is their location, and where they belong. When we move for everyone away from at the shop, though, the link between them blurs. The men delivered everyone their sandwiches at the shop could be taken to mean the shop was the location of the delivery, but not where everyone is based/belongs.

Sometimes, dividing phrases like this will not really cause problems (unless you are very picky). In other cases, it can cause confusion and actually change the meaning, so it is important to be aware of when you need to combine related information. Consider what happens when we use a more specific preposition:

The men delivered the sandwiches to everyone outside the shop.

The men delivered everyone their sandwiches outside the shop.

In the first example, the group everyone is defined by all the people in that location. In the second example, the group (everyone) is not specifically defined, but outside the shop is simply where they received the sandwiches.

Understanding these relationships between different sentence components is crucial to rewriting sentences. Moving the location requires the same considerations. It can be moved more freely if it is not defining another object:

At the shop, the men delivered the sandwiches to everyone before lunchtime.

Like when we move the time, this now frames the sentence. But if we want that information to define the group of people (Who is everyone? All the people at the shop), separating the phrases like this breaks that meaning – everyone is no longer defined by the location. But if we must keep that information together, it would frame the sentence in a different way:

For everyone at the shop, the men delivered the sandwiches before lunchtime.

This gives the action a grand sense of purpose. By removing all the additional information from later in the sentence, we have put more emphasis on the time – in this case it sounds like the men made the delivery at that time as a special consideration for these people.

These are just some of the ways we can start switching prepositional phrases around, in some cases adjusting meaning and in others simply adding variety. With different prepositional phrases, there will be more options to consider.

Other Ways to Rewrite Sentences

It is also necessary to also consider how using alternative words can also help rewrite sentences, using synonyms or similar words with slightly different meaning. While this is mostly a case of vocabulary, replacing words can also lead to different grammatical constructions, and in some case provide other opportunities to change word order. This was the case in replacing to everyone with everyone’s, in a simple form, but it could be more elaborate, such as when we replace verbs with more complicated ideas:

The men made a delivery of sandwiches to everyone at the shop before lunchtime.

As we added another prepositional phrase here, it opens the door to more changes:

Consisting of sandwiches, a delivery came the shop for everyone before lunchtime.

If that sounds like a stretch, it is. It might not be as clear, or comfortable to say, but if the exercise is simply rewriting, this is still acceptable English.

There are countless considerations that can be made as you look at different sentences, and these points I have given come from just one example. Thinking in these terms is merely a starting point in rewriting English sentences. These ideas can be built upon with more complex sentences, and later applied in moving whole clauses (in complex sentences, after all, a clause may represent a basic sentence component). And, naturally, all these different techniques can be combined to form something quite different with entirely the same meaning:

The men delivered the sandwiches to everyone at the shop before lunchtime.

Before lunchtime, everyone at the shop’s sandwiches were delivered by the men.

In the interests of driving these points home, and because these are lessons that can be applied in all areas of English writing, I reproduced this whole article on another website, however that is no longer functioning. If you’d still like to read it, though, let me know! The other version may also clear up any points that are unclear!

Можно ли использовать вопросительный порядок слов в утвердительных предложениях? Как построить предложение, если в нем нет подлежащего? Об этих и других нюансах читайте в нашей статье.

Прямой порядок слов в английских предложениях

Утвердительные предложения

В английском языке основной порядок слов можно описать формулой SVO: subject – verb – object (подлежащее – сказуемое – дополнение).

Mary reads many books. — Мэри читает много книг.

Подлежащее — это существительное или местоимение, которое стоит в начале предложения (кто? — Mary).

Сказуемое — это глагол, который стоит после подлежащего (что делает? — reads).

Дополнение — это существительное или местоимение, которое стоит после глагола (что? — books).

В английском отсутствуют падежи, поэтому необходимо строго соблюдать основной порядок слов, так как часто это единственное, что указывает на связь между словами.

| Подлежащее | Сказуемое | Дополнение | Перевод |

|---|---|---|---|

| My mum | loves | soap operas. | Моя мама любит мыльные оперы. |

| Sally | found | her keys. | Салли нашла свои ключи. |

| I | remember | you. | Я помню тебя. |

Глагол to be в утвердительных предложениях

Как правило, английское предложение не обходится без сказуемого, выраженного глаголом. Так как в русском можно построить предложение без глагола, мы часто забываем о нем в английском. Например:

Mary is a teacher. — Мэри — учительница. (Мэри является учительницей.)

I’m scared. — Мне страшно. (Я являюсь напуганной.)

Life is unfair. — Жизнь несправедлива. (Жизнь является несправедливой.)

My younger brother is ten years old. — Моему младшему брату десять лет. (Моему младшему брату есть десять лет.)

His friends are from Spain. — Его друзья из Испании. (Его друзья происходят из Испании.)

The vase is on the table. — Ваза на столе. (Ваза находится/стоит на столе.)

Подведем итог, глагол to be в переводе на русский может означать:

- быть/есть/являться;

- находиться / пребывать (в каком-то месте или состоянии);

- существовать;

- происходить (из какой-то местности).

Если вы не уверены, нужен ли to be в вашем предложении в настоящем времени, то переведите предложение в прошедшее время: я на работе — я была на работе. Если в прошедшем времени появляется глагол-связка, то и в настоящем он необходим.

Предложения с there is / there are

Когда мы хотим сказать, что что-то где-то есть или чего-то где-то нет, то нам нужно придерживаться конструкции there + to be в начале предложения.

There is grass in the yard, there is wood on the grass. — На дворе — трава, на траве — дрова.

Если в таких типах предложений мы не используем конструкцию there is / there are, то по-английски подобные предложения будут звучать менее естественно:

There are a lot of people in the room. — В комнате много людей. (естественно)

A lot of people are in the room. — Много людей находится в комнате. (менее естественно)

Обратите внимание, предложения с there is / there are, как правило, переводятся на русский с конца предложения.

Еще конструкция there is / there are нужна, чтобы соблюсти основной порядок слов — SVO (подлежащее – сказуемое – дополнение):

| Подлежащее | Сказуемое | Дополнение | Перевод |

|---|---|---|---|

| There | is | too much sugar in my tea. | В моем чае слишком много сахара. |

Более подробно о конструкции there is / there are можно прочитать в статье «Грамматика английского языка для начинающих, часть 3».

Местоимение it

Мы, как носители русского языка, в английских предложениях забываем не только про сказуемое, но и про подлежащее. Особенно сложно понять, как перевести на английский подобные предложения: Темнеет. Пора вставать. Приятно было пообщаться. В английском языке во всех этих предложениях должно стоять подлежащее, роль которого будет играть вводное местоимение it. Особенно важно его не забыть, если мы говорим о погоде.

It’s getting dark. — Темнеет.

It’s time to get up. — Пора вставать.

It was nice to talk to you. — Приятно было пообщаться.

Хотите научиться грамотно говорить по-английски? Тогда записывайтесь на курс практической грамматики.

Отрицательные предложения

Если предложение отрицательное, то мы ставим отрицательную частицу not после:

- вспомогательного глагола (auxiliary verb);

- модального глагола (modal verb).

| Подлежащее | Вспомогательный/Модальный глагол | Частица not | Сказуемое | Дополнение | Перевод |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sally | has | not | found | her keys. | Салли не нашла свои ключи. |

| My mum | does | not | love | soap operas. | Моя мама не любит мыльные оперы. |

| He | could | not | save | his reputation. | Он не мог спасти свою репутацию |

| I | will | not | be | yours. | Я не буду твоей. |

Если в предложении единственный глагол — to be, то ставим not после него.

| Подлежащее | Глагол to be | Частица not | Дополнение | Перевод |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peter | is | not | an engineer. | Питер не инженер. |

| I | was | not | at work yesterday. | Я не была вчера на работе. |

| Her friends | were | not | polite enough. | Ее друзья были недостаточно вежливы. |

Порядок слов в вопросах

Для начала скажем, что вопросы бывают двух основных типов:

- закрытые вопросы (вопросы с ответом «да/нет»);

- открытые вопросы (вопросы, на которые можно дать развернутый ответ).

Закрытые вопросы

Чтобы построить вопрос «да/нет», нужно поставить модальный или вспомогательный глагол в начало предложения. Получится следующая структура: вспомогательный/модальный глагол – подлежащее – сказуемое. Следующие примеры вам помогут понять, как утвердительное предложение преобразовать в вопросительное.

She goes to the gym on Mondays. — Она ходит в зал по понедельникам.

Does she go to the gym on Mondays? — Ходит ли она в зал по понедельникам?

He can speak English fluently. — Он умеет бегло говорить по-английски.

Can he speak English fluently? — Умеет ли он бегло говорить по-английски?

Simon has always loved Katy. — Саймон всегда любил Кэти.

Has Simon always loved Katy? — Всегда ли Саймон любил Кэти?

Обратите внимание! Если в предложении есть только глагол to be, то в Present Simple и Past Simple мы перенесем его в начало предложения.

She was at home all day yesterday. — Она была дома весь день.

Was she at home all day yesterday? — Она была дома весь день?

They’re tired. — Они устали.

Are they tired? — Они устали?

Открытые вопросы

В вопросах открытого типа порядок слов такой же, только в начало предложения необходимо добавить вопросительное слово. Тогда структура предложения будет следующая: вопросительное слово – вспомогательный/модальный глагол – подлежащее – сказуемое.

Перечислим вопросительные слова: what (что?, какой?), who (кто?), where (где?, куда?), why (почему?, зачем?), how (как?), when (когда?), which (который?), whose (чей?), whom (кого?, кому?).

He was at work on Monday. — В понедельник он весь день был на работе.

Where was he on Monday? — Где он был в понедельник?

She went to the cinema yesterday. — Она вчера ходила в кино.

Where did she go yesterday? — Куда она вчера ходила?

My father watches Netflix every day. — Мой отец каждый день смотрит Netflix.

How often does your father watch Netflix? — Как часто твой отец смотрит Netflix?

Вопросы к подлежащему

В английском есть такой тип вопросов, как вопросы к подлежащему. У них порядок слов такой же, как и в утвердительных предложениях, только в начале будет стоять вопросительное слово вместо подлежащего. Сравните:

Who do you love? — Кого ты любишь? (подлежащее you)

Who loves you? — Кто тебя любит? (подлежащее who)

Whose phone did she find two days ago? — Чей телефон она вчера нашла? (подлежащее she)

Whose phone is ringing? — Чей телефон звонит? (подлежащее whose phone)

What have you done? — Что ты наделал? (подлежащее you)

What happened? — Что случилось? (подлежащее what)

Обратите внимание! После вопросительных слов who и what необходимо использовать глагол в единственном числе.

Who lives in this mansion? — Кто живет в этом особняке?

What makes us human? — Что делает нас людьми?

Косвенные вопросы

Если вам нужно что-то узнать и вы хотите звучать более вежливо, то можете начать свой вопрос с таких фраз, как: Could you tell me… ? (Можете подсказать… ?), Can you please help… ? (Можете помочь… ?) Далее задавайте вопрос, но используйте прямой порядок слов.

Could you tell me where is the post office is? — Не могли бы вы мне подсказать, где находится почта?

Do you know what time does the store opens? — Вы знаете, во сколько открывается магазин?

Если в косвенный вопрос мы трансформируем вопрос типа «да/нет», то перед вопросительной частью нам понадобится частица «ли» — if или whether.

Do you like action films? — Тебе нравятся боевики?

I wonder if/whether you like action films. — Мне интересно узнать, нравятся ли тебе экшн-фильмы.

Другие члены предложения

Прилагательное в английском стоит перед существительным, а наречие обычно — в конце предложения.

Grace Kelly was a beautiful woman. — Грейс Келли была красивой женщиной.

Andy reads well. — Энди хорошо читает.

Обстоятельство, как правило, стоит в конце предложения. Оно отвечает на вопросы как?, где?, куда?, почему?, когда?

There was no rain last summer. — Прошлым летом не было дождя.

The town hall is in the city center. — Администрация находится в центре города.

Если в предложении несколько обстоятельств, то их надо ставить в следующем порядке:

| Подлежащее + сказуемое | Обстоятельство (как?) | Обстоятельство (где?) | Обстоятельство (когда?) | Перевод |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fergie didn’t perform | very well | at the concert | two years ago. | Ферги не очень хорошо выступила на концерте два года назад. |

Чтобы подчеркнуть, когда или где что-то случилось, мы можем поставить обстоятельство места или времени в начало предложения:

Last Christmas I gave you my heart. But the very next day you gave it away. This year, to save me from tears, I’ll give it to someone special. — Прошлым Рождеством я подарил тебе свое сердце. Но уже на следующий день ты отдала его обратно. В этом году, чтобы больше не горевать, я подарю его кому-нибудь другому.

Если вы хотите преодолеть языковой барьер и начать свободно общаться с иностранцами, записывайтесь на разговорный курс английского.

Надеемся, эта статья была вам полезной и вы разобрались, как строить предложения в английском языке. Предлагаем пройти небольшой тест для закрепления темы.

Тест по теме «Порядок слов в английском предложении, часть 1»

© 2023 englex.ru, копирование материалов возможно только при указании прямой активной ссылки на первоисточник.

1. What is Word Order?

Word order is important: it’s what makes your sentences make sense! So, proper word order is an essential part of writing and speaking—when we put words in the wrong order, the result is a confusing, unclear, and an incorrect sentence.

2.Examples of Word Order

Here are some examples of words put into the correct and incorrect order:

I have 2 brothers and 2 sisters at home. CORRECT

2 brothers and 2 sisters have I at home. INCORRECT

I am in middle school. CORRECT

In middle school I am. INCORRECT

How are you today? CORRECT

You are how today? INCORRECT

As you can see, it’s usually easy to see whether or not your words are in the correct order. When words are out of order, they stand out, and usually change the meaning of a sentence or make it hard to understand.

3. Types of Word Order

In English, we follow one main pattern for normal sentences and one main pattern for sentences that ask a question.

a. Standard Word Order

A sentence’s standard word order is Subject + Verb + Object (SVO). Remember, the subject is what a sentence is about; so, it comes first. For example:

The dog (subject) + eats (verb) + popcorn (object).

The subject comes first in a sentence because it makes our meaning clear when writing and speaking. Then, the verb comes after the subject, and the object comes after the verb; and that’s the most common word order. Otherwise, a sentence doesn’t make sense, like this:

Eats popcorn the dog. (verb + object + subject)

Popcorn the dog eats. (object + subject + verb)

B. Questions

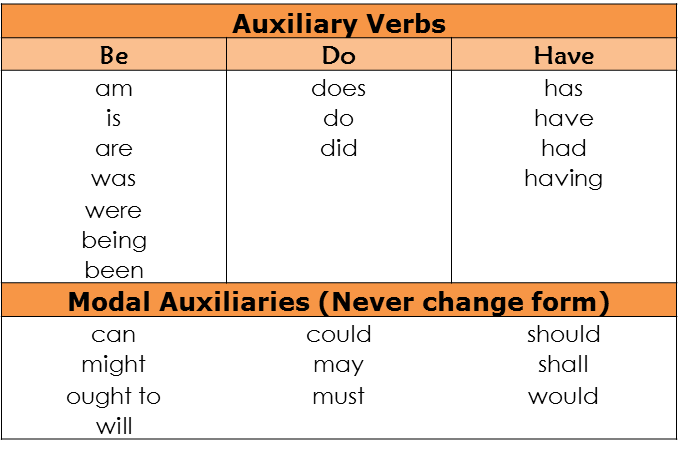

When asking a question, we follow the order auxiliary verb/modal auxiliary + subject + verb (ASV). Auxiliary verbs and modal auxiliaries share meaning or function, many which are forms of the verb “to be.” Auxiliary verbs can change form, but modal auxiliaries don’t. Here’s a chart to help you:

As said, questions follow the form ASV; or, if they have an object, ASVO. Here are some examples:

Can he cook? “Can” (auxiliary) “he” (subject) “cook” (verb)

Does your dog like popcorn? “Does” (A) “your dog” (S) “like” (V) “popcorn” (O)

Are you burning the popcorn? “Are” (A) “you” (S) “burning” (V) “popcorn” (O)

4. Parts of Word Order

While almost sentences need to follow the basic SVO word order, we add other words, like indirect objects and modifiers, to make them more detailed.

a. Indirect Objects

When we add an indirect object, a sentence will follow a slightly different order. Indirect objects always come between the verb and the object, following the pattern SVIO, like this:

I fed the dog some popcorn.

This sentence has “I” (subject) “fed” (verb) “dog” (indirect object) “popcorn” (direct object).

b. Prepositional Phrases

Prepositional phrases also have special positions in sentences. When we use the prepositions like “to” or “for,” then the indirect object becomes part of a prepositional phrase, and follows the order SVOP, like this:

I fed some popcorn to the dog.

Other prepositional phrases, determining time and location, can go at either the beginning or the end of a sentence:

He ate popcorn at the fair. -Or- At the fair he ate popcorn.

In the morning I will go home. I will go home in the morning.

c. Adverbs

Adverbs modify verbs, adjectives, and other adverbs, adding things like time, manner, degree; and often end in ly, like “slowly,” “recently,” “nearly,” and so on. As a rule, an adverb (or any modifier) should be as close as possible to the thing it is modifying. But, adverbs are special because they can usually be placed in more than one spot in the sentence and are still correct. So, there are rules about their placement, but also many exceptions.

In general, when modifying an adjective or adverb, an adverb should go before the word it modifies:

The dog was extremely hungry. CORRECT adverb modifies “hungry”

Extremely, the dog was hungry. INCORRECT misplaced adverb

The extremely dog was hungry. INCORRECT misplaced adverb

The dog was hungry extremely. INCORRECT misplaced adverb

As you can see, the word “extremely” only makes sense just before the adjective “hungry.” In this situation, the adverb can only go in one place.

When modifying a verb, an adverb should generally go right after the word it modifies, as in the first sentence below. BUT, these other uses are also correct, though they may not be the best:

The dog ran quickly to the fair. CORRECT * BEST POSITION

Quickly the dog ran to the fair. CORRECT

The dog quickly ran to the fair. CORRECT

The dog ran to the fair quickly. CORRECT

For adverbs expressing frequency (how often something happens) the adverb goes directly after the subject:

The dog always eats popcorn.

He never runs slowly.

I rarely see him.

Adverbs expressing time (when something happens) can go at either the beginning or of the end of the sentence, depending what’s important about the sentence. If the time isn’t very important, then it goes at the beginning of the sentence, but if you want to emphasize the time, then the adverb goes at the end of the sentence:

Now the dog wants popcorn. Emphasis on “the dog wants popcorn”

The dog wants popcorn now. Emphasis on “now”

5. How to Use Avoid Mistakes with Word Order

Aside from following the proper SVO pattern, it’s important to write and speak in the way that is the least confusing and the most clear. If you make mistakes with your word order, then your sentences won’t make sense. Basically, if a sentence is hard to understand, then it isn’t correct. Here are a few key things to remember:

- The subject is what a sentence is about, so it should come first.

- A modifier (like an adverb) should generally go as close as possible to the thing it is modifying.

- Indirect objects can change the word order from SVO to SVIO

- Prepositional phrases have special positions in sentences

Finally, here’s an easy tip: when writing, always reread your sentences out loud to make sure that the words are in the proper order—it is usually pretty easy to hear! If a sentence is clear, then you should only need to read it once to understand it.

Every language has its own grammar and structural rules. Likewise, English has its own set of guidelines to be followed. While some languages pay more attention to each word’s meaning, English considers the importance of how the words are positioned to properly express their meaning. The words positioning or arrangement in a sentence follows a specific pattern, also known as word order.

English word order is strict and almost fixed. It rarely changes, even if you extend your sentences or add some details. Most of the time they remain following the same order even if your sentence is positive, negative, or even if you are using a declarative or an interrogative sentence. While you can shuffle some words in your sentences according to your purposes, it is still suggested that the basic structure is followed. This makes your messages be easily understood by native speakers. It is critical to follow word order because changing it can also change the meaning of a sentence. How the words are arranged has an impact on the interpretation and correctness of your sentences. When words are put in the wrong order, they stand out. Your sentences can be confusing and unclear.

Compare the sentences below:

Apples bought Tom

Tom bought apples

Notice that the words used in the example above are the same but arranged differently.

“Apples bought Tom.”

The first sentence is confusing and seems like it doesn’t make sense. If you’ll try to understand it, its meaning seems to be the apples bought Tom.

“Tom bought apples.”

The second sentence is easier to understand and expresses an organized thought. By using the correct order, you will understand that the writer means Tom bought apples.

As a communicator, your aim is to speak and write clearly and convey meanings appropriately. To achieve this, you must familiarize yourself with different patterns or word order. This post provides a list of several patterns that we commonly use.

Pattern 1: Subject-Verb (S-V)

Sentences must have a subject and a verb. The subject almost always comes first before the verb, since the subject is what the sentence is about. Your main verb is always in the second position. Verbs used in this pattern are intransitive verbs. This pattern is sometimes called the Noun-Verb (N-V) pattern.

Example 1:

Flowers bloom

→ Flowers (S) bloom (V)

Example 2:

Sun shines

→ Sun (S) shines (V)

Example 3:

Tom shouts

→ Tom (S) shouts (V)

Example 4:

Ice melts

→ Ice (S) melts (V)

Example 5:

Water spills

→ Water (S) spills (V)

Things to remember:

A subject can be a person, place, or thing that the sentence talks about. It can be a noun or a pronoun. Moreover, it can be a single word or group of words.

A verb is an action or state of being. It is mostly a part of your predicate and tells something about the subject.

An intransitive verb is a verb that does not take an object, neither followed by a prepositional phrase nor by a complement of any kind.

Pattern 2: Subject – Verb – Direct Object (S-V-O)

In English grammar, the most commonly used structure is the subject-predicate-object pattern. Most sentences conform to this pattern. Even sentences are expanded and become complex sentences, it still follows this rule. Native English speakers rarely move away from this rule, as this shows the correct English. In this pattern, the subject comes first and is followed by the verb. The direct object goes after the verb. Transitive verbs are used in this pattern.

Example 1:

Plants need water.

→ Plants (S) need (V) water (DO)

Example 2:

The doctor prescribes medicine.

→ The doctor (S) prescribes medicine (DO)

Example 3:

Tom likes Martha.

→ Tom (S) likes (V) Martha (DO)

Example 4:

She drinks coffee.

→ She (S) drinks (V) coffee (DO)

Example 5:

I ate cheese.

→ I (S) ate (V) cheese (DO)

Things to remember:

A direct object is a person, thing, or animal that receives or is affected by the verb’s action. It could be a noun or a pronoun. It could also be a word or group of words.

Transitive verbs are verbs that have a direct object or having something or someone who receives the verb’s action.

Sentences with two objects

In some sentences, there are two objects. One is the direct object, and the other is the indirect object. Regardless of having two objects, the sentence will still commonly follow the SVO word order.

Pattern 3: Subject-Verb-Indirect Object-Direct Object (S-V-IO-DO)

The indirect object usually goes before the direct object, just like in this pattern. A transitive verb is used in this structure. This pattern is also sometimes referred to as N1 – V – N2 – N3.

Example 1:

Tom gave her flowers.

→ Tom (S) gave (V) her (IO) flowers (DO)

Example 2:

Martha sent him chocolates.

→ Martha (S) sent (V) him (IO) chocolates (DO)

Example 3:

Teachers provide students with knowledge.

→ Teachers (S) provide (V) students (IO) with knowledge (DO)

Example 4:

News programs show us current events.

→ News programs (S) shows (V) us (IO) current events (DO)

Example 5:

You deliver her parcel.

→ You (S) deliver (V) her (IO) parcel. (DO)

Things to remember:

An indirect object is a person or thing that the action is done to or for. It tells to whom or for whom the action is done.

Pattern 4: Subject – Verb – Direct Object – Indirect Object (S-V-DO-IO)

Although the indirect object (IO) mostly comes before the direct object (DO), there are instances when IO comes after the DO. When the indirect object is preceded by the word ‘to’, the IO will go after the DO.

Example 1:

S – V – IO – DO → Tom gave her flowers.

S – V – IO – DO → Tom (S) gave (V) flowers (DO) to her (IO)

Example 2:

S – V – IO – DO → Martha sent him chocolates.

S – V – IO – DO → Martha (S) sent (V) chocolates (DO) to him (IO)

Example 3:

S – V – IO – DO → Teachers provide students with knowledge.

S – V – IO – DO → Teachers (S) provide (V) knowledge (DO) to students (IO)

Example 4:

S – V – IO – DO → News programs show us current events.

S – V – IO – DO → News programs (S) shows (V) current events (DO) to us (IO)

Example 5:

S – V – IO – DO → You deliver her parcel.

S – V – IO – DO → You (S) delivers (V) parcel (DO) to her (IO)

Pattern 5: Subject – Linking Verb – Subject Complement (Adjective) (S-LV-SC A)

In some sentence structures, we use linking verbs and adjectives to provide descriptions. In this instance, you can use the S-LV-SC (A) pattern.

Example 1:

The flowers are colorful.

→ The flowers (S) are (LV) colorful (SC-A)

Example 2:

Candies are sweet.

→ Candies (S) are (LV) sweet (SC-A)

Example 3:

Farmers are industrious.

→ Farmers (S) are (LV) industrious (SC-A)

Example 4:

Internet connection is fast.

→ Internet connection (S) is (LV) fast (SC-A)

Example 5:

You are reliable.

→ You (S) are (LV) reliable(SC-A)

Things to remember:

A linking verb is a verb that connects the subject with a noun or adjective describes it.

A subject complement is a word or group of words that follows a linking verb. It completes the meaning of the subject by renaming or describing it.

Pattern 6 – Subject – Verb – Object – Objective Complement (Adjective) (S-V-O-OC A)

Other sentences include a complement to their object by using an adjective. The appropriate word order for this is S-V-O-OC (A).

Example 1:

Martha considers the report valid.

→ Martha (S) considers (V) the report (O) valid (OC-A)

Example 2:

The supervisor found the raw materials defective.

→ The supervisor (S) found (V) the raw materials (O) defective (OC-A)

Example 3:

Online learning makes education accessible.

→ Online learning (S) makes (V) education (O) accessible (OC-A)

Example 4:

The expert declares the artifacts genuine.

→ The expert (S) declares (V) the artifacts (O) genuine (OC-A)

Example 5:

Critics rated the survey invalid.

→ Critics (S) rated (V) the survey (O) invalid (OC-A)

Things to remember:

An objective complement is a word or group of words that compliment the direct object. It describes or makes a judgment about the object.

Interrogative Sentences

Asking questions is part of communicating. When asking questions, you use interrogative sentences. You will notice that even in this kind of sentence the subject-verb-object pattern will still be followed. Question words and auxiliary verbs are used in these sentences, and they are placed before the subject.

Pattern 7: Auxiliary verb + Subject + Verb (AV-S-V)

In some questions, we typically ask about the action of the person. In this case, you will use the AV-S-V pattern.

Example 1:

Can you cook?

→ Can (AV) you (S) cook(V)

Example 2:

Did she come?

→ Did (AV) she (S) come (V)

Example 3:

Is he joining?

→ Is (AV) he (S) joining (V)

Example 4:

Shall I wait?

→ Shall (AV) I (S) wait (V)

Example 5:

Will you follow?

→ Will (AV) you (S) follow (V)

Note: You can also expand and add details to our questions to make it more specific. You can add question words.

Example 1:

Without question word: Can you cook?

With question word: How can you cook?

Example 2:

Without question word: Did she come?

With question word: When did she come?

Example 3:

Without question word: Is he joining?

With question word: When is he joining?

Example 4:

Without question word: Shall I wait?

With question word: Where shall I wait?

Example 5:

Without question word: Will you follow?

With question word: Who will you follow?

Pattern 8: Auxiliary verb + Subject + Adjective (AV-S-A)

In some questions, the focus is on the description of a person, thing, events, process, etc. In this case, you will use the AV-S-A pattern.

Example 1:

Is she beautiful?

→ Is (AV) she (S) beautiful (A)

Example 2:

Is it loud?

→ Is (AV) it (S) loud (A)

Example 3:

Is the venue crowded?

→ Is (AV) the venue (S) crowded (A)

Things to remember:

An interrogative sentence is a kind of sentence that asks a question.

Question Words that you can use when writing interrogative sentences are who, what, when, why, where, and how.

Conclusion

While some ignore the importance of word order, it is beneficial to understand its effect in your sentences. Some messages with good content lose their impact just because of the wrong word order. If you can review the word order of your sentences before delivering your messages, do it. This will make your messages clear and easy to understand. Mastering the patterns above will help you to understand, speak, and write English well. Once you master it, writing in the correct pattern will be natural to you.

Learn more about grammar and useful expressions during conversations through our English courses. We have different lessons for you to enhance your English proficiency.

- Basic English

- Beginner

- English Grammar

Author

Kaycie Gayle is a freelance content writer and a digital publisher. Her writings are mostly about, travel, culture, people, food, and communication.

Related Articles

Word order refers to the conventional arrangement of words in a phrase, clause, or sentence.

Compared with many other languages, word order in English is fairly rigid. In particular, the order of subject, verb, and object is relatively inflexible.

Examples and Observations

- «I can’t see the point of Mozart. Of Mozart I can’t see the point. The point of Mozart I can’t see. See I can’t of Mozart the point. Can’t I of Mozart point the see . . . I can’t see the point of Mozart.» (Sebastian Faulks, Engleby. Doubleday, 2007)

- «[A] characteristic of modern English, as of other modern languages, is the use of word-order as a means of grammatical expression. If in an English sentence, such as ‘The wolf ate the lamb,’ we transpose the positions of the nouns, we entirely change the meaning of the sentence; the subject and object are not denoted by any terminations to the words, as they would be in Greek or Latin or in modern German, but by their position before or after the verb.»

(Logan Pearsall Smith, The English Language, 1912)

Basic Word Order in Modern English

«Assume you wanted to say that a chicken crossed the road in Modern English. And assume you are interested only in stating the facts—no questions asked, no commands, and no passive. You wouldn’t have much of a choice, would you? The most natural way of stating the message would be as in (18a), with the subject (in caps) preceding the verb (in boldface) which, in turn, precedes the object (in italics). For some speakers (18b) would be acceptable, too, but clearly more ‘marked,’ with particular emphasis on the road. Many other speakers would prefer to express such an emphasis by saying something like It’s the road that the chicken crossed, or they would use a passive The road was crossed by the chicken. Other permutations of (18a) would be entirely unacceptable, such as (18c)-(18f).

(18a) THE CHICKEN crossed the road

[Basic, ‘unmarked’ order]

(18b) the road THE CHICKEN crossed

[‘Marked’ order; the road is ‘in relief’]

(18c) THE CHICKEN the road crossed*

(18d) the road crossed THE CHICKEN*

[But note constructions like: Out of the cave came A TIGER.]

(18e) crossed the road THE CHICKEN*

(18f) crossed THE CHICKEN the road*

In this respect, Modern English differs markedly from the majority of the early Indo-European languages, as well as from Old English, especially the very archaic stage of Old English found in the famous epic Beowulf. In these languages, any of the six different orders in (18) would be acceptable . . ..»

(Hans Henrich Hock and Brian D. Joseph, Language History, Language Change, and Language Relationship: An Introduction to Historical and Comparative Linguistics. Mouton de Gruyter, 1996)

Word Order in Old English, Middle English, and Modern English

«Certainly, word order is critical in Modern English. Recall the famous example: The dog bit the man. This utterance means something totally different from The man bit the dog. In Old English, word endings conveyed which creature is doing the biting and which is being bitten, so there was built-in flexibility for word order. Inflection telling us ‘dog-subject bites man-object’ allows words to be switched around without confusion: ‘man-object bites dog-subject.’ Alerted that the man is the object of the verb, we can hold him in mind as the recipient of a bite made by a subject we know will be revealed next: ‘dog.’

«By the time English evolved into Middle English, loss of inflection meant that nouns no longer contained much grammatical information. On its own, the word man could be a subject or an object, or even an indirect object (as in ‘The dog fetched the man a bone’). To compensate for this loss of information that inflection has provided, word order became critically important. If the man appears after the verb bite, we know he’s not the one doing the biting: The dog bit the man. Indeed, having lost so much inflection, Modern English relies heavily on word order to convey grammatical information. And it doesn’t much like having its conventional word order upset.» (Leslie Dunton-Downer, The English Is Coming!: How One Language Is Sweeping the World. Simon & Schuster, 2010)

Adverbials

«One way to find out whether a sentence part is a subject or not is to make the sentence into a question. The subject will appear after the first verb:

He told me to add one tablespoon of honey per pound of fruit.

Did he tell me . . .?

We spread a thin layer of fruit on each plate.

Did we spread . . .?

The only constituent that may occur in many different places is an adverbial. Especially one-word adverbials like not, always, and often may occur almost anywhere in the sentence. In order to see if a sentence part is an adverbial or not, see if it is possible to move it in the sentence.»

(Marjolijn Verspoor and Kim Sauter, English Sentence Analysis: An Introductory Course. John Benjamins, 2000)

The Lighter Side of Word Order in Monty Python’s Flying Circus

Burrows: Good doctor morning! Nice year for the time of day!

Dr. Thripshaw: Come in.

Burrows: Can I down sit?

Dr. Thripshaw: Certainly. Well, then?

Burrows: Well, now, not going to bush the doctor about the beat too long. I’m going to come to point the straight immediately.

Dr. Thripshaw: Good, good.

Burrows: My particular prob, or buglem bear, I’ve had ages. For years, I’ve had it for donkeys.

Dr. Thripshaw: What?

Burrows: I’m up to here with it, I’m sick to death. I can’t take you any longer so I’ve come to see it.

Dr. Thripshaw: Ah, now this is your problem with words.

Burrows: This is my problem with words. Oh, that seems to have cleared it. «Oh I come from Alabama with my banjo on my knee.» Yes, that seems to be all right. Thank you very much.

Dr. Thripshaw: I see. But recently you have been having this problem with your word order.

Burrows: Well, absolutely, and what makes it worse, sometimes at the end of a sentence I’ll come out with the wrong fusebox.

Dr. Thripshaw: Fusebox?

Burrows: And the thing about saying the wrong word is a) I don’t notice it, and b) sometimes orange water given bucket of plaster.

(Michael Palin and John Cleese in episode 36 of Monty Python’s Flying Circus, 1972)

Normally, sentences in the English language take a simple form. However, there are times it would be a little complex. In these cases, the basic rules for how words appear in a sentence can help you.

Word order typically refers to the way the words in a sentence are arranged. In the English language, the order of words is important if you wish to accurately and effectively communicate your thoughts and ideas.

Although there are some exceptions to these rules, this article aims to outline some basic sentence structures that can be used as templates. Also, the article provides the rules for the ordering of adverbs and adjectives in English sentences.

Basic Sentence Structure and word order rules in English

For English sentences, the simple rule of thumb is that the subject should always come before the verb followed by the object. This rule is usually referred to as the SVO word order, and then most sentences must conform to this. However, it is essential to know that this rule only applies to sentences that have a subject, verb, and object.

For example

Subject + Verb + Object

He loves food

She killed the rat

Sentences are usually made of at least one clause. A clause is a string of words with a subject(noun) and a predicate (verb). A sentence with just one clause is referred to as a simple sentence, while those with more than one clause are referred to as compound sentences, complex sentences, or compound-complex sentences.

The following is an explanation and example of the most commonly used clause patterns in the English language.

Inversion

Inversion

The English word order is inverted in questions. The subject changes its place in a question. Also, English questions usually begin with a verb or a helping verb if the verb is complex.

For example

Verb + Subject + object

Can you finish the assignment?

Did you go to work?

Intransitive Verbs

Intransitive Verbs

Some sentences use verbs that require no object or nothing else to follow them. These verbs are generally referred to as intransitive verbs. With intransitive verbs, you can form the most basic sentences since all that is required is a subject (made of one noun) and a predicate (made of one verb).

For example

Subject + verb

John eats

Christine fights

Linking Verbs

Linking Verbs

Linking verbs are verbs that connect a subject to the quality of the subject. Sentences that use linking verbs usually contain a subject, the linking verb and a subject complement or predicate adjective in this order.

For example

Subject + verb + Subject complement/Predicate adjective

The dress was beautiful

Her voice was amazing

Transitive Verbs

Transitive Verbs

Transitive verbs are verbs that tell what the subject did to something else. Sentences that use transitive verbs usually contain a subject, the transitive verb, and a direct object, usually in this order.

For example

Subject + Verb + Direct object

The father slapped his son

The teacher questioned his students

Indirect Objects

Indirect Objects

Sentences with transitive verbs can have a mixture of direct and indirect objects. Indirect objects are usually the receiver of the action or the audience of the direct object.

For example

Subject + Verb + IndirectObject + DirectObject

He gave the man a good job.

The singer gave the crowd a spectacular concert.

The order of direct and indirect objects can also be reversed. However, for the reversal of the order, there needs to be the inclusion of the preposition “to” before the indirect object. The addition of the preposition transforms the indirect object into what is called a prepositional phrase.

For example

Subject + Verb + DirectObject + Preposition + IndirectObject

He gave a lot of money to the man

The singer gave a spectacular concert to the crowd.

Adverbials

Adverbials

Adverbs are phrases or words that modify or qualify a verb, adjective, or other adverbs. They typically provide information on the when, where, how, and why of an action. Adverbs are usually very difficult to place as they can be in different positions in a sentence. Changing the placement of an adverb in a sentence can change the meaning or emphasis of that sentence.

Therefore, adverbials should be placed as close as possible to the things they modify, generally before the verbs.

For example

He hastily went to work.

He hurriedly ate his food.

However, if the verb is transitive, then the adverb should come after the transitive verb.

For example

John sat uncomfortably in the examination exam.

She spoke quietly in the class

The adverb of place is usually placed before the adverb of time

For example

John goes to work every morning

They arrived at school very late

The adverb of time can also be placed at the beginning of a sentence

For example

On Sunday he is traveling home

Every evening James jogs around the block

When there is more than one verb in the sentence, the adverb should be placed after the first verb.

For example

Peter will never forget his first dog

She has always loved eating rice.

Adjectives

Adjectives

Adjectives commonly refer to words that are used to describe someone or something. Adjectives can appear almost anywhere in the sentence.

Adjectives can sometimes appear after the verb to be

For example

He is fat

She is big

Adjectives can also appear before a noun.

For example

A big house

A fat boy

However, some sentences can contain more than one adjective to describe something or someone. These adjectives have an order in which they can appear before a now. The order is

Opinion – size – physical quality – shape – condition – age – color – pattern – origin – material – type – purpose

If more than one adjective is expected to come before a noun in a sentence, then it should follow this order. This order feels intuitive for native English speakers. However, it can be a little difficult to unpack for non-native English speakers.

For example

The ugly old woman is back

The dirty red car parked outside your house

When more than one adjective comes after a verb, it is usually connected by and

For example

The room is dark and cold

Having said that, Susan is tall and big

Get an expert to perfect your paper

§ 1. Word order

in English is of much greater importance than in Russian. Due to the

wealth of inflexions word order in Russian is rather free as the

inflexions show the function of each Word in a sentence. As English

words have hardly any inflexions and their relation to each other is

shown by their place in the sentence and not by their form, word

order in English is fixed. We cannot change the position of different

parts of the sentence at will, especially that of the subject and the

object.

To illustrate this we Shall try to change the

order of words in the following sentence.

Mrs. Winter sent the little boy with a message to

the next village one

December day. (Hardy)

If we put the direct object in the first place and

the subject in the third, the meaning of the sentence will change

altogether because the object, being placed at the head of the

sentence, becomes the subject and the subject, being placed after the

predicate, becomes the object.

The little boy sent Mrs. Winter with a message to

the next village one

December day.

In Russian such changes of word order are in most

cases possible.

Моя сестра видела замечательный фильм

в Москве.

Замечательный фильм видела моя сестра

в Москве.

So due to the absence of case distinctions word

order is practically the only means of distinguishing between the

subject and the direct object.

The above sentence may serve as an example of

direct word order in an English declarative sentence:

(1) the subject;

(2) the predicate;

(3) objects;

(4) adverbial modifiers.

§ 2. Inverted order of words.

The order of words in which the subject is placed

after the predicate is called inverted order or inversion.

Haven’t you

any family? (Du

Maurier)

§ 3. Certain types of sentences require the inverted order of words. These are:

1. Interrogative sentences. In most of them the

inversion is partial as only part of the predicate is placed before

the subject, viz. the auxiliary or modal verb.

Where did they

find her? (Du Maurier)

Can I show

you my library? (Greene)

The whole predicate is placed before the subject

when it is expressed by the verb to be

or to

have.

Is he

at home?

Have you

many friends?

N o t e. — No inversion is used when the

interrogative word is the subject of

the sentence or an attribute to the subject: Who

is in the room? Who speaks

English here? What photos are lying on the

table?

2. Sentences introduced by there.

There is nothing

marvellous in what Jam is going to

relate. (Dickens)

Into the lane where he sat there opened

three or four garden gates.

(Dickens)

3. Compound sentences, their second part beginning

with so or

neither.

“Most of these military men are good shots,”

observed Mr. Snod-grass,

calmly; “but so are

you, ain’t

you?” (Dickens)

Their parents, Mr. and Mrs. R., escaped unhurt, so

did three

of their sons.

(Daily Worker)

4. Simple exclamatory sentences expressing wish.

Be it

so!

Gentle reader, may

you never

feel what I then felt. May your

eyes never shed

such stormy, heart-wrung tears as poured from

mine. (Ch. Bronte)

§ 4. The

inverted order of words is widely used when a word or a group of

words is put in a prominent position, i. e. when it either opens the

sentence or is withdrawn to the end of the sentence so as to produce

a greater effect. So word order often becomes a means of emphasis,

thus acquiring a stylistic function.

In this case inversion is not due to the structure

of the sentence but to the author’s wish to produce a certain

stylistic effect.

1. Inversion occurs when an adverbial modifier

opens the sentence.

Here we must distinguish the following cases:

(a) Adverbial modifiers expressed by a phrase or

phrases open the sentence, and the subject often has a lengthy

modifier.

In an open barouche, the horses of which had been

taken out, stood a

stout

old gentleman in

a blue coat and bright buttons. (Dickens)

On a chair — a shiny leather chair displaying

its horsehair through a hole in

the top left hand corner — stood

a black despatch case.

(Galsworthy)

(b) An adverbial modifier with a negative meaning

opens the sentence. Here belong such adverbial modifiers as: in

vain, never, little, etc. In this case

the auxiliary do must

be used if the predicate does not contain either an auxiliary or a

modal verb.

In vain did the

eager Luffey and the enthusiastic strugglers do

all that skill

and experience could suggest. (Dickens)

Little had I

dreamed,

when I pressed my face longingly

against Miss Minns’s

low greenish window-panes, that I would so soon

have the honour to be her

guest. (Cronin)

Never before and never since, have

I known

such peace, such a sense of

tranquil happiness. (Cronin)

(c) Adverbial modifiers expressed by such adverbs

as so, thus, now, then, etc.

placed at the head of the sentence, if the subject is expressed by a

noun.

So wore the

day away.

(London)

Thus spoke Mr.

Pickwick edging himself as Hear as

possible to the

portmanteau. (Dickens)

Now was the

moment to act.

Then across the evening stillness, broke

a blood-curdling yelp,

and

Montmorency left the boat. (Jerome)

If the subject is a pronoun inversion does not

take place.

Thus he thought

and crumpled

up and sank

down upon the

wet earth.

(London)

(d) Adverbial modifiers of manner expressed by

adverbs placed at the head of the sentence, may or may not cause

inversion. In case of inversion the

auxiliary do must

be used if the predicate does not contain either an auxiliary or a

modal verb.

Silently and patiently did

the doctor bear

all this. (Dickens)

Dimly and darkly had

the sombre shadows of

a summer’s night fallen upon

all around, when they again reached Dingley Dell.

(Dickens)

B u t: And suddenly the

moon appeared,

young and tender, floating up on

her

back from behind a tree. (Galsworthy)

Speedily that worthy

gentleman appeared.

(Dickens)

(f) An adverbial modifier preceded by so

is placed at the head of the sentence.

So beautifully did

she sing

that the audience burst into

applause.

2. Inversion occurs when the emphatic particle

only, the

adverbs hardly, scarcely (correlated

with the conjunction when), the

adverb no sooner (correlated

with the conjunction than), or

the conjunction nor open

the sentence. If there is inversion the auxiliary do

must be used if the predicate does not contain either an auxiliary or

a modal verb.

Only once did he

meet his

match in tennis.

In only one respect has

there been

a decided lack of progress in

the domain

of medicine, that is in the time it takes to

become a qualified practitioner.

(Leacock)

I do not care to speak first. Nor do

I desire

to make trouble for another.

(Cronin)

No sooner had Aunt

Julie received this

emblem of departure than a change

came over her… (Galsworthy)

Scarcely iocs one

long task completed when

a guard unlocked our door.

(London)

3. Inversion occurs when the sentence begins with

the word here which

is not an adverbial modifier of place but has some demonstrative

force.

“Here is my

card, Sir,”

replied Mr. Pickwick. (Dickens)

«Вот моя визитная карточка, сэр», —

ответил мистер Пиквик.

Here comes my

brother John.

Вот идет мой брат Джон.

If the subject is expressed by a personal pronoun

the order of words is direct.

“Here he is!”

said Sam rising with great glee. (Dickens)

«Вот он!» — радостно сказал Сэм, вставая.

“Here we are!”

exclaimed that gentleman. (Dickens)

«Вот и мы!» — воскликнул этот джентльмен.

4. Inversion occurs when postpositions denoting

direction open the sentence and the subject is expressed by a noun.

Here belong such words as in, out, down,

away, up, etc. This order of words

makes the speech especially lively.

Out went Mr.

Pickwick’s head again. (Dickens)

The wind carries their voices — away

fly the sentences like

little narrow

ribbons. (Mansfield)

Suddenly in

bounced the landlady:

“There’s a

letter for you, Miss Moss.”

(Mansfield)

But if the subject is a pronoun there is no

inversion:

Down he

fell.

Her skirt flies up above her waist; she tries to

beat it down, but it is no use —

up it

flies.

(Mansfield)

5. Inversion occurs when an object or an adverbial

modifier expressed by a word-group with not

a…, or many

a… opens the sentence.

In case of inversion the auxiliary do

must be used if the predicate does not

contain either an auxiliary or a modal verb.

Not a hansom did I

meet with in

all my drive. (London)

Not a hint, however, did

she drop

about sending me to school. (Ch.

Bronte)

Many a dun had she

talked to and

turned away from

her father’s door.

(Thackeray)

Many a time had he

watched him

digging graves in the churchyard. (Dickens)

I hated that man, many and many a time had

my fingers longed

to tear him.

(Dickens)

6. Inversion often occurs when a predicative

expressed by an adjective or by a noun modified by an adjective or by

the pronoun such opens

the sentence (in case the subject is a noun or an indefinite

pronoun).

Violent was Mr.

Weller’s indignation as he was borne

along. (Dickens)

Such is life,

and we are but as grass that is cut down, and put into the oven

and baked. (Jerome)

Sweet was that

evening.

(Ch. Bronte)

Inversion is very common in clauses of concession

where the predicative is followed by the conjunction as.

Great as

was its

influence upon individual souls, it did

not seriously affect the

main current of the life either of the church or

of the nation. (Wakeman)

However, when the subject is expressed by a

personal pronoun, the link verb follows the subject.

Bright eyes they

were.

(Dickens)

A strange place it

was.

(Dickens)

Starved and tired enough he

was.

(Ch. Bronte)

Miserable as

he was

on the steamer, a new misery came

upon him. (London)

7. Inversion is also found in conditional clauses

introduced without any conjunction when the predicate is expressed by

was, were, had, could or

should.

Even were they

absolutely hers,

it would be a passing means to

enrich herself.

(Hardy)

He soon returned with food enough for half-a-dozen

people and two bottles of

wine — enough to last them for a day or more,

should any

emergency arise.

(Hardy)

Yates would have felt better, had

the gesture of

a few kind words to Thorpe

been permitted him.

(Heym)

It must be borne in mind that emphatic order does

not necessarily mean inversion; emphasis may be also achieved by the

prominent position of some part of the sentence without inversion, i.

e. without placing the predicate before the subject.1

1 The

prominent position of each part of the sentence will be treated in

paragraphs dealing with the place of different parts of the sentence.

Here we shall only mention a peculiar way of

making almost any part of the sentence emphatic. This is achieved by

placing it is or

it was

before the part of the sentence which is to be emphasized and a

clause introduced by the relative pronoun who

or that,

by the conjunction that

or without any connective after it.

So it’s you that

have disgraced the family. (Voynich)

It is not in Mr. Rochester he

is interested. (Ch. Bronte)

Father appreciated him. It

was on father’s suggestion that he

went to law

college. (London)

Соседние файлы в предмете [НЕСОРТИРОВАННОЕ]

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #