Word-building in

English, major means of WB in English:

a) affixation;

b) conversion;

c) composition; types

of compounds.

WB

is the process of creating new words in a language with the help of

its inner sources.

Two

types of WB proper :

-

Word derivation when 1 stem undergoes different changes;

-

Word composition when 2 or more stems are put together.

The most important means of word derivation are:

a) affixation;

b) conversion;

c) composition; types of compounds.

Affixation,

conversion, composition are the most productive or major means of WB

in modern English.

Shortening

occupies the intermediate position between major & “minor” or

less productive & unproductive means of WB.

Minor

means of word-building are:

-

Back formation = reversion;

-

Blending = telescoping;

-

Reduplication = doubling the stem;

-

Sound immitation;

-

Sound interchange;

-

Shift of stress, etc.

Affixation is the most productive means of word-building in English.

Affixation is the formation of new words by adding a derivational

affix to a derivational base.

Affixation is subdivided into:

-

Suffixation

-

Prefixation.

The essential differences between suffixes &

preffixes is that preffixes as a rule only modify the lexical meaning

of a word without changing the part of speech to which the word

belongs

e.g. to tie – to untie

However, some preffixes form new words in a

different part of speech:

e.g. friend – N., to be friend-V., adj.- little., V.-

to be little.

Suffixes do not only modify the lexical meaning of a word but also

form a word belonging to a different part of speech.

Suffixes are usually classified according to the part of speech they

form:

-

Noun-forming suffixes ( to read – reader, dark – darkness);

-

Adjective-forming (power-powerful);

-

Verb-forming ( to organize, to purify);

-

Adverbal-forming (quick-quickly).

Prefixes are usually classified according to their meaning:

-

Negative prefixes (-un; -non; -in; -dis…);

-

Reversative = privative (-un; -de; -dis..);

-

Pejorative (уничижительные)

(mis-; mal- (maltreat-дурно

обращаться); pseudo-); -

Preffixes of time & order (fore-(foretell); pre-(prewar); post-;

ex-(ex-wife); -

Prefixes of repetition (re- rewrite);

-

Locative prefixes (super-; sub-subway; into-; trans –atlantic))

The 2 main criteria, according to which all the affixes are

subdivided are:

1)

origin;

2) productivity.

As to their origin (etymology) affixes are:

-

Native;

-

Borrowed.

Borrowed affixes may be classified according to the source of

borrowing (Greek, Latin, etc.) According to their productivity, i.e.

the ability to build new words at the present time, English affixes

are:

-

Productive or living affixes, used to build new words now;

-

Non-productive = unproductive affixes, not used in the word-building

now, or used very rarely.

Productivity shouldn’t be confused with frequency. What is frequent

may turn out to be non-productive (-some (adj.)-handsome is very

frequent, but not productive).

Some native prefixes still productive in English

are: — fore; -out (grow); over (estimate); -un (able); -up

(bringing); -under, -mis, etc.

Productive foreign prefixes are: -dis (like); -en (close); -re(call);

-super (natural); -pre (war); -non (drinking); -anti (noise).

Native noun-forming suffixes in modern English are: -er (writer);

-ster (youngster), -ness(brightness), etc.

Adjective-forming native suffixes (productive in English) are: -y

(rocky); -ish (Turkish), ful; -ed (cultured); -less (useless), etc.

Foreign productive noun-forming suffixes are: -ee

(employee); -tion (revolution); -ism(Gr., realism); -ist, etc.

Borrowed productive verb-forming suffixes of

Romanic origin are: -ise,ize (organize), -fy, ify (signify).

Prefixation is more typical of adjectives & verbs. Suffixation is

approximately evenly used in all parts of speech.

There are 2 types of semantic relations between affixes:

-

Homonymy;

-

Synonymy.

Homonymous prefixes are: -in: inactive, to inform.

Homonymous suffixes are: -ful1

(adjective-forming), -ful2

(noun-forming-spoonful), -ly1

(adj.-forming-friendly), -ly2

(adverb-forming-quickly).

Some affixes make a chain of synonyms: the native

suffix –er denoting an agent, is synonymous to suffix –ist

(Gr.)-socialist & to suffix –eer – also denoting an agent

(engineer) but often having a derrogatory force (`sonneteer-

стихоплёт, profiteer –

спекулянт, etc.)

Some affixes are polysemantic: the noun-forming suffix –er has

several meanings:

-

An agent or doer of the action –giver, etc.

-

An instrument –boiler, trailer

-

A profession, occupation –driver;

-

An inhabitant of some place –londoner.

b)

Conversion

is one of the most productive word-building means in English. Words,

formed by means of conversion have identical phonetic & graphic

initial forms but belong to different parts of speech (noun –

doctor; verb –to doctor). Conversion

is a process of coining (создание)

a new word in a different part of speech & with different

distribution characteristic but without adding any derivative

elements, so that the basic form of the original & the basic form

of the derived words are homonymous (identical). (Arnold)

The

main reason for the widespread conversion in English is its

analytical character, absence of scarcity of inflections. Conversion

is treated differently in linguistic literature. Some linguists

define conversion as a non-affixal way of word-building (Marchened

defines conversion as the formation of new words with the help of a

zero morpheme, hence the term zero derivation)

Some

American & English linguists define conversioon as a functional

shift from one part of speech to another, viewing conversion as a

purely syntactical process. Accoding to this point of view, a word

may function as 2 or more different parts of speech at the same time,

which is impossible. Professor Smernitsky treats conversion as a

morphological way of word-building. According to him conversion is

the formation of a new word through the changes in its paradigm.

Some

other linguists regard conversion as a morphological syntactical way

of word-building, as it involves both a change of the paradigm &

the alterration of the syntactic function of the word.

But

we shouldn’t overlook the semantic change, in the process of

conversion. All the morphological & syntactical changes, only

accompany the semantic process in conversion. Thus, conversion may be

treated as a semantico-morphologico-syntactical process.

As a word within the conversion pair is

semantically derived from the other there are certain semantic

relationswithin a conversion pair.

De-nominal words (от

глагола) make up the largest group &

display the following semantic relations with the nouns:

-

action characteristic of the thing: -a butcher; to butcher

-

instrumental use of the thing: -a whip; to wheep

-

acquisition of a thing: a coat; to coat

-

deprivation of a thing: skin – to skin.

Deverbal substantives (отглаг.сущ)they

may denote:

-

instance of the action: to move – a move;

-

agent of the action: to switch – a switch;

-

place of the action: to walk- a walk;

-

object or result of the action: to find – a find.

The English vocabulary abounds mostly in verbs,

converted from nouns( or denominal verbs) & nouns, converted from

verbs (deverbal substances): pin –to pin; honeymoon-to honeymoon.

There are also some other cases of conversion: batter-to batter, up –

to up, etc.

c)

Composition is one of the most productive word-building

means in modern English. Composition is the production of a new word

by means of uniting 2 or more stems which occur in the language as

free forms (bluebells, ice-cream).

According

to the type of composition & the linking element, there are

following types of compounds:

-

neutral compounds; (1)

-

morphological compounds; (2)

-

syntactical compounds. (3)

(1)

Compounds built by means of stem junction (juxt – opposition)

without any morpheme as a link, are called neutral compounds. The

subtypes of neutral compounds according to the structure of immediate

constituents:

a)

simple neutral compounds (neutral compounds proper) consisting of 2

elements (2 simple stems): sky –blue;film-star.

b) derived compounds (derivational compounds) –

include at least one derived stem: looking-glass, music-lover,

film-goer, mill-owner derived compounds or derivational should be

distinguished from compound derivatives, formed by means of a suffix,

which reffers to the combination of stems as a whole. Compound

derivatives (сложно-произв.слова)

are the result of 2 acts of word-building composition &

derivation. ( golden-haired, broad-shouldered, honey-mooner,

first-nighter).

c)

contracted compounds which have a shortened stem or a simple stem in

their structure, as “V-day” (victory), G-man (goverment), H-bag

(hand-bag).

d)

compounds, in which at least 1 stem is compound (waterpaper(comp)

–basket(simple))

(2)

Compounds with a specific morpheme as a link (comp-s with a linking

element = morphological compounds). E.g. Anglo-Saxon, Franko-German,

speedometer, statesman, tradespeople, handicraft, handiwork.

(3)

Compounds formed from segments of speech by way of isolating speech

sintagmas are sometimes called syntactic compounds, or compounds with

the linking element(s) represented as a rule by the stems of

form-words (brother-in-law, forget-me-not, good-in-nothing).

II.

Compounds may be classified according to a part of speech they belong

& within each part of speech according to their structural

pattern (structural types of compound-nouns):

-

compounds nouns formed of an adjectival stem + a noun stem A+N.

e.g.blackberry, gold fish

-

compound nouns formed of a noun-stem +a noun stem N+N

e.g. waterfall, backbone, homestead, calhurd

III.

Semantically compounds may be: idiomatic (non-motivated),

non-idiomatic

(motivated).

The compounds whose meanings can be derived from the meanings of

their component stems, are called non-idiomatic, e.g. classroom,

handcuff, handbag, smoking-car.

The

compounds whose meanings cannot be derived from the meanings of their

component stems are called idiomatic, e.g. lady-bird, man of war,

mother-of-pearls.

The

critiria applied for distinguishing compounds from word combinations

are:

-

graphic;

-

phonetic;

-

grammatical (morphological, syntactic);

-

semantic.

The graphic criteria can be relied on when

compounds are spelled either sollidly, or with or with a hyphen, but

it fails when the compound is spelled as 2 separate words,

e.g.

blood(-)vessel

(крово-сосудистый)

The phonetic criterium is applied to comp-s which

have either a high stress on the first component as in “hothead”

(буйная голова),

or a double stress “ `washing-ma`chine”, but it’s useless when

a compound has a level stress on both components, as in “

`arm-chair, `ice-cream” etc.

If we apply morphological & syntactical

criterium, we’ll see that compounds consisting of stems, possess

their structural integrity. The components of a compound are

grammatically invariable. No word can be inserted between the

components, while the components of a word-group, being independant

words, have the opposite features (tall-boy(высокий

комод), tall boy (taller&

cleverer,tallest)).

One of the most reliable criteria is the semantic

one. Compounds generally possess the higher degree of semantic

cohesion (слияние) of its elements

than word-groups. Compounds usually convey (передавать)

1 concep. (compare: a tall boy – 2 concepts, & a tallboy – 1

concept). In most cases only a combination of different criteria can

serve to distinguish a compound word from a word combination.

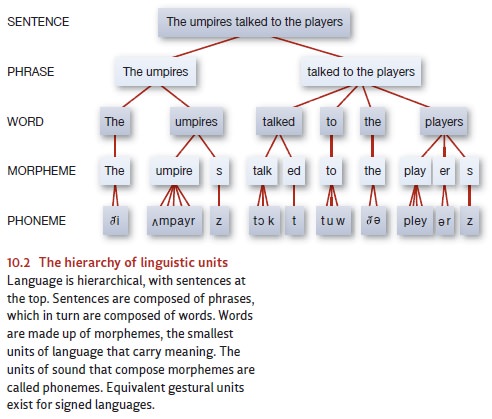

The Sound Units • Morphemes and Words • Phrases and Sentences

THE BUILDING

BLOCKS OF LANGUAGE

Languages consist of a hierarchy

of unit types, which combine and recombine to form higher and higher level

categories so that, with a relatively small number of basic units, each person

can express and understand innumerable new thoughts. At the bottom are the

units of sound such as c, t, and a, which combine into such words as cat, act, and tact. These words combine in turn into

such phrases as a fat cat, and the

phrases thencombine into such sentences as A

fat cat acts with tact and That’s the

act of a tacky cat. (Figure 10.2 illustrates this hierarchy of linguistic

categories.) We now take up each of these levels of organization in turn.

• The Sound Units

• Morphemes and Words

• Phrases and Sentences

Study Material, Lecturing Notes, Assignment, Reference, Wiki description explanation, brief detail

Psychology: Language : Building Blocks of Language |

1. Introduction

What does ‘learning a meaning’ include? Acquiring meaning for a word depends on initial and subsequent exposures in context, with joint attention (often with point or gaze at the intended target referent), to establish an initial mapping of meaning-to-word form. Learning more about conventional meanings in a language community depends on attaining further knowledge about the relevant conceptual domain and about the meanings of the words available for talk about that domain.

In this paper, I take up what ‘acquiring a word meaning’ involves, for both children and adults. I will argue that, like children, adult speakers need not have acquired fully specified, conventional, meanings for all the terms they hear from others in their language community. Nor do two speakers need identical mental representations of conventional meanings in memory in order to understand one another and so communicate effectively. Rather, they need to know just enough about the relevant word meaning, together with an assessment of common ground, to understand the speaker’s intended meaning in context. For production, though, they may need more actual knowledge about a domain, and hence about the appropriate usage of the relevant terms, when talking about that domain with others.

What counts as enough? Addressees need to be able to identify the relevant conceptual domain, and the general type of object, action, or relation at issue, so that they can make appropriate pragmatic inferences about the speaker’s intention, given some common ground, the physical context, and the current conversation. They can then make use of any inferences available on each occasion from what is co-present in the physical and conversational context. For example, adults may be familiar with certain words for trees such as beech, apple, or elm, yet be unable to identify instances of these tree types from such properties as general outline shape, leaf-type, or bark. Their meanings for such tree terms are therefore only partial meanings. The same goes for words in many everyday domains (terms for birds, insects, plants, and flowers, for instance), in addition to myriad domains in such fields as medicine, architecture, farming, sailing, music, geology, astronomy, and biology, to list just a few. Much of the time, knowing just a partial meaning is enough: knowing that the speaker is talking about a tree, say, or a bird, may be all that is needed in context. This view of how adults, like children, can manage with only partial knowledge of a word’s meaning I will call the gradualist view of word meaning acquisition, representation, and use.

2. What counts as enough when it comes to representing word meaning?

When interpreting what a speaker has said, addressees need to be able to (a) identify the domain being talked about, (b) identify the type of object, action, or relation under discussion, and (c) make appropriate inferences about what the speaker most likely intends on that occasion. Consider the following example:

From Ann’s utterance in (1), Ben can infer that a sheepshank is most likely some kind of knot. But he can infer nothing more about the term sheepshank than that, and might never learn any more about the full meaning of this term. In order to actually shorten the rope on that occasion though, Ben will need to ask what a sheepshank is and that question could then elicit a demonstration of the relevant knot from Ann, thus allowing Ben to update his semantic representation for the term sheepshank that Ann had used as well as actually tie the relevant knot.

In this paper, I take a processing approach to language use in interaction. This contrasts with the view of language as a product, the approach generally found in linguistics, where the focus is on language structure rather than on language use (Clark & Clark Reference Clark and Clark1977). I first consider some of what we know about children’s ability to make inferences and reason about word meanings and then consider what we can learn from the nature of children’s initial inferences about the meanings of unfamiliar words, displayed in their earliest word uses, later followed by gradual additions to their initial, partial, meanings as they are exposed to further uses of each word in a variety of contexts by more expert speakers.

Even very young children readily make inferences about what other speakers intend. In (2), for example, the child immediately infers who is going to have a swim:

In (3), from my own diary observations, the child readily identifies what his father wants him to do, inferred from his father’s tapping on the edge of his cereal bowl, given their common ground with respect to similar occasions in the past:

Young children’s reliance on such pragmatic inferences in context is widespread (see e.g. Papafragou & Tantalou Reference Papafragou and Tantalou2004; Stiller, Goodman & Frank Reference Stiller, Goodman and Frank2015; Papafragou, Friedberg & Cohen Reference Papafragou, Friedberg and Cohen2018; Kampa & Papafragou Reference Kampa and Papafragou2020), and this ability plays an essential role in children’s inferences about possible word meanings as they encounter new words.

After reviewing various aspects of children’s acquisition of word meanings, I will turn to adult usage and argue that adults also rely on partial meanings, meanings that may remain incomplete for years, in both comprehension and production. Just as in the case of children, the full, or fuller, acquisition of conventional meanings by adults depends on their acquisition of more detailed knowledge about the relevant conceptual domain, including added words, and, with that, becoming able to adjust, and add to, any partial meanings already in place. For communicating with others, though, for both children and adults, what matters is knowing enough in context to grasp what the speaker intends to convey so they can respond to that speaker in the next turn. In short, acquiring word meanings is a life-long activity, and we can gain insights into adult reliance on partial meanings by starting with how children assign initial, partial, meanings to words, and then gradually add to their early representations.

3. Inferences and fast mapping

Children rely heavily on adult gaze and gesture when they encounter new words. By coordinating gaze and gesture with use of a new word, adults present young children with a coherent event in joint attention. Adult gesture–speech complexes license the mapping of word-to-referent on such occasions (see e.g. O’Neill Reference O’Neill1996; Gelman, Coley, et al. Reference Gelman, Croft, Fu, Clausner and Gottfried1998; Rader & Zukow-Goldring Reference Rader and Zukow-Goldring2010, Reference Rader and Zukow-Goldring2012; Clark & Estigarribia Reference Clark and Estigarribia2011). Children’s ability to rapidly assign some initial meaning to an unfamiliar word in context has been termed ‘fast mapping’. In a first study, Carey & Bartlett (Reference Carey and Bartlett1978) looked at how 4- and 5-year-olds responded to an unfamiliar word, chromium (intended here to refer to a dark olive-green colour), presented as in (4):

From this introduction, children could (i) identify the new word, chromium, (ii) link it to the domain of trays, and (iii) infer that it designated a property, namely a colour, one that contrasts with the colour red. Four and five-year-old children did this quite reliably. This early study of fast mapping was followed up by Dockrell (Reference Dockrell1981). In one study, she showed somewhat younger children, aged 3 and 4, a small pile of toy animals that needed to be put away, and then asked for each animal to be handed to her in turn:

All the children consistently assigned the one unfamiliar word, gombe, to the one unfamiliar toy animal on the table (an ant-eater). In further studies of fast mapping, Dockrell also showed that children aged 3 and 4 consistently gave priority to shape over texture in assigning an initial meaning to a new word (Dockrell & Campbell Reference Dockrell, Campbell, Kuczaj and Barrett1986). Indeed shape is a good guide to category membership and is widely used by young children (see e.g. Clark Reference Clark and Moore1973a; Baldwin Reference Baldwin1989; Gelman, Croft, et al. Reference Gelman, Coley, Rosengren, Hartman and Pappas1998; Gershkoff-Stowe & Smith Reference Gershkoff-Stowe and Smith2004).

Fast mapping captures some of the preliminary inferences children make about possible meanings for new words. Children’s inferences here depend on the speaker’s uses of the new words in particular physical and conversational contexts. Physical and conversational co-presence depend in turn on prior joint attention and some degree of joint engagement in a coordinated activity for the adult speaker and the child. Fast mapping can be further characterized in terms of several general strategies for attaching an initial meaning to an unfamiliar word form:

-

• For unfamiliar objects, attend first to shape

-

• For unfamiliar events or actions, attend first to changes-in-state (causation), to changes-in-location (motion, path), or changes in manner-of-motion

Fast mapping has been explored in a variety of word-learning tasks that present children with nonsense words, hence word forms that are entirely unfamiliar, in forced choice tasks. While young children often make appropriate choices upon immediate testing, they reveal poor retention even five minutes later, and may forget novel nonsense words within 24 hours (Horst & Samuelson Reference Horst and Samuelson2008). They may also take several sessions to learn a meaning-to-word form mapping, possibly because the new words are not always presented in an interactive context, but via pictures or on a video screen instead (e.g. Bion, Borovsky & Fernald Reference Bion, Borovsky and Fernald2013).

Notice also that the fast mapping of nonsense word meanings is not supported by any other speakers in any other contexts. Take the case of Dockrell’s nonsense word gombe: Children never encounter this word again, either in other contexts or from other speakers. They never hear it again being used to refer to instances of ant-eaters. With the conventional words of a language though, children hear further uses over time from other speakers in a variety of contexts, with the words typically applied to a variety of referents of the appropriate (sub)type within the relevant domain. The range of referents in actual everyday exchanges is important, given that experimental studies of fast mapping have depended on very few, highly similar, exemplars as referents rather than on the range of diverse instances typically presented in studies with adults (see Murphy Reference Murphy2001). For children, I would argue, exposure to adult usage over time, and over a range of possible referents, is one factor that allows them to gradually establish more of the conventional meaning for each word to which they have been introduced.

In summary, when assigning some initial meaning to a new word, children need exposure to a range of recurring coherent referents in joint attention; they need to hear the same terms repeated on those occasions, and the number of exposures they need in order to assign some meaning to a new term may vary with how many words they already know for other entities in the relevant domain. But to get beyond initial mappings and acquire more of the meanings in question, children also have to learn about other entities in each domain along with the words used to refer to them. The same holds for the meanings of terms for actions and relations.

4. Joint attention

Joint attention is achieved when each participant (here, adult and child) is attending to the same object or event and is aware that the other person is attending to the same event (Moore & Dunham Reference Moore and Dunham1995). That is, they are mutually attending to the relevant object or action. With young children, joint attention is commonly established in one of two ways:

-

(i) Following in: the adult attends to whatever the child is already attending to, and makes that clear by talking about that object or event.

-

(ii) Getting and maintaining attention: the adult uses gestures and words to attract and then hold the child’s attention on some object or event.

In making use of physical co-presence, adults use gestures (e.g. pointing at the intended referent or holding out and displaying the referent) and gaze (looking at the current referent) as they utter a new word in referring to some entity, action, or relation in context. Adult use of gesture-and-word combinations presents 1-year-olds with a specific object or a coherent event to attend to. Gesture-speech complexes thereby serve to establish joint attention and so help young children in their initial mappings of words-to-referents, whether these are objects (Gelman, Coley, et al. Reference Gelman, Croft, Fu, Clausner and Gottfried1998; Estigarribia & Clark Reference Estigarribia and Clark2007; Clark & Estigarribia Reference Clark and Estigarribia2011; Zammit & Schafer Reference Zammit and Schafer2011) or actions (Goodrich & Hudson Kam Reference Goodrich and Kam2009; Childers et al. Reference Childers, Parrish, Olson, Burch, Fung and McIntyre2016, Reference Childers, Paik, Flores, Lai and Dolan2017). Establishing joint attention is a common pre-condition on adult offers of new words to young children, with their addition of information about the current referent (Estigarribia & Clark Reference Estigarribia and Clark2007; Rader & Zukow-Goldring Reference Rader and Zukow-Goldring2010, Reference Rader and Zukow-Goldring2012; Clark & Estigarribia Reference Clark and Estigarribia2011; Kelly Reference Kelly, Arnon, Casillas, Kurumada and Estigarribia2014.). Joint attention is also a general pre-condition in adult conversational exchanges.

5. New words and added information

In making preliminary inferences about the meaning of new words, both children and adults depend on the context of use in terms of (a) physical co-presence and (b) conversational co-presence. In this, they also attend to the fact that any new, unfamiliar, word contrasts in meaning with words they already know (Clark Reference Clark and MacWhinney1987, Reference Clark1990). That is, even very young children treat new words as having meanings that contrast with those of familiar words.

Adults often accompany a new-word offer to children with added information about the meaning as part of the conversational interaction. They link a new word in some way to other words the child already knows, and they supply added information about the current referent (a step notably absent from experimental studies of word acquisition). This added information commonly consists of information about inclusion or class membership, as well as further information about parts and properties, characteristic noises, ways of moving, functions, ontogeny, habitat, and history, along with terms for other entities in the same domain (see Callanan Reference Callanan1990; Clark & Wong Reference Clark and Andrew2002; Clark, Reference Clark2007, Reference Clark2010; Clark & Estigarribia Reference Clark and Estigarribia2011). Such information provides quite extensive material on which children can base further inferences about the possible meaning of a new word.

Consider this conversational exchange where the parent introduced the new term, owl (Clark Reference Clark, Beaver, Casillas Martínez, Clark and Kaufmann2002):

Each piece of information offered here allows the child to set up contrasts between the new word and words already known on the basis of:

-

• A difference in (sub)category

-

• Differences in parts, properties, and relations

-

• Differences in kinds of motion, characteristic sounds, and functions

The child’s usage at the time of this offer of owl consisted of duck, a subtype of bird in the child’s repertoire, that was used to designate any bird in the water and/or any bird that made a quacking noise. The new word owl contrasts with duck in that owls make a different noise, ‘hoo’, but both owl and duck are identified by the mother as birds. Notice that even with only such sparse meanings in place, child uses of the terms duck and owl may overlap with some adult usage of the terms, despite the child’s primitive taxonomy of birds.

6. Child usage is limited by vocabulary size

Children’s production of any terms for making reference is limited by their small vocabulary size in their first few years. At age 2, for instance, they are able to produce between 100 and 600 words (Fenson et al. Reference Fenson, Dale, Reznick, Bates, Thal and Pethick1994). This leads them to overextend a number of terms for objects (Clark Reference Clark and Moore1973a; Rescorla Reference Rescorla1980) and for actions (Bowerman Reference Bowerman, Waterson and Snow1978; Griffiths & Atkinson Reference Griffiths and Atkinson1978). Children also add to their options by relying on general-purpose deictics like this or there, and the verb do (Clark Reference Clark1978). They may produce a few property terms as well, but, for example, they mis-assign colour terms for some time before they fix their reference in the colour space (e.g. Soja Reference Soja1994; Clark Reference Clark2006; Kowalski & Zimiles Reference Kowalski and Zimiles2006). In talk about other properties, they may at first assign only a positive meaning to a term like less, initially treating it as ‘more’, as well as producing only the positive terms from an adjective pair like tall and short (Donaldson & Balfour Reference Donaldson and Balfour1968; Donaldson & Wales Reference Donaldson, Wales and Hayes1970). They only gradually add terms as they build up semantic fields (terms for animals, vehicles, meal-related items, toys, furniture, and particular activities), learn more about each domain, and hear more words for elements in each domain (see Clark Reference Clark, Miller and Eimas1995, Reference Clark, Syrett and Arunachalam2018; Hills Reference Hills2013). They also begin to accumulate terms for motion and placement in space, transfer of possession, and kin relations (Clark Reference Clark1973b; Haviland & Clark Reference Haviland and Clark1974; Gentner Reference Gentner, Norman and Rumelhart1975; Choi & Bowerman Reference Choi and Bowerman1991; Casasola Reference Casasola2008; Papafragou & Selimis Reference Papafragou and Selimis2010; Bowerman Reference Bowerman2018; Clark Reference Clark, Syrett and Arunachalam2018).

Children also coin terms to fill gaps in their vocabulary from as young as age 2 onwards, producing compound nouns like fix-man (= mechanic) or plate-egg (= fried egg) to label subcategories of man or egg, for example, and they talk about actions by linking them to specific objects or instruments as in to oar (= row), to scale (= weigh), or to piano (= play the piano) (Clark Reference Clark and Deutsch1981, Reference Clark1993; Clark, Gelman & Lane Reference Clark, Gelman and Lane1985; Gelman, Wilcox & Clark Reference Gelman, Wilcox and Clark1989). These are all ways of supplementing small vocabularies during the early years of acquisition.

6.1 Overextensions

Diary studies of children’s early word production reveal that one-year-olds commonly overextend or stretch their words in production. Their overextensions provide evidence that children have only partial meanings for many early words, as shown in Table 1. For example, the meaning assigned initially to a word like mum ‘horse’ appears to allow for reference to any ‘4-legged, mammal-shaped entity’, while baw ‘ball’ is used to refer to anything round and relatively small, ticktock ‘watch’ to anything with a round dial, and tee to anything stick-like. The vast majority of such overextensions are based on shape, but on occasion may be based on some aspect of motion, sound, or texture instead (E. Clark Reference Clark and Moore1973a; Baldwin Reference Baldwin1989; Gershkoff-Stowe & Smith Reference Gershkoff-Stowe and Smith2004). Extensions like these account for the wide range of uses to which very young children put early words in production.

Table 1 Examples of some typical overextensions (1;6–2;6) based on Clark (Reference Clark and Moore1973a)

Such overextensions, nearly all produced before age 2;0 to 2;6, result from children’s attempts at communication. This leads them to produce dog, for instance, not only to refer to dogs, but also to cats, squirrels, lambs, and many other small mammal-shaped creatures, until they learn to produce the relevant terms for those animals as well, namely words like cat, squirrel, or lamb.

But when children at this stage are tested on their comprehension of a term that they have overextended, such as dog, they appear to treat it in comprehension as if it refers only to dogs (Thomson & Chapman Reference Thomson and Chapman1977; Gelman, Croft, et al. Reference Gelman, Coley, Rosengren, Hartman and Pappas1998). In short, their representations in memory for comprehension appear to overlap more directly with the adult meaning, hence their identification of the appropriate referent (here a dog), as shown in Table 2 (based on Thomson & Chapman Reference Thomson and Chapman1977).

Table 2 Early overextensions in production versus comprehension

In general, comprehension is ahead of production from the start, so one also needs to look at how much children at this stage understand about the meanings of the conventional words for the entities to which a term like dog has been overextended, namely their comprehension of such terms as cat, squirrel, and lamb, as well as how specific their partial meaning of a term like dog actually is. Does it refer just to the household pet? If so, how soon do they generalize to other types of dog as well? And how soon after children learn to produce cat, for example, do they stop overextending dog to refer to cats (Barrett Reference Barrett1978)? One follow-up here would be to look at how, and how soon, children understand words for the categories to which they have been overextending dog – words like cat, squirrel, lamb – in order to track when these words become represented in memory for comprehension. Bergelson & Aslin (Reference Bergelson and Aslin2017) looked at how specific children’s comprehension of some early words seems to be, as measured by one-year-olds’ gaze at a picture of a foot or at a sock (versus a picture of an apple) on hearing the word foot. Children looked more at the actual referent (picture of the foot) and less and less at the related object (the sock) as they got older, from 12 months to 20 months. This suggests that their meaning for the term foot becomes more specific during the second year as they receive increased exposure to adult uses of the word and its possible referents.

In production children adjust their own pronunciations over time to match words they have represented in memory for comprehension, by monitoring what they themselves produce (Clark Reference Clark2016, Reference Clark2020). But early on, they have had comparatively little exposure to the full range of uses for any particular word, and so may display some under-extension in comprehension too, even for such common terms as dog or cat, fork or cup. Consider dog used to refer to an Irish wolfhound and to a Chihuahua, fork for forks with only two tines versus four or five times, or cup for sippy cups versus beer steins. Notice also that the representation of words with such meanings in memory requires both knowledge of when one can use each term to refer to a category instance, and also, eventually, of how different word meanings are related to each other within a domain: consider terms for different animals, for various drinking vessels, for all sorts of vehicles, and so on. All this depends on what children know about a particular domain. Conceptual knowledge in each domain provides a foundation for building up the meanings of words and for finding out how they are related to each other, while the words themselves help make particular aspects of the conceptual domain more memorable (Gentner et al. Reference Gentner, Özyürek, Özge and Goldin-Meadow2013).

Children stretch the few verbs they know early on in a similar way, and may produce hit, for example, for acts of hitting, touching, tapping, and smoothing with the hand; the verb open for gaining access across a variety of objects and contexts including jam jars, boxes, cupboards, and windows, as well as doors (see e.g. Bowerman Reference Bowerman, Waterson and Snow1978; Gentner Reference Gentner1978; Griffiths & Atkinson Reference Griffiths and Atkinson1978), and the verb cut for cutting with a knife, as well as shaving, peeling, chopping, and mowing, in what some researchers have called semantic approximations (Duvignau et al. Reference Duvignau, Fossard, Gaume, Pimenta and Elie2007; Pérez-Hernández & Duvignau Reference Pérez-Hernández and Duvignau2016, Reference Pérez-Hernández and Duvignau2020). Again, such overextensions in production are gradually restricted as children acquire the relevant verbs for different parts of an overextended domain. In each case, children’s early uses in production display partial meanings.

In short, children’s meanings for early words are generally incomplete both in early comprehension – from lack of exposure to uses for the range of possible referents in a category – and in production – due to the small size of their vocabulary, hence the absence of appropriate terms for many of the referents that they wish to talk about. This leads them to stretch available words with as yet only partial meanings to cover nearby or similar referents. Early on, they therefore commonly overextend both nouns and verbs in production.

6.2 General-purpose terms

In another way to supplement a small vocabulary, children often rely on deictic terms like there, along with pointing (Clark & Kelly Reference Clark, Kelly, Morgenstern and Goldin-Meadow2021) for a range of different referents for which they lack terms, and on the verb do for a range of different actions (Clark Reference Clark1978), again where they typically lack any more precise terms, as shown in (7):

Reliance on general-purpose terms offers children another way to extend their limited vocabulary in production. Similarly, in talk about spatial relations, 1- and 2-year-olds acquiring English often rely on just one preposition – only in, only on, or just a syllabic [n]-sound indeterminate between the two – for talking about the location of an object. When asked to place objects in a comprehension task, though, 1- and 2-year-olds rely instead on inferences in context that depend on physical properties of the reference point or landmark as well as of the object being placed. They always put smaller objects inside containers, and when there’s no container, they put them on a supporting surface (Clark Reference Clark1973b, Reference Clark1980). Only once they start to contrast the words in and on (compare ‘in the box’ versus ‘on the box’), though, do they assign the relevant meaning to the spatial preposition the adult has produced, rather than rely on their earlier purely concept-based strategies to guide their placements. Their early reliance on conceptual strategies and limited production reveals the incomplete nature of the meanings for their first spatial terms.

6.3 Relational terms

Children give evidence of only having partial meanings in other domains too. With dimensional adjectives, for example, they rely at first on the adjective big for extension and little for relative lack of extension, regardless of the actual dimension involved – size, height, length, width, or depth. After such early, over-general, uses of big and little (or small), they start to use high, tall, and long, and then, at around age 4 or 5, a few positive-negative pairs like high-low and long-short as well. Only later still do they master terms for such dimensions as width with wide-narrow and depth with deep-shallow (Donaldson & Wales Reference Donaldson, Wales and Hayes1970; Clark Reference Clark1972; Ravn & Gelman Reference Ravn and Gelman1984). And they commonly supply only partial meanings for kinship terms, in the form of non-relational definitions, for instance, as late as age 6 and even older (Piaget Reference Piaget1928; Haviland & Clark Reference Haviland and Clark1974), as shown in (8) and (9):

Children rely on partial meanings before acquiring fuller, near-adult meanings in other domains too, for example, for transfer verbs like give, take, buy, and sell. Between the ages of 3;6 and 8;0 or so, children go through some five stages in their comprehension of these verbs in act-out tasks as they master various aspects of their meanings and how they contrast with each other (Gentner Reference Gentner, Norman and Rumelhart1975):

6.4 Word coinages

Finally, another option for extending one’s vocabulary is to construct innovative terms in production, coinages devised to fill gaps in one’s current vocabulary. But when consistently presented with the conventional adult forms for particular meanings, children eventually give up coinages they have used for those meanings. For example, they replace the innovative verb oar with conventional row for talking about the relevant action, and they replace innovative scale with conventional weigh, when these verbs are offered, typically in the next turn, by more expert speakers (see Clark Reference Clark and Deutsch1981, Reference Clark1993; Chouinard & Clark Reference Chouinard and Clark2003; Clark Reference Clark2020).

Children often coin novel compound nouns for subcategories. When a 2-year-old who knows the word dog is told that a particular dog is a Dalmatian, that child will very likely immediately call it a DALMATIAN-dog (with compound stress), making explicit the relation between Dalmatian, the modifier, and dog, the head noun (Clark et al. Reference Clark, Gelman and Lane1985). English contains many conventional compounds that refer to subtypes (e.g., APPLE-tree, PALM-tree, OAK-tree), and children rely on this option from age 2 or so on in innovations like HOUSE-smoke (smoke from a chimney) versus CAR-smoke (exhaust), PLATE-egg (fried) versus CUP-egg (boiled), or FIRE-dog (a dog found at the site of a fire in the neighbourhood) (Clark Reference Clark1993).

Besides their early reliance on compounding, children also make some use of productive derivational forms to coin new agent nouns. For example, when 5- to 7-year-olds were asked by Berko (Reference Berko1958) what one could call someone who zibs, of the 65% of children who responded, 11% produced zibber (note that all adults produced this), and otherwise gave compounds like zibbing-man or zib-man. Clark & Hecht (Reference Clark and Hecht1982) followed up these observations with a detailed study of how much children aged 3 to 6 could understand of novel agent and instrument nouns compared to what they could produce. In comprehension, all the children could identify the base verb and the suffix —er in novel agent and instrument nouns. But in production, the youngest children made only inconsistent use of —er and instead relied on simple compounds for agents and real words (overextended) for instruments. Slightly older children, from age 4 on, made use of —er for agents in production but not for instruments (there they relied on compounds), and the oldest children, at age 6, produced -er consistently for both agents and instruments (Clark & Hecht Reference Clark and Hecht1982). Studies of derivation and compounding in other languages reveal similar patterns in the acquisition of these kinds of options (see Clark Reference Clark1993).

Reliance on word-formation, in particular on the productive options in a language, is found very generally in children as well as in adults. But adults produce innovations only when they lack a conventional term for the meaning they wish to convey, while children produce many innovative forms that are in fact pre-empted by existing conventional terms in the language.

6.5 Organizing meanings by domain

In making preliminary inferences about the meaning of new words, both children and adults depend on the context of use in terms of (a) physical and (b) conversational co-presence. In this, they also attend to the fact that any new, unfamiliar, word contrasts in meaning with other words already known, in particular with words belonging to the same domain (Clark Reference Clark and MacWhinney1987, Reference Clark1990, Reference Clark, Miller and Eimas1995, Reference Clark, Syrett and Arunachalam2018). Each piece of additional information offered provides a basis for inferring the nature of the contrast in meaning between a new word (e.g., owl) and other related words like duck and bird already known to the child (see Chi & Koeske Reference Chi and Koeske1983; Callanan Reference Callanan1990; Johnson & Mervis Reference Johnson and Mervis1994; Clark Reference Clark, Beaver, Casillas Martínez, Clark and Kaufmann2002; Clark & Wong Reference Clark and Andrew2002; Clark Reference Clark2007, Reference Clark2010; Clark & Estigarribia Reference Clark and Estigarribia2011; Peters & Yu Reference Peters and Yu2021).

Adults make use of conversational co-presence by offering information about inclusion or class membership (an owl is a bird), as well as information about parts and properties (that’s his tail; this is the handle), about characteristic noises (owls go hoo; cats miaou), about ways of moving (the wheel turns like this, with a demonstrating gesture), about functions (this spoon is for stirring; that bowl is for soup), about ontogeny (a lamb is a baby sheep; a duckling is a baby duck), about habitat (talk about kennels, stables, fields, burrows, etc.), about history, and about terms for other entities and actions in the same domain. This added information provides often extensive material on which children can base still further inferences about the probable meaning of an unfamiliar word in a particular context, and so start to link it to words they already know, and simultaneously contrast it with those words as well (see Saji et al. Reference Saji, Imai, Saalbach, Zhang, Shu and Okada2011; Hills Reference Hills2013; Yurovsky et al. Reference Yurovsky, Fricker, Yu and Smith2014; Clark Reference Clark, Syrett and Arunachalam2018).

As children add more words to their vocabulary, they start to organize words stored in memory so far. They group words that belong to the same semantic and conceptual domain, e.g., words for animals, vehicles, toys, plants, cups and glasses, body-parts, and so on. Over time they add to each domain the relevant words for associated parts (e.g., arms, feet; wheels, handles), sounds (e.g., bark, neigh, shout), and actions (e.g., walk, run, hop, jump), and also link the meanings of words within a domain to each other through such relations as subordinate to superordinate, for example, for a trio like retriever, dog, and animal, beginning as young as age two (Clark et al. Reference Clark, Gelman and Lane1985; Gelman et al. Reference Gelman, Wilcox and Clark1989; Johnson & Mervis Reference Johnson and Mervis1994; Clark & Svaib Reference Clark and Svaib1997; Clark Reference Clark, Syrett and Arunachalam2018).

Children readily make inferences about the meanings and relations among new and familiar words. When adults use an unfamiliar word, children make inferences about candidate referents based on joint attention in that context. What is actually in joint attention early on may be just what is in the child’s immediate field of vision at age 1 and 2 (Yu & Smith Reference Yu and Smith2011) or what is being pointed at, held out, and looked at by the adult (Clark & Estigarribia Reference Clark and Estigarribia2011). Children readily infer, again from at least age 2 on, that, when told ‘an X is a kind of Y’, Y is superordinate to X and therefore includes X (Clark & Grossman Reference Clark and Grossman1998). Children this age can also assign more than one word to a specific referent, so a sailor can also be a bear, or a dog also be a postman, for example, as in the Richard Scarry books for young children (see Clark Reference Clark1997; Clark & Svaib Reference Clark and Svaib1997). Again, children start to establish such relations among words in some domains as early as age 2.

At the same time, many of these word meanings remain partial meanings because children have as yet had only limited exposure to the possible range of referents for a word, and only limited exposure to other terms related to that word in meaning. Yet their usage in production allows for reasonable communication, even though they have only a partial meaning for each term. It is important to note here that children readily make inferences in context about the probable referent on each occasion for a familiar word, and they also rely on inferences in context to assign possible meanings for new words heard from adult speakers, just as adults do (see Grice Reference Grice1987; Recanati Reference Recanati, Russell and Fara2014). Assigning at least some meaning to unfamiliar words in context helps children begin to structure and align conceptual domains with the lexical items available for that domain in the language they are acquiring. This makes such words more readily available, even when the meanings are still incomplete, for use in communicating with others.

Overall, these findings for acquisition show: (a) children need exposure to recurring coherent objects and events in joint attention as they map some meaning to a new word; (b) they need to hear the same word(s) used across a variety of contexts; and (c) the number of exposures they need to learn a new label for a particular category type may vary with how many words they already know in the relevant domain. In most studies of lexical acquisition, researchers have tracked some of the stages that children go through as they assign an initial meaning and then learn more about the conventional meaning of a term, the meaning assumed by adult speakers in a particular language community. This tracking has often been done in terms of appropriate comprehension, or appropriate production, but few studies have compared the two processes. So there are many details that we have yet to fill in as children come to align more of their production with comprehension. Building up an adult-like vocabulary takes a long time, and the meanings of many terms can long remain incomplete, not only for children but also for adults.

7. Partial meanings in adults

By the time speakers reach adulthood, they have accrued knowledge about all sorts of everyday domains and the activities associated with them in their culture. And they have amassed a large vocabulary for talking about many of these domains. What they know, and how they talk about what they know, provides the primary route for transmitting knowledge about the conventions on word use to younger speakers, and in particular to children beginning to acquire language. We tend to take for granted that speakers within a particular community agree on the convention that governs uses of a particular word. That is, within our own language community, we agree on what counts as a table, say, and that can therefore be referred to by the word table. But we also know that words can be stretched in various ways, so a speaker could refer to a flat-topped rock as our table when picnicking, because the rock functions as a table on that occasion. And different speech communities, using the same language, can also arrive at somewhat different conventions on when to produce and how to interpret certain words, e.g., elevator versus lift, pavement versus side-walk, or boot versus trunk in British versus American English.

Reliance on partial meanings, then, arise when speakers (a) know only part of the conventional meaning, just as when children use dog to refer only to a specific dog (rare) or only to prototypical dogs, say, and (b) extend a word to refer to entities or actions that are similar and for which the speaker lacks a term, as when young children overextend a noun like dog to refer to other four-legged mammal-shaped entities, or a verb like hit to refer to actions of hitting, touching, and patting. Both children and adults rely on partial meanings of both types. And like children, adults freely coin new words to fill gaps. Unlike children, though, adults only coin new words when they know of no existing word with just the meaning they wish to convey. The child’s use of a compound like fire-dog in I want a fire-dog, meaning ‘a dog like the one found at the site of a local fire’ depends on common ground with the adult addressee and so is analogous in its use to the adult’s production of the Ferrari-woman for ‘the woman who wished to be buried in her Ferrari’, a meaning only available when speaker and addressee share the information relevant to that interpretation as part of their common ground (see Clark & Clark Reference Clark and Clark1979; Clark & Gerrig Reference Clark and Gerrig1983; Weiskopf Reference Weiskopf2007).

Effectively, speakers observe the conventions for using words, and so show that they have attached approximately the same meanings to those words as other members of the same language community, so they can draw on those in order to communicate effectively. For conventional meanings, then, there is a form that speakers expect to be used in their language community (Lewis Reference Lewis1969; Garrod & Doherty Reference Garrod and Doherty1994), and the speaker’s choices of words specify both the meaning and the perspective the speaker wishes to convey (Clark Reference Clark1988, Reference Clark1993, Reference Clark1997). Underlying this view is the assumption that speakers within a speech community share the same conventions, the same meanings, in order to coordinate and communicate effectively (Hurford Reference Hurford1989; Smith Reference Smith and Tallerman2005).

The general notion of convention, as characterized by Lewis (Reference Lewis1969: 42), assumes that ‘everyone conforms to R [a regularity]’, and ‘everyone expects everyone else to conform to R’ because they thereby solve a coordination problem in communicating with each other. Lewis’s formulation is spelt out in (11):

Language works as a system for communication because the speakers within a community agree on the conventions when they use words to refer. But do all speakers necessarily set up identical representations for the meanings of the terms they use? To what extent can they get by with partial but overlapping representations instead? Do they indeed always share the same meaning for a word, or might one speaker have only a partial meaning compared to that of their interlocutor?

Partial meanings typically overlap in part with full, or fuller, conventional meanings, and this overlap is good enough on many occasions for the person with only a partial meaning to understand what the other speaker is talking about. On occasion, though, the partial-meaning speaker has to ask follow-up questions about what the other person intends in using a particular word. Consider the nouns in (12), where many adults often know only that each term for a subtype belongs to a more general domain (the words given in caps), but know little or nothing more about any one subtype in that domain. That is, they are unable to reliably identify or refer to instances of these subtypes, although they understand that another speaker is using words from a particular domain to refer to an instance of a subtype that belongs in that domain.

In many domains, adults too have only partial meanings, incomplete conventional meanings, for many terms like those in (12). What they know about the meanings of such terms as rowan, corgi, stonechat, finial, or cleat is based on partial knowledge, so when they use the words in comprehension or production, they are relying on partial meanings. But they can combine partial knowledge in each case with additional inferences based on the physical setting and the conversational context, as in the case of the sailing term stay, in (13), produced by a speaker standing on the deck of a sailing boat, pointing at a wire running from deck to mast-top, and saying: ‘We’ll need to replace that stay.’

The same holds for many tree names, recognized by speakers as such, where those same speakers are unable to identify the leaves of each tree-type, or even instances of the trees themselves. Hilary Putnam (Reference Putnam1974) famously discussed being unable to distinguish a beech from an elm among trees, a clear case of his therefore having only partial knowledge about the meanings of the two terms for these tree types (see further Popkin Reference Popkin2017 on tree blindness; also Wolff, Medin, & Pankratz Reference Wolff, Medin and Pankratz1999).

Figure 1 Stays on a sailing boat

Much the same holds for terms for subcategories in many other domains of knowledge. The point here is that speakers manage to communicate most of the time even when they have only partial knowledge of the word meanings – a curlew is some kind of bird, for instance – and they only master the full meaning of a term, its conventional meaning for the community of birders here, when they learn more about the relevant domain of knowledge. In short, adult speakers rely on a large number of partial meanings in their vocabulary, such that the meanings they have represented in memory often fail to fully match the meanings represented by other speakers in the same language community, speakers who happen to know more about the domain in question and hence more about the meanings of the terms used for referring to elements in that domain.

In order to learn about a particular domain of knowledge, people need a vocabulary so they can access, remember, and communicate precisely about that area of expertise. This was pointed out by Bross (Reference Bross, Murphy, Pressman and Mirand1973: 217), for surgeons who necessarily depend on having mastered the terms for anatomy in medicine:

How did the surgeon acquire his knowledge of the structure of the human body? In part this comes from the surgeon’s first-hand experience during his long training. But what made this experience fruitful was the surgeon’s earlier training, the distillation of generations of past experience which was transmitted to the surgeon in his anatomy classes.

…A highly specialized sublanguage has evolved for the sole purpose of describing this structure. The surgeon had to learn this jargon of anatomy before the anatomical facts could be effectively transmitted to him. Thus, underlying the ‘effective action’ of the surgeon is an ‘effective language’.

In the same way, birders need to learn not only terms for different kinds of birds, but also how to recognize each type from its plumage, flight patterns, habitat, songs, nests, and eggs. The same applies in any specialized domain of knowledge.

Knowledge about a domain plays a central role in the acquisition of the relevant word meanings for the terms used in talk about that domain. That is, lexical items that mark distinctions and are linked to each other in meaning play an essential role in communicating about elements in a specific domain and hence in the transmission of knowledge about that domain. The more people learn about a domain, the more detailed their meanings for terms that refer to elements in that domain become. This then makes for more precise comprehension among people who share the same degree of knowledge. Notice that this complicates any view of how much information to include in the meaning of a word, with the line between what is semantic and what conceptual made increasingly difficult to draw, especially in processing accounts of language use (see further Hogeweg & Vicente Reference Hogeweg and Vicente2020).

When people do not share the same amount of knowledge about a domain, speakers must assess how much their addressees actually know when they talk about particular aspects of a domain, and they must then provide additional information, as needed, to ensure understanding. In short, more expert speakers must always assess how much less expert interlocutors are likely to know – how much common ground speaker and addressee share – when they talk with them about a specific domain, whether in medicine, birding, music, or sports.

8. Usage that is ‘good enough’

On many occasions, speakers may find themselves participating in conversations where they do not know much about the topic under discussion. But they may know just enough about the meanings of certain words to get the gist of what is being talked about. How often does this happen? – Whenever a speaker has only partial knowledge of a domain and hence only partial lexical representations for the meanings of some, or of many, of the words being used. Take words for kinds of tools, birds, plants, machine parts, or boats, when people have only partial knowledge of many or most of the relevant word meanings (e.g., only ‘is a kind of tool’ for an adze; ‘is a kind of (small) bird’ for a wren; ‘is a kind of boat’ for a yawl; ‘is a kind of tree’ for a rowan, and so on), such that these speakers are unable to identify and label instances of the relevant entities. Yet knowing only that a word designates a kind of tree can often be enough to follow what a speaker intends to convey on a particular occasion. This, then, is a matter of comprehension, where the non-expert has only a partial meaning available, a meaning that may be just enough to identify the domain being talked about, and where that in turn may be just good enough on that occasion in allowing the addressee to then follow up appropriately in the next turn at talk with an utterance or an action pertinent to the original speaker’s utterance (Ferreira, Bailey & Ferraro Reference Ferreira, Karl and Ferraro2002; Ferreira & Patson Reference Ferreira and Patson2007).

Addressees, of course, may be able to make only a few of the possible appropriate inferences in context as they plan and produce their next utterance, so combining any such inferences with a minimal effort at an initial interpretation is a reasonable approach in trying to understand the speaker (Sanford & Sturt Reference Sanford and Sturt2002). Ferreira proposed that people often operate with what she called ‘shallow’ or incomplete representations of what the speaker has just said because of time constraints on turns within a conversation (Ferreira & Patson Reference Ferreira and Patson2007). She argued that people could make use of such ‘good enough’ representations in comprehension because these allow them to do the least amount of work needed in order to arrive at an interpretation of what the speaker just said. However, this view of good-enough processing for comprehension appears to ignore the fact that speaker and addressee must coordinate, so that their contributions in subsequent turns will make sense, given the topic being addressed. That is, time constraints may actually play a smaller role than having partial meanings does in arriving at some interpretation of a speaker’s utterance.

Speakers typically choose a particular perspective in conveying information about an object or event, and to do this, choose to produce the terms that seem most appropriate for the perspective being presented – for example, choosing between the dog versus the spaniel in referring to a particular dog, or between that pest versus the Siamese in talking about a particular cat (Ravn Reference Ravn1989; Clark Reference Clark1997). This is not a matter of the most specific term being regarded as the most precise choice for referring to a particular entity, but rather a matter of making the lexical choice that best conveys the perspective the speaker wishes to convey on that occasion. At the same time, for the speaker, one could argue that the most frequent term for referring to something is generally the one that may be most accessible for retrieval from memory, and so might be the more likely term to be produced by the speaker of the next turn (Koranda, Zettersten & MacDonald Reference Koranda, Zettersten and MacDonald2018; Goldberg Reference Goldberg2019; Lee, Lew-Williams & Goldberg Reference Lee, Lew-Williams and Goldberg2021). But here again, accessibility on each occasion must be weighed against the speaker’s choice of perspective (Clark Reference Clark1997).

When speakers retrieve words from memory as they plan an utterance, they need to balance both the accessibility of a word (measured by its frequency) and the perspective they wish to present to the addressee on the object or event they wish to talk about. As a result, what is ‘good enough’ for processing for comprehension may not match what is ‘good enough’ for processing for production. The issue here is how speakers and addressees coordinate so as to communicate with each other as effectively as possible despite disparities in knowledge about certain domains.

Coordination among interlocutors here depends on assessing how much knowledge about a topic or a domain is in common ground. One place where this can be examined is where the speaker produces a lexical innovation, a new word coined just for the occasion, one that will actually be quite comprehensible to the addressee given the physical and conversational context of the utterance. For example, in the case of a newly coined denominal verb in English like to porch in The boy porched the newspaper (Clark & Clark Reference Clark and Clark1979: 787), the speaker means to denote:

-

(i) the kind of situation;

-

(ii) that he has good reason to believe;

-

(iii) that on this occasion the addressee can readily compute;

-

(iv) uniquely;

-

(v) on the basis of their mutual knowledge;

-

(vi) in such a way that the parent noun denotes one role in the situation, and the remaining surface arguments of the denominal verb denote other roles in the situation.

That is, the addressee knows what the referent of porch, the parent noun, generally is, and so, given the physical and conversational context, can infer the intended meaning of the innovative verb porch in relation to a newspaper. Other lexical innovations like compound nouns require the same Gricean conditions for the interpretation of the speaker’s intention (Weiskopf Reference Weiskopf2007). In the case of partial meanings, I suggest that speakers rely on a similar Gricean contract with their addressees, with adherence to conditions (i) through (v), such that pragmatic inferences based on the physical setting and the conversational context allow the addressee to understand well enough for that occasion what the speaker intends.

Do partial lexical entries impede communication? This depends on how skilled speakers are at assessing what their addressees know. Addressees often manage in context with only partial knowledge. If a speaker uses a noun phrase like the chaffinch, an addressee with partial knowledge may well know only that the term chaffinch refers to some kind of bird. That may be all. The same holds for uses of terms like alder or rowan, both referring to kinds of tree. In short, what addressees can understand, even if it is only minimal, may be good enough on many occasions. However, they will be unlikely to produce such terms themselves, so their apparent comprehension will not be matched in their production. This asymmetry between comprehension and production is only reduced once less expert speakers (like the addressees just mentioned) learn more about the domain in question (see e.g., O’Reilly, Wang & Sabatini Reference O’Reilly, Wang and Sabatini2019).

9. Degrees of expertise and knowledge about conventions in language

What speakers represent about word meanings, the conventions they observe with each other, depends on how much they know about a domain of knowledge. For all kinds of everyday activities, most speakers can assume that their addressees share the same amount of knowledge and so depend on stored representations in memory that are very close to those stored by other speakers in the same speech community. But some speakers may know a lot more about dogs, for instance, others more about gardening and plants, still others more about bicycles, and yet others more about history or archaeology. In each case, people are liable to encounter words for which they have partial meanings only and so may have to ask for more information on occasion in order to make sure they have fully understood what the speaker intended.

The precise nature of the conventional meaning being assumed depends on the degree of knowledge shared by speaker and addressee. And how that shared knowledge is made use of depends in turn on the speaker’s assessment of common ground with the current addressee (H. Clark Reference Clark1996; Clark Reference Clark, MacWhinney and O’Grady2015). This suggests that there is not just one single specification for the conventional meaning of a word, but rather a series of entries, overlapping but often differing in all sorts of details from one speaker to the next (see Bolinger Reference Bolinger1965, Reference Bolinger1977; Cooper & Ranta Reference Cooper, Ranta, Cooper and Kempson2008; Noble & Fernández Reference Noble, Fernández, Roberts, Cuskley, McCronon, Barceló-Coblijn, Fehér and Verhoef2018).

Speakers continue to learn, on a life-long basis, as they encounter new domains, master new skills, add new areas of knowledge at varying levels of expertise, and, in each case, begin to acquire the relevant vocabulary. We may know a lot about everyday living in a city, yet have little knowledge and little vocabulary for life on a farm. We may be experts on one area – sailing, say, yet know little or nothing about mountain-climbing, chess, architecture, painting, gymnastics, figure-skating, molecular biology, or wine-making, etc. And we lack many or most of the words we would need for talking about those domains. We may be familiar with some terms from such domains, but not with their full conventional meanings in the way an expert on that domain would be. It is this state of affairs that raises questions about how much of a meaning we actually know for terms like gingko, waxwing, rudder, pawn, carabiner, corbel, angiogram, or culture. The continuum in knowledge about conventional word meanings for adults goes from ‘zero’ to ‘expertise’ in any one field of knowledge, with our degree of knowledge strongly supported by the vocabulary and attendant contrasts in meaning for the words available for each domain. We often lack the words we need and, while we may be familiar with a few terms, we do not know their ‘full’ meanings in the way an expert user would.

To take one example, the term culture is generally defined as encompassing the arts and other intellectual achievements regarded as a whole, e.g., ‘twentieth-century culture’. This is likely the first meaning we would all come up with. But is it the first or main conventional meaning? Culture has another sense in biology: the growing of bacteria, tissue cells, etc., in a medium containing nutrients. And a third sense: the cultivation of plants. This is actually the original sense, but nowadays perhaps the least well known (except perhaps in the form viticulture). In Middle French, until the end of the sixteenth century, culture referred to cultivation of the soil. But by the late seventeenth century, its sense had shifted to cultivation of the mind. And in English, the sense covering the arts dates only from early nineteenth-century usage. Changes like this pervade language (see Traugott & Dasher Reference Traugott and Dasher2001; Gärdenfors Reference Gärdenfors2018).

Just as elsewhere in the lexicon, the continuum of knowledge about conventional meanings for adult speakers of a language runs from ‘zero’ to ‘expertise’ in any one field of knowledge, with the degree of knowledge in any one person strongly supported by the vocabulary and any attendant contrasts in meaning among terms for the pertinent domain. In some domains all adults may be relatively expert as speakers, but in many others few are experts and they therefore, like children, rely on partial (often minimal) meanings for whatever terms they ‘know’.

In summary, all speakers possess graded knowledge of word meanings, depending on how much they know about different domains of knowledge. In some domains, people may be relatively expert but, in many others, few are experts and therefore strongly resemble children in their common reliance on partial meanings for whatever words they are at all familiar with. But the partial nature of adult knowledge about word meanings is generally obscured by the sheer number of terms that we, as adult speakers, know and use on a daily basis.Footnote

2

The more terms we are familiar with, the less obvious it is that, in many domains, we actually have only partial knowledge of the pertinent word meanings, knowledge that may be incremented in a gradual manner as we happen to learn more about a domain. The ultimate issue is this: Partial knowledge, and hence partial representations of meanings, complicates our view of what speakers know about lexical semantics and conventional meanings, as well as how adult speakers actually learn and make use of such word meanings. And such partial knowledge, along with extensive reliance on pragmatic inferences about both the physical and conversational context of a speaker’s utterances, also blurs the line linguists have tried to draw between semantics and pragmatics in language use. Both, together, play an essential role in how we understand and produce language.

References

Baldwin, Dare A. 1989. Priorities in children’s expectations about object-label reference: Form over color. Child Development 60, 1291–1306.CrossRefGoogle ScholarPubMed

Barrett, Martyn. 1978. Lexical development and overextension in child language. Journal of Child Language 5, 205–219.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

Bergelson, Elika & Aslin, Richard N.. 2017. Semantic specificity in one-year-olds’ word comprehension. Language Learning and Development 13, 481–501.Google ScholarPubMed

Bion, Ricardo A. H., Borovsky, Arielle & Fernald, Anne. 2013. Fast mapping, slow learning: Disambiguation of novel word–object mappings in relation to vocabulary learning at 18, 24, and 30 months. Cognition 126, 39–53.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

Bolinger, Dwight L. 1977. Meaning and form. London: Longman.Google Scholar

Bowerman, Melissa. 1978. The acquisition of word meaning: An investigation into some current conflicts. In Waterson, Natalie & Snow, Catherine E. (Eds.), The development of communication, 263–287. New York: Wiley.Google Scholar

Bowerman, Melissa. 2018. Ten lectures on language, cognition, and language acquisition. Dordrecht: Brill.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

Bross, Irwin D. J. 1973. Languages in cancer research. In Murphy, Gerald P., Pressman, David & Mirand, Edwin A. (eds.), Perspectives in cancer research and treatment, 213–221. New York: Alan R. Liss.Google Scholar

Callanan, Maureen A. 1990. Parents’ descriptions of objects: Potential data for children’s inferences about category principles. Cognitive Development 5, 101–122.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

Carey, Susan & Bartlett, Elsa. 1978. Acquiring a single new word. Papers & Reports in Child Language Development (10th Annual Child Language Research Forum, Stanford University) 15, 17–29.Google Scholar

Casasola, Marianella. 2008. The development of infants’ spatial categories. Current Directions in Psychological Science 17, 21–25.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

Chi, Michelene T. H. & Koeske, Randi D.. 1983. Network representation of a child’s dinosaur knowledge. Developmental Psychology 19, 29–39.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

Childers, Jane B., Paik, Jae H., Flores, Melissa, Lai, Gabrielle & Dolan, Megan. 2017. Does variability across events affect verb learning in English, Mandarin, and Korean? Cognitive Science 41, 808–830.CrossRefGoogle ScholarPubMed

Childers, Jane B., Parrish, Rebecca, Olson, Cristina V., Burch, Clare, Fung, Gavin & McIntyre, Kevin P.. 2016. Early verb learning: How do children learn how to compare events? Journal of Cognition and Development 17, 41–66.CrossRefGoogle ScholarPubMed

Choi, Soonja & Bowerman, Melissa. 1991. Learning to express motion events in English and Korean: The influence of language-specific lexicalization patterns. Cognition 41, 83–121.Google ScholarPubMed

Chouinard, Michelle M. & Clark, Eve V.. 2003. Adult reformulations of child errors as negative evidence. Journal of Child Language 30, 637–669.CrossRefGoogle ScholarPubMed