We do still say ‘biscuit’ in normal speech and our supermarkets, even the one owned by Walmart, still have biscuit aisles. However we are widely exposed to American culture and in the context of sports commentary «raiding the cookie jar» does work better than «raiding the biscuit tin»: somehow «raiding the biscuit tin» just feels much more petty. This is perhaps because, although there is an overlap, an American style cookie tends to be bigger, softer and generally more indulgent than a British biscuit. In fact large, soft, special treat biscuits are sometimes sold as ‘cookies’ although they are usually so large we would probably not think of them as a ‘biscuit’ anyway.

Having said that Americanisms do appear in proper English, especially when promoted by American companies. Following the penetration of the British market by McDonalds and Starbucks most vendors of coffee, including iconic British brands, now offer ‘regular’ cups rather than ‘standard’ or ‘medium’. That is unless they aspire to Italian sophistication and call them ‘medio’.

One area where you will hear ‘cookie’, though, is computing. Small files downloaded to your computer by websites are always called ‘cookies’. I can’t imagine any British person wanting to change that. In fact most users probably don’t even make the connection between leaving the file and presenting a child with a biscuit.

Table of Contents

- What words do British people say often?

- What words are different in America to England?

- What is the most American word?

- Do British say awesome?

- What are American English words?

Biscuit

Biscuit (UK) / Cookie (US) In the US, cookies are flat, round snacks made of sweet dough. In the UK, these are generally called biscuits, although people do call the bigger, softer kind cookies, too.

What words do British people say often?

20 of the Most Common British Slang Words

- Fit (adj) So, in the UK fit doesn’t just mean that you go to the gym a lot.

- Loo (noun)

- Dodgy (adj)

- Proper (adj)

- Knackered (adj)

- Quid (noun)

- Skint (noun)

- To Skive (verb) Skiver (noun)

What words are different in America to England?

18 Words That Have Completely Different Meanings in England and America

- Purse. In American English, “purse” is a term used to describe a woman’s handbag.

- Chips.

- Biscuit.

- Football.

- Jumper.

- Fancy dress.

- Bird.

- Braces.

What is the most American word?

Here we take a look at some of our favourite American words that are typically and explore their meanings.

- Cool. No word is more American than cool, and the word has come a long way.

- Awesome. Here’s another word whose meaning has changed a great deal over the years.

- Gosh.

- Dude.

- Faucet.

- Diaper.

- Bangs.

- Booger.

Do British say awesome?

According to a study by Lancaster University and Cambridge University Press, Britain has all but abandoned the former adjective in favour of the latter. Early evidence from their project, the Spoken British National Corpus 2014, shows that “awesome” now turns up in conversation 72 times per million words.

What are American English words?

American and British Vocabulary and Word Choice

| American English | British English |

|---|---|

| attorney | barrister, solicitor |

| cookie | biscuit |

| hood | bonnet |

| trunk | boot |

Как-то Бернард Шоу написал, что Великобритания и США – две страны, которые разделяет английский язык. Парадокс? Да и нет. Существует достаточно большой пласт лексики, которая употребляется исключительно в Великобритании или только в США. Например, англичане называют баклажан «AUBERGINE», а американцы – «EGGPLANT».

Но существует достаточно большая группа слов, которые используются в обеих странах, правда, в каждой стране у них свое значение. У вас могут возникнуть трудности с переводом, если вы не знаете, по какую сторону Атлантики был написан текст с использованием этих слов. Например, если в США ваш знакомый говорит, что собирается на вечеринку и по этому случаю наденет «PANTS» и «SUSPENDERS» (брюки с подтяжками), вы спокойно прореагируете на его слова, но можете обсудить его отношение к моде. Если же подобное описание гардероба вы услышите от британца, то вы скорее всего поинтересуетесь характером вечеринки и посоветуете знакомому остаться дома, потому что в Англии «PANTS» — кальсоны, а «SUSPENDERS» — пояс для чулок.

Но иногда разница между словами, которые употребляются в обеих странах, настолько тонкая, что ошибок в употреблении не избежать. В качестве примера можно взять два существительных – «BISCUIT» и «COOKIE».

BISCUIT

В Великобритании «BISCUIT» это печенье, часто покрытое шоколадом, в тесто при выпечке добавляют клюкву. Его подают к чаю на сладкое. Поскольку печенье достаточно жесткое, его можно макать в чай или кофе.

В США «BISCUIT» — это вид выпечки, которая может служить основой для бутерброда, на которую можно положить, например, омлет с беконом. Такое печенье с кусочком курятины – отличное блюдо на ужин.

В словарях вы можете найти следующие толкования. Например, в Oxford English Dictionary вы найдете два определения. Согласно одному из них, слово «biscuit» происходит от латинского «bisotum (panem)», что означает «хлеб, прошедший двойную выпечку». Отсюда и консистенция британского печенья – оно твердое и хрустящее.

Американское печенье (BISCUIT) скорее напоминает вид выпечки, которая в Великобритании называется «SCONE» (сдобная булочка с изюмом или клюквой), в то время как в США «SCONE» это подобие лепешки. Произношение также отличается. Сравните — Br. E. /skəʊn/ и Am.E. / /skɒn/. Остается неясным, как два различных вида выпечки имеют одно и то же название. Нам остается только предположить, что это произошло под влиянием французского языка на юге США.

COOKIE

Со словом «COOKIE» такая же история. В Великобритании «COOKIE» — мягкое и не сухое печенье. Оно, как правило, более питательное и калорийное чем то, которое британцы называют «BISCUIT». Печенье, которое у американцев называется «COOKIE», одновременно сочетает в себе то, что британцы называют «BISCUIT» и «COOKIE». Слово происходит от голландского «koekje» — маленькое печенье. Предположительно, появлению печенья «cookie» мы обязаны выходцам из Голландии, поселившимся в США.

Ну что, увидели разницу? Проще говоря, британское печенье «BISCUIT» это американское «COOKIE», а американское печенье «COOKIE» это то, что англичане тоже называют «COOKIE». А американское печенье «BISCUIT» это британская выпечка «SCONE». Видите, как просто! А что бы вы выбрали к чаю?

Репетиторы по английскому языку на Study.ru.

В базе 102 репетиторов со средней ценой 1133

Оцените статью в один клик

It may seem logical to assume that the word cookie comes from the word cook, but, in fact, the two words are not related at all. The word cookie is actually Duch in origin and is actually related to the word cake. No, really, it makes perfect sense! Read on to find out more. And then, find the answer to another age-old mystery: Why do the British call cookies biscuits?

See also: Origin of the Baker’s Dozen

New Amsterdam (Nieuw Amsterdam) was a Dutch colonial settlement on the southern tip of Manhattan Island. Established in 1625, it originated as a fur-trading settlement. There, traditional treats called koekjes were baked on all sorts of occasions. The word for cake, in Dutch, was koek. When the suffix -je was added, it designated “little cakes.”

These little cakes kept their name for quite some time, but things started changing in 1674 when the English got control of the colony and started Anglicizing everything. What happened to New Amsterdam? It’s now New York! The first thing the English did was to change the name of the colony, in honor of the Duke of York, who is the guy who got it in his head to go to war against the Dutch in the first place.

Nevertheless, koekjes kept their name for a couple of decades. It took that long for most of the Dutch people in the colony to be regularly speaking English, which led to the word koekjes to naturally evolve into a more English sounding word. According to written evidence (we only have written mentions to surmise when a word “officially” enters a language) an early iteration in English was cockies which then led to the word cookies. And that is how we got our English word for “little cakes,” which is really what a cookie is. Like many English words, it is of basically Germanic origin. But in this instance, it came right to America rather than entering the language earlier, via Britain. The Duch sound for the long oo is written as oe, so the word koekje sounds pretty similar to the English word cookie. It sounds a bit like KOOOK-YES to my ear.

So, no, the word cookie has nothing to do with the word cook. The origin of the word cook is completely different, being of Latin origin. You can read more about words related to cook here at CulinaryLore.

Why Do the British Say Biscuit Instead of Cookie?

This history lesson also helps explain another mystery. People often wonder why the English called a cookie a biscuit (or a sweet biscuit) and why we, in America call the same sort of thing a cookie. Now you know. New York became such an important city that the word cookie, which we got from the Dutch, became the standard word for all such baked goods. Prior to this, cookies would have been called biscuits, just like they still are today in England.

Biscuits, Cookies, and Crackers

The English word biscuit came from the Old French bescuit, which literally meant “twice cooked.” The bis part meant “twice” and the –cuit part was derived from the Latin coctus, meaning “cooked.” Coctus was the past participle of the verb couqere meaning “to cook.” The Italian word biscotti is also related. Biscuit, originally, would have referred to any type of hard, flat, and crisp bread, whether sweet or not.

At some point, Americans not only were referring to sweet biscuits as cookies, but began calling unsweetened biscuits, anything hard, flat, and crisp, crackers. This seems confusing when people try to relate the word for say, a saltine, with the word referring to “mean white folks” usually of Scots-Irish descent, who settled on the frontiers of the Virginias, Carolinas, Maryland, and Georgia. It’s also associated with “cracking the whip” and to “cracking corn.” However, the word originally came from Elizabethan England, and was used to describe a braggart or boaster. The word “crack” in Middle English referred to entertaining or fun conversation, and today we still crack jokes. However, the word for the food, whether related to this or not, did not originate in America.

Americans developed very specific classifying labels for two different sorts of biscuits. Thin, hard, flat, and crispy biscuits became crackers, while the more luxurious and sweetened biscuits became cookies. In England, the word was an over-riding term used to describe all such products. But this does not mean that there were not more specific names for specific products, for instance, the “cream cracker,” which contained no cream, and was an Irish invention. The soda cracker, an American product, predates the cream cracker, and, as we shall see, the word cracker, in the United States, predates the word biscuit as well.

The word biscuit got to England via the French, who had, as mentioned above, gotten it from the Romans. When the word came into the French language it is hard to say. However, the word did not really come to America, via England, until around the middle of the 19th century. Before this time, the word biscuit had never been applied to these products, in the states. On the other hand, some American bakers had begun to produce products called crackers in the later 18th century. They were hard, flat, plain, unsweetened but crisps products which became very popular and in demand. Great demand for these crackers even occurred overseas, but the cracker designation was promptly dropped and they were absorbed into the generic “biscuit” classification. The name of cracker lived on the in United States, however.

Hard Tack or “Ship’s Bread”

One of the first, if not the first, cracker manufacturing businesses in the United States was the firm of Theodore Pearson in Newburyport, Massachusetts, beginning in 1792. Pearson’s crackers were large, round, crisp and not exactly refined crackers which were known as “pilot” or as “ship” bread, as well as “hard tack.” These were popular with merchant marines who welcomed any type of food that would keep for a long period aboard a ship, and ordinary bread perished quickly.

An early competitor of Pearson was Joshua Bent, who had a craker baking operation in Milton, Massachussetts in 1801. It only operated three days a week, being worked by bent and some of his family, and then the cracker were sold by wagon the rest of the wee, and delivered to various points throughout the country. This was the start of the famous Bent’s water-cracker, which has an international reputation, and is still made with the same recipe today, by an unleavened dough of flour, water, and salt. These products were sold in general stores out of open barrels, which is were the term cracker barrel came from, even though we never sell crackers out of barrels today.

After this early period, and throughout the 1800’s, scores of cracker baking companies sprang up, mostly on the East Coast. The advent of machine for automating the dough flattening process set the cracker business on fire. Demand for crackers was also helped along by the gold rush of 1849, and other pioneering movements, where the cracker seemed ideally suited for a long haul across the country. At this time, besides distinctly local creations, there were five main types of “hard bread” or crackers being sold in mass, the pilot of ship’s bread, the Bent’s water cracker, the soft or butter cracker, and the soda cracker. The last three were actually from fermented dough and contained shortening, making them lighter and softer than the old ship’s bread, and thus more popular.

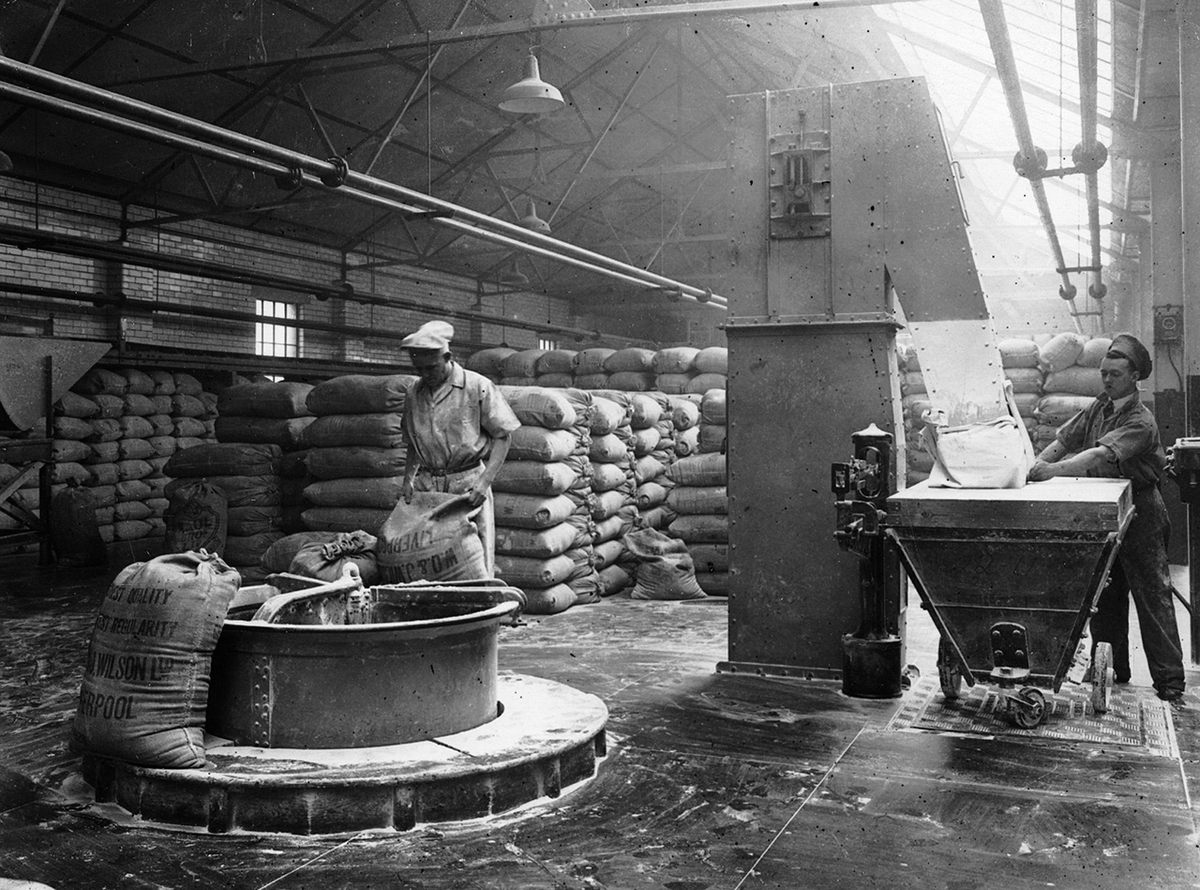

It wasn’t until after 1855 that the fancy sweetened English “biscuit” came to the states, from firms such as Huntley and Palmer, Peak, Frean and Company, and Belcher and Larrabee. English importers, however, found their products selling so well, and so widely, that they soon began to set up manufacturing locations within the United States and before long, English importation all but fizzled out. In fact, the trade even reversed direction, so that several American firms like Holmes and Coutts, the Wilsons, and F.A. Kennedy began to sell high-end unsweetened products to the European market. After a while, the smaller firms began consolidating into several large firms

The New York Biscuit Company was formed in 1890 in Chicago, from 23 firms, nearly all the cracker firms in New York and the New England states. It became the largest and most complete operation in the country. The America Biscuit and Manufacturing Company was formed that same year from a number of Midwestern firms. A fierce price war began between these two companies, but in 1898 they united to form the National Biscuit Company (Nabisco), under the management of Adophus W. Green. Many plants were closed and many products were dropped, as Green planned to concentrate production on the soda cracker. The company settled on “Uneeda Biscuit” as the name of its flagship product, and the “In-Er-Seal” waxed paper wrapper was developed to keep the crackers fresh.

“Out of the Cracker Barrel –

From Animal Crackers to ZuZus

By 1908 the company was also selling the Fig Newton, ZuZu Ginger Snaps, Graham Crackers, Premium soda Crackers or Saltines, Social Tea Biscuits (sweet), oyster crackers called Oysterettes, Animal Crackers, Arrowroot crackers, Zwieback, and sugar wafers called Nabiscos.

The little boy in the advertisement, wearing a raincoat, was the Gordon Stiles, the five year old nephew of an advertising writer. This image of the rain-slicker clad boy became universally familiar. Why the rain gear? It was to emphasize the fact that the crackers wouldn’t be ruined by water, since they were sealed safely inside a “sanitary, waxed, air and moisture proof package.” If images images of the Morton Salt Girl come to mind, you would be forgiven for thinking that one company copied the other. In this case it would have to be Morton who copied Nabisco, since the Morton ads came later. However, the Morton girl’s being shown in the rain was not a random attempt to play off an earlier advertising icon; it was to emphasize the idea that Morton’s salt was the only brand that would not become sticky in humid weather.

The Southern Soft Biscuit

Obviously, no discussion of the word biscuit can fail to mention the Southern biscuit, which really adds to the confusion, being a soft leavened bread instead of a hard cracker, highly perishable, and completely misnamed, at least by etiological standards, being definitely not twice-baked.

Today’s Southern biscuit probably originated with the Beaten biscuit, which is claimed to have come from either Maryland or Virginia (close enough). These were unleavened breads made simply with flour, lard, and milk. The dough was beaten, with a special axe, wooden mallet, or other implement for up to 30 minutes. Since there was available yeast, no baking soda, having not been invented yet, and certainly no baking powder, cooks were looking for a way to help bread rise. The only viable chemical choice was pearl ash, which is actually potassium carbonate. To get pearl ash, you had to pour water over wood ashes and then collect the solid that was left. It so happens that this process is also used to make lye. What happens when you add lye to animal fat? You get soap. So what happened when they used pearl ash to leaven bread that contain lard? They got a bitter, soapy taste. The solution was pounding the dough, folding it over, pounding it some more, and repeating, until tiny air pockets formed in the dough, basically like blisters. Then, when the dough was baked off, the air in these pockets heated and expanded, thus expanding the pockets, and thus the bread.

This, of course, did not result in a light fluffy product like we have today, but something between a cracker and a biscuit. Despite the shortening effect of the lard, the heavy working of the dough developed the gluten in the flour to such an extent that the product would be much denser than today’s product. You don’t have to be an historian to imagine what happened next. Baking soda, and, eventually, baking powder, became available, replacing the beating process, and creating the light Southern biscuit, which has the same ingredients as the beaten biscuit, with the addition of baking powder (or baking soda and buttermilk). Since the dough did not have to be worked much a much lighter and softer product resulted.

The Word Cake

The word koek, and thus cookie, is closely related to the work cake which came from the Old Norse word kaka, in the thirteenth century. Although today we think of a cake as something made with very specific types of ingredients and techniques, the word originally had nothing to do with any specific recipe but referred to the shape: something round and flat on top, which may have been made from bread or other dough.

References

1. Dunton-Downer, Leslie, Mary F. Rhinelander, and Kris Goodfellow. The English Is Coming!: How One Language Is Sweeping the World. New York: Touchstone Book, 2010.

2. Morton, Mark. Cupboard Love: A Dictionary of Culinary Curiousities. Toronto: Insomniac, 2004.

3. Mozeson, Isaac. The Word: The Dictionary That Reveals the Hebrew Sources of English. New York: SPI, 2000.

4. Editors of the American Heritage Dictionaries, More Word Histories and Mysteries: From Aardvark to Zombie. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 2006.: manley : Manley, D. J. R. Biscuit, Cracker and Cookie Recipes for the Food Industry. Boca Raton, FL: CRC, 2001.

5. Edelstein, Sari. Food, Cuisine, and Cultural Competency for Culinary, Hospitality, and Nutrition Professionals. Sudbury, MA: Jones and Bartlett, 2011.

6. Wagenknecht, Edward. American Profile, 1900-1909. Amherst: University of Massachusetts, 1982.

7. Dotz, Warren, and Masud Husain. Meet Mr. Product: The Art of the Advertising Character. San Francisco: Chronicle, 2003.

You May Be Interested in These Articles

- Top Definitions

- Quiz

- Related Content

- Examples

- British

- Scientific

- Idioms And Phrases

This shows grade level based on the word’s complexity.

This shows grade level based on the word’s complexity.

noun, plural cook·ies

a small, usually round and flat cake, the size of an individual portion, made from stiff, sweetened dough, and baked.

Informal. dear; sweetheart (a term of address, usually connoting affection).

Slang.

- a person, usually of a specified character or type: a smart cookie; a tough cookie.

- an alluring young woman.

Also called http cook·ie, brows·er cook·ie .Digital Technology. a file or segment of data that identifies a unique user over time and across interactions with a website, sent by the web server through a browser, stored on a user’s hard drive, and sent back to the server each time the browser requests a web page: Your browser will run more efficiently after you clear the cache and cookies.

South Atlantic States (chiefly North Carolina). a doughnut.

verb (used with object), cook·ied,cook·ie·ing or cook·y·ing.

Digital Technology. to assign a cookie or cookies to (a website user): I’m not really comfortable being cookied all the time.

QUIZ

CAN YOU ANSWER THESE COMMON GRAMMAR DEBATES?

There are grammar debates that never die; and the ones highlighted in the questions in this quiz are sure to rile everyone up once again. Do you know how to answer the questions that cause some of the greatest grammar debates?

Which sentence is correct?

Idioms about cookie

toss / spill one’s cookies, Slang. to vomit.

Origin of cookie

First recorded in 1750–55; from Dutch koekie, dialectal variant of koekje, equivalent to koek “biscuit, cake” + -je diminutive suffix; see origin at cake

Words nearby cookie

cookery book, cookery stove, Cookeville, cook-general, cookhouse, cookie, cookie cutter, cookie jar, cookie press, cookies, cookie sheet

Dictionary.com Unabridged

Based on the Random House Unabridged Dictionary, © Random House, Inc. 2023

Words related to cookie

How to use cookie in a sentence

-

Many brands are now waking up to the deprecation of cookies.

-

These are included to support items that might otherwise crumble or melt through the oven’s internal rack during the cooking process, such as cookies, pizza, or egg-based dishes.

-

The penguin, according to my unscientific interpretation, was trying to share its seafood meal with me, like splitting a cookie with a friend.

-

Now, its attempt to replace the cookie is attracting regulatory attention.

-

That high fiber content weighs down breads and results in cookies that are toothsome, to put it gently.

-

There was also the grapefruit diet, the cabbage soup diet, and the cookie diet.

-

And “om nom nom nom” is more of a dig at Cookie Monster and Instagram foodies than it is at anyone else.

-

A personal favorite is “C Is For Cookie” for guiding me through a 1994 playground debate over how to spell the word.

-

In the early 1900s, stores in Mexican towns and cities began selling cookie-and-sugar calaveras, or skulls.

-

Cookie Monster has always been one of the most beloved features of that PBS childhood staple, Sesame Street.

-

You know this is the first day of school and you can’t run for a cookie if you get hungry.

-

She had a kettle of doughnuts a frying, and a whole lot of cookie paste ready to cut out and bake.

-

They had dismissed him, scornfully, stolen cookie in hand—but maybe it would be a bigger cookie than they dreamed!

-

Place one teaspoonful of filling on each cookie, cover with another cookie, press edges together.

-

«Stow that drivel, cookie,» growled a voice which I recognized as belonging to the older Fleming.

British Dictionary definitions for cookie

noun plural -ies

US and Canadian a small flat dry sweet or plain cake of many varieties, baked from a doughAlso called (in Britain and certain other countries): biscuit

a Scot word for bun

informal a personsmart cookie

computing a piece of data downloaded to a computer by a website, containing details of the preferences of that computer’s user which identify the user when revisiting that website

that’s the way the cookie crumbles informal matters are inevitably or unalterably so

Word Origin for cookie

C18: from Dutch koekje, diminutive of koek cake

Collins English Dictionary — Complete & Unabridged 2012 Digital Edition

© William Collins Sons & Co. Ltd. 1979, 1986 © HarperCollins

Publishers 1998, 2000, 2003, 2005, 2006, 2007, 2009, 2012

Scientific definitions for cookie

A collection of information, usually including a username and the current date and time, stored on the local computer of a person using the World Wide Web, used chiefly by websites to identify users who have previously registered or visited the site. Cookies are used to relate one computer transaction to a later one.

The American Heritage® Science Dictionary

Copyright © 2011. Published by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company. All rights reserved.

Other Idioms and Phrases with cookie

see hand in the till (cookie jar); that’s how the ball bounces (cookie crumbles); toss one’s cookies.

The American Heritage® Idioms Dictionary

Copyright © 2002, 2001, 1995 by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company. Published by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company.

I have noticed that British people usually say “biscuit” to describe what an American would call a “cookie”.

However, I just heard a sports broadcaster in the UK using the metaphor “I wonder when he will raid the cookie jar.” So, apparently British people do use the word cookie after all. Is that just an Americanism that the broadcaster was adopting, or do British people normally say cookie, and if so in what situations do they say cookie versus biscuit.

Answer

Okay, I think we have an answer, but unfortunately what has been posted is not very cogent, so I will sum up:

The British call cookies “biscuits”. They occasionally use the word “cookie” in the context of using Americanisms like “he got caught with his hand in the cookie jar”, or “that’s the way the cookie crumbles”.

Attribution

Source : Link , Question Author : Emma Dash , Answer Author : Emma Dash

I have noticed that British people usually say “biscuit” to describe what an American would call a “cookie”.

However, I just heard a sports broadcaster in the UK using the metaphor “I wonder when he will raid the cookie jar.” So, apparently British people do use the word cookie after all. Is that just an Americanism that the broadcaster was adopting, or do British people normally say cookie, and if so in what situations do they say cookie versus biscuit.

As far as I know they always call cookies biscuits and I have heard them refer to cookie jars as biscuit tins. But perhaps through media coverage we are all being exposed to other culture’s use of words. The sportscaster has perhaps had that certain phrase introduced into his vocabulary. Thanks to the internet/media, we now have the pleasure of hearing how other cultures use language and that surely intertwines into how we use it too.

Answered by Melody Flynn on July 13, 2021

We do still say ‘biscuit’ in normal speech and our supermarkets, even the one owned by Walmart, still have biscuit aisles. However we are widely exposed to American culture and in the context of sports commentary «raiding the cookie jar» does work better than «raiding the biscuit tin»: somehow «raiding the biscuit tin» just feels much more petty. This is perhaps because, although there is an overlap, an American style cookie tends to be bigger, softer and generally more indulgent than a British biscuit. In fact large, soft, special treat biscuits are sometimes sold as ‘cookies’ although they are usually so large we would probably not think of them as a ‘biscuit’ anyway.

Having said that Americanisms do appear in proper English, especially when promoted by American companies. Following the penetration of the British market by McDonalds and Starbucks most vendors of coffee, including iconic British brands, now offer ‘regular’ cups rather than ‘standard’ or ‘medium’. That is unless they aspire to Italian sophistication and call them ‘medio’.

One area where you will hear ‘cookie’, though, is computing. Small files downloaded to your computer by websites are always called ‘cookies’. I can’t imagine any British person wanting to change that. In fact most users probably don’t even make the connection between leaving the file and presenting a child with a biscuit.

Answered by BoldBen on July 13, 2021

As a British person, I have always known (and use) the expression

That’s the way the cookie crumbles.

given by the Oxford Dictionaries as a North American phrase. However I never buy cookies — even when that word is on the packet — but biscuits.

One British term for a cookie jar is

biscuit barrel

NOUNBritish

A small barrel-shaped container for biscuits.

I don’t know anybody who keeps biscuits in a jar.

Answered by Weather Vane on July 13, 2021

Okay, I think we have an answer, but unfortunately what has been posted is not very cogent, so I will sum up:

The British call cookies «biscuits». They occasionally use the word «cookie» in the context of using Americanisms like «he got caught with his hand in the cookie jar», or «that’s the way the cookie crumbles».

Answered by Emma Dash on July 13, 2021

In the UK a cookie is a particular type of biscuit with a high butter and sugar content so the dough melts during cooking giving a crispy edge with a softer centre.

Biscuit covers a wide range of recipes from sweet, semi-sweet, to savoury e.g. «biscuit for cheese» with a wide range a textures, shape thickness. Basically a baked good with aa element of crispy

A cookie is a biscuit, not all biscuits are cookies

Answered by Eddir Ryan on July 13, 2021

OK folks, today I am going to keep this post simple. Can anyone tell us the difference between a cookie and a biscuit?

Think there is no difference? THINK AGAIN.

The British – Biscuit lovers

Evidently, the British (and most of the Old Worlders I should think) are fans of those little hard snacks that snap and crunch as you sink your teeth into them. Some of them would even come with fillings of different flavors in between those hard layers: Cream, chocolate, strawberry, you name it, you got it. I am sure most of us would have eaten them at least once in our lives. For those who haven’t, meet the biscuit.

Biscuits come in all shapes, sizes and colours, though they usually come bite-size or slightly larger. They are typically dry, hard, and crunchy (there are some crumbly variants). More importantly, their fillings usually come in between biscuit layers – or wafers – which sets them apart from their American counterparts. We’ll explore why this is so in the next section.

(FYI, the word “cookie” is not often used by the British until recently)

The Americans – Cookie “da Rebel”

To the Americans, the need to distinguish themselves from their former colonial masters was great, so great that they decided to do many drastic things to distinguish their culture from their “brothers-in-arms”. Apart from the numerous changes to their spelling system (color vs colour, center vs centre, vaporize vs vapourise), they also decided to break away from the traditional idea of “biscuits” and re-invented the snack. It is now revived with a new style and name, and it is called the cookie.

While most people will go “wait a minute, the cookie and the biscuit are the same thing”, there are actually a couple of subtle differences in the style of presentation and taste of these cookies as compared to their Old-World relatives. For one thing, the Americans decided to make them bigger, rounder, and slightly softer (though softness is subjective, depending on the baking style). More importantly, note how the fillings have been added to the pastry. Unlike the biscuit wafer-style fillings, Americans decided to split their substance into little chunks and embed them throughout the dough, and presto – the chocolate chip cookie is born! Try typing the word “biscuit” into Google’s image search, and compare them to search results for the word “cookie”. You’ll understand the difference.

So where did the biscuit go?

But of course, the Americans pulled no stops to distancing themselves from their former masters. In a bid to throw the biscuit entirely out of the window, they decided that it should be used to name a small leavened bread instead (thankfully they didn’t turn the word into a taboo). If you want a taste of a typical American biscuit here in Singapore, I recommend you check out Popeyes’ biscuits. They taste good, and are damn filling.

The Gasoline-Petroleum Issue

Cookies and biscuits ain’t the only things the Yanks and the English have issues about. They also decided to name the fuel they use differently too. In Europe, people top up their cars and other vehicles with petroleum, but in the States, they fill their tanks with gasoline (or gas for short). Hahaha… it’s pretty amusing now that we think about it, why they decide to use different names even though both sides speak the same language.

Metric vs Imperial

That’s not all. While the British have moved on and started using the new metric system of units, the Americans seem to have taken one step “backwards” and retained the usage of the Imperial units system – although they decided it should be renamed as the “United States Customary System”. This is a peculiarity that I never really got an explanation for, and is still going quite strong today. Whether it is out of usefulness, laziness to change, or sheer pride and refusal to accept the metric system, I guess this is an exploration I will look into soon. =)

Conclusion

It’s really amusing to explore the other little nuances that separate the Americans from the British. The ones I’ve listed are just a few of the many differences between them. I wonder what others I can find in time to come…

Food is never simple. Take what is known as a cookie in America and a biscuit in the United Kingdom—two small, usually sweet treat concepts that sometimes overlap and sometimes don’t. However humble, these foods are inextricably tied to gigantic ideas in the history of both countries: the expansion of empire, the Industrial Revolution, waves of immigration, slavery, labor, nationalism. It’s honestly not that insane to say that the cookie/biscuit, if you include its predecessors, is one of the most important foods in human history.

The forebears of the cookie/biscuit are some of the earliest prepared foods in the world. At its core, this is a paste of some sort of flour and some sort of liquid, spread fairly flat and cooked until it dries. Essentially every culture had some version of this, made with whatever flour they could grow and process. Such items were portable, long-lasting sources of calories. Ground millet, sorghum, peas, and, eventually, wheat have been used for these hard, flat crackers, which were then rehydrated when it came time to eat. Usually, they were baked twice: once to cook them, at a relatively high heat, and then again for longer at lower heat to fully dry them out. Probably the earliest example is bappir, a Sumerian bread that dates back to around the third millennium B.C., and which was made of barley and wheat. Interestingly, it wasn’t actually eaten, but used as a sort of shelf-stable beer starter. That would change, though.

Then there’s baati, from northern India, which is a hard, round, unleavened biscuit, likely very ancient, commonly served with lentils. Greek shepherds soaked their paximadia, made of barley, in water and olive oil. It’s clear that this kind of foodstuff has a near-universal and very old history. That said, recipes and even helpful descriptions of early biscuits are hard to find. This was the food of the poor, generally, and for most of recorded history, those who wrote had little interest in documenting anything to do with the poor. “The early history of biscuits is largely unwritten,” says Annie Gray, a British food historian. “We know they’re there, we know people must have been eating them, but we don’t actually know what they were made of, or how they were used, or whether they were being baked at home or bought from bakers.”

This sort of food quickly became associated with the military, as the original MREs. Soldiers could carry biscuits for long periods of time, and either eat them as-is (not very pleasant) or soften them in water or whatever soups, wines, beers, or other liquid they had around. Biscuits like these aren’t especially nutritious when made from wheat, but they are filling and contain calories, and their virtue lay more in stability than anything else.

In English these biscuits eventually became known as “hardtack” when used in a military or exploration setting. But the more common name in many European countries was derived from the Latin bis coctus, or “twice-baked.” That’s where we get both “biscuit” and “biscotti.” The name, it turns out, is more figurative than it sounds: British military hardtack was baked four times, and modern British biscuits are only baked once.

There’s a parallel evolution of the biscuit starting sometime before the seventh century. Sugar processing, developed first in India, from sugarcane, quickly made its way to the Abbasid Caliphate, which would eventually be centered in Baghdad. It was then, in what’s sometimes called the Golden Age of Islam, that biscuits would first be sweetened with sugar. And it made all the difference.

There were plenty of sweeteners around the world before sugar. In continental Europe and England, the preferred sweetener was honey, and that did not lend itself to biscuits. “Honey is hygroscopic, which means that a dough sweetened with it attracts water,” writes Lizzie Collingham in her excellent book, The Biscuit: The History of a Very British Indulgence. “Thus biscuits sweetened with honey quickly become soft, defeating the object of making them in the first place.” So in England, biscuits remained plain and unsweetened, made of wheat in the south and oats in the north, for centuries. Meanwhile over in Baghdad, sugar was being used in all kinds of foods. The sweet biscuits were often shaped like rings, just like military ones, which were easy to string together and carry on long journeys.

Sugar slowly leaked westward into Europe, and there are records of it in small amounts—for the very wealthy—in the Medieval period. It wasn’t until 1641 that the English finally figured out a way to get lots of it to their country. That’s when the English established sugarcane plantations in Barbados, which had a similar climate to the South Pacific, where it was first domesticated. From these plantations, worked by enslaved people, sugar finally flowed into England. The island long played a prominent role in the slave trade.

Prior to that, biscuits in England were still common as an economical, long-lasting food for the poor, though no real recipes for civilian biscuits from this era exist. Gray says that they were likely the predecessors of what we now know as water crackers or water biscuits. Military hardtack, meanwhile, had evolved into one of the most hated foodstuffs in the British Empire, and for good reason.

The British hardtack industry was woefully behind that of other European powers. Spain and Portugal both had sophisticated biscuit bakery infrastructures for their navies and explorers, contracting with private bakers and providing them to explorers and traders. England was a few decades late to the world-spanning maritime travel than the Spanish and Portuguese, and their biscuits couldn’t have helped matters.

In England, corners were cut whenever possible. One of the most famous examples is in the nickname “limey,” which comes from the fact that the English navy eventually swapped the standard scurvy treatment, lemons, for the less expensive limes, which were grown in the British colonies. (Limes, it turns out, have significantly less vitamin C than lemons, and scurvy quickly became a problem again.) This frugality extended to biscuits. The flour was the lowest possible quality at best, and accusations flew that it was adulterated with chalk and even less savory, non-food materials. English hardtack became notorious for softening on voyages, whereupon weevil maggots would crawl out. By the mid-1700s, British biscuits were shitty enough that it was becoming a legitimate problem of national security. Sailors were weak and dying because their main food was spoiling. Soft biscuits became indelibly tied with weevils, death, and unclean conditions.

By the time the British started fighting Napoleon, the navy had cracked down and created massive biscuit-making factories with the benefit of new steam technology. They were, writes Collingham, one of the first industrially produced products in the world.

While the military was figuring out how to make hardtack in non-disgusting ways, other huge changes were happening in England. Tea was making inroads in the 1660s, along with a civil war, the beheading of the king, a plague, and repeated wars with the Dutch. Moving into the 1700s, the first sparks of the Industrial Revolution began siphoning workers from the fields to the factories. Perhaps more importantly to this discussion, the actual time of day workers ate began to change. Prior to this time, the largest meal of the day in England was around noon or a little later, at the midway point of the workday. But then, with workers farther away from home and with the availability of sunlight less important to work, this meal moved later and later, eventually settling in at around 6:00 p.m., when workers could have a real home-cooked meal. The upper classes, too, had less work than ever to do, and more nighttime entertainment in the rapidly growing cities, so they ate much later as well.

But there was a problem: Lunch hadn’t been invented yet. This is where tea comes into play, and with it, the biscuit. Tea and biscuits were an early pairing for the working classes. A biscuit, as it has always been, is a good source of cheap, reliable fuel. Mid-day tea became common, until it, too, moved later into the afternoon, pushed by the actual meal that became lunch. This is also the great era of nationalism, when polities around the world decided they should be countries with proper borders and a shared language and a ruler and flag, rather than some kind of loose cultural and geographic blob under a king. Tea, which couldn’t have been any less English, given where it actually grows (with India and China topping the list), became a major national symbol. It was almost a boast of the power of the Empire, to make your national drink something that is grown thousands of miles away. And the biscuit was always there, tea’s partner.

From this point the British biscuit evolves from something purely utilitarian into something more and more luxurious, with more sugar, cut in increasingly delicate and intricate ways, flavored with chocolate and spices. Biscuit companies then were almost like tech companies now: They’d announce a new biscuit, which was rarely all that different from an older biscuit, and market it aggressively. They competed mercilessly for market share. Britain had transitioned from having the world’s worst biscuits to having its best (at least by British standards).

In the United States, things were … different. By the time the country had a big, far-flung empire of its own, there were better solutions to the problem of spoilage-free naval food than biscuits, namely stuff in cans. (Though military MREs do often contain a cracker of some sort, even today.) Even the word “biscuit,” which in the United Kingdom is applied to any hard, thin, bread-like product, was gone, thanks to the American penchant for studiously throwing Britishisms in the garbage.

Hardtack was still common in the American military and fishing realms. In New England, it was sometimes called “sea biscuit” or “pilot bread,” and it was there that a slightly better version of hardtack was created. A baker in Newburyport, Massachusetts, named John Pearson created a thinner biscuit named the Crown Pilot cracker. This was the first major American cracker. It was like a hardtack biscuit, but thinner and more delicate, while still keeping a long life. Pearson’s bakery would be swallowed up by a new conglomeration of independent bakeries. By 1898 it was called the National Biscuit Company, later abbreviated to Nabisco.

The term “cookie” comes from a totally different root, both culinarily and etymologically, than the British biscuit. It’s not really accurate to say that “biscuit” is the British word for “cookie” or vice versa, as there are multiple different ancestries at play here. The word “cookie” comes from the Dutch koek, meaning “cake.” Dutch also has a diminutive: koekje, or “little cake.” With the major influence of the Dutch in New Amsterdam, it was the Dutch word that was Americanized into “cookie.”

American cookies vary pretty dramatically. An Oreo is crisp and sandwiched, while a Toll House–style chocolate chip cookie is gooey and soft. American cookie culture evolved quickly thanks to new technology: electric mixers, widely available leavening agents, easy access to formerly expensive spices and add-ins like chocolate.

One major difference, though, is that Americans didn’t have a long and sometimes maggot-infested history with biscuits. By the time America was America, the biscuit was already established as a treat rather than a survival tool. Hardtack has a history in the United States, too, especially around the Civil War. But it was never really connected with sweet treats by evolution or happenstance, unlike in Britain. The new cookie tradition was simply dessert.

We should probably mention the American biscuit here, which is usually associated with the American Southeast. It’s totally unlike either a cookie or a British biscuit, being instead a soft quick bread. Quick breads, which include Irish soda bread and cornbread, are yeast-less breads that use a leavening agent such as baking powder. They arose due to the high price of yeast. How the term “biscuit” became applied to a soft quick bread that is only ever baked once—that’s a mystery. Somehow the word for one bread product eventually became applied to another, despite them having little in common.

Back to cookies! If there’s a thing to distinguish the American cookie from the British biscuit, it’s the idea that a biscuit always needs to be crisp. This comes from the hardtack tradition, where if a biscuit was soft, it had gone bad. This remains true today; as an American watching The Great British Bake-Off (The Great British Baking Show in America, for some reason), judge Paul Hollywood’s obsession with a biscuit’s “snap” seems weirdly fussy. From an American perspective, some cookies snap and some don’t, but that certainly can’t be applied as a general rule. “I don’t disagree with him that a biscuit should snap,” says Gray. “A soggy biscuit is a stale biscuit; if it’s gone a bit soft, you know it’s not fresh. So I think there are a lot of cues about goodness and freshness with the snap.” That’s hardly a standard that makes any sense with an oatmeal raisin cookie. Some cookies are crisp, because that’s nice. Some are gooey, because that’s nice, too.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.

November 21, 2012 · 10:42 am

Broadly, I’d say in the UK we use the word “biscuit” in the sense that the word “cookie” is used in the US. For us Brits it means, generally, a small, flat (ish), sweet baked good that’s hard and rigid. Something you’d nibble and dunk in a cup of tea. They can be round or square or rectangular. They aren’t made with yeast, but could be made with chemical raising agents such as baking powder or bicarbonate of soda.

We do also use the word “cookie” in the UK, but I tend to use them fairly synonymously.

Which probably isn’t very helpful, as, for reasons revealed by a spot of etymology, they are technically somewhat different.

The word biscuit is from the 14th century Old French word bescuit. It literally means “twice-cooked”, or twice-baked and derives from bes bis + cuire to cook, from Latin coquere. The Italian word biscotti has an identical meaning. And indeed, the classic biscotti, the hard slices that you dunk in a digestivo or coffee – biscotti di prato, cantucci, cantuccini and tozzetti – are the best example of this process, as you bake the dough in a loaf form. You bake the dough in a loaf form first, then slice it, then bake the slices to crisp them up.

The word cookie on the other hand derives from the Dutch koek, meaning cake, in a diminutive form: “little cake”. Cookies are more technically, therefore, derived from a more cake-like dough or batter, often dropped in spoonfuls on a baking sheet, not manually moulded like a firmer biscuit dough.

Anyway, I’m going to keep my biscuits and cookies in the same category. But I will put crackers – basically savoury biscuits – in a separate category.