«Language processing» redirects here. For the processing of language by computers, see Natural language processing.

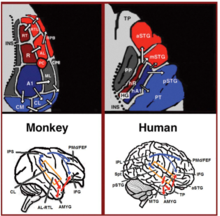

Dual stream connectivity between the auditory cortex and frontal lobe of monkeys and humans. Top: The auditory cortex of the monkey (left) and human (right) is schematically depicted on the supratemporal plane and observed from above (with the parieto- frontal operculi removed). Bottom: The brain of the monkey (left) and human (right) is schematically depicted and displayed from the side. Orange frames mark the region of the auditory cortex, which is displayed in the top sub-figures. Top and Bottom: Blue colors mark regions affiliated with the ADS, and red colors mark regions affiliated with the AVS (dark red and blue regions mark the primary auditory fields). Material was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

In psycholinguistics, language processing refers to the way humans use words to communicate ideas and feelings, and how such communications are processed and understood. Language processing is considered to be a uniquely human ability that is not produced with the same grammatical understanding or systematicity in even human’s closest primate relatives.[1]

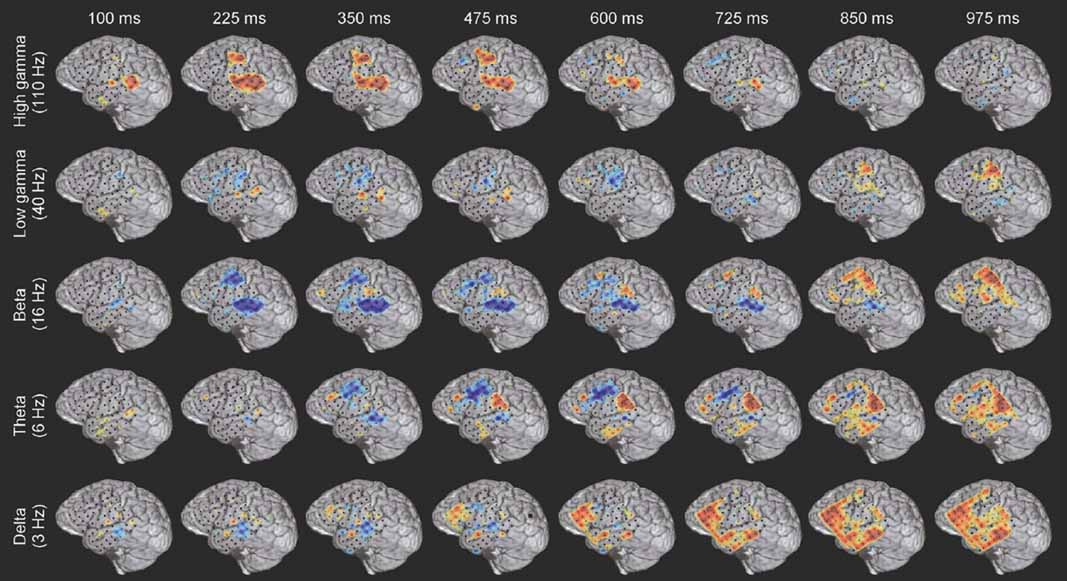

Throughout the 20th century the dominant model[2] for language processing in the brain was the Geschwind-Lichteim-Wernicke model, which is based primarily on the analysis of brain-damaged patients. However, due to improvements in intra-cortical electrophysiological recordings of monkey and human brains, as well non-invasive techniques such as fMRI, PET, MEG and EEG, a dual auditory pathway[3][4] has been revealed and a two-streams model has been developed. In accordance with this model, there are two pathways that connect the auditory cortex to the frontal lobe, each pathway accounting for different linguistic roles. The auditory ventral stream pathway is responsible for sound recognition, and is accordingly known as the auditory ‘what’ pathway. The auditory dorsal stream in both humans and non-human primates is responsible for sound localization, and is accordingly known as the auditory ‘where’ pathway. In humans, this pathway (especially in the left hemisphere) is also responsible for speech production, speech repetition, lip-reading, and phonological working memory and long-term memory. In accordance with the ‘from where to what’ model of language evolution,[5][6] the reason the ADS is characterized with such a broad range of functions is that each indicates a different stage in language evolution.

The division of the two streams first occurs in the auditory nerve where the anterior branch enters the anterior cochlear nucleus in the brainstem which gives rise to the auditory ventral stream. The posterior branch enters the dorsal and posteroventral cochlear nucleus to give rise to the auditory dorsal stream.[7]: 8

Language processing can also occur in relation to signed languages or written content.

Early neurolinguistics models[edit]

Throughout the 20th century, our knowledge of language processing in the brain was dominated by the Wernicke-Lichtheim-Geschwind model.[8][2][9] The Wernicke-Lichtheim-Geschwind model is primarily based on research conducted on brain-damaged individuals who were reported to possess a variety of language related disorders. In accordance with this model, words are perceived via a specialized word reception center (Wernicke’s area) that is located in the left temporoparietal junction. This region then projects to a word production center (Broca’s area) that is located in the left inferior frontal gyrus. Because almost all language input was thought to funnel via Wernicke’s area and all language output to funnel via Broca’s area, it became extremely difficult to identify the basic properties of each region. This lack of clear definition for the contribution of Wernicke’s and Broca’s regions to human language rendered it extremely difficult to identify their homologues in other primates.[10] With the advent of the fMRI and its application for lesion mappings, however, it was shown that this model is based on incorrect correlations between symptoms and lesions.[11][12][13][14][15][16][17] The refutation of such an influential and dominant model opened the door to new models of language processing in the brain.

Current neurolinguistics models[edit]

Anatomy[edit]

In the last two decades, significant advances occurred in our understanding of the neural processing of sounds in primates. Initially by recording of neural activity in the auditory cortices of monkeys[18][19] and later elaborated via histological staining[20][21][22] and fMRI scanning studies,[23] 3 auditory fields were identified in the primary auditory cortex, and 9 associative auditory fields were shown to surround them (Figure 1 top left). Anatomical tracing and lesion studies further indicated of a separation between the anterior and posterior auditory fields, with the anterior primary auditory fields (areas R-RT) projecting to the anterior associative auditory fields (areas AL-RTL), and the posterior primary auditory field (area A1) projecting to the posterior associative auditory fields (areas CL-CM).[20][24][25][26] Recently, evidence accumulated that indicates homology between the human and monkey auditory fields. In humans, histological staining studies revealed two separate auditory fields in the primary auditory region of Heschl’s gyrus,[27][28] and by mapping the tonotopic organization of the human primary auditory fields with high resolution fMRI and comparing it to the tonotopic organization of the monkey primary auditory fields, homology was established between the human anterior primary auditory field and monkey area R (denoted in humans as area hR) and the human posterior primary auditory field and the monkey area A1 (denoted in humans as area hA1).[29][30][31][32][33] Intra-cortical recordings from the human auditory cortex further demonstrated similar patterns of connectivity to the auditory cortex of the monkey. Recording from the surface of the auditory cortex (supra-temporal plane) reported that the anterior Heschl’s gyrus (area hR) projects primarily to the middle-anterior superior temporal gyrus (mSTG-aSTG) and the posterior Heschl’s gyrus (area hA1) projects primarily to the posterior superior temporal gyrus (pSTG) and the planum temporale (area PT; Figure 1 top right).[34][35] Consistent with connections from area hR to the aSTG and hA1 to the pSTG is an fMRI study of a patient with impaired sound recognition (auditory agnosia), who was shown with reduced bilateral activation in areas hR and aSTG but with spared activation in the mSTG-pSTG.[36] This connectivity pattern is also corroborated by a study that recorded activation from the lateral surface of the auditory cortex and reported of simultaneous non-overlapping activation clusters in the pSTG and mSTG-aSTG while listening to sounds.[37]

Downstream to the auditory cortex, anatomical tracing studies in monkeys delineated projections from the anterior associative auditory fields (areas AL-RTL) to ventral prefrontal and premotor cortices in the inferior frontal gyrus (IFG)[38][39] and amygdala.[40] Cortical recording and functional imaging studies in macaque monkeys further elaborated on this processing stream by showing that acoustic information flows from the anterior auditory cortex to the temporal pole (TP) and then to the IFG.[41][42][43][44][45][46] This pathway is commonly referred to as the auditory ventral stream (AVS; Figure 1, bottom left-red arrows). In contrast to the anterior auditory fields, tracing studies reported that the posterior auditory fields (areas CL-CM) project primarily to dorsolateral prefrontal and premotor cortices (although some projections do terminate in the IFG.[47][39] Cortical recordings and anatomical tracing studies in monkeys further provided evidence that this processing stream flows from the posterior auditory fields to the frontal lobe via a relay station in the intra-parietal sulcus (IPS).[48][49][50][51][52][53] This pathway is commonly referred to as the auditory dorsal stream (ADS; Figure 1, bottom left-blue arrows). Comparing the white matter pathways involved in communication in humans and monkeys with diffusion tensor imaging techniques indicates of similar connections of the AVS and ADS in the two species (Monkey,[52] Human[54][55][56][57][58][59]). In humans, the pSTG was shown to project to the parietal lobe (sylvian parietal-temporal junction-inferior parietal lobule; Spt-IPL), and from there to dorsolateral prefrontal and premotor cortices (Figure 1, bottom right-blue arrows), and the aSTG was shown to project to the anterior temporal lobe (middle temporal gyrus-temporal pole; MTG-TP) and from there to the IFG (Figure 1 bottom right-red arrows).

Auditory ventral stream[edit]

The auditory ventral stream (AVS) connects the auditory cortex with the middle temporal gyrus and temporal pole, which in turn connects with the inferior frontal gyrus. This pathway is responsible for sound recognition, and is accordingly known as the auditory ‘what’ pathway. The functions of the AVS include the following.

Sound recognition[edit]

Accumulative converging evidence indicates that the AVS is involved in recognizing auditory objects. At the level of the primary auditory cortex, recordings from monkeys showed higher percentage of neurons selective for learned melodic sequences in area R than area A1,[60] and a study in humans demonstrated more selectivity for heard syllables in the anterior Heschl’s gyrus (area hR) than posterior Heschl’s gyrus (area hA1).[61] In downstream associative auditory fields, studies from both monkeys and humans reported that the border between the anterior and posterior auditory fields (Figure 1-area PC in the monkey and mSTG in the human) processes pitch attributes that are necessary for the recognition of auditory objects.[18] The anterior auditory fields of monkeys were also demonstrated with selectivity for con-specific vocalizations with intra-cortical recordings.[41][19][62] and functional imaging[63][42][43] One fMRI monkey study further demonstrated a role of the aSTG in the recognition of individual voices.[42] The role of the human mSTG-aSTG in sound recognition was demonstrated via functional imaging studies that correlated activity in this region with isolation of auditory objects from background noise,[64][65] and with the recognition of spoken words,[66][67][68][69][70][71][72] voices,[73] melodies,[74][75] environmental sounds,[76][77][78] and non-speech communicative sounds.[79] A meta-analysis of fMRI studies[80] further demonstrated functional dissociation between the left mSTG and aSTG, with the former processing short speech units (phonemes) and the latter processing longer units (e.g., words, environmental sounds). A study that recorded neural activity directly from the left pSTG and aSTG reported that the aSTG, but not pSTG, was more active when the patient listened to speech in her native language than unfamiliar foreign language.[81] Consistently, electro stimulation to the aSTG of this patient resulted in impaired speech perception[81] (see also[82][83] for similar results). Intra-cortical recordings from the right and left aSTG further demonstrated that speech is processed laterally to music.[81] An fMRI study of a patient with impaired sound recognition (auditory agnosia) due to brainstem damage was also shown with reduced activation in areas hR and aSTG of both hemispheres when hearing spoken words and environmental sounds.[36] Recordings from the anterior auditory cortex of monkeys while maintaining learned sounds in working memory,[46] and the debilitating effect of induced lesions to this region on working memory recall,[84][85][86] further implicate the AVS in maintaining the perceived auditory objects in working memory. In humans, area mSTG-aSTG was also reported active during rehearsal of heard syllables with MEG.[87] and fMRI[88] The latter study further demonstrated that working memory in the AVS is for the acoustic properties of spoken words and that it is independent to working memory in the ADS, which mediates inner speech. Working memory studies in monkeys also suggest that in monkeys, in contrast to humans, the AVS is the dominant working memory store.[89]

In humans, downstream to the aSTG, the MTG and TP are thought to constitute the semantic lexicon, which is a long-term memory repository of audio-visual representations that are interconnected on the basis of semantic relationships. (See also the reviews by[3][4] discussing this topic). The primary evidence for this role of the MTG-TP is that patients with damage to this region (e.g., patients with semantic dementia or herpes simplex virus encephalitis) are reported[90][91] with an impaired ability to describe visual and auditory objects and a tendency to commit semantic errors when naming objects (i.e., semantic paraphasia). Semantic paraphasias were also expressed by aphasic patients with left MTG-TP damage[14][92] and were shown to occur in non-aphasic patients after electro-stimulation to this region.[93][83] or the underlying white matter pathway[94] Two meta-analyses of the fMRI literature also reported that the anterior MTG and TP were consistently active during semantic analysis of speech and text;[66][95] and an intra-cortical recording study correlated neural discharge in the MTG with the comprehension of intelligible sentences.[96]

Sentence comprehension[edit]

In addition to extracting meaning from sounds, the MTG-TP region of the AVS appears to have a role in sentence comprehension, possibly by merging concepts together (e.g., merging the concept ‘blue’ and ‘shirt’ to create the concept of a ‘blue shirt’). The role of the MTG in extracting meaning from sentences has been demonstrated in functional imaging studies reporting stronger activation in the anterior MTG when proper sentences are contrasted with lists of words, sentences in a foreign or nonsense language, scrambled sentences, sentences with semantic or syntactic violations and sentence-like sequences of environmental sounds.[97][98][99][100][101][102][103][104] One fMRI study[105] in which participants were instructed to read a story further correlated activity in the anterior MTG with the amount of semantic and syntactic content each sentence contained. An EEG study[106] that contrasted cortical activity while reading sentences with and without syntactic violations in healthy participants and patients with MTG-TP damage, concluded that the MTG-TP in both hemispheres participate in the automatic (rule based) stage of syntactic analysis (ELAN component), and that the left MTG-TP is also involved in a later controlled stage of syntax analysis (P600 component). Patients with damage to the MTG-TP region have also been reported with impaired sentence comprehension.[14][107][108] See review[109] for more information on this topic.

Bilaterality[edit]

In contradiction to the Wernicke-Lichtheim-Geschwind model that implicates sound recognition to occur solely in the left hemisphere, studies that examined the properties of the right or left hemisphere in isolation via unilateral hemispheric anesthesia (i.e., the WADA procedure[110]) or intra-cortical recordings from each hemisphere[96] provided evidence that sound recognition is processed bilaterally. Moreover, a study that instructed patients with disconnected hemispheres (i.e., split-brain patients) to match spoken words to written words presented to the right or left hemifields, reported vocabulary in the right hemisphere that almost matches in size with the left hemisphere[111] (The right hemisphere vocabulary was equivalent to the vocabulary of a healthy 11-years old child). This bilateral recognition of sounds is also consistent with the finding that unilateral lesion to the auditory cortex rarely results in deficit to auditory comprehension (i.e., auditory agnosia), whereas a second lesion to the remaining hemisphere (which could occur years later) does.[112][113] Finally, as mentioned earlier, an fMRI scan of an auditory agnosia patient demonstrated bilateral reduced activation in the anterior auditory cortices,[36] and bilateral electro-stimulation to these regions in both hemispheres resulted with impaired speech recognition.[81]

Auditory dorsal stream[edit]

The auditory dorsal stream connects the auditory cortex with the parietal lobe, which in turn connects with inferior frontal gyrus. In both humans and non-human primates, the auditory dorsal stream is responsible for sound localization, and is accordingly known as the auditory ‘where’ pathway. In humans, this pathway (especially in the left hemisphere) is also responsible for speech production, speech repetition, lip-reading, and phonological working memory and long-term memory.

Speech production[edit]

Studies of present-day humans have demonstrated a role for the ADS in speech production, particularly in the vocal expression of the names of objects. For instance, in a series of studies in which sub-cortical fibers were directly stimulated[94] interference in the left pSTG and IPL resulted in errors during object-naming tasks, and interference in the left IFG resulted in speech arrest. Magnetic interference in the pSTG and IFG of healthy participants also produced speech errors and speech arrest, respectively[114][115] One study has also reported that electrical stimulation of the left IPL caused patients to believe that they had spoken when they had not and that IFG stimulation caused patients to unconsciously move their lips.[116] The contribution of the ADS to the process of articulating the names of objects could be dependent on the reception of afferents from the semantic lexicon of the AVS, as an intra-cortical recording study reported of activation in the posterior MTG prior to activation in the Spt-IPL region when patients named objects in pictures[117] Intra-cortical electrical stimulation studies also reported that electrical interference to the posterior MTG was correlated with impaired object naming[118][82]

Vocal mimicry[edit]

Although sound perception is primarily ascribed with the AVS, the ADS appears associated with several aspects of speech perception. For instance, in a meta-analysis of fMRI studies[119] (Turkeltaub and Coslett, 2010), in which the auditory perception of phonemes was contrasted with closely matching sounds, and the studies were rated for the required level of attention, the authors concluded that attention to phonemes correlates with strong activation in the pSTG-pSTS region. An intra-cortical recording study in which participants were instructed to identify syllables also correlated the hearing of each syllable with its own activation pattern in the pSTG.[120] The involvement of the ADS in both speech perception and production has been further illuminated in several pioneering functional imaging studies that contrasted speech perception with overt or covert speech production.[121][122][123] These studies demonstrated that the pSTS is active only during the perception of speech, whereas area Spt is active during both the perception and production of speech. The authors concluded that the pSTS projects to area Spt, which converts the auditory input into articulatory movements.[124][125] Similar results have been obtained in a study in which participants’ temporal and parietal lobes were electrically stimulated. This study reported that electrically stimulating the pSTG region interferes with sentence comprehension and that stimulation of the IPL interferes with the ability to vocalize the names of objects.[83] The authors also reported that stimulation in area Spt and the inferior IPL induced interference during both object-naming and speech-comprehension tasks. The role of the ADS in speech repetition is also congruent with the results of the other functional imaging studies that have localized activation during speech repetition tasks to ADS regions.[126][127][128] An intra-cortical recording study that recorded activity throughout most of the temporal, parietal and frontal lobes also reported activation in the pSTG, Spt, IPL and IFG when speech repetition is contrasted with speech perception.[129] Neuropsychological studies have also found that individuals with speech repetition deficits but preserved auditory comprehension (i.e., conduction aphasia) suffer from circumscribed damage to the Spt-IPL area[130][131][132][133][134][135][136] or damage to the projections that emanate from this area and target the frontal lobe[137][138][139][140] Studies have also reported a transient speech repetition deficit in patients after direct intra-cortical electrical stimulation to this same region.[11][141][142] Insight into the purpose of speech repetition in the ADS is provided by longitudinal studies of children that correlated the learning of foreign vocabulary with the ability to repeat nonsense words.[143][144]

Speech monitoring[edit]

In addition to repeating and producing speech, the ADS appears to have a role in monitoring the quality of the speech output. Neuroanatomical evidence suggests that the ADS is equipped with descending connections from the IFG to the pSTG that relay information about motor activity (i.e., corollary discharges) in the vocal apparatus (mouth, tongue, vocal folds). This feedback marks the sound perceived during speech production as self-produced and can be used to adjust the vocal apparatus to increase the similarity between the perceived and emitted calls. Evidence for descending connections from the IFG to the pSTG has been offered by a study that electrically stimulated the IFG during surgical operations and reported the spread of activation to the pSTG-pSTS-Spt region[145] A study[146] that compared the ability of aphasic patients with frontal, parietal or temporal lobe damage to quickly and repeatedly articulate a string of syllables reported that damage to the frontal lobe interfered with the articulation of both identical syllabic strings («Bababa») and non-identical syllabic strings («Badaga»), whereas patients with temporal or parietal lobe damage only exhibited impairment when articulating non-identical syllabic strings. Because the patients with temporal and parietal lobe damage were capable of repeating the syllabic string in the first task, their speech perception and production appears to be relatively preserved, and their deficit in the second task is therefore due to impaired monitoring. Demonstrating the role of the descending ADS connections in monitoring emitted calls, an fMRI study instructed participants to speak under normal conditions or when hearing a modified version of their own voice (delayed first formant) and reported that hearing a distorted version of one’s own voice results in increased activation in the pSTG.[147] Further demonstrating that the ADS facilitates motor feedback during mimicry is an intra-cortical recording study that contrasted speech perception and repetition.[129] The authors reported that, in addition to activation in the IPL and IFG, speech repetition is characterized by stronger activation in the pSTG than during speech perception.

Integration of phonemes with lip-movements[edit]

Although sound perception is primarily ascribed with the AVS, the ADS appears associated with several aspects of speech perception. For instance, in a meta-analysis of fMRI studies[119] in which the auditory perception of phonemes was contrasted with closely matching sounds, and the studies were rated for the required level of attention, the authors concluded that attention to phonemes correlates with strong activation in the pSTG-pSTS region. An intra-cortical recording study in which participants were instructed to identify syllables also correlated the hearing of each syllable with its own activation pattern in the pSTG.[148] Consistent with the role of the ADS in discriminating phonemes,[119] studies have ascribed the integration of phonemes and their corresponding lip movements (i.e., visemes) to the pSTS of the ADS. For example, an fMRI study[149] has correlated activation in the pSTS with the McGurk illusion (in which hearing the syllable «ba» while seeing the viseme «ga» results in the perception of the syllable «da»). Another study has found that using magnetic stimulation to interfere with processing in this area further disrupts the McGurk illusion.[150] The association of the pSTS with the audio-visual integration of speech has also been demonstrated in a study that presented participants with pictures of faces and spoken words of varying quality. The study reported that the pSTS selects for the combined increase of the clarity of faces and spoken words.[151] Corroborating evidence has been provided by an fMRI study[152] that contrasted the perception of audio-visual speech with audio-visual non-speech (pictures and sounds of tools). This study reported the detection of speech-selective compartments in the pSTS. In addition, an fMRI study[153] that contrasted congruent audio-visual speech with incongruent speech (pictures of still faces) reported pSTS activation. For a review presenting additional converging evidence regarding the role of the pSTS and ADS in phoneme-viseme integration see.[154]

Phonological long-term memory[edit]

A growing body of evidence indicates that humans, in addition to having a long-term store for word meanings located in the MTG-TP of the AVS (i.e., the semantic lexicon), also have a long-term store for the names of objects located in the Spt-IPL region of the ADS (i.e., the phonological lexicon). For example, a study[155][156] examining patients with damage to the AVS (MTG damage) or damage to the ADS (IPL damage) reported that MTG damage results in individuals incorrectly identifying objects (e.g., calling a «goat» a «sheep,» an example of semantic paraphasia). Conversely, IPL damage results in individuals correctly identifying the object but incorrectly pronouncing its name (e.g., saying «gof» instead of «goat,» an example of phonemic paraphasia). Semantic paraphasia errors have also been reported in patients receiving intra-cortical electrical stimulation of the AVS (MTG), and phonemic paraphasia errors have been reported in patients whose ADS (pSTG, Spt, and IPL) received intra-cortical electrical stimulation.[83][157][94] Further supporting the role of the ADS in object naming is an MEG study that localized activity in the IPL during the learning and during the recall of object names.[158] A study that induced magnetic interference in participants’ IPL while they answered questions about an object reported that the participants were capable of answering questions regarding the object’s characteristics or perceptual attributes but were impaired when asked whether the word contained two or three syllables.[159] An MEG study has also correlated recovery from anomia (a disorder characterized by an impaired ability to name objects) with changes in IPL activation.[160] Further supporting the role of the IPL in encoding the sounds of words are studies reporting that, compared to monolinguals, bilinguals have greater cortical density in the IPL but not the MTG.[161][162] Because evidence shows that, in bilinguals, different phonological representations of the same word share the same semantic representation,[163] this increase in density in the IPL verifies the existence of the phonological lexicon: the semantic lexicon of bilinguals is expected to be similar in size to the semantic lexicon of monolinguals, whereas their phonological lexicon should be twice the size. Consistent with this finding, cortical density in the IPL of monolinguals also correlates with vocabulary size.[164][165] Notably, the functional dissociation of the AVS and ADS in object-naming tasks is supported by cumulative evidence from reading research showing that semantic errors are correlated with MTG impairment and phonemic errors with IPL impairment. Based on these associations, the semantic analysis of text has been linked to the inferior-temporal gyrus and MTG, and the phonological analysis of text has been linked to the pSTG-Spt- IPL[166][167][168]

Phonological working memory[edit]

Working memory is often treated as the temporary activation of the representations stored in long-term memory that are used for speech (phonological representations). This sharing of resources between working memory and speech is evident by the finding[169][170] that speaking during rehearsal results in a significant reduction in the number of items that can be recalled from working memory (articulatory suppression). The involvement of the phonological lexicon in working memory is also evidenced by the tendency of individuals to make more errors when recalling words from a recently learned list of phonologically similar words than from a list of phonologically dissimilar words (the phonological similarity effect).[169] Studies have also found that speech errors committed during reading are remarkably similar to speech errors made during the recall of recently learned, phonologically similar words from working memory.[171] Patients with IPL damage have also been observed to exhibit both speech production errors and impaired working memory[172][173][174][175] Finally, the view that verbal working memory is the result of temporarily activating phonological representations in the ADS is compatible with recent models describing working memory as the combination of maintaining representations in the mechanism of attention in parallel to temporarily activating representations in long-term memory.[170][176][177][178] It has been argued that the role of the ADS in the rehearsal of lists of words is the reason this pathway is active during sentence comprehension[179] For a review of the role of the ADS in working memory, see.[180]

The ‘from where to what’ model of language evolution hypotheses 7 stages of language evolution.

The evolution of language[edit]

The auditory dorsal stream also has non-language related functions, such as sound localization[181][182][183][184][185] and guidance of eye movements.[186][187] Recent studies also indicate a role of the ADS in localization of family/tribe members, as a study[188] that recorded from the cortex of an epileptic patient reported that the pSTG, but not aSTG, is selective for the presence of new speakers. An fMRI[189] study of fetuses at their third trimester also demonstrated that area Spt is more selective to female speech than pure tones, and a sub-section of Spt is selective to the speech of their mother in contrast to unfamiliar female voices.

It is presently unknown why so many functions are ascribed to the human ADS. An attempt to unify these functions under a single framework was conducted in the ‘From where to what’ model of language evolution[190][191] In accordance with this model, each function of the ADS indicates of a different intermediate phase in the evolution of language. The roles of sound localization and integration of sound location with voices and auditory objects is interpreted as evidence that the origin of speech is the exchange of contact calls (calls used to report location in cases of separation) between mothers and offspring. The role of the ADS in the perception and production of intonations is interpreted as evidence that speech began by modifying the contact calls with intonations, possibly for distinguishing alarm contact calls from safe contact calls. The role of the ADS in encoding the names of objects (phonological long-term memory) is interpreted as evidence of gradual transition from modifying calls with intonations to complete vocal control. The role of the ADS in the integration of lip movements with phonemes and in speech repetition is interpreted as evidence that spoken words were learned by infants mimicking their parents’ vocalizations, initially by imitating their lip movements. The role of the ADS in phonological working memory is interpreted as evidence that the words learned through mimicry remained active in the ADS even when not spoken. This resulted with individuals capable of rehearsing a list of vocalizations, which enabled the production of words with several syllables. Further developments in the ADS enabled the rehearsal of lists of words, which provided the infra-structure for communicating with sentences.

Sign language in the brain[edit]

Neuroscientific research has provided a scientific understanding of how sign language is processed in the brain. There are over 135 discrete sign languages around the world- making use of different accents formed by separate areas of a country.[192]

By resorting to lesion analyses and neuroimaging, neuroscientists have discovered that whether it be spoken or sign language, human brains process language in general, in a similar manner regarding which area of the brain is being used. [192]Lesion analyses are used to examine the consequences of damage to specific brain regions involved in language while neuroimaging explore regions that are engaged in the processing of language.[192]

Previous hypotheses have been made that damage to Broca’s area or Wernicke’s area does not affect sign language being perceived; however, it is not the case. Studies have shown that damage to these areas are similar in results in spoken language where sign errors are present and/or repeated. [192]In both types of languages, they are affected by damage to the left hemisphere of the brain rather than the right -usually dealing with the arts.

There are obvious patterns for utilizing and processing language. In sign language, Broca’s area is activated while processing sign language employs Wernicke’s area similar to that of spoken language [192]

There have been other hypotheses about the lateralization of the two hemispheres. Specifically, the right hemisphere was thought to contribute to the overall communication of a language globally whereas the left hemisphere would be dominant in generating the language locally.[193] Through research in aphasias, RHD signers were found to have a problem maintaining the spatial portion of their signs, confusing similar signs at different locations necessary to communicate with another properly.[193] LHD signers, on the other hand, had similar results to those of hearing patients. Furthermore, other studies have emphasized that sign language is present bilaterally but will need to continue researching to reach a conclusion.[193]

Writing in the brain[edit]

There is a comparatively small body of research on the neurology of reading and writing.[194] Most of the studies performed deal with reading rather than writing or spelling, and the majority of both kinds focus solely on the English language.[195] English orthography is less transparent than that of other languages using a Latin script.[194] Another difficulty is that some studies focus on spelling words of English and omit the few logographic characters found in the script.[194]

In terms of spelling, English words can be divided into three categories – regular, irregular, and “novel words” or “nonwords.” Regular words are those in which there is a regular, one-to-one correspondence between grapheme and phoneme in spelling. Irregular words are those in which no such correspondence exists. Nonwords are those that exhibit the expected orthography of regular words but do not carry meaning, such as nonce words and onomatopoeia.[194]

An issue in the cognitive and neurological study of reading and spelling in English is whether a single-route or dual-route model best describes how literate speakers are able to read and write all three categories of English words according to accepted standards of orthographic correctness. Single-route models posit that lexical memory is used to store all spellings of words for retrieval in a single process. Dual-route models posit that lexical memory is employed to process irregular and high-frequency regular words, while low-frequency regular words and nonwords are processed using a sub-lexical set of phonological rules.[194]

The single-route model for reading has found support in computer modelling studies, which suggest that readers identify words by their orthographic similarities to phonologically alike words.[194] However, cognitive and lesion studies lean towards the dual-route model. Cognitive spelling studies on children and adults suggest that spellers employ phonological rules in spelling regular words and nonwords, while lexical memory is accessed to spell irregular words and high-frequency words of all types.[194] Similarly, lesion studies indicate that lexical memory is used to store irregular words and certain regular words, while phonological rules are used to spell nonwords.[194]

More recently, neuroimaging studies using positron emission tomography and fMRI have suggested a balanced model in which the reading of all word types begins in the visual word form area, but subsequently branches off into different routes depending upon whether or not access to lexical memory or semantic information is needed (which would be expected with irregular words under a dual-route model).[194] A 2007 fMRI study found that subjects asked to produce regular words in a spelling task exhibited greater activation in the left posterior STG, an area used for phonological processing, while the spelling of irregular words produced greater activation of areas used for lexical memory and semantic processing, such as the left IFG and left SMG and both hemispheres of the MTG.[194] Spelling nonwords was found to access members of both pathways, such as the left STG and bilateral MTG and ITG.[194] Significantly, it was found that spelling induces activation in areas such as the left fusiform gyrus and left SMG that are also important in reading, suggesting that a similar pathway is used for both reading and writing.[194]

Far less information exists on the cognition and neurology of non-alphabetic and non-English scripts. Every language has a morphological and a phonological component, either of which can be recorded by a writing system. Scripts recording words and morphemes are considered logographic, while those recording phonological segments, such as syllabaries and alphabets, are phonographic.[195] Most systems combine the two and have both logographic and phonographic characters.[195]

In terms of complexity, writing systems can be characterized as “transparent” or “opaque” and as “shallow” or “deep.” A “transparent” system exhibits an obvious correspondence between grapheme and sound, while in an “opaque” system this relationship is less obvious. The terms “shallow” and “deep” refer to the extent that a system’s orthography represents morphemes as opposed to phonological segments.[195] Systems that record larger morphosyntactic or phonological segments, such as logographic systems and syllabaries put greater demand on the memory of users.[195] It would thus be expected that an opaque or deep writing system would put greater demand on areas of the brain used for lexical memory than would a system with transparent or shallow orthography.

See also[edit]

- Sign language

- Phonology

- Auditory processing disorder

- Brodmann area

- Cognitive science

- Developmental verbal dyspraxia

- FOXP2

- Language disorder

- Neurobiology

- Neurolinguistics

- Neuropsychology

- Neuroscience

- Origin of language

- Visual word form area

References[edit]

- ^ Seidenberg MS, Petitto LA (1987). «Communication, symbolic communication, and language: Comment on Savage-Rumbaugh, McDonald, Sevcik, Hopkins, and Rupert (1986)». Journal of Experimental Psychology: General. 116 (3): 279–287. doi:10.1037/0096-3445.116.3.279. S2CID 18329599.

- ^ a b Geschwind N (June 1965). «Disconnexion syndromes in animals and man. I». review. Brain. 88 (2): 237–94. doi:10.1093/brain/88.2.237. PMID 5318481.

- ^ a b Hickok G, Poeppel D (May 2007). «The cortical organization of speech processing». review. Nature Reviews. Neuroscience. 8 (5): 393–402. doi:10.1038/nrn2113. PMID 17431404. S2CID 6199399.

- ^ a b Gow DW (June 2012). «The cortical organization of lexical knowledge: a dual lexicon model of spoken language processing». review. Brain and Language. 121 (3): 273–88. doi:10.1016/j.bandl.2012.03.005. PMC 3348354. PMID 22498237.

- ^ Poliva O (2017-09-20). «From where to what: a neuroanatomically based evolutionary model of the emergence of speech in humans». review. F1000Research. 4: 67. doi:10.12688/f1000research.6175.3. PMC 5600004. PMID 28928931.

Material was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

- ^ Poliva O (2016). «From Mimicry to Language: A Neuroanatomically Based Evolutionary Model of the Emergence of Vocal Language». review. Frontiers in Neuroscience. 10: 307. doi:10.3389/fnins.2016.00307. PMC 4928493. PMID 27445676.

Material was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

- ^ Pickles JO (2015). «Chapter 1: Auditory pathways: anatomy and physiology». In Aminoff MJ, Boller F, Swaab DF (eds.). Handbook of Clinical Neurology. review. Vol. 129. pp. 3–25. doi:10.1016/B978-0-444-62630-1.00001-9. ISBN 978-0-444-62630-1. PMID 25726260.

- ^ Lichteim L (1885-01-01). «On Aphasia». Brain. 7 (4): 433–484. doi:10.1093/brain/7.4.433. hdl:11858/00-001M-0000-002C-5780-B.

- ^ Wernicke C (1974). Der aphasische Symptomenkomplex. Springer Berlin Heidelberg. pp. 1–70. ISBN 978-3-540-06905-8.

- ^ Aboitiz F, García VR (December 1997). «The evolutionary origin of the language areas in the human brain. A neuroanatomical perspective». Brain Research. Brain Research Reviews. 25 (3): 381–96. doi:10.1016/s0165-0173(97)00053-2. PMID 9495565. S2CID 20704891.

- ^ a b Anderson JM, Gilmore R, Roper S, Crosson B, Bauer RM, Nadeau S, Beversdorf DQ, Cibula J, Rogish M, Kortencamp S, Hughes JD, Gonzalez Rothi LJ, Heilman KM (October 1999). «Conduction aphasia and the arcuate fasciculus: A reexamination of the Wernicke-Geschwind model». Brain and Language. 70 (1): 1–12. doi:10.1006/brln.1999.2135. PMID 10534369. S2CID 12171982.

- ^ DeWitt I, Rauschecker JP (November 2013). «Wernicke’s area revisited: parallel streams and word processing». Brain and Language. 127 (2): 181–91. doi:10.1016/j.bandl.2013.09.014. PMC 4098851. PMID 24404576.

- ^ Dronkers NF (January 2000). «The pursuit of brain-language relationships». Brain and Language. 71 (1): 59–61. doi:10.1006/brln.1999.2212. PMID 10716807. S2CID 7224731.

- ^ a b c Dronkers NF, Wilkins DP, Van Valin RD, Redfern BB, Jaeger JJ (May 2004). «Lesion analysis of the brain areas involved in language comprehension». Cognition. 92 (1–2): 145–77. doi:10.1016/j.cognition.2003.11.002. hdl:11858/00-001M-0000-0012-6912-A. PMID 15037129. S2CID 10919645.

- ^ Mesulam MM, Thompson CK, Weintraub S, Rogalski EJ (August 2015). «The Wernicke conundrum and the anatomy of language comprehension in primary progressive aphasia». Brain. 138 (Pt 8): 2423–37. doi:10.1093/brain/awv154. PMC 4805066. PMID 26112340.

- ^ Poeppel D, Emmorey K, Hickok G, Pylkkänen L (October 2012). «Towards a new neurobiology of language». The Journal of Neuroscience. 32 (41): 14125–31. doi:10.1523/jneurosci.3244-12.2012. PMC 3495005. PMID 23055482.

- ^ Vignolo LA, Boccardi E, Caverni L (March 1986). «Unexpected CT-scan findings in global aphasia». Cortex; A Journal Devoted to the Study of the Nervous System and Behavior. 22 (1): 55–69. doi:10.1016/s0010-9452(86)80032-6. PMID 2423296. S2CID 4479679.

- ^ a b Bendor D, Wang X (August 2006). «Cortical representations of pitch in monkeys and humans». Current Opinion in Neurobiology. 16 (4): 391–9. doi:10.1016/j.conb.2006.07.001. PMC 4325365. PMID 16842992.

- ^ a b Rauschecker JP, Tian B, Hauser M (April 1995). «Processing of complex sounds in the macaque nonprimary auditory cortex». Science. 268 (5207): 111–4. Bibcode:1995Sci…268..111R. doi:10.1126/science.7701330. PMID 7701330.

- ^ a b de la Mothe LA, Blumell S, Kajikawa Y, Hackett TA (May 2006). «Cortical connections of the auditory cortex in marmoset monkeys: core and medial belt regions». The Journal of Comparative Neurology. 496 (1): 27–71. doi:10.1002/cne.20923. PMID 16528722. S2CID 38393074.

- ^ de la Mothe LA, Blumell S, Kajikawa Y, Hackett TA (May 2012). «Cortical connections of auditory cortex in marmoset monkeys: lateral belt and parabelt regions». Anatomical Record. 295 (5): 800–21. doi:10.1002/ar.22451. PMC 3379817. PMID 22461313.

- ^ Kaas JH, Hackett TA (October 2000). «Subdivisions of auditory cortex and processing streams in primates». Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 97 (22): 11793–9. Bibcode:2000PNAS…9711793K. doi:10.1073/pnas.97.22.11793. PMC 34351. PMID 11050211.

- ^ Petkov CI, Kayser C, Augath M, Logothetis NK (July 2006). «Functional imaging reveals numerous fields in the monkey auditory cortex». PLOS Biology. 4 (7): e215. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0040215. PMC 1479693. PMID 16774452.

- ^ Morel A, Garraghty PE, Kaas JH (September 1993). «Tonotopic organization, architectonic fields, and connections of auditory cortex in macaque monkeys». The Journal of Comparative Neurology. 335 (3): 437–59. doi:10.1002/cne.903350312. PMID 7693772. S2CID 22872232.

- ^ Rauschecker JP, Tian B (October 2000). «Mechanisms and streams for processing of «what» and «where» in auditory cortex». Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 97 (22): 11800–6. Bibcode:2000PNAS…9711800R. doi:10.1073/pnas.97.22.11800. PMC 34352. PMID 11050212.

- ^ Rauschecker JP, Tian B, Pons T, Mishkin M (May 1997). «Serial and parallel processing in rhesus monkey auditory cortex». The Journal of Comparative Neurology. 382 (1): 89–103. doi:10.1002/(sici)1096-9861(19970526)382:1<89::aid-cne6>3.3.co;2-y. PMID 9136813.

- ^ Sweet RA, Dorph-Petersen KA, Lewis DA (October 2005). «Mapping auditory core, lateral belt, and parabelt cortices in the human superior temporal gyrus». The Journal of Comparative Neurology. 491 (3): 270–89. doi:10.1002/cne.20702. PMID 16134138. S2CID 40822276.

- ^ Wallace MN, Johnston PW, Palmer AR (April 2002). «Histochemical identification of cortical areas in the auditory region of the human brain». Experimental Brain Research. 143 (4): 499–508. doi:10.1007/s00221-002-1014-z. PMID 11914796. S2CID 24211906.

- ^ Da Costa S, van der Zwaag W, Marques JP, Frackowiak RS, Clarke S, Saenz M (October 2011). «Human primary auditory cortex follows the shape of Heschl’s gyrus». The Journal of Neuroscience. 31 (40): 14067–75. doi:10.1523/jneurosci.2000-11.2011. PMC 6623669. PMID 21976491.

- ^ Humphries C, Liebenthal E, Binder JR (April 2010). «Tonotopic organization of human auditory cortex». NeuroImage. 50 (3): 1202–11. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.01.046. PMC 2830355. PMID 20096790.

- ^ Langers DR, van Dijk P (September 2012). «Mapping the tonotopic organization in human auditory cortex with minimally salient acoustic stimulation». Cerebral Cortex. 22 (9): 2024–38. doi:10.1093/cercor/bhr282. PMC 3412441. PMID 21980020.

- ^ Striem-Amit E, Hertz U, Amedi A (March 2011). «Extensive cochleotopic mapping of human auditory cortical fields obtained with phase-encoding fMRI». PLOS ONE. 6 (3): e17832. Bibcode:2011PLoSO…617832S. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0017832. PMC 3063163. PMID 21448274.

- ^ Woods DL, Herron TJ, Cate AD, Yund EW, Stecker GC, Rinne T, Kang X (2010). «Functional properties of human auditory cortical fields». Frontiers in Systems Neuroscience. 4: 155. doi:10.3389/fnsys.2010.00155. PMC 3001989. PMID 21160558.

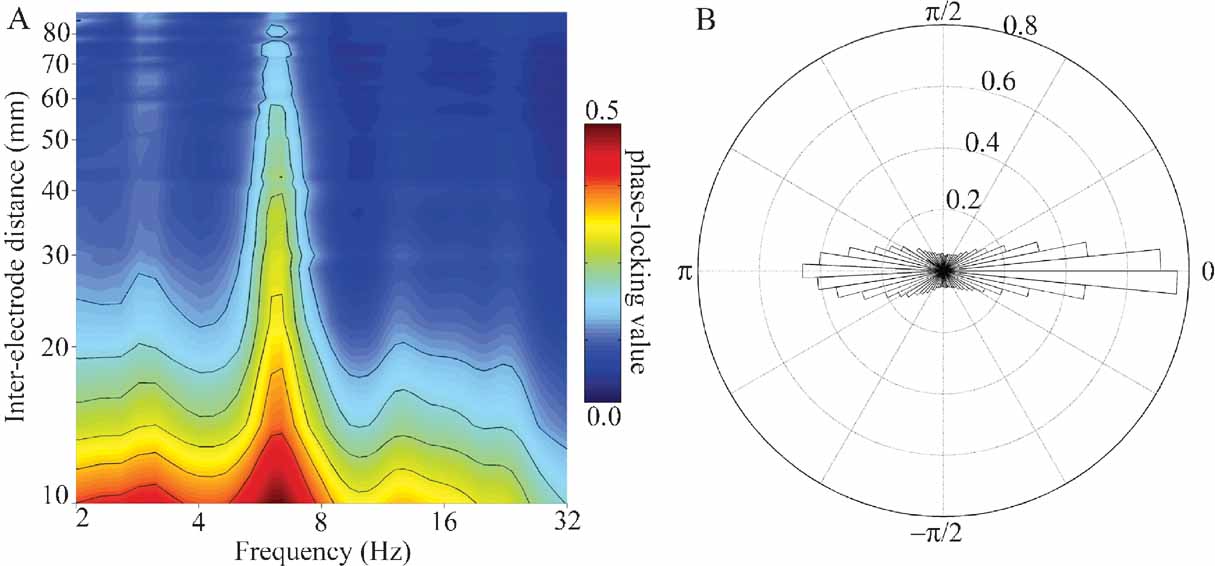

- ^ Gourévitch B, Le Bouquin Jeannès R, Faucon G, Liégeois-Chauvel C (March 2008). «Temporal envelope processing in the human auditory cortex: response and interconnections of auditory cortical areas» (PDF). Hearing Research. 237 (1–2): 1–18. doi:10.1016/j.heares.2007.12.003. PMID 18255243. S2CID 15271578.

- ^ Guéguin M, Le Bouquin-Jeannès R, Faucon G, Chauvel P, Liégeois-Chauvel C (February 2007). «Evidence of functional connectivity between auditory cortical areas revealed by amplitude modulation sound processing». Cerebral Cortex. 17 (2): 304–13. doi:10.1093/cercor/bhj148. PMC 2111045. PMID 16514106.

- ^ a b c Poliva O, Bestelmeyer PE, Hall M, Bultitude JH, Koller K, Rafal RD (September 2015). «Functional Mapping of the Human Auditory Cortex: fMRI Investigation of a Patient with Auditory Agnosia from Trauma to the Inferior Colliculus» (PDF). Cognitive and Behavioral Neurology. 28 (3): 160–80. doi:10.1097/wnn.0000000000000072. PMID 26413744. S2CID 913296.

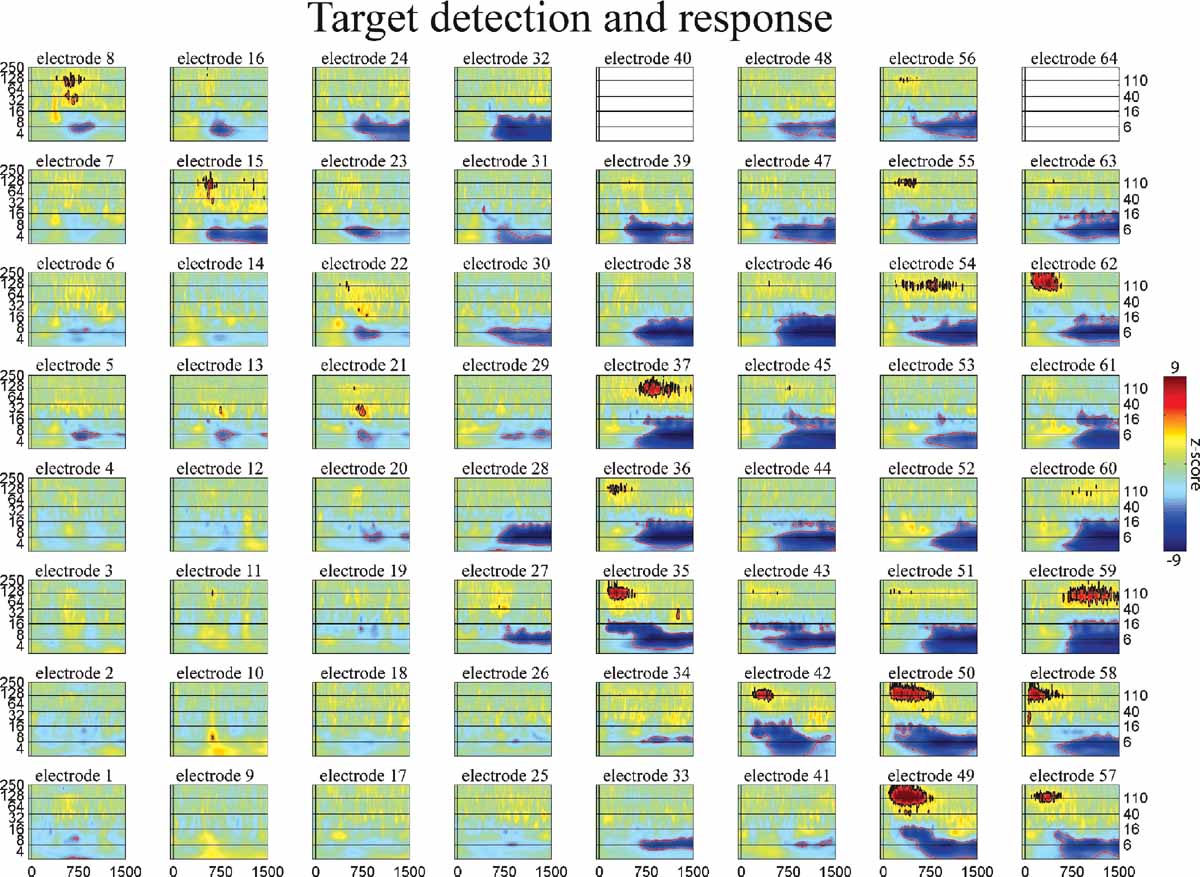

- ^ Chang EF, Edwards E, Nagarajan SS, Fogelson N, Dalal SS, Canolty RT, Kirsch HE, Barbaro NM, Knight RT (June 2011). «Cortical spatio-temporal dynamics underlying phonological target detection in humans». Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 23 (6): 1437–46. doi:10.1162/jocn.2010.21466. PMC 3895406. PMID 20465359.

- ^ Muñoz M, Mishkin M, Saunders RC (September 2009). «Resection of the medial temporal lobe disconnects the rostral superior temporal gyrus from some of its projection targets in the frontal lobe and thalamus». Cerebral Cortex. 19 (9): 2114–30. doi:10.1093/cercor/bhn236. PMC 2722427. PMID 19150921.

- ^ a b Romanski LM, Bates JF, Goldman-Rakic PS (January 1999). «Auditory belt and parabelt projections to the prefrontal cortex in the rhesus monkey». The Journal of Comparative Neurology. 403 (2): 141–57. doi:10.1002/(sici)1096-9861(19990111)403:2<141::aid-cne1>3.0.co;2-v. PMID 9886040. S2CID 42482082.

- ^ Tanaka D (June 1976). «Thalamic projections of the dorsomedial prefrontal cortex in the rhesus monkey (Macaca mulatta)». Brain Research. 110 (1): 21–38. doi:10.1016/0006-8993(76)90206-7. PMID 819108. S2CID 21529048.

- ^ a b Perrodin C, Kayser C, Logothetis NK, Petkov CI (August 2011). «Voice cells in the primate temporal lobe». Current Biology. 21 (16): 1408–15. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2011.07.028. PMC 3398143. PMID 21835625.

- ^ a b c Petkov CI, Kayser C, Steudel T, Whittingstall K, Augath M, Logothetis NK (March 2008). «A voice region in the monkey brain». Nature Neuroscience. 11 (3): 367–74. doi:10.1038/nn2043. PMID 18264095. S2CID 5505773.

- ^ a b Poremba A, Malloy M, Saunders RC, Carson RE, Herscovitch P, Mishkin M (January 2004). «Species-specific calls evoke asymmetric activity in the monkey’s temporal poles». Nature. 427 (6973): 448–51. Bibcode:2004Natur.427..448P. doi:10.1038/nature02268. PMID 14749833. S2CID 4402126.

- ^ Romanski LM, Averbeck BB, Diltz M (February 2005). «Neural representation of vocalizations in the primate ventrolateral prefrontal cortex». Journal of Neurophysiology. 93 (2): 734–47. doi:10.1152/jn.00675.2004. PMID 15371495.

- ^ Russ BE, Ackelson AL, Baker AE, Cohen YE (January 2008). «Coding of auditory-stimulus identity in the auditory non-spatial processing stream». Journal of Neurophysiology. 99 (1): 87–95. doi:10.1152/jn.01069.2007. PMC 4091985. PMID 18003874.

- ^ a b Tsunada J, Lee JH, Cohen YE (June 2011). «Representation of speech categories in the primate auditory cortex». Journal of Neurophysiology. 105 (6): 2634–46. doi:10.1152/jn.00037.2011. PMC 3118748. PMID 21346209.

- ^ Cusick CG, Seltzer B, Cola M, Griggs E (September 1995). «Chemoarchitectonics and corticocortical terminations within the superior temporal sulcus of the rhesus monkey: evidence for subdivisions of superior temporal polysensory cortex». The Journal of Comparative Neurology. 360 (3): 513–35. doi:10.1002/cne.903600312. PMID 8543656. S2CID 42281619.

- ^ Cohen YE, Russ BE, Gifford GW, Kiringoda R, MacLean KA (December 2004). «Selectivity for the spatial and nonspatial attributes of auditory stimuli in the ventrolateral prefrontal cortex». The Journal of Neuroscience. 24 (50): 11307–16. doi:10.1523/jneurosci.3935-04.2004. PMC 6730358. PMID 15601937.

- ^ Deacon TW (February 1992). «Cortical connections of the inferior arcuate sulcus cortex in the macaque brain». Brain Research. 573 (1): 8–26. doi:10.1016/0006-8993(92)90109-m. ISSN 0006-8993. PMID 1374284. S2CID 20670766.

- ^ Lewis JW, Van Essen DC (December 2000). «Corticocortical connections of visual, sensorimotor, and multimodal processing areas in the parietal lobe of the macaque monkey». The Journal of Comparative Neurology. 428 (1): 112–37. doi:10.1002/1096-9861(20001204)428:1<112::aid-cne8>3.0.co;2-9. PMID 11058227. S2CID 16153360.

- ^ Roberts AC, Tomic DL, Parkinson CH, Roeling TA, Cutter DJ, Robbins TW, Everitt BJ (May 2007). «Forebrain connectivity of the prefrontal cortex in the marmoset monkey (Callithrix jacchus): an anterograde and retrograde tract-tracing study». The Journal of Comparative Neurology. 502 (1): 86–112. doi:10.1002/cne.21300. PMID 17335041. S2CID 18262007.

- ^ a b Schmahmann JD, Pandya DN, Wang R, Dai G, D’Arceuil HE, de Crespigny AJ, Wedeen VJ (March 2007). «Association fibre pathways of the brain: parallel observations from diffusion spectrum imaging and autoradiography». Brain. 130 (Pt 3): 630–53. doi:10.1093/brain/awl359. PMID 17293361.

- ^ Seltzer B, Pandya DN (July 1984). «Further observations on parieto-temporal connections in the rhesus monkey». Experimental Brain Research. 55 (2): 301–12. doi:10.1007/bf00237280. PMID 6745368. S2CID 20167953.

- ^ Catani M, Jones DK, ffytche DH (January 2005). «Perisylvian language networks of the human brain». Annals of Neurology. 57 (1): 8–16. doi:10.1002/ana.20319. PMID 15597383. S2CID 17743067.

- ^ Frey S, Campbell JS, Pike GB, Petrides M (November 2008). «Dissociating the human language pathways with high angular resolution diffusion fiber tractography». The Journal of Neuroscience. 28 (45): 11435–44. doi:10.1523/jneurosci.2388-08.2008. PMC 6671318. PMID 18987180.

- ^ Makris N, Papadimitriou GM, Kaiser JR, Sorg S, Kennedy DN, Pandya DN (April 2009). «Delineation of the middle longitudinal fascicle in humans: a quantitative, in vivo, DT-MRI study». Cerebral Cortex. 19 (4): 777–85. doi:10.1093/cercor/bhn124. PMC 2651473. PMID 18669591.

- ^ Menjot de Champfleur N, Lima Maldonado I, Moritz-Gasser S, Machi P, Le Bars E, Bonafé A, Duffau H (January 2013). «Middle longitudinal fasciculus delineation within language pathways: a diffusion tensor imaging study in human». European Journal of Radiology. 82 (1): 151–7. doi:10.1016/j.ejrad.2012.05.034. PMID 23084876.

- ^ Turken AU, Dronkers NF (2011). «The neural architecture of the language comprehension network: converging evidence from lesion and connectivity analyses». Frontiers in Systems Neuroscience. 5: 1. doi:10.3389/fnsys.2011.00001. PMC 3039157. PMID 21347218.

- ^ Saur D, Kreher BW, Schnell S, Kümmerer D, Kellmeyer P, Vry MS, Umarova R, Musso M, Glauche V, Abel S, Huber W, Rijntjes M, Hennig J, Weiller C (November 2008). «Ventral and dorsal pathways for language». Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 105 (46): 18035–40. Bibcode:2008PNAS..10518035S. doi:10.1073/pnas.0805234105. PMC 2584675. PMID 19004769.

- ^ Yin P, Mishkin M, Sutter M, Fritz JB (December 2008). «Early stages of melody processing: stimulus-sequence and task-dependent neuronal activity in monkey auditory cortical fields A1 and R». Journal of Neurophysiology. 100 (6): 3009–29. doi:10.1152/jn.00828.2007. PMC 2604844. PMID 18842950.

- ^ Steinschneider M, Volkov IO, Fishman YI, Oya H, Arezzo JC, Howard MA (February 2005). «Intracortical responses in human and monkey primary auditory cortex support a temporal processing mechanism for encoding of the voice onset time phonetic parameter». Cerebral Cortex. 15 (2): 170–86. doi:10.1093/cercor/bhh120. PMID 15238437.

- ^ Russ BE, Ackelson AL, Baker AE, Cohen YE (January 2008). «Coding of auditory-stimulus identity in the auditory non-spatial processing stream». Journal of Neurophysiology. 99 (1): 87–95. doi:10.1152/jn.01069.2007. PMC 4091985. PMID 18003874.

- ^ Joly O, Pallier C, Ramus F, Pressnitzer D, Vanduffel W, Orban GA (September 2012). «Processing of vocalizations in humans and monkeys: a comparative fMRI study» (PDF). NeuroImage. 62 (3): 1376–89. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2012.05.070. PMID 22659478. S2CID 9441377.

- ^ Scheich H, Baumgart F, Gaschler-Markefski B, Tegeler C, Tempelmann C, Heinze HJ, Schindler F, Stiller D (February 1998). «Functional magnetic resonance imaging of a human auditory cortex area involved in foreground-background decomposition». The European Journal of Neuroscience. 10 (2): 803–9. doi:10.1046/j.1460-9568.1998.00086.x. PMID 9749748. S2CID 42898063.

- ^ Zatorre RJ, Bouffard M, Belin P (April 2004). «Sensitivity to auditory object features in human temporal neocortex». The Journal of Neuroscience. 24 (14): 3637–42. doi:10.1523/jneurosci.5458-03.2004. PMC 6729744. PMID 15071112.

- ^ a b Binder JR, Desai RH, Graves WW, Conant LL (December 2009). «Where is the semantic system? A critical review and meta-analysis of 120 functional neuroimaging studies». Cerebral Cortex. 19 (12): 2767–96. doi:10.1093/cercor/bhp055. PMC 2774390. PMID 19329570.

- ^ Davis MH, Johnsrude IS (April 2003). «Hierarchical processing in spoken language comprehension». The Journal of Neuroscience. 23 (8): 3423–31. doi:10.1523/jneurosci.23-08-03423.2003. PMC 6742313. PMID 12716950.

- ^ Liebenthal E, Binder JR, Spitzer SM, Possing ET, Medler DA (October 2005). «Neural substrates of phonemic perception». Cerebral Cortex. 15 (10): 1621–31. doi:10.1093/cercor/bhi040. PMID 15703256.

- ^ Narain C, Scott SK, Wise RJ, Rosen S, Leff A, Iversen SD, Matthews PM (December 2003). «Defining a left-lateralized response specific to intelligible speech using fMRI». Cerebral Cortex. 13 (12): 1362–8. doi:10.1093/cercor/bhg083. PMID 14615301.

- ^ Obleser J, Boecker H, Drzezga A, Haslinger B, Hennenlotter A, Roettinger M, Eulitz C, Rauschecker JP (July 2006). «Vowel sound extraction in anterior superior temporal cortex». Human Brain Mapping. 27 (7): 562–71. doi:10.1002/hbm.20201. PMC 6871493. PMID 16281283.

- ^ Obleser J, Zimmermann J, Van Meter J, Rauschecker JP (October 2007). «Multiple stages of auditory speech perception reflected in event-related FMRI». Cerebral Cortex. 17 (10): 2251–7. doi:10.1093/cercor/bhl133. PMID 17150986.

- ^ Scott SK, Blank CC, Rosen S, Wise RJ (December 2000). «Identification of a pathway for intelligible speech in the left temporal lobe». Brain. 123 (12): 2400–6. doi:10.1093/brain/123.12.2400. PMC 5630088. PMID 11099443.

- ^ Belin P, Zatorre RJ (November 2003). «Adaptation to speaker’s voice in right anterior temporal lobe». NeuroReport. 14 (16): 2105–2109. doi:10.1097/00001756-200311140-00019. PMID 14600506. S2CID 34183900.

- ^ Benson RR, Whalen DH, Richardson M, Swainson B, Clark VP, Lai S, Liberman AM (September 2001). «Parametrically dissociating speech and nonspeech perception in the brain using fMRI». Brain and Language. 78 (3): 364–96. doi:10.1006/brln.2001.2484. PMID 11703063. S2CID 15328590.

- ^ Leaver AM, Rauschecker JP (June 2010). «Cortical representation of natural complex sounds: effects of acoustic features and auditory object category». The Journal of Neuroscience. 30 (22): 7604–12. doi:10.1523/jneurosci.0296-10.2010. PMC 2930617. PMID 20519535.

- ^ Lewis JW, Phinney RE, Brefczynski-Lewis JA, DeYoe EA (August 2006). «Lefties get it «right» when hearing tool sounds». Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 18 (8): 1314–30. doi:10.1162/jocn.2006.18.8.1314. PMID 16859417. S2CID 14049095.

- ^ Maeder PP, Meuli RA, Adriani M, Bellmann A, Fornari E, Thiran JP, Pittet A, Clarke S (October 2001). «Distinct pathways involved in sound recognition and localization: a human fMRI study» (PDF). NeuroImage. 14 (4): 802–16. doi:10.1006/nimg.2001.0888. PMID 11554799. S2CID 1388647.

- ^ Viceic D, Fornari E, Thiran JP, Maeder PP, Meuli R, Adriani M, Clarke S (November 2006). «Human auditory belt areas specialized in sound recognition: a functional magnetic resonance imaging study» (PDF). NeuroReport. 17 (16): 1659–62. doi:10.1097/01.wnr.0000239962.75943.dd. PMID 17047449. S2CID 14482187.

- ^ Shultz S, Vouloumanos A, Pelphrey K (May 2012). «The superior temporal sulcus differentiates communicative and noncommunicative auditory signals». Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 24 (5): 1224–32. doi:10.1162/jocn_a_00208. PMID 22360624. S2CID 10784270.

- ^ DeWitt I, Rauschecker JP (February 2012). «Phoneme and word recognition in the auditory ventral stream». Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 109 (8): E505-14. doi:10.1073/pnas.1113427109. PMC 3286918. PMID 22308358.

- ^ a b c d Lachaux JP, Jerbi K, Bertrand O, Minotti L, Hoffmann D, Schoendorff B, Kahane P (October 2007). «A blueprint for real-time functional mapping via human intracranial recordings». PLOS ONE. 2 (10): e1094. Bibcode:2007PLoSO…2.1094L. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0001094. PMC 2040217. PMID 17971857.

- ^ a b Matsumoto R, Imamura H, Inouchi M, Nakagawa T, Yokoyama Y, Matsuhashi M, Mikuni N, Miyamoto S, Fukuyama H, Takahashi R, Ikeda A (April 2011). «Left anterior temporal cortex actively engages in speech perception: A direct cortical stimulation study». Neuropsychologia. 49 (5): 1350–1354. doi:10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2011.01.023. hdl:2433/141342. PMID 21251921. S2CID 1831334.

- ^ a b c d Roux FE, Miskin K, Durand JB, Sacko O, Réhault E, Tanova R, Démonet JF (October 2015). «Electrostimulation mapping of comprehension of auditory and visual words». Cortex; A Journal Devoted to the Study of the Nervous System and Behavior. 71: 398–408. doi:10.1016/j.cortex.2015.07.001. PMID 26332785. S2CID 39964328.

- ^ Fritz J, Mishkin M, Saunders RC (June 2005). «In search of an auditory engram». Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 102 (26): 9359–64. Bibcode:2005PNAS..102.9359F. doi:10.1073/pnas.0503998102. PMC 1166637. PMID 15967995.

- ^ Stepien LS, Cordeau JP, Rasmussen T (1960). «The effect of temporal lobe and hippocampal lesions on auditory and visual recent memory in monkeys». Brain. 83 (3): 470–489. doi:10.1093/brain/83.3.470. ISSN 0006-8950.

- ^ Strominger NL, Oesterreich RE, Neff WD (June 1980). «Sequential auditory and visual discriminations after temporal lobe ablation in monkeys». Physiology & Behavior. 24 (6): 1149–56. doi:10.1016/0031-9384(80)90062-1. PMID 6774349. S2CID 7494152.

- ^ Kaiser J, Ripper B, Birbaumer N, Lutzenberger W (October 2003). «Dynamics of gamma-band activity in human magnetoencephalogram during auditory pattern working memory». NeuroImage. 20 (2): 816–27. doi:10.1016/s1053-8119(03)00350-1. PMID 14568454. S2CID 19373941.

- ^ Buchsbaum BR, Olsen RK, Koch P, Berman KF (November 2005). «Human dorsal and ventral auditory streams subserve rehearsal-based and echoic processes during verbal working memory». Neuron. 48 (4): 687–97. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2005.09.029. PMID 16301183. S2CID 13202604.

- ^ Scott BH, Mishkin M, Yin P (July 2012). «Monkeys have a limited form of short-term memory in audition». Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 109 (30): 12237–41. Bibcode:2012PNAS..10912237S. doi:10.1073/pnas.1209685109. PMC 3409773. PMID 22778411.

- ^ Noppeney U, Patterson K, Tyler LK, Moss H, Stamatakis EA, Bright P, Mummery C, Price CJ (April 2007). «Temporal lobe lesions and semantic impairment: a comparison of herpes simplex virus encephalitis and semantic dementia». Brain. 130 (Pt 4): 1138–47. doi:10.1093/brain/awl344. PMID 17251241.

- ^ Patterson K, Nestor PJ, Rogers TT (December 2007). «Where do you know what you know? The representation of semantic knowledge in the human brain». Nature Reviews. Neuroscience. 8 (12): 976–87. doi:10.1038/nrn2277. PMID 18026167. S2CID 7310189.

- ^ Schwartz MF, Kimberg DY, Walker GM, Faseyitan O, Brecher A, Dell GS, Coslett HB (December 2009). «Anterior temporal involvement in semantic word retrieval: voxel-based lesion-symptom mapping evidence from aphasia». Brain. 132 (Pt 12): 3411–27. doi:10.1093/brain/awp284. PMC 2792374. PMID 19942676.

- ^ Hamberger MJ, McClelland S, McKhann GM, Williams AC, Goodman RR (March 2007). «Distribution of auditory and visual naming sites in nonlesional temporal lobe epilepsy patients and patients with space-occupying temporal lobe lesions». Epilepsia. 48 (3): 531–8. doi:10.1111/j.1528-1167.2006.00955.x. PMID 17326797. S2CID 12642281.

- ^ a b c Duffau H (March 2008). «The anatomo-functional connectivity of language revisited. New insights provided by electrostimulation and tractography». Neuropsychologia. 46 (4): 927–34. doi:10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2007.10.025. PMID 18093622. S2CID 40514753.

- ^ Vigneau M, Beaucousin V, Hervé PY, Duffau H, Crivello F, Houdé O, Mazoyer B, Tzourio-Mazoyer N (May 2006). «Meta-analyzing left hemisphere language areas: phonology, semantics, and sentence processing». NeuroImage. 30 (4): 1414–32. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2005.11.002. PMID 16413796. S2CID 8870165.

- ^ a b Creutzfeldt O, Ojemann G, Lettich E (October 1989). «Neuronal activity in the human lateral temporal lobe. I. Responses to speech». Experimental Brain Research. 77 (3): 451–75. doi:10.1007/bf00249600. hdl:11858/00-001M-0000-002C-89EA-3. PMID 2806441. S2CID 19952034.

- ^ Mazoyer BM, Tzourio N, Frak V, Syrota A, Murayama N, Levrier O, Salamon G, Dehaene S, Cohen L, Mehler J (October 1993). «The cortical representation of speech» (PDF). Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 5 (4): 467–79. doi:10.1162/jocn.1993.5.4.467. PMID 23964919. S2CID 22265355.

- ^ Humphries C, Love T, Swinney D, Hickok G (October 2005). «Response of anterior temporal cortex to syntactic and prosodic manipulations during sentence processing». Human Brain Mapping. 26 (2): 128–38. doi:10.1002/hbm.20148. PMC 6871757. PMID 15895428.

- ^ Humphries C, Willard K, Buchsbaum B, Hickok G (June 2001). «Role of anterior temporal cortex in auditory sentence comprehension: an fMRI study». NeuroReport. 12 (8): 1749–52. doi:10.1097/00001756-200106130-00046. PMID 11409752. S2CID 13039857.

- ^ Vandenberghe R, Nobre AC, Price CJ (May 2002). «The response of left temporal cortex to sentences». Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 14 (4): 550–60. doi:10.1162/08989290260045800. PMID 12126497. S2CID 21607482.

- ^ Friederici AD, Rüschemeyer SA, Hahne A, Fiebach CJ (February 2003). «The role of left inferior frontal and superior temporal cortex in sentence comprehension: localizing syntactic and semantic processes». Cerebral Cortex. 13 (2): 170–7. doi:10.1093/cercor/13.2.170. PMID 12507948.

- ^ Xu J, Kemeny S, Park G, Frattali C, Braun A (2005). «Language in context: emergent features of word, sentence, and narrative comprehension». NeuroImage. 25 (3): 1002–15. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.12.013. PMID 15809000. S2CID 25570583.

- ^ Rogalsky C, Hickok G (April 2009). «Selective attention to semantic and syntactic features modulates sentence processing networks in anterior temporal cortex». Cerebral Cortex. 19 (4): 786–96. doi:10.1093/cercor/bhn126. PMC 2651476. PMID 18669589.

- ^ Pallier C, Devauchelle AD, Dehaene S (February 2011). «Cortical representation of the constituent structure of sentences». Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 108 (6): 2522–7. doi:10.1073/pnas.1018711108. PMC 3038732. PMID 21224415.

- ^ Brennan J, Nir Y, Hasson U, Malach R, Heeger DJ, Pylkkänen L (February 2012). «Syntactic structure building in the anterior temporal lobe during natural story listening». Brain and Language. 120 (2): 163–73. doi:10.1016/j.bandl.2010.04.002. PMC 2947556. PMID 20472279.

- ^ Kotz SA, von Cramon DY, Friederici AD (October 2003). «Differentiation of syntactic processes in the left and right anterior temporal lobe: Event-related brain potential evidence from lesion patients». Brain and Language. 87 (1): 135–136. doi:10.1016/s0093-934x(03)00236-0. S2CID 54320415.

- ^ Martin RC, Shelton JR, Yaffee LS (February 1994). «Language processing and working memory: Neuropsychological evidence for separate phonological and semantic capacities». Journal of Memory and Language. 33 (1): 83–111. doi:10.1006/jmla.1994.1005.

- ^ Magnusdottir S, Fillmore P, den Ouden DB, Hjaltason H, Rorden C, Kjartansson O, Bonilha L, Fridriksson J (October 2013). «Damage to left anterior temporal cortex predicts impairment of complex syntactic processing: a lesion-symptom mapping study». Human Brain Mapping. 34 (10): 2715–23. doi:10.1002/hbm.22096. PMC 6869931. PMID 22522937.

- ^ Bornkessel-Schlesewsky I, Schlesewsky M, Small SL, Rauschecker JP (March 2015). «Neurobiological roots of language in primate audition: common computational properties». Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 19 (3): 142–50. doi:10.1016/j.tics.2014.12.008. PMC 4348204. PMID 25600585.

- ^ Hickok G, Okada K, Barr W, Pa J, Rogalsky C, Donnelly K, Barde L, Grant A (December 2008). «Bilateral capacity for speech sound processing in auditory comprehension: evidence from Wada procedures». Brain and Language. 107 (3): 179–84. doi:10.1016/j.bandl.2008.09.006. PMC 2644214. PMID 18976806.

- ^ Zaidel E (September 1976). «Auditory Vocabulary of the Right Hemisphere Following Brain Bisection or Hemidecortication». Cortex. 12 (3): 191–211. doi:10.1016/s0010-9452(76)80001-9. ISSN 0010-9452. PMID 1000988. S2CID 4479925.

- ^ Poeppel D (October 2001). «Pure word deafness and the bilateral processing of the speech code». Cognitive Science. 25 (5): 679–693. doi:10.1016/s0364-0213(01)00050-7.

- ^ Ulrich G (May 1978). «Interhemispheric functional relationships in auditory agnosia. An analysis of the preconditions and a conceptual model». Brain and Language. 5 (3): 286–300. doi:10.1016/0093-934x(78)90027-5. PMID 656899. S2CID 33841186.

- ^ Stewart L, Walsh V, Frith U, Rothwell JC (March 2001). «TMS produces two dissociable types of speech disruption» (PDF). NeuroImage. 13 (3): 472–8. doi:10.1006/nimg.2000.0701. PMID 11170812. S2CID 10392466.

- ^ Acheson DJ, Hamidi M, Binder JR, Postle BR (June 2011). «A common neural substrate for language production and verbal working memory». Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 23 (6): 1358–67. doi:10.1162/jocn.2010.21519. PMC 3053417. PMID 20617889.

- ^ Desmurget M, Reilly KT, Richard N, Szathmari A, Mottolese C, Sirigu A (May 2009). «Movement intention after parietal cortex stimulation in humans». Science. 324 (5928): 811–3. Bibcode:2009Sci…324..811D. doi:10.1126/science.1169896. PMID 19423830. S2CID 6555881.

- ^ Edwards E, Nagarajan SS, Dalal SS, Canolty RT, Kirsch HE, Barbaro NM, Knight RT (March 2010). «Spatiotemporal imaging of cortical activation during verb generation and picture naming». NeuroImage. 50 (1): 291–301. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.12.035. PMC 2957470. PMID 20026224.

- ^ Boatman D, Gordon B, Hart J, Selnes O, Miglioretti D, Lenz F (August 2000). «Transcortical sensory aphasia: revisited and revised». Brain. 123 (8): 1634–42. doi:10.1093/brain/123.8.1634. PMID 10908193.

- ^ a b c Turkeltaub PE, Coslett HB (July 2010). «Localization of sublexical speech perception components». Brain and Language. 114 (1): 1–15. doi:10.1016/j.bandl.2010.03.008. PMC 2914564. PMID 20413149.

- ^ Chang EF, Rieger JW, Johnson K, Berger MS, Barbaro NM, Knight RT (November 2010). «Categorical speech representation in human superior temporal gyrus». Nature Neuroscience. 13 (11): 1428–32. doi:10.1038/nn.2641. PMC 2967728. PMID 20890293.

- ^ Buchsbaum BR, Hickok G, Humphries C (September 2001). «Role of left posterior superior temporal gyrus in phonological processing for speech perception and production». Cognitive Science. 25 (5): 663–678. doi:10.1207/s15516709cog2505_2. ISSN 0364-0213.

- ^ Wise RJ, Scott SK, Blank SC, Mummery CJ, Murphy K, Warburton EA (January 2001). «Separate neural subsystems within ‘Wernicke’s area’«. Brain. 124 (Pt 1): 83–95. doi:10.1093/brain/124.1.83. PMID 11133789.

- ^ Hickok G, Buchsbaum B, Humphries C, Muftuler T (July 2003). «Auditory-motor interaction revealed by fMRI: speech, music, and working memory in area Spt». Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 15 (5): 673–82. doi:10.1162/089892903322307393. PMID 12965041.

- ^ Warren JE, Wise RJ, Warren JD (December 2005). «Sounds do-able: auditory-motor transformations and the posterior temporal plane». Trends in Neurosciences. 28 (12): 636–43. doi:10.1016/j.tins.2005.09.010. PMID 16216346. S2CID 36678139.

- ^ Hickok G, Poeppel D (May 2007). «The cortical organization of speech processing». Nature Reviews. Neuroscience. 8 (5): 393–402. doi:10.1038/nrn2113. PMID 17431404. S2CID 6199399.

- ^ Karbe H, Herholz K, Weber-Luxenburger G, Ghaemi M, Heiss WD (June 1998). «Cerebral networks and functional brain asymmetry: evidence from regional metabolic changes during word repetition». Brain and Language. 63 (1): 108–21. doi:10.1006/brln.1997.1937. PMID 9642023. S2CID 31335617.

- ^ Giraud AL, Price CJ (August 2001). «The constraints functional neuroimaging places on classical models of auditory word processing». Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 13 (6): 754–65. doi:10.1162/08989290152541421. PMID 11564320. S2CID 13916709.

- ^ Graves WW, Grabowski TJ, Mehta S, Gupta P (September 2008). «The left posterior superior temporal gyrus participates specifically in accessing lexical phonology». Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 20 (9): 1698–710. doi:10.1162/jocn.2008.20113. PMC 2570618. PMID 18345989.

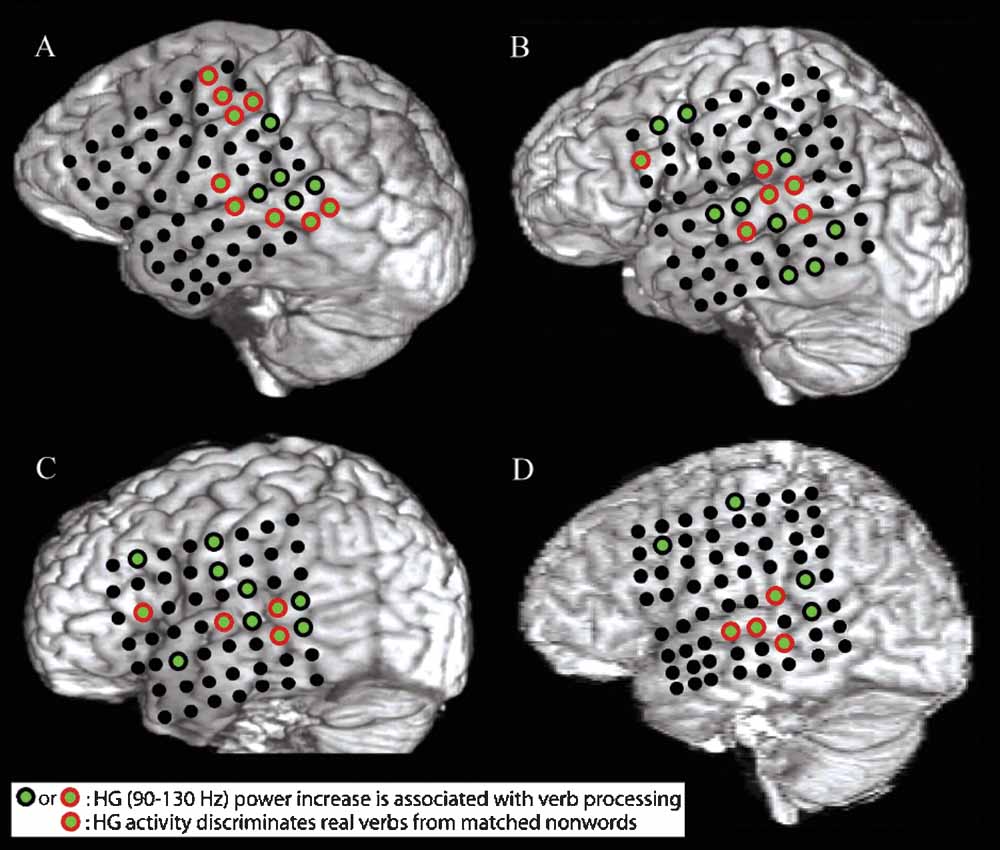

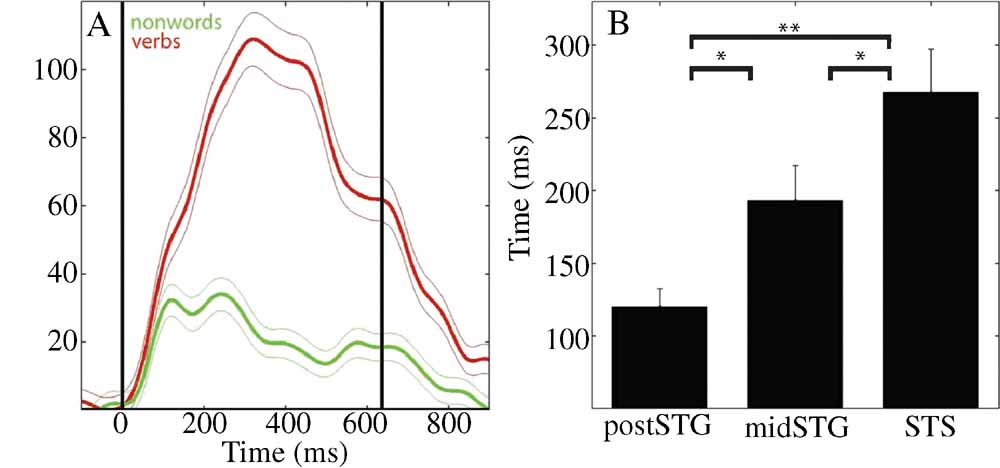

- ^ a b Towle VL, Yoon HA, Castelle M, Edgar JC, Biassou NM, Frim DM, Spire JP, Kohrman MH (August 2008). «ECoG gamma activity during a language task: differentiating expressive and receptive speech areas». Brain. 131 (Pt 8): 2013–27. doi:10.1093/brain/awn147. PMC 2724904. PMID 18669510.

- ^ Selnes OA, Knopman DS, Niccum N, Rubens AB (June 1985). «The critical role of Wernicke’s area in sentence repetition». Annals of Neurology. 17 (6): 549–57. doi:10.1002/ana.410170604. PMID 4026225. S2CID 12914191.

- ^ Axer H, von Keyserlingk AG, Berks G, von Keyserlingk DG (March 2001). «Supra- and infrasylvian conduction aphasia». Brain and Language. 76 (3): 317–31. doi:10.1006/brln.2000.2425. PMID 11247647. S2CID 25406527.

- ^ Bartha L, Benke T (April 2003). «Acute conduction aphasia: an analysis of 20 cases». Brain and Language. 85 (1): 93–108. doi:10.1016/s0093-934x(02)00502-3. PMID 12681350. S2CID 18466425.

- ^ Baldo JV, Katseff S, Dronkers NF (March 2012). «Brain Regions Underlying Repetition and Auditory-Verbal Short-term Memory Deficits in Aphasia: Evidence from Voxel-based Lesion Symptom Mapping». Aphasiology. 26 (3–4): 338–354. doi:10.1080/02687038.2011.602391. PMC 4070523. PMID 24976669.

- ^ Baldo JV, Klostermann EC, Dronkers NF (May 2008). «It’s either a cook or a baker: patients with conduction aphasia get the gist but lose the trace». Brain and Language. 105 (2): 134–40. doi:10.1016/j.bandl.2007.12.007. PMID 18243294. S2CID 997735.

- ^ Fridriksson J, Kjartansson O, Morgan PS, Hjaltason H, Magnusdottir S, Bonilha L, Rorden C (August 2010). «Impaired speech repetition and left parietal lobe damage». The Journal of Neuroscience. 30 (33): 11057–61. doi:10.1523/jneurosci.1120-10.2010. PMC 2936270. PMID 20720112.

- ^ Buchsbaum BR, Baldo J, Okada K, Berman KF, Dronkers N, D’Esposito M, Hickok G (December 2011). «Conduction aphasia, sensory-motor integration, and phonological short-term memory — an aggregate analysis of lesion and fMRI data». Brain and Language. 119 (3): 119–28. doi:10.1016/j.bandl.2010.12.001. PMC 3090694. PMID 21256582.

- ^ Yamada K, Nagakane Y, Mizuno T, Hosomi A, Nakagawa M, Nishimura T (March 2007). «MR tractography depicting damage to the arcuate fasciculus in a patient with conduction aphasia». Neurology. 68 (10): 789. doi:10.1212/01.wnl.0000256348.65744.b2. PMID 17339591.

- ^ Breier JI, Hasan KM, Zhang W, Men D, Papanicolaou AC (March 2008). «Language dysfunction after stroke and damage to white matter tracts evaluated using diffusion tensor imaging». AJNR. American Journal of Neuroradiology. 29 (3): 483–7. doi:10.3174/ajnr.A0846. PMC 3073452. PMID 18039757.

- ^ Zhang Y, Wang C, Zhao X, Chen H, Han Z, Wang Y (September 2010). «Diffusion tensor imaging depicting damage to the arcuate fasciculus in patients with conduction aphasia: a study of the Wernicke-Geschwind model». Neurological Research. 32 (7): 775–8. doi:10.1179/016164109×12478302362653. PMID 19825277. S2CID 22960870.

- ^ Jones OP, Prejawa S, Hope TM, Oberhuber M, Seghier ML, Leff AP, Green DW, Price CJ (2014). «Sensory-to-motor integration during auditory repetition: a combined fMRI and lesion study». Frontiers in Human Neuroscience. 8: 24. doi:10.3389/fnhum.2014.00024. PMC 3908611. PMID 24550807.

- ^ Quigg M, Fountain NB (March 1999). «Conduction aphasia elicited by stimulation of the left posterior superior temporal gyrus». Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry. 66 (3): 393–6. doi:10.1136/jnnp.66.3.393. PMC 1736266. PMID 10084542.

- ^ Quigg M, Geldmacher DS, Elias WJ (May 2006). «Conduction aphasia as a function of the dominant posterior perisylvian cortex. Report of two cases». Journal of Neurosurgery. 104 (5): 845–8. doi:10.3171/jns.2006.104.5.845. PMID 16703895.

- ^ Service E, Kohonen V (April 1995). «Is the relation between phonological memory and foreign language learning accounted for by vocabulary acquisition?». Applied Psycholinguistics. 16 (2): 155–172. doi:10.1017/S0142716400007062. S2CID 143974128.

- ^ Service E (July 1992). «Phonology, working memory, and foreign-language learning». The Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology. A, Human Experimental Psychology. 45 (1): 21–50. doi:10.1080/14640749208401314. PMID 1636010. S2CID 43268252.

- ^ Matsumoto R, Nair DR, LaPresto E, Najm I, Bingaman W, Shibasaki H, Lüders HO (October 2004). «Functional connectivity in the human language system: a cortico-cortical evoked potential study». Brain. 127 (Pt 10): 2316–30. doi:10.1093/brain/awh246. PMID 15269116.

- ^ Kimura D, Watson N (November 1989). «The relation between oral movement control and speech». Brain and Language. 37 (4): 565–90. doi:10.1016/0093-934x(89)90112-0. PMID 2479446. S2CID 39913744.

- ^ Tourville JA, Reilly KJ, Guenther FH (February 2008). «Neural mechanisms underlying auditory feedback control of speech». NeuroImage. 39 (3): 1429–43. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.09.054. PMC 3658624. PMID 18035557.

- ^ Chang EF, Rieger JW, Johnson K, Berger MS, Barbaro NM, Knight RT (November 2010). «Categorical speech representation in human superior temporal gyrus». Nature Neuroscience. 13 (11): 1428–32. doi:10.1038/nn.2641. PMC 2967728. PMID 20890293.

- ^ Nath AR, Beauchamp MS (January 2012). «A neural basis for interindividual differences in the McGurk effect, a multisensory speech illusion». NeuroImage. 59 (1): 781–7. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.07.024. PMC 3196040. PMID 21787869.