From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Arabic is a Semitic language and English is an Indo-European language. The following words have been acquired either directly from Arabic or else indirectly by passing from Arabic into other languages and then into English. Most entered one or more of the Romance languages, before entering English.

To qualify for this list, a word must be reported in etymology dictionaries as having descended from Arabic. A handful of dictionaries have been used as the source for the list.[1] Words associated with the Islamic religion are omitted; for Islamic words, see Glossary of Islam. Archaic and rare words are also omitted. A bigger listing including words very rarely seen in English is at Wiktionary dictionary.

Given the number of words which have entered English from Arabic, this list is split alphabetically into sublists, as listed below:

- List of English words of Arabic origin (A-B)

- List of English words of Arabic origin (C-F)

- List of English words of Arabic origin (G-J)

- List of English words of Arabic origin (K-M)

- List of English words of Arabic origin (N-S)

- List of English words of Arabic origin (T-Z)

- List of English words of Arabic origin: Addenda for certain specialist vocabularies

Addenda for certain specialist vocabularies[edit]

Islamic terms[edit]

Arabic astronomical and astrological names[edit]

Arabic botanical names[edit]

The following plant names entered medieval Latin texts from Arabic. Today, in descent from the medieval Latin, they are international systematic classification names (commonly known as «Latin» names): Azadirachta, Berberis, Cakile, Carthamus, Cuscuta, Doronicum, Galanga, Musa, Nuphar, Ribes, Senna, Taraxacum, Usnea, Physalis alkekengi, Melia azedarach, Centaurea behen, Terminalia bellerica, Terminalia chebula, Cheiranthus cheiri, Piper cubeba, Phyllanthus emblica, Peganum harmala, Salsola kali, Prunus mahaleb, Datura metel, Daphne mezereum, Rheum ribes, Jasminum sambac, Cordia sebestena, Operculina turpethum, Curcuma zedoaria, Alpinia zerumbet + Zingiber zerumbet. (List incomplete.)[2]

Over ninety percent of those botanical names were introduced to medieval Latin in a herbal medicine context. They include names of medicinal plants from Tropical Asia for which there had been no prior Latin or Greek name, such as azedarach, bellerica, cubeba, emblica, galanga, metel, turpethum, zedoaria and zerumbet. Another sizeable portion are ultimately Iranian names of medicinal plants of Iran. The Arabic-to-Latin translation of Ibn Sina’s The Canon of Medicine helped establish many Arabic plant names in later medieval Latin.[2] A book about medicating agents by Serapion the Younger containing hundreds of Arabic botanical names circulated in Latin among apothecaries in the 14th and 15th centuries.[3] Medieval Arabic botany was primarily concerned with the use of plants for medicines. In a modern etymology analysis of one medieval Arabic list of medicines, the names of the medicines —primarily plant names— were assessed to be 31% ancient Mesopotamian names, 23% Greek names, 18% Persian, 13% Indian (often via Persian), 5% uniquely Arabic, and 3% Egyptian, with the remaining 7% of unassessable origin.[4]

The Italian botanist Prospero Alpini stayed in Egypt for several years in the 1580s. He introduced to Latin botany from Arabic from Egypt the names Abrus, Abelmoschus, Lablab, Melochia, each of which designated plants that were unknown to Western European botanists before Alpini, plants native to tropical Asia that were grown with artificial irrigation in Egypt at the time.[5]

In the early 1760s Peter Forsskål systematically cataloged plants and fishes in the Red Sea area. For genera and species that did not already have Latin names, Forsskål used the common Arabic names as the scientific names. This became the international standard for most of what he cataloged. Forsskål’s Latinized Arabic plant genus names include Aerva, Arnebia, Cadaba, Ceruana, Maerua, Maesa, Themeda, and others.[6]

Some additional miscellaneous botanical names with Arabic ancestry include Abutilon, Alchemilla, Alhagi, Argania, argel, Averrhoa, Avicennia, azarolus + acerola, bonduc, lebbeck, Retama, seyal.[7] (List incomplete).

Arabic textile words[edit]

The list above included the six textile fabric names cotton, damask, gauze, macramé, mohair, & muslin, and the three textile dye names anil, crimson/kermes, and safflower, and the garment names jumper and sash. The following are three lesser-used textile words that were not listed: camlet,[8] morocco leather,[9] and tabby. Those have established Arabic ancestry. The following are six textile fabric words whose ancestry is not established and not adequately in evidence, but Arabic ancestry is entertained by many reporters. Five of the six have Late Medieval start dates in the Western languages and the sixth started in the 16th century. Buckram, Chiffon, Fustian, Gabardine, Satin, and Wadding (padding). The fabric Taffeta has provenance in 14th-century French, Italian, Catalan, Spanish, and English, and today it is often guessed to come ultimately from a Persian word for woven (tāftah), and it might have Arabic intermediation. Fustic is a textile dye. The name is traceable to late medieval Spanish fustet dye, which is often guessed to be from an Arabic source.[10] Carthamin is another old textile dye. Its name was borrowed in the late medieval West from Arabic قرطم qartam | qirtim | qurtum = «the carthamin dye plant or its seeds».[11] The textile industry was the largest manufacturing industry in the Arabic-speaking lands in the medieval and early modern eras.

Arabic cuisine words[edit]

The following words are from Arabic, although some of them have entered Western European languages via other languages. Baba ghanoush, Falafel, Fattoush, Halva, Hummus, Kibbeh, Kebab, Lahmacun, Shawarma, Tabouleh, Tahini, Za’atar . Some cuisine words of lesser circulation are Ful medames, Kabsa, Kushari, Labneh, Mahleb, Mulukhiyah, Ma’amoul, Mansaf, Shanklish, Tepsi Baytinijan . For more see Arab cuisine. Middle Eastern cuisine words were rare before 1970 in English, being mostly confined to travellers’ reports. Usage increased rapidly in the 1970s for certain words.

Arabic music words[edit]

Some words used in English in talking about Arabic music: Ataba, Baladi, Dabke, Darbouka, Jins, Khaleeji, Maqam, Mawal, Mizmar, Oud, Qanun, Raï, Raqs sharqi, Taqsim.

Arabic place names[edit]

Footnotes[edit]

- ^ The dictionaries used to compile the list are these: Centre National de Ressources Textuelles et Lexicales: Etymologies, Online Etymology Dictionary, Random House Dictionary, Concise Oxford English Dictionary, American Heritage Dictionary, Collins English Dictionary, Merriam-Webster’s Collegiate Dictionary, Arabismen im Deutschen: lexikalische Transferenzen vom Arabischen ins Deutsche, by Raja Tazi (year 1998), A New English Dictionary on Historical Principles (a.k.a. «NED») (published in pieces between 1888 and 1928), An Etymological Dictionary of Modern English (year 1921) by Ernest Weekley. Footnotes for individual words have supplementary other references. The most frequently cited of the supplementary references is Glossaire des mots espagnols et portugais dérivés de l’arabe (year 1869) by Reinhart Dozy.

- ^ a b References for the medieval Arabic sources and medieval Latin borrowings of those plant names are as follows. Ones marked «(F)» go to the French dictionary at Centre National de Ressources Textuelles et Lexicales, ones marked «(R)» go to Random House Dictionary, and other references are identified with terse labels: Berberis(R), انبرباريس anbarbārīs = Berberis(Ibn Sina), امبرباريس ambarbārīs = Berberis(Ibn Al-Baitar), الأمبرباريس al-ambarbārīs is also called البرباريس al-barbārīs Archived 29 October 2013 at the Wayback Machine(Fairuzabadi’s dictionary), Galen uses name «Oxyacantha» for Berberis(John Gerarde), Arabic amiberberis = Latin Berberis(Matthaeus Silvaticus), Berberis is frequent in Constantinus Africanus (Constantinus Africanus was the introducer of plantname Berberis into medieval Latin), Berberis(Raja Tazi 1998), Barberry(Skeat 1888);; Cakile(Henri Lammens 1890), Cakile(Pierre Guigues 1905), Kakile Serapionis(John Gerarde 1597), Chakile(Serapion the Younger, medieval Latin);; for Carthamus see Carthamin;; Cuscute(F), Cuscuta (Etimología), spelled كشوث kushūth in Ibn al-Baitar;; Doronicum(F), Doronicum(R), spelled درونج dorūnaj in Ibn al-Baitar;; Garingal & Galanga(F), Galingale & Galanga(NED);; Musa(Devic), Musa(Alphita), موز mauz(Ibn al-Baitar), Muse #4 and Musa(NED);; Nuphar (nénuphar)(F), Nénuphar(Lammens);; Ribès(Pierre Guigues 1903 in preface to translation of Najm al-Din Mahmud (died 1330)), Ribes(Lammens 1890), the meaning of late medieval Latin ribes was Rheum ribes – e.g. e.g. – and the medieval Arabic ريباس rībās had the very same meaning – e.g. ;; Senna(F), Senna(R), Séné(Lammens), Sene in Alphita, السنى al-sanā and السني al-senī in Ibn al-Baitar;; Taraxacum(Skeat), Ataraxacon(Alphita), Taraxacum(R);; Usnea(F), Usnea(R), Usnee(Simon of Genoa), Usnée(Lammens);; alkekengi(F), alkekengi(R);; azedarach(F), azedarach(Garland Cannon), azadarach + azedarach(Matthaeus Silvaticus anno 1317), azedarach produced Azadirachta;; béhen(Devic, year 1876), Behemen = behen = behem says Matthaeus Silvaticus (year 1317); this name is بهمن behmen | bahman in Ibn al-Baitar and Ibn Sina;; bellerica(Yule), bellerica(Devic), beliligi = belirici = bellerici(Simon of Genoa), بليلج belīlej in Ibn al-Baitar;; chebula(Yule), kebulus = chebulae(Alphita), chébule(Devic);; cheiranthe(Devic), keiri(NED), خيري kheīrī(Ibn al-Awwam);; cubeba(F), cubeba(R);; emblic(Yule), emblic(Devic), emblic(Serapion the Younger);; harmala(Tazi), harmale(Devic), harmala(other), harmala(more details);; (Salsola) kali(F), kali = a marine littoral plant, an Arabic name(Simon of Genoa year 1292 in Latin, also in Matthaeus Silvaticus);; mahaleb(F), mahaleb(Ibn al-Awwam), mahaleb(Matthaeus Silvaticus year 1317);; mathil->metel(other), metel(Devic), nux methel(Serapion the Younger), جوز ماثل jūz māthil(Ibn Sina);; mezereum(R), mézéréon(Devic), mezereon(Alphita: see editor’s footnote quoting Matthaeus Silvaticus and John Gerarde), spelled مازريون māzarīūn in Ibn Sina and Ibn al-Baitar;; sambac(Devic), zambacca(synonyms of Petrus de Abano, died c. 1316), sambacus(Simon of Genoa), زنبق = دهن الياسمين (zanbaq in Lisan al-Arab);; sebesten(other), sebesten(Devic), sebesten(Alphita) (sebesten in late medieval Latin referred to Cordia myxa, not Cordia sebestena, and the medieval Arabic سبستان sebestān was Cordia myxa);; turpeth(F), turpeth(R);; zedoaria(F), zedoaria(R);; zérumbet(F), zerumbet is from medieval Latin zurumbet | zurumbeth | zerumbet which is from Arabic زرنباد zurunbād | zarunbād. The great majority of the above plant names can be seen in Latin in the late-13th-century medical-botany dictionary Synonyma Medicinae by Simon of Genoa (online) and in the mid-15th-century Latin medical-botany dictionary called the Alphita (online); and the few that are not in either of those two dictionaries can be seen in Latin in the book on medicaments by Serapion the Younger circa 1300 (online). None of the names are found in Latin in early medieval or classical Latin botany or medicine books — partially excepting a complication over the name harmala, and excepting galanga and zedoaria because they have Latin records beginning in the 9th or 10th centuries. In other words nearly all the names were introduced to Latin in the later-medieval period, specifically from the late 11th through late 13th centuries. Most early Latin users lived in Italy. All of the names, without exception, are in the Arabic-to-Latin medical translations of Constantinus Africanus (died c. 1087) and/or Gerardus Cremonensis (died c. 1187) and/or Serapion the Younger (dated later 13th century Latin). The Arabic predecessors of the great majority of the names can be seen in Arabic as entries in Part Two of The Canon of Medicine of Ibn Sina, dated about 1025 in Arabic, which became a widely circulated book in Latin medical circles in the 13th and 14th centuries: an Arabic copy is at DDC.AUB.edu.lb. All of the Arabic predecessor plant-names without exception, and usually with better descriptions of the plants (compared to Ibn Sina’s descriptions), are in Ibn al-Baitar’s Comprehensive Book of Simple Medicines and Foods, dated about 1245, which was not translated to Latin in the medieval era but was published in the 19th century in German, French, and Arabic – an Arabic copy is at Al-Mostafa.com and at AlWaraq.net.

- ^ «Les Noms Arabes Dans Sérapion, Liber de Simplici Medicina«, by Pierre Guigues, published in 1905 in Journal Asiatique, Series X, tome V, pages 473–546, continued in tome VI, pages 49–112.

- ^ Analysis of herbal medicine plant-names by Martin Levey reported by him in «Chapter III: Botanonymy» in his 1973 book Early Arabic Pharmacology: An Introduction.

- ^ Each discussed in Etymologisches Wörterbuch der botanischen Pflanzennamen, by Helmut Genaust, year 1996. Another Arabic botanical name introduced by Prospero Alpini from Egypt was Sesban meaning Sesbania sesban from synonymous Arabic سيسبان saīsabān | saīsbān (Lammens 1890; Ibn al-Baitar). The Latin botanical Abrus is the parent of the chemical name Abrin; see abrine @ CNRTL.fr. The Arabic لبلاب lablāb means any kind of climbing and twisting plant. The Latin and English Lablab is a certain vigorously climbing and twisting bean plant. Prospero Alpini called the plant in Latin phaseolus niger lablab = «lablab black bean». Prospero Alpini published his De Plantis Aegypti in 1592. It was republished in 1640 with supplements by other botanists – De Plantis Aegypti, 1640. De Plantis Exoticis by Prospero Alpini (died 1617) was published in 1639 – ref.

- ^ A list of 43 of Forsskål’s Latinized Arabic fish names is at Baheyeldin.com/linguistics. Forsskål was a student of Arabic language as well as of taxonomy. His published journals contain the underlying Arabic names as well as his Latinizations of them (downloadable from links at the Wikipedia Peter Forsskål page).

- ^ Most of those miscellaneous botanical names are discussed in Etymologisches Wörterbuch der botanischen Pflanzennamen, by Helmut Genaust, year 1996. About half of them are in Dictionnaire Étymologique Des Mots Français D’Origine Orientale, by L. Marcel Devic, year 1876. The following are supplemental notes. The names argel and seyal were introduced to scientific botany nomenclature from الحرجل harjel and سيال seyāl in the early 19th century by the botanist Delile, who had visited North Africa. Retama comes from an old Spanish name for broom bushes and the Spanish name is from medieval Arabic رتم ratam with the same meaning – ref, ref. Acerola is from tropical New World Spanish acerola = «acerola cherry» which is from medieval Spanish and Portuguese acerola | azerola | azarola = «azarole hawthorn» which is from medieval Arabic الزعرور al-zoʿrūr = «azarole hawthorn» – ref, ref. Alchimilla appears in 16th century Europe with the same core meaning as today’s Alchemilla (e.g.). Reporters on Alchemilla agree it is from Arabic although they do not agree on how.

- ^ In late medieval English, chamelet | chamlet was a costly fabric and was typically an import from the Near East – MED, NED. Today spelled «camlet», it is synonymous with French camelot which the French CNRTL.fr says is «from Arabic khamlāt, plural of khamla, meaning plush woollen cloth…. The stuff was made in the Orient and introduced to the Occident at the same time as the word.» The historian Wilhelm Heyd (1886) says: «The [medieval] Arabic khamla meant cloth with a long nap, cloth with a lot of plush. This is the common character of all the camlets [of the late medieval Latins]. They could be made from diverse materials…. Some were made from fine goat hair.» – Histoire du commerce du Levant au moyen-âge, Volume 2 pages 703–705, by W. Heyd, year 1886. The medieval Arabic word was also in the form khamīla. Definitions of خملة khamla | خميلة khamīla, and the plural khamlāt, taken from medieval Arabic dictionaries are in Lane’s Arabic-English Lexicon page 813 and in the Lisan al-Arab under خمل khaml Archived 29 October 2013 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ The English word morocco, meaning a type of leather, is a refreshed spelling of early 16th-century English maroquin, from 15th-century French maroquin meaning a soft flexible leather of goat-skin made in the country of Morocco, or similar leather made anywhere, with maroquin literally meaning «Moroccan, from Morocco». Maroquin @ NED, morocco @ NED, maroquin @ CNRTL.fr, FEW XIX.

- ^ Fustic in the late medieval centuries was a dye from the wood of a Mediterranean tree. After the discovery of America, a better, more durable dye from a tree wood was found, and given the same name. The late medieval fustic came from the Rhus cotinus tree. «Rhus cotinus wood was treated in warm [or boiling] water; a yellow infusion was obtained which on contact with air turned into brown; with acids it becomes greenish yellow and with alkalies orange; in combination with iron salts, especially with ferrous sulphate a greenish-black was produced.» – The Art of Dyeing in the History of Mankind, by Franco Brunello, year 1973 page 382. The earliest record of the word as a dye in the Western languages is in 13th-century Spanish as «fustet», followed by 14th-century French as «fustet» and «fustel» – CNRTL.fr, DMF. Medieval Spanish had alfóstigo = «pistachio», medieval Catalan festuc = «pistachio, which were from Arabic فستق (al-)fustuq = «pistachio». Medieval Arabic additionally had fustuqī as a color name, yellow-green like the pistachio nut (e.g.), (e.g.), (e.g.). Many dictionaries today report that the Spanish dye name somehow came from this medieval Arabic word. But the proponents of this idea do not cite evidence of fustuq carrying the dye meaning in Arabic. The use of the word as a dye in medieval Arabic is not recorded under the entry for fustuq in A Dictionary of Andalusi Arabic (1997) nor under the entries for fustuq in the medieval Arabic dictionaries – Lane’s Arabic-English Lexicon, page 2395, Baheth.info Archived 29 October 2013 at the Wayback Machine. This suggests that the use of the word as a dye may have started in Spanish. From a phonetic angle the medieval Spanish and French fustet is a diminutive of the medieval Spanish and French fuste = «boards of wood, timber», which was from classical Latin fustis = «wooden stick» – DRAE, Du Cange. From the semantic angle, since most names of natural dyes referred to both the plant that produces the dye and the dye itself, fustet meaning «little pieces of wood» can plausibly beget the dye name fustet. The semantic transformation from «pistachio» to «fustic dye» is poorly understood, assuming it happened. New English Dictionary on Historical Principles (year 1901) says «the name was transferred from the pistachio [tree] to the closely allied Rhus cotinus«. But the two trees are not closely allied.

- ^ «Carthamin» and «Carthamus» in New English Dictionary on Historical Principles (year 1893). Similarly summarized in CNRTL.fr (French) and Diccionario RAE (Spanish). For the word in medieval Arabic see قرطم @ Baheth.info Archived 29 October 2013 at the Wayback Machine (see also عصفر ʿusfur), قرطم @ Ibn al-Awwam and قرطم @ Ibn al-Baitar.

Introduction

Fiction is one of the most ancient and effective non-verbal methods representing the national flavor of a particular culture. Even if we take into account that any work of fiction is translated so that it could be perceived by a bearer of another culture (language), and some of the unique lexical features may be lost or unreliable, cultural realities, despite this, are still reflected in the text (Hock, 1996). This is due primarily to the fact that any national culture is based on its own unique picture of the world, which in turn is inextricably linked with the history of the people. Despite the fact that most of the lexical units from the Arabic language penetrated into English naturally — through cultural contacts and assimilation of Arabic and European speakers, literature also contributed to this process.

This article is based on the context analysis of words of Arab origin from the famous work of “One Thousand and One Nights.” This work was chosen as an object of research, because it is the result of not only one author-representative of the Arab culture, but in fact, it is folk art. Various researchers put forward different theories about the origin of this storybook, but they failed to come to agreement or identify a specific author (Adzieva, 2014: 17). “One Thousand and One Nights” is a collection of ancient eastern folk tales, compiled around the time of the Golden Age of Islam (8-14th c.). This collection is also known as “Arabian Nights” according the very first translation into English. The history of the “Arabian nights” is complex and confusing. Many scientists have tried to trace the path that this book has gone since its origin until nowadays [Fassler, 8].

The very first European version was the translation into French (1704-1717) by Anthony Galland (Anchi, 2017). These translations were based on the Syriac version of the Arabic text. A curious moment was that Galland also included in his collection such tales as “The Lamp of Aladdin” and “Alibaba and the Forty Thieves”, which first appeared in his translation, but were not in the original version of the manuscript. Later, another translation by Edward Lane (1840, 1859) appeared. This version of the translation is still considered one of the classic translations of the “Arabian Nights,” since it was as close as possible to the original, in contrast to the translations of Galland (Salye, 2009).

In 2008, Penguin Classics released a new version of the three-volume story collection. In addition to the original text of the book “One Thousand and One Nights”, this edition contains the stories of Aladdin, Ali Baba, as well as an alternative ending to “Seven Adventures of Sinbad” from a translation by Anthony Galland.

This version of translation was taken as the basis of the analysis of Arabisms in the text, since it is more consistent with modern lexical norms.

Main part

The main purpose of this study is an attempt to trace and conduct an etymological analysis of words of Arabic origin in English in the context of fiction. In this regard, we selected 15 lexical units of Arabic origin representing various semantic fields.

-

Giraffe

“The Muslims pursued them with their Indian swords and only a few of the elephants and giraffes escaped.” (Lyons, 2008: night 664)

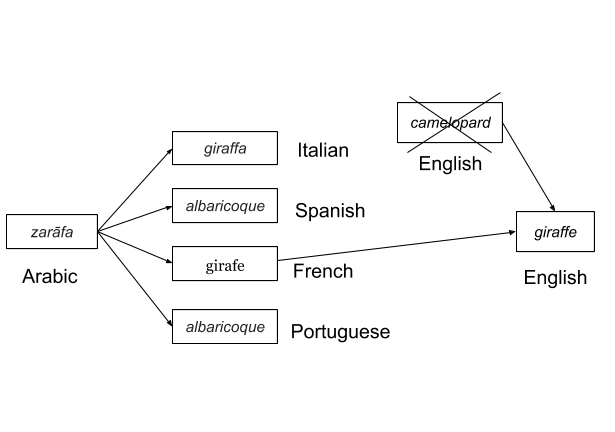

This designation of the animal comes from the Arabic “zarāfa”. Apparently, it came to Arabic from African languages. Around the end of the 16th century this designation appears in Italian — “giraffa”, Spanish and Portuguese — “girafa”, and in French — “girafe”. And also, around this period, apparently, it was borrowed from French by the English language.

An interesting fact is that before this word was borrowed by English, this animal was called Camelopard. (Abbreviation from the Greek Camelopardalis). The combination of Camelos “Camel”, because of the long neck and pardos “Leopard” (panther), because of spots on the body (Onions, 2003).

Figure 1

The way of borrowing of the word “giraffe” by English

-

Apricot

“There were fruit trees with two types of every fruit, pomegranates sweet and sour on the branches, almond-apricots, camphor-apricots and Khurasanian almonds, plims intertwined in the branches of ban trees, oranges gleaming like fiery torches, citrons weighing down the branches, lemons, the remedy for loss of appetite, sorel, which cures jaundice, and dates, red and yellow, on their parent trees, the creation of the Lord on high.” (Lyons, 2008: night 630)

This example illustrates a number of fruit names. Three of them have Arabic roots.

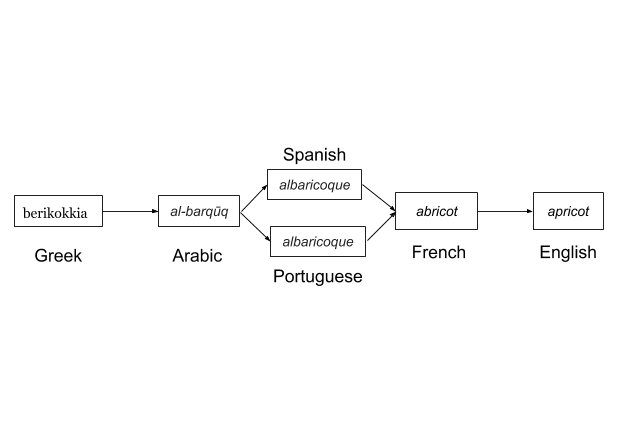

Typically, words of Latin origin travel from Latin to French, and then end up in English. However, the “apricot” made a short southward detour. Initially, among the Greeks, this fruit sounded like “berikokkia.” Then the Arabs borrowed this word, adding the article and it turned into “al-burquq.” Thanks to the Arabic presence in Spain (711-1492 a.d.), the borrowing came into Spanish in the form of “albaricoque.” Then in French — “abricot.” This word first came to English in the form of “abrecock,’ but over time (probably influenced by the French) the sound “ck” changed to “t” and the word (1300 a.d.) acquired a modern look, used to this day (Online etymology dictionary, 2020).

Figure 2

The way of borrowing of the word “apricot” by English

-

Orange

It is established that the roots of the name of this fruit date back to Sanskrit — “naranga-s” (orange-tree). Then the Persians borrowed it in the form of “Narang.” In this form, it fell into the Arabic language — “nāranj.” Only from the old French — “Orenge,” in English it acquired a modern form of “Orange.” It has been used as an adjective for color since about the 1540s. Prior to this, words like citrine or saffron were used to describe the orange color. The first use of the phrase Orange juice dates back to 1723 (Online etymology dictionary, 2020).

Figure 3

The way of borrowing of the word “orange” by English

-

Lemon

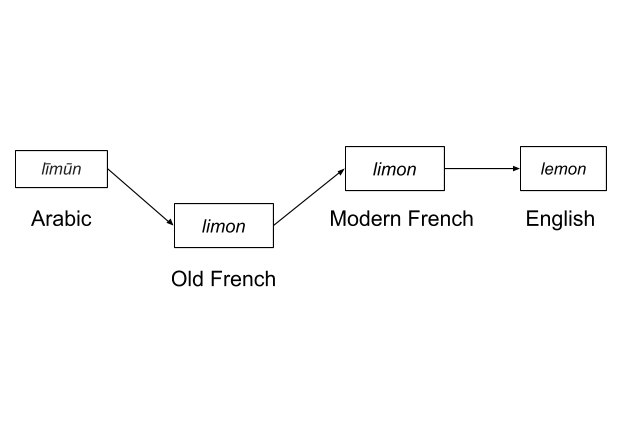

In Arabic, the word “līmūn” means a common name for all fruits of this type. Around the 14th century, this word was borrowed by the Old French — “limon.” In modern French, this token is also present, but has changed its meaning and today limes are called by this term (Online etymology dictionary, 2020).

Figure 4

The way of borrowing of the word “lemon” by English

-

Chemistry

“He won renown for the depth of his knowledge of medicine, astronomy, geometry, astrology, chemistry, natural magic, and the spiritual sciences, as well as others.” (Lyons, 2008: night 535)

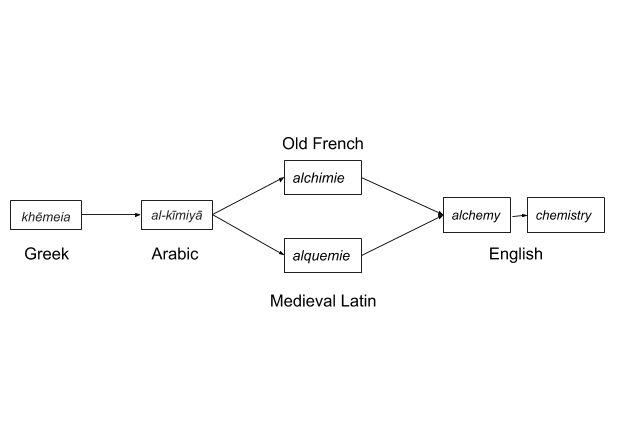

Oddly enough, regarding the etymology of the word chemistry, there is still no clear answer. Scientists only agree that this word comes from “alchemy,” which in turn was borrowed from the Arabic “al-kīmiyā,” where “al” is the Arabic definite article, and the root of the word comes from the ancient Greek — “khemeioa.” The first mention dates back to about the 300th year a.d. There is an assumption that the roots of the word go back to the ancient name of Egypt — Khemia, which literally means — black earth (Hoad, 1996).

Figure 5

The way of borrowing of the word “chemistry” by English

-

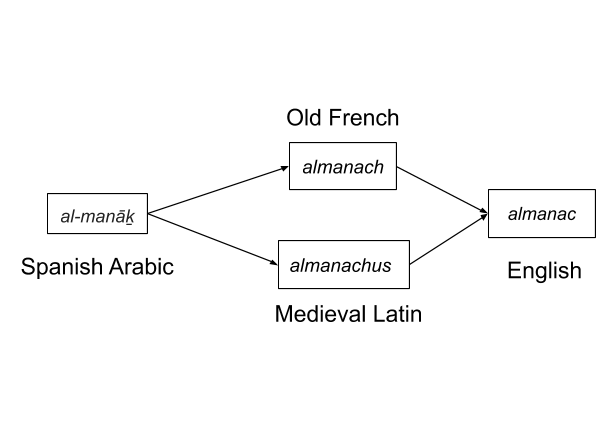

Almanac

“One day he summoned men of learning, astrologers, scientists, and almanacexperts and told them to examine his horoscope to see whether God would grant him this wish.” (Lyons, 2008: night 499)

The meaning of the word Almanac is interpreted as a collection of astronomical data. Presumably, the roots of this word date back to the Spanish-Arabian times of the conquest of the Iberian Peninsula by the Arabs (14th century), and meant “calendar.” (Smith, 2007)

Figure 6

The way of borrowing of the word “almanac” by English

7)Camphor

“Whoever wants to get some camphor must use a long tool to bore a hole at the top of the tree and then collect what comes out.” (Lyons, 2008: night 545)

According to the Oxford Dictionary, camphor is a white substance with a strong odor used in medicine as well as in the manufacture of plastic and in order to drive insects away from fabric clothing. This substance is obtained from trees in East Asia and Indonesia (Fassler, 2013). The etymology of this word has come a long way from Sanskrit — “karpūra,” where it literally meant “the camphor tree”, then, through the Malaysian, it was borrowed from Arabic, slightly changing its phonetic characteristics — “kāfūr.” And subsequently, around the 14th century, it came to English through French and Latin (Merriam-Webster: 2019).

Figure 7

The way of borrowing of the word “camphor” by English

8)Assassin

“On the fourth day he appeared before the Khalfah, who asked him for the murderer. ‘Can I see the invisible or search out the hidden?’ answered Jafar. ‘Can I find an unknown assassin in a whole cityful of people?” (Lyons, 2008: night 119)

The origin of this word comes from the territory of modern Lebanon during the Crusades. According to the most common theory, a sect of Muslim fanatics led by Hassan-i Sabbah has settled in these mountains. This group of people was famous for the fact that they killed the leaders of the hostile clans under the influence of hashish (a cannabis-based narcotic substance). In Eastern Europe, they were assigned such a reputation around the 12-13th centuries (Dahler, 2013).

The word itself comes from the Arabic “hashīshīn” (the one who uses hash). The term was spread in Italy at the beginning of the 14th and 15th centuries — “Assissini”. In the middle of the 16th century, the word entered the French language, later it was borrowed by English.

Figure 8

The way of borrowing of the word “assassin” by English

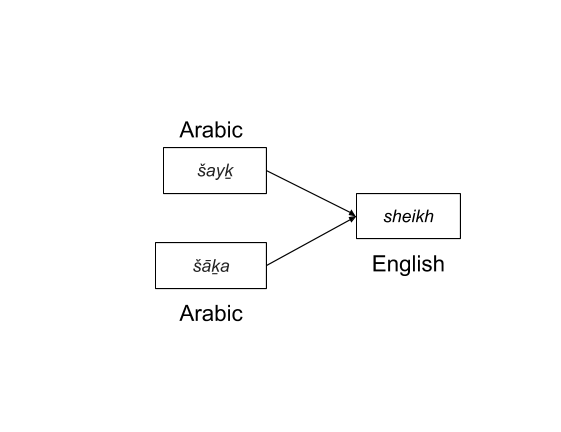

9) Sheikh

“And the sheikh, master of the gazelle, being greatly astonished, said: ‘By Allah, your faith, my brother, is indeed a rare faith!” (Lyons, 2008: night 487)

The literal meaning of the Arabic “sheikh” (šayḵ) is translated as “old man”. While the word itself comes from the verb “šāḵa”, which means “to get older, grow old”. In the records dated to the 1570s it is found in the meanings: “head of the Arab family”, as well as “head of the Muslim religion”. The word gained universal fame in the English-speaking society after the publication of the novel in the Arabic setting of the British writer Edith Maud Hall “The Sheikh” in 1919. A movie version of the book under the same title soon followed (Cannon, 1994). The main role was played by Rudolf Valentino, thanks to whom in the 1920s everyone associated this word with a “strong and romantic Arabian lover”. Nowadays, the meaning of the word is closer to its original and usually refers to the «ruler of the tribe», «member of the royal family.» Usually, this title is awarded to a newborn man in the royal family.

Figure 9

The way of borrowing of the word “sheikh” by English

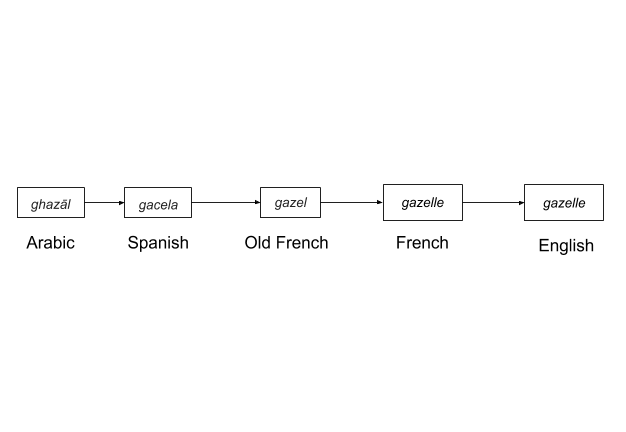

10) Gazelle — any of the many species of antelopes. The main habitat of these animals is the deserts, meadows, and savannahs of Africa. They can also be found in central Asia and in the south of the Indian peninsula.

The borrowing of this word in English dates from about 1600. Presumably, it was based on the northern Arabic pronunciation — “Ghazal” and passed into Spanish like “gacela” and Old French “gazel” in the 14th century (Merriam-Webster, 2019). After a while, the word began to be used in English.

Figure 10

The way of borrowing of the word “gazelle” by English

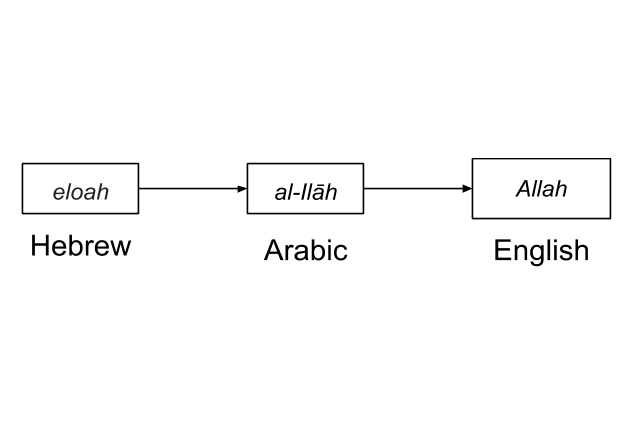

11) Allah

In the Muslim religion, the word Allah (Allāh) refers to the meaning of the one God. Etymologically, the term is supposedly a modified construction of “al-Ilāh” — “God” (lit.). The origin of the word may refer to the earliest Semitic writings, in which the words in the meaning of God looked like: “il”, “el” and “eloah”. The last two are even found in the Hebrew Bible. The word “Allah” has a strong association with the Islamic religion because of the special status of the Arabic language in the Quran — the holy scripture of Islam. It is believed that the original language in which the text of the Quran was written by the hand of God is Arabic. Thus, for Muslims, the Arabic language is of particular importance (Cannon, 1994).

Figure 11

The way of borrowing of the word “Allah” by English

12) Sugar.

“…I have a guiltless love, dear lad,

Which I should hide although you had

Thrown all the sweetness in eclipse

Of a thousand China trading ships

With the lithe verses of your hips

And the sugar of your lips.” (Lyon, 2008: night 112)

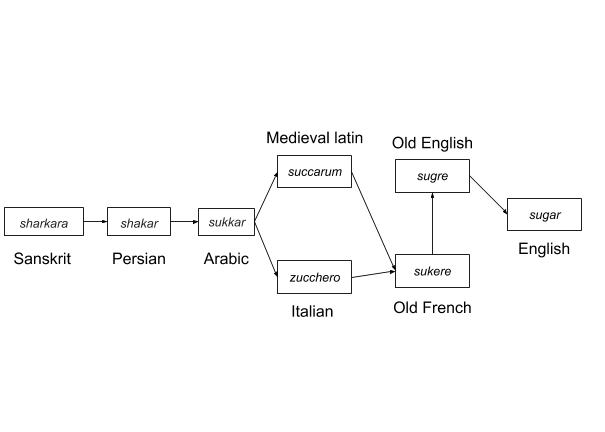

It is generally accepted that the word comes from the Arabic “sukkar”. However, it is assumed that its ancestors originated from Persian and Sanskrit. Around the 12th century, the word is borrowed from the medieval Latin “succarum” and the old French “sucre”. Soon after it came into use of the Old English language (13th century), the word had the form “sugre”, but subsequently it took on that modern form in which we now know it (Darwish Hosam, 2015: 108).

Sugar was exotic for medieval Europe until the moment the Arabs began to cultivate it in Sicily and Spain. Subsequently, many European languages adopted it with minimal phonetic changes.

Figure 12

The way of borrowing of the word “sugar” by English

13)Mattress

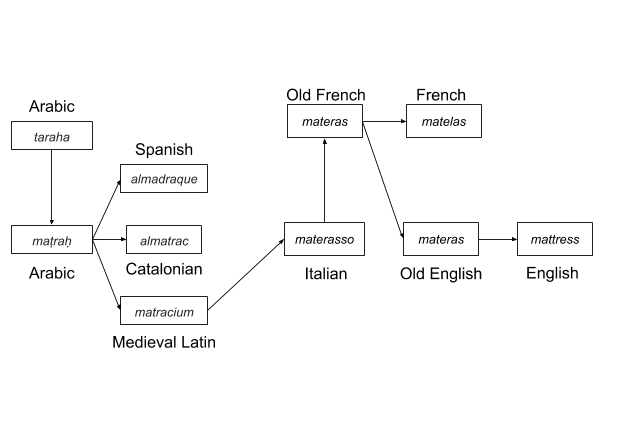

“After a long conversation, he brought out a mattress and a quilt for me, and let me sleep that night in a corner of his shop.” (Lyons, 2008: night 785)

The word “mattress” comes from the Arabic verb “taraha”, which means “he threw (down)” with the addition of the noun prefix “ma-”. Then, in combination with the Arabic definite article, presumably at the beginning of the 12th century in the territory of Sicily, this word was borrowed by the Catalan (almatrac), Spanish (almadraque) and the medieval Latin (matracium), which literally means “a thing thrown under your feet”. Subsequently, the term appears in Italian (materasso) and in the ancient French (materas).

The first mention of this word in English dates from around the beginning of the 14th century, where the word was borrowed directly from French and had the same spelling. Obviously, over the time, it acquired a modern look and meaning — a component of the bed, in the form of a bag filled with soft and resilient material (Onions, 2003).

Figure 13

The way of borrowing of the word “mattress” by English

14)Massage

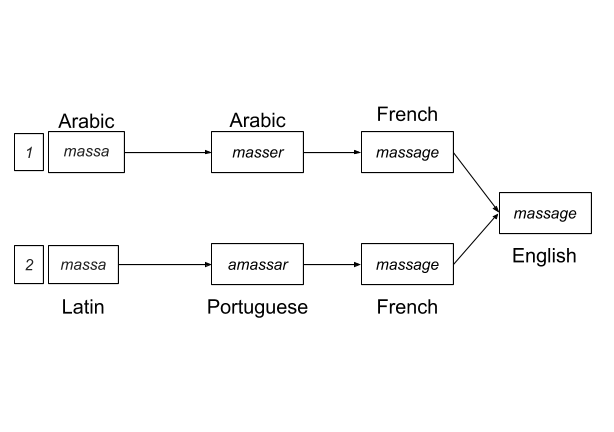

“After a few moments of consideration, the old man covered the faces of the sleepers and, sitting on the ground before them, began to massage the feet of Ali-Nur, for whom he had taken a sudden liking.” (Lyons, 2008: night 445)

Regarding the origin of the word “massage”, there are two main theories. According to both of them, the word came into English from French, however, according to the first theory, the word came into French from colonial India, where the Portuguese used the word “amassar” (knead), which in its turn came into Portuguese from the Latin “massa” (mass, dough).

The second version involves borrowing the word by French from the Arabic “masser” (to massage), which comes from the verb “massa” (touch, feel) (Smith, 2007). Thus, the French could borrow this word during the Napoleonic military campaign in Egypt. This word begins to spread since 1819, in the meaning of «knead». It gained its modern interpretation a little later, in 1874.

Figure 14

The way of borrowing of the word “massage” by English

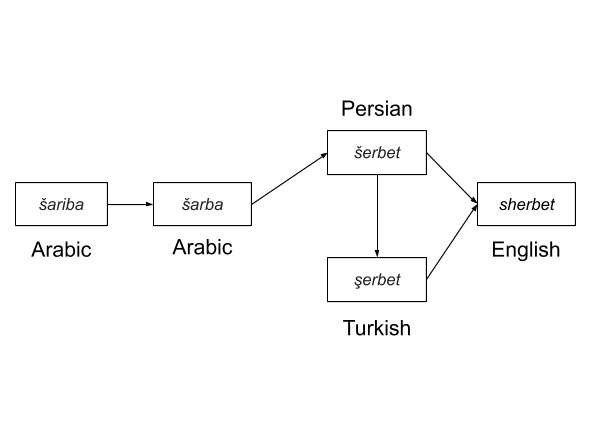

15) Sherbet

“Then she dressed him in clean clothes belonging to her husband, made him drink a glass of delicious sherbert, and sprinkled his face with rosewater.” (Lyons, 2008: night 501)

Despite the fact that the word “sherbet” has been present in the English language for several centuries, its meaning has changed over time and differs from the modern interpretation. This word got into English directly from the Turkish language of the Ottoman Empire (šerbet) and Persia (šarbat), meaning a traditional Middle Eastern sweet drink diluted with fruit syrup or juice. The word came into Turkish from Persia, and the Persian people had borrowed from Arabic (šarba), which literally means “drink”, which in turn is formed from the verb “to drink” (šariba). By the way, the solid “t” at the end of the word appeared due to the peculiarities of Turkish and Persian Arabic pronunciation (Abu Ghosha, 1977: 112).

The drink spread very quickly in eastern Europe at the beginning of the 16th century. Although, in English, the first mentions date back to the beginning of the 17th century, this drink was probably known even earlier. Throughout the 19th century, sherbert was used to mean a cool sweet drink with the addition of effervescent tasty powder, although nowadays, in Britain in particular, sherbert will most likely mean something like candy or powder that is eaten by dipping a finger into it. It is worth noting that even in the modern language there are several forms of the word. So, for example, sherbet (pronounced “sher-but”) and sherbert (pronounced sher-bert) have the same meaning, although the “sherbert” variant is less used. The modern American interpretation distinguishes between the words “sherbet” and “sorbet”. Sherbet is more like ice cream with milk and fruit, while sorbet has a simpler composition of ice and fruit juice (Bale, 2006).

Figure 15

The way of borrowing of the word “sherbert” by English

Materials and methods

The basis of this article were the work “One Thousand and One Nights” (translated into English by Anthony Galland), various etymological dictionaries, such as: Merriam-Webster Online dictionary, The Oxford Dictionary of English Etymology, Online Etymology Dictionary, as well as articles and works of some famous researchers such as Jassem Z., Bale J., Adzieva E., Smith A.

Results and conclusion

We made a random sampling of English words with Arabic roots, in particular: giraffe, apricot, orange, lemon, chemistry, almanac, camphor, assassin, sheikh, gazelle, Allah, sugar, mattress, massage, sherbert. According to scientists, in the English language, there are about 170 borrowings from the Arabic language (Smith, 2007). About 50 of them came to English directly from Arabic, while the rest were derived through other languages. Based on the analysis, we were able to find out that only two words from the above list — Sheikh and Allah, were borrowed directly from Arabic. Another one — sherbet, first came to Turkish, and only then to English. The rest, for the most part, became common in French and only after that they came into English. This is explained, firstly, by the fact that the south of Europe, in particular Spain, was heavily influenced by Muslim culture for several centuries. Another reason why the French language has absorbed so many Arabic words is, of course, the Crusades, the initiative of which came largely from the French crusaders of the time. As a result, we can conclude that most of the Arabisms were borrowed by the English language not directly, but through other European languages and, in particular, French.

Arabic is the fifth most spoken language in the world, with an estimated 315 million native speakers.

It’s also one of the most ancient, varied and beautifully scripted languages in existence.

Its influence on Spanish since the time of the Moors is well known, but what’s less well known is how many commonly used English words were actually taken from Arabic.

Here are just thirteen.

1. Alcohol

One of the most important words in the English language actually comes from the Arabic al-kuhl, (the kohl) which is a form of eyeliner.

Because the cosmetic was made via an extraction process from a mineral, European chemists began to refer to anything involving extraction/distillation as alcohol.

And that’s how the «alcohol of wine» (i.e. the spirit you get from distilling wine) got its name.

Sign up to our new free Indy100 weekly newsletter

2. Algebra

From the Arabic al-jabr, which describes a reunion of broken parts, the use of the term came from a 9th century Arabic treatise on math.

The author’s name was al-Khwarizmi, which became the mathematical term algorithm.

3. Artichoke

The classical Arabic word, al-harshafa, became al-karshufa in Arabic-speaking Spain.

It has been adopted into French as artichaut, Italian as carciofo, Spanish as alcachofa, and English as artichoke.

4. Candy

Qand refers to crystallised juice of sugar cane, which is where Americans derive their word candy.

It originally came from Sanksrit, and was adopted into Arabic via the Persian language.

5. Coffee

Arabia originally got coffee from eastern Africa and called it qahwah.

Then it went to Turkey — kahve.

Then the Italians — caffè.

And finally, it arrived in Britain as coffee.

6. Cotton

The word is derived from the Arabic qutn.

7. Magazine

This word is derived from the Arabic makzin, which means storehouse.

We got it from the French (magasin, meaning shop), who got it from the Italians (magazzino), who got it from the Arabic.

8. Mattress

Sleeping on cushions was actually an Arabic invention.

Were it not for Arabic matrah, a place where the cushions were thrown down, the Europeans would never have adopted materacium/materatium (Latin) which passed through Italian into English as mattress.

9. Orange

Originally from South and East Asia, oranges were known in Sanskrit as naranga.

This became the Persian narang, which became the Arabic naranj.

Arabic traders brought oranges to Spain, which led to the Spanish naranja.

Then it went into old French as un norenge, then new French as une orenge.

Then we took it from the French and it became orange.

10. Safari

Safari is the Swahili word for an expedition, which is how it has become so associated with African bush and game tourism.

However, that Swahili word came from the Arabic safar, which means journey.

11. Sofa

The Arabic word suffa referred to a raised, carpeted platform on which people sat.

The word passed through the Turkish language to join English as sofa.

12. Sugar

Arabic traders brought sugar to Western Europe, calling it sukkar (originally from the Sanskrit sharkara).

And last but not least…

13. Zero

Italian mathematician Fibonacci introduced the concept of zero to the Europeans in the 13th century.

He grew up in North Africa, and learned the Arabic word sifr, which means empty or nothing.

He Latinised it to zephrum, which became the Italian zero.

Because Roman numerals couldn’t express zero, he borrowed the number from Arabic.

Now, all our digits are known as Arabic numerals.

H/T: The Week

Enjoyed this article? Then click the upvote icon at the top of the page to help it rise through the indy100 rankings and have your say in our news democracy.

Did you know that Arabic has influenced other languages like English, Spanish, and French? Of course, one could totally understand how Arabic has had a major linguistic influence on other non-Arab Islamic countries. For example, in countries like Pakistan, Turkey or Iran, Arabic is the only language of the Quran. So, naturally, the influence of the Arabic language was strong there. This is due to the fact that Islam is the main religion.

So, how did Arabic expand its influence so deep into the languages of the West? When the Islamic Empire grew into the Mediterranean region, Arabic became hugely influential. This happened sometime between the 8th and 12th centuries.

The following are the top three languages that contain some words from Arabic.

Influence of Arabic on English

English borrowed some words from Arabic through other European languages. Also, words were transmitted by soldiers returning home from the crusades. However, one thing needs to be noted. The Arab world was a great global contributor to the sciences of astrology, alchemy, mathematics and medicine. Therefore, it was only natural that some of the technical terms are borrowed words in English, but not limited to only those technical terms.

| English | Transliteration | Arabic |

|---|---|---|

| Sugar in Arabic | sukkar | سكر |

| Cotton in Arabic | qutn | قطن |

| Algebra in Arabic | al-jabr | الجبر |

| Alcohol in Arabic | al-kuhul | الكحول |

| Cave in Arabic | kahif | كهف |

| Gazelle in Arabic | ghazal | غزال |

| Lemon in Arabic | limun | ليمون |

| Guitar in Arabic | ghytar | غيتار |

Influence of Arabic on Spanish

Spanish has borrowed many words from the Arabic language due to 800 years of Arab dominion in the region. Arabic seems to have a bigger impact on the Spanish language called Catalan than on any of the Spanish dialects. The Arabs even called the Iberian Peninsula as al-andalus. Also, this word exists even in present-day Spain to denote a community there where the people are known as the Andalusians.

| English | Spanish | Translation | Arabic |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aubergine in Arabic | albergínia | badhanjan | باذنجان |

| Bathrobe in Arabic | barnús | barns alhamam | برنس الحمام |

| Olive in Arabic | aceituna | zaytun | زيتون |

| Waterwheel in Arabic | nòria | naeura | ناعورة |

| Artichoke in Arabic | cachofa | kharshuf | خرشوف |

Influence of Arabic on French

At some point, France colonized the region known as Maghreb. The region is in the north-west area of Africa. Consequently, French became the second language. So, it was only natural that some Arabic words permeated the language.

| English | French | Transliteration | Arabic |

|---|---|---|---|

| Apricot in Arabic | abricot | albarquq | أَلْبَرْقُوق |

| Magistrate in Arabic | alcade | alqadi | القاض |

| Tariff in Arabic | tariff | taerifa | تعريفة |

Technically speaking, any Romance language will have Arabic influences due to conquering of the European empires within the region. You can find words of Arabic even in the Romanian, Portuguese, German and Italian languages.

We at kaleela.com believe that the study of languages can be fascinating as you learn how they came about, how they influenced other regions and how they have evolved over time. Surely, we can all agree that the Arabic language has made great contributions to other languages, cultures and sciences.

If you want to learn more about the Arabic language, don’t forget to download our Arabic learning app Kaleela!

Top 50+ English Words—of Arabic Origin!

Posted by on Feb 21, 2012 in Arabic Language, Culture, Vocabulary

Did you know that words like Adobe and Safari are actually Arabic?

Of course, you already knew of the existence of so-called “loanwords” in English, meaning words which are originally French, German, Spanish, etc.

But were you actually aware that several of them also come from ARABIC?

IN SCIENCE AND MATH:

- ALCHEMY and CHEMISTRY (الكيميـــــــــاء.)

- ALCOHOL (الكُحُـــــــــول.)

- ALGEBRA (الجبــر: More on the eponymous founder of Algebra as an independent mathematical discipline here.)

- ALGORITHM (خوارزم: More on the eponymous founder of algorthimics here.)

- ALKALINE (القلوي: Meaning “non-acid, basic.”)

- ALMANAC (المنــــــاخ: Literally meaning “climate”)

- AVERAGE (From Old French avarie, itself from the Arabic term عوارية, meaning “damaged goods”, from عور meaning “to lose an eye.”)

- AZIMUTH (السمــــــــت: This concept is used in several fields, such as الفلك/astronomy، هندسة الطيران/aerospace engineering، and فيزياء الكم/quantum physics.)

- CIPHER (صِفـــــــــــــــــــــــــــر: The term “cipher” is now mostly applied in cryptography—see الكَندي/Al-Kindi’s work.)

ELIXIR (الإكسيــــــــــــــر: Something like a “syrup”—also an Arabic term, possibly borrowed from Persian.)

- NADIR (نظيـــــــــــــر: It is the opposite of the zenith.)

- SODA (صـــــــــودا.)

- ZENITH (سمت الرأس: Literally the “azimuth of the head”، it is the opposite of the “nadir.”)

- ZERO (same as “cipher.”)

Names of many stars and constellations:

(Altair: الطَّائـــــــــر meaning “the bird”; Betelgeuse: بيت الجــــــوزاء, meaning “the House of the Gemini”; Deneb: ذنب meaning “tail”; Fomalhaut: فم الحوت which means “the mouth of the Pisces”, Rigel: رِجـــــــل meaning “foot”, it stands for رجل الجبَّار, or the “foot of the Titan”, Vega: الواقع meaning “the Falling”, refers to النسر الواقع، meaning “the falling eagle”, etc.)

- An entirely separate post is necessary to list all of the astronomical terms which are of Arabic origin.

TECHNICAL TERMS (ENGINEERING, MILITARY, BUSINESS, COMMODITIES, etc.)

- ADMIRAL (أميــــــــر الرحلة, meaning commander of the fleet, or literally “of the trip”)

- ADOBE (الطوب: meaning a “brick.” Next time you use an Adobe Acrobat product, you will remember that Adobe is originally Arabic!)

- ALCOVE (القبة: meaning “the vault”, or “the dome”)

- AMBER (عنبر: Anbar, “ambergris.”)

- ARSENAL (Do fans of F.C. Arsenal today, including those living in the Arab world, know where the name of their favorite team came from? دار الصناعــــــــــــــــة : “manufacturing house”)

- ASSASSIN (Just like the word MAFIA, it is of Arabic origin: It either comes from “حشَّــــــــــــــاشين”, referring to the medieval sect of the same name famous for the heavy hashish consumption by its knife-wielding members, or “العسَّاسيــــــــــــــــن”, meaning “the watchmen.”)

- CALIBER (قـــــــالب: meaning “mold”)

- CANDY (from قندي, itself from Persian for “hard candy made by boiling cane sugar”)

- CHECK (from صکّ, also from Persian meaning “letter of credit.” It would give the Chess expression “Checkmate”, from “الشيخ مات”, or “the Shaikh is dead.”)

- CORK (القورق)

- COFFEE (قهوة: For long snubbed by Europeans as the “wine of the infidels”—that is, many centuries before the age of Starbucks and instant coffee!)

- COTTON (قُطْـــــــــن)

- GAUZE (either from قَــــــــــزّ, meaning “silk”, or from غَــــــــزّة, “Gaza”, the Palestinian city.)

- GUITAR (just as LUTE, العود, a musical instrument known to Europeans through the Arabic قيثارة, itself possibly borrowed from a word of Ancient Greek.)

- HAZARD (الزّهر: “the dice”—Think of an Arabic TV series hazardly titled “The Dukes of Al-Azhar”…)

- LAZULI (As in “Lapis Lazuli”, لاژورد: Arabic word for a semi-precious stone famous for its intense blue color. The Arabic word is said to come from a Persian city where the stone was mined.)

- MASCARA (Just as with the English “masquerade” and the French “mascarade“, mascara comes from the Arabic word مسخرة, an event during which people wear masks, such as carnivals.)

- MATTRESS (مطـــــــــــــــــــرح.)

- MONSOON (موسم: Arabic for “season.”)

- MUMMY (مومياء: Originally from Persian root “موم”, meaning “wax”.)

- RACQUET (As in a “tennis racket”. Some point to an Arabic origin of Tennis. The word racket comes the Arabic word “راحـــــــة”, as in “راحـــــة اليد”, meaning the “palm of the hand.”)

- REAM (as in a “ream of paper”, it comes from Arabic رزمة, meaning a “bundle.”)

- SAFARI (سفـــــــر: “travel”—As in Apple’s Safari web browser)

- SASH (شــــــــاش.)

- SATIN (زيتــــــــــــوني: “Olive-like”, perhaps related to modern Tsinkiang in Fukien province, southern China.)

- SOFA (الصُفــــــــة)

- TALCUM (التلك)

SWAHILI (Comes from سواحــــــــــل: Plural of ساحــــــــــل, meaning a “coast.”)

- ZIRCON (زرقـــــــــــــون: “golden-colored.” Zirconium is a chemical element with the symbol Zr and atomic number 40)

- TARIFF (تعاريـــــــــــــــف, plural of تعريـــــــــــــــفة, meaning a “fee”, or simply تعريـــــــــــــــف, as in “بطاقــــــــة التعريـــــــــــــــف“, meaning an “identity card.”)

Finally, to close this list, it is fitting to greet everyone by saying “SO-LONG” (an English expression which, according to The Penguin Dictionary of Historical Slang, may come from the Arabic word ســـــــــــــــــــــــلام/SALAAM!)

Tags: admiral, adobe, adobe acrobat, alchemy, alcohol, alcove, algebra, algeria, algorithm, alkaline, almanac, altair, altair ibn-la’ahad, amber, arabic loanwords, arsenal, assassin, assassin’s creed, average, azimuth, beetlejuice, betelgeuse, caliber, candy, chemistry, cipher, deneb, elixir, f.c. arsenal, fomalhaut, french, gauze, gaza, german, guitar, hazard, lapis lazuli, lazuli, lute, lyes salem, mafia, mascara, mascarades, masquarade, mattress, merzak allouech, monsoon, mummy, nadir, obama, racquet, rais hamidou, ream, rigel, safari, sash, satin, soda, spanish, street fighters, swahili, talcum, tariff, tunisia, vega, zenith, zero, zircon, zr, أميــــــــر الرحلة, الإكسيــــــــــــــر, الجبــر, الرايس حمِّيـــــــــــدو, الزّهر, السمــــــــت, الصُفــــــــة, الطَّائـــــــــر, الطوب, العسَّاسيــــــــــــــــن, القبة, القلوي, القورق, الكُحُـــــــــول, الكيميـــــــــاء, المنــــــاخ, النسر الواقع, الواقع, بطاقــــــــة التعريـــــــــــــــف, بيت الجــــــوزاء, تعاريـــــــــــــــف, حشَّــــــــــــــاشين, خوارزم, راحـــــــة, راحـــــة اليد, رِجـــــــل, رجل الجبَّار, رزمة, زرقـــــــــــــون, زيتــــــــــــوني, سفـــــــر, سمت الرأس, سواحــــــــــل, شــــــــاش, صـــــــــودا, صِفـــــــــــــــــــــــــــر, صکّ, عوارية, غَــــــــزّة, فم الحوت, قَــــــــــزّ, قندي, لاژورد, مسخرة, مطـــــــــــــــــــرح, موسم, مومياء, نظيـــــــــــــر

Keep learning Arabic with us!

Build vocabulary, practice pronunciation, and more with Transparent Language Online. Available anytime, anywhere, on any device.