Here is a list of body language communication and a free video watch with extra vocabulary. There are many examples of how body language is a form of communication. Body language is used in every country and culture throughout the world.

Why is body language important to understand?

- Body language is used to assess people’s characters. It is one of the first ways we assess a stranger’s character.

- Body language is used to communicate directly with someone when language is not possible.

- Body language is commonly used and assessed at work and interviews.

- Body language is an essential part of friendships and relationships.

- Body language can lead to great misunderstanding between different cultures.

The video tutorial below gives some of the most common examples of body language. More examples are listed under the video.

Body Language Vocabulary: Video Tutorial

A great video to learn some vocabulary for body language communication. A fun video to show that learning vocabulary can be fun!!!

List of Body Language

Below is a list of body language that is common in the west with the common meaning.

Facial Expressions

- Avoiding eye contact = shy, worried, lying

- Crinkling nose = disgust

- Deadpan face (without any expression) = emotionless or hiding feelings

- Direct eye contact = confidence

- Eyes staring into the distance = dreamy, not concentrating

- Pressing lips together (tight lipped) = annoyed, angry

- Raised eye brows = doubtful, disbelieving

- Smiling = friendly

Physical Actions

- Arms behind back, shoulders back = confidence

- Arms crossed = defensive or insecure but sometimes it means being angry

- Bowing (bending at the waist) = greeting someone new (in some countries)

- Biting nails = nervous

- Blushing (going red in the cheeks) or stammering (speaking with hesitations and repeated letters) = embarrassment

- Eye rubbing = tired or disbelieving

- Hands covering gaping mouth = scared

- Putting arms up with palms facing forward = submission

- Scratching one’s head = confused

- Shaking the head = negative, no

- Shrugging shoulders (moving shoulders up and down) = don’t know, doubt, confused

- Stroking one’s chin = thinking deeply

- Nodding head = agreement, yes

- Firm handshake = strong and decisive / limp handshake = weak

International Problems with Body Language

Nodding head = In some countries, it means “yes” but in other countries it means “no”. Likewise, a shaking head means “no” in some countries but “yes” in others.

Silence = In the West, this can be negative and be a problem between people. However, in other countries, such as China or Japan, it can be a sign of agreement or femininity.

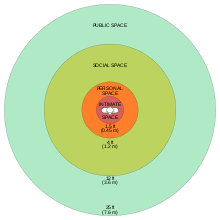

Personal space = In countries, such as England, people should stand a respectful distance from each other but in other countries, such as Spain, people touch each other when talking. In Japan, the person space is often bigger between people than in England. Respectful space between people changes depending on countries.

Eye Contact = In the West, this is a sign of confidence and is important when listening actively to someone. On the other hand, there are countries where this might be a sign of aggression and confrontation.

Practice Using Body Language Vocabulary

Fill the gaps of these sentences with the suitable words:

1. I had no idea what she was talking about. Then suddenly she asked a question that I couldn’t understand so I just ………….. my shoulders and walked away.

2. My boss always tells tall stories. Yesterday he came to work with another unbelievable story but the only response I could give was to ……….. my eyebrows.

3. If there’s one thing I hate, it’s being late. Once I was in a really long meeting at work and by the time we finished I was late to meet my friend. During the meeting, I could feel myself getting impatient and my foot started ……………. on the floor.

4. I can’t stand watching films at the cinema because you can’t relax like you can in private, particularly when watching an action movie full of surprises and shocks. When there is a really sudden unexpected scene, my eyes ………. and my mouth ……… open which I find really embarrassing in public.

5. I remember once I was late for an appointment. When I arrived, which was over 1 hour late, I …………. deep red and stammered an apology.

Answers

- shrugged (the answer isn’t “shrugged off” because that means to get rid of – usually a feeling – and does relate to shoulders)

- raise

- tapping (the answer isn’t stamping because stamping is when you are very angry not impatient)

- widen gapes (don’t forget the “s”)

- blushed

Using vocabulary in IELTS

Q) In what way is body language a form of communication?

A) Well, people use body language to send a message or to indicate something so it is definitely a way to communicate. For example, when people raise their eyebrows, it often means they are incredulous or disbelieving and when they tap their foot on the floor, you know they are impatient. So, using facial expressions and physical actions can communicate things to other people.

Q) Do you think it is possible to misunderstand someone’s body language?

A) Yes, definitely. When someone avoids your eye, it is possible to think that they are avoiding your question and don’t want to talk to you. But really, it might be that they are just shy. So, it’s quite easy to grasp the wrong meaning in people’s actions.

Q) Describe a time you were late for an appointment.

A) I remember, about one month ago, organising to meet someone in the town center at 9pm. Unfortunately, I was delayed because of traffic and didn’t arrive until about 9.30pm. My friend was really mad. She had her arms crossed and was tapping her foot impatiently on the ground. I was so embarrassed and blushed a lot. I stammered my apology but felt really uncomfortable because she was staring at me with angry eyes. Anyway, we sorted out our differences and have been really good friends ever since. (this is an example of part of a talk for speaking part 2 – add details and descriptions)

Main IELTS Pages

Develop your IELTS skills with tips, model answers, lessons, free videos and more.

- IELTS Listening

- IELTS Reading

- IELTS Writing Task 1

- IELTS Writing Task 2

- IELTS Speaking

- Vocabulary for IELTS

- IELTS Test Information (FAQ)

- Home Page: IELTS Liz

Body Language

You may think your mother tongue is English or other languages, but you are wrong. The language you are talking with the most is not the one you speak with it by using your tongue. The first language we all should learn how to talk with is body language.

Body language is the physical and non-verbal behavior with which we can transfer our means and communicate. Knowing about body language techniques helps us communicate better and more effectively. By using its methods, we can be the best in our negotiation, communication and public speaking.

The importance of learning body language

Body language is one of the non-verbal communication skills which has an essential position in our daily life from usual regular talks to professional negotiations.

We can identify others’ intentions and messages better when we know body language, and we can control what we want to say.

The words don’t matter so much.

Before you start a conversation in crowd, you see their behavior and body moves.

First thing we notice when we are in crowd is others’ body language

When you see someone for the first time at a party, you judge them for being a friend or foe by noticing their body language. Researchers believe that words transfer the message, but body language shows our feelings and personal perspectives. Sometimes they refer to it as a replacement for verbal messages. For example, can a woman look at a man and scares the hell out of him only by that look?

Professionals should know what others are doing by listening to their voice and predict what they want to say by seeing their moves and body language.

Body language is the ability to know the emotions and behavior of the ones around you.

How can body language spoil our emotions?

Body language clarifies our emotional conditions. Every gesture, every move is critical to show our feelings. For example, a fat man who is worried about his weight pulls his double chin and a woman who is concerned about her fat flank, lowers her shirt all the time. Someone who is defensive sits with folded arms or has his legs crossed or maybe even does both.

People use body language to show their emotions.

The key to read body language is to understand people’s feelings besides we listen to what they say and notice their conditions while they talk. This way we can distinguish truths from lies.

But body language is more complicated than to know the whole character of someone only by learning a few points. To read body language, we usually have to analyze several gestures and behaviors at the same time.

Is the ability of body language inherent or acquired?

Let me ask you a question first. When you sit with folded arms, do you put your right arm on the left or your left arm on the right?

Most people don’t know which one until they actually try it. Sit with folded arms right now and then change your arms’ positions. You’ll know which one is easier for you.

Evidence has shown that this gesture is genetically and can’t be changed.

It’s true that there are many different cultures, but most of the main body language signs are the same in different countries.

Albeit there is still debate that which one is acquired and has become a habit and which one is inherent.

For example, most men put their coats on starting with the right sleeve while most women do the same starting with the left sleeve.

Sometimes there is a tiny difference between men and women’s body language

Albeit this one is because men use their right hemisphere more than the left hemisphere and for women, it’s the opposite.

Some important points:

When you hear from people in different positions or see their gestures, you can’t be sure about their right perspective; you have to consider these three rules before you judge:

Principle 1: Try to notice all the moves at the same time

One of the most common mistakes in reading body language is to interpret one move aside from the others.

For example, scratching your head means sweating, uncertainty, dandruff, flea, forgetting things and lying. To know which one is correct depends on other gestures at the same time as this one.

Scratching your head as a body language sign has many different meanings.

Body language has words and phrases like all languages. Every move is like a word.

For example, “dressing” means:

– a sauce for salads

– a piece of material used to cover and protect a wound.

– Putting some clothes on

– size or stiffening used in the finishing of fabrics.

– a fertilizing substance such as compost or manure spread over or plowed into a land.

The moment you put “dressing” in a sentence with other words, you know the meaning of it.

A correct sentence must have at least three words; body language is the same.

Principle 2: look for harmony

Researches have shown that the non-verbal signs have a five-time impact over verbal talks. Imagine you see a politician talking about embracing young spirits and their ideas, but he stands with his folded arms and his head below. Once, Freud was listening to one of his clients talking about how happy she is with her marriage but she was playing with her ring, taking it off and on. At this moment Freud understood she’s lying and she is not happy with her marriage.

Principle 3: read the signs at the specific situation they happen

Sometimes body language doesn’t show the exact sign we expect to see.

For example, when you see someone with folded arms in snowy weather while he puts his leg on the other and his chin is down, it probably means he’s cold. He’s not defensive at this situation. Or he may be polite to sit with folded arms. But when the same person sits in front of you with the same gestures while you are selling something to him, it means he doesn’t agree on your offer.

The importance of body language in communication

Have you ever noticed that you see others’ body language in a party before you communicate with them?

Imagine you are at a party and you want to talk to someone. First, you see their body moves and facial expression. Is this person angry or happy?

Then you decide. If the person is happy, you start with a sentence that makes him even happier, a joke for instance.

But if he’s angry, you know you have to start talking more seriously and not making a joke.

You must know that learning body language affects your behavior too.

Imagine you are going to a meeting. When you know about body language, you know you have to be well-dressed, polite. The steps you are taking while you walk and your gestures are essential for the first impression. Now that you have learned body language, you do things so that they receive your message quickly.

The way you look at the others at the table on a meeting, your eye-contact and the way you shake their hand have a profound effect on how the session may continue.

Unmannerly secretary and salesperson

Body language is essential to attracts customers and friends as well.

It must have happened to you several times when you want to buy something, and you don’t have a good feeling about the salesperson.

The secretary may treat you very politely, but yet, you don’t feel great about her/him.

In this case, you may regret buying from them and leave the store. You rather buy from a place where its staff makes you feel great.

Communicating with the boss

Sometimes, you want to talk to one of the staff who has a higher position. They treat you awfully, the way it alters the way you think about them.

For example, sometimes the manager won’t look at us when we are talking to him, and he’s playing a game on his phone.

In this situation, not only you feel bad, but also you think he disrespects you. On the other hand, the manager thinks he is doing great because he doesn’t encourage him to be rude.

Body language is essential in business relationships. when you want to talk to your boss, for instance.

Communicating with friends

There are many times that verbal talks of our friends and relatives are the same, but after a while, we tell them: hey, why are you acting like this?

They say: like what?

And we often say: like this.

There is a joint in all this talk! Our friend or relative conveys a lousy feeling to us without changing his/her word. It shows how powerful non-verbal communication is.

What is its role in all this?

Professor Albert Mehrabian was born in an Armenian family in Iran. He’s a Psychologist in the communication field, and he pointed out to an interesting subject in one of his researches which people such as Brian Tracy always refers to.

He found out that all our communication effects include three parts:

1- words

2- the tone of voice

3- body language

another interesting thing is that the effectiveness rate of each part depends on how we communicate.

It’s a good idea to watch one of Creativity works videos about Professor Mehrabian’s theory on communication and body language.

As you know, most speakers and professionals focus on words and pay less attention to their tone and movements while this research has shown that the words have the least impression of almost 7%. It’s 38% for the sound of voice, and 55% is for body language!

How much body language and non-verbal communication affects on our relationships?

It’s fabulous indeed. It means teachers who sit behind a desk and teach, use only 7% of their teaching ability. It’s a disaster because most people- not just teachers- ignore this in their methods and communications.

Now it makes sense to justify why people prefer to watch TV than listen to the radio and prefer to listen to the radio instead of reading a book.

Till now we talked about non-verbal signs. Now we want to see how to use them to have better communication.

First, we should know which parts of our body and in which situation.

Maybe this categorizing is not common, but it can simplify things:

1- regular interpersonal communication:

Body language comes in handy in these kinds of communications (communicating with a salesperson, manager, etc.) which we have many of them in our lives. For example, if we are not willing to listen to them, our movements show it too! (of course, there are solutions to that which we explain in other articles.)

2- public speaking:

Body language has the most crucial role in public speaking.

Body language is essential in public speaking and presentations which is the primary goal of this organization) and we have to pay very close attention to it.

First, we have to be careful that our body language won’t make the audience feel terrible. Second, we have to impress the audience with our movements for example, when we show a significant amount, opening our arms will help.

3- Audience analysis

We have to see if the audience is willing to hear what we are saying. Are they telling the truth or lying? Does the person trust us or not?

We intend to explain all this in other lengthy articles.

I am an instructional designer! The one who loves to improve the quality of my life and others in a real sense. To achieve this goal, I am keen on using neuroscience to design cognitive interventions.

I am pleased that since the establishment of +1 in 2012 we have used the slogan of being more effective than one single person to make the world a much prettier place to live.

Reading Body Language Signs and Communications

Why is Body Language Relevant?

Body Language is a significant aspect of modern communications and relationships. Therefore, it is very relevant to management or leadership and to all aspects of work and business where communications can be seen and physically observed among people.

Body language is also very relevant to relationships outside of work, for example in dating and in families and parenting.

In terms of observable body language, non-verbal (non-spoken) signals are being exchanged whether these signals are accompanied by spoken words or not.

Body language works both ways:

- Your own positioning and movements reveal your feelings and meanings to others.

- Other people’s body language reveals their feelings and meanings to you.

The sending and receiving of signals happen on conscious and unconscious levels.

The study of body language is also known as kinesics (pronounced ‘kineesicks’), which is derived from the Greek word kinesis, meaning motion.

To test your knowledge see the free Body Language Quiz, which can be used to test/reinforce the learning offered in this article.

(N.B. US and UK-English spellings, e.g., ‘ize’ and ‘ise’ are used in this page to allow for different searching preferences. Please feel free to change these according to your local requirements when using these materials.)

Note. Body language is not an exact science.

Understanding How Body Language Works

Understanding body language involves the interpretation of several consistent signals to support or indicate a particular conclusion.

If you want to skip the background theory and history then go straight to the body language signals and meanings.

Body Language Basics and Introduction

Body language is a powerful concept that is well understood by successful people.

The study and theory of it have become popular in recent years because psychologists have been able to understand what we ‘say’ through our bodily gestures and facial expressions, so as to translate and reveal our underlying feelings and attitudes.

- Body Language is also referred to as ‘non-verbal communications’, and less commonly ‘non-vocal communications’.

- The term ‘non-verbal communications’ tends to be used in a wider sense, and all these terms are somewhat vague.

Definitions

As explained, the terms body language and non-verbal communications are rather vague.

So what is body language? And more usefully, what might we regard it to be, if we are to make the most of studying and using it?

- The Oxford English Dictionary (revised 2005) definition is:

- «Body language — noun — the conscious and unconscious movements and postures by which attitudes and feelings are communicated [for example]: his intent was clearly expressed in his body language.»

- The Oxford Business English Dictionary offers a slightly different definition. Appropriately and interestingly the Oxford Business English Dictionary emphasizes the sense that it can be used as a tool, rather than it being an involuntary effect with no particular purpose:

- «Body language — noun — the process of communicating what you are feeling or thinking by the way you place and move your body rather than by words [for example]: The course trains sales people in reading the customer’s body language.»

- The OED dictionary definition of kinesics — the technical term for the study of body language (and more loosely of body language itself) — depends on the interpretation of ‘non-verbal communication’:

- «Kinesics — the study of the way in which certain body movements and gestures serve as a form of non-verbal communication… [and] body movements and gestures regarded as a form of non-verbal communication.»

Body language is more than those brief descriptions.

- Body language certainly also encompasses where the body is in relation to other bodies (often referred to as ‘personal space’).

- It certainly also includes very small bodily movements such as facial expressions and eye movements.

- Body language also arguably covers all that we communicate through our bodies apart from the spoken words (thereby encompassing breathing, perspiration, pulse, blood pressure, blushing, etc.)

In this respect, standard dictionary definitions do not always describe the phrase fully and properly.

We could define it more fully as:

«Body language is the unconscious and conscious transmission and interpretation of feelings, attitudes, and moods, through:

- Body posture, movement, physical state, position and relationship to other bodies, objects and surroundings,

- Facial expression and eye movement,

(and this transmission and interpretation can be quite different to the spoken words).«

Words alone — especially emotional words (or words used in emotional situations) — rarely reflect full or true meaning and motive.

Defining what Body Language Entails

Clarification of terminology: For the purposes of this article, the terms ‘body language’ and ‘non-verbal communications’ are broadly interchangeable. This guide also takes the view that it is the study of how people communicate face-to-face aside from the spoken words themselves, and in this respect, the treatment of the subject here is broader than typical guides, which are limited merely to body positions and gestures.

Defining what behaviours or actions constitute «Body Language» is not as simple as it may seem:

- Does body language include facial expression and eye movement? — Usually, yes.

- What about breathing and perspiration? — This depends on the definition used.

- And while tone and pitch of voice are part of verbal signals, are these part of body language too? — Not normally, but arguably so, especially as you could ignore them if considering only the spoken words and physical gestures/expressions.

There are no absolute right/wrong answers to these questions. It’s a matter of interpretation.

A good reason for broadening our scope is to avoid missing important signals which might not be considered within a narrower definition.

Nevertheless, confusion easily arises if definitions and context are not properly established, for example:

- It is commonly and carelessly quoted that ‘non-verbal communications’ and/or ‘body language’ account for up to 93% of the meaning that people take from any human communication. This statistic is actually a distortion based on Albert Mehrabian’s research theory, which while itself is something of a cornerstone of body language research, certainly did not make such a sweeping claim.

- Mehrabian’s research findings in fact focused on communications with a strong emotional or ‘feelings’ element. Moreover, the 93% non-verbal proportion included vocal intonation (paralinguistics), which are regarded by many as falling outside of the definition of «body language».

Care must, therefore, be exercised when stating specific figures relating to percentages of meaning conveyed, or in making any firm claims in relation to body language and non-verbal communications.

Body Language Tends to Include:

- How we position our bodies

- Our closeness to and the space between us and other people (proxemics), and how this changes

- Our facial expressions

- Our eyes especially and how our eyes move and focus

- How we touch ourselves and others

- How our bodies connect with other non-bodily things, for instance, pens, cigarettes, spectacles and clothing

- Our breathing, and other less noticeable physical effects, for example, our heartbeat and perspiration

Note. Depending on the definition you choose to apply these may vary

Body Language Tends Not to Include:

- the pace, pitch, and intonation, volume, variation, pauses, etc., of our voice.

Arguably this last point should be encompassed by body language because a lot happens here which can easily be missed if we consider merely the spoken word and the traditional narrow definition.

- Voice type and other audible signals are typically not included because they are audible ‘verbal’ signals rather than physical visual ones, nevertheless, the way the voice is used is a very significant (usually unconscious) aspect of communication, aside from the bare words themselves. Consequently, voice type is always important to consider alongside the usual factors.

- Similarly, breathing and heartbeat, etc., are typically excluded from many general descriptions but are certainly part of the range of non-verbal bodily actions and signals which contribute to body language in its fullest sense.

The Importance of Body Language

It is safe to say that body language represents a very significant proportion of meaning that is conveyed and interpreted between people.

- Many body language experts and sources seem to agree that between 50-80% of all human communications are non-verbal. So while the statistics vary according to the situation, it is generally accepted that non-verbal communications are very important in how we understand each other (or fail to), especially in face-to-face and one-to-one communications, and most definitely when the communications involve an emotional or attitudinal element.

Understanding and Awareness

-

Importantly, understanding body language enables better self-awareness and self-control too.

-

When we understand non-verbal communication we become better able to refine and improve what our body says about us, which generates a positive improvement in the way we feel, the way we perform, and what we achieve.

-

Body language enables us to understand more about our own and other people’s feelings and meanings

-

Our reactions to other people’s eyes — movement, focus, expression, etc — and their reactions to our eyes — contribute greatly to mutual assessment and understanding, consciously and unconsciously.

-

With no words at all, feelings can be conveyed in a single glance. The metaphor which describes the eyes of two lovers meeting across a crowded room is not only found in old romantic movies. It’s based on scientific fact — the strong powers of non-verbal communications.

Life Advantage

- Our interpretation of body language, notably eyes and facial expressions, is instinctive, and with a little thought and knowledge, we can significantly increase our conscious awareness of these signals: both the signals we transmit, and the signals in others that we observe.

- Doing so gives us a significant advantage in life — professionally and personally — in our dealings with others.

First Impressions

Body language is especially crucial when we meet someone for the first time.

- We form our opinions of someone we meet for the first time in just a few seconds, and this initial instinctual assessment is based far more on what we see and feel about the other person than on the words they speak.

- On many occasions, we form a strong view about a new person before they speak a single word.

Consequently, body language is very influential in forming impressions on first meeting someone.

The effect happens both ways — to and from:

- When we meet someone for the first time, their body language, on conscious and unconscious levels, largely determines our initial impression of them.

- In turn, when someone meets us for the first time, they form their initial impression of us largely from our non-verbal signals.

The Two-Way Effect of Body Language

This two-way effect continues throughout communications and relationships between people.

Body language is constantly being exchanged and interpreted between people, even though much of the time this is happening on an unconscious level.

- Remember — while you are interpreting (consciously or unconsciously) the body language of other people, so other people are constantly interpreting yours.

The people with the most conscious awareness of, and capabilities to read, body language tend to have an advantage over those whose appreciation is limited largely to the unconscious.

You will shift your own awareness from the unconscious into the conscious by learning about the subject, and then by practising your reading of non-verbal communications in your dealings with others.

Background and History of Body Language

Philosophers and scientists have connected human physical behaviour with meaning, mood and personality for thousands of years, but only in living memory has the study of body language become as sophisticated and detailed as it is today.

Studies and written works on the subject are very sparse until the mid-1900s.

Early History

The first known experts to consider aspects of body language were probably the ancient Greeks, notably Hippocrates and Aristotle, through their interest in human personality and behaviour, and the Romans, notably Cicero, relating gestures to feelings and communications. Much of this early interest was in refining ideas about oration — speech-making — given its significance to leadership and government.

Isolated studies appeared in more recent times, for example, Francis Bacon in Advancement of Learning, 1605, explored gestures as reflection or extension of spoken communications. John Bulwer’s Natural History of the Hand published in 1644, considered hand gestures. Gilbert Austin’s Chironomia in 1806 looked at using gestures to improve speech-making.

Charles Darwin Study of Body Language

Charles Darwin in the late 1800s could be regarded as the earliest expert to have made a serious scientific observation about body language, but there seems little substantial development of ideas for at least the next 150 years.

Darwin’s work pioneered much ethological thinking. Ethology began as the science of animal behaviour. It became properly established during the early 1900s and increasingly extends to human behaviour and social organization. Where ethology considers animal evolution and communications, it relates strongly to human body language. Ethologists have progressively applied their findings to human behaviour, including body language, reflecting the evolutionary origins of much human non-verbal communication — and society’s growing acceptance of evolutionary rather than creationist theory.

Austrian zoologist and 1973 Nobel Prizewinner Konrad Lorenz (1903-89) was a founding figure in ethology. Desmond Morris, the author of The Naked Ape, discussed below, is an ethologist, as is the evolutionary biologist Richard Dawkins (b. 1941) a leading modern thinker in the field. Ethology, like psychology, is an over-arching science that continues to clarify the understanding of body language.

Later Research on Body Language

The popular and accessible study of non-verbal communication as we know it today is very recent.

In his popular 1971 book ‘Body Language’, Julius Fast (1919-2008) wrote: «…kinesics [body language and its study] is still so new as a science that its authorities can be counted on the fingers of one hand…»

Julius Fast was an American award-winning writer of fiction and non-fiction work dealing especially with human physiology and behaviour. His book Body Language was among the first to bring the subject to a mainstream audience.

Significantly the references in Julius Fast’s book (Birdwhistell, Goffman, Hall, Mehrabian, Scheflen, etc — see body language references and books below) indicate the freshness of the subject in 1971. All except one of Julius Fast’s cited works are from the 1950s and 1960s.

The exception among Fast’s contemporary influences was Charles Darwin, and specifically his book The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals, written in 1872, which is commonly regarded as the beginnings of the body language science, albeit not recognised as such then.

Sigmund Freud and others in the field of psychoanalysis — in the late 1800s and early 1900s — would have had a good awareness of many aspects of the concept, including personal space, but they did not focus on non-verbal communications concepts or develop theories in their own right. Freud and similar psychoanalysts and psychologists of that time were focused on behaviour and therapeutic analysis rather than the study of non-verbal communications per se.

A different view of human behaviour related to and overlapping body language, surfaced strongly in Desmond Morris’s 1967 book The Naked Ape, and in follow-up books such as Intimate Behaviour, 1971. Morris, a British zoologist and ethologist, linked human behaviour — much of it concerned with communications — to human ‘animalistic’ evolution. His work remains a popular and controversial perspective for understanding people’s behaviours, and while his theories did not focus strongly on body language, Morris’s popularity in the late 1960s and 1970s contributed significantly to the increasing interest among people beyond the scientific community — for a better understanding of how and why we feel and act and communicate.

Body Language Terminology — Physiognomy, Kinesics, Proxemics and Kinaesthetics

An important aspect of body language is facial expression, for which quite early ‘scientific’ thinking can be traced:

- Physiognomy is an obscure and related concept to body language. Physiognomy refers to facial features and expressions which were/are said to indicate the person’s character or nature, or ethnic origin. The word physiognomy is derived from medieval Latin, and earlier Greek (phusiognominia), which originally meant (the art or capability of) judging a person’s nature from his/her facial features and expressions. The ancient roots of this concept demonstrate that while body language itself is a recently defined system of analysis, the notion of inferring human nature or character from facial expression is extremely old.

- Kinesics (pronounced ‘kineesicks’ with stress on the ‘ee’) is the modern technical word for body language, and more scientifically the study of body language. The word kinesics was first used in English in this sense in the 1950s, deriving from the Greek word kinesis, meaning motion, and seems to have first been used by Dr Ray Birdwhistell, an American 1950s researcher and writer on body language. (See references ).

The introduction of a new technical word — (in this case, kinesics) — generally comes after the establishment of the subject it describes, which supports the assertion that the modern concept of body language — encompassing facial expressions and personal space — did not exist until the 1950s.

- Proxemics is the technical term for the personal space aspect of body language. The word was devised in the late 1950s or early 1960s by Edward Twitchell Hall, an American anthropologist. The word is Hall’s adaptation of the word proximity, meaning closeness or nearness. (See personal space)

- From the word kinesics, Ray Birdwhistell coined the term kine to refer to a single body language signal. This is not to be confused with the ancient and same word kine, meaning a group of cows. Neither word seems to have caught on in a big way, which in one way is a pity, but in another way probably makes matters simpler for anyone interested in the body language of cows.

The Greek word kinesis is also a root word of kinaesthetics, which is the ‘K’ in the VAK (‘see hear feel’) learning styles model.

- Kinaesthetics (also known as kinesthetics), the study of learning styles, is related to some of the principles of body language, in terms of conveying meaning and information via physical movement and experience.

Body language is among many branches of science and education which seek to interpret and exploit messages and meaning from the ‘touchy-feely’ side of life.

For example, the concepts of experiential learning, games and exercises, and love and spirituality at work — are all different perspectives and attempts to unlock and develop people’s potential using ideas centred around kinaesthetics, as distinct from the more tangible and easily measurable areas of facts, figures words and logic.

These and similar methodologies do not necessarily reference body language directly, but there are very strong inter-connections.

Bloom’s Taxonomy and Kolb’s Learning Styles are also helpful perspectives in appreciating the significance of kinaesthetics, and therefore body language, in life and work today.

The communications concepts of NLP (Neuro-linguistic Programming) and Transactional Analysis are closely dependent on understanding body language, NLP especially.

Body Language — Nature or Nurture?

Body language is part of human evolution, but as with many other aspects of human behaviour, the precise mixture of genetic (inherited) and environmental (learned or conditioned) influences is not known and opinions vary.

Julius Fast noted this, especially regarding facial expressions. To emphasise the shifting debate he cited for example:

- Darwin’s belief that human facial expressions were similar among humans of all cultures, due to evolutionary theory.

- Bruner and Taguiri’s (see references) opposing views — in the early 1950s, after thirty years of research, they largely rejected the notion that facial expressions were inborn.

- and Ekman, Friesan and Sorensen’s findings (see references) — in 1969, having discovered consistent emotional-facial recognition across widely diverse cultural groups, which supported Darwin’s evolutionary-centred ideas.

The discussion has continued in a similar vein to the modern-day — studies ‘proving’ genetic or environmental cause — ‘nature’ or ‘nurture’ — for one aspect of body language or another.

The situation is made more complex when one considers the genetic (inherited) capability or inclination to learn body language. Is this nature or nurture?

Body language is part ‘nature’ and part ‘nurture’. It is is partly genetic (inborn — ‘nature’), and partly environmental (conditioned/learned — ‘nurture’).

- The use and recognition of certain fundamental facial expressions are now generally accepted to be consistent and genetically determined among all humans regardless of culture.

- However the use and recognition of less fundamental physical gestures (hand movements for example, or the winking of an eye), and aspects of personal space distances, are now generally accepted to be environmentally determined (learned, rather than inherited), which is significantly dependent on local social groups and cultures.

- Certain vocal intonation speech variations (if body language is extended to cover everything but the spoken words) also fall within this environmentally determined category. (See the ‘other audible signals’ section.)

In summary, we can be certain that body language (namely the conscious and unconscious sending and receiving of non-verbal signals) is partly inborn, and partly learned or conditioned.

Body Language and Evolution

The evolutionary perspectives of body language are fascinating, in terms of its purpose and how it is exploited, which in turn feeds back into the purpose of body language at conscious and unconscious levels.

Why did Body Language Evolve?

For various reasons people intentionally and frequently mask their true feelings. (Transactional Analysis theory is very useful in understanding more about this)

In expectation of these ‘masking’ tendencies in others, humans try to imagine what another person has in their mind. The need to understand what lies behind the mask obviously increases according to the importance of the relationship.

- Body language helps us to manage and guard against these tendencies, and also — significantly especially in flirting/dating/mating rituals — it often helps people to communicate and resolve relationship issues when conscious behaviour and speech fails to do so.

Body language has evolved in spite of human awareness and conscious intelligence: rather like a guardian angel, it can help take care of us, connecting us to kindred souls, and protecting us from threats.

While the importance of body language in communications and management has become a popular interest and science in the last few decades, human beings have relied on kinesics instinctively in many ways for many thousands of years.

The Evolution of Body Language

- Early natural exponents of interpreting body language were explorers and tribal leaders, who had to be able to read potential foes — to know whether to trust or defend or attack.

- Earlier than this, our cavemen ancestors certainly needed to read body language, if only because no other language existed.

Humans have also learned to read the body language of animals (and vice-versa), although humans almost certainly had greater skills in this area a long time ago. Shepherds, horse-riders and animal trainers throughout time and still today have good capabilities in reading animal body language, which for many extends to the human variety. Monty Robert, the real-life ‘Horse Whisperer’ is a good example.

Body language, and the reading of non-verbal communications and feelings, are in our genes.

Gender differences: Interestingly, women tend to have better perception and interpretation of body language than men. This is perhaps a feature of evolutionary survival since females needed these skills to reduce their physical vulnerability to males and the consequential threat to life, limb, and offspring. Females might not be so physically vulnerable in modern times, but their kinesic capabilities generally continue typically to be stronger than the male of the species. Thus, women tend to be able to employ body language (for sending and interpreting signals) more effectively than men.

Katherine Benziger’s theories of brain types and thinking styles provide a useful additional perspective. Women tend to have more empathic sensitivity than men, which naturally aids their awareness and capabilities. Aside from gender differences, men and women with strong empathic sensitivity (typically right-basal or rear brain bias) tend to be better at picking up signals.

The Six Universal Facial Expressions

It is now generally accepted that certain basic facial expressions of human emotion are recognized around the world — and that the use and recognition of these expressions are genetically inherited rather than socially conditioned or learned.

While there have been found to be minor variations and differences among obscurely isolated tribes-people, the following basic human emotions are generally used, recognized, and part of humankind’s genetic character:

These emotional facial expressions are:

- Happiness

- Sadness

- Fear

- Disgust

- Surprise

- Anger

Charles Darwin was first to make these claims in his book The Expressions of the Emotions in Man and Animals, published in 1872. This book incidentally initially far outsold The Origin of Species, such as its wide (and controversial) appeal at the time.

Darwin’s assertions about genetically inherited facial expressions remained the subject of much debate for many years.

Paul Ekman

In the 1960s a Californian psychiatrist and expert in facial expressions, Paul Ekman, (with Sorenson and Friesen — see references) conducted and published extensive studies with people of various cultures to explore the validity of Darwin’s theory — that certain facial expressions and man’s ability to recognize them are inborn and universal among people. Ekman’s work notably included isolated tribes-people who could not have been influenced by Western media and images, and essentially proved that Darwin was right — i.e., that the use and recognition of facial expressions to convey certain basic human emotions is part of human evolved nature, genetically inherited, and not dependent on social learning or conditioning.

Body language is instinctively interpreted by us all to a limited degree, but the subject is potentially immensely complex. Perhaps infinitely so, given that the human body is said to be capable of producing 700,000 different movements (Hartland and Tosh, 2001 — see references).

As with other behavioural sciences, the study of body language benefited from the development of brain-imaging technology in the last part of the 20th century. This dramatically accelerated the research and understanding into connections between the brain, feelings, thoughts and body movement. We should expect to see this effect continuing and providing a more solid evidence base for body language theory, much of which remains empirical, i.e., based on experience and observation, rather than a scientific test.

Given the potential for confusion, the discussion below highlights some of these analytical considerations.

Context

Body language also depends on context: in a certain situation, it might not mean the same as in another.

Some ‘body language’ is not what it seems at all, for example:

- Someone rubbing their eye might have an irritation, rather than being tired — or disbelieving, or upset.

- Someone with crossed arms might be keeping warm, rather than being defensive.

- Someone scratching their nose might actually have an itch, rather than concealing a lie.

Sufficient Samples/Evidence

A single body language signal isn’t as reliable as several signals:

- As with any system of evidence, ‘clusters’ of body language signals provide a much more reliable indication of meaning than one or two signals in isolation.

- Avoid interpreting only single signals. Look for combinations of signals which support an overall conclusion, especially for signals which can mean two or more quite different things.

Culture/Ethnicity

Certain body language is the same in all people, for example, smiling and frowning (and see the six universally recognizable facial expressions above), but some body language is specific to a culture or ethnic group.

For more information see examples of cultural body language differences below.

Awareness of possible cultural differences is especially important in today’s increasingly mixed societies.

- Personal space preferences (distances inside which a person is uncomfortable when someone encroaches) can vary between people of different ethnicity.

In general, this article offers interpretations applicable to Western culture.

If you can suggest any different ethnic interpretations of body language please send them and we’ll broaden the guide accordingly.

Age and Gender

Many body language signals are relative. A gesture by one person in a certain situation can carry far more, or very little meaning, compared to the same gesture used by a different person in a different situation.

- Young men for example often display a lot of pronounced gestures because they are naturally energetic, uninhibited and supple. Older women, relatively, are less energetic, adopt more modest postures, and are prevented by clothing and upbringing from exhibiting very pronounced gestures.

So when assessing body language — especially the strength of signals and meanings — it’s important to do so in relative terms, considering the type of person and situation involved.

Faking/Deception

Some people artificially control their outward body language to give the impression they seek to create at the time.

- A confident firm handshake, or direct eye contact, are examples of signals which can quite easily be ‘faked’ — usually temporarily, but sometimes more consistently.

However while a degree of faking is possible, it is not possible for someone to control or suppress all outgoing signals.

This is an additional reason to avoid superficial analysis based on isolated signals, and to seek as many indicators as possible, especially subtle clues when suspecting things might not be what they seem. Politicians and manipulative salespeople come to mind for some reason.

- Looking for ‘micro gestures’ (pupils contract, an eyebrow lifts, corner of the twitch) can help identify the true meaning and motive behind one or two strong and potentially false signals.

These micro gestures are very small, difficult to spot and are subconscious, but we cannot control them, hence their usefulness.

Boredom, Nervousness and Insecurity Signals

Many body language signals indicate negative feelings such as boredom, disinterest, anxiousness or insecurity.

The temptation upon seeing such signals is to imagine a weakness on the part of the person exhibiting them.

This can be so, however the proper interpretation of body language should look beyond the person and the signal — and consider the situation, especially if you are using body language within personal development or management. Ask yourself:

- What is causing the negative feelings giving rise to the negative signals?

It is often the situation, not the person — for example, here are examples of circumstances that can produce negative feelings and signals in people, often even if they are strong and confident:

- Dominance of a boss or a teacher or other person perceived to be in authority

- Overloading a person with new knowledge or learning

- Tiredness

- Stress caused by anything

- Cold weather or cold conditions

- Lack of food and drink

- Illness or disability

- Alcohol or drugs

- Being in a minority or feeling excluded

- Unfamiliarity — newness — change

Ask yourself, when analysing body language:

- Are there external factors affecting the mood and condition of the individual concerned?

Do not jump to conclusions — especially negative ones — using body language analysis alone.

Quick Reference Guide: Translation of Gestures, Signs and Other Factors

When translating body language signals into feelings and meanings remember that one signal does not reliably indicate a meaning.

- Clusters of signals more reliably indicate meaning.

Note. This is a general guide. This should not be used alone for making serious decisions about people. Body language is one of several indicators of mood, meaning and motive. This is a guide, not an absolutely reliable indicator, and this applies especially until you’ve developed good capabilities of reading signs.

Even ‘obvious’ signs can be missed — especially if displayed as subtle movements in a group of people and if your mind is on other things — so I make no apology for including ‘obvious’ body language in this guide.

It is important to remember that cultural differences influence these signals and their interpretation. This guide is based on ‘Western World’ and North European behaviours. What may be ‘obvious’ in one culture can mean something different in another culture.

Body Language Signal Translation

The body language signals below are grouped together according to parts of the body.

Left and right are for the person giving the signals and making the movements.

This is a summary of the main body language signals. More signals and meanings will be added.

Suggest any other signals that you wish to know, and we’ll add them.

These are the body language signals that will be discussed below:

- Eyes

- Mouth

- Head

- Arms

- Hands

- Handshakes

- Legs and feet

- Personal space

Eyes

Our eyes are a very significant aspect of the non-verbal signals we send to others. To a lesser or greater extent we all ‘read’ people’s eyes without knowing how or why, and this ability seems to be inborn.

Eyes — and especially our highly developed awareness of what we see in other people’s eyes — are incredible:

- For example, we know if we have eye contact with someone at an almost unbelievable distance. Far too far away to be able to see the detail of a person’s eyes — 30-40 metres away or more sometimes — we know when there is eye contact.

- Also, we can see whether another person’s eyes are focused on us or not, and we can detect easily the differences between a ‘glazed over’ blank stare, a piercing look, a moistening eye long before tears come, and an awkward or secret glance.

We probably cannot describe these and many other eye signals, but we recognise them when we see them and we know what they mean.

When we additionally consider the eyelids, the flexibility of the eyes to widen and close, and for the pupils to enlarge or contract, it becomes easier to understand how the eyes have developed such potency in human communications.

What does it mean when eyes look left and right?

- Eyes tend to look right when the brain is imagining or creating, and left when the brain is recalling or remembering. This relates to right and left sides of the brain — in this context broadly the parts of the brain handling creativity/feelings (right) and facts/memory (left).

- This is analysed in greater detail below, chiefly based on NLP theory developed in the 1960s. Under certain circumstances ‘creating’ can mean fabrication or lying, especially (but not always — beware), when the person is supposed to be recalling facts. Looking right when stating facts does not necessarily mean lying — it could, for example, mean that the person does not know the answer, and is talking hypothetically or speculating or guessing.

| Non-Verbal Eye Signals | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Signal | Part of body | Possible meaning(s) |

Detailed explanation |

| Left and right are for the person giving the signals and making the movements. | |||

| looking right (generally) | eyes | creating, fabricating, guessing, lying, storytelling | Creating here is basically making things up and saying them. Depending on the context this can indicate lying, but in other circumstances, for example, storytelling to a child, this would be perfectly normal. Looking right and down indicates accessing feelings, which again can be a perfectly genuine response or not, depending on the context, and to an extent the person. |

| looking left (generally) | eyes | recalling, remembering, retrieving ‘facts’ | Recalling and then stating ‘facts’ from memory in appropriate context often equates to telling the truth. Whether the ‘facts’ (memories) are correct is another matter. Left downward-looking indicates silent self-conversation or self-talk, typically in trying to arrive at a view or decision. |

| looking right and up | eyes | visual imagining, fabrication, lying | Related to imagination and creative (right-side) parts of the brain, this upwards right eye movement can be a warning sign of fabrication if a person is supposed to be recalling and stating facts. |

| looking right sideways | eyes | imagining sounds | Sideways eye movements are believed to indicate imagining (right) or recalling (left) sounds, which can include for example a person imagining or fabricating what another person has said or could say. |

| looking right and down | eyes | accessing feelings | This is a creative signal but not a fabrication — it can signal that the person is self-questioning their feelings about something. Context particularly- and other signals — are important for interpreting more specific meanings about this signal. |

| looking left and up | eyes | recalling images truthfulness | Related to accessing memory in the brain, rather than creating or imagining. A reassuring sign is signalled when the person is recalling and stating facts. |

| looking left sideways | eyes | recalling or remembering sounds | Looking sideways suggests sounds; looking left suggests recalling or remembering — not fabricating or imagining. This, therefore, could indicate recalling what has been said by another person. |

| looking left down | eyes | self-talking, rationalizing | Thinking things through by self-talk — concerning an outward view, rather than the inward feelings view indicated by downward right looking. |

| direct eye contact (when speaking) | eyes | honesty — or faked honesty | Direct eye contact is generally regarded as a sign of truthfulness, however, practised liars know this and will fake the signal. |

| direct eye contact (when listening) | eyes | attentiveness, interest, attraction | Eyes that stay focused on the speaker’s eyes, tend to indicate focused interested attention too, which is normally a sign of attraction to the person and/or the subject. |

| widening eyes | eyes | interest, appeal, invitation | Widening the eyes generally signals interest in something or someone, and often invites a positive response. Widened eyes with raised eyebrows can otherwise be due to shock, but aside from this, widening eyes represents an opening and welcoming expression. In women especially widened eyes tend to increase attractiveness, which is believed by some body language experts to relate to the eye/face proportions of babies, and the associated signals of attraction and prompting urges to protect and offer love and care. |

| rubbing eye or eyes | eyes | disbelief, upset, or tiredness | Rubbing eyes or one eye can indicate disbelief as if checking the vision, or upset, in which the action relates to crying, or tiredness, which can be due to boredom, not necessarily a need for sleep. If the signal is accompanied by a long pronounced blink, this tends to support the tiredness interpretation. |

| eye shrug | eyes | frustration | An upward roll of the eyes signals frustration or exasperation as if looking to the heavens for help. |

| pupils dilated (enlarged) | eyes | attraction, desire | The pupil is the black centre of the eye which opens or closes to let in more or less light. Darkness causes pupils to dilate. So too, for some reason does seeing something appealing or attractive. The cause of the attraction depends on the situation. In the case of sexual attraction, the effect can be mutual — dilated pupils tend to be more appealing sexually than contracted ones, perhaps because of an instinctive association with darkness, night-time or bedtime, although the origins of this effect are unproven. Resist the temptation to imagine that everyone you see with dilated pupils is sexually attracted to you. |

| blinking frequently | eyes | excitement, pressure | The normal human blink rate is considered to be between six and twenty times a minute, depending on the expert. Significantly more than this is a sign of excitement or pressure. Blink rate can increase to up to a hundred times a minute. Blink rate is not a reliable sign of lying. |

| blinking infrequently | eyes | various | Infrequent blink rate can mean different things and so offers no single clue unless combined with other signals. An infrequent blink rate is probably due to boredom if the eyes are not focused, or can be the opposite — concentration — if accompanied with a strongly focused gaze. Infrequent blink rate can also be accompanied by signals of hostility or negativity and is therefore not the most revealing of body language signals. |

| eyebrow raising (eyebrow ‘flash’) | eyes | greeting, recognition, acknowledgement | Quickly raising and lowering the eyebrows is called an ‘eyebrow flash’. It is a common signal of greeting and acknowledgement and is perhaps genetically influenced since it is prevalent in monkeys (body language study does not sit entirely happily alongside creationism). Fear and surprise are also signalled by the eyebrow flash, in which case the eyebrows normally remain raised for longer until the initial shock subsides. |

| winking | eyes | friendly acknowledgement, complicity (e.g., sharing a secret or joke) | Much fuss was made in May 2007 when George W Bush winked at the Queen. The fuss was made because a wink is quite an intimate signal, directed exclusively from one person to another, and is associated with male flirting. It is strange that a non-contact wink can carry more personal implications than a physical handshake and in many situations more than a kiss on the cheek. A wink is given additional spice if accompanied by a click of the tongue. Additionally — and this was partly the sense in which Bush used it — a wink can signal a shared joke or secret. |

eyes | mouth | head | arms | hands | handshakes | legs and feet | personal space

Mouth

The mouth is associated with very many body language signals, which is not surprising given its functions — obviously speech, but also those connected with infant feeding, which connects psychologically through later life with feelings of security, love and sex.

- The mouth can be touched or obscured by a person’s own hands or fingers, and is a tremendously flexible and expressive part of the body too, performing a central role in facial expressions.

- The mouth also has more visible moving parts than other sensory organs, so there’s a lot more potential for a variety of signalling.

- Smiling is a big part of facial language. As a general rule real smiles are symmetrical and produce creases around the eyes and mouth, whereas fake smiles, for whatever reason, tend to be mouth-only gestures.

Unlike the nose and ears, which are generally only brought into action by the hands or fingers, the mouth acts quite independently, another reason for it deserving separate detailed consideration.

| Non-Verbal Mouth Gestures | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Signal | Part of body | Possible meaning(s) |

Detailed explanation |

| pasted smile | mouth | faked smile | A pasted smile is one that appears quickly, is fixed for longer than a natural smile, and seems not to extend to the eyes. This typically indicates suppressed displeasure or forced agreement of some sort. |

| tight-lipped smile | mouth | secrecy or withheld feelings | Stretched across the face in a straight line, teeth concealed. The smiler has a secret they are not going to share, possibly due to dislike or distrust. Can also be a rejection signal. |

| twisted smile | mouth | mixed feelings or sarcasm | Shows opposite emotions on each side of the face. |

| dropped-jaw smile | mouth | faked smile | More of a practised fake smile than an instinctive one. The jaw is dropped lower than in a natural smile, the act of which creates a smile. |

| smile — head tilted, looking up | mouth | playfulness, teasing, coy | Head tilted sideways and downwards so as to part hide the face, from which the smile is directed via the eyes at the intended target. |

| bottom lip jutting out | mouth | upset | Like rubbing the eyes can be an adult version of crying, so jutting or pushing the bottom lip forward is a part of the crying face and impulse. Bear in mind that people cry for reasons of genuine upset, or to avert attack and seek sympathy or kind treatment. |

| laughter | mouth | relaxation | Laughter deserves a section in its own right because it is such an interesting area. In terms of body language, genuine laughter is a sign of relaxation and feeling at ease. Natural laughter can extend to all the upper body or the whole body. The physiology of laughter is significant. Endorphins are released. Pain and stress reduces. Also, vulnerabilities show and can become more visible because people’s guard drops when laughing. |

| forced laughter | mouth | nervousness, cooperation | Unnatural laughter is often a signal of nervousness or stress, as an effort to dispel tension or change the atmosphere. Artificial laughter is a signal of cooperation and a wish to maintain empathy. |

| biting lip | mouth | tension | One of many signals suggesting tension or stress, which can be due to high concentration, but more likely to be anxiousness. |

| teeth grinding | mouth | tension, suppression | Inwardly-directed ‘displacement’ (see body language glossary) sign, due to suppression of natural reaction due to fear or other suppressants. |

| chewing gum | mouth | tension, suppression | As above — an inwardly-directed ‘displacement’ sign, due to suppression of natural reaction. Otherwise however can simply be to freshen breath or as a smoking replacement. |

| smoking | mouth | self-comforting | Smoking obviously becomes habitual and addictive, but aside from this people put things into their mouths because it’s comforting like thumb-sucking is to a child, in turn, rooted in baby experiences of feeding and especially breastfeeding. |

| thumb-sucking | mouth | self-comforting | A self-comforting impulse in babies and children, substituting breast-feeding, which can persist as a habit into adulthood. |

| chewing pen or pencil | mouth | self-comforting | Like smoking and infant thumbsucking. The pen is the teat. (Remember that next time you chew the end of your pen) |

| pursing lips | mouth | thoughtfulness, or upset | As if holding the words in the mouth until they are ready to be released. Can also indicate anxiousness or impatience at not being able to speak. Or quite differently can indicate upset, as if suppressing crying. |

| tongue poke | mouth/tongue | disapproval, rejection | The tongue extends briefly and slightly at the centre of the mouth as if tasting something nasty. The gesture may be extremely subtle. An extreme version may be accompanied by a wrinkling of the nose and a squint of the eyes. |

| hand clamped over mouth | mouth / hands | suppression, holding back, shock | Often an unconscious gesture of self-regulation — stopping speech for reasons of shock, embarrassment or for more tactical reasons. The gesture is reminiscent of the ‘speak no evil’ wise monkey. The action can be observed very clearly in young children when they witness something ‘unspeakably’ naughty or shocking. Extreme versions of the same effect would involve both hands. |

| nail biting | mouth / hands | frustration, suppression | Nail-biting is inwardly-redirected aggression borne of fear, or some other suppression of behaviour. Later nail-biting becomes reinforced as a comforting habit, again typically prompted by frustration or fear. Stress in this context is an outcome. Stress doesn’t cause nail-biting; nail-biting is the outward demonstration of stress. The cause of the stress can be various things (stressors). See the stress article for more detail about stress. |

eyes | mouth | head | arms | hands | handshakes | legs and feet | personal space

Head

The head is very significant in body language. The head tends to lead and determine general body direction but it is also vital and vulnerable being where our brain is, so the head is used a lot in directional (likes and dislikes) body language as well as in defensive (self-protection) body language.

- A person’s head, due to a very flexible neck structure, can turn, jut forward, withdraw, tilt sideways, forwards, backwards. All of these movements have meanings, which given some thought about other signals can be understood.

- The head usually has hair, ears, eyes, nose and a face, which has more complex and visible muscular effects than any other area of the body.

The head — when our hands interact with it — is therefore dynamic and busy in communicating all sorts of messages — consciously and unconsciously.

| Non-Verbal Head Gestures | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Signal | Part of body | Possible meaning(s) |

Detailed explanation |

| head nodding | head | agreement | Head nodding can occur when invited for a response, or voluntarily while listening. Nodding is confusingly sometimes also referred to as ‘head shaking up and down’. Head nodding when talking face-to-face one-to-one is easy to see, but do you always detect tiny head nods when addressing or observing a group? |

| slow head nodding | head | attentive listening | This can be a faked signal. As with all body language signals, you must look for clusters of signals rather than relying on one alone. Look at the focus of eyes to check the validity of slow head nodding. |

| fast head nodding | head | hurry up, impatience | Vigorous head nodding signifies that the listener feels the speaker has made their point or taken sufficient time. Fast head nodding is rather like the ‘wind-up’ hand gesture given off-camera or off-stage by a producer to a performer, indicating ‘time’s up — get off’. |

| head held up | head | neutrality, alertness | High head position signifies attentive listening, usually with an open or undecided mind, or lack of bias. |

| head held high | head | superiority, fearlessness, arrogance | Especially if exhibited with a jutting chin. |

| head tilted to one side | head | non-threatening, submissive, thoughtfulness | A signal of interest, and/or vulnerability, which in turn suggests a level of trust. Head tilting is thought by some to relate to ‘sizing up’ something since tilting the head changes the perspective offered by the eyes and a different view is seen of the other person or subject. Exposing the neck is also a sign of trust. |

| head forward, upright | head/body | interest, positive reaction | Head forward in the direction of a person or other subject indicates interest. The rule also applies to a forward-leaning upper body, commonly sitting, but also standing, where the movement can be a distinct and significant advancement into a closer personal space zone of the other person. Head forward and upright is different to head tilted downward. |

| head tilted downward | head | criticism, admonishment | Head tilted downwards towards a person is commonly a signal of criticism or reprimand or disapproval, usually from a position of authority. |

| head shaking | head | disagreement | Sideways shaking of the head generally indicates disagreement but can also signal feelings of disbelief, frustration or exasperation. Obvious of course, but often ignored or missed where the movement is small, especially in groups seemingly reacting in silent acceptance. |

| pronounced head shaking | head | strong disagreement | The strength of the movement of the head usually relates to the strength of feeling, and often to the force by which the head-shaker seeks to send this message to the receiver. This is an immensely powerful signal and is used intentionally by some people to dominate others. |

| head down (in response to a speaker or proposition) | head | negative, disinterested | Head down is generally a signal of rejection (e.g. of someone’s ideas), unless the head is down for a purpose like reading supporting notes. Head down when responding to criticism is a signal of failure, vulnerability (hence seeking protection) or feeling ashamed. |

| head down (while performing an activity) | head | defeat, tiredness | Lowering the head is a sign of loss, defeat, shame, etc. Hence the expressions such as ‘don’t let your head drop’, and ‘don’t let your head go down’, especially in sports and competitive activities. Head down also tends to cause shoulders and upper back to slump, increasing the signs of weakness at that moment. |

| chin up | head | pride, defiance, confidence | Very similar to the ‘head held high’ signal. Holding the chin up naturally alters the angle of the head backwards, exposing the neck, which is a signal of strength, resilience, pride or resistance. A pronounced raised chin does other interesting things to the body too — it tends to lift the sternum (breast-bone), which draws in air, puffing out the chest and it widens the shoulders. These combined effects make the person stand bigger. An exposed neck is also a sign of confidence. ‘Chin up’ is for these reasons a long-standing expression used to encourage someone to be brave. |

| active listening | head/face | attention, interest, attraction | When people are listening actively and responsively this shows in their facial expression and their head movements. The head and face are seen to respond fittingly and appropriately to what is being said by the speaker. Nodding is relevant to what is being said. Smiles and other expressions are relevant too. The head may tilt sideways. Mirroring of expressions may occur. Silences are used to absorb meaning. The eyes remain sharply focused on the eyes of the speaker, although at times might lower to look at the mouth, especially in male-female engagements. |

eyes | mouth | head | arms | hands | handshakes | legs and feet | personal space

Arms

Arms act as defensive barriers when across the body, and conversely indicate feelings of openness and security when in open positions, particularly when combined with open palms. Arms are quite reliable indicators of mood and feeling, especially when interpreted with other body language signals.

This provides a good opportunity to illustrate how signals combine to enable safer analysis.

For example:

- Crossed arms = possibly defensive

- Crossed arms + crossed legs = probably defensive

- Crossed arms + crossed legs + frowning + clenched fists = definitely defensive and probably hostile as well

While this might seem obvious written in simple language, it is not always so clear if your attention is on other matters.

Body language is more than just knowing the theory — it is being aware constantly of the signals people are giving.

| Non-Verbal Arm Signals | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Signal | Part of body | Possible meaning(s) |

Detailed explanation |

| crossed arms (folded arms) | arms | defensiveness, reluctance | Crossed arms represent a protective or separating barrier. This can be due to various causes, ranging from severe animosity or concern to mild boredom or being too tired to be interested and attentive. Crossed arms are a commonly exhibited signal by subordinates feeling threatened by bosses and figures of authority. Note. People also cross arms when they are feeling cold, so be careful not to misread this signal. |

| crossed arms with clenched fists | arms | hostile defensiveness | Clenched fists reinforce stubbornness, aggression or the lack of empathy indicated by crossed arms. |

| gripping own upper arms | arms | insecurity | Gripping upper arms, while folded, is effectively self-hugging. Self-hugging is an attempt to reassure unhappy or unsafe feelings. |

| one arm across body clasping other arm by side (female) | arms | nervousness | It is a ‘barrier’ protective signal and also self-hugging. |

| arms held behind body with hands clasped | arms | confidence, authority | As demonstrated by members of the royal family, armed forces officers, teachers, policemen, etc. |

| handbag held in front of body (female) | arms | nervousness | Another ‘barrier’ protective signal. |

| holding papers across chest (mainly male) | arms | nervousness | Another ‘barrier’ protective signal, especially when the arm is across the chest. |

| adjusting cuff, watchstrap, tie, etc., using an arm across the body | arms | nervousness | Another ‘barrier’ protective signal. |

| arms/hands covering genital region (male) | arms / hands | nervousness | Another ‘barrier’ protective signal. |

| holding a drink in front of body with both hands | arms / hands | nervousness | Another ‘barrier’ protective signal. |

| seated, holding drink on one side with hand from other side | arms / hands | nervousness | One arm rests on the table across the body, holding a drink (or pen, etc). Another ‘barrier’ protective signal. |

| touching or scratching shoulder using arm across body | arms / shoulder | nervousness | Another ‘barrier’ protective signal. |

eyes | mouth | head | arms | hands | handshakes | legs and feet | personal space

Hands

Body language involving hands is extensive. This is because hands are such expressive parts of the body and because hands interact with other parts of the body.

Hands contain many more nerve connections (to the brain) than most if not all other body parts. They are extremely expressive and flexible tools, so it is natural for hands to be used a lot in signalling consciously — as with emphasizing gestures — or unconsciously — as in a wide range of unintentional movements which indicate otherwise hidden feelings and thoughts.

A nose or an ear by itself can do little to signal a feeling but when a hand or finger is also involved then there is probably a signal of some sort.

Hands body language is used for various purposes, notably:

- Emphasis, (pointing, jabbing, and chopping actions)

- Illustration (drawing, shaping, mimicking actions or sizing things in the air — this big/long/wide/etc., phoning actions, etc)