|

Benjamin Franklin FRS FRSA FRSE |

|

|---|---|

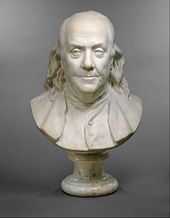

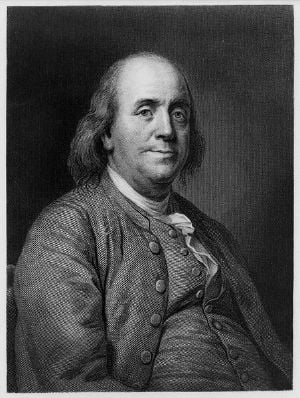

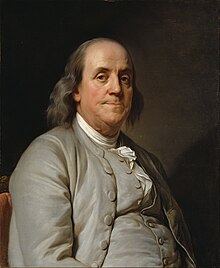

Benjamin Franklin by Joseph Duplessis, 1778 |

|

| 6th President of Pennsylvania | |

| In office October 18, 1785 – November 5, 1788 |

|

| Vice President | Charles Biddle Peter Muhlenberg David Redick |

| Preceded by | John Dickinson |

| Succeeded by | Thomas Mifflin |

| United States Minister to Sweden | |

| In office September 28, 1782 – April 3, 1783 |

|

| Appointed by | Congress of the Confederation |

| Preceded by | Position established |

| Succeeded by | Jonathan Russell |

| United States Minister to France | |

| In office March 23, 1779 – May 17, 1785 |

|

| Appointed by | Continental Congress |

| Preceded by | Position established |

| Succeeded by | Thomas Jefferson |

| 1st United States Postmaster General | |

| In office July 26, 1775 – November 7, 1776 |

|

| Preceded by | Position established |

| Succeeded by | Richard Bache |

| Delegate from Pennsylvania to Second Continental Congress | |

| In office May 1775 – October 1776 |

|

| Postmaster General of British America | |

| In office August 10, 1753 – January 31, 1774 |

|

| Preceded by | Position established |

| Succeeded by | Vacant |

| Speaker of the Pennsylvania Assembly | |

| In office May 1764 – October 1764 |

|

| Preceded by | Isaac Norris |

| Succeeded by | Isaac Norris |

| 2nd President of the University of Pennsylvania | |

| In office 1749–1754 |

|

| Preceded by | George Whitefield |

| Succeeded by | William Smith |

| Personal details | |

| Born | January 17, 1706 [O.S. January 6, 1705][Note 1] Boston, Massachusetts Bay, British America |

| Died | April 17, 1790 (aged 84) Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, U.S. |

| Resting place | Christ Church Burial Ground Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, U.S. |

| Political party | Independent |

| Spouse |

Deborah Read (m. ; died 1774) |

| Children |

|

| Parent(s) | Josiah Franklin Abiah Folger |

| Education | Boston Latin School |

| Signature |  |

Coat of arms of Benjamin Franklin |

|

Benjamin Franklin FRS FRSA FRSE (January 17, 1706 [O.S. January 6, 1705][Note 1] – April 17, 1790) was an American polymath who was active as a writer, scientist, inventor, statesman, diplomat, printer, publisher, forger and political philosopher.[1] Among the leading intellectuals of his time, Franklin was one of the Founding Fathers of the United States, a drafter and signer of the Declaration of Independence, and the first Postmaster General.[2]

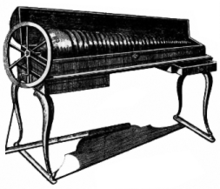

As a scientist, he was a major figure in the American Enlightenment and the history of physics for his studies of electricity, and for charting and naming the Gulf Stream current. As an inventor, he is known for the lightning rod, bifocals, and the Franklin stove, among others.[3] He founded many civic organizations, including the Library Company, Philadelphia’s first fire department,[4] and the University of Pennsylvania.[5]

Franklin earned the title of «The First American» for his early and indefatigable campaigning for colonial unity, and as an author and spokesman in London for several colonies. As the first U.S. ambassador to France, he exemplified the emerging American nation.[6] Franklin was foundational in defining the American ethos as a marriage of the practical values of thrift, hard work, education, community spirit, self-governing institutions, and opposition to authoritarianism both political and religious, with the scientific and tolerant values of the Enlightenment. In the words of historian Henry Steele Commager, «In Franklin could be merged the virtues of Puritanism without its defects, the illumination of the Enlightenment without its heat.»[7] Franklin has been called «the most accomplished American of his age and the most influential in inventing the type of society America would become.»[8]

Franklin became a successful newspaper editor and printer in Philadelphia, the leading city in the colonies, publishing the Pennsylvania Gazette at age 23.[9] He became wealthy publishing this and Poor Richard’s Almanack, which he wrote under the pseudonym «Richard Saunders».[10] After 1767, he was associated with the Pennsylvania Chronicle, a newspaper that was known for its revolutionary sentiments and criticisms of the policies of the British Parliament and the Crown.[11]

He pioneered and was the first president of the Academy and College of Philadelphia, which opened in 1751 and later became the University of Pennsylvania. He organized and was the first secretary of the American Philosophical Society and was elected president in 1769. Franklin became a national hero in America as an agent for several colonies when he spearheaded an effort in London to have the Parliament of Great Britain repeal the unpopular Stamp Act. An accomplished diplomat, he was widely admired among the French as American minister to Paris and was a major figure in the development of positive Franco–American relations. His efforts proved vital for the American Revolution in securing French aid.

He was promoted to deputy postmaster-general for the British colonies on August 10, 1753,[12] having been Philadelphia postmaster for many years, and this enabled him to set up the first national communications network. He was active in community affairs and colonial and state politics, as well as national and international affairs. From 1785 to 1788, he served as governor of Pennsylvania. He initially owned and dealt in slaves but, by the late 1750s, he began arguing against slavery, became an abolitionist, and promoted education and the integration of African Americans into U.S. society.

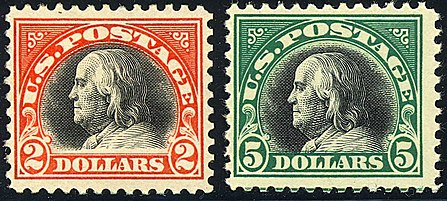

His life and legacy of scientific and political achievement, and his status as one of America’s most influential Founding Fathers, have seen Franklin honored more than two centuries after his death on the $100 bill, warships, and the names of many towns, counties, educational institutions, and corporations, as well as numerous cultural references and with a portrait in the Oval Office. Over his lifetime, Franklin wrote or received more than 30,000 letters and other documents, which since the 1950s have been collected in The Papers of Benjamin Franklin, published by both the American Philosophical Society and Yale University.

Ancestry

Benjamin Franklin’s father, Josiah Franklin, was a tallow chandler, soaper, and candlemaker. Josiah Franklin was born at Ecton, Northamptonshire, England, on December 23, 1657, the son of Thomas Franklin, a blacksmith and farmer, and his wife, Jane White. Benjamin’s father and all four of his grandparents were born in England.[13]

Josiah Franklin had a total of seventeen children with his two wives. He married his first wife, Anne Child, in about 1677 in Ecton and emigrated with her to Boston in 1683; they had three children before emigration and four after. Following her death, Josiah married Abiah Folger on July 9, 1689, in the Old South Meeting House by Reverend Samuel Willard, and had ten children with her. Benjamin, their eighth child, was Josiah Franklin’s fifteenth child overall, and his tenth and final son.[citation needed]

Benjamin Franklin’s mother, Abiah, was born in Nantucket, Massachusetts Bay Colony, on August 15, 1667, to Peter Folger, a miller and schoolteacher, and his wife, Mary Morrell Folger, a former indentured servant. Mary Folger came from a Puritan family that was among the first Pilgrims to flee to Massachusetts for religious freedom, sailing for Boston in 1635 after King Charles I of England had begun persecuting Puritans. Her father Peter was «the sort of rebel destined to transform colonial America.»[14] As clerk of the court, he was jailed for disobeying the local magistrate in defense of middle-class shopkeepers and artisans in conflict with wealthy landowners.[citation needed]

Early life

Boston

Franklin’s birthplace site directly across from the Old South Meeting House, commemorated by a bust atop the second-floor façade of this building, May 2008

Franklin was born on Milk Street in Boston, Massachusetts on January 17, 1706,[Note 1] and baptized at Old South Meeting House. As a child growing up along the Charles River, Franklin recalled that he was «generally the leader among the boys.»[17]

Franklin’s father wanted him to attend school with the clergy but only had enough money to send him to school for two years. He attended Boston Latin School but did not graduate; he continued his education through voracious reading. Although «his parents talked of the church as a career»[18] for Franklin, his schooling ended when he was ten. He worked for his father for a time, and at 12 he became an apprentice to his brother James, a printer, who taught him the printing trade. When Benjamin was 15, James founded The New-England Courant, which was one of the first American newspapers.[citation needed]

When denied the chance to write a letter to the paper for publication, Franklin adopted the pseudonym of «Silence Dogood», a middle-aged widow. Mrs. Dogood’s letters were published and became a subject of conversation around town. Neither James nor the Courant‘s readers were aware of the ruse, and James was unhappy with Benjamin when he discovered the popular correspondent was his younger brother. Franklin was an advocate of free speech from an early age. When his brother was jailed for three weeks in 1722 for publishing material unflattering to the governor, young Franklin took over the newspaper and had Mrs. Dogood (quoting Cato’s Letters) proclaim, «Without freedom of thought there can be no such thing as wisdom and no such thing as public liberty without freedom of speech.»[19] Franklin left his apprenticeship without his brother’s permission, and in so doing became a fugitive.[20][page needed]

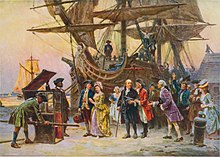

Move to Philadelphia

At age 17, Franklin ran away to Philadelphia, seeking a new start in a new city. When he first arrived, he worked in several printer shops around town, but he was not satisfied by the immediate prospects. After a few months, while working in a printing house, Pennsylvania governor Sir William Keith convinced him to go to London, ostensibly to acquire the equipment necessary for establishing another newspaper in Philadelphia. Discovering that Keith’s promises of backing a newspaper were empty, he worked as a typesetter in a printer’s shop in what is now the Church of St Bartholomew-the-Great in the Smithfield area of London. Following this, he returned to Philadelphia in 1726 with the help of Thomas Denham, a merchant who employed him as a clerk, shopkeeper, and bookkeeper in his business.[20][page needed]

Junto and library

La scuola della economia e della morale sketch of Franklin, 1825

In 1727, at age 21, Franklin formed the Junto, a group of «like minded aspiring artisans and tradesmen who hoped to improve themselves while they improved their community.» The Junto was a discussion group for issues of the day; it subsequently gave rise to many organizations in Philadelphia.[21] The Junto was modeled after English coffeehouses that Franklin knew well and which had become the center of the spread of Enlightenment ideas in Britain.[22][23]

Reading was a great pastime of the Junto, but books were rare and expensive. The members created a library initially assembled from their own books after Franklin wrote:

A proposition was made by me that since our books were often referr’d to in our disquisitions upon the inquiries, it might be convenient for us to have them altogether where we met, that upon occasion they might be consulted; and by thus clubbing our books to a common library, we should, while we lik’d to keep them together, have each of us the advantage of using the books of all the other members, which would be nearly as beneficial as if each owned the whole.[24][page needed]

This did not suffice, however. Franklin conceived the idea of a subscription library, which would pool the funds of the members to buy books for all to read. This was the birth of the Library Company of Philadelphia, whose charter he composed in 1731.[25]

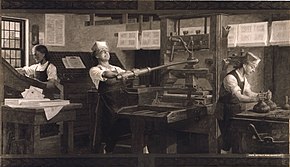

Newspaperman

Upon Denham’s death, Franklin returned to his former trade. In 1728, he set up a printing house in partnership with Hugh Meredith; the following year he became the publisher of a newspaper called The Pennsylvania Gazette. The Gazette gave Franklin a forum for agitation about a variety of local reforms and initiatives through printed essays and observations. Over time, his commentary, and his adroit cultivation of a positive image as an industrious and intellectual young man, earned him a great deal of social respect. But even after he achieved fame as a scientist and statesman, he habitually signed his letters with the unpretentious ‘B. Franklin, Printer.’[20]

In 1732, he published the first German-language newspaper in America – Die Philadelphische Zeitung – although it failed after only one year because four other newly founded German papers quickly dominated the newspaper market.[26] Franklin also printed Moravian religious books in German. He often visited Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, staying at the Moravian Sun Inn.[27] In a 1751 pamphlet on demographic growth and its implications for the Thirteen Colonies, he called the Pennsylvania Germans «Palatine Boors» who could never acquire the «Complexion» of Anglo-American settlers and referred to «Blacks and Tawneys» as weakening the social structure of the colonies. Although he apparently reconsidered shortly thereafter, and the phrases were omitted from all later printings of the pamphlet, his views may have played a role in his political defeat in 1764.[28]

According to Ralph Frasca, Franklin promoted the printing press as a device to instruct colonial Americans in moral virtue. Frasca argues he saw this as a service to God, because he understood moral virtue in terms of actions, thus, doing good provides a service to God. Despite his own moral lapses, Franklin saw himself as uniquely qualified to instruct Americans in morality. He tried to influence American moral life through the construction of a printing network based on a chain of partnerships from the Carolinas to New England. He thereby invented the first newspaper chain.[citation needed] It was more than a business venture, for like many publishers he believed that the press had a public-service duty.[29][30]

When he established himself in Philadelphia, shortly before 1730, the town boasted two «wretched little» news sheets, Andrew Bradford’s The American Weekly Mercury, and Samuel Keimer’s Universal Instructor in all Arts and Sciences, and Pennsylvania Gazette.[31] This instruction in all arts and sciences consisted of weekly extracts from Chambers’s Universal Dictionary. Franklin quickly did away with all of this when he took over the Instructor and made it The Pennsylvania Gazette. The Gazette soon became his characteristic organ, which he freely used for satire, for the play of his wit, even for sheer excess of mischief or of fun. From the first, he had a way of adapting his models to his own uses. The series of essays called «The Busy-Body», which he wrote for Bradford’s American Mercury in 1729, followed the general Addisonian form, already modified to suit homelier conditions. The thrifty Patience, in her busy little shop, complaining of the useless visitors who waste her valuable time, is related to the women who address Mr. Spectator. The Busy-Body himself is a true Censor Morum, as Isaac Bickerstaff had been in the Tatler. And a number of the fictitious characters, Ridentius, Eugenius, Cato, and Cretico, represent traditional 18th-century classicism. Even this Franklin could use for contemporary satire, since Cretico, the «sowre Philosopher», is evidently a portrait of his rival, Samuel Keimer.[32][page needed]

Franklin had mixed success in his plan to establish an inter-colonial network of newspapers that would produce a profit for him and disseminate virtue. Over the years he sponsored two dozen printers in Pennsylvania, South Carolina, New York, Connecticut and even the Caribbean. By 1753, 8 of the 15 English language newspapers in the colonies were published by him or his partners.[33] He began in Charleston, South Carolina, in 1731. After his second editor died, the widow Elizabeth Timothy took over and made it a success. She was one of the colonial era’s first woman printers.[34] For three decades Franklin maintained a close business relationship with her and her son Peter Timothy, who took over the South Carolina Gazette in 1746.[35] The Gazette was impartial in political debates, while creating the opportunity for public debate, which encouraged others to challenge authority. Timothy avoided blandness and crude bias and after 1765 increasingly took a patriotic stand in the growing crisis with Great Britain.[36] However, Franklin’s Connecticut Gazette (1755–68) proved unsuccessful.[37] As the Revolution approached, political strife slowly tore his network apart.[38]

Freemasonry

In 1730 or 1731, Franklin was initiated into the local Masonic lodge. He became a grand master in 1734, indicating his rapid rise to prominence in Pennsylvania.[39][40] The same year, he edited and published the first Masonic book in the Americas, a reprint of James Anderson’s Constitutions of the Free-Masons. He was the secretary of St. John’s Lodge in Philadelphia from 1735 to 1738.[40] Franklin remained a Freemason for the rest of his life.[41][42]

Common-law marriage to Deborah Read

At age 17 in 1723, Franklin proposed to 15-year-old Deborah Read while a boarder in the Read home. At that time, Deborah’s mother was wary of allowing her young daughter to marry Franklin, who was on his way to London at Governor Keith’s request, and also because of his financial instability. Her own husband had recently died, and she declined Franklin’s request to marry her daughter.[20]

While Franklin was in London, his trip was extended, and there were problems with the governor’s promises of support. Perhaps because of the circumstances of this delay, Deborah married a man named John Rodgers. This proved to be a regrettable decision. Rodgers shortly avoided his debts and prosecution by fleeing to Barbados with her dowry, leaving her behind. Rodgers’s fate was unknown, and because of bigamy laws, Deborah was not free to remarry.[citation needed]

Franklin established a common-law marriage with Deborah on September 1, 1730. They took in his recently acknowledged illegitimate young son and raised him in their household. They had two children together. Their son, Francis Folger Franklin, was born in October 1732 and died of smallpox in 1736. Their daughter, Sarah «Sally» Franklin, was born in 1743 and eventually married Richard Bache.[43]

Deborah’s fear of the sea meant that she never accompanied Franklin on any of his extended trips to Europe; another possible reason why they spent much time apart is that he may have blamed her for possibly preventing their son Francis from being inoculated against the disease that subsequently killed him.[44] Deborah wrote to him in November 1769, saying she was ill due to «dissatisfied distress» from his prolonged absence, but he did not return until his business was done.[45] Deborah Read Franklin died of a stroke on December 14, 1774, while Franklin was on an extended mission to Great Britain; he returned in 1775.[46]

William Franklin

In 1730, 24-year-old Franklin publicly acknowledged his illegitimate son William and raised him in his household. William was born on February 22, 1730, but his mother’s identity is unknown.[47] He was educated in Philadelphia and beginning at about age 30 studied law in London in the early 1760s. William himself fathered an illegitimate son, William Temple Franklin, born on the same day and month: February 22, 1760.[48] The boy’s mother was never identified, and he was placed in foster care. In 1762, the elder William Franklin married Elizabeth Downes, daughter of a planter from Barbados, in London. In 1763, he was appointed as the last royal governor of New Jersey.

A Loyalist to the king, William Franklin saw his relations with father Benjamin eventually break down over their differences about the American Revolutionary War, as Benjamin Franklin could never accept William’s position. Deposed in 1776 by the revolutionary government of New Jersey, William was placed under house arrest at his home in Perth Amboy for six months. After the Declaration of Independence, he was formally taken into custody by order of the Provincial Congress of New Jersey, an entity which he refused to recognize, regarding it as an «illegal assembly».[49] He was incarcerated in Connecticut for two years, in Wallingford and Middletown, and, after being caught surreptitiously engaging Americans into supporting the Loyalist cause, was held in solitary confinement at Litchfield for eight months. When finally released in a prisoner exchange in 1778, he moved to New York City, which was occupied by the British at the time.[50]

While in New York City, he became leader of the Board of Associated Loyalists, a quasi-military organization chartered by King George III and headquartered in New York City. They initiated guerrilla forays into New Jersey, southern Connecticut, and New York counties north of the city.[51] When British troops evacuated from New York, William Franklin left with them and sailed to England. He settled in London, never to return to North America. In the preliminary peace talks in 1782 with Britain, «… Benjamin Franklin insisted that loyalists who had borne arms against the United States would be excluded from this plea (that they be given a general pardon). He was undoubtedly thinking of William Franklin.»[52][unreliable source?]

Franklin’s The General Magazine and Historical Chronicle (January 1741)

In 1733, Franklin began to publish the noted Poor Richard’s Almanack (with content both original and borrowed) under the pseudonym Richard Saunders, on which much of his popular reputation is based. He frequently wrote under pseudonyms. He had developed a distinct, signature style that was plain, pragmatic and had a sly, soft but self-deprecating tone with declarative sentences.[53] Although it was no secret that he was the author, his Richard Saunders character repeatedly denied it. «Poor Richard’s Proverbs», adages from this almanac, such as «A penny saved is twopence dear» (often misquoted as «A penny saved is a penny earned») and «Fish and visitors stink in three days», remain common quotations in the modern world. Wisdom in folk society meant the ability to provide an apt adage for any occasion, and his readers became well prepared. He sold about ten thousand copies per year—it became an institution.[54] In 1741, Franklin began publishing The General Magazine and Historical Chronicle for all the British Plantations in America. He used the heraldic badge of the Prince of Wales as the cover illustration.

In 1758, the year he ceased writing for the Almanack, he printed Father Abraham’s Sermon, also known as The Way to Wealth. Franklin’s autobiography, begun in 1771 but published after his death, has become one of the classics of the genre.[citation needed] He wrote a letter, «Advice to a Friend on Choosing a Mistress», dated June 25, 1745, in which he gives advice to a young man about channeling sexual urges. Due to its licentious nature, it was not published in collections of his papers during the nineteenth century. Federal court decisions from the mid-to-late twentieth century cited the document as a reason for overturning obscenity laws, using it to make a case against censorship.[55]

Public life

Early steps in Pennsylvania

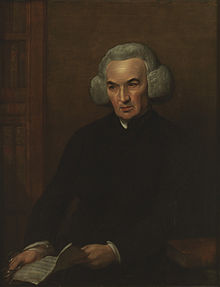

Portrait of Franklin c. 1746–1750,[Note 2] by Robert Feke. Widely believed to be the earliest known painting of Franklin.[56][57]

In 1736, Franklin created the Union Fire Company, one of the first volunteer firefighting companies in America. In the same year, he printed a new currency for New Jersey based on innovative anti-counterfeiting techniques he had devised. Throughout his career, he was an advocate for paper money, publishing A Modest Enquiry into the Nature and Necessity of a Paper Currency in 1729, and his printer printed money. He was influential in the more restrained and thus successful monetary experiments in the Middle Colonies, which stopped deflation without causing excessive inflation. In 1766, he made a case for paper money to the British House of Commons.[58]

As he matured, Franklin began to concern himself more with public affairs. In 1743, he first devised a scheme for the Academy, Charity School, and College of Philadelphia. However, the person he had in mind to run the academy, Rev. Richard Peters, refused and Franklin put his ideas away until 1749 when he printed his own pamphlet, Proposals Relating to the Education of Youth in Pensilvania.[59]: 30 He was appointed president of the Academy on November 13, 1749; the academy and the charity school opened in 1751.[60]

In 1743, he founded the American Philosophical Society to help scientific men discuss their discoveries and theories. He began the electrical research that, along with other scientific inquiries, would occupy him for the rest of his life, in between bouts of politics and moneymaking.[20]

During King George’s War, Franklin raised a militia called the Association for General Defense because the legislators of the city had decided to take no action to defend Philadelphia «either by erecting fortifications or building Ships of War». He raised money to create earthwork defenses and buy artillery. The largest of these was the «Association Battery» or «Grand Battery» of 50 guns.[61][62]

In 1747, Franklin (already a very wealthy man) retired from printing and went into other businesses.[63] He formed a partnership with his foreman, David Hall, which provided Franklin with half of the shop’s profits for 18 years. This lucrative business arrangement provided leisure time for study, and in a few years he had made many new discoveries.

Franklin became involved in Philadelphia politics and rapidly progressed. In October 1748, he was selected as a councilman; in June 1749, he became a justice of the peace for Philadelphia; and in 1751, he was elected to the Pennsylvania Assembly. On August 10, 1753, he was appointed deputy postmaster-general of British North America. His most notable service in domestic politics was his reform of the postal system, with mail sent out every week.[20]

In 1751, Franklin and Thomas Bond obtained a charter from the Pennsylvania legislature to establish a hospital. Pennsylvania Hospital was the first hospital in the colonies.[64] In 1752, Franklin organized the Philadelphia Contributionship, the Colonies’ first homeowner’s insurance company.[65][66]

Between 1750 and 1753, the «educational triumvirate»[67] of Franklin, Samuel Johnson of Stratford, Connecticut, and schoolteacher William Smith built on Franklin’s initial scheme and created what Bishop James Madison, president of the College of William & Mary, called a «new-model»[68] plan or style of American college. Franklin solicited, printed in 1752, and promoted an American textbook of moral philosophy by Samuel Johnson, titled Elementa Philosophica,[69] to be taught in the new colleges. In June 1753, Johnson, Franklin, and Smith met in Stratford.[70] They decided the new-model college would focus on the professions, with classes taught in English instead of Latin, have subject matter experts as professors instead of one tutor leading a class for four years, and there would be no religious test for admission.[71] Johnson went on to found King’s College (now Columbia University) in New York City in 1754, while Franklin hired Smith as provost of the College of Philadelphia, which opened in 1755. At its first commencement, on May 17, 1757, seven men graduated; six with a Bachelor of Arts and one with a Master of Arts. It was later merged with the University of the State of Pennsylvania to become the University of Pennsylvania. The college was to become influential in guiding the founding documents of the United States: in the Continental Congress, for example, over one-third of the college-affiliated men who contributed to the Declaration of Independence between September 4, 1774, and July 4, 1776, were affiliated with the college.[72]

Seal of the College of Philadelphia

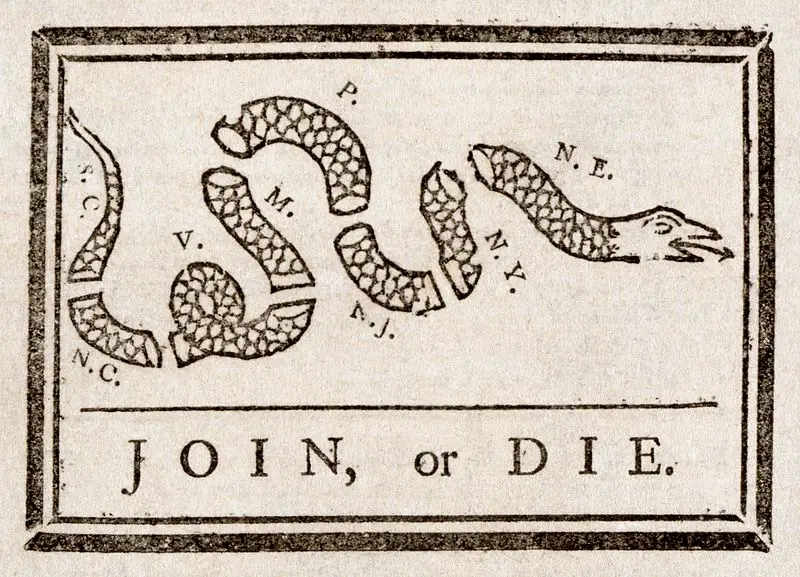

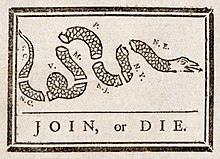

In 1754, he headed the Pennsylvania delegation to the Albany Congress. This meeting of several colonies had been requested by the Board of Trade in England to improve relations with the Indians and defense against the French. Franklin proposed a broad Plan of Union for the colonies. While the plan was not adopted, elements of it found their way into the Articles of Confederation and the Constitution.[73]

In 1753, both Harvard[74] and Yale[75] awarded him honorary master of arts degrees.[76] In 1756, he received an honorary Master of Arts degree from the College of William & Mary.[77] Later in 1756, Franklin organized the Pennsylvania Militia. He used Tun Tavern as a gathering place to recruit a regiment of soldiers to go into battle against the Native American uprisings that beset the American colonies.[78]

Postmaster

First U. S. postage stamp, issue of 1847, honoring Benjamin Franklin

Well known as a printer and publisher, Franklin was appointed postmaster of Philadelphia in 1737, holding the office until 1753, when he and publisher William Hunter were named deputy postmasters–general of British North America, the first to hold the office. (Joint appointments were standard at the time, for political reasons.) He was responsible for the British colonies from Pennsylvania north and east, as far as the island of Newfoundland. A post office for local and outgoing mail had been established in Halifax, Nova Scotia, by local stationer Benjamin Leigh, on April 23, 1754, but service was irregular. Franklin opened the first post office to offer regular, monthly mail in Halifax on December 9, 1755. Meantime, Hunter became postal administrator in Williamsburg, Virginia, and oversaw areas south of Annapolis, Maryland. Franklin reorganized the service’s accounting system and improved speed of delivery between Philadelphia, New York, and Boston. By 1761, efficiencies led to the first profits for the colonial post office.[79]

When the lands of New France were ceded to the British under the Treaty of Paris in 1763, the British province of Quebec was created among them, and Franklin saw mail service expanded between Montreal, Trois-Rivières, Quebec City, and New York. For the greater part of his appointment, he lived in England (from 1757 to 1762, and again from 1764 to 1774)—about three-quarters of his term.[80] Eventually, his sympathies for the rebel cause in the American Revolution led to his dismissal on January 31, 1774.[81]

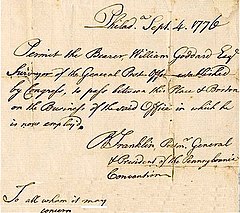

Pass, signed by Postmaster General Benjamin Franklin, gave William Goddard the authority to travel as needed to investigate and inspect postal routes and protect the mail.[82]

On July 26, 1775, the Second Continental Congress established the United States Post Office and named Franklin as the first United States postmaster general. He had been a postmaster for decades and was a natural choice for the position.[83] He had just returned from England and was appointed chairman of a Committee of Investigation to establish a postal system. The report of the committee, providing for the appointment of a postmaster general for the 13 American colonies, was considered by the Continental Congress on July 25 and 26. On July 26, 1775, Franklin was appointed postmaster general, the first appointed under the Continental Congress. His apprentice, William Goddard, felt that his ideas were mostly responsible for shaping the postal system and that the appointment should have gone to him, but he graciously conceded it to Franklin, 36 years his senior.[82] Franklin, however, appointed Goddard as Surveyor of the Posts, issued him a signed pass, and directed him to investigate and inspect the various post offices and mail routes as he saw fit.[84][85] The newly established postal system became the United States Post Office, a system that continues to operate today.[86]

Decades in London

From the mid-1750s to the mid-1770s, Franklin spent much of his time in London.[citation needed]

Political work

In 1757, he was sent to England by the Pennsylvania Assembly as a colonial agent to protest against the political influence of the Penn family, the proprietors of the colony. He remained there for five years, striving to end the proprietors’ prerogative to overturn legislation from the elected Assembly and their exemption from paying taxes on their land. His lack of influential allies in Whitehall led to the failure of this mission.[citation needed]

Pennsylvania colonial currency printed by Franklin and David Hall in 1764

At this time, many members of the Pennsylvania Assembly were feuding with William Penn’s heirs, who controlled the colony as proprietors. After his return to the colony, Franklin led the «anti-proprietary party» in the struggle against the Penn family and was elected Speaker of the Pennsylvania House in May 1764. His call for a change from proprietary to royal government was a rare political miscalculation, however: Pennsylvanians worried that such a move would endanger their political and religious freedoms. Because of these fears and because of political attacks on his character, Franklin lost his seat in the October 1764 Assembly elections. The anti-proprietary party dispatched him to England again to continue the struggle against the Penn family proprietorship. During this trip, events drastically changed the nature of his mission.[87]

In London, Franklin opposed the 1765 Stamp Act. Unable to prevent its passage, he made another political miscalculation and recommended a friend to the post of stamp distributor for Pennsylvania. Pennsylvanians were outraged, believing that he had supported the measure all along, and threatened to destroy his home in Philadelphia. Franklin soon learned of the extent of colonial resistance to the Stamp Act, and he testified during the House of Commons proceedings that led to its repeal.[88] With this, Franklin suddenly emerged as the leading spokesman for American interests in England. He wrote popular essays on behalf of the colonies. Georgia, New Jersey, and Massachusetts also appointed him as their agent to the Crown.[87]

Franklin in London, 1767, wearing a blue suit with elaborate gold braid and buttons, a far cry from the simple dress he affected at the French court in later years. Painting by David Martin, displayed in the White House.

During his lengthy missions to London between 1757 and 1775, Franklin lodged in a house on Craven Street, just off the Strand in central London.[89] During his stays there, he developed a close friendship with his landlady, Margaret Stevenson, and her circle of friends and relations, in particular, her daughter Mary, who was more often known as Polly. The house is now a museum known as the Benjamin Franklin House. Whilst in London, Franklin became involved in radical politics. He belonged to a gentleman’s club (which he called «the honest Whigs»), which held stated meetings, and included members such as Richard Price, the minister of Newington Green Unitarian Church who ignited the Revolution controversy, and Andrew Kippis.[90]

Scientific work

In 1756, Franklin had become a member of the Society for the Encouragement of Arts, Manufactures & Commerce (now the Royal Society of Arts), which had been founded in 1754. After his return to the United States in 1775, he became the Society’s Corresponding Member, continuing a close connection. The Royal Society of Arts instituted a Benjamin Franklin Medal in 1956 to commemorate the 250th anniversary of his birth and the 200th anniversary of his membership of the RSA.[91]

The study of natural philosophy (referred today as science in general) drew him into overlapping circles of acquaintance. Franklin was, for example, a corresponding member of the Lunar Society of Birmingham.[92] In 1759, the University of St Andrews awarded him an honorary doctorate in recognition of his accomplishments.[93] In October 1759, he was granted Freedom of the Borough of St Andrews.[94] He was also awarded an honorary doctorate by Oxford University in 1762. Because of these honors, he was often addressed as «Dr. Franklin».[1]

While living in London in 1768, he developed a phonetic alphabet in A Scheme for a new Alphabet and a Reformed Mode of Spelling. This reformed alphabet discarded six letters he regarded as redundant (c, j, q, w, x, and y), and substituted six new letters for sounds he felt lacked letters of their own. This alphabet never caught on, and he eventually lost interest.[95]

Travels around Europe

Franklin used London as a base to travel. In 1771, he made short journeys through different parts of England, staying with Joseph Priestley at Leeds, Thomas Percival at Manchester and Erasmus Darwin at Lichfield.[96] In Scotland, he spent five days with Lord Kames near Stirling and stayed for three weeks with David Hume in Edinburgh. In 1759, he visited Edinburgh with his son and later reported that he considered his six weeks in Scotland «six weeks of the densest happiness I have met with in any part of my life».[97]

In Ireland, he stayed with Lord Hillsborough. Franklin noted of him that «all the plausible behaviour I have described is meant only, by patting and stroking the horse, to make him more patient, while the reins are drawn tighter, and the spurs set deeper into his sides.»[98] In Dublin, Franklin was invited to sit with the members of the Irish Parliament rather than in the gallery. He was the first American to receive this honor.[96] While touring Ireland, he was deeply moved by the level of poverty he witnessed. The economy of the Kingdom of Ireland was affected by the same trade regulations and laws that governed the Thirteen Colonies. He feared that the American colonies could eventually come to the same level of poverty if the regulations and laws continued to apply to them.[99]

Franklin spent two months in German lands in 1766, but his connections to the country stretched across a lifetime. He declared a debt of gratitude to German scientist Otto von Guericke for his early studies of electricity. Franklin also co-authored the first treaty of friendship between Prussia and America in 1785.[100] In September 1767, he visited Paris with his usual traveling partner, Sir John Pringle, 1st Baronet. News of his electrical discoveries was widespread in France. His reputation meant that he was introduced to many influential scientists and politicians, and also to King Louis XV.[5]

Defending the American cause

One line of argument in Parliament was that Americans should pay a share of the costs of the French and Indian War and therefore taxes should be levied on them. Franklin became the American spokesman in highly publicized testimony in Parliament in 1766. He stated that Americans already contributed heavily to the defense of the Empire. He said local governments had raised, outfitted and paid 25,000 soldiers to fight France—as many as Britain itself sent—and spent many millions from American treasuries doing so in the French and Indian War alone.[101][102]

In 1772, Franklin obtained private letters of Thomas Hutchinson and Andrew Oliver, governor and lieutenant governor of the Province of Massachusetts Bay, proving that they had encouraged the Crown to crack down on Bostonians. Franklin sent them to America, where they escalated tensions. The letters were finally leaked to the public in the Boston Gazette in mid-June 1773,[103] causing a political firestorm in Massachusetts and raising significant questions in England.[104] The British began to regard him as the fomenter of serious trouble. Hopes for a peaceful solution ended as he was systematically ridiculed and humiliated by Solicitor-General Alexander Wedderburn, before the Privy Council on January 29, 1774. He returned to Philadelphia in March 1775, and abandoned his accommodationist stance.[105]

In 1773, Franklin published two of his most celebrated pro-American satirical essays: «Rules by Which a Great Empire May Be Reduced to a Small One», and «An Edict by the King of Prussia».[106]

Agent for British and Hellfire Club membership

Franklin is known to have occasionally attended the Hellfire Club’s meetings during 1758 as a non-member during his time in England. However, some authors and historians would argue he was in fact a British spy. As there are no records left (having been burned in 1774[107]), many of these members are just assumed or linked by letters sent to each other.[108] One early proponent that Franklin was a member of the Hellfire Club and a double agent is the historian Donald McCormick,[109] who has a history of making controversial claims.[110]

Coming of revolution

In 1763, soon after Franklin returned to Pennsylvania from England for the first time, the western frontier was engulfed in a bitter war known as Pontiac’s Rebellion. The Paxton Boys, a group of settlers convinced that the Pennsylvania government was not doing enough to protect them from American Indian raids, murdered a group of peaceful Susquehannock Indians and marched on Philadelphia. Franklin helped to organize a local militia to defend the capital against the mob. He met with the Paxton leaders and persuaded them to disperse. Franklin wrote a scathing attack against the racial prejudice of the Paxton Boys. «If an Indian injures me», he asked, «does it follow that I may revenge that Injury on all Indians?»[111]

He provided an early response to British surveillance through his own network of counter-surveillance and manipulation. «He waged a public relations campaign, secured secret aid, played a role in privateering expeditions, and churned out effective and inflammatory propaganda.»[112]

Declaration of Independence

By the time Franklin arrived in Philadelphia on May 5, 1775, after his second mission to Great Britain, the American Revolution had begun—with skirmishes breaking out between colonials and British at Lexington and Concord. The New England militia had forced the main British army to remain inside Boston.[citation needed] The Pennsylvania Assembly unanimously chose Franklin as their delegate to the Second Continental Congress.[citation needed] In June 1776, he was appointed a member of the Committee of Five that drafted the Declaration of Independence. Although he was temporarily disabled by gout and unable to attend most meetings of the committee,[citation needed] he made several «small but important» changes to the draft sent to him by Thomas Jefferson.[114]

At the signing, he is quoted as having replied to a comment by John Hancock that they must all hang together: «Yes, we must, indeed, all hang together, or most assuredly we shall all hang separately.»[115]

Ambassador to France (1776–1785)

Franklin, in his fur hat, charmed the French with what they perceived as rustic New World genius.[Note 3]

On October 26, 1776, Franklin was dispatched to France as commissioner for the United States.[116] He took with him as secretary his 16-year-old grandson, William Temple Franklin. They lived in a home in the Parisian suburb of Passy, donated by Jacques-Donatien Le Ray de Chaumont, who supported the United States. Franklin remained in France until 1785. He conducted the affairs of his country toward the French nation with great success, which included securing a critical military alliance in 1778 and signing the 1783 Treaty of Paris.[117]

Among his associates in France was Honoré Gabriel Riqueti, comte de Mirabeau—a French Revolutionary writer, orator and statesman who in 1791 was elected president of the National Assembly.[118] In July 1784, Franklin met with Mirabeau and contributed anonymous materials that the Frenchman used in his first signed work: Considerations sur l’ordre de Cincinnatus.[119] The publication was critical of the Society of the Cincinnati, established in the United States. Franklin and Mirabeau thought of it as a «noble order», inconsistent with the egalitarian ideals of the new republic.[120]

During his stay in France, he was active as a Freemason, serving as venerable master of the lodge Les Neuf Sœurs from 1779 until 1781. In 1784, when Franz Mesmer began to publicize his theory of «animal magnetism» which was considered offensive by many, Louis XVI appointed a commission to investigate it. These included the chemist Antoine Lavoisier, the physician Joseph-Ignace Guillotin, the astronomer Jean Sylvain Bailly, and Franklin.[121] In doing so, the committee concluded, through blind trials that mesmerism only seemed to work when the subjects expected it, which discredited mesmerism and became the first major demonstration of the placebo effect, which was described at that time as «imagination».[122] In 1781, he was elected a fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences.[123]

Franklin’s advocacy for religious tolerance in France contributed to arguments made by French philosophers and politicians that resulted in Louis XVI’s signing of the Edict of Versailles in November 1787. This edict effectively nullified the Edict of Fontainebleau, which had denied non-Catholics civil status and the right to openly practice their faith.[124]

Franklin also served as American minister to Sweden, although he never visited that country.[125] He negotiated a treaty that was signed in April 1783. On August 27, 1783, in Paris, he witnessed the world’s first hydrogen balloon flight.[126] Le Globe, created by professor Jacques Charles and Les Frères Robert, was watched by a vast crowd as it rose from the Champ de Mars (now the site of the Eiffel Tower).[127] Franklin became so enthusiastic that he subscribed financially to the next project to build a manned hydrogen balloon.[128] On December 1, 1783, Franklin was seated in the special enclosure for honored guests when La Charlière took off from the Jardin des Tuileries, piloted by Charles and Nicolas-Louis Robert.[126][129]

Return to America

When he returned home in 1785, Franklin occupied a position second only to that of George Washington as the champion of American independence. He returned from France with an unexplained shortage of 100,000 pounds in Congressional funds. In response to a question from a member of Congress about this, Franklin, quoting the Bible, quipped, «Muzzle not the ox that treadeth out his master’s grain.» The missing funds were never again mentioned in Congress.[131]

Le Ray honored him with a commissioned portrait painted by Joseph Duplessis, which now hangs in the National Portrait Gallery of the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C. After his return, Franklin became an abolitionist and freed his two slaves. He eventually became president of the Pennsylvania Abolition Society.[99]

President of Pennsylvania and Delegate to the Constitutional convention

Special balloting conducted October 18, 1785, unanimously elected him the sixth president of the Supreme Executive Council of Pennsylvania, replacing John Dickinson. The office was practically that of the governor. He held that office for slightly over three years, longer than any other, and served the constitutional limit of three full terms. Shortly after his initial election, he was re-elected to a full term on October 29, 1785, and again in the fall of 1786 and on October 31, 1787. In that capacity, he served as host to the Constitutional Convention of 1787 in Philadelphia.[132]

He also served as a delegate to the Convention. It was primarily an honorary position and he seldom engaged in debate.

Death

Franklin’s grave, Philadelphia

Franklin suffered from obesity throughout his middle-age and later years, which resulted in multiple health problems, particularly gout, which worsened as he aged. In poor health during the signing of the US Constitution in 1787, he was rarely seen in public from then until his death.[citation needed]

Benjamin Franklin died from pleuritic attack[133] at his home in Philadelphia on April 17, 1790.[134] He was aged 84 at the time of his death. His last words were reportedly, «a dying man can do nothing easy», to his daughter after she suggested that he change position in bed and lie on his side so he could breathe more easily.[135][136] Franklin’s death is described in the book The Life of Benjamin Franklin, quoting from the account of John Jones:

… when the pain and difficulty of breathing entirely left him, and his family were flattering themselves with the hopes of his recovery, when an imposthume, which had formed itself in his lungs, suddenly burst, and discharged a quantity of matter, which he continued to throw up while he had power; but, as that failed, the organs of respiration became gradually oppressed; a calm, lethargic state succeeded; and on the 17th instant (April 1790), about eleven o’clock at night, he quietly expired, closing a long and useful life of eighty-four years and three months.[137]

Approximately 20,000 people attended his funeral. He was interred in Christ Church Burial Ground in Philadelphia.[138][139] Upon learning of his death, the Constitutional Assembly in Revolutionary France entered into a state of mourning for a period of three days, and memorial services were conducted in honor of Franklin throughout the country.[140] In 1728, aged 22, Franklin wrote what he hoped would be his own epitaph:

The Body of B. Franklin Printer; Like the Cover of an old Book, Its Contents torn out, And stript of its Lettering and Gilding, Lies here, Food for Worms. But the Work shall not be wholly lost: For it will, as he believ’d, appear once more, In a new & more perfect Edition, Corrected and Amended By the Author.[141]

Franklin’s actual grave, however, as he specified in his final will, simply reads «Benjamin and Deborah Franklin».[142]

Inventions and scientific inquiries

Franklin was a prodigious inventor. Among his many creations were the lightning rod, Franklin stove, bifocal glasses and the flexible urinary catheter. He never patented his inventions; in his autobiography he wrote, «… as we enjoy great advantages from the inventions of others, we should be glad of an opportunity to serve others by any invention of ours; and this we should do freely and generously.»[143]

Electricity

Franklin started exploring the phenomenon of electricity in the 1740s, after he met the itinerant lecturer Archibald Spencer who used static electricity in his demonstrations.[144] He proposed that «vitreous» and «resinous» electricity were not different types of «electrical fluid» (as electricity was called then), but the same «fluid» under different pressures. (The same proposal was made independently that same year by William Watson.) He was the first to label them as positive and negative respectively,[145][146] and he was the first to discover the principle of conservation of charge.[147] In 1748, he constructed a multiple plate capacitor, that he called an «electrical battery» (not a true battery like Volta’s pile) by placing eleven panes of glass sandwiched between lead plates, suspended with silk cords and connected by wires.[148]

In pursuit of more pragmatic uses for electricity, remarking in spring 1749 that he felt «chagrin’d a little» that his experiments had heretofore resulted in «Nothing in this Way of Use to Mankind», he planned a practical demonstration. He proposed a dinner party where a turkey was to be killed via electric shock and roasted on an electrical spit.[149] After having prepared several turkeys this way, he noted that «the birds kill’d in this manner eat uncommonly tender.»[150] Franklin recounted that in the process of one of these experiments, he was shocked by a pair of Leyden jars, resulting in numbness in his arms that persisted for one evening, noting «I am Ashamed to have been Guilty of so Notorious a Blunder.»[151]

Franklin briefly investigated electrotherapy, including the use of the electric bath. This work led to the field becoming widely known.[152] In recognition of his work with electricity, he received the Royal Society’s Copley Medal in 1753, and in 1756, he became one of the few 18th-century Americans elected a fellow of the Society. The CGS unit of electric charge has been named after him: one franklin (Fr) is equal to one statcoulomb.

Franklin advised Harvard University in its acquisition of new electrical laboratory apparatus after the complete loss of its original collection, in a fire that destroyed the original Harvard Hall in 1764. The collection he assembled later became part of the Harvard Collection of Historical Scientific Instruments, now on public display in its Science Center.[153]

Kite experiment and lightning rod

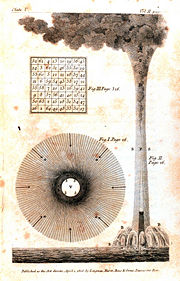

Franklin and Electricity vignette engraved by the BEP (c. 1860)

Franklin published a proposal for an experiment to prove that lightning is electricity by flying a kite in a storm. On May 10, 1752, Thomas-François Dalibard of France conducted Franklin’s experiment using a 40-foot-tall (12 m) iron rod instead of a kite, and he extracted electrical sparks from a cloud. On June 15, 1752, Franklin may possibly have conducted his well-known kite experiment in Philadelphia, successfully extracting sparks from a cloud. He described the experiment in his newspaper, The Pennsylvania Gazette, on October 19, 1752,[154][155] without mentioning that he himself had performed it.[156] This account was read to the Royal Society on December 21 and printed as such in the Philosophical Transactions.[157] Joseph Priestley published an account with additional details in his 1767 History and Present Status of Electricity. Franklin was careful to stand on an insulator, keeping dry under a roof to avoid the danger of electric shock.[158] Others, such as Georg Wilhelm Richmann in Russia, were indeed electrocuted in performing lightning experiments during the months immediately following his experiment.[159]

In his writings, Franklin indicates that he was aware of the dangers and offered alternative ways to demonstrate that lightning was electrical, as shown by his use of the concept of electrical ground. He did not perform this experiment in the way that is often pictured in popular literature, flying the kite and waiting to be struck by lightning, as it would have been dangerous.[160] Instead he used the kite to collect some electric charge from a storm cloud, showing that lightning was electrical.[161] On October 19, 1752, in a letter to England with directions for repeating the experiment, he wrote:

When rain has wet the kite twine so that it can conduct the electric fire freely, you will find it streams out plentifully from the key at the approach of your knuckle, and with this key a phial, or Leyden jar, may be charged: and from electric fire thus obtained spirits may be kindled, and all other electric experiments [may be] performed which are usually done by the help of a rubber glass globe or tube; and therefore the sameness of the electrical matter with that of lightening [sic] completely demonstrated.[161]

Franklin’s electrical experiments led to his invention of the lightning rod. He said that conductors with a sharp[162] rather than a smooth point could discharge silently and at a far greater distance. He surmised that this could help protect buildings from lightning by attaching «upright Rods of Iron, made sharp as a Needle and gilt to prevent Rusting, and from the Foot of those Rods a Wire down the outside of the Building into the Ground; … Would not these pointed Rods probably draw the Electrical Fire silently out of a Cloud before it came nigh enough to strike, and thereby secure us from that most sudden and terrible Mischief!» Following a series of experiments on Franklin’s own house, lightning rods were installed on the Academy of Philadelphia (later the University of Pennsylvania) and the Pennsylvania State House (later Independence Hall) in 1752.[163]

Population studies

Franklin had a major influence on the emerging science of demography or population studies.[164] In the 1730s and 1740s, he began taking notes on population growth, finding that the American population had the fastest growth rate on Earth.[165] Emphasizing that population growth depended on food supplies, he emphasized the abundance of food and available farmland in America. He calculated that America’s population was doubling every 20 years and would surpass that of England in a century.[166] In 1751, he drafted Observations concerning the Increase of Mankind, Peopling of Countries, etc. Four years later, it was anonymously printed in Boston and was quickly reproduced in Britain, where it influenced the economist Adam Smith and later the demographer Thomas Malthus, who credited Franklin for discovering a rule of population growth.[167] Franklin’s predictions how British mercantilism was unsustainable alarmed British leaders who did not want to be surpassed by the colonies, so they became more willing to impose restrictions on the colonial economy.[168]

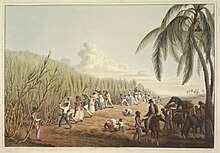

Kammen (1990) and Drake (2011) say Franklin’s Observations concerning the Increase of Mankind (1755) stands alongside Ezra Stiles’ «Discourse on Christian Union» (1760) as the leading works of 18th-century Anglo-American demography; Drake credits Franklin’s «wide readership and prophetic insight».[169][170] Franklin was also a pioneer in the study of slave demography, as shown in his 1755 essay.[171] In his capacity as a farmer, he wrote at least one critique about the negative consequences of price controls, trade restrictions, and subsidy of the poor. This is succinctly preserved in his letter to the London Chronicle published November 29, 1766, titled «On the Price of Corn, and Management of the poor».[172]

Oceanography

As deputy postmaster, Franklin became interested in North Atlantic Ocean circulation patterns. While in England in 1768, he heard a complaint from the Colonial Board of Customs: Why did it take British packet ships carrying mail several weeks longer to reach New York than it took an average merchant ship to reach Newport, Rhode Island? The merchantmen had a longer and more complex voyage because they left from London, while the packets left from Falmouth in Cornwall.[173] Franklin put the question to his cousin Timothy Folger, a Nantucket whaler captain, who told him that merchant ships routinely avoided a strong eastbound mid-ocean current. The mail packet captains sailed dead into it, thus fighting an adverse current of 3 miles per hour (5 km/h). Franklin worked with Folger and other experienced ship captains, learning enough to chart the current and name it the Gulf Stream, by which it is still known today.[174]

Franklin published his Gulf Stream chart in 1770 in England, where it was ignored. Subsequent versions were printed in France in 1778 and the U.S. in 1786. The British original edition of the chart had been so thoroughly ignored that everyone assumed it was lost forever until Phil Richardson, a Woods Hole oceanographer and Gulf Stream expert, discovered it in the Bibliothèque Nationale in Paris in 1980.[175][176] This find received front-page coverage in The New York Times.[177] It took many years for British sea captains to adopt Franklin’s advice on navigating the current; once they did, they were able to trim two weeks from their sailing time.[178][179] In 1853, the oceanographer and cartographer Matthew Fontaine Maury noted that while Franklin charted and codified the Gulf Stream, he did not discover it:

Though it was Dr. Franklin and Captain Tim Folger, who first turned the Gulf Stream to nautical account, the discovery that there was a Gulf Stream cannot be said to belong to either of them, for its existence was known to Peter Martyr d’Anghiera, and to Sir Humphrey Gilbert, in the 16th century.[180]

An aging Franklin accumulated all his oceanographic findings in Maritime Observations, published by the Philosophical Society’s transactions in 1786.[181] It contained ideas for sea anchors, catamaran hulls, watertight compartments, shipboard lightning rods and a soup bowl designed to stay stable in stormy weather.

Theories and experiments

Franklin was, along with his contemporary Leonhard Euler, the only major scientist who supported Christiaan Huygens’s wave theory of light, which was basically ignored by the rest of the scientific community. In the 18th century, Isaac Newton’s corpuscular theory was held to be true; it took Thomas Young’s well-known slit experiment in 1803 to persuade most scientists to believe Huygens’s theory.[182]

On October 21, 1743, according to the popular myth, a storm moving from the southwest denied Franklin the opportunity of witnessing a lunar eclipse. He was said to have noted that the prevailing winds were actually from the northeast, contrary to what he had expected. In correspondence with his brother, he learned that the same storm had not reached Boston until after the eclipse, despite the fact that Boston is to the northeast of Philadelphia. He deduced that storms do not always travel in the direction of the prevailing wind, a concept that greatly influenced meteorology.[183] After the Icelandic volcanic eruption of Laki in 1783, and the subsequent harsh European winter of 1784, Franklin made observations on the causal nature of these two seemingly separate events. He wrote about them in a lecture series.[184]

Though Franklin is famously associated with kites from his lightning experiments, he has also been noted by many for using kites to pull humans and ships across waterways.[185] George Pocock in the book A Treatise on The Aeropleustic Art, or Navigation in the Air, by means of Kites, or Buoyant Sails[186] noted being inspired by Benjamin Franklin’s traction of his body by kite power across a waterway.

Franklin noted a principle of refrigeration by observing that on a very hot day, he stayed cooler in a wet shirt in a breeze than he did in a dry one. To understand this phenomenon more clearly, he conducted experiments. In 1758 on a warm day in Cambridge, England, he and fellow scientist John Hadley experimented by continually wetting the ball of a mercury thermometer with ether and using bellows to evaporate the ether.[187] With each subsequent evaporation, the thermometer read a lower temperature, eventually reaching 7 °F (−14 °C). Another thermometer showed that the room temperature was constant at 65 °F (18 °C). In his letter Cooling by Evaporation, Franklin noted that, «One may see the possibility of freezing a man to death on a warm summer’s day.»[188]

According to Michael Faraday, Franklin’s experiments on the non-conduction of ice are worth mentioning, although the law of the general effect of liquefaction on electrolytes is not attributed to Franklin.[189] However, as reported in 1836 by Franklin’s great-grandson Prof. Alexander Dallas Bache of the University of Pennsylvania, the law of the effect of heat on the conduction of bodies otherwise non-conductors, for example, glass, could be attributed to Franklin. Franklin wrote, «… A certain quantity of heat will make some bodies good conductors, that will not otherwise conduct …» and again, «… And water, though naturally a good conductor, will not conduct well when frozen into ice.»[190]

While traveling on a ship, Franklin had observed that the wake of a ship was diminished when the cooks scuttled their greasy water. He studied the effects on a large pond in Clapham Common, London. «I fetched out a cruet of oil and dropt a little of it on the water … though not more than a teaspoon full, produced an instant calm over a space of several yards square.» He later used the trick to «calm the waters» by carrying «a little oil in the hollow joint of my cane».[191]

An illustration from Franklin’s paper on «Water-spouts and Whirlwinds»

Decision-making

In a 1772 letter to Joseph Priestley, Franklin laid out the earliest known description of the Pro & Con list,[192] a common decision-making technique, now sometimes called a decisional balance sheet:

… my Way is, to divide half a Sheet of Paper by a Line into two Columns, writing over the one Pro, and over the other Con. Then during three or four Days Consideration I put down under the different Heads short Hints of the different Motives that at different Times occur to me for or against the Measure. When I have thus got them all together in one View, I endeavour to estimate their respective Weights; and where I find two, one on each side, that seem equal, I strike them both out: If I find a Reason pro equal to some two Reasons con, I strike out the three. If I judge some two Reasons con equal to some three Reasons pro, I strike out the five; and thus proceeding I find at length where the Ballance lies; and if after a Day or two of farther Consideration nothing new that is of Importance occurs on either side, I come to a Determination accordingly.[192]

Political, social, and religious views

Like the other advocates of republicanism, Franklin emphasized that the new republic could survive only if the people were virtuous. All his life, he explored the role of civic and personal virtue, as expressed in Poor Richard’s aphorisms. He felt that organized religion was necessary to keep men good to their fellow men, but rarely attended religious services himself.[193] When he met Voltaire in Paris and asked his fellow member of the Enlightenment vanguard to bless his grandson, Voltaire said in English, «God and Liberty», and added, «this is the only appropriate benediction for the grandson of Monsieur Franklin.»[194]

Voltaire blessing Franklin’s grandson, in the name of God and Liberty, by Pedro Américo, 1889–90

Franklin’s parents were both pious Puritans.[195] The family attended the Old South Church, the most liberal Puritan congregation in Boston, where Benjamin Franklin was baptized in 1706.[196] Franklin’s father, a poor chandler, owned a copy of a book, Bonifacius: Essays to Do Good, by the Puritan preacher and family friend Cotton Mather, which Franklin often cited as a key influence on his life. «If I have been», Franklin wrote to Cotton Mather’s son seventy years later, «a useful citizen, the public owes the advantage of it to that book.»[197] His first pen name, Silence Dogood, paid homage both to the book and to a widely known sermon by Mather. The book preached the importance of forming voluntary associations to benefit society. Franklin learned about forming do-good associations from Mather, but his organizational skills made him the most influential force in making voluntarism an enduring part of the American ethos.[198]

Franklin formulated a presentation of his beliefs and published it in 1728.[199] It did not mention many of the Puritan ideas regarding salvation, the divinity of Jesus, or indeed much religious dogma. He classified himself as a deist in his 1771 autobiography,[200] although he still considered himself a Christian.[201] He retained a strong faith in a God as the wellspring of morality and goodness in man, and as a Providential actor in history responsible for American independence.[202]

At a critical impasse during the Constitutional Convention in June 1787, he attempted to introduce the practice of daily common prayer with these words:

… In the beginning of the contest with G. Britain, when we were sensible of danger we had daily prayer in this room for the Divine Protection. Our prayers, Sir, were heard, and they were graciously answered. All of us who were engaged in the struggle must have observed frequent instances of a Superintending providence in our favor. … And have we now forgotten that powerful friend? or do we imagine that we no longer need His assistance. I have lived, Sir, a long time and the longer I live, the more convincing proofs I see of this truth—that God governs in the affairs of men. And if a sparrow cannot fall to the ground without his notice, is it probable that an empire can rise without his aid? We have been assured, Sir, in the sacred writings that «except the Lord build they labor in vain that build it.» I firmly believe this; and I also believe that without his concurring aid we shall succeed in this political building no better than the Builders of Babel: … I therefore beg leave to move—that henceforth prayers imploring the assistance of Heaven, and its blessings on our deliberations, be held in this Assembly every morning before we proceed to business, and that one or more of the Clergy of this City be requested to officiate in that service.[203]

The motion met with resistance and was never brought to a vote.[204]

Franklin was an enthusiastic supporter of the evangelical minister George Whitefield during the First Great Awakening. He did not himself subscribe to Whitefield’s theology, but he admired Whitefield for exhorting people to worship God through good works. He published all of Whitefield’s sermons and journals, thereby earning a lot of money and boosting the Great Awakening.[205]

When he stopped attending church, Franklin wrote in his autobiography:

… Sunday being my studying day, I never was without some religious principles. I never doubted, for instance, the existence of the Deity; that He made the world, and governed it by His providence; that the most acceptable service of God was the doing good to man; that our souls are immortal; and that all crime will be punished, and virtue rewarded, either here or hereafter.[206][207]

Franklin retained a lifelong commitment to the Puritan virtues and political values he had grown up with, and through his civic work and publishing, he succeeded in passing these values into the American culture permanently. He had a «passion for virtue».[208] These Puritan values included his devotion to egalitarianism, education, industry, thrift, honesty, temperance, charity and community spirit.[209]

The classical authors read in the Enlightenment period taught an abstract ideal of republican government based on hierarchical social orders of king, aristocracy and commoners. It was widely believed that English liberties relied on their balance of power, but also hierarchal deference to the privileged class.[210] «Puritanism … and the epidemic evangelism of the mid-eighteenth century, had created challenges to the traditional notions of social stratification»[211] by preaching that the Bible taught all men are equal, that the true value of a man lies in his moral behavior, not his class, and that all men can be saved.[211] Franklin, steeped in Puritanism and an enthusiastic supporter of the evangelical movement, rejected the salvation dogma but embraced the radical notion of egalitarian democracy.[citation needed]

Franklin’s commitment to teach these values was itself something he gained from his Puritan upbringing, with its stress on «inculcating virtue and character in themselves and their communities.»[212] These Puritan values and the desire to pass them on, were one of his quintessentially American characteristics and helped shape the character of the nation. Max Weber considered Franklin’s ethical writings a culmination of the Protestant ethic, which ethic created the social conditions necessary for the birth of capitalism.[213]

One of his notable characteristics was his respect, tolerance and promotion of all churches. Referring to his experience in Philadelphia, he wrote in his autobiography, «new Places of worship were continually wanted, and generally erected by voluntary Contribution, my Mite for such purpose, whatever might be the Sect, was never refused.»[206] «He helped create a new type of nation that would draw strength from its religious pluralism.»[214] The evangelical revivalists who were active mid-century, such as Whitefield, were the greatest advocates of religious freedom, «claiming liberty of conscience to be an ‘inalienable right of every rational creature.'»[215] Whitefield’s supporters in Philadelphia, including Franklin, erected «a large, new hall, that … could provide a pulpit to anyone of any belief.»[216] Franklin’s rejection of dogma and doctrine and his stress on the God of ethics and morality and civic virtue made him the «prophet of tolerance».[214] He composed «A Parable Against Persecution», an apocryphal 51st chapter of Genesis in which God teaches Abraham the duty of tolerance.[217] While he was living in London in 1774, he was present at the birth of British Unitarianism, attending the inaugural session of the Essex Street Chapel, at which Theophilus Lindsey drew together the first avowedly Unitarian congregation in England; this was somewhat politically risky and pushed religious tolerance to new boundaries, as a denial of the doctrine of the Trinity was illegal until the 1813 Act.[218]

Although his parents had intended for him a career in the church,[18] Franklin as a young man adopted the Enlightenment religious belief in deism, that God’s truths can be found entirely through nature and reason,[219] declaring, «I soon became a thorough Deist.»[220] He rejected Christian dogma in a 1725 pamphlet A Dissertation on Liberty and Necessity, Pleasure and Pain,[221] which he later saw as an embarrassment,[222] while simultaneously asserting that God is «all wise, all good, all powerful.»[222] He defended his rejection of religious dogma with these words: «I think opinions should be judged by their influences and effects; and if a man holds none that tend to make him less virtuous or more vicious, it may be concluded that he holds none that are dangerous, which I hope is the case with me.» After the disillusioning experience of seeing the decay in his own moral standards, and those of two friends in London whom he had converted to deism, Franklin turned back to a belief in the importance of organized religion, on the pragmatic grounds that without God and organized churches, man will not be good.[223] Moreover, because of his proposal that prayers be said in the Constitutional Convention of 1787, many have contended that in his later life he became a pious Christian.[224][225]

According to David Morgan,[226] Franklin was a proponent of religion in general. He prayed to «Powerful Goodness» and referred to God as «the infinite». John Adams noted that he was a mirror in which people saw their own religion: «The Catholics thought him almost a Catholic. The Church of England claimed him as one of them. The Presbyterians thought him half a Presbyterian, and the Friends believed him a wet Quaker.» Whatever else Franklin was, concludes Morgan, «he was a true champion of generic religion.» In a letter to Richard Price, Franklin states that he believes religion should support itself without help from the government, claiming, «When a Religion is good, I conceive that it will support itself; and, when it cannot support itself, and God does not take care to support, so that its Professors are oblig’d to call for the help of the Civil Power, it is a sign, I apprehend, of its being a bad one.»[227]

In 1790, just about a month before he died, Franklin wrote a letter to Ezra Stiles, president of Yale University, who had asked him his views on religion:

As to Jesus of Nazareth, my Opinion of whom you particularly desire, I think the System of Morals and his Religion, as he left them to us, the best the world ever saw or is likely to see; but I apprehend it has received various corrupt changes, and I have, with most of the present Dissenters in England, some Doubts as to his divinity; tho’ it is a question I do not dogmatize upon, having never studied it, and I think it needless to busy myself with it now, when I expect soon an Opportunity of knowing the Truth with less Trouble. I see no harm, however, in its being believed, if that belief has the good consequence, as it probably has, of making his doctrines more respected and better observed; especially as I do not perceive that the Supreme takes it amiss, by distinguishing the unbelievers in his government of the world with any particular marks of his displeasure.[20]

On July 4, 1776, Congress appointed a three-member committee composed of Franklin, Jefferson, and Adams to design the Great Seal of the United States. Franklin’s proposal (which was not adopted) featured the motto: «Rebellion to Tyrants is Obedience to God» and a scene from the Book of Exodus, with Moses, the Israelites, the pillar of fire, and George III depicted as pharaoh. The design that was produced was not acted upon by Congress, and the Great Seal’s design was not finalized until a third committee was appointed in 1782.[228][229]

Franklin strongly supported the right to freedom of speech:

In those wretched countries where a man cannot call his tongue his own, he can scarce call anything his own. Whoever would overthrow the liberty of a nation must begin by subduing the freeness of speech …

Without freedom of thought there can be no such thing as wisdom, and no such thing as public liberty without freedom of speech, which is the right of every man …

Thirteen Virtues

Franklin sought to cultivate his character by a plan of 13 virtues, which he developed at age 20 (in 1726) and continued to practice in some form for the rest of his life. His autobiography lists his 13 virtues as:[231]

- Temperance. Eat not to dullness; drink not to elevation.»

- Silence. Speak not but what may benefit others or yourself; avoid trifling conversation.»

- Order. Let all your things have their places; let each part of your business have its time.

- Resolution. Resolve to perform what you ought; perform without fail what you resolve.

- Frugality. Make no expense but to do good to others or yourself; i.e., waste nothing.

- Industry. Lose no time; be always employ’d in something useful; cut off all unnecessary actions.

- Sincerity. Use no hurtful deceit; think innocently and justly, and, if you speak, speak accordingly.

- Justice. Wrong none by doing injuries, or omitting the benefits that are your duty.

- Moderation. Avoid extremes; forbear resenting injuries so much as you think they deserve.

- Cleanliness. Tolerate no uncleanliness in body, clothes, or habitation.

- Tranquility. Be not disturbed at trifles, or at accidents common or unavoidable.

- Chastity. Rarely use venery but for health or offspring, never to dullness, weakness, or the injury of your own or another’s peace or reputation.

- Humility. Imitate Jesus and Socrates.