Can you start a sentence with but? English teachers love to tell us it’s against the rules. But there is nothing wrong with starting a sentence with but.

As you grow as a writer, you learn that many of the rules you were taught in school aren’t really rules at all. Can you start a sentence with but? Your third-grade teacher probably told you this was absolutely verboten. However, this is an example of a common rule that is misleading. There is nothing wrong with starting a sentence with but or any other coordinating conjunction. In fact, authorities as lofty as The Elements of Style, The Chicago Style Manual, and William Shakespeare all begin sentences with the word “but.” In the case of the former two examples for analyzing a sentence, they also overtly say that it is permissible.

Contents

- Why It Is OK to Start a Sentence with But?

- What Are Coordinating Conjunctions?

- What Are Independent Clauses?

- How Do You Avoid Sentence Fragments?

- Can But Go at the Beginning of a Sentence in Good Writing?

- Is It OK in Business Writing?

- Where Did the Rule Against Starting a Sentence with But Come From?

- The Final Word on Can You Start a Sentence with But

- FAQ About Starting a Sentence with But

- Author

| IMAGE | PRODUCT | |

|---|---|---|

|

Best Sentence Checker

|

Grammarly

|

Claim My Discount → |

|

Best Alternative

|

ProWritingAid

|

Claim My Discount → |

Why It Is OK to Start a Sentence with But?

“But” is conjunction. According to sources including Merriam-Webster, conjunction is used to join words, phrases, clauses, and sentences. Because of this, it is perfectly proper to use “but” to begin a sentence that continues an idea expressed in the previous one.

What Are Coordinating Conjunctions?

We use coordinating conjunctions to connect words and phrases together. The seven coordinating conjunctions in the English language are:

- And

- But

- For

- Nor

- Or

- So

- Yet

It is perfectly allowable to start a sentence with any of these, as long as you are connecting two independent clauses.

What Are Independent Clauses?

An independent clause is one that forms a complete sentence on its own. Examples of independent clauses that are joined by coordinating conjunctions include:

- I got to the station early. But I still missed my train.

- She won’t eat at Italian restaurants. Nor will she try sushi.

- We could go to Paris. Or we could take a flight to Madrid.

How Do You Avoid Sentence Fragments?

As long as the sentence you started with “but” includes both a noun and a verb, the chances that you’ve created a fragment are very low. A sentence fragment lacks one or the other (usually the verb). As long as the first phrase ends in a full stop and the second phrase uses “but” in a logical way, you can’t go wrong.

Examples include:

- I got the promotion. But I still won’t make as much as I need.

- He arrived with seven bags of groceries. But he still forgot the bread.

There are few logical statements in sentences of those forms that would take the form of fragments. If you were to write “He arrived with seven bags of groceries. But the bread.” the reader would be excused for wondering “but the bread what?”

Can But Go at the Beginning of a Sentence in Good Writing?

Yes, absolutely. Good writing, in fact, is made up of sentences that vary in length and word use. Bad writing often suffers from an excess of uniformity rather than a sprinkling of grammar that, although correct, would not be accepted in a beginning language class.

Is It OK in Business Writing?

It’s accepted that business writing is more formal than some other forms. Because of this, there is a reluctance to use grammar that might be seen as overly casual.

However, in actual practice, the choice comes down to the setting and the tone. If other people in your company seem to hew to more stiff and formal language, it might be good to do so, as well. But if they tend to write with less formality, you are free to do so, too.

Where Did the Rule Against Starting a Sentence with But Come From?

According to linguist David Crystal, the rule started with schoolteachers in the 19th century. Many noticed young students habitually starting sentences with conjunctions and attempted to stop this in the interest of creating themes and essays with standalone, independent thoughts and clauses.

But instead of encouraging students to limit the use of these sentence starters, over time, they fell into a habit of banning the words altogether. Because of this, generations of children were taught never to start a sentence with conjunction when no such English grammar rule exists.

The Final Word on Can You Start a Sentence with But

Yes, you absolutely can start a sentence with but. But you need to make sure that the following sentence is not a fragment.

When it comes to using it in a business setting, that is a question of style rather than grammar. Follow the lead of the people in your office and your industry. And if there’s a style guide, that’s even better.

FAQ About Starting a Sentence with But

When can you start a sentence with but?

Any time you are joining a sentence with the one that proceeds it.

Are there times it’s wrong to start a sentence with but?

It’s wrong if your sentence is not a complete sentence. If it is a dependent clause, you should use a piece of punctuation other than a period.

Is it OK to use but at the start of a sentence according to AP Style or Chicago Manual of Style?

Both allow you to use but at the beginning of a sentence.

Join over 15,000 writers today

Get a FREE book of writing prompts and learn how to make more money from your writing.

Pin

Pin

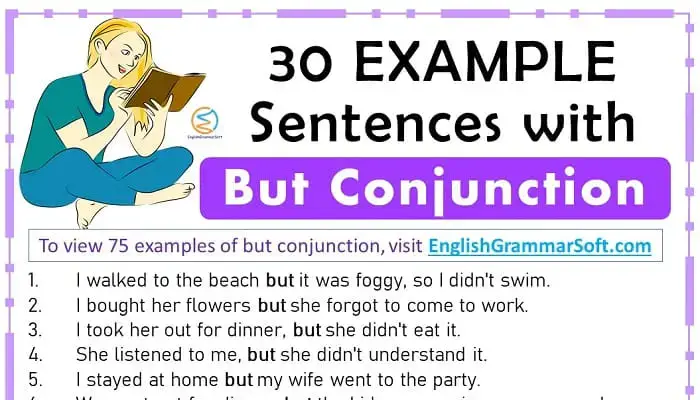

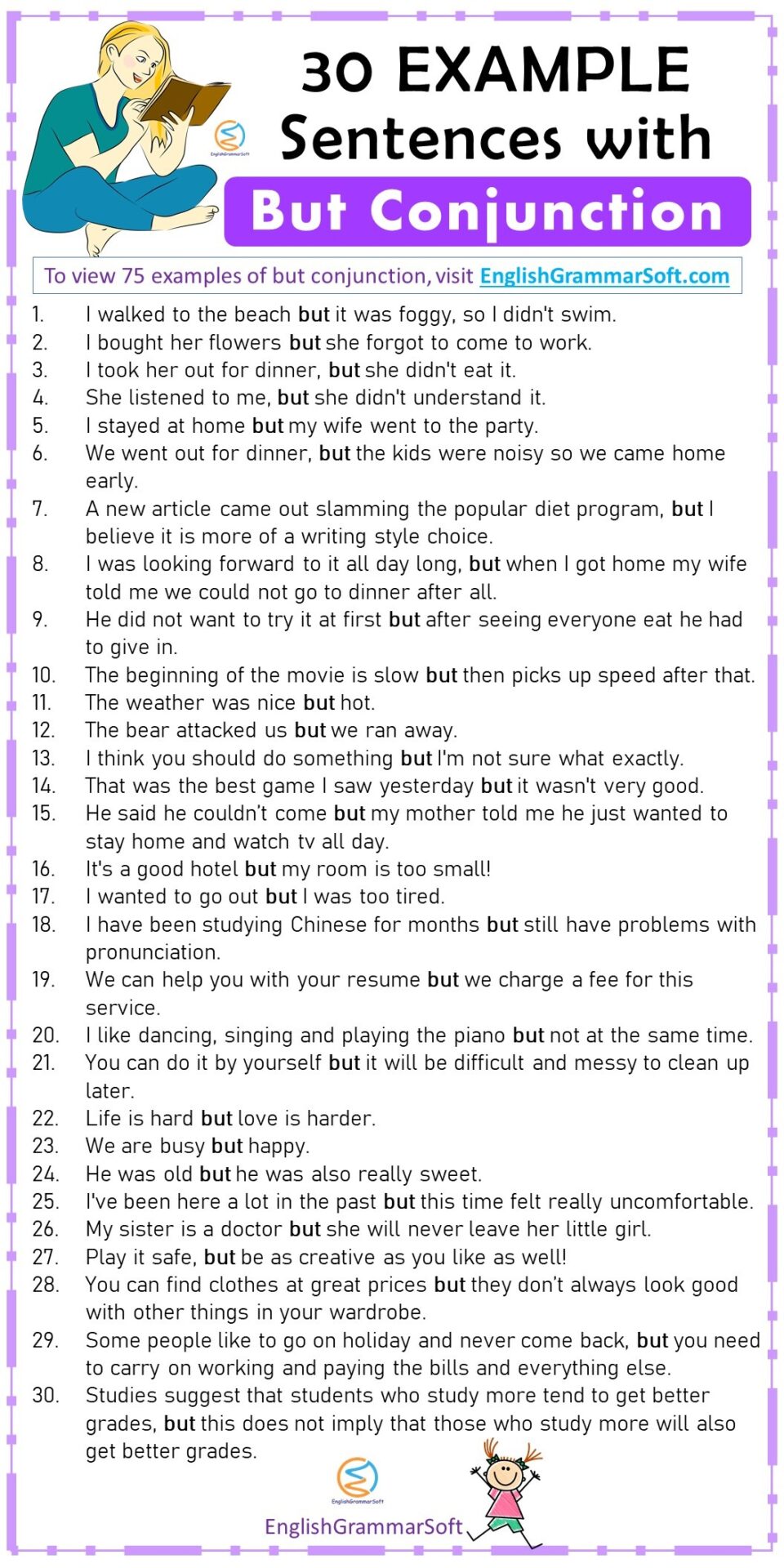

In English, conjunctions are a part of speech that connect words and group words/clauses together. For example: “My phone got wet but it still works.”

The word but is coordinating conjunction and one of the most commonly used conjunctions in the English language. Here are 75 example sentences with but conjunction.

Read also: Types of Conjunctions with Examples

- I walked to the beach but it was foggy, so I didn’t swim.

- I bought her flowers but she forgot to come to work.

- I took her out for dinner, but she didn’t eat it.

- She listened to me, but she didn’t understand it.

- I stayed at home but my wife went to the party.

- We went out for dinner, but the kids were noisy so we came home early.

- A new article came out slamming the popular diet program, but I believe it is more of a writing style choice.

- I was looking forward to it all day long, but when I got home my wife told me we could not go to dinner after all.

- He did not want to try it at first but after seeing everyone eat he had to give in.

- The beginning of the movie is slow but then picks up speed after that.

- The weather was nice but hot.

- The bear attacked us but we ran away.

- I think you should do something but I’m not sure what exactly.

- That was the best game I saw yesterday but it wasn’t very good.

- He said he couldn’t come but my mother told me he just wanted to stay home and watch tv all day.

- It’s a good hotel but my room is too small!

- I wanted to go out but I was too tired.

- I have been studying Chinese for months but still have problems with pronunciation.

- We can help you with your resume but we charge a fee for this service.

- I like dancing, singing and playing the piano but not at the same time.

- You can do it by yourself but it will be difficult and messy to clean up later.

- Life is hard but love is harder.

- We are busy but happy.

- He was old but he was also really sweet.

- The defendant was charged with assault and his lawyer claimed he acted in self defence but he was found guilty.

- ECT is dangerous but the side effects can be worse than the disease.

- In this case I don’t think that it is acceptable that a man without a criminal record isn’t allowed to work as a taxi driver because of this but I think that the law needs to be changed to make it more logical.

- I’ve been here a lot in the past but this time felt really uncomfortable.

- My sister is a doctor but she will never leave her little girl.

- Play it safe, but be as creative as you like as well!

- You can find clothes at great prices but they don’t always look good with other things in your wardrobe.

- Some people like to go on holiday and never come back, but you need to carry on working and paying the bills and everything else.

- Studies suggest that students who study more tend to get better grades, but this does not imply that those who study more will also get better grades.

- You can’t be fearless, but it is good to be brave, which is the opposite of being scared.

- He has a big mouth, but everything he says cannot be true.

- It was better than I thought but I was still disappointed.

- They are good at marketing but not good at production.

- What you see isn’t always what you get but it can be!

- Never try to look for perfection in others, because you will find flaws in everyone but yourself.

- I love my new dress but it’s too expensive.

- I don’t think he likes me, but I will talk with him.

- He is a good boy but he is lazy.

- The book is good but I don’t like the end.

- I like football, but not basketball.

- She was enjoying her meal, but it took too long to arrive.

- I didn’t buy it, but will look for it online.

- You can go home now, but you must be back by midnight.

- She is poor but she is happy.

- He looks smart but he is really bad.

- Tom loves his country but he doesn’t like politics.

- The train was early but I could not catch it.

- They didn’t like it but they bought it anyway.

- She worked hard for the exam but she failed anyway.

- I liked that restaurant, but it was crowded.

- I didn’t like that restaurant, but I did like the desserts.

- I’m not hungry, but he is very hungry .

- I didn’t go to the movies last night, but John did.

- You can go to school today, but you have to work hard.

- She didn’t want to go out tonight, but she doesn’t need to get up early tomorrow.

- The dress was expensive but it had to be replaced.

- The computer is cheap but good value for money.

- It was cheap but it had to be replaced at once.

- The shoes are comfortable but they need new heels.

- I like the furniture but I am not sure if I should keep them.

- The printer is complicated but so efficient.

- The students are studying hard but they are not doing well.

- Jonathan is smart but shy.

- I went with Lee but he didn’t come with me.

- I will go with him but where will you go?

- I am happy because my family came on time, but my friend is late.

- Some university students but not all like to socialize with other students.

- Jeremy Clarkson is married but not happy.

- All of our staff are paid fairly but it’s still difficult to survive on your wage.

- Mark Zuckerberg is an American billionaire but was raised in White Plains, New York.

- The average person should eat meat but I am a vegetarian.

Read also

- Conjunction Sentences (50 Examples)

- Sentences with Although Conjunction (87 Examples)

- No Sooner Than Sentences (31 Examples)

- Examples with Neither Nor (50 Sentences)

- Sentences With Semicolons (;) 50 Examples

- Sentences with Either – or

- 50 Example Sentences with However

- Do Does Did Sentences (50 Examples)

- Has Have Had use in sentences | 50 Examples

- Was Were Sentences | 50 Examples

- There is – There are Sentences | 50 Examples

- Is am are sentences in English (50 Examples)

Today, I am here to set you free from one of the shibboleths of grammar. You will be liberated! I certainly was. At school, we were taught you should never, ever, under any circumstances start a sentence with a conjunction. That rules out starting sentences with either “and” or “but” when writing. I faithfully learned the rule. I became positively angry when I read books in which otherwise excellent writers seemed to make this faux pas. How could they be so sloppy?

One day, I decided to settle the matter once and for all. I would find an authoritative reference to back up what I had learned, and I would send it to someone who had just argued you can start a sentence with “but.”

Being Wrong Can Make You Happy

Once I started to check, I quickly realized I was going to be proved wrong. People, including some of the greatest writers of all time, have been starting sentences with “and” and “but” for hundreds of years. Of course, there are style guides that discourage it, but it’s perfectly acceptable to begin a sentence with “but” when writing. I was thrilled! That very day, I started peppering my writing with sentences starting with conjunctions. But one shouldn’t go overboard! See what I did there? Hah!

Using any stylistic quirk too frequently spoils your writing. By all means, start sentences with “but” from time to time, but remember that “but” also belongs after a comma. I did it again, didn’t I?

When Should You Consider Starting a Sentence With “But”?

“Contrary to what your high school English teacher told you, there’s no reason not to begin a sentence with but or and; in fact, these words often make a sentence more forceful and graceful. They are almost always better than beginning with however or additionally.” (Professor Jack Lynch, Associate Professor of English, Rutgers University, New Jersey)

Thank you, professor! I’ll admit to using “however,” but being lazy, I really do prefer the word “but” to begin a sentence when given a choice. “Additionally” is just awful, and I flinch every time I start a sentence with it. It seems so pompous!

The professor also confirms starting with the conjunction can make your writing more forceful. Remember, you don’t always want to be forceful. Sometimes sentence flow is more appropriate. But a choppy “but” at the start of a sentence certainly does seem to add emphasis when that’s what you’re looking for.

People Are Going to Argue This With You

Just as I once was a firm believer in the “never start a sentence with and or but” non-rule, you’ll come across enslaved souls who have been taught the very same non-rule. Where can they turn for confirmation and comfort? The Bible is always a good place. Refer them to Genesis Chapter 1 for sentences starting with “and.”

For a sentence starting with “but,” you may have to read a little further – all the way to Genesis 8:1: “But God remembered Noah and all the wild animals and the livestock that were with him in the ark, and he sent a wind over the earth, and the waters receded.”

Looking around online, I see some arguing that using the Bible as a work of English literature is pushing the envelope. I beg to differ, but perhaps as the world’s greatest bestseller, it’s a bit too commercial for them. Let’s take them to the real authority: the notoriously stuffy and pedantic, Fowler’s Modern English Usage. It’s seen as the authoritative book on English Grammar, and if they won’t believe it, they’re never going to believe anyone.

If they’re trying to find a comeback, you can always help them out. But they won’t be impressed with the reference you give them because I’m ready to bet you anything they’ve never have heard of Quackenbos!

“A sentence should not commence with the conjunctions and, for, but, or however…. ” (George Payn Quackenbos, An Advanced Course of Composition and Rhetoric, 1854)

Let’s sum up that argument, ladies and gentlemen of the jury. We have the Bible, a host of brilliant writers, and Fowler’s Modern English Usage vs… Quackenbos. I’ll see your Quackenbos and I’ll raise you an Albert Einstein. Oops, we’ve gone from law to poker. Please pardon the mixed metaphors. Of course, Shakespeare also occasionally mixed metaphors, but we’ll go into that another time, shall we?

Why Were Students Taught This Non-Rule Rule?

Why were we taught this non-rule rule about not starting sentences with conjunctions? Several authorities seem to think it was done to prevent school kids from writing as they often talk:

“I went to my friend’s house yesterday. And we decided to go to the mall. And while we were there we saw a whole bunch of our friends. And they were just hanging out like we were. And because we didn’t have any money that was all we could do, really.”

Or

“But then John said he’d had a birthday, and we could all go for ice creams. But when we got to the ice-cream parlor, he found that he had left his wallet at home. But that didn’t stop us from having a good time together while teasing John that he owed us an ice-cream.”

You have to admit, that’s a bit much. So to close, we quote Oscar Wilde, “Everything in moderation, including moderation.”

|

|

||||||||||||||

|

Home > Vocabulary Lessons > |

||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||

|

Copyright © 2015 ENGLISHCOLLOCATION.COM TERMS OF USE | CONTACT | PRIVACY POLICY |

-

#1

hey there,

Is there actually a rule about using But at the beginning of sentences. I remember being told in school that it should never be done ( like Basoonery’s point about the Oxford Comma) but of course see it everywhere. Is there an actual grammatical rule or is it just a question of style?

-

#2

I’m pretty sure it’s a rule that «But» cannot be used at the beginning of a sentence, but as you said, many people disregard it.

-

#3

Conjunctions at the start of sentences are to be used with caution.

As a general rule of thumb, beginners in English should avoid them.

In practice, you will find that many, if not most, experienced English writers will start sentences with conjunctions.

If these forums were to ban the use of conjunctions at the start of sentences, a very large proportion of my posts would have to go.

In other words, there is a guideline for beginners that cautions against starting a sentence with but. It is not a grammatical rule.

If you studied science, you may remember being taught at first that an atom was the smallest indivisible particle of matter. Then when you learned more you discovered electrons, protons and neutrons.

Enough knowledge for you to survive a few years.

Then along came lots more sub-atomic particles and wave theories and cats in boxes.

English is rather like that. There are models of usage that are appropriate for each level of development. Then you discover that the model was a partial model and you learn something new — for example that is is entirely normal in English to begin a sentence with a conjunction.

-

#4

yeah that makes sense. As far as I remember it was just in primary school that the teacher would insist on such models. Ta!

-

#5

The «rule» had a purpose.

Beginning writers often keep on going without considering the structure of their sentences and introduce new concepts within sentences but never think of the risks of skating without the proper protective equipment and insist on eating their peas with honey on their knives instead of carefully polishing their glasses and making sure they use the correct spoon for each course.

Then they break up the run-on sentences with punctuation. The result is fractured sense and dreadful sentences. And many of the sentences begin with conjunctions simply because the word before the conjunction concluded what they thought was a sentence-worth. But do not despair.

When you have mastered the art of using capital letters at the beginning of sentences, you too might be considered fluent enough to begin a sentence with But

-

#6

Cheeky! Both my punctuation and spelling tend to be pretty desperate alright but that’s why I’m here

-

#7

Mary Therés,

Stay awhile and you’ll be able to mix metaphors just as well as Panjandrum….skating over to the buffet table to get some honey and peas on my knife.

However much you may have been told of rules and their supposed sanctity, many of them are nothing but stylistic conventions, some very useful, as Panj has pointed out, and others just hand-me-downs that are ragged around the knees.

-

#8

I have an English-major friend that insist it’s always, 100% wrong to use ‘and’ or ‘but’ at the beginning of sentences. I’ve wrangled with her for YEARS!

I think everything that needs explaining has been explained; I just wanted to add my two cents in.

-

#9

I think everything that needs explaining has been explained; I just wanted to add my two cents in.

![Stick Out Tongue :p :p]()

And that, as they say, is the end of that.

-

#10

I have an English-major friend that insist it’s always, 100% wrong to use ‘and’ or ‘but’ at the beginning of sentences. I’ve wrangled with her for YEARS!

I think everything that needs explaining has been explained; I just wanted to add my two cents in.

Tell your friend, ‘Rules are for the obedience of fools and the guidance of wise men.’

(Bear in mind though that this quote is attributed to Douglas Bader who broke the rules on low-level aerobatics and ending up having both legs amputated… )

-

#11

But don’t forget that he also become a very good golfer afterwards, married the girl he wanted, had a nice career in the RAF, crashed another airplane and lived happily ever after.

Pass the peas and honey, please, Winklepicker.

-

#12

Pass the peas and honey, please, Winklepicker.

I’ve done it all my life, Cuchu.

-

#13

For your continued edification, just google «History of English,» or «English grammar.»

-

#14

As we are being very precise and specific in our advice, why not just google «Which came first—the language or the grammarians?»

-

#15

I also had it drilled into my head since grammar school that it was definitely a «no no» to use either and or but at the beginning of a (written) sentence. Although I might use either or both in emails or personal correspondence, I try to avoid it on the English only forum.

But I’m glad that the subject came up so that members who are doing writing assignments for class will know that conjunctions at the beginning of sentences probably won’t be acceptable to their English professors.

-

#16

In the last but one, him would no doubt have been defended by the writer, since the full form would be he whom, as an attraction to the vanished whom.

But such attraction is not right

; if he alone is felt to be uncomfortable, whom should not be omitted; or, in this exalted context, it might be he that.

emphasis added.

Take a guess as to the author of the quoted material.

It was one H.W. Fowler!

http://www.bartleby.com/116/201.html

-

#17

I also had it drilled into my head since grammar school that it was definitely a «no no» to use either and or but at the beginning of a (written) sentence. Although I might use either or both in emails or personal correspondence, I try to avoid it on the English only forum.

But I’m glad that the subject came up so that members who are doing writing assignments for class will know that conjunctions at the beginning of sentences probably won’t be acceptable to their English professors.

A Christmas Carol

Do a search for «But». Make sure you mark «match case». I believer there are nearly ten sentences starting with but, and that’s only considering the narrative.

The Picture of Dorian Gray

At least three «but’s» in the first chapter. (Click on chapter one.)

Gullivers-Travels

Nice in the first chapter.

I wonder what these gentlemen were taught in school? Surely such «poor» writing could not have been acceptable to their English teachers.

Gaer

-

#18

But shouldn’t be use as the start of the sentence; it makes a fragment. But denotes a subordinate clause and needs a main clause to explain its meaning.

However, it is possible to use but that way as a style method; it is a way to put emphasis on a subject.

-

#19

But shouldn’t be use as the start of the sentence; it makes a fragment. But denotes a subordinate clause and needs a main clause to explain its meaning.

However, it is possible to use but that way as a style method; it is a way to put emphasis on a subject.

Okay, so what exactly is the difference between «but» and «although» or even «yet» or «nevertheless?» (Okay, sometimes there is a difference.) Pan is essentially right about why the rule is there, but I’ll agree that it’s perfectly acceptable to use «but» once you know the language (and the difference). The difference between the above is sometimes an artificial grammatical distinction and «but» is at times the most direct and best word to use. Plain talk, as opposed to high falutin’. (Next thread?)

That said, I’ll tell you a story. A couple of years ago I took the GRE’s. I got a perfect score on the verbal. ( I guessed at least once and got lucky—though I don’t consider it luck so much as good logic.) They had just instituted a written element. Essays. (Now, [But. But «but» wouldn’t work as well as «now» here. Close, but no cigar] I could write that just as well by saying: They had just introduced a written element: essays.) I wrote elegant, nuanced arguments, and got a sub-par score. I started a sentence or two with «but.» Might have had a sentence fragment or two in there for effect.

I suspect I received a poor score due to grammar robots.

That’s life.

Can’t deny it.

Lack of judgement on my part.

Barnaby

-

#20

hi

I hate to see » But» at the start of a sentence and tend to use «however» instead. I am still dogged by the very fierce English Teacher I had for my «O» levels at school and every time I write «But» I can hear her terrifying tones.( She wouldn’t let us use a knife like a pen either, so that is another of my pet hates) Oh the baggage we pick up as children!!!

-

#21

Send that fierce English Teacher a pen, some honey and peas, and a copy of Fowler’s

Modern English Usage

, together with instructions to find every sentence Henry Fowler began with but.

There is one example a few posts above this one. Her discomfort should help attone for that she has caused you.

-

#22

But shouldn’t be use as the start of the sentence; it makes a fragment. But denotes a subordinate clause and needs a main clause to explain its meaning.

However, it is possible to use but that way as a style method; it is a way to put emphasis on a subject.

You have had rules and pseudo-rules drilled into you. But there is hope! You seem to at least accept that there are stylistic grounds on which to base the use of but at the start of a sentence. It doesn’t necessarily make a fragment.

-

#23

hi

I hate to see » But» at the start of a sentence and tend to use «however» instead. I am still dogged by the very fierce English Teacher I had for my «O» levels at school and every time I write «But» I can hear her terrifying tones.( She wouldn’t let us use a knife like a pen either, so that is another of my pet hates) Oh the baggage we pick up as children!!!

Have you look at the links I posted? I wonder if anyone has.

Are you saying that you hate to see «but» at the beginning of a sentence by Dickens? Or by Oscar Wilde?

And doesn’t that make you wonder if you have ever noticed what is really used by great authors?

The fact is that we are often so brain-washed by pedantic nit-wits that it blinds us to what is actually used by people who are masters of the English language.

Gaer

-

#24

The thing is, gaer, that well used Buts are completely transparent.

Carelessly used Buts stick out like sore thumbs.

-

#25

Macbeth:

But I am faint, my gashes cry for help.

But screw your courage to the sticking-place,

But wherefore could not I pronounce ‘Amen’?

But let the frame of things disjoint, both the

worlds suffer,

What a pity. If only Shakespeare had had proper instruction, he might have been a good writer.

Gaer

-

#26

The thing is, gaer, that well used Buts are completely transparent.

Carelessly used Buts stick out like sore thumbs.

You have a good point. Apparently all the authors I mentioned in previous links were so subtle about their «rule-breaking» that few people have «caught» them

breaking

the «rules».

Gaer

-

#27

Okay, so what exactly is the difference between «but» and «although» or even «yet» or «nevertheless?» (Okay, sometimes there is a difference.) Pan is essentially right about why the rule is there, but I’ll agree that it’s perfectly acceptable to use «but» once you know the language (and the difference). The difference between the above is sometimes an artificial grammatical distinction and «but» is at times the most direct and best word to use. Plain talk, as opposed to high falutin’. (Next thread?)

That said, I’ll tell you a story. A couple of years ago I took the GRE’s. I got a perfect score on the verbal. ( I guessed at least once and got lucky—though I don’t consider it luck so much as good logic.) They had just instituted a written element. Essays. (Now, [But. But «but» wouldn’t work as well as «now» here. Close, but no cigar] I could write that just as well by saying: They had just introduced a written element: essays.) I wrote elegant, nuanced arguments, and got a sub-par score. I started a sentence or two with «but.» Might have had a sentence fragment or two in there for effect.

I suspect I received a poor score due to grammar robots.

That’s life.

Can’t deny it.

Lack of judgement on my part.Barnaby

1. It is important to master the language; however, it is not the only element one needs to use BUT as the beginning of the sentence. The understanding of the meaning behind the sentence and the reason for using it is equally important. Whenever I use BUT as the beginning of a sentence for school, even though the sentiment may be right, it is always rejected with the reason of being a FRAGMENT. It is better to be that way I think. This is so that when one is developing one’s style, it can be based on the correct grammar.

2. But, yet, although and nevertheless maybe similar meaning-wise sometimes; however, the uses in a sentence are different. But, yet and although are conjunctions. But and yet are used to denote a turning point in a sentence. Thus, I think it makes more sense to be used after the main clause, separated by a comma. Although denotes an adverb clause and is commonly used in the reversed position, where the subordinate clause goes first, followed by a comma and the main clause. However, when although is after the main clause, the comma is not used. Nevertheless is a conjunctive adverb. It has be to separated from the main clause by a semicolon or a period.

3. I don’t understand why you quoted me when your posting is talking about Panj’s explanation. Your posting also mentioned your GRE story, but I do not understand what you are trying to convey. Moreover, I suspect a underlying sarcasm.

4. I would rephrase the sentence for the newly implemented essay. Although they had just instituted a written element, I still got a perfect score on the verbal.

-

#28

You have had rules and pseudo-rules drilled into you. But there is hope! You seem to at least accept that there are stylistic grounds on which to base the use of but at the start of a sentence. It doesn’t necessarily make a fragment.

I am just stating the rule.

There is no more to it.

I accept fully the stylistic component of the language.

I use but fragments way too much.

But I don’t know.

Maybe I am wrong.

But wait, it is good to use but to express one’s sentiment in different ways.

I like to give sudden changes in my writings to catch the reader.

But not everyone agrees with me.

-

#29

I am just stating the rule.

No. You are stating «a» rule.

Yes, there is.

I accept fully the stylistic component of

thelanguage.

If you are talking about «English», then it should be «the English language». If you mean «language» in general, then there is no need for an article there.

I use

but fragments«but fagments» way too much.

But I don’t know.

Maybe I am wrong.

But wait, it is good to use

but«but» to express one’s sentiment in different ways.

I like to

givemake sudden changes in my

writingswriting to catch the reader.

But not everyone agrees with me.

What is your point?

Anyone can write several short sentences.

I can too.

It’s highly unusual.

Normally it doesn’t work.

Not very well.

You do not need to use «but».

The monotony is boring without that little word.

Gaer

-

#30

No. You are stating «a» rule.

I am state the rule for but.

No. There isn’t more to my stating the rule.

If you are talking about «English», then it should be «the English language». If you mean «language» in general, then there is no need for an article there.

What forum are we in here?

What is your point?

Anyone can write several short sentences.

I can too.

It’s highly unusual.

Normally it doesn’t work.

Not very well.

You do not need to use «but».

The monotony is boring without that little word.Gaer

I am not talking to you nor am I replying to your postings in that posting.

Short sentences are effective in conveying brief ideas.

It is not highly unusual.

Even your short sentences give complete meaning and clearly state your point view.

I use but fragments way too much is another use of but. Being an experienced English speaker you should know that.

I like to give sudden changes [to my stories] in my writings (as in all the things I have written).

These are all legitimate uses.

-

#31

I think the progress of this thread demonstrates with exquisite precision the way in which sentences beginning with conjunctions can be a transparent and elegant part of an intelligent discourse.

And that the guidelines suggesting avoidance of this practice are well-advised.

-

#33

It’s fine when but means however and and means furthermore.

-

#34

Welcome to the forum, Rover.

Do you mean all the But sentences so far in this thread are fine except possibly «But of course»?

-

#35

«But denotes a subordinate clause and needs a main clause to explain its meaning.»

Not (always) so, I’m afraid. «But,» like «and,» is often a coordinating conjunction, joining two fully fledged main clauses. E.g., «Prescriptive grammarians are found in front of many classrooms, but most of them are egregiously wrong.» If you substitute a period for the «but,» you have two perfectly complete sentences.

See http://www.chompchomp.com/terms/coordinatingconjunction.htm

-

#36

So is the original question now resolved????

-

#37

Yes, it is.

Yes, there

is

a rule (everyone is free to ignore rules).

And/But yes, it

is

a question of style (as demonstrated by Shakespeare, et al.)

-

#38

My feeling is that academics are becoming more and more open to the idea that one can start a sentence with the word «but». But this doesn’t mean that everyone thinks it’s correct.

Is there any reasonable way one can defend beginning a sentence with «but» to one who thinks it’s unequivocally «incorrect»?

-

#39

I do it at times to break up the length of my sentences. Is that bad?

-

#40

I think it’s good, especially when it cuts unruly sentences down.

-

#41

Point out that they haven’t the slightest idea what they’re talking about. Sentence-initial ‘but’ always has been Standard English — it would be helpful here to have a list of uses of it by Dickens, Jane Austen, Johnson, and so on, but I haven’t got one to hand. Instead, I can look up Fowler’s Modern English Usage under the word but, where he discusses a number of points of grammar about the word at great length, but none of them is about its being in initial position. He isn’t even aware of this nonsense to dismiss it. But in the course of his prescriptive grammar advice he writes at one point, ‘But just as I shouldn’t wonder if he didn’t fall in is often heard’; and a little later he offers ‘But Mary decided‘ as a rewriting of a sentence with the word internally. The fake rule against initial position wasn’t even on the radar in 1930.

Don’t give any leeway at all to the ignoramuses who trot out this garbage. Don’t say the rule is changing, or has relaxed. There never was such a rule.

-

#42

Bravo to entangleddebunker of non-rules. We have discussed this one in a number of prior threads. There are some ignorant pedants abroad in the land (and probably quite a few more at sea) who try to impose their groundless stylistic preferences as «rules».

This particular «rule» is pure hokum.

The Fowler brothers ignored the matter of but at the start of a sentence because there was nothing to discuss.

More recently, it has received some well-deserved attention from Bryan Garner, in

A Dictionary of Modern American Usage.

but. A. Beginning Sentences with. It is a gross canard that beginning a sentence with but is stylistically slipshod. In fact, doing so is highly desirable in any number of contexts, and many stylebooks that discuss the question quite correctly say that but is better than however at the beginning of a sentence.

Garner goes on to quote seven such stylebooks. Here is one of the passages he quotes:

«Of the many myths concerning ‘correct’ English, one of the most persistent is the belief that it is somehow improper to begin a sentence with [and, but, for, or, or not]. The construction is, of course, widely used today and has been widely used for generations, for the very good reason that it is an effective means of achieving coherence between sentences and between larger units of discourse, such as paragraphs.» R.W. Pence & D. W. Emery, A grammar of Present-Day English

Last edited: Jan 20, 2010

I don’t buy into the rule that says you should never begin a sentence with the word ‘but’. If the preceding clause is complex, starting a fresh sentence often increases readability. That said, there are principles you should remember when using ‘however’ as an alternative.

Picture by Frank Micelotta/Getty Images

Mind Your Language’s oracle on these matters, the Macquarie Dictionary, offers useful advice on both these points. Here it is on ‘but’ at the start of sentences:

Some writers object to sentences beginning with but on the grounds that it is a conjunction which should link clauses within a sentence and should not appear to link a new sentence with the previous one. In fact many writers do use but at the beginning of a sentence and there is no reason to object to the practice provided that it is not overdone.

Writers who don’t favour using ‘but’ in this way often turn to ‘however’ as an alternative. That can be a useful strategy, and a way of introducing variety. However, there are pitfalls here too, as the Macquarie points out:

It is now common to begin a sentence with However, but it should be noted that a comma after it may be useful in distinguishing however meaninging ‘nevertheless’ from however meaning ‘in whatever way’.

You can see that clearly with these sentence beginnings:

However, the writer chose a different approach . . .

However the writer chose a different approach . . .

The first conveys the sense “despite what we have discussed previously, the writer chose a different approach”. The second conveys the sense “We don’t know how the writer chose a different approach”. Adding the comma after ‘however’ makes that distinction much clearer, even without knowing how the sentences end.

Lifehacker’s Mind Your Language column offers bossy advice on improving your writing.

More From Lifehacker Australia

About the Author

There is nothing inherently wrong with beginning a sentence with any conjunction, including but. Some stylists have deprecated it, and some English teachers still enforce it; but it has never been anything more than a house rule. It has been continually ‘violated’ by writers—including many of the Best Writers—in every register and every age of English literature.

I’ve never looked to see where and when this “rule” arose, but the history of similar ‘superstitions’ (the characterization is Fowler’s) suggest that it surfaced in the 18th century as a perfectly reasonable recommendation to use the device sparingly, and hardened into a doctrine among 19th century schoolmasters and schoolmarms.(see below)

It appears that educators use this “rule” to stamp out two common tendencies among young writers: 1) sustaining the flow of narrative and exposition by beginning virtually every sentence with and or but or so, and 2) making this a license to isolate sentence fragments as full sentences.

It’s basically what I call a ‘baby rule’, forbidding a given practice until the practitioner is experienced enough to know when it’s safe to use it. I don’t think there’s any need for it around here; even our rank beginners are grown-ups, too sophisticated in their own languages to need that sort of restriction.

<rant>

(But if you want something real to grouse about, I suggest you take aim at the absurd practice, now epidemic in business writing, of following conjunctions with commas.)

</rant>

Catija asks for examples from the Best Writers. Here are three, from the past three centuries, by authors who cannot conceivably be accused of innovative barbarism or vulgar colloquiality:

… The western isle might be improved into a valuable possession, and the Britons would wear their chains with the less reluctance, if the prospect and example of freedom were on every side removed from before their eyes.

But the superior merit of Agricola soon occasioned his removal from the government of Britain … —Edward Gibbon, The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire

Everybody, too, would be willing to admit, as a general proposition, that the critical faculty is lower than the inventive. But is it true that criticism is really, in itself, a baneful and injurious employment ; is it true that all time given to writing critiques on the works of others would be much better employed if it were given to original composition, of whatever kind this may be?

—Matthew Arnold, The Function of Criticism at the Present Time

Significant though that breakthrough was, however, and though he passed another civil rights bill in 1960, liberal antagonism toward him had softened scarcely at all since the bills were weak, only meagre advances toward social justice, and because his championing of them was regarded by most liberals as mere political opportunism: an attempt to lessen northern opposition to his presidential candidacy.

But although the cliché says that power always corrupts, what is seldom said, but what is equally true, is that power always reveals.

—Robert Caro, The Passage of Power

My conjecture that the prohibition of sentence-initial coordinating conjunctions would be found to have originated among 18th-century normative grammarians appears to be false. Goold Brown (The Grammar of English Grammars, 1851), who takes great pleasure in discovering and exploring “disputed points”, does not mention this matter, but states flatly that “The period is often employed between two sentences which have a general connexion, expressed by a personal pronoun, a conjunction, or a conjunctive adverb [emphasis mine].”

The “rule” does arise in educational circles. George Payn Quackenbos, in Advanced Course of Composition and Rhetoric, 1857, 88, is the first author I find taking issue with the practice:

[I]t is not proper to place a period immediately before a conjunction which closely connects what follows with what precedes. This is frequently done in the translation of the Scriptures, where we have verse after verse commencing with and; but it is not authorized by good modern usage. In such cases, either the passage so introduced ought to form part of the preceding sentence, and be separated from it only by a colon or semicolon; or else, if this is impracticable on account of the great length or intricacy it would involve, the following sentence should be remodelled in such a way as to commence with some other word. These remarks apply to all conjunctions that form a decided connection between the parts; such as merely signify to continue the narrative, and imply no connection with what precedes, may without impropriety introduce a new sentence.

As the substance of the preceding paragraph, we may lay down the following general rule, remembering that there are occasional exceptions:—A sentence should not commence with the conjunctions and, for, or however; but may do so with but, now, and moreover.

M. Barrett’s remarks on Misuse of the Word “And” in The American Educational Monthly for April, 1870, 159-60, elevates Quackenbos’ measured deprecation of sentence-initial and to a frank prohibition [the spelling <preceeds> is his]:

”And” is a conjunction, whose office is explained in the etymology of the word “conjunction”, i.e. to join together. Says Webster, “it signifies that a word or part of a sentence is to be added to what preceeds.”

The period indicates a completion, and is used to separate that which preceeds from what follows. It is properly called a full stop.

Then, it is evidently improper, inconsistent, and contradictory to commence a sentence after a period with the conjunction and. The one tells us to divide, the other tells us to unite, and both at the same time.

This is answered in the May issue, 204-5 by ‘S.W.W.’, who points out that the argument ‘proves too much’, is ‘sophistical’, and is ‘opposed to the practice of scholarly writers’ such Steele, Addison, Junius, and Macauley, and concludes

That the conjunction and is often improperly used, not only at the commencement of sentences but elsewhere, we admit. But the idea that a sentence should never begin with it is absurd. It would be quite as sensible and worthy of consideration to insist that a sentence should never begin with but or nor.

(You can read Mr. Barrett’s heated rejoinder in the July issue, 289-93.)

By 1885 both the “rule” (at least with respect to and) and the resistance seem to have reached Scotland, where a schoolgirl in Louisa M. Gray’s Mine Own People) complains

”My essay was best again,” said Gretchen. “Well, you and I, Anna, who know what a poor piece of composition it was, may guess what the others were like! But would you believe it?—Mr. Anderson objected to one of my sentences, because it began with ‘And!’ Now, wasn’t it ridiculous? Anna, isn’t it perfectly allowable to begin a sentence with ‘And ?’ Don’t the very best authors do it?”

I’m on Gretchen’s side.

The word but is one of the seven coordinating conjunctions in English (the others are and, or, so, for, nor, and yet). It’s used to connect two statements that contrast or contradict each other in some way.

For example, learning English is difficult but fun! But getting into the specifics of such commonly used words can be tricky. This article will answer some questions you may have about how to use but.

When do I use a comma?

According to standard grammar, a comma is used before a coordinating conjunction to connect two independent clauses.

An independent clause is a clause with both a subject and a verb so that it can stand on its own. If the second clause does not contain a subject, then no comma is needed.

- He liked the meal, but not the dessert. (No comma)

- He liked the meal, but didn’t like the dessert. (No comma)

- He liked the meal, but he didn’t like the dessert. (Here, the subject is listed both times, making both clauses independent. A comma is appropriate.)

However, this is a rule that not many native speakers are aware of. Most people will place commas according to where they would naturally make a small pause while speaking.

When do I use “but rather”?

While but can be used to contrast two statements, it can also be used in the construction “not this but that.” For example:

- It wasn’t a drought but more of a dry spell.

This sentence is saying that whatever happened wasn’t a drought. Instead, it was a dry spell. To convey this idea, we use the conjunction but. We could also replace this with the phrase but rather.

- It wasn’t a drought but rather more of a dry spell.

The phrase but rather could also just be a combination of but and rather in their separate usages.

- You’d think he would break up with her face-to-face. But rather than doing that, he decided to do it over the phone. (Here, but is used as a contrast to the previous sentence, not in combination with rather.)

What’s the difference between “but” or “yet”?

But and yet are conjunctions with very similar meanings, and usually, when you can use the word yet, you can replace it with but.

The difference is that yet means something more like “despite that” or “regardless of that.” Grammatically speaking, it has a concessive meaning.

- He’s given her so many red flags, yet she still wants to be with him. (In other words, He’s given her so many red flags. Despite that, she still wants to be with him.)

- I attended every lecture in the class, and yet I still don’t understand anything. (It’s possible to use yet with and, making it more of an adverb than a conjunction.)

- Apparently, she keeps a calendar, yet she always forgets about the plans she makes.

In all these examples, you could probably replace yet with but and still have it make sense.

- He’s given her so many red flags, but she still wants to be with him.

- I attended every lecture in the class, but I still don’t understand anything.

- Apparently, she keeps a calendar, but she always forgets about the plans she makes.

The difference is that but only creates a simple contrast. If you really want to say, “This is true, but none of it really matters because…”, then yet is a much better way to convey that nuance.

When can I use “but” at the beginning of a sentence?

While you may have formally been taught that a sentence can’t begin with a conjunction, the reality is that you can begin any sentence with a conjunction. The two following examples basically mean the same thing:

- I’ll come with you and keep you company if you want. But I’m not going to enjoy it.

- I’ll come with you and keep you company if you want, but I’m not going to enjoy it.

Why make a clause with a conjunction its own separate sentence? It depends on how you like to break up your sentences.

Periods usually convey more of a break between ideas than commas do. You might also want to avoid run-on sentences that use too many commas.

When do I use “but also”?

The phrase but also is similar to but rather, but instead of meaning “not this but that,” it means “not just this but also that.” It’s used to add even more additional information than might be expected.

- They not only spilled beer all over the floor but also broke one of the lamps.

- You’re not just a mother but also a friend.

When using this phrase, be sure to create parallel constructions if you want to be grammatically correct. This means linking phrases of the same kind together.

In the following sentence, the placement of the word only makes it so that it connects nouns together, therefore making it a parallel construction.

- He doesn’t know only Spanish but also Portuguese and Italian.

This next sentence is incorrect because it connects a verb (“to know”) with nouns (“Portuguese and Italian”).

- He not only knows Spanish but also Portuguese and Italian.

When I can I use “but not limited to”?

You can use the phrase including but not limited to when you want to list some items in a category, but you also want to indicate there are many more besides that.

It basically means the same thing as the word including by itself but emphasizes the high amount of things in a given category. Usually, this phrase is found in legal contexts, maybe because the wording is more precise.

- The job involves many tasks, including but not limited to serving customers, checking inventory, cleaning the workspace, and taking phone calls.

- Natural language processing has a wide variety of applications, including but not limited to chatbots, language translation, sentiment analysis, and spell check.

- The book covers many topics, including but not limited to the Civil War, the Reconstruction Era, and Jim Crow laws.

What’s the difference between “but” and “although”?

This question is tricky because although can have two different usages.

The first is to mean “despite the fact that” or “even though,” which is like saying, “What I’m about to say doesn’t really matter.” In this case, the clause that although introduces will usually come before the main clause.

- Although it was scorching outside, we still decided risk sunburns and go hiking.

- Although I had a test the next morning, I decided to go out with my friends and ended up coming home late.

Then there is the second usage of although, which is to mean the same thing as but, except it tends to indicate more of an afterthought rather than a firm contrast.

This is usually when although comes after the main clause, which is how you’ll be able to tell the difference between the two meanings.

- I really didn’t want to go to the show, although it did end up being somewhat interesting. (This can be like saying, Now that I think about it, it was sort of interesting.)

- Mark’s thinking about transferring schools, although I’m not sure why. I thought he liked it here. (Using although instead of but indicates that the main topic is about Mark, not what the speaker thinks.)

If you want to create a contrast or transition between what you were just talking about and a topic that’s just as important, it might be better to use but instead of although, such as in this sentence:

- Mental illness can be difficult or awkward to talk about, but there are many ways we can be supportive.

The main point is not that mental illness is a difficult subject. Instead, the speaker is trying to transition into a topic they want to talk about. This makes but a much more appropriate choice than although.

What’s the difference between “but” and “except”?

Except (that) is another conjunction that means something similar to but, except it indicates more of an exception than a contrast (I just used it now!).

Maybe you want to state something that’s true except for one detail. In that case, except will help you convey that better than but.

- He and I are on good terms, except he still needs to pay me the money he owes.

- We have everything we need for dinner, except that I still need to buy oil.

- A: Everything’s fine, except…

B: Except what?

Don’t confuse this with the phrase except for, which is used as a preposition, not a conjunction. You can only follow it with noun phrases.

- Everyone submitted their entries on time except for him.

- He and I are on good terms, except for the fact that he still needs to pay me the money he owes.

Practice

Time for some practice! The following sentences each have an error in them. Try to spot them and see if you can correct them.

- It’s not the concerts themselves rather the social experience that I enjoy.

- I can teach you how to play many genres, including and not limited to jazz, rock, country, and the blues.

- He drives not only poorly but also can’t park properly.

- A lot of times, we follow rules, but don’t really understand why.

- He spent hours and hours more on the painting, but it still looks bad. (What could you replace but with to show that his work was useless?)

- Overall, the movie was great, but the ending could have been better. (What could you replace but with to indicate more of an exception?)

- Overall, the movie was great, but the ending could have been better. (What could you replace but with to indicate more of an afterthought?)

Answers:

- It’s not the concerts themselves but rather the social experience that I enjoy. (You need the whole phrase but rather, not just rather.)

- I can teach you how to play many genres, including but not limited to jazz, rock, country, and the blues. (“Including and not limited to” is not a standard expression.)

- He not only drives poorly but also can’t park properly. OR Not only does he drive poorly, but he also can’t park properly. (Either of these makes the sentence a parallel construction.)

- A lot of times, we follow the rules but don’t really understand why. (The second clause is not an independent clause, so you don’t need to use a comma.)

- He spent hours and hours more on the painting, yet it still looks bad. (Now, you can tell more how useless his effort was.)

- Overall, the movie was great, except the ending could have been better. (Now, it’s specified that the ending was really the one thing wrong with the movie.)

- Overall, the movie was great, although the ending could have been better. (Now, it sounds more like the speaker doesn’t care as much about the ending.)