Тема «Животные Animals» — одна из первых, с которой сталкиваются при изучении английского языка. Сегодня мы разберем, как называются по-английски домашние животные, дикие животные, группы животных (такие как стая), а также узнаем, как «говорят» животные на английском языке. Все слова приведены с транскрипцией и переводом.

Читайте также: «Упражнения: животные на английском языке».

Названия домашних животных на английском языке

| domestic animals | [dəʊˈmɛstɪk ˈænɪməlz] | домашние животные |

| cow | [kaʊ] | корова |

| bull | [bʊl] | бык |

| horse | [hɔːs] | лошадь |

| stallion | [ˈstæljən] | жеребец |

| mare | [meə] | кобыла |

| goat | [gəʊt] | коза |

| he goat | [hiː] [gəʊt] | козел |

| sheep | [ʃiːp] | овца |

| ram | [ræm] | баран |

| donkey | [ˈdɒŋki] | осел |

| mule | [mjuːl] | мул |

| pig | [pɪg] | свинья |

| cat | [kæt] | кошка |

| dog | [dɒg] | собака |

| calf | [kɑːf] | теленок |

| lamb | [læm] | ягненок |

| foal | [fəʊl] | жеребенок |

| piglet | [ˈpɪglət] | поросенок |

| kitten | [ˈkɪtn] | котенок |

| puppy | [ˈpʌpi] | щенок |

| mouse | [maʊs] | мышь |

| rat | [ræt] | крыса |

| chinchilla | [ʧɪnˈʧɪlə] | шиншилла |

| hamster | [ˈhæmstə] | хомяк |

| guinea pig (cavy) | [ˈgɪni pɪg] [ˈkeɪvi] | морская свинка |

Примечание:

- Множественное число слова mouse — mice, а не mouses.

- Слово sheep во множественном числе тоже sheep (формы совпадают).

Дикие животные на английском языке

| wild animal | [waɪld ˈænɪməl] | дикое животное |

| wolf | [wʊlf] | волк |

| fox | [fɒks] | лиса |

| bear | [beə] | медведь |

| tiger | [ˈtaɪgə] | тигр |

| lion | [ˈlaɪən] | лев |

| elephant | [ˈɛlɪfənt] | слон |

| ape (monkey) | [eɪp] [ˈmʌŋki] | обезьяна |

| camel | [ˈkæməl] | верблюд |

| rabbit | [ˈræbɪt] | кролик |

| hare | [heə] | заяц |

| antelope | [ˈæntɪləʊp] | антилопа |

| badger | [ˈbæʤə] | барсук |

| squirrel | [ˈskwɪrəl] | белка |

| beaver | [ˈbiːvə] | бобр |

| zebra | [ˈziːbrə] | зебра |

| kangaroo | [ˌkæŋgəˈruː] | кенгуру |

| crocodile | [ˈkrɒkədaɪl] | крокодил |

| rhino (rhinoceros) | [ˈraɪnəʊ] [raɪˈnɒsərəs] | носорог |

| deer | [dɪə] | олень |

| lynx | [lɪŋks] | рысь |

| seal | [siːl] | тюлень |

| tortoise (turtle) | [ˈtɔːtəs] [ˈtɜːtl] | черепаха |

| cheetah | [ˈʧiːtə] | гепард |

| hyena | [haɪˈiːnə] | гиена |

| raccoon | [rəˈkuːn] | енот |

| giraffe | [ʤɪˈrɑːf] | жираф |

| hedgehog | [ˈhɛʤhɒg] | ёж |

| leopard | [ˈlɛpəd] | леопард |

| panther | [ˈpænθə] | пантера |

| elk (moose) | [ɛlk] ([muːs]) | лось |

| anteater | [ˈæntˌiːtə] | муравьед |

| opossum (possum) | [əˈpɒsəm] ([ˈpɒsəm]) | опоссум |

| puma (cougar) | [ˈpjuːmə] ([ˈkuːgə]) | пума |

| wolverine | [ˈwʊlvəriːn] | росомаха |

| dinosaur | [ˈdaɪnəʊsɔː] | динозавр |

Примечание: слово deer во множественном числе тоже deer, формы совпадают.

Группы животных на английском

Помимо названий отдельных животных, существуют называния групп животных. По-русски мы говорим стадо овец, стая волков, но никак не стадо волков и стая овец. Вот, как называются группы животных на английском с приблизительным переводом (приблизительным, потому что точный зависит от контекста):

| Название группы | Транскрипция | Приблизительный перевод |

|---|---|---|

| colony (of ants, rabbits) | [ˈkɒləni] | колония |

| swarm (of bees, flies, butterflies) | [swɔːm] | рой |

| flock (of birds, geese) | [flɒk] | стая |

| herd (of cattle, pigs, sheep, goats) | [hɜːd] | стадо |

| pack (of dogs, wolves) | [pæk] | стая, свора |

| school (of fish) | [skuːl] | стая, косяк |

| pride (of lions) | [praɪd] | прайд, стая |

| nest (of snakes) | [nɛst] | гнездо |

| litter (of puppies, kittens) | [ˈlɪtə] | выводок, приплод, помет |

Как видите, некоторые слова похожи на русские, некоторые сильно отличаются: мы тоже говорим «колония муравьев», но не говорим «колония кроликов». Больше всего меня позабавило, что группа котят, щенят и других детенышей называется litter — буквально, разбросанные вещи, мусор, беспорядок.

Что говорят животные на английском языке? Песня для детей

Еще одна интересная тема, касающаяся животных — это то, как в английском передается их «речь». К примеру, мы говорим, что птичка чирикает «чирик-чирик», а свинья хрюкает «хрю-хрю», но англичанин скажет, что птичка чирикает «твит-твит», а свинья хрюкает «ойнк, ойнк».

Здесь нужно выделить две группы слов:

- Звукоподражания вроде «кря-кря», «хрю-хрю».

- Глаголы, называющие сам процесс «речи», например: крякать, хрюкать.

Звукоподражания хорошо продемонстрированы в этой детской песенке:

А вот список некоторых, скажем так, глаголов речи. В скобках — названия животных и птиц, к которым могут относиться эти действия.

| growl | [graʊl] | реветь, рычать |

| squeak | [skwiːk] | пищать |

| scream | [skriːm] | кричать |

| roar | [rɔː] | реветь, рычать |

| cluck | [klʌk] | кудахтать |

| moo | [muː] | мычать |

| chirp | [ʧɜːp] | стрекотать |

| bleat | [bliːt] | блеять |

| bark | [bɑːk] | лаять |

| howl | [haʊl] | выть |

| quack | [kwæk] | квакать |

| hiss | [hɪs] | шипеть |

| laugh | [lɑːf] | смеяться |

| tweet | [twiːt] | чирикать |

| meow | [miːˈaʊ] | мяукать |

| purr | [pɜː] | мурлыкать |

Теперь рассмотрим к каким животным относятся эти «глаголы речи»:

- growl — медведи, тигры, львы

- squeak — грызуны (мыши, шиншиллы и др.), кролики

- scream — обезьяны

- roar — львы, медведи

- cluck — курицы

- moo — коровы

- chirp — сверчки, цикады

- bleat — козы, овцы

- bark — собаки

- howl — собаки, волки

- quack — утки

- hiss — змеи

- tweet — птицы

- meow, purr — кошки

Приведу примеры с некоторыми глаголами:

Can you hear the dogs barking? Go, check the backyard. — Слышишь, собаки лают? Сходи, проверь задний двор.

Whose cat is meowing ouside for like an hour? — Чья это кошка уже где-то час мяукает на улице?

The mouse sqeaked and hid under the pillow. — Мышь пискнула и спряталась под подушкой.

My neighbor’s dog howls like a wolf every night. — Собака моего соседа воет как волк каждую ночь.

Здравствуйте! Меня зовут Сергей Ним, я автор этого сайта, а также книг, курсов, видеоуроков по английскому языку.

Подпишитесь на мой Телеграм-канал, чтобы узнавать о новых видео, материалах по английскому языку.

У меня также есть канал на YouTube, где я регулярно публикую свои видео.

The domestic dog (Canis lupus familiaris[3] and Canis lupus dingo[1][2]) is a domesticated form of the gray wolf, a member of the Canidae family of the order Carnivora. The term is used for both feral and pet varieties. The dog may have been the first animal to be domesticated, and has been the most widely kept working, hunting, and companion animal in human history. The word «dog» may also mean the male of a canine species,[4] as opposed to the word «bitch» for the female of the species.[5]

Dogs were domesticated from gray wolves about 15,000 years ago.[6] Their value to early human settlements led to them quickly becoming ubiquitous across world cultures. Dogs perform many roles for people, such as hunting, herding, pulling loads, protection, assisting police and military, companionship, and, more recently, aiding handicapped individuals. This impact on human society has given them the nickname «Man’s Best Friend» in the Western world. In 2001, there were estimated to be 400 million dogs in the world.[7]

Over the 15,000-year span in which the dog has been domesticated, it has diverged into only a handful of landraces, groups of similar animals whose morphology and behavior have been shaped by environmental factors and functional roles. Through selective breeding by humans, the dog has developed into hundreds of varied breeds, and shows more behavioral and morphological variation than any other land mammal.[8] For example, height measured to the withers ranges from a few inches in the Chihuahua to a few feet in the Irish Wolfhound; color varies from white through grays (usually called «blue») to black, and browns from light (tan) to dark («red» or «chocolate») in a wide variation of patterns; coats can be short or long, coarse-haired to wool-like, straight, curly, or smooth.[9] It is common for most breeds to shed this coat.

Contents

- 1 Etymology and related terminology

- 2 Taxonomy

- 3 History and evolution

- 3.1 DNA studies

- 4 Roles with humans

- 4.1 Early roles

- 4.2 As pets

- 4.3 Work

- 4.4 Sports and shows

- 4.5 As a food source

- 4.6 Health risks to humans

- 4.7 Health benefits for humans

- 4.8 Shelters

- 5 Biology

- 5.1 Senses

- 5.1.1 Vision

- 5.1.2 Hearing

- 5.1.3 Smell

- 5.2 Physical characteristics

- 5.2.1 Coat

- 5.2.2 Tail

- 5.3 Types and breeds

- 5.4 Health

- 5.4.1 Mortality

- 5.4.2 Predation

- 5.5 Diet

- 5.6 Reproduction

- 5.7 Neutering

- 5.1 Senses

- 6 Intelligence and behavior

- 6.1 Intelligence

- 6.2 Behavior

- 6.2.1 Sleep

- 6.3 Dog growl

- 7 Differences from wolves

- 7.1 Physical characteristics

- 7.2 Behavior

- 7.3 Trainability

- 8 Mythology

- 9 Gallery of dogs in art

- 10 See also

- 11 References

- 12 External links

Etymology and related terminology

Dog is the common use term that refers to members of the subspecies Canis lupus familiaris (canis, «dog»; lupus, «wolf»; familiaris, «of a household» or «domestic»). The term can also be used to refer to a wider range of related species, such as the members of the genus Canis, or «true dogs», including the wolf, coyote, and jackals; or it can refer to the members of the tribe Canini, which would also include the African wild dog; or it can be used to refer to any member of the family Canidae, which would also include the foxes, bush dog, raccoon dog, and others.[10] Some members of the family have «dog» in their common names, such as the raccoon dog and the African wild dog. A few animals have «dog» in their common names but are not canids, such as the prairie dog.

The English word dog comes from Middle English dogge, from Old English docga, a «powerful dog breed».[11] The term may derive from Proto-Germanic *dukkōn, represented in Old English finger-docce («finger-muscle»).[12] The word also shows the familiar petname diminutive -ga also seen in frogga «frog», picga «pig», stagga «stag», wicga «beetle, worm», among others.[13] Due to the archaic structure of the word, the term dog may ultimately derive from the earliest layer of Proto-Indo-European vocabulary, reflecting the role of the dog as the earliest domesticated animal.[14]

Mbabaram is famous in linguistic circles for a striking coincidence in its vocabulary to English. When linguist R. M. W. Dixon began his study of the language by eliciting a few basic nouns among the first of these was the word for «dog» which coincidentally in Mbabaram is dog. The Mbabaram word for «dog» really is pronounced almost identically to the English word (compare true cognates such as Yidiny gudaga, Dyirbal guda, Djabugay gurraa and Guugu Yimidhirr gudaa, for example). The similarity is a complete coincidence: there is no discernible relationship between English and Mbabaram. This and other false cognates are often cited as a caution against deciding that languages are related based on a small number of comparisons.

In 14th-century England, hound (from Old English: hund) was the general word for all domestic canines, and dog referred to a subtype of hound, a group including the mastiff. It is believed this «dog» type of «hound» was so common it eventually became the prototype of the category “hound”.[15] By the 16th century, dog had become the general word, and hound had begun to refer only to types used for hunting.[16] Hound, cognate to German Hund, Dutch hond, common Scandinavian hund, and Icelandic hundur, is ultimately derived from the Proto-Indo-European *kwon- «dog», found in Welsh ci (plural cwn), Latin canis, Greek kýōn, Lithuanian šuõ.[17]

In breeding circles, a male canine is referred to as a dog, while a female is called a bitch (Middle English bicche, from Old English bicce, ultimately from Old Norse bikkja). A group of offspring is a litter. The father of a litter is called the sire, and the mother is called the dam. Offspring are, in general, called pups or puppies, from French poupée, until they are about a year old. The process of birth is whelping, from the Old English word hwelp (cf. German Welpe, Dutch welp, Swedish valpa, Icelandic hvelpur).[18]

Taxonomy

The domestic dog was originally classified as Canis familiaris and Canis familiarus domesticus by Carolus Linnaeus in 1758,[19][20] and was reclassified in 1993 as Canis lupus familiaris, a subspecies of the gray wolf Canis lupus, by the Smithsonian Institution and the American Society of Mammalogists. Overwhelming evidence from behavior, vocalizations, morphology, and molecular biology led to the contemporary scientific understanding that a single species, the gray wolf, is the common ancestor for all breeds of domestic dogs;[21][22] however, the timeframe and mechanisms by which dogs diverged are controversial.[21] Canis lupus familiaris is listed as the name for the taxon that is broadly used in the scientific community and recommended by ITIS; Canis familiaris, however, is a recognised synonym.[23]

History and evolution

Domestic dogs inherited complex behaviors from their wolf ancestors, being pack hunters with complex body language. These sophisticated forms of social cognition and communication may account for their trainability, playfulness, and ability to fit into human households and social situations, and these attributes have given dogs a relationship with humans that has enabled them to become one of the most successful species on the planet today.[21]

Although experts largely disagree over the details of dog domestication, it is agreed that human interaction played a significant role in shaping the subspecies.[24] Shortly after domestication, dogs became ubiquitous in human populations, and spread throughout the world. Emigrants from Siberia likely crossed the Bering Strait with dogs in their company, and some experts[who?] suggest the use of sled dogs may have been critical to the success of the waves that entered North America roughly 12,000 years ago,[citation needed] although the earliest archaeological evidence of dog-like canids in North America dates from about 9,000 years ago.[25] Dogs were an important part of life for the Athabascan population in North America, and were their only domesticated animal. Dogs also carried much of the load in the migration of the Apache and Navajo tribes 1,400 years ago. Use of dogs as pack animals in these cultures often persisted after the introduction of the horse to North America.[26][page needed]

The current consensus among biologists and archaeologists is that the dating of first domestication is indeterminate.[24][26] There is conclusive evidence dogs genetically diverged from their wolf ancestors at least 15,000 years ago,[6][27][28] but some believe domestication to have occurred earlier.[24] It is not known whether humans domesticated the wolf as such to initiate dog’s divergence from its ancestors, or whether dog’s evolutionary path had already taken a different course prior to domestication. For example, it is hypothesized that some wolves gathered around the campsites of paleolithic camps to scavenge refuse, and associated evolutionary pressure developed that favored those who were less frightened by, and keener in approaching, humans.

The bulk of the scientific evidence for the evolution of the domestic dog stems from archaeological findings and mitochondrial DNA studies. The divergence date of roughly 15,000 years ago is based in part on archaeological evidence that demonstrates the domestication of dogs occurred more than 15,000 years ago,[21][26] and some genetic evidence indicates the domestication of dogs from their wolf ancestors began in the late Upper Paleolithic close to the Pleistocene/Holocene boundary, between 17,000 and 14,000 years ago.[29] But there is a wide range of other, contradictory findings that make this issue controversial.

Archaeological evidence suggests the latest dogs could have diverged from wolves was roughly 15,000 years ago, although it is possible they diverged much earlier.[21] In 2008, a team of international scientists released findings from an excavation at Goyet Cave in Belgium declaring a large, toothy canine existed 31,700 years ago and ate a diet of horse, musk ox and reindeer.[30]

Prior to this Belgian discovery, the earliest dog fossils were two large skulls from Russia and a mandible from Germany dated from roughly 14,000 years ago.[6][21] Remains of smaller dogs from Natufian cave deposits in the Middle East, including the earliest burial of a human being with a domestic dog, have been dated to around 10,000 to 12,000 years ago.[6][31] There is a great deal of archaeological evidence for dogs throughout Europe and Asia around this period and through the next two thousand years (roughly 8,000 to 10,000 years ago), with fossils uncovered in Germany, the French Alps, and Iraq, and cave paintings in Turkey.[21] The oldest remains of a domesticated dog in the Americas were found in Texas and have been dated to about 9,400 years ago.[32]

DNA studies

DNA studies have provided a wide range of possible divergence dates, from 15,000 to 40,000 years ago,[6] to as much as 100,000 to 140,000 years ago.[33] These results depend on a number of assumptions.[21] Genetic studies are based on comparisons of genetic diversity between species, and depend on a calibration date. Some estimates of divergence dates from DNA evidence use an estimated wolf-coyote divergence date of roughly 700,000 years ago as a calibration.[34] If this estimate is incorrect, and the actual wolf-coyote divergence is closer to one or two million years ago, or more,[35] then the DNA evidence that supports specific dog-wolf divergence dates would be interpreted very differently.

Furthermore, it is believed the genetic diversity of wolves has been in decline for the last 200 years, and that the genetic diversity of dogs has been reduced by selective breeding. This could significantly bias DNA analyses to support an earlier divergence date. The genetic evidence for the domestication event occurring in East Asia is also subject to violations of assumptions. These conclusions are based on the location of maximal genetic divergence, and assume hybridization does not occur, and that breeds remain geographically localized. Although these assumptions hold for many species, there is good reason to believe that they do not hold for canines.[21]

Genetic analyses indicate all dogs are likely descended from a handful of domestication events with a small number of founding females,[21][29] although there is evidence domesticated dogs interbred with local populations of wild wolves on several occasions.[6] Data suggest dogs first diverged from wolves in East Asia, and these domesticated dogs then quickly migrated throughout the world, reaching the North American continent around 8000 BC.[6] The oldest groups of dogs, which show the greatest genetic variability and are the most similar to their wolf ancestors, are primarily Asian and African breeds, including the Basenji, Lhasa Apso, and Siberian Husky.[36] Some breeds thought to be very old, such as the Pharaoh Hound, Ibizan Hound, and Norwegian Elkhound, are now known to have been created more recently.[36]

There is a great deal of controversy surrounding the evolutionary framework for the domestication of dogs.[21] Although it is widely claimed that «man domesticated the wolf,»[37] man may not have taken such a proactive role in the process.[21] The nature of the interaction between man and wolf that led to domestication is unknown and controversial. At least three early species of the Homo genus began spreading out of Africa roughly 400,000 years ago, and thus lived for a considerable time in contact with canine species. Despite this, there is no evidence of any adaptation of canine species to the presence of the close relatives of modern man. If dogs were domesticated, as believed, roughly 15,000 years ago, the event (or events) would have coincided with a large expansion in human territory and the development of agriculture. This has led some biologists to suggest one of the forces that led to the domestication of dogs was a shift in human lifestyle in the form of established human settlements. Permanent settlements would have coincided with a greater amount of disposable food and would have created a barrier between wild and anthropogenic canine populations.[21]

Roles with humans

Early roles

Wolves, and their dog descendants, would have derived significant benefits from living in human camps—more safety, more reliable food, lesser caloric needs, and more chance to breed.[38] They would have benefited from humans’ upright gait that gives them larger range over which to see potential predators and prey, as well as color vision that, at least by day, gives humans better visual discrimination.[38] Camp dogs would also have benefitted from human tool use, as in bringing down larger prey and controlling fire for a range of purposes.[38]

Humans would also have derived enormous benefit from the dogs associated with their camps.[39] For instance, dogs would have improved sanitation by cleaning up food scraps.[39] Dogs may have provided warmth, as referred to in the Australian Aboriginal expression “three dog night” (an exceptionally cold night), and they would have alerted the camp to the presence of predators or strangers, using their acute hearing to provide an early warning.[39] Anthropologists believe the most significant benefit would have been the use of dogs’ sensitive sense of smell to assist with the hunt.[39] The relationship between the presence of a dog and success in the hunt is often mentioned as a primary reason for the domestication of the wolf, and a 2004 study of hunter groups with and without a dog gives quantitative support to the hypothesis that the benefits of cooperative hunting was an important factor in wolf domestication.[40]

The cohabitation of dogs and humans would have greatly improved the chances of survival for early human groups, and the domestication of dogs may have been one of the key forces that led to human success.[41]

As pets

“The most widespread form of interspecies bonding occurs between humans and dogs”[39] and the keeping of dogs as companions, particularly by elites, has a long history.[42] However, pet dog populations grew significantly after World War II as suburbanization increased.[42] In the 1950s and 1960s, dogs were kept outside more often than they tend to be today [43] (using the expression “in the doghouse” to describe exclusion from the group signifies the distance between the doghouse and the home) and were still primarily functional, acting as a guard, children’s playmate, or walking companion. From the 1980s, there have been changes in the role of the pet dog, such as the increased role of dogs in the emotional support of their owners.[44] People and dogs have become increasingly integrated and implicated in each other’s lives,[45] to the point where pet dogs actively shape the way a family and home are experienced.[46]

There have been two major trends in the changing status of pet dogs. The first has been the ‘commodification’ of the dog, shaping it to conform to human expectations of personality and behaviour.[46] The second has been the broadening of the concept of the family and the home to include dogs-as-dogs within everyday routines and practices.[46]

There are a vast range of commodity forms available to transform a pet dog into an ideal companion.[47] The list of goods, services and places available is enormous: from dog perfumes, couture, furniture and housing, to dog groomers, therapists, trainers and care-takers, dog cafes, spas, parks and beaches, and dog hotels, airlines and cemeteries.[47] While dog training as an organized activity can be traced back to the 18th century, in the last decades of the 20th century it became a high profile issue as many normal dog behaviors such as barking, jumping up, digging, rolling in dung, fighting, and urine marking became increasingly incompatible with the new role of a pet dog.[48] Dog training books, classes and television programs proliferated as the process of commodifying the pet dog continued.[49]

A pet dog taking part in Christmas traditions

The majority of contemporary dog owners describe their dog as part of the family,[46] although some ambivalence about the relationship is evident in the popular reconceptualisation of the dog-human family as a pack.[46] A dominance model of dog-human relationships has been promoted by some dog trainers, such as on the television program Dog Whisperer. However it has been disputed that «trying to achieve status» is characteristic of dog–human interactions.[50] Pet dogs play an active role in family life; for example, a study of conversations in dog-human families showed how family members use the dog as a resource, talking to the dog, or talking through the dog, to mediate their interactions with each other.[51] Another study of dogs’ roles in families showed many dogs have set tasks or routines undertaken as family members, the most common of which was helping with the washing-up by licking the plates in the dishwasher, and bringing in the newspaper from the lawn.[46] Increasingly, human family members are engaging in activities centred on the perceived needs and interests of the dog, or in which the dog is an integral partner, such as Dog Dancing and Doga.[47]

According to the statistics published by the American Pet Products Manufacturers Association in the National Pet Owner Survey in 2009–2010, it is estimated there are 77.5 million dog owners in the United States.[52] The same survey shows nearly 40% of American households own at least one dog, of which 67% own just one dog, 25% two dogs and nearly 9% more than two dogs. There does not seem to be any gender preference among dogs as pets, as the statistical data reveal an equal number of female and male dog pets. Yet, although several programs are undergoing to promote pet adoption, less than a fifth of the owned dogs come from a shelter.

Work

Dogs have lived and worked with humans in so many roles that they have earned the unique nickname, «man’s best friend»,[53] a phrase used in other languages as well. They have been bred for herding livestock,[54] hunting (e.g. pointers and hounds),[55] rodent control,[3] guarding, helping fishermen with nets, detection dogs, and pulling loads, in addition to their roles as companions.[3]

Gaston III, Count of Foix, Book of the Hunt, 1387–88

Service dogs such as guide dogs, utility dogs, assistance dogs, hearing dogs, and psychological therapy dogs provide assistance to individuals with physical or mental disabilities.[56][57] Some dogs owned by epileptics have been shown to alert their handler when the handler shows signs of an impending seizure, sometimes well in advance of onset, allowing the owner to seek safety, medication, or medical care.[58]

Dogs included in human activities in terms of helping out humans are usually called working dogs. Dogs of several breeds are considered working dogs. Some working dog breeds include Akita, Alaskan Malamute, Anatolian Shepherd Dog, Bernese Mountain Dog, Black Russian Terrier, Boxer, Bullmastiff, Doberman Pinscher, Dogue de Bordeaux, German Pinscher, German Shepherd,[59] Giant Schnauzer, Great Dane, Great Pyrenees, Great Swiss Mountain Dog, Komondor, Kuvasz, Mastiff, Neapolitan Mastiff, Newfoundland, Portuguese Water Dog, Rottweiler, Saint Bernard, Samoyed, Siberian Husky, Standard Schnauzer, and Tibetan Mastiff.

Sports and shows

Owners of dogs often enter them in competitions[60] such as breed conformation shows or sports, including racing and sledding.

In conformation shows, also referred to as breed shows, a judge familiar with the specific dog breed evaluates individual purebred dogs for conformity with their established breed type as described in the breed standard. As the breed standard only deals with the externally observable qualities of the dog (such as appearance, movement, and temperament), separately tested qualities (such as ability or health) are not part of the judging in conformation shows.

As a food source

Dog meat is consumed in some East Asian countries, including Korea, China, and Vietnam, a practice that dates back to antiquity.[61] It is estimated that 13–16 million dogs are killed and consumed in Asia every year.[62] The BBC claims that, in 1999, more than 6,000 restaurants served soups made from dog meat in South Korea.[63] In Korea, the primary dog breed raised for meat, the nureongi (누렁이), differs from those breeds raised for pets that Koreans may keep in their homes.[64] The most popular Korean dog dish is gaejang-guk (also called bosintang), a spicy stew meant to balance the body’s heat during the summer months; followers of the custom claim this is done to ensure good health by balancing one’s gi, or vital energy of the body. A 19th century version of gaejang-guk explains that the dish is prepared by boiling dog meat with scallions and chili powder. Variations of the dish contain chicken and bamboo shoots. While the dishes are still popular in Korea with a segment of the population, dog is not as widely consumed as beef, chicken, and pork.[65]

Other cultures, such as Polynesia and pre-Columbian Mexico, also consumed dog meat in their history. However, Western, South Asian, African, and Middle Eastern cultures, in general, regard consumption of dog meat as taboo. In some places, however, such as in rural areas of Poland, dog fat is believed to have medicinal properties—being good for the lungs for instance.[66]

A CNN report in China dated March 2010 interviews a dog meat vendor who states that most of the dogs that are available for selling to restaurant are raised in special farms but that there is always a chance that a sold dog is someone’s lost pet, although dog pet breeds are not considered edible.[67]

Health risks to humans

In the USA, cats and dogs are a factor in more than 86,000 falls each year.[68] It has been estimated around 2% of dog-related injuries treated in UK hospitals are domestic accidents. The same study found that while dog involvement in road traffic accidents was difficult to quantify, dog-associated road accidents involving injury more commonly involved two-wheeled vehicles.[69]

Toxocara canis (dog roundworm) eggs in dog feces can cause toxocariasis. In the United States, about 10,000 cases of Toxocara infection are reported in humans each year, and almost 14% of the US population is infected.[70] In Great Britain, 24% of soil samples taken from public parks contained T. canis eggs.[71] Untreated toxocariasis can cause retinal damage and decreased vision.[71] Dog feces can also contain hookworms that cause cutaneous larva migrans in humans.[72][73][74][75]

The incidence of dog bites, and especially fatal dog bites, is extremely rare in America considering the number of pet dogs in the country.[76] Fatalities from dog bites occur in America at the rate of one per four million dogs.[76] A Colorado study found bites in children were less severe than bites in adults.[77] The incidence of dog bites in the US is 12.9 per 10,000 inhabitants, but for boys aged 5 to 9, the incidence rate is 60.7 per 10,000. Moreover, children have a much higher chance to be bitten in the face or neck.[78] Sharp claws with powerful muscles behind them can lacerate flesh in a scratch that can lead to serious infections.[79]

In the UK between 2003 and 2004, there were 5,868 dog attacks on humans, resulting in 5,770 working days lost in sick leave.[80]

Health benefits for humans

A growing body of research indicates the companionship of a dog can enhance human physical health and psychological wellbeing.[81] Dog and cat owners have been shown to have better mental and physical health than nonowners, making fewer visits to the doctor and being less likely to be on medication than nonowners.[82] In one study, new pet owners reported a highly significant reduction in minor health problems during the first month following pet acquisition, and this effect was sustained in dog owners through to the end of the study. In addition, dog owners took considerably more physical exercise than cat owners and people without pets. The group without pets exhibited no statistically significant changes in health or behaviour. The results provide evidence that pet acquisition may have positive effects on human health and behaviour, and that for dog owners these effects are relatively long term.[83] Pet ownership has also been associated with increased coronary artery disease survival, with dog owners being significantly less likely to die within one year of an acute myocardial infarction than those who did not own dogs.[84]

The health benefits of dogs can result from contact with dogs, not just from dog ownership. For example, when in the presence of a pet dog, people show reductions in cardiovascular, behavioral, and psychological indicators of anxiety.[85] The benefits of contact with a dog also include social support, as dogs are able to not only provide companionship and social support themselves, but also to act as facilitators of social interactions between humans.[86] One study indicated that wheelchair users experience more positive social interactions with strangers when they are accompanied by a dog than when they are not.[87]

The practice of using dogs and other animals as a part of therapy dates back to the late 18th century, when animals were introduced into mental institutions to help socialize patients with mental disorders.[88] Animal-assisted intervention research has shown that animal-assisted therapy with a dog can increase a person with Alzheimer’s disease’s social behaviours, such as smiling and laughing.[89] One study demonstrated that children with ADHD and conduct disorders who participated in an education program with dogs and other animals showed increased attendance, increased knowledge and skill objectives, and decreased antisocial and violent behavior compared to those who were not in an animal-assisted program.[90]

Shelters

Main article: Animal shelter

Every year, between 6 and 8 million dogs and cats enter US animal shelters.[91] The Humane Society of the United States (HSUS) estimates that approximately 3 to 4 million dogs and cats are euthanized yearly in shelters across the United States.[92] However, the percentage of dogs in US animal shelters that are eventually adopted and removed from the shelters by their new owners has increased since the mid 1990s from around 25% up to around 60–75% in the mid first decade of the 21st century.[93]

Pets entering the shelters are euthanized in countries all over the world because of the lack of financial provisions to take care of these animals. Most shelters complain of not having enough resources to feed the pets and by being constrained to kill them, as the likelihood for all of them to find an owner is very small. In poor countries, euthanasia is usually violent.

Biology

Main article: Dog anatomy

Domestic dogs have been selectively bred for millennia for various behaviors, sensory capabilities, and physical attributes.[3] Modern dog breeds show more variation in size, appearance, and behavior than any other domestic animal. Nevertheless, their morphology is based on that of their wild ancestors, gray wolves.[3] Dogs are predators and scavengers, and like many other predatory mammals, the dog has powerful muscles, fused wrist bones, a cardiovascular system that supports both sprinting and endurance, and teeth for catching and tearing. Dogs are highly variable in height and weight. The smallest known adult dog was a Yorkshire Terrier, that stood only 6.3 centimetres (2.5 in) at the shoulder, 9.5 cm (3.7 in) in length along the head-and-body, and weighed only 113 grams (4.0 oz). The largest known dog was an English Mastiff which weighed 155.6 kilograms (343 lb) and was 250 cm (98 in) from the snout to the tail.[94] The tallest dog is a Great Dane that stands 106.7 cm (42.0 in) at the shoulder.[95]

Senses

Vision

Like most mammals, dogs are dichromats and have color vision equivalent to red-green color blindness in humans (deuteranopia).[96][97][98][99] Dogs are less sensitive to differences in grey shades than humans and also can detect brightness at about half the accuracy of humans.[100]

The dog’s visual system has evolved to aid proficient hunting.[96] While a dog’s visual acuity is poor (that of a poodle’s has been estimated to translate to a Snellen rating of 20/75[96]), their visual discrimination for moving objects is very high; dogs have been shown to be able to discriminate between humans (e.g., identifying their owner) at a range of between 800 and 900 m, however this range decreases to 500–600 m if the object is stationary.[96] Dogs have a temporal resolution of between 60 and 70 Hz, which explains why many dogs struggle to watch television, as most such modern screens are optimized for humans at 50–60 Hz.[100] Dogs can detect a change in movement that exists in a single diopter of space within their eye. Humans, by comparison, require a change of between 10 and 20 diopters to detect movement.[101][102]

As crepuscular hunters, dogs often rely on their vision in low light situations: They have very large pupils, a high density of rods in the fovea, an increased flicker rate, and a tapetum lucidum.[96] The tapetum is a reflective surface behind the retina that reflects light to give the photoreceptors a second chance to catch the photons. There is also a relationship between body size and overall diameter of the eye. A range of 9.5 and 11.6 mm can be found between various breeds of dogs. This 20% variance can be substantial and is associated as an adaptation toward superior night vision.[103]

The eyes of different breeds of dogs have different shapes, dimensions, and retina configurations.[104] Many long-nosed breeds have a «visual streak» – a wide foveal region that runs across the width of the retina and gives them a very wide field of excellent vision. Some long-muzzled breeds, in particular, the sighthounds, have a field of vision up to 270° (compared to 180° for humans). Short-nosed breeds, on the other hand, have an «area centralis»: a central patch with up to three times the density of nerve endings as the visual streak, giving them detailed sight much more like a human’s. Some broad-headed breeds with short noses have a field of vision similar to that of humans.[97][98] Most breeds have good vision, but some show a genetic predisposition for myopia – such as Rottweilers, with which one out of every two has been found to be myopic.[96] Dogs also have a greater divergence of the eye axis than humans, enabling them to rotate their pupils farther in any direction. The divergence of the eye axis of dogs ranges from 12-25° depending on the breed.[101]

Experimentation has proven that dogs can distinguish between complex visual images such as that of a cube or a prism. Dogs also show attraction to static visual images such as the silhouette of a dog on a screen, their own reflections, or videos of dogs; however, their interest declines sharply once they are unable to make social contact with the image.[105]

Hearing

The frequency range of dog hearing is approximately 40 Hz to 60,000 Hz,[106] which means that dogs can detect sounds far beyond the upper limit of the human auditory spectrum.[98][106][107] In addition, dogs have ear mobility, which allows them to rapidly pinpoint the exact location of a sound.[108] Eighteen or more muscles can tilt, rotate, raise, or lower a dog’s ear. A dog can identify a sound’s location much faster than a human can, as well as hear sounds at four times the distance.[108]

Smell

The wet, textured nose of a dog

While the human brain is dominated by a large visual cortex, the dog brain is dominated by an olfactory cortex.[96] The olfactory bulb in dogs is roughly forty times bigger than the olfactory bulb in humans, relative to total brain size, with 125 to 220 million smell-sensitive receptors.[96] The bloodhound exceeds this standard with nearly 300 million receptors.[96] Subsequently, it has been estimated that dogs, in general, have an olfactory sense ranging from one hundred thousand to one million times more sensitive than a human’s. In some dog breeds, such as bloodhounds, the olfactory sense may be up to 100 million times greater than a human’s.[109] The wet nose is essential for determining the direction of the air current containing the smell. Cold receptors in the skin are sensitive to the cooling of the skin by evaporation of the moisture by air currents.[110]

Physical characteristics

Coat

The coats of domestic dogs are of two varieties: «double» being common with dogs (as well as wolves) originating from colder climates, made up of a coarse guard hair and a soft down hair, or «single», with the topcoat only.

Domestic dogs often display the remnants of countershading, a common natural camouflage pattern. A countershaded animal will have dark coloring on its upper surfaces and light coloring below,[111] which reduces its general visibility. Thus, many breeds will have an occasional «blaze», stripe, or «star» of white fur on their chest or underside.[112]

Tail

There are many different shapes for dog tails: straight, straight up, sickle, curled, or cork-screw. As with many canids, one of the primary functions of a dog’s tail is to communicate their emotional state, which can be important in getting along with others. In some hunting dogs, however, the tail is traditionally docked to avoid injuries.[113] In some breeds, puppies can be born with a short tail or no tail at all.[114]

Types and breeds

While all dogs are genetically very similar,[6] natural selection and selective breeding have reinforced certain characteristics in certain populations of dogs, giving rise to dog types and dog breeds. Dog types are broad categories based on function, genetics, or characteristics.[115] Dog breeds are groups of animals that possess a set of inherited characteristics that distinguishes them from other animals within the same species. Modern dog breeds are non-scientific classifications of dogs kept by modern kennel clubs. Purebred dogs of one breed are genetically distinguishable from purebred dogs of other breeds,[36] but the means by which kennel clubs classify dogs is unsystematic. Systematic analyses of the dog genome has revealed only four major types of dogs that can be said to be statistically distinct.[36] These include the «old world dogs» (e.g., Malamute and Shar Pei), «Mastiff»-type (e.g., English Mastiff), «herding»-type (e.g., Border Collie), and «all others» (also called «modern»- or «hunting»-type).[36][116]

Health

Dogs are susceptible to various diseases, ailments, and poisons, some of which can affect humans. To defend against many common diseases, dogs are often vaccinated.

A mixed-breed dog

Some breeds of dogs are prone to certain genetic ailments such as elbow or hip dysplasia, blindness, deafness, pulmonic stenosis, cleft palate, and trick knees. Two serious medical conditions particularly affecting dogs are pyometra, affecting unspayed females of all types and ages, and bloat, which affects the larger breeds or deep-chested dogs. Both of these are acute conditions, and can kill rapidly. Dogs are also susceptible to parasites such as fleas, ticks, and mites, as well as hookworm, tapeworm, roundworm, and heartworm.

Dogs are highly susceptible to theobromine poisoning, typically from ingestion of chocolate. Theobromine is toxic to dogs because, although the dog’s metabolism is capable of breaking down the chemical, the process is so slow that even small amounts of chocolate can be fatal, especially dark chocolate.

Dogs are also vulnerable to some of the same health conditions as humans, including diabetes, dental and heart disease, epilepsy, cancer, hypothyroidism, and arthritis.[117]

Mortality

Main article: Aging in dogs

The typical lifespan of dogs varies widely among breeds, but for most the median longevity, the age at which half the dogs in a population have died and half are still alive, ranges from 10 to 13 years.[118][119][120][121] Individual dogs may live well beyond the median of their breed.

The breed with the shortest lifespan (among breeds for which there is a questionnaire survey with a reasonable sample size) is the Dogue de Bordeaux, with a median longevity of about 5.2 years, but several breeds, including Miniature Bull Terriers, Bloodhounds, and Irish Wolfhounds are nearly as short-lived, with median longevities of 6 to 7 years.[121]

The longest-lived breeds, including Toy Poodles, Japanese Spitz, Border Terriers, and Tibetan Spaniels, have median longevities of 14 to 15 years.[121] The median longevity of mixed-breed dogs, taken as an average of all sizes, is one or more years longer than that of purebred dogs when all breeds are averaged.[119][120][121][122] The dog widely reported to be the longest-lived is «Bluey,» who died in 1939 and was claimed to be 29.5 years old at the time of his death; however, the Bluey record is anecdotal and unverified.[123] The longest verified records are of dogs living for 24 years.[123]

Predation

Although wild dogs, like wolves, are apex predators, they can be killed in territory disputes with wild animals.[124] Furthermore, in areas where both dogs and other large predators live, dogs can be a major food source for big cats or canines. Reports from Croatia indicate wolves kill more dogs more frequently than they kill sheep. Wolves in Russia apparently limit feral dog populations. In Wisconsin, more compensation has been paid for dog losses than livestock.[124] Some wolf pairs have been reported to prey on dogs by having one wolf lure the dog out into heavy brush where the second animal waits in ambush.[125] In some instances, wolves have displayed an uncharacteristic fearlessness of humans and buildings when attacking dogs, to the extent that they have to be beaten off or killed.[126] Coyotes and big cats have also been known to attack dogs. Leopards in particular are known to have a predilection for dogs, and have been recorded to kill and consume them regardless of the dog’s size or ferocity.[127] Tigers in Manchuria, Indochina, Indonesia, and Malaysia, are reputed to kill dogs with the same vigor as leopards.[128] Striped Hyenas are major predators of village dogs in Turkmenistan, India, and the Caucasus.[129] Reptiles such as alligators and pythons have been known to kill and eat dogs.

Diet

Despite their descent from wolves and classification as Carnivora, dogs are variously described in scholarly and other writings as carnivores[130][131] or omnivores.[3][132][133][134] Unlike obligate carnivores, such as the cat family with its shorter small intestine, dogs can adapt to a wide-ranging diet, and are not dependent on meat-specific protein nor a very high level of protein in order to fulfill their basic dietary requirements. Dogs will healthily digest a variety of foods, including vegetables and grains, and can consume a large proportion of these in their diet.[3]

A number of common human foods and household ingestibles are toxic to dogs, including chocolate solids (theobromine poisoning), onion and garlic (thiosulphate, sulfoxide or disulfide poisoning),[135] grapes and raisins, macadamia nuts, as well as various plants and other potentially ingested materials.[136][137]

Reproduction

Two dogs copulating on a beach

In domestic dogs, sexual maturity begins to happen around age six to twelve months for both males and females,[3][138] although this can be delayed until up to two years old for some large breeds. This is the time at which female dogs will have their first estrous cycle. They will experience subsequent estrous cycles biannually, during which the body prepares for pregnancy. At the peak of the cycle, females will come into estrus, being mentally and physically receptive to copulation.[3] Because the ova survive and are capable of being fertilized for a week after ovulation, it is possible for a female to mate with more than one male.[3]

Dogs bear their litters roughly 56 to 72 days after fertilization,[3][139] with an average of 63 days, although the length of gestation can vary. An average litter consists of about six puppies,[140] though this number may vary widely based on the breed of dog. In general, toy dogs produce from one to four puppies in each litter, while much larger breeds may average as many as twelve.

Some dog breeds have acquired traits through selective breeding that interfere with reproduction. Male French Bulldogs, for instance, are incapable of mounting the female. For many dogs of this breed, the female must be artificially inseminated in order to reproduce.[141]

Neutering

A feral dog from Sri Lanka nursing her four puppies

Neutering refers to the sterilization of animals, usually by removal of the male’s testicles or the female’s ovaries and uterus, in order to eliminate the ability to procreate and reduce sex drive. Because of the overpopulation of dogs in some countries, many animal control agencies, such as the American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (ASPCA), advise that dogs not intended for further breeding should be neutered, so that they do not have undesired puppies that may have to later be euthanized.[142]

According to the Humane Society of the United States, 3–4 million dogs and cats are put down each year in the United States and many more are confined to cages in shelters because there are many more animals than there are homes. Spaying or castrating dogs helps keep overpopulation down.[143] Local humane societies, SPCAs, and other animal protection organizations urge people to neuter their pets and to adopt animals from shelters instead of purchasing them.

Neutering reduces problems caused by hypersexuality, especially in male dogs.[144] Spayed female dogs are less likely to develop some forms of cancer, affecting mammary glands, ovaries, and other reproductive organs.[145] However, neutering increases the risk of urinary incontinence in female dogs,[146] and prostate cancer in males,[147] as well as osteosarcoma, hemangiosarcoma, cruciate ligament rupture, obesity, and diabetes mellitus in either gender.[148]

Intelligence and behavior

Intelligence

The Border Collie is considered to be one of the most intelligent breeds.

The domestic dog has a predisposition to exhibit a social intelligence that is uncommon in the animal world.[96] Dogs are capable of learning in a number of ways, such as through simple reinforcement (e.g., classical or operant conditioning) and by observation.[96]

Dogs go through a series of stages of cognitive development. As with humans, the understanding that objects not being actively perceived still remain in existence (called object permanence) is not present at birth. It develops as the young dog learns to interact intentionally with objects around it, at roughly 8 weeks of age.[96]

Puppies learn behaviors quickly by following examples set by experienced dogs.[96] This form of intelligence is not peculiar to those tasks dogs have been bred to perform, but can be generalized to myriad abstract problems. For example, Dachshund puppies that watched an experienced dog pull a cart by tugging on an attached piece of ribbon in order to get a reward from inside the cart learned the task fifteen times faster than those left to solve the problem on their own.[96][149] Dogs can also learn by mimicking human behaviors. In one study, puppies were presented with a box, and shown that, when a handler pressed a lever, a ball would roll out of the box. The handler then allowed the puppy to play with the ball, making it an intrinsic reward. The pups were then allowed to interact with the box. Roughly three-quarters of the puppies subsequently touched the lever, and over half successfully released the ball, compared to only 6% in a control group that did not watch the human manipulate the lever.[150] Another study found that handing an object between experimenters who then used the object’s name in a sentence successfully taught an observing dog each object’s name, allowing the dog to subsequently retrieve the item.[151]

Dogs also demonstrate sophisticated social cognition by associating behavioral cues with abstract meanings.[96] One such class of social cognition involves the understanding that others are conscious agents. Research has shown that dogs are capable of interpreting subtle social cues, and appear to recognize when a human or dog’s attention is focused on them. To test this, researchers devised a task in which a reward was hidden underneath one of two buckets. The experimenter then attempted to communicate with the dog to indicate the location of the reward by using a wide range of signals: tapping the bucket, pointing to the bucket, nodding to the bucket, or simply looking at the bucket.[152] The results showed that domestic dogs were better than chimpanzees, wolves, and human infants at this task, and even young puppies with limited exposure to humans performed well.[96]

Psychology research has shown that human faces are asymmetrical with the gaze instinctively moving to the right side of a face upon encountering other humans to obtain information about their emotions and state. Research at the University of Lincoln (2008) shows that dogs share this instinct when meeting a human being, and only when meeting a human being (i.e., not other animals or other dogs). As such they are the only non-primate species known to do so.[153][154]

Stanley Coren, an expert on dog psychology, states that these results demonstrated the social cognition of dogs can exceed that of even our closest genetic relatives, and that this capacity is a recent genetic acquisition that distinguishes the dog from its ancestor, the wolf.[96] Studies have also investigated whether dogs engaged in partnered play change their behavior depending on the attention-state of their partner.[155] Those studies showed that play signals were only sent when the dog was holding the attention of its partner. If the partner was distracted, the dog instead engaged in attention-getting behavior before sending a play signal.[155]

Coren has also argued that dogs demonstrate a sophisticated theory of mind by engaging in deception, which he supports with a number of anecdotes, including one example wherein a dog hid a stolen treat by sitting on it until the rightful owner of the treat left the room.[96] Although this could have been accidental, Coren suggests that the thief understood that the treat’s owner would be unable to find the treat if it were out of view. Together, the empirical data and anecdotal evidence points to dogs possessing at least a limited form of theory of mind.[96][155]

A study found a third of dogs suffered from anxiety when separated from others.[156]

A Border Collie named Chaser has learned the names for 1,022 toys after three years of training, so many that her trainers have had to mark the names of the objects lest they forget themselves. This is higher than Rico, another border collie who could remember at least 200 objects.[157]

Behavior

Main article: Dog behavior

Further information: Category:Dog training and behavior

Although dogs have been the subject of a great deal of behaviorist psychology (e.g. Pavlov’s dog), they do not enter the world with a psychological «blank slate».[96] Rather, dog behavior is affected by genetic factors as well as environmental factors.[96] Domestic dogs exhibit a number of behaviors and predispositions that were inherited from wolves.[96] The Gray Wolf is a social animal that has evolved a sophisticated means of communication and social structure. The domestic dog has inherited some of these predispositions, but many of the salient characteristics in dog behavior have been largely shaped by selective breeding by humans. Thus some of these characteristics, such as the dog’s highly developed social cognition, are found only in primitive forms in grey wolves.[152]

The existence and nature of personality traits in dogs have been studied (15329 dogs of 164 different breeds) and five consistent and stable «narrow traits» identified, described as playfulness, curiosity/fearlessness, chase-proneness, sociability and aggressiveness. A further higher order axis for shyness–boldness was also identified.[158][159]

Sleep

The average sleep time of a dog is said to be 10.1 hours per day.[160] Like humans, dogs have two main types of sleep: Slow-wave sleep, then Rapid Eye Movement sleep, the state in which dreams occur.[161]

Dog growl

A new study in Budapest, Hungary has found that dogs are able to tell how big another dog is just by listening to its growl. A specific growl is used by dogs to protect their food. The research also shows that dogs do not lie about their size, and this is the first time research has shown animals can determine another’s size by the sound it makes. The test used image of many kind of dogs and together showed a small and big dog and also a growl. The result, showed that 20 of the 24 test dogs looked at the image of the appropriate-sized dog first and looked at it longest.[162]

Differences from wolves

Some dogs, like this Tamaskan, look very much like wolves.

Physical characteristics

Further information: Wolves

Compared to equally sized wolves, dogs tend to have 20% smaller skulls, 30% smaller brains,[163] as well as proportionately smaller teeth than other canid species.[164] Dogs require fewer calories to function than wolves. It is thought by certain experts that the dog’s limp ears are a result of atrophy of the jaw muscles.[164] The skin of domestic dogs tends to be thicker than that of wolves, with some Inuit tribes favoring the former for use as clothing due to its greater resistance to wear and tear in harsh weather.[164]

Behavior

Dogs tend to be poorer than wolves at observational learning, being more responsive to instrumental conditioning.[164] Feral dogs show little of the complex social structure or dominance hierarchy present in wolf packs. For example, unlike wolves, the dominant alpha pairs of a feral dog pack do not force the other members to wait for their turn on a meal when scavenging off a dead ungulate as the whole family is free to join in. For dogs, other members of their kind are of no help in locating food items, and are more like competitors.[164] Feral dogs are primarily scavengers, with studies showing that unlike their wild cousins, they are poor ungulate hunters, having little impact on wildlife populations where they are sympatric. However, feral dogs have been reported to be effective hunters of reptiles in the Galápagos Islands,[165] and free ranging pet dogs are more prone to predatory behavior toward wild animals.

Domestic dogs can be monogamous.[166] Breeding in feral packs can be, but does not have to be restricted to a dominant alpha pair (such things also occur in wolf packs).[167] Male dogs are unusual among canids by the fact that they mostly seem to play no role in raising their puppies, and do not kill the young of other females to increase their own reproductive success.[165] Some sources say that dogs differ from wolves and most other large canid species by the fact that they do not regurgitate food for their young, nor the young of other dogs in the same territory.[164]

However, this difference was not observed in all domestic dogs. Regurgitating of food by the females for the young as well as care for the young by the males has been observed in domestic dogs, dingos as well as in other feral or semi-feral dogs. Regurgitating of food by the females and direct choosing of only one mate has been observed even in those semi-feral dogs of direct domestic dog ancestry. Also regurgitating of food by males has been observed in free-ranging domestic dogs.[166][168]

Trainability

This Labrador Retriever has been trained to woof and bark on command.

Dogs display much greater tractability than tame wolves, and are, in general, much more responsive to coercive techniques involving fear, aversive stimuli, and force than wolves, which are most responsive toward positive conditioning and rewards.[169] Unlike tame wolves, dogs tend to respond more to voice than hand signals.[170]

Mythology

In mythology, dogs often serve as pets or as watchdogs.[171]

In Greek mythology, Cerberus is a three-headed watchdog who guards the gates of Hades.[171] In Norse mythology, a bloody, four-eyed dog called Garmr guards Helheim.[171] In Persian mythology, two four-eyed dogs guard the Chinvat Bridge.[171] In Philippine mythology, Kimat who is the pet of Tadaklan, god of thunder, is responsible for lightning. In Welsh mythology, Annwn is guarded by Cŵn Annwn[171]

In Judaism and Islam, dogs are viewed as unclean scavengers.[171] In Christianity, dogs represent faithfulness.[171] In Asian countries such as China, Korea, and Japan, dogs are viewed as kind protectors.[171]

Gallery of dogs in art

|

|

|

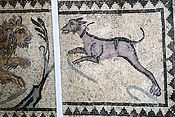

This Roman mosaic shows a large dog with a collar hunting a lion. |

|

|

|

William McElcheran’s Cross Section-dogs Dundas (TTC) Toronto |

|

|

|

A woodcut illustration from The history of four-footed beasts and serpents by Edward Topsell, 1658 |

See also

| Dogs portal |

- Argos (dog)

- Dog odor

- Dog king – Scandinavian tradition

- Dognapping

- Ethnocynology

- Hachikō Dog loyalty

- List of dog breeds

- List of dogs

- List of fictional dogs

- List of most popular dog breeds

- New Guinea Singing Dog

- Subspecies of Canis lupus

- Wolfdog

References

- ^ a b c «Mammal Species of the World — Browse: lupus». Bucknell.edu. http://www.bucknell.edu/MSW3/browse.asp?id=14000738. Retrieved 2010-08-10.

- ^ a b c «Mammal Species of the World — Browse: dingo». Bucknell.edu. http://www.bucknell.edu/MSW3/browse.asp?id=14000751. Retrieved 2010-08-10.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Dewey, T. and S. Bhagat. 2002. «Canis lupus familiaris», Animal Diversity Web. Retrieved 6 January 2009.

- ^ «Dog». Dictionary.com. http://dictionary.reference.com/browse/dog.

- ^ Definition of «bitch» at English Wiktionary

- ^ a b c d e f g h Savolainen P, Zhang YP, Luo J, Lundeberg J, Leitner T (November 2002). «Genetic evidence for an East Asian origin of domestic dogs». Science 298 (5598): 1610–3. Bibcode 2002Sci…298.1610S. doi:10.1126/science.1073906. PMID 12446907.

- ^ Coppinger, Ray (2001). Dogs: a Startling New Understanding of Canine Origin, Behavior and Evolution. New York: Scribner. p. 352. ISBN 0684855305.

- ^ Spady TC, Ostrander EA (January 2008). «Canine Behavioral Genetics: Pointing Out the Phenotypes and Herding up the Genes». American Journal of Human Genetics 82 (1): 10–8. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2007.12.001. PMC 2253978. PMID 18179880. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=2253978.

- ^ The Complete dog book: the photograph, history, and official standard of every breed admitted to AKC registration, and the selection, training, breeding, care, and feeding of pure-bred dogs. New York, N.Y: Howell Book House. 1992. ISBN 0-87605-464-5.[page needed]

- ^ Rasmussen, G. S. A. (April 1999). «Livestock predation by the painted hunting dog Lycaon pictus in a cattle ranching region of Zimbabwe: a case study». Biological Conservation 88 (1): 133–139. doi:10.1016/S0006-3207(98)00006-8.

- ^ «Domestic PetDog Classified By Linnaeus In 1758 As Canis Familiaris And Canis Familiarus Domesticus». www.encyclocentral.com. http://www.encyclocentral.com/23497-Domestic_Pet_Dog_Classified_By_Linnaeus_In_1758_As_Canis_Familiaris_And_Canis_Familiarus_Domesticus.html. Retrieved 18 June 2008.[dead link]

- ^ Seebold, Elmar (2002). Kluge. Etymologisches Wörterbuch der deutschen Sprache. Berlin/New York: Walter de Gruyter. p. 207. ISBN 3110174731.

- ^ «Dictionary of Etymology», Dictionary.com, s.v. «dog», encyclopedia.com retrieved on 27 May 2009.

- ^ Mallory, J. R. (1991). In search of the Indo-Europeans: language, archaeology and myth. London: Thames and Hudson. ISBN 0-500-27616-1.[page needed]

- ^ Broz, Vlatko (2008). «Diachronic Investigations of False Friends». Contemporary Linguistics (Suvremena lingvistika) 66 (2): 199–222. http://hrcak.srce.hr/index.php?show=clanak&id_clanak_jezik=48370&lang=en.

- ^ René Dirven; Marjolyn Verspoor (30 June 2004). Cognitive exploration of language and linguistics. John Benjamins Publishing Company. pp. 215–216. ISBN 9789027219060. http://books.google.com/?id=uZcs6poXkfEC.

- ^ «The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language: Fourth Edition». www.bartleby.com. Archived from the original on 18 October 2006. http://web.archive.org/web/20061018073726/http://www.bartleby.com/61/roots/IE259.html. Retrieved 30 November 2006.

- ^ Gould, Jean (1978). All about dog breeding for quality and soundness. London, Eng: Pelham. ISBN 0-7207-1064-2.[page needed]

- ^ Linnaeus, Carolus (1758). Systema naturae per regna tria naturae:secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis.. 1 (10th ed.). Holmiae (Laurentii Salvii). p. 38. http://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/page/726931. Retrieved 8 September 2008.

- ^ «ITIS Standard Report Page: Canis familiarus domesticus». Itis.gov. http://www.itis.gov/servlet/SingleRpt/SingleRpt?search_topic=TSN&search_value=727488. Retrieved 2010-12-21.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Miklosi, Adam (2007). Dog Behaviour, Evolution, and Cognition. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199295852.001.0001. ISBN 0-19-929585-9. http://books.google.com/?id=EUrXahLxUL8C.

- ^ Serpell, James (1995). The domestic dog: its evolution, behaviour, and interactions with people. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-42537-9.

- ^ N.A.. «ITIS Report: Canis lupus familiaris». ITIS Data. Integrated Taxonomic Information System. http://www.itis.gov/servlet/SingleRpt/SingleRpt?search_topic=TSN&search_value=726821. Retrieved 16 April 2010.

- ^ a b c Miklósi, Ádám. Dog, behavior, evolution, and cognition. Oxford Biology, 2009, pp. 95-136.

- ^ Miklósi, Ádám. Dog, behavior, evolution, and cognition. Oxford Biology, 2009, p. 104.

- ^ a b c Mark Derr (2004). A dogs history of America. North Point Press.

- ^ Lindblad-Toh K, Wade CM, Mikkelsen TS et al. (December 2005). «Genome sequence, comparative analysis and haplotype structure of the domestic dog». Nature 438 (7069): 803–19. Bibcode 2005Natur.438..803L. doi:10.1038/nature04338. PMID 16341006.

- ^ Fiennes, Alice; T-W-Fiennes, Richard N. (1968). The natural history of the dog. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson. ISBN 0-297-76455-1.[page needed]

- ^ a b McGourty, Christine (22 November 2002). «Origin of dogs traced». BBC News. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/science/nature/2498669.stm. Retrieved 29 November 2006.

- ^ «World’s first dog lived 31,700 years ago, ate big» msnbc 17 October 2008.

- ^ Davis, Simon J. M.; Valla, François R. (1978). «Evidence for domestication of the dog 12,000 years ago in the Natufian of Israel». Nature 276 (5688): 608–10. Bibcode 1978Natur.276..608D. doi:10.1038/276608a0.

- ^ Clarke Canfield, MSNBC Old dog, new tricks: Study IDs 9,400-year-old mutt [dead link], msnbc.com, January 19, 2010.

- ^ Vilà C, Savolainen P, Maldonado JE et al. (June 1997). «Multiple and ancient origins of the domestic dog». Science 276 (5319): 1687–9. doi:10.1126/science.276.5319.1687. PMID 9180076.

- ^ Miklosi 2007, p. 110

- ^ «Paleodb.org». Paleodb.org. 2009-01-04. http://paleodb.org/cgi-bin/bridge.pl?action=checkTaxonInfo&taxon_no=44854&is_real_user=1. Retrieved 2010-12-21.

- ^ a b c d e Parker HG, Kim LV, Sutter NB et al. (May 2004). «Genetic structure of the purebred domestic dog». Science 304 (5674): 1160–4. Bibcode 2004Sci…304.1160P. doi:10.1126/science.1097406. PMID 15155949.

- ^ Janice Koler-Matznick (2002). «The Origin of the Dog Revisited». Anthrozoos.

- ^ a b c Groves, Colin (1999). «The Advantages and Disadvantages of Being Domesticated». Perspectives in Human Biology 4: 1–12. ISSN 1038-5762.

- ^ a b c d e Tacon, Paul; Pardoe, Colin (2002). «Dogs make us human». Nature Australia 27 (4): 52–61.

- ^ Ruusila, Vesa; Pesonen, Mauri (August 2004). «Interspecific cooperation in human (Homo sapiens) hunting: the benefits of a barking dog (Canis familiaris)». Annales Zoologici Fennici 41 (4): 545–9. http://www.sekj.org/PDF/anzf41/anzf41-545.pdf.

- ^ Newby, Jonica (1997). The Pact for Survival. Sydney: ABC Books. ISBN 0733305814.[page needed]

- ^ a b Derr, Mark (1997). Dog’s Best Friend. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0226142809.

- ^ Franklin, A (2006). «Be[a]ware of the Dog: a post-humanist approach to housing». Housing Theory and Society 23 (3): 137–156. doi:10.1080/14036090600813760. ISSN 1403-6096.

- ^ Katz, Jon (2003). The New Work of Dogs. New York: Villard Books. ISBN 0-375-76055-5.

- ^ Haraway, Donna (2003). The Companion Species manifesto : Dogs, People and Significant Otherness. Chicago: Prickly Paradigm Press. ISBN 0-97175758-5.

- ^ a b c d e f Power, Emma (2008). «Furry Families: Making a Human-Dog Family through Home». Social and Cultural Geography 9 (5): 535–555. doi:10.1080/14649360802217790.

- ^ a b c Nast, Heidi J. (2006). «Loving … Whatever: Alienation, Neoliberalism and Pet-Love in the Twenty-First Century». ACME: an International E-Journal for Critical Geographies 5 (2): 300–327. ISSN 1492-9732.

- ^ «A Brief History of Dog Training». Dog Zone. 3 June 2007. http://www.dogzone.co.za/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=22%3Aa-brief-history-of-dog-training&catid=16%3Ageneral&Itemid=31. Retrieved 19 February 2010.

- ^ Jackson Schebetta, Lisa (2009). «Mythologies and Commodifications of Dominion in The Dog Whisperer with Cesar Millan». Journal for Critical Animal Studies (Institute for Critical Animal Studies) 7 (1): 107–131. ISSN 1948-352X.

- ^ Bradshaw, John; Blackwell, Emily J.; Casey, Rachel A. (2009). «Dominance in domestic dogs: useful construct or bad habit?». Journal of Veterinary Behavior (Elsevier) 4: 135–144. Archived from the original on 2010-08-27. http://www.webcitation.org/5sIbRXtwx.

- ^ Tannen, Deborah (2004). «Talking the Dog: Framing Pets as Interactional Resources in Family Discourse». Research on Language and Social Interaction 37 (4): 399–420. doi:10.1207/s15327973rlsi3704_1. ISSN 1532-7973.

- ^ «U.S. Pet Ownership Statistics». http://www.humanesociety.org/issues/pet_overpopulation/facts/pet_ownership_statistics.html. Retrieved 24 June 2010.

- ^ «The Story of Old Drum». Cedarcroft Farm Bed & Breakfast — Warrensburg, MO. http://www.almostheaven-golden-retriever-rescue.org/old-drum.html. Retrieved 29 November 2006.

- ^ Williams, Tully (2007). Working Sheep Dogs. Collingwood, Vic.: CSIRO Publishing. ISBN 0-643-09343-5.

- ^ Serpell, James (1995). «Origins of the dog: domestication and early history». The Domestic Dog. Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press. ISBN 0-521-41529-2.

- ^ «Psychiatric Service Dog Society». Psychdog.org. 2005-10-01. http://www.psychdog.org/attclinicians.html. Retrieved 2010-12-21.

- ^ «About Guide Dogs – Assistance Dogs International». Assistancedogsinternational.org. http://www.assistancedogsinternational.org/guide.php. Retrieved 2010-12-21.

- ^ Dalziel DJ, Uthman BM, Mcgorray SP, Reep RL (March 2003). «Seizure-alert dogs: a review and preliminary study». Seizure 12 (2): 115–20. doi:10.1016/S105913110200225X. PMID 12566236.

- ^ «German Shepherd Dog | American Kennel Club». American Kennel Club. http://www.akc.org/breeds/german_shepherd_dog/. Retrieved 2010-12-28.

- ^ «A Beginner’s Guide to Dog Shows». American Kennel Club. http://www.akc.org/events/conformation/beginners.cfm. Retrieved 30 October 2008.

- ^ Frederick J. Simoons (1994). Eat not this flesh: food avoidances from prehistory to the present (second ed.). University of Wisconsin Press. pp. 208–212. ISBN 978-0-299-14254-4. http://books.google.com/?id=JwGZTQunH00C.

- ^ How many dogs and cats are eaten in Asia?. Animalpeoplenews.org. September 2003.

- ^ South Korea’s dog day, BBC News, 17 August 1999.

- ^ Pettid, Michael J., Korean Cuisine: An Illustrated History, London: Reaktion Books Ltd., 2008, 25 ISBN 1-86189-348-5

- ^ Pettid, Michael J., Korean Cuisine: An Illustrated History, London: Reaktion Books Ltd., 2008, 84–85 ISBN 1-86189-348-5

- ^ Day, Matthew (2009-08-07). «Polish couple accused of making dog meat delicacy». Telegraph.co.uk. http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/europe/poland/5985367/Polish-couple-accused-of-making-dog-meat-delicacy.html. Retrieved 2010-12-21.

- ^ «Inside the cat and dog meat market in China». CNN. 9 March 2010. http://edition.cnn.com/2010/WORLD/asiapcf/03/09/china.animals/index.html. Retrieved 24 June 2010.

- ^ «Injury Prevention Bulletin». Northwest Terratories Health and Social Services. 25 March 2009. http://www.hlthss.gov.nt.ca/english/services/health_promotion/pdf/injury_prevention_bulletin.pdf. Retrieved 7 January 2010.

- ^ Bewley BR (September 1985). «Medical hazards from dogs». British Medical Journal 291 (6498): 760–1. doi:10.1136/bmj.291.6498.760. PMC 1417177. PMID 3929930. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=1417177.

- ^ Sun Huh, Sooung Lee. Toxocariasis =(20 August 2008). medscape.com.

- ^ a b «Toxocariasis». Kids Health. The Nemours Foundation. 2010. http://kidshealth.org/parent/infections/parasitic/toxocariasis.html. Retrieved 12 February 2010.

- ^ Johnson, Kate (May 2002). «Parasites in pet feces cause puzzling infections». Pediatric News. http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_hb4384/is_5_36/ai_n28919851. Retrieved 11 May 2009.

- ^ Chiodo, Paula; Basualdo, Juan; Ciarmela, Laura; Pezzani, Betina; Apezteguía, María; Minvielle, Marta (2006). «Related factors to human toxocariasis in a rural community of Argentina». Memórias do Instituto Oswaldo Cruz 101 (4): 397–400. doi:10.1590/S0074-02762006000400009.

- ^ A.H. Talaizadeh et.al. Human toxocariasis: A report of 3 cases. Pakistan Journal of Medical Sciences Quarterly, Volume 23 October – December 2007 (Part-I) Number 5.

- ^ «Dog fouling – Woking Borough Council». Woking.gov.uk. http://www.woking.gov.uk/planning/envhealthservice/dog/dogfouling. Retrieved 2010-12-21.

- ^ a b Grandin, Temple; Johnson, Catherine (2005). Animals in Translation. New York, New York: Scribner. pp. 131–132. ISBN 0743247698.

- ^ DVM360.com (1 July 2009). DVM Magazine.

- ^ Weiss HB, Friedman DI, Coben JH (January 1998). «Incidence of dog bite injuries treated in emergency departments». JAMA 279 (1): 51–3. doi:10.1001/jama.279.1.51. PMID 9424044.

- ^ Tierney DM, Strauss LP, Sanchez JL (February 2006). «Capnocytophaga canimorsus Mycotic Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm: Why the Mailman Is Afraid of Dogs». Journal of Clinical Microbiology 44 (2): 649–51. doi:10.1128/JCM.44.2.649-651.2006. PMC 1392675. PMID 16455937. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=1392675.

- ^ Mail campaign over dog attacks (11 August 2005). BBC News.

- ^ Podberscek, A.L. (2006). «Positive and Negative Aspects of Our Relationship with Companion Animals». Veterinary Research Communications 30 (1): 21–27. doi:10.1007/s11259-006-0005-0.

- ^ Headey B. (1999). «Health benefits and health cost savings due to pets: preliminary estimates from an Australian national survey». Social Indicators Research 47 (2): 233–243. doi:10.1023/A:1006892908532.

- ^ Serpell J (December 1991). «Beneficial effects of pet ownership on some aspects of human health and behaviour». Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine 84 (12): 717–20. PMC 1295517. PMID 1774745. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=1295517.

- ^ Friedmann E, Thomas SA (December 1995). «Pet ownership, social support, and one-year survival after acute myocardial infarction in the Cardiac Arrhythmia Suppression Trial (CAST)». The American Journal of Cardiology 76 (17): 1213–7. doi:10.1016/S0002-9149(99)80343-9. PMID 7502998.

- ^ Wilson CC (August 1991). «The pet as an anxiolytic intervention». The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 179 (8): 482–9. doi:10.1097/00005053-199108000-00006. PMID 1856711.

- ^ McNicholas, J.; Collis, G. M. (2006). «Animals as social supports: Insights for understanding animal assisted therapy». In Fine, Aubrey H.. Handbook on animal-assisted therapy: theoretical foundations and guidelines for practice. Amsterdam: Elsevier/Academic Press. pp. 49–71. ISBN 0-12-369484-1.

- ^ Eddy J, Hart LA, Boltz RP (January 1988). «The effects of service dogs on social acknowledgments of people in wheelchairs». The Journal of Psychology 122 (1): 39–45. PMID 2967371.

- ^ Kruger, K.A. & Serpell, J.A. (2006). Animal-assisted interventions in mental health: Definitions and theoretical foundations, In Fine, A.H. (Ed.), Handbook on animal-assisted therapy: Theoretical foundations and guidelines for practice. San Diego, CA, Academic Press: 21–38. ISBN 0123694841

- ^ Batson, K.; McCabe, B.; Baun, M.M.; Wilson, C. (1998). «The effect of a therapy dog on socialization and psychological indicators of stress in persons diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease». In Turner, Dennis C.; Wilson, Cindy C.. Companion animals in human health. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications. pp. 203–15. ISBN 978-0-7619-1061-9.

- ^ Katcher, A.H.; Wilkins, G.G. (2006). «The Centaur’s Lessons: Therapeutic education through care of animals and nature study». In Fine, Aubrey H.. Handbook on animal-assisted therapy: theoretical foundations and guidelines for practice. Amsterdam: Elsevier/Academic Press. pp. 153–77. ISBN 0-12-369484-1.