From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

The color wheel of love by John A. Lee

Ancient Greek philosophy differentiates main conceptual forms and distinct words for the Modern English word love: agápē, érōs, philía, philautía, storgē, and xenía.

List of concepts[edit]

Though there are more Greek words for love, variants and possibly subcategories, a general summary considering these Ancient Greek concepts is as follows:

- Agápe LOving is

(ἀγάπη, agápē[1]) means "love: esp. brotherly love, charity; the love of God for person and of person for God".[2] Agape is used in ancient texts to denote feelings for one's children and the feelings for a spouse, and it was also used to refer to a love feast.[3] Agape is used by Christians to express the unconditional love of God for His children.[4][non-primary source needed] This type of love was further explained by Thomas Aquinas as "to will the good of another".[5]

- Éros (ἔρως, érōs) means «love, mostly of the sexual passion».[6] The Modern Greek word «erotas» means «intimate love». Plato refined his own definition: Although eros is initially felt for a person, with contemplation it becomes an appreciation of the beauty within that person, or even becomes appreciation of beauty itself. Plato does not talk of physical attraction as a necessary part of love, hence the use of the word platonic to mean «without physical attraction». In the Symposium, an ancient work on the subject, Plato has Socrates argue that eros helps the soul recall knowledge of beauty and hehe

contributes to an understanding of spiritual truth, the ideal form of youthful beauty that leads us humans to feel erotic desire – thus suggesting that even that sensually based love aspires to the non-corporeal, spiritual plane of existence; that is, finding its truth, just like finding any truth, leads to transcendence.[7] Lovers and philosophers are all inspired to seek truth through the means of eros.

- Philia (φιλία, philía) means «affectionate regard, friendship», usually «between equals».[8] It is a dispassionate virtuous love, a concept developed by Aristotle.[9] In his best-known work on ethics, Nicomachean Ethics, philia is expressed variously as loyalty to friends (specifically, «brotherly love»), family, and community, and requires virtue, equality, and familiarity. Furthermore, in the same text philos is also the root of philautia denoting self-love and arising from it, a general type of love, used for love between family, between friends, a desire or enjoyment of an activity, as well as between lovers.

- Storge (στοργή, storgē) means «love, affection» and «especially of parents and children».[10] It is the common or natural empathy, like that felt by parents for offspring.[11] Rarely used in ancient works, and then almost exclusively as a descriptor of relationships within the family. It is also known to express mere acceptance or putting up with situations, as in «loving» the tyrant. This is also used when referencing the love for one’s country or a favorite sports team.

- Philautia (φιλαυτία, philautía) means «self-love». To love oneself or «regard for one’s own happiness or advantage»[12][full citation needed] has been conceptualized both as a basic human necessity[13] and as a moral flaw, akin to vanity and selfishness,[14] synonymous with amour-propre or egotism. The Greeks further divided this love into positive and negative: one, the unhealthy version, is the self-obsessed love, and the other is the concept of self-compassion.

- Xenia (ξενία, xenía) is an ancient Greek concept of hospitality. It is sometimes translated as «guest-friendship» or «ritualized friendship». It is an institutionalized relationship rooted in generosity, gift exchange, and reciprocity.[15] Historically, hospitality towards foreigners and guests (Hellenes not of your polis) was understood as a moral obligation. Hospitality towards foreign Hellenes honored Zeus Xenios (and Athene Xenia) patrons of foreigners.

See also[edit]

- Color wheel theory of love

- Diotima of Mantinea

- The Four Loves by C. S. Lewis

- Greek love

- Intellectual virtue – Greek words for knowledge

- Love

- Restoration of Peter

- Sapphic love

References[edit]

- ^ Liddell, Henry George; Scott, Robert (eds.). «ἀγάπη». A Greek-English Lexicon. Perseus. Tufts University.

- ^ Liddell, H. G.; Scott, Robert (October 2010). An Intermediate Greek-English Lexicon: Founded upon the seventh edition of Liddell and Scott’s Greek-English Lexicon. Benediction Classics. p. 4. ISBN 978-1-84902-626-0.

- ^ «Greek Lexicon». GreekBible.com. The Online Greek Bible. Retrieved 24 August 2014.

- ^ Romans 5:5, 5:8

- ^ «St. Thomas Aquinas, STh I-II, 26, 4, corp. art». Newadvent.org. Retrieved 2010-10-30.

- ^ ἔρως, Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon, on Perseus

- ^ Plato (1973). The Symposium. Translated by Walter Hamilton (Repr. ed.). Harmondsworth, Eng.: Penguin. ISBN 9780140440249.

- ^ φιλία, Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon, on Perseus.

- ^ Alexander Moseley. «Philosophy of Love (Philia)». Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved 24 August 2014.

- ^ στοργή, Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon, on Perseus.

- ^ Strong B., Yarber W. L., Sayad B. W., Devault C. (2008). Human sexuality: diversity in contemporary America (6th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill. p. 228. ISBN 978-0-07-312911-2.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link) - ^ Merriam-Webster dictionary.[verification needed].

- ^ See Maslow’s hierarchy of needs.

- ^ B. Kirkpatrick ed., Roget’s Thesaurus (1998) p. 592, 639.

- ^ The Greek world. Anton Powell. London: Routledge. 1995. ISBN 0-203-04216-6. OCLC 52295939.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link)

Sources[edit]

- «English-to-Greek». Perseus.

word search results for love

- «Definitions [of love]» (PDF). mbcarlington.com. Greek word study on Love. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-11-27.

One of the best feelings in the world, without question, is LOVE.

We use the word “love” in many different contexts- the love for our parents, best friend, romantic partner, grandparent, sibling, job, car, etc.

The Ancient Greeks had eight words that corresponded to different types of love:

Eros (romantic, passionate love)

The first kind of love is Eros, named after the Greek God of fertility.

Eros is passion, lust and pleasure.

The ancient Greeks considered Eros to be dangerous and frightening as it involves a “loss of control” through the primal impulse to procreate. Eros is an intense form of love that arouses romantic and sexual feelings.

Philia (affectionate love)

The second type of love is Philia, or friendship.

Plato felt that physical attraction was not a necessary part of love, hence the use of the word platonic to mean, “without physical attraction.”

Agape (selfless, universal love)

The third is Agape, selfless universal love, such as the love for strangers, nature, or God.

This love is unconditional, bigger than ourselves, a boundless compassion and an infinite empathy that you extended to everyone, whether they are family members or distant strangers.

Storge (familiar love)

Storge is a natural form of affection experienced between family members.

This protective, kinship-based love is common between parents and their children, and children for their parents.

Storge can also describe a sense of patriotism toward a country or allegiance to the same team.

Mania (obsessive love)

When love turns to obsession, it becomes mania.

Stalking behaviors, co-dependency, extreme jealousy, and violence are all symptoms of Mania.

Ludus (playful love)

The Ancient Greeks thought of ludus as a playful form of love.

It describes the situation of having a crush and acting on it, or the affection between young lovers.

Pragma (enduring love)

Pragma is a love built on commitment, understanding and long-term best interests.

It is a love that has aged, matured and about making compromises to help the relationship work over time, also showing patience and tolerance.

Philautia (self love)

The Greeks understood that in order to care for others, we must first learn to care for ourselves.

As Aristotle said “All friendly feelings for others are an extension of a man’s feelings for himself.”

*And here is one of our favourite romantic songs to celebrate Valentine’s Day:

*More on GCT: Ancient Greek Statues unearthed near Athens Airport

In Christianity, agapē is associated with the unconditional love of Jesus Christ, depicted here in his Sacred Heart form.

Agapē (αγάπη in Greek) is one of several Greek words translated into English as love. Greek writers at the time of Plato and other ancient authors used forms of the word to denote love of a spouse or family, or affection for a particular activity, in contrast to, if not with a totally separate meaning from, philia (an affection that could denote either brotherhood or generally non-sexual affection) and eros (an affection of a sexual nature, usually between two unequal partners, although Plato’s notion of eros as love for beauty is not necessarily sexual). The term agape with that meaning was rarely used in ancient manuscripts, but quite extensively used in the Septuagint, the Koine Greek translation of the Hebrew Bible.

In the New Testament, however, agape was frequently used to mean something more distinctive: the unconditional, self-sacrificing, and volitional love of God for humans through Jesus, which they ought also to reciprocate by practicing agape love towards God and among themselves. The term agape has been expounded on by many Christian writers in a specifically Christian context. In early Christianity, agape also signified a type of eucharistic feast shared by members of the community.

The Latin translation of agape in the Vulgate is usually caritas, which in older Bibles is sometimes translated «charity.» St. Augustine believed caritas to contain not only agape but also eros, because he thought it includes the human desire to be like God. The Swedish Lutheran theologian Anders Nygren critiqued the Augustinian theory, sharply distinguishing between agape (unmotivated by the object) and eros (motivated and evoked by the object) and regarding agape as the only purely Christian kind of love. Yet Nygren’s theory has been criticized as having an excessively narrow understanding of agape that is unable to appreciate the relational nature of divine love, as it is often so portrayed in the Bible.

Greek Words for Love

‘Sacred Love versus Profane Love’ by Giovanni Baglione

Ancient Greek distinguishes a number of words for love, of which three are most prominent: eros, philia, and agape. As with other languages, it has been historically difficult to separate the meanings of these words totally. However, the senses in which these words were generally used are given below:

- Eros (ἔρως érōs) is passionate love and attraction including sensual desire and longing. It is love more intimate than the philia love of friendship. The modern Greek word «erotas» means «romantic love,» and the ancient Greek word eros, too, applies to dating relationships and marriage. The word eros with the meaning of sexual love appears one time (Proverbs 7:18) in the Septuagint, the Greek translation of the Hebrew Bible, but it is absent in the Koine Greek text of the New Testament. Eros in ancient Greek is not always sexual in nature, however. For Plato, while eros is initially felt for a person, with contemplation it becomes an appreciation of the beauty within that person, or even an appreciation of beauty itself. It should be noted that Plato does not talk of physical attraction as a necessary part of love, hence the use of the word platonic to mean, «without physical attraction.» The most famous ancient work on the subject of eros is Plato’s Symposium, which is a discussion among the students of Socrates on the nature of eros.[1] Plato says eros helps the soul recall knowledge of beauty, and contributes to an understanding of spiritual truth. Lovers and philosophers are all inspired to seek truth by eros.

- Philia (φιλία philía) means friendship and dispassionate virtuous love. It includes loyalty to friends, family, and community, and requires virtue, equality and familiarity. In ancient texts, philia denotes a general type of love, used for love between friends, and family members, as well as between lovers. This, in its verb or adjective form (i.e., phileo or philos), is the only other word for «love» used in the New Testament besides agape, but even then it is used substantially less frequently.

- Agape (ἀγάπη agápē) refers to a general affection of «love» rather than the attraction suggested by eros; it is used in ancient texts to denote feelings for a good meal, one’s children, and one’s spouse. It can be described as the feeling of being content or holding one in high regard. This broad meaning of agape or its verb agapao can be seen extensively in the Septuagint as the Greek translation of the common Hebrew term for love (aḥaba), which denotes not only God’s love for humanity but also one’s affection for one’s spouse and children, brotherly love, and even sexual desire. It is uncertain why agape was chosen, but the similarity of consonant sounds (aḥaba) may have played a part. This usage provides the context for the choice of this otherwise still quite obscure word, in preference to other more common Greek words, as the most frequently used word for love in the New Testament. But, when it is used in the New Testament, its meaning becomes more focused, mainly referring to unconditional, self-sacrificing, giving love to all—both friend and enemy.

Additionally, modern Greek contains two other words for love:

- Storge (στοργή storgē) means «affection»; it is natural affection, like that felt by parents for offspring. The word was rarely used in ancient works, and almost exclusively as a descriptor of relationships within the family.

- Thelema (θέλημα) means «desire»; it is the desire to do something, to be occupied, to be in prominence.

Agape in Christianity

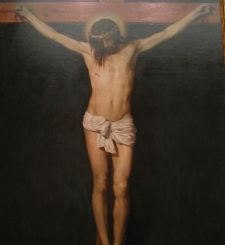

The Crucifixion of Jesus is seen as an example of agape (self-sacrificing love). Diego Velázquez, seventeenth century

New Testament

In the New Testament, the word agape or its verb form agapao appears more than 200 times. It is used to describe:

- God’s love for human beings: «God so loved the world that he gave his one and only Son (John 3:16); «God demonstrates his own love for us in this: While we were still sinners, Christ died for us (Romans 5:8); «God is love» (1 John 4:8).

- Jesus’ love for human beings: «Christ loved us and gave himself up for us as a fragrant offering and sacrifice to God (Ephesians 5:2).

- What our love for God should be like: «Love the Lord your God with all your heart and with all your soul and with all your mind» (Matthew 22:37).

- What our love for one another as human beings should be like: «Love your neighbor as yourself» (Matthew 22:39); «Love each other as I have loved you» (John 15:12); «Love does no harm to its neighbor. Therefore love is the fulfillment of the law» (Romans 13:10).

Agape in the New Testament is a form of love that is voluntarily self-sacrificial and gratuitous, and its origin is God. Its character is best described in the following two passages:

Love your enemies, do good to those who hate you, bless those who curse you, pray for those who mistreat you. If someone strikes you on one cheek, turn to him the other also. If someone takes your cloak, do not stop him from taking your tunic. Give to everyone who asks you, and if anyone takes what belongs to you, do not demand it back. Do to others as you would have them do to you. If you love those who love you, what credit is that to you? Even ‘sinners’ love those who love them. And if you do good to those who are good to you, what credit is that to you? Even ‘sinners’ do that. And if you lend to those from whom you expect repayment, what credit is that to you? Even ‘sinners’ lend to ‘sinners,’ expecting to be repaid in full. But love your enemies, do good to them, and lend to them without expecting to get anything back. Then your reward will be great, and you will be sons of the Most High, because he is kind to the ungrateful and wicked. Be merciful, just as your Father is merciful (Luke 6:27-36).

If I speak in the tongues of men and of angels, but have not love, I am only a resounding gong or a clanging cymbal. If I have the gift of prophecy and can fathom all mysteries and all knowledge, and if I have a faith that can move mountains, but have not love, I am nothing. If I give all I possess to the poor and surrender my body to the flames, but have not love, I gain nothing. Love is patient, love is kind. It does not envy, it does not boast, it is not proud. It is not rude, it is not self-seeking, it is not easily angered, it keeps no record of wrongs. Love does not delight in evil but rejoices with the truth. It always protects, always trusts, always hopes, always perseveres (1 Corinthians 13:1-7).

However, the verb agapao is at times used also in a negative sense, where it retains its more general meaning of «affection» rather than unconditional love or divine love. Such examples include: «for Demas, because he loved (agapao) this world, has deserted me and has gone to Thessalonica (2 Timothy 4:10); «for they loved (agapao) praise from men more than praise from God (John 12:43); and «Light has come into the world, but men loved (agapao) darkness instead of light because their deeds were evil (John 3:19).

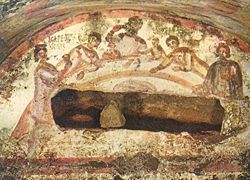

Fresco of a female figure holding a chalice at an early Christian Agape feast. Catacomb of Saints Marcellinus and Peter, Via Labicana, Rome

Agape as a meal

The word agape in its plural form is used in the New Testament to describe a meal or feast eaten by early Christians, as in Jude 1:12, 2 Peter 2:13, and 1 Corinthians 11:17-34. The agape meal was either related to the Eucharist or another term used for the Eucharist.[2] It eventually fell into disuse.

Later Christian development

Because of the frequent use of the word agape in the New Testament, Christian writers have developed a significant amount of theology based solely on the interpretation of it.

The Latin translation of agape is usually caritas in the Vulgate and amongst Catholic theologians such as St. Augustine. Hence the original meaning of «charity» in English. The King James Version uses «charity» as well as «love» to translate the idea of agape or caritas. When Augustine used the word caritas, however, he meant by it more than self-sacrificial and gratuitous love because he included in it also the human desire to be like God in a Platonic way. For him, therefore, caritas is neither purely agape nor purely eros but a synthesis of both.

The twentieth-century Swedish Lutheran theologian Anders Nygren made a sharp distinction between agape and eros, saying that the former indicates God’s unmerited descent to humans, whereas the latter shows humans’ ascent to God. According to Nygren, agape and eros have nothing to do with each other, belonging to two entirely separate realms. The former is divine love that creates and bestows value even on the unlovable object, whereas the latter is pagan love that seeks its own fulfillment from any value in the object. The former, being altruistic, is the center of Christianity, whereas the latter is egocentric and non-Christian. Based on this, Nygren critiqued Augustine’s notion of caritas, arguing that it is an illegitimate synthesis of eros and agape, distorting the pure, Christian love that is agape. Again, according to Nygren, agape is spontaneous, unmotivated by the value of (or its absence in) the object, creative of value in the object, and initiative of God’s fellowship, whereas eros is motivated and evoked by the quality, value, beauty, or worth of the object. Nygren’s observation is that agape in its pure form was rehabilitated through Martin Luther’s Protestant Reformation.[3]

In 2006, Pope Benedict XVI in his first encyclical, Deus Caritas Est, addressed this issue, saying that eros and agape are both inherently good as two separable halves of complete love that is caritas, although eros may risk degrading to mere sex without a spiritual support. It means that complete love involves the dynamism between the love of giving and the love of receiving.[4]

Criticisms of Nygren

Nygren’s sharp distinction of agape and eros has been criticized by many. Daniel Day Williams, for example, has critiqued Nygren, referring to the New Testament passage: «Blessed are those who hunger and thirst for righteousness, for they will be filled» (Matthew 5:6). This passage, according to Williams, shows that the two types of love are related to each other in that God’s agape can be given to those who strive for righteousness in their love of eros for it, and that Nygren’s contrasting categorizations of agape as absolutely unconditional and of eros as an egocentric desire for fellowship with God do not work.[5] How can our desire for fellowship with God be so egocentric as not to be able to deserve God’s grace?

Another way of relating agape to eros has been suggested by process theologians. According to them, the ultimate purpose of agape is to help create value in the object so that the subject may be able to eventually appreciate and enjoy it through eros. When God decides to unconditionally love us in his attempt to save us, doesn’t he at the same time seek to see our salvation eventually? This aspect of God’s love which seeks the value of beauty in the world is called «Eros» by Alfred North Whitehead, who defines it as «the living urge towards all possibilities, claiming the goodness of their realization.»[6] One significant corollary in this more comprehensive understanding of love is that when the object somehow fails to build value in response, the subject suffers. Hence, process theologians talk about the suffering of God, and argue that it is an important biblical theme especially in the Hebrew Bible that records that God suffered as a «God in Search of Man»—a phrase which is the title of a book written by the Jewish theologian Abraham Joshua Heschel.[7]

It seems, therefore, that agape and eros, while distinguishable from each other, are closely connected. Love, as understood this way, applies not only to the mutual relationship between God and humans but also to the reciprocal relationship among humans. It can be recalled that ancient Greek did not share the modern tendency to sharply differentiate between the various terms for love such as agape and eros.

Notes

- ↑ Plato, The Symposium, tr. Christopher Gill (Penguin Classics, 2003).

- ↑ J. F. Keating. The Agape and the Eucharist in the Early Church: Studies in the History of the Christian Love-Feasts. (Kessinger Publishing, LLC, 2007).

- ↑ Anders Nygren. Agape and Eros (Westminster Press, 1953).

- ↑ Deus Caritas Est..Vatican Library. Retrieved April 30, 2008.

- ↑ Daniel Day Williams. God’s Grace and Man’s Hope: An Interpretation of the Christian Life in History. (Harper & Row, 1965).

- ↑ Alfred North Whitehead. Adventures of Ideas. (Cambridge University Press, 1933), 381.

- ↑ Abraham Joshua Heschel. God in Search of Man: A Philosophy of Judaism. (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1976).

References

ISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Heschel, Abraham Joshua. God in Search of Man: A Philosophy of Judaism. Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1976. ISBN 0374513317

- Keating, J. F. The Agape and the Eucharist in the Early Church: Studies in the History of the Christian Love-Feasts. Kessinger Publishing, LLC, 2007. ISBN 9780548287699

- Lewis, C. S. The Four Loves. Fount, 2002. ISBN 0006280897

- Nygren, Anders. Agape and Eros. Westminster Press, 1953.

- Outka, Gene. Agape: An Ethical Analysis (Yale Publications in Religion). New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1977. ISBN 9780300021226

- Plato. The Symposium, Translated by Christopher Gill. Penguin Classics, 2003. ISBN 9780140449273

- Soble, Alan. Eros, Agape and Philia: Readings in the Philosophy of Love. St. Paul, MN: Paragon House Publishers, 1999. ISBN 9781557782786

- Vacek, Edward Collins. Love, Human and Divine: The Heart of Christian Ethics (Moral Traditions). Georgetown University Press; New Ed edition, 1996. ISBN 9780878406272

- Whitehead, Alfred North. Adventures of Ideas. Cambridge University Press, 1933.

- Williams, Daniel Day. God’s Grace and Man’s Hope: An Interpretation of the Christian Life in History. Harper & Row, 1965.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article

in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

- Agape history

- Greek_words_for_love history

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

- History of «Agape»

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

A Greek sculpture from the fourth century B.C. / Photo by Tilemahos Efthimiadis / Flickr.

Looking for an antidote to modern culture’s emphasis on romantic love? Perhaps we can learn from the diverse forms of emotional attachment prized by the ancient Greeks.

By Robert Krznaric / 12.27.2013

Today’s coffee culture has an incredibly sophisticated vocabulary. Do you want a cappuccino, an espresso, a skinny latte, or maybe an iced caramel macchiato?

The ancient Greeks were just as sophisticated in the way they talked about love, recognizing six different varieties. They would have been shocked by our crudeness in using a single word both to whisper “l love you” over a candlelit meal and to casually sign an email “lots of love.”

So what were the six loves known to the Greeks? And how can they inspire us to move beyond our current addiction to romantic love, which has 94 percent of young people hoping—but often failing—to find a unique soul mate who can satisfy all their emotional needs?

1. Eros, or sexual passion

The first kind of love was eros, named after the Greek god of fertility, and it represented the idea of sexual passion and desire. But the Greeks didn’t always think of it as something positive, as we tend to do today. In fact, eros was viewed as a dangerous, fiery, and irrational form of love that could take hold of you and possess you—an attitude shared by many later spiritual thinkers, such as the Christian writer C.S. Lewis.

Eros involved a loss of control that frightened the Greeks. Which is odd, because losing control is precisely what many people now seek in a relationship. Don’t we all hope to fall “madly” in love?

2. Philia, or deep friendship

The second variety of love was philia or friendship, which the Greeks valued far more than the base sexuality of eros. Philia concerned the deep comradely friendship that developed between brothers in arms who had fought side by side on the battlefield. It was about showing loyalty to your friends, sacrificing for them, as well as sharing your emotions with them. (Another kind of philia, sometimes called storge, embodied the love between parents and their children.)

We can all ask ourselves how much of this comradely philia we have in our lives. It’s an important question in an age when we attempt to amass “friends” on Facebook or “followers” on Twitter—achievements that would have hardly impressed the Greeks.

3. Ludus, or playful love

This was the Greeks’ idea of playful love, which referred to the affection between children or young lovers. We’ve all had a taste of it in the flirting and teasing in the early stages of a relationship. But we also live out our ludus when we sit around in a bar bantering and laughing with friends, or when we go out dancing.

Dancing with strangers may be the ultimate ludic activity, almost a playful substitute for sex itself. Social norms may frown on this kind of adult frivolity, but a little more ludus might be just what we need to spice up our love lives.

4. Agape, or love for everyone

The fourth love, and perhaps the most radical, was agape or selfless love. This was a love that you extended to all people, whether family members or distant strangers. Agape was later translated into Latin as caritas, which is the origin of our word “charity.”

C.S. Lewis referred to it as “gift love,” the highest form of Christian love. But it also appears in other religious traditions, such as the idea of mettā or “universal loving kindness” in Theravāda Buddhism.

There is growing evidence that agape is in a dangerous decline in many countries. Empathy levels in the U.S. have declined sharply over the past 40 years, with the steepest fall occurring in the past decade. We urgently need to revive our capacity to care about strangers.

5. Pragma, or longstanding love

Another Greek love was the mature love known as pragma. This was the deep understanding that developed between long-married couples.

Pragma was about making compromises to help the relationship work over time, and showing patience and tolerance.

The psychoanalyst Erich Fromm said that we expend too much energy on “falling in love” and need to learn more how to “stand in love.” Pragma is precisely about standing in love—making an effort to give love rather than just receive it. With about a third of first marriages in the U.S. ending through divorce or separation in the first 10 years, the Greeks would surely think we should bring a serious dose of pragma into our relationships.

6. Philautia, or love of the self

The Greek’s sixth variety of love was philautia or self-love. And the clever Greeks realized there were two types. One was an unhealthy variety associated with narcissism, where you became self-obsessed and focused on personal fame and fortune. A healthier version enhanced your wider capacity to love.

The idea was that if you like yourself and feel secure in yourself, you will have plenty of love to give others (as is reflected in the Buddhist-inspired concept of “self-compassion”). Or, as Aristotle put it, “All friendly feelings for others are an extension of a man’s feelings for himself.”

The ancient Greeks found diverse kinds of love in relationships with a wide range of people—friends, family, spouses, strangers, and even themselves. This contrasts with our typical focus on a single romantic relationship, where we hope to find all the different loves wrapped into a single person or soul mate. The message from the Greeks is to nurture the varieties of love and tap into its many sources. Don’t just seek eros, but cultivate philia by spending more time with old friends, or develop ludus by dancing the night away.

Moreover, we should abandon our obsession with perfection. Don’t expect your partner to offer you all the varieties of love, all of the time (with the danger that you may toss aside a partner who fails to live up to your desires). Recognize that a relationship may begin with plenty of eros and ludus, then evolve toward embodying more pragma or agape.

The diverse Greek system of loves can also provide consolation. By mapping out the extent to which all six loves are present in your life, you might discover you’ve got a lot more love than you had ever imagined—even if you feel an absence of a physical lover.

It’s time we introduced the six varieties of Greek love into our everyday way of speaking and thinking. If the art of coffee deserves its own sophisticated vocabulary, then why not the art of love?

Comments

comments

amor : love, affection, infatuation, passion.

What is the most beautiful Latin word?

Is Amor Latin?

From Latin amor (“love”), amōrem.

What is the coolest Latin word?

What is soulmate in Latin?

GLOSSARY ENTRY (DERIVED FROM QUESTION BELOW) English term or phrase: soulmate. Latin translation: comes animae.

What is love called in Arabic?

‘Habibi/ti’ (ha-beeb-i/ti) / my love. ‘Habibi’ (‘habibti’ for girls) derives from the word ‘hubb’, meaning love. It literally translates to ‘my love’, and can be used in formal and informal contexts, often in songs or when referring to a partner.

What is pure in Latin?

The Latin word purus, “clean or unmixed,” is the root of pure. Definitions of pure.

What does Omnia mean?

: prepared in all things : ready for anything. See the full definition.

What is Sunshine Latin?

Latin translation: lux solaris “Light” or “shine” is “lux”. You can they either use a genitive “lux solis = light/shine of the sun” or an adjective “lux solaris = sunlight/shine”.

What are the Greek words for love?

What are the 3 words for love in Greek?

Eros – Philia – Agape: The Three Greek Words For LOVE.

How do you say love in ancient Rome?

te amo = “I love you” amorem amamus = “We love love”

What did Romans call their lovers?

As was mentioned above, spouses and lovers generally call each other by cognomen rather than praenomen. Occasionally they called each other vir (husband) and uxor (wife), but more commonly they used terms of endearment (see below).

What is Hebrew word for love?

What are 12 love types?

What are the 7 types of love?

What is love? People have had a hard time answering that question for a lot longer than you might think. In Ancient Greece, love was a concept pondered over by some of history’s most famous philosophers, including Plato and Aristotle. Greek philosophers attempted to explain love rationally and often categorized the different kinds of love people could feel. Because we love them so much, we brought together some Greek words—and a Latin one, for good measure—for the different kinds of love you might find out there.

eros

Original Greek: ἔρως (érōs)

Eros is physical love or sexual desire. Eros is the type of love that involves passion, lust, and/or romance.

Examples of eros would be the love felt between, well, lovers. Eros is the sensual love between people who are sexually attracted to each other. In the Bible, eros was synonymous with “marital love” because husbands and wives were supposed to be the only people having sex. Eros was also the name of a love god in Greek mythology—better known by his Roman name, Cupid—and was the guy responsible for shooting magic arrows at people to make them fall in love.

The word eros is still used in psychology today to refer to sexual desire or the libido. The words erotic and erogenous, which both have to do with sexual desire or arousal, are derived from eros.

Why do we express our love through valentines?

philia

Original Greek: ϕιλία (philía)

Philia is affectionate love. Philia is the type of love that involves friendship.

Philia is the kind of love that strong friends feel toward each other. However, it doesn’t stop there. The Greek philosopher Plato thought that philia was an even greater love than eros and that the strongest loving relationships were ones where philia led to eros: a “friends become lovers” situation. Our concept of platonic love—love that isn’t based on physical attraction—comes from this Platonic philosophy.

The word philia is related to the word philosophy through the combining form philo-. Philia itself is the source of the combining forms -philia, -phile, and -phily, all three of which are used to indicate a figurative love or affinity for something.

agape

Original Greek: ἀγάπη (agápē)

Agape is often defined as unconditional, sacrificial love. Agape is the kind of love that is felt by a person willing to do anything for another, including sacrificing themselves, without expecting anything in return. Philosophically, agape has also been defined as the selfless love that a person feels for strangers and humanity as a whole. Agape is the love that allows heroic people to sacrifice themselves to save strangers they have never met.

❤️Did you know … ?

Agape is a major term in the Christian Bible, which is why it is often defined as “Christian love.” In the New Testament, agape is the word used to describe the love that God has for humanity and the love humanity has for God. Agape was also the love that Jesus Christ felt for humanity, which explains why he was willing to sacrifice himself.

storge

Original Greek: στοργή (storgé)

Storge is familial love. Storge is the natural love that family members have for one another.

Of all of the types of love, storge might be the easiest to understand. It is the type of love that parents feel toward their children and vice versa. Storge also describes the love that siblings feel towards each other, and the love felt by even more distant kin relationships, such as a grandparent for a grandchild or an uncle toward a niece.

mania

Original Greek: μανία (manía)

Mania is obsessive love. Mania is the kind of “love” that a stalker feels toward their victim.

As a type of love, mania is not good, and the Greeks knew this as well as we do. Mania is excessive love that reaches the point of obsession or madness. Mania describes what a jilted lover feels when they are extremely jealous of a rival or the unhealthy obsession that can result from mental illness.

The Greek mania is the source of the English word mania and similar words like maniac and manic. It is also the source of the combining form -mania, which is often used in words that refer to obsessive behavior such as pyromania and egomania.

ludus

Original Latin: Bucking the trend, the word ludus comes from Latin rather than Greek. In Latin, lūdus means “game” or “play,” which fits with the type of love it refers to. One possible Greek equivalent is the word ερωτοτροπία, meaning “courtship.”

Ludus is playful, noncommittal love. Ludus covers things like flirting, seduction, and casual sex.

Ludus means “play” or “game” in Latin, and that pretty much explains what ludus is: love as a game. When it comes to ludus, a person is not looking for a committed relationship. People who are after ludus are just looking to have fun or view sex as a prize to be won. A “friends with benefits” situation would be an example of a relationship built on ludus: neither partner is interested in commitment. Of course, ludus may eventually result in eros—and hopefully not mania—if feelings of passion or romance emerge during the relationship.

The Latin lūdus is related to the playful words ludic and ludicrous.

pragma

Original Greek: πράγμα (prágma)

Pragma is practical love. Pragma is love based on duty, obligation, or logic.

Pragma is the unsexy love that you might find in the political, arranged marriages throughout history. This businesslike love is seen in relationships where practicality takes precedence over sex and romance. For example, two people may be in a relationship because of financial reasons or because they have more to lose by breaking up than staying together.

Pragma may even involve a person tolerating or ignoring their partner’s infidelity, as was common in politically motivated royal marriages in much of world history. Pragma may not sound all that great to many, but it is possible for pragma to coexist alongside other types of love, such as ludus or even eros.

As you might have guessed, pragma is related to pragmatic, a word that is all about practicality.

What’s the difference between pragmatic and dogmatic?

philautia

Original Greek: ϕιλαυτία (philautía)

Philautia is self-love. No, not that kind. Philautia refers to how a person views themselves and how they feel about their own body and mind.

The modern equivalent of philautia would be something like self-esteem (good) or hubris (bad). People with high self-esteem, pride in themselves, or a positive body image practice a healthy version of philautia. Of course, philautia has a dark side, too. Egomaniacal narcissists who think they are better than everybody else are also an example of philautia, but not in a healthy way. The duality of philautia just goes to show that love, even self-love, can often get pretty complicated.

Take the quiz

Now that you have learned the language of love that goes beyond “sweet nothings” and heart-shaped candies, head over to our quiz on these words for a hearty challenge.

There are a number of different Greek words for love, as the Greek language distinguishes how the word is used. Ancient Greek has three distinct words for love: «eros», «philia», and «agape». However, as with other languages, it has been historically difficult to separate the meanings of these words. Nonetheless, the senses in which these words were generally used are given below.

* «Eros» (polytonic|ἔρως «érōs») is passionate love, with sensual desire and longing. The Modern Greek word «erotas» means «(romantic) love». However, «eros» does not have to be sexual in nature. «Eros» can be interpreted as a love for someone whom you love more than the «philia» love of friendship. It can also apply to dating relationships as well as marriage. Plato refined his own definition. Although «eros» is initially felt for a person, with contemplation it becomes an appreciation of the beauty within that person, or even becomes appreciation of beauty itself. It should be noted Plato does not talk of physical attraction as a necessary part of love, hence the use of the word platonic to mean, «without physical attraction». Plato also said «eros» helps the soul recall knowledge of beauty, and contributes to an understanding of spiritual truth. Lovers and philosophers are all inspired to seek truth by «eros». The most famous ancient work on the subject of «eros» is Plato’s «Symposium», which is a discussion among the students of Socrates on the nature of «eros».

* «Philia» (polytonic|φιλία «philía»), which means friendship in modern Greek, a dispassionate virtuous love, was a concept developed by Aristotle. It includes loyalty to friends, family, and community, and requires virtue, equality and familiarity. In ancient texts, «philia» denoted a general type of love, used for love between family, between friends, a desire or enjoyment of an activity, as well as between lovers. This is the only other word for «love» used in the ancient text of the New Testament besides «agape», but even then it is used substantially less frequently.

* «Agapē» (polytonic|ἀγάπη «agápē») means «love» in modern day Greek, such as in the term «s’agapo» (Σ’αγαπώ), which means»I love you». In Ancient Greek it often refers to a general affection rather than the attraction suggested by «eros»; «agape» is used in ancient texts to denote feelings for a good meal, one’s children, and the feelings for a spouse. It can be described as the feeling of being content or holding one in high regard. The verb appears in the New Testament describing, amongst other things, the relationship between Jesus and the beloved disciple. In biblical literature, its meaning and usage is illustrated by self-sacrificing, giving love to all—both friend and enemy. It is used in Matthew 22:39, «Love your neighbour as yourself,» and in John 15:12, «This is my commandment, that you love one another as I have loved you,» and in 1 John 4:8, «God is love.» However, the word «agape» is not always used in the New Testament in a positive sense. II Timothy 4:10 uses the word in a negative sense. The Apostle Paul writes,»For Demas hath forsaken me, having loved («agapo») this present world….» Thus the word «agape» is not always used of a divine love or the love of God. Christian commentators have expanded the original Greek definition to encompass a total commitment or self-sacrificial love for the thing loved. Because of its frequency of use in the New Testament, Christian writers have developed a significant amount of theology based solely on the interpretation of this word.

* «Storge» (polytonic|στοργή «storgē») means «affection» in modern Greek; it is natural affection, like that felt by parents for offspring. Rarely used in ancient works, and then almost exclusively as a descriptor of relationships within the family.

* «Thelema» (polytonic|θέλημα «thélēma») means «desire» in modern Greek; it is the desire to do something, to be occupied, to be in prominence.

ee also

*»The Four Loves» by C. S. Lewis.

*Greek love

Wikimedia Foundation.

2010.