(from As You Like It, spoken by Jaques)

All the world’s a stage,

And all the men and women merely players;

They have their exits and their entrances;

And one man in his time plays many parts,

His acts being seven ages. At first the infant,

Mewling and puking in the nurse’s arms;

And then the whining school-boy, with his satchel

And shining morning face, creeping like snail

Unwillingly to school. And then the lover,

Sighing like furnace, with a woeful ballad

Made to his mistress’ eyebrow. Then a soldier,

Full of strange oaths, and bearded like the pard,

Jealous in honour, sudden and quick in quarrel,

Seeking the bubble reputation

Even in the cannon’s mouth. And then the justice,

In fair round belly with good capon lin’d,

With eyes severe and beard of formal cut,

Full of wise saws and modern instances;

And so he plays his part. The sixth age shifts

Into the lean and slipper’d pantaloon,

With spectacles on nose and pouch on side;

His youthful hose, well sav’d, a world too wide

For his shrunk shank; and his big manly voice,

Turning again toward childish treble, pipes

And whistles in his sound. Last scene of all,

That ends this strange eventful history,

Is second childishness and mere oblivion;

Sans teeth, sans eyes, sans taste, sans everything.

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

«All the world’s a stage» is the phrase that begins a monologue from William Shakespeare’s pastoral comedy As You Like It, spoken by the melancholy Jaques in Act II Scene VII Line 139. The speech compares the world to a stage and life to a play and catalogues the seven stages of a man’s life, sometimes referred to as the seven ages of man.

Text[edit]

All the world’s a stage,

And all the men and women merely Players;

They have their exits and their entrances,

And one man in his time plays many parts,

His Acts being seven ages. At first, the infant,

Mewling and puking in the nurse’s arms.

Then the whining schoolboy, with his satchel

And shining morning face, creeping like snail

Unwillingly to school. And then the lover,

Sighing like furnace, with a woeful ballad

Made to his mistress’ eyebrow. Then a soldier,

Full of strange oaths and bearded like the pard,

Jealous in honor, sudden and quick in quarrel,

Seeking the bubble reputation

Even in the cannon’s mouth. And then the justice,

In fair round belly with good capon lined,

With eyes severe and beard of formal cut,

Full of wise saws and modern instances;

And so he plays his part. The sixth age shifts

Into the lean and slippered pantaloon,

With spectacles on nose and pouch on side;

His youthful hose, well saved, a world too wide

For his shrunk shank, and his big manly voice,

Turning again toward childish treble, pipes

And whistles in his sound. Last scene of all,

That ends this strange eventful history,

Is second childishness and mere oblivion,

Sans teeth, sans eyes, sans taste, sans everything.

Origins[edit]

World as a stage[edit]

The comparison of the world to a stage and people to actors long predated Shakespeare. Richard Edwards’ play Damon and Pythias, written in the year Shakespeare was born, contains the lines, «Pythagoras said that this world was like a stage / Whereon many play their parts; the lookers-on, the sage».[2] When it was founded in 1599 Shakespeare’s own theatre, The Globe, may have used the motto Totus mundus agit histrionem (All the world plays the actor), the Latin text of which is derived from a 12th-century treatise.[3] Ultimately the words derive from quod fere totus mundus exercet histrionem (because almost the whole world are actors) attributed to Petronius, a phrase which had wide circulation in England at the time.

In his own earlier work, The Merchant of Venice, Shakespeare also had one of his main characters, Antonio, comparing the world to a stage:

I hold the world but as the world, Gratiano;

A stage where every man must play a part,

And mine a sad one.— Act I, Scene I

In his work The Praise of Folly, first printed in 1511, Renaissance humanist Erasmus asks, «For what else is the life of man but a kind of play in which men in various costumes perform until the director motions them off the stage.»[4]

Ages of man[edit]

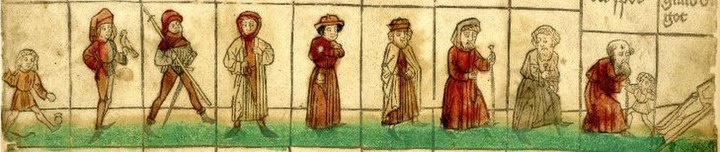

The Ages of Man, German, 1482 (ten, including a final skeleton)

Likewise the division of human life into a series of ages was a commonplace of art and literature, which Shakespeare would have expected his audiences to recognize. The number of ages varied: three and four being the most common among ancient writers such as Aristotle. The concept of seven ages derives from ancient Greek philosophy. Solon, the Athenian lawgiver, described life as 10 periods of 7 years in the following elegiac verses:

«In seven years from th’ earliest breath,

The child puts forth his hedge of teeth;

When strengthened by a similar span,

He first displays some signs of man.

As in a third, his limbs increase,

A beard buds o’er his changing face.

When he has passed a fourth such time,

His strength and vigour’s in its prime.

When five times seven years o’er his head

Have passed, the man should think to wed;

At forty two, the wisdom’s clear

To shun vile deed of folly or fear:

While seven times seven years to sense

Add ready wit and eloquence.

And seven years further skill admit

To raise them to their perfect height.

When nine such periods have passed,

His powers, though milder grown, still last;

When God has granted ten times seven,

The aged man prepares for heaven.»

In Psalm 90, attributed to Moses, it is also written, «Our days may come to seventy years, or eighty, if our strength endures; yet the best of them are but trouble and sorrow, for they quickly pass, and we fly away.»

The Jewish Philosopher Philo of Alexandria writes in his work ‘On Creation’: «Hippocrates the physician says that there are Seven ages of man, infancy, childhood, boyhood, youth, manhood, middle age, old age; and that these too, are measured by periods of seven, though not in the same order. And he speaks thus; «In the nature of man there are seven seasons, which men call ages; infancy, childhood, boyhood, and the rest. He is an infant till he reaches his seventh year, the age of the shedding of his teeth. He is a child till he arrives at the age of puberty, which takes place in fourteen years. He is a boy till his beard begins to grow, and that time is the end of a third period of seven years. He is a youth till the completion of the growth of his whole body, which coincides with the fourth seven years. Then he is a man till he reaches his forty-ninth year, or seven times seven periods. He is a middle aged man till he is fifty-six, or eight times seven years old; and after that he is an old man.»

Because of such sanctity in the number seven, Philo says, Moses wrote of the creation of the world in seven stages.http://www.earlychristianwritings.com/yonge/book1.html In medieval philosophy as well, seven was considered an important number, as for example the seven deadly sins.

[5] King Henry V had a tapestry illustrating the seven ages of man.[6]

According to T. W. Baldwin, Shakespeare’s version of the concept of the ages of man is based primarily upon Pier Angelo Manzolli’s book Zodiacus Vitae, a school text he might have studied at the Stratford Grammar School, which also enumerates stages of human life. He also takes elements from Ovid and other sources known to him.[7]

See also[edit]

- The Seven Ages of Man (painting series)

- Ages of Man

- Riddle of the Sphinx

References[edit]

- ^ William Shakespeare (1623). Mr. William Shakespeares Comedies, Histories, & Tragedies: Published According to the True Originall Copies. London: Printed by Isaac Iaggard, and Ed[ward] Blount. p. 194. OCLC 606515358.

- ^ Joseph Quincy Adams Jr., Chief Pre-Shakespearean Dramas: A Selection of Plays Illustrating the History of the English Drama from Its Origin down to Shakespeare, Houghton Mifflin Company, Boston; New York, 1924, p. 579.

- ^ Marjorie B. Garber (2008). Profiling Shakespeare. Routledge. p. 292.

- ^ John Masters (1956). The Essential Erasmus. The New American Library. p. 119.

- ^ J. A. Burrow (1986). The Ages of Man: A Study in Medieval Writing and Thought. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- ^ PROME, 1423 October, item 31, entries 757–797, quoted in Ian Mortimer, 1415 – Henry V’s Year of Glory (2009), p. 45, footnote 2.

- ^ Thomas Whitfield Baldwin (1944). William Shakspere’s Small Latine and Lesse Greeke. Vol. 1. Urbana, Illinois: University of Illinois Press. pp. 652–673.

External links[edit]

The dictionary definition of all the world’s a stage at Wiktionary

(by William Shakespeare)

| Прослушать на английском — All the World’s a Stage |

Ваш браузер не поддерживает этот аудиопроигрыватель. |

|

На английском |

На русском |

|---|---|

|

All the world’s a stage, And all the men and women merely players; They have their exits and their entrances, And one man in his time plays many parts, His acts being seven ages. At first, the infant, Mewling and puking in the nurse’s arms. Then the whining schoolboy, with his satchel And shining morning face, creeping like snail Unwillingly to school. And then the lover, Sighing like furnace, with a woeful ballad |

Весь мир – лишь сцена, люди — лишь актеры У каждого есть выходы, уходы И каждый в этом театре погорелом Играет главных несколько ролей… Точнее – семь. Сперва младенец нежный Рыгающий у няньки на руках, А после – школьник со своею сумкой Плетущийся, улитке уподобясь, В класс, как на каторгу. Что далее? Любовник! Взвывающий не хуже горна в кузне Тоскливую балладу о бровях |

|

Made to his mistress’ eyebrow. Then a soldier, Full of strange oaths and bearded like the pard, Jealous in honor, sudden and quick in quarrel, Seeking the bubble reputation Even in the cannon’s mouth. And then the justice, In fair round belly with good capon lined, With eyes severe and beard of formal cut, Full of wise saws and modern instances; And so he plays his part. The sixth age shifts Into the lean and slippered pantaloon, |

Тоскливую балладу о бровях Возлюбленной своей. Затем солдат Как леопард обросший бородою, Ругательств полон, быстр на подъем Когда дойдет до драки; ищет славы Он даже в жерле пушки, а потом, Коль выживет, становится судьёю Смотрите, обзавелся он брюшком Заполнил его курочкой, и даже Он бороду подстриг, а изо рта |

|

With spectacles on nose and pouch on side; His youthful hose, well saved, a world too wide For his shrunk shank, and his big manly voice, Turning again toward childish treble, pipes And whistles in his sound. Last scene of all, That ends this strange eventful history, Is second childishness and mere oblivion, Sans teeth, sans eyes, sans taste, sans everything. |

Не ругань льется, а сплошная мудрость. Что ж, следующий акт: он в панталонах, В домашних туфлях, на носу очки. Его, когда-то зычный, бас сменился Ребячьим писком; дудки и свистки Звучат в нем. Наш герой нас покидает Чтобы предстать в Последней Сцене,там Он снова в детство впал, утратил память, И вот конец истории его: Без глаз, зубов, без вкуса – без всего. |

- На русском

- На английском

Весь мир — театр.

В нём женщины, мужчины — все актеры.

У них свои есть выходы, уходы,

И каждый не одну играет роль.

Семь действий в пьесе той. Сперва младенец,

Ревущий громко на руках у мамки…

Потом плаксивый школьник с книжкой сумкой,

С лицом румяным, нехотя, улиткой

Ползущий в школу. А затем любовник,

Вздыхающий, как печь, с балладой грустной

В честь брови милой. А затем солдат,

Чья речь всегда проклятьями полна,

Обросший бородой, как леопард,

Ревнивый к чести, забияка в ссоре,

Готовый славу бренную искать

Хоть в пушечном жерле. Затем судья

С брюшком округлым, где каплун запрятан,

Со строгим взором, стриженой бородкой,

Шаблонных правил и сентенций кладезь,—

Так он играет роль. Шестой же возраст —

Уж это будет тощий Панталоне,

В очках, в туфлях, у пояса — кошель,

В штанах, что с юности берег, широких

Для ног иссохших; мужественный голос

Сменяется опять дискантом детским:

Пищит, как флейта… А последний акт,

Конец всей этой странной, сложной пьесы —

Второе детство, полузабытье:

Без глаз, без чувств, без вкуса, без всего.

All the world’s a stage,

And all the men and women merely players:

They have their exits and their entrances;

And one man in his time plays many parts,

His acts being seven ages. At first the infant,

Mewling and puking in the nurse’s arms.

And then the whining school-boy, with his satchel,

And shining morning face, creeping like snail

Unwillingly to school. And then the lover,

Sighing like furnace, with a woful ballad

Made to his mistress’ eyebrow. Then a soldier,

Full of strange oaths, and bearded like the pard,

Jealous in honour, sudden and quick in quarrel,

Seeking the bobble reputation.

Even in the cannon’s mouth. And then the justice,

In fair round belly with good capon lin’d,

With eyes severe, and beard of formal cut,

Full of wise saws and modern instances;

And so he plays his part. The sixth age shifts

Into the lean and slipper’d pantaloon

With spectacles on nose well and pouch on side,

His youthful hose well sav’d a world too wide

For his shrunk shank; and his big manly voice,

Turning again toward childish treble, pipes

And whistles in his sound. Last scene of all,

That ends his strange eventful history,

In second childishness and mere oblivion

Sans teeth, sans eyes, sans taste, sans everything.

Перевод Т. Л. Щепкиной-Куперник (1952).

«Весь мир — театр» в исполнении Бенедикта Камберберча

Ромео и Джульетта

Цитаты из бессмертной традегии Шекспира и пара видео из фильмов по пьесе.

Быть или не быть, вот в чём вопрос

Монолог принца датского о жизни и смерти. Вильям Шекспир.

All the world’s a stage,

And all the men and women merely players;

They have their exits and their entrances,

And one man in his time plays many parts,

His acts being seven ages. At first, the infant,

Mewling and puking in the nurse’s arms.

Then the whining schoolboy, with his satchel

And shining morning face, creeping like snail

Unwillingly to school. And then the lover,

Sighing like furnace, with a woeful ballad

Made to his mistress’ eyebrow. Then a soldier,

Full of strange oaths and bearded like the pard,

Jealous in honor, sudden and quick in quarrel,

Seeking the bubble reputation

Even in the cannon’s mouth. And then the justice,

In fair round belly with good capon lined,

With eyes severe and beard of formal cut,

Full of wise saws and modern instances;

And so he plays his part. The sixth age shifts

Into the lean and slippered pantaloon,

With spectacles on nose and pouch on side;

His youthful hose, well saved, a world too wide

For his shrunk shank, and his big manly voice,

Turning again toward childish treble, pipes

And whistles in his sound. Last scene of all,

That ends this strange eventful history,

Is second childishness and mere oblivion,

Sans teeth, sans eyes, sans taste, sans everything.

The famous speech ‘All the world’s a stage’ was first published as part of As You Like It in the First Folio in 1623. Scholars are unsure when the play was performed for the first time but it was likely sometime around 1603. The play is a five-act pastoral comedy that features a monologue in which Jacques considers the nature of the world, the roles men and women play, and how one ages, being “All the world’s a stage”.

(from As You Like It, spoken by Jaques to Duke Senior) All the world’s a stage, And all the men and women merely players; They have their exits and their entrances; And one man in his time plays many parts, His acts being seven ages. At first the infant, Mewling and puking in the nurse’s arms; And then the whining school-boy, with his satchel And shining morning face, creeping like snail Unwillingly to school. And then the lover, Sighing like furnace, with a woeful ballad Made to his mistress’ eyebrow. Then a soldier, Full of strange oaths, and bearded like the pard, Jealous in honour, sudden and quick in quarrel, Seeking the bubble reputation Even in the cannon’s mouth. And then the justice, In fair round belly with good capon lin’d, With eyes severe and beard of formal cut, Full of wise saws and modern instances; And so he plays his part. The sixth age shifts Into the lean and slipper’d pantaloon, With spectacles on nose and pouch on side; His youthful hose, well sav’d, a world too wide For his shrunk shank; and his big manly voice, Turning again toward childish treble, pipes And whistles in his sound. Last scene of all, That ends this strange eventful history, Is second childishness and mere oblivion; Sans teeth, sans eyes, sans taste, sans everything.

Summary

‘All the world’s a stage’ is a monologue of “the melancholy Jaques” from Act II Scene VII of the play As You Like It by William Shakespeare.

The speaker, Jacques, begins “All the world’s a stage” by asserting that life is like a stage on which “men and women merely” play roles. They play different parts throughout their lives, as the speaker is now. In the bulk of this monologue, the speaker spends time going through the seven ages of man. One starts in infancy, moves through childhood, and into the best part of their life when they’re a lover, soldier, and judge. Later, they lose control of their senses and eventually can’t take care of themselves.

You can read the full speech here with the analysis or watch Benedict Cumberbatch recite ‘All the world’s a stage’.

Meaning

Shakespeare uses the monologue in As You Like It to compare life to a stage on its most basic level. His speaker, Jacques, is suggesting that life is a stage, and men and women are players who take on different roles throughout their lives. The concept comes, in part, from medieval philosophy. The “seven ages” dates from the 12th century. There was a tapestry of King Henry V depicting the seven stages of man. For theological reasons, medieval philosophers constructed groups of seven as in the seven deadly sins. Therefore, it is believed that the “seven ages” derive from medieval philosophy.

Structure and Form

‘All the world’s a stage’ is an excerpt from William Shakespeare’s well-loved play, As You Like It. Specifically, it is a monologue that is spoken by the melancholy Jaques. The monologue is twenty-eight lines long and is in part written in blank verse, or unrhymed iambic pentameter. This means that the lines do not rhyme, but they do (at some points) contain five sets of two beats, the first of which is unstressed and the second of which is stressed.

It is also important to consider how a performer might’ve used the stage to their advantage when performing these lines and the impact that formal elements like enjambment and alliteration would’ve had on the audience’s understanding of the speech.

Literary Devices

Shakespeare makes use of several literary devices in this speech. Some are:

- Simile: ‘creeping like a snail”; “soldier… bearded like the pard”; etc.

- Metaphor: The entire speech itself is more like symbolism; men and women are portrayed as players whereas life is portrayed as the stage. Shakespeare uses the “stage” as an extended metaphor.

- Repetition: Another figure of speech used in this monologue; words like sans, age, etc. are repeated for the sake of emphasis.

- Anaphora: It is used in the eighth and ninth lines, beginning with the word “And”.

- Synecdoche: “Made to his mistress’ eyebrow”; “And then the justice”; etc.

- Alliteration: “his shrunk shank”; “quick in quarrel”; etc.

- Onomatopoeia: “pipes / And whistles in his sound”

- Asyndeton: “Sans teeth, sans eyes, sans taste, sans everything.”

The Seven Ages of Man

The seven stages of life, as described by Jacques in ‘All the world’s a stage’ are:

- Infancy (lines 5-6): The first stage of man’s life is infantry. In the monologue, readers can find an image of a baby crying softly and throwing up in the caregiver’s lap.

- Boyhood (lines 7-9): The image of a school-going boy unwilling to go to school describes this stage.

- Adolescence/Teenage (lines 9-11): In this stage, Shakespeare presents an image of a dejected lover who composes sad songs for his beloved.

- Youth (lines 11-15): He projects the stage of youth by depicting the life of a soldier. As a soldier, a person in his youths is unafraid of dire challenges.

- Middle Age (lines 15-19): The fifth stage deals with middle age and it is described by the picture of a judge or one who practices law. In this stage of life, one starts to mature and becomes wiser than before.

- Old Age (lines 19-25): Just before the final stage, comes old age, turning the manly voice of youth into the childish trebles and whistling. It makes the body weak and the mind, dependent upon others.

- Death (lines 25-28): In the finale of this seven-act-play of life, the strange and eventful history ends abruptly. It leaves a man with nothing.

Detailed Analysis

Lines 1-6

All the world’s a stage,

And all the men and women merely players;

They have their exits and their entrances,

And one man in his time plays many parts,

His acts being seven ages. At first, the infant,

Mewling and puking in the nurse’s arms.

In the first lines of ‘All the world’s a stage,’ the speaker, Jacques, begins with the famed lines that later came to denote this entire speech. He declares that “All the world’s a stage” and that the people living in it are “merely players.”

This sets up what is one of the most skilled conceits in all of English literature. Every person, no matter who they are, where they were born, or what they want to do with their lives, wakes up every day with a role. They enter, they exit, just like performers.

It’s important to note at this point that these lines would be read on stage in front of an audience. The extended metaphor would not be lost on anyone listening or watching. The actor is declaring to the audience that “you” are just as much of an actor as he is.

Before the listener starts to get concerned about the role they have to play, Jacques adds that a “man,” (or woman) plays many different parts in their lives, as an actor does. Whoever the actor may be on stage is not only “Jacques” he’s also many other characters throughout his career. It’s in the fifth line of the monologue that Shakespeare brings in a slightly more complex concept, that of the “seven ages” of humankind. The first of these is the “infant”.

Lines 7-18

And then the whining schoolboy, with his satchel

And shining morning face, creeping like snail

Unwillingly to school. And then the lover,

Sighing like furnace, with a woeful ballad

Made to his mistress’ eyebrow. Then a soldier,

Full of strange oaths and bearded like the pard,

Jealous in honour, sudden and quick in quarrel,

Seeking the bubble reputation

Even in the cannon’s mouth. And then the justice,

In fair round belly with good capon lined,

With eyes severe and beard of formal cut,

Full of wise saws and modern instances;

As the speech progresses, Jacque continues to describe how someone ages, the roles they play, and what everyone is like, generally, at different times in their lives. One will at some point be a “whining school-boy” and a “lover / Sighing like furnace.” There will be sorrows, ballads, and losses. One will become “a soldier” and take oaths of allegiance while seeking out a fight. This is one of the more difficult stages in one’s life and if drafted, not one that someone could ignore.

The man’s youth has given way to a full beard like a “pard,” or leopard. In these lines, there is also an interesting metaphor comparing a human or animal blowing a bubble with its mouth to staring down a cannon that might fire at any moment. Finally, this metaphorical person becomes “the justice,” or magistrate, someone with a steadier knowledge of what’s right and wrong. They have “Wise saws,” or wise sayings and “modern instances,” or arguments for legal cases.

Lines 19-28

And so he plays his part. The sixth age shifts

Into the lean and slippered pantaloon,

With spectacles on nose and pouch on side;

His youthful hose, well saved, a world too wide

For his shrunk shank, and his big manly voice,

Turning again toward childish treble, pipes

And whistles in his sound. Last scene of all,

That ends this strange eventful history,

Is second childishness and mere oblivion,

Sans teeth, sans eyes, sans taste, sans everything.

In the sixth stage of man’s life, he moves into the “pantaloon” or comfortable clothes worn by old men. His youthful clothes are too loose because he’s lost weight with age. He’s also lost his deep voice. It reverted back to something that’s closer to what he had in one of the earlier stages of his life.

The last stage of a man’s life is his “second childishness and mere oblivion.” This is when he loses control of everything that made him an adult. Now, he’s helpless and dependent on others, as he was when he was a child. He is “sans,” or without, “taste,” “eyes,” and “teeth.” The final image is the man without “everything.” His life, all its intricate memories, and details are lost.

Themes

In ‘All the world’s a stage’ Shakespeare discusses the futility of humanity’s place in the world. He explores themes of time, aging, memory, and the purpose of life. Through the monologue’s central conceit, that everyone is simply a player in a larger game that they have no control over, he brings the themes together. Shakespeare takes the reader through the stages of life, starting with infancy and childhood and ending up with an old man who’s been a lover, a soldier, and a judge. The “man” dies after reverting back to a state that’s close to childhood and infancy. You can also explore the themes in other William Shakespeare poems.

Tone and Mood

In ‘All the world’s a stage’ Shakespeare creates a somber and depressing mood through the simple breakdown of life, success, love, and death. The beauties of life are compiled into a short monologue that’s over almost as soon as it began. With this, the reader is left to consider their own life and what “stage” they’re in now. The speaker knows that this is the way the world is, everyone listening to his words is all going to end up back where they started as children and there’s no way to change that fact.

Historical Context

In Shakespeare’s comedy As You Like It, Rosalind and Celia encounter some memorable characters in the Forest of Arden. Jaques, the melancholy traveler, is the most notable of them all. He speaks many famous speeches such as “too much of a good thing”, “A fool! A fool! I met a fool in the forest”, and “All the world’s a stage”.

Jaques’ monologue is an echo of the motto of the new Globe Theatre which was opened in the summer of 1599. The motto was “Totus mundus agit histrionem”, meaning “all the Globe’s a stage”. The play was written in the same year.

In his book “William Shakspere’s Small Latine and Lesse Greeke”, T. W. Baldwin states that Shakespeare’s version of the monologue is based upon Palingenius’ “Zodiacus Vitae”. Shakespeare would have studied this school text at the Stafford Grammar School. The text also presents stages of a man’s lifespan. He would have taken inspiration from Ovid and Juvenal.

FAQs

Who said, “All the world’s a stage”?

In Act 2, Scene 7, Line 139 of William Shakespeare’s pastoral comedy As You Like It, the melancholy Jaques said the monologue ‘All the world’s a stage’.

What is the central theme of ‘All the world’s a stage’?

The central theme of this monologue is life and its seven stages. Shakespeare describes the phases that are observed in a man’s lifespan.

Why does Shakespeare call the world a “stage”?

According to Shakespeare, the “world” is like a “stage”. The stage remains permanent. Only the actors and actresses change with time. They have their parts to play. When the curtain slides down, they are no more. The stage becomes empty. It makes way for a new play, maybe the next day or the day after tomorrow. We, human beings, are like artists. We play our roles as someone’s child, lover, life partner, or grandparents during our lifespan. When our time comes, the sidewalk is our only destination leading us to the leaden death.

What message does ‘All the world’s a stage’ convey?

Through this monologue, Shakespeare gives the message of life’s impermanence. How quickly the play of our life ends and the strange eventful lays are concluded get featured in this speech.

Why is the last stage called “second childishness”?

The term, “second childishness” refers to the cognitive decline of an old person. It is characterized by childlike judgment and behavior. Shakespeare called the last stage of man’s life the “second childishness” for this reason.

What does “Sans teeth, sans eyes, sans taste, sans everything” mean?

The word “sans” is a preposition that is generally used in literary works. This word adds a flavor of humor to the line where it is used. Literally, it means “without” or “in the absence of something”. In this line, the use of palilogy (repetition of “sans”) puts emphasis on the nothingness in the last stage of a human’s life that is “mere oblivion”.

What does “Sighing like furnace” mean?

The lover’s sigh is compared to the exhausts of a furnace. A man in his youths is driven by the carnal desires that fuel his heart. It kindles the burning desire for love there. When the fire is blown out by the current of a lady’s rejection, the heart sighs like a furnace. The heat of passion is there but the fire of heartfelt emotions is extinguished.

Similar Poetry and Quotes

Readers who enjoyed the ‘All the world’s a stage’ monologue should also consider reading some of William Shakespeare’s 154 sonnets and poems from other writers. For example:

- ‘Sonnet 73′ – This sonnet is a part of the “Fair Youth” sequence. It speaks about aging and uses a pensive, introspective tone.

- ‘Sonnet 5’ – This poem depicts the passing of time and relates nature’s four seasons with life’s stages.

- ‘On Aging’ by Maya Angelou – It’s one of the best-known poems of Maya Angelou. This poem explores what it means to get old and the truth about age. Explore more Maya Angelou poems.

- ‘Auguries of Innocence’ by William Blake – It’s one of the best-loved poems of William Blake. This poem presents a series of paradoxical ideas revolving around the theme of innocence vs experience. Read more William Blake poems.

You can also consider reading about these psychologically probing speeches from Shakespearean plays.

- ‘Tomorrow, and tomorrow, and tomorrow’ monologue from Macbeth

- ‘To be, or not to be’ soliloquy from Hamlet

- ‘The quality of mercy is not strained’ monologue from The Merchant of Venice

‘All the world’s a stage’ is the opening line from a monologue by a character, Jaques, in William Shakespeare’s play, As You Like It.

Through Jaques, Shakespeare takes the audience on a journey of the complete lifecycle of a human being, made particularly vivid by its visual images of the different stages of an Elizabethan’s life. The famous monologue is also known as ‘The Seven Ages of Man.’

‘All the world’s a stage’ monologue, spoken by Jaques, Act 2 Scene 7

All the world’s a stage,

And all the men and women merely players;

They have their exits and their entrances,

And one man in his time plays many parts,

His acts being seven ages. At first, the infant,

Mewling and puking in the nurse’s arms.

Then the whining schoolboy, with his satchel

And shining morning face, creeping like snail

Unwillingly to school. And then the lover,

Sighing like furnace, with a woeful ballad

Made to his mistress’ eyebrow. Then a soldier,

Full of strange oaths and bearded like the pard,

Jealous in honor, sudden and quick in quarrel,

Seeking the bubble reputation

Even in the cannon’s mouth. And then the justice,

In fair round belly with good capon lined,

With eyes severe and beard of formal cut,

Full of wise saws and modern instances;

And so he plays his part. The sixth age shifts

Into the lean and slippered pantaloon,

With spectacles on nose and pouch on side;

His youthful hose, well saved, a world too wide

For his shrunk shank, and his big manly voice,

Turning again toward childish treble, pipes

And whistles in his sound. Last scene of all,

That ends this strange eventful history,

Is second childishness and mere oblivion,

Sans teeth, sans eyes, sans taste, sans everything.

(act ii, scene vii)

In this ‘all the world’s a stage’ monologue, Shakespeare is seeing life as a drama acted out on a stage in a theatre. Each phase of life is an act in the drama.

William Shakespeare knew or understood a lot about many things. He knew about the lives of monarchs and the way they operate – what goes on in their private and public lives; he knew about low life in the inns and taverns of London, and he knew about the lives of rural folk. He knew about warfare and diplomacy and he knew much more.

However, he often used his own specific area of expertise – the theatre – as fodder for his poetry. None of his plays are actually about the theatre, although A Midsummer Night’s Dream has a play production at its center, and there is the famous play-within-the-play in Hamlet, but he uses the theatre more as a source for the imagery in the language of his plays – for making poetry. He does that over and over again. This monologue is probably his most famous poetic allusion to the theatre because it is a view of the whole of life as a play.

Of course, the monologue is not actually about the theatre. The theatrical reference is just a way of introducing what Shakespeare really wants to convey, which is an outline of a man’s journey from birth to the grave. He does that magnificently, from vivid images of a healthy baby to the very sad descent into oblivion, ‘sans everything’ – of an old man with nothing left of his life.

The idea of a man’s life being no more than a brief appearance on a stage is something that fascinated Shakespeare. Macbeth sees his life in that way – you strut about and stress on the stage but all those passions and, indeed, everything you do in life, is meaningless, as at the end of that you just disappear. Like an actor anguishing on the stage over the trials of life, with great passion, and then, after the performance, just going home to resume his normal life.

It’s a religious idea in a way. An actor playing out the human drama is only an actor. At the end of the show he resumes a different, more permanent, life – an afterlife – and what he has done on the stage, in other words, in his life, is just an act. Real life lies beyond that.

Now you read the context around Shakespeare’s ‘All the world’s a stage’ monologue try one more read-through to see if you can pick up anything you missed the first time around:

All the world’s a stage,

And all the men and women merely players;

They have their exits and their entrances,

And one man in his time plays many parts,

His acts being seven ages. At first, the infant,

Mewling and puking in the nurse’s arms.

Then the whining schoolboy, with his satchel

And shining morning face, creeping like snail

Unwillingly to school. And then the lover,

Sighing like furnace, with a woeful ballad

Made to his mistress’ eyebrow. Then a soldier,

Full of strange oaths and bearded like the pard,

Jealous in honor, sudden and quick in quarrel,

Seeking the bubble reputation

Even in the cannon’s mouth. And then the justice,

In fair round belly with good capon lined,

With eyes severe and beard of formal cut,

Full of wise saws and modern instances;

And so he plays his part. The sixth age shifts

Into the lean and slippered pantaloon,

With spectacles on nose and pouch on side;

His youthful hose, well saved, a world too wide

For his shrunk shank, and his big manly voice,

Turning again toward childish treble, pipes

And whistles in his sound. Last scene of all,

That ends this strange eventful history,

Is second childishness and mere oblivion,

Sans teeth, sans eyes, sans taste, sans everything.

•• Не знаю, сколько у английского языка «источников» и «составных частей», но два источника современной английской идиоматики можно назвать без колебаний – это Библия в варианте короля Якова (разумеется, не Джеймса!) –

the King James Version of 1611

(см. статью Bible words and phrases) и Шекспир. В известном английском анекдоте некая дама говорит, что Шекспир ей нравится, но одно раздражает – обилие клише! Шекспир – самый цитируемый автор, и слова, выражения, иногда целые пассажи из Шекспира встречаются в речи людей, читавших его очень давно или не читавших вообще. Удивительная сила шекспировского слова в не меньшей степени, чем его гений драматурга, заставляет многих сомневаться, что автором великих произведений действительно был ничем не примечательный и, судя по сохранившимся обрывкам исторических сведений, малопривлекательный житель Стрэтфорда. Я разделяю эти сомнения, но здесь рассматривать эту тему нет возможности. К сожалению, в кратком словаре не хватит места и для малой толики шекспировской идиоматики, с которой должен быть хотя бы поверхностно знаком уважающий себя переводчик (в том числе и работающий в основном устно). Ограничимся минимальным «шекспировским ликбезом» в надежде на способность читателя к самообразованию.

•• Конечно, мало людей, не знающих, что именно Шекспиру принадлежат слова To be or not to be: that is the question или A horse! A horse! My Kingdom for a horse (из

«Ричарда III»

), или не знакомых с их «каноническими», вошедшими в русский язык переводами (Быть или не быть – вот в чем вопрос и Коня, коня! Полцарства за коня!). Многие правильно укажут и происхождение другого часто цитируемого отрывка:

•• What’s in a name? That which we call a rose

•• By any other name would smell as sweet.

•• (

Romeo and Juliet

)

•• В переводе Щепкиной-Куперник:

•• Что в имени? То, что зовем мы розой,

•• И под другим названьем сохраняло б

•• Свой сладкий запах.

•• Интересны две цитаты, которые по-русски встречаются едва ли не чаще, чем в английских текстах.

•• All the world’s a stage,

•• And all the men and women merely players.

•• Весь мир – театр, и люди в нем – актеры.

•• (Из комедии

As You Like It

– «Как вам это понравится»)

•• There are more things in heaven and earth, Horatio,

•• Than are dreamt of in your philosophy.

•• Есть многое на свете, друг Горацио,

•• Что и не снилось нашим мудрецам

•• (Из

«Гамлета»

в переводе 1828 года (!) М.Вронченко; именно в таком виде эта цитата вошла в русский язык.)

•• Но вот еще один «шекспиризм», тоже из «Гамлета» и тоже обращенный к Горацио: In my mind’s eye, Horatio (в переводах, с разными вариациями – В очах моей души, Горацио). Подавляющее большинство говорящих по-английски, употребляя это распространенное выражение, не осознают, что «цитируют Шекспира». (По-русски мы скажем что-нибудь вроде в мыслях я вижу или мысленным взором.)

•• Несколько аналогичных примеров:

•• foregone conclusion (из

«Отелло»

). Прочно вошло в язык. Употребляется, когда речь идет о заранее ясном результате, предрешенном деле, о чем-то не вызывающем сомнений. The outcome of the general elections was a foregone conclusion (International Herald Tribune);

•• to the manner born (из «Гамлета»). Означает естественную склонность к чему-то, врожденную способность, легкость в выполнении дела или исполнении обязанностей. Существует вариант to the manor born (разница на письме, но не в произношении). Удачный перевод: У него это в крови;

•• True it is that we have seen better days (из «Как вам это понравится»). Перевод очевиден: Мы видели (у нас были) лучшие времена. Иногда так говорят о женщине не первой молодости: She has seen better days или о политике, переживающем кризис;

•• to wear one’s heart upon one’s sleeve (из «Отелло») – не скрывать своих чувств. По-русски можно сказать душа нараспашку;

•• a plague on both your houses. Слова Меркуцио из «Ромео и Джульетты». Нередко употребляются и в русской речи ( чума на оба ваши дома), часто без малейшего представления об источнике;

•• brevity is the soul of wit. Вошло в поговорку и по-русски (Краткость – душа остроумия). Но все же неплохо знать, что и это – из «Гамлета», где смысл глубже (в переводе М.Лозинского – «Краткость есть душа ума»);

•• brave new world (из «Бури» –

The Tempest

). И конечно, из названия ранее полузапрещенного у нас романа Олдоса Хаксли. У Шекспира: O brave new world that has such people in’t (О, дивный мир, где есть такие люди). У Хаксли («Прекрасный новый мир») мы имеем дело с типичным (и, по-моему, довольно скучным) романом-антиутопией. Надо иметь в виду, что это выражение используется чаще всего иронически или с оттенком осуждения;

•• honorable men (из «Юлия Цезаря» –

Julius Caesar

). Аналогичный случай: иронически-осуждающее употребление, казалось бы, понятного словосочетания. Правда, нередки случаи, когда оно употребляется и в прямом значении ( достойные люди). Но переводчик должен быть внимателен. Многие говорящие по-английски помнят то место в трагедии Шекспира, где Марк Антоний называет Брута an honorable man, имея в виду совершенно обратное. В письменном переводе помогут кавычки («достопочтенные» граждане), в устном придется рискнуть или сказать нечто нейтральное (человек с известной репутацией);

•• there is method in the madness. Видоизмененная цитата из «Гамлета». Подразумевается, что за внешней нелогичностью, странностью какого-то поступка или явления кроется своя логика, свой смысл;

•• more in sorrow than in anger (тоже из «Гамлета»). Пастернаковское «скорей с тоской, чем с гневом» не очень подходит в переводе этого выражения в его современном употреблении. Лучше сказать скорее с сожалением, чем с негодованием/гневом;

•• more sinned against than sinning. Моя любимая цитата из

«Короля Лира»

(так говорит о себе главный герой: I am a man/more sinned against than sinning). В прекрасном, незаслуженно забытом переводе М.Кузмина: Предо мной другие/грешней, чем я пред ними. Образец сжатости и точности!

•• the wheel has come full circle (из «Короля Лира»). Употребляется чаще всего так: we have come full circle – мы пришли к тому, с чего начали;

•• strange bedfellows (из «Бури»). Нередко цитируют как в пьесе (Misery acquaints a man with strange bedfellows – В нужде с кем не поведешься), но чаще всего, не подозревая о шекспировских корнях этой фразы, говорят Politics makes strange bedfellows. Свежая модификация из журнала Time: President Jacques Chirac and newly-elected Prime Minister Lionel Jospin make uneasy bedfellows. Имеются в виду странные (на первый взгляд) политические альянсы, коалиции или, как в последнем примере, «сожительства» (фр. cohabitation). Но ведь не просто так, а bedfellows! Говорящие по-английски, несомненно, чувствуют эту «постельную» коннотацию. Так, в журнале Time процитированная фраза сопровождается соответствующей карикатурой. Так что при желании переводчику есть где развернуться;

•• salad days (из

«Антония и Клеопатры»

). Иногда цитируется, как в пьесе: My salad days, when I was green in judgment. (В переводе М.Донского: Тогда была/девчонкой я неопытной, незрелой. Пожалуй, слово девчонка все-таки неуместно в устах Клеопатры.) Употребляется довольно часто, иногда с иронией: the salad days of detente (W. Safire) – разрядка (международной напряженности) в ее первом цветении. В разговоре можно воспользоваться русским молодо-зелено. Более «серьезный» перевод – период/эпоха становления;

•• at one fell swoop (из

«Макбета»

). Еще один пример, когда шекспировское происхождение фразы почти никем не ощущается (есть и другие – fight till the last gasp – драться/бороться до последнего дыхания из «Генриха VI»/

Henry VI

; as good luck would have it – по счастью; и тут мне улыбнулась удача из «Виндзорских кумушек/проказниц»/

The Merry Wives of Windsor

). At one fell swoop – одним махом, в одночасье, в одно мгновение;

•• sound and fury. Тоже из «Макбета», а также из названия романа Фолкнера (русский перевод «Шум и ярость»). За неимением места невозможно полностью процитировать гениальный монолог Макбета. Главное: [Life] is a tale/Told by an idiot, full of sound and fury/Signifying nothing. В переводе М.Лозинского: Это – новость,/Рассказанная дураком, где много/И шума и страстей, но смысла нет. У Шекспира звучит страшней. Sound and fury в переносном значении может иметь два значения: одно близко к много шума из ничего (кстати, тоже «шекспиризм» – название пьесы Much Ado About Nothing), второе обозначает недюжинные страсти, драматические события. Причем не всегда легко почувствовать контекстуальный смысл;

•• every inch a king (из «Короля Лира»). В переводе Т.Щепкиной-Куперник Король, от головы до ног. Вместо слова king часто употребляются и другие – gentleman, lady, statesman и т.д. По-русски – самый настоящий, до мозга костей. Внимание: нередко употребляется шутливо, иронически;

•• ‘tis neither here nor there. Так в «Отелло». В обиходной речи, конечно, it’s. В Англо-русском фразеологическом словаре А.В.Кунина не указано шекспировское происхождение этой фразы. Не стоит переводить ее русским ни к селу, ни к городу (слишком силен русский колорит). Может быть, это не из той оперы? Пожалуй, лучше оставаться в рамках нейтрального стиля: это несущественно/к делу не относится/я говорил о другом;

•• cry havoc (из бессмертного «Юлия Цезаря»). В пьесе: Caesar’s spirit… shall… cry ‘Havoc!’ and let slip the dogs of war. В переводе И.Мандельштама: «Всем смерть!» – собак войны с цепи спуская. В последнее время (может быть, время такое?) популярны обе части этой цитаты – вспомним роман Ф.Форсайта The Dogs of War. Переносный смысл довольно разнообразен – давать сигнал к грабежу, заниматься подстрекательством; вести беспощадную войну, разорять все вокруг и т.д. Но есть и другое значение cry havoc – кричать караул, сеять панику. Ср. play havoc with something – сеять разрушение, опустошать, дезорганизовать.

•• Что сказать в заключение (и в свое оправдание)? «Нельзя объять необъятного» (это, конечно, не из Шекспира, а из Козьмы Пруткова, но тоже может поставить в тупик переводчика. Возможный – сознаюсь, не блестящий – вариант перевода You can’t cover what’s boundless. Можно сказать и проще: I couldn’t do it if I tried!).