1) Вставьте слово, которое грамматически будет соответствовать содержанию текста.

The name of Alaska

The name Alaska comes from the Aleut word alaxsxaq, ___ (MEAN) “object toward which the action of the sea is directed” – that is, the mainland.

2) Вставьте слово, которое грамматически будет соответствовать содержанию текста.

It is also known as Alyeska, the “great land”, an Aleut word ___ (FORM) from the same root.

3) Вставьте слово, которое грамматически будет соответствовать содержанию текста.

Its nicknames are the Land of the Midnight Sun and America’s Last Frontier. Its first nicknames were “Seward’s folly” and “Seward’s icebox” to laugh at the secretary of state who negotiated the purchase of Alaska from Russia, which ___ (CONSIDER) foolish at the time.

4) Вставьте слово, которое грамматически будет соответствовать содержанию текста.

A landmark for the new millennium

Have you seen the photos of the London Eye? The London Eye is a giant observation wheel ___ (LOCATE) in the Jubilee Gardens on the South Bank of the river Thames.

5) Вставьте слово, которое грамматически будет соответствовать содержанию текста.

The structure ___ (DESIGN) by the architectural team of David Marks and Julia Barfield, husband and wife.

6) Вставьте слово, которое грамматически будет соответствовать содержанию текста.

They submitted their idea for a large observation wheel as part of a competition to design a landmark for the new millennium. None of the entrants ___ (WIN) the competition.

7) Вставьте слово, которое грамматически будет соответствовать содержанию текста.

However, the couple pressed on and eventually got the backing of British Airways, who sponsored ___ (THEY) project.

Pronunciation is important

Some learners of English think that pronunciation is not very important. That is ___ (ABSOLUTE) wrong.

9) Вставьте слово, которое грамматически и лексически будет соответствовать содержанию текста.

Even if you have an acceptable grasp of the English language, with good grammar and an ___ (EXTEND) vocabulary, native English speakers may find you very difficult to understand you if you don’t work on your pronunciation.

10) Вставьте слово, которое грамматически и лексически будет соответствовать содержанию текста.

Correct, clear pronunciation is ___ (ESSENCE) if you really want to improve your level of English.

11) Вставьте слово, которое грамматически и лексически будет соответствовать содержанию текста.

Pay particular attention to any sounds that you are ___ (FAMILIAR) with or that do not exist in your native tongue.

12) Вставьте слово, которое грамматически и лексически будет соответствовать содержанию текста.

For example, ___ (RUSSIA) have difficulty pronouncing the “th” sound, as it does not exist in their native language.

13) Вставьте слово, которое грамматически и лексически будет соответствовать содержанию текста.

Remember that the pronunciation of certain English words varies depending on the part of the world it’s spoken in. For example, American English differs ___ (GREAT) from British English.

14) Запишите в поле ответа цифру 1, 2, 3 или 4, соответствующую выбранному Вами варианту ответа.

Mexico City

Mexico City was hot and frantic with Olympic gamesmanship. The hotels were full but, fortunately, Kevin owned a country house just outside the city which we ___ our headquarters. The Whites also had their home in Mexico City but they were more often than not at Kevin’s private palace.

1) did

2) made

3) kept

4) used

15) Запишите в поле ответа цифру 1, 2, 3 или 4, соответствующую выбранному Вами варианту ответа.

I must ___ that when Kevin decided to move he moved fast.

1) speak

2) talk

3) say

4) tell

16) Запишите в поле ответа цифру 1, 2, 3 или 4, соответствующую выбранному Вами варианту ответа.

Like a good general, he marshalled his army close to the point of impact; he spent a small fortune on telephone calls and ___ in getting all we needed for the expedition in the shortest time possible.

1) managed

2) achieved

3) fulfilled

4) succeeded

17) Запишите в поле ответа цифру 1, 2, 3 или 4, соответствующую выбранному Вами варианту ответа.

I had a fast decision to make, too. My job was a good one and I hated to give it ___ unceremoniously, but Kevin was pushing hard.

1) to

2) on

3) in

4) up

18) Запишите в поле ответа цифру 1, 2, 3 или 4, соответствующую выбранному Вами варианту ответа.

I ___ my boss and he was good enough to give me six months’ leave of absence. I deceived him in a way, I gave him the right destination but not the real reason for going there.

1) looked

2) glanced

3) saw

4) watched

19) Запишите в поле ответа цифру 1, 2, 3 или 4, соответствующую выбранному Вами варианту ответа.

Yet I think that going to Yucatan could be understood as looking ___ my father’s estate.

1) down

2) after

3) into

4) back

20) Запишите в поле ответа цифру 1, 2, 3 или 4, соответствующую выбранному Вами варианту ответа.

Kevin also used resources that only money can buy. The thought of it made me a bit dizzy. Kevin was able to lift a telephone and set a private police force in motion. It made me open my eyes and think again. There was something about Kevin that got at me. Whatever it was, I preferred to keep it bottled up. Will I ___ it in the future?

1) apologize

2) regret

3) disappoint

4) dissatisfy

Continue Learning about English Language Arts

What does the word biological mean?

What does the word «biological» mean?

What does the word exuberant mean?

what does the word exuberant mean

What Does ilteic Mean?

There is no such word, do you mean the word italic?

What does the word inaudible mean?

what does the word inaudible mean

What does security word mean?

What does security word mean

The Aleuts ( A-lee-OOT;[4] Russian: Алеуты, romanized: Aleuty) are the indigenous people of the Aleutian Islands, which are located between the North Pacific Ocean and the Bering Sea. Both the Aleut people and the islands are politically divided between the US state of Alaska and the Russian administrative division of Kamchatka Krai.

|

унаӈан (unangan) |

|

|---|---|

Attu Aleut mother and child, 1941 |

|

| Regions with significant populations | |

| United States Alaska |

6,752[1] |

| Russia Kamchatka Krai |

482[2] |

| Languages | |

| English, Russian, Aleut[3] | |

| Religion | |

| Eastern Orthodoxy (Russian Orthodox Church), Animism |

|

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Inuit, Yupik, Sirenik, Sadlermiut |

EtymologyEdit

In the Aleut language they are known by the endonyms Unangan (eastern dialect) and Unangas (western dialect), both of which mean «people».[a] The Russian term «Aleut» was a general term used for both the native population of the Aleutian Islands and their neighbors to the east in the Kodiak Archipelago, who were also referred to as «Pacific Eskimos».[6]

LanguageEdit

Aleut people speak Unangam Tunuu, the Aleut language, as well as English and Russian in the United States and Russia respectively. An estimated 150 people in the United States and five people in Russia speak Aleut.[3] The language belongs to the Eskimo-Aleut language family and includes three dialects: Eastern Aleut, spoken on the Eastern Aleutian, Shumagin, Fox and Pribilof Islands; Atkan, spoken on Atka and Bering islands; and the now extinct Attuan dialect.

The Pribilof Islands has the highest number of active speakers of Unangam Tunuu. Most native elders speak Aleut, but it is rare for common people to speak the language fluently.

Beginning in 1829, Aleut was written in the Cyrillic script. From 1870, the language has been written in the Latin script. An Aleut dictionary and grammar have been published, and portions of the Bible were translated into Aleut.[3]

TribesEdit

The Aleut (Unangan) dialects and tribes:[7]

- Attuan dialect and speaking tribes:

- Sasignan (in Attuan dialect)/Sasxnan (in Eastern dialect)/Sasxinas (in Western dialect) or Near Islanders: in the Near Islands (Attu, Agattu, Semichi).

- Kasakam Unangangis (in Aleut, lit. ‘Russian Aleut’) or Copper Island Aleut: in the Commander Islands of Russian Federation (Bering, Medny).

- ? Qax̂un or Rat Islanders : in the Buldir Island and Rat Islands (Kiska, Amchitka, Semisopochnoi).

- Atkan dialect or Western Aleut or Aliguutax̂ (in Aleut) and speaking tribes:

- Naahmiĝus or Delarof Islanders : in the Delarof Islands (Amatignak) and Andreanof Islands (Tanaga).

- Niiĝuĝis or Andreanof Islanders : in the Andreanof Islands (Kanaga, Adak, Atka, Amlia, Seguam).

- Eastern Aleut dialect and speaking tribes:

- Akuuĝun or Uniiĝun or Islanders of the Four Mountains : in the Islands of Four Mountains (Amukta, Kagamil).

- Qawalangin or Fox Islanders : in the Fox Islands (Umnak, Samalga, western part of Unalaska).

- Qigiiĝun or Krenitzen Islanders : in the Krenitzin Islands (eastern part of Unalaska, Akutan, Akun, Tigalda).

- Qagaan Tayaĝungin or Sanak Islanders : in the Sanak Islands (Unimak, Sanak).

- Taxtamam Tunuu dialect of Belkofski.

- Qaĝiiĝun or Shumigan Islanders : in the Shumagin Islands.

Population and distributionEdit

Map of Aleut tribes and dialects

Settlement of Aleuts in the Far Eastern Federal District by urban and rural settlements in%, 2010 census

The Aleut people historically lived throughout the Aleutian Islands, the Shumagin Islands, and the far western part of the Alaska Peninsula, with an estimated population of around 25,000 prior to European contact.[8] In the 1820s, the Russian-American Company administered a large portion of the North Pacific during a Russian-led expansion of the fur trade. They resettled many Aleut families to the Commander Islands (within the Aleutsky District of the Kamchatka Krai in Russia)[9] and to the Pribilof Islands (in Alaska). These continue to have majority-Aleut communities.[10][11]

According to the 2000 Census, 11,941 people identified as being Aleut, while 17,000 identified as having partial Aleut ancestry. Prior to sustained European contact, approximately 25,000 Aleut lived in the archipelago.[12] The Encyclopædia Britannica Online says more than 15,000 people have Aleut ancestry in the early 21st century.[8] The Aleut suffered high fatalities in the 19th and early 20th centuries from Eurasian infectious diseases to which they had no immunity. In addition, the population suffered as their customary lifestyles were disrupted. Russian traders and later Europeans married Aleut women and had families with them.[8]

HistoryEdit

After Russian contactEdit

After the arrival of Russian Orthodox missionaries in the late 18th century, many Aleuts became Christian. Of the numerous Russian Orthodox congregations in Alaska, most are majority Alaska Native or Native Alaskan in ethnicity. One of the earliest Christian martyrs in North America was Saint Peter the Aleut.

Aleuts. Ethnographic description of the peoples of the Russian Empire by Gustav-Fyodor Khristianovich Pauli (1862)

Recorded uprising against the RussiansEdit

In the 18th century, Russia promyshlenniki traders established settlements on the islands. There was high demand for the furs that the Aleut provided from hunting. In May 1784, local Aleuts revolted on Amchitka against the Russian traders. (The Russians had a small trading post there.) According to the Aleuts, in an account recorded by Japanese castaways and published in 2004, otters were decreasing year by year. The Russians paid the Aleuts less and less in goods in return for the furs they made. The Japanese learned that the Aleuts felt the situation was at crisis. The leading Aleuts negotiated with the Russians, saying they had failed to deliver enough supplies in return for furs. Nezimov, leader of the Russians, ordered two of his men, Stephanov (ステッパノ Suteppano) and Kazhimov (カジモフ Kazimofu) to kill his mistress Oniishin (オニイシン Oniishin), who was the Aleut chief’s daughter, because he doubted that Oniishin had tried to dissuade her father and other leaders from pushing for more goods.[citation needed]

After the four leaders had been killed, the Aleuts began to move from Amchitka to neighboring islands. Nezimov, leader of the Russian group, was jailed after the whole incident was reported to Russian officials.[13] (According to Hokusa bunryaku (Japanese: 北槎聞略), written by Katsuragawa Hoshū after interviewing Daikokuya Kōdayū.)

Aleut genocide against Nicoleño Tribe in CaliforniaEdit

According to Russian American Company (RAC) records translated and published in the Journal of California and Great Basin Anthropology, a 200-ton otter hunting ship named Il’mena with a mixed-nationality crew, including a majority Aleut contingent, was involved in conflict resulting in a massacre of the indigenous natives of San Nicolas Island.[14]

In 1811, to obtain more of the commercially valuable otter pelts, a party of Aleut hunters traveled to the coastal island of San Nicolas, near the Alta California-Baja California border. The locally resident Nicoleño nation sought a payment from the Aleut hunters for the large number of otters being killed in the area. Disagreement arose, turning violent; in the ensuing battle, the Aleut killed nearly all the Nicoleño men. Together with high fatalities from European diseases, the Nicoleños suffered so much from the loss of their men that by 1853, only one Nicoleñan (Juana Maria, the Lone Woman of San Nicolas) remained alive.

Internment during World War IIEdit

In June 1942, during World War II, Japanese forces occupied Kiska and Attu Islands in the western Aleutians. They later transported captive Attu Islanders to Hokkaidō, where they were held as prisoners of war in harsh conditions. Fearing a Japanese attack on other Aleutian Islands and mainland Alaska, the U.S. government evacuated hundreds more Aleuts from the western chain and the Pribilofs, placing them in internment camps in southeast Alaska, where many died of measles, influenza and other infectious diseases which spread quickly in the overcrowded dormitories. In total, about 75 died in American internment and 19 as a result of Japanese occupation.[15][16] The Aleut Restitution Act of 1988 was an attempt by Congress to compensate the survivors. On June 17, 2017, the U.S. Government formally apologized for the internment of the Unangan people and their treatment in the camps.[17]

The World War II campaign by the United States to retake Attu and Kiska was a significant component of the operations in the American and Pacific theaters.

Population declineEdit

Before major influence from outside, there were approximately 25,000 Aleuts on the archipelago. Foreign diseases, harsh treatment and disruption of aboriginal society soon reduced the population to less than one-tenth this number. The 1910 Census count showed 1,491 Aleuts. In the 2000 Census, 11,941 people identified as being Aleut; nearly 17,000 said Aleuts were among their ancestors.[18]

CultureEdit

HousingEdit

The Aleut constructed partially underground houses called barabara. According to Lillie McGarvey, a 20th century Aleut leader, barabaras keep «occupants dry from the frequent rains, warm at all times, and snugly sheltered from the high winds common to the area».[citation needed] Aleuts traditionally built houses by digging an oblong square pit in the ground, usually 50 by 20 feet (15.2 by 6.1 m) or smaller. The pit was then covered by a roof framed with driftwood, thatched with grass, then covered with earth for insulation.[19] Inside trenches were dug along the sides, with mats placed on top to keep them clean. The bedrooms were at the back of the lodge, opposite the entrance. Several families would stay in one house, with their own designated areas. Rather than fireplaces or bonfires in the middle, lanterns were hung in the house.

SubsistenceEdit

The Aleut survived by hunting and gathering. They fished for salmon, crabs, shellfish, and cod, as well as hunting sea mammals such as seal, walrus, and whales. They processed fish and sea mammals in a variety of ways: dried, smoked, or roasted. Caribou, muskoxen, deer, moose, whale, and other types of game were eaten roasted or preserved for later use. They dried berries. They were also processed as alutiqqutigaq, a mixture of berries, fat, and fish. The boiled skin and blubber of a whale is a delicacy, as is that of walrus.

Today, many Aleut continue to eat customary and locally sourced foods but also buy processed foods from Outside, which is expensive in Alaska.

EthnobotanyEdit

A full list of their ethnobotany has been compiled, with 65 documented plant uses.[20]

Visual artsEdit

Men’s chagudax, or bentwood hunting visor, Arvid Adolf Etholén collection, Museum of Cultures, Helsinki, Finland

Customary arts of the Aleut include weapon-making, building of baidarkas (special hunting boats), weaving, figurines, clothing, carving, and mask making. Men as well as women often carved ivory and wood. Nineteenth century craftsmen were famed for their ornate wooden hunting hats, which feature elaborate and colorful designs and may be trimmed with sea lion whiskers, feathers, and walrus ivory. Andrew Gronholdt of the Shumagin Islands has played a vital role in reviving the ancient art of building the chagudax or bentwood hunting visors.[21]

Aleut women sewed finely stitched, waterproof parkas from seal gut and wove fine baskets from sea-lyme grass (Elymus mollis). Some Aleut women continue to weave ryegrass baskets. Aleut arts are practiced and taught throughout the state of Alaska. As many Aleut have moved out of the islands to other parts of the state, they have taken with them the knowledge of their arts. They have also adopted new materials and methods for their art, including serigraphy, video art, and installation art.

Aleut carving, distinct in each region, has attracted traders for centuries, including early Europeans and other Alaska Natives. Historically, carving was a male art and leadership attribute whereas today it is done by both genders. Most commonly the carvings of walrus ivory and driftwood originated as part of making hunting weapons. Sculptural carvings depict local animals, such as seals and whales. Aleut sculptors also have carved human figures.[21]

The Aleut also carve walrus ivory for other uses, such as jewelry and sewing needles. Jewelry is made with designs specific to the region of each people. Each clan would have a specific style to signify their origin. Jewelry ornaments were made for piercing lips (labrum), nose, and ears, as well as for necklaces. Each woman had her own sewing needles, which she made, and that often had detailed end of animal heads.[21]

The main Aleut method of basketry was false embroidery (overlay). Strands of grasses or reeds were overlaid upon the basic weaving surface, to obtain a plastic effect. Basketry was an art reserved for women.[21] Early Aleut women created baskets and woven mats of exceptional technical quality, using only their thumbnail, grown long and then sharpened, as a tool. Today, Aleut weavers continue to produce woven grass pieces of a remarkable cloth-like texture, works of modern art with roots in ancient tradition. Birch bark, puffin feathers, and baleen are also commonly used by the Aleut in basketry. The Aleut term for grass basket is qiigam aygaaxsii. One Aleut leader recognized by the State of Alaska for her work in teaching and reviving Aleut basketry was Anfesia Shapsnikoff. Her life and accomplishments are portrayed in the book Moments Rightly Placed (1998).[22]

Masks were created to portray figures of their myths and oral history. The Atka people believed that another people lived in their land before them. They portrayed such ancients in their masks, which show anthropomorphic creatures named in their language. Knut Bergsland says their word means «like those found in caves.» Masks were generally carved from wood and were decorated with paints made from berries or other natural products. Feathers were inserted into holes carved out for extra decoration. These masks were used in ceremonies ranging from dances to praises, each with its own meaning and purpose.[21]

Tattoos and piercingsEdit

The tattoos and piercings of the Aleut people demonstrated accomplishments as well as their religious views. They believed their body art would please the spirits of the animals and make any evil go away. The body orifices were believed to be pathways for the entry of evil entities. By piercing their orifices: the nose, the mouth, and ears, they would stop evil entities, khoughkh, from entering their bodies. Body art also enhanced their beauty, social status, and spiritual authority.[23]

Before the 19th century, piercings and tattoos were very common among the Aleut people, especially among women. Piercings, such as the nose pin, were common among both men and women and were usually performed a few days after birth. The ornament was made of various materials, a piece of bark or bone, or an eagle’s feather shaft. From time to time, adult women decorated the nose pins by hanging pieces of amber and coral from strings on it; the semi-precious objects dangled down to their chins.

Piercing ears was also common. The Aleuts pierced holes around the rim of their ears with dentalium shells (tooth shells or tusk shells), bone, feathers, dried bird wings or skulls and/or amber. Materials associated with birds were important, as birds were considered to defend animals in the spirit world. A male would wear sea lion whiskers in his ears as a trophy of his expertise as a hunter. Worn for decorative reasons, and sometimes to signify social standing, reputation, and the age of the wearer, Aleuts would pierce their lower lips with walrus ivory and wear beads or bones. The individual with the most piercings held the highest respect.

Tattooing for women began when they reached physical maturity, after menstruation, at about age 20. Historically, men received their first tattoo after killing their first animal, an important rite of passage. Sometimes tattoos signaled social class. For example, the daughter of a wealthy, famous ancestor or father would work hard at her tattoos to show the accomplishments of that ancestor or father. They would sew, or prick, different designs on the chin, the side of the face, or under the nose.

Aleut clothingEdit

Replica of the sax, an Aleut coat made from bird skins and sea otter fur

The Aleut people developed in one of the harshest climates in the world, and learned to create and protect warmth. Both men and women wore parkas that extended below the knees. The women wore the skin of seal or sea-otter, and the men wore bird skin parkas, the feathers turned in or out depending on the weather. When the men were hunting on the water, they wore waterproof parkas made from seal or sea-lion guts, or the entrails of bear, walrus, or whales. Parkas had a hood that could be cinched, as could the wrist openings, so water could not get in. Men wore breeches made from the esophageal skin of seals. Children wore parkas made of downy eagle skin with tanned bird skin caps.[25] They called these parkas kameikas, meaning ‘rain gear’ in the English language.[26]

Sea-lions, harbor seals, and sea otters are the most abundant marine mammals. The men brought home the skins and prepared them by soaking them in urine and stretching them. The women undertook the sewing.[25] Preparation of the gut for clothing involved several steps. The prepared intestines were turned inside out. A bone knife was used to remove the muscle tissue and fat from the walls of the intestine. The gut was cut and stretched, and fastened to stakes to dry. It was then cut and sewn to make waterproof parkas, bags, and other receptacles.[22] On some hunting trips, the men would take several women with them. They would catch birds and prepare the carcasses and feathers for future use. They caught puffins (Lunda cirrhata, Fratercula corniculata), guillemots, and murres.[22]

It took 40 skins of tufted puffin and 60 skins of horned puffin to make one parka. A woman would need a year for all the labor to make one parka. Each lasted two years with proper care. All parkas were decorated with bird feathers, beard bristles of seal and sea-lion, beaks of sea parrots, bird claws, sea otter fur, dyed leather, and caribou hair sewn in the seams.[25]

Women made needles from the wing bones of seabirds. They made thread from the sinews of different animals and fish guts.[25] A thin strip of seal intestine could also be used, twisted to form a thread. The women grew their thumbnail extra long and sharpened it. They could split threads to make them as fine as a hair.[22] They used vermilion paint, hematite, the ink bag of the octopus, and the root of a kind of grass or vine to color the threads.[22]

GenderEdit

Russian travelers making early contact with the Aleut mention traditional tales of two-spirits or third and fourth gender people, known as ayagigux̂ (male-bodied, ‘man transformed into a woman’) and tayagigux̂ (female-bodied, ‘woman transformed into a man’), but it is unclear whether these tales are about historical individuals or spirits.[27]

Hunting technologiesEdit

BoatsEdit

Illustration of an Aleut paddling a baidarka, with an anchored Russian ship in the background, near Saint Paul Island, by Louis Choris, 1817

The interior regions of the rough, mountainous Aleutian Islands provided little in terms of natural resources for the Aleutian people. They collected stones for weapons, tools, stoves or lamps. They collected and dried grasses for their woven baskets. For everything else, the Aleuts had learned to use the fish and mammals they caught and processed to satisfy their needs.[28]

To hunt sea mammals and to travel between islands, the Aleuts became experts of sailing and navigation. While hunting, they used small watercraft called baidarkas. For regular travel, they used their large baidaras.[28]

Men rowing a baidara (large skin boat)

The baidara was a large, open, walrus-skin-covered boat. Aleut families used it when traveling among the islands. It was also used to transport goods for trade, and warriors took them to battle.[29]

The baidarka (small skin boat) was a small boat covered in sea lion skin. It was developed and used for hunting because of its sturdiness and maneuverability. The Aleut baidarka resembles that of a Yup’ik kayak, but it is hydrodynamically sleeker and faster. They made the baidarka for one or two persons only. The deck was made with a sturdy chamber, the sides of the craft were nearly vertical and the bottom was rounded. Most one-man baidarkas were about 16 feet (4.9 m) long and 20 inches (51 cm) wide, whereas a two-man was on average about 20 feet (6.1 m) long and 24 inches (61 cm) wide. It was from the baidarka that Aleut men would stand on the water to hunt from the sea.[29]

WeaponsEdit

The Aleuts hunted small sea mammals with barbed darts and harpoons slung from throwing boards. These boards gave precision as well as some extra distance to these weapons.[30]

Harpoons were also called throwing-arrows when the pointed head fit loosely into the socket of the foreshaft and the head was able to detach from the harpoon when it penetrated an animal, and remain in the wound. There were three main kinds of harpoon that the Aleuts used: a simple harpoon, with a head that kept its original position in the animal after striking, a compound (toggle-head) harpoon in which the head took a horizontal position in the animal after penetration, and the throwing-lance used to kill large animals.[30]

The simple Aleut harpoon consisted of four main parts: the wooden shaft, the bone foreshaft, and the bonehead (tip) with barbs pointed backward. The barbed head was loosely fitted into the socket of the foreshaft so that when the animal was stabbed, it pulled the head away from the rest of the harpoon. The sharp barbs penetrated with ease, but could not be pulled out. The bone tip is fastened to a length of braided twine meanwhile; the hunter held the other end of the twine in his hand.[30]

The compound harpoon was the most prevalent weapon of the Aleut people. Also known as the toggle-head spear, it was about the same size as the simple harpoon and used to hunt the same animals, however, this harpoon provided a more efficient and lethal weapon. This harpoon separated into four parts. The longest part was the shaft with the thicker stalk closer to the tip of the harpoon. The shaft was fitted into the socket of the fore shaft and a bone ring was then placed over the joint to hold the two pieces together, as well as, protecting the wooden shaft from splitting. Connected to the fore shaft of the harpoon is the toggle head spear tip. This tip was made of two sub shafts that break apart on impact with an animal. The upper sub shaft held the razor stone head and attached to the lower sub shaft with a small braided twine loop. Once the tip penetrates the animal the upper sub head broke off from the rest of the shaft, however, since it was still connected with the braided loop it rotated the head into a horizontal position inside the animal’s body so that it could not get away from the hunter.[30]

The throwing lance may be distinguished from a harpoon because all its pieces are fixed and immovable. A lance was a weapon of war and it was also used to kill large marine animals after it has already been harpooned. The throwing lance usually consisted of three parts: a wooden shaft, a bone ring or belt, and the compound head that was made with a barbed bonehead and a stone tip. The length of the compound head was equivalent to the distance between the planes of a man’s chest to his back. The lance would penetrate the chest and pass through the chest cavity and exit from the back. The bone ring was designed to break after impact so that the shaft could be used again for another kill.[30]

Burial practicesEdit

They buried their dead ancestors near the village. Archeologists have found many different types of burials, dating from a variety of periods, in the Aleutian Islands. The Aleut developed a style of burials that were accommodated to local conditions, and honored the dead. They have had four main types of burials: umqan, cave, above-ground sarcophagi, and burials connected to communal houses.

Umqan burials are the most widely known type of mortuary practice found in the Aleutian Islands. The people created burial mounds, that tend to be located on the edge of a bluff. They placed stone and earth over the mound to protect and mark it. Such mounds were first excavated by archeologists in 1972 on Southwestern Unmak Island, and dated to the early contact period. Researchers have found a prevalence of these umqan burials, and concluded it is a regional mortuary practice. It may be considered a pan-Aleutian mortuary practice.[31]

Cave burials have been found throughout the eastern Aleutian Islands. The human remains are buried in shallow graves at the rear of the cave. These caves tend to be next to middens and near villages. Some grave goods have been found in the caves associated with such burials. For example, a deconstructed boat was found in a burial cave on Kanaga Island. There were no other major finds of grave goods in the vicinity.[32]

Throughout the Aleutian Islands, gravesites have been found that are above-ground sarcophagi. These sarcophagi are left exposed, with no attempt to bury the dead in the ground. These burials tend to be isolated and limited to the remains of adult males, which may indicate a specific ritual practice. In the Near Islands, isolated graves have also been found with the remains, and not just the sarcophagus, left exposed on the surface.[33] This way of erecting sarcophagi above ground is not as common as umqan and cave burials, but it is still widespread.

Another type of practice has been to bury remains in areas next to the communal houses of the settlement.[33] Human remains are abundant in such sites. They indicate a pattern of burying the dead within the main activity areas of the settlement. These burials consist of small pits adjacent to the houses and scattered around them.[33] In these instances, mass graves are common for women and children.[33] This type of mortuary practice has been mainly found in the Near Islands.

In addition to these four main types, other kinds of burials have been found in the Aleutian Islands. These more isolated examples in include mummification, private burial houses, abandoned houses, etc.[33] To date, such examples are not considered to be part of a larger, unifying cultural practice. The findings discussed represent only the sites that have been excavated.

The variety of mortuary practices mostly did not include the ritual of including extensive grave goods, as has been found in other cultures. The remains so far have been mainly found with other human and faunal remains.[33] The addition of objects to «accompany» the dead is rare.[32] Archaeologists have been trying to dissect the absence of grave goods, but their findings have been ambiguous and do not really help the academic community to understand these practices more.

Not much information is known about the ritual parts of burying the dead. Archeologists and anthropologists have not found much evidence related to burial rituals.[31] This lack of ritual evidence could hint at either no ritualized ceremony, or one that has not yet been revealed in the archaeological record. As a result, archaeologists cannot decipher the context to understand exactly why a certain type of burial was used in particular cases.

Notable AleutsEdit

- John Hoover (1919–2011), sculptor

- Carl E. Moses (1929–2014) businessman, state representative, who served from 1965 to 1973 as both a Republican and Democrat,

- Jacob Netsvetov (1802–1864), Russian Orthodox saint and priest

- Sergie Sovoroff (1901–1989), educator, iqya-x (model sea kayak) builder

- Eve Tuck, academic, indigenous studies

- Peter the Aleut (1800 — 1815), Russian Orthodox saint and martyr

In popular cultureEdit

In Snow Crash, a science fiction novel by American writer Neal Stephenson, a central character named Raven is portrayed as an Aleut with incredible toughness and hunting skill.[34] The story is about revenge due in part to perceived mistreatment of the Aleut.

Alaska by James A. Michener.

See alsoEdit

- Adamagan

- Aleutian Islands

- Aleutian tradition

- Alutiiq

- Indigenous Amerindian genetics

- Maritime Fur Trade

- Sadlermiut

- Shamanism among Alaska Natives

- Unangan Aleut

- List of Native American peoples in the United States

NotesEdit

- ^ The singular form is Unangax̂. The Cyrillic spelling of Unangan and Unangas are Унаӈан and Унаӈас, respectively.[5]

ReferencesEdit

- ^ «Aleut alone». factfinder.census.gov. US Census Bureau. Archived from the original on February 14, 2020. Retrieved February 20, 2018.

- ^ «ВПН-2010». gks.ru. Archived from the original on April 24, 2012.

- ^ a b c «Aleut.» Ethnologue. Retrieved February 3, 2014.

- ^ Jones, Daniel (2011). Roach, Peter; Setter, Jane; Esling, John (eds.). Cambridge English Pronouncing Dictionary (18th ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-15255-6.

- ^ «Unangam Tunuu/Aleut,» Archived February 9, 2018, at the Wayback Machine Alaska Native Language Center.

- ^ Marcus Lepola (2010). «The Aleuts and the Pacific Eskimo in the colonial economy of Russian Alaska in the mid 19th century» (PDF). Arctic & Antarctic International Journal of Circumpolar Socio-Cultural. 4.

- ^ Unangam Language Pre-contact Tribes and Dialects by Knut Bergland and Moses L. Dirks

- ^ a b c «Aleut People». Encyclopædia Britannica. 2011.

- ^ Lyapunova, R.G. (1987) Aleuts: Noted on their ethnological history (in Russian)

- ^ Corbett, H.D.; Swibold, S. M (2000). «Endangered people of the Arctic. Struggle to Survive». The Aleuts of the Pribilof Islands, Alaska. Milton M.R. Freeman.

- ^ Bonner, W. N. (1982) Seals and Man: A Study of Interactions, Seattle: University of Washington Press

- ^ «Alaskan People: Aleut Native Tribe». alaskannature.com.

- ^ Yamashita, Tsuneo. Daikokuya Kodayu(Japanese), 2004. Iwanami, Japan ISBN 4-00-430879-8

- ^ Morris, Susan L.Farris, Glenn J.Schwartz, Steven J.Wender, Irina Vladi L.Dralyuk, Boris (2014). «Murder, Massacre, and Mayhem on the California Coast, 1814 –1815: Newly Translated Russian American Company Documents Reveal Company Concern Over Violent Clashes» (PDF). Journal of California and Great Basin Anthropology. 34 (1): 81–100. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 9, 2022.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Madden, Ryan (2000). «‘The Government’s Industry’: Alaska Natives and Pribilof Sealing during World War II». Pacific Northwest Quarterly. 91 (4): 202–209. JSTOR 40492595.

- ^ «Evacuation and Internment, 1942–1945 – Aleutian World War II National Historic Area (U.S. National Park Service)». nps.gov.

- ^ US apologizes for WWII internment of Alaska’s Unangan people. The Associated Press via Miami Herald. June 17, 2017

- ^ «The American Indian and Alaska Native Population: 2000 Table 5» (PDF). census.gov. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 9, 2022.

- ^ Cook, James (1999). The Voyages of Captain James Cook. Hertfordshire, UK: Wordsworth Editions. p. 377 ISBN 978-1-84022-100-8.

- ^ «BRIT — Native American Ethnobotany Database». naeb.brit.org. Archived from the original on December 24, 2019. Retrieved September 6, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e Black, Lydia (2003). Aleut Art Unangam Aguqaadangin. Anchorage, AK: Aleutian/Pribilof Islands Association.

- ^ a b c d e Turner, M. Lucien. (2008) An Aleutian Ethnography. Ed. L. Raymond Hudson. Fairbanks: University of Alaska Press. pp. 70–71. ISBN 9781602230286

- ^ Osborn, Kevin (1990). The Peoples of the Arctic. New York : Chelsea House Publishers. p. 52. ISBN 9780877548768

- ^ «Kamleika». Google Arts & Culture. Retrieved January 16, 2019.

- ^ a b c d Gross, J. Joseph and Khera, Sigrid (1980). Ethnohistory of the Aleuts. Fairbanks: Department of Anthropology University of Alaska. pp. 32–34

- ^ «Home». Aleut Corporation. Retrieved December 18, 2022.

- ^ Murray, Stephen O. (2002) Pacific Homosexualities. Writers Club Press. p. 206. ISBN 9780595227853

- ^ a b Antonson, Joan (1984). Alaska’s Heritage. Anchorage: The Alaska Historical Commission. pp. 85–95.

- ^ a b Durham, Bill (1960). Canoes and Kayaks of Western America. Seattle: Copper Canoe Press. pp. 11–20.

- ^ a b c d e Jochelson, Waldemar (1925). Archaeological Investigations in the Aleutian Islands. Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press. p. 145.

- ^ a b Veltre, Douglas W. (2001) «Korovinski: Archaeological and Ethnohistorical Investigations of a Pre- and Post-Contact Aleut and Russian Settlement on Atka Island». In Archaeology of the Aleut Zone of Alaska, edited by D. Dumond, pp. 251–266. University of Oregon Anthropological Papers, no. 58. University of Oregon, Eugene.

- ^ a b Nelson, Willis H.; Barnett, Frank (1955). «A Burial Cave on Kanaga Island, Aleutian Islands». American Antiquity. 20 (4): 387–392. doi:10.2307/277079. JSTOR 277079. S2CID 162015286.

- ^ a b c d e f Corbett, Debra G. (2001) «Prehistoric Village Organization in the Western Aleutians». In Archaeology of the Aleut Zone of Alaska, edited by D. Dumond, pp. 251–266. University of Oregon Anthropological Papepers, no. 58. University of Oregon, Eugene.

- ^ «Raven a.k.a. Dmitri Ravinoff in Snow Crash». shmoop.com.

Further readingEdit

- Krutak, Lars (April 24, 2011). «Tattooing and Piercing Among the Alaskan Aleut» (PDF). Quarterly Journal of the Association of Professional Piercers 44 (2008): 22. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 28, 2011.

- Lee, Molly, Angela J. Linn, and Chase Hensel. Not Just a Pretty Face: Dolls and Human Figurines in Alaska Native Cultures. Fairbanks, AK: University of Alaska, 2006. Print.

- Black, Lydia T. Aleut Art: Unangam Aguqaadangin. Anchorage, Alaska: Aleutian/Pribilof Islands Association, 2005.

- Jochelson, Waldemar. History, Ethnology, and Anthropology of the Aleut. Washington: Carnegie institution of Washington, 1933.

- Jochelson, Waldemar, Bergsland, Knut (Editor) & Dirks, Moses (Editor). Unangam Ungiikangin Kayux Tunusangin = Unangam Uniikangis ama Tunuzangis = Aleut Tales and Narratives. Fairbanks, Alaska: Alaska Native Language Center, University of Alaska, Fairbanks, 1990.ISBN 978-1-55500-036-3.

- Kohlhoff, Dean. When the Wind Was a River Aleut Evacuation in World War II. Seattle: University of Washington Press in association with Aleutian/Pribilof Islands Association, Anchorage, 1995. ISBN 0-295-97403-6

- Madden, Ryan Howard. «An enforced odyssey: The relocation and internment of Aleuts during World War II» (PhD thesis U of New Hampshire, Durham, 1993) online

- Murray, Martha G., and Peter L. Corey. Aleut Weavers. Juneau, AK: Alaska State Museums, Division of Libraries, Archives and Museums, 1997.

- Reedy-Maschner, Katherine. «Aleut Identities : Tradition and Modernity in an Indigenous Fishery». Montréal, Quebec: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2010. ISBN 978-0773537484

- Veltre, Douglas W. Aleut Unangax̂ Ethnobotany An Annotated Bibliography. Akureyri, Iceland: CAFF International Secretariat, 2006. ISBN 9979-9778-0-9

- «Aleutian World War II.» National Park Service.

External linksEdit

Wikimedia Commons has media related to Aleut.

- Aleut Corporation

- Aleut Management Services

- Aleutian Pribilof Island Association

- Qawalangin Tribe of Unalaska

- Museum of the Aleutians

- Unalaska Communities of Memory Project Jukebox Archived June 24, 2010, at the Wayback Machine

- Aleut International Association

- A Grammar of Fox Island Aleutian Manuscript at Dartmouth College Library

- Aleutian Pribilof Island Community Development Association

Преобразуйте, если это необходимо, слово «MEAN» так, чтобы оно грамматически соответствовало содержанию текста.

The name of Alaska

Do you know the origin of the place name Alaska? The name Alaska comes from the Aleut word alaxsxaq, __________________ “object toward which the action of the sea is directed” – that is, the mainland.

1

Преобразуйте, если это необходимо, слово FORM так, чтобы оно грамматически соответствовало содержанию текста.

It is also known as Alyeska, the “great land”, an Aleut word __________________ from the same root.

Источники:

Демонстрационная версия ЕГЭ—2016 по английскому языку;

Демонстрационная версия ЕГЭ—2017 по английскому языку;

Демонстрационная версия ЕГЭ—2018 по английскому языку.

2

Преобразуйте, если это необходимо, слово CONSIDER так, чтобы оно грамматически соответствовало содержанию текста.

Its nicknames are the Land of the Midnight Sun and America’s Last Frontier. Its first nicknames were “Seward’s folly” and

“Seward’s icebox” to laugh at the secretary of state who negotiated the purchase of Alaska from Russia, which __________________ foolish at the time.

Источники:

Демонстрационная версия ЕГЭ—2016 по английскому языку;

Демонстрационная версия ЕГЭ—2017 по английскому языку;

Демонстрационная версия ЕГЭ—2018 по английскому языку.

3

Преобразуйте, если это необходимо, слово LOCATE так, чтобы оно грамматически соответствовало содержанию текста.

A landmark for the new millennium

Have you seen the photos of the London Eye? The London Eye is a giant observation wheel __________________ in the Jubilee Gardens on the South Bank of the river Thames.

Источники:

Демонстрационная версия ЕГЭ—2016 по английскому языку;

Демонстрационная версия ЕГЭ—2017 по английскому языку;

Демонстрационная версия ЕГЭ—2018 по английскому языку.

4

Преобразуйте, если это необходимо, слово DESIGN так, чтобы оно грамматически соответствовало содержанию текста.

The structure __________________ by the architectural team of David Marks and Julia Barfield, husband and wife.

Источники:

Демонстрационная версия ЕГЭ—2016 по английскому языку;

Демонстрационная версия ЕГЭ—2017 по английскому языку;

Демонстрационная версия ЕГЭ—2018 по английскому языку.

5

Преобразуйте, если это необходимо, слово WIN так, чтобы оно грамматически соответствовало содержанию текста.

They submitted their idea for a large observation wheel as part of a competition to design a landmark for the new millennium. None of the entrants __________________the competition.

Источники:

Демонстрационная версия ЕГЭ—2016 по английскому языку;

Демонстрационная версия ЕГЭ—2017 по английскому языку;

Демонстрационная версия ЕГЭ—2018 по английскому языку.

6

Задания Д25 № 3199

i

Преобразуйте, если это необходимо, слово THEY так, чтобы оно грамматически соответствовало содержанию текста.

However, the couple pressed on and eventually got the backing of British Airways, who sponsored __________________ project.

Источники:

Демонстрационная версия ЕГЭ—2016 по английскому языку;

Демонстрационная версия ЕГЭ—2017 по английскому языку;

Демонстрационная версия ЕГЭ—2018 по английскому языку.

7

Образуйте от слова ABSOLUTE однокоренное слово так, чтобы оно грамматически и лексически соответствовало содержанию текста.

Pronunciation is important

Some learners of English think that pronunciation is not very important. That is __________________ wrong.

Источники:

Демонстрационная версия ЕГЭ—2016 по английскому языку;

Демонстрационная версия ЕГЭ—2017 по английскому языку.

8

Образуйте от слова EXTEND однокоренное слово так, чтобы оно грамматически и лексически соответствовало содержанию текста.

Even if you have an acceptable grasp of the English language, with good grammar and an __________________ vocabulary, native English speakers may find you very difficult to understand you if you don’t work on your pronunciation.

Источник: Демонстрационная версия ЕГЭ—2016 по английскому языку

9

Образуйте от слова ESSENCE однокоренное слово так, чтобы оно грамматически и лексически соответствовало содержанию текста.

Correct, clear pronunciation is __________________ if you really want to improve your level of English.

Источники:

Демонстрационная версия ЕГЭ—2016 по английскому языку;

Демонстрационная версия ЕГЭ—2017 по английскому языку.

10

Образуйте от слова FAMILIAR однокоренное слово так, чтобы оно грамматически и лексически соответствовало содержанию текста.

Pay particular attention to any sounds that you are __________________ with or that do not exist in your native tongue.

Источники:

Демонстрационная версия ЕГЭ—2016 по английскому языку;

Демонстрационная версия ЕГЭ—2017 по английскому языку.

11

Образуйте от слова RUSSIA однокоренное слово так, чтобы оно грамматически и лексически соответствовало содержанию текста.

For example, __________________ have difficulty pronouncing the “th” sound, as it does not exist in their native language.

Источники:

Демонстрационная версия ЕГЭ—2016 по английскому языку;

Демонстрационная версия ЕГЭ—2017 по английскому языку.

Источники:

Демонстрационная версия ЕГЭ—2016 по английскому языку;

Демонстрационная версия ЕГЭ—2017 по английскому языку;

Демонстрационная версия ЕГЭ—2018 по английскому языку.

| Aleut | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Traditional Aleut dress |

||||||

| Total population | ||||||

| 17,000 to 18,000 | ||||||

| Regions with significant populations | ||||||

|

||||||

| Languages | ||||||

| English, Russian, Aleut | ||||||

| Religions | ||||||

| Christianity, Shamanism | ||||||

| Related ethnic groups | ||||||

| Inuit, Yupiks |

The Aleuts (Unangax, Unangan or Unanga) are the indigenous people of the Aleutian Islands of Alaska, United States and Kamchatka Oblast, Russia. They are related to the Inuit and Yupik people. The homeland of the Aleuts includes the Aleutian Islands, the Pribilof Islands, the Shumagin Islands, and the far western part of the Alaskan Peninsula.

They were skilled at hunting and fishing in this harsh climate, skills that were exploited by Russian fur traders after their arrival around 1750. They received assistance and support from the Russian Orthodox missionaries subsequently and became closely aligned with Orthodox practices and beliefs. Despite this, an estimated 90 percent of the population died during the years of Russian fur trade. The tribe has nonetheless made a recovery, and their wisdom and perseverance are qualities that allow them to work with others in the process of building a world of peace.

Name

The Aleut (pronounced al-ee-oot) people were so named by Russian fur traders during the Russian fur trade period in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Their original name was Unangan, meaning «coastal people.”

History

The Aleut trace permanent settlement to about 8,000 years ago in the Aleutian archipelago that stretches over 1,300 miles between Alaska and Siberia. Anthropologists are not certain of their exact origins (Siberia or Subarctic) but most believe they arrived later than the more southern tribes (around 4,000 years ago). Two cultures developed: the Kodiak (circa 2,500 B.C.E.) and Aleutian (circa 2,000 B.C.E.).[1]

The Aleuts’ skill at hunting and surviving in the hard environment made them valuable and later exploited by Russian fur traders after their arrival in 1750.[2] Russian Orthodox missionaries referred to the austere environment as “the place that God forgot.” [3]

Within fifty years after Russian contact, the population of the Aleut was 12,000 to 15,000 people. At the end of the twentieth century, it was 2,000.[4] Eighty percent of the Aleut population had died through violence and European diseases, against which they had no defense. There was, however, a counterbalancing force that came from the missionary work of the Russian Orthodox Church. The priests, who were educated men, took great interest in preserving the language and lifestyle of the indigenous people of Alaska. One of the earliest Christian martyrs in North America was Saint Peter the Aleut.

Fur trade first annihilated the sea otter and then focused on the massive exploitation of fur seals. Aleutian men were transported to areas where they were needed on a seasonal basis. The Pribilof Islands (named for Russian navigator Gavriil Pribilof’s discovery in 1786) became the primary place where seals were harvested en masse. The Aleuts faired well during this period as Russian citizens but rapidly lost status after the American purchase of Alaska in 1867. Aleuts lost their rights and endured injustices.

In 1942, Japanese forces occupied Attu and Kiska Islands in the western Aleutians, and later transported captive Attu Islanders to Hokkaidō, where they were held as POWs. Hundreds more Aleuts from the western chain and the Pribilofs were evacuated by the United States government during World War II and placed in internment camps in southeast Alaska, where many died.

It was not until the mid-1960s that the Aleuts were given American citizenship. In 1983, the U.S. government eliminated all financial allocations to the inhabitants of the Pribilofs. A trust fund of 20 million dollars was approved by Congress to initiate alternative sources of income such as fishing. This proved very successful as the Pribilofs became a primary point for international fishing vessels and processing plants. The Aleut Restitution Act of 1988 was an attempt by Congress to compensate survivors of the internment camps. By the late 1990s, the impact of environmental changes began to cast shadows over the economy of the North Sea region.

Culture

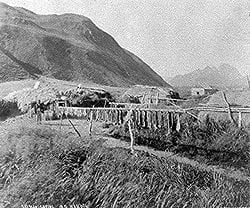

Salmon drying. Aleut village, Old Harbor, Alaska. Photographed by N. B. Miller, 1889

Aleut settlements were located by the coast, usually on bays with fresh water nearby to ensure a good salmon stream. They also chose locations with an elevated lookout and an escape route in case of attack by enemies.[5]

Aleuts constructed «barabaras» (or ulax), partially underground houses which protected them from the harsh climate. The roof of a barabara was generally made from sod layered over a frame of wood or whalebone, and contained a roof doorway for entry. The entrance typically had a little wind envelope or «Arctic entry» to prevent cold wind, rain or snow from blowing into the main room and cooling it off. There was usually a small hole in the ceiling from which the smoke from the fire escaped.[6]

Fishing and hunting and gathering provided the Aleuts with food. Salmon, seal, walrus, whale, crabs, shellfish, and cod were all caught and dried, smoked or roasted. Caribou, deer, moose, and other types of game were eaten roasted or preserved. Berries were dried or made into alutiqqutigaq, a mixture of berries, fat, and fish. The Aleut used skin covered kayaks (or iqyax) to hunt marine mammals.[7] They used locally available materials, such as driftwood and stone, to make tools and weapons.[5]

Language

The Aleut language is in the Eskimo-Aleut languages family. It is divided at Atka Island into the Eastern and the Western dialects.[7] Their language is related to the Inuit and Yupik languages spoken by the Eskimo. It has no known wider affiliation, but supporters of the Nostratic hypothesis sometimes include it as Nostratic.

Ivan Veniaminov began to develop a writing system in 1824 for the Aleut language so that educational and religious materials could be translated. Continuous work has taken place through the work of dedicated linguists through the twentieth century. Knut Bergsland from 1950 until his death in 1998 worked with Aleut speakers and produced a comprehensive Aleut dictionary in 1994, and in 1997 a detailed reference grammar book.[7]

A «barabara» (Aleut: ulax), the traditional Aleut winter house.

Prior to Russian contact, Aleut society was a ranked system of heredity classes. There were positions similar to nobles, commoners, and slaves in the Western world. The highest ranking were given special places in the long house as well as burial sites. The east was important as the place where the Creator, Agugux, resided, thus the best place to be located.[5]

Religion

Aleut men honored creatures of the sea and honored them through the ornamentation on their hunting costumes. Hunting was the lifeline of the Aleut people. Animals, fish, and birds were revered and considered to have souls. Rituals were sometimes performed to release the hunted animal’s soul. Newborn babies were named after someone who had died in order that the deceased person could live on in the child. There was also a belief in the soul going to a land in the sea or sky. Wooden masks of animals were often used in ritual dances and story telling.

Shamans were very important. They were able to go into a trance and receive messages from spirits to help with the hunting or with healing. They also could perform evil actions against others. Important deities were Sea Woman (Sedna) in charge of sea animals, Aningaaq in charge of the sun, and Sila in charge of the air.

Clothing

Parka (Kamleika) Aleutian Islands. Aleut hood ceremonial kamleika. Waterproof overdress of sea mammal gut. Panel at chin is dyed gut applique with red wool embroidery. Fur and dyed gut applique trim the cuffs and hem. Human hair decorates the seams. Worn by a person of high rank or by a shaman when making contact wth the spirit world.

Imitation of the sax, a traditional Aleut coat made from bird skins and sea otter fur.

The Aleut people live in one of the harshest parts of the world. Both men and women wore parkas (Kamleika) the come down below the knees to provide adequate protection. The women’s parkas were made of skin of seal or sea-otter skin and the men wore bird skin parkas that had the feathers inside and out depending on the weather. When the men were hunting on the water they wore waterproof hooded parkas made from seal or sea-lion guts, or the entrails of bear, walrus, and whales. Children wore parkas made of downy eagle skin with tanned bird skin caps.[8]

One parka took a year to make and would last two years with proper care. All parkas were decorated with bird feathers, beard bristles of seal and sea-lion, beaks of sea parrots, bird claws, sea otter fur, dyed leather, and caribou hair sewn in the seams. Colored threads made of sinews of different animals and fish guts were also used for decoration.[8] The threads were dyed different colors using vermilion paint, hematite, the ink bag of the octopus, and the roots of grasses.[9]

Arts

Weapon-making, building of baidarkas (special hunting boats), and weaving are some of the traditional arts of the Aleuts. Nineteenth-century craftsmen were famed for their ornate wooden hunting hats, which feature elaborate and colorful designs and may be trimmed with sea lion whiskers, feathers, and ivory. Aleut seamstresses created finely stitched waterproof parkas from seal gut, and some women still master the skill of weaving fine baskets from rye and beach grass. Aleut men wore wooden hunting hats. The length of the visor indicated rank.

Aleut carvings are distinct in each region and have attracted traders for centuries. Most commonly the carvings of ivory and wood were for the purpose of hunting weapons. Other times the carvings were created to depict commonly seen animals, such as seals, whales, and even people.[10]

The Aleuts also use ivory in jewelry and custom made sewing needles often with a detailed end of carved animal heads. Jewelry is worn as lip piercings, nose piercings, necklaces, ear piercings, and piercings through the flesh under the bottom lip.[10]

Aleut basketry is some of the finest in the world, the continuum of a craft dating back to prehistoric times and carried through to the present. Early Aleut women created baskets and woven mats of exceptional technical quality using only an elongated and sharpened thumbnail as tool. Today Aleut weavers continue to produce woven pieces of a remarkable cloth-like texture, works of modern art with roots in ancient tradition. The Aleut word for grass basket is qiigam aygaaxsii.

Masks are full of meaning in the Aleut culture. They may represent creatures described in Aleut language, translated by Knut Bergsland as “like those found in caves.” Masks were generally carved from wood and were decorated with paints made from berries or other earthly products. Feathers were also inserted into holes carved out for extra decoration. These masks were used from ceremonies to dances to praises, each with its own meaning and purpose.[10]

Contemporary Issues

Following a devastating oil spill in 1996, the Aleut could not deny that life was again changing for them and future generations. A revival of interest in Aleut culture has subsequently been initiated. Leaders have worked to help the Aleut youth understand their historic relationship with the environment and to seek opportunities to work on behalf of the environment for the future. In 1998, Aleut leader, Aquilina Bourdukofsky wrote: “I believe we exist generationally. Would we be as strong as we are if we didn’t go through the hardships, the slavery? It’s powerful to hear the strength of our people – that’s what held them together in the past and today.”[2]

Notes

- ↑ Barry Pritzker, A Native American Encyclopedia (New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2000, ISBN 0195138775).

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Helen D. Corbett and Susanne M. Swibold, The Aleuts of the Pribilof Islands, Alaska Retrieved November 3, 2011. Reproduced with permission from Milton M.R. Freeman (ed.), Endangered people of the Arctic: Struggles to Survive and Thrive (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 2000, ISBN 978-0313306495).

- ↑ Michael Oleksa, Alaskan Missionary Spirituality, (New York, NY: Paulist Press, 1987, ISBN 0809103869).

- ↑ Margaret Lantis, Handbook of North American Indians Volume 5 Arctic David Damas (ed.) (Washington DC: Smithsonian Institute Press, 1984, ISBN 0874741858), 163.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Lydia T. Black and R. G. Liapunova, Aleut Arctic Studies Center. Retrieved November 3, 2011.

- ↑ Peter Nabokov and Robert Easton, Native American Architecture. (New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 1989, ISBN 0195037812), 205.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 Aleutian Pribilof Island Community Development Association, Aleut Culture Retrieved November 3, 2011.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 J. Joseph Gross and Sigrid Khera, Ethnohistory of the Aleuts (Fairbanks, AK: University of Alaska, 1980), 33-34.

- ↑ Lucien Turner, An Aleutian Ethnography Raymond L. Hudson (ed.) (Fairbanks, AK: University of Alaska Press, 2010, ISBN 978-1602230392), 71.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 Lydia Black, Aleut Art Unangam Aguqaadangin (Anchorage, AK: Aleutian/Pribilof Islands Association, 2003, ISBN 978-1578642144).

References

ISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Bergsland, Knut. Aleut Dictionary: Unangam Tundguaii. Fairbanks, AK: Alaska Native Language Center, 1994. ISBN 978-1555000479

- Bergsland, Knut. Aleut Grammar: Unangam Tunuganaan Achixaasix. Fairbanks, AK: Alaska Native Language Center, 1997. ISBN 978-1555000646

- Black, Lydia. Aleut Art Unangam Aguqaadangin. Anchorage, AK: Aleutian/Pribilof Islands Association, 2003. ISBN 978-1578642144

- Damas, David (ed.). Handbook of North American Indians Volume 5 Arctic. Washington DC: Smithsonian Institute Press, 1984. ISBN 0874741858

- Freeman, Milton M.R. (ed.). Endangered people of the Arctic: Struggles to Survive and Thrive. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 2000. ISBN 978-0313306495

- Lantis, Margaret. Ethnohistory in Southwestern Alaska and the Southern Yukon. Lexington, KY: University of Kentucky Press, 1970. ISBN 081311215X

- Nabokov, Peter, and Robert Easton. Native American Architecture. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 1989. ISBN 0195037812

- Oleksa, Michael. Alaskan Missionary Spirituality. New York, NY: Paulist Press. 1987. ISBN 0809103869

- Pritzker, Barry. A Native American Encyclopedia New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2000. ISBN 0195138775

- Turner, Lucien. An Aleutian Ethnography Raymond L. Hudson (ed.). Fairbanks, AK: University of Alaska Press, 2010. ISBN 978-1602230392

External links

All links retrieved May 15, 2021.

- The AMIQ Institute — a research project documenting the Pribilof Islands and their inhabitants.

- The Aleut Foundation

- Aleutian Pribilof Islands Association

- Museum of the Aleutians

- Aleutian Pribilof Island Community Development Association

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article

in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

- Aleut history

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

- History of «Aleut»

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.