Words of the Year

Nominations for Words of the Year can be submitted all year long to woty@americandialect.org. All previous winners are listed here.

- 2022 Word of the Year is “-ussy” January 6, 2023

- Nominations for Words of the Year 2022 January 6, 2023

- Now Accepting Nominations for 2022 Word of the Year December 9, 2022

- 2021 Word of the Year is “Insurrection” January 7, 2022

- Nominations for Words of the Year 2021 January 7, 2022

- Now Accepting 2021 Words-of-the-Year Nominations December 22, 2021

- 2020 Word of the Year is “Covid” December 17, 2020

- Nominations for Words of the Year 2020 December 17, 2020

- Register for the free 2020 Virtual Word-of-the-Year Livestream Vote November 17, 2020

- 2019 Word of the Year is “(My) Pronouns,” Word of the Decade is Singular “They” January 3, 2020

- Nominations for Words of the Year 2019 and Words of the Decade 2010-2019 January 3, 2020

- Schedule for Annual Conference in New Orleans, Jan. 2–5, 2020 November 24, 2019

- “Tender-age shelter” is 2018 American Dialect Society word of the year January 4, 2019

- Nominations for 2018 Word of the Year posted January 4, 2019

- Call for Papers for 2019 American Dialect Society Annual Meeting in New York City, January 3-6 April 19, 2018

- “Fake news” is 2017 American Dialect Society word of the year January 5, 2018

- Nominations for 2017 Word of the Year posted January 5, 2018

- Nominations now being accepted for 2017 words of the year December 20, 2017

- “Dumpster fire” is 2016 American Dialect Society word of the year January 6, 2017

- Nominations for 2016 Word of the Year posted January 6, 2017

- Nominations now being accepted for 2016 words of the year December 12, 2016

- 2015 Word of the Year is singular “they” January 8, 2016

- Nominations for 2015 Word of the Year posted January 8, 2016

- The 2015 word-of-the-year candidates so far… December 29, 2015

- 2014 Word of the Year is “#blacklivesmatter” January 9, 2015

- UPDATED Schedule for Annual Meeting in Portland, Ore., Jan. 8-11, 2015 January 9, 2015

- Nominations for 2014 Word of the Year posted January 9, 2015

- “Because” is the 2013 Word of the Year January 3, 2014

- Nominations for 2013 Word of the Year posted January 2, 2014

- 2013 Word of the Year Candidates December 28, 2013

- “Hashtag” is the 2012 Word of the Year January 4, 2013

- Nominations for 2012 Word of the Year posted January 3, 2013

- UPDATED: Schedule of the 2013 American Dialect Society Annual Meeting in Boston January 3, 2013

- What’s Your 2012 Word of the Year? December 14, 2012

- “Occupy” is the 2011 Word of the Year January 6, 2012

- Nominations for 2011 word of the year posted January 5, 2012

- Fodder for the 2011 Words of the Year Vote January 4, 2012

- Schedule and Abstracts for 2012 Annual Meeting in Portland (Updated) December 6, 2011

- What’s Your Word of the Year? November 30, 2011

- Call for papers: American Dialect Society Annual Meeting 2012, Portland April 27, 2011

- “App” voted 2010 word of the year by the American Dialect Society (UPDATED) January 8, 2011

- Nominations for 2010 word of the year posted January 7, 2011

- UPDATED: American Dialect Society Annual Meeting 2011 in Pittsburgh, January 6–8 January 3, 2011

- Now accepting nominations for the 2010 word of the year December 20, 2010

- UPDATED: American Dialect Society Annual Meeting 2011 in Pittsburgh, January 6–8 November 3, 2010

- 2009 Word of the Year is “tweet”; Word of the Decade is “google” January 8, 2010

- Word of the year 2009 and word of the decade 2000-2009 nominations finalized; voting January 8 January 7, 2010

- Early nominations received for the 2009 word of the year vote December 21, 2009

- Now accepting nominations for the 2009 “word of the year” and the 2000-9 “word of the decade” November 15, 2009

- American Dialect Society Annual Meeting 2010 Baltimore, January 7–9 (UPDATED) November 10, 2009

- Word of the Decade Nominations Open for 2000-2009 January 16, 2009

- American Dialect Society 2008 Word of the Year is “Bailout” January 9, 2009

- UPDATED: Early nominations for the grandaddy of all 2008 word-of-the-year votes are released December 29, 2008

- American Dialect Society seeks 2008 word-of-the-year nominations November 20, 2008

- “Subprime” voted 2007 word of the year January 4, 2008

- 2007 words of the year nominations posted January 3, 2008

- Early Word of the Year Nominations for 2007 December 18, 2007

- Nominate your 2007 words of the year November 17, 2007

- “Plutoed” Voted 2006 Word of the Year January 5, 2007

- 2006 Words of the Year Nominations Are Complete; Voting Fri., Jan. 5 January 5, 2007

- More word-of-the-year nominations January 3, 2007

- Word of the Year Nominations Being Accepted December 24, 2006

- Words of the Year Nominating Commences December 13, 2006

- Updated Program and Sked for 2007 Conference December 11, 2006

- Truthiness Voted 2005 Word of the Year January 6, 2006

- 2005 Word of the Year Nominations January 6, 2006

- Words of the Year 2005 Preview December 21, 2005

- 2004 Words of the Year January 7, 2005

- 2004 Words of the Year Nominations Received December 28, 2004

- 2004 Words of the Year Vote scheduled December 27, 2004

- 2003 Words of the Year January 13, 2004

- 2002 Words of the Year January 13, 2003

- 2001 Words of the Year January 13, 2002

- 2001 Words of the Year Vote Anticipated December 19, 2001

- 2000 Words of the Year January 13, 2001

- 1999 Words of the Year, Word of the 1990s, Word of the 20th Century, Word of the Millennium January 13, 2000

- 1998 Words of the Year January 13, 1999

Hyatt Regency Denver at Colorado Convention Center–Jan. 6—The American Dialect Society, in its 33rd annual words-of-the-year vote, selected the suffix “-ussy” as the Word of the Year for 2022. More than two hundred attendees took part in the deliberations and voting, joining both in person and virtually, in a hybrid event hosted in conjunction with the Linguistic Society of America’s annual meeting.

Presiding at the Jan. 6 voting session was Ben Zimmer, chair of the ADS New Words Committee and language columnist for the Wall Street Journal.

“The selection of the suffix -ussy highlights how creativity in new word formation has been embraced online in venues like TikTok,” Zimmer said. “The playful suffix builds off the word pussy to generate new slang terms. The process has been so productive lately on social media sites and elsewhere that it has been dubbed

-ussification.”

For more on the -ussy phenomenon, see the Vulture article by Bethy Squires, “We Asked Linguists Why People Are Adding -Ussy to Every Word”: “Riffing off ‘bussy’ (a portmanteau of ‘boy’ and ‘pussy’), now everything is a cat or a cavity. A calzone is a pizzussy. A wine bottle has a winussy.” See also Michael Dow’s scholarly paper, “A corpus study of phonological factors in novel English blends.”

Word of the Year is interpreted in its broader sense as “vocabulary item”—not just words but also phrases, compounds, and affixes. The items do not have to be brand-new, but they have to be newly prominent or notable in the past year. This is not the first time an affix has been named Word of the Year: in 1998, the prefix e- (as in email) was selected.

The vote is the longest-running such vote anywhere, the only one not tied to commercial interests, and the word-of-the-year event up to which all others lead. It is fully informed by the members’ expertise in the study of words, but it is far from a solemn occasion.

Members in the 133-year-old organization include linguists, lexicographers, etymologists, grammarians, historians, researchers, writers, editors, students, and independent scholars. In conducting the vote, they act in fun and do not pretend to be officially inducting words into the English language. Instead, they are highlighting that language change is normal, ongoing, and entertaining.

Read the full press release, including all winners, candidates, and vote tallies for all candidates.

All previous years’ winners are listed here.

January 6th, 2023 § Comments Off on Nominations for Words of the Year 2022 § permalink

Nominations for Words of the Year 2022 follow below.

The final selection will be held at 5:30 pm MST on Friday, Jan. 6 (in the Centennial Ballroom of the Denver Hyatt Regency).

American Dialect Society Words of the Year (2022)

NOMINATIONS to be voted on by the American Dialect Society, Jan. 6, 2023, Denver, CO.

EMOJI OF THE YEAR

- 🫠 [melting face]: expressing embarrassment or dread

- 🫡 [saluting face]: sign of respect or solidarity

- 🫥 [dotted line face]: feeling of invisibility

- 💀 [skull]: expressing figurative death (from laughter, frustration, etc.)

- 🚩 [red flag]: signaling danger or problems

- ⬜🟨🟩 [colored boxes]: for Wordle results

EUPHEMISM OF THE YEAR

- camping: access to abortion, as used in informal networks circumventing state anti-abortion laws

- diverse-owned: of a business, owned by members of historically underrepresented groups

- leg booty: algospeak substitution for LGBT

- pronouns: trans/nonbinary gender identities, as used in transphobic rhetoric to mock pronoun choice

- résumé embellishment: lying about one’s accomplishments

- special military operation: Russian designation for invasion of Ukraine

MOST CREATIVE WORD OF THE YEAR

- blorbo (from my shows): beloved fictional character from television or other media

- -dle: suffix for Wordle-like games (Heardle, Absurdle, Foodle, Worldle, Redactle, etc.)

- moid/foid: derogatory terms for men and women in incel culture

- short king: positive or affectionate term for a man of modest stature

- -ussy: suffix from “pussy” (as in “bussy” = “boy pussy,” now humorously attached to many words)

SNOWCLONE/PHRASAL TEMPLATE OF THE YEAR

- if I text you X, it means Y: explaining how to interpret an emoji or series of emojis

- #IStandWithX: expression of solidarity

- it’s the X for me: singling out a notable or funny aspect of something, or finding fault with someone

- not X: ironic framing device expressing an attitude of mock horror or incredulity

- she’s/he’s a 10, but X: pointing out a negative or quirky quality of someone

- X hits different: describing an experience that is affecting in a meaningful way

INFORMAL WORD OF THE YEAR

- dickriding: currying favor or sucking up to someone

- (the) ick: feeling of disgust about one’s date

- it’s giving (X): description of something exuding a particular vibe or energy (from drag culture)

- menty b: mental breakdown

- rizz: effortless attractiveness or style (short for “charisma”)

DIGITAL WORD OF THE YEAR

- BFFR: initialism for “be fucking for real”

- chief twit: self-designation of Elon Musk after acquiring Twitter

- chronically online: spending so much time online that it warps one’s sense of reality

- touch grass: go outside (antidote to spending too much time online)

- -verse: online world, as in Metaverse (Facebook’s VR) or Fediverse (federated servers on Mastodon)

POLITICAL WORD OF THE YEAR

- Dark Brandon: sinister, powerful alter ego of Joe Biden (play on “Let’s Go Brandon”)

- Dobbs: Supreme Court decision reversing abortion rights (as in “post-Dobbs”)

- pink trickle/splash: result of Republican “red wave” in midterms not materializing

- Slava Ukraini: “Glory to Ukraine!” (said in solidarity with Ukrainian resistance)

- Woman, Life, Freedom: rallying cry for women’s rights in Iran and elsewhere

MOST USEFUL/MOST LIKELY TO SUCCEED

- climate criminal: celebrity who flies excessively via private jet

- longtermism: ethical position that prioritizes improving the long-term future

- nepo baby: celebrity who is the child of a celebrity

- quiet quitting: doing no more than the minimum required for a job

WORD OF THE YEAR

- quiet quitting: doing no more than the minimum required for a job

- rizz: effortless attractiveness or style (short for “charisma”)

- Slava Ukraini: “Glory to Ukraine!” (said in solidarity with Ukrainian resistance)

- -ussy: suffix from “pussy” (as in “bussy” = “boy pussy,” now humorously attached to many words)

7 January 2023

Yesterday, the American Dialect Society voted on its Word of the Year (WOTY) for the past year. It selected the suffix —ussy, derived from pussy (as in bussy = boy pussy). The ADS uses a loose definition of word in its selection; any lexical item, as well as emojis and other signs, qualify.

The PDF of the ADS press release, listing all the categories, nominees, and vote totals, is here. There are many WOTY processes conducted by many different organizations, but the ADS selection is the original, having been conducted for thirty-three years.

The ADS consists of (mostly) professional linguists and lexicographers, but the selection of WOTY is not an academically rigorous process. Unlike other organizations that have some sort of objective criteria (e.g., Merriam-Webster bases its choice on searches in its online dictionary), the ADS process is informal. The evening before the vote, a small, self-selected group meets and comes up with nominations in the various categories. The categories are mostly consistent from year to year, but special categories can be created if there are a cluster of words on a particular topic. The next night several hundred conference attendees vote on the nominees, and nominations can be made from the floor. The process is raucous and fun, but the results can be skewed in all sorts of ways and should not be taken as serious and deliberative pronouncements.

I’ve participated in the nomination and voting in past years but sat out this year. (If I have another reason to attend the conference, or if it is online as in the past few years, I take part.) My own Wordorigins.org selections for Words of the Year are here.

What follows are my observations on the nominees and choices. Like the WOTY voting itself, my opinions are not serious linguistic conclusions. Pretty much all the WOTY contests, no matter who conducts them, are simply entertainment for the lexically inclined among us.

As for the overall WOTY choice, I’m unfamiliar with —ussy and the process of —ussification, but I don’t frequent TikTok, which evidently is where the term thrives. I would have gone with quiet quitting, which I predict will have more staying power and which is more representative of the mood of the year. Quiet quitting did win the category of Most Useful/Most Likely to Succeed. I concur with that choice, although another nominee, nepo baby, was also a strong contender in my book. —ussy also took the prize in the Most Creative category.

The ADS selection for Political WOTY was Dark Brandon, the supposed sinister, alter ego of Joe Biden, a play on the right-wing catchphrase Let’s Go Brandon. Again, I would have to disagree. Dobbs, a reference to the misogynistic US Supreme Court decision eviscerating women’s rights, received the second-most votes, and I predict it will long outlast Dark Brandon.

The choice for Digital WOTY was the suffix —dle, taken from the name of lexical games patterned after Wordle (e.g., Heardle, Absurdle, and Lewdle). That’s not a bad choice; games like this were quite the fad in 2022, and it is productive and creative. But there were several strong contenders in this category, such as chronically online, touch grass (and antidote for being chronically online), and crypto rug pull. Any of these would have been worthy choices, too. Chief twit was also nominated, and while it certainly held sway over much of the online world this past year, the less said about Elon Musk the better.

It’s giving X was the choice for Informal WOTY. It’s another one that I’m unfamiliar with. It comes out of drag culture, which I am not plugged into. But it seems like a worthy choice, especially since the other nominees in this category were lackluster.

ADS’s Euphemism of the Year is special military operation, Putin’s name for the Russian invasion of Ukraine. I can’t disagree with this one. You don’t get more euphemistic than this.

The Snowclone/Phrasal Template of the Year went to not X, an ironic expression of mock horror or incredulity. This one is fine, and again I’m not familiar with it. (I’ve probably heard it but just didn’t register it.) I would have gone with X hits different, which garnered the second highest vote total, though.

Finally, Emoji of the Year went to the skull emoji 💀, used to express figurative death (e.g., from laughter or embarrassment). That’s a solid choice.

My biggest takeaway from this year’s choices is that I’m getting too old and too divorced from trends in popular culture. Most of the nominees were completely new to me. 💀

Discuss this post

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Organization logo |

|

| Formation | March 13, 1889; 134 years ago[1][2] |

|---|---|

| Type | Not for profit |

| Purpose | «Study of the English language in North America, together with other languages or dialects of other languages influencing it or influenced by it.»[3] |

| Location |

|

|

Region served |

North America |

|

Membership |

550[1] |

|

Official language |

English |

|

President |

Luanne Vonne Schneidemesser |

|

Vice President for Communications and Technology |

Grant Barrett |

|

Executive Secretary |

Allan Metcalf |

|

Parent organization |

American Council of Learned Societies (admitted 1962)[1] |

| Website | http://www.americandialect.org/ |

The American Dialect Society (ADS), founded in 1889, is a learned society «dedicated to the study of the English language in North America, and of other languages, or dialects of other languages, influencing it or influenced by it.»[4] The Society publishes the academic journal American Speech.

Since its foundation, dialectologists in English-speaking North America have affiliated themselves with the American Dialect Society, an association which in its first constitution defined its objective as «the investigation of the spoken English of the United States and Canada» (Constitution, 1890). Over the years, its objective has remained essentially the same, only expanded to encompass «the English language in North America, together with other languages or dialects of other languages influencing it or influenced by it» (Fundamentals, 1991).[5]

History[edit]

The organization was founded as part of an effort to create a comprehensive American dialect dictionary, a near century-long undertaking that culminated in the publication of the Dictionary of American Regional English.[4] In 1889, when Joseph Wright began editing the English Dialect Dictionary, a group of American philologists founded the American Dialect Society with the ultimate purpose of producing a similar work for the United States.

Members of the Society began to collect material, much of which was published in the Society’s journal Dialect Notes, but little was done toward compiling a dictionary recording nationwide usage until Frederic G. Cassidy was appointed Chief Editor in 1963.[6] The first volume of the Dictionary of American Regional English, covering the letters A-C, was published in 1985.[4] The other major project of the Society is the Linguistic Atlas of the United States and Canada.[5]

Membership[edit]

The Society has never had more than a few hundred active members. With so few scholars advancing the enterprise, the developments in the field came slowly.[5] Members of the organization include «linguists, lexicographers, etymologists, grammarians, historians, researchers, writers, authors, editors, professors, university students, and independent scholars.»[7] Its activities include a mailing list,[8] which deals chiefly with American English but also carries some discussion of other issues of linguistic interest.[9]

Word of the Year[edit]

Since 1991, the American Dialect Society has designated one or more words or terms to be the word of the year. The New York Times stated that the American Dialect Society «probably started» the «word-of-the-year ritual».[10] However, the «Gesellschaft für deutsche Sprache» (GfdS) has announced a word of the year since 1977.

Special votes that they’ve made:

- Word of the 1990s: web[11]

- Word of the 20th Century: jazz[11]

- Word of the Past Millennium: she[11]

- Word of the Decade (2000–2009): google (as a verb)[12]

- Word of the Decade (2010–2019): they[13]

The society also selects words in other categories that vary from year to year, such as «most original», «most unnecessary», «most outrageous», or «most likely to succeed» (see: Word of the year).

A number of words chosen by the ADS are also on the lists of Merriam-Webster’s Words of the Year.[14][15]

List of Words of the Year[edit]

| Year | Word | Notes |

|---|---|---|

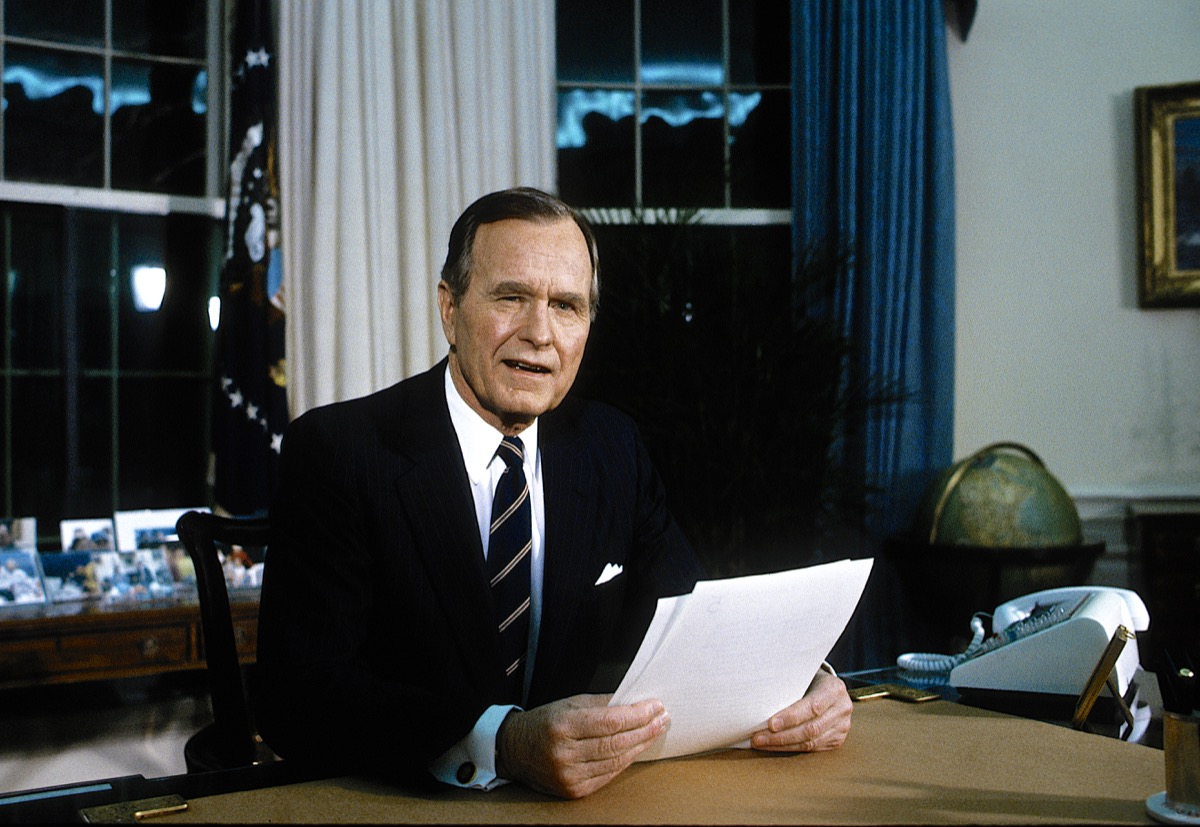

| 1990 | bushlips | (similar to «bullshit» – stemming from President George H. W. Bush’s 1988 «Read my lips: no new taxes» promise) |

| 1991 | mother of all- | (as in Saddam Hussein’s foretold «Mother of all battles») |

| 1992 | Not! | (meaning «just kidding») |

| 1993 | information superhighway | |

| 1994 | Tie: cyber and morph | (to change form) |

| 1995 | Tie: World Wide Web and newt | (as a verb: to make aggressive changes as a newcomer).[16][17] |

| 1996 | mom | (as in «soccer mom»).[18][19] |

| 1997 | millennium bug | [20][21] |

| 1998 | e- | (as in «e-mail»).[22][23] |

| 1999 | Y2K | [24][11] |

| 2000 | chad | (from the 2000 Presidential Election controversy in Florida).[25][26] |

| 2001 | 9-11, 9/11 or September 11 | [27][28] |

| 2002 | weapons of mass destruction or WMD | [29][30] |

| 2003 | metrosexual | [31][32] |

| 2004 | red/blue/purple states | (from the 2004 presidential election).[33][34] |

| 2005 | truthiness | popularized on The Colbert Report.[35][36] |

| 2006 | to be plutoed, to pluto | (demoted or devalued, as happened to the former planet Pluto).[10][37] |

| 2007 | subprime | (an adjective used to describe a risky or less than ideal loan, mortgage, or investment).[38] |

| 2008 | bailout | (a rescue by government of a failing corporation)[39] |

| 2009 | tweet | (a short message sent via the Twitter service)[40] |

| 2010 | app | [41] |

| 2011 | occupy | (in reference to the Occupy movement)[42] |

| 2012 | #hashtag | [43] |

| 2013 | because | (introducing a noun, adjective, or other part of speech: «because reasons,» «because awesome») [44] |

| 2014 | #blacklivesmatter | [45] |

| 2015 | they | («gender-neutral singular pronoun for a known person, particularly as a nonbinary identifier»)[46] |

| 2016 | dumpster fire | an exceedingly disastrous or chaotic situation[47] |

| 2017 | fake news | defined by the ADS in two ways: «disinformation or falsehoods presented as real news» and «actual news that is claimed to be untrue»[48] |

| 2018 | tender-age shelter | («government-run detention centers that have housed the children of asylum seekers at the U.S./Mexico border») [49] |

| 2019 | (my) pronouns | «Recognized for its use as an introduction for sharing one’s set of personal pronouns (as in ‘pronouns: she/her’).»[13] |

| 2020 | Covid | [50] |

| 2021 | Insurrection | referring to the January 6 United States Capitol attack.[51] |

| 2022 | -ussy | (suffix from pussy)[52] |

See also[edit]

- American English

- Language planning

- Language Report from Oxford University Press

- Lists of Merriam-Webster’s Words of the Year

- Neologism

- Word formation

References[edit]

- ^ a b c American Council of Learned Societies (ACLS) (2012). «American Dialect Society». ACLS.org. www.acls.org. Retrieved February 7, 2012.

- ^ «The American Dialect Society». The Harvard Crimson. Retrieved January 9, 2023.

- ^ «Constitution and Officers». Americandialect.org. American Dialect Society. 2012. Retrieved February 4, 2012.

- ^ a b c Flexner, Stuart B. (December 15, 1985). «One language, highly divisible». The New York Times. Retrieved February 19, 2008.

- ^ a b c Auroux, Sylvain (2000). History of the Language Sciences. Walter de Gruyter, 2006. p. 2366. ISBN 3-11-016736-0.

- ^ Hall, Joan Houston (2004). «The Dictionary of American Regional English». In Finegan, Edward; Rickford, John (eds.). Language in the USA: Perspectives for the 21st Century. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 94–95.

- ^ ««Subprime» voted 2007 word of the year». Americandialect.org. American Dialect Society. January 4, 2008. Retrieved February 19, 2008.

- ^ «ADS-L: email discussion list». Americandialect.org. American Dialect Society. 2012. Archived from the original on June 29, 2006. Retrieved February 2, 2012.

- ^ Horn, Laurence (January 29, 2003). «Re: Canadians in ADS». ADS-L. listserv.linguistlist.org. Archived from the original on July 19, 2012. Retrieved February 2, 2012.

- ^ a b Newman, Andrew Adam (December 10, 2007). «How Dictionaries Define Publicity: the Word of the Year». The New York Times. Retrieved February 19, 2008.

- ^ a b c d «1999 Words of the Year, Word of the 1990s, Word of the 20th Century, Word of the Millennium». American Dialect Society. January 13, 2000.

- ^ 2009 Word of the Year is “tweet”; Word of the Decade is “google” – American Dialect Society. Published 8 January 2010. Retrieved 31 Mar 2019.

- ^ a b 2019 Word of the Year is “(My) Pronouns,” Word of the Decade is Singular “They” – American Dialect Society. Published 3 January 2020. Retrieved 28 Mar 2019.

- ^ Lea, Richard (November 30, 2009). «‘Twitter’ declared top word of 2009″. The Guardian. Guardian News and Media Limited. Retrieved February 2, 2012.

- ^ Merriam-Webster staff (2009). «Word of the Year 2009». Merriam-Webster Online. Merriam-Webster. Retrieved February 2, 2012.

- ^ Ritter, Jim (December 31, 1995). «1995’s Word Of the Year: Either ‘Web’ – Or ‘Newt’«. Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved February 21, 2008.

- ^ «1995 Words of the Year». Americandialect.org. American Dialect Society. January 13, 1996. Archived from the original on June 15, 2006. Retrieved February 21, 2008.

- ^ Associated Press (January 5, 1997). «Linguists pick ‘soccer mom’ as 1996’s word». The Philadelphia Inquirer. Retrieved February 21, 2008.

- ^ «1996 Words of the Year». Americandialect.org. American Dialect Society. January 13, 1997. Archived from the original on June 15, 2006. Retrieved February 21, 2008.

- ^ Smith, Sheron (January 10, 1998). «Word! ‘Millennium Bug’ is picked as top phrase of 1997». The Macon Telegraph. Retrieved February 21, 2008.

- ^ «1997 Words of the Year». Americandialect.org. American Dialect Society. January 13, 1998. Archived from the original on June 15, 2006. Retrieved February 21, 2008.

- ^ Gallentine, Shana (January 21, 1999). «1998: Our society defined in just a few short words». The Red and Black. Archived from the original on December 3, 2008. Retrieved February 21, 2008.

- ^ «1998 Words of the Year». Americandialect.org. American Dialect Society. January 13, 1999. Retrieved February 21, 2008.

- ^ Freeman, Jan (June 18, 2000). «Steal this coinage». The Boston Globe. Retrieved February 21, 2008.

- ^ Kershner, Vlae (December 11, 2002). «Help us choose the ‘Word of the Year’«. San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved February 19, 2008.

- ^ «2000 Words of the Year». Americandialect.org. American Dialect Society. January 13, 2001. Retrieved February 19, 2008.

- ^ Scott, Janny (February 24, 2002). «A nation challenged: Language; Words of 9/11 Go From Coffee Shops To the Dictionaries». The New York Times. Retrieved February 19, 2008.

- ^ «2001 Words of the Year». Americandialect.org. American Dialect Society. January 13, 2002. Retrieved February 19, 2008.

- ^ Associated Press (January 6, 2003). «‘W.M.D.’ voted word of year». USA Today. Retrieved February 19, 2008.

- ^ «2002 Words of the Year». Americandialect.org. American Dialect Society. January 13, 2003. Retrieved February 19, 2008.

- ^ Newman, Andrew Adam (October 10, 2005). «In Time of Studied Ambiguity, a Label for the Manly Man». The New York Times. Retrieved February 19, 2008.

- ^ «2003 Words of the Year». Americandialect.org. American dialect Society. January 13, 2004. Retrieved February 19, 2008.

- ^ Associated Press (January 10, 2005). «Linguists’ phrase of the year: ‘Red state, blue state, purple state’«. The Seattle Times. Retrieved February 19, 2008.

- ^ «2004 Word of the Year» (PDF). Americandialect.org. American Dialect Society. January 7, 2005. Retrieved February 19, 2008.

- ^ Nash, Margo (April 9, 2006). «Jersey Footlights». The New York Times. Retrieved February 19, 2008.

- ^ «Truthiness Voted 2005 Word of the Year». Americandialect.org. American Dialect Society. January 6, 2006. Retrieved February 8, 2008.

- ^ «‘Plutoed’ Voted 2006 Word of the Year». Americandialect.org. American Dialect Society. January 5, 2007. Retrieved February 19, 2008.

- ^ ««Subprime» voted 2007 word of the year». American Dialect Society. January 4, 2008. Retrieved March 30, 2019.

- ^ «‘Bailout’ voted Word of the Year». Americandialect.org. American Dialect Society. 2009.

- ^ Barrett, Grant (January 8, 2009). «Word of the Year» (PDF). Americandialect.org. Retrieved January 9, 2010.

- ^ «‘App’ voted Word of the Year». Americandialect.org. American Dialect Society. 2011. Archived from the original on March 29, 2011.

- ^ «Word of the Year» (PDF). Americandialect.org. American Dialect Society. 2012.

- ^ “Hashtag” is the 2012 Word of the Year – American Dialect Society. Published 4 January 2013. Retrieved 12 May 2013.

- ^ «Because» is the 2013 Word of the Year – American Dialect Society. Published 3 January 2014. Retrieved 6 Jan 2014.

- ^ 2014 Word of the Year is “#blacklivesmatter” – American Dialect Society. Published 9 January 2015.

- ^ 2015 Word of the Year is singular “they” — American Dialect Society. Published 8 January 2016.

- ^ “Dumpster fire” is 2016 American Dialect Society word of the year — American Dialect Society. Published on 6 January 2017. Retrieved on 26 January 2017.

- ^ “Fake news” is 2017 American Dialect Society word of the year — American Dialect Society. Published on 5 January 2018. Retrieved on 5 January 2018.

- ^ “Tender-age shelter” is 2018 American Dialect Society word of the year – American Dialect Society. Published 4 January 2019. Retrieved 28 Mar 2019.

- ^ «2020 Word of the Year is «Covid»«. American Dialect Society. December 18, 2020. Retrieved September 16, 2021.

- ^ «American Dialect Society». Americandialect.org. January 7, 2022. Retrieved January 10, 2022.

- ^ «2022 Word of the Year is «-ussy»«. American Dialect Society. December 18, 2020. Retrieved January 7, 2023.

Further reading[edit]

- Lerer, Seth (2007). Inventing English: A Portable History of the Language. New York, New York: Columbia University Press. p. 195.

- Mencken, H.L. (2006). The American Language: An Inquiry into the Development of English in the United States. Alfred A. Knopf.

- Metcalf, Allan A. (2002). Predicting New Words: The Secrets of Their Success. Boston, Massachusetts: Houghton Mifflin Company. p. 188.

- Sheidlower, Jesse (January 11, 2005). «Linguists Gone Wild! Why «wardrobe malfunction» wasn’t the word of the year». Slate Magazine. The Slate Group, LLC.

- Wolfram, Walt; Natalie Schilling-Estes (2006). American English: Dialects and Variation. Malden, Massachusetts: Blackwell Publishing. p. 24.

External links[edit]

- Official website

- American English dialects at Curlie

- American Dialect Society, information page at Duke University Press

- Publication of the American Dialect Society, archive articles at Duke University Press

- American Dialect Society, information page at American Council of Learned Societies (ACLS)

- American Dialect Society, news page at Dictionary Society of North America

- American Dialect Society Collection, at Library of Congress

- American Dialect Society, publications listed with timeline at WorldCat, from participation in the Online Computer Library Center

- Creator: American Dialect Society, at website of Internet Archive

Words are fun, finicky, and ever-evolving. As time goes by, new words make their way into common usage and old words take on new meanings. Each year, there’s one term that stands out the most. That’s why the American Dialect Society (ADS), an organization that’s «dedicated to the study of the English language in North America, and of other languages, or dialects of other languages, influencing it or influenced by it,» annually chooses a word or phrase to highlight. It may be important for political or pop culture reasons; it could be one that’s way out of use today or one that’s getting increasingly popular. From its inaugural winner in 1990, here is every ADS Word of the Year through today. And for more to appreciate, here are The 50 Most Beautiful Words in the English Language—And How to Use Them.

In 1988, George H.W. Bush delivered a speech at the Republican National Convention in which he told the crowd, «Read my lips: no new taxes.» That promise was broken, and «bushlips» (as in bush lips) made its way into popular language as a way to describe «insincere political rhetoric,» according to the ADS. They chose it as their word of the year in 1990.

And fascinating regional dialects, here are 60 Words People Pronounce Differently Across America.

The word of the year in 1991 was actually a collection of words that made up what you might consider a momentum-building prefix. Add «mother of all» to whatever you’re referring to and it immediately makes it the greatest, biggest, or most impressive example of something. To bring the phrase into today’s world, the mother of all Instagrammable cafés is the most social media-worthy eatery around.

The only time you’re likely to hear someone use the expression «not!» nowadays is if they’re dressing up as a Wayne’s World character for Halloween. However, in 1992, it was the word of the year (with the exclamation mark included for needed emphasis, of course).

And for more indelible expressions from the decade, here are 30 Movie Quotes Every ’90s Kid Knows by Heart.

In 1993, «information superhighway» was the term to use when referring to modern communication methods. And while these days you might be talking about texts or FaceTiming, in 1993, data was shared primarily via computers, televisions, and telephones.

In 1994, «cyber» («pertaining to computers and electronic communication») was named the word of the year—but it wasn’t alone. The ADS called a tie, also choosing «morph» («to change form») as one of the top words of those particular 12 months.

And for some out-of-date words that used to be all the rage, here are 150 Slang Terms From the 20th Century No One Uses Anymore.

The tie of 1994 was the first time the ADS chose two terms as the co-words of the year, but it wasn’t the last. It may be hard to imagine life without the internet today, but in 1995, surfing the «world wide web» was still new and thrilling. That’s why it was the word of the year, as was «newt,» which refers to the act of «mak[ing] aggressive changes as a newcomer.»

In 1996, soccer moms weren’t just women who were taking their kids to sports practices—they were an entire demographic that was identified as a «newly significant type of voter,» according to the ADS. That’s why «mom,» taken from soccer mom, was chosen as the word of the year.

And for terms you’ve been pretending to understand, here are 50 Words You Hear Every Day But Don’t Know What They Mean.

«Millennium bug» was widely used to refer to a tech-related glitch that supposedly threatened to shut down computers (and everything run by computers) if the devices weren’t able to handle the rare change in date when January 1, 2000 rolled around. Of course, it turned out to be unwarranted anxiety. But the fear—and the phrase—were very real.

The word of the year in 1998 wasn’t a word at all. It was part of a word. Or, to be more exact, it was a prefix. Short for electronic, «e-» became the ADS’s word of the year since it was being widely used in terms like «e-mail» and «e-commerce.»

And for more language facts delivered right to your inbox, sign up for our daily newsletter.

As the world prepared for the new millennium, the term «Y2K» (which stands for the year 2000) became all the rage. Fittingly the ADS’s word of the year for 1999, the term was widely used to refer to the Y2K bug or Y2K scare, which was another name for the millennium bug.

If you think of the term «chad» solely as a man’s name today, you’re not alone. But in the year 2000, the presidential election controversy led to the ADS choosing it for the meaning «a small scrap of paper punched from a voting card.»

In 2001, the United States suffered one of the deadliest attacks within its borders on Sept. 11, a date that was chosen as the word of the year. The infamous day that is now a part of the darker side of the country’s history also became known as 9-11 and 9/11.

It’s certainly a sad situation when «weapons of mass destruction» (or WMD) is chosen as the word of the year. But that was what happened in 2002 when the United States attempted to track down possible chemical and biological weapons as well as nuclear bombs in Iraq.

At the turn of the century, the world was finally ready to recognize and embrace the «metrosexual,» a man who cared about his appearance and was savvy about style. In 2003, it became the ADS’s word of the year.

Nearly 15 years later, The Telegraph claimed that the «metrosexual is dead—and a new kind of sensitive man killed him,» one who appreciates a «greater depth and meaning» and «place[s] the highest value on dependability, reliability, honesty, and loyalty.» We can all get behind that, right?

Political divisions in America are represented by two varying colors, which is why «red/blue/purple states» was the popular term in 2004 to identify which areas leaned a certain way. The American Dialect Society explains that «red favor[s] conservative Republicans and blue favor[s] liberal Democrats,» while those who are undecided are considered purple. Americans are much more used to hearing these terms today.

There’s the truth and then there’s «truthiness,» which is a term that «refers to the quality of seeming to be true but not necessarily or actually true according to known facts,» according to Merriam-Webster. The American Dialect Society chose «truthiness» as their word of the year in 2005 after it was popularized by Stephen Colbert and his right-wing parody show The Colbert Report, which launched that year.

Pluto has gone through a wild ride over the years in terms of classification. Once considered a planet, it was demoted when it no longer met the necessary criteria (something that is still being debated). And in 2006, the term «plutoed» was the word to use if you wanted to make a comparison between the spacial body and something else that had lost status or wasn’t being valued. Poor Pluto.

The word «subprime» is pretty self-explanatory—it’s something that’s, well, not exactly the best. When it comes to investments, specifically real estate, subprime is what you’d call a loan or deal that’s iffy or risky. And in 2007, buyers, sellers, and property flippers were all dealing with the Subprime Mortgage Crisis that hit the United States, which is why it became the word of the year.

When the government helps out a failing business, it’s called a bailout. And as you may recall in 2008, U.S. Congress approved a $700 billion Wall Street bailout that dominated headlines, hence ADS choosing it.

Twitter launched in 2006, and by January 2009, users were sending two million messages a day over the social media platform. That’s why the top word that year from the ADS was «tweet,» which can refer to either the action of sending text on the platform or the actual message itself.

An app is certainly not an unusual thing these days, but in 2010, it was a word that was newly buzzing. At the time, Ben Zimmer, chair of the New Words Committee of the American Dialect Society, noted, «With millions of dollars of marketing muscle behind the slogan ‘There’s an app for that,’ plus the arrival of ‘app stores’ for a wide spectrum of operating systems for phones and computers, app really exploded.» Hence it being crowned the word of the year at the close of one decade and the start of a new one.

Politics was at the forefront of the conversation in 2011 when «occupy» was selected as the word of the year. At the time, the Occupy Wall Street protest movement was ongoing, putting a spotlight on financial institutions and the economic inequality between the wildly wealthy one percent of the population and the other 99.

«Hashtag»—which is represented with the «#» and which Merriam-Webster calls a «symbol before a word or phrase [that’s] meant to be used on social media as a way to track certain terms»—was the word of the year in 2012. Zimmer explained the choice, saying, «In the Twittersphere and elsewhere, hashtags have created instant social trends, spreading bite-sized viral messages on topics ranging from politics to pop culture.»

«Because» is a term that was chosen as the word of the year due to the fact that people were using it in a slightly modified way in 2013. Instead of having to say «because of [insert reasoning here],» we could now drop the «of.» Confused? Here’s an example: Instead of saying «I an ate apple because I’m hungry,» you can say, «I ate an apple because hunger.» Or, instead of saying, «I need an umbrella because it’s raining,» you can say, «I need an umbrella because rain.» And if you don’t want to explain yourself at all, you can simply tell someone that you’ve done something «because reasons.»

In 2012, «hashtag» may have been recognized for its significance, but two years later, an actual hashtag was selected as the word of the year. Due to heightened awareness of the treatment of Black people by police and authority figures, #blacklivesmatter «became a rallying cry and vehicle for expressing protest» and was selected as the most significant word of the year in 2014.

«They» is certainly not a new word and isn’t one that only recently became commonly used. However, the way it’s used has changed in recent years. Once meant to refer to a group of individuals, it’s now also a way to identify a single person who is gender non-conforming or nonbinary and chooses not to use gender-specific pronouns.

Judging by the ADS’s word of the year, 2016 was a rough 12 months. «Dumpster fire»—which refers to «an exceedingly disastrous or chaotic situation»—was the term the ADS chose as the one that «best represent[ed] the public discourse and preoccupations of the past year.» And while it may have been the (dire) word of choice a few years ago, it’s still regularly used today.

In the age of the 24-hour news cycle and far-reaching social media platforms, it can be difficult to sort through what information is accurate and what is not. The past few years have seen real facts attacked and dismissed by some in an effort to deny, confuse, or misdirect others. So it’s no surprise the term «fake news» was deemed the word of the year in 2017.

The word of the year for 2018 was one that stems from a sad reality that has manifested within the United States. According to the ADS, the term «tender-age shelter/facility/camp» first emerged in June 2018 when it was reported that infants and young children were being held in special detention centers after being separated from their families who crossed over the southern border.»

Returning to the cultural shift that prompted 2015’s Word of the Year, the ADS chose «(my) pronouns» as the term that defined 2019. As awareness of differing gender identities has grown, it’s become more common for individuals of all genders to list their pronouns in e-signatures and bios, as well as to offer them verbally.

«When a basic part of speech like the pronoun becomes a vital indicator of social trends, linguists pay attention,» Zimmer explained in the ADS announcement. «The selection of ‘(my) pronouns’ as Word of the Year speaks to how the personal expression of gender identity has become an increasing part of our shared discourse.» In addition, the singular form of «they» was chosen as the Word of the Decade.