Открыть всю книгу

Think Back! Put these words into the table. In groups, add other words to each category. – Вспомните! Поместите эти слова в таблицу. В группах, добавьте другие слова для каждой категории.

Rooms/ places in the house — комнаты / мест в доме: hall — прихожая, study — кабинет, attic — чердак, kitchen — кухня, toilet — туалет, bathroom — ванная, living room — гостиная, dining room — столовая, basement — подвал

Furniture — мебель: armchair — кресло, cupboard — шкаф, wardrobe — гардероб, sofa — диван, bookshelf – книжная полка, chest of drawers — комод

Appliances – бытовая техника: DVD player — DVD-плеер, kettle — чайник, TV — телевизор, freezer — морозилка, vacuum cleaner — пылесос, video — видео, washing machine – стиральная машинка, microwave — микроволновка, heater — обогреватель, stairs — лестница

Things outside the house – вещи вне дома: drive – подъезд к дому, garage — гараж, statue — статуя, fountain — фонтан, garden — сад, balcony — балкон, porch — крыльцо, letter box – почтовый ящик, lawn — газон, doorbell – дверной звонок

Открыть всю книгу

1)General

features of word-compounding.

2)Structural

and semantic peculiarities of English compounds.

3)Classification

of compounds.

4)The

meaning of compounds.

5)Motivation

of English compounds.

6)Special

groups of compounds.

Word-compounding

is

a way of forming new words combining two or more stems. It’s

important to distinguish between compound words and

word-combinations, because sometimes they look or sound alike. It

happens because compounds originate directly from word-combinations.

The

major feature of compounds is their inseparability

of various kinds: graphic, semantic, phonetic, morphological.

There

is also a syntactic

criterion which helps us to distinguish between words and word

combinations. For example, between the constituent parts of the

word-group other words can be inserted (a

tall handsome

boy).

In

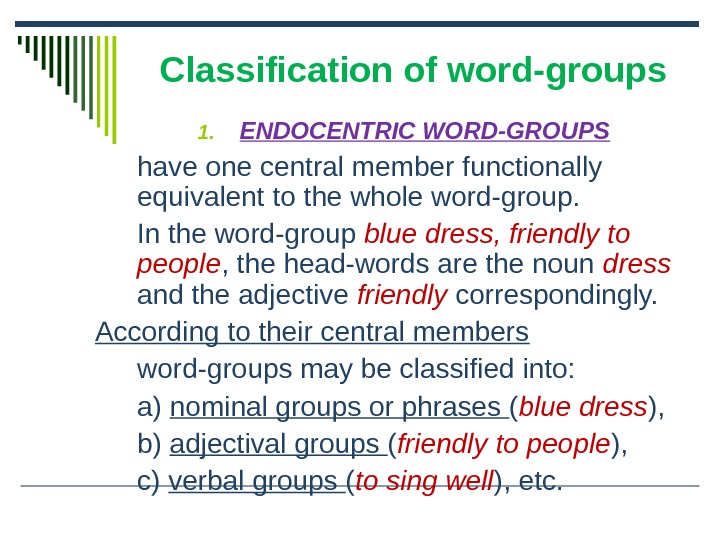

most cases the structural and semantic centre of the compound word

lies on the second component. It shows what part of speech the word

is. The function of the first element is to modify, to determine the

second element. Such compounds (with the structural and semantic

centre “in” the word) are called endocentric.

There

are also exocentric

compounds where the centre lies outside (pickpocket).

Another

type of compound words is called bahuvrihi

– compound nouns or adjectives consisting of two parts: the first

being an adjective, the second – a noun.

There

are several ways to classify compounds. Firstly, they can be grouped

according to their part of speech. Secondly, compounds are grouped

according to the

way the stems are linked together:

morphological compounds (few in number); syntactic compounds (from

segments of speech, preserving articles, prepositions, adverbs).

The

third classification is according to the combinability of compounding

with

other

ways of word-formation:

1) compounds proper (formed by a mere juxtaposition of two stems);

2)

derived or derivational compounds (have affixes in their structure);

3)

converted compounds;

4)

contractive compounds (based on shortening);

5)

compounds based on back formation;

Beside

lexical meanings the components of a compound word have

distributional

and

differential

meanings.

By distributional

meaning

we understand the order, the arrangement of the stems in the word.

The differential

meaning

helps to distinguish two compounds possessing the same element.

The

structural

meaning

of a compound may be described through the interrelation of its

components. e.g. N + Adj (heart-sick

– the relation of cpmparison).

In

most cases compounds are

motivated.

They can be completely motivated, partially motivated, unmotivated.

In partially motivated compounds one of the components (or both) has

changed its original meaning. The meaning of unmotivated compounds

has nothing to do with the meanings of their individual parts.

As

for special groups of compounds, here we distinguish:

a)

reduplicative compounds;

b)

ablaut combinations;

c)

rhyme combinations.

There’s

a certain group of words that stand between compounds and derived.

These are words with so called semi-affixes:

kiss proof

(about

lipstick), fireproof,

foolproof.

Conversion

1)General

problems of conversion in English.

2)Semantic

relations between conversion pairs.

3)

Sources and productivity of conversion.

In

linguistics conversion

is

a type of word-formation; it is a process of creating a new word in a

different part of speech without adding any derivational element. The

morphemic shape of the original word remains unchanged. There are

changes in the syntactical function of the original word, its part of

speech and meaning.

The

question of conversion

has been a controversial one in several aspects. The term conversion

was first used by Henry Sweet at the end of the 19th

century. The nature of conversion has been analyzed by several

linguists. A number of terms have been offered to describe the

process in question.

The

most objective treatment of conversion belongs to Victoria Nikolaevna

Yartseva. According to her, it is a combined morphological,

syntactical and semantic way of word-formation.

The

process was called “non-affixal

derivation”

(Galperin) or “zero

derivation”.

These terms have drawbacks, because there can be other examples of

non-affixal or zero derivation which are not connected with the

process described at the beginning of the lecture.

The

term “functional

change”

(by Arthur Kennedy) also has short-comings. The term implies that the

first word merely changes its function and no new word appears. It

isn’t possible.

The

word conversion

we

use talking about this way of word-formation is not perfect as well.

It means the transformation of something into another thing, the

disappearance of the first word. But the old and the new words exist

together.

The

largest group

related through conversion consists of verbs

converted from nouns.

The relations of the conversion pair in this case can be of the

following kind:

1)

instrumental relations;

2)

relations reflecting some characteristic of the object;

3)

locative relations;

4)

relations of the reverse process, the deprivation of the object.

The

second major division of converted words is deverbial

nouns

(nouns converted from verbs).

They

denote:

1)

an instance of some process;

2)

the object or the result of some action;

3)

the place where the action occurs;

4)

the agent or the instrument of the action.

Conversion

is not only a highly productive but also a particularly English way

of word-building. There are a lot of words in the English language

that are short and morphologically unmarked (don’t indicate any

part of speech). By short words we mean monosyllables, such words are

naturally more mobile and flexible than polysyllables.

In

English verbs and nouns are specially affected by conversion.

Conversion has restrictions. It’s impossible to use conversion if

verbs cannot represent some process as a succession of isolated

actions. Besides, the structure of the first word shouldn’t be

complicated.

Conversion

is typical not only of nouns, verbs and adjectives, but other parts

of speech as well, even such minor elements as interjections and

prepositions or shortened words.

Shortening

1.

General problems of shortening.

2.

Peculiarities of shortenings.

Shortening

stands apart from other ways of word-formation because it doesn’t

produce new words. It produces variants of the same word. The

differences between the new and the original word are in style,

sometimes in their meaning.

There

are two major groups of shortenings (colloquial and written

abbreviations). Among shortenings there can be polysemantic units as

well.

Shortenings

are classified a) according to the position of the shortened part of

the word (clipped words), b) into shortened word combinations, c)

into abbreviations, d) into blendings.

Among

clipped words there are cases of apocope, aphaeresis, and syncope.

Abbreviations can be read as in the alphabet, as one word.

The

Semantic Structure of English Words

1.General

problems of semasiology. The referential and the functional

approaches to the meaning of English words.

2.Types

of meaning.

3.Change

of meaning.

4.Polysemy.

5.Homonymy.

6.Synonyms,

antonyms and other semantic groupings.

The

branch of linguistic which specializes in the study of meaning is

called semantics or semasiology. The modern approach to semantics is

based on the fact that any word has its inner form which is called

the semantic structure.

There

are two main approaches to the meaning of a word: referential and

functional.

The

referential approach is based on the notion of the referent (the

object the word is devoted to). It also operates the notions of the

concept and word. The word and the referent are related only through

the concept. The drawback of the approach is in the fact that it

deals with psychology mostly.

According

to the functional approach the meaning of a word depends on the

function of the word in a sentence. The approach is not perfect

because it can help us only to compare the meanings of words.

Speaking about the meaning of a word both approaches should be

combined.

The

meaning of a word can be divided into grammatical

and

lexical.

The latter is divided into denotational

and

connotational

meanings. The denotational meaning gives the general idea which is

characteristic of a certain word. The connotational meaning combines

the emotive colour and the stylistic value of a word.

The

smallest elements of meaning are called semes.

There

are words with either only the denotational or the connotational

meaning.

Causes

of semantic changes can be extra

linguistic and

linguistic.

Extra linguistic causes are historical in their nature. Among

linguistic causes we distinguish discrimination of synonyms,

ellipsis, linguistic analogy.

As

for the nature of semantic changes, it is connected with some sort of

association between the old and the new meanings. These associations

can be of two types: of similarity (linguistic metaphor), of

contiguity (linguistic metonymy).

The

result of semantic changes can be seen in denotational and

connotational meanings. The denotational meaning can be generalized

or specialized. The connotational meaning can be worsened or

elevated.

Most

words are polysemantic. Monosemantic words are usually found among

terms and scientific words. The ability of words to have more than

one meaning is called polysemy.

Polysemy exists only in the language system.

The

semantic structure of a polysemantic word may be described as a

combination of its semantic variants. Each variant can be described

from the point of view of their denotational and connotational

meaning.

Polysemy

is closely connected with the notion of the context

(the minimum stretch of speech which is sufficient to understand the

meaning of a word). The main types of context are lexical and

grammatical.

Homonyms

are words identical in sound and spelling or at least in one of these

aspects, but different in their meaning. According to Profesor

Smirnitsky homonyms can be divided into two groups: full homonyms

(represent the same part of speech and have the same paradigm),

partial homonyms (don’t coincide either in their spelling or

paradigm).

Another

classification of homonyms deals with homophones

and homographs.

The

sources of homonyms are phonetic changes, borrowing, word-building

(especially conversion), shortening.

There

are several classifications of various word groups. The semantic

similarity and polarity are connected with synonyms and antonyms.

Synonyms

are words different in sound-form but similar in meaning. According

to Vinogradov synonyms can be divided ideographic, stylistic and

absolute. A dominant

synonym

(in any row of synonyms) is more frequent in communication and

contains the major denotational component of the synonyms in

question.

Antonyms

are words belonging to the same part of speech with some opposite

meaning.

As

for other groups of words, there are hyponyms, hyperonyms, semantic

fields, thematic groups.

The

development of the English vocabulary

1.The

development of the vocabulary. Structural and semantic peculiarities

of new vocabulary

units.

2.Ways

of enriching the vocabulary.

If

the language is not dead, it’s developing all the time. The items

that disappear are called archaisms.

They can be found among numerous lexical units and grammatical forms.

New

words or expressions, new meanings of older words are called

neologisms.

The introduction of new words reflects developments and innovations

in the world at large and in society.

Apart

from political terms, neologisms come from the financial world,

computing, pop scene, drug dealing, crime life, youth culture,

education.

Neologisms

come into the language through

1)productive

ways of word formation;

2)ways

without any pattern;

3)semantic

changes of old words;

4)borrowing

from other languages.

There

are numerous cases of blending, compounding, conversion. Borrowed

words mostly come from French, Japanese, the American variant of the

English language.

Соседние файлы в предмете [НЕСОРТИРОВАННОЕ]

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- Размер: 211 Кб

- Количество слайдов: 39