The word Christmas comes from Middle English Cristemasse, which in turn comes from Old English Cristes-messe, literally meaning Christ’s Mass.

Of course, we are not talking about the physical mass of Christ’s body. The origin of mass, in the Christian sense of the word, is not entirely clear. We know it comes from Latin missa, but there are several competing theories as to what missa is supposed to mean. Some scholars say it is a form of the Latin verb mittere, in which case it would mean “something that has been sent” (but it cannot refer to Christ himself because “missa” is grammatically feminine).

Others say that it is a late form of Latin missio, meaning “dismissal”. This is supported by the fact that Catholic masses are traditionally concluded with the words:

Ite, missa est.

which would mean, “Go, the dismissal is made”, provided this interpretation is correct.

Yet another explanation is that it is, in fact, the Hebrew word missah, “unleavened bread”, which God commanded to be offered with the Passover sacrifice in the Exodus.

The name “Christ”

The origin of the designation Christ is also not without interest. It comes from Greek Χριστός (Christós), meaning “anointed”, which is a translation of Hebrew מָשִׁיחַ māšîaḥ (“anointed”) that has been incorporated into the English language as “messiah”. Hence, “Christ” and “Messiah” mean essentially the same, the former originating in Ancient Greek and the latter in Classical Hebrew.

Xmas

Finally, we get to the word Xmas (usually pronounced the same as Christmas, but some pronounce it, rather incorrectly, as /ˈɛksməs/). Many people believe that writing “Xmas” instead of Christmas is an attempt to remove Christ from Christmas and may even consider it blasphemous.

However, “X” in “Xmas” is, in fact, not the English letter “ex”. It is an abbreviation of the Greek name of “Christ”, Χριστός (Christos), which starts with the Greek letter Chi. Abbreviating “Christ” as “X” can be traced many centuries back, with some written documents dated as early as 1100 AD.

Subscribe to my educational newsletter

to receive a weekly summary of new articles

Enter your email address below:

Please, enter a valid email address:

You tried to submit the form very quickly after opening this page. To confirm that you are a human, please, click on the button below again:

Use the image

You can use the image on another website, provided that you link to the source article. If you share it on Twitter or Facebook, I kindly ask you to tag my profile @JakubMarian.

If you share it on reddit, please, share a link to the whole article and give credit to my subreddit r/JakubMarian in the comments.

WHEN Christmas is just around, we’re all getting into the festive spirit, wrapping presents, putting up decorations, and embracing the party season.

But ever wondered what the word «Christmas» actually means, or where it came from?

1

Where does the term Christmas come from and what does it mean?

Most of us would assume it originates from the word Christ, as the whole idea of Christmas is to celebrate the birth of Jesus.

To a point that is the case — the word is a shortened form of «Christ’s mass», or «Cristes Maesse» as it was first recorded in 1038.

This was followed by the term Cristes-messe in 1131, according to The Catholic Encyclopedia.

The term «Christ» — or Crīst as it originally read — comes from the Greek word Khrīstos, a translation of the Hebrew word Messiah, which means «anointed».

The second part of Christmas — messe — is a version of the Latin word missa, the celebration of the Eucharist tradition of eating bread and drinking wine in memory of Jesus.

This is also called Holy Communion and the Lord’s Supper.

When did we start celebrating Christmas?

Interestingly, early Christians actively rejected the celebration of Christ’s birth as they saw birthdays as a pagan ritual, followed in the bible by figures like the Pharaoh.

Easter and Pentecost (celebrated seven weeks after Easter to mark the descent of the Holy Spirit upon the Apostles and other followers of Jesus Christ) were the main occasions in the Christian calendar for ecclesiastical feasts until midway through the fourth century, when Christmas and Epiphany were added to the calendar.

December 25 was then established as the Nativity Feast Day (not necessarily the day Jesus was born — but that’s another story) and the official ‘Nativity Mass’ was the first Mass of the day, held at 9 am.

As time passed, the celebration of Christmas became more popular — and so too did the liturgical practices that went with it.

Christmas Mass became a central fixture in the church calendar, which led to the day becoming known as Christ’s Mass by the 11th century.

Why is Christmas shortened to Xmas?

It turns out we’ve got the Greeks to thank for that.

As we mentioned earlier, the word Khrīstos (the origin of the word Christ) appears as «Χριστός» when written in Greek.

The abbreviation Xmas is based on the first letter — chi, which appears as X — followed by «mas»; a shortened version of Mass.

There is an alternative theory that the use of Xmas stems from an attempt by some to remove the religious tradition from Christmas by removing the word Christ, but its use dates all the way back to the 16th century.

“Christmas” is an Old English word, constructed from the combination of two words, namely “Christ” and “Mass”. The first recorded Old English version of the phrase, “Crīstesmæsse,” dates back to 1038, but by the Middle Ages the term had already morphed into “Cristemasse;” a slightly more modern version of the phrase.

The origins

The two separate parts of the word can be traced back to Greek, Hebrew and Latin origins. “Christ” comes from the Greek word “Khrīstos” (Χριστός) or “Crīst,” and there’s a lot of evidence to suggest that the Hebrew word “Māšîaḥ” (מָשִׁיחַ) or “Messiah,” which actually means “anointed,” has also played a considerable role in the construction of the first part of the word “Christmas.” The second part most probably comes from the Latin word, “Missa,” which refers directly to the celebration of the Eucharist.

It is also believed that “Christenmas” is an archaic version of the word “Christmas,” whose origins can be attributed to the Middle English phrase, “Cristenmasse,” which when literally translated becomes, “Christian Mass.”

Christmas… the international holiday

Even though “Christian Mass” or “Christ’s Mass” refers to the annual Christian commemoration of the birth Jesus Christ, “Christmas” is an international holiday which, throughout the ages, has been celebrated by non-Christian communities and been referred to via a variety of different names, including the following:

- Nātiuiteð (nātīvitās in Latin) or “Nativity” means “birth” and has often been used as an alternative to the word “Christmas”

- The Old English word, Gēola, or “Yule” corresponds to the period of time between December and January and eventually became associated with the Christian festival of “Christmas”

- “Noel” is an English word which became popular during late 14th century and which is derived from the Old French term “Noël” or “Naël,” literally translating to “the day of birth”

“Xmas”… modern or ancient?

It’s also worth noting that, even though most people tend to view the abbreviation “Xmas” as a modern bastardisation of the word “Christmas,” “Xmas” is an ancient term and not a grammatically-incorrect modern construction. “X” was regularly used to represent the Greek symbol “chi,” (the first letter of the word “Christ”) and was very popular during Roman Times.

После текста вы найдете Рецепт рождественской индейки

(текст на английском языке)

To begin with, Christmas is a religious holiday. The word Christmas means Christ’s Mass that is the celebration of the birth of Jesus Christ. That is why many people go to church on that day. Christmas is celebrated in all countries but in a different way. In Europe it is celebrated on the 25th of December.

As usual people decorate their houses and light candles on the Christmas Eve. There is a tradition to decorate the Christmas tree with baubles, glass balls, toys and tinsel. It started in Germany in the 16th century.

The legend says that Martin Luther, an important Christian leader, was walking home through the forest one Christmas Eve. Suddenly he looked up and saw a beautiful starlit sky. The stars looked like as if they were shining on the fir tree branches. When he came home, he put a small fir tree inside his house and decorated it with lighted candles. In England this tradition was introduced by Prince Albert, the German husband of Queen Victoria.

The English people also hang mistletoe on the doors of their homes. They believe that this plant has magical powers. It can help peaceful and friendly people come in and keep out witches or evil spirits. They put presents under the Christmas tree and still hang stockings at the bedside of their children. The Father Christmas is sure to come at night through the chimney.

In the old times in England people in the streets sang Christmas Carols. The most famous is O Holy Night.

Перевод текста «The Origin of Christmas» с английского в самом конце.

* * *

The Receit of Traditional Christmas Roast Turkey

- One turkey

- 30 g butter, melted

- 200 g cooked rice

- 200 g minced pork

- 2 large onions chopped

- 1 large carrot grated

- 1 /2 bunch parsley, chopped

- Juice of 1/2 lemon

- 100 g sultanas

- One big sour apple

- Salt and pepper to taste

Frozen turkey must be thoroughly thawed before cooking in a cool place. Do not thaw the bird in the refrigerator or in hot water.

Wash the turkey under cold running water, then pat dry with absorbent kitchen paper.

Place all the stuffing ingredients in a large bowl and mix well.

Fill the turkey with 1 /3 of the stuffing. Do not pack tightly or the skin may split during cooking. Shape remaining stuffing into little balls, stew them.

Truss the turkey.

Place the turkey in a large roasting pan. Brush all over with melted butter and season with salt and pepper. Roast in oven for 2y4 — 23/4 hours.

Remove trussing strings and place the turkey on a dish. Arrange stuffing balls and herbs around the turkey.

Рождественская жареная индейка, фаршированная рисом и овощами (Традиционный рецепт)

- Большая индейка

- 30 г масла, растопленного

- 200 г отварного риса

- 200 г свиного фарша

- 2 большие луковицы

- 1 большая морковь

- 1/2 пучка петрушки, мелко нарубленной

- Сок 1/2 лимона

- 100 г изюма без косточек

- 1 большое кислое яблоко, очищенное и с вырезанной сердцевиной, разрезанное на мелкие дольки

- Соль и перец по вкусу

Разморозить индейку в прохладном месте в течение 20-30 часов, но не в холодильнике или в теплой воде. Промыть ее холодной водой, затем вытереть кухонным бумажным полотенцем.

Положить все ингредиенты для начинки в большую миску и хорошо перемешать.

Нафаршировать индейку 1 /3 начинки. Не кладите начинку слишком плотно, иначе кожица индейки может лопнуть при жарке. Остальную начинку разделайте в виде тефтелей и потушите их отдельно. Свяжите крылышки и ножки птицы.

Положить индейку на большой противень, сбрызнуть маслом, посыпать солью и перцем. Жарить в духовке 2’/4 — 23/4 часа.

Убрать нитки, положить индейку на блюдо, вокруг нее тефтели и зелень.

* * *

Перевод текста про Рождество (Christmas)

[paid_content product_id=»18″]

Начнем с того, что Рождество, это религиозный праздник. Само слово Рождество означает празднование рождения Христа. Вот почему многие люди в этот день идут в церковь. Рождество отмечают в разных странах по-разному. В Европе Рождество отмечают 25 декабря. Обычно люди украшают свои дома и в рождественский вечер зажигают свечи. Существует традиция наряжать елку на Рождество. Она зародилась в Германии в 16 веке. По легенде Мартин Лютер, известный религиозный проповедник, однажды в рождественский вечер шел домой через лес. И вот он взглянул вверх и увидел прекрасное звездное небо. Звезды были видны сквозь ветви елок, казалось висели на них. Когда проповедник пришел домой, он взял маленькую елочку и украсил ее зажженными свечами. Из Германии этот обычай украшать елку привез в Англию принц Альберт, муж королевы Виктории, немец по происхождению.

В Европе и особенно в Англии, еще есть обычай в рождественские дни вешать омелу на дверь. У этого растения, по поверьям, есть магическая сила. Оно впускает в дом добрых людей и держит подальше от вашей двери злых людей и нечистую силу. Также на Рождество люди вешают чулки у изголовья кровати своих детей. Дед Мороз обязательно придет, чтобы положить в них подарки.

[/paid_content]

Еще читайте или смотрите:

As hard to wrap our minds around the fact as it may be, the festive season is almost here. Christmas plans start to become a common topic in conversations, thankfully stealing some of COVID-19’s spotlight. In this article, we dive into the birth of the words we use to talk about Christmas.

Latin is the root of modern Christian words

As with all things related to Christian tradition, the influence of Latin is present in many words surrounding Christmas. Latin was the language of the Roman Empire, which had converted to Christianism by the time it had reached the furthest conquered territories.

Christmas

According to the Catholic Encyclopedia, the word Christmas originates from the phrase “Cristes Maesse”, first recorded in 1038, which means the Mass of Christ or Christ’s Mass. The word mass is the English version of the Latin word missa, a celebration of the Eucharist, done in memory of Jesus Christ, where Christians eat bread and drink wine. But not all is Latin; in fact, the word Christ comes from the Greek word Khristos, translated from the Hebrew term messiah, which means anointed.

Festive, Advent and Nativity

The word festive comes from the Latin term for feast: festivus. It originally meant joyous, gay and merry. It is also related to festum which means festival or holiday. Advent originates from the Latin adventus, a term for arrival or approach, referring to the coming of Christ. Thank you Latin!

Nativity also comes from a Latin family of words: nativus, nativitas, nativitatem, referring to being born and birth. The word made its way to English via French influence, probably during the Norman Conquest of the British Isles, during the 11th century.

Carol

The word carol appears to have its roots in the Latin term choraula, also in the root of choral as it referred to a musician who accompanies a chorus by playing a reed instrument (a type of flute). The world carol was used in medieval times to refer to a dance carried out in circles, usually performed during pagan celebrations. It was a type of folk music that Christians later adapted to religious themes, thus becoming the Christmas carol we know today.

Food and drinks: the all-time Christmas protagonists

Christmas pudding

The English and Irish tradition of having plum pudding at Christmas was carried across the Atlantic and spread out in the “colonies.” Some historians believe that Christmas pudding traditionally had thirteen ingredients, one for Christ and one for each of the Apostles. But current recipes are much simpler.

American lexicographer Noah Webster defined plum pudding as “pudding containing raisins or currants.” The contradictory part of this story is that “pudding” wasn’t originally used to refer to desert but to a mix of meet, spices and blood, that was boiled after being stuffed in the animal’s intestines. But the word meandered along history, eventually becoming associated with rich, sweet foods. Plum pudding is one of such sweet examples, where the word plum refers to the raisins or currants that give it sweetness.

Eggnog

A traditional eggnog recipe includes rum, Bourbon or cognac (sometimes more than one), milk or cream, sugar, raw eggs and spices. For an extra frothy texture, some recipes involve whipping the egg whites separately. Eggnog became traditionally associated with Christmas because of its spicy flavor, including vanilla, nutmeg and sometimes cloves.

The word is believed to have been first used in writing circa 1775, by American priest and philologist Jonathan Boucher. He had a Glossary of Archaic and Provincial Words where he defined eggnog as “a heavy and unwholesome, but not unpalatable, strong drink, made of rum beaten up with the yolks of raw eggs.”

Sugarplum

The term sugarplum was first used to describe a method for fruit preservation – boiling fruit with sugar – and it slowly became the general term for what we currently know as candy. In fact, sugarplum is not a plum at all, but a series of layers of hardened sugar, in a round or oval shape. The word quickly became associated with Christmas because of poems and plays. If you have ever watched The Nutcracker by Tchaikovsky, you are familiar with the Sugar Plum Fairy, who rules The Land of the Sweets.

Santa and the present tradition were born in Turkey

The beauty of rituals, symbols and words is that they carry meaning and symbolism from many different cultures and times in history. Christmas is no exception. You may find it surprising that the following terms have become what they are today by being in contact with many different cultures.

Santa Claus

The name Santa Claus refers to Saint Nicholas the saint patron of Children because, who was born in present-day Turkey around the year 280. As a young man who had lost both his parents, he decided to give away his inheritance to help the poor and he later became a clergyman. The tradition of giving presents to emulate him became popular in Northern Europe until the 1500s, thanks to his reputation for performing miracles. Dutch settlers, who had nicknamed him Sinterklaas, carried the term to the USA, where the word slowly turned into Santa Claus. This is a word that has truly traveled the world, bringing tradition and meaning everywhere it went!

Crèche

Crèche is defined as “representation of the Nativity” by Merriam-Webster and it is a French term. Before its current form, the word was sometimes spelled as cratch or crache. All of these forms originally referred to a trough from where animals eat. In case you are unfamiliar with the biblical story, this is where baby Jesus was first laid to rest after his birth, as the scene took place in a stable. Interestingly, the feeding container was eventually named manger, which is its current meaning in English. In its original French, manger however means to eat. In summary, we use: a) the French word for cradle to speak about the Nativity and b) the French term for eating to refer to a feeding box for animals.

References

https://www.merriam-webster.com/words-at-play/christmas-word-origins

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Nutcracker

Phillips, Andrew (1995). Orthodox Christianity and the English tradition. Anglo-Saxon Books. p. 141. ISBN 9781898281009.

https://www.catholic.org/encyclopedia/

https://www.etymonline.com/

https://www.biography.com/religious-figure/saint-nicholas

https://www.independent.co.uk/arts-entertainment/books/where-words-you-use-christmas-originate-a6765011.html

- Afrikaans: Kersfees (af)

- Albanian: Krishtlindja (sq), Kërshëndella

- Alutiiq: Aʀusistuaq

- Amharic: ገና (gäna)

- Arabic: عِيد الْمِيلَاد m (ʕīd al-mīlād), الْمِيلَاد (ar) m (al-mīlād), الْكْرِيسْمَاس m (al-krismas)

- Egyptian Arabic: عيد الملاد m (ʿīd il-milād)

- Hijazi Arabic: الكرسمس m (al-krismis, al-krismas)

- Armenian: Սուրբ Ծնունդ (Surb Cnund)

- Aromanian: Crãciun

- Assamese: বৰদিন (bordin)

- Assyrian Neo-Aramaic: ܥܹܐܕܵܐ ܕܡܵܘܠܵܕܵܐ m (ʿēda d-mawlada), ܥܹܐܕܵܐ ܙܥܘܿܪܵܐ m (ʿēda zʿora)

- Asturian: navidá (ast) f, ñavidá (ast) f

- Azerbaijani: Milad

- Basque: Eguberri (eu)

- Bavarian: Weihnåchtn

- Cimbrian: Boinichtn

- Mòcheno: Bainechtn

- Belarusian: каля́ды f pl (kaljády), Раство́ n (Rastvó), Ражджаство́ n (Raždžastvó), Ражаство́ n (Ražastvó), Нараджэ́нне Хрысто́ва n (Naradžénnje Xrystóva)

- Bengali: বড়দিন (bn) (bôṛôdin)

- Bikol Central: Pasko

- Breton: Nedeleg (br) m

- Bulgarian: Коледа (bg) f (Koleda), Рождество Христово n (Roždestvo Hristovo)

- Burmese: ခရစ္စမတ် (my) (hka.racca.mat), နာတာလူးပွဲ (my) (natalu:pwai:)

- Catalan: Nadal (ca) m

- Cherokee: ᏓᏂᏍᏓᏲᎯᎲ (danisdayohihv)

- Chichewa: Khirisimasi

- Chinese:

- Cantonese: 聖誕節/圣诞节 (sing3 daan3 zit3)

- Hakka: 聖誕節/圣诞节 (Sṳn-tan-chiet)

- Mandarin: 聖誕節/圣诞节 (zh) (Shèngdànjié), 耶誕節/耶诞节 (zh) (Yēdànjié, Yédànjié) (Taiwan)

- Min Nan: 聖誕/圣诞 (zh-min-nan) (Sèng-tàn), 耶誕/耶诞 (zh-min-nan) (Iâ-tàn)

- Chuukese: Kirisimas

- Chuvash: Раштав (Raštav)

- Cornish:

- Standard Cornish: Nadelyk

- Unified Cornish: Nadelek

- Czech: Boží hod m, Vánoce (cs) pl

- Danish: jul (da) c

- Dutch: Kerstmis (nl) m, kerst (nl) m

- Dzongkha: ཡེ་ཤུའི་འཁྲུངས་སྟོན (ye shu’i ‘khrungs ston)

- Esperanto: kristnasko

- Estonian: jõulud (et) pl

- Ewe: Blunya

- Faroese: jól (fo) n pl

- Finnish: joulu (fi)

- French: Noël (fr) m

- Friulian: Nadâl

- Galician: Nadal (gl) m

- Georgian: შობა (ka) (šoba)

- German: Weihnachten (de) n

- Alemannic German: Wiehnachte

- Silesian: Weihnachta, Weihnachten

- Greek: Χριστούγεννα (el) n pl (Christoúgenna)

- Greenlandic: juulli (kl)

- Guaraní: Arareñói

- Gujarati: નાતાલ f (nātāl)

- Hausa: Kirsimati

- Hawaiian: Kalikimaka, Kalikamaka

- Hebrew: חַג הַמּוֹלָד (he) (khag ha’molad)

- Hindi: क्रिसमस m (krismas), क्रिस्मस m (krismas), बड़ा दिन m (baṛā din), ईद-ए-तवल्लुद m (īd-e-tavallud), ईद-ए-विलादत m (īd-e-vilādat)

- Hungarian: karácsony (hu)

- Hunsrik: Weinachte n

- Icelandic: jól (is) n pl

- Inari Sami: juovlah pl

- Indonesian: Natal (id)

- Ingrian: Joulu

- Irish: Nollaig (ga) f

- Old Irish: Notlaic f

- Italian: Natale (it) m

- Japanese: クリスマス (ja) (Kurisumasu), 聖誕祭 (ja) (せいたんさい, Seitansai), 聖誕節 (ja) (せいたんせつ, Seitansetsu)

- Javanese: Natal

- Kannada: ಕ್ರಿಸ್ಮಸ್ (krismas)

- Karelian: Rastavu

- Kazakh: Рождество (Rojdestvo)

- Khmer: ណូអែល (nouʼael), បុណ្យណូអែល (bon nouʼael)

- Konkani: नाताळ (nātāḷ)

- Korean: 크리스마스 (ko) (Keuriseumaseu), 성탄절 (ko) (Seongtanjeol)

- Kurdish:

- Northern Kurdish: gaxan (ku), noel (ku), krismas (ku)

- Kyrgyz: Рождество (Rojdestvo)

- Ladin: Nadel m

- Ladino: Noel

- Lakota: Wóšpipi, Wóšpipi Káǧapi

- Lao: ຄິດສະມາດ (khit sa māt), ໂນແອນ (nō ʼǣn), ບົນໂນແອນ (bon nō ʼǣn)

- Latin: festum Nativitatis Domini, Nātīvitās f, Christi Natalis

- Latvian: Ziemassvētki m pl, Ziemsvētki m pl

- Lithuanian: Kalėdos (lt) f pl

- Low German:

- German Low German: Wiehnachten n

- Lule Sami: javlla

- Luxembourgish: Chrëschtdag (lb) m

- Macedonian: Божиќ m (Božiḱ)

- Malay: Hari Natal, Krismas

- Malayalam: ക്രിസ്തുമസ് (kristumasŭ)

- Maltese: Milied m

- Manx: Nollick f, Nollick Vooar f

- Maori: Kirihimete

- Marathi: नाताळ m (nātāḷ)

- Mòcheno: bainechtn pl

- Marshallese: Kūrijm̧ōj

- Middle English: Cristemasse

- Mingrelian: ქირსე (kirse)

- Mon: တ္ၚဲခရေတ်သမာတ် (mnw), ခရေတ်သမာတ် (mnw)

- Mongolian: Зул сар (Zul sar), Христосын мэндэлсэн өдөр (Xristosyn mendelsen ödör)

- Navajo: Késhmish

- Nepali: क्रिसमस (krisamas)

- Norman: Noué m

- Northern Sami: juovllat pl

- Norwegian:

- Bokmål: jul (no) m or f

- Nynorsk: jol f, jul f

- Occitan: Nadal (oc) m

- Ofo: noⁿˊpi

- Ojibwe: niibaanamom

- Old English: ġēol n, Cristes mæsse f, midwinter m

- Old Norse: jól n pl

- Oriya: ବଡ଼ ଦିନ (or) (bôṛô dinô), କିସ୍ମସ୍ (or) (kismôs)

- Papiamentu: Pasku

- Pashto: کریمیس

- Persian: کریسمس (fa) (krismas), عید میلاد مسیح (‘eyd-e milâd-e masih), عید نوئل (fa) (‘eyd-e no’el)

- Pite Sami: jåvvlå

- Plautdietsch: Wienachten f

- Polish: Boże Narodzenie (pl) n

- Portuguese: Natal (pt) m

- Punjabi: ਵੱਡਾ ਦਿਨ (vaḍḍā din), ਕ੍ਰਿਸਮਸ (krismas)

- Romagnol: Nadêl m

- Romanian: Crăciun (ro) n, Nașterea lui Isus Cristos f, Nașterea Domnului f

- Russian: Рождество́ Христо́во (ru) n (Roždestvó Xristóvo), Рождество́ (ru) n (Roždestvó), Кри́стмас m (Krístmas) (colloquial, foreign context or foreign communities)

- Rusyn: Ріство́ n (Ristvó)

- Santali: ᱢᱟᱨᱟᱝ ᱢᱟᱦᱟᱸ (maraṅ mahã)

- Scots: Yule

- Scottish Gaelic: Nollaig f

- Serbo-Croatian:

- Cyrillic: Божић m, Рождество n

- Roman: Božić m, Roždestvo (sh) n

- Sicilian: Natali (scn)

- Sindhi: ڪرسمس (sd)

- Sinhalese: නත්තල (nattala)

- Skolt Sami: rosttov

- Slovak: Vianoce (sk) f pl

- Slovene: Bôžič (sl) m

- Sorbian:

- Lower Sorbian: gódy pl

- Upper Sorbian: hody m pl

- Sotho: Kresemese

- Southern Sami: jåvlh pl

- Spanish: Navidad (es) f, Crismes m (New Mexico)

- Sranan Tongo: Bedaki, kresneti

- Swahili: Krismasi

- Swedish: jul (sv) c

- Tagalog: Pasko (tl)

- Tajik: Мавлуди Исо (tg) (Mavludi Iso), Кристмас (Kristmas)

- Tamil: கிசிமிசி (kicimici), கிறிஸ்மஸ் (kiṟismas), கிறித்துமசு (ta) (kiṟittumacu), கிறிஸ்துமஸ் (ta) (kiṟistumas), நத்தார் (nattār)

- Tatar: Раштуа (Raştua)

- Telugu: క్రిస్మస్ (krismas)

- Thai: คริสต์มาส (th) (krís-mâas), คริสตสมภพ (krít-dtà-sǒm-póp)

- Tibetan: ཡེ་ཤུའི་འཁྲུངས་སྐར (ye shu’i ‘khrungs skar)

- Turkish: Noel (tr)

- Turkmen: Isanyň dogluşy, roždestwo, milad

- Ukrainian: Різдво́ (uk) n (Rizdvó), Різдво́ Христо́ве n (Rizdvó Xrystóve)

- Ume Sami: juvlla

- Urdu: کرسمس m (krismas), بڑا دن m (baṛā din), عید تولد m (īd-e-tavallud), عید ولادت m (īd-e-vilādat)

- Uyghur: روجدېستۋو (rojdëstwo), روجىستىۋا (rojistiwa)

- Uzbek: Mavlud, Rojdestvo (uz)

- Vietnamese: Nô-en, Giáng sinh (vi)

- Vilamovian: Waeinahta f, Wajnaochta f

- Volapük: kritid (vo), kritidazäl (vo)

- Walloon: Noyé (wa) m or f

- Welsh: Nadolig (cy) m

- West Frisian: Krysttiid

- Yiddish: ניטל m (nitl)

- Yup’ik: Alussistuaq, Selavi

- Zulu: Ukhisimuzi

- Top Definitions

- Quiz

- More About Christmas

- Examples

- British

- Cultural

[ kris-muhs ]

/ ˈkrɪs məs /

noun

the annual festival of the Christian church commemorating the birth of Jesus: celebrated on December 25 and now generally observed as a legal holiday and, for many, an occasion for exchanging gifts.

adjective

of or relating to Christmas; made or displayed for Christmas: six batches of Christmas cookies;a Christmas movie for the whole family.

VIDEO FOR CHRISTMAS

When Exactly Are The 12 Days Of Christmas?

Are there actually 12 Days of Christmas? And if so when are they? Let’s take a little stroll down Christmas Carol lane to find out …

MORE VIDEOS FROM DICTIONARY.COM

QUIZ

CAN YOU ANSWER THESE COMMON GRAMMAR DEBATES?

There are grammar debates that never die; and the ones highlighted in the questions in this quiz are sure to rile everyone up once again. Do you know how to answer the questions that cause some of the greatest grammar debates?

Which sentence is correct?

Origin of Christmas

First recorded before 1050; Middle English cristmas(se); Old English Cristes mǣsse Mass of Christ

OTHER WORDS FROM Christmas

Christ·mas·sy, Christ·mas·y, adjectivepost-Christ·mas, adjectivepre-Christ·mas, adjective

Words nearby Christmas

Christine de Pisan, Christingle, Christless, Christlike, Christly, Christmas, Christmas beetle, Christmasberry, Christmas box, Christmas cactus, Christmas card

Dictionary.com Unabridged

Based on the Random House Unabridged Dictionary, © Random House, Inc. 2023

MORE ABOUT CHRISTMAS

What does Christmas mean?

Christmas is a Christian holiday to celebrate the birth of Jesus, the central figure of Christianity. Most Christians celebrate the holiday on December 25, but it is celebrated on January 7 in the Orthodox Church due to the use of a different calendar.

Christmas is also widely observed in secular (nonreligious) ways. Popular activities include the decoration of a Christmas tree and the exchange of gifts.

Most often, the word Christmas refers to Christmas Day—the day on which the holiday is observed, most commonly December 25. The day or evening before Christmas is called Christmas Eve.

Christmas is also often used to refer to the entire Christmas season, as in Even though it lasts for several weeks, Christmas always seems to go by so quickly. Another word for the Christmas season is Christmastime. Generally, the season begins around the beginning of December, though some people in the U.S. begin to decorate or engage in Christmas festivities immediately after the Thanksgiving holiday or even before. The Christmas season coincides with the “holiday season,” which in the U.S. is popularly understood to include Thanksgiving, Hanukkah, Christmas, Kwanzaa, New Year’s Eve, and New Year’s Day. Due to its widespread observance, Christmas is one of the federal holidays in the U.S.

In religious terms, the Christmas season is sometimes considered to extend from Christmas Eve to the feast of the Epiphany or Twelfth Day on January 6. This period is sometimes called Christmastide, though this word can also be used in a more general way to refer to the period from Christmas Eve to New Year’s Day.

The word Christmas is commonly used as a modifier in the names of many items and activities associated with the celebration of Christmas, as in Christmas cards, Christmas lights, Christmas shopping, Christmas cookies, Christmas carols, Christmas music, Christmas movies, Christmas stockings, and Christmas presents.

Traditional Christmas greetings include Merry Christmas and Happy Christmas (which is more popular in the U.K.).

By those who celebrate it, Christmas is often seen as a magical time that’s associated with a sense of hope and wonder and a feeling of festiveness. This is often what people are expressing when they describe something as Christmassy or say that they are in the Christmas spirit.

Example: This is Christmas, the season of perpetual hope!

Where does Christmas come from?

The first records of the word Christmas in English come from before 1050. It comes from the Old English Cristes mǣsse, meaning “Mass of Christ.” The word Christ means “anointed one” or “messiah” and is the title given to Jesus (as in Jesus Christ) by Christians due to their belief that he is the messiah who brings salvation. The words Christianity and Christian are based on the word Christ.

In the Middle Ages, the word mass referred to a religious feast day in honor of a specific person. This is what’s referred to by the ending -mas, which is used in the names of Christian holidays. By far the most well-known holiday that uses this ending is Christmas, but there are others, including Candlemas and Michaelmas.

The celebration of Christmas may date to around the year 200, but it did not become widespread as a holiday until much later, around the Middle Ages. Today, Christians often attend church on Christmas Eve or Christmas morning. Much of the religious observance of Christmas involves the story of Jesus’s birth in a stable in the town of Bethlehem. Some Christians set up Nativity scenes depicting the scene of Jesus’s birth, including figures of Mary, Joseph, and the baby Jesus in a manger. For many Christians, religious observation of Christmas is done alongside other secular aspects of the season, such as the exchange of gifts and Santa Claus.

This sometimes leads to criticism among Christians that Christmas has become too secularized and commercialized. The abbreviation Xmas, for example, is sometimes seen as inappropriate, perhaps due to its replacement of the name Christ or its widespread use in commercial contexts, such as in advertising. However, the X is Xmas isn’t an arbitrary placeholder. The abbreviation, which in fact dates back to at least the mid-1500s, uses X because it is the Greek letter chi, the initial letter in the Greek word Χριστός (Chrīstos), meaning “Christ.”

Other names for Christmas include Noel and Nativity, which are typically used in religious contexts. The word yule is sometimes used as another word for Christmas or Christmastime, but it is rooted in and is also used as a name for the celebration of the Winter Solstice that’s observed in some Pagan traditions. Some of these customs influenced the ways that Christmas is celebrated.

Did you know … ?

How is Christmas used in real life?

Christmas is one of the most important Christian holidays, but it is also widely celebrated in nonreligious ways.

I’m celebrating Christmas with family and friends today, and then I’m volunteering during the overnight shift at the warming center for the homeless. Take care of each other today!

— Belle 🏰 Resists (@BelleResist) December 25, 2017

Merry Christmas everyone!! 🎄⭐

I know there are 116 days until then, however that doesn’t matter 😂😂

I’m always in the Christmas Spirit!— StardashieVTFOE 🌲🎄🎃🎉 (@stardashie) September 1, 2020

I still have my Snuggie and honestly it’s probably the best and most durable Christmas gift I’ve ever received 🥰

— shuggahoneyicedtea (@_kourtneylee_) August 31, 2020

Try using Christmas!

True or False?

All Christians celebrate Christmas on December 25.

How to use Christmas in a sentence

-

The cash that remained from his Christmas gift left enough to buy boots or a TV, but not both.

-

Like, the Christmas cards you make might not be seen in stores for a full calendar year.

-

That is why so many school systems recognize Christmas and Easter.

-

I know it’s hard — it was hard at Christmas, Thanksgiving, New Year’s — but I hope people, if you’re watching, be careful.

-

Super Bowl parties are going to be as big of a problem as gatherings at Thanksgiving and Christmas were, and we do know for sure those gatherings did influence the increase in cases that we’re seeing right now.

-

In the wee hours of Christmas morning, a flight deal was shared in an exclusive Facebook group for urban travelers.

-

Plenty of Jewish kids today grow up with a Christmas tree next to their menorah.

-

This is the first Christmas I can remember when the news was all about cops and race.

-

So this is Christmas, as the song goes, and what have we done?

-

And that was well before this Christmas, when he appeared to joke about Obama being a Muslim.

-

He staggered along with much difficulty and managed to complete half of it by Christmas.

-

He was released soon after Christmas, and another Vicar filleth his place.

-

And when cool silence came again, Hugh begged that the two would have their Christmas Eve dinner with him, at his hotel.

-

She looked radiantly beautiful, and as happy as if her soul were singing a Christmas Carol.

-

«She’s given me the pleasure of making Christmas come all over again, to-morrow, that’s all,» said Hugh.

British Dictionary definitions for Christmas

noun

- the annual commemoration by Christians of the birth of Jesus Christ on Dec 25

- Also called: Christmas Day Dec 25, observed as a day of secular celebrations when gifts and greetings are exchanged

- (as modifier)Christmas celebrations

Also called: Christmas Day (in England, Wales and Ireland) Dec 25, one of the four quarter daysCompare Lady Day, Midsummer’s Day, Michaelmas

Also called: Christmastide the season of Christmas extending from Dec 24 (Christmas Eve) to Jan 6 (the festival of the Epiphany or Twelfth Night)

Word Origin for Christmas

Old English Crīstes mæsse Mass of Christ

Collins English Dictionary — Complete & Unabridged 2012 Digital Edition

© William Collins Sons & Co. Ltd. 1979, 1986 © HarperCollins

Publishers 1998, 2000, 2003, 2005, 2006, 2007, 2009, 2012

Cultural definitions for Christmas

A festival commemorating the birth of Jesus, traditionally celebrated on December 25 by most Western Christian churches. Although dating to probably as early as a.d. 200, the feast of Christmas did not become widespread until the Middle Ages. Today, Christmas is largely secularized and dominated by gifts, decorated trees, and a jolly Santa Claus.

The New Dictionary of Cultural Literacy, Third Edition

Copyright © 2005 by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company. Published by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company. All rights reserved.

Christmas commemorates the birth of Jesus. This scene, by Florentine painter Fra Angelico, portrays Jesus’ birth in Bethlehem. (Adorazione del Bambino (Adoration of the Child), 1439-1443.)

Christmas or Christmas Day commemorates and celebrates the birth of Jesus. The word Christmas is derived from Middle English Christemasse and from Old English Cristes mæsse.[1] It is a contraction meaning «Christ’s mass.» The name of the holiday is sometimes shortened to Xmas because Roman letter «X» resembles the Greek letter Χ (chi), an abbreviation for Christ (Χριστός).

Christmas in the West is traditionally observed on December 25, or January 7 in the Eastern Orthodox Churches. In most Christian communities, the holiday is celebrated with great cheer, song, exchange of gifts, storytelling and family gatherings. The popularity of Christmas is due in large part to the «spirit of Christmas,» a spirit of charity expressed through gift-giving and acts of kindness that celebrate the human heart of the Christian message.

Besides its Christian roots, many Christmas traditions have their origins in pagan winter celebrations. Examples of winter festivals that have influenced Christmas include the pre-Christian festivals of Yule, and Roman Saturnalia.[2]

While Christmas began as a religious holiday, it has appropriated many secular characteristics over time, including many variations of the Santa Claus myth, decoration and display of the Christmas tree, and other aspects of consumer culture. Many distinct regional traditions of Christmas are still practiced around the world, despite the widespread influence of Anglo-American Christmas motifs disseminated in popular culture.

History

Origins of the holiday

The historical development of Christmas is quite fascinating. According to the Bible, Jesus’ birth was celebrated by many well-wishers including the Magi who came bearing gifts. The early Christians in the Roman Empire wished to continue this practice but found that celebrating Jesus’ birth was very dangerous under Roman rule, where being a Christian could be punishable by death. Thus, Christians began to celebrate Christ’s birthday on December 25, which was already an important pagan festival, in order to safely adapt to Roman customs while still honoring Jesus’ birth.

This is how Christmas came to be celebrated on the Roman holiday of Saturnalia, and it was from the pagan holiday that many of the customs of Christmas had their roots. The celebrations of Saturnalia included the making and giving of small presents (saturnalia et sigillaricia). This holiday was observed over a series of days beginning on December 17 (the birthday of Saturn), and ending on December 25 (the birthday of Sol Invictus, the «Unconquered Sun»). The combined festivals resulted in an extended winter holiday season. Business was postponed and even slaves feasted. There was drinking, gambling and singing, and nudity was relatively common. It was the «best of days,» according to the poet Catullus.[3]

The feast of Sol Invictus on December 25 was a sacred day in the religion of Mithraism, which was widespread in the Roman Empire. Its god, Mithras, was a solar deity of Persian origin, identified with the Sun. It displayed its unconquerability as «Sol Invictus» when it began to rise higher in the sky following the Winter Solstice—hence December 25 was celebrated as the Sun’s birthday. In 274 C.E., Emperor Aurelian officially designated December 25 as the festival of Sol Invictus.

Evidence that early Christians were observing December 25 as Jesus’ birthday comes from Sextus Julius Africanus’s book Chronographiai (221 C.E.), an early reference book for Christians. Yet from the first, identification of Christ’s birth with a pagan holiday was controversial. The theologian Origen, writing in 245 C.E., denounced the idea of celebrating the birthday of Jesus «as if he were a king pharaoh.» Thus Christmas was celebrated with a mixture of Christian and secular customs from the beginning, and remains so to this day.

Furthermore, in the opinion of many theologians, there was little basis for celebrating Christ’s birth in December. Around 220 C.E., Tertullian declared that Jesus died on March 25. Although scholars no longer accept this as the most likely date for the crucifixion, it does suggest that the 25th day of the month—March 25 being nine months before December 25th—had significance for the church even before it was used as a basis to calculate Christmas. Modern scholars favor a crucifixion date of April 3, 33 C.E. (These are Julian calendar dates. Subtract two days for a Gregorian date), the date of a partial lunar eclipse.[4] By 240 C.E., a list of significant events was being assigned to March 25, partly because it was believed to be the date of the vernal equinox. These events include the creation, the fall of Adam, and, most relevantly, the Incarnation.[5] The view that the Incarnation occurred on the same date as crucifixion is consistent with a Jewish belief that prophets died at an «integral age,» either an anniversary of their birth or of their conception.[6][7]

Impetus for the celebration of Christmas increased after Constantius, son of Emperor Constantine, decreed that all non-Christian temples in the empire be immediately closed and anyone who still offered sacrifices of worship to the gods and goddesses in these temples was to be put to death. The followers of Mithras were eventually forced to convert under these laws. In spite of their conversion, they adapted many elements of their old religions into Christianity. Among these, was the celebration of the birth of Mithras on December 25, which was now observed as the birthday of Jesus.

Another impetus for official Roman support for Christmas grew out of the Christological debates at the time of Constantine. The Alexandrian school argued that he was the divine word made flesh (see John 1:14), while the Antioch school held that he was born human and infused with the Holy Spirit at the time of his baptism (see Mark 1:9-11). A feast celebrating Christ’s birth gave the church an opportunity to promote the intermediate view that Christ was divine from the time of his incarnation.[8] Mary, a minor figure for early Christians, gained prominence as the theotokos, or god-bearer. There were Christmas celebrations in Rome as early as 336 C.E. December 25 was added to the calendar as a feast day in 350 C.E.[8]

Medieval Christmas and related winter festivals

Christmas soon outgrew the Christological controversy that created it and came to dominate the Medieval calendar.

The 40 days before Christmas became the «forty days of Saint Martin,» now Advent. Former Saturnalian traditions were attached to Advent. Around the twelfth century, these traditions transferred again to the «twelve days of Christmas» (i.e., Christmas to Epiphany).[8]

The fortieth day after Christmas was Candlemas. The Egyptian Christmas celebration on January 6 was adopted as Epiphany, one of the most prominent holidays of the year during Early Middle Ages. Christmas Day itself was a relatively minor holiday, although its prominence gradually increased after Charlemagne was crowned on Christmas Day in 800 C.E.

Northern Europe was the last part to Christianize, and its pagan celebrations had a major influence on Christmas. Scandinavians still call Christmas Jul (Yule or Yultid), originally the name of a 12-day pre-Christian winter festival. Logs were lit to honor Thor, the god of thunder, hence the «Yule log.» In Germany, the equivalent holiday is called Mitwinternacht (mid-winter night). There are also 12 Rauhnächte (harsh or wild nights).[9]

By the High Middle Ages, Christmas had become so prominent that chroniclers routinely noted where various magnates «celebrated Christmas.» King Richard II of England hosted a Christmas feast in 1377 at which 28 oxen and three hundred sheep were eaten.[8] The «Yule boar» was a common feature of Medieval Christmas feasts. Caroling also became popular. Various writers of the time condemned caroling as lewd (largely due to overtones reminiscent of the traditions of Saturnalia and Yule).[8] «Misrule»—drunkenness, promiscuity, gambling—was also an important aspect of the festival. In England, gifts were exchanged on New Year’s Day, and there was special Christmas ale.[8]

The Reformation and modern times

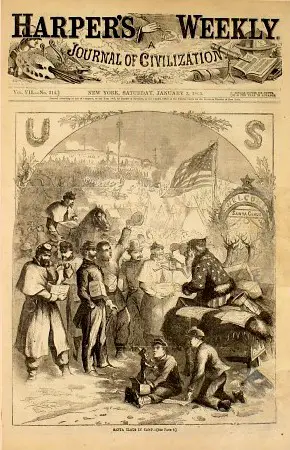

Santa Claus hands out gifts to Union soldiers during the American Civil War in Thomas Nast’s first Santa Claus cartoon, Harper’s Weekly, 1863.

During the Reformation, Protestants condemned Christmas celebration as «trappings of popery» and the «rags of the Beast.» The Catholic Church responded by promoting the festival in a more religiously oriented form. When a Puritan parliament triumphed over the King, Charles I of England (1644), Christmas was officially banned (1647). Pro-Christmas rioting broke out in several cities. For several weeks, Canterbury was controlled by the rioters, who decorated doorways with holly and shouted royalist slogans.[10] The Restoration (1660) ended the ban, but Christmas celebration was still disapproved of by the Anglican clergy.

By the 1820s, sectarian tension had eased and British writers began to worry that Christmas was dying out. They imagined Tudor Christmas as a time of heartfelt celebration, and efforts were made to revive the holiday. Prince Albert, from Bavaria, married Queen Victoria in 1840, introducing the German tradition of the ‘Christmas tree’ into Windsor castle in 1841. The book A Christmas Carol (1843) by Charles Dickens played a major role in reinventing Christmas as a holiday emphasizing family, goodwill, and compassion (as opposed to communal celebration and hedonistic excess).[11]

The Puritans of New England disapproved of Christmas and celebration was outlawed in Boston (1659-1681). Meanwhile, Christians in Virginia and New York celebrated freely. Christmas fell out of favor in the U.S. after the American Revolution, when it was considered an «English custom.» Interest was revived by several short stories by Washington Irving in The Sketch Book of Geoffrey Crayon (1819) and by «Old Christmas» (1850) which depict harmonious warm-hearted holiday traditions Irving claimed to have observed in England. Although some argue that Irving invented the traditions he describes, they were imitated by his American readers. German immigrants and the homecomings of the Civil War helped promote the holiday. Christmas was declared a federal holiday in the United States in 1870.

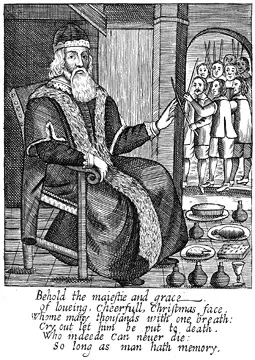

Father Christmas persuades the jury of his innocence in The Examination and Tryal of Father Christmas (1686) by Josiah King[12]

Washington Irving, in his fake book purportedly written by by a man named Diedrich Knickerbocker, wrote of Saint Nicholas «riding over the tops of the trees, in that selfsame waggon wherein he brings his yearly presents to children.»[13] The connection between Santa Claus and Christmas was popularized by the poem «A Visit from Saint Nicholas» (1822) by Clement Clarke Moore, which depicts Santa driving a sleigh pulled by reindeer and distributing gifts to children. His image was created by German-American cartoonist Thomas Nast (1840-1902), who drew a new image annually beginning in 1863.[14] By the 1880s, Nast’s Santa had evolved into the form we now recognize. The image was popularized by advertisers in the early twentieth century.[15]

In the midst of World War I, there was a Christmas truce between German and British troops in France (1914). Soldiers on both sides spontaneously began to sing Christmas carols and stopped fighting. The truce began on Christmas Day and continued for some time afterward. There was even a soccer game between the trench lines in which Germany’s 133rd Royal Saxon Regiment is said to have bested Britain’s Seaforth Highlanders 3-2.

The Nativity

According to tradition, Jesus was born in the town of Bethlehem in a stable, surrounded by farm animals and shepherds, and Jesus was born into a manger from the Virgin Mary assisted by her husband Joseph.

Remembering or re-creating the Nativity (the birth of Jesus) is one of the central ways that Christians celebrate Christmas. For example, the Eastern Orthodox Church practices the Nativity Fast in anticipation of the birth of Jesus, while the Roman Catholic Church celebrates Advent. In some Christian churches, children often perform plays re-creating the events of the Nativity, or sing some of the numerous Christmas carols that reference the event. Many Christians also display a small re-creation of the Nativity known as a crèche or Nativity scene in their homes, using small figurines to portray the key characters of the event. Live Nativity scenes are also re-enacted using human actors and live animals to portray the event with more realism.

Economics of Christmas

Christmas has become the greatest annual economic stimulus for many nations. Sales increase dramatically in almost all retail areas and shops introduce new merchandise as people purchase gifts, decorations, and supplies. In the United States, the Christmas shopping season generally begins on «Black Friday,» the day after Thanksgiving, celebrated in the United States on the third Thursday of November. «Black» refers to turning a profit, as opposed to the store being «in the red.» Many stores begin stocking and selling Christmas items in October/November (and in the UK, even September/October).

Gifts under a Christmas tree.

More businesses and stores close on Christmas Day than any other day of the year. In the United Kingdom, the Christmas Day (Trading) Act 2004 prevents all large shops from trading on Christmas Day.

Most economists agree, however, that Christmas produces a deadweight loss under orthodox microeconomic theory, due to the surge in gift-giving. This loss is calculated as the difference between what the gift giver spent on the item and what the gift receiver would have paid for the item. It is estimated that in 2001 Christmas resulted in a $4 billion deadweight loss in the U.S. alone.[16] Because of complicating factors, this analysis is sometimes used to discuss possible flaws in current microeconomic theory.

In North America, film studios release many high-budget movies in the holiday season, including Christmas theme films, fantasy movies, or high-tone dramas with rich production values.

Santa Claus and other bringers of gifts

In Western culture, the holiday is characterized by the exchange of gifts among friends and family members, some of the gifts being attributed to Santa Claus (also known as Father Christmas, Saint Nicholas, Saint Basil and Father Frost).

Father Christmas predates the Santa Claus character, and was first recorded in the fifteenth century,[17] but was associated with holiday merrymaking and drunkenness. Santa Claus is a variation of a Dutch folk tale based on the historical figure Saint Nicholas, or Sinterklaas, who gave gifts on the eve of his feast day of December 6. He became associated with Christmas in nineteenth century America and was renamed Santa Claus or Saint Nick. In Victorian Britain, Father Christmas’s image was remade to match that of Santa. The French equivalent of Santa, Père Noël, evolved along similar lines, eventually adopting the Santa image.

In some cultures Santa Claus is accompanied by Knecht Ruprecht, or Black Peter. In other versions, elves make the holiday toys. His wife is referred to as Mrs. Claus.

The current tradition in several Latin American countries (such as Venezuela) holds that while Santa makes the toys, he then gives them to the Baby Jesus, who is the one who actually delivers them to the children’s homes. This story is meant to be a reconciliation between traditional religious beliefs and modern day globalization, most notably the iconography of Santa Claus imported from the United States.

The Christmas Tree

The Christmas tree is often explained as a Christianization of the ancient pagan idea that evergreen trees like, pine and juniper, symbolize hope and anticipation of a return of spring, and the renewal of life. The phrase «Christmas tree» is first recorded in 1835 and represents the importation of a tradition from Germany, where such trees became popular in the late eighteenth century.[17] Christmas trees may be decorated with lights and ornaments.

Since the nineteenth century, the poinsettia (Euphorbia pulcherrima), an indigenous flowering plant from Mexico, has been associated with Christmas. Other popular holiday plants include holly, red amaryllis, and Christmas cactus (Zygocactus), all featuring the brilliant combination of red and green.

Along with a Christmas tree, the interior of a home may be decorated with garlands, wreaths, and evergreen foliage, particularly holly (Ilex aquifolium or Ilex opaca) and mistletoe (Phoradendron flavescens or Viscum album). In Australia, North and South America, and to a lesser extent Europe, it is traditional to decorate the outside of houses with lights and sometimes with illuminated sleighs, snowmen, and other Christmas figures.

Municipalities often sponsor decorations as well. Christmas banners may be hung from street lights and Christmas trees placed in the town square. While some decorations such as a tree are considered secular in many parts of the world, the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia bans such displays as symbols of Christianity.

In the Western world, rolls of brightly colored paper with secular or religious Christmas motifs are manufactured for the purpose of wrapping gifts.

Regional customs and celebrations

Christmas celebrations include a great number and variety of customs with either secular, religious, or national aspects, which vary from country to country:

After the Russian Revolution, Christmas celebration was banned in that country from 1917 until 1992.

Several Christian denominations, notably the Jehovah’s Witnesses, Puritans, and some fundamentalists, view Christmas as a pagan holiday not sanctioned by the Bible.

In the Southern Hemisphere, Christmas is during the summer. This clashes with the traditional winter iconography, resulting in oddities such as a red fur-coated Santa Claus surfing in for a turkey barbecue on Australia’s Bondi Beach.

Japan has adopted Santa Claus for its secular Christmas celebration, but New Year’s Day is a far more important holiday.

In India, Christmas is often called bada din («the big day»), and celebration revolves around Santa Claus and shopping.

In South Korea, Christmas is celebrated as an official holiday.

In the Netherlands, Saint Nicholas’ Day (December 6) remains the principal day for gift giving while Christmas Day is a more religious holiday.

In much of Germany, children put shoes out on window sills on the night of December 5, and find them filled with candy and small gifts the next morning. The main day for gift giving in Germany is December 24, when gifts are brought by Santa Claus or are placed under the Christmas tree.

In Poland, Santa Claus (Polish: Święty Mikołaj) gives gifts on two occasions: on the night of December 5 (so that children find them on the morning of December 6, (Saint Nicholas Day) and on Christmas Eve (so that children find gifts that same day).

In Hungary, Santa Claus (Hungarian: Mikulás) or for non-religious people Father Winter (Hungarian: Télapó) is often accompanied by a black creature called Krampusz.

In Spain, gifts are brought by the Magi on Epiphany (January 6), although the tradition of leaving gifts under the Christmas Tree on Christmas Eve (December 24) for the children to find and open the following morning has been widely adopted as well. Elaborate «Nacimiento» nativity scenes are common, and a midnight meal is eaten on Noche-Buena, the good night, Christmas Eve.

In Russia, Grandfather Frost brings presents on New Year’s Eve, and these are opened on the same night. The patron saint of Russia is Saint Nicola, the Wonder Worker, in the Orthodox tradition, whose Feast Day is celebrated December 6.

In Scotland, presents were traditionally given on Hogmanay, which is New Year’s Eve. However, since the establishment of Christmas Day as a legal holiday in 1967, many Scots have adopted the tradition of exchanging gifts on Christmas morning.

The Declaration of Christmas Peace has been a tradition in Finland since the Middle Ages. It takes place in the Old Great Square of Turku, Finland’s official Christmas City and former capital.

Social aspects and entertainment

In many countries, businesses, schools, and communities have Christmas celebrations and performances in the weeks before Christmas. Christmas pageants may include a retelling of the story of the birth of Christ. Groups visit neighborhood homes, hospitals, or nursing homes, to sing Christmas carols. Others do volunteer work or hold fundraising drives for charities.

On Christmas Day or Christmas Eve, a special meal is usually served. In some regions, particularly in Eastern Europe, these family feasts are preceded by a period of fasting. Candy and treats are also part of Christmas celebration in many countries.

Another tradition is for people to send Christmas cards, first popularized in London in 1842, to friends and family members. Cards are also produced with secular generic messages such as «season’s greetings» or «happy holidays,» as a gesture of inclusiveness for senders and recipients who prefer to avoid the religious sentiments and symbolism of Christmas, yet still participate in the gaiety of the season.

Christmas in the arts and media

Many fictional Christmas stories capture the spirit of Christmas in a modern-day fairy tale, often with heart-touching stories of a Christmas miracle. Several have become part of the Christmas tradition in their countries of origin.

Among the most popular are Tchaikovsky’s ballet The Nutcracker based on the story by German author E.T.A. Hoffman, and Charles Dickens’ novel A Christmas Carol. The Nutcracker tells of a nutcracker that comes to life in a young German girl’s dream. Charles Dickens’ A Christmas Carol is the tale of the rich and miserly curmudgeon Ebenezer Scrooge. Scrooge rejects compassion, philanthropy, and Christmas until he is visited by the ghosts of Christmas Past, Present and Future, who show him the consequences of his ways.

Some Scandinavian Christmas stories are less cheery than Dickens’. In H. C. Andersen’s The Little Match Girl, a destitute little girl walks barefoot through snow-covered streets on Christmas Eve, trying in vain to sell her matches, and peeking in at the celebrations in the homes of the more fortunate.

In 1881, the Swedish magazine Ny Illustrerad Tidning published Viktor Rydberg’s poem Tomten featuring the first painting by Jenny Nyström of the traditional Swedish mythical character tomte, which she turned into the friendly white-bearded figure and associated with Christmas.

Many Christmas stories have been popularized as movies and television specials. A notable example is the classic Hollywood film It’s a Wonderful Life. Its hero, George Bailey, is a businessman who sacrificed his dreams to help his community. On Christmas Eve, a guardian angel finds him in despair and prevents him from committing suicide by magically showing him how much he meant to the world around him.

«Now it is Christmas again» (1907) by Carl Larsson.

A few true stories have also become enduring Christmas tales themselves. The story behind the Christmas carol Silent Night, and the editorial by Francis P. Church Yes, Virginia, there is a Santa Claus first published in The New York Sun in 1897, are among the most well-known of these.

Radio and television programs aggressively pursue entertainment and ratings through their cultivation of Christmas themes. Radio stations broadcast Christmas carols and Christmas songs, including classical music such as the «Hallelujah chorus» from Handel’s Messiah. Among other classical pieces inspired by Christmas are the Nutcracker Suite, adapted from Tchaikovsky’s ballet score, and Johann Sebastian Bach’s Christmas Oratorio (BWV 248). Television networks add Christmas themes to their standard programming, run traditional holiday movies, and produce a variety of Christmas specials.

Notes

- ↑ «Christmas», The Catholic Encyclopedia, 1913. Retrieved July 17, 2021.

- ↑ The Magical History Of Yule, The Pagan Winter Solstice Celebration The Huffington Post, December 22, 2016. Retrieved July 17, 2021.

- ↑ Julilla Sempronia, Ancient Voices: Saturnalia, AncientWorlds 2004. Retrieved July 17, 2021.

- ↑ Sten Odenwald, Can you date the crucifixion of Jesus Christ using astronomy? 1997. Retrieved July 17, 2021.

- ↑ Frederick Holweck, The Feast of the Annunciation Catholic Encyclopedia, 1907 ed. Retrieved July 17, 2021.

- ↑ Louis Duchesne, Les origines du culte chrétien: Etude sur la liturgie latine avant Charlemagne (Paris, 1889).

- ↑ Thomas J. Talley, Origins of the Liturgical Year (New York: Pueblo Publishing Company, 1991).

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 8.5 Alexander Murray, Medieval Christmas History Today 36(12) (December 1986): 31-39. Retrieved July 17, 2021.

- ↑ Dahna Barnett, Midwinter Traditions Mythic Passages, December 2006. Retrieved July 17, 2021.

- ↑ Chris Durston, Lords of Misrule: The Puritan War on Christmas 1642-60 History Today 35(12) (December 1985): 7-14. Retrieved July 17, 2021.

- ↑ Geoffrey Rowell, Dickens and the Construction of Christmas History Today 43(12) (December 1993): 17-24. Retrieved July 17, 2021.

- ↑ The Examination and Tryal of Old Father Christmas hymnsandcarolsofchristmas. Retrieved July 17, 2021.

- ↑ Washington Irving, A History of New York (Penguin Classics, 2008, ISBN 0143105612).

- ↑ Sam Ursu, The Weird History of Christmas in America December 20, 2017. Retrieved July 17, 2021.

- ↑ David Mikkelson, Did Coca-Cola Invent the Modern Image of Santa Claus? Snopes.com. December 18, 2001. Retrieved July 17, 2021.

- ↑ Is Santa a deadweight loss? The Economist, December 20, 2001. Retrieved July 17, 2021.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Douglas Harper, Christ, Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved July 17, 2021.

References

ISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Duchesne, Louis. Origines Du Culte Chretien: Etude Sur La Liturgie Latine Avant Charlemagne. Nabu Press, 2010. ISBN 1148818758

- Heindel, Max. Mystical Interpretation of Christmas. Holos Arts Project Publishing Company, 1920. ISBN 0911274650

- Irving, Washington. A History of New York. Penguin Classics, 2008. ISBN 0143105612

- Nissenbaum, Stephen. The Battle for Christmas: A Social and Cultural History of Our Most Cherished Holiday. Vintage, 1997. ISBN 0679740384

- Restad, Penne L., Christmas in America: A History. New York, Oxford University Press. 1995. ISBN 0195093003

- Talley, Thomas J. The Origins Of The Liturgical Year. Pueblo Books, 1991. ISBN 0814660754

External Links

All links retrieved July 9, 2021.

- Christmas: The Curious Origins of a Popular Holiday

- Christmas Encyclopaedia Britannica.

- Christmas in India

| Holidays, Observances, and Celebrations in the United States of America | |

|---|---|

|

April Fools’ Day • Arbor Day • Children’s Day • Christmas Day • Christmas Eve • Cinco de Mayo • Columbus Day Earth Day • Easter • Election Day • Father’s Day • Flag Day • Fourth of July Groundhog Day • Grandparent’s Day • Halloween • Juneteenth • Kwanzaa • Labor Day • Lincoln’s Birthday Martin Luther King, Jr. Day • Mardi Gras • May Day • Memorial Day • Mother’s Day New Year’s Day • Patriot’s Day • Presidents Day • St. Patrick’s Day • Super Bowl Sunday • Thanksgiving Valentine’s Day • Veterans Day • Washington’s Birthday • Yom Kippur |

|

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article

in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

- Christmas history

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

- History of «Christmas»

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.