After this question, is there a word for a word where all of its letters are in alphabetical order?

Examples of such words:

- AEGILOPS

- BILLOWY

- ALMOST

(If the word in question is also one of those words, that would be incredible!)

asked Nov 18, 2014 at 12:20

1

You can call them abecedarian words.

Abecedarian is an adjective meaning «being arranged alphabetically». It comes from the Latin abecedarius, which means «alphabetical,» based on the names of the first letters of the Latin alphabet.

For example, below are the terms mentioned in a personal site:

Abecedarian Words: Words with letters in alphabetical order

Strictly Abecedarian Words: Words with letters in alphabetical order without repetitionshttp://www.tanyakhovanova.com/

It is also mentioned in this stackoverflow question:

Counting abecedarian words in a list: Python

answered Nov 19, 2014 at 2:39

ermanenermanen

59k34 gold badges159 silver badges291 bronze badges

1

There are fifty-three such words, but nobody seems to have coined a term for them.

some more examples: biopsy, abort, begin.

answered Nov 18, 2014 at 15:56

CentaurusCentaurus

49.4k47 gold badges163 silver badges291 bronze badges

Excluding the word “a”, the shortest words with letters in alphabetical order, containing only 2 letters, are: am, an, be, is, it, no.

The word ace contains 3 letters in alphabetical order.

There are many words with their letters in alphabetical order that contain 6 letters: abhors, accent, access, almost, biopsy, billow, chintz, effort.

The longest word with letters in alphabetical order is Aegilops (8 letters). Technically, this is a Latin term for North American and Eurasian plants in the grass family, Poaceae (generally known as goatgrasses), that are the wild ancestor of modern domestic wheat. In medicine, an aegilops is an abscess or ulcer in the outer or inner corner of the eye. However, the longest English words with letters in alphabetical order, containing 7 letters are: beefily, billowy.

Number with letters in alphabetical order: forty

Number with letters in reverse alphabetical order: one

Longest word with letters in reverse alphabetical order: punctoschmidtella (17) and spoon-feed (9 letters)

Shortest word with all vowels in alphabetical order: aerious (7 letters)

Longest word with all vowels in alphabetical order: phragelliorhynchus (18 letters), adventitious (12), abstemious (10), facetious (9)

SHARE THE LOVE: If you enjoyed this post, please LIKE and FOLLOW (via email or WordPress Reader) or share with a friend.

Read related posts: What is the Longest Word in English Language?

Word Oddities: Fun with Vowels

What is an Abecedarian Insult?

Difficult Tongue Twisters

Rare Anatomy Words

What Rhymes with Orange?

For further reading: Wordplay: A Curious Dictionary of Language Oddities by Chris Cole, Sterling (1999). rinkworks.com/words/oddities.shtml

listverse.com/2007/12/03/25-english-language-oddities/

http://www.oxforddictionaries.com/us/definition/american_english/aegilops

http://math.cmu.edu/~bkell/alpha-order/

«Alphabetical» and «Alphabetization» redirect here. For other uses, see Alphabetical (disambiguation). For the creation of an alphabetic writing system, which in instances of Latin script is called romanization, see Romanization.

Alphabetical order is a system whereby character strings are placed in order based on the position of the characters in the conventional ordering of an alphabet. It is one of the methods of collation. In mathematics, a lexicographical order is the generalization of the alphabetical order to other data types, such as sequences of numbers or other ordered mathematical objects.

When applied to strings or sequences that may contain digits, numbers or more elaborate types of elements, in addition to alphabetical characters, the alphabetical order is generally called a lexicographical order.

To determine which of two strings of characters comes first when arranging in alphabetical order, their first letters are compared. If they differ, then the string whose first letter comes earlier in the alphabet comes before the other string. If the first letters are the same, then the second letters are compared, and so on. If a position is reached where one string has no more letters to compare while the other does, then the first (shorter) string is deemed to come first in alphabetical order.

Capital or upper case letters are generally considered to be identical to their corresponding lower case letters for the purposes of alphabetical ordering, although conventions may be adopted to handle situations where two strings differ only in capitalization. Various conventions also exist for the handling of strings containing spaces, modified letters, such as those with diacritics, and non-letter characters such as marks of punctuation.

The result of placing a set of words or strings in alphabetical order is that all of the strings beginning with the same letter are grouped together; within that grouping all words beginning with the same two-letter sequence are grouped together; and so on. The system thus tends to maximize the number of common initial letters between adjacent words.

History[edit]

Alphabetical order was first used in the 1st millennium BCE by Northwest Semitic scribes using the abjad system.[1] However, a range of other methods of classifying and ordering material, including geographical, chronological, hierarchical and by category, were preferred over alphabetical order for centuries.[2]

The Bible is dated to the 6th–7th centuries BCE. In the Book of Jeremiah, the prophet utilizes the Atbash substitution cipher, based on alphabetical order. Similarly, biblical authors used acrostics based on the (ordered) Hebrew alphabet.[3]

The first effective use of alphabetical order as a cataloging device among scholars may have been in ancient Alexandria,[4] in the Great Library of Alexandria, which was founded around 300 BCE. The poet and scholar Callimachus, who worked there, is thought to have created the world’s first library catalog, known as the Pinakes, with scrolls shelved in alphabetical order of the first letter of authors’ names.[2]

In the 1st century BC, Roman writer Varro compiled alphabetic lists of authors and titles.[5] In the 2nd century CE, Sextus Pompeius Festus wrote an encyclopedic epitome of the works of Verrius Flaccus, De verborum significatu, with entries in alphabetic order.[6] In the 3rd century CE, Harpocration wrote a Homeric lexicon alphabetized by all letters.[7] In the 10th century, the author of the Suda used alphabetic order with phonetic variations.

Alphabetical order as an aid to consultation started to enter the mainstream of Western European intellectual life in the second half of the 12th century, when alphabetical tools were developed to help preachers analyse biblical vocabulary. This led to the compilation of alphabetical concordances of the Bible by the Dominican friars in Paris in the 13th century, under Hugh of Saint Cher. Older reference works such as St. Jerome’s Interpretations of Hebrew Names were alphabetized for ease of consultation. The use of alphabetical order was initially resisted by scholars, who expected their students to master their area of study according to its own rational structures; its success was driven by such tools as Robert Kilwardby’s index to the works of St. Augustine, which helped readers access the full original text instead of depending on the compilations of excerpts which had become prominent in 12th century scholasticism. The adoption of alphabetical order was part of the transition from the primacy of memory to that of written works.[8] The idea of ordering information by the order of the alphabet also met resistance from the compilers of encyclopaedias in the 12th and 13th centuries, who were all devout churchmen. They preferred to organise their material theologically – in the order of God’s creation, starting with Deus (meaning God).[2]

In 1604 Robert Cawdrey had to explain in Table Alphabeticall, the first monolingual English dictionary, «Nowe if the word, which thou art desirous to finde, begin with (a) then looke in the beginning of this Table, but if with (v) looke towards the end».[9] Although as late as 1803 Samuel Taylor Coleridge condemned encyclopedias with «an arrangement determined by the accident of initial letters»,[10] many lists are today based on this principle.

Arrangement in alphabetical order can be seen as a force for democratising access to information, as it does not require extensive prior knowledge to find what was needed.[2]

Ordering in the Latin script[edit]

Basic order and examples[edit]

The standard order of the modern ISO basic Latin alphabet is:

- A-B-C-D-E-F-G-H-I-J-K-L-M-N-O-P-Q-R-S-T-U-V-W-X-Y-Z

An example of straightforward alphabetical ordering follows:

- As; Aster; Astrolabe; Astronomy; Astrophysics; At; Ataman; Attack; Baa

Another example:

- Barnacle; Be; Been; Benefit; Bent

The above words are ordered alphabetically. As comes before Aster because they begin with the same two letters and As has no more letters after that whereas Aster does. The next three words come after Aster because their fourth letter (the first one that differs) is r, which comes after e (the fourth letter of Aster) in the alphabet. Those words themselves are ordered based on their sixth letters (l, n and p respectively). Then comes At, which differs from the preceding words in the second letter (t comes after s). Ataman comes after At for the same reason that Aster came after As. Attack follows Ataman based on comparison of their third letters, and Baa comes after all of the others because it has a different first letter.

Treatment of multiword strings[edit]

When some of the strings being ordered consist of more than one word, i.e., they contain spaces or other separators such as hyphens, then two basic approaches may be taken. In the first approach, all strings are ordered initially according to their first word, as in the sequence:

- Oak; Oak Hill; Oak Ridge; Oakley Park; Oakley River

- where all strings beginning with the separate word Oak precede all those beginning Oakley, because Oak precedes Oakley in alphabetical order.

In the second approach, strings are alphabetized as if they had no spaces, giving the sequence:

- Oak; Oak Hill; Oakley Park; Oakley River; Oak Ridge

- where Oak Ridge now comes after the Oakley strings, as it would if it were written «Oakridge».

The second approach is the one usually taken in dictionaries[citation needed], and it is thus often called dictionary order by publishers. The first approach has often been used in book indexes, although each publisher traditionally set its own standards for which approach to use therein; there was no ISO standard for book indexes (ISO 999) before 1975.

Special cases[edit]

Modified letters[edit]

In French, modified letters (such as those with diacritics) are treated the same as the base letter for alphabetical ordering purposes. For example, rôle comes between rock and rose, as if it were written role. However, languages that use such letters systematically generally have their own ordering rules. See § Language-specific conventions below.

Ordering by surname[edit]

In most cultures where family names are written after given names, it is still desired to sort lists of names (as in telephone directories) by family name first. In this case, names need to be reordered to be sorted correctly. For example, Juan Hernandes and Brian O’Leary should be sorted as «Hernandes, Juan» and «O’Leary, Brian» even if they are not written this way. Capturing this rule in a computer collation algorithm is complex, and simple attempts will fail. For example, unless the algorithm has at its disposal an extensive list of family names, there is no way to decide if «Gillian Lucille van der Waal» is «van der Waal, Gillian Lucille», «Waal, Gillian Lucille van der», or even «Lucille van der Waal, Gillian».

Ordering by surname is frequently encountered in academic contexts. Within a single multi-author paper, ordering the authors alphabetically by surname, rather than by other methods such as reverse seniority or subjective degree of contribution to the paper, is seen as a way of «acknowledg[ing] similar contributions» or «avoid[ing] disharmony in collaborating groups».[11] The practice in certain fields of ordering citations in bibliographies by the surnames of their authors has been found to create bias in favour of authors with surnames which appear earlier in the alphabet, while this effect does not appear in fields in which bibliographies are ordered chronologically.[12]

The and other common words[edit]

If a phrase begins with a very common word (such as «the», «a» or «an», called articles in grammar), that word is sometimes ignored or moved to the end of the phrase, but this is not always the case. For example, the book «The Shining» might be treated as «Shining», or «Shining, The» and therefore before the book title «Summer of Sam». However, it may also be treated as simply «The Shining» and after «Summer of Sam». Similarly, «A Wrinkle in Time» might be treated as «Wrinkle in Time», «Wrinkle in Time, A», or «A Wrinkle in Time». All three alphabetization methods are fairly easy to create by algorithm, but many programs rely on simple lexicographic ordering instead.

Mac prefixes[edit]

The prefixes M and Mc in Irish and Scottish surnames are abbreviations for Mac and are sometimes alphabetized as if the spelling is Mac in full. Thus McKinley might be listed before Mackintosh (as it would be if it had been spelled out as «MacKinley»). Since the advent of computer-sorted lists, this type of alphabetization is less frequently encountered, though it is still used in British telephone directories.

St prefix[edit]

The prefix St or St. is an abbreviation of «Saint», and is traditionally alphabetized as if the spelling is Saint in full. Thus in a gazetteer St John’s might be listed before Salem (as if it would be if it had been spelled out as «Saint John’s»). Since the advent of computer-sorted lists, this type of alphabetization is less frequently encountered, though it is still sometimes used.

Ligatures[edit]

Ligatures (two or more letters merged into one symbol) which are not considered distinct letters, such as Æ and Œ in English, are typically collated as if the letters were separate—»æther» and «aether» would be ordered the same relative to all other words. This is true even when the ligature is not purely stylistic, such as in loanwords and brand names.

Special rules may need to be adopted to sort strings which vary only by whether two letters are joined by a ligature.

Treatment of numerals[edit]

When some of the strings contain numerals (or other non-letter characters), various approaches are possible. Sometimes such characters are treated as if they came before or after all the letters of the alphabet. Another method is for numbers to be sorted alphabetically as they would be spelled: for example 1776 would be sorted as if spelled out «seventeen seventy-six», and 24 heures du Mans as if spelled «vingt-quatre…» (French for «twenty-four»). When numerals or other symbols are used as special graphical forms of letters, as 1337 for leet or the movie Seven (which was stylised as Se7en), they may be sorted as if they were those letters. Natural sort order orders strings alphabetically, except that multi-digit numbers are treated as a single character and ordered by the value of the number encoded by the digits.

In the case of monarchs and popes, although their numbers are in Roman numerals and resemble letters, they are normally arranged in numerical order: so, for example, even though V comes after I, the Danish king Christian IX comes after his predecessor Christian VIII.

Language-specific conventions[edit]

Languages which use an extended Latin alphabet generally have their own conventions for treatment of the extra letters. Also in some languages certain digraphs are treated as single letters for collation purposes. For example, the Spanish alphabet treats ñ as a basic letter following n, and formerly treated the digraphs ch and ll as basic letters following c and l, respectively. Now сh and ll are alphabetized as two-letter combinations. The new alphabetization rule was issued by the Royal Spanish Academy in 1994. These digraphs were still formally designated as letters but they are no longer so since 2010. On the other hand, the digraph rr follows rqu as expected (and did so even before the 1994 alphabetization rule), while vowels with acute accents (á, é, í, ó, ú) have always been ordered in parallel with their base letters, as has the letter ü.

In a few cases, such as Arabic and Kiowa, the alphabet has been completely reordered.

Alphabetization rules applied in various languages are listed below.

- In Arabic, there are two main orders of the 28 letter alphabet used today. The standard and most commonly used is the hijā alphabet [ar], which was coined by the early Arab linguist Nasr ibn ‘Asim al-Laythi and features a visual ordering method where for example the letters baa, taa, Θaa ب ت ث are ordered base on shape of baa. The original abjad order, which phonethically resembles that of other Semitic languages as well as Latin, is still in use today, usually limited for ordering lists in a document, analogous to Roman Numerals. When the abjadiyya is used in numbering, a unique abstracted way of writing the letters must be used in order to distinguish those letters from three first letter of the sentence as well as from numbers. For example, the Alef «ا» which looks identical to the Hindi numeral one «١», a small oval loop extends clockwise of the letter’s bottom, followed by a short tail. Although these characters are rarely used digitally, they have been recognized under ASCII as Arabic Mathematical Alphabet, with ranges from 1EE00 TO 1EEFF. [13] There is a less common order, which is ordered phonetically Sawti Alphabet [ar], starting from the deep throat sound haa to the lip most meem. This order was created by Al-faraheedi.

- In Azerbaijani, there are eight additional letters to the standard Latin alphabet. Five of them are vowels: i, ı, ö, ü, ə and three are consonants: ç, ş, ğ. The alphabet is the same as the Turkish, with the same sounds written with the same letters, except for three additional letters: q, x and ə for sounds that do not exist in Turkish. Although all the «Turkish letters» are collated in their «normal» alphabetical order like in Turkish, the three extra letters are collated arbitrarily after letters whose sounds approach theirs. So, q is collated just after k, x (pronounced like a German ch) is collated just after h and ə (pronounced roughly like an English short a) is collated just after e.

- In Breton, there is no «c», «q», «x» but there are the digraphs «ch» and «c’h», which are collated between «b» and «d». For example: « buzhugenn, chug, c’hoar, daeraouenn » (earthworm, juice, sister, teardrop).

- In Czech and Slovak, accented vowels have secondary collating weight – compared to other letters, they are treated as their unaccented forms (in Czech, A-Á, E-É-Ě, I-Í, O-Ó, U-Ú-Ů, Y-Ý, and in Slovak, A-Á-Ä, E-É, I-Í, O-Ó-Ô, U-Ú, Y-Ý), but then they are sorted after the unaccented letters (for example, the correct lexicographic order is baa, baá, báa, báá, bab, báb, bac, bác, bač, báč [in Czech] and baa, baá, baä, báa, báá, báä, bäa, bäá, bää, bab, báb, bäb, bac, bác, bäc, bač, báč, bäč [in Slovak]). Accented consonants have primary collating weight and are collated immediately after their unaccented counterparts, with exception of Ď, Ň and Ť (in Czech) and Ď, Ĺ, Ľ, Ň, Ŕ and Ť (in Slovak), which have again secondary weight. CH is considered to be a separate letter and goes between H and I. In Slovak, DZ and DŽ are also considered separate letters and are positioned between Ď and E.

- In the Danish and Norwegian alphabets, the same extra vowels as in Swedish (see below) are also present but in a different order and with different glyphs (…, X, Y, Z, Æ, Ø, Å). Also, «Aa» collates as an equivalent to «Å». The Danish alphabet has traditionally seen «W» as a variant of «V», but today «W» is considered a separate letter.

- In Dutch the combination IJ (representing IJ) was formerly to be collated as Y (or sometimes as a separate letter: Y < IJ < Z), but is currently mostly collated as 2 letters (II < IJ < IK). Exceptions are phone directories; IJ is always collated as Y here because in many Dutch family names Y is used where modern spelling would require IJ. Note that a word starting with ij that is written with a capital I is also written with a capital J, for example, the town IJmuiden, the river IJssel and the country IJsland (Iceland).

- In Esperanto, consonants with circumflex accents (ĉ, ĝ, ĥ, ĵ, ŝ), as well as ŭ (u with breve), are counted as separate letters and collated separately (c, ĉ, d, e, f, g, ĝ, h, ĥ, i, j, ĵ … s, ŝ, t, u, ŭ, v, z).

- In Estonian õ, ä, ö and ü are considered separate letters and collate after w. Letters š, z and ž appear in loanwords and foreign proper names only and follow the letter s in the Estonian alphabet, which otherwise does not differ from the basic Latin alphabet.

- The Faroese alphabet also has some of the Danish, Norwegian, and Swedish extra letters, namely Æ and Ø. Furthermore, the Faroese alphabet uses the Icelandic eth, which follows the D. Five of the six vowels A, I, O, U and Y can get accents and are after that considered separate letters. The consonants C, Q, X, W and Z are not found. Therefore, the first five letters are A, Á, B, D and Ð, and the last five are V, Y, Ý, Æ, Ø

- In Filipino (Tagalog) and other Philippine languages, the letter Ng is treated as a separate letter. It is pronounced as in sing, ping-pong, etc. By itself, it is pronounced nang, but in general Filipino orthography, it is spelled as if it were two separate letters (n and g). Also, letter derivatives (such as Ñ) immediately follow the base letter. Filipino also is written with diacritics, but their use is very rare (except the tilde).

- The Finnish alphabet and collating rules are the same as those of Swedish.

- For French, the last accent in a given word determines the order.[14] For example, in French, the following four words would be sorted this way: cote < côte < coté < côté.

- In German letters with umlaut (Ä, Ö, Ü) are treated generally just like their non-umlauted versions; ß is always sorted as ss. This makes the alphabetic order Arbeit, Arg, Ärgerlich, Argument, Arm, Assistant, Aßlar, Assoziation. For phone directories and similar lists of names, the umlauts are to be collated like the letter combinations «ae», «oe», «ue» because a number of German surnames appear both with umlaut and in the non-umlauted form with «e» (Müller/Mueller). This makes the alphabetic order Udet, Übelacker, Uell, Ülle, Ueve, Üxküll, Uffenbach.

- The Hungarian vowels have accents, umlauts, and double accents, while consonants are written with single, double (digraphs) or triple (trigraph) characters. In collating, accented vowels are equivalent with their non-accented counterparts and double and triple characters follow their single originals. Hungarian alphabetic order is: A=Á, B, C, Cs, D, Dz, Dzs, E=É, F, G, Gy, H, I=Í, J, K, L, Ly, M, N, Ny, O=Ó, Ö=Ő, P, Q, R, S, Sz, T, Ty, U=Ú, Ü=Ű, V, W, X, Y, Z, Zs. (Before 1984, dz and dzs were not considered single letters for collation, but two letters each, d+z and d+zs instead.) It means that e.g. nádcukor should precede nádcsomó (even though s normally precedes u), since c precedes cs in the collation. Difference in vowel length should only be taken into consideration if the two words are otherwise identical (e.g. egér, éger). Spaces and hyphens within phrases are ignored in collation. Ch also occurs as a digraph in certain words but it is not considered as a grapheme on its own right in terms of collation.

- A particular feature of Hungarian collation is that contracted forms of double di- and trigraphs (such as ggy from gy + gy or ddzs from dzs + dzs) should be collated as if they were written in full (independently of the fact of the contraction and the elements of the di- or trigraphs). For example, kaszinó should precede kassza (even though the fourth character z would normally come after s in the alphabet), because the fourth «character» (grapheme) of the word kassza is considered a second sz (decomposing ssz into sz + sz), which does follow i (in kaszinó).

- In Icelandic, Þ is added, and D is followed by Ð. Each vowel (A, E, I, O, U, Y) is followed by its correspondent with acute: Á, É, Í, Ó, Ú, Ý. There is no Z, so the alphabet ends: … X, Y, Ý, Þ, Æ, Ö.

- Both letters were also used by Anglo-Saxon scribes who also used the Runic letter Wynn to represent /w/.

- Þ (called thorn; lowercase þ) is also a Runic letter.

- Ð (called eth; lowercase ð) is the letter D with an added stroke.

- Kiowa is ordered on phonetic principles, like the Brahmic scripts, rather than on the historical Latin order. Vowels come first, then stop consonants ordered from the front to the back of the mouth, and from negative to positive voice-onset time, then the affricates, fricatives, liquids, and nasals:

-

- A, AU, E, I, O, U, B, F, P, V, D, J, T, TH, G, C, K, Q, CH, X, S, Z, L, Y, W, H, M, N

- In Lithuanian, specifically Lithuanian letters go after their Latin originals. Another change is that Y comes just before J: … G, H, I, Į, Y, J, K…

- In Polish, specifically Polish letters derived from the Latin alphabet are collated after their originals: A, Ą, B, C, Ć, D, E, Ę, …, L, Ł, M, N, Ń, O, Ó, P, …, S, Ś, T, …, Z, Ź, Ż. The digraphs for collation purposes are treated as if they were two separate letters.

- In Portuguese, the collating order is just like in English: A, B, C, D, E, F, G, H, I, J, K, L, M, N, O, P, Q, R, S, T, U, V, W, X, Y, Z. Digraphs and letters with diacritics are not included in the alphabet.

- In Romanian, special characters derived from the Latin alphabet are collated after their originals: A, Ă, Â, …, I, Î, …, S, Ș, T, Ț, …, Z.

- In Serbo-Croatian and other related South Slavic languages, the five accented characters and three conjoined characters are sorted after the originals: …, C, Č, Ć, D, DŽ, Đ, E, …, L, LJ, M, N, NJ, O, …, S, Š, T, …, Z, Ž.

- Spanish treated (until 1994) «CH» and «LL» as single letters, giving an ordering of cinco, credo, chispa and lomo, luz, llama. This is not true any more since in 1994 the RAE adopted the more conventional usage, and now LL is collated between LK and LM, and CH between CG and CI. The six characters with diacritics Á, É, Í, Ó, Ú, Ü are treated as the original letters A, E, I, O, U, for example: radio, ráfaga, rana, rápido, rastrillo. The only Spanish-specific collating question is Ñ (eñe) as a different letter collated after N.

- In the Swedish alphabet, there are three extra vowels placed at its end (…, X, Y, Z, Å, Ä, Ö), similar to the Danish and Norwegian alphabet, but with different glyphs and a different collating order. The letter «W» has been treated as a variant of «V», but in the 13th edition of Svenska Akademiens ordlista (2006) «W» was considered a separate letter.

- In the Turkish alphabet there are 6 additional letters: ç, ğ, ı, ö, ş, and ü (but no q, w, and x). They are collated with ç after c, ğ after g, ı before i, ö after o, ş after s, and ü after u. Originally, when the alphabet was introduced in 1928, ı was collated after i, but the order was changed later so that letters having shapes containing dots, cedilles or other adorning marks always follow the letters with corresponding bare shapes. Note that in Turkish orthography the letter I is the majuscule of dotless ı, whereas İ is the majuscule of dotted i.

- In many Turkic languages (such as Azeri or the Jaꞑalif orthography for Tatar), there used to be the letter Gha (Ƣƣ), which came between G and H. It is now in disuse.

- In Vietnamese, there are 7 additional letters: ă, â, đ, ê, ô, ơ, ư while f, j, w, z are absent, even though they are still in some use (like Internet address, foreign loan language). «f» is replaced by the combination «ph». The same as for «w» is «qu».

- In Volapük ä, ö and ü are counted as separate letters and collated separately (a, ä, b … o, ö, p … u, ü, v) while q and w are absent.[15]

- In Welsh the digraphs CH, DD, FF, NG, LL, PH, RH, and TH are treated as single letters, and each is listed after the first character of the pair (except for NG which is listed after G), producing the order A, B, C, CH, D, DD, E, F, FF, G, NG, H, and so on. It can sometimes happen, however, that word compounding results in the juxtaposition of two letters which do not form a digraph. An example is the word LLONGYFARCH (composed from LLON + GYFARCH). This results in such an ordering as, for example, LAWR, LWCUS, LLONG, LLOM, LLONGYFARCH (NG is a digraph in LLONG, but not in LLONGYFARCH). The letter combination R+H (as distinct from the digraph RH) may similarly arise by juxtaposition in compounds, although this tends not to produce any pairs in which misidentification could affect the ordering. For the other potentially confusing letter combinations that may occur – namely, D+D and L+L – a hyphen is used in the spelling (e.g. AD-DAL, CHWIL-LYS).

Automation[edit]

Collation algorithms (in combination with sorting algorithms) are used in computer programming to place strings in alphabetical order. A standard example is the Unicode Collation Algorithm, which can be used to put strings containing any Unicode symbols into (an extension of) alphabetical order.[14] It can be made to conform to most of the language-specific conventions described above by tailoring its default collation table. Several such tailorings are collected in Common Locale Data Repository.

Similar orderings[edit]

The principle behind alphabetical ordering can still be applied in languages that do not strictly speaking use an alphabet – for example, they may be written using a syllabary or abugida – provided the symbols used have an established ordering.

For logographic writing systems, such as Chinese hanzi or Japanese kanji, the method of radical-and-stroke sorting is frequently used as a way of defining an ordering on the symbols. Japanese sometimes uses pronunciation order, most commonly with the Gojūon order but sometimes with the older Iroha ordering.

In mathematics, lexicographical order is a means of ordering sequences in a manner analogous to that used to produce alphabetical order.[16]

Some computer applications use a version of alphabetical order that can be achieved using a very simple algorithm, based purely on the ASCII or Unicode codes for characters. This may have non-standard effects such as placing all capital letters before lower-case ones. See ASCIIbetical order.

A rhyming dictionary is based on sorting words in alphabetical order starting from the last to the first letter of the word.

See also[edit]

- Collation

- Sorting

References[edit]

- ^ Reinhard G. Lehmann: «27-30-22-26. How Many Letters Needs an Alphabet? The Case of Semitic», in: The idea of writing: Writing across borders, edited by Alex de Voogt and Joachim Friedrich Quack, Leiden: Brill 2012, pp. 11–52.

- ^ a b c d Street, Julie (10 June 2020). «From A to Z — the surprising history of alphabetical order» (text and audio). ABC News (ABC Radio National). Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 6 July 2020.

- ^ e.g. Psalms 25, 34, 37, 111, 112, 119 and 145 of the Hebrew Bible

- ^ Daly, Lloyd. Contributions to the History of Alphabetization in Antiquity and the Middle Ages. Brussels, 1967. p. 25.

- ^ O’Hara, James (1989). «Messapus, Cycnus, and the Alphabetical Order of Vergil’s Catalogue of Italian Heroes». Phoenix. 43 (1): 35–38. doi:10.2307/1088539. JSTOR 1088539.

- ^ LIVRE XI – texte latin – traduction + commentaires.

- ^ Gibson, Craig (2002). Interpreting a classic: Demosthenes and his ancient commentators.

- ^ Rouse, Mary A.; Rouse, Richard M. (1991), «Statim invenire: Schools, Preachers and New Attitudes to the Page», Authentic Witnesses: Approaches to Medieval Texts and Manuscripts, University of Notre Dame Press, pp. 201–219, ISBN 0-268-00622-9

- ^ Cawdrey, Robert (1604). A Table Alphabeticall. London. p. [A4]v.

- ^ Coleridge’s Letters, No.507.

- ^ Tscharntke, Teja; Hochberg, Michael E; Rand, Tatyana A; Resh, Vincent H; Krauss, Jochen (January 2007). «Author Sequence and Credit for Contributions in Multiauthored Publications». PLOS Biol. 5 (1): e18. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0050018. PMC 1769438. PMID 17227141.

- ^ Stevens, Jeffrey R.; Duque, Juan F. (2018). «Order Matters: Alphabetizing In-Text Citations Biases Citation Rates» (PDF). Psychonomic Bulletin & Review. 26 (3): 1020–1026. doi:10.3758/s13423-018-1532-8. PMID 30288671. S2CID 52922399.

- Lay summary in: Colleen Flaherty (22 October 2018). «The Case Against Alphabetical Naming of Authors». Inside Higher Ed.

- ^ «Arabic Mathematical Alphabetic Symbols» (PDF). THE Unicode Standard.

- ^ a b «Unicode Technical Standard #10: Unicode collation algorithm». Unicode, Inc. (unicode.org). 20 March 2008. Retrieved 27 August 2008.

- ^ Midgley, Ralph. «Volapük to English dictionary» (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 September 2012. Retrieved 24 September 2019.

- ^ Franz Baader; Tobias Nipkow (1999). Term Rewriting and All That. Cambridge University Press. pp. 18–19. ISBN 978-0-521-77920-3.

Further reading[edit]

- Chauvin, Yvonne. Pratique du classement alphabétique. 4th ed. Paris: Bordas, 1977. ISBN 2-04-010155-1

- Flanders, Judith. A Place for Everything: The Curious History of Alphabetical Order. New York: Basic Books / Hatchette Books, 2020. ISBN 978-1-5416-7507-0

I’m going to go over some general rules for alphabetizing in case you need to manually put a bunch of words in alphabetical order. These are just general rules, some academic and news organizations may follow specific alphabetization styles that deviate from these rules so keep that in mind depending on your circumstances.

The Rules of Alphabetical Order

Aside from knowing the basic ABC order of the alphabet, I’m going to talk about a few of the important rules you need to know. In this general overview, I’m going to try to talk about all the little minefields you might typically encounter when trying to figure out how to alphabetize words into a group of items or lines.

If you’re in a hurry, I have a very short summary of the rules of alphabetical order that should answer a lot of your questions about the basic rules of alphabetizing.

PS. If you’re looking for a quick method to alphabetize a list of words or lines of text online then check out my free tool for alphabetizing text. It works with all kinds of text formats.

How to Alphabetize Words with Capitals

The primary rule in standard dictionary order is that capital letters come before lowercase letters. Let’s go over some examples to make this clearer.

If there are two identical words and one of them is capitalized then the capitalized word goes first in the alphabetical order like so:

- Apple, apple

As we can see from the example above the company (Apple) comes before the fruit (apple) in any alphabetical list.

Now, what if we had another company with a shorter name like App for example. This shorter name is identical to the start of the other company’s name. In this case, the shorter word would take precedence and come first. So our word list would now look like this:

- App, Apple, apple

Let’s imagine that we added another company whose name was in all caps like AP. This company would place first on the list because it’s capitalized and shorter than the rest of the items. Our list now looks like this.

- AP, App, Apple, apple

Ok, let’s add one more word to the madness here. What if we wanted to add the word «app» to this list — as in an app on your phone. Where would it go?

It’s not in uppercase at all and so it must go after the near duplicate «App» and it’s shorter than the next word «Apple» so it must go before that word, consequently, our list now looks like this:

- AP, App, app, Apple, apple

Let’s add yet one more similar capitalized item to our increasingly complicated little list and find out where it should be sorted.

Imagine a company that has periods in its name like «A.P.» for example. Where would an item like that be placed in our alphabetically organized list?

In this case, in weighting «A.P.» vs «AP», we comclude that «A.P.» will come first as the period in the second character spot will take precedence over any A-Z letter. So our ever-growing example for capital words in alphabetical order now looks like this:

- A.P., AP, App, app, Apple, apple

I would treat periods as generally taking precedence over all the letters but another perfectly valid school of thought for alphabetizing word lists like this is to ignore the periods and alphabetize the list as if they were not there.

In summary, the key rule to remember is that capitals have extra weight and will come first in alphabetically competing situations and that shorter is also a factor here specifically — and in general circumstances when organizing things in alphabetical order.

Deal with punctuation by either ignoring them when ranking or ranking the punctuation marks as higher in the sort order than the other letters — give them a similar ranking to a blank space. This is the approach I usually take.

How to Alphabetize People’s Names

Names are alphabetized according to some of the standard lexical rules that we’ve talked about.

But three situations occur in people’s names that deserve specific consideration.

These situations relate to the roles of the apostrophe, abbreviations, and accented characters in capitalizing the names of people.

- How to alphabetize a name with an apostrophe.

There are two schools of thought here. The more common one seems to be in indexing the word as if the apostrophe was not there. Therefore «OBrian» would rank exactly the same as O’Brian. You might find this way used in phone books or similar.Another option would be to regard the apostrophe as ranking before the letters like a blank space and so «O’Brian» would come before «OBrian»… if such a name existed.

- Alphabetizing a name containing an abbreviation.

The situation for the period is similar to a blank space if sorting on a letter-by-letter basis. But here’s an interesting example containing an abbreviation and a period to consider.Let’s pretend we have two names in our database of customers and we want to put them in alphabetical order. The names are Bob Saint Lawrence and Bob St. James.

If we go letter-by-letter then Bob Saint Lawrence will come first. There are however some systems in which abbreviated names are alphabetized as if they were not abbreviated. And so Bob St. James would be sorted as if it was Bob Saint James. Using a system rule like this, the order of your name list would now be «Bob St. James, Bob Saint Lawrence».

I’m not recommending this treatment of abbreviations for most everyday uses but in some very specific formalized systems this kind of word-by-word sorting may be necessary especially if you have to conform data as much as possible in a business system.

- Alphabetical order for names with accents in them.

The most common approach is to put the list in alphabetical order as if the accent didn’t exist so É would weigh the same as E in the sort order. In cases of identical items like Élise and Elise then typically the word without the accent would be listed first in the alphabetical order as in this example «Elise, Élise». Languages other than English have very specific and different rules for accented letters which aren’t covered in this article.

Alphabetizing Hyphenated Words

In general, you should mostly treat the hyphen as if it were a blank space. For example «clean-shaven» would be sorted as if the hyphen were a blank space as in «clean shaven». Given two identical items where one has a hyphen then the hyphenated word should go in the second spot as in this example — «clean shaven, clean-shaven.» The hyphen is given less sorting weight in this instance.

Alphabetizing Names with Hyphens

In terms of alphabetizing people’s names with hyphens, a good example would be this already alphabetically sorted list «Mary Ann, Mary-Ann, Maryellen».

The hyphen is generally treated as a space with less sort weight than a real space but more weight than a single letter and so the name «Mary-Ann» falls into the middle of our example alphabetized list.

Some people use a style where the hyphen is considered removed before sorting so that «Mary-Ann» is sorted as if it was «MaryAnn» but we don’t talk to those people so don’t worry about it.

Alphabetical Sorting for Words and Numbers

Let’s just consider numbers and how they can be alphabetically sorted before mixing words into the picture.

Consider these three numbers, «3,4,5». What happens when we add the number «04» to the list? Where will it be alphabetically placed in the order? This is the result:

- 04,3,4,5

These surprising results occur because we are not doing numerical sorting. Numerical sorting involves listing numbers by their value in ascending or descending order. Here we’re sorting them alphabetically not numerically so the expected results are different. Each number is evaluated on a letter by letter basis.

So when looking at the first character of each string we find that 0 is the lowest of the number characters and so that number will be placed first in the list. The value of the number is not assessed as a whole numerical value. It is evaluated in the sorting order on a digit-by-digit basis.

Numbers will come before letters when alphabetizing lists so any item starting with a number will take precedence as demonstrated by this list.

- 24 hours, twenty 4 hours, twenty four hours

The easy rule of thumb here is to remember that when alphabetizing a mix of letters and numbers is that the numbers take precedence in the sorting order and they are not sorted according to their overall numerical value most of the time.

Hybrid Sorting Systems

Sorting numbers in a non-numerical fashion can be non-optimal depending on the circumstances. For something like sorting items in a bibliography non-numerical sorting isn’t a deal-breaker but in other places, it’s a non-ideal way to deal with number sorting.

For things like a list of files, a hybrid mix of alphabetical and numerical sorting might make more sense from a usability perspective. A system like this might want to list files in a way that would make sense at a glance to the average user.

Below is a screenshot from the Windows operating system where file names are sorted alphabetically but when it comes to files with numbered names, the computer employs a numerical sort making sure that «3» comes before «04» in the list of files.

Alphabetical Order Summary List

Here’s a quick summary of some of the basic rules you need to know to alphabetize in English.

- Capital letters come before lowercase letters

- Numbers come before letters

- Numbers are generally sorted on a digit-by-digit basis

- A blank space will take precedence over a letter in the sort order

- Punctuation like the hyphen should be treated similarly to a blank space

I hope you enjoyed this breezy lexical rundown on the ins and outs of how to alphabetize. I tried to make it as entertaining and informative as I could.

If you notice any important fact dealing with alphabetical order that you think should be included, feel free to contact me with the info.

Most Popular Text Tools

Alphabetical Tools

Random Generators

Line Break Tools

Fun Text Tools

Text Changing Tools

SEO and Word Tools

Content Conversion Tools

HTML Code Generators

HTML Compression

HTML Encoding Tools

A list of 53 words by ringman.

- mossywas added by ringman and appears on 29 lists

- lossywas added by ringman and appears on 14 lists

- knottywas added by ringman and appears on 40 lists

- hippywas added by ringman and appears on 16 lists

- hippowas added by ringman and appears on 19 lists

- hillywas added by ringman and appears on 10 lists

- glossywas added by ringman and appears on 43 lists

- gimpywas added by ringman and appears on 10 lists

- glorywas added by ringman and appears on 68 lists

- ghostwas added by ringman and appears on 101 lists

- fortywas added by ringman and appears on 29 lists

- floppywas added by ringman and appears on 25 lists

- floorwas added by ringman and appears on 30 lists

- firstwas added by ringman and appears on 60 lists

- fillywas added by ringman and appears on 31 lists

- emptywas added by ringman and appears on 52 lists

- effortwas added by ringman and appears on 33 lists

- deitywas added by ringman and appears on 56 lists

- choppywas added by ringman and appears on 21 lists

- choosywas added by ringman and appears on 10 lists

- chillywas added by ringman and appears on 37 lists

- bootywas added by ringman and appears on 41 lists

- boostwas added by ringman and appears on 34 lists

- boostwas added by ringman and appears on 34 lists

- bloopwas added by ringman and appears on 27 lists

- biopsywas added by ringman and appears on 13 lists

- billywas added by ringman and appears on 24 lists

- berrywas added by ringman and appears on 42 lists

- billowwas added by ringman and appears on 61 lists

- belowwas added by ringman and appears on 24 lists

- bellywas added by ringman and appears on 71 lists

- bellowwas added by ringman and appears on 49 lists

- beginwas added by ringman and appears on 30 lists

- befitwas added by ringman and appears on 8 lists

- beefywas added by ringman and appears on 25 lists

- annoywas added by ringman and appears on 15 lists

- amortwas added by ringman and appears on 17 lists

- almostwas added by ringman and appears on 30 lists

- alloywas added by ringman and appears on 64 lists

- allowwas added by ringman and appears on 36 lists

- allotwas added by ringman and appears on 27 lists

- afootwas added by ringman and appears on 27 lists

- affixwas added by ringman and appears on 36 lists

- aegiswas added by ringman and appears on 156 lists

- adoptwas added by ringman and appears on 29 lists

- adeptwas added by ringman and appears on 98 lists

- accostwas added by ringman and appears on 88 lists

- accesswas added by ringman and appears on 50 lists

- acceptwas added by ringman and appears on 35 lists

- accentwas added by ringman and appears on 48 lists

- abortwas added by ringman and appears on 23 lists

- abbotwas added by ringman and appears on 30 lists

- abbeywas added by ringman and appears on 34 lists

-

Система упорядочивания слов, имен и фраз

Алфавитный порядок — это система, в которой символьные строки размещаются по порядку, основанному на позиции символов в обычном порядке алфавита. Это один из методов сопоставления. В математике лексикографический порядок — это обобщение алфавитного порядка на другие типы данных, такие как последовательности цифр или чисел.

При применении к строкам или последовательностям, которые, помимо буквенных символов, могут содержать также цифры, числа или более сложные типы элементов, алфавитный порядок обычно называется лексикографическим порядком.

Чтобы определить, какая из двух строк символов идет первой при расположении в алфавитном порядке, сравниваются их первые буквы. Если они различаются, то строка, первая буква которой идет раньше в алфавите, идет раньше другой строки. Если первые буквы совпадают, то сравниваются вторые буквы и так далее. Если достигается позиция, в которой в одной строке больше нет букв для сравнения, а в другой — нет, то считается, что первая (более короткая) строка идет первой в алфавитном порядке.

Заглавные буквы (верхний регистр) обычно считаются идентичными соответствующим строчным буквам для целей алфавитного упорядочивания, хотя могут быть приняты соглашения для обработки ситуаций, когда две строки отличаются только заглавными буквами. Также существуют различные соглашения для обработки строк, содержащих пробелы, модифицированные буквы (например, с диакритическими знаками ) и небуквенные символы, такие как знаки пунктуации.

В результате размещения набора слов или строк в алфавитном порядке все строки, начинающиеся с одной и той же буквы, группируются вместе; и внутри этой группы все слова, начинающиеся с одной и той же двухбуквенной последовательности, сгруппированы вместе; и так далее. Таким образом, система стремится максимизировать количество общих начальных букв между соседними словами.

Содержание

- 1 История

- 2 Упорядочивание латинскими буквами

- 2.1 Основной порядок и пример

- 2.2 Обработка многословных строк

- 2.3 Особые случаи

- 2.3.1 Измененные буквы

- 2.3.2 Упорядочивание по фамилии

- 2.3.3 И другие общеупотребительные слова

- 2.3.4 Префиксы Mac

- 2.3.5 Лигатуры

- 2.4 Обработка цифр

- 2.5 Соглашения, связанные с языком

- 3 Автоматизация

- 4 Подобные порядки

- 5 См. Также

- 6 Ссылки

- 7 Дополнительная литература

- 8 Внешние ссылки

История

Алфавитный порядок был впервые использован в 1-м тысячелетие до н.э. писцами Северо-Запада, использующими систему Абджад. Однако ряд других методов классификации и упорядочивания материалов, включая географический, хронологический, иерархический и по категориям, на протяжении веков предпочитался алфавитному порядку. 124>

Библия датируется VI – VII веками до нашей эры. В Книге Иеремии пророк использует замещающий шифр Atbash, основанный на алфавитном порядке. Точно так же библейские авторы использовали акростих на основе (упорядоченного) еврейского алфавита.

. Первое эффективное использование алфавитного порядка в качестве инструмента каталогизации среди ученых, возможно, было в древней Александрии, в Великая Александрийская библиотека, основанная около 300 г. до н. Э. Считается, что поэт и ученый Каллимах, который там работал, создал первый в мире библиотечный каталог, известный как Pinakes, со свитками, расположенными на полках в алфавитном порядке. первой буквы имен авторов.

В I веке до нашей эры римский писатель Варрон составил алфавитные списки авторов и названий. Во II веке н. Э. Секст Помпей Фест написал энциклопедический краткий труд Верриуса Флакка, De verborum Signy с записями в алфавитном порядке. В III веке н. Э. Гарпократ написал гомеровский лексикон, алфавитный по всем буквам. В X веке автор Суда использовал алфавитный порядок с фонетическими вариациями.

Алфавитный порядок для помощи в консультациях начал входить в основное русло западноевропейской интеллектуальной жизни во второй половине XII века, когда были разработаны алфавитные инструменты для помощи проповедникам проанализировать библейскую лексику. Это привело к составлению алфавитных соответствий Библии доминиканскими монахами в Париже в 13 веке, при Гуго Сен-Шер. Старые справочные работы, такие как St. Толкования еврейских имен Иеронимом были упорядочены по алфавиту для облегчения консультации. Ученые изначально сопротивлялись использованию алфавитного порядка, ожидая, что их ученики овладеют своей областью обучения в соответствии с его собственными рациональными структурами; его успех был обусловлен такими инструментами, как указатель Роберта Килвардби к трудам St. Августина, что помогло читателям получить доступ к полному оригинальному тексту вместо того, чтобы полагаться на компиляции отрывков, которые стали заметными в схоластике 12 века. Принятие алфавитного порядка было частью перехода от первенства памяти к первенству письменных произведений. Идея упорядочения информации по алфавиту также встретила сопротивление составителей энциклопедий в XII и XIII веках, которые все были набожными церковниками. Они предпочли организовать свой материал теологически — в порядке творения Бога, начиная с Деуса (то есть Бога).

В 1604 году Роберт Кэудри должен был объяснить в Table Alphabeticall, первый одноязычный английский словарь, «Теперь, если слово, которое вы хотите найти, начинается с (a), то посмотрите в начале эту таблицу, но если с (v) посмотрите в конец ». Хотя еще в 1803 году Сэмюэл Тейлор Кольридж осуждал энциклопедии за «расположение, обусловленное случайностью начальных букв», сегодня многие списки основаны на этом принципе.

Упорядочение в алфавитном порядке можно рассматривать как фактор демократизации доступа к информации, так как не требуется обширных предварительных знаний, чтобы найти то, что было необходимо.

Упорядочивание латинским шрифтом

Основной порядок и пример

Стандартный порядок современного основного латинского алфавита ISO :

- ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTU-VWXYZ

Ниже приведен пример прямого алфавитного упорядочения:

- Как; Астра; Астролябия; Астрономия; Астрофизика; В; Атаман; Атака; Baa

Другой пример:

- Barnacle; Быть; Был; Выгода; Bent

Вышеупомянутые слова расположены в алфавитном порядке. Как идет до Астера, потому что они начинаются с тех же двух букв, а у А больше нет букв после этого, в то время как Астер делает. Следующие три слова идут после астры, потому что их четвертая буква (первая, которая отличается) — это r, которая идет после е (четвертая буква астры) в алфавите. Сами слова упорядочены по их шестым буквам (l, n и p соответственно). Затем идет Ат, который отличается от предыдущих слов второй буквой (t идет после s). Атаман идет после Ат по той же причине, по которой Астер пришел после Ас. Атака следует за атаманом на основе сравнения их третьих букв, а Баа следует за всеми остальными, потому что у него другая первая буква.

Обработка многословных строк

Когда некоторые из упорядочиваемых строк состоят из более чем одного слова, т. Е. Содержат пробелы или другие разделители, такие как дефисы, тогда можно использовать два основных подхода. В первом подходе все строки сначала упорядочиваются в соответствии с их первым словом, как в последовательности:

- Дуб; Дубовый холм; Oak Ridge; Окли Парк; Oakley River

- , где все строки, начинающиеся с отдельного слова Oak, предшествуют всем строкам, начинающимся с Oakley, потому что Oak предшествует Oakley в алфавитном порядке.

Во втором подходе строки располагаются в алфавитном порядке, как если бы в них не было пробелов, что дает последовательность:

- Дуб; Дубовый холм; Окли Парк; Река Окли; Oak Ridge

- где Oak Ridge теперь следует после строк Oakley, как если бы он был написан «Oakridge».

Второй подход обычно используется в словарях, и поэтому его часто называют заказ словаря от издателей. Первый подход часто использовался в книжных указателях, хотя каждый издатель традиционно устанавливал свои собственные стандарты для того, какой подход использовать в них; до 1975 г. не существовало стандарта ISO для указателей книг (ISO 999 ).

Особые случаи

Измененные буквы

Во французском языке измененные буквы (например, так как буквы с диакритическими знаками ) обрабатываются так же, как базовая буква для целей алфавитного порядка. Например, между роком и розой идет роль, как если бы это была написанная роль. Однако языки, которые используют такие буквы систематически, обычно имеют свои собственные правила упорядочивания. См. Соглашения для конкретных языков ниже.

Сортировка по фамилии

В большинстве культур, где фамилии пишутся после заданных имен, по-прежнему желательно сортировать списки имен (как в телефонных справочниках) сначала по фамилии. В этом случае необходимо изменить порядок имен для правильной сортировки. Например, Хуана Эрнандеса и Брайана О’Лири следует отсортировать как «Эрнандес, Хуан» и «О’Лири, Брайан», даже если они написаны иначе. Уловить это правило в компьютерном алгоритме сопоставления сложно, и простые попытки обязательно потерпят неудачу. Например, если в распоряжении алгоритма нет обширного списка фамилий, невозможно определить, является ли «Джиллиан Люсиль ван дер Ваал» «Ван дер Ваал, Джиллиан Люсиль», «Ваал, Джиллиан Люсиль ван дер», или даже «Люсиль ван дер Ваал, Джиллиан».

Упорядочивание по фамилии часто встречается в академическом контексте. В рамках одной статьи с несколькими авторами упорядочивание авторов в алфавитном порядке по фамилии, а не с помощью других методов, таких как обратный стаж или субъективная степень вклада в статью, рассматривается как способ «признательности за аналогичный вклад» или «избежать [ing] дисгармония в сотрудничающих группах ». Было обнаружено, что практика в некоторых областях упорядочивания цитат в библиографиях по фамилиям их авторов создает предвзятость в пользу авторов с фамилиями, которые появляются в начале алфавита, в то время как этот эффект не проявляется в полях в какие библиографии упорядочены в хронологическом порядке.

И другие общеупотребительные слова

Если фраза начинается с очень распространенного слова (например, «the», «a» или «an» в грамматике, называемых статьями), это слово иногда игнорируется или перемещается в конец фразы, но это не всегда так. Например, книга «Сияние » может рассматриваться как «Сияние» или «Сияние, Сияние» и, следовательно, перед названием книги «Лето Сэма », хотя может также можно трактовать просто как «Сияние» и после «Лето Сэма». Аналогично, «Морщинка во времени » может рассматриваться как «Морщинка во времени», «Морщинка во времени, A» или «Морщинка во времени». Все три метода алфавита довольно легко создать с помощью алгоритма, но многие программы вместо этого полагаются на простой лексикографический порядок. Статьи обычно игнорируются при расположении по алфавиту.

Префиксы Mac

Префиксы M ‘и Mc в ирландских и шотландских фамилиях являются аббревиатурами для Mac и иногда располагаются в алфавитном порядке, как будто написано Mac полностью. Таким образом, Мак-Кинли мог быть указан перед Макинтошем (как если бы он был написан как «Мак-Кинли»). С появлением компьютерно-сортированных списков этот тип алфавита встречается реже, хотя он все еще используется в британских телефонных справочниках.

Лигатуры

Лигатуры (две или более буквы, объединенные в один символ), которые не считаются отдельными буквами, например Æ и Œ на английском языке, обычно сопоставляются так, как если бы буквы были отдельными — «эфир» и «эфир» были бы упорядочены одинаково по отношению ко всем другим словам. Это верно даже в том случае, если лигатура не является чисто стилистической, например, в заимствованных словах и фирменных наименованиях.

Может потребоваться принятие специальных правил для сортировки строк, которые различаются только тем, соединены ли две буквы лигатурой.

Обработка цифр

Когда некоторые из строк содержат цифры (или другие небуквенные символы), возможны различные подходы. Иногда такие символы обрабатываются так, как если бы они стояли до или после всех букв алфавита. Другой метод заключается в сортировке чисел в алфавитном порядке, как если бы они были написаны: например, 1776 будет отсортировано, как если бы было написано «семнадцать семьдесят шесть», а 24 heures du Mans как если написано «vingt-quatre…» (по-французски «двадцать четыре»). Когда цифры или другие символы используются в качестве специальных графических форм букв, например, 1337 для leet или фильма Seven (который был стилизован под Se7en), они могут быть отсортированы, как если бы они были эти буквы. Естественный порядок сортировки упорядочивает строки в алфавитном порядке, за исключением того, что многозначные числа обрабатываются как один символ и упорядочиваются по значению числа, закодированного цифрами.

Соглашения, специфичные для языка

Языки, в которых используется расширенный латинский алфавит, обычно имеют свои собственные соглашения для обработки дополнительных букв. Также в некоторых языках определенные орграфы обрабатываются как отдельные буквы для целей сопоставления. Например, 29-буквенный алфавит испанского рассматривает ñ как базовую букву, следующую за n, и ранее рассматривал орграфы ch и ll как базовые буквы, следующие за c и l, соответственно. Ch и ll по-прежнему считаются буквами, но теперь они расположены по алфавиту как двухбуквенные комбинации. (Новое правило алфавитизации было выпущено Королевской испанской академией в 1994 году.) С другой стороны, орграф rr следует за rqu, как и ожидалось, и сделал это даже до правила алфавита 1994 года.

В некоторых случаях, например, Kiowa, алфавит был полностью переупорядочен.

Правила алфавита, применяемые к различным языкам, перечислены ниже.

- В азербайджанском есть восемь дополнительных букв к стандартному латинскому алфавиту. Пять из них — гласные: i, ı, ö, ü, ə и три — согласные: ç, ş, ğ. Алфавит такой же, как турецкий алфавит, с теми же звуками, записанными теми же буквами, за исключением трех дополнительных букв: q, x и ə для звуков, которых нет в турецком языке. Хотя все «турецкие буквы» упорядочены в их «нормальном» алфавитном порядке, как в турецком, три дополнительных буквы сопоставляются произвольно после букв, звуки которых близки к их. Итак, q сравнивается сразу после k, x (произносится как немецкое ch) сравнивается сразу после h, а ə (произносится примерно как английское сокращение a) сравнивается сразу после e.

- В бретонском, нет «c», «q», «x», но есть орграфы «ch» и «c’h», которые сравниваются между «b» и «d». Например: «buzhugenn, chug, c’hoar, daeraouenn» (дождевой червь, сок, сестра, слеза).

- на боснийском, хорватском и Сербский и другие родственные южнославянские языки, пять акцентированных знаков и три соединенных символа отсортированы после оригиналов:…, C, Č, Ć, D, DŽ, Đ, E,…, L, LJ, M, N, NJ, O,…, S, Š, T,…, Z, Ž.

- на чешском и словацком, Гласные с ударением имеют вторичный вес при сопоставлении — по сравнению с другими буквами, они рассматриваются как их формы без ударения (A-Á, E-É-Ě, I-Í, O-Ó-Ô, U-Ú-Ů, Y-Ý), но затем они сортируются после букв без ударения (например, правильный лексикографический порядок: baa, baá, báa, bab, báb, bac, bác, bač, báč). Согласные с ударением (те, что с caron ) имеют первичный упорядочивающий вес и размещаются сразу после их безударных аналогов, за исключением Ď, Ň и Ť, которые снова имеют вторичный вес. CH считается отдельной буквой и находится между H и I. На словацком языке DZ и DŽ также считаются отдельными буквами и располагаются между Ď и E (A-Á-Ä-BC -Č-D-Ď-DZ-DŽ-E-É…).

- В датском и норвежском алфавитах те же дополнительные гласные, что и в шведском (см. Ниже) также присутствует, но в другом порядке и с разными символами (…, X, Y, Z, Æ, Ø, Å ). Кроме того, «Aa» сравнивается как эквивалент «Å». В датском алфавите «W» традиционно рассматривается как вариант «V», но сегодня «W» считается отдельной буквой.

- В голландском комбинация IJ (представляющая IJ ) раньше было сопоставлено как Y (или иногда как отдельная буква Y < IJ < Z), but is currently mostly collated as 2 letters (II < IJ < IK). Exceptions are phone directories; IJ is always collated as Y here because in many Dutch family names Y is used where modern spelling would require IJ. Note that a word starting with ij that is written with a capital I is also written with a capital J, for example, the town IJmuiden, река IJssel и страна IJsland (Исландия ).

- В эсперанто согласные с циркумфлексом акценты (ĉ, ĝ, ĥ, ĵ, ŝ ), а также ŭ (u с breve ) считаются отдельными буквами и сопоставляются отдельно (c, ĉ, d, e, f, g, ĝ, h, ĥ, i, j, ĵ… s, ŝ, t, u, ŭ, v, z).

- In Эстонский õ, ä, ö и ü считаются отдельными буквами и сопоставляются после w. Буквы š, z и ž появляются только в заимствованных словах и иностранных именах собственных и следовать за буквой s в эстонском алфавите, который в остальном не отличается от основного латинского алфавита.

- Фарерский алфавит также имеет некоторые дополнительные буквы датского, норвежского и шведского языков, а именно Æ и Ø. Кроме того, фарерский алфавит использует исландский eth, который следует за D. Пять из шести гласных A, I, O, U и Y могут иметь ударения и после этого считаются отдельными буквами. Согласные C, Q, X, W и Z не найдены. Таким образом, первые пять букв — это A, Á, B, D и Ð, а последние пять — V, Y, Ý, Æ, Ø

- . В филиппинском (тагальском) и других филиппинских языках буква Ng рассматривается как отдельное письмо. Оно произносится как пинг, пинг-понг и т. Д. Само по себе оно произносится как нанг, но в целом филиппинская орфография пишется так, как если бы это были две отдельные буквы ( п и ж). Кроме того, производные от букв (например, Ñ ) сразу же следуют за базовой буквой. Филиппинский также пишется с диакритическими знаками, но они используются очень редко (кроме тильды ). (Филиппинская орфография также включает орфографию.)

- Финский алфавит и правила сопоставления такие же, как и для шведского.

- Для французского последний акцент в данном слове определяет порядок. Например, во французском языке следующие четыре слова будут отсортированы таким образом: cote < côte < coté < côté.

- В немецком буквы с умлаутом (Ä, Ö, Ü ) обычно обрабатываются так же, как и их версии без умлаута; ß всегда сортируется как ss. Это составляет алфавитный порядок Ärgerlich, Arg, Arm, Assistant, Aßlar, Assoziation. Для телефонных справочников и аналогичных списков имен умлауты должны быть сопоставлены как буквенные комбинации «ae», «oe», «ue», потому что ряд немецких фамилий появляется как с умлаутом, так и в неавторизованной форме с «e». «(Мюллер / Мюллер). Таким образом, в алфавитном порядке Udet, Übelacker, Uell, Ülle, Ueve, Üxküll, Uffenbach.

- венгерские гласные имеют ударение, умляуты и двойные ударения, а согласные пишутся с одинарными, двойные (орграфы) или тройные (триграф) символы. При сопоставлении гласные с акцентом эквивалентны своим аналогам без ударения, а двойные и тройные символы следуют за их одиночными оригиналами. Венгерский алфавитный порядок: A = Á, B, C, Cs, D, Dz, Dzs, E = É, F, G., Gy, H, I = Í, J, K, L, Ly, M, N, Ny, O = Ó, Ö = Ő, P, Q, R, S, Sz, T, Ty, U = Ú, Ü = Ű, V, W, X, Y, Z, Zs . (До 1984 года dz и dzs не считались отдельными буквами для сопоставления, но вместо этого считались двумя буквами, d + z и d + zs.) Это означает, что, например, nádcukor должен предшествовать nádcsomó (даже если s обычно предшествует u), поскольку c предшествует cs в сопоставлении. Разницу в длине гласных следует учитывать только в том случае, если два слова идентичны в остальном (например, egér, éger). Пробелы и дефисы внутри фраз при сопоставлении игнорируются. Ch также встречается в некоторых словах как орграф, но не рассматривается как графема сама по себе с точки зрения сопоставления.

- Особенностью венгерского сопоставления является то, что сжатые формы двойных ди- и триграфов (например, ggy от gy + gy или ddzs от dzs + dzs) должны быть сопоставлены, как если бы они были написаны полностью (независимо от факт сокращения и элементы ди- или триграфов). Например, kaszinó должно предшествовать kassza (даже если четвертый символ z обычно идет после s в алфавите), потому что четвертый «символ» (графема ) слова kassza считается вторым sz (разложение ssz в sz + sz), который следует за i (в kaszinó).

- В исландский добавляется, Þ, а за D следует Ð. За каждой гласной (A, E, I, O, U, Y) следует соответствующий ей с акутом : Á, É, Í, Ó, Ú, Ý. Z нет, поэтому алфавит заканчивается:… X, Y, Ý, Þ, Æ, Ö.

- Обе буквы также использовались англосаксонскими писцами, которые также использовали руническую букву Винн для обозначения /w/.

- Þ ( называемый шипом; нижний регистр þ) также является рунической буквой.

- Ð (называется eth; нижний регистр ð) — это буква D с добавленным штрихом.

- Kiowa упорядочивается по фонетическим принципам, как и Брахманское письмо, а не в историческом латинском порядке. Сначала идут гласные, затем прекращаются согласные, идущие от передней части к задней части рта, и от отрицательного к положительному время начала голоса, затем аффрикаты, щелочные, жидкие и назальные:

-

- A, AU, E, I, O, U, B, F, P, V, D, J, T, TH, G, C, K, Q, CH, X, S, Z, L, Y, W, H, M, N

- В литовском, конкретно литовские буквы идут после своих латинских оригиналов. Другое изменение: Y идет непосредственно перед J :… G, H, I, Į, Y, J, K…

- In Польский, в частности, польские буквы, полученные из латинского алфавита, сравниваются после их оригиналов: A, Ą, B, C, Ć, D, E, Ę,…, L, Ł, M, N, Ń, O, Ó, P,…, S, Ś, T,…, Z, Ź, Ż. Орграфы для целей сопоставления обрабатываются так, как если бы они были двумя отдельными буквами.

- В португальском порядок сортировки такой же, как в английском: A, B, C, D, E, F, G, H, I, J, K, L, M, N, O, P, Q, R, S, T, U, V, W, X, Y, Z. Диграфы и буквы с диакритическими знаками не включаются алфавит.

- В румынском специальные символы, полученные из латинского алфавита, сортируются после их оригиналов: A, Ă, Â,…, I, Î,…, S, Ș, T, Ț,…, Z.

- Испанский трактовал (до 1994) «CH» и «LL» как отдельные буквы, давая порядок cinco, credo, chispa и lomo, luz, лама. Это уже не так, поскольку в 1994 г. RAE перешло на более традиционное использование, и теперь LL сопоставляется между LK и LM, а CH — между CG и CI. Шесть символов с диакритическими знаками Á, É, Í, Ó, Ú, Ü рассматриваются как исходные буквы A, E, I, O, U, например: radio, ráfaga, rana, rápido, rastrillo. Единственный вопрос сопоставления, относящийся к испанскому языку, — это Ñ (eñe ) как другая буква, сопоставленная после N.

- В шведском алфавите есть три дополнительных гласных, помещенный в его конец (…, X, Y, Z, Å, Ä, Ö ), аналогично датскому и норвежскому алфавиту, но с другими глифами и другим порядком сортировки. Буква «W» рассматривалась как вариант «V», но в 13-м издании Svenska Akademiens ordlista (2006) «W» считалась отдельной буквой.

- В В турецком алфавите есть 6 дополнительных букв: ç, ğ, ı, ö, ş и ü (но не q, w и x). Они сопоставляются с ç после c, ğ после g, ı до i, ö после o, ş после s и ü после u. Первоначально, когда в 1928 году был введен алфавит, ı был сопоставлен после i, но порядок был изменен позже, так что буквы, имеющие форму, содержащую точки, седили или другие украшения, всегда следовали за буквами с соответствующими голыми формами. Обратите внимание, что в турецкой орфографии буква I — это маджускула без точки ı, тогда как İ — это маджускула с точкой i.

- Во многих тюркских языках (таких как азербайджанский или орфография Jaꞑalif для татарского ), раньше была буква Gha (Ƣƣ), которая находилась между G и Н. В настоящее время он не используется.

- В вьетнамском есть 7 дополнительных букв: ă, â, đ, ê, ô, ơ, ư, а f, j, w, z отсутствуют, хотя они все еще используются (например, адрес в Интернете, иностранный заемный язык). «f» заменяется комбинацией «ph». То же, что и для «w», равно «qu».

- В Volapük ä, ö и ü считаются отдельными буквами и сопоставляются отдельно (a, ä, b…o, ö, p… u, ü, v), а q и w отсутствуют.

- В валлийском орграфы CH, DD, FF, NG, LL, PH, RH и TH обрабатываются как отдельные буквы, и каждая из них указывается после первого символа пары (за исключением NG, который указан после G), в результате получается порядок A, B, C, CH, D, DD, E, F, FF, G, NG, H и т. Д. Однако иногда случается, что сложение слов приводит к сопоставлению двух букв, которые не образуют орграф. Примером может служить слово LLONGYFARCH (составленное из LLON + GYFARCH). Это приводит к такому упорядочению, как, например, LAWR, LWCUS, LLONG, LLOM, LLONGYFARCH (NG — это орграф в LLONG, но не в LLONGYFARCH). Комбинация букв R + H (в отличие от орграфа RH) может аналогичным образом возникать при сопоставлении в составных словах, хотя это, как правило, не приводит к появлению пар, в которых неправильная идентификация может повлиять на упорядочение. Для других потенциально сбивающих с толку сочетаний букв, которые могут возникнуть, а именно D + D и L + L, в написании используется дефис (например, AD-DAL, CHWIL-LYS).

Автоматизация

Алгоритмы сопоставления (в сочетании с алгоритмами сортировки ) используются в компьютерном программировании для размещения строк в алфавитном порядке. Стандартным примером является алгоритм сортировки Unicode, который можно использовать для помещения строк, содержащих любые символы Unicode, в алфавитный порядок (расширение). Его можно сделать так, чтобы он соответствовал большинству языковых соглашений, описанных выше, настроив его таблицу сопоставления по умолчанию. Несколько таких приспособлений собраны в Common Locale Data Repository.

Подобные упорядочения

Принцип, лежащий в основе алфавитного упорядочения, все еще может применяться к языкам, которые, строго говоря, не используют алфавит — например, они могут быть написаны с использованием слогового письма или abugida — при условии, что используемые символы имеют установленный порядок.

Для логографических систем письма, таких как китайский hanzi или японский кандзи, метод сортировки по радикалам и штрихам часто используется как способ определения порядка символов. В японском языке иногда используется порядок произношения, чаще всего в порядке Годзюон, но иногда и в более старом порядке Ироха.

В математике лексикографический порядок — это средство упорядочивания последовательностей способом, аналогичным тому, который используется для создания алфавитного порядка.

Некоторые компьютерные приложения используют версию алфавитного порядка это может быть достигнуто с помощью очень простого алгоритма, основанного исключительно на кодах ASCII или Unicode для символов. Это может иметь нестандартные эффекты, например размещение всех заглавных букв перед строчными. См. ASCIIбетальный порядок.

A Словарь рифм основан на сортировке слов в алфавитном порядке, начиная с последней буквы слова.

См. Также

- Сопоставление

- Сортировка

Ссылки

Дополнительная литература

- Chauvin, Yvonne. Pratique du classement alphabétique. 4e éd. Paris: Bordas, 1977. ISBN 2-04-010155-1

Внешние ссылки

- Упорядочьте любой список в алфавитном порядке с помощью Alphabetizer

- Сортировочные списки в Интернете в Алфавитный порядок с использованием алфавита

Definition from Wiktionary, the free dictionary

Jump to navigation

Jump to search

Pages in category «English words that use all vowels in alphabetical order»

The following 32 pages are in this category, out of 32 total.

A

- abstemious

- abstemiously

- abstenious

- abstentious

- acedious

- acerbitous

- acheilous

- acheirous

- adecticous

- aerious

- affectious

- affectiously

- anemious

- annelidous

- anteriour

- anteriourly

- arsenious

- arterious

- avenious

B

- bacterious

C

- caesious

F

- facetious

- facetiously

- fracedinous

L

- larcenious

M

- majestious

- materious

P

- placentious

T

- tragedious

- transhemizygous

- transtendinous

- travertinous

Retrieved from «https://en.wiktionary.org/w/index.php?title=Category:English_words_that_use_all_vowels_in_alphabetical_order&oldid=59328585»

Category:

- English terms by orthographic property

We will discuss here about the alphabetical order, which is

also known as ABC order.

To list the words in alphabetical order we need to use the

alphabets.

A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z

I. Read the list of the names of the sporting activities and

color in red the first letter of each word.

1. athletics 2.

badminton 3. cricket 4. diving

5. equestrian 6.

football 7. gymnastics 8. hockey

Now let us write the letter in order from 1 to 8. What do

you notice about the order of these words?

The words follow the order of the English alphabet; a, b, c, d, e, f, g, h, i, j, k, l, m, n, o, p, q, r, s, t, u, v, w, x, y, z. This order of alphabets is known as the alphabetical order.

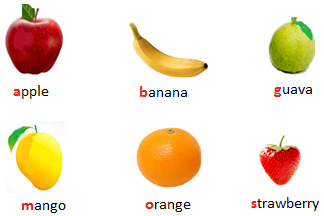

II. Read the names of these fruits and color in red the first letter of these fruits.

Then arrange the names in the correct ABC order or in

alphabetical order.

Now the names of these fruits are in order.

III. How can we arrange the following words in alphabetical

order with the same letter?

apple arrow angel acorn

Notice all the words start with the same letter i.e., a, we

must look at the second letter in each word to arrange them in alphabetical

order. So, the alphabetical order would be:

acorn angel apple arrow

IV. How can we arrange the following words in alphabetical

order with the first two letter same?

car cat can cap

Look at the first letter of the words is c and the second letter is a, which is same in all the words. When words have the same

first two letters, we must then, look at the third letter to arrange in

alphabetical order. So, the alphabetical order would be:

can cap car cat

English Grammar and Composition

From Alphabetical Order to HOME PAGE

All the words in a dictionary are listed alphabetically.

This quiz looks at the alphabetical order of words. It asks children to alphabetise groups of words. This game builds upon the National Curriculum’s expectation that all KS1 children know the order of the alphabet. This quiz is an extension to the Alphabetical Order (Letters) quiz and is designed for Year 2 pupils. It will help with their command of literacy and, of course, the English language.

When putting words in alphabetical order, we focus on the first letter of each word. To make sure the words are in the correct order, you may need to sing the alphabet in your head each time.

To see a larger image, click on the picture.

1.

Put these words in order: face, nose, eyes, mouth.

eyes, face, nose, mouth

face, eyes, mouth, nose

eyes, mouth, nose, face

eyes, face, mouth, nose

2.

Look at the second letter to help you. Put these words in order: gas, grass, gold, gum.

gas, gold, grass, gum

gum, gold, grass, gold

gas, gum, grass, gold

gas, gold, gum, grass

3.

Put these words in order: snow, ice, cold, winter, freezing

cold, ice, freezing, snow, winter

cold, freezing, ice, snow, winter