A sign in a shop window in Italy proclaims these silent clocks make «No Tic Tac» [sic], in imitation of the sound of a clock.

Onomatopoeia[note 1] is the use or creation of a word that phonetically imitates, resembles, or suggests the sound that it describes. Such a word itself is also called an onomatopoeia. Common onomatopoeias include animal noises such as oink, meow (or miaow), roar, and chirp. Onomatopoeia can differ between languages: it conforms to some extent to the broader linguistic system;[6][7] hence the sound of a clock may be expressed as tick tock in English, tic tac in Spanish and Italian (shown in the picture), dī dā in Mandarin, kachi kachi in Japanese, or tik-tik in Hindi.

The English term comes from the Ancient Greek compound onomatopoeia, ‘name-making’, composed of onomato— ‘name’ and —poeia ‘making’. Thus, words that imitate sounds can be said to be onomatopoeic or onomatopoetic.[8]

Uses

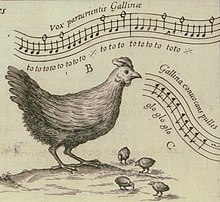

According to Musurgia Universalis (1650), the hen makes «to to too», while chicks make «glo glo glo».

In the case of a frog croaking, the spelling may vary because different frog species around the world make different sounds: Ancient Greek brekekekex koax koax (only in Aristophanes’ comic play The Frogs) probably for marsh frogs; English ribbit for species of frog found in North America; English verb croak for the common frog.[9]

Some other very common English-language examples are hiccup, zoom, bang, beep, moo, and splash. Machines and their sounds are also often described with onomatopoeia: honk or beep-beep for the horn of an automobile, and vroom or brum for the engine. In speaking of a mishap involving an audible arcing of electricity, the word zap is often used (and its use has been extended to describe non-auditory effects of interference).

Human sounds sometimes provide instances of onomatopoeia, as when mwah is used to represent a kiss.[10]

For animal sounds, words like quack (duck), moo (cow), bark or woof (dog), roar (lion), meow/miaow or purr (cat), cluck (chicken) and baa (sheep) are typically used in English (both as nouns and as verbs).

Some languages flexibly integrate onomatopoeic words into their structure. This may evolve into a new word, up to the point that the process is no longer recognized as onomatopoeia. One example is the English word bleat for sheep noise: in medieval times it was pronounced approximately as blairt (but without an R-component), or blet with the vowel drawled, which more closely resembles a sheep noise than the modern pronunciation.

An example of the opposite case is cuckoo, which, due to continuous familiarity with the bird noise down the centuries, has kept approximately the same pronunciation as in Anglo-Saxon times and its vowels have not changed as they have in the word furrow.

Verba dicendi (‘words of saying’) are a method of integrating onomatopoeic words and ideophones into grammar.

Sometimes, things are named from the sounds they make. In English, for example, there is the universal fastener which is named for the sound it makes: the zip (in the UK) or zipper (in the U.S.) Many birds are named after their calls, such as the bobwhite quail, the weero, the morepork, the killdeer, chickadees and jays, the cuckoo, the chiffchaff, the whooping crane, the whip-poor-will, and the kookaburra. In Tamil and Malayalam, the word for crow is kaakaa. This practice is especially common in certain languages such as Māori, and so in names of animals borrowed from these languages.

Cross-cultural differences

Although a particular sound is heard similarly by people of different cultures, it is often expressed through the use of different consonant strings in different languages. For example, the snip of a pair of scissors is cri-cri in Italian,[11] riqui-riqui in Spanish,[11] terre-terre[11] or treque-treque[citation needed] in Portuguese, krits-krits in modern Greek,[11] cëk-cëk in Albanian,[citation needed] and katr-katr in Hindi.[citation needed] Similarly, the «honk» of a car’s horn is ba-ba (Han: 叭叭) in Mandarin, tut-tut in French, pu-pu in Japanese, bbang-bbang in Korean, bært-bært in Norwegian, fom-fom in Portuguese and bim-bim in Vietnamese.[citation needed]

Onomatopoeic effect without onomatopoeic words

An onomatopoeic effect can also be produced in a phrase or word string with the help of alliteration and consonance alone, without using any onomatopoeic words. The most famous example is the phrase «furrow followed free» in Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s The Rime of the Ancient Mariner. The words «followed» and «free» are not onomatopoeic in themselves, but in conjunction with «furrow» they reproduce the sound of ripples following in the wake of a speeding ship. Similarly, alliteration has been used in the line «as the surf surged up the sun swept shore …» to recreate the sound of breaking waves in the poem «I, She and the Sea».

Comics and advertising

A sound effect of breaking a door

Comic strips and comic books make extensive use of onomatopoeia. Popular culture historian Tim DeForest noted the impact of writer-artist Roy Crane (1901–1977), the creator of Captain Easy and Buz Sawyer:

- It was Crane who pioneered the use of onomatopoeic sound effects in comics, adding «bam,» «pow» and «wham» to what had previously been an almost entirely visual vocabulary. Crane had fun with this, tossing in an occasional «ker-splash» or «lickety-wop» along with what would become the more standard effects. Words as well as images became vehicles for carrying along his increasingly fast-paced storylines.[12]

In 2002, DC Comics introduced a villain named Onomatopoeia, an athlete, martial artist, and weapons expert, who often speaks pure sounds.[clarification needed]

Advertising uses onomatopoeia for mnemonic purposes, so that consumers will remember their products, as in Alka-Seltzer’s «Plop, plop, fizz, fizz. Oh, what a relief it is!» jingle, recorded in two different versions (big band and rock) by Sammy Davis, Jr.

Rice Krispies (US and UK) and Rice Bubbles (AU)[clarification needed] make a «snap, crackle, pop» when one pours on milk. During the 1930s, the illustrator Vernon Grant developed Snap, Crackle and Pop as gnome-like mascots for the Kellogg Company.

Sounds appear in road safety advertisements: «clunk click, every trip» (click the seatbelt on after clunking the car door closed; UK campaign) or «click, clack, front and back» (click, clack of connecting the seat belts; AU campaign) or «click it or ticket» (click of the connecting seat belt, with the implied penalty of a traffic ticket for not using a seat belt; US DOT (Department of Transportation) campaign).

The sound of the container opening and closing gives Tic Tac its name.

Manner imitation

In many of the world’s languages, onomatopoeic-like words are used to describe phenomena beyond the purely auditive. Japanese often uses such words to describe feelings or figurative expressions about objects or concepts. For instance, Japanese barabara is used to reflect an object’s state of disarray or separation, and shiiin is the onomatopoetic form of absolute silence (used at the time an English speaker might expect to hear the sound of crickets chirping or a pin dropping in a silent room, or someone coughing). In Albanian, tartarec is used to describe someone who is hasty. It is used in English as well with terms like bling, which describes the glinting of light on things like gold, chrome or precious stones. In Japanese, kirakira is used for glittery things.

Examples in media

- James Joyce in Ulysses (1922) coined the onomatopoeic tattarrattat for a knock on the door.[13] It is listed as the longest palindromic word in The Oxford English Dictionary.[14]

- Whaam! (1963) by Roy Lichtenstein is an early example of pop art, featuring a reproduction of comic book art that depicts a fighter aircraft striking another with rockets with dazzling red and yellow explosions.

- In the 1960s TV series Batman, comic book style onomatopoeic words such as wham!, pow!, biff!, crunch! and zounds! appear onscreen during fight scenes.

- Ubisoft’s XIII employed the use of comic book onomatopoeic words such as bam!, boom! and noooo! during gameplay for gunshots, explosions and kills, respectively. The comic-book style is apparent throughout the game and is a core theme, and the game is an adaptation of a comic book of the same name.

- The chorus of American popular songwriter John Prine’s song «Onomatopoeia» incorporates onomatopoeic words: «Bang! went the pistol», «Crash! went the window», «Ouch! went the son of a gun».

- The marble game KerPlunk has an onomatopoeic word for a title, from the sound of marbles dropping when one too many sticks has been removed.

- The Nickelodeon cartoon’s title KaBlam! is implied to be onomatopoeic to a crash.

- Each episode of the TV series Harper’s Island is given an onomatopoeic name which imitates the sound made in that episode when a character dies. For example, in the episode titled «Bang» a character is shot and fatally wounded, with the «Bang» mimicking the sound of the gunshot.

- Mad Magazine cartoonist Don Martin, already popular for his exaggerated artwork, often employed creative comic-book style onomatopoeic sound effects in his drawings (for example, thwizzit is the sound of a sheet of paper being yanked from a typewriter). Fans have compiled The Don Martin Dictionary, cataloging each sound and its meaning.

Cross-linguistic examples

In linguistics

A key component of language is its arbitrariness and what a word can represent,[clarification needed] as a word is a sound created by humans with attached meaning to said sound.[15] No one can determine the meaning of a word purely by how it sounds. However, in onomatopoeic words, these sounds are much less arbitrary; they are connected in their imitation of other objects or sounds in nature. Vocal sounds in the imitation of natural sounds doesn’t necessarily gain meaning, but can gain symbolic meaning.[clarification needed][16] An example of this sound symbolism in the English language is the use of words starting with sn-. Some of these words symbolize concepts related to the nose (sneeze, snot, snore). This does not mean that all words with that sound relate to the nose, but at some level we recognize a sort of symbolism associated with the sound itself. Onomatopoeia, while a facet of language, is also in a sense outside of the confines of language.[17]

In linguistics, onomatopoeia is described as the connection, or symbolism, of a sound that is interpreted and reproduced within the context of a language, usually out of mimicry of a sound.[18] It is a figure of speech, in a sense. Considered a vague term on its own, there are a few varying defining factors in classifying onomatopoeia. In one manner, it is defined simply as the imitation of some kind of non-vocal sound using the vocal sounds of a language, like the hum of a bee being imitated with a «buzz» sound. In another sense, it is described as the phenomena of making a new word entirely.

Onomatopoeia works in the sense of symbolizing an idea in a phonological context, not necessarily constituting a direct meaningful word in the process.[19] The symbolic properties of a sound in a word, or a phoneme, is related to a sound in an environment, and are restricted in part by a language’s own phonetic inventory, hence why many languages can have distinct onomatopoeia for the same natural sound. Depending on a language’s connection to a sound’s meaning, that language’s onomatopoeia inventory can differ proportionally. For example, a language like English generally holds little symbolic representation when it comes to sounds, which is the reason English tends to have a smaller representation of sound mimicry then a language like Japanese that overall has a much higher amount of symbolism related to the sounds of the language.

Evolution of language

In ancient Greek philosophy, onomatopoeia was used as evidence for how natural a language was: it was theorized that language itself was derived from natural sounds in the world around us. Symbolism in sounds was seen as deriving from this.[20] Some linguists hold that onomatopoeia may have been the first form of human language.[17]

Role in early language acquisition

When first exposed to sound and communication, humans are biologically inclined to mimic the sounds they hear, whether they are actual pieces of language or other natural sounds.[21] Early on in development, an infant will vary his/her utterances between sounds that are well established within the phonetic range of the language(s) most heavily spoken in their environment, which may be called «tame» onomatopoeia, and the full range of sounds that the vocal tract can produce, or «wild» onomatopoeia.[19] As one begins to acquire one’s first language, the proportion of «wild» onomatopoeia reduces in favor of sounds which are congruent with those of the language they are acquiring.

During the native language acquisition period, it has been documented that infants may react strongly to the more wild-speech features to which they are exposed, compared to more tame and familiar speech features. But the results of such tests are inconclusive.

In the context of language acquisition, sound symbolism has been shown to play an important role.[16] The association of foreign words to subjects and how they relate to general objects, such as the association of the words takete and baluma with either a round or angular shape, has been tested to see how languages symbolize sounds.

In other languages

Japanese

The Japanese language has a large inventory of ideophone words that are symbolic sounds. These are used in contexts ranging from day to day conversation to serious news.[22] These words fall into four categories:

- Giseigo: mimics humans and animals. (e.g. wanwan for a dog’s bark)

- Giongo: mimics general noises in nature or inanimate objects. (e.g. zaazaa for rain on a roof)

- Gitaigo: describes states of the external world

- Gijōgo: describes psychological states or bodily feelings.

The two former correspond directly to the concept of onomatopoeia, while the two latter are similar to onomatopoeia in that they are intended to represent a concept mimetically and performatively rather than referentially, but different from onomatopoeia in that they aren’t just imitative of sounds. For example, shiinto represents something being silent, just as how an anglophone might say «clatter, crash, bang!» to represent something being noisy. That «representative» or «performative» aspect is the similarity to onomatopoeia.

Sometimes Japanese onomatopoeia produces reduplicated words.[20]

Hebrew

As in Japanese, onomatopoeia in Hebrew sometimes produces reduplicated verbs:[23]: 208

-

- שקשק shikshék «to make noise, rustle».[23]: 207

- רשרש rishrésh «to make noise, rustle».[23]: 208

Malay

There is a documented correlation within the Malay language of onomatopoeia that begin with the sound bu- and the implication of something that is rounded, as well as with the sound of -lok within a word conveying curvature in such words like lok, kelok and telok (‘locomotive’, ‘cove’, and ‘curve’ respectively).[24]

Arabic

The Qur’an, written in Arabic, documents instances of onomatopoeia.[17] Of about 77,701 words, there are nine words that are onomatopoeic: three are animal sounds (e.g., «mooing»), two are sounds of nature (e.g.; «thunder»), and four that are human sounds (e.g., «whisper» or «groan»).

Albanian

There is wide array of objects and animals in the Albanian language that have been named after the sound they produce. Such onomatopoeic words are shkrepse (matches), named after the distinct sound of friction and ignition of the match head; take-tuke (ashtray) mimicking the sound it makes when placed on a table; shi (rain) resembling the continuous sound of pouring rain; kukumjaçkë (Little owl) after its «cuckoo» hoot; furçë (brush) for its rustling sound; shapka (slippers and flip-flops); pordhë (loud flatulence) and fëndë (silent flatulence).

Hindi-Urdu

In Hindi and Urdu, onomatopoeic words like bak-bak, churh-churh are used to indicate silly talk. Other examples of onomatopoeic words being used to represent actions are fatafat (to do something fast), dhak-dhak (to represent fear with the sound of fast beating heart), tip-tip (to signify a leaky tap) etc. Movement of animals or objects is also sometimes represented with onomatopoeic words like bhin-bhin (for a housefly) and sar-sarahat (the sound of a cloth being dragged on or off a piece of furniture). khusr-phusr refers to whispering. bhaunk means bark.

See also

- Anguish Languish

- Japanese sound symbolism

- List of animal sounds

- List of onomatopoeias

- Sound mimesis in various cultures

- Sound symbolism

- Vocal learning

Notes

- ^ ;[1][2] from the Greek ὀνοματοποιία;[3] ὄνομα for «name»[4] and ποιέω for «I make»,[5] adjectival form: «onomatopoeic» or «onomatopoetic»; also onomatopœia

References

Citations

- ^ Wells, John C. (2008), Longman Pronunciation Dictionary (3rd ed.), Longman, ISBN 978-1-4058-8118-0

- ^ Roach, Peter (2011), Cambridge English Pronouncing Dictionary (18th ed.), Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-15253-2

- ^ ὀνοματοποιία, Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon, on Perseus

- ^ ὄνομα, Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon, on Perseus

- ^ ποιέω, Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon, on Perseus

- ^ Onomatopoeia as a Figure and a Linguistic Principle, Hugh Bredin, The Johns Hopkins University, Retrieved November 14, 2013

- ^ Definition of Onomatopoeia, Retrieved November 14, 2013

- ^ onomatopoeia at merriam-webster.com. Retrieved 12 December 2021.

- ^ Basic Reading of Sound Words-Onomatopoeia, Yale University, retrieved October 11, 2013

- ^ «English Oxford Living Dictionaries». Archived from the original on December 29, 2016.

- ^ a b c d Anderson, Earl R. (1998). A Grammar of Iconism. Fairleigh Dickinson University Press. p. 112. ISBN 9780838637647.

- ^ DeForest, Tim (2004). Storytelling in the Pulps, Comics, and Radio: How Technology Changed Popular Fiction in America. McFarland. ISBN 9780786419029.

- ^ James Joyce (1982). Ulysses. Editions Artisan Devereaux. pp. 434–. ISBN 978-1-936694-38-9.

… I was just beginning to yawn with nerves thinking he was trying to make a fool of me when I knew his tattarrattat at the door he must …

- ^ O.A. Booty (January 1, 2002). Funny Side of English. Pustak Mahal. pp. 203–. ISBN 978-81-223-0799-3.

The longest palindromic word in English has twelve letters: tattarrattat. This word, appearing in the Oxford English Dictionary, was invented by James Joyce and used in his book Ulysses (1922), and is an imitation of the sound of someone [farting].

- ^ Assaneo, María Florencia; Nichols, Juan Ignacio; Trevisan, Marcos Alberto (January 1, 2011). «The anatomy of onomatopoeia». PLOS ONE. 6 (12): e28317. Bibcode:2011PLoSO…628317A. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0028317. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 3237459. PMID 22194825.

- ^ a b RHODES, R (1994). «Aural Images». In J. Ohala, L. Hinton & J. Nichols (Eds.) Sound Symbolism. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- ^ a b c Seyedi, Hosein; Baghoojari, ELham Akhlaghi (May 2013). «The Study of Onomatopoeia in the Muslims’ Holy Write: Qur’an» (PDF). Language in India. 13 (5): 16–24.

- ^ Bredin, Hugh (August 1, 1996). «Onomatopoeia as a Figure and a Linguistic Principle». New Literary History. 27 (3): 555–569. doi:10.1353/nlh.1996.0031. ISSN 1080-661X. S2CID 143481219.

- ^ a b Laing, C. E. (September 15, 2014). «A phonological analysis of onomatopoeia in early word production». First Language. 34 (5): 387–405. doi:10.1177/0142723714550110. S2CID 147624168.

- ^ a b Osaka, Naoyuki (1990). «Multidimensional Analysis of Onomatopoeia – A note to make sensory scale from word». Studia phonologica. 24: 25–33. hdl:2433/52479. NAID 120000892973.

- ^ Assaneo, María Florencia; Nichols, Juan Ignacio; Trevisan, Marcos Alberto (December 14, 2011). «The Anatomy of Onomatopoeia». PLOS ONE. 6 (12): e28317. Bibcode:2011PLoSO…628317A. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0028317. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 3237459. PMID 22194825.

- ^ Inose, Hiroko. «Translating Japanese Onomatopoeia and Mimetic Words.» N.p., n.d. Web.

- ^ a b c Zuckermann, Ghil’ad (2003), Language Contact and Lexical Enrichment in Israeli Hebrew. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 9781403917232 / ISBN 9781403938695 [1]

- ^ WILKINSON, R. J. (January 1, 1936). «Onomatopoeia in Malay». Journal of the Malayan Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society. 14 (3 (126)): 72–88. JSTOR 41559855.

General references

- Crystal, David (1997). The Cambridge Encyclopedia of Language (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-55967-7.

- Smyth, Herbert Weir (1920). Greek Grammar. Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press. p. 680. ISBN 0-674-36250-0.

External links

- Derek Abbott’s Animal Noise Page

- Over 300 Examples of Onomatopoeia

- BBC Radio 4 show discussing animal noises

- Tutorial on Drawing Onomatopoeia for Comics and Cartoons (using fonts)

- WrittenSound, onomatopoeic word list

- Examples of Onomatopoeia

Onomatopoeia. First of all, what is it?

Well, onomatopoeia is the creation of words that

imitate natural sounds, like for example the word ‘hiss’ which both imitates

and has the meaning of the sound of a snake.

There are lots of words like this, so it’s impossible to cover them all in one post, but let’s at least have a look at some of them.

But before we do, maybe you prefer to watch a video? If so, here it is:

Examples of Onomatopoeia

Let’s now have a look at some examples of onomatopoeia. I’m going to divide the words into a couple of groups:

Birds

Let me start with words that imitate sounds produced by birds:

| the sound produced by: | |

| caw |

a crow or raven |

| cheep |

a young bird |

| cluck | a hen |

| tweet |

a small bird |

| quack | a duck |

Other Animals

And now some words imitating sounds produced by other animals:

| the sound produced by: | |

| baa | a sheep |

| roar | a lion |

| neigh | a horse |

| oink | a pig |

| croak | a frog |

| mew | a cat |

| moo | a cow |

| purr | a contented cat |

Objects

A lot of objects produce sounds as well. Here are some examples of onomatopoeic words:

| the sound produced by: | |

| ding-dong | a large bell |

| twang | a plucked violin string |

| clang | iron gates closing |

| bang | a gun |

| vroom | an engine running at high speed |

| tick-tock | a clock |

| beep | an electronic device |

| clack | two objects hitting sharply together |

| clip-clop | a horse’s hoofs on a hard surface |

Other Examples of Onomatopoeia

Finally, have a look at some other examples of onomatopoeia that don’t fit so well in any of the other categories, but are still worth mentioning:

| the sound produced by: | |

| crackle | logs in the fire |

| gurgle | boiling or bubbling water |

| ping | a spoon tapping an empty wine glass |

| pitter-patter | the rain |

| clap | hands struck together |

| gargle | someone rinsing their mouth or throat |

| sizzle | frying fat |

| screech | a car braking at speed |

And there are hundreds of other examples of onomatopoeia like this. Maybe you know some yourself?

We may receive a commission when you make a purchase from one of our links for products and services we recommend. As an Amazon Associate we earn from qualifying purchases. Thank you for support!

Onomatopoeia is a common literary device to use while writing that many people use every single day – often times without even realizing they are using a form of it!

If you’re curious about onomatopoeia, we will cover the definition of the word, plus give you some examples and a list of onomatopoeia words you can use in your writing!

What is Onomatopoeia?

Onomatopoeia at first glance looks like a long word and it may seem to be hard to pronounce and spell. But don’t let that hold you back from using this literary device in your writing – it’s actually a quite basic concept and easy to understand. It’s not scary at all, we promise!

You’ve probably heard of words like “buzz” or “ring” or “bark”. All of these words are sounds. By definition, onomatopoeia is a word the imitates its sound.

Words that imitate a sound can vary depending on regions, countries, and language. For the most part there are plenty of onomatopoeia words to choose from to use in your writing, whether you are writing poetry or an essay or even a novel.

Any word that is used to describe and mimic a sound is an example of the types of words you would want to use in your writing.

You can use onomatopoeia in a number of different styles of writing, but it is most common for descriptive writing, since it is often used to describe the sound that something might make.

However, adding it to other writing styles, such as expository or even persuasive can help you write a stronger piece that will be vividly remembered by those who read the work.

The Big List of Onomatopoeia words :

- Achoo

- Ahem

- Arf

- Arghh

- Bang

- Bark

- Boo

- Brrng

- Bump

- Buzz

- Cackle

- Chatter

- Cheer

- Clap

- Clank

- Click

- Crackle

- Crash

- Crunch

- Ding-Dong

- Drip

- Eek

- Fizz

- Flipflop

- Growl

- Haha

- Hiccup

- Honk

- Howl

- Hush

- Jingle

- Jangle

- Knock

- Lala

- Meow

- Moan

- Moo

- Murmur

- Neigh

- Oink

- Plop

- Poof

- Pop

- Pow

- Psst

- Quack

- Ribbit

- Ring

- Roar

- Rustle

- Rumble

- Shhh

- Sizzle

- Slap

- Smash

- Smack

- Squish

- Swoosh

- Thud

- Thump

- Tick-Tock

- Whisper

- Whimper

- Woof

- Zip

- Zoom

These are likely many words we may have overlooked in this list! It is hard to realize how much we use these words in every single day conversations we might have!

Do you see the many ways these words can be used to make your writing more descriptive? Each of these words make it very easy to imagine the sounds and visualize a specific scene.

Now that you understand the basic meaning of onomatopoeia and have a list of words to use, you have all that you need to start using these words in your writing!

Famous Examples of Onomatopoeia

[sc name=”disclosure”]

There are many authors who are well known for their use onomatopoeia. Many examples can be found simply by reading a couple of Dr. Suess books, one popular book being this one: Mr. Brown Can Moo, Can You? – such a fun book to read!

The Edgar Allen Poe poem The Raven is another example which uses words that mimic a sound.

Which examples of onomatopoeia can you spot in the excerpt below?

Once upon a midnight dreary, while I pondered, weak and weary,

Over many a quaint and curious volume of forgotten lore—

While I nodded, nearly napping, suddenly there came a tapping,

As of some one gently rapping, rapping at my chamber door.

“’Tis some visitor,” I muttered, “tapping at my chamber door—

Only this and nothing more.”

These are some great examples of ways many famous writers have used onomatopoeia in their writing!

Additional Examples of Onomatopoeia in Use for Poems & Poetry

Would you like to see some examples of Onomatopoeia in use? Here are some poetry verses we wrote specifically to inspire you to learn how to use words that mimic sounds in your writing!

Game Time

The crowd roars

over the swoosh of the ball

through the net

so loud you might miss –

the thud of it falling

to the floor.

The Sound of Happy

What is the sound of happy?

Is it hands clapping?

Is it the thump of you heart in your chest?

Is it the zoom of the planes overhead?

Is it a good haha?

Or the absence of a boo-hoo-hoo?

What is the sound of happy to you?

Why Should I Use Onomatopoeia in my writing?

The biggest reason you might want to use this popular literary device that uses words which mimic a sound while writing is because it adds a lot of sensory description to your writing. These types of words appeal to the senses, which is a great way to help you connect to your readers.

Because the word mimics a sound, it also helps paint a better visual picture in your audience’s minds. This is especially helpful when writing for children as an audience for your book!

Using words that imitate a sound can also help you show and not tell in your writing. This is very important when you are writing a novel, as you want your readers to stay engaged and interested. This can also help your readers connect to your character better.

When you are writing poetry, you can have a lot of fun with these words! These types of words give you endless ideas and inspiration for different types of things to write about! In fact, we actually include many ideas for onomatopoeia in several of our writing prompts on this website!

How Will You Use Onomatopoeia in Your Writing?

I hope you find these tips on ways to use onomatopoeia in your writing and poetry helpful. What will you write that is fun and uses words that mimics a sound? Do you think that using these types of words might help you improve your writing in any way?

And – we need your help! We’ve thought of as many words that mimic a sound as we can think of. Can you think of any words we might have missed that we should include in our onomatopoeia list? Or – comment below with an example sentence that uses one of the words on our list.

Most importantly, I hope you have fun with writing with these word examples – and of course we’d love to hear any additional thoughts and ideas you may have in the comments section below!

Snap, Crackle, Pop: Definition and Examples of Onomatopoeia

The word «hiss» is an example of an onomatopoeia.

Dawid Gabarkiewicz / EyeEm / Getty Images

Updated on January 20, 2020

Onomatopoeia is the use of words that imitate the sounds associated with the objects or actions they refer to (such as hiss or murmur). It can also include made-up words or simply a series of letters, such as zzzzzz to represent a person sleeping or snoring.

The adjective is onomatopoeic or onomatopoetic. An «onomatope» is a particular word that imitates the sound it denotes.

Onomatopoeia is sometimes called a figure of sound rather than a figure of speech. As Malcolm Peet and David Robinson point out in «Leading Questions»:

«Onomatopoeia is a fortunate by-product of meaning; few words and relatively few arrangements of words have sounds which are meaningful in themselves»

Onomatopoeia is heard throughout the world, though different languages may use very different sounding words to represent the same sounds.

Etymology

From the Greek, onoma «name» and poiein «to make, or to «make names.»

Pronunciation:

ON-a-MAT-a-PEE-a

Also Known As:

echo word, echoism

Examples and Observations

«Chug, chug, chug. Puff, puff, puff. Ding-dong, ding-dong. The little train rumbled over the tracks.»

— «Watty Piper» [Arnold Munk], «The Little Engine That Could,» 1930

«Brrrrrrriiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiinng! An alarm clock clanged in the dark and silent room.»

— Richard Wright, «Native Son,» 1940

«I’m getting married in the morning!

Ding dong! the bells are gonna chime.»

— Lerner and Loewe, «Get Me to the Church on Time.» «My Fair Lady,» 1956

«Plop, plop, fizz, fizz, oh what a relief it is.»

— slogan of Alka Seltzer, United States

«Plink, plink, fizz, fizz«

— slogan of Alka Seltzer, United Kingdom

«Two steps down, I heard that pressure-equalizing pop deep in my ears. Warmth hit my skin; sunlight shone through my closed eyelids; I heard the shat-HOOSH, shat-HOOSH of the weaving flats.»

— Stephen King, «11/22/63.» Scribner, 2011

«‘Woop! Woop! That’s the sound of da police,’ KRS-One famously chants on the hook of ‘Sound of da Police’ from 1993’s «Return of the Boombap.» The unmistakable sound he makes in place of the police siren is an example of onomatopoeia, the trope that works by exchanging the thing itself for a linguistic representation of the sound it makes.»

— Adam Bradley, «Book of Rhymes: The Poetics of Hip Hop.» BasicCivitas, 2009

«Flora left Franklin’s side and went to the one-armed bandits spread along one whole side of the room. From where she stood it looked like a forest of arms yanking down levers. There was a continuous clack, clack, clack of levers, then a click, click, click of tumblers coming up. Following this was a metallic poof sometimes followed by the clatter of silver dollars coming down through the funnel to land with a happy smash in the coin receptacle at the bottom of the machine.»

— Rod Serling, «The Fever.» «Stories from the Twilight Zone,» 2013

«Hark, hark!

Bow-wow.

The watch-dogs bark!

Bow-wow.

Hark, hark! I hear

The strain of strutting chanticleer

Cry, ‘Cock-a-diddle-dow!'»

— Ariel in William Shakespeare’s «The Tempest,» Act One, scene 2

«Onomatopoeia every time I see ya

My senses tell me hubba

And I just can’t disagree.

I get a feeling in my heart that I can’t describe. …

It’s sort of whack, whir, wheeze, whine

Sputter, splat, squirt, scrape

Clink, clank, clunk, clatter

Crash, bang, beep, buzz

Ring, rip, roar, retch

Twang, toot, tinkle, thud

Pop, plop, plunk, pow

Snort, snuck, sniff, smack

Screech, splash, squish, squeak

Jingle, rattle, squeal, boing

Honk, hoot, hack, belch.»

— Todd Rundgren, «Onomatopoeia.» «Hermit of Mink Hollow,» 1978

«Klunk! Klick! Every trip»

— U.K. promotion for seatbelts

«[Aredelia] found Starling in the warm laundry room, dozing against the slow rump-rump of a washing machine.»

—Thomas Harris, «Silence of the Lambs,» 1988

Jemimah: It’s called Chitty Chitty Bang Bang.

Truly Scrumptious: That’s a curious name for a motorcar.

Jemimah: But that’s the sound it makes. Listen.

It’s saying chitty chitty, chitty chitty, chitty chitty, chitty chitty, chitty chitty, bang bang! chitty chitty . …

— «Chitty Chitty Bang Bang,» 1968

«Bang! went the pistol,

Crash! went the window

Ouch! went the son of a gun.

Onomatopoeia—

I don’t want to see ya

Speaking in a foreign tongue.»

— John Prine, «Onomatopoeia.» «Sweet Revenge,» 1973

«He saw nothing and heard nothing but he could feel his heart pounding and then he heard the clack on stone and the leaping, dropping clicks of a small rock falling.»

— Ernest Hemingway, «For Whom the Bell Tolls,» 1940

«It went zip when it moved and bop when it stopped,

And whirr when it stood still.

I never knew just what it was and I guess I never will.»

— Tom Paxton, «The Marvelous Toy.» «The Marvelous Toy and Other Gallimaufry,» 1984

«I like the word geezer, a descriptive sound, almost onomatopoeia, and also coot, codger, biddy, battleax, and most of the other words for old farts.»

— Garrison Keillor, «A Prairie Home Companion,» January 10, 2007

Creating Sound Effects in Prose

«A sound theory underlies the onomaht—that we read not only with our eyes but also with our ears. The smallest child, learning to read by reading about bees, needs no translation for buzz. Subconsciously we hear the words on a printed page.

«Like every other device of the writing art, onomatopoeia can be overdone, but it is effective in creating mood or pace. If we skip through the alphabet we find plenty of words to slow the pace: balk, crawl, dawdle, meander, trudge and so on.

«The writer who wants to write ‘fast’ has many choices. Her hero can bolt, dash, hurry or hustle.»

— James Kilpatrick, «Listening to What We Write.» «The Columbus Dispatch,» August 1, 2007

Linguists on Onomatopoeia

«Linguists almost always begin discussions about onomatopoeia with observations like the following: the snip of a pair of scissors is su-su in Chinese, cri-cri in Italian, riqui-riqui in Spanish, terre-terre in Portuguese, krits-krits in modern Greek. … Some linguists gleefully expose the conventional nature of these words, as if revealing a fraud.»

— Earl Anderson, «A Grammar of Iconism.» Fairleigh Dickinson, 1999

A Writer’s Word

«My favorite word is ‘onomatopoeia,’ which defines the use of words whose sound communicates or suggests their meanings. ‘Babble,’ ‘hiss,’ ‘tickle,’ and ‘buzz’ are examples of onomatopoeic usage.

«The word ‘onomatopoeia’ charms me because of its pleasing sound and symbolic precision. I love its lilting alternation of consonant and vowel, its tongue-twisting syllabic complexity, its playfulness. Those who do not know its meaning might guess it to be the name of a creeping ivy, or a bacterial infection, or maybe a small village in Sicily. But those acquainted with the word understand that it, too, in some quirky way, embodies its meaning.

«‘Onomatopoeia’ is a writer’s word and a reader’s nightmare but the language would be poorer without it.»

— Letty Cottin Pogrebin, quoted by Lewis Burke Frumkes in «Favorite Words of Famous People.» Marion Street Press, 2011

The Lighter Side of Onomatopoeia

Russian Negotiator: Why must every American president bound out of an automobile like as at a yacht club while in comparison our leader looks like … I don’t even know what word is.

Sam Seaborn: Frumpy?

Russian Negotiator: I don’t know what «frumpy» is but onomatopoetically sounds right.

Sam Seaborn: It’s hard not to like a guy who doesn’t know frumpy but knows onomatopoeia.

— Ian McShane and Rob Lowe in «Enemies Foreign and Domestic.» «The West Wing,» 2002

«I have a new book, ‘Batman: Cacophony.’ Batman faces off against a character called Onomatopoeia. His shtick is that he doesn’t speak; he just mimics the noises you can print in comic books.»

– Kevin Smith, Newsweek, Oct. 27, 2008

Onomatopoeia

(sound-imitation,

echoism)

is the naming of an action or thing by a more or less exact

reproduction of a natural sound associated with it (babble,

crow, twitter).

Words coined by this

interesting type of word-building are made by imitating different

kinds of sounds that may be produced by animals, birds, insects,

human beings and inanimate objects.

It is of some interest that

sounds produced by the same kind of animal are frequently represented

by quite different sound groups in different languages. For instance,

English dogs bark

(cf.

the Rus.

лаять,

UA.

гавкати)

or howl

(cf. the

Rus. выть,

UA. вити).

The

English cock cries cock-a-doodle-doo

(cf. the

Rus. ку—ка—ре—ку,

UA.

ку-ка-рі-ку).

In England

ducks quack

and frogs

croak (cf.

the Rus. крякать

UA.

крякати

said about

ducks and Rus.

квакать,

UA.

квакати,

said about

frogs). It is only English and Russian/Ukrainian cats who seem

capable of mutual understanding when they meet, for English cats mew

or miaow

(meow). The

same can be said about cows: they moo

(but also

low).

Some names of animals and

especially of birds and insects are also produced by sound-imitation:

crow, cuckoo, humming-bird, whip-poor-will, cricket.

The following desperate letter contains a great number of

sound-imitation words reproducing sounds made by modern machinery:

The Baltimore &

Ohio R. R.

Co.,

Pittsburg, Pa.

Gentlemen:

Why is it that your switch engine has to ding and fizz and spit and

pant and grate and grind and puff and bump and chug and hoot and toot

and whistle and wheeze and howl and clang and growl and thump and

clash and boom and jolt and screech and snarl and snort and slam and

throb and soar and rattle and hiss and yell and smoke and shriek all

night long when I come home from a hard day at the boiler works and

have to keep the dog quiet and the baby quiet so my wife can squawk

at me for snoring in my sleep?

Yours

(From Language

and Humour by

G. G. Pocheptsov.)

The

great majority of motivated words in present-day language are

motivated by reference to other words in the language, to the

morphemes that go to compose them and to their arrangement.

Therefore, even if one hears the noun wage-earner

for

the first time, one understands it, knowing the meaning of the words

wage

and

earn

and

the structural pattern

noun

stem +

verbal

stem+

—er

as

in bread-winner,

skyscraper, strike-breaker.

Sound

imitating or onomatopoeic words are on the contrary motivated with

reference to extra-linguistic reality, they are echoes of

natural sounds (e. g. lullaby,

twang, whiz.) Sound

imitation

(onomatopoeia

or echoism)

is consequently the naming of an action or thing by a more or less

exact reproduction of a sound associated with it. For instance words

naming sounds and movement of water: babble,

blob, bubble, flush, gurgle, gush, splash, etc.

The

term onomatopoeia is from Greek onoma

‘name,

word’ and poiein

‘to

make →

‘the

making of words (in imitation of sounds)’.

It

would, however, be wrong to think that onomatopoeic words reflect the

real sounds directly, irrespective of the laws of the language,

because the same sounds are represented differently in different

languages.

Onomatopoeic words adopt the phonetic features of English

and fall into the combinations peculiar to it. This becomes obvious

when one compares onomatopoeic words crow

and

twitter

and

the words flow

and

glitter

with

which they are rhymed in the following poem:

The cock is crowing,

The stream is flowing.

The small birds twitter,

The lake does glitter,

The

green fields sleep in the sun (Wordsworth).

The

majority of onomatopoeic words used to name sounds or movements are

verbs easily turned into nouns: bang,

boom, bump, hum, rustle, smack, thud, etc.

They are very expressive and

sometimes it is difficult to tell a noun from an interjection.

Consider the following:

Thum

—

crash!

“Six

o’clock, Nurse,” —

crash!

as

the door shut again. Whoever it was had given me the shock of my life

(M. Dickens).

Sound-imitative

words form a considerable part of interjections:

bang!

hush! pooh!

Semantically,

according to the source of sound, onomatopoeic words fall into a few

very definite groups. Many verbs denote sounds produced by human

beings in the process of communication or in expressing their

feelings:

babble,

chatter, giggle, grunt, grumble, murmur, mutter, titter, whine,

whisper,

etc.

Then

there are sounds produced by animals, birds and insects:

buzz,

cackle, croak, crow, hiss, honk, howl, moo, mew, neigh, purr, roar

etc.

Some

birds are named after the sound they make, these are the

crow, the cuckoo, the whippoor-will and

a few others. Besides the verbs imitating the sound of water such as

bubble

or

splash,

there

are others imitating the noise of metallic things: clink,

tinkle, or

forceful motion: clash,

crash, whack, whip, whisk, etc.

The

combining possibilities of onomatopoeic words are limited by usage.

Thus, a contented cat purrs,

while

a similarly sounding verb whirr

is

used about wings. A gun bangs

and

a bow twangs.

R. Southey’s poem “How

Does the Water Come Down at Lodore” is a classical example of the

stylistic possibilities offered by onomatopoeia: the words in it

sound an echo of what the poet sees and describes.

Here it comes sparkling,

And

there it flies darkling …

Eddying and whisking,

Spouting

and frisking, …

And

whizzing and hissing, …

And

rattling and battling, …

And

guggling and struggling, …

And bubbling and troubling

and doubling,

And rushing and flushing

and brushing and gushing,

And

flapping and rapping and clapping and slapping …

And thumping and pumping

and bumping and jumping,

And

dashing and flashing and splashing and clashing …

And at once and all o’er,

with a mighty uproar,

And this way the water

comes down at Lodore.

Once

being coined, onomatopoeic words lend themselves easily to further

word-building and to semantic development. They readily develop

figurative meanings. Croak,

for

instance, means “to make a deep harsh sound”. In its direct

meaning the verb is used about frogs or ravens. Metaphorically it may

be used about a hoarse human voice. A further transfer makes the verb

synonymous to such expressions as “to protest dismally”, “to

grumble dourly”, “to predict evil”.

There is a hypothesis that

sound-imitation as a way of word-formation should be viewed as

something much wider than just the production of words by the

imitation of purely acoustic phenomena. Some scholars suggest that

words may imitate through their sound form certain unacoustic

features and qualities of inanimate objects, actions and processes or

that the meaning of the word can be regarded as the immediate

relation of the sound group to the object. If a young chicken or

kitten is described as fluffy

there

seems to be something in the sound of the adjective that conveys the

softness and the downy quality of its plumage or its fur. Such verbs

as to

glance, to glide, to slide, to slip are

supposed to convey by their very sound the nature of the smooth, easy

movement over a slippery surface. The sound form of the words

shimmer,

glimmer, glitter seems

to reproduce the wavering, tremulous nature of the faint light. The

sound of the verbs to

rush, to dash, to flash may

be said to reflect the brevity, swiftness and energetic nature of

their corresponding actions. The word thrill

has

something in the quality of its sound that very aptly conveys the

tremulous, tingling sensation it expresses.

Some scholars have given serious consideration to this theory.

However, it has not yet been properly developed.

Соседние файлы в предмете [НЕСОРТИРОВАННОЕ]

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

Onomatopoeia refers to a word that phonetically imitates, resembles or suggests the source of the sound that it describes. Onomatopoeia comes from the Greek onomatopoiia meaning ‘word-making.’ It is a word that imitates the sound of a thing. It creates a sound effect that imitates the natural sound made by the described object. Since the word imitates the sound effects, it is not difficult to understand the meaning of an onomatopoeic word, even if you have never seen it before.

Examples of Onomatopoeia

Onomatopoeic words can reflect different sounds: sounds of nature, human voices, animal sounds are the base of most of them. Given below are some onomatopoeic words.

Water: gush, sprinkle, spray, splash, drizzle, drip

Air: swish, whisper, swoosh, whizz, flutter

Humans: giggle, mummer, grunt, chatter, roar, growl, mumble, blurt, hiccup

Animals: meow, baa, tweet, moo, neigh, oink

Collision: boom, bang, crash, clatter, thud, screech

The following sentences use onomatopoeic words (underlined)

We heard a loud bang, and we rushed out of the house.

The kitten meowed and jumped onto her lap.

Ding Dong! The church bells rang.

We ran to the shop in the drizzling rain.

Water gushed out of the underground tunnel.

The two girls giggled loudly.

You might have noticed in the above examples that onomatopoeic words can be used as nouns and verbs.

The book fell with a loud thud. –noun

The lion roared. – verb

Splash

Onomatopoeia is generally used in literature to make descriptions interesting and expressive. The following examples are taken from some famous poets and authors of English.

“How they clang, and clash, and roar!

What a horror they outpour

On the bosom of the palpitating air!

Yet the ear it fully knows,

By the twanging

And the clanging,..”

( ‘The Bells,’ by Edgar Allen Poe)

“Hark, hark!

Bow-wow.

The watch-dogs bark!

Bow-wow.

Hark, hark! I hear

The strain of strutting chanticleer

Cry, ‘cock-a-diddle-dow!’”

(“Tempest” by William Shakespeare)

“Over the cobbles, he clattered and clashed in the dark inn-yard.

He tapped with his whip on the shutters, but all was locked and barred.”

(“The Highwayman” by Alfred Noyes)

Even though onomatopoeic words mimic the natural sounds of the thing it refers to; it is surprising to note that onomatopoeic words can differ from language to language. This is particularly true in the case of animal sounds. For example, let’s see onomatopoeic words that refer to the sound of dogs in different languages.

bow wow – English

wan wan – Japanese

gav gav – Greek

guau-guau- Spanish

ouah! ouah! – French

Onomatopoeia – Summary

- Onomatopeia creates a sound effect that imitates the natural sound made by the described object.

- It is easy to understand Onomatopoeic words since the word mimics its sound.

- Onomatopoeic words can differ from language to language.

- Onomatopoeia is a main literary device used in literary language.

A cat goes meow! A shotgun goes bang! A doorbell goes ding dong! When we imitate sounds, we call those words onomatopoeia. In this fun lesson, I will teach you some useful English words that imitate sounds and noises made by different people, animals, objects, and even the noises made by a well-known breakfast cereal! This will make your conversations more animated and descriptive. You will also encounter these words when reading novels and comic books. Onomatopoeia are NOT the same in every language, so after watching, do the quiz to see if you recognize these sounds in English!

Quiz

Test your understanding of this English lesson

Test your understanding of the English lesson by answering these questions. You will get the answers and your score at the end of the quiz.

LEAVE A COMMENT

Onomatopoeia!!! Pow! Bang! Zoom! These words are all onomatopoeia, words that sound like the thing they describe. In this lesson, we will learn the definition, list and some interesting examples of onomatopoeia.

Onomatopoeia Definition

Onomatopoeia refers to words whose pronunciations imitate the sounds they describe. It can be used to describe the gears of machines working, the horn of a car honking, animal sounds, or any number of other sounds.

A dog’s bark sounds like “woof,” so “woof” is an example of onomatopoeia.

Examples:

- “Miaow, miaow,” went the cat. “Woof, woof,” went the dog.

- “Bang! Bang! You’re dead!” said the child, pointing a plastic gun at me.

- When I shout “Pow!” that means I’ve shot you and you’ve got to pretend to be dead.

Onomatopoeia Words

- Boom!

- Zap!

- Baam

- Pow

- Bag!

- Baang

- Pop

- Bubble

- Purr

- Kapow!

- Buzz

- Yawn

- Huh?

- Crack!

- Zonk

- Biff

- Whap!

- Krunch

- Wow

- Pow pow

- Oops!

- Wham!

- Ooh!

- Smash!

- Kaboom!

- Hmm…

- Ouch

- Dorr!!

- Poof!

- Gulp!

- Aargh!

- Crush!

- Snap!

- Grrrrr!

- Crunch

- Chok!

- Click

- Hoot

- OMG! (Oh my God)

- Oh!

- Bamm!

- WTF (What’s the f***?)

- LOL (Laughing out loud)

- Hey

- Cool

- Bam

- Hiss

- Bang

- Foom

- Choom

- Splash!

- Eek

- Belch

- Babble

- Warble

- Hum

- Slam

- Gasp

- Mumble

- Moan

- Gurgle

- Splat!

- Ka-pow!

- Honk

- Beep

- Vroom

- Clang

- Boing

- Cuckoo

- Whip-poor-will

- Chickadee

- Crash

- Whack

- Thump

- Shush

- Giggle

- Growl

- Whine

- Murmur

- Blurt

- Drip

- Spray

- Whoosh

- Rustle

- Zoom

- Swoosh

- Zing

- Zip

- Tap

- Snip

- Knock

- Rap

- Thwack

- Flap

- Smack

- Creak

- Squeak

- Pop

- Boing

- Sizzle

- Fizzle

- Clack

- Jingle

- Rattle

- Clatter

- Blare

- Shriek

- Ding

- Drum

- Throb

- Twang

- Plink

- Plunk

- Bong

- Squish

- Slush

- Burble

- Gurgle

- Glug

- Splatter

- Fizz

- Plop

- Puff

Onomatopoeia Examples

- The guns went “boom“.

- The boys in the cartoon were punching each other – wham, zap!

- Kim wants to go to this party, huh? Well, we’ll see about that!

- “Crack!” — The first shot rang out, hitting Paolo.

- I thought, “Wow, what a good idea”.

- Oops! I nearly dropped my cup of tea!

- Wham! The car hit the wall.

- Ooh, yes, that would be nice!

- He walked through—and vanished. Poof! Like that.

- Aargh, this thing is so heavy!

- Snap! We’re wearing the same shirts!

- OMG! I’ve never seen anything like it!

- Oh, yeah? I forgot all about it.

- Hey! What are you doing with my car?

- Hey! Cool it! Don’t get so excited!

- Bam! Out of the tube with previous memories veiled and into the light.

- “Bang! Bang! You’re dead!” shouted the small boy.

- Hum, I am sorry but I thought you were French.

- The dishes fell to the floor with a clatter.

- If you’re going to cough, please cover your mouth.

- The cabinet opened with a distinct creak.

- Most cats purr if you pet them behind the ears.

- The earthquake rumbled the foundations of our house.

- The musician used a coin to strum the guitar.

- Mark tried sneaking in the house but the squeak of his shoes woke up Mom.

Onomatopoeia Words | Infographic

Onomatopoeia Words

Last Updated on February 21, 2023

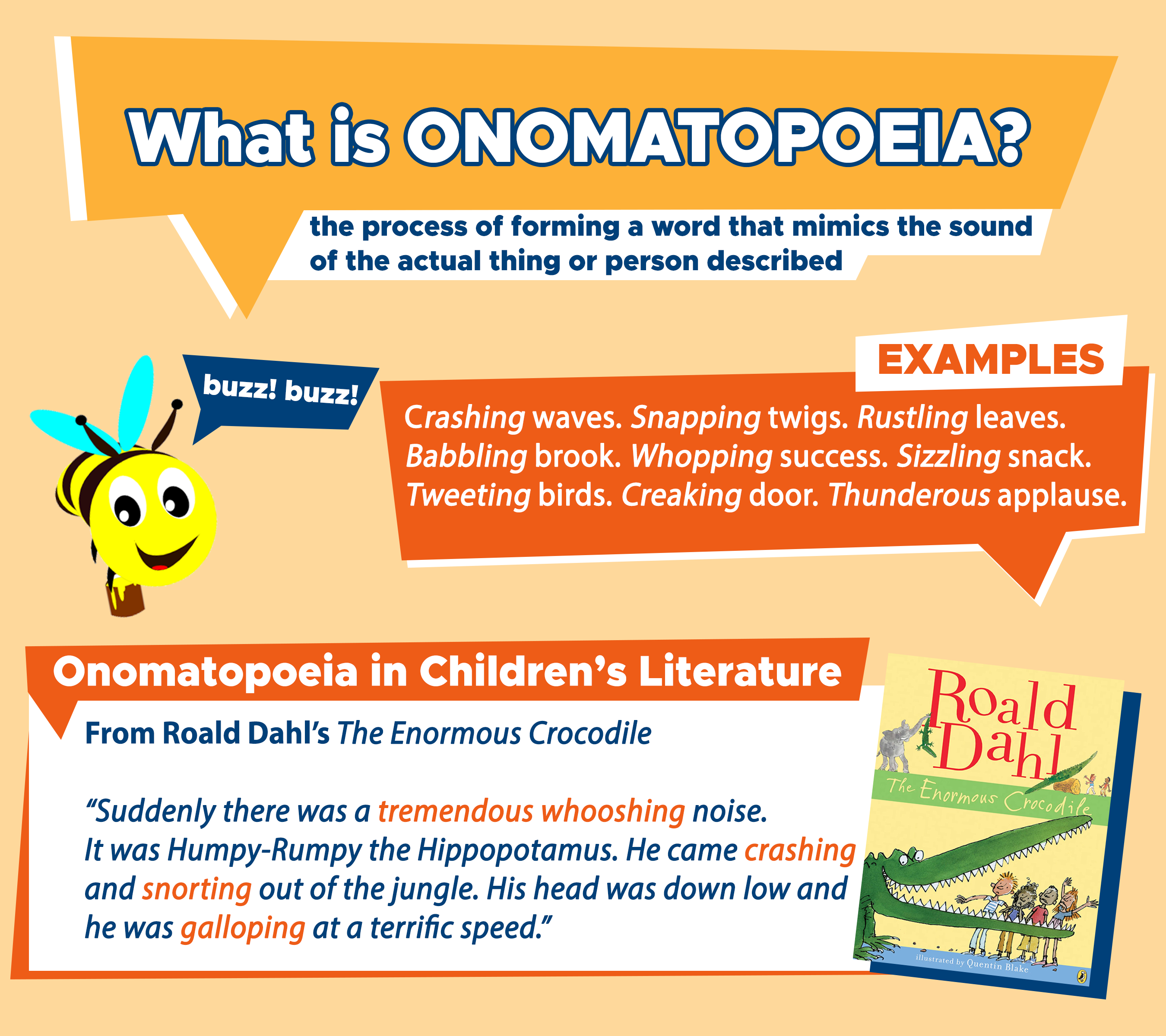

From an early age, we’re taught to identify animals by imitating the sound they make. For example, cats go “meow,” dogs say “woof,” “moo” for cows, and so on. The process of forming a word that mimics the sound of a thing or person is called onomatopoeia, which is also the term for the resulting word. Aside from animal sounds, onomatopoeia is alive in the “clip-clop” of a horse’s hooves, the “tic toc” of a clock, and the “woo” of a crowd. It can also be seen in the buzzing of a bee, the humming of a bird, the smashing of a car, and the creaking of a window.

Onomatopoeia in Everyday Speech

Onomatopoeia is a constant part of our everyday conversation without us realizing it. Recall some words that echo what they actually mean and notice how they intensify our stories. Here are a few examples of onomatopoeia in everyday speech.

- Let’s join the people’s clamor for the president’s resignation.

- She was humming while crossing the road and bam! A ginormous truck hit her!

- The rain has been rapping the roof since last night.

- Peace comes with crashing waves, whispering wind, and rustling trees.

- While Derrick cracks an egg and splatters it on the frying pan, Dale crunches his cereals.

Onomatopoeia in Literature

A powerful literary device, onomatopoeia breathes life into literature and pop culture, particularly in comics and advertising. Readers and listeners alike feel a dramatic effect because of the resonating words and sounds.

Here are some examples of onomatopoeia in children’s literature:

- From Jabberwocky by Lewis Carroll

“And, as in uffish thought he stood,

The Jabberwock, with eyes of flame,

Came whiffling through the tulgey wood,

And burbled as it came!

One, two! One, two! And through and through

The vorpal blade went snicker-snack!

He left it dead, and with its head

He went galumphing back.”

Lewis Carroll’s whimsical verse is an excellent example of onomatopoeia in children’s literature. Whiffling gives the readers an idea of the Jabberwock’s quick skidding through the woods, while burble creates a bubbling sound referring to the noise made by the creature’s movement. Snicker-snack brings to mind a slashing knife, while Galumphing sounds like a combination of gallop and thump – a movement peculiar to the Jabberwock. The readers’ imagination is fueled by the onomatopoeic words because they invite them to a thrilling adventure.

- From The Enormous Crocodile by Roald Dahl

“Suddenly there was a tremendous whooshing noise. It was Humpy-Rumpy the Hippopotamus. He came crashing and snorting out of the jungle. His head was down low and he was galloping at a terrific speed.”

Roald Dahl gives birth to new worlds with his wordplay. Notice how the phrase tremendous whooshing builds an image of Humpy-Rumpy’s heavy movement in the water, while the words crashing and snorting send an idea of how he sounds. Finally, galloping makes clear that Humpy-Rumpy is in a hurry. His clever use of onomatopoeia glues readers to every page.

Onomatopoeic Words in Poetry

Here’s an example of onomatopoeia in poetry.

- From Running Water by Lee Emmett

“water plops into pond

splish-splash downhill

warbling magpies in tree

trilling, melodic thrill”

Readers are transported to the scenic setting defined in the verse because of Lee Emmett’s use of onomatopoeia.

Related Reading: Alliteration – Creating Rhythm with Words

Onomatopoeia in Pop Culture

Superhero comics brim with onomatopoeic words, such as “Pow!” “Wham!” “Bham!” “Whiz!” and “Bang!” Comic writers even make up words like “Brrrt” and “Blap” which make the material more engaging.

After all, onomatopoeia is a figurative language unbounded by the semantic meaning of the word. It can be pulled from the actual sound of the thing being described, such as the “Whoosh!” of a waterfall.

Here are examples of onomatopoeia in branding and advertising.

- Pop Pop! (firecracker brand)

- “Snap, crackle, pop” (Rice Krispies cereal)

- Splash Island (Resort)

- Nestle Crunch

- Zoom Zoom Zoom (Mazda’s old slogan)

When to Use Onomatopoeia

Onomatopoeia injects emotion and energy into speech and writing. Use it to cut boredom and spark the imagination of your readers, but make sure to use it sparingly so as not to cause confusion. Also, because onomatopoeia often uses made-up words, think twice before using it in formal writing. You don’t want your research paper or dissertation to sound like a page from a comic, but you do want it to enhance your creative writing.

Thank you for reading. We hope it’s effective! Always feel free to revisit this page if you ever have any questions about onomatopoeia.

Check out some of our other blog posts or invest in your future with one of our self-study courses!

I often in children’s literature come across the rrrrrrrrrrrrS when a plane take off and the bumpity-bump when someone falls, etc.

and I am wondering if these are called with a specific term?

written sounds? transcribed sounds maybe?

asked Jul 19, 2013 at 13:09

3

Making a descriptive word out of the sound that something makes is called onomatopoeia:

Definition of ONOMATOPOEIA

1 : the naming of a thing or action by a

vocal imitation of the sound associated with it (as buzz, hiss)

2 : the use of words whose sound suggests the sense

The term is derived from the Greek words ὄνομα (onoma, name) and ποιεῖν (poiein, to make, to create). The same root as poet.

answered Jul 19, 2013 at 13:14

terdonterdon

20.9k18 gold badges82 silver badges123 bronze badges

10