Published August 27, 2021

That’s a big word, indeed!

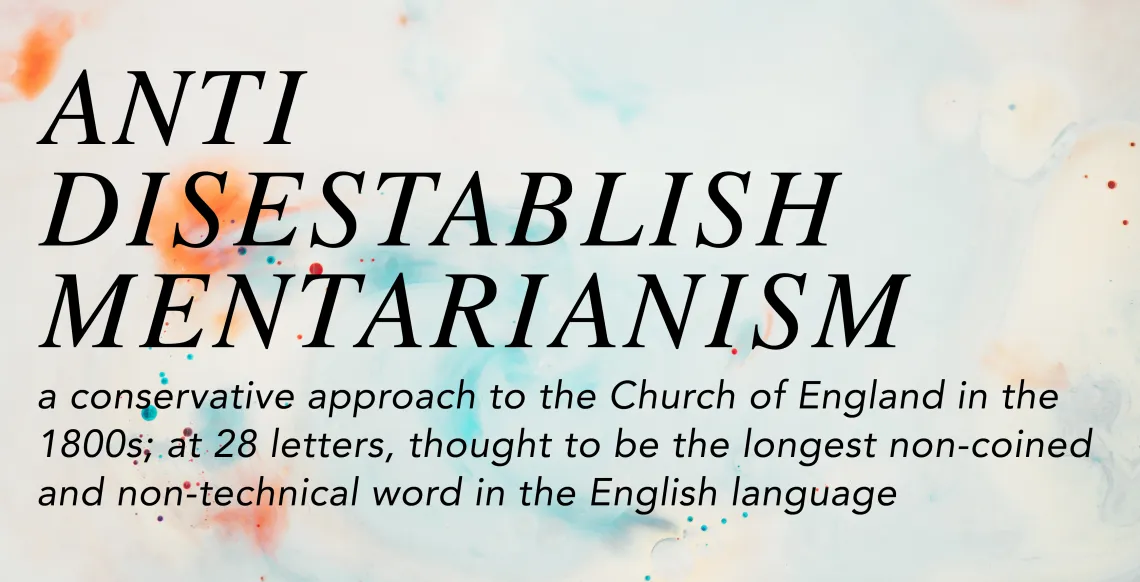

Most of the longest words in the English language are scientific and technical terms, like pneumonoultramicroscopicsilicovolcanoconiosis. But what are some long words that you might actually use one day, without having to become a microbiologist or something? We have gathered up over a dozen lengthy words that you might actually come across in the wild (or at least might actually want to use). If you are a sesquipedalian, or hope to become one one day, this slideshow is for you. And to find out what sesquipedalian means, read on.

For a look at the longest words you’re likely never to use, just click here.

sesquipedalian

Sesquipedalian [ ses-kwi-pi-dey-lee-uhn ] means “given to using long words.” It comes from Latin sesquipedālis meaning “measuring a foot and a half.”

- The professor was so sesquipedalian that he was often incomprehensible to his students.

The poet Horace, who is credited with coining the term sesquipedalian in Latin, used the word to warn young poets against using overly long and complicated words. Horace, of course, ironically did not take his own advice here to make his point—sesquipedalian itself is 14 letters long.

magnanimity

If someone asks you the meaning of a word, it’s important to have magnanimity [ mag-nuh–nim-i-tee ] about it. Magnanimity means “the quality of being generous in forgiving an insult or injury; free from petty resentfulness or vindictiveness.”

- We hoped that the Queen would show magnanimity and not sentence us to prison for the slight.

The related term magnanimous comes from the Latin for “great-souled.” Impressive.

Speaking of soul, experience the linguistic offerings of soul food by reading about its history and vocabulary.

decompensation

As we noted, many of the longest terms in English are scientific and or medical terms. Some of these are so complex, it is unlikely you will come across them unless you are in the field. Others you are more likely to encounter, like decompensation [ dee-kom-puhn-sey-shuhn ]. Decompensation means “the inability of a diseased heart to compensate for its defect.”

- I observed some symptoms of heart decompensation in the patient, including difficulty breathing and leg swelling.

While typically decompensation refers to the heart organ no longer working properly, it can also be used to refer to other organs or a psychological state.

counterrevolutionary

One way long words are created in the English language is by combining different word elements together to create a new word. That’s the case with counterrevolutionary, a combination of counter, revolution, and the suffix –ary. Counterrevolutionary means “opposing a revolution or revolutionary government.”

- After the revolutionaries came to power, the landed gentry began plotting a counterrevolutionary movement to regain control.

deinstitutionalization

Public policy is another domain where you will find especially long words. An example is deinstitutionalization, meaning “the release of institutionalized people, especially mental health patients, from an institution for placement and care in the community.”

- Many studies find that deinstitutionalization led to an increase in the number of mentally ill people in prison.

transcendentalism

Our next term, transcendentalism [ trans-sen-den-tl-iz-uhm ], also describes an American social experiment, of sorts, from the 19th century. Transcendentalism, or transcendental philosophy, is “a philosophy emphasizing the intuitive and spiritual above the empirical.”

- The group quickly embraced the principles of transcendentalism, including respect of nature and the importance of human effort.

The writers most closely associated with transcendentalism are Margaret Fuller, Ralph Waldo Emerson, and Henry Thoreau.

paleoanthropology

As you may have gathered, many academic terms are quite long. Even the names of some academic disciplines can get up there in length, like paleoanthropology [ pey-lee-oh-an-thruh–pol–uh-jee ]. Paleoanthropology is “the study of the origins and predecessors of the present human species, using fossils and other remains.”

- One of the most important aspects of paleoanthropology is determining whether ancient fossilized remains are Homo sapien or another hominin species.

Learn about other intriguing areas of study and profession with this article on 10 other “-ologist” professions.

psychophysiology

Another academic domain with a daunting name is psychophysiology, “the branch of physiology that deals with the interrelation of mental and physical phenomena.” Physiology is the branch of biology that deals with the functions and activities of living organisms.

- The medical students studied psychophysiology to learn how heart rate is related to a patient’s emotional state.

The psycho- part of the word psychophysiology is a combining form meaning “psyche” or “mind.”

countercyclical

Yet another area where you are likely to find long, complex terminology is in business and economics. That’s where we get the term countercyclical, “opposing the trend of a business or economic cycle; countervailing.” For example, reducing spending when the economy is doing well is an example of a countercyclical economic policy.

- Our panel of economic advisors recommends that we enact countercyclical infrastructure investment; when the economy is doing poorly, we should spend more on roads and bridges.

profligacy

Another lengthy term related to economics is profligacy [ prof-li-guh-see ], meaning “reckless extravagance” or “great abundance.”

- Budget hawks were once again warning that the government’s profligacy was going to increase the nation’s debt.

The word profligacy ultimately comes from the Latin prōflīgātus, meaning “degraded” or “debased.”

palingenesist

Philosophy and theology are also great sources for long words. One example is palingenesist [ pal-in-jen–uh-sist ], “a person who believes in a doctrine of rebirth or transmigration of souls.”

- The palingenesist Plutarch believed that the soul is reborn into another body after death, a theory known as metempsychosis.

(Bonus big word: metempsychosis!)

The original use of the word palingenesis, or the continual rebirth of the universe, dates back to ancient Greek philosophers known as the Stoics.

palimpsest

Another long word we can thank the Greeks for is palimpsest [ pal-imp-sest ], from Greek palímpsēstos, meaning “rubbed again.” The word palimpsest in English originally meant “a parchment or the like from which writing has been partially or completely erased to make room for another text.”

- Scholars use sophisticated equipment like optical scanners to read the remains of erased texts on Medieval palimpsests.

These days, palimpsest is most often used figuratively to mean “something that has a new layer, aspect, or appearance that builds on its past and allows us to see or perceive parts of this past.”

antepenultimate

Our third to the last word in this slideshow is, appropriately, antepenultimate [ an-tee-pi-nuhl-tuh-mit ]. Antepenultimate means “third from the end.”

- I was relieved to see that I was slated to be the antepenultimate speaker, so I would only have to wait for two more presentations after my own.

The word antepenultimate ultimately comes from the Latin antepaenultima meaning “the second (syllable) from the last.”

dodecaphonism

Some long words are just fun to say. That’s the case with dodecaphonism, “musical composition using the 12-tone technique.” Dodecaphonism [ doh-dek–uh-fuh-niz-uhm ] is a composition technique that uses all 12 notes of the chromatic scale and is atonal.

- The dodecaphonism in the composer’s work created a strange and unsettling feeling in the listeners.

amelioration

A particularly long word that we hope you find a lot of good use for is amelioration, “an act or instance of making better.”

- We were hopeful that the move would lead to an amelioration of our living conditions and a better quality of life overall.

Funnily enough, amelioration [ uh-meel-yuh-rey-shuhn ] and melioration mean the exact same thing.

This guest post is by Sarah Moore. Sarah is a freelance copywriter and the founder of New Leaf Writing, where she blogs about building quirky, high-paying, and meaningful copywriting careers. She is also a writing coach, helping others start their businesses and make the jump to full-time writing. She reviews books and offers tips o’ the trade on Instagram (@newleafwriter).

Have you ever used a word for years — like, maybe during your thesis defense or in a high-profile report for work — then realized one day that you had it totally wrong? Those big words you thought were making you look so erudite were, in fact, working against you. Turns out, coif is not the same as coiffure, and you never even realized it.

No one is immune from this, neither journalists nor poets, essayists nor novelists. The problem often stems from our natural inclination as writers to grab hold of an exciting new word and just run with it. Not only do we end up using big words just plain wrong, our enthusiasm leads to overuse as well.

By slowing down just a little bit, recognizing common pitfalls, and inserting some deliberate practice into your vocabulary usage, you can turn this trend around.

6 Big Word Sins You Can Learn to Avoid

We love those flashy mots, but in the pursuit of better craft, we often make our writing worse. Here are five common slipups writers make with big words:

Sin 1: Confusing Similar Words

You’ve probably come across the idea that only the first and last letters of a word are really important, while those between can be jumbled without losing meaning. This idea seems to contain the seeds of truth, which is bad for us writers who don’t parse vocab carefully enough.

At first glance, enervate and energize may look and sound the same, and seem to mean the same thing. Same with meretricious and meritorious. Unfortunately, these word pairs are opposites. To enervate is to drain energy; to energize is to add it. Meretricious means cheap or tawdry; meritorious means worthy or deserving of praise.

If you’re not careful to examine all of a word, you may end up using it wrong. Once you misapply it a few times, it gets cemented in your brain and will be hard to change. No Bueno.

Sin 2: Assuming You Know What Words Mean From Context

As writers, we’re used to absorbing vocabulary from what we read. That’s great, but only if you monitor the process. Otherwise, you can easily become confused. Take the above example of coif and coiffure. To coif is a verb; a coiffure is a hairstyle. You do the first; you have the second.

Luxuriant and luxurious are also frequently confused. Luxuriant doesn’t mean plush; it means lots of it. You have luxuriant hair; you get luxurious haircuts at expensive salons. If you’re not sure, follow my mom’s oft-repeated advice: Look it up.

Sin 3: Using the Word Multiple Times in Close Proximity

This … annoys me … so much. If you use a distinctive word too many times, I promise you readers will notice.

I’ll give you an example. Of late, fantasy authors have fallen in luuuuurve with the word “eldritch,” meaning bizarre or sinister. Now, this is a great word, but it’s not good enough to justify using more than once in a novel. There are other words for “weird and sinister,” starting with either “weird” or “sinister.” Just sayin’.

This can occur with phrases too. I love the Throne of Glass series, but my pet peeve is Sarah J. Maas’ use of “killing fields.” Yes, it’s a cool, if dark, term. But it’s so distinctive that at ten uses per novel, each new reference begins to grate. No matter how excited you are, keep your shiny new word to one instance.

Sin 4: Using Too Many DIFFERENT Words in Close Proximity

Like the above advice, readers notice when your prose or copy is suddenly crammed with four-syllable words. Keeping the big guys to a minimum is a good way to make those you do use stand out, so stick with one or two per page, at a maximum.

If it’s a word most people don’t know (eyeballing you, “eldritch”), give it even more space. Otherwise your readers will find your writing taxing, and they will get tired of it. You’re not James Joyce. Sorry.

Sin 5: Integrating More Than One Word into Your Vocab at a Time

I’m stoked you like the great authors. I do too. But while reading classic lit is a great way to expand our vocab, it’s also a great way to cram our brains full of words with which we’re only half conversant … and biff it in that thesis defense.

When you read a new word, dog-ear that page or write it down. Don’t just absorb it and conclude you “know” what it means. Then look words up carefully and practice (below) to be sure you know how to use them. If you come across many new words in a short amount of time, write them down in a document and reference it when you have some free writing time.

Sin 6: Using the Word in Dialogue When It’s Out of Character

The occasional professor or lair-bound scientist can fairly employ flowery phrasing, but chances are good your medieval heroines and subversive Nazi soldiers don’t have overflowing vocabularies. You can use that fancy five-syllable exclamation, but they probably won’t. Of course, you know your characters better than anyone else, but for the most part, you should keep their language simpler than your prose.

Choose Your Words

Phew, that was a lot of don’ts.

Luckily there is also a DO! Do use deliberate practice to improve your command of new words you stumble across. If you haven’t stumbled in a while, feel free to head to your favorite writing blog or dictionary, both of which commonly suggest new words to use. Stuck for ideas? Check out some of our favorite big words here.

When you encounter a new word you love the sound of, look it up and absorb its meaning. To deepen your understanding, check out a few examples of it in use — dictionary and encyclopedia sites are a handy way to do this, as they often offer sample sentences.

Big and uncommon words can be the perfect things to make your prose sizzle. By avoiding these egregious sins, you’ll ensure each one packs a punch. Don’t stop using your fancy vocabulary! Just make sure it’s working for you, not against you.

What’s your favorite uncommon word to use in your writing? What’s a word you often see overused or misused? Let us know in the comments.

PRACTICE

Now it’s your turn: Find a word you’re unfamiliar with. Flip through a dictionary, or pick one off this list. Then, take fifteen minutes to write three paragraphs, using the new word once in each.

Post your practice in the comments section so we can all see your work and boost our vocabulary skills along with you! And if you post, be sure to leave feedback for your fellow writers!

-

#1

What’s an adjective for someone that uses $10 words when a 50 cent word will do nicely? I’m trying to describe how in academic articles on political theory that there are so many big words that the meaning and purpose of the article gets lost.

-

#3

A compulsive polysyllabricator?

.

.

-

#6

sesquipedalian, adjective:

1. Given to or characterized by the use of long words.

2. Long and ponderous; having many syllables.

Oops, post crossing!

-

#7

Doodlebugger and Vanda

I think this is a wonderful word (which I admit to never having heard of) and one which I shall add to my vocabulary.

(My late, dear old father, whenever I used a long word, used to say, «Where did you find that word? Hanging on the bathroom door? )

He would have had a lot to say about your offering.

Thanks,

LRV

-

#8

Ah yes— that’s the standard. Couldn’t think of it, so I coined something.

.

.

-

#9

Nice to see ‘sesquipedalian’ getting so much respect. I suggested it in a similar thread a few months back and it attracted no attention. A great word for which we have Horace to thank.

-

#10

Hyperarticulate:

hi-per-ar-TIC-you-lit

-

#11

I don’t use big words. I’m hippopotomonstrosesquippedaliophobic.

-

#12

Hi Mary & welcome to the forums!

There’s also pleonastic but this is the use of more words than necessary (not necessarily the size of the words).

Also: ostentatious.

Don’t know why, but sesquipedalian sounds like some kind of early primate…

-

#14

… and a very big welcome to maryp3177

Sorry for not noticing that this was your first post (fortunately french4beth and panjandrum did!). Welcome!

I’m trying to describe how in academic articles on political theory that there are so many big words that the meaning and purpose of the article gets lost.

Academics often write in purple prose, or at least have the occasional purple passage in their articles.

-

#15

Don’t know why, but sesquipedalian sounds like some kind of early primate…

How many feet would it have? Bi-, tri-…. sesqui. Or would sesqui refer to the kind of legs or feet?

-

#16

Yes, Mary, welcome to the forums.!

An excellent first post if I may say so.

Kind regards,

LRV

-

#17

«sesquipedalian»… I did not know that word either, and it is a beauty! Excellent, excellent…

-

#18

I found a few to add.

macroverbumsciolist

1) a person who is ignorant of large words

2) a person who pretends to know a word, then secretly refers to a dictionary

grandiloquent

pompous or extravagant in language, style, or manner, esp. in a way that is intended to impress

fustian

pompous or pretentious speech or writing

LRV, when I was younger and used a big word, my dad used to say, «You do and you’ll clean it up!»

-

#19

How many feet would it have? Bi-, tri-…. sesqui. Or would sesqui refer to the kind of legs or feet?

![Confused :confused: :confused:]()

Almost certainly the kind of feet, Lola. Really, really long ones which allowed it to ski across snowy wastes as the first ice age approached.

LRV

-

#20

Another couple of lovely words:

bombastic — grandiose but with little meaning, ostentatiously lofty in style

turgid — (of language or style) tediously pompous or bombastic.

Edit: I love your explanation of sesqui, LRV!

-

#21

How many feet would it have? Bi-, tri-…. sesqui. Or would sesqui refer to the kind of legs or feet?

![Confused :confused: :confused:]()

Horace’s phrase was verba sesquipedalia which would mean «words a foot and a half long’

Like ‘sesquicentennial’ means the 150th anniversary.

-

#22

How many feet would it have? Bi-, tri-…. sesqui. Or would sesqui refer to the kind of legs or feet?

![Confused :confused: :confused:]()

Yes, it refers to the beast’s ability to move its manifold feet sequentially

When you’ve got 20+ it takes some concentration to get the rhythm right, I imagine.

-

#23

Yes, it refers to the beast’s ability to move its manifold feet sequentially

When you’ve got 20+ it takes some concentration to get the rhythm right, I imagine.

Millipedes seem to do it well (she said, continuing to go off topic).

«This year is the sesquicentennial of my stone-built cottage», she added (truthfully) to get back on topic.

LRV

-

#24

Prolix is a good word, but it refers to the quantity of words and their obfuscatory characteristics rather than their length.

-

#25

What a great selection of words, especially that sesqui… thing! I’d never remember how to write it.

-

#26

Prolix is a good word, but it refers to the quantity of words and their obfuscatory characteristics rather than their length.

Obfuscatory is a good word, too: very good indeed!

-

#27

I agree with «grandiloquent», seems accurate to me.

-

#28

Is there an English word for «big words»

….and a word for someone who chooses a big word when they could just as eaisly use a simple word.

thanks for your suggestions, scotu

KHS

Senior Member

-

#29

Some possibilities:

complex word, multisyllabic word, difficult word, obfuscatory word

Karen

-

#30

Is there an English word for «big words»

….and a word for someone who chooses a big word when they could just as eaisly use a simple word.thanks for your suggestions, scotu

In one sense, polysyllabic words are big or long words, although I think that you’re looking for another sense, perhaps something along the lines of highfalutin or verbose language or speech.

You could call somebody who uses such speech pompous or a pedant and maybe a logophile, although that’s somebody who loves all words, not just big ones.

-

#31

One who chooses to use them might be termed sesquipedalian.

-

#32

Is there an English word for «big words»

….and a word for someone who chooses a big word when they could just as eaisly use a simple word.thanks for your suggestions, scotu

The standard BE expression is long words — complicated, latinate, difficult: all these things are suggested by the adjective long.

-

#33

Thank you all for the suggestions.

Jefe, I like your word so much I’m going to use it in my signature. Thanks.

edit: and it lead me to another interesting word: hippopotomonstrosesquipedaliophobia = Fear of big words

-

#34

hippopotomonstrosesquipedaliophobia = Fear of big words

I thought it was hippopotomonstrosesquippedaliophobia .

-

#35

I thought it was hippopotomonstrosesquippedaliophobia

.

wikidictionary suggests that hippopotomonstrosesquippedaliophobia is a deliberate mispelling just to make the word longer.

-

#36

wikidictionary suggests that hippopotomonstrosesquippedaliophobia is a deliberate mispelling just to make the word longer.

-

#39

Verbose means to use more words than are necessary to describe a concept that can be expressed with fewer words or in less space or less time, particularly when the concept can be expressed more simply.

As an example, see the preceding sentence. Verbose doesn’t have anything to do with using big words.

In view of some of the words offered on this thread, I wonder if anybody could use them without being guilty of that which they are describing.

-

#40

I don’t think so. Verbose applies to using more words than necessary and has nothing to to do specifically with long words.

-

#41

Yeah, I knew that I thought it might be good to describe the overall phenomenon of the piece of writing. Just an idea. I should have explained myself

-

#42

polysyllabricator The word you’ve entered isn’t in the dictionary. Click on a spelling suggestion below or try again using the search bar above.

-

#43

Yes, but sesquipedalian is in the dictionary. (I think polysyllabricator was an invention of Foxfirebrand’s.)

-

#44

-He likes using big/fancy words.

-high-flown rhetoric

-stilted style of writing

The biggest word in the English language is 189,819 letters long, and takes three hours to pronounce! More commonly used big words are several syllables long, and often make people feel smart when they say them out loud. Somewhat ironically, however, study after study has shown that using big words usually makes people sound dumb.

There is a time and a place for big words. If you’re a writer, you might want to be careful about how often you invoke long words that no one has ever heard of before. Mark Twain has a few good quotes about why writers should be economical and precise:

“Don’t use a five-dollar word when a fifty-cent word will do.”

“The difference between the almost right word and the right word is really a large matter – it’s the difference between the lightning bug and the lightning.”

With that said, below is a list of some of the biggest words in the English language, which you can choose to ignore, or insert into your writing and vocabulary. Remember, sometimes, a big word works better. Try to insert a new word into your vocabulary every day until you’re able to use them naturally, without thinking about it. Here are some big words that you can use to sound smart around your family and friends, along with their meaning so you use them in the correct way:

1. Abstentious

Self-restraining; also the longest word in the English language to use all five vowels in order once

2. Accoutrements

trappings, esp. related to apparel

3. Acumen — ability, skill

4. Anachronistic — a story that didn’t actually happen

5. Anagnorisis — the moment in a story when the main character realizes something that leads to a resolution

6. Anomalist — difficult to classify

8. Apropos — appropriate

9. Arid — dry

10. Assiduous — painstaking; taking great care through hard work

11. Auspicious — signaling a positive future

Big Words (B-C)

12. Behoove — something that is a personal duty

13. Bellwether — the first sheep in a flock, wearing a bell around its neck

14. Callipygian — having large, round, succulent buttocks

15. Circumlocution —the act of using too many words

16. Consanguineous — of the same blood or same ancestor

17. Conviviality — friendliness

18. Coruscant — sparkling

19. Cuddlesome — cuddly

20. Cupidity — greed

21. Cwtch — from the Welsh word for “hiding place”; the longest word in English to be entirely composed of consonants

22. Cynosure — center of attention

Big Words (D)

23. Deleterious — harmful

24. Desideratum — something needed or wanted

Big Words (E)

26. Enervating — exhausting

27. Equanimity — level-headedness

28. Euouae — a medieval musical term; the longest word in a major dictionary entirely composed of vowels

29. Excogitate — to plan

Big Words (F)

31. Florid — red and inflamed

32. Fortuitous — lucky

33. Frugal — cheap, thrifty

Big Words (G-M)

34. Gasconading — bragging

35. Grandiloquent — verbally pompous

36. Hackneyed — clichéd

37. Honorificabilitudinitatibus — an extremely long-winded way to say “honorable”; at 27 letters, the longest word in the work of William Shakespeare; also the longest word in the English language featuring alternating consonants and vowels

38. Idiosyncratic — peculiar

39. Indubitably — without a doubt

40. Ivoriate — to cover in ivory

41. Lopadotemachoselachogaleokranioleipsanodrimhypo…pterygon — (ellipsis used because the word is 182 letters long) an elaborate fricassee; coined word that appeared in the play Assemblywomen by Aristophanes

42. Methionylthreonylthreonylglutaminylalanyl…isoleucine … the chemical name for titin, the largest known protein; ellipsis used because at 189,819 letters, it’s the largest known word and takes over three hours to pronounce

43. Milieu — environment

Big Words (N-P)

44. Nidificate — to build a nest

45. Nonchalant — carefree and unbothered

46. Osculator — one who loves or is loved

47. Paradigm — model

48. Parastratiosphecomyiastratiosphecomyiodes — a species of fly native to Thailand

49. Parsimonious — cheap

50. Penultimate — second to last

51. Perfidious — treacherous

52. Perspicacious — perceptive

54. Proficuous — profitable

55. Predilection — preference

56. Pseudopseudohypoparathyroidism — an inherited thyroid disorder

57. Psychotomimetic – inducing psychotic alteration of behavior and personality

Big Words (Q-Z)

58. Querulous — fussy

59 Rancorous — bitter and argumentative

60. Remunerative — lucrative

61. Rotavator — a soil tiller; at 9 letters, the longest palindromic word in the English language (i.e., it’s spelled the same way backwards)

62. Saxicolous — something that lives on rocks

63. Sesquipedalian — involving long words, just like this article

64. Splendiferous — wonderful

65. Squirrelled — put away; the longest one-syllable word in the English language

67. Supercilious — when a person is arrogant

68. Synergy — extra energy generated by cooperation

69. Unencumbered — free

70. Unparagoned — without equal

71. Winebibber — an alcoholic

If you’re someone who loves the English Language as much as I do, it can be challenging to know how to create pieces of literature that are both easy to read and sophisticated in their vocabulary. Don’t worry! It’s definitely a good thing that you’re looking into the language more than most. Grammar fascinates you? Discovering new words and the etymology behind them envigorates you? Excellent! I totally understand you! Languages can be exciting – especially when you realise that you can never know every single word. There will always be growing-room, and space to learn and make yourself seem smarter than before.

So let’s imagine that you’ve been reading avidly and regularly, and recently you stumbled across a particularly fascinating word. You get it from context, look it up in a dictionary, ask someone, or a mixture of a few different methods to discover its definition. Now, you’re pretty confident that you know what the word means and how to use it. Great! I wouldn’t blame you if you were eager to jump straight into your work and insert the new vocabulary in as many places as you see fit. After all, as someone who studies a few different foreign languages, I’m more aware than most that the best way to consolidate your understanding of a word and make sure that it sticks in your head is to use it. But should you just use it without thinking about the effect it’s creating upon your work? Certainly not!

You’re probably thinking “what do you mean? Of course, I should use the word if I know how! What else is there to think about?” and my answer to that is a lot. There’s a lot to think about. Way more than you’d imagine – and it’s whether or not you think about the effect your words are having upon your story that can make or break you as a writer.

If you have ventured into the world of my recommendations for you, you’ll have probably realised that Philip Pullman subscribes to the same idea in his book on writing, Dæmon Voices. He calls himself a “vulgar” writer, suggesting that he cares very little for flowery prose and verbose sentences. That’s not to say that he is incapable or reluctant to use less common vocabulary where he sees fit. It’s about making sure that his work is accessible and easy to read so that he doesn’t lose the message or his audience somewhere along the way.

You see, Western society was very class-based in the past – and to some extent, it still is. One of the ways that these class differences are shown clearly and easily is through the “eloquence” of language. The upper-class folk among us will use words that we think are solely reserved for high tea in an old Victorian novel, particularly when they’re around us lowly “peasants”, and they want to remind us of what our “place” is. I’m sure you’ve either been on the giving or the receiving end of patronising remarks thrown around using big words intended to make the victim feel lesser and stupid. I find that I am also guilty of subconsciously turning to big words when I’m debating with someone who doesn’t seem to understand basic common sense. It’s a stuck-up, educated person’s way of saying “I know way more than you do. You’re beneath me.” It’s bad, I know. I need to work on it.

So why would you want to do that to your readers? Why would you want your readers to feel like they are stupid when reading your book? It’s really like filmmaking, to some extent: when an audience is forced to draw their attention to the camera due to terrible angles or movements, they lose all sense of immersion and stop caring as much about the characters and plot as a result. Think of your words at the camera in a piece of writing. If your reader is spending too much time wondering what certain words mean or wondering why you’re belittling or patronising them through your persistent use of big words, they’re not really going to get the chance to care too much about the actual events. That screws you over.

Of course, there are examples of when this kind of thing works for a writer. There are some beautifully written novels that are largely flowery and padded out with the pretentious vocab we usually avoid like the plague. It can work. It’s just a lot more difficult to do in a way that works well. This is especially true when you realise that a lot of more flowery pieces of writing came from times when it was more common to actually speak like that. It’s a lot easier to get pretentious vocabulary on point when you have practice with it in your every-day speech, and the English Language, along with practically every other language under the sun, has evolved massively over the years. We just don’t talk that way anymore. It comes across much more natural than it would for us today!

There are, of course, times when it can come in useful today. Take politicians, for example. You’ve probably noticed that they often enjoy dumbfounding anyone who asks them questions by overusing jargon and making the audience feel stupid. It’s an interesting tactic that enables them to hide the fact that they have no clue what they’re talking about behind words that make them sound like they’re in control. To paraphrase Pullman, complex vocab conceals and hides true intent or meaning. One of the reasons many people I know feel particularly apathetic about politics is because politicians make it seem like politics is above them, inaccessible to the “common people”, something that we can only pretend to understand. It’s a way of making sure they keep control: if they were too transparent with their language, we would quickly catch on to the shady crap that they’re up to and make sure we don’t vote for them again. They would have to make sure they’re actually doing well, God forbid!

If you’ve read Nineteen Eighty-Four by George Orwell, you’ll understand this a little better than most. Orwell doesn’t try to hide things behind words we don’t understand, but the Party in the story takes this to a whole new level. Newspeak is a way for the government to control how their people interact with each other. If we don’t have complicated words to hide behind, we’d have to be pretty clear about whether we liked something or not, whether we agreed with the Party or not. Good or Ungood. Direct opposites. Nothing to hide. It’s also a Communist regime: people are supposed to be equals – comrades – so making sure they all have access to the same language stops that class divide we were talking about.

Now you’re probably thinking back over your own writing and wondering how many complicated words you need to remove. I mean, what is the point of them anyway if you can’t use them in your own work without making it less accessible and more confusing? Well, I’m here to throw another spanner in the works and make your job just a little more difficult: you shouldn’t be dumbing yourself down for your audience either. That’s just as patronising (if not more so) than including pretension in the first place. Unless you’re writing for very tiny children, you shouldn’t assume that someone can’t figure out a word from context or look it up every now and then. In fact, my biggest problem with the US name change of the first Harry Potter is that it implies that Americans are incapable of facing a difficult word every now and then. British children probably didn’t know what a “Philosopher” was either. We just looked it up or asked.

Also, bear in mind that a lot of people – probably yourself included – read widely partly to broaden their vocabulary. Why would you deprive your readers of a chance to see big words used properly and appropriately? I don’t know about you, but personally, I’d never read a book that I felt didn’t challenge me in some way or another. This can be done by giving me an exciting new premise or storyline that hasn’t been done before; making me look differently at characters that I would usually come to quick assumptions about; challenging my general expectations of the story as a whole; or – surprise, surprise – giving me new words to use and understand. It is our duty to ensure that we make our readers think… just not too hard.

Big words can be an excellent way to explain and describe complicated ideas. Sometimes they’re much more effective and quick to write than the thing they’re explaining. The only thing stopping them from being easy to understand and fun to learn is the writer. Well… maybe the reader a little bit. I mean, you can’t teach someone who doesn’t want to learn, after all. However, most of the time, it’s your own attitude towards these words, particularly treating them like they’re hard on purpose and not supposed to be understood by the lowly peasants, that creates the huge barrier between writer and reader.

So how do you strike that perfect balance and make sure that you’re not overloading your audience? Well, I’m not going to pretend that it isn’t tricky. Here are some tips, though, that I’m sure will help you:

Remember that your readers aren’t stupid

I mean, maybe one or two of them are… but as a whole, don’t assume that they’re going to be idiotic. Not only does that give you a really patronising attitude towards them, but it also shows that you don’t really have very high hopes for your own writing. I mean, why would you even want to assume that the people who read the things you produce are going to be stupid? It makes it seem like you don’t think your writing is very good. Aim for the best and expect the best, as it will keep the standard of your work high. If you assume that your writing is going to be read by intelligent readers, it will make you write something worthy of intelligent readers, which will, in turn, be more likely to attract them. As soon as you assume that your audience is full of morons, you’re going to have an excuse to drop the quality. Just as with my post on exposition, you don’t want to risk spoon-feeding your audience too much because you think they’re idiots.

Sprinkle some big words in among the easy words

It’s like the whole “do you want some tea with that sugar” remark. Imagine that your big words are the lumps of sugar: you don’t want a brown mess of sugar with some tea poured over the top. What you should do is make sure that the majority of the words you use are ones that you’re pretty sure your target audience should understand. Sweeten the work with big words. Remember: too much sugar is bad for you.

The benefit of doing things that way is that the reader has a chance to understand what you mean through context. Basically, you add a single new word in every now and then, surrounded by easier ones. That way, your readers can say to themselves: “I understand the rest of the sentence. I guess this word must mean…”. It’s a much more efficient way for people to learn new vocabulary without drawing attention away from the actual narrative.

Remember the tone

You see, when I’m writing these blog posts, I make sure I keep the tone as conversational as possible. Yes, I frequently use words you may not have heard of before… or at least very often. If I’m not careful, that could make you run a mile and never look at my advice again! So, I make sure that my post remains accessible by keeping the tone as consistent and nice as possible. Why does this help? Well, imagine I’m speaking in a language you don’t understand at all. I’m trying to tell you something quite simple, but the language barrier is there, so you have no clue what I’m saying. How would I convey my message to you in a way that transcends language barriers? (Cheeky me, I slipped in the word “transcend” in a way that can be understood from context). Well, we use a few basic things: facial expressions, gestures, common words, and tone. At least when I’ve got that down, you know roughly what I’m trying to say even when a word goes over your head. The same is true of your writing. If you are using complex vocabulary, make sure that all your easier words clearly show what kind of tone you’re trying to capture. Then, your reader will at least know what sort of thing you’re saying.

Make sure you know exactly what the word means

When I say this, I mean properly. Like, completely understand it. No mistakes. If you’re not 100% sure of what a word means – or you only think you know what it actually means – you’re going to simply end up confusing the reader even more. They may have already come across it, or come across it in the future, in a slightly different context which makes them feel out of their depth, unsure or nervous when it comes to using it themselves with ease. You don’t want the reader to feel nervous about the writing! They should feel nervous about actual plot points! If you’re using a whole arsenal of complicated words and throwing them around as if they mean nothing, it can seem like a complete bombardment.

Ask yourself why

This is more important than most people believe. As with most of the things we’ve discussed before, the most important thing to do when deciding to include, or not to include, something in your writing is to make sure that you’ve asked yourself why. Why have you decided to use the more complex synonym instead of it’s more straight-forward counterpart? Does it add something to the story? Sometimes, you’ll actually find that the definition provides more description and intrigue than the single-word, complex jargon. Sometimes it’s better to say “the thought of spiders made him shudder” as opposed to simply saying “he had arachnophobia”. It comes with practice, but eventually, you’ll be able to tell when you should use each one. It actually ties largely into the exposition post, as it involves showing what’s happening using more simple vocabulary, as opposed to telling the audience using a convoluted term.

So yes, maybe it is time to look back over your own writing. Have a long, hard think about the quality. Ask yourself whether you’re being needlessly pretentious and see if you can find ways to resolve that. The most important part of your writing is that the actual prose should be easy enough to understand, regardless of how intricate your plot details are. Think a little about the importance of choosing the right words, because most people seem to forget how essential that is. Above all, make sure that you have as much fun with it as you hope the reader will have.

Happy writing!