Create a document in Word

With Word on your PC, Mac, or mobile device, you can:

-

Create documents from scratch, or a template.

-

Add text, images, art, and videos.

-

Research a topic and find credible sources.

-

Access your documents from a computer, tablet, or phone with OneDrive.

-

Share your documents and work with others.

-

Track and review changes.

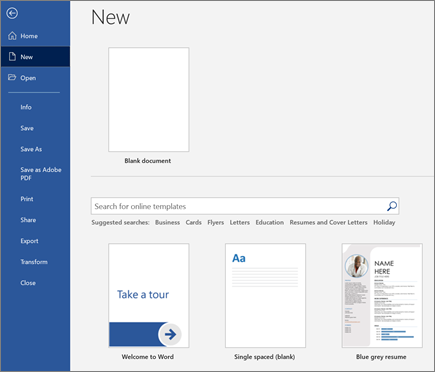

Create a document

-

On the File tab, click New.

-

In the Search for online templates box, enter the type of document you want to create and press ENTER.

Tip: To start from scratch, select Blank document. Or, for practice using Word features, try a learning guide like Welcome to Word, Insert your first table of contents, and more.

Add and format text

-

Place the cursor and type some text.

-

To format, select the text and then select an option: Bold, Italic, Bullets, Numbering, and more.

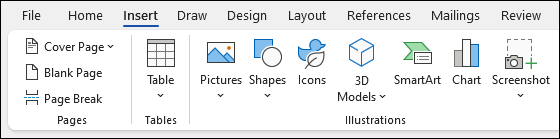

Add Pictures, Shapes, SmartArt, Chart, and more

-

Select the Insert tab.

-

Select what you want to add:

-

Tables — select Table, hover over the size you want, and select it.

-

Pictures — select Pictures, browse for pictures from your computer, select a stock image, or even search Bing.

Note:

Older versions of Word may have Online Pictures on the ribbon next to Pictures. -

Shapes — select Shapes, and choose a shape from the drop-down.

-

Icons — select Icons, pick the one you want, and select Insert.

-

3D Models — select 3D Models, choose from a file or online source, go to the image you want, and select Insert.

-

SmartArt — select SmartArt, choose a SmartArt Graphic, and select OK.

-

Chart — select Chart, select the chart you want, and select OK.

-

Screenshot — select Screenshot and select one from the drop-down.

-

Next:

Save your document to OneDrive in Word

Need more help?

Want more options?

Explore subscription benefits, browse training courses, learn how to secure your device, and more.

Communities help you ask and answer questions, give feedback, and hear from experts with rich knowledge.

Find solutions to common problems or get help from a support agent.

Microsoft Word is a word processor developed by Microsoft. It was first released on October 25, 1983,[9] under the name Multi-Tool Word for Xenix systems.[10][11][12] Subsequent versions were later written for several other platforms including: IBM PCs running DOS (1983), Apple Macintosh running the Classic Mac OS (1985), AT&T UNIX PC (1985), Atari ST (1988), OS/2 (1989), Microsoft Windows (1989), SCO Unix (1990), macOS (2001), Web browsers (2010), iOS (2014) and Android (2015). Using Wine, versions of Microsoft Word before 2013 can be run on Linux.

|

|

Microsoft Office 365 version of Microsoft Word, with the new redesign applied |

|

| Developer(s) | Microsoft |

|---|---|

| Initial release | October 25, 1983; 39 years ago (as Multi-Tool Word) |

| Stable release |

2209 (16.0.15629.20208) |

| Repository | none |

| Written in | C++ (back-end)[2] |

| Operating system |

|

| Platform | IA-32, x64, ARM, ARM64 |

| Type | Word processor |

| License | Trialware |

| Website | microsoft.com/en-us/microsoft-365/word |

Word for Mac running on macOS Ventura (13.2) |

|

| Developer(s) | Microsoft |

|---|---|

| Stable release |

16.64 (Build 22081401) |

| Repository | none |

| Written in | C++ (back-end), Objective-C (API/UI)[2] |

| Operating system | macOS |

| Type | Word processor |

| License | Proprietary software plus services |

| Website | products.office.com/word |

Screenshot of Microsoft Word for Android 13 |

|

| Original author(s) | Microsoft Corporation |

|---|---|

| Developer(s) | Microsoft Corporation |

| Initial release | January 29, 2015; 8 years ago[5] |

| Stable release |

16.0.15427.20090 |

| Repository | none |

| Operating system | Android Pie and later |

| License | Proprietary commercial software |

| Website | products.office.com/word |

| Developer(s) | Microsoft Corporation |

|---|---|

| Initial release | March 27, 2014; 9 years ago[7] |

| Stable release |

2.63.2 |

| Repository | none |

| Operating system | iOS 14 or later IPadOS 14 or later |

| License | Proprietary commercial software |

| Website | products.office.com/word |

| Developer(s) | Microsoft |

|---|---|

| Repository | none |

| Operating system | Windows 10 and later, Windows 10 Mobile |

| Type | Word processor |

| License | Freemium |

| Website | www.microsoft.com/store/productId/9WZDNCRFJB9S |

Commercial versions of Word are licensed as a standalone product or as a component of Microsoft Office suite of software, which can be purchased either with a perpetual license or as part of a Microsoft 365 subscription.

HistoryEdit

OriginsEdit

In 1981, Microsoft hired Charles Simonyi, the primary developer of Bravo, the first GUI word processor, which was developed at Xerox PARC.[13] Simonyi started work on a word processor called Multi-Tool Word and soon hired Richard Brodie, a former Xerox intern, who became the primary software engineer.[13][14][15]

Microsoft announced Multi-Tool Word for Xenix[13] and MS-DOS in 1983.[16] Its name was soon simplified to Microsoft Word.[10] Free demonstration copies of the application were bundled with the November 1983 issue of PC World, making it the first to be distributed on-disk with a magazine.[10][17] That year Microsoft demonstrated Word running on Windows.[18]

Unlike most MS-DOS programs at the time, Microsoft Word was designed to be used with a mouse.[16] Advertisements depicted the Microsoft Mouse and described Word as a WYSIWYG, windowed word processor with the ability to undo and display bold, italic, and underlined text,[19] although it could not render fonts.[10] It was not initially popular, since its user interface was different from the leading word processor at the time, WordStar.[20] However, Microsoft steadily improved the product, releasing versions 2.0 through 5.0 over the next six years. In 1985, Microsoft ported Word to the classic Mac OS (known as Macintosh System Software at the time). This was made easier by Word for DOS having been designed for use with high-resolution displays and laser printers, even though none were yet available to the general public.[21] It was also notable for its very fast cut-and-paste function and unlimited number of undo operations, which are due to its usage of the piece table data structure.[22]

Following the precedents of LisaWrite and MacWrite, Word for Mac OS added true WYSIWYG features. It fulfilled a need for a word processor that was more capable than MacWrite.[23] After its release, Word for Mac OS’s sales were higher than its MS-DOS counterpart for at least four years.[13]

The second release of Word for Mac OS, shipped in 1987, was named Word 3.0 to synchronize its version number with Word for DOS; this was Microsoft’s first attempt to synchronize version numbers across platforms. Word 3.0 included numerous internal enhancements and new features, including the first implementation of the Rich Text Format (RTF) specification, but was plagued with bugs. Within a few months, Word 3.0 was superseded by a more stable Word 3.01, which was mailed free to all registered users of 3.0.[21] After MacWrite Pro was discontinued in the mid-1990s, Word for Mac OS never had any serious rivals. Word 5.1 for Mac OS, released in 1992, was a very popular word processor owing to its elegance, relative ease of use, and feature set. Many users say it is the best version of Word for Mac OS ever created.[21][24]

In 1986, an agreement between Atari and Microsoft brought Word to the Atari ST[25] under the name Microsoft Write. The Atari ST version was a port of Word 1.05 for the Mac OS[26][27] and was never updated.

The first version of Word for Windows was released in 1989. With the release of Windows 3.0 the following year, sales began to pick up and Microsoft soon became the market leader for word processors for IBM PC-compatible computers.[13] In 1991, Microsoft capitalized on Word for Windows’ increasing popularity by releasing a version of Word for DOS, version 5.5, that replaced its unique user interface with an interface similar to a Windows application.[28][29] When Microsoft became aware of the Year 2000 problem, it made Microsoft Word 5.5 for DOS available for free downloads. As of February 2021, it is still available for download from Microsoft’s website.[30]

In 1991, Microsoft embarked on a project code-named Pyramid to completely rewrite Microsoft Word from the ground up. Both the Windows and Mac OS versions would start from the same code base. It was abandoned when it was determined that it would take the development team too long to rewrite and then catch up with all the new capabilities that could have been added at the same time without a rewrite. Instead, the next versions of Word for Windows and Mac OS, dubbed version 6.0, both started from the code base of Word for Windows 2.0.[24]

With the release of Word 6.0 in 1993, Microsoft again attempted to synchronize the version numbers and coordinate product naming across platforms, this time across DOS, Mac OS, and Windows (this was the last version of Word for DOS). It introduced AutoCorrect, which automatically fixed certain typing errors, and AutoFormat, which could reformat many parts of a document at once. While the Windows version received favorable reviews (e.g., from InfoWorld[31]), the Mac OS version was widely derided. Many accused it of being slow, clumsy, and memory intensive, and its user interface differed significantly from Word 5.1.[24] In response to user requests, Microsoft offered Word 5 again, after it had been discontinued.[32] Subsequent versions of Word for macOS are no longer direct ports of Word for Windows, instead featuring a mixture of ported code and native code.

Word for WindowsEdit

Word for Windows is available stand-alone or as part of the Microsoft Office suite. Word contains rudimentary desktop publishing capabilities and is the most widely used word processing program on the market. Word files are commonly used as the format for sending text documents via e-mail because almost every user with a computer can read a Word document by using the Word application, a Word viewer or a word processor that imports the Word format (see Microsoft Word Viewer).

Word 6 for Windows NT was the first 32-bit version of the product,[33] released with Microsoft Office for Windows NT around the same time as Windows 95. It was a straightforward port of Word 6.0. Starting with Word 95, each release of Word was named after the year of its release, instead of its version number.[34]

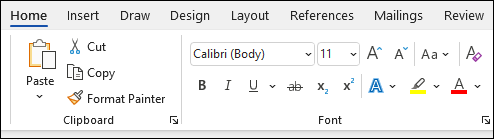

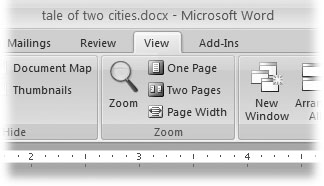

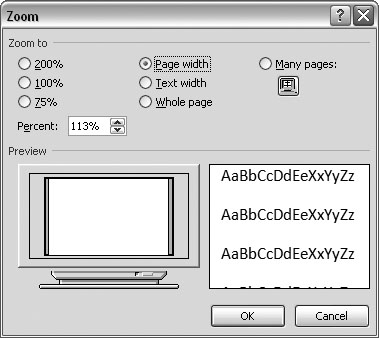

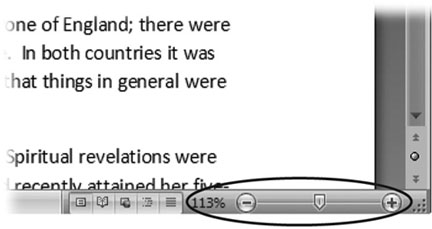

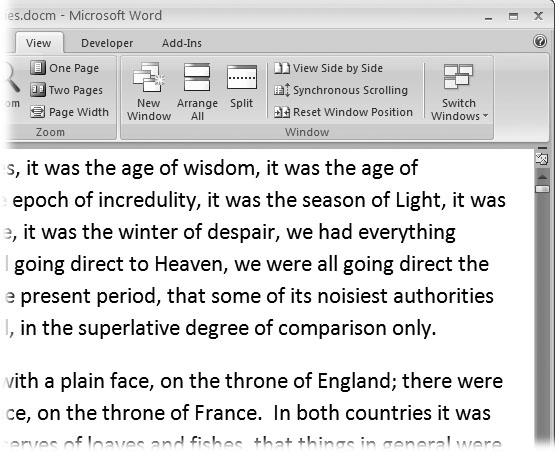

Word 2007 introduced a redesigned user interface that emphasized the most common controls, dividing them into tabs, and adding specific options depending on the context, such as selecting an image or editing a table.[35] This user interface, called Ribbon, was included in Excel, PowerPoint and Access 2007, and would be later introduced to other Office applications with Office 2010 and Windows applications such as Paint and WordPad with Windows 7, respectively.[36]

The redesigned interface also includes a toolbar that appears when selecting text, with options for formatting included.[37]

Word 2007 also included the option to save documents as Adobe Acrobat or XPS files,[37] and upload Word documents like blog posts on services such as WordPress.

Word 2010 allows the customization of the Ribbon,[38] adds a Backstage view for file management,[39] has improved document navigation, allows creation and embedding of screenshots,[40] and integrates with online services such as Microsoft OneDrive.[41]

Word 2019 added a dictation function.

Word 2021 added co-authoring, a visual refresh on the start experience and tabs, automatic cloud saving, dark mode, line focus, an updated draw tab, and support for ODF 1.3.

Word for MacEdit

The Mac was introduced on January 24, 1984, and Microsoft introduced Word 1.0 for Mac a year later, on January 18, 1985. The DOS, Mac, and Windows versions are quite different from each other. Only the Mac version was WYSIWYG and used a graphical user interface, far ahead of the other platforms. Each platform restarted its version numbering at «1.0».[42] There was no version 2 on the Mac, but version 3 came out on January 31, 1987, as described above. Word 4.0 came out on November 6, 1990, and added automatic linking with Excel, the ability to flow text around graphics, and a WYSIWYG page view editing mode. Word 5.1 for Mac, released in 1992 ran on the original 68000 CPU and was the last to be specifically designed as a Macintosh application. The later Word 6 was a Windows port and poorly received. Word 5.1 continued to run well until the last Classic MacOS. Many people continue to run Word 5.1 to this day under an emulated Mac classic system for some of its excellent features, such as document generation and renumbering, or to access their old files.

Microsoft Word 2011 running on OS X

In 1997, Microsoft formed the Macintosh Business Unit as an independent group within Microsoft focused on writing software for Mac OS. Its first version of Word, Word 98, was released with Office 98 Macintosh Edition. Document compatibility reached parity with Word 97,[32] and it included features from Word 97 for Windows, including spell and grammar checking with squiggles.[43] Users could choose the menus and keyboard shortcuts to be similar to either Word 97 for Windows or Word 5 for Mac OS.

Word 2001, released in 2000, added a few new features, including the Office Clipboard, which allowed users to copy and paste multiple items.[44] It was the last version to run on classic Mac OS and, on Mac OS X, it could only run within the Classic Environment. Word X, released in 2001, was the first version to run natively on, and required, Mac OS X,[43] and introduced non-contiguous text selection.[45]

Word 2004 was released in May 2004. It included a new Notebook Layout view for taking notes either by typing or by voice.[46] Other features, such as tracking changes, were made more similar with Office for Windows.[47]

Word 2008, released on January 15, 2008, included a Ribbon-like feature, called the Elements Gallery, that can be used to select page layouts and insert custom diagrams and images. It also included a new view focused on publishing layout, integrated bibliography management,[48] and native support for the new Office Open XML format. It was the first version to run natively on Intel-based Macs.[49]

Word 2011, released in October 2010, replaced the Elements Gallery in favor of a Ribbon user interface that is much more similar to Office for Windows,[50] and includes a full-screen mode that allows users to focus on reading and writing documents, and support for Office Web Apps.[51]

Word 2021 added real-time co-authoring, automatic cloud saving, dark mode, immersive reader enhancements, line focus, a visual refresh, the ability to save pictures in SVG format, and a new Sketched style outline.

File formatsEdit

| DOC | Legacy Word document |

|---|---|

| DOT | Legacy Word templates |

| WBK | Legacy Word document backup |

| DOCX | XML Word document |

| DOCM | XML Word macro-enabled document |

| DOTX | XML Word template |

| DOTM | XML Word macro-enabled template |

| DOCB | XML Word binary document |

Filename extensionsEdit

Microsoft Word’s native file formats are denoted either by a .doc or .docx filename extension.

Although the .doc extension has been used in many different versions of Word, it actually encompasses four distinct file formats:

- Word for DOS

- Word for Windows 1 and 2; Word 3 and 4 for Mac OS

- Word 6 and Word 95 for Windows; Word 6 for Mac OS

- Word 97 and later for Windows; Word 98 and later for Mac OS

(The classic Mac OS of the era did not use filename extensions.)[52]

The newer .docx extension signifies the Office Open XML international standard for Office documents and is used by default by Word 2007 and later for Windows as well as Word 2008 and later for macOS.[53]

Binary formats (Word 97–2007)Edit

During the late 1990s and early 2000s, the default Word document format (.DOC) became a de facto standard of document file formats for Microsoft Office users.[citation needed] There are different versions of «Word Document Format» used by default in Word 97–2007.[54] Each binary word file is a Compound File,[55] a hierarchical file system within a file. According to Joel Spolsky, Word Binary File Format is extremely complex mainly because its developers had to accommodate an overwhelming number of features and prioritize performance over anything else.

As with all OLE Compound Files, Word Binary Format consists of «storages», which are analogous to computer folders and «streams», which are similar to computer files. Each storage may contain streams or other storage. Each Word Binary File must contain a stream called the «WordDocument» stream and this stream must start with a File Information Block (FIB).[57] FIB serves as the first point of reference for locating everything else, such as where the text in a Word document starts, ends, what version of Word created the document and other attributes.

Word 2007 and later continue to support the DOC file format, although it is no longer the default.

XML Document (Word 2003)Edit

The .docx XML format introduced in Word 2003[58] was a simple, XML-based format called WordProcessingML or WordML.

The Microsoft Office XML formats are XML-based document formats (or XML schemas) introduced in versions of Microsoft Office prior to Office 2007. Microsoft Office XP introduced a new XML format for storing Excel spreadsheets and Office 2003 added an XML-based format for Word documents.

These formats were succeeded by Office Open XML (ECMA-376) in Microsoft Office 2007.

Cross-version compatibilityEdit

Opening a Word Document file in a version of Word other than the one with which it was created can cause an incorrect display of the document. The document formats of the various versions change in subtle and not-so-subtle ways (such as changing the font or the handling of more complex tasks like footnotes). Formatting created in newer versions does not always survive when viewed in older versions of the program, nearly always because that capability does not exist in the previous version.[59] Rich Text Format (RTF), an early effort to create a format for interchanging formatted text between applications, is an optional format for Word that retains most formatting and all content of the original document.

Third-party formatsEdit

Plugins permitting the Windows versions of Word to read and write formats it does not natively support, such as international standard OpenDocument format (ODF) (ISO/IEC 26300:2006), are available. Up until the release of Service Pack 2 (SP2) for Office 2007, Word did not natively support reading or writing ODF documents without a plugin, namely the SUN ODF Plugin or the OpenXML/ODF Translator. With SP2 installed, ODF format 1.1 documents can be read and saved like any other supported format in addition to those already available in Word 2007.[59][60][61][62][63] The implementation faces substantial criticism, and the ODF Alliance and others have claimed that the third-party plugins provide better support.[64] Microsoft later declared that the ODF support has some limitations.[65]

In October 2005, one year before the Microsoft Office 2007 suite was released, Microsoft declared that there was insufficient demand from Microsoft customers for the international standard OpenDocument format support and that therefore it would not be included in Microsoft Office 2007. This statement was repeated in the following months.[66][67][68][69] As an answer, on October 20, 2005, an online petition was created to demand ODF support from Microsoft.[70]

In May 2006, the ODF plugin for Microsoft Office was released by the OpenDocument Foundation.[71] Microsoft declared that it had no relationship with the developers of the plugin.[72]

In July 2006, Microsoft announced the creation of the Open XML Translator project – tools to build a technical bridge between the Microsoft Office Open XML Formats and the OpenDocument Format (ODF). This work was started in response to government requests for interoperability with ODF. The goal of the project was not to add ODF support to Microsoft Office, but only to create a plugin and an external toolset.[73][74] In February 2007, this project released a first version of the ODF plugin for Microsoft Word.[75]

In February 2007, Sun released an initial version of its ODF plugin for Microsoft Office.[76] Version 1.0 was released in July 2007.[77]

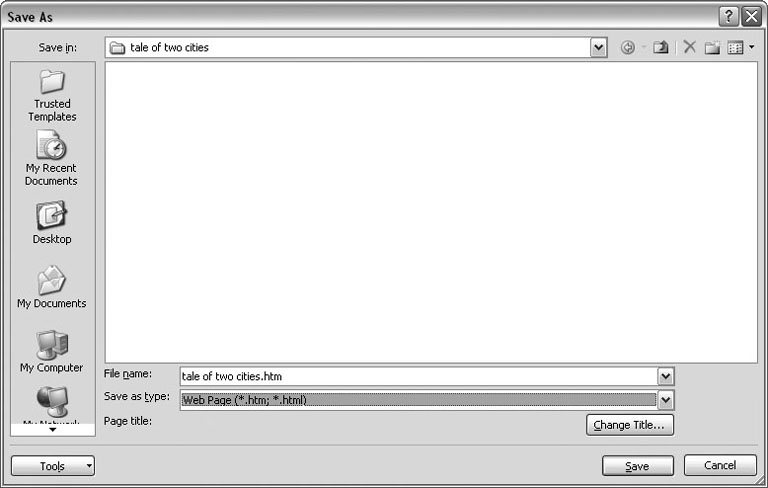

Microsoft Word 2007 (Service Pack 1) supports (for output only) PDF and XPS formats, but only after manual installation of the Microsoft ‘Save as PDF or XPS’ add-on.[78][79] On later releases, this was offered by default.

Features and flawsEdit

Among its features, Word includes a built-in spell checker, a thesaurus, a dictionary, and utilities for manipulating and editing text. It supports creating tables. Depending on the version, it can perform simple calculations, and supports formatting formulas and equations.

The following are some aspects of its feature set.

TemplatesEdit

Several later versions of Word include the ability for users to create their formatting templates, allowing them to define a file in which: the title, heading, paragraph, and other element designs differ from the standard Word templates.[80] Users can find how to do this under the Help section located near the top right corner (Word 2013 on Windows 8).

For example, Normal.dotm is the master template from which all Word documents are created. It determines the margin defaults as well as the layout of the text and font defaults. Although Normal.dotm is already set with certain defaults, the user can change it to new defaults. This will change other documents which were created using the template.[81] It was previously Normal.dot.[82]

Image formatsEdit

Word can import and display images in common bitmap formats such as JPG and GIF. It can also be used to create and display simple line art. Microsoft Word added support[83] for the common SVG vector image format in 2017 for Office 365 ProPlus subscribers and this functionality was also included in the Office 2019 release.

WordArtEdit

An example image created with WordArt

WordArt enables drawing text in a Microsoft Word document such as a title, watermark, or other text, with graphical effects such as skewing, shadowing, rotating, stretching in a variety of shapes and colors, and even including three-dimensional effects. Users can apply formatting effects such as shadow, bevel, glow, and reflection to their document text as easily as applying bold or underline. Users can also spell-check text that uses visual effects and add text effects to paragraph styles.

MacrosEdit

A macro is a rule of pattern that specifies how a certain input sequence (often a sequence of characters) should be mapped to an output sequence according to a defined process. Frequently used or repetitive sequences of keystrokes and mouse movements can be automated. Like other Microsoft Office documents, Word files can include advanced macros and even embedded programs. The language was originally WordBasic, but changed to Visual Basic for Applications as of Word 97.

This extensive functionality can also be used to run and propagate viruses in documents. The tendency for people to exchange Word documents via email, USB flash drives, and floppy disks made this an especially attractive vector in 1999. A prominent example was the Melissa virus, but countless others have existed.

These macro viruses were the only known cross-platform threats between Windows and Macintosh computers and they were the only infection vectors to affect any macOS system up until the advent of video codec trojans in 2007.[citation needed] Microsoft released patches for Word X and Word 2004 that effectively eliminated the macro problem on the Mac by 2006.

Word’s macro security setting, which regulates when macros may execute, can be adjusted by the user, but in the most recent versions of Word, it is set to HIGH by default, generally reducing the risk from macro-based viruses, which have become uncommon.

Layout issuesEdit

Before Word 2010 (Word 14) for Windows, the program was unable to correctly handle ligatures defined in OpenType fonts.[84] Those ligature glyphs with Unicode codepoints may be inserted manually, but are not recognized by Word for what they are, breaking spell checking, while custom ligatures present in the font are not accessible at all. Since Word 2010, the program now has advanced typesetting features which can be enabled,[85] OpenType ligatures,[86] kerning and hyphenation (previous versions already had the latter two features). Other layout deficiencies of Word include the inability to set crop marks or thin spaces. Various third-party workaround utilities have been developed.[87]

In Word 2004 for Mac OS X, support of complex scripts was inferior even to Word 97[88] and Word 2004 did not support Apple Advanced Typography features like ligatures or glyph variants.[89]

Issues with technical documentsEdit

Microsoft Word is only awkwardly suitable for some kinds of technical writing, specifically, that which requires mathematical equations,[90] figure placement, table placement and cross-references to any of these items.[citation needed] The usual workaround for equations is to use a third-party equation typesetter.[citation needed] Figures and tables must be placed manually; there is an anchor mechanism but it is not designed for fully automatic figure placement and editing text after placing figures and tables often requires re-placing those items by moving the anchor point and even then the placement options are limited.[citation needed] This problem is deeply baked into Word’s structure since 1985 as it does not know where page breaks will occur until the document is printed.[citation needed]

Bullets and numberingEdit

Microsoft Word supports bullet lists and numbered lists. It also features a numbering system that helps add correct numbers to pages, chapters, headers, footnotes, and entries of tables of content; these numbers automatically change to correct ones as new items are added or existing items are deleted. Bullets and numbering can be applied directly to paragraphs and converted to lists.[91] Word 97 through 2003, however, had problems adding correct numbers to numbered lists. In particular, a second irrelevant numbered list might have not started with number one but instead resumed numbering after the last numbered list. Although Word 97 supported a hidden marker that said the list numbering must restart afterward, the command to insert this marker (Restart Numbering command) was only added in Word 2003. However, if one were to cut the first item of the listed and paste it as another item (e.g. fifth), then the restart marker would have moved with it and the list would have restarted in the middle instead of at the top.[92]

Word continues to default to non-Unicode characters and non-hierarchical bulleting, despite user preference for Powerpoint-style symbol hierarchies (e.g., filled circle/emdash/filled square/endash/emptied circle) and universal compatibility.

AutoSummarizeEdit

Available in certain versions of Word (e.g., Word 2007), AutoSummarize highlights passages or phrases that it considers valuable and can be a quick way of generating a crude abstract or an executive summary.[93] The amount of text to be retained can be specified by the user as a percentage of the current amount of text.

According to Ron Fein of the Word 97 team, AutoSummarize cuts wordy copy to the bone by counting words and ranking sentences. First, AutoSummarize identifies the most common words in the document (barring «a» and «the» and the like) and assigns a «score» to each word – the more frequently a word is used, the higher the score. Then, it «averages» each sentence by adding the scores of its words and dividing the sum by the number of words in the sentence – the higher the average, the higher the rank of the sentence. «It’s like the ratio of wheat to chaff,» explains Fein.[94]

AutoSummarize was removed from Microsoft Word for Mac OS X 2011, although it was present in Word for Mac 2008. AutoSummarize was removed from the Office 2010 release version (14) as well.[95]

Other platformsEdit

Word for mobileEdit

Word Mobile[96] is a word processor that allows creating and editing documents. It supports basic formatting, such as bolding, changing font size, and changing colors (from red, yellow, or green). It can add comments, but can’t edit documents with tracked changes. It can’t open password-protected documents; change the typeface, text alignment, or style (normal, heading 1); create bulleted lists; insert pictures; or undo.[97][98][99] Word Mobile is neither able to display nor insert footnotes, endnotes, page headers, page footers, page breaks, certain indentation of lists, and certain fonts while working on a document, but retains them if the original document has them.[100] In addition to the features of the 2013 version, the 2007 version on Windows Mobile also has the ability to save documents in the Rich Text Format and open legacy PSW (Pocket Word).[100] Furthermore, it includes a spell checker, word count tool, and a «Find and Replace» command. In 2015, Word Mobile became available for Windows 10 and Windows 10 Mobile on Windows Store.[101]

Support for Windows 10 Mobile version ended in January 12, 2021.[102]

Word for the webEdit

Word for the web is a free lightweight version of Microsoft Word available as part of Office on the web, which also includes web versions of Microsoft Excel and Microsoft PowerPoint.

Word for the web lacks some Ribbon tabs, such as Design and Mailings. Mailings allows users to print envelopes and labels and manage mail merge printing of Word documents.[103][104] Word for the web is not able to edit certain objects, such as: equations, shapes, text boxes or drawings, but a placeholder may be present in the document. Certain advanced features like table sorting or columns will not be displayed but are preserved as they were in the document. Other views available in the Word desktop app (Outline, Draft, Web Layout, and Full-Screen Reading) are not available, nor are side-by-side viewing, split windows, and the ruler.[105]

Password protectionEdit

Three password types can be set in Microsoft Word,

- Password to open a document[106]

- Password to modify a document[106]

- Password restricting formatting and editing[107]

The second and third password types were developed by Microsoft for convenient shared use of documents rather than for their protection. There is no encryption of documents that are protected by such passwords and the Microsoft Office protection system saves a hash sum of a password in a document’s header where it can be easily accessed and removed by the specialized software. Password to open a document offers much tougher protection that had been steadily enhanced in the subsequent editions of Microsoft Office.

Word 95 and all the preceding editions had the weakest protection that utilized a conversion of a password to a 16-bit key.

Key length in Word 97 and 2000 was strengthened up to 40 bit. However, modern cracking software allows removing such a password very quickly – a persistent cracking process takes one week at most. Use of rainbow tables reduces password removal time to several seconds. Some password recovery software can not only remove a password but also find an actual password that was used by a user to encrypt the document using the brute-force attack approach. Statistically, the possibility of recovering the password depends on the password strength.

Word’s 2003/XP version default protection remained the same but an option that allowed advanced users to choose a Cryptographic Service Provider was added.[108] If a strong CSP is chosen, guaranteed document decryption becomes unavailable and, therefore, a password can’t be removed from the document. Nonetheless, a password can be fairly quickly picked with a brute-force attack, because its speed is still high regardless of the CSP selected. Moreover, since the CSPs are not active by default, their use is limited to advanced users only.

Word 2007 offers significantly more secure document protection which utilizes the modern Advanced Encryption Standard (AES) that converts a password to a 128-bit key using a SHA-1 hash function 50,000 times. It makes password removal impossible (as of today, no computer that can pick the key in a reasonable amount of time exists) and drastically slows the brute-force attack speed down to several hundreds of passwords per second.

Word’s 2010 protection algorithm was not changed apart from the increasing number of SHA-1 conversions up to 100,000 times and consequently, the brute-force attack speed decreased two times more.

ReceptionEdit

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (December 2021)

Initial releases of Word were met with criticism. Byte in 1984 criticized the documentation for Word 1.1 and 2.0 for DOS, calling it «a complete farce». It called the software «clever, put together well and performs some extraordinary feats», but concluded that «especially when operated with the mouse, has many more limitations than benefits … extremely frustrating to learn and operate efficiently».[109] PC Magazine‘s review was very mixed, stating: «I’ve run into weird word processors before, but this is the first time one’s nearly knocked me down for the count» but acknowledging that Word’s innovations were the first that caused the reviewer to consider abandoning WordStar. While the review cited an excellent WYSIWYG display, sophisticated print formatting, windows, and footnoting as merits, it criticized many small flaws, very slow performance, and «documentation produced by Madame Sadie’s Pain Palace». It concluded that Word was «two releases away from potential greatness».[110]

Compute!’s Apple Applications in 1987 stated that «despite a certain awkwardness», Word 3.01 «will likely become the major Macintosh word processor» with «far too many features to list here». While criticizing the lack of true WYSIWYG, the magazine concluded that «Word is marvelous. It’s like a Mozart or Edison, whose occasional gaucherie we excuse because of his great gifts».[111]

Compute! in 1989 stated that Word 5.0’s integration of text and graphics made it «a solid engine for basic desktop publishing». The magazine approved of improvements to text mode, described the $75 price for upgrading from an earlier version as «the deal of the decade» and concluded that «as a high-octane word processor, Word is worth a look».[112]

During the first quarter of 1996, Microsoft Word accounted for 80% of the worldwide word processing market.[113]

Release historyEdit

| Legend: | Old version, not maintained | Older version, still maintained | Current stable version |

|---|

Microsoft Word 2010 running on Windows 7

| Year released | Name | Version | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1989 | Word for Windows 1.0 | 1.0 | Code-named Opus[114] |

| 1990 | Word for Windows 1.1 | 1.1 | For Windows 3.0.[115] Code-named Bill the Cat[citation needed] |

| 1990 | Word for Windows 1.1a | 1.1a | On March 25, 2014, Microsoft made the source code to Word for Windows 1.1a available to the public via the Computer History Museum.[116][117] |

| 1991 | Word for Windows 2.0 | 2.0 | Included in Office 3.0. |

| 1993 | Word for Windows 6.0 | 6.0 | Version numbers 3, 4, and 5 were skipped, to bring Windows version numbering in line with that of DOS, Mac OS, and WordPerfect (the main competing word processor at the time). Also, a 32-bit version for Windows NT only. Included in Office 4.0, 4.2, and 4.3. |

| 1995 | Word for Windows 95 | 7.0 | Included in Office 95 |

| 1997 | Word 97 | 8.0 | Included in Office 97 |

| 1998 | Word 98 | 8.5 | Included in Office 97 |

| 1999 | Word 2000 | 9.0 | Included in Office 2000 |

| 2001 | Word 2002 | 10.0 | Included in Office XP |

| 2003 | Microsoft Word 2003 | 11.0 | Included in Office 2003 |

| 2006 | Microsoft Word 2007 | 12.0 | Included in Office 2007; released to businesses on November 30, 2006, released worldwide to consumers on January 30, 2007. Extended support until October 10, 2017. |

| 2010 | Word 2010 | 14.0 | Included in Office 2010; skipped 13.0 due to triskaidekaphobia.[118] |

| 2013 | Word 2013 | 15.0 | Included in Office 2013 |

| 2016 | Word 2016 | 16.0 | Included in Office 2016 |

| 2019 | Word 2019 | 16.0 | Included in Office 2019 |

| 2021 | Word 2021 | 16.0 | Included in Office 2021 |

| Year released | Name | Version | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1985 | Word 1 | 1.0 | |

| 1987 | Word 3 | 3.0 | |

| 1989 | Word 4 | 4.0 | Part of Office 1.0 and 1.5 |

| 1991 | Word 5 | 5.0 |

|

| 1992 | Word 5.1 | 5.1 |

|

| 1993 | Word 6 | 6.0 |

|

| 1998 | Word 98 | 8.5 |

|

| 2000 | Word 2001 | 9.0 |

|

| 2001 | Word v. X | 10.0 |

|

| 2004 | Word 2004 | 11.0 | Part of Office 2004 |

| 2008 | Word 2008 | 12.0 | Part of Office 2008 |

| 2010 | Word 2011 | 14.0 | Part of Office 2011; skipped 13.0 due to triskaidekaphobia.[118] |

| 2015 | Word 2016 | 16.0 | Part of Office 2016; skipped 15.0 |

| 2019 | Word 2019 | 16.0 | Part of Office 2019 |

| 2021 | Word 2021 | 16.0 | Included in Office 2021 |

| Year released | Name | Version | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1983 | Word 1 | 1.0 | Initial version of Word |

| 1985 | Word 2 | 2.0 | |

| 1986 | Word 3 | 3.0 | Removed copy protection |

| 1987 | Word 4 | 4.0 | |

| 1989 | Word 5 | 5.0 | |

| 1991 | Word 5.1 | 5.1 | |

| 1991 | Word 5.5 | 5.5 | First DOS version to use a Windows-like user interface |

| 1993 | Word 6 | 6.0 | Last DOS version. |

| Platform | Year released | Name | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|

| Atari ST | 1988 | Microsoft Write | Based on Microsoft Word 1.05 for Mac OS |

| OS/2 | 1989 | Microsoft Word 5.0 | Word 5.0 ran both under DOS and OS/2 dual-mode as a native OS/2 application |

| OS/2 | 1991 | Microsoft Word 5.5 | Word 5.5 ran both under DOS and OS/2 dual-mode as a native OS/2 application |

| OS/2 | 1990 | Microsoft Word for OS/2 Presentation Manager version 1.1 | |

| OS/2 | 1991 | Microsoft Word for OS/2 Presentation Manager version 1.2[citation needed] | |

| SCO Unix | 1990 | Microsoft Word for Unix version 5.0[119] | |

| SCO Unix | 1991 | Microsoft Word for Unix version 5.1[120] |

ReferencesEdit

- ^ «Update history for Microsoft Office 2019». Microsoft Docs. Retrieved April 13, 2021.

- ^ a b «C++ in MS Office». cppcon. July 17, 2014. Archived from the original on November 7, 2019. Retrieved June 25, 2019.

- ^ «System requirements for Office». Office.com. Microsoft. Retrieved March 30, 2019.

- ^ «Update history for Office for Mac». Microsoft Docs.

- ^ Lardinois, Frederic (January 29, 2015). «Microsoft’s Office For Android Tablets Comes Out Of Preview». TechCrunch. Retrieved January 28, 2023.

- ^ «Microsoft Word: Write, Edit & Share Docs on the Go APKs». APKMirror.

- ^ Cunningham, Andrew (March 27, 2014). «Microsoft brings Office to iPad, makes iPhone version free to all». Ars Technica. Retrieved January 27, 2023.

- ^ «Microsoft Word». App Store.

- ^ «Version 1.0 of today’s most popular applications, a visual tour – Pingdom Royal». Pingdom. June 17, 2009. Archived from the original on August 13, 2018. Retrieved April 12, 2016.

- ^ a b c d A. Allen, Roy (October 2001). «Chapter 12: Microsoft in the 1980s» (PDF). A History of the Personal Computer: The People and the Technology (1st ed.). Allan Publishing. pp. 12/25–12/26. ISBN 978-0-9689108-0-1. Retrieved November 7, 2010.

- ^ «Microsoft Office online, Getting to know you…again: The Ribbon». Archived from the original on May 11, 2011.

- ^ «The history of branding, Microsoft history». Archived from the original on May 28, 2009.

- ^ a b c d e Edwards, Benj (October 22, 2008). «Microsoft Word Turns 25». PC World. Archived from the original on July 4, 2012. Retrieved November 7, 2010.

- ^ Tsang, Cheryl (1999). Microsoft First Generation. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-471-33206-0.

- ^ Schaut, Rick (May 19, 2004). «Anatomy of a Software Bug». MSDN Blogs. Archived from the original on February 1, 2010. Retrieved December 2, 2006.

- ^ a b Markoff, John (May 30, 1983). «Mouse and new WP program join Microsoft product lineup». InfoWorld. p. 10. Retrieved November 7, 2010.

- ^ Pollack, Andrew (August 25, 1983). «Computerizing Magazines». The New York Times. Retrieved April 24, 2013.

- ^ Lemmons, Phil (December 1983). «Microsoft Windows». BYTE. p. 48. Retrieved October 20, 2013.

- ^ Advertisement (December 1983). «Undo. Windows. Mouse. Finally». BYTE. pp. 88–89. Retrieved October 20, 2013.

- ^ Peterson, W.E. Pete (1994). Almost Perfect: How a Bunch of Regular Guys Built Wordperfect Corporation. Prima Publishing. ISBN 0-7881-9991-9.

- ^ a b c d e f Knight, Dan (May 22, 2008). «Microsoft Word for Mac History». Low End Mac. Retrieved November 7, 2010.

- ^ «The Piece Table».

- ^ Brand, Stewart (1989). Whole Earth Software Catalog. ISBN 9780385233019.

For a year, I waited for a heavier-duty word processor than MACWRITE. I finally got it— WORD.

- ^ a b c Schaut, Rick (February 26, 2004). «Mac Word 6.0». Buggin’ My Life Away. MSDN Blogs. Archived from the original on May 14, 2004. Retrieved June 21, 2010.

- ^ «Atari announces agreement with Microsoft». Atarimagazines.com. April 25, 2008. Retrieved June 21, 2010.

- ^ «Feature Review: Microsoft Write». Atarimagazines.com. April 25, 2008. Retrieved June 21, 2010.

- ^ «Today’s Atari Corp.: A close up look inside». Atarimagazines.com. April 25, 2008. Retrieved June 21, 2010.

- ^ Miller, Michael J. (November 12, 1990). «First Look: Microsoft Updates Look of And Adds Pull-Down Menus to Character-Based Word 5.5». InfoWorld. p. 151. Retrieved November 7, 2010.

- ^ Needleman, Raphael (November 19, 1990). «Microsoft Word 5.5: Should You Fight or Switch?». InfoWorld. p. 106. Retrieved November 7, 2010.

- ^ «Microsoft Word 5.5 for MS-DOS (EXE format)». Microsoft Download Center. Retrieved August 19, 2011.

- ^ «War of the Words». InfoWorld. February 7, 1994. pp. 66–79. Retrieved November 7, 2010.

- ^ a b Lockman, James T.W. (May 15, 1998). «UGeek Software Review: Microsoft Office 98 Gold for Macintosh». Archived from the original on December 3, 2010. Retrieved November 7, 2010.

- ^ Rose, Daniel. «Microsoft Office for Windows NT». DanielSays.com – Daniel’s Legacy Computer Collections. Archived from the original on January 27, 2015. Retrieved May 15, 2015.

- ^ Ericson, Richard (October 11, 2006). «Final Review: The Lowdown on Office 2007». Computerworld. Retrieved November 8, 2010.

- ^ Lowe, Scott (December 11, 2006). «An introduction to the Microsoft Office 2007 ribbon interface». TechRepublic. Retrieved December 14, 2021.

- ^ Shultz, Greg (February 25, 2009). «Be ready for new and improved applets in Windows 7». TechRepublic. Archived from the original on December 14, 2021. Retrieved December 14, 2021.

- ^ a b Lowe, Scott (January 26, 2007). «Explore what is new and different in Microsoft Word 2007». TechRepublic. Retrieved December 14, 2021.

- ^ Mendelson, Edward (May 11, 2010). «Microsoft Office 2010». PC Magazine. Retrieved November 8, 2010.

- ^ Mendelson, Edward (May 11, 2010). «Microsoft Office 2010: Office 2010’s Backstage View». PC Magazine. Archived from the original on December 2, 2010. Retrieved November 8, 2010.

- ^ Mendelson, Edward (May 11, 2010). «Microsoft Office 2010: Lots of Graphics Options». PC Magazine. Archived from the original on April 24, 2010. Retrieved December 14, 2021.

- ^ «Introduction to Word Web App». Microsoft. Retrieved November 8, 2010.

- ^ «Microsoft Word 1.x (Mac)». WinWorld. Retrieved December 22, 2021.

- ^ a b McLean, Prince (November 12, 2007). «Road to Mac Office 2008: an introduction (Page 3)». AppleInsider. Archived from the original on July 7, 2011. Retrieved November 7, 2010.

- ^ Tetrault, Gregory (January 2001). «Review: Microsoft Office 2001». ATPM: About This Particular Macintosh. Retrieved November 7, 2010.

- ^ Negrino, Tom (February 1, 2002). «Review: Microsoft Office v. X». MacWorld. Archived from the original on August 18, 2010. Retrieved November 7, 2010.

- ^ Lunsford, Kelly; Michaels, Philip; Snell, Jason (March 3, 2004). «Office 2004: First Look». MacWorld. Archived from the original on June 25, 2010. Retrieved November 7, 2010.

- ^ Friedberg, Steve (May 25, 2004). «Review: Microsoft Office». MacNN. Archived from the original on April 5, 2010. Retrieved November 7, 2010.

- ^ McLean, Prince (November 14, 2007). «Road to Mac Office 2008: Word ’08 vs Pages 3.0». AppleInsider. Retrieved November 7, 2010.

- ^ McLean, Prince (November 12, 2007). «Road to Mac Office 2008: an introduction (Page 4)». AppleInsider. Archived from the original on July 7, 2011. Retrieved November 7, 2010.

- ^ McLean, Prince (March 29, 2010). «New Office 11 for Mac sports dense ribbons of buttons». AppleInsider. Retrieved November 7, 2010.

- ^ Dilger, Daniel Eran (October 25, 2010). «Review: Microsoft’s Office 2011 for Mac (Page 2)». Apple Insider. Archived from the original on October 28, 2010. Retrieved November 7, 2010.

- ^ Oakley, Howard (May 2, 2015). «.why .the .extensions? Quirks in the naming of files and folders». The Eclectic Light Company. Archived from the original on February 26, 2020. Retrieved February 26, 2020.

Macs used to be the only computers that did not need filename extensions…on classic Mac systems, you can name applications, documents, and most other files almost anything that you like, as the name is not linked in any way to the type of thing that file is.

- ^ «DOCX Transitional (Office Open XML), ISO 29500:2008-2016, ECMA-376, Editions 1-5». loc.gov. January 20, 2017. Retrieved July 9, 2019.

- ^ «5 Appendix A: Product Behavior» (PDF). [MS-DOC]: Word (.doc) Binary File Format (PDF). Redmond, WA: Microsoft. Archived from the original on January 10, 2015. Retrieved January 10, 2015.

- ^ «2.1 File Structure» (PDF). [MS-DOC]: Word (.doc) Binary File Format (PDF). Redmond, WA: Microsoft. Archived from the original on January 10, 2015. Retrieved January 10, 2015.

- ^ «2.1.1 WordDocument Stream» (PDF). [MS-DOC]: Word (.doc) Binary File Format (PDF). Redmond, WA: Microsoft. Archived from the original on January 10, 2015. Retrieved January 10, 2015.

- ^ «What You Can Do with Word XML [Word 2003 XML Reference]». MSDN. 2004.

- ^ a b Casson, Tony; Ryan, Patrick S. (May 1, 2006). «Open Standards, Open Source Adoption in the Public Sector, and Their Relationship to Microsoft’s Market Dominance». In Bolin, Sherrie (ed.). Standards Edge: Unifier or Divider?. Sheridan Books. p. 87. SSRN 1656616.

- ^ «Microsoft Expands List of Formats Supported in Microsoft Office, May 21, 2008». News Center. Microsoft. May 21, 2008. Retrieved April 24, 2013.

- ^ Fulton, Scott M. III (May 21, 2008). «Next Office 2007 service pack will include ODF, PDF support options». Betanews.

- ^ Andy Updegrove (May 21, 2008). «Microsoft Office 2007 to Support ODF – and not OOXML, May 21, 2008». Consortiuminfo.org. Retrieved June 21, 2010.

- ^ «Microsoft: Why we chose ODF support over OOXML, 23 May 2008». Software.silicon.com. Archived from the original on July 21, 2009. Retrieved June 21, 2010.

- ^ «Fact-sheet Microsoft ODF support» (PDF). odfalliance. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 11, 2009. Retrieved May 24, 2009.

Microsoft Excel 2007 will process ODF spreadsheet documents when loaded via the Sun Plug-In 3.0 for Microsoft Office or the SourceForge «OpenXML/ODF Translator Add-in for Office,» but will fail when using the «built-in» support provided by Office 2007 SP2.

- ^ Microsoft. «What happens when I save a Word 2007 document in the OpenDocument Text format?». Archived from the original on March 18, 2010. Retrieved April 5, 2010.

- ^ Goodwins, Rupert (October 3, 2005). «Office 12 to support PDF creation, 3 October 2005». News.zdnet.co.uk. Archived from the original on July 23, 2009. Retrieved June 21, 2010.

- ^ Marson, Ingrid (October 6, 2005). «Microsoft ‘must support OpenDocument’, 6 October 2005». News.zdnet.co.uk. Archived from the original on July 25, 2009. Retrieved June 21, 2010.

- ^ March 23, 2006, Gates: Office 2007 will enable a new class of application Mass. holding tight to OpenDocument – ZDNet Archived July 21, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ «May 08, 2006 – Microsoft Office to get a dose of OpenDocument». Zdnet.com.au. Archived from the original on July 22, 2009. Retrieved June 21, 2010.

- ^ OpenDocument Fellowship (October 20, 2005). «OpenDocument Support: Tell Microsoft You Want It!, 20 October 2005». Opendocumentfellowship.com. Archived from the original on March 23, 2008. Retrieved June 21, 2010.

- ^ «Coming soon: ODF for MS Office, May 04, 2006». Linux-watch.com. May 4, 2006. Retrieved June 21, 2010.

- ^ LaMonica, Martin (May 5, 2006). «Microsoft Office to get a dose of OpenDocument». CNET News. Retrieved June 21, 2010.

- ^ «Microsoft Expands Document Interoperability, July 5, 2006». Microsoft.com. July 5, 2006. Archived from the original on February 4, 2007. Retrieved June 21, 2010.

- ^ Jones, Brian; Rajabi, Zeyad (July 6, 2006). «Open XML Translator project announced (ODF support for Office)». Brian Jones: Office Solutions. Microsoft. Archived from the original on January 18, 2010. Retrieved April 24, 2013.

- ^ LaMonica, Martin (February 1, 2007). «Microsoft to release ODF document converter». CNet News. Retrieved April 24, 2013.

- ^ Lombardi, Candace (February 7, 2007). «Sun to release ODF translator for Microsoft Office». CNET. Retrieved June 21, 2010.

- ^ Paul, Ryan (July 7, 2007). «Sun releases ODF Plugin 1.0 for Microsoft Office, July 07, 2007». Arstechnica.com. Retrieved June 21, 2010.

- ^ «Download details: 2007 Microsoft Office Add-in: Microsoft Save as PDF or XPS». Microsoft.com. November 8, 2006. Retrieved June 21, 2010.

- ^ Microsoft to remove PDF support from Office 2007 in wake of Adobe dispute, Friday, June 2, 2006 Microsoft to remove PDF support from Office 2007 in wake of Adobe dispute | TG Daily Archived February 1, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Klein, Matt. «Word Formatting: Mastering Styles and Document Themes». How-To Geek. Retrieved July 9, 2019.

- ^ «Change the Normal template (Normal.dotm )». support.microsoft.com. Retrieved May 20, 2021.

- ^ in-depth explanation of Normal.dot Archived June 20, 2005, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ «Edit SVG images in Microsoft Office 365». Office Support. Microsoft. Retrieved February 4, 2019.

- ^ What’s new in Word 2010. Retrieved July 1, 2010.

- ^ Improving the look of papers written in Microsoft Word. Retrieved May 30, 2010.

- ^ How to Enable OpenType Ligatures in Word 2010, Oreszek Blog, May 17, 2009.

- ^ Such as «How to delete a blank page in Word». Sbarnhill.mvps.org. Archived from the original on May 5, 2010. Retrieved June 21, 2010.

- ^ Alan Wood. «Unicode and Multilingual Editors and Word Processors for Mac OS X».

- ^ Neuburg, Matt (May 19, 2004). «TidBITS : Word Up! Word 2004, That Is». Db.tidbits.com. Archived from the original on July 8, 2012. Retrieved June 21, 2010.

- ^ «Automatically numbering equations and other equation-related questions in Word for Mac 2011». Microsoft Community. February 6, 2013.

- ^ McGhie, John (March 26, 2011). «Word’s numbering explained». word.mvps.org.

- ^ Aldis, Margaret (March 26, 2011). «Methods for restarting list numbering». Word.mvps.org.

- ^ «How To Access Auto Summarize in Microsoft Word 2007». Sue’s Word Tips. December 14, 2011. Retrieved July 9, 2019.

- ^ Gore, Karenna (February 9, 1997). «Cognito Auto Sum». Slate. Retrieved June 21, 2010.

- ^ Changes in Word 2010 (for IT pros). Technet.microsoft.com (May 16, 2012). Retrieved July 17, 2013.

- ^ Word Mobile

- ^ Ralph, Nate. «Office for Windows Phone 8: Your handy starter guide». TechHive. Archived from the original on October 15, 2014. Retrieved August 30, 2014.

- ^ Wollman, Dana. «Microsoft Office Mobile for iPhone hands-on». Engadget. Retrieved August 30, 2014.

- ^ Pogue, David (June 19, 2013). «Microsoft Adds Office for iPhone. Yawn». The New York Times. Retrieved August 30, 2014.

- ^ a b Unsupported Features in Word Mobile. Microsoft. Retrieved September 21, 2007.

- ^ Koenigsbauer, Kirk; Microsoft 365, Corporate Vice President for (July 29, 2015). «Office Mobile apps for Windows 10 are here!». Microsoft 365 Blog. Retrieved July 11, 2020.

- ^ Office Apps for Windows 10 Mobile: End of Support for Windows Phones

- ^ Bradley, Tony (February 2, 2015). «Office Online vs. Office 365: What’s free, what’s not, and what you really need». PC World. Archived from the original on July 24, 2017. Retrieved July 16, 2020.

- ^ Ansaldo, Michael (September 28, 2017). «Microsoft Office Online review: Work with your favorite Office formats for free». PC World. Retrieved October 31, 2019.

- ^ «Differences between using a document in the browser and in Word». Office Support. Microsoft. Archived from the original on November 7, 2017. Retrieved November 1, 2017.

- ^ a b «Password protect documents, workbooks, and presentations». Microsoft Office website. Microsoft. Retrieved April 24, 2013.

- ^ «How to Restrict Editing in Word 2010/2007». Trickyways. June 22, 2010. Retrieved April 24, 2010.

- ^ «How safe is Word encryption. Is it secure?». Oraxcel.com. Archived from the original on April 17, 2013. Retrieved April 24, 2013.

- ^ Cameron, Janet (September 1984). «Word Processing Revisited». BYTE (review). p. 171. Retrieved October 23, 2013.

- ^ Manes, Stephen (February 21, 1984). «The Unfinished Word». PC Magazine. p. 192. Retrieved October 19, 2021.

- ^ McNeill, Dan (December 1987). «Macintosh: The Word Explosion». Compute!’s Apple Applications. pp. 54–60. Retrieved September 14, 2016.

- ^ Nimersheim, Jack (December 1989). «Compute! Specific: MS-DOS». Compute!. pp. 11–12.

- ^ «Data Stream». Next Generation. No. 21. Imagine Media. September 1996. p. 21.

- ^ Opus Development Postmortem

- ^ «Microsoft Word 1.x (Windows) – Stats, Downloads and Screenshots :: WinWorld». WinWorld. Retrieved July 3, 2016.

- ^ Shustek, Len (March 24, 2014). «Microsoft Word for Windows Version 1.1a Source Code». Retrieved March 29, 2014.

- ^ Levin, Roy (March 25, 2014). «Microsoft makes source code for MS-DOS and Word for Windows available to public». Official Microsoft Blog. Archived from the original on March 28, 2014. Retrieved March 29, 2014.

- ^ a b «Office 14». Office Watch. June 1, 2007.

For the sake of superstition the next version of Office won’t be called ’13’.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Marshall, Martin (January 8, 1990). «SCO Begins Shipping Microsoft Word 5.0 for Unix and Xenix». InfoWorld. p. 6. Retrieved May 20, 2021.

- ^ «Microsoft Word: SCO announces Word for Unix Systems Version 5.1». EDGE: Work-Group Computing Report. March 11, 1991. p. 33. Retrieved May 20, 2021 – via Gale General OneFile.

Further readingEdit

- Tsang, Cheryl. Microsoft: First Generation. New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. ISBN 978-0-471-33206-0.

- Liebowitz, Stan J. & Margolis, Stephen E. Winners, Losers & Microsoft: Competition and Antitrust in High Technology Oakland: Independent Institute. ISBN 978-0-945999-80-5.

External linksEdit

- Microsoft Word – official site

- Find and replace text by using regular expressions (Advanced) — archived official support website

Background

Back in the late 80’s early 90’s I wrote some software called Rendezvous and sold it as shareware. I wrote it in Clipper (a dBase III compiler). It’s purpose was generally for lead generation and outbound telemarketing. Telemarketing using databases was relatively new at the time. For general lead processing one of the better strategies was to call the prospective customer, follow up immediately with a brochure or letter and then call them back in few days hopefully before your letter got thrown in the bin. Being pre-Windows you had to construct your printout using printer control codes etc; a nightmare in the days of dot matrix, daisy wheel, line printers and soon laser and ink jet printers.

The dominant word processor at the time was WordPerfect; it had an incredibly powerful merge language and an ever increasing array of printer drivers, so armed with a WordPerfect SDK I entered the world of document generation, and I rewrote my Rendezvous program to work with WordPerfect. My connection with WordPerfect for document generation lasted for many years, but WordPerfect was a company that was slow to embrace Windows and staffed by engineers rather than marketers. Much to the disappointment of many people at the time, Microsoft Word soon came to dominate.

For authors of document generation systems the transition to Microsoft Word was a difficult time. With Word you had to live with a very very basic mail merge facility and some WordBasic. It wasn’t until VBA came along in 1997 that things improved slightly – but only slightly. The WordPerfect merge language was truly superior; you could do most anything with it albeit in a clumsy macro sort of way. But one of the strong features for document generation automation was that the logic for creating documents was embedded in the document template. Developers (or End Users) could create a data source (called a WordPerfect Secondary file, which with some tweaking could in include data from multiple tables), and could create templates called Primary files. Because of this Word’s popularity with users meant that no matter how much harder it was to automate the generation of complex documents, for everyday use it was so much easier than WordPerfect – Word hastened the demise of specialist word processing operator. The fact that users were no longer specialists, document generation was in large measure handed over to developers who controlled document automation from outside the document. Today document generation is mostly in the hands of large developer-centric organisations. This leaves the smaller developer somewhat in a quandary of how to generate documents from their custom software in a financially painless way for their clients.

For the Access developer where are we now.

Microsoft Access reports

In many cases a Microsoft Access Report is all that it needed, especially if there is never any need to manually edit a resultant document. It can be printed or saved to PDF.

Export to Word

An editable document can be created by exporting an Access report to Word. This can be done two ways:

Interactively

By selecting the appropriate action from the Ribbon.

This will create an RTF formatted report named the same as the report it was based on and saved in the user’s document folder

Using VBA code

Using the Northwind database as an example the code might be:

[sourcecode language=”VB” gutter=”false”]

DoCmd.OpenReport «Invoice», acViewPreview, , _

«[Order ID]=» & Me.[Order ID]

DoCmd.OutputTo acOutputReport, «Invoice», acFormatRTF, _

CurrentProject.Path & «Inv» & Me.[Order_ID] & «.rtf», True

[/sourcecode]

This gives you control of the name of the document and its location, you can even force Word to accept it as a Word .doc file just by naming the output as .doc

[sourcecode language=”VB” gutter=”false”]

DoCmd.OpenReport «Invoice», acViewPreview, , _

«[Order ID]=» & Me.[Order ID]

DoCmd.OutputTo acOutputReport, «Invoice», acFormatRTF, _

CurrentProject.Path & «Inv» & Me.[Order_ID] & «.doc», True

[/sourcecode]

My favourite though is to allow the user to choose the name and location by outputting to a .dot file in the user’s temporary folder.

[sourcecode language=”VB” gutter=”false”]

DoCmd.OpenReport «Invoice», acViewPreview, , _

«[Order ID]=» & Me.[Order ID]

DoCmd.OutputTo acOutputReport, «Invoice», acFormatRTF, _

Environ(«temp») & «Inv» & Me.[Order_ID] & «.dot», True

[/sourcecode]

No matter how you cut it though, there are problems with this. The RTF is an old Microsoft proprietary format which Microsoft abandoned in terms of development after 2008. It lacks styles, lists etc, so the output from Access is not at all MS Word-centric, in addition (or subtraction) the export from Access does not include the graphics and charts from the report, so even just logos on letters, invoices etc are a problem; and similarly subreports are not included so only the main report is exported. With the RTF export formatting often changes, especially at the end of the report.

Essentially data for exporting a report to a Word document needs to be flat, with one table, or one query providing the data. There can be many records on a page.

Word Mail Merge

Another alternative that is also relatively easy is to use Word mail merge, A merge template document is created and then merged with data which can be interactively directly from a table or a query.

Merge is very good for multiple form letters, address labels for envelopes or even email. The process and results are very different to Exporting to Word.

The steps for mail merge are:

- Set up a data set, a table, a query, address list or a file CSV, Tab etc.

- Create a form letter and connect the data to it

- Add placeholders for the merge fields, and save the merge template

- Connect the form letter to the data set (table, query, file)

- Preview and perform the merge

The advantages of Mail merge over Exporting to Word include being able to use the full feature set of Word, styles, graphics (but not dynamic charts), and intelligent Word fields, conditional, including boilerplate assembly.

It is possible to use VBA and Word Automation to automate a mail merge such as:

[sourcecode language=”VB” gutter=”false”]

Dim objWord As Word.Document

Set objWord = GetObject(«C:MyMerge.doc», «Word.Document»)

objWord.Application.Visible = True

‘ Set the mail merge data source as the Northwind database.

objWord.MailMerge.OpenDataSource _

Name:=»C:Program FilesMicrosoft » & _

«OfficeOfficeSamplesNorthwind.mdb», _

LinkToSource:=True, _

Connection:=»TABLE Customers», _

SQLStatement:=»SELECT * FROM [Customers]»

‘ Execute the mail merge.

objWord.MailMerge.Execute

[/sourcecode]

Word Mail Merge is generally based on one record per document, so for example an Invoice like the one in Northwind would be very hard to create, and more complex structures impossible. But on the plus side you can make the documents attractive.

Populate book marks with data with VBA

Another way of creating documents is to use Word documents with Bookmarks. The basic idea with this is to create a Word document and insert named bookmarks where data needs to appear, and then using Word Automation to open the document, find the bookmarks and insert the required text at each bookmark. You can also insert other structures such as tables, so an Invoice like the one in the Northwind Invoice can be created.

An advantage of this is the full range of Word formatting features are available. Because the data is driven by programming code “pushing” data to the form, data can come from multiple data sets, eg invoice headers and invoice lines controlled by programming code. The disadvantage of this though is the amount of programming code needed to achieve a complex document and the general detachment of the template from the data can make the document more difficult to maintain. Often Add-Ins are used to make the insertion of bookmarks into the template easier for users (and developers). code, and where the users is not given so much say.

The basic VBA code for this is:

[sourcecode language=”VB” gutter=”false”]

Dim objWord As Word.Document

Set objWord = GetObject(«C:MyTemplate.docx», «Word.Document»)

objWord.Application.Visible = True

With objWord.ActiveDocument.Bookmarks

.Item(“Bookmarkname”).Range.Text = “Data to insert”

… etc etc

End With

[/sourcecode]

Custom Document Properties and Fields

Word comes with a number of predefined Document Properties such as Author, Pages, etc. From the File – Info – Properties – Advanced Properties, you can view the inbuilt properties and assign values to them, and you can create custom properties and assign the type and value to them and add them to the document.

The basic idea of using custom documents is that you create these properties and then using Insert QuickParts – Fields – DocProperty and choose the property you wish to insert.

From Access you would use something like the following code to populate the document with data.

[sourcecode language=”VB” gutter=”false”]

Dim objWord As Word.Document

Set objWord = GetObject(«C:MyTemplate.docx», «Word.Document»)

objWord.Application.Visible = True

With objWord.ActiveDocument.CustomDocumentProperties

Add Name:=»CustomerNumber», _

LinkToContent:=False, _

Type:=msoPropertyTypeNumber, _

Value:=1000

End With

[/sourcecode]

An advantage of using document properties over bookmarks is that you can refer to a document property from many places in the document, so if data needs to repeated multiple time, you only have to update the property value once and everything update. With Bookmarks you have have a differently named bookmark for every location, and creating multiple record documents can be problematic

As in using Bookmarks, the management of this can get quite complex. Personally I do not like Access to do so much work other than just providing the data. To achieve this it is possible of course to pull the data from inside Word, and link to the data in Access (or other databases), and similarly populate bookmarks or document properties, however this generally means that the report selection is handled from with Word, however since my applications are usually driven from Access I usually prefer it the other way around. But this is an option.

Visual Studio and specialist third party .NET libraries

Products such as Aspose provide tools for building documents, and generally this is less of an option for Access developers.

Specialist document merging systems

Products such as HotDocs and Windward are probably the most likely ones than an Access developer is likely to use.

The disadvantage of these systems is the cost and potential complexity of integration into an Access application. I have not used HotDocs, but I have used Windward extensively, and Windward is my favoured program for document generation. However they are generally too expensive for simple projects. They both have an Add-In for Microsoft Word which appears on a Word Ribbon. Options from the Ribbon allow connection to a data source (files or various databases), which allows a document to be marked up using drag and drop, and that process is quite easy so end users can generally feel comfortable with them, but also can handle more complex operation. So creation of templates can be with the user, or by or in collaboration with the developer. The generation of documents can occur directly from within Word, but generally for anything serious they require a server component, which may be on a local or remote machine. I am familiar with Windward as it supports XML and allows XPath statements and functions for accessing data. Both products can use SQL statements when connected to SQL databases, and ODBC data sources.

HotDocs is more likely to be used in applications where there is more human interaction in the document assembly. This perhaps makes it a stronger contended for legal merging where there is considerable individuality about the documents but nonetheless based on a precedent document. HotDocs also works with WordPerfect which was my previous favourite document generating platform.

Windward is very good for complex documents and can include dynamic charts, and boilerplating of parts of the document.

Both products generate Word documents which are standalone, discrete from the original data they were based on..

The market for document generation is always widening, and a relatively new class of products CCM (Customer Communication Management) which often are more oriented to the generation of digital content, also can produce Word documents. Products of this type include OpenText, Ecrion, Kofax, and many more.

Microsoft Word 2003 XML Markup and XSLT

When Microsoft released Word 2003, they entered into a brand new era of using XML as the underlying structure for Word documents in place of the Microsoft proprietary binary file .DOC format. One of the reason for this was customer demand for long term storage of documents in non-proprietary formats so that content could be readily accessed in the future. Microsoft gave no real tools for creating documents using XML, but did allow you to attach XML tags to documents, the major purpose of this was to allow extraction of data from a document, but also (perhaps unintentionally) opened the possibility of merging data with documents using XSLT, which meant that Word itself is not needed to create the finally merged document, other than to open, view and print it. Microsoft Word was never good being used as a server application however XSLT was available both on client side and server side of all the major operating systems. Microsoft without much fanfare released a command line too called the Microsoft Office Word 2003 WordML XSLT Inference Tool, which generated am XSLT template from the XML marked up document. With this you could use almost any XSLT processor to merge XML data and the template to create a Word .DOCX file.

There were two problems with this.

The XSLT file generated from the Microsoft Office Word 2003 XSLT Inference Tool. could not itself be opened by Word, nor opened intelligently from any other program. If you needed to make even minor edits to the template you really had to go back to the original source document and start the transformation process from scratch. Often it was necessary to manually edit the XSLT to get the desired results, so having to start from scratch each time could be quite an impost. But the fact that Microsoft had committed to this technology, and had provided some tools was an encouraging thing. I used this quite extensively until an additional problem popped up

The first problem was an annoyance, but the second a killer. In May 2007 Microsoft was successfully sued for infringing a patent regarding XML markup by the company i4i and it founder Michel Vulpe. As part of the settlement in 2010 Microsoft released an update as part of the normal Windows and Office updates to remove the XML tagging in Office 2003, and 2007 and was precluded from using the technology in Office 2010. Although XML is open, specific implementation of it can be subject to copyright.

Once an XSLT template had been created using the Word 2003 XSLT Inference tool though, it was still possible to generate a new document based on it, because Word was not again involved until after the document was generated, and that document was no longer dependant on the template or the data source. As soon as the document was opened in Word, the markup itself was removed with a helpful message from Microsoft, but that was already too late, the document had been populated with the data and the XSLT did its job. But it meant that these template could no longer be created, nor old ones edited.

Because an XSLT processor and not Word was used for the “merging” of the XML data with the XSLT template, the process was very useful for server side generation. Word like the other Office programs, are not suitable for running as server processes.

Word Content Controls

In Word 2007, Microsoft introduced Content Controls. Content Controls are a little like Word Fields. The various templates supplied with Microsoft Word 2007, 2010 and 2013 include Content Controls which prompt the user to add information from the keyboard Content Controls can also be bound/mapped to XML element forming part of the document file structure. Microsoft changed the layout of the Word DOCX file, so that rather than being directly an XML file it is a package of components, packaged and compressed together. To look at the file structure of a Word document the easiest way is to rename the document extension to .ZIP, and then open it with an archive package like WinZip, 7-Zip, WinRAR. In the Word 2003 XML document format, the document was itself only an XML conforming to the WordML XML vocabulary, graphics etc formed part of the document’s XML data. With the later version graphic files are saved in the package file and referenced by the content XML. Similarly you can add an XML document to the package, and you can then bind this to Content Controls. In Word 2013 Microsoft did some tweaking to the Content Controls and now they are far more useful for document generation.

See other blog article Document Generation using Word Content Controls

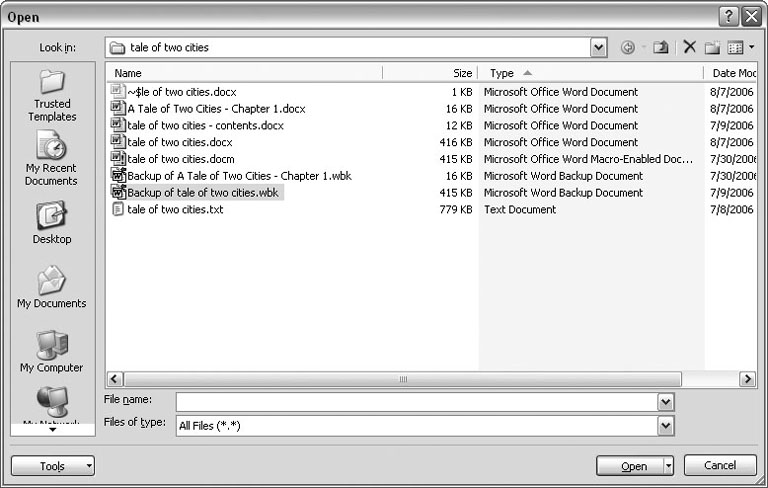

Chapter 1. Creating, Opening, and Saving Documents

Every Word project you createâwhether itâs a personal letter, a TV sitcom script, or a thesis in microbiologyâbegins and ends the same way. You start by creating a document, and you end by saving your work. Sounds simple, but to manage your Word documents effectively, you need to know these basics and beyond. This chapter shows you all the different ways to create a new Word documentâlike starting from an existing document or adding text to a predesigned templateâand how to choose the best one for your particular project.

Youâll also learn how to work faster and smarter by changing your view of your document. If you want, you can use Wordâs Outline view when youâre brainstorming, and then switch to Print view when youâre ready for hard copy. This chapter gets you up and running with these fundamental tools so you can focus on the important stuffâyour words.

Tip

If youâve used Word before, then youâre probably familiar with opening and saving documents. Still, you may want to skim this chapter to catch up on the differences between this version of Word and the ghosts of Word past. Youâll grasp some of the big changes just by examining the figures. For more detail, check out the gray boxes and the notes and tipsâlike this one!

Launching Word

The first time you launch Word after installation, the program asks you to confirm your name and initials. This isnât Microsoftâs nefarious plan to pin you down: Word uses this information to identify documents that you create and modify. Word uses your initials to mark your edits when you review and add comments to Word documents that other people send to you (Section 16.3).

You have three primary ways to fire up Word, so use whichever method you find quickest:

-

Start menu. The Start button in the lower-left corner of your screen gives you access to all programs on your PCâWord included. To start Word, choose Start â All Programs â Microsoft Office â Microsoft Office Word. -

Quick Launch toolbar. The Quick Launch toolbar at the bottom of your screen (just to the right of the Start menu) is a great place to start programs you use frequently. Microsoft modestly assumes that youâll be using Word a lot, so it usually installs the Word icon in the Quick Launch toolbar. To start using Word, just click the W icon, and voilá!Tip

When you donât see the Quick Launch toolbar, hereâs how to display it: On the bar at the bottom of your screen, right-click an empty spot. From the menu that pops up, choose Toolbars â Quick Launch. When youâre done, icons for some of your programs appear in the bottom bar. A single click fires up the program.

-

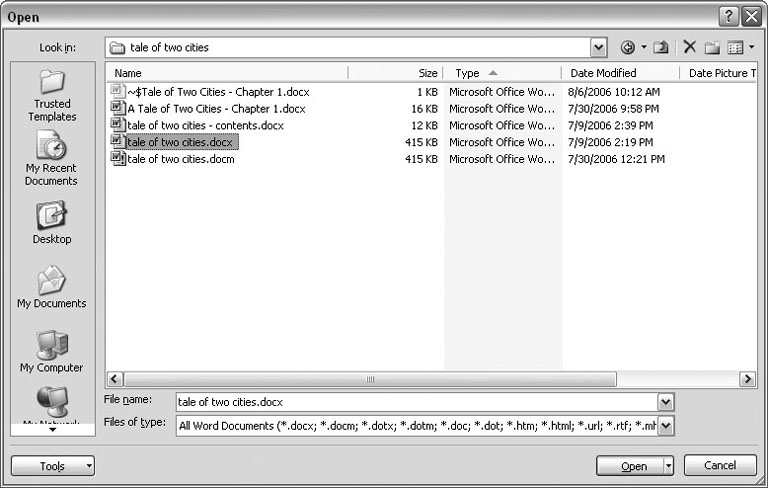

Opening a Word document. Once youâve created some Word documents, this method is fastest of all, since you donât have to start Word as a separate step. Just open an existing Word document, and Word starts itself. Try going to Start â My Recent Documents, and then, from the list of files, choose a Word document. You can also double-click the documentâs icon on the desktop or wherever it lives on your PC.

Tip

If you need to get familiar with the Start menu, Quick Launch toolbar, and other Windows features, then pick up a copy of Windows XP: The Missing Manual, Second Edition or Windows Vista: The Missing Manual.

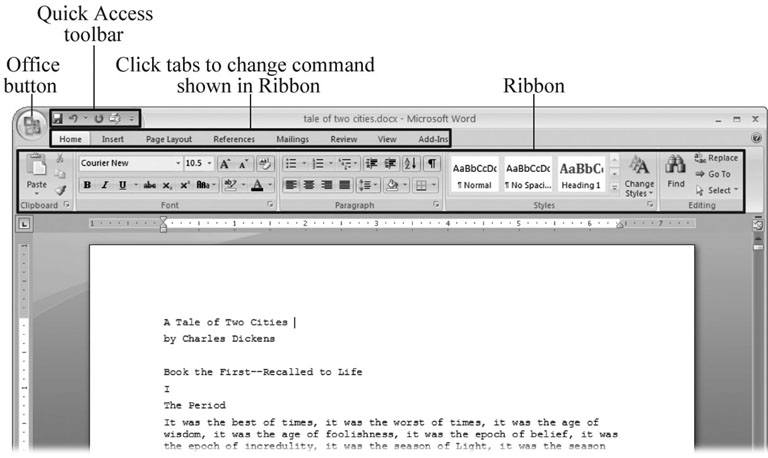

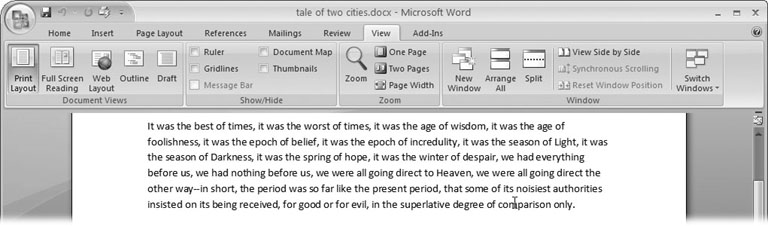

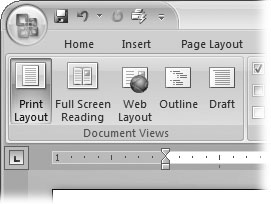

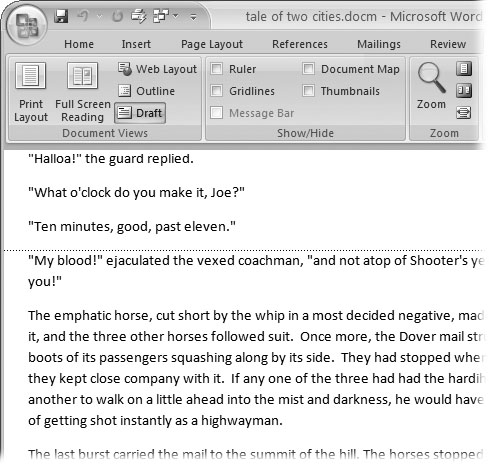

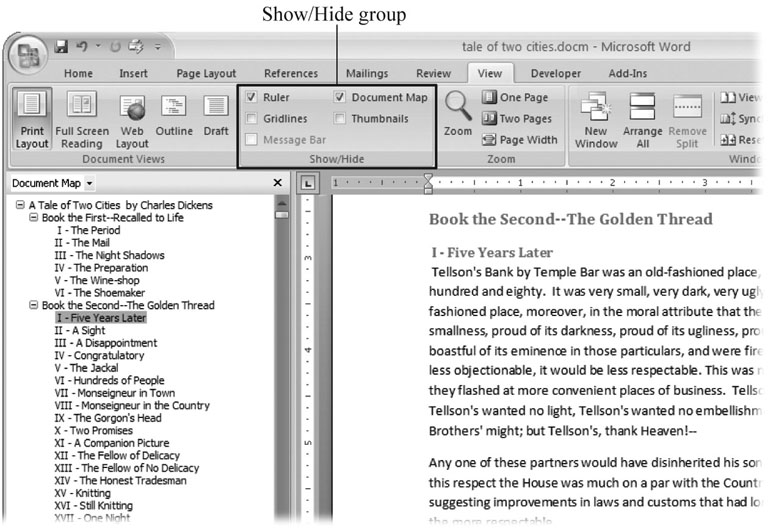

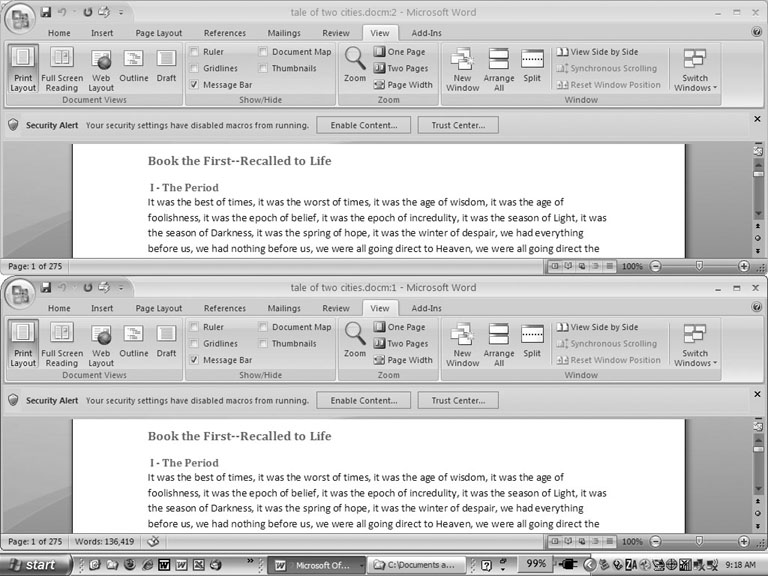

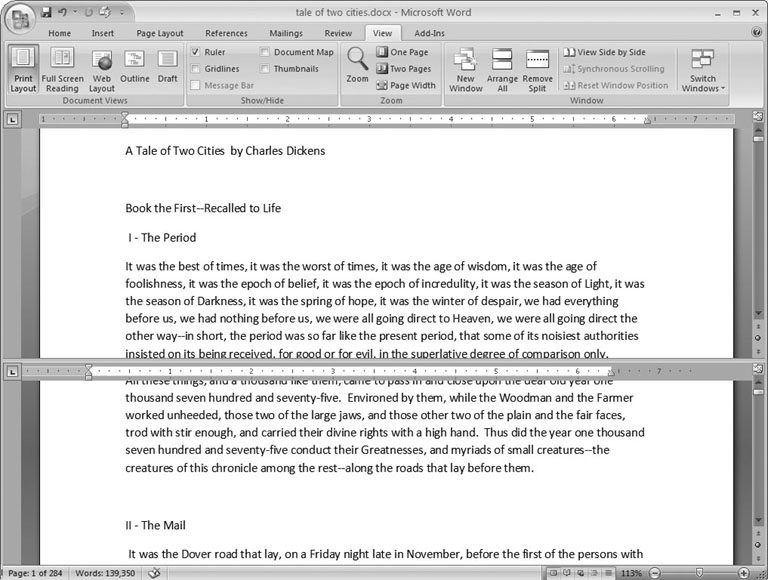

So, what happens once youâve got Wordâs motor running? If youâre a newcomer, youâre probably just staring with curiosity. If youâre familiar with previous versions of Word, though, you may be doing a double take (Figure 1-1). In Word 2007, Microsoft combined all the old menus and toolbars into a new feature called the ribbon. Click one of the tabs above the ribbon, and you see the command buttons change below. The ribbon commands are organized into groups, with the name of each group listed at the bottom. (See Figure 1-1 for more detail on the ribbon.)

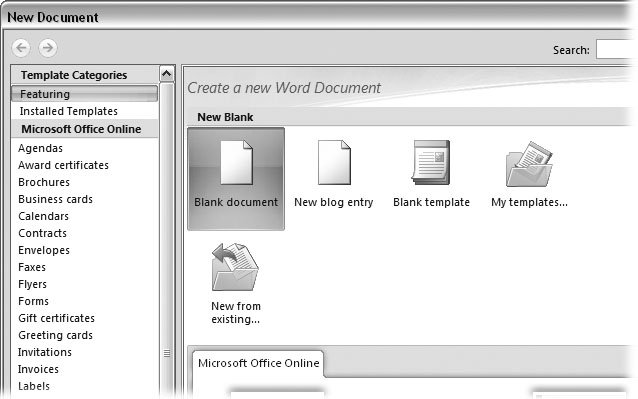

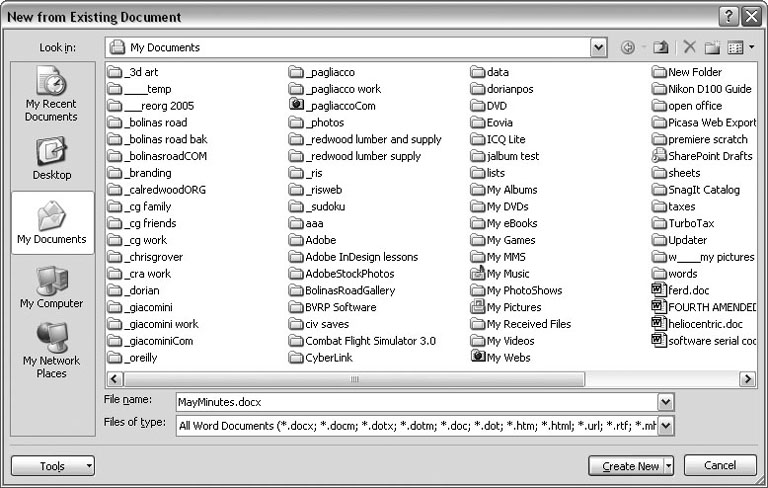

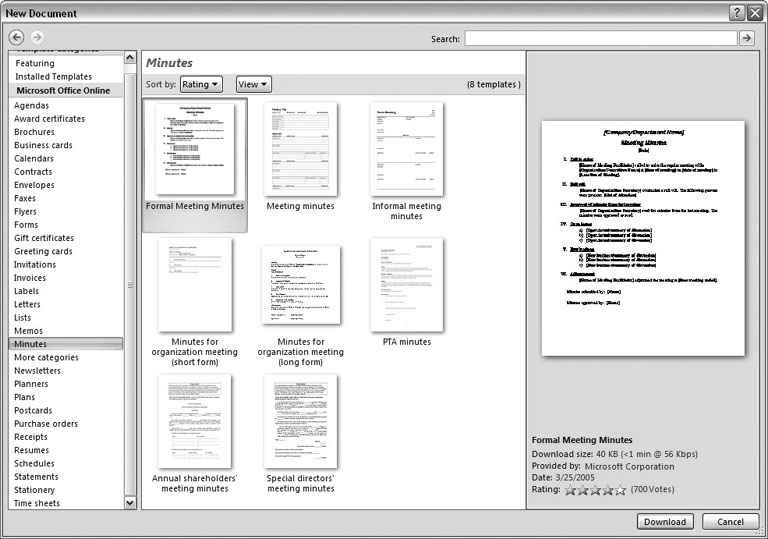

Creating a New Document

When you start Word without opening an existing document, the program gives you an empty one to work in. If youâre eager to put words to page, then type away. Sooner or later, though, youâll want to start another new document. Word gives you three ways to do so: