From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

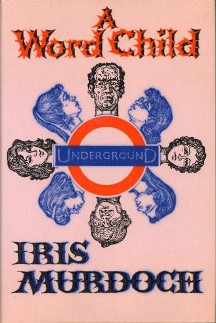

Cover of the first edition |

|

| Author | Iris Murdoch |

|---|---|

| Cover artist | Christopher Cornford |

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Language | English |

| Publisher | Chatto and Windus |

|

Publication date |

1975 |

| Media type | Print (Hardback & Paperback) |

| Pages | 392pp |

A Word Child is the 17th novel by Iris Murdoch.[1]

First published in 1975 by Chatto and Windus, A Word Child charts the trials and tribulations of the title character, the «word child», Hilary Burde as he attempts to recover his soul from the misery of his troubled past.[2] Filled in the usual Murdoch style with an array of colourful, fully rounded characters who people Hilary’s world, the novel is a complex and thoughtful exploration of the possibility and meaning of redemption, the nature of human memory, and the possibility of love for the tarnished soul. By turns stirring, witty, painful and joyous, the novel was received to great critical acclaim on its release.

References[edit]

- ^ Bromwich, David (24 August 1975). «Iris Murdoch’s New Novel and Old Themes». The New York Times. Retrieved 29 December 2020.

- ^ «Book Reviews, Sites, Romance, Fantasy, Fiction». Kirkus Reviews. Kirkus Reviews. 18 August 1975. Retrieved 29 December 2020.

- A Word Child

-

infobox Book |

name = A Word Child

title_orig =

translator =image_caption =

author =Iris Murdoch

illustrator =

cover_artist =

country = United Kingdom

language = English

series =

genre = Novel

publisher = Chatto and Windus

release_date = 1975

english_release_date =

media_type = Print (Hardback & Paperback)

pages = 392pp

isbn =

preceded_by =

followed_by =«A Word Child» is the 17th novel by Iris Murdoch.

First published in 1975 by Chatto and Windus, «A Word Child» charts the trials and tribulations of the title character, the «word child», Hilary Burde as he attempts to recover his soul from the misery of his troubled past. Filled in the usual Murdoch style with an array of colourful, fully rounded characters who people Hilary’s world, the novel is a complex and thoughtful exploration of the possibility and meaning of redemption, the nature of human memory, and the possibility of love for the tarnished soul. By turns stirring, witty, painful and joyous, the novel was received to great critical acclaim on its release.

Wikimedia Foundation.

2010.

Look at other dictionaries:

-

child — n pl chil·dren 1: a son or daughter of any age and usu. including one formally adopted compare issue ◇ The word child as used in a statute or will is often held to include a stepchild, an illegitimate child, a person for whom one stands in loco… … Law dictionary

-

Child — This article is about the human child . For other uses, see Child (disambiguation). Children at a primary school in Paris … Wikipedia

-

Child — This ancient and distinguished surname of Anglo Saxon origin, with several entries in the Dictionary of National Biography , and having no less than twelve Coats of Arms, originated as a nickname with various possible application from the Olde… … Surnames reference

-

Child Come Away — Single by Kim Wilde B side Just Another Guy Released 4 Octo … Wikipedia

-

WORD (revista) — Desarrollo Editor Donna Lillian Circulación ISSN ISSN 0043 7956 … Wikipedia Español

-

Child Rebel Soldier — Genres Alternative hip hop Years active 2007–present Labels 1st 15th, GOOD, Star Trak Members … Wikipedia

-

Child pornography laws in Australia — state that all sexualised depictions of children under the age of 18 (Under 16 in some states.) (or who appear to be under that age) are illegal and it has banned photographs of women with an A breast cup size even in their late 20s as… … Wikipedia

-

Child Psychology (song) — Child Psychology is a 1998 single by Black Box Recorder. It was featured on the album England Made Me. The song features a mixture of spoken word and a sung chorus. The spoken word tells of various incidents from childhood, including refusing to… … Wikipedia

-

Child of Winter — (Christmas Song)/Susie Cincinnati Single by The Beach Boys Released December 23, 1974 … Wikipedia

-

Child health nursing — is an area of nursing and medical practice with a focus on providing holistic care to infants, children and adolescents. It differs from pediatrics, in that the emphasis in pediatrics is ill health and the alleviation of symptoms or disease.One… … Wikipedia

The ‘word child’ of the title is Hilary Burde, our narrator. Following an unhappy childhood Hilary’s future prospects looked bleak, until he discovered a passion for words and languages and embarked on a promising academic career at Oxford. However, when we first meet Hilary at the beginning of the novel, he is working as a low grade civil servant in London. We don’t know at first why he left Oxford, but we are given hints that he had been involved in some kind of scandal there – and when Gunnar Jopling, a figure from his past, comes to work in Hilary’s office building, everything starts to become clear.

The book has an interesting structure, with each chapter headed by a day of the week. Hilary has tried to establish order and routine in his life by having certain things that he always does on certain days of the week (dinner with friends on Thursday, visiting his sister on Saturdays, for example) and the novel follows him as this monotonous cycle of events is gradually thrown into disarray. Murdoch’s writing never becomes over descriptive or flowery, yet she manages to convey vivid images of the stations on the London Underground, the yellow fog that hangs over the Thames, the Peter Pan statue in Kensington Gardens. She also gives an amusingly accurate portrayal of daily office life, where Hilary is relentlessly teased by two of his colleagues, and there are other moments of humour involving Hilary’s lodger, Christopher.

Hilary himself is not an easy character to like. He controls every aspect of his sister Crystal’s life and the way he behaves towards his poor girlfriend, Thomasina, is even worse. And yet I could still empathise with him at times because his dysfunctional relationships and desperate attempts to stay in control are signs of the unhappiness and inner turmoil from which he’s suffering. I really wanted Hilary and the other main characters to have a happy ending and although I’m obviously not going to tell you whether they did or not, I did think the ending was stunning: dramatic, surprising and very satisfying.

I enjoyed this book very much and loved Murdoch’s insights into topics such as redemption, forgiveness and moving on after a tragedy. It was such a surprise because I wasn’t expecting something so accessible and readable. I’d recommend A Word Child to anyone who may be wondering where to begin with Iris Murdoch.

I’ve been away on my hols, hence the rather odd selection of reading matter in the last two reviews, so here you have an image of what I’d call “Extreme Iris Murdoch reading” – sat in the middle of a lava field in Fuerteventura (that’s my husband heading off to look for some birds).

If you’re doing the readalong or even selected books along with me Or some time afterwards, do share how you’re getting on and which have been your favourites so far.

Iris Murdoch – “A Word Child”

(31 December 2018)

So I remembered Hilary Burde as a gente, slightly shambliing, slight figure, for no discernible reason at all, rather than a big bruiser who keeps bashing women and frightening them. Why, I’m really not sure, as all the information is given to us in the book. We gradually come to realise Hilary is a man who keeps to a strict routine and regime in order to stave off madness, caused partly by his accidental – or not – killing of his friend Gunnar’s wife, with whom he was having an affair. So he has different days for different friends, keeps everything compartmentalised, hates his office-mates, worships his sister, tolerates her suitor Arthur, and puts up with his fey lodger, Christopher. Then a mysterious woman called Biscuit starts following him around and he finds out through office gossip that Gunnar is back … with a new wife.

It is a savagely funny book in that the repetitions and echoings and patterns come with a sort of black irony. The office scenes are brilliant and just right and of course I love Hilary’s circlings of the Circle Line (what a true tragedy it is that the platform bars have long gone and you can’t even go right round on the Circle Line any more!). The theme is set on page 4: “There was nothing here to love” – Hilary has no love in his life and rebuffs any that tries to form. This circles back at the end: “I had almost systematically destroyed his respect and affection and finally driven him away” (p. 387)

Is there an enchanter? Is it Hilary himself, with whom Gunnar and Lady Kitty are obsessed, who he admits three women want him to arrange for them to have children, two with him, and who inspires love? Only Christopher seems to escape him. And surely Christopher is our saint, accepting violence with meekness and being kind (although Jimbo is also an agent of positivity and attention with his taxis and presents. Are we saying the young are going to save the world?). He’s described as being Christ-like at one point. Mr Osmund also gives Hilary his full attention so is perhaps a Saint figure, as is patient and unworldly Arthur Fisch, who absorbs Hilary’s terrible story (although Hilary tries not to pass on his second love to Crystal, she’s still bothered by an atmosphere between them, so it clearly hasn’t worked). Arthur’s is also a “muddler” with a lot of lame ducks, reminding us of Tallis and just as humble: “I think we should just be kind to each other” (p. 87) and, later, “I think one should try to stick to simplicity and truth” (p. 290). Hilary describes him as the perfect IM saint:

Arthur was a little untalented unambitious man, destined to spend his life in a cupboard, but there was in a quite important sense no harm in him. He was kind, guileless, harmless and he had had the wit to love Crystal, to see Crystal, to see her value. (p. 287)

Tommy owns the crowded room full of knick-knacks that has to exist in every book. Clifford has a more refined version with Indian miniatures and tiny bookcases. Hilary gives Biscuit a black pebble which she later flings back at him. For water, we have the endless rain and dripping umbrellas, and of course the Thames as well as the Serpentine and Boating Lake. There’s no pursuit in the dark or standing in gardens looking through into houses, but Hilary does chase Biscuit down the Bayswater Road. In terms of siblings, we have Hilary and Crystal, but Clifford also had a sister, who died. Hair isn’t such a big theme but Laura has an unsuitably flowing grey mane, Biscuit a long black plait Kitty sophisticated brown layers and Crystal a frizzy fuzz last seen in “Sacred and Profane”.

A new theme coming through seems to be the quest, which Hilary talks of on p. 200: “I now had a task. I was like a Knight with a quest. I needed my chastity now; I needed my aloneness”. The feeling of feuds and owing, when Hilary says, “I owe Gunnar a child” reminds me of “The Green Knight” and brings the patterning into sharp relief. There’s one of IM’s horrible prefigurings when Hilary is talking to Kitty on the jetty – “I felt now as if I were plunging around in the mud” (p. 243) and one that could be from “A Severed Head”: “Powers which I had offended were gathering to destroy me” (p. 323).

The humour is there, but savage as I said: “Not to have been born is undoubtedly best, but sound sleep is second best” (p. 16) feels like a good example. IM is funny about Christopher’s happenings and has Hilary be hilariously vile about Tommy’s knitting, which she does because he once said he liked it, but makes him want to vomit.

In echoes with other books, there’s yet another set of telephone entrails (“The Black Prince” and “A Fairly Honourable Defeat” have them and I’m sure there are more in “The Book and the Brotherhood”). The parks of London of course echo several other books, as does the leap into the Thames at the end. Hilary’s three women demanding babies, echo Edgar’s three women planning to visit at he end of “The Sacred and Profane Love Machine”.

What will become of Hilary at the end? Without a set of fake epilogues to contain him, this latest first-person narrator seems to drift away from us in this stranger than I remember book.

Please either place your review in the comments, discuss mine or others’, or post a link to your review if you’ve posted it on your own blog, Goodreads, etc. I’d love to know how you’ve got on with this book and if you read it having read others of Murdoch’s novels or this was a reread, I’d love to hear your specific thoughts on those aspects, as well as if it’s your first one!

If you’re catching up or looking at the project as a whole, do take a look at the project page, where I list all the blog posts so far.

Princeton’s WordNetRate this definition:4.5 / 2 votes

-

child, kid, youngster, minor, shaver, nipper, small fry, tiddler, tike, tyke, fry, nestlingnoun

a young person of either sex

«she writes books for children»; «they’re just kids»; «`tiddler’ is a British term for youngster»

-

child, kidnoun

a human offspring (son or daughter) of any age

«they had three children»; «they were able to send their kids to college»

-

child, babynoun

an immature childish person

«he remained a child in practical matters as long as he lived»; «stop being a baby!»

-

childnoun

a member of a clan or tribe

«the children of Israel»

WiktionaryRate this definition:3.3 / 4 votes

-

childnoun

A daughter or son.

-

childnoun

A person who is below the age of adulthood; a minor .

Go easy on him: he is but a child.

-

childnoun

A data item, process or object which has a subservient or derivative role relative to another data item, process or object.

The child node then stores the actual data of the parent node.

Samuel Johnson’s DictionaryRate this definition:0.0 / 0 votes

-

CHILDnoun

in the plural Children.

Etymology: cild , Sax.

1. An infant, or very young person.

In age, to wish for youth is full as vain,

As for a youth to turn a child again.

John Denham.We should no more be kinder to one child than to another, than we are tender of one eye more than of the other.

Roger L’Estrange.The young lad must not be ventured abroad at eight or ten, for fear of what may happen to the tender child; though he then runs ten times less risque than at sixteen.

John Locke.The stroak of death is nothing: children endure it, and the greatest cowards find it no pain.

William Wake, Prep for Death.2. One in the line of filiation, opposed to the parent.

Where children have been exposed, or taken away young, and afterwards have approached to their parents presence, the parents, though they have not known them, have had a secret joy, or other alteration thereupon.

Francis Bacon, Nat. Hist. №. 239.I shall see

The winged vengeance overtake such children.

William Shakespeare, K. L.So unexhausted her perfections were,

That for more children, she had more to spare.

Dryden.He in a fruitful wife’s embraces old,

A long increase of children’s children told.

Joseph Addison, Ovid’s Met.3. In the language of Scripture.One weak in knowledge. Isa. x.

19. 1 Cor. xiii. 11.1 John, ii. 13.

Matt. xvii. 3, 4.

How is he numbered among the children of God, and his lot is among the saints!

Wisdom, v. 5.Ye are all the children of God, by faith in Jesus Christ. Gal. iii. 26.

Augustin Calmet.4. A girl child.

Mercy on’s, a bearne! a very pretty bearne!

A boy, or child, I wonder!

William Shakespeare, Winter’s Tale.5. Any thing, the product or effect of another.

Macduff, this noble passion,

Child of integrity, hath from my soul

Wip’d the black scruples.

William Shakespeare, Macbeth.6. To be with Child. To be pregnant.

If it must stand still, let wives with child,

Pray that their burthen may not fall this day,

Lest that their hopes prodigiously be crost.

William Shakespeare, K. John. -

To Childverb

To bring children.

Etymology: from the noun.

The spring, the summer,

The childing autumn, angry winter change

Their wonted liveries.

William Shakespeare, Midsummer Night Dream.As to childing women, young vigorous people, after irregularities of diet, in such it begins with hæmorrhages.

Arbuthnot.

Webster DictionaryRate this definition:3.0 / 4 votes

-

Childnoun

a son or a daughter; a male or female descendant, in the first degree; the immediate progeny of human parents; — in law, legitimate offspring. Used also of animals and plants

-

Childnoun

a descendant, however remote; — used esp. in the plural; as, the children of Israel; the children of Edom

-

Childnoun

one who, by character of practice, shows signs of relationship to, or of the influence of, another; one closely connected with a place, occupation, character, etc.; as, a child of God; a child of the devil; a child of disobedience; a child of toil; a child of the people

-

Childnoun

a noble youth. See Childe

-

Childnoun

a young person of either sex. esp. one between infancy and youth; hence, one who exhibits the characteristics of a very young person, as innocence, obedience, trustfulness, limited understanding, etc

-

Childnoun

a female infant

-

Childverb

to give birth; to produce young

-

Etymology: [AS. cild, pl. cildru; cf. Goth. kilei womb, in-kil with child.]

FreebaseRate this definition:4.3 / 6 votes

-

Child

Biologically, a child is a human between the stages of birth and puberty. Some biological definitions of child include the fetus, as being an unborn child. The legal definition of child generally refers to a minor, otherwise known as a person younger than the age of majority.

Child may also describe a relationship with a parent or, metaphorically, an authority figure, or signify group membership in a clan, tribe, or religion; it can also signify being strongly affected by a specific time, place, or circumstance, as in «a child of nature» or «a child of the Sixties».

Chambers 20th Century DictionaryRate this definition:3.0 / 2 votes

-

Child

chīld, n. an infant or very young person: (Shak.) a female infant: one intimately related to one older: expressing origin or relation, e.g. child of the East, child of shame, child of God, &c.: a disciple: a youth of gentle birth, esp. in ballads, &c.—sometimes Childe and Chylde: (pl.) offspring: descendants: inhabitants:—pl. Chil′dren.—ns. Child′-bear′ing, the act of bringing forth children; Child′bed, the state of a woman brought to bed with child; Child′birth, the giving birth to a child: parturition; Child′-crow′ing, a nervous affection with spasm of the muscles closing the glottis.—adj. Child′ed (Shak.), possessed of a child.—n. Child′hood, state of being a child: the time of one’s being a child.—adjs. Child′ing (Shak.), fruitful, teeming; Child′ish, of or like a child: silly: trifling.—adv. Child′ishly.—ns. Child′ishness, Child′ness, what is natural to a child: puerility.—adjs. Child′less, without children; Child′-like, like a child: becoming a child: docile: innocent.—n. Child′-wife, a very young wife.—Child’s play, something very easy to do: something slight.—From or Of a Child, since the days of childhood.—Second childhood, the childishness of old age.—With child, pregnant, e.g. Get with child, Be or Go with child. [A.S. cild, pl. cild, later cildru, -ra. The Ger. equivalent word is kind.]

U.S. National Library of MedicineRate this definition:5.0 / 1 vote

-

Child

A person 6 to 12 years of age. An individual 2 to 5 years old is CHILD, PRESCHOOL.

Editors ContributionRate this definition:0.0 / 0 votes

-

child

A person of a specific age defined in legislation.

A child is entitled to their innocence in life and develop and grow at a moderate rate.

Submitted by MaryC on March 14, 2020

Suggested ResourcesRate this definition:3.0 / 1 vote

-

child

The child symbol — In this Symbols.com article you will learn about the meaning of the child symbol and its characteristic.

Surnames Frequency by Census RecordsRate this definition:0.0 / 0 votes

-

CHILD

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, Child is ranked #6483 in terms of the most common surnames in America.

The Child surname appeared 5,237 times in the 2010 census and if you were to sample 100,000 people in the United States, approximately 2 would have the surname Child.

85.4% or 4,474 total occurrences were White.

5.6% or 297 total occurrences were of Hispanic origin.

5% or 264 total occurrences were Black.

1.6% or 86 total occurrences were of two or more races.

1.3% or 72 total occurrences were Asian.

0.8% or 44 total occurrences were American Indian or Alaskan Native.

Matched Categories

-

- Descendant

- Person

British National Corpus

-

Spoken Corpus Frequency

Rank popularity for the word ‘child’ in Spoken Corpus Frequency: #345

-

Written Corpus Frequency

Rank popularity for the word ‘child’ in Written Corpus Frequency: #650

-

Nouns Frequency

Rank popularity for the word ‘child’ in Nouns Frequency: #8

How to pronounce child?

How to say child in sign language?

Numerology

-

Chaldean Numerology

The numerical value of child in Chaldean Numerology is: 7

-

Pythagorean Numerology

The numerical value of child in Pythagorean Numerology is: 9

Examples of child in a Sentence

-

Anathi Ntozini:

An old man seating down is able to see far better than a child standing on top of a tree.

-

Jacqueline Dougé:

It’s going to have an impact on any child‘s physical and emotion health, so we need to turn it off and really engage with our kids and make sure that they’re okay.

-

Agent Dan Milstein:

This is just me, the Ukrainian agent, getting this, it has been difficult for some (players). Some guys find refuge by stepping on the ice and playing the game. … But could you imagine stepping on the ice and playing a competitive game thinking that your wife and your newborn child are at home unprotected?

-

Tracie Afifi:

We found almost half that enter the military in Canada had a history of child abuse.

-

Black Hawk:

If you treat a sick child like an adult and a sick adult like a child, everything usually works out pretty well.

Popularity rank by frequency of use

Translations for child

From our Multilingual Translation Dictionary

- аԥшқа, асабиAbkhaz

- kindAfrikaans

- ልጅ, ብላቴናAmharic

- طفل, ابن, ابنة, طفلة, ولدArabic

- лъимерAvaric

- uşaq, çağa, balaAzerbaijani

- балаBashkir

- дзіця́, рабёнакBelarusian

- дете́, ро́жбаBulgarian

- শিশু, চাইল্ডBengali

- minor, minored, bugelBreton

- nenCatalan, Valencian

- берChechen

- dítě, dceraCzech

- чѧдоOld Church Slavonic, Church Slavonic, Old Bulgarian

- ачаChuvash

- plentyn, plentyn dan oedWelsh

- børn, barnDanish

- KindGerman

- ɖevi, viEwe

- τέκνο, απότοκος, παιδί, ανήλικοςGreek

- infano, virinfano, infaninoEsperanto

- hija, niño, hijo, niña, infanteSpanish

- lapsEstonian

- sein, umeBasque

- کودک, فرزند, بچه, بچ, کرPersian

- lapsiobjekti, lapsiFinnish

- goneFijian

- barnFaroese

- enfantFrench

- bernWestern Frisian

- páiste, clannIrish

- pàisde, leanabhScottish Gaelic

- neno, nenaGalician

- બાળકGujarati

- ya’yaHausa

- יֶלֶד, בַּת, יַלְדָּה, בֵּןHebrew

- बच्चा, बेटा, बालक, शिशु, बेटी, बच्चीHindi

- gyerek, gyermekHungarian

- մանուկ, երեխա, զավակArmenian

- filia, infanteInterlingua

- anak, kanakIndonesian

- infanto, puero, filio, filiulo, infantulo, infantino, puerulo, puerino, filiinoIdo

- barnIcelandic

- figlia, bambino, bambina, figlioItalian

- 未成年, 子, 子供Japanese

- ბავშვიGeorgian

- балаKazakh

- meeraqKalaallisut, Greenlandic

- កូនKhmer

- ಹಸುಳೆ, ಮಗುKannada

- 어린이Korean

- بچووک, منداڵ, zarok, زارۆک, مناڵKurdish

- наристе, балаKyrgyz

- infans, filius, puer, filiaLatin

- KandLuxembourgish, Letzeburgesch

- ລູກ, ເດັກນ້ອຍ, ເດັກLao

- vaikasLithuanian

- bērnsLatvian

- pangoreMāori

- че́до, де́теMacedonian

- കുട്ടിMalayalam

- хүүхэдMongolian

- anak, انقMalay

- ibna, tfal, tifel, tiflaMaltese

- ကလေးBurmese

- kindDutch

- barnNorwegian Nynorsk

- mindreårig, barnNorwegian

- awééʼ, áłchíníNavajo, Navaho

- ਬੱਚਾPanjabi, Punjabi

- dziecko, dziecięPolish

- ماشوم, کوچنۍPashto, Pushto

- menina, filha, criança, menino, filhoPortuguese

- wamraQuechua

- uffant, unfant, iffaunt, affonRomansh

- copil, copilă, fiu, fiicăRomanian

- дитя́, ча́до, доче́рний, ребёнокRussian

- शिशु, बालकSanskrit

- ٻارSindhi

- mánnáNorthern Sami

- дијете, чедо, dijete, čedo, дете, deteSerbo-Croatian

- ළමයාSinhala, Sinhalese

- dieťaSlovak

- otrok, deteSlovene

- caruur, canugSomali

- fëmijëAlbanian

- ngwanaSouthern Sotho

- barnSwedish

- mtoto, mwanaSwahili

- குழந்தைTamil

- పాపTelugu

- кӯдакTajik

- ศิศุThai

- ቆልዓ, ሕጻንTigrinya

- çagaTurkmen

- anak, bataTagalog

- çocukTurkish

- балаTatar

- بالاUyghur, Uighur

- дити́на, дитя́Ukrainian

- بیٹا, بیٹی, بچہUrdu

- bolaUzbek

- đứa bé, đứa trẻ, con, tửVietnamese

- jicil, daut, jison, hicil, son, cil, cilefVolapük

- xale, guneWolof

- umntwanaXhosa

- קינד, קינדערYiddish

- o̩mo̩, èweYoruba

- 兒童Chinese

- umntwana, inganeZulu

Get even more translations for child »

Translation

Find a translation for the child definition in other languages:

Select another language:

- — Select —

- 简体中文 (Chinese — Simplified)

- 繁體中文 (Chinese — Traditional)

- Español (Spanish)

- Esperanto (Esperanto)

- 日本語 (Japanese)

- Português (Portuguese)

- Deutsch (German)

- العربية (Arabic)

- Français (French)

- Русский (Russian)

- ಕನ್ನಡ (Kannada)

- 한국어 (Korean)

- עברית (Hebrew)

- Gaeilge (Irish)

- Українська (Ukrainian)

- اردو (Urdu)

- Magyar (Hungarian)

- मानक हिन्दी (Hindi)

- Indonesia (Indonesian)

- Italiano (Italian)

- தமிழ் (Tamil)

- Türkçe (Turkish)

- తెలుగు (Telugu)

- ภาษาไทย (Thai)

- Tiếng Việt (Vietnamese)

- Čeština (Czech)

- Polski (Polish)

- Bahasa Indonesia (Indonesian)

- Românește (Romanian)

- Nederlands (Dutch)

- Ελληνικά (Greek)

- Latinum (Latin)

- Svenska (Swedish)

- Dansk (Danish)

- Suomi (Finnish)

- فارسی (Persian)

- ייִדיש (Yiddish)

- հայերեն (Armenian)

- Norsk (Norwegian)

- English (English)

Word of the Day

Would you like us to send you a FREE new word definition delivered to your inbox daily?

Citation

Use the citation below to add this definition to your bibliography:

Are we missing a good definition for child? Don’t keep it to yourself…

-

#1

Hello everyone, I have seen a sentence:

This computer is made in Japan

Compared to this sentence,

which sentence is correct?

This book is written by Shakespeare. or This book was written by Shakespeare?

Thanks so much for your kind help!

-

#2

This book was written by Shakespeare?

This version sounds more natural to me as an isolated sentence. After all, Shakespeare has been dead for centuries.

Sometimes people use present-tense verbs in literature about books that were written in the past. If you were writing an article about Shakespeare’s plays, I wouldn’t be surprised to see that you used verbs in the present tense to give your article a lively quality. However, I don’t think this consideration is important if you merely want to tell us that Shakespeare wrote a book.

-

#3

This (brand of) computer is made in Japan. The company is making some right now.

This (particular) computer was made in Japan. It is two years old.

-

#4

Both sentences in #1 are correct.

This book was written by Shakespeare.This describes an event that happened long ago (him writing this book).

This book is written by Shakespeare.This describes the book. Specifically, it tells us the author.

You can often provide the same meaning, while saying different things.

-

#5

Both sentences in #1 are correct.

This book was written by Shakespeare.

This describes an event that happened long ago (him writing this book).

This book is written by Shakespeare.

This describes the book. Specifically, it tells us the author.

You can often provide the same meaning, while saying different things.

This (brand of) computer is made in Japan. The company is making some right now.

This (particular) computer was made in Japan. It is two years old.

Thanks so much for your kind help!

But can I just say «this» instead of pointing out » brand of » to say

This computer is made in Japan.

Does it make sense?

-

#6

Both sentences in #1 are correct.

This book was written by Shakespeare.

This describes an event that happened long ago (him writing this book).

This book is written by Shakespeare.

This describes the book. Specifically, it tells us the author.

You can often provide the same meaning, while saying different things.

But if I want to ask the author, we should say «who wrote this book?» instead of «who writes this book» (because my teacher has corrected me)

Am I right?

Thanks so much for your kind help!

-

#7

But if I want to ask the author, we should say «who wrote this book?» instead of «who writes this book» (because my teacher has corrected me)

I agree with your teacher. «Who wrote this book?» is an ordinary question when you are asking about a book that was written long ago.

«Who writes this book?» This seems to ask whether somebody is actively writing the book at the time when you ask the question. That is confusing and wrong if you are asking about a book that was written in the past.

-

#8

I agree with your teacher. «Who wrote this book?» is an ordinary question when you are asking about a book that was written long ago.

«Who writes this book?»

This seems to ask whether somebody is actively writing the book at the time when you ask the question. That is confusing and wrong if you are asking about a book that was written in the past.

Thanks so much for your kind help!

In this way, we should say » This book was written by Shakespeare»

And sometimes, passive voice and linking verb structure should use different tenses:

The glass was filled with water by Jane.(Jane filled the glass with water in the past)

The glass now is filled with water.(It described the status of the glass, not the action am I right?)

Thanks so much!

-

#9

You’re welcome.

In this way, we should say » This book was written by Shakespeare»

Right.

The glass was filled with water by Jane.(Jane filled the glass with water in the past)

Right.

The glass now is filled with water.(It described the status of the glass, not the action am I right?)

You are right again. The focus is on the current status of the glass, not the time when it was filled by somebody. In real life, a speaker might well use «The glass is full of water.» However, you have the right idea about the relationship between the verb’s tense and the speaker’s intention.

Last edited: Aug 25, 2016

-

#10

You’re welcome.

Right.

Right.

You are right again. The focus is on the current status of the glass, not the time when it was filled by somebody.

Thanks so much for your kind help!

I still find some verbs which can be understood as linking verb structure or passive voice (like be crowded with, be covered with), they have the same difference.

I know I can say: This piece of material is made of iron.

But I’m not sure if I can say: This piece of material is made with iron or This piece of material was made with iron.

Thanks a million!

-

#11

If I only wanted to comment about what the piece was made of, I’d use the present: This artifact is made of iron.

If I wanted to comment about when an artifact was made, I’d use «was» to talk about something that was made at some time in the past: This artifact was made of iron about 2,000 years ago by a village smith who lived near the area where the city of Manchester is now.

As a general rule, use the past to describe an action that took place in the past. If you want to talk about the material an object is made of, then you’ll probably choose the present tense. As you mentioned earlier, your interest in this situation is focused on the current composition or status of the object.

-

#12

If I only wanted to comment about what the piece was made of, I’d use the present: This artifact is made of iron.

If I wanted to comment about when an artifact was made, I’d use «was» to talk about something that was made at some time in the past: This artifact was made of iron about 2,000 years ago by a village smith who lived near the area where the city of Manchester is now.

Thanks so much!

But what about “be made with”

We can only use this structure to say that something was made by some kind of material in the past, like someone wrote a book in the past. Am I right?

-

#13

We seem to be wandering off topic, moyeea. However, I’ll give you a quick answer about how I use «made with» and «made of»: This chair is made of wood. = The material of the chair is wood. The chair was fashioned/made from wood.

This chair was made with hand tools = I used hand tools, not machines, when I created/made the chair. Maybe I used a saw and a hammer.

-

#14

We seem to be wandering off topic, moyeea. However, I’ll give you a quick answer about how I use «made with» and «made of»: This chair is made of wood. = The material of the chair is wood. The chair was fashioned/made from wood.

This chair was made with hand tools = I used hand tools, not machines, when I created/made the chair. Maybe I used a saw and a hammer.

Thanks so much!

I understand, I really appreciate for your kind help!

Thanks a million!

-

#15

Hello, everyone. I have a similar question.

As a general rule, use the past to describe an action that took place in the past. If you want to talk about the material an object is made of, then you’ll probably choose the present tense.

Can I apply this rule to the following sentences?

1. This picture

is

taken by Kenny.

→ If I want to emphasize the fact that Kenny took the picture, not the action itself.

2. This book

is

written by Kenny.

→ If I want to emphasize the fact that Kenny wrote the book, not the action itself.

3. This painting

is

drawn by Kenny.

→ If I want to emphasize the fact that Kenny drew the painting, not the action itself.

4. This (kind of) cake

is

made by Kenny.

→ If I want to emphasize the fact that Kenny made/created/invented this cake, not the action itself.

Thank you very much.

-

#16

1. This picture

is

taken by Kenny.

→ If I want to emphasize the fact that Kenny took the picture, not the action itself.2. This book

is

written by Kenny.

→ If I want to emphasize the fact that Kenny wrote the book, not the action itself.3. This painting

is

drawn by Kenny.

→ If I want to emphasize the fact that Kenny drew the painting, not the action itself.

You have a lot of passive sentences here, Kenny. If I wanted to refer to these things, I would use active sentences and the past simple: (1) Kenny took this picture. (2) Kenny wrote this book. (3) Kenny painted this painting. All of these sentences emphasize the fact that you were the one who took the picture, wrote the book, and painted the painting. By using active sentences, I give you a natural role as the active agent in all of these actions. I really don’t see any good reason to use the picture, the book, or the painting as the subjects of these sentences.

4. This (kind of) cake

is

made by Kenny.

→ If I want to emphasize the fact that Kenny made/created/invented this cake, not the action itself.

If you regularly make this kind of cake, I would express the idea this way: Kenny makes this kind of cake.

-

#17

You have a lot of passive sentences here, Kenny. If I wanted to refer to these things, I would use active sentences and the past simple: (1) Kenny took this picture. (2) Kenny wrote this book. (3) Kenny painted this painting. All of these sentences emphasize the fact that you were the one who took the picture, wrote the book, and painted the painting. By using active sentences, I give you a natural role as the active agent in all of these actions. I really don’t see any good reason to use the picture, the book, or the painting as the subjects of these sentences.

If you regularly make this kind of cake, I would express the idea this way: Kenny makes this kind of cake.

Thank you for your explanation.

Because of the exercise in the textbook, students were asked to practice writing the passive sentences. Some wrote them in past tense, which I think is correct and logical, but some wrote them in present tense, as the example sentences given. I wonder if present tense is also acceptable with different meanings.

-

#18

I wonder if present tense is also acceptable with different connotations.

You’re welcome. The present tense is sometimes used in passive sentences about how something is made or done. People sometimes use it in references to where something is regularly made/manufactured: These cars are made in Italy. People often use it in references to the materials from which something is made: This chair is made of wood.

More often than not, however, I use the past simple in references to something that was made or done in the past: This guitar was made in Japan. This sculpture was carved by Bernini.

Last edited: Aug 11, 2021

-

#19

You’re welcome. The present tense is sometimes used in passive sentences about how something is made or done. People sometimes use it in references to where something is regularly made/manufactured: These cars are made in Italy. People often use it in references to the materials from which something is made: This chair is made of wood.

More often than not, however, I use the past simple in references to something that was made or done in the past: This guitar was made in Japan. This sculpture was carved by Bernini.

I see. Thank you for your help.

-

#20

You’re welcome. The present tense is sometimes used in passive sentences about how something is made or done. People sometimes use it in references to where something is regularly made/manufactured: These cars are made in Italy. People often use it in references to the materials from which something is made: This chair is made of wood.

More often than not, however, I use the past simple in references to something that was made or done in the past: This guitar was made in Japan. This sculpture was carved by Bernini.

Hi owlman5,

What did you mean by «in references [plural] to»? What is the difference in meaning betweent «in reference to» and «in references to»?

-

#21

Hi owlman5,

What did you mean by «in references [plural] to»? What is the difference in meaning betweent «in reference to» and «in references to»?

There isn’t any important difference in meaning. I used the plural because I was thinking about more than one reference. I often refer to things that were made or done in the past.

-

#22

People often use it in references to the materials from which something is made: This chair is made of wood.

So, both of the following are possible:

a. This chair is made of wood.

b. This chair was made of wood.

(a) means that the chair is composed of wood. [what]

(b) means that the chair was made in the past. [when]

Is that right?

-

#23

So, both of the following are possible:

a. This chair is made of wood.

b. This chair was made of wood.(a) means that the chair is composed of wood. [what]

(b) means that the chair was made in the past. [when]Is that right?

I view both sentences as statements about what the chair is/was made of rather than statements about when the chair was made.

If you wanted to say something about when the chair is/was made, it would be a good idea to mention a date or a time in the sentence: The chair was made last week. I am assembling a chair now, but I should be done before noon.

-

#24

I view both sentences as statements about what the chair is/was made of rather than statements about when the chair was made.

1. Let’s say, a chair is in front of us. We would say «the chair is made of wood» rather than «the chair was made of wood» because «be made of» is like «be composed of». The chair is now still composed of wood.

2. However, we would say «the chair was made from wood» rather than «the chair is made from wood» because «be made from» refers to when it was made.

3. For «the chair was made of wood», it would be a good idea to mention a date or a time in the sentence: «the chair was made of wood

ten years ago

.»

Are these right?

-

#25

1. Let’s say, a chair is in front of us. We would say «the chair is made of wood» rather than «the chair was made of wood» because «be made of» is like «be composed of». The chair is now still composed of wood.

I would probably use is rather than was in this sentence.

2. However, we would say «the chair was made from wood» rather than «the chair is made from wood» because «be made from» refers to when it was made.

Would we? Does it? I have some doubt about these assumptions.

If I wanted to refer to the material from which a chair was made in the past, I would probably phrase the sentence this way: The chair was made of wood. If I used the sentence, I might very well be referring to a chair which no longer exists: As I recall, the chair was made of wood. I haven’t seen it for years, however, so I might be wrong.

3. For «the chair was made of wood», it would be a good idea to mention a date or a time in the sentence: «the chair was made of wood

ten years ago

.»

Ten years ago certainly seems like a good thing to include in a comment about when a chair was made: Somebody made this chair ten years ago/The chair was made ten years ago.

-

#26

If I wanted to refer to the material from which a chair was made in the past, I would probably phrase the sentence this way: The chair was made of wood. If I used the sentence, I might very well be referring to a chair which no longer exists: As I recall, the chair was made of wood. I haven’t seen it for years, however, so I might be wrong.

Thank you, owlman5.

But in post #13 you said «chair is made of wood. = The material of the chair is wood. The chair was fashioned/made from wood.»

If you don’t mind, could you please tell me about «is/was made from» and «is/was made with»?

a. This chair is made from wood.

b. This chair was made from wood.

c. This chair is made with wood.

d. This chair was made with wood.

How can I choose from these tenses? I mean, in what context would they be used?

Last edited: Jan 31, 2023

-

#27

You’re welcome. I don’t think that the preposition has anything to do with the tense that you use in those sentences. I prefer of.

If the chair is sitting in front of you and you are mostly commenting on what material it is made of, is makes sense to me: The chair is made of wood. I don’t care about when it was made.

If you are trying to emphasize the fact that the chair was made in the past, then was is the sensible choice: The chair was made of wood.