Исполнитель: Asliani Название: A Word About RaceБитрейт: 320 kbpsДлительность: 00:50Размер : 1.92 МБДата добавления: 2021-12-29 11:26:53

Сейчас Вы можете скачать песню Asliani — A Word About Race в mp3 бесплатно, прослушать полностью в нашем удобном плеере на телефоне и на других устройствах, и найти другие песни в нашей базе.

Слушать онлайнСкачать mp3

Other forms: races; racing; raced

Race means to speed or move quickly. A race is a contest to see who is moving the quickest. Race can also mean genetic grouping––if you are reading this, chances are you’re a member of the «human race.»

After watching an exciting horse race, your heart may be racing, meaning your pulse is moving fast. You may find yourself racing through your day if you have too much to do, or you might race a friend home from school to see which is fastest, walking or taking the bus. On a form that asks you your race, you will often be prompted with racial categories, such as Caucasian, African-American, or Native American.

Definitions of race

-

“the

race is to the swift”see moresee less-

types:

- show 37 types…

- hide 37 types…

-

auto race, automobile race, car race

a race between (usually high-performance) automobiles

-

bicycle race

a race between people riding bicycles

-

boat race

a race between people rowing or driving boats

-

burnup

a high-speed motorcycle race on a public road

-

chariot race

a race between ancient chariots

-

dog racing

a race between dogs; usually an occasion for betting on the outcome

-

foot race, footrace, run

a race run on foot

-

freestyle

a race (as in swimming) in which each contestant has a free choice of the style to use

-

cross country

a long race run over open country

-

heat

a preliminary race in which the winner advances to a more important race

-

horse race

a contest of speed between horses; usually held for the purpose of betting

-

potato race

a novelty race in which competitors move potatoes from one place to another one at a time

-

sack race

a novelty race in which competitors jump ahead with their feet confined in a sack

-

scratch race

a race in which all contestants start from scratch (on equal terms)

-

ski race, skiing race

a race between people wearing skis

-

relay, relay race

a race between teams; each member runs or swims part of the distance

-

repechage

a race (especially in rowing) in which runners-up in the eliminating heats compete for a place in the final race

-

Grand Prix

one of several international races

-

rally

an automobile race run over public roads

-

Tour de France

a French bicycle race for professional cyclists that lasts three weeks and covers about 3,000 miles

-

sailing-race, yacht race

a race between crews of people in yachts

-

fun run, funrun

a footrace run for fun (often including runners who are sponsored for a charity)

-

marathon

a foot race of 26 miles and 385 yards

-

Iditarod, Iditarod Trail Dog Sled Race

an important dogsled race run annually on the Iditarod Trail

-

claiming race

a horse race in which each owner declares before the race at what price his horse will be offered for sale after the race

-

selling race

a horse race in which the winning horse must be put up for auction

-

harness race, harness racing

a horse race between people riding in sulkies behind horses that are trotting or pacing

-

stake race

a horse race in which part of the prize is put up by the owners of the horses in the race

-

steeplechase

a horse race over an obstructed course

-

obstacle race

a race in which competitors must negotiate obstacles

-

steeplechase

a footrace of usually 3000 meters over a closed track with hurdles and a water jump

-

thoroughbred race

a race between thoroughbred horses

-

downhill

a ski race down a trail

-

slalom

a downhill race over a winding course defined by upright poles

-

torch race

(ancient Greece) in which a torch is passed from one runner to the next

-

track event

a footrace performed on a track (indoor or outdoor)

-

derby

an annual horse race, especially one limited to three-year-old horses

-

type of:

-

competition, contest

an occasion on which a winner is selected from among two or more contestants

-

“the

race for the presidency” -

“let’s

race and see who gets there first”-

synonyms:

run

-

“The cars

raced down the street”-

synonyms:

belt along, bucket along, cannonball along, hasten, hie, hotfoot, pelt along, rush, rush along, speed, step on it

see moresee less-

Antonyms:

-

dawdle, linger

take one’s time; proceed slowly

-

types:

- show 5 types…

- hide 5 types…

-

barge, push forward, thrust ahead

push one’s way

-

buck, charge, shoot, shoot down, tear

move quickly and violently

-

dart, dash, flash, scoot, scud, shoot

run or move very quickly or hastily

-

plunge

dash violently or with great speed or impetuosity

-

rip

move precipitously or violently

-

type of:

-

go, locomote, move, travel

change location; move, travel, or proceed, also metaphorically

-

dawdle, linger

-

verb

to work as fast as possible towards a goal, sometimes in competition with others

“We are

racing to find a cure for AIDS” -

verb

cause to move fast or to rush or race

“The psychologist

raced the rats through a long maze”-

synonyms:

rush

-

noun

people who are believed to belong to the same genetic stock

“some biologists doubt that there are important genetic differences between

races of human beings”see moresee less-

types:

- show 8 types…

- hide 8 types…

-

color, colour, people of color, people of colour

a race with skin pigmentation different from the white race (especially Blacks)

-

Herrenvolk, master race

a race that considers itself superior to all others and fitted to rule the others

-

Black race, Negro race, Negroid race

a dark-skinned race

-

Caucasian race, Caucasoid race, White people, White race

a light-skinned race

-

Mongolian race, Mongoloid race, Yellow race

an Asian race

-

Amerindian race, Indian race

usually included in the Mongoloid race

-

Indian race

sometimes included in the Caucasian race; native to the subcontinent of India

-

Slavic people, Slavic race

a race of people speaking a Slavonic language

-

type of:

-

group, grouping

any number of entities (members) considered as a unit

-

noun

(biology) a taxonomic group that is a division of a species; usually arises as a consequence of geographical isolation within a species

-

noun

a canal for a current of water

-

noun

the flow of air that is driven backwards by an aircraft propeller

DISCLAIMER: These example sentences appear in various news sources and books to reflect the usage of the word ‘race’.

Views expressed in the examples do not represent the opinion of Vocabulary.com or its editors.

Send us feedback

EDITOR’S CHOICE

Look up race for the last time

Close your vocabulary gaps with personalized learning that focuses on teaching the

words you need to know.

Sign up now (it’s free!)

Whether you’re a teacher or a learner, Vocabulary.com can put you or your class on the path to systematic vocabulary improvement.

Get started

Below is a massive list of racing words — that is, words related to racing. The top 4 are: driving, speed, raceway and speedway. You can get the definition(s) of a word in the list below by tapping the question-mark icon next to it. The words at the top of the list are the ones most associated with racing, and as you go down the relatedness becomes more slight. By default, the words are sorted by relevance/relatedness, but you can also get the most common racing terms by using the menu below, and there’s also the option to sort the words alphabetically so you can get racing words starting with a particular letter. You can also filter the word list so it only shows words that are also related to another word of your choosing. So for example, you could enter «driving» and click «filter», and it’d give you words that are related to racing and driving.

You can highlight the terms by the frequency with which they occur in the written English language using the menu below. The frequency data is extracted from the English Wikipedia corpus, and updated regularly. If you just care about the words’ direct semantic similarity to racing, then there’s probably no need for this.

There are already a bunch of websites on the net that help you find synonyms for various words, but only a handful that help you find related, or even loosely associated words. So although you might see some synonyms of racing in the list below, many of the words below will have other relationships with racing — you could see a word with the exact opposite meaning in the word list, for example. So it’s the sort of list that would be useful for helping you build a racing vocabulary list, or just a general racing word list for whatever purpose, but it’s not necessarily going to be useful if you’re looking for words that mean the same thing as racing (though it still might be handy for that).

If you’re looking for names related to racing (e.g. business names, or pet names), this page might help you come up with ideas. The results below obviously aren’t all going to be applicable for the actual name of your pet/blog/startup/etc., but hopefully they get your mind working and help you see the links between various concepts. If your pet/blog/etc. has something to do with racing, then it’s obviously a good idea to use concepts or words to do with racing.

If you don’t find what you’re looking for in the list below, or if there’s some sort of bug and it’s not displaying racing related words, please send me feedback using this page. Thanks for using the site — I hope it is useful to you! 🐉

That’s about all the racing related words we’ve got! I hope this list of racing terms was useful to you in some way or another. The words down here at the bottom of the list will be in some way associated with racing, but perhaps tenuously (if you’ve currenly got it sorted by relevance, that is). If you have any feedback for the site, please share it here, but please note this is only a hobby project, so I may not be able to make regular updates to the site. Have a nice day! 🐕

This article is about categorization of human populations. For «the human race», see Human.

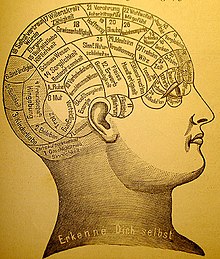

Race is a categorization of humans based on shared physical or social qualities into groups generally viewed as distinct within a given society.[1] The term came into common usage during the 16th century, when it was used to refer to groups of various kinds, including those characterized by close kinship relations.[2] By the 17th century, the term began to refer to physical (phenotypical) traits, and then later to national affiliations. Modern science regards race as a social construct, an identity which is assigned based on rules made by society.[3][4] While partly based on physical similarities within groups, race does not have an inherent physical or biological meaning.[1][5][6] The concept of race is foundational to racism, the belief that humans can be divided based on the superiority of one race over another.

Social conceptions and groupings of races have varied over time, often involving folk taxonomies that define essential types of individuals based on perceived traits.[7] Today, scientists consider such biological essentialism obsolete,[8] and generally discourage racial explanations for collective differentiation in both physical and behavioral traits.[9][10][11][12][13]

Even though there is a broad scientific agreement that essentialist and typological conceptions of race are untenable,[14][15][16][17][18][19] scientists around the world continue to conceptualize race in widely differing ways.[20] While some researchers continue to use the concept of race to make distinctions among fuzzy sets of traits or observable differences in behavior, others in the scientific community suggest that the idea of race is inherently naive[9] or simplistic.[21] Still others argue that, among humans, race has no taxonomic significance because all living humans belong to the same subspecies, Homo sapiens sapiens.[22][23]

Since the second half of the 20th century, race has been associated with discredited theories of scientific racism, and has become increasingly seen as a largely pseudoscientific system of classification. Although still used in general contexts, race has often been replaced by less ambiguous and/or loaded terms: populations, people(s), ethnic groups, or communities, depending on context.[24][25]

Defining race

Modern scholarship views racial categories as socially constructed, that is, race is not intrinsic to human beings but rather an identity created, often by socially dominant groups, to establish meaning in a social context. Different cultures define different racial groups, often focused on the largest groups of social relevance, and these definitions can change over time.

- In South Africa, the Population Registration Act, 1950 recognized only White, Black, and Coloured, with Indians added later.[26]

- The government of Myanmar recognizes eight «major national ethnic races».

- The Brazilian census classifies people into brancos (Whites), pardos (multiracial), pretos (Blacks), amarelos (Asians), and indigenous (see Race and ethnicity in Brazil), though many people use different terms to identify themselves.

- The United States Census Bureau proposed but then withdrew plans to add a new category to classify Middle Eastern and North African peoples in the 2020 U.S. census, over a dispute over whether this classification should be considered a white ethnicity or a separate race.[27]

- Legal definitions of whiteness in the United States used before the civil rights movement were often challenged for specific groups.

- Historical race concepts have included a wide variety of schemes to divide local or worldwide populations into races and sub-races.

The establishment of racial boundaries often involves the subjugation of groups defined as racially inferior, as in the one-drop rule used in the 19th-century United States to exclude those with any amount of African ancestry from the dominant racial grouping, defined as «white».[1] Such racial identities reflect the cultural attitudes of imperial powers dominant during the age of European colonial expansion.[5] This view rejects the notion that race is biologically defined.[28][29][30][31]

According to geneticist David Reich, «while race may be a social construct, differences in genetic ancestry that happen to correlate to many of today’s racial constructs are real.»[32] In response to Reich, a group of 67 scientists from a broad range of disciplines wrote that his concept of race was «flawed» as «the meaning and significance of the groups is produced through social interventions».[33]

Although commonalities in physical traits such as facial features, skin color, and hair texture comprise part of the race concept, this linkage is a social distinction rather than an inherently biological one.[1] Other dimensions of racial groupings include shared history, traditions, and language. For instance, African-American English is a language spoken by many African Americans, especially in areas of the United States where racial segregation exists. Furthermore, people often self-identify as members of a race for political reasons.[1]

When people define and talk about a particular conception of race, they create a social reality through which social categorization is achieved.[34] In this sense, races are said to be social constructs.[35] These constructs develop within various legal, economic, and sociopolitical contexts, and may be the effect, rather than the cause, of major social situations.[clarify][36] While race is understood to be a social construct by many, most scholars agree that race has real material effects in the lives of people through institutionalized practices of preference and discrimination.[citation needed]

Socioeconomic factors, in combination with early but enduring views of race, have led to considerable suffering within disadvantaged racial groups.[37] Racial discrimination often coincides with racist mindsets, whereby the individuals and ideologies of one group come to perceive the members of an outgroup as both racially defined and morally inferior.[38] As a result, racial groups possessing relatively little power often find themselves excluded or oppressed, while hegemonic individuals and institutions are charged with holding racist attitudes.[39] Racism has led to many instances of tragedy, including slavery and genocide.[40]

In some countries, law enforcement uses race to profile suspects. This use of racial categories is frequently criticized for perpetuating an outmoded understanding of human biological variation, and promoting stereotypes. Because in some societies racial groupings correspond closely with patterns of social stratification, for social scientists studying social inequality, race can be a significant variable. As sociological factors, racial categories may in part reflect subjective attributions, self-identities, and social institutions.[41][42]

Scholars continue to debate the degrees to which racial categories are biologically warranted and socially constructed.[43] For example, in 2008, John Hartigan, Jr. argued for a view of race that focused primarily on culture, but which does not ignore the potential relevance of biology or genetics.[44] Accordingly, the racial paradigms employed in different disciplines vary in their emphasis on biological reduction as contrasted with societal construction.

In the social sciences, theoretical frameworks such as racial formation theory and critical race theory investigate implications of race as social construction by exploring how the images, ideas and assumptions of race are expressed in everyday life. A large body of scholarship has traced the relationships between the historical, social production of race in legal and criminal language, and their effects on the policing and disproportionate incarceration of certain groups.

Historical origins of racial classification

Groups of humans have always identified themselves as distinct from neighboring groups, but such differences have not always been understood to be natural, immutable and global. These features are the distinguishing features of how the concept of race is used today. In this way the idea of race as we understand it today came about during the historical process of exploration and conquest which brought Europeans into contact with groups from different continents, and of the ideology of classification and typology found in the natural sciences.[45] The term race was often used in a general biological taxonomic sense,[24] starting from the 19th century, to denote genetically differentiated human populations defined by phenotype.[46][47]

The modern concept of race emerged as a product of the colonial enterprises of European powers from the 16th to 18th centuries which identified race in terms of skin color and physical differences. Author Rebecca F. Kennedy argues that the Greeks and Romans would have found such concepts confusing in relation to their own systems of classification.[48] According to Bancel et al., the epistemological moment where the modern concept of race was invented and rationalized lies somewhere between 1730 and 1790.[49]

Colonialism

According to Smedley and Marks the European concept of «race», along with many of the ideas now associated with the term, arose at the time of the scientific revolution, which introduced and privileged the study of natural kinds, and the age of European imperialism and colonization which established political relations between Europeans and peoples with distinct cultural and political traditions.[45][50] As Europeans encountered people from different parts of the world, they speculated about the physical, social, and cultural differences among various human groups. The rise of the Atlantic slave trade, which gradually displaced an earlier trade in slaves from throughout the world, created a further incentive to categorize human groups in order to justify the subordination of African slaves.[51]

Drawing on sources from classical antiquity and upon their own internal interactions – for example, the hostility between the English and Irish powerfully influenced early European thinking about the differences between people[52] – Europeans began to sort themselves and others into groups based on physical appearance, and to attribute to individuals belonging to these groups behaviors and capacities which were claimed to be deeply ingrained. A set of folk beliefs took hold that linked inherited physical differences between groups to inherited intellectual, behavioral, and moral qualities.[53] Similar ideas can be found in other cultures,[54] for example in China, where a concept often translated as «race» was associated with supposed common descent from the Yellow Emperor, and used to stress the unity of ethnic groups in China. Brutal conflicts between ethnic groups have existed throughout history and across the world.[55]

Early taxonomic models

The first post-Graeco-Roman published classification of humans into distinct races seems to be François Bernier’s Nouvelle division de la terre par les différents espèces ou races qui l’habitent («New division of Earth by the different species or races which inhabit it»), published in 1684.[56] In the 18th century the differences among human groups became a focus of scientific investigation. But the scientific classification of phenotypic variation was frequently coupled with racist ideas about innate predispositions of different groups, always attributing the most desirable features to the White, European race and arranging the other races along a continuum of progressively undesirable attributes. The 1735 classification of Carl Linnaeus, inventor of zoological taxonomy, divided the human species Homo sapiens into continental varieties of europaeus, asiaticus, americanus, and afer, each associated with a different humour: sanguine, melancholic, choleric, and phlegmatic, respectively.[57][58] Homo sapiens europaeus was described as active, acute, and adventurous, whereas Homo sapiens afer was said to be crafty, lazy, and careless.[59]

The 1775 treatise «The Natural Varieties of Mankind», by Johann Friedrich Blumenbach proposed five major divisions: the Caucasoid race, the Mongoloid race, the Ethiopian race (later termed Negroid), the American Indian race, and the Malayan race, but he did not propose any hierarchy among the races.[59] Blumenbach also noted the graded transition in appearances from one group to adjacent groups and suggested that «one variety of mankind does so sensibly pass into the other, that you cannot mark out the limits between them».[60]

From the 17th through 19th centuries, the merging of folk beliefs about group differences with scientific explanations of those differences produced what Smedley has called an «ideology of race».[50] According to this ideology, races are primordial, natural, enduring and distinct. It was further argued that some groups may be the result of mixture between formerly distinct populations, but that careful study could distinguish the ancestral races that had combined to produce admixed groups.[55] Subsequent influential classifications by Georges Buffon, Petrus Camper and Christoph Meiners all classified «Negros» as inferior to Europeans.[59] In the United States the racial theories of Thomas Jefferson were influential. He saw Africans as inferior to Whites especially in regards to their intellect, and imbued with unnatural sexual appetites, but described Native Americans as equals to whites.[61]

Polygenism vs monogenism

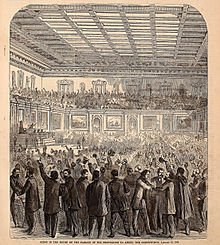

In the last two decades of the 18th century, the theory of polygenism, the belief that different races had evolved separately in each continent and shared no common ancestor,[62] was advocated in England by historian Edward Long and anatomist Charles White, in Germany by ethnographers Christoph Meiners and Georg Forster, and in France by Julien-Joseph Virey. In the US, Samuel George Morton, Josiah Nott and Louis Agassiz promoted this theory in the mid-19th century. Polygenism was popular and most widespread in the 19th century, culminating in the founding of the Anthropological Society of London (1863), which, during the period of the American Civil War, broke away from the Ethnological Society of London and its monogenic stance, their underlined difference lying, relevantly, in the so-called «Negro question»: a substantial racist view by the former,[63] and a more liberal view on race by the latter.[64]

Modern scholarship

Models of human evolution

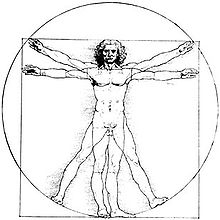

Today, all humans are classified as belonging to the species Homo sapiens. However, this is not the first species of homininae: the first species of genus Homo, Homo habilis, evolved in East Africa at least 2 million years ago, and members of this species populated different parts of Africa in a relatively short time. Homo erectus evolved more than 1.8 million years ago, and by 1.5 million years ago had spread throughout Europe and Asia. Virtually all physical anthropologists agree that Archaic Homo sapiens (A group including the possible species H. heidelbergensis, H. rhodesiensis and H. neanderthalensis) evolved out of African Homo erectus (sensu lato) or Homo ergaster.[65][66] Anthropologists support the idea that anatomically modern humans (Homo sapiens) evolved in North or East Africa from an archaic human species such as H. heidelbergensis and then migrated out of Africa, mixing with and replacing H. heidelbergensis and H. neanderthalensis populations throughout Europe and Asia, and H. rhodesiensis populations in Sub-Saharan Africa (a combination of the Out of Africa and Multiregional models).[67][verification needed]

Biological classification

In the early 20th century, many anthropologists taught that race was an entirely biological phenomenon and that this was core to a person’s behavior and identity, a position commonly called racial essentialism.[68] This, coupled with a belief that linguistic, cultural, and social groups fundamentally existed along racial lines, formed the basis of what is now called scientific racism.[69] After the Nazi eugenics program, along with the rise of anti-colonial movements, racial essentialism lost widespread popularity.[70] New studies of culture and the fledgling field of population genetics undermined the scientific standing of racial essentialism, leading race anthropologists to revise their conclusions about the sources of phenotypic variation.[68] A significant number of modern anthropologists and biologists in the West came to view race as an invalid genetic or biological designation.[71]

The first to challenge the concept of race on empirical grounds were the anthropologists Franz Boas, who provided evidence of phenotypic plasticity due to environmental factors,[72] and Ashley Montagu, who relied on evidence from genetics.[73] E. O. Wilson then challenged the concept from the perspective of general animal systematics, and further rejected the claim that «races» were equivalent to «subspecies».[74]

Human genetic variation is predominantly within races, continuous, and complex in structure, which is inconsistent with the concept of genetic human races.[75] According to the biological anthropologist Jonathan Marks,[45]

By the 1970s, it had become clear that (1) most human differences were cultural; (2) what was not cultural was principally polymorphic – that is to say, found in diverse groups of people at different frequencies; (3) what was not cultural or polymorphic was principally clinal – that is to say, gradually variable over geography; and (4) what was left – the component of human diversity that was not cultural, polymorphic, or clinal – was very small.

A consensus consequently developed among anthropologists and geneticists that race as the previous generation had known it – as largely discrete, geographically distinct, gene pools – did not exist.

Subspecies

The term race in biology is used with caution because it can be ambiguous. Generally, when it is used it is effectively a synonym of subspecies.[76] (For animals, the only taxonomic unit below the species level is usually the subspecies;[77] there are narrower infraspecific ranks in botany, and race does not correspond directly with any of them.) Traditionally, subspecies are seen as geographically isolated and genetically differentiated populations.[78] Studies of human genetic variation show that human populations are not geographically isolated,[79] and their genetic differences are far smaller than those among comparable subspecies.[80]

In 1978, Sewall Wright suggested that human populations that have long inhabited separated parts of the world should, in general, be considered different subspecies by the criterion that most individuals of such populations can be allocated correctly by inspection. Wright argued that, «It does not require a trained anthropologist to classify an array of Englishmen, West Africans, and Chinese with 100% accuracy by features, skin color, and type of hair despite so much variability within each of these groups that every individual can easily be distinguished from every other.»[81] While in practice subspecies are often defined by easily observable physical appearance, there is not necessarily any evolutionary significance to these observed differences, so this form of classification has become less acceptable to evolutionary biologists.[82] Likewise this typological approach to race is generally regarded as discredited by biologists and anthropologists.[83][16]

Ancestrally differentiated populations (clades)

In 2000, philosopher Robin Andreasen proposed that cladistics might be used to categorize human races biologically, and that races can be both biologically real and socially constructed.[84] Andreasen cited tree diagrams of relative genetic distances among populations published by Luigi Cavalli-Sforza as the basis for a phylogenetic tree of human races (p. 661). Biological anthropologist Jonathan Marks (2008) responded by arguing that Andreasen had misinterpreted the genetic literature: «These trees are phenetic (based on similarity), rather than cladistic (based on monophyletic descent, that is from a series of unique ancestors).»[85] Evolutionary biologist Alan Templeton (2013) argued that multiple lines of evidence falsify the idea of a phylogenetic tree structure to human genetic diversity, and confirm the presence of gene flow among populations.[31] Marks, Templeton, and Cavalli-Sforza all conclude that genetics does not provide evidence of human races.[31][86]

Previously, anthropologists Lieberman and Jackson (1995) had also critiqued the use of cladistics to support concepts of race. They argued that «the molecular and biochemical proponents of this model explicitly use racial categories in their initial grouping of samples«. For example, the large and highly diverse macroethnic groups of East Indians, North Africans, and Europeans are presumptively grouped as Caucasians prior to the analysis of their DNA variation. They argued that this a priori grouping limits and skews interpretations, obscures other lineage relationships, deemphasizes the impact of more immediate clinal environmental factors on genomic diversity, and can cloud our understanding of the true patterns of affinity.[87]

In 2015, Keith Hunley, Graciela Cabana, and Jeffrey Long analyzed the Human Genome Diversity Project sample of 1,037 individuals in 52 populations,[88] finding that diversity among non-African populations is the result of a serial founder effect process, with non-African populations as a whole nested among African populations, that «some African populations are equally related to other African populations and to non-African populations,» and that «outside of Africa, regional groupings of populations are nested inside one another, and many of them are not monophyletic.»[88] Earlier research had also suggested that there has always been considerable gene flow between human populations, meaning that human population groups are not monophyletic.[78] Rachel Caspari has argued that, since no groups currently regarded as races are monophyletic, by definition none of these groups can be clades.[89]

Clines

One crucial innovation in reconceptualizing genotypic and phenotypic variation was the anthropologist C. Loring Brace’s observation that such variations, insofar as it is affected by natural selection, slow migration, or genetic drift, are distributed along geographic gradations or clines.[90] For example, with respect to skin color in Europe and Africa, Brace writes:

To this day, skin color grades by imperceptible means from Europe southward around the eastern end of the Mediterranean and up the Nile into Africa. From one end of this range to the other, there is no hint of a skin color boundary, and yet the spectrum runs from the lightest in the world at the northern edge to as dark as it is possible for humans to be at the equator.[91]

In part this is due to isolation by distance. This point called attention to a problem common to phenotype-based descriptions of races (for example, those based on hair texture and skin color): they ignore a host of other similarities and differences (for example, blood type) that do not correlate highly with the markers for race. Thus, anthropologist Frank Livingstone’s conclusion, that since clines cross racial boundaries, «there are no races, only clines».[92]

In a response to Livingstone, Theodore Dobzhansky argued that when talking about race one must be attentive to how the term is being used: «I agree with Dr. Livingstone that if races have to be ‘discrete units’, then there are no races, and if ‘race’ is used as an ‘explanation’ of the human variability, rather than vice versa, then the explanation is invalid.» He further argued that one could use the term race if one distinguished between «race differences» and «the race concept». The former refers to any distinction in gene frequencies between populations; the latter is «a matter of judgment». He further observed that even when there is clinal variation, «Race differences are objectively ascertainable biological phenomena … but it does not follow that racially distinct populations must be given racial (or subspecific) labels.»[92] In short, Livingstone and Dobzhansky agree that there are genetic differences among human beings; they also agree that the use of the race concept to classify people, and how the race concept is used, is a matter of social convention. They differ on whether the race concept remains a meaningful and useful social convention.

Skin color (above) and blood type B (below) are nonconcordant traits since their geographical distribution is not similar.

In 1964, the biologists Paul Ehrlich and Holm pointed out cases where two or more clines are distributed discordantly – for example, melanin is distributed in a decreasing pattern from the equator north and south; frequencies for the haplotype for beta-S hemoglobin, on the other hand, radiate out of specific geographical points in Africa.[93] As the anthropologists Leonard Lieberman and Fatimah Linda Jackson observed, «Discordant patterns of heterogeneity falsify any description of a population as if it were genotypically or even phenotypically homogeneous».[87]

Patterns such as those seen in human physical and genetic variation as described above, have led to the consequence that the number and geographic location of any described races is highly dependent on the importance attributed to, and quantity of, the traits considered. A skin-lightening mutation, estimated to have occurred 20,000 to 50,000 years ago, partially accounts for the appearance of light skin in people who migrated out of Africa northward into what is now Europe. East Asians owe their relatively light skin to different mutations.[94] On the other hand, the greater the number of traits (or alleles) considered, the more subdivisions of humanity are detected, since traits and gene frequencies do not always correspond to the same geographical location. Or as Ossorio & Duster (2005) put it:

Anthropologists long ago discovered that humans’ physical traits vary gradually, with groups that are close geographic neighbors being more similar than groups that are geographically separated. This pattern of variation, known as clinal variation, is also observed for many alleles that vary from one human group to another. Another observation is that traits or alleles that vary from one group to another do not vary at the same rate. This pattern is referred to as nonconcordant variation. Because the variation of physical traits is clinal and nonconcordant, anthropologists of the late 19th and early 20th centuries discovered that the more traits and the more human groups they measured, the fewer discrete differences they observed among races and the more categories they had to create to classify human beings. The number of races observed expanded to the 1930s and 1950s, and eventually anthropologists concluded that there were no discrete races.[95] Twentieth and 21st century biomedical researchers have discovered this same feature when evaluating human variation at the level of alleles and allele frequencies. Nature has not created four or five distinct, nonoverlapping genetic groups of people.

Genetically differentiated populations

Another way to look at differences between populations is to measure genetic differences rather than physical differences between groups. The mid-20th-century anthropologist William C. Boyd defined race as: «A population which differs significantly from other populations in regard to the frequency of one or more of the genes it possesses. It is an arbitrary matter which, and how many, gene loci we choose to consider as a significant ‘constellation'».[96] Leonard Lieberman and Rodney Kirk have pointed out that «the paramount weakness of this statement is that if one gene can distinguish races then the number of races is as numerous as the number of human couples reproducing.»[97] Moreover, the anthropologist Stephen Molnar has suggested that the discordance of clines inevitably results in a multiplication of races that renders the concept itself useless.[98] The Human Genome Project states «People who have lived in the same geographic region for many generations may have some alleles in common, but no allele will be found in all members of one population and in no members of any other.»[99] Massimo Pigliucci and Jonathan Kaplan argue that human races do exist, and that they correspond to the genetic classification of ecotypes, but that real human races do not correspond very much, if at all, to folk racial categories.[100] In contrast, Walsh & Yun reviewed the literature in 2011 and reported that «Genetic studies using very few chromosomal loci find that genetic polymorphisms divide human populations into clusters with almost 100 percent accuracy and that they correspond to the traditional anthropological categories.»[101]

Some biologists argue that racial categories correlate with biological traits (e.g. phenotype), and that certain genetic markers have varying frequencies among human populations, some of which correspond more or less to traditional racial groupings.[102]

Distribution of genetic variation

The distribution of genetic variants within and among human populations are impossible to describe succinctly because of the difficulty of defining a population, the clinal nature of variation, and heterogeneity across the genome (Long and Kittles 2003). In general, however, an average of 85% of statistical genetic variation exists within local populations, ≈7% is between local populations within the same continent, and ≈8% of variation occurs between large groups living on different continents.[103][104] The recent African origin theory for humans would predict that in Africa there exists a great deal more diversity than elsewhere and that diversity should decrease the further from Africa a population is sampled. Hence, the 85% average figure is misleading: Long and Kittles find that rather than 85% of human genetic diversity existing in all human populations, about 100% of human diversity exists in a single African population, whereas only about 60% of human genetic diversity exists in the least diverse population they analyzed (the Surui, a population derived from New Guinea).[105] Statistical analysis that takes this difference into account confirms previous findings that, «Western-based racial classifications have no taxonomic significance.»[88]

Cluster analysis

A 2002 study of random biallelic genetic loci found little to no evidence that humans were divided into distinct biological groups.[106]

In his 2003 paper, «Human Genetic Diversity: Lewontin’s Fallacy», A. W. F. Edwards argued that rather than using a locus-by-locus analysis of variation to derive taxonomy, it is possible to construct a human classification system based on characteristic genetic patterns, or clusters inferred from multilocus genetic data.[107][108] Geographically based human studies since have shown that such genetic clusters can be derived from analyzing of a large number of loci which can assort individuals sampled into groups analogous to traditional continental racial groups.[109][110] Joanna Mountain and Neil Risch cautioned that while genetic clusters may one day be shown to correspond to phenotypic variations between groups, such assumptions were premature as the relationship between genes and complex traits remains poorly understood.[111] However, Risch denied such limitations render the analysis useless: «Perhaps just using someone’s actual birth year is not a very good way of measuring age. Does that mean we should throw it out? … Any category you come up with is going to be imperfect, but that doesn’t preclude you from using it or the fact that it has utility.»[112]

Early human genetic cluster analysis studies were conducted with samples taken from ancestral population groups living at extreme geographic distances from each other. It was thought that such large geographic distances would maximize the genetic variation between the groups sampled in the analysis, and thus maximize the probability of finding cluster patterns unique to each group. In light of the historically recent acceleration of human migration (and correspondingly, human gene flow) on a global scale, further studies were conducted to judge the degree to which genetic cluster analysis can pattern ancestrally identified groups as well as geographically separated groups. One such study looked at a large multiethnic population in the United States, and «detected only modest genetic differentiation between different current geographic locales within each race/ethnicity group. Thus, ancient geographic ancestry, which is highly correlated with self-identified race/ethnicity – as opposed to current residence – is the major determinant of genetic structure in the U.S. population.»[110]

Witherspoon et al. (2007) have argued that even when individuals can be reliably assigned to specific population groups, it may still be possible for two randomly chosen individuals from different populations/clusters to be more similar to each other than to a randomly chosen member of their own cluster. They found that many thousands of genetic markers had to be used in order for the answer to the question «How often is a pair of individuals from one population genetically more dissimilar than two individuals chosen from two different populations?» to be «never». This assumed three population groups separated by large geographic ranges (European, African and East Asian). The entire world population is much more complex and studying an increasing number of groups would require an increasing number of markers for the same answer. The authors conclude that «caution should be used when using geographic or genetic ancestry to make inferences about individual phenotypes.»[113] Witherspoon, et al. concluded that, «The fact that, given enough genetic data, individuals can be correctly assigned to their populations of origin is compatible with the observation that most human genetic variation is found within populations, not between them. It is also compatible with our finding that, even when the most distinct populations are considered and hundreds of loci are used, individuals are frequently more similar to members of other populations than to members of their own population.»[113]

Anthropologists such as C. Loring Brace,[114] the philosophers Jonathan Kaplan and Rasmus Winther,[115][116][117][118] and the geneticist Joseph Graves,[21] have argued that while there it is certainly possible to find biological and genetic variation that corresponds roughly to the groupings normally defined as «continental races», this is true for almost all geographically distinct populations. The cluster structure of the genetic data is therefore dependent on the initial hypotheses of the researcher and the populations sampled. When one samples continental groups, the clusters become continental; if one had chosen other sampling patterns, the clustering would be different. Weiss and Fullerton have noted that if one sampled only Icelanders, Mayans and Maoris, three distinct clusters would form and all other populations could be described as being clinally composed of admixtures of Maori, Icelandic and Mayan genetic materials.[119] Kaplan and Winther therefore argue that, seen in this way, both Lewontin and Edwards are right in their arguments. They conclude that while racial groups are characterized by different allele frequencies, this does not mean that racial classification is a natural taxonomy of the human species, because multiple other genetic patterns can be found in human populations that crosscut racial distinctions. Moreover, the genomic data underdetermines whether one wishes to see subdivisions (i.e., splitters) or a continuum (i.e., lumpers). Under Kaplan and Winther’s view, racial groupings are objective social constructions (see Mills 1998[120]) that have conventional biological reality only insofar as the categories are chosen and constructed for pragmatic scientific reasons. In earlier work, Winther had identified «diversity partitioning» and «clustering analysis» as two separate methodologies, with distinct questions, assumptions, and protocols. Each is also associated with opposing ontological consequences vis-a-vis the metaphysics of race.[121] Philosopher Lisa Gannett has argued that biogeographical ancestry, a concept devised by Mark Shriver and Tony Frudakis, is not an objective measure of the biological aspects of race as Shriver and Frudakis claim it is. She argues that it is actually just a «local category shaped by the U.S. context of its production, especially the forensic aim of being able to predict the race or ethnicity of an unknown suspect based on DNA found at the crime scene.»[122]

Clines and clusters in genetic variation

Recent studies of human genetic clustering have included a debate over how genetic variation is organized, with clusters and clines as the main possible orderings.Serre & Pääbo (2004) argued for smooth, clinal genetic variation in ancestral populations even in regions previously considered racially homogeneous, with the apparent gaps turning out to be artifacts of sampling techniques.Rosenberg et al. (2005) disputed this and offered an analysis of the Human Genetic Diversity Panel showing that there were small discontinuities in the smooth genetic variation for ancestral populations at the location of geographic barriers such as the Sahara, the Oceans, and the Himalayas. Nonetheless,Rosenberg et al. (2005) stated that their findings «should not be taken as evidence of our support of any particular concept of biological race… Genetic differences among human populations derive mainly from gradations in allele frequencies rather than from distinctive ‘diagnostic’ genotypes.» Using a sample of 40 populations distributed roughly evenly across the Earth’s land surface,Xing & et al. (2010, p. 208) found that «genetic diversity is distributed in a more clinal pattern when more geographically intermediate populations are sampled.»

Guido Barbujani has written that human genetic variation is generally distributed continuously in gradients across much of Earth, and that there is no evidence that genetic boundaries between human populations exist as would be necessary for human races to exist.[123]

Over time, human genetic variation has formed a nested structure that is inconsistent with the concept of races that have evolved independently of one another.[124]

As anthropologists and other evolutionary scientists have shifted away from the language of race to the term population to talk about genetic differences, historians, cultural anthropologists and other social scientists re-conceptualized the term «race» as a cultural category or identity, i.e., a way among many possible ways in which a society chooses to divide its members into categories.

Many social scientists have replaced the word race with the word «ethnicity» to refer to self-identifying groups based on beliefs concerning shared culture, ancestry and history. Alongside empirical and conceptual problems with «race», following the Second World War, evolutionary and social scientists were acutely aware of how beliefs about race had been used to justify discrimination, apartheid, slavery, and genocide. This questioning gained momentum in the 1960s during the civil rights movement in the United States and the emergence of numerous anti-colonial movements worldwide. They thus came to believe that race itself is a social construct, a concept that was believed to correspond to an objective reality but which was believed in because of its social functions.[125]

Craig Venter and Francis Collins of the National Institute of Health jointly made the announcement of the mapping of the human genome in 2000. Upon examining the data from the genome mapping, Venter realized that although the genetic variation within the human species is on the order of 1–3% (instead of the previously assumed 1%), the types of variations do not support notion of genetically defined races. Venter said, «Race is a social concept. It’s not a scientific one. There are no bright lines (that would stand out), if we could compare all the sequenced genomes of everyone on the planet.» «When we try to apply science to try to sort out these social differences, it all falls apart.»[126]

Anthropologist Stephan Palmié has argued that race «is not a thing but a social relation»;[127] or, in the words of Katya Gibel Mevorach, «a metonym», «a human invention whose criteria for differentiation are neither universal nor fixed but have always been used to manage difference.»[128] As such, the use of the term «race» itself must be analyzed. Moreover, they argue that biology will not explain why or how people use the idea of race; only history and social relationships will.

Imani Perry has argued that race «is produced by social arrangements and political decision making»,[129] and that «race is something that happens, rather than something that is. It is dynamic, but it holds no objective truth.»[130] Similarly, Racial Culture: A Critique (2005), Richard T. Ford argued that while «there is no necessary correspondence between the ascribed identity of race and one’s culture or personal sense of self» and «group difference is not intrinsic to members of social groups but rather contingent o[n] the social practices of group identification», the social practices of identity politics may coerce individuals into the «compulsory» enactment of «prewritten racial scripts».[131]

Brazil

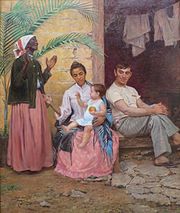

Portrait «Redenção de Cam» (1895), showing a Brazilian family becoming «whiter» each generation

Compared to 19th-century United States, 20th-century Brazil was characterized by a perceived relative absence of sharply defined racial groups. According to anthropologist Marvin Harris, this pattern reflects a different history and different social relations.

Race in Brazil was «biologized», but in a way that recognized the difference between ancestry (which determines genotype) and phenotypic differences. There, racial identity was not governed by rigid descent rule, such as the one-drop rule, as it was in the United States. A Brazilian child was never automatically identified with the racial type of one or both parents, nor were there only a very limited number of categories to choose from,[132] to the extent that full siblings can pertain to different racial groups.[133]

| Self-reported ancestry of people from Rio de Janeiro, by race or skin color (2000 survey)[134] |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Ancestry | brancos | pardos | negros |

| European only | 48% | 6% | – |

| African only | – | 12% | 25% |

| Amerindian only | – | 2% | – |

| African and European | 23% | 34% | 31% |

| Amerindian and European | 14% | 6% | – |

| African and Amerindian | – | 4% | 9% |

| African, Amerindian and European | 15% | 36% | 35% |

| Total | 100% | 100% | 100% |

| Any African | 38% | 86% | 100% |

Over a dozen racial categories would be recognized in conformity with all the possible combinations of hair color, hair texture, eye color, and skin color. These types grade into each other like the colors of the spectrum, and not one category stands significantly isolated from the rest. That is, race referred preferentially to appearance, not heredity, and appearance is a poor indication of ancestry, because only a few genes are responsible for someone’s skin color and traits: a person who is considered white may have more African ancestry than a person who is considered black, and the reverse can be also true about European ancestry.[135] The complexity of racial classifications in Brazil reflects the extent of genetic mixing in Brazilian society, a society that remains highly, but not strictly, stratified along color lines. These socioeconomic factors are also significant to the limits of racial lines, because a minority of pardos, or brown people, are likely to start declaring themselves white or black if socially upward,[136] and being seen as relatively «whiter» as their perceived social status increases (much as in other regions of Latin America).[137]

Fluidity of racial categories aside, the «biologification» of race in Brazil referred above would match contemporary concepts of race in the United States quite closely, though, if Brazilians are supposed to choose their race as one among, Asian and Indigenous apart, three IBGE’s census categories. While assimilated Amerindians and people with very high quantities of Amerindian ancestry are usually grouped as caboclos, a subgroup of pardos which roughly translates as both mestizo and hillbilly, for those of lower quantity of Amerindian descent a higher European genetic contribution is expected to be grouped as a pardo. In several genetic tests, people with less than 60-65% of European descent and 5–10% of Amerindian descent usually cluster with Afro-Brazilians (as reported by the individuals), or 6.9% of the population, and those with about 45% or more of Subsaharan contribution most times do so (in average, Afro-Brazilian DNA was reported to be about 50% Subsaharan African, 37% European and 13% Amerindian).[138][139][140][141]

| Ethnic groups in Brazil (census data)[142] | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Ethnic group | white | black | multiracial |

| 1872 | 3,787,289 | 1,954,452 | 4,188,737 |

| 1940 | 26,171,778 | 6,035,869 | 8,744,365 |

| 1991 | 75,704,927 | 7,335,136 | 62,316,064 |

| Ethnic groups in Brazil (1872 and 1890)[143] | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Years | whites | multiracial | blacks | Indians | Total |

| 1872 | 38.1% | 38.3% | 19.7% | 3.9% | 100% |

| 1890 | 44.0% | 32.4% | 14.6% | 9% | 100% |

If a more consistent report with the genetic groups in the gradation of genetic mixing is to be considered (e.g. that would not cluster people with a balanced degree of African and non-African ancestry in the black group instead of the multiracial one, unlike elsewhere in Latin America where people of high quantity of African descent tend to classify themselves as mixed), more people would report themselves as white and pardo in Brazil (47.7% and 42.4% of the population as of 2010, respectively), because by research its population is believed to have between 65 and 80% of autosomal European ancestry, in average (also >35% of European mt-DNA and >95% of European Y-DNA).[138][144][145][146]

From the last decades of the Empire until the 1950s, the proportion of the white population increased significantly while Brazil welcomed 5.5 million immigrants between 1821 and 1932, not much behind its neighbor Argentina with 6.4 million,[147] and it received more European immigrants in its colonial history than the United States. Between 1500 and 1760, 700.000 Europeans settled in Brazil, while 530.000 Europeans settled in the United States for the same given time.[148] Thus, the historical construction of race in Brazilian society dealt primarily with gradations between persons of majority European ancestry and little minority groups with otherwise lower quantity therefrom in recent times.

European Union

According to the Council of the European Union:

The European Union rejects theories which attempt to determine the existence of separate human races.

— Directive 2000/43/EC[149]

The European Union uses the terms racial origin and ethnic origin synonymously in its documents and according to it «the use of the term ‘racial origin’ in this directive does not imply an acceptance of such [racial] theories».[149][150][full citation needed] Haney López warns that using «race» as a category within the law tends to legitimize its existence in the popular imagination. In the diverse geographic context of Europe, ethnicity and ethnic origin are arguably more resonant and are less encumbered by the ideological baggage associated with «race». In European context, historical resonance of «race» underscores its problematic nature. In some states, it is strongly associated with laws promulgated by the Nazi and Fascist governments in Europe during the 1930s and 1940s. Indeed, in 1996, the European Parliament adopted a resolution stating that «the term should therefore be avoided in all official texts».[151]

The concept of racial origin relies on the notion that human beings can be separated into biologically distinct «races», an idea generally rejected by the scientific community. Since all human beings belong to the same species, the ECRI (European Commission against Racism and Intolerance) rejects theories based on the existence of different «races». However, in its Recommendation ECRI uses this term in order to ensure that those persons who are generally and erroneously perceived as belonging to «another race» are not excluded from the protection provided for by the legislation. The law claims to reject the existence of «race», yet penalize situations where someone is treated less favourably on this ground.[151]

United States

The immigrants to the United States came from every region of Europe, Africa, and Asia. They mixed among themselves and with the indigenous inhabitants of the continent. In the United States most people who self-identify as African American have some European ancestors, while many people who identify as European American have some African or Amerindian ancestors.

Since the early history of the United States, Amerindians, African Americans, and European Americans have been classified as belonging to different races. Efforts to track mixing between groups led to a proliferation of categories, such as mulatto and octoroon. The criteria for membership in these races diverged in the late 19th century. During the Reconstruction era, increasing numbers of Americans began to consider anyone with «one drop» of known «Black blood» to be Black, regardless of appearance. By the early 20th century, this notion was made statutory in many states. Amerindians continue to be defined by a certain percentage of «Indian blood» (called blood quantum). To be White one had to have perceived «pure» White ancestry. The one-drop rule or hypodescent rule refers to the convention of defining a person as racially black if he or she has any known African ancestry. This rule meant that those that were mixed race but with some discernible African ancestry were defined as black. The one-drop rule is specific to not only those with African ancestry but to the United States, making it a particularly African-American experience.[152]

The decennial censuses conducted since 1790 in the United States created an incentive to establish racial categories and fit people into these categories.[153]

The term «Hispanic» as an ethnonym emerged in the 20th century with the rise of migration of laborers from the Spanish-speaking countries of Latin America to the United States. Today, the word «Latino» is often used as a synonym for «Hispanic». The definitions of both terms are non-race specific, and include people who consider themselves to be of distinct races (Black, White, Amerindian, Asian, and mixed groups).[154] However, there is a common misconception in the US that Hispanic/Latino is a race[155] or sometimes even that national origins such as Mexican, Cuban, Colombian, Salvadoran, etc. are races. In contrast to «Latino» or «Hispanic», «Anglo» refers to non-Hispanic White Americans or non-Hispanic European Americans, most of whom speak the English language but are not necessarily of English descent.

Views across disciplines over time

Anthropology

The concept of race classification in physical anthropology lost credibility around the 1960s and is now considered untenable.[156][157][158] A 2019 statement by the American Association of Physical Anthropologists declares:

Race does not provide an accurate representation of human biological variation. It was never accurate in the past, and it remains inaccurate when referencing contemporary human populations. Humans are not divided biologically into distinct continental types or racial genetic clusters. Instead, the Western concept of race must be understood as a classification system that emerged from, and in support of, European colonialism, oppression, and discrimination.[83]

Wagner et al. (2017) surveyed 3,286 American anthropologists’ views on race and genetics, including both cultural and biological anthropologists. They found a consensus among them that biological races do not exist in humans, but that race does exist insofar as the social experiences of members of different races can have significant effects on health.[159]

Wang, Štrkalj et al. (2003) examined the use of race as a biological concept in research papers published in China’s only biological anthropology journal, Acta Anthropologica Sinica. The study showed that the race concept was widely used among Chinese anthropologists.[160][161] In a 2007 review paper, Štrkalj suggested that the stark contrast of the racial approach between the United States and China was due to the fact that race is a factor for social cohesion among the ethnically diverse people of China, whereas «race» is a very sensitive issue in America and the racial approach is considered to undermine social cohesion – with the result that in the socio-political context of US academics scientists are encouraged not to use racial categories, whereas in China they are encouraged to use them.[162]

Lieberman et al. in a 2004 study researched the acceptance of race as a concept among anthropologists in the United States, Canada, the Spanish speaking areas, Europe, Russia and China. Rejection of race ranged from high to low, with the highest rejection rate in the United States and Canada, a moderate rejection rate in Europe, and the lowest rejection rate in Russia and China. Methods used in the studies reported included questionnaires and content analysis.[20]

Kaszycka et al. (2009) in 2002–2003 surveyed European anthropologists’ opinions toward the biological race concept. Three factors, country of academic education, discipline, and age, were found to be significant in differentiating the replies. Those educated in Western Europe, physical anthropologists, and middle-aged persons rejected race more frequently than those educated in Eastern Europe, people in other branches of science, and those from both younger and older generations.» The survey shows that the views on race are sociopolitically (ideologically) influenced and highly dependent on education.»[163]

United States

Since the second half of the 20th century, physical anthropology in the United States has moved away from a typological understanding of human biological diversity towards a genomic and population-based perspective. Anthropologists have tended to understand race as a social classification of humans based on phenotype and ancestry as well as cultural factors, as the concept is understood in the social sciences.[89][157] Since 1932, an increasing number of college textbooks introducing physical anthropology have rejected race as a valid concept: from 1932 to 1976, only seven out of thirty-two rejected race; from 1975 to 1984, thirteen out of thirty-three rejected race; from 1985 to 1993, thirteen out of nineteen rejected race. According to one academic journal entry, where 78 percent of the articles in the 1931 Journal of Physical Anthropology employed these or nearly synonymous terms reflecting a bio-race paradigm, only 36 percent did so in 1965, and just 28 percent did in 1996.[164]

A 1998 «Statement on ‘Race'» composed by a select committee of anthropologists and issued by the executive board of the American Anthropological Association, which they argue «represents generally the contemporary thinking and scholarly positions of a majority of anthropologists», declares:[165]

In the United States both scholars and the general public have been conditioned to viewing human races as natural and separate divisions within the human species based on visible physical differences. With the vast expansion of scientific knowledge in this century, however, it has become clear that human populations are not unambiguous, clearly demarcated, biologically distinct groups. Evidence from the analysis of genetics (e.g., DNA) indicates that most physical variation, about 94%, lies within so-called racial groups. Conventional geographic «racial» groupings differ from one another only in about 6% of their genes. This means that there is greater variation within «racial» groups than between them. In neighboring populations there is much overlapping of genes and their phenotypic (physical) expressions. Throughout history whenever different groups have come into contact, they have interbred. The continued sharing of genetic materials has maintained all of humankind as a single species. […]

With the vast expansion of scientific knowledge in this century, … it has become clear that human populations are not unambiguous, clearly demarcated, biologically distinct groups. […] Given what we know about the capacity of normal humans to achieve and function within any culture, we conclude that present-day inequalities between so-called «racial» groups are not consequences of their biological inheritance but products of historical and contemporary social, economic, educational, and political circumstances.

An earlier survey, conducted in 1985 (Lieberman et al. 1992), asked 1,200 American scientists how many disagree with the following proposition: «There are biological races in the species Homo sapiens.» Among anthropologists, the responses were:

- physical anthropologists: 41%

- cultural anthropologists: 53%[166]

Lieberman’s study also showed that more women reject the concept of race than men.[167]

The same survey, conducted again in 1999,[168] showed that the number of anthropologists disagreeing with the idea of biological race had risen substantially. The results were as follows:

- physical anthropologists: 69%

- cultural anthropologists: 80%

A line of research conducted by Cartmill (1998), however, seemed to limit the scope of Lieberman’s finding that there was «a significant degree of change in the status of the race concept». Goran Štrkalj has argued that this may be because Lieberman and collaborators had looked at all the members of the American Anthropological Association irrespective of their field of research interest, while Cartmill had looked specifically at biological anthropologists interested in human variation.[169]

In 2007, Ann Morning interviewed over 40 American biologists and anthropologists and found significant disagreements over the nature of race, with no one viewpoint holding a majority among either group. Morning also argues that a third position, «antiessentialism», which holds that race is not a useful concept for biologists, should be introduced into this debate in addition to «constructionism» and «essentialism».

According to the 2000 University of Wyoming edition of a popular physical anthropology textbook, forensic anthropologists are overwhelmingly in support of the idea of the basic biological reality of human races.[171] Forensic physical anthropologist and professor George W. Gill has said that the idea that race is only skin deep «is simply not true, as any experienced forensic anthropologist will affirm» and «Many morphological features tend to follow geographic boundaries coinciding often with climatic zones. This is not surprising since the selective forces of climate are probably the primary forces of nature that have shaped human races with regard not only to skin color and hair form but also the underlying bony structures of the nose, cheekbones, etc. (For example, more prominent noses humidify air better.)» While he can see good arguments for both sides, the complete denial of the opposing evidence «seems to stem largely from socio-political motivation and not science at all». He also states that many biological anthropologists see races as real yet «not one introductory textbook of physical anthropology even presents that perspective as a possibility. In a case as flagrant as this, we are not dealing with science but rather with blatant, politically motivated censorship».[171]

In partial response to Gill’s statement, Professor of Biological Anthropology C. Loring Brace argues that the reason laymen and biological anthropologists can determine the geographic ancestry of an individual can be explained by the fact that biological characteristics are clinally distributed across the planet, and that does not translate into the concept of race. He states:

Well, you may ask, why can’t we call those regional patterns «races»? In fact, we can and do, but it does not make them coherent biological entities. «Races» defined in such a way are products of our perceptions. … We realize that in the extremes of our transit – Moscow to Nairobi, perhaps – there is a major but gradual change in skin color from what we euphemistically call white to black, and that this is related to the latitudinal difference in the intensity of the ultraviolet component of sunlight. What we do not see, however, is the myriad other traits that are distributed in a fashion quite unrelated to the intensity of ultraviolet radiation. Where skin color is concerned, all the northern populations of the Old World are lighter than the long-term inhabitants near the equator. Although Europeans and Chinese are obviously different, in skin color they are closer to each other than either is to equatorial Africans. But if we test the distribution of the widely known ABO blood-group system, then Europeans and Africans are closer to each other than either is to Chinese.[172]

The concept of «race» is still sometimes used within forensic anthropology (when analyzing skeletal remains), biomedical research, and race-based medicine.[173][174] Brace has criticized forensic anthropologists for this, arguing that they in fact should be talking about regional ancestry. He argues that while forensic anthropologists can determine that a skeletal remain comes from a person with ancestors in a specific region of Africa, categorizing that skeletal as being «black» is a socially constructed category that is only meaningful in the particular social context of the United States, and which is not itself scientifically valid.[175]

Biology, anatomy, and medicine

In the same 1985 survey (Lieberman et al. 1992), 16% of the surveyed biologists and 36% of the surveyed developmental psychologists disagreed with the proposition: «There are biological races in the species Homo sapiens.»

The authors of the study also examined 77 college textbooks in biology and 69 in physical anthropology published between 1932 and 1989. Physical anthropology texts argued that biological races exist until the 1970s, when they began to argue that races do not exist. In contrast, biology textbooks did not undergo such a reversal but many instead dropped their discussion of race altogether. The authors attributed this to biologists trying to avoid discussing the political implications of racial classifications, and to the ongoing discussions in biology about the validity of the idea of «subspecies». The authors concluded, «The concept of race, masking the overwhelming genetic similarity of all peoples and the mosaic patterns of variation that do not correspond to racial divisions, is not only socially dysfunctional but is biologically indefensible as well (pp. 5 18–5 19).»(Lieberman et al. 1992, pp. 316–17)

A 1994 examination of 32 English sport/exercise science textbooks found that 7 (21.9%) claimed that there are biophysical differences due to race that might explain differences in sports performance, 24 (75%) did not mention nor refute the concept, and 1 (3.1%) expressed caution with the idea.[176]

In February 2001, the editors of Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine asked «authors to not use race and ethnicity when there is no biological, scientific, or sociological reason for doing so.»[177] The editors also stated that «analysis by race and ethnicity has become an analytical knee-jerk reflex.»[178] Nature Genetics now ask authors to «explain why they make use of particular ethnic groups or populations, and how classification was achieved.»[179]

Morning (2008) looked at high school biology textbooks during the 1952–2002 period and initially found a similar pattern with only 35% directly discussing race in the 1983–92 period from initially 92% doing so. However, this has increased somewhat after this to 43%. More indirect and brief discussions of race in the context of medical disorders have increased from none to 93% of textbooks. In general, the material on race has moved from surface traits to genetics and evolutionary history. The study argues that the textbooks’ fundamental message about the existence of races has changed little.[180]

Surveying views on race in the scientific community in 2008, Morning concluded that biologists had failed to come to a clear consensus, and they often split along cultural and demographic lines. She notes, «At best, one can conclude that biologists and anthropologists now appear equally divided in their beliefs about the nature of race.»

Gissis (2008) examined several important American and British journals in genetics, epidemiology and medicine for their content during the 1946–2003 period. He wrote that «Based upon my findings I argue that the category of race only seemingly disappeared from scientific discourse after World War II and has had a fluctuating yet continuous use during the time span from 1946 to 2003, and has even become more pronounced from the early 1970s on«.[181]

33 health services researchers from differing geographic regions were interviewed in a 2008 study. The researchers recognized the problems with racial and ethnic variables but the majority still believed these variables were necessary and useful.[182]

A 2010 examination of 18 widely used English anatomy textbooks found that they all represented human biological variation in superficial and outdated ways, many of them making use of the race concept in ways that were current in 1950s anthropology. The authors recommended that anatomical education should describe human anatomical variation in more detail and rely on newer research that demonstrates the inadequacies of simple racial typologies.[183]

A 2021 study that examined over 11,000 papers from 1949 to 2018 in The American Journal of Human Genetics, found that «race» was used in only 5% of papers published in the last decade, down from 22% in the first. Together with an increase in use of the terms «ethnicity,» «ancestry,» and location-based terms, it suggests that human geneticists have mostly abandoned the term «race.»[184]

Sociology