From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

The Tale of Igor’s Campaign or The Tale of Ihor’s Campaign[1] (Old East Slavic: Слово о пълкѹ Игоревѣ, romanized: Slovo o pŭlku Igorevě) is an anonymous epic poem written in the Old East Slavic language.

The title is occasionally translated as The Tale of the Campaign of Igor, The Song of Igor’s Campaign, The Lay of Igor’s Campaign, The Lay of the Host of Igor, and The Lay of the Warfare Waged by Igor.

The poem gives an account of a failed raid of Igor Svyatoslavich (d. 1202) against the Polovtsians of the Don River region.

While some have disputed the authenticity of the poem, the current scholarly consensus is that the poem is authentic and dates to the Middle Ages (late 12th century).[2]

The Tale of Igor’s Campaign was adapted by Alexander Borodin as an opera and became one of the great classics of Russian theatre. Entitled Prince Igor, it was first performed in 1890.

Content[edit]

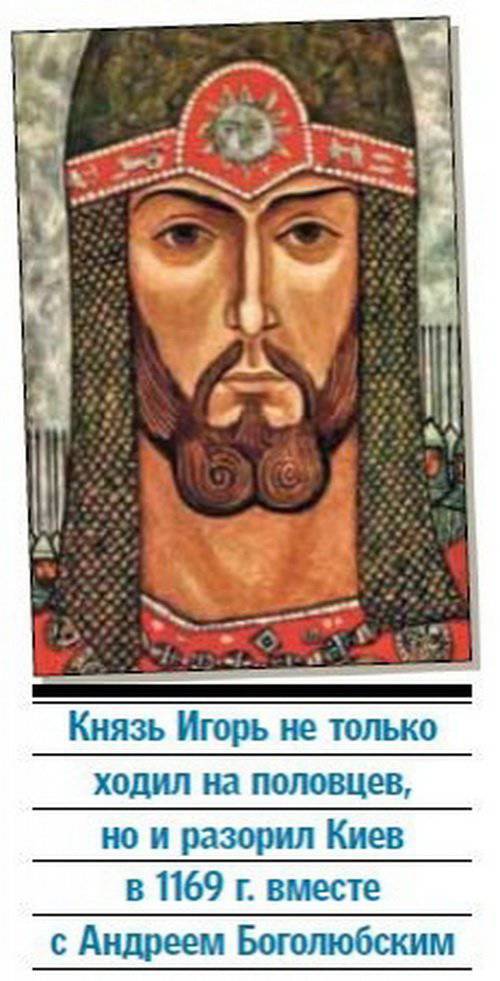

The story describes a failed raid made in year 1185 by Kniaz Igor Svyatoslavich, Prince of Novgorod-Seversk, on the Polovtsians living along the lower Don. Other Rus’ historical figures are mentioned, including skald Boyan (The Bard), the princes Vseslav of Polotsk, Yaroslav Osmomysl of Halych, and Vsevolod the Big Nest of Suzdal. The author appeals to the warring Rus’ princes and pleads for unity in the face of the constant threat from the Turkic East. Igor’s campaign is recorded in the Kievan Chronicle (c. 1200).

The descriptions show coexistence between Christianity and ancient Slavic religion. Igor’s wife Yaroslavna invokes natural forces from the walls of Putyvl. Christian motifs are presented along with depersonalised pagan gods among the artistic images. The main themes of the story are patriotism, the power and role of nature (at the time of the story, 12th century) and homeland. The main idea is the unity of people.[3]

The Tale has been compared to other national epics, including The Song of Roland and The Song of the Nibelungs.[4] The book however differs from contemporary Western epics on account of its numerous and vivid descriptions of nature and the portrayal of the role which nature plays in human lives.

Discovery and publication[edit]

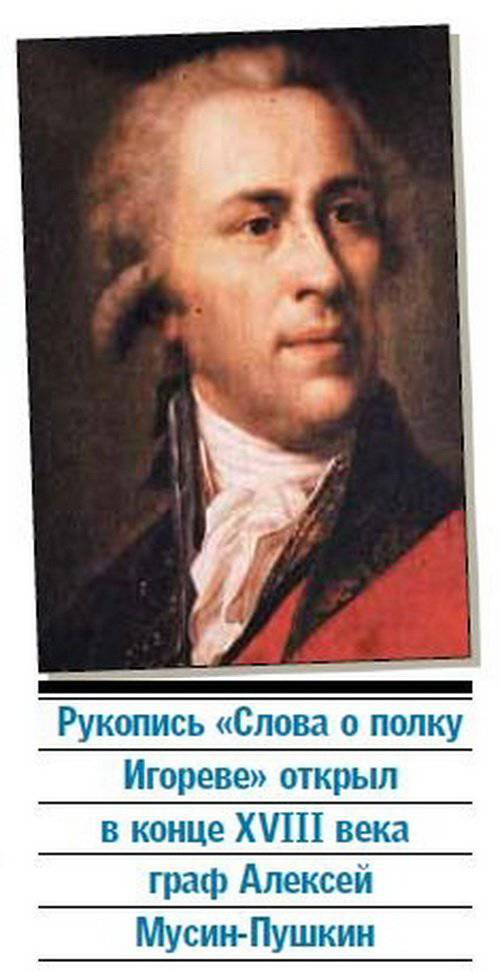

The only manuscript of the Tale, claimed to be dated to the 15th century, was discovered in 1795 in the library of the Transfiguration Monastery in Yaroslavl, where the first library and school in Russia had been established in the 12th century, but there is a controversy about its source.[5] Monastery superior Joel (Bykovsky) sold the manuscript to a local landowner, Aleksei Musin-Pushkin, as a part of a collection of ten texts. Aleksei realised the value of the book and made a transcription for the empress Catherine the Great in 1795 or 1796. He published it in 1800 with the help of Alexei Malinovsky and Nikolai Bantysh-Kamensky, leading Russian paleographers of the time. The original manuscript was claimed to have burned in the great Moscow fire of 1812 (during the Napoleonic occupation), together with Musin-Pushkin’s entire library.

The release of this historical work into scholarly circulation created a stir in Russian literary circles, as the tale represented the earliest Slavonic language writing, without any element of Church Slavonic. After linguistic analysis, Ukrainian scholars[who?] in the Austrian Empire declared that the document contained transitional language between a) earlier fragments of the language of Rus’ propria (the region of Chernigov, eastward through Kiev, and into Halych) and, b) later fragments from the Halych-Volynian era of this same region in the centuries immediately following the writing of the document.

The Russian-American author Vladimir Nabokov translated the work into English in 1960. Other notable editions include the standard Soviet edition, prepared with an extended commentary, by the academician Dmitry Likhachev.

Authenticity debate[edit]

According to the majority view, the poem is a composition of the late 12th century, perhaps composed orally and fixed in written form at some point during the 13th century. Some scholars consider the possibility that the poem in its current form is a national Romanticist compilation and rearrangement of several authentic sources. The thesis of the poem’s being a complete forgery has been proposed in the past but is widely discredited; the poem’s language has been demonstrated to be closer to authentic medieval East Slavic than practicable by a late 18th-century forger. It was not until 1951 that scholars discovered ancient birch bark documents with content in this medieval language.

One of the crucial points of the authenticity controversy is the relationship between The Tale of Igor’s Campaign and Zadonschina, an unquestionably authentic poem, which was created in the end of XIV-XV century to glorify Dmitri Donskoi’s victory over Mongol-Tatar troops of the ruler of the Golden Horde Mamai in the Battle of Kulikovo and is preserved in six medieval copies. There are almost identical passages in both texts where only the personal names are different. The traditional point of view considers Zadonschina to be a late imitation, with Slovo as its pattern. The forgery version claims the reverse: that Igor’s Tale was written using Zadonschina as a source. Recently, Roman Jakobson’s and Andrey Zaliznyak’s analyses show that the passages of Zadonschina with counterparts in Slovo differ from the rest of the text by several linguistic parameters, whereas this is not so for Igor’s Tale. This fact is taken as evidence of Slovo being the original with respect to Zadonschina. Zaliznyak also points out that the passages in Zadonschina which parallel those in the Igor’s Tale but differ from it can be explained only if Slovo was the source for Zadonshchina (the differences can be the result of the distortion of the original Slovo text by the author and different editors of Zadonshchina versions), but not vice versa.

Proponents of the forgery thesis give sometimes contradictory arguments: some authors (Mazon) see numerous Gallicisms in the text; while others (Trost, Haendler) see Germanisms, yet others (Keenan) Bohemisms. Zimin is certain that the author could only be Ioil Bykovsky, while Keenan is equally sure that only Josef Dobrovsky could be the falsifier.

Current dialectology upholds Pskov and Polotsk as the two cities where the Tale was most likely written.[citation needed] Numerous persons have been proposed as its authors, including Prince Igor and his brothers.[citation needed] Other authors consider the epic to have emerged in Southern Rus’, with many elements corresponding to modern Ukrainian language.[6]

Early reactions[edit]

After the only manuscript copy of the Tale was destroyed in the Napoleonic invasion of 1812, questions about its authenticity were raised, mostly because of its language. Suspicion was also fueled by contemporary fabrications (for example, the Songs of Ossian, proved to be written by James Macpherson). Today, majority opinion accepts the authenticity of the text, based on the similarity of its language and imagery with those of other texts discovered after the Tale.

Proposed as forgers were Aleksei Musin-Pushkin, or the Russian manuscript forgers Anton Bardin and Alexander Sulakadzev. (Bardin was publicly exposed as the forger of four copies of Slovo). Josef Sienkowski, a journalist and Orientalist, was one of the notable early proponents of the falsification theory.

Soviet period[edit]

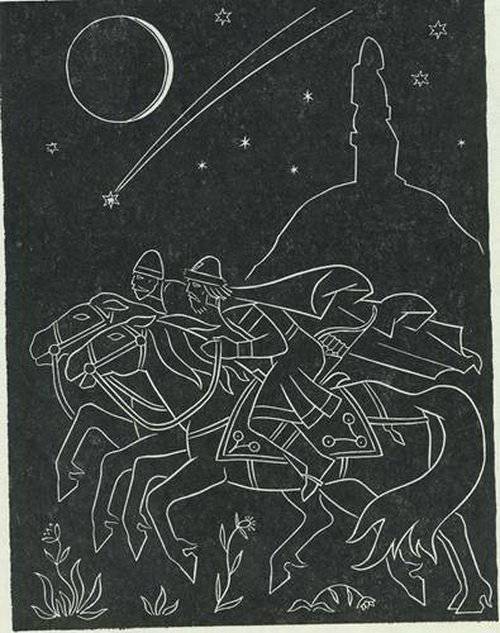

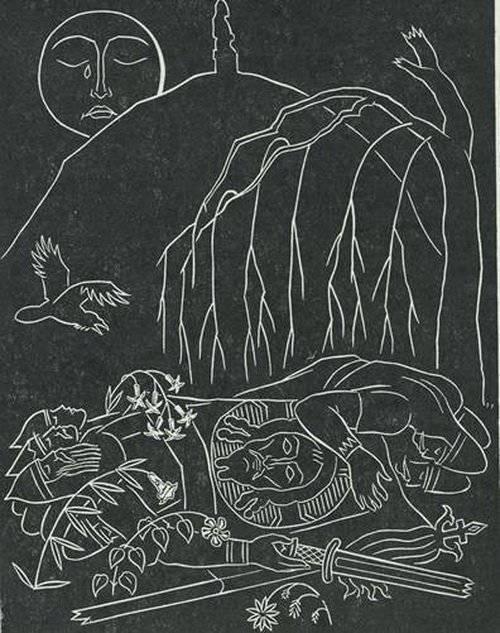

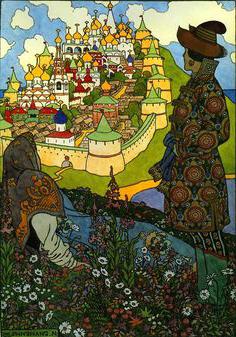

Soviet Russian artist Ivan Bilibin’s illustration to the tale, 1941

The problem of the national text became more politicized during the years of the Soviet Union. Any attempts to question the authenticity of Slovo (for example, by the French Slavist André Mazon or by the Russian historian Alexander Zimin[citation needed]) were condemned. Government officials also repressed and condemned non-standard interpretations based on Turkic lexis, such as was proposed by Oljas Suleimenov (who considered Igor’s Tale to be an authentic text). Mazon’s and Zimin’s views were opposed, for example, by Roman Jakobson.

In 1975 Olzhas Suleimenov challenged the mainstream view of the Tale in his book Az i Ya. He claimed to reveal that Tale cannot be completely authentic since it appeared to have been rewritten in the 16th century.[7][8]

Mainstream Slavists, including Dmitri Likhachev,[9] and Turkologists[10] criticized Az i Ya, characterizing Suleymenov’s etymological and paleography conjectures as amateurish. Linguists such as Zaliznyak pointed out that certain linguistic elements in Slovo dated from the 15th or 16th centuries, when the copy of the original manuscript (or of a copy) had been made. They noted this was a normal feature of copied documents, as copyists introduce elements of their own orthography and grammar, as is known from many other manuscripts. Zaliznyak points out that this evidence constitutes another argument for the authenticity of Slovo. An anonymous forger would have had not only to imitate very complex 12th century orthography and grammar but also to introduce fake complex traces of the copying in the 15th or 16th centuries.

Recent views[edit]

800th anniversary of The Tale on a 1985 USSR commemorative stamp

While some historians and philologists continue to question the text’s authenticity for various reasons (for example, believing that it has an uncharacteristically modern nationalistic sentiment) (Omeljan Pritsak[citation needed] inter alios), linguists are not so skeptical. The overall scholarly consensus accepts Slovo’s authenticity.[clarification needed]

Some scholars believe the Tale has a purpose similar to that of Kralovedvorsky Manuscript.[11] For instance, the Harvard historian Edward L. Keenan says in his article, «Was Iaroslav of Halych really shooting sultans in 1185?» and in his book Josef Dobrovsky and the Origins of the Igor’s Tale (2003), that Igor’s Tale is a fake, written by the Czech scholar Josef Dobrovský.[12]

Other scholars contend that it is a recompilation and manipulation of several authentic sources put together similarly to Lönnrot’s Kalevala.[13]

In his 2004 book, the Russian linguist Andrey Zaliznyak analyzes arguments and concludes that the forgery theory is virtually impossible.[14] It was not until the late 20th century, after hundreds of bark documents were unearthed in Novgorod, that scholars learned that some of the puzzling passages and words of the tale were part of common speech in the 12th century, although they were not represented in chronicles and other formal written documents. Zaliznyak concludes that no 18th-century scholar could have imitated the subtle grammatical and syntactical features in the known text. He did not believe that Dobrovský could have accomplished this, as his views on Slavic grammar (as expressed in his magnum opus, Institutiones) were strikingly different from the system written in Igor’s Tale. In his revised second edition issued in 2007, Zaliznyak was able to use evidence from the posthumous edition of Zimin’s 2006 book. He argued that even someone striving to imitate some older texts would have had almost impossible hurdles to overcome, as mere imitation could not have represented the deep mechanics of the language.[15]

Juri Lotman supports the text’s authenticity, based on the absence of a number of semiotic elements in the Russian Classicist literary tradition before the publication of the Tale. He notes that «Russian Land» (русская земля) was a term that became popular only in the 19th century. A presumed forger of the 1780s–1790s would not have used such a term while composing the text.[16]

Orality[edit]

Robert Mann (1989, 2005) argues that the leading studies have been mistaken in concluding the Tale is the work of a poet working in a written tradition. Mann points to evidence suggesting that the Tale first circulated as an oral epic song for several decades before being written down, most likely in the early 13th century. He identifies the opening lines as corresponding to such an oral tradition: «Was it not fitting, brothers, to begin with the olden words of the heroic tales about the campaign of Igor…» The narrator begins by referring to oral epic tales that are already old and familiar. Mann has found numerous new parallels to the text of the Tale in wedding songs, magical incantations, byliny and other Old Russian sources. He was the first researcher to point out unique textual parallels in a rare version of the Tale of the Battle against Mamai (Skazanie o Mamaevom poboishche), published by N.G. Golovin in 1835. It contains what Mann claims is the earliest known redaction of the Skazanie, a redaction that scholars posited but could not locate.

Based on byliny and Old Russian sources, Mann has attempted to reconstruct an early Russian song about the conversion of the Kievan State. Mann believes that this early conversion cycle left its imprint on several passages of the Tale, including the motif sequence in which the pagan Div warns the Tmutorokan idol that Igor’s army is approaching.[17][18]

Editions and translations[edit]

- Aleksei Musin-Pushkin, Alexei Malinovsky and Nikolai Bantysh-Kamensky, Ироическая пѣснь о походѣ на половцовъ удѣльнаго князя Новагорода-Сѣверскаго Игоря Святославича, писанная стариннымъ русскимъ языкомъ въ исходѣ XII столѣтія съ переложеніемъ на употребляемое нынѣ нарѣчіе. Moscow, in senatorial typography. (1800)

- Mansvetus Riedl, Szozat Igor hadjaratarul a paloczok ellen (1858)

- Leonard A. Magnus, The Tale of the Armament of Igor (1915)

- Eduard Sievers, Das Igorlied (1926)

- Karl Heinrich Meyer, Das Igorlied (1933)

- Henri Grégoire, Roman Jakobson, Marc Szeftel, J. A. Joffe, La Geste du prince Igor, Annuaire de l’Institut de philologie et ď histoire orientales et slaves, t. VIII. (1948)

- Dmitry Likhachev, Слова о полку Игореве, Литературные памятники (1950)

- Vladimir Nabokov, The Song of Igor’s Campaign: An Epic of the 12th Century (1960)

- Dimitri Obolensky, The Lay of Igor’s Campaign — of Igor the Son of Svyatoslav and the Grandson of Oleg (translation alongside original text), in The Penguin Book of Russian Verse (1962)

- Robert Howes, The Tale of the Campaign of Igor (1973)

- Serge Zenkovsky, «The Lay of Igor’s Campaign», in Medieval Russia’s Epics, Chronicles, and Tales (Revised edition, 1974)

- Dmitry Likhachev, Слова о полку Игореве, (Old Russian into English by Irina Petrova ), (illustrated by Vladimir Favorsky), «The Lay of the Warfare Waged by Igor», Progress Publishers (Moscow, revised edition, 1981)

- J. A. V. Haney and Eric Dahl, The Discourse on Igor’s Campaign: A Translation of the Slovo o polku Igoreve. (1989)

- J. A. V. Haney and Eric Dahl, On the Campaign of Igor: A Translation of the Slovo o polku Igoreve. (1992)

- Robert Mann, The Igor Tales and Their Folkloric Background (2005)

See also[edit]

- Prince Igor

- Prince Igor (1969 film)

- Old East Slavic language

- Solar eclipse of 1 May 1185

- Musin-Pushkin House (Saint Petersburg)

Notes[edit]

- ^ Katchanovski, Ivan; Kohut, Zenon E.; Nesebio, Bohdan Y.; Yurkevich, Myroslav (2013). Historical Dictionary of Ukraine. Lanham, Maryland; Toronto; Plymouth: Scarecrow Press. p. 197. ISBN 9780810878471. Retrieved 22 January 2023.

- ^ The poem proposes to cover the tale «from the elder Vladímir up to our contemporary Ígoŕ» (отъ стараго Владимера до нынѣшняго Игоря), indicating composition before Svyatoslavich’s death in 1202.

- ^ «Слово о полку Игореве ⋆ краткое содержание, о произведении». СПАДИЛО (in Russian). Retrieved 2022-08-11.

- ^ Likhachev. «‘Слово о полку Игореве'», p. 16.

- ^ Kotlyar, M. A word about the Igor’s Army (СЛОВО О ПОЛКУ ІГОРЕВІМ). Encyclopedia of History of Ukraine.

- ^ Dragomanov M. Little Russia in its literature (Малороссия в ее словесности: Малороссия /Южная Русь/ в истории ее литературы с XI по XVIII век Й. Г. Прыжова. Воронеж, 1869. // Вестник Европы. — 1870.)

- ^ (in Russian) Сон Святослава. Татарская электронная библиотека.

- ^ (in Russian) Царь Додон и Геродот. Татарская электронная библиотека.

- ^ (in Russian) Likhachev, Dmitri S. «‘Слово о полку Игореве’ в интерпретации О.Сулейменова» in Русская литература (Russian Literature). Leningrad: Nauka, 1985, p. 257.

- ^ (in Russian) Baskakov, Nikolay A. «Слово о полку Игореве» in Памятники литературы и искусства XI-XVII веков (Literary Monuments and Art in the Eleventh to Seventeenth Centuries). Moscow, 1978, pp. 59–68.

- ^ Pospíšil, Ivo: Slovo o pluku Igorově v kontextu současných výzkumů, Slavica Slovaca, Volume 42, No. 1, 2007, pp. 37–48.

- ^ Keenan, E. L.: Josef Dobrovský and the Origins of the ‘Igor Tale’, Harvard University Press, 2003.

- ^ (in Russian) «Проблема подлинности ‘Слова о полку Игореве’ и ‘Ефросин Белозерский’ Archived 2015-09-23 at the Wayback Machine» (The Problem of the Authenticity of ‘A Word about the Leader Igorev’ and ‘Efrosin Belozerskij’), Acta Slavica Iaponica, Issue: 22, 2005, pp. 238–297.

- ^ (in Russian) Zaliznyak, Andrey. Слово о полку Игореве: взгляд лингвиста (Языки Славянской). Moscow: Kultura Publishing, 2004.

- ^ З(in Russian) Zaliznyak, Andrey. «Слово о полку Игореве»: взгляд лингвиста. Изд. 3-е, дополн. М.: «Рукописные памятники Древней Руси», 2008.

- ^ Ю. М. Лотман «СЛОВО О ПОЛКУ ИГОРЕВЕ» И ЛИТЕРАТУРНАЯ ТРАДИЦИЯ XVIII — НАЧАЛА XIX в.

- ^ See Mann, Robert; Lances Sing: A Study of the Old Russian Igor Tale. Slavica: Columbus, 1989.

- ^ Mann, Robert. The Igor Tales and Their Folkloric Background. Jupiter, FL: The Birchbark Press of Karacharovo, 2005.

Further reading[edit]

- Magnus, Leonard Arthur. The Tale of the Armament of Igor. Oxford University Press, 1915. The first English translation.

- Mann, Robert. Lances Sing: A Study of the Old Russian Igor Tale. Slavica: Columbus, 1989.

- Mann, Robert. The Igor Tales and Their Folkloric Background. Jupiter, FL: The Birchbark Press of Karacharovo, 2005.

- Mann, Robert. The Silent Debate Over the Igor Tale. Oral Tradition 30.1:53-94, 2016. Link to article

- (in Russian) Pesn’ o polku Igoreve: Novye otkrytiia. Moscow: Iazyki Slavianskoi Kul’tury, 2009.

External links[edit]

- The original edition of 1800

- Roman Jacobson’s edition

- Vladimir Nabokov’s edition

- 1800 edition, plus 4 more contemporary Russian language translations

- Old East Slavic text and various Russian and Ukrainian translations and interpretations

- Leonard Magnus English translation of 1915, parallel English/Russian

- Katherine Owen, «The Lay of Igor’s Campaign and the Works It Has Inspired», Analysis of artistic adaptations

- The House of Count Aleksei Musin-Pushkin (1744-1818) in St. Petersburg. Here was stored the Tale of Igor’s Campaign

In the same places where battles are fought today in the Donbass, Prince Igor was captured by the Polovtsy. It happened in the area of salt lakes near Slavyansk.

Among the ancient Russian books, one always caused mystical horror in me — “The Word about the regiment of Igor”. I read it in early childhood. Eight years old. In the Ukrainian translation of Maxim Rylsky. This is a very strong translation, not much inferior to the original: “Having looked at Igor on the sun, that was the first thing to do — vysko darkness began to smoke, saying to friends:“ Brattya my, my friends! Luchche us chopped up boutiques, nizh is full of love! ” And here it is: “O Ruska to the earth, already ty behind the grave!” (In Old Russian, since it was not the translator who wrote, but the author of the great poem himself, the last phrase reads: “O Ruska for the earth, already behind the Shelomianem!”) . «Silk» is a hill that looks like a helmet, a tall grave in the steppe.

What terrified me? Do not believe it: most of all, even then I was afraid that the “times of the first strife” would return and my brother and brother would rise. Was this a premonition of what awaits our generation? I grew up in the Soviet Union — one of the strongest states in the world. The sense of security that the Soviet people had then, the current Ukrainian children can not even imagine. Wall of China in the Far East. Western group of Soviet troops in Germany. Nuclear shield overhead. And the song: “May there always be sunshine! May I always be! ”

At school we were taught that Kievan Rus was the cradle of three fraternal peoples. In Moscow, the rules of Brezhnev — came from Dnepropetrovsk. There was no reason to doubt that the nations are fraternal. The Moscow engineer received as much as the Kiev engineer. Dynamo Lobanovsky won one USSR championship after another. A bum not only on Khreshchatyk (nowhere in Kiev!) Was to be found day or night. And yet I was afraid. I was afraid that this undeserved happiness would go away. Smoot, feudal fragmentation — these words haunted me even then, like a nightmare. Probably, I had a gift of premonition.

And when in the 1991 year in Belovezhskaya Pushcha three new “feudal lords” divided us, like the princes of Smerds once were, and we only silently listened, and the borders lay between the former fraternal republics, I remembered “Word of the Regiment …” again. And he constantly recalled in the “gangster 90”, when new “princes” shared everything around, as did Igor’s contemporaries. Didn’t it sound modern? ”“ Brother began to say to brother: “This is mine! And that is also mine! ” And the princes started for a small «very great» rumor, and forged themselves to sedition, and the rushes from all countries came with victories to the land of Ruskaya «? The author of «The Word …» determined the whole essence of our troubles 800 years ago, at the end of the XII century.

After long oblivion, «The Word of Igor’s Regiment» was discovered in 90 of the 18th century by Count Musin-Pushkin, a former adjutant of Catherine’s favorite Grigory Orlov. Upon his retirement, he began collecting old books and came across a manuscript collection in one of the monastic libraries near Yaroslavl. It contained the same mysterious text, which is now known to anyone.

The find caused a sensation. Patriots of Russia exulted. Finally, we have unearthed a masterpiece, comparable to the French «Song of Roland.» And maybe even better! Young Karamzin posted an enthusiastic note in the Hamburg Observer of the North, where there were such words: “In our archives we found an excerpt from the poem“ Song to Igor Soldiers ”, which can be compared with the best Ossian poems and which was written in the XII century by an unknown writer” .

TWO-LOOK IGOR. Almost immediately doubts arose about the authenticity of the poem. The manuscript of The Tale of the Battle of Igoreve burned down in Moscow in 1812, during the war with Napoleon. All subsequent reprints were made on the first printed edition of 1800 of the year, entitled «The Iroic Song of the Campaign against the Polovtsy, the Prince of Novgorod-Seversky, Igor Svyatoslavich.» Not surprisingly, it was the French who later began to assert that the “Word …” was a fake. Who wants to admit that your countrymen destroyed, like barbarians, the great Slavic masterpiece?

Chivalrous Igor, however, was not as white as the author of the Lay … portrays him. He caused sympathy in Russia when he became a victim — he was captured by the Polovtsy. We always forgive the former sins of the sufferers.

In the 1169 year, according to the Tale of Bygone Years, the young Igor Svyatoslavich was among the gang of princes who robbed Kiev. The initiator of the attack was Suzdal Prince Andrei Bogolyubsky. Subsequently, already in the 20th century, some of the nationalist Ukrainian historians tried to present this campaign as the first hit by the “Muscovites”. But in fact, Moscow at that time was just a small Ostrohk, who did not decide anything, and for some reason in the allegedly “moskal” army next to Andrei Bogolyubsky’s son Mstislav, for some reason, Rurik from Ovruch’s Ukrainian, David Rostislavich from Vyshgorod turned out to be Kiev!) And 19-year-old Chernigov Igor with his brothers — the eldest Oleg and the youngest — the future “buy-tour” Vsevolod.

The defeat of Kiev was terrible. According to the Ipatiev Chronicle, they robbed all day, no worse than Polovtsy: temples were burned, Christians were killed, women were separated from their husbands and roared children were taken into captivity under crying: “And they took the goods without account, and the church , and the bells were filmed by all these Smolensk citizens, and Suzdalians, and Chernigov, and Oleg’s squad … 3 even the Pechersk monastery was burned … And there was a moan and sadness, and grief that never stopped, and never-ending tears in Kiev among all people. ” In a word, also strife and grief too.

And in 1184, Igor again “distinguished himself”. The Grand Duke of Kiev Svyatoslav sent a combined Russian army to the Polovtsy. The future hero of the poem with his brother, Vsevolod’s inseparable «buy-tour», also participated in the campaign. But as soon as the allies plunged into the steppe, a discussion about methods of dividing up the loot broke out between Prince Vladimir of Pereyaslav and our hero. Vladimir demanded that he be given a place in the forefront — the advanced parts always get more production. Igor, who replaced the Grand Duke in the campaign, categorically refused. Then Vladimir, spitting on the patriotic duty, turned back and began to rob Igor’s Seversk principality — not to return home without trophies! Igor, too, did not remain in debt and, forgetting about the Polovtsy, in turn pounced on the possessions of Vladimir — Pereyaslavl town of Gleb, who captured, not sparing anyone.

Defeat and escape. Illustrations by artist I. Selivanov to «The Word about Igor’s Regiment».

Lake near Slavyansk. On these shores, Igor and his brother Vsevolod fought with the Polovtsy. In the same places where battles are fought today in the Donbass, Prince Igor was captured by the Polovtsy. It happened in the area of salt lakes near Slavyansk

KARA FOR INTER-SPACE. And the following year, the same ill-fated campaign, based on which a great poem was created, happened. That’s just behind the scenes that the composition of the Ipatiev Chronicle contains a work interpreting Igor’s failure from a much more realistic position. By historians, it is conventionally called the «Tale of Igor Svyatoslavich’s campaign against the Polovtsy». And an unknown author regards him as a captive of the Novgorod-Seversky prince as a fair punishment for the pillaged Russian city of Glebov.

Unlike «The Word …», where much is given only by a hint, «The Tale of the Hike …» is a detailed report. Igor in it is expressed not by stilted calm, but quite prosaically. In «The Word …» he is broadcasting: «I want a spear to break the edge of the Polovetsky field with you, Rusich, I want to either lay my head down, or drink a helmet from the Don!» And in the «Tale …» just afraid of the rumor of the people and makes a rash decision to continue the campaign despite the eclipse of the sun, promising failure: «If we are not beating, to return, then we will be ashamed of death worse. Let, as God wills.

God gave captivity. The author of «The Word …» briefly mentions: «Here Prince Igor moved from slavery to the saddle of gold in the saddle.» The chronicler in “The Tale …” narrates in detail how the leader of a Russian army disintegrating in front of his eyes tries to turn his light cavalry, “kovuys” (one of his vassal steppe tribes), but without catching up with them, falls into the hands of Polovtsy “on the distance of one flight of an arrow ”from its main forces:“ And Igor, caught, saw his brother Vsevolod, who fought hard, and he asked his soul to die not to see his brother fall. Vsevolod fought so much that even weapons in his hand was not enough, and they fought, going around the lake «.

Here on the presumptuous adventurer, according to the chronicler, finds repentance. “And then Igor:“ I remembered my sins before my Lord God, how many murders, bloodshed I created on Christian earth, as I did not spare the Christians, but took the city of Gleb from Pereyaslavl to shield. Then a lot of evil experienced innocent Christians — weaned fathers from children, brother from brother, friend from friend, wives from husbands, daughters from mothers, girlfriends from girlfriends, and everything was crushed by captivity and sorrow. The living envied the dead, and the dead rejoiced, like holy martyrs, with the fire from this life accepting the ordeal. The elders were dying to break, their husbands were chopped and cut, and their wives were desecrated. And all this I did! I am not worthy of life. But now I see vengeance on me! ”

Not so simple were the relationship between Igor and the Polovtsy. According to one of the versions, he himself was the son of Polovchanka. Be that as it may, the Novgorod-Seversky prince willingly entered into alliances with the steppe inhabitants. And no less often than he fought with them. Exactly five years before being captured by the Polovtsian khan Konchak, Igor, together with the same Konchak, set off together to raid Smolensk princes. Having suffered a defeat on the Chertorii River, they literally found themselves in the same boat. Both the Polovtsian Khan and the Russian prince, sitting next to each other, fled from the battlefield. Today — allies. Tomorrow is the enemy.

Yes, and in captivity at Konchak in 1185, the hero of the “Word of the Regiment …” was by no means disastrous. He even managed to marry his son Vladimir to the daughter of this Khan. Like, what time to lose? The crow was pecking out the eyes of the dead warriors in the steppe, and the prince had already negotiated with the enemy about the future for himself and his inheritance in Novgorod-Seversky. They probably sat next to Konchak in a yurt, drank mare’s milk, bargained about the terms of the deal. And when everything was already decided, and the Orthodox priest married the prince and Polovchan, who converted to Christianity, Igor, taking advantage of the gullibility of the steppe people, at night, together with the sympathetic Polovtsi Ovlur, jumped on their horses when everyone was asleep, and rushed to Russia: Polovtsian land on the land of Ruska … The evening dawn was extinguished. Igor is sleeping. Igor stands out Igor thinks of the field from the great Don to the small Donets. Ovlur horsemen whistled behind the river, told the prince to understand … Igor flew down as a falcon, Ovlur flowed like a wolf, shaking off the icy dew, tearing his swift horses … ”.

Who had to get up at night in the steppe and walk on the grass, dropping dew, he would appreciate the poetry of this scene. And the one who never slept in the steppe will probably want to go to the steppe …

After fleeing from captivity, Igor will live 18 for years and will even become a Chernigov prince. Immediately after the death of Igor in 1203, his brother — that same “buoy-tour Vsevolod” together “with the whole Polovtsian land”, as the Laurentian chronicle writes, will go on a campaign to Kiev: “And they burned and burned not only Podol, but also Gore and the Metropolis of St. Sophia was robbed and the Tithing of the Holy Divine plundered and the monasteries and icons stripped … «. According to the chronicler, «they did a great evil in the Russian land, which was not the case from the baptism over Kiev itself.»

AGAIN AS THEN. I do not want to debunk the poetic images created by the author of the Word about the regiment of Igor. Just pay attention to the fact that Igor was a sinner. There was a lot of blood of his fellow tribesmen on his hands. If he had not gone on his last ill-fated march to the Steppe, he would have remained in the memory of his descendants one of the countless feudal robbers. But rather, I would just get lost in the pages of the annals. Was there such a little minor princes who spent their whole life on strife? But the wounds received not only for his inheritance, but for the whole “land of Russkaya”, a bold escape from captivity, surprised everyone in Kiev and Chernihiv, the subsequent quite decent life as if redeemed the sins of youth. After all, each of us has his last chance, and his finest hour.

But even that is not important. Why did I remember, once again, Igor’s campaign in the Polovtsian land? Yes, because the action of the famous poem, which we don’t think about, all its famous military scenes, take place in the present Donbas — approximately in those places where the city of Slavyansk is today. Igor went to the steppe along the Seversky Donets. He was a Seversky prince — the ruler of a Slavic tribe of northerners. The purpose of his campaign was the Don, whose tributary is the Donets. Somewhere near the salt lakes near today’s Slavyansk, in an area where there is no fresh water, Prince Igor was defeated by the Polovtsy. Most researchers converge precisely on this version of the localization of the place of the chronicle battle — it was precisely between the Veysovym and Repny lakes in 1894 when building the railway through Slavyansk workers dug many human bones and remnants of iron weapons at shallow depths — traces of the famous battle.

All of us, to one degree or another, are descendants of both Rus and Polovtsy. Two thirds of present-day Ukraine is the former Polovtsian land. And only one third — northern — belonged to Russia. And here again in the same places as eight centuries ago, Slavic blood flows. Strife came again. Brother kills brother. What can not fill my soul with sorrow.

«lay» — an outstanding monument of old Russian literature, written in the 12th century. Reading this piece still has a positive impact on people opens new horizons for them.

«lay». History of art

«lay» is a literary masterpiece, a work created in Ancient Rus. This work was written near the beginning of the twelfth century, and in 1795 was found by count Alexei Ivanovich Musin-Pushkin. In 1800 it was printed. The original “Words” has disappeared in a fire in 1812, during the great Patriotic war of Russian people against the French.

Summary of work

Analysis of «the Word about Igor’s regiment» shows that this work has a composition typical of the creations of ancient literature. It includes an introduction and the main part, and a toast.

Intonation is a greeting of the author, the readers, and also slightly reveals the author’s opinion about the events he will describe. The author wants to tell about the campaign of Prince Igor, honestly, without reserve, without unnecessary speculation. A model is the famous artist Bojan who always not only followed ancient epics, but also poetically sang of the contemporary princes.

Analysis of «the Word about Igor’s regiment» briefly shows that the author has outlined the chronological boundaries of the narrative in this way: it tells about the life of Vladimir Svyatoslavich of Kiev, and then smoothly goes on to describe the life of Prince Igor Svyatoslavich.

Recommended

LP — a woman or a man, and is it important?

Those who have ever bothered to become acquainted with the works of the magic of the singer LP, was irrevocably in love with her amazing charisma, emancipation and fascinating game now popular on the ukulele tool. Her real fans have stopped to wonder…

The Song «Gibraltar-Labrador». Meanings and images

The Song «Gibraltar-Labrador» Vyacheslav Butusov became known to the General public in 1997. She became part of the sound track of the famous film by Alexei Balabanov, «Brother 2». Today it listens to the second generation of fans of Russian rock. In…

Ewan McGregor: filmography, biography actor

Audiences love films with participation of actors of the ordinary. So in the eyes of many was Ewan McGregor. His filmography includes more than sixty works, with diverse and multifaceted. Evan with equal success, delves into the images of rich and po…

Story art

The Russian troops sent to fight a formidable opponent Cumans. Before the start of the hike the sun closes the sky, the solar Eclipse begins. Any other resident of the Ancient Russia came to be shocked and refuse from their plans, but Prince Igor is not so. He with his army still goes on ahead. It happened on the first of may 1185. The intent of Igor supports his brother, Bui Tour Vsevolod.

After a certain period of the way, Igor Polovtsian meets an ambush. Their number far exceeds the number of Russian people. But the Russian still start the fight.

Igor and Bui tour Vsevolod win in the first battle against the Polovtsy. Satisfied, they let themselves relax. But they do not see and do not feel that their strength is dried up, and the number of the Polovtsian troops still exceeds the number of Russian many times. The next day the Polovtsian troops attack the Russian army and defeat it. Many Russian soldiers were killed, Prince Igor is taken prisoner.

Throughout the Russian land is a lament for the dead, and Cumans, victorious in battle, triumphant. Victory over the army Polovtsev Igor was Russian land caused a lot of misery. Many soldiers were killed and the Cumans continued on to Rob the Russian land.

Svyatoslav of Kiev

Analysis of «the Word about Igor’s regiment», the writing of which was attributed to unknown author, tells of a strange dream of Svyatoslav of Kiev, in which he saw a funeral feast. And his dream came true.

When Svyatoslav learned about the defeat of the Russian troops, he fell into sorrow. Prince Igor was captured. He lived under the supervision of the Polovtsy, but once one of them, Laurel, offered him to escape. This was due to the fact that the Cumans decided to kill all Russian prisoners. Igor agreed to run. Under cover of night, he saddled his horse and secretly drove through the Polovtsian camp.

He made his way to the river Donets eleven days, and Cumans were after him. In the end Igor was able to get to the Russian land. In Kiev and in the Chernigov met him with joy. Ends “Word” the beautiful poetic paraphrase in the address of Prince Igor and his retinue.

Characters «lay»

The Main character of «lay», of course, is Prince Igor Svyatoslavich. This is an outstanding commander, for whom the main thing-to defeat the enemy and to defend the Russian land. Together with his brother and with his victorious army, he is ready on all for the glory of the Motherland.

By the Way, if you look for analysis of «the Word about Igor’s regiment», 9 class, you can find it in the libraries of our schools.

Igor Svyatoslavich makes a mistake due to which his army is defeated, Russian wives remain widows, and children-orphans.

The Kiev Prince Svyatoslav — this is a man who wants peace for Russia, he condemns Igor and his brother Vsevolod for the haste in decision-making and the sadness that they brought to the Russian land. Svyatoslav stands for the Union of the princes, for their performance against the Polovtsians.

The Image of Yaroslavna in the product

Kiev – Igor’s wife – is the Central female character of «lay». If the analysis of «the Word about Igor’s regiment», the lament of Yaroslavna will be the most expressive part in the entire work. Yaroslavna weeps at the highest defense tower of Putivl (this was closer to the Polovtsian steppe). She speaks with the natural elements. The power of her words, they receive inspiration. She blames the wind in that he dispelled the feather of her spree, refers to the Dnieper river and the sun.

Analysis of «the Word about Igor’s regiment», a summary of which you can read in the articles of researchers-linguists, shows that Kiev caused in subsequent generations is much more interesting than the protagonist himself works, and her Crying was translated into many languages. The author of “Words” believes that Crying Yaroslavna has had an impact on the natural force, and therefore Igor Svyatoslavich managed to escape from captivity. The most famous incarnation of the image of Yaroslavna in Opera A. B. Borodin’s «Prince Igor» (written between 1869 and 1887).

Cumans in «lay»

The Main opponents of Prince Igor and the Russian army in the work are Cumans. It is the inhabitants of fields, that is, the endless steppe, the Russian plains

The Relationship of Russian people with the Polovtsy were different, they could be friends, could quarrel. By the 12th century, their relationship becomes hostile. If an analysis of «the Word about Igor’s regiment», the Golden word of Svyatoslav, Igor warns against friendship with the Polovtsy. But his relations with the Polovtsy remain on the whole not so bad. According to historical studies, Igor had a good relationship with the Polovtsian khans Konchak and Abacom. His son even married the daughter of Konchak.

The Cruelty of the Polovtsy, which was emphasized by all subsequent historians, was not greater than was required by the custom of the time. Prince Igor, while in the Polovtsian captivity, could even be practised in the Christian Church. Besides the interaction with the Russian Polovtsy benefit of the Russian people, who are not under the influence of the Catholic Church. In addition, Russian goods were sold at Polovtsian markets, such as in Trebizond and in Derbent.

Historic background of «lay»

Analysis of «the Word about Igor’s regiment» shows that this work was created in the years when Russia was divided into separate parts.

The Value of Kyiv as the center of Russian lands by the time almost disappears. Russian principalities become separate States, and the separation of their lands is fixed at the Council of Liubech in 1097.

The Agreement concluded between the princes at the Convention, have been violated, all the major cities began to strive for independence. But few noticed that Russia needs protection that the enemies are coming from all sides. Rose Cumans and began to fight with the Russian people.

In the middle of the 11th century they already represented a serious threat. «The word about Igor’s regiment», the analysis of which we are trying to spend, is a story about the tragic collision of Russian and Polovtsian.

The Russians could not effectively resist the Polovtsy for the reason that they could not negotiate with them. Constant squabbles weakened the power of the once great Russian state. Yes, at this time in Russia was economic growth, but he was neutralized due to the fact that the relationships between the different farms was weak.

At this time there is a gradual establishment of contacts between the Russian people. Russia is preparing to soon unite into one, but this time too many problematic factors.

The Author of this piece writes not only about military action against Russian Polovtsy. To admire the beauty of the native steppes and forests, the beauty of mother nature. If an analysis of «the Word about Igor’s regiment», the nature of it plays a major role. She helps Prince Igor to escape from captivity and return to the borders of Russia. The wind, the sun and the Dnieper river become his main allies on the way from the Polovtsian Kingdom home.

The Authenticity of «lay»

Almost immediately after the «lay» was published, began to doubt its authenticity. Since the manuscript of this work burned in a fire in 1812, for the analysis and study were only the first printed edition and the manuscript copy.

The Researchers doubted that the product is genuine, for different reasons. The fact that I never found out if…

Слово О Полку Игореве (1187-2012 г.г.):

Воспел баян Русь, струны жили в его руках,

Он пускался, подобно как орёл под облаком,

Воздавая славу князьям и полкам.

На века воспел усобицы, но

В Игоревом полку песни не помнятся —

Не выговорил.

Как на половцев навёл Игорь-князь

Дружину, за землю русскую

Мстить не спросясь решил он.

И вопреки знамени злому — свето-заслону,

Через затмение войско повёл к Дону!

Ждал Игорь Всеволода, брата:

«Готов ли он к бою? Не свернул ли он обратно?»

«С тобой я!», — молвил Всеволод.

«Ведь оба мы Святославичи!

Мои дружины в Курске собраны,

Вскормлены скопия, каждый овраг им известен.

Ищут славы князьям, себе ищут чести.»

И Игорь с сыном Владимиром стали в стремена.

Дорога тьмой была от солнца заслонена.

Ночь грозовая, птиц пробудив,

Стонет свистом зверьевым.

Встрепенулся див, кличит стерево,

И теперь его услышали земли Ханские.

Лукоморье, Сурож и идол Тьму-Тараканский.

За холмом уже русская земля.

Перекрыли русичи щитами поля.

Чуть заря, смяли половецкий отряд,

Красивых девок помчали, по золоту

Полотна, стелить мосты по болотам.

В чужой степи, к Дону на подступи,

Игорево войско спит, лучше б им отступить.

Во всю прыть по Дону волками мчат

Сквозь мрак Хан Кончак и Хан Гзак.

Новый день дал знак кровавыми зорями,

Чёрными тучами с моря,

Грозными дозорами… быть грому великому,

Лить дождю стрелами.

Копья преломить, затупить сабли шлемами.

Топот возрос вскоре,

Шли орды с Дона и с моря,

Криком перекрыв степь в диком хоре.

На реке Каяла русичи стояли в сборе.

Щитами перегородив поле в лютом отпоре.

Буйный Всеволод, бьёшься ты в глуби брани,

Крепче всех булат, куда бы меч ты не направил.

Головы летят, стрелами разишь оравы,

Шлемы рассекаешь, разве страшны тебе раны?!

Забыл о почестях, о престоле наследном по отчеству.

О милой жене, молящейся в одиночестве.

Бой не скоро кончится, воспевал баян

Многие рати, но о таких не слыхал боях:

С утра до утра звенит оружие,

Стрелы пронзают рубахи кольчужные.

Сабли гремят колённые и копья харалужные,

Длится битва, телами покрыта земля под копытами.

Кровью полито, но что трубит там издалека,

Это Игорь завернуть велит своим полкам,

Ибо жаль ему Всеволода, в отваге бились день второй,

К полудню, на третий, пали Игоря стяги.

Не хватило кровавой браги, кончили пир,

Сватов напоили, а сами полегли не допив.

И застонал горем сражённый Чернигов и Киев.

И рыдали жёны, не вернутся их дорогие.

И слетел уже на землю див…

Злой век настал: князья усобицы множат,

Брату брат сказал, это моё, а то моё же.

И крошат великое на малое, себе переча,

И на Русь пошла с победами нечисть.

Игорь, Всеволод, Владимир в плену,

И не было князей, желавших продолжить войну.

Рюрик и Давид, не тонут ваши шлемы в крови,

Так не терпите же обид русской земли.

Галицкий Осмомысл, ты свой престол возвысил,

Дунай и Днепр от тебя зависят,

Стреляешь Салтанов через мысы

И облака, стреляешь князь в Хана

Кощея, Кончака, за Игоревы раны!

Против половецкого зла вступись

Буйный Роман и Стеслав,

Много стран от латинских ваших шлемов

Тряслось, но стяги у князей развиваются врозь.

Чей слышен плачь по утру?

Взлечу над рекой Каяла, рукава

Вымочу и утру князю багряные раны.

На стене, в Путивле взывает Ярославна

К ветру, Ветриле, зачем вихри били?

В лицо и в спину, зачем ты стрелы мчал

На Игореву дружину? И просила Ярославна

Днепра Славутича принести к ней милого, свои струи мча.

Почему в лучах, в поле безводном,

О, владыка солнца, скрутило ты

Жаждою воинов, вдруг волны взвились

По морю полуночному.

Бог указует князю путь к престолу отчему.

Погасли зори, Игорь не спит,

В мысленном взоре беглеца мерит поля от Дона

До малого Донца.

Жеребцам свести Тавлур за рекой,

Через мрак. Князю знак,

Бе

The Word About Igor’s Regiment (1187-2012):

The bayan Rus sang, the strings lived in his hands,

He started up, like an eagle under a cloud,

Praising the princes and regiments.

Intolerance was celebrated for centuries, but

In Igor’s regiment, the songs are not remembered —

I did not utter it.

How the Prince of Polovtsy was led by Igor the Prince

Druzhin, for the Russian land

He decided not to ask for revenge.

And despite the evil banner — the light barrier,

Through the eclipse the army led to the Don!

I was waiting for Igor Vsevolod, my brother:

«Is he ready for battle?» Did he turn it back? & Quot;

«With you I!», — said Vsevolod.

Both are Svyatoslavich!

My squads in Kursk are collected,

Scopies are sowed, each ravine is known to them.

They seek glory for the princes, they seek honor for themselves. «

And Igor and his son Vladimir were in the stirrups.

The road was darkened from the sun by the darkness.

The night was stormy,

It’s moaning like a whistling beast.

The div drew up,

And now he heard the lands of Khansky.

Lukomorye, Surozh and the idol of Dark-Tarakansky.

The hill is already Russian land.

We blocked the Rusichi with the shields of the field.

A little dawn, the Polovtsian detachment was crushed,

Beautiful girls were dying, on gold

Cloths, lay bridges in the marshes.

In a strange steppe, towards the Don,

Igor’s army is asleep, it would be better for them to retreat.

In all the way through the Don wolves weep

Through the darkness Khan Konchak and Khan Gzak.

A new day gave a sign of bloody dawns,

Black clouds from the sea,

Terrible patrols … be a great thunder,

Pour rain arrows.

Spears break, blunt sabers with helmets.

Topot grew soon,

There were hordes from the Don and from the sea,

Shouting off the steppe in the wild chorus.

On the river Kayala, the Rusichi were assembled.

Shields defeated the field in a fierce rebuff.

Violent Vsevolod, you fight in the depths of battle,

Stronger than all the damask, wherever the sword you sent.

Heads fly, you shoot open the arrows,

Helmets are dissecting, are your wounds terrible?

I forgot about honors, about the hereditary throne by patronymic.

About a sweet wife praying alone.

The battle will not end soon, the accordion was singing

Many rati, but about such did not hear battles:

From morning till morning, it rings with weapons,

Arrows pierce shirt mail.

The sabers rattled the kolonnye and the lances of the haraluzhnye,

The battle lasts, the bodies are covered with earth under hoofs.

The blood is poured, but that blows there from afar,

This Igor wraps his regiments,

For Vsevolod feels sorry for him, the day was fought in courage,

By noon, on the third, Igor’s banners fell.

There was not enough bloody brag, ended the feast,

They sued the matchmakers, but they did not finish themselves.

And the grieved Chernigov and Kiev groaned with grief.

And their wives sobbed, their dear ones will not return.

And he was already flying to the ground …

The evil age has come: the princes of the strife are multiplying,

My brother said to my brother, this is mine, and then mine.

And they crumble the great into the small, to themselves,

And the evil spirits went to Russia with victories.

Igor, Vsevolod, Vladimir in captivity,

And there were no princes who wanted to continue the war.

Rurik and David, do not drown your helmets in the blood,

So do not tolerate the grievances of the Russian land.

Galitsky Osmomysl, you elevated your throne,

The Danube and the Dnieper depend on you,

Shoot Saltanov through capes

And the clouds, shoot the prince in Khan

Koshchei, Konchak, for Igor’s wounds!

Against Polovtsian evil enter

Rampant Roman and Steslav,

Many countries from your Latin helmets

It was shaking, but the banners of the princes developed separately.

Do you hear cry in the morning?

I will take off the river Kayala, the sleeves

I’ll wet and crimson wounds in the morning.

On the wall, in Putivl, Yaroslavna

To the wind, to Vetril, why did the whirlwinds beat?

In the face and in the back, why did you shoot the arrows

At Igorev’s squad? And she asked Yaroslavna

Dnieper Slavutich to bring her dear, her streams of moss.

Why in the rays, in the field of anhydrous,

Oh, lord of the sun, you twisted

Thirsty warriors, suddenly the waves flew up

By the midnight sea.

God points the prince’s way to the throne of the father.

Outside the dawn, Igor does not sleep,

In the mind’s eye, the fugitive is measuring the fields from the Don

To the small Donets.

To stallions to bring Tavlur across the river,

Through the darkness. I congratulate the prince,

Be

From our present, where everything is systematized, with the uninterrupted operation of vehicles and the availability of Internet communication with the whole world, the ancient book «The Lay of Igor’s Campaign» seems like a fairy tale. We are used to the fact that the issues are being resolved at the negotiating table, but it was the same before.

«The Lay of Igor’s Host» in details and details

If you want to really learn about the realities of old years, for example, how everything was in Russia more than one thousand years ago — we recommend to visit a unique museum-preserve, which is located in Novgorod-Seversky Chernigov region, Ukraine. On the right bank of the Desna, in the north-eastern direction from Kiev, for 270 kilometers arranged a museum, which is called «The Lay of Igor’s Campaign.» This place, without exaggeration, can be considered a true «heart» of the birth of the mighty Kievan Rus.

Novgorod-Seversky emerged at the turn of the millennium, in 989. Interesting facts indicate that by the middle of the 11th century a full-fledged social infrastructure was functioning here — there was a prince’s court, temples, good houses of warriors, traders and artisans were built. The economic base of the ancient city was, first of all, handicrafts, trade activities, cultivation of lands, as well as livestock breeding, hunting and fishing.

The museum-reserve was opened in 1990 on the vast territory of the Transfiguration Monastery, founded in the far 1033 by Prince Mstislav Vladimirovich the Brave (Tmutarakansky). At that time, the peace with its neighbors was unsteady and the monastery performed many functions, from the defense of the terrain from enemy raids to spiritual enlightenment and the instruction of the laity. Restoration work in the operating monastery ended in 2003, and to this day, here come the believers and tourists from all over the world to fill this holiness and find peace of mind.

How to get to the museum-reserve in Novgorod-Seversky

Travel to Chernigov will be for every tourist a real pleasure, regardless of the season. Each time of the year here in its own way is beautiful and unique. You can enter the territory of the Savior-Transfiguration Monastery any day, without restrictions. From the railway station or bus station you will quickly get to the territory of the monastery, and there you already have to decide where you want to visit the ancient structures, exhibitions and expositions.

Просмотров:

624

Skip to content

The story of Igor’s Regiment is based on the description of the unsuccessful campaign of Russian soldiers led by Prince Igor Svyatoslavich against the Polovtsian invaders. This heroic epic, called the first Russian tragedy, glorified not victory, but defeat. The author of the poem is unknown, but there is a version that this is a monk who witnessed Igor’s campaign. Prince Igor’s speech is shown against the general gigantic background of the history of all Russia. «The Word about Igor’s Regiment» can be rightfully called a monument of Russian culture. It confirms that the Russian folk epic is a branch of European culture.

Prince Igor set out on his famous campaign in 1185. Most of the sources believe that the «Word» was written in the same year. However, there are opinions that this work was created a little later. The epic «The Lay of Igor’s Campaign» concerns both the problems of all of Russia as a whole, and the miscalculations of a particular Igor’s campaign. This work explains to readers what is the main reason for the failure of the Russian prince. According to the author, this is Igor’s excessive ambition, his excessive pride and arrogance.

In the second chapter of the poem, the problem of the disunity of Russia is most clearly shown. Through the «golden word» spoken by Svyatoslav, the author tries to explain to the readers the idea that Russia can become invincible only in one case – if there is general unity. Only general ideas and the unification of all forces will make Russia great and formidable. Otherwise, with the existing general fragmentation, it will remain weak and defenseless.

The meaning of The Lay of Igor’s Host is important in the modern world as well. It calls for taking into account the mistakes made in the past and not repeating them in the future.

|

«Слово о полку Игореве» — произведение, проливающее нам свет на древне русскую культуру и события древней Руси. «Слово о полку Игореве» описывает неудачный поход на половцев новгород-северского князя Игоря Святославича в союзе с Всеволодом, Владимиром и Святославом Ольговичем (1185 г.). Все началось с того, что Алексей Иванович Мусин-Пушкин (1744-1817) увлекся собиранием древностей. Его коллекция понравилась императрице Екатерине Великой, и она назначила графа обер-прокурором Синода. Следующим своим указом она повелела собирать в Синоде древние рукописи и старопечатные книги из всех церквей и монастырей России. Мусин-Пушкин готовил к печати древние рукописи и в 1800 году дошла очередь и до «Слова», которое нужно было перевести с древнерусского языка на язык, на котором говорили в XVIII веке. Мусин-Пушкин сразу понял — поэма уникальна. Она перечеркивала распространенное тогда мнение о том, что у русских раньше не было светской литературы. Нужно было осмыслить и описанные в «Слове» очень важные для истории события. Современники Мусина-Пушкина не поняли, какое сокровище стало достоянием русской культуры. Сразу же начали распространяться слухи о том, что это подделка. Первым, кто резко выступил против слухов, стал Александр Сергеевич Пушкин. Великий поэт сказал, что, во-первых, для того, чтобы подделать поэму XII века нужно не только умение читать, но и свободно писать на древнерусском языке. Во-вторых, нужно знать имена древних богов и князей. В-третьих, необходимо обладать немалым литературным даром. Если бы такой человек жил в России в конце XVIII — начале XIX века, то имя этого историка и поэта было бы известно всем. А такого человека в те времена не было, то и «Слово о полку Игореве» никому подделать было не под силу. «Слово о полку Игореве» переводили много раз. Среди переводчиков были наши выдающиеся поэты Василий Андреевич Жуковский, Аполлон Николаевич Майков и Николай Алексеевич Заболоцкий. Древнерусский текст «Слова» разбит на абзацы и ритмические единицы. Этой разбивки в подлинной рукописи «Слова» не было, т.к. в русских рукописях XI-XVII веков текст (в том числе и поэтический) писался в сплошную строку. Поход князя Игоря против половцев изображали на своих полотнах великие художники: Виктор Михайлович Васнецов, Василий Григорьевич Перов, Владимир Андреевич Фаворский. Композитор Александр Порфирьевич Бородин начал работу над оперой «Князь Игорь», которую из-за кончины композитора завершили два других выдающихся русских композитора Николай Андреевич Римский-Корсаков и Александр Константинович Глазунов. Это музыкальное произведение стало образцом национального героического эпоса в оперном искусстве. Смотрите также:

Все тексты Слово о полку Игореве >>> |

The Lay of Igor’s Host is a work that sheds light on ancient Russian culture and events in ancient Russia.

«The Lay of Igor’s Regiment» describes an unsuccessful campaign against the Polovtsians of the Novgorod-Seversk prince Igor Svyatoslavich in alliance with Vsevolod, Vladimir and Svyatoslav Olgovich (1185).

By the time of writing, «The Word» is attributed to the year 1187-1188.

It all started with the fact that Alexei Ivanovich Musin-Pushkin (1744-1817) became interested in collecting antiquities. Empress Catherine the Great liked his collection, and she appointed the count as chief prosecutor of the Synod.

By her next decree, she ordered to collect in the Synod ancient manuscripts and early printed books from all the churches and monasteries of Russia.

Musin-Pushkin prepared ancient manuscripts for printing, and in 1800 the turn came to the Lay, which needed to be translated from the Old Russian language into the language spoken in the 18th century. Musin-Pushkin immediately understood that the poem was unique. She crossed out the then widespread opinion that Russians had no secular literature before. It was also necessary to comprehend the events described in the Lay, which are very important for history.

Musin-Pushkin’s contemporaries did not understand what treasure became the property of Russian culture. Immediately, rumors began to spread that it was a fake. The first to sharply oppose the rumors was Alexander Sergeevich Pushkin. The great poet said that, firstly, in order to forge a 12th century poem, one needs not only the ability to read, but also write fluently in the Old Russian language. Secondly, you need to know the names of the ancient gods and princes. Third, it is necessary to have a considerable literary gift. If such a person lived in Russia in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, then the name of this historian and poet would be known to everyone. And there was no such person in those days, then “The Lay of Igor’s Campaign” could not be forged by anyone.

«The Word about Igor’s Regiment» was translated many times. Among the translators were our outstanding poets Vasily Andreevich Zhukovsky, Apollon Nikolaevich Maikov and Nikolai Alekseevich Zabolotsky.

The Old Russian text of the Lay is divided into paragraphs and rhythmic units. There was no such breakdown in the original manuscript of the Lay, since in Russian manuscripts of the XI-XVII centuries, the text (including poetry) was written in a continuous line.

The campaign of Prince Igor against the Polovtsy was depicted on their canvases by great artists: Viktor Mikhailovich Vasnetsov, Vasily Grigorievich Perov, Vladimir Andreevich Favorsky. Composer Alexander Porfirevich Borodin began work on the opera «Prince Igor», which, due to the death of the composer, was completed by two other outstanding Russian composers Nikolai Andreevich Rimsky-Korsakov and Alexander Konstantinovich Glazunov. This piece of music has become a model of the national heroic epic in the art of opera.