A corporal punishment or a physical punishment is a punishment which is intended to cause physical pain to a person. When it is inflicted on minors, especially in home and school settings, its methods may include spanking or paddling. When it is inflicted on adults, it may be inflicted on prisoners and slaves.

Physical punishments for crimes or injuries, including floggings, brandings and even mutilations, were practised in most civilizations since ancient times. With the growth of humanitarian ideals since the Enlightenment, such punishments are increasingly viewed as inhumane in the Western society. By the late 20th century, corporal punishment had been eliminated from the legal systems of most developed countries.[1]

In the twenty-first century, the legality of corporal punishment in various settings differs by jurisdiction. Internationally, the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries saw the application of human rights law to the question of corporal punishment in a number of contexts:

- Corporal punishment in the home, the punishment of children by parents or other adult guardians, is legal in most of the world. As of 2021, 63 countries, mostly in Europe and Latin America, have banned the practice.[2]

- School corporal punishment, of students by teachers or school administrators, such as caning or paddling, has been banned in many countries, including Canada, Kenya, South Africa, India, New Zealand and all of Europe. It remains legal, if increasingly less common, in some states of the United States and in some countries in Africa and Southeast Asia.

- Judicial corporal punishment, such as whipping or caning, as part of a criminal sentence ordered by a court of law, has long disappeared from most European countries.[3] As of 2021, it remains lawful in parts of Africa, Asia the Anglophone Caribbean and indigenous communities in several countries of South America.[3]

- Prison corporal punishment or disciplinary corporal punishment, ordered by prison authorities or carried out directly by correctional officers against the inmates for misconduct in custody, has long been common practice in penal institutions worldwide. It has officially been banned in most Western civilizations during the 20th century, but is still employed in many other countries today. Punishments such as paddling, foot whipping or different forms of flagellation have been commonplace methods of corporal punishment within prisons. This was also common practice in the Australian penal colonies and prison camps of the Nazi regime in Germany.

- Military corporal punishment is or was allowed in some settings in a few jurisdictions.

In many Western countries, medical and human rights organizations oppose the corporal punishment of children. Campaigns against corporal punishment have aimed to bring about legal reforms in order to ban the use of corporal punishment against minors in homes and schools.

HistoryEdit

PrehistoryEdit

Author Jared Diamond writes that hunter-gatherer societies have tended to use little corporal punishment whereas agricultural and industrial societies tend to use progressively more of it. Diamond suggests this may be because hunter-gatherers tend to have few valuable physical possessions, and misbehavior of the child would not cause harm to others’ property.[4]

Researchers who have lived among the Parakanã and Ju/’hoansi people, as well as some Aboriginal Australians, have written about the absence of the physical punishment of children in those cultures.[5]

Wilson writes:

Probably the only generalization that can be made about the use of physical punishment among primitive tribes is that there was no common procedure […] Pettit concludes that among primitive societies corporal punishment is rare, not because of the innate kindliness of these people but because it is contrary to developing the type of individual personality they set up as their ideal […] An important point to be made here is that we cannot state that physical punishment as a motivational or corrective device is ‘innate’ to man.[6]

AntiquityEdit

Birching, Germany, 17th century

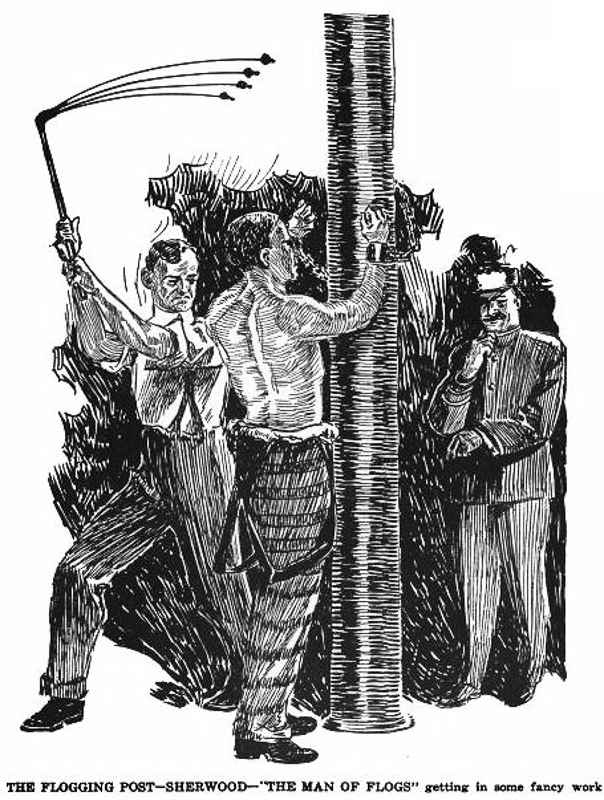

Depiction of a flogging at Oregon State Penitentiary, 1908

In the Western world, the corporal punishment of children has traditionally been used by adults in authority roles.[7] Beating one’s child as a form of punishment is even recommended in the book of Proverbs:

He that spareth the rod, hateth his son; but he that loveth him, chasteneth him betimes. (Proverbs 13:24)

A fool’s lips enter into contention, and his mouth calleth for strokes. (Proverbs 18:6)

Chasten thy son while there is hope, and let not thy soul spare for his crying. (Proverbs 19:18)

Foolishness is bound in the heart of a child; but the rod of correction shall drive it from him. (Proverbs 22:15)

Withhold not correction from the child; for if thou beatest him with a rod, thou shalt deliver his soul from hell. (Proverbs 23:13–14)[8]

Robert McCole Wilson argues that, «Probably this attitude comes, at least in part, from the desire in the patriarchal society for the elder to maintain his authority, where that authority was the main agent for social stability. But these are the words that not only justified the use of physical punishment on children for over a thousand years in Christian communities, but ordered it to be used. The words were accepted with but few exceptions; it is only in the last two hundred years that there has been a growing body of opinion that differed. Curiously, the gentleness of Christ towards children (Mark, X) was usually ignored».[9]

Corporal punishment was practiced in Egypt, China, Greece, and Rome in order to maintain judicial and educational discipline.[10] Disfigured Egyptian criminals were exiled to Tjaru and Rhinocorura on the Sinai border, a region whose name meant «cut-off noses.» Corporal punishment was prescribed in ancient Israel, but it was limited to 40 lashes.[11] In China, some criminals were also disfigured but other criminals were tattooed. Some states gained a reputation for their cruel use of such punishments; Sparta, in particular, used them as part of a disciplinary regime which was designed to increase willpower and physical strength.[12] Although the Spartan example was extreme, corporal punishment was possibly the most frequent type of punishment. In the Roman Empire, the maximum penalty which a Roman citizen could receive under the law was 40 «lashes» or 40 «strokes» with a whip which was applied to the back and shoulders, or 40 lashes or strokes with the «fasces» (similar to a birch rod, but consisting of 8–10 lengths of willow rather than birch) which were applied to the buttocks. Such punishments could draw blood, and they were frequently inflicted in public.

Quintilian (c. 35 – c. 100) voiced some opposition to the use of corporal punishment. According to Wilson, «probably no more lucid indictment of it has been made in the succeeding two thousand years».[12]

By that boys should suffer corporal punishment, though it is received by custom, and Chrysippus makes no objection to it, I by no means approve; first, because it is a disgrace, and a punishment fit for slaves, and in reality (as will be evident if you imagine the age change) an affront; secondly, because, if a boy’s disposition be so abject as not to be amended by reproof, he will be hardened, like the worst of slaves, even to stripes; and lastly, because, if one who regularly exacts his tasks be with him, there will not be the need of any chastisement (Quintilian, Institutes of Oratory, 1856 edition, I, III).[12]

Plutarch, also in the first century, writes:

This also I assert, that children ought to be led to honourable practices by means of encouragement and reasoning, and most certainly not by blows or ill-treatment, for it surely is agreed that these are fitting rather for slaves than for the free-born; for so they grow numb and shudder at their tasks, partly from the pain of the blows, partly from the degradation.[13]

Middle AgesEdit

In Medieval Europe, the Byzantine Empire blinded and denosed some criminals and rival emperors. Their belief that the emperor should be physically ideal meant that such disfigurement notionally disqualified the recipient from office. (The second reign of Justinian the Slit-nosed was the notable exception.) Elsewhere, corporal punishment was encouraged by the attitudes of the Catholic church towards the human body, flagellation being a common means of self-discipline. This had an influence on the use of corporal punishment in schools, as educational establishments were closely attached to the church during this period. Nevertheless, corporal punishment was not used uncritically; as early as the 11th century Saint Anselm, Archbishop of Canterbury was speaking out against what he saw as the excessive use of corporal punishment in the treatment of children.[14]

ModernityEdit

From the 16th century onwards, new trends were seen in corporal punishment. Judicial punishments were increasingly turned into public spectacles, with public beatings of criminals intended as a deterrent to other would-be offenders. Meanwhile, early writers on education, such as Roger Ascham, complained of the arbitrary manner in which children were punished.[15]

Peter Newell writes that perhaps the most influential writer on the subject was the English philosopher John Locke, whose Some Thoughts Concerning Education explicitly criticised the central role of corporal punishment in education. Locke’s work was highly influential, and may have helped influence Polish legislators to ban corporal punishment from Poland’s schools in 1783, the first country in the world to do so.[16]

Corporal punishment in a women’s prison in the United States (ca. 1890)

Batog, corporal punishment in the Russian Empire

Husaga (the right of the master of the household to corporally punish his servants) was outlawed in Sweden for adults in 1858.

A consequence of this mode of thinking was a reduction in the use of corporal punishment in the 19th century in Europe and North America. In some countries this was encouraged by scandals involving individuals seriously hurt during acts of corporal punishment. For instance, in Britain, popular opposition to punishment was encouraged by two significant cases, the death of Private Frederick John White, who died after a military flogging in 1846,[17] and the death of Reginald Cancellor, killed by his schoolmaster in 1860.[18] Events such as these mobilised public opinion and, by the late nineteenth century, the extent of corporal punishment’s use in state schools was unpopular with many parents in England.[19] Authorities in Britain and some other countries introduced more detailed rules for the infliction of corporal punishment in government institutions such as schools, prisons and reformatories. By the First World War, parents’ complaints about disciplinary excesses in England had died down, and corporal punishment was established as an expected form of school discipline.[19]

In the 1870s, courts in the United States overruled the common-law principle that a husband had the right to «physically chastise an errant wife».[20] In the UK, the traditional right of a husband to inflict moderate corporal punishment on his wife in order to keep her «within the bounds of duty» was similarly removed in 1891.[21][22] See Domestic violence for more information.

In the United Kingdom, the use of judicial corporal punishment declined during the first half of the twentieth century and it was abolished altogether in the Criminal Justice Act, 1948 (zi & z2 GEo. 6. CH. 58.), whereby whipping and flogging were outlawed except for use in very serious internal prison discipline cases,[23] while most other European countries had abolished it earlier. Meanwhile, in many schools, the use of the cane, paddle or tawse remained commonplace in the UK and the United States until the 1980s. In rural areas of the Southern United States, and in several other countries, it still is: see School corporal punishment.

International treatiesEdit

Human rightsEdit

Key developments related to corporal punishment occurred in the late 20th century. Years with particular significance to the prohibition of corporal punishment are emphasised.

- 1950: European Convention of Human Rights, Council of Europe.[24] Article 3 bans «inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment».

- 1978: European Court of Human Rights, overseeing its implementation, rules that judicial birching of a juvenile breaches Article 3.[25]

- 1985: Standard Minimum Rules for the Administration of Juvenile Justice, or Beijing Rules, United Nations (UN). Rule 17.3: «Juveniles shall not be subject to corporal punishment.»

- 1990 Supplement: Rules for the Protection of Juveniles Deprived of their Liberty. Rule 67: «…all disciplinary measures constituting cruel, inhumane or degrading treatment shall be strictly prohibited, including corporal punishment…»

- 1990: Guidelines for the Prevention of Juvenile Delinquency, the Riyadh Guidelines, UN. Paragraph 21(h): education systems should avoid «harsh disciplinary measures, particularly corporal punishment.»

- 1966: International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, UN, with currently 167 parties, 74 signatories.[26] Article 7: «No one shall be subjected to torture or to cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment…»

- 1992: Human Rights Committee, overseeing its implementation, comments: «the prohibition must extend to corporal punishment . . . in this regard . . . article 7 protects, in particular, children, . . ..»[27]

- 1984: Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment, UN, with currently 150 parties and 78 signatories.[28]

- 1996: Committee Against Torture, overseeing its implementation, condemns corporal punishment.[29]

- 1966: International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, UN, with currently 160 parties, and 70 signatories.[30] Article 13(1): «education shall be directed to the full development of the human personality and the sense of its dignity…»

- 1999: Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, overseeing its implementation, comments: «corporal punishment is inconsistent with the fundamental guiding principle of international human rights law . . . the dignity of the individual.»[31]

- 1961: European Social Charter, Council of Europe.

- 2001: European Committee of Social Rights, overseeing its implementation, concludes: it is not «acceptable that a society which prohibits any form of physical violence between adults would accept that adults subject children to physical violence.»[32]

Children’s rightsEdit

The notion of children’s rights in the Western world developed in the 20th century, but the issue of corporal punishment was not addressed generally before mid-century. Years with particular significance to the prohibition of corporal punishment of children are emphasised.

- 1923: Children’s Rights Proclamation by Save the Children founder. (5 articles).

- 1924 Adopted as the World Child Welfare Charter, League of Nations (non-enforceable).

- 1959: Declaration of the Rights of the Child, (UN) (10 articles; non-binding).

- 1989: Convention on the Rights of the Child, UN (54 articles; binding treaty), with currently 193 parties and 140 signatories.[33] Article 19.1: «States Parties shall take all appropriate legislative, administrative, social and educational measures to protect the child from all forms of physical or mental violence, injury or abuse, neglect or negligent treatment, maltreatment or exploitation . . . .»

- 2006: Committee on the Rights of the Child, overseeing its implementation, comments: there is an «obligation of all States Party to move quickly to prohibit and eliminate all corporal punishment.»[34]

- 2011: Optional Protocol on a Communications Procedure allowing individual children to submit complaints regarding specific violations of their rights.[35]

- 2006: Study on Violence against Children presented by Independent Expert for the Secretary-General to the UN General Assembly.[36]

- 2007: Post of Special Representative of the Secretary-General on violence against children established.[37]

Modern useEdit

Laws on corporal punishments in the world

Prohibited altogether

Prohibited in schools

Not prohibited in schools nor in a home, but prohibited in at least one setting

Not prohibited at any setting

Depends on state (USA)

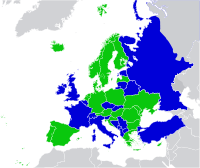

Legality of corporal punishment of minors in Europe

Corporal punishment banned altogether

Corporal punishment banned in schools only

Corporal punishment not prohibited in schools or in the home

Legal statusEdit

66 countries, most of them in Europe and Latin America, have prohibited any corporal punishment of children.

The earliest recorded attempt to prohibit corporal punishment of children by a state dates back to Poland in 1783.[38]: 31–2 However, its prohibition in all spheres of life – in homes, schools, the penal system and alternative care settings – occurred first in 1966 in Sweden. The 1979 Swedish Parental Code reads: «Children are entitled to care, security and a good upbringing. Children are to be treated with respect for their person and individuality and may not be subjected to corporal punishment or any other humiliating treatment.»[38]: 32

As of 2021, corporal punishment of children by parents (or other adults) is outlawed altogether in 63 nations (including the partially recognized Republic of Kosovo) and 3 constituent nations.[2]

| Country | Year |

|---|---|

| Sweden | 1979 |

| Finland | 1983 |

| Norway | 1987 |

| Austria | 1989 |

| Cyprus | 1994 |

| Denmark | 1997 |

| Poland | 1997 |

| Latvia | 1998 |

| Germany | 1998 |

| Croatia | 1999 |

| Bulgaria | 2000 |

| Israel | 2000 |

| Turkmenistan | 2002 |

| Iceland | 2003 |

| Ukraine | 2004 |

| Romania | 2004 |

| Hungary | 2005 |

| Greece | 2006 |

| New Zealand | 2007 |

| Netherlands | 2007 |

| Portugal | 2007 |

| Uruguay | 2007 |

| Venezuela | 2007 |

| Spain | 2007 |

| Togo | 2007 |

| Costa Rica | 2008 |

| Moldova | 2008 |

| Luxembourg | 2008 |

| Liechtenstein | 2008 |

| India | 2009 |

| Tunisia | 2010 |

| Kenya | 2010 |

| Congo, Republic of | 2010 |

| Albania | 2010 |

| South Sudan | 2011 |

| North Macedonia | 2013 |

| Cabo Verde | 2013 |

| Honduras | 2013 |

| Malta | 2014 |

| Brazil | 2014 |

| Bolivia | 2014 |

| Argentina | 2014 |

| San Marino | 2014 |

| Nicaragua | 2014 |

| Estonia | 2014 |

| Andorra | 2014 |

| Benin | 2015 |

| Ireland | 2015 |

| Peru | 2015 |

| Mongolia | 2016 |

| Montenegro | 2016 |

| Paraguay | 2016 |

| Aruba | 2016[39] |

| Slovenia | 2016 |

| Lithuania | 2017 |

| Nepal | 2018 |

| Kosovo | 2019 |

| France | 2019 |

| South Africa | 2019 |

| Jersey | 2019 |

| Georgia | 2020 |

| Japan | 2020 |

| Seychelles | 2020 |

| Scotland | 2020 |

| Guinea | 2021 |

| Colombia | 2021 |

| South Korea | 2021 |

| Wales | 2022 |

| Zambia | 2022 |

For a more detailed overview of the global use and prohibition of the corporal punishment of children, see the following table.

| Home | Schools | Penal system | Alternative care settings | ||

| As sentence for crime | As disciplinary measure | ||||

| Prohibited | 67 | 130 | 156 | 117 | 39 |

| Not prohibited | 131 | 68 | 41 | 77 | 159 |

| Legality unknown | – | – | 1 | 4 | – |

Corporal punishment in the homeEdit

Domestic corporal punishment (i.e. the punishment of children by their parents) is often referred to colloquially as «spanking», «smacking», or «slapping».

It has been outlawed in an increasing number of countries, starting with Sweden in 1979.[40][2] In some other countries, corporal punishment is legal, but restricted (e.g. blows to the head are outlawed, implements may not be used, only children within a certain age range may be spanked).

In all states of the United States and most African and Asian nations, corporal punishment by parents is legal. It is also legal to use certain implements (e.g. a belt or a paddle).

In Canada, spanking by parents or legal guardians (but nobody else) is legal, with certain restrictions: the child must be between the ages of 2–12, and no implement other than an open, bare hand may be used (belts, paddles, etc. are prohibited). It is also illegal to strike the head when disciplining a child.[41][42]

In the UK (except Scotland and Wales), spanking or smacking is legal, but it must not cause an injury amounting to actual bodily harm (any injury such as visible bruising, breaking of the whole skin, etc.). In addition, in Scotland, since October 2003, it has been illegal to use any implements or to strike the head when disciplining a child, and it is also prohibited to use corporal punishment towards children under the age of 3 years. In 2019, Scotland enacted a ban on corporal punishment, which went into effect in 2020. Wales also enacted a ban in 2020, which has gone into effect in 2022.[43]

In Pakistan, Section 89 of Pakistan Penal Code allows corporal punishment.[44]

Corporal punishment in schoolsEdit

Corporal punishment in schools has been outlawed in many countries. It often involves striking the student on the buttocks or the palm of the hand with an implement (e.g. a rattan cane or a spanking paddle).

In countries where corporal punishment is still allowed in schools, there may be restrictions; for example, school caning in Singapore and Malaysia is, in theory, permitted for boys only.

In India and many other countries, corporal punishment has technically been abolished by law. However, corporal punishment continues to be practiced on boys and girls in many schools around the world. Cultural perceptions of corporal punishment have rarely been studied and researched. One study carried out discusses how corporal punishment is perceived among parents and students in India.[45]

Medical professionals have urged putting an end to the practice, noting the danger of injury to children’s hands especially.[46]

Judicial or quasi-judicial punishmentEdit

Countries with judicial corporal punishment

Around 33 countries in the world still retain judicial corporal punishment, including a number of former British territories such as Botswana, Malaysia, Singapore and Tanzania. In Singapore, for certain specified offences, males are routinely sentenced to caning in addition to a prison term. The Singaporean practice of caning became much discussed around the world in 1994 when American teenager Michael P. Fay received four strokes of the cane for vandalism. Judicial caning and whipping are also used in Aceh Province in Indonesia.[47]

A number of other countries with an Islamic legal system, such as Saudi Arabia, UAE, Qatar, Iran, Brunei, Sudan, and some northern states in Nigeria, employ judicial whipping for a range of offences. In April 2020, the Saudi Supreme Court ended the flogging punishment from its court system, and replaced it with jail time or fines.[48] As of 2009, some regions of Pakistan are experiencing a breakdown of law and government, leading to a reintroduction of corporal punishment by ad hoc Islamicist courts.[49] As well as corporal punishment, some Islamic countries such as Saudi Arabia and Iran use other kinds of physical penalties such as amputation or mutilation.[50][51][52] However, the term «corporal punishment» has since the 19th century usually meant caning, flagellation or bastinado rather than those other types of physical penalty.[53][54][55][56][57][58][59]

In some countries, foot whipping (bastinado) is still practiced on prisoners.[60]

RitualsEdit

In parts of England, boys were once beaten under the old tradition of «Beating the Bounds» whereby a boy was paraded around the edge of a city or parish and spanked with a switch or cane to mark the boundary.[61] One famous «Beating the Bounds» took place around the boundary of St Giles and the area where Tottenham Court Road now stands in central London. The actual stone that marked the boundary is now underneath the Centre Point office tower.[62]

In the Czech Republic, Slovakia, and some parts of Hungary, a tradition for health and fertility is carried out on Easter Monday. Boys and young men will spank or whip girls and young women on the bottom with braided willow branches. After the man sings the verse, the young woman turns around and the man takes a few whacks at her backside with the whip. [63][64]

In popular cultureEdit

The Flagellation, by Piero della Francesca

Art

- The Flagellation, (c.1455–70), by Piero della Francesca. Christ is lashed while Pontius Pilate looks on.

- The Whipping, (1941), by Horace Pippin. A figure tied to a whipping post is flogged.[65]

Film and TV

See: List of films and TV containing corporal punishment scenes.

See alsoEdit

- Campaigns against corporal punishment

- Chastisement

- Child discipline

- Disfigurement

- Hotsaucing

- Physical abuse

- School violence

- Tough love

- Virge

- Washing out mouth with soap

ReferencesEdit

- ^ «Corporal punishment». Encyclopædia Britannica. 9 November 2014.

- ^ a b c d e «States which have prohibited all corporal punishment». www.endcorporalpunishment.org. Global Initiative to End All Corporal Punishment of Children.

- ^ a b «Progress». Global Partnership to End Violence Against Children. 2021.

- ^ Diamond, Jared (2013). The World Until Yesterday. Viking. Ch. 5. ISBN 978-1-101-60600-1.

- ^ Gray, Peter (2009). «Play as a Foundation for Hunter-Gatherer Social Existence». American Journal of Play. 1 (4): 476–522.

- ^ Wilson (1971), 2.1.

- ^ Rich, John M. (December 1989). «The Use of Corporal Punishment». The Clearing House, Vol. 63, No. 4, pp. 149–152.

- ^ Wilson, Robert M. (1971). A Study of Attitudes Towards Corporal Punishment as an Educational Procedure From the Earliest Times to the Present (Thesis). University of Victoria. 2.3. OCLC 15767752.

- ^ Wilson (1971), 2.3.

- ^ Wilson (1971), 2.3–2.6.

- ^ Deuteronomy 25:1-3

- ^ a b c Wilson (1971), 2.5.

- ^ Plutarch, Moralia. The Education of Children, Loeb Classical Library. Harvard University Press, 1927.

- ^ Wicksteed, Joseph H. The Challenge of Childhood: An Essay on Nature and Education, Chapman & Hall, London, 1936, pp. 34–35. OCLC 3085780

- ^ Ascham, Roger. The scholemaster, John Daye, London, 1571, p. 1. Republished by Constable, London, 1927. OCLC 10463182

- ^ Newell, Peter (ed.). A Last Resort? Corporal Punishment in Schools, Penguin, London, 1972, p. 9 ISBN 0140806989

- ^ Barretts, C.R.B. The History of The 7th Queen’s Own Hussars Vol. II Archived 3 October 2011 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Middleton, Jacob (2005). «Thomas Hopley and mid-Victorian attitudes to corporal punishment». History of Education.

- ^ a b Middleton, Jacob (November 2012). «Spare the Rod». History Today (London).

- ^ Calvert, R. «Criminal and civil liability in husband-wife assaults», in Violence in the family (Suzanne K. Steinmetz and Murray A. Straus, eds.), Harper & Row, New York, 1974. ISBN 0-396-06864-2

- ^ R. v Jackson Archived 7 September 2014 at the Wayback Machine, [1891] 1 QB 671, abstracted at LawTeacher.net.

- ^ Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). «Corporal Punishment» . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 7 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 189–190.

- ^ Criminal Justice Act, 1948 zi & z2 GEo. 6. CH. 58., pp. 54–55.

- ^ This applies to the 47 members of the Council of Europe, an entirely separate body from the European Union, which has only 28 member states.

- ^ Global Initiative to End All Corporal Punishment of Children (2012). Retrieved 1 May 2012. «Key Judgements.» The ruling concerned the Isle of Man, a UK Crown Dependency.

- ^ UN (2012) «4 . International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights Archived 1 September 2010 at the Wayback Machine,» United Nations Treaty Collection. Retrieved 1 May 2012.

- ^ UN Human Rights Committee (1992) «General Comment No. 20». HRI/GEN/1/Rev.4.: p. 108

- ^ UN (2012) «9 . Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment Archived 8 November 2010 at the Wayback Machine. United Nations Treaty Collection. Retrieved 1 May 2012.

- ^ UN (1996) General Assembly Official Records, Fiftieth Session, A/50/44, 1995: par. 177, and A/51/44, 1996: par. 65(i).

- ^ UN (2012). 3. International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights. Archived 17 September 2012 at the Wayback Machine United Nations Treaty Collection. Retrieved 1 May 2012.

- ^ UN Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (1999) «General Comment on ‘The Right to Education’,» HRI/GEN/1/Rev.4: 73.

- ^ European Committee of Social Rights 2001. «Conclusions XV – 2,» Vol. 1.

- ^ UN (2012). 11. Convention on the Rights of the Child Archived 11 February 2014 at the Wayback Machine. United Nations Treaty Collection. Retrieved 1 May 2012.

- ^ UN Committee on the Rights of the Child (2006) «General Comment No. 8:» par. 3. However, Article 19 of the Convention makes no reference to corporal punishment, and the Committee’s interpretation on this point has been explicitly rejected by several States Party to the Convention, including Australia, Canada and the United Kingdom.

- ^ UN OHCHR (2012). Committee on the Rights of the Child. Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights. Retrieved 1 May 2012.

- ^ UN (2006) «Study on Violence against Children presented by Independent Expert for the Secretary-General». United Nations, A/61/299. See further: UN (2012e). Special Representative of the Secretary-General on Violence against Children Archived 8 March 2022 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 1 May 2012.

- ^ UN (2007) United Nations General Assembly, A/RES/62/141. The United States was the only country to vote against. There were no abstentions.

- ^ a b Abolishing corporal punishment of children : questions and answers (PDF). Strasbourg: Council of Europe. 2007. ISBN 978-9-287-16310-3. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 August 2014.

- ^ «Aruba has prohibited all corporal punishment of children — Global Initiative to End All Corporal Punishment of Children». Archived from the original on 6 March 2018. Retrieved 6 March 2018.

- ^ Durrant, Joan E. (1996). «The Swedish Ban on Corporal Punishment: Its History and Effects». In Frehsee, Detlev; et al. (eds.). Family Violence Against Children: A Challenge for Society. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter. pp. 19–25. ISBN 3-11-014996-6.

- ^ «To spank or not to spank?». CBC News. 31 July 2009. Retrieved 17 September 2012.

- ^ Barnett, Laura. «The «Spanking» Law: Section 43 of the Criminal Code». Parliament of Canada. Archived from the original on 16 October 2012. Retrieved 17 September 2012.

- ^ «Wales introduces ban on smacking and slapping children». The Guardian. London. 21 March 2022. Retrieved 21 March 2022.

- ^ Wajeeh, Ul Hassan. «Pakistan Penal Code (Act XLV of 1860)». Retrieved 8 February 2017.

- ^ Ghosh, Arijit; Pasupathi, Madhumathi (18 August 2016). «Perceptions of Students and Parents on the Use of Corporal Punishment at Schools in India» (PDF). Rupkatha Journal on Interdisciplinary Studies in Humanities. 8 (3): 269–280. doi:10.21659/rupkatha.v8n3.28.

- ^ «Corporal Punishment to Children’s Hands»,

A Statement by Medical Authorities as to the Risks, January 2002. - ^ McKirdy, Euan (14 July 2018). «Gay men, adulterers publicly flogged in Aceh, Indonesia». CNN. Retrieved 15 July 2018.

- ^ «Saudi Arabia to end flogging as form of punishment — document». Reuters. 24 April 2020. Retrieved 25 April 2020.

- ^ Walsh, Declan. «Video of girl’s flogging as Taliban hand out justice», The Guardian, London, 2 April 2009.

- ^ Campaign against the Arms Trade, Evidence to the House of Commons Select Committee on Foreign Affairs, London, January 2005.

- ^ «Lashing Justice», Editorial, The New York Times, 3 December 2007.

- ^ «Saudi Arabia: Court Orders Eye to Be Gouged Out», Human Rights Watch, 8 December 2005.

- ^ Oxford English Dictionary, 2nd edition, 1989, «corporal punishment: punishment inflicted on the body; originally including death, mutilation, branding, bodily confinement, irons, the pillory, etc. (as opposed to a fine or punishment in estate or rank). In 19th c. usually confined to flogging or similar infliction of bodily pain.»

- ^ «Physical punishment such as caning or flogging» – Concise Oxford Dictionary.

- ^ «… inflicted on the body, esp. by beating.» – Oxford American Dictionary of Current English.

- ^ «mostly a euphemism for the enforcement of discipline by applying canes, whips or birches to the buttocks.» – Charles Arnold-Baker, The Companion to British History, Routledge, 2001.

- ^ «Physical punishment such as beating or caning» – Chambers 21st Century Dictionary.

- ^ «Punishment of a physical nature, such as caning, flogging, or beating.» – Collins English Dictionary.

- ^ «the striking of somebody’s body as punishment» – Encarta World English Dictionary, MSN. Archived 31 October 2009.

- ^ «Confirming Torture: The Use of Imaging in Victims of Falanga». Forensic Magazine. 6 August 2014. Retrieved 6 April 2017.

- ^ «Mayor may axe child spanking rite», BBC News Online, 21 September 2004.

- ^ Ackroyd, Peter. London: The Biography, Chatto & Windus, London, 2000. ISBN 1-85619-716-6

- ^ babastudio. «Whipping away infertility at Easter». Bohemian Magic. Retrieved 18 November 2019.

- ^ Prucha, Emily (31 March 2012). «What’s Easter without a Whipping?». InCultureParent. Retrieved 18 November 2019.

- ^ [1]| Reynolda House Museum of American Art

Further readingEdit

- Barathan, Gopal; The Caning of Michael Fay, (1995). A contemporary account of an American teenager ( Michael P. Fay ) caned for vandalism in Singapore.

- Gates, Jay Paul and Marafioti, Nicole; (eds.), Capital and Corporal Punishment in Anglo-Saxon England, (2014). Woodbridge: Boydell & Brewer.

- Moskos, Peter; In Defence of Flogging, (2011). An argument that flogging might be better than jail time.

- Scott, George; A History of Corporal Punishment, (1996).

External linksEdit

- «Spanking» Archived 4 January 2011 at the Wayback Machine (Ontario Consultants on Religious Tolerance)

- Center for Effective Discipline (USA)

- World Corporal Punishment Research

- Global Initiative to End All Corporal Punishment of Children

By Tim Lambert

Corporal punishment is derived from a Latin word meaning body. It meant physical punishment and in the past, it was very common. In the past corporal punishment was by no means limited to children. It was used on adults as well.

Whipping has been a common punishment since ancient times. In England from the Middle Ages, whipping was a common punishment for minor crimes. In the 18th century, whipping was a common punishment in the British army and navy. However, it was abolished in the army and navy in 1881.

Whipping women was made illegal in 1820. In 1862 the courts were allowed to sentence men to either whipping or birching. Birching was another form of corporal punishment. This punishment meant beating a man across the bare backside with a bundle of birch rods. In the early 20th century whipping was gradually replaced by birching or imprisonment. In Britain, birching or whipping was banned for civilian men in 1948.

But it was still used in prisons. Birching was last used in prison in 1962. Whipping and birching were abolished in British prisons in 1967.

In the USA whipping was last used as a punishment in Delaware in 1952 when a man was sentenced to 20 lashes. Delaware was the last state to abolish whipping as a punishment, in 1972.

Meanwhile for thousands of years until the late 20th century, teachers beat children. In The Ancient World, the teachers were strict and often beat the pupils. In the Middle Ages discipline was also severe. Boys were beaten with rods or birch twigs. Punishments in Tudor schools were still harsh. Boys were hit with a bundle of birch rods on their bare backside.

Furthermore in Britain in the 19th century children were hit at work. In the early 19th century in textile mills, children who were lazy were hit with leather straps. Furthermore, lazy children sometimes had their heads ducked in a container of water.

Modern Corporal Punishment

Corporal Punishment in British Schools

In Britain in the 19th century hitting boys and girls with a bamboo cane became popular. In the 20th century, the cane was used in both primary and secondary schools.

Meanwhile, the ruler was a punishment commonly used in primary schools in the 20th century. The teacher hit the child on the hand with a wooden ruler. The slipper was often used in secondary schools. The slipper is a euphemism. Normally it was a trainer or a plimsoll. Teachers (usually PE teachers) used a trainer to hit children on the backside.

The tawse was a punishment used in Scottish schools. It was a leather strap with tails. It was used in Scotland to hit a child’s hand. Meanwhile, in the 20th century, the leather strap was also used in some English schools. Children were either hit across the hands or the backside.

Britain was behind most of Europe. In Britain, the Plowden Report was published in 1967. (It was named after its chair, Lady Plowden). It recommended the abolition of corporal punishment in primary schools.

In the late 1960s and early 1970s, the cane was abolished in most primary schools. As society’s attitudes changed the abolition of corporal punishment in secondary schools became inevitable. In 1982, in a case brought by two Scottish mothers, the European Court of Human Rights ruled that beating children against their parent’s wishes was a violation of the European Convention on Human Rights. Finally, in Britain, corporal punishment was banned in state-funded schools in 1987.

But it persisted longer in private schools. Corporal punishment was banned in private schools in England in 1999. In Scotland, it was banned in 2000, and in Northern Ireland in 2003.

Four independent Christian schools appealed against the law against corporal punishment arguing that it breached their right to freedom of religion. But the House of Lords rejected their appeal in February 2005. That was the final nail in the coffin of corporal punishment in British schools.

Corporal Punishment in Schools in Other Countries

The first country to abolish corporal punishment in schools was Poland in 1783. Luxembourg followed in 1845. Other countries abolished it in the 20th century.

Following a revolution in 1917 Russia banned corporal punishment in schools. The Netherlands abolished it in 1920. Italy banned it in 1928. Norway did so in 1936. Sweden ended corporal punishment in all schools in 1958. It was abolished in all schools in Denmark in 1967 and it was banned in Austria in 1975. In Ireland, all corporal punishment in schools was ended in 1982. Spain banned it in 1985.

In Canada, the first province to ban corporal punishment in schools was British Columbia in 1973. Other provinces followed and finally, the Canadian Supreme Court banned it across the country in 2004.

Corporal punishment was banned in schools in New Zealand in 1990.

In Australia, New South Wales led the way. Corporal punishment was banned in government schools in 1990 and in non-government schools in 1995. All the other states followed except Queensland where it remains legal in non-government schools.

The first state of the USA to ban corporal punishment in schools was New Jersey in 1867. But it was more than a hundred years before any other state did.

In 1972 Massachusetts banned it in public schools. Many states followed but today corporal punishment is still legal in public schools in 19 US states. (It’s legal in private schools in all states except New Jersey and Iowa).

At the present time, corporal punishment in schools has been banned completely in 132 countries.

Corporal Punishment by Parents

Throughout history, until recently most parents hit their children. In the 20th century, they sometimes used implements like belts, slippers, hairbrushes, and wooden spoons.

However, in the late 20th century and early 21st century, public opinion turned against corporal punishment and in many countries, it has been banned. The first country to ban parents from hitting children was Sweden in 1979. Finland followed in 1983. So did Norway in 1987 and Austria in 1989. Many other countries followed.

The first English-speaking country to ban corporal punishment by parents was New Zealand in 2007. In 2019 parents in Jersey were banned from hitting children. Scotland banned smacking children in 2020. Corporal punishment became illegal in Wales in March 2022. However, it is still legal in England.

Also in 2022, Zambia banned corporal punishment. So did Cuba and Mauritius. Today, across the World public opinion is turning against corporal punishment.

A Timeline of Corporal Punishment

1783 Poland is the first country to ban corporal punishment in schools

1820 In Britain whipping is banned for women

1845 Luxembourg bans corporal punishment in schools

1862 In Britain courts can sentence men to either whipping or birching. (A man was hit on his bare backside with a bundle of birch rods).

1867 New Jersey is the first US state to ban corporal punishment in schools

1881 Flogging is abolished in the British army and navy

1917 Russia bans corporal punishment in schools

1920 The Netherlands bans corporal punishment in schools

1928 Italy bans corporal punishment in schools

1936 Norway bans corporal punishment in schools

1948 In Britain whipping and birching are banned for civilian men (but not for men in prisons). Romania bans corporal punishment in schools.

1952 In the USA whipping is last used as a punishment, in Delaware when a man is sentenced to 20 lashes.

1958 Sweden ends corporal punishment in schools

1962 Birching is last used in a British prison

1967 Denmark ends corporal punishment in schools. In Britain, the Plowden Report recommends the end of corporal punishment in primary schools (but not secondary schools). Whipping and birching are made illegal in British prisons.

1972 Massachusetts bans corporal punishment in public schools. Delaware is the last US state to abolish whipping as a punishment for criminals. In Britain, on 17 May 10,000 schoolchildren go on strike against corporal punishment.

1973 British Columbia is the first Canadian province to ban corporal punishment in schools. The state of Hawaii bans corporal punishment in public schools.

1975 Austria ends corporal punishment in schools. The state of Maine bans corporal punishment in public schools.

1977 The state of Rhode Island bans corporal punishment in public schools. So does the District of Columbia.

1979 Sweden bans all corporal punishment, including by parents

1982 Ireland ends corporal punishment in schools. In a case brought by two Scottish mothers, the European Court of Human Rights rules that beating children against their parent’s wishes is a violation of the European Convention on Human Rights.

1983 The state of New Hampshire bans corporal punishment in public schools. Finland bans all corporal punishment, including by parents.

1985 The states of Vermont and New York ban corporal punishment in public schools. Spain bans corporal punishment in schools.

1986 China bans corporal punishment in schools. The state of California bans corporal punishment in public schools.

1987 In Britain corporal punishment is banned in state schools (but not private ones). The Philippines bans corporal punishment in both state and private schools. Norway bans all corporal punishment, including by parents.

1988 The states of Nebraska and Wisconsin ban corporal punishment in public schools

1989 The states of Alaska, Connecticut, Michigan, Minnesota, North Dakota, Oregon, and Virginia ban corporal punishment in public schools. The state of Iowa bans corporal punishment in both public and private schools. Austria bans all corporal punishment, including in the home.

1990 New Zealand bans corporal punishment in schools. Western Australia is the first Australian state to ban corporal punishment in government schools (but it is not banned in non-government schools until 1995). The state of South Dakota bans corporal punishment in public schools.

1991 The state of Montana bans corporal punishment in public schools

1992 The state of Utah bans corporal punishment in public schools

1993 The states of Illinois, Utah, Washington, and Maryland ban corporal punishment in public schools

1994 The state of West Virginia bans corporal punishment in public schools. Cyprus bans all corporal punishment, including in the home.

1997 Denmark bans all corporal punishment including in the home

1998 The United Arab Emirates bans corporal punishment in schools. Latvia and Austria ban all corporal punishment.

1999 In England corporal punishment in private schools becomes illegal. Croatia bans all corporal punishment, including by parents.

2000 In Scotland corporal punishment in private schools becomes illegal. Germany and Bulgaria ban all corporal punishment, including in the home.

2002 Turkmenistan and Israel ban all corporal punishment

2003 The state of Delaware bans corporal punishment in public schools. In Northern Ireland corporal punishment in private schools becomes illegal. Iceland bans all corporal punishment, including by parents.

2004 The Canadian Supreme Court bans corporal punishment in schools. Ukraine and Romania ban all corporal punishment, including in the home.

2005 The state of Pennsylvania bans corporal punishment in public schools. Vietnam bans corporal punishment in schools. Hungary bans all corporal punishment, including in the home.

2006 Greece bans all corporal punishment

2007 New Zealand, The Netherlands, Spain, Portugal, Togo, and Uruguay ban all corporal punishment

2008 Costa Rica, Liechtenstein, and the Republic of Moldova ban all corporal punishment

2009 The state of Ohio bans corporal punishment in public schools

2010 Kenya, Tunisia, The Republic of Congo, Albania, and Poland ban all corporal punishment.

2011 The state of New Mexico bans corporal punishment in public schools. Pakistan bans corporal punishment in schools. South Sudan bans all corporal punishment.

2013 Honduras and North Macedonia ban all corporal punishment

2014 Brazil, Bolivia, Nicaragua, Argentina, Malta, San Marino, Andorra, and Estonia ban all corporal punishment

2015 Ireland, Peru, and Benin ban all corporal punishment

2016 Greenland, Slovenia, Montenegro, Paraguay, and Mongolia ban all corporal punishment

2017 Lithuania bans all corporal punishment

2018 Nepal bans all corporal punishment

2019 Jersey, South Africa, Georgia, Kosovo, France, and French Guiana ban all corporal punishment

2020 Scotland, Guinea, Seychelles, and Japan ban all corporal punishment

2021 South Korea, Colombia, and Venezuela ban all corporal punishment

2022 All corporal punishment becomes illegal in Wales and in Zambia and Mauritius. Cuba bans corporal punishment in the home.

The Case Against spanking – American Psychological Association

A WHO factsheet about corporal punishment and the harm it causes

Endhitting USA

Last Revised 2023

«The naughty children»; German Caricature of 1849.

Corporal punishment is forced pain intended to change or punish a person’s behavior. Historically speaking, most punishments, whether in judicial, domestic, or educational settings, were corporal in basis. In modern days, corporal punishment has been largely rejected in favor of other disciplinary methods. Modern judiciaries often favor fines or incarceration, whilst modern school discipline generally avoids physical correction altogether. There has been much dispute over where the line should be drawn between corporal punishment and torture, or whether any physical punishment methods are acceptable at all.

As humankind has advanced, recognizing the human rights of all, especially those of children, the use of corporal punishment has declined, and been outlawed in many societies. Yet, the need to discipline those who violate the norms or laws of their society remains. Childrearing and schooling both require guidance from an authority figure, who must have at their disposal appropriate methods of disciplining those who deviate from acceptable behavior. In a caring society, however, those methods need not involve physical pain; alternatives exist and are preferable, bringing about the same result. Equally, those who violate the law can be incarcerated rather than whipped or otherwise physically punished.

History of corporal punishment

While the early history of corporal punishment is unclear, the practice was certainly present in classical civilizations, being used in Greece, Rome, Egypt, and Israel, for both judicial and educational discipline. Practices varied greatly, though scourging and beating with sticks were common. Some states gained a reputation for using such punishments cruelly; Sparta, in particular, used frequent part of a disciplinary regime designed to build willpower and physical strength. Although the Spartan example was unusually extreme, corporal punishment was possibly the most common type of punishment.

In Medieval Europe, corporal punishment was encouraged by the attitudes of the medieval church towards the human body, with flagellation being a common means of self-discipline. In particular, this had a major influence on the use of corporal punishment in schools, as educational establishments were closely attached to the church during this period. Nevertheless, corporal punishment was not used uncritically; as early as the eleventh century Saint Anselm, Archbishop of Canterbury was speaking out against what he saw as the cruel treatment of children.[1]

From the sixteenth century onwards, new trends were seen in corporal punishment. Judicial punishments were increasingly made into public spectacles, with the public beatings of criminals intended as a deterrent to other would-be miscreants. Meanwhile, early writers on education, such as Roger Ascham, complained of the arbitrary manner in which children were punished.[2] Probably the most influential writer on the subject was the English philosopher John Locke, whose Some Thoughts Concerning Education explicitly criticized the central role of corporal punishment in education. Locke’s work was highly influential, and in part influenced Polish legislators to ban corporal punishment from Poland’s schools in 1783.[3]

During the eighteenth century, the frequent use of corporal punishment was heavily criticized, both by philosophers and legal reformers. Merely inflicting pain on miscreants was seen as inefficient, influencing the subject merely for a short period of time and effecting no permanent change in their behavior. Critics believed that the purpose of punishment should be reformation, not retribution. This is perhaps best expressed in Jeremy Bentham’s idea of a panoptic prison, in which prisoners were controlled and surveyed at all times, perceived to be advantageous in that this system reduced the need of measures such as corporal punishment.[4]

A consequence of this mode of thinking was a diminution of corporal punishment throughout the nineteenth century in Europe and North America. In some countries this was encouraged by scandals involving individuals seriously hurt during acts of corporal punishment. For instance, in Britain, popular opposition to punishment was encouraged by two significant cases, the death of Private Frederick John White, who died after a military flogging in 1847, and the death of Reginald Cancellor, who was killed by his schoolmaster in 1860.[5] Events such as these mobilized public opinion, and in response, many countries introduced thorough regulation of the infliction of corporal punishment in state institutions.

The use of corporal punishment declined through the twentieth century, though the practice has proved most persistent as a punishment for violation of prison rules, as a military field punishment, and in schools.

Administration of punishment

In formal punishment, medical supervision is often considered necessary to assess whether the target of punishment is in a fit condition to be beaten and to oversee the punishment to prevent serious injury from occurring. The role of the medical officer was particularly important in the nineteenth century, a time in which severe punishment was common, but growing public criticism of the practice encouraged medical regulation.

Corporal punishment can be directed at a number of different anatomical targets, the choice depending on a number of factors. The humiliation and pain of a particular punishment have always been primary concerns, but convenience and custom are also factors. There is an additional concern in the modern world about the permanent harm that can result from punishment, though this was rarely a factor before the nineteenth century. The intention of corporal punishment is to discipline an individual with the infliction of a measure of pain, and permanent injury is considered counterproductive.

- Most commonly, corporal punishment is directed at the buttocks, with some languages having a specific word for their chastisement. For example, the French call this fessée, the Spanish nalgada. The English term «spanking» refers to punishment on the buttocks, though only with the open hand. This part of the body is often chosen because it is painful, but is arguably unlikely to cause long-term physical harm. In the United Kingdom the term spanking is becoming more associated with sex play and the term smacking is used more often.

- The back is commonly targeted in military and judicial punishments, particularly popular in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. However, damage to both spine and kidneys is possible and such punishment is rarely used in the modern world.

- Although the face and particularly the cheeks may be struck in domestic punishment, formal punishments avoid the head because of the serious injuries that can result. In some countries, domestic and school punishments aimed at the head are considered assault.

- The hands are a common target in school discipline, though rarely targeted in other forms of corporal punishment. Since serious injury can be caused by striking the hand, the implements used and the numbers of blows must be strictly controlled.

- In Western Asia, corporal punishment was directed against the feet. Although this was mostly used on criminals, a version was in use in schools in the region.

One common problem with corporal punishment is the difficulty with which an objective measure of pain can be determined and delivered. In the nineteenth century, scientists such as Alexander Bain and Francis Galton suggested scientific solutions to this, such as the use of electricity.[6] These were, however, unpopular and perceived as cruel. The difficulty in inflicting a set measure of pain makes it difficult to distinguish punishment from abuse, and has contributed to calls for the abolition of the practice.

Types

Spanking

Political cartoon from 1860 depicting Stephen A. Douglas receiving a traditional “over-the-knee” spanking from Columbia as Uncle Sam looks on approvingly.

Spanking, by today’s definition, consists of striking the buttocks, with either an open hand or various implements including a cane, a belt, or strap, various types of whips, such as the martinet and the tawse, a switch or other form of rod, a paddle, some curious devices such as the electric so-called spanker and trickster paddling machines, or various household objects designed for other purposes, such as a slipper, a wooden spoon, a bath brush, a wooden ruler, or a hairbrush. Spanking (or smacking) is the most commonly-used form of corporal punishment, consisting of one or more sharp smacks applied on the buttocks.

The verb to spank has been known in English since 1727, possibly onomatopeic in nature.

It is remarkable that English and several other languages have a specific, common verb for spanking, that distinguishes it from corporal punishment applied to parts of the anatomy other than the buttocks. Thus, in Latin, the only word derived from culus (buttocks) was culare, meaning «to spank,» similar to the Italian sculacciare; in French, the verb is fesser, also from «fesses» (buttocks). All of these terms testify to the historical or persisting prominence of this punitive target in many cultures.

Birching

Birching is a corporal punishment with a birch rod, typically applied to the recipient’s bare buttocks, although occasionally to the back and/or shoulders.

A birch rod (often shortened to «birch») is a bundle of leafless twigs bound together to form an implement for flagellation.

Contrary to what the name suggests, a birch rod is not a single rod and is not necessarily made from a birch tree, but can also be made from various other strong but flexible trees or shrubs, such as willow (hence the term willowing). A hazel rod is very tough, and therefore particularly painful; a bundle of four or five hazel twigs was used from 1960 until 1976 on the Isle of Man, the last place in Europe to use birching as a judicial penalty.

Another parameter for the severity of a birch rod is its size—its length, weight and number of branches. In some penal institutions, several versions were in use, which were often given names. For example, in Dartmoor Prison the device used to punish male offenders above the age of 16—weighing some 16 ounces and a full 48 inches long—was known as the «senior birch.»

There have been differing opinions as to the utility of soaking the birch in liquid before use, but as it takes in water the weight is certainly increased without compensatory air resistance, so the impact must be greater if the operator can use sufficient force.

In the 1860s, the Royal Navy abandoned the use of the cat o’ nine tails on boy seamen. The cat had acquired a nasty reputation because of its frequent use in prisons, and was replaced by the birch, with which the wealthy classes were more familiar, having been chastised with it at their private schools. The judicial system followed the Navy’s example and switched to birches also. In an attempt to standardize the Navy’s birches the Admiralty had specimens according to all prevailing prescriptions, called «patterned birch» (as well as a «patterned cane»), kept in every major dockyard, for birches had to be procured on land in quantities, suggesting some were worn out on the sore bottoms of miscreant boys.

The term judicial birch refers to the severe type in use for court-ordered birchings, especially the Manx hazel birch. A 1951, memorandum (possibly confirming earlier practice) ordered all UK male prisons to use only birches (and cats o’ nine tails) from a national stock at south London’s Wandsworth prison, where they were to be «thoroughly» tested before being supplied in triplicate to a prison whenever a procedure was pending for use as prison discipline.

By contrast, terms like Eton birch (after the most prestigious private school in England) are used for a birch made from birch tree twigs.

Caning

Caning is a physical punishment consisting of a number of hits (known as «strokes» or «cuts») with a wooden cane, generally applied to the bare or clad buttocks, shoulders, hand(s) (palm, rarely knuckles), or even the soles of the feet (as in falaka). The size and flexibility of the cane itself and the number and mode of application of the strokes (usually more numerous and faster when wielding a light, flexible cane) vary significantly.

Paddle

A spanking paddle is a usually wooden instrument with a long, flat face and narrow neck, so called because it is roughly shaped like the piece of sports equipment, but existing in more varied sizes and dimensions (length, width, and thickness), used to administer a spanking to the buttocks; it would be too hard and heavy to use safely on the back. A spanking paddle can sometimes be called shingle, apparently after its form, or be given names (rather like weapons in military and police units). Educators and children in households where a paddle is used for discipline sometimes award the paddle such nicknames also, such as «Lola’s bane,» «The ‘Board’ of Education,» and «Mother’s Little Helper.» (Confusingly, sometimes non-wooden flat devices, such as leather straps, are wrongly called paddles, even in official institutions.)

The term fraternity paddle (its more recent counterpart is sorority paddle) was introduced for hazing or punishment, which was often kept by an alumnus (to discipline his or her children), especially if it carries Greek-organization markings. It is still commonly offered by pledges («little Brothers» or -sisters) to their «big Brothers» or «big Sisters» as a gift. It is a symbol of their induction to the sorority or fraternity.

Ritual

Corporal punishment in formal settings, such as schools and prisons, is often highly ritualized, sometimes even staged in a highly theatrical manner. To a great extent, the spectacle of punishment is intended to act as a deterrent to others and a theatrical approach is one result of this.

One consequence of the ritualized nature of much punishment has been the development of a wide variety of equipment used. Formal punishment often begins with the victim stripped of some or all of their clothing and secured to a piece of furniture, such as a trestle, frame, punishment horse or falaka. A variety of implements are then used to inflict blows on the victim. The terms used to describe these are not fixed, varying by country and by context. There are, however, a number of common types which are frequently encountered when reading about corporal punishment. These are:

- The bastinado

- The rod—a thin, flexible rod is often called a switch

- The birch, a number of strong, flexible branches, bound together in their natural state

- The bamboo canes—a durable rottan cane is often called a rattan

- The paddle, a flat wooden board or leather pad with a handle

- The strap—a strap with a number of tails at one end is called a tawse in Scotland and northern England

- The whip—varieties include the Russian knout and South African sjambok, in addition to the scourge and martinet

- The cat o’ nine tails was a popular implement used in naval discipline

- The hairbrush and belt are traditionally used in the United States and Great Britain as an implement for domestic spanking

- The wooden spoon, commonly used in Australia

- The wired clothes hanger, a common and easily available substitute for a bamboo canes in Hong Kong

In some instances, the victim of punishment is required to prepare the implement which will be used upon them. For instance, sailors were employed in preparing the cat o’ nine tails which would be used upon their own back, whilst children were sent to cut a switch or rod.

In contrast, informal punishments, particularly in domestic settings, tend to lack this ritual nature and are often administered with whatever object comes to hand. It is common, for instance, for belts, wooden spoons, slippers, or hairbrushes to be used in domestic punishment, whilst rulers and other classroom equipment have been used in schools.

Boys were beaten under the old tradition of «Beating the Bounds,» where a boy was paraded around the boundary of an area of a city or district and would often ask to be beaten on the buttocks. One famous «Beating the Bounds» happened around the boundary of St Giles and the area where Tottenham Court Road now stands in London. The actual stone that separated the boundary is now under the Centerpoint office block.

In law

While the domestic corporal punishment of children is still accepted in some countries (mostly Eastern), it is declining in many others, it is also illegal in a number of countries. The practice has been banned in Austria, Bulgaria, Canada, Croatia, Cyprus, Denmark, Finland, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Iceland, Israel, Italy, Latvia, Norway, Romania, South Africa, Sweden, the Netherlands, Ukraine and New Zealand.[7] These developments are comparatively recent, with Sweden, in 1979, being the first country to forbid corporal punishment by law.[8] In a number of other countries there is active debate about its continued usage. In the United Kingdom its total abolition has been discussed.

United Nations human rights standards prohibit all corporal punishment.[9]

Such debates, however, do not always lead to the banning of domestic corporal punishment and The Supreme Court of Canada recently reaffirmed, in Foundation v. Canada, the right of a parent or guardian to use corporal punishment on children between the ages of two and twelve; this decision was contentious, being based upon s.43 of the Criminal Code of Canada, a provision enacted in 1892.[10] Similarly, despite some opposition to corporal punishment in the U.S., spanking children is legal, with some states explicitly allowing it in their law and 23 U.S. states allowing its use in public schools.[11]

In most parts of Eastern Asia (including China, Taiwan, Japan, and Korea), it is legal to punish one’s own child using physical means. In Singapore and Hong Kong, punishing one’s own child with corporal punishment is either legal but discouraged, or illegal but without active enforcement of the relevant laws. Culturally, people in the region generally believe a minimal amount of corporal punishment for their own children is appropriate and necessary, and thus such practice is tolerated by the society as a whole.

The People’s Republic of China and Taiwan have both made corporal punishment against children illegal in the school system, but it is still known to be practiced in some form in many areas. The most common forms of punishment are mild chastisements, such as shaking by the arm or shoulder, or slapping the back of the head or ear; more serious punishments, such as striking with the cane, are less common. Such incidents are increasingly leading to public outcry, and in recent years have lead to the dismissal of teaching staff. Similarly, in South Korea, corporal punishments occur for students if they forget their homework, violate school rules, or are tardy to school.

There is resistance, particularly from conservatives, against making the corporal punishment of children by their parents or guardians illegal. In 2004, the United States declined to become a signatory of the United Nations’s «Rights of the Child» because of its sanctions on parental discipline, citing the tradition of parental authority in that country and of privacy in family decision-making.

Most countries have banned the use of corporal punishment in schools, beginning with Poland in 1783. The practice is still used in schools in some parts of the United States (approximately half the states, but varying by school districts within them), though it is banned in others. Many schools, even within the 23 states, require written parent approval before any physical force is used upon a child.

Criticisms

Many opponents of corporal punishment argue that any form of violence is, by definition, abusive. Psychological research indicates that corporal punishment causes the destruction of trust bonds between parents and children. Children subjected to corporal punishment may grow resentful, shy, insecure, or violent. Adults who report having been slapped or spanked by their parents in childhood have been found to experience elevated rates of anxiety disorder, alcohol abuse or dependence, and externalization of problems as adults.[12] Some researchers believe that corporal punishment actually works against its objective (normally obedience), since children will not voluntarily obey an adult they do not trust. A child who is physically punished may have to be punished more often than a child who is not. Researcher Elizabeth Gershoff, in a 2002 meta-analytic study that combined 60 years of research on corporal punishment, found that the only positive outcome of corporal punishment was immediate compliance; however, corporal punishment was associated with less long-term compliance.[13] Corporal punishment was linked with nine other negative outcomes, including increased rates of aggression, delinquency, mental health problems, problems in relationships with their parents, and likelihood of being physically abused.

Opponents claim that much child abuse begins with spanking: A parent accustomed to using corporal punishment may find it all too easy, when frustrated, to step over the line into physical abuse. One study found that 40 percent of 111 mothers were worried that they could possibly hurt their children.[14] It is argued that frustrated parents turn to spanking when attempting to discipline their child, and then get carried away (given the arguable continuum between spanking and hitting). This «continuum» argument also raises the question of whether a spank can be «too hard» and how (if at all) this can be defined in practical terms. This in turn leads to the question whether parents who spank their children «too hard» are crossing the line and beginning to abuse them.

Before 1997, although there were many studies linking spanking with higher levels of misbehavior in children, people could argue that it was the misbehavior that caused the spanking. However, since that time, several studies have examined changes in behavior over time and propose a link between corporal punishment and increasing relative levels of misbehavior compared to similar children who were not corporally punished. Reasons for corporal punishment possibly causing increased misbehavior in the long run may include: Children imitating the corporally-punishing behavior of their parents by hitting other people; acting out of resentment stemming from corporal punishment; reduced self-esteem; loss of opportunities to learn peaceful conflict resolution; punishing the parents for the acts of corporal punishment; and assertion of freedom and dignity by refusing to be controlled by corporal punishment.

The problem with the use of corporal punishment is that, if punishments are to maintain their efficacy, the amount of force required may have to be increased over successive punishments. This was observed by the American Academy of Pediatrics, which stated that: «The only way to maintain the initial effect of spanking is to systematically increase the intensity with which it is delivered, which can quickly escalate into abuse.» Additionally, the Academy noted that: «Parents who spank their children are more likely to use other unacceptable forms of corporal punishment.»[15]

Another problem with corporal punishment, according to the skeptics, is that it polarizes the parent-child relationship, reducing the amount of spontaneous cooperation on the part of the child. The AAP policy statement says «…reliance on spanking as a discipline approach makes other discipline strategies less effective to use.» Thus it has an addiction-like effect: The more one spanks, the more one feels a need to spank, possibly escalating until the situation is out of control.

Notes

- ↑ J. Wicksteed, The Challenge of Childhood (London: Chapman & Hall Ltd., 1936), 34-35.

- ↑ Roger Ascham, The Schoolmaster (London: John Daye, 1571), 1.

- ↑ P. Newell, A Last Resort? Corporal Punishment in Schools (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1972), 9.

- ↑ Jeremy Bentham, Chrestomathia (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1983), 34, 106.

- ↑ J. Middleton and Thomas Hopley, «Mid-Victorian attitudes to corporal punishment,» History of Education (2005).

- ↑ Alexander Bain, Mind and Body (London: Henry S. King & Co., 1873), 65.

- ↑ New Zealand Herald, Anti-smacking bill becomes law. Retrieved May 16, 2007.

- ↑ Save The Children Sweden, What we do.

- ↑ www.endcorporalpunishment.org, Hitting people is wrong—and children are people too. Retrieved April 10, 2007.

- ↑ CBC, To Spank or Not to Spank? Retrieved July 29, 2007.

- ↑ www.stophitting.com, Facts About Corporal Punishment. Retrieved July 29, 2007.

- ↑ H.L. MacMillan, et al., Slapping and spanking in childhood and its association with lifetime prevalence of psychiatric disorders in a general population. Canadian Medical Association Journal 1999; 161(7):805-9.

- ↑ E. Gershoff, «Corporal punishment by parents and associated child behaviors and experiences: A meta-analytic and theoretical review, Psychological Bulletin, 2002; 128(4):539-579.

- ↑ M. Straus, Beating the Devil out of Them: Corporal Punishment in American Families and Its Effects on Children (New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers, 2001, ISBN 0765807548).

- ↑ A.M. Graziano, J. L. Hamblen, and W. A. Plante. «Subabusive violence in child rearing in middle-class American families,» Pediatrics 1996; 98:845-848.

References

ISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Cooper, William. A History of the Rod, 2003. ISBN 1899861203

- Gibson, Ian. The English Vice: Beating, Sex, and Shame in Victorian England and After. London: Gerald Duckworth & Co Ltd., 1978. ISBN 0715612646

- Hardy, Janet. The Toybag Guide to Canes and Caning. Greenery Press, 2004. ISBN 1890159565

- Newman, Graeme. Just And Painful: A Case for Corporal Punishment of Criminals. Criminal Justice Press, 1995. ISBN 0911577335

- Scott, George. The History of Corporal Punishment. Merchant Book Company, 1996. ISBN 1859584934

- Strauss, Murray. Beating the Devil Out of Them: Corporal Punishment in American Families. Lexington Books, 1994. ISBN 0029317304

External links

All links retrieved April 6, 2022.

- Corporal punishment of children: spanking/whipping/caning Ontario Consultants on Religious Tolerance

- World Corporal Punishment Research, a vast repository of material concerning corporal punishments

- Is Corporal Punishment An Effective Means Of Discipline? (American Psychological Association)

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article

in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

- Corporal_punishment history

- Spanking history

- Birching history

- Caning history

- Paddle_(spanking) history

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

- History of «Corporal punishment»

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

Corporal punishment is a physical punishment which inflicts pain as justice for many different types of offenses. This punishment has been historically used in schools, the home, and the judicial system. While this is a general type of punishment, it is often most associated with children, and the U.N. Committee on the Rights of the Child defined it as “any punishment in which physical force is used and intended to cause some degree of pain or discomfort.”

Corporal Punishment Definition

Corporal punishment exists in varying degrees of severity, from spanking, often used on children and students, to whipping or caning. Currently, severe corporal punishment is largely outlawed.

In many countries, domestic corporal punishment is allowed as reasonable punishment, whereas in others, such as Sweden, all physical punishment of children is prohibited. In schools, physical punishment is outlawed in 128 countries, but is lawful in some situations in Australia, the Republic of South Korea, and the United States (where it is legal in 19 states).

Corporal Punishment in Schools

Corporal punishment has been used widely in schools for thousands of years for legal and religious reasons and has spawned old proverbs such as “spare the rod and spoil the child,” which is a paraphrase of the biblical verse, “He who spares the rod hates his son, but he who loves him is careful to discipline him.” However, this type of punishment is not limited to Christian-majority nations and has been a staple of school discipline across the globe.

The international push to outlaw corporal punishment in schools has been fairly recent. In Europe, the prohibition of physical punishment in schools began in the late 1990s, and in South America in the 2000s. The United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child occurred as recently as 2011.

In the United States, corporal punishment is mostly eradicated from private schools but is legal in public schools. In September of 2018, a school in the state of Georgia garnered national attention by sending home a “consent to paddle” form, informing parents of the renewed use of the paddle, a punishment that mostly disappeared in schools in the past few decades.

Corporal Punishment in the Home

Physical punishment in the home, however, is much more difficult to regulate. In regards to children, it has a similar historical precedent as this type of punishment in schools. According to a report by UNICEF, more than a quarter of caregivers in the world believe that physical punishment is a necessary aspect of the discipline. Many countries that expressly prohibit corporal punishment in schools have not outlawed it in the home.