|

Anton Chekhov |

|

|---|---|

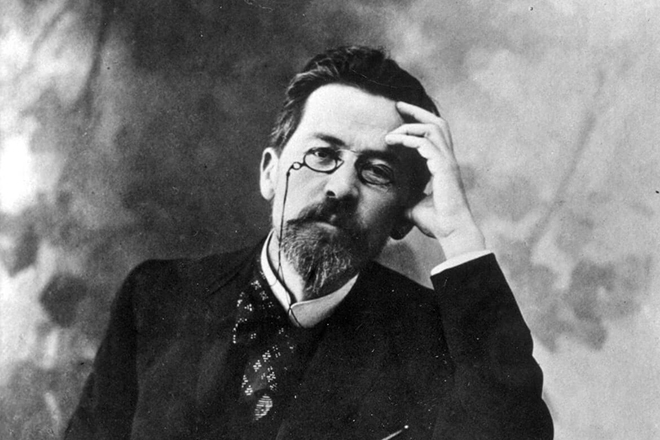

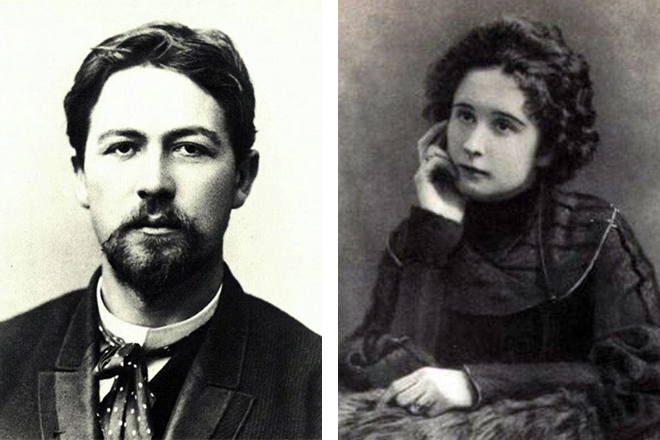

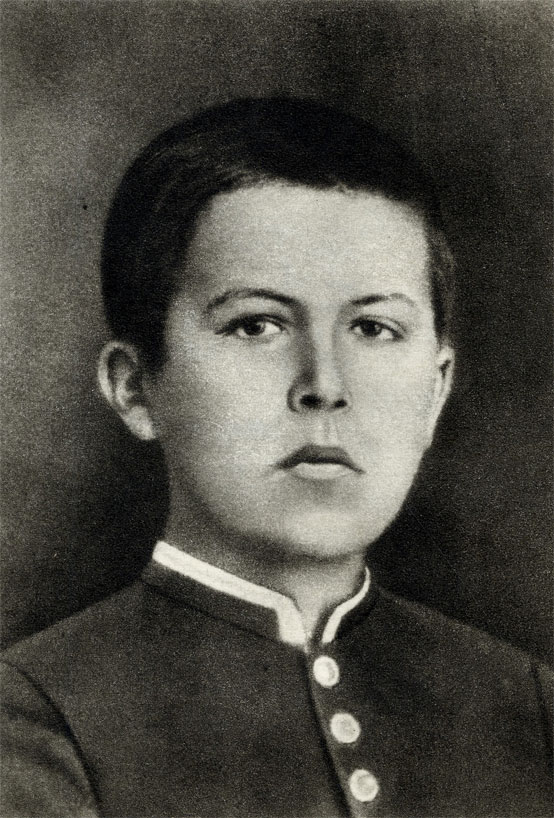

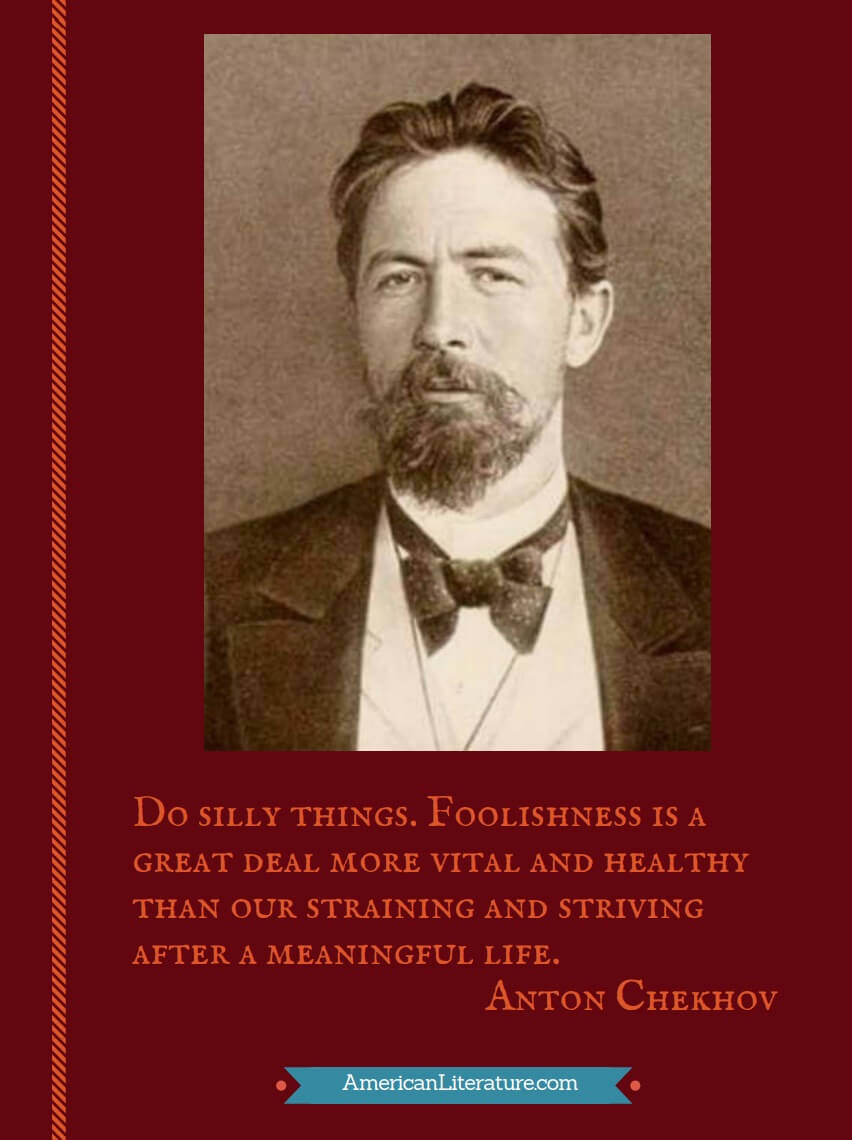

Chekhov in 1889 |

|

| Born | Anton Pavlovich Chekhov 29 January 1860[1] Taganrog, Ekaterinoslav Governorate, Russian Empire |

| Died | 15 July 1904 (aged 44)[2] Badenweiler, Grand Duchy of Baden, German Empire |

| Resting place | Novodevichy Cemetery, Moscow |

| Occupation | Physician, short story writer, playwright |

| Language | Russian |

| Nationality | Russian[3] |

| Alma mater | First Moscow State Medical University |

| Notable awards | Pushkin Prize |

| Spouse |

Olga Knipper (m. 1901) |

| Relatives | Alexander Chekhov (brother) Maria Chekhova (sister) Nikolai Chekhov (brother) Michael Chekhov (nephew) Lev Knipper (nephew) Olga Chekhova (niece) Ada Tschechowa (great-niece) Marina Ried (great-niece) Vera Tschechowa (great-great niece) |

| Signature | |

|

Anton Pavlovich Chekhov (Russian: Антон Павлович Чехов[note 1], IPA: [ɐnˈton ˈpavləvʲɪtɕ ˈtɕexəf]; 29 January 1860[note 2] – 15 July 1904[note 3]) was a Russian[3] playwright and short-story writer who is considered to be one of the greatest writers of all time. His career as a playwright produced four classics, and his best short stories are held in high esteem by writers and critics.[4][5] Along with Henrik Ibsen and August Strindberg, Chekhov is often referred to as one of the three seminal figures in the birth of early modernism in the theatre.[6] Chekhov was a physician by profession. «Medicine is my lawful wife», he once said, «and literature is my mistress.»[7]

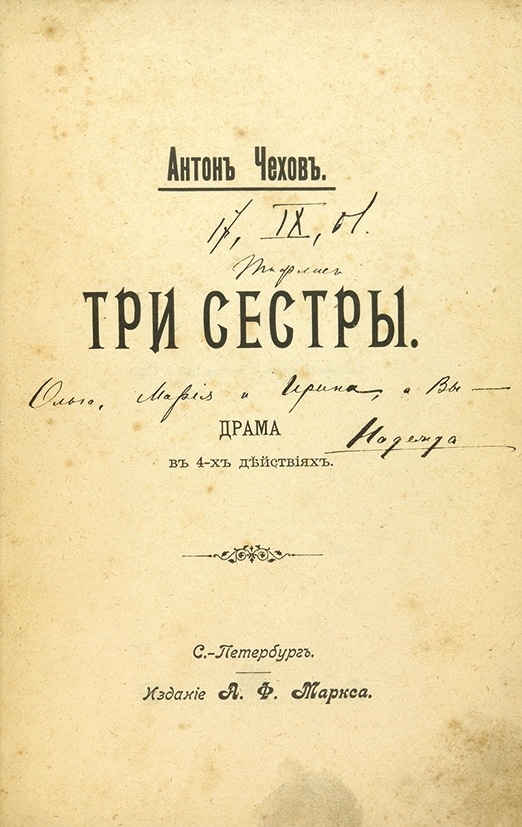

Chekhov renounced the theatre after the reception of The Seagull in 1896, but the play was revived to acclaim in 1898 by Konstantin Stanislavski’s Moscow Art Theatre, which subsequently also produced Chekhov’s Uncle Vanya and premiered his last two plays, Three Sisters and The Cherry Orchard. These four works present a challenge to the acting ensemble[8] as well as to audiences, because in place of conventional action Chekhov offers a «theatre of mood» and a «submerged life in the text».[9] The plays that Chekhov wrote were not complex, but easy to follow, and created a somewhat haunting atmosphere for the audience.[3]

Chekhov at first wrote stories to earn money, but as his artistic ambition grew, he made formal innovations that influenced the evolution of the modern short story.[10] He made no apologies for the difficulties this posed to readers, insisting that the role of an artist was to ask questions, not to answer them.[11]

Biography[edit]

Childhood[edit]

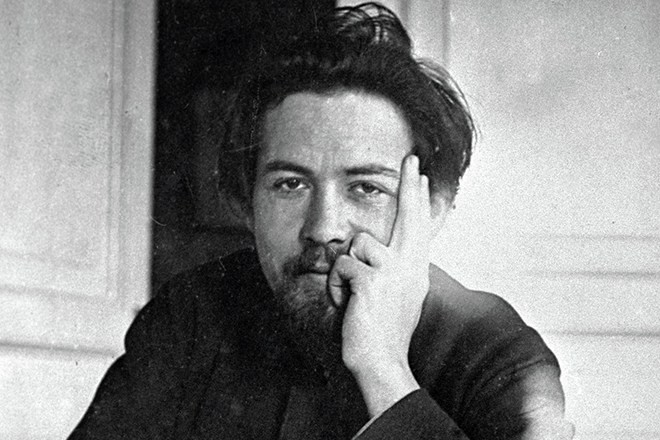

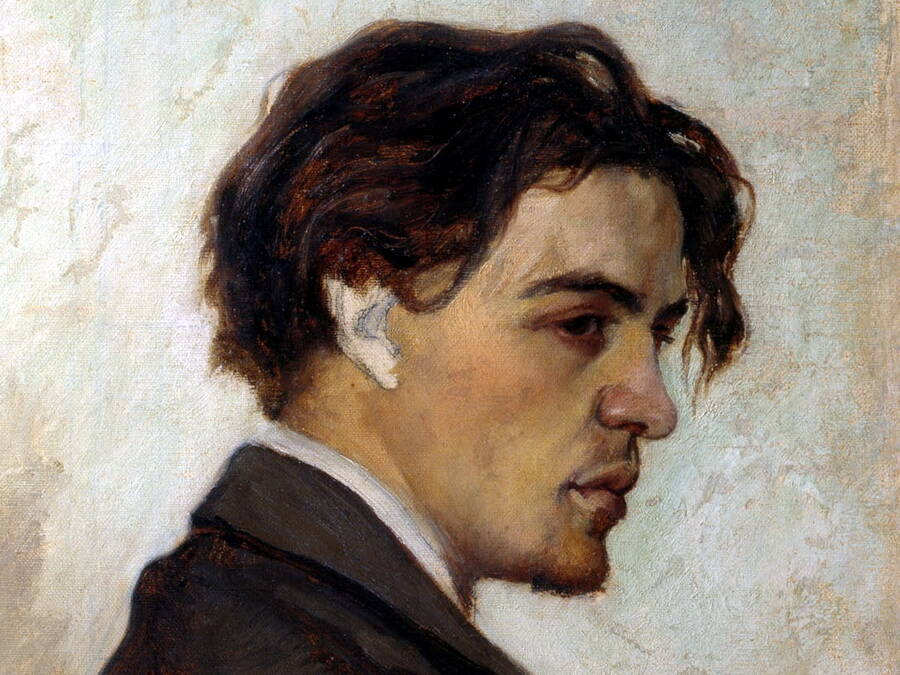

Portrait of young Chekhov in country clothes

Young Chekhov (left) with brother Nikolai in 1882

Anton Chekhov was born into a Russian family on the feast day of St. Anthony the Great (17 January Old Style) 29 January 1860 in Taganrog, a port on the Sea of Azov – on Politseyskaya (Police) street, later renamed Chekhova street – in southern Russia. He was the third of six surviving children. His father, Pavel Yegorovich Chekhov, the son of a former serf and his wife,[12] was from the village Olkhovatka (Voronezh Governorate) and ran a grocery store. A director of the parish choir, devout Orthodox Christian, and physically abusive father, Pavel Chekhov has been seen by some historians as the model for his son’s many portraits of hypocrisy.[13] Chekhov’s mother, Yevgeniya (Morozova), was an excellent storyteller who entertained the children with tales of her travels with her cloth-merchant father all over Russia.[14][15][16] «Our talents we got from our father,» Chekhov remembered, «but our soul from our mother.»[17]

In adulthood, Chekhov criticised his brother Alexander’s treatment of his wife and children by reminding him of Pavel’s tyranny: «Let me ask you to recall that it was despotism and lying that ruined your mother’s youth. Despotism and lying so mutilated our childhood that it’s sickening and frightening to think about it. Remember the horror and disgust we felt in those times when Father threw a tantrum at dinner over too much salt in the soup and called Mother a fool.»[18][19]

Chekhov attended the Greek School in Taganrog and the Taganrog Gymnasium (since renamed the Chekhov Gymnasium), where he was held back for a year at fifteen for failing an examination in Ancient Greek.[20] He sang at the Greek Orthodox monastery in Taganrog and in his father’s choirs. In a letter of 1892, he used the word «suffering» to describe his childhood and recalled:

When my brothers and I used to stand in the middle of the church and sing the trio «May my prayer be exalted», or «The Archangel’s Voice», everyone looked at us with emotion and envied our parents, but we at that moment felt like little convicts.[21]

In 1876, Chekhov’s father was declared bankrupt after overextending his finances building a new house, having been cheated by a contractor named Mironov.[22] To avoid debtor’s prison he fled to Moscow, where his two eldest sons, Alexander and Nikolai, were attending university. The family lived in poverty in Moscow. Chekhov’s mother was physically and emotionally broken by the experience.[23]

Chekhov was left behind to sell the family’s possessions and finish his education. He remained in Taganrog for three more years, boarding with a man by the name of Selivanov who, like Lopakhin in The Cherry Orchard, had bailed out the family for the price of their house.[24] Chekhov had to pay for his own education, which he managed by private tutoring, catching and selling goldfinches, and selling short sketches to the newspapers, among other jobs. He sent every ruble he could spare to his family in Moscow, along with humorous letters to cheer them up.[25]

During this time, he read widely and analytically, including the works of Cervantes, Turgenev, Goncharov, and Schopenhauer,[26][27] and wrote a full-length comic drama, Fatherless, which his brother Alexander dismissed as «an inexcusable though innocent fabrication».[28] Chekhov also experienced a series of love affairs, one with the wife of a teacher.[25] In 1879, Chekhov completed his schooling and joined his family in Moscow, having gained admission to the medical school at I.M. Sechenov First Moscow State Medical University.[29]

Early writings[edit]

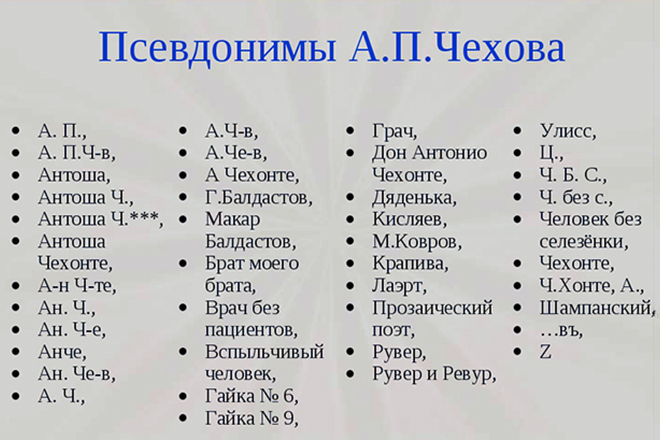

Chekhov then assumed responsibility for the whole family.[30] To support them and to pay his tuition fees, he wrote daily short, humorous sketches and vignettes of contemporary Russian life, many under pseudonyms such as «Antosha Chekhonte» (Антоша Чехонте) and «Man Without Spleen» (Человек без селезенки). His prodigious output gradually earned him a reputation as a satirical chronicler of Russian street life, and by 1882 he was writing for Oskolki (Fragments), owned by Nikolai Leykin, one of the leading publishers of the time.[31] Chekhov’s tone at this stage was harsher than that familiar from his mature fiction.[32][33]

In 1884, Chekhov qualified as a physician, which he considered his principal profession though he made little money from it and treated the poor free of charge.[34]

In 1884 and 1885, Chekhov found himself coughing blood, and in 1886 the attacks worsened, but he would not admit his tuberculosis to his family or his friends.[17] He confessed to Leykin, «I am afraid to submit myself to be sounded by my colleagues.»[35] He continued writing for weekly periodicals, earning enough money to move the family into progressively better accommodations.

Early in 1886 he was invited to write for one of the most popular papers in St. Petersburg, Novoye Vremya (New Times), owned and edited by the millionaire magnate Alexey Suvorin, who paid a rate per line double Leykin’s and allowed Chekhov three times the space.[36] Suvorin was to become a lifelong friend, perhaps Chekhov’s closest.[37][38]

Before long, Chekhov was attracting literary as well as popular attention. The sixty-four-year-old Dmitry Grigorovich, a celebrated Russian writer of the day, wrote to Chekhov after reading his short story «The Huntsman» that[39] «You have real talent, a talent that places you in the front rank among writers in the new generation.» He went on to advise Chekhov to slow down, write less, and concentrate on literary quality.

Chekhov replied that the letter had struck him «like a thunderbolt» and confessed, «I have written my stories the way reporters write up their notes about fires—mechanically, half-consciously, caring nothing about either the reader or myself.»[40] The admission may have done Chekhov a disservice, since early manuscripts reveal that he often wrote with extreme care, continually revising.[41] Grigorovich’s advice nevertheless inspired a more serious, artistic ambition in the twenty-six-year-old. In 1888, with a little string-pulling by Grigorovich, the short story collection At Dusk (V Sumerkakh) won Chekhov the coveted Pushkin Prize «for the best literary production distinguished by high artistic worth».[42]

Turning points[edit]

Chekhov’s family and friends in 1890: (top row, left to right) Ivan, Alexander, father; (second row) Mariya Korniyeeva, Lika Mizinova, Masha, Mother, Seryozha Kiselev; (bottom row) Misha, Anton

In 1887, exhausted from overwork and ill health, Chekhov took a trip to Ukraine, which reawakened him to the beauty of the steppe.[43] On his return, he began the novella-length short story «The Steppe«, which he called «something rather odd and much too original», and which was eventually published in Severny Vestnik (The Northern Herald).[44] In a narrative that drifts with the thought processes of the characters, Chekhov evokes a chaise journey across the steppe through the eyes of a young boy sent to live away from home, and his companions, a priest and a merchant. «The Steppe» has been called a «dictionary of Chekhov’s poetics», and it represented a significant advance for Chekhov, exhibiting much of the quality of his mature fiction and winning him publication in a literary journal rather than a newspaper.[45]

In autumn 1887, a theatre manager named Korsh commissioned Chekhov to write a play, the result being Ivanov, written in a fortnight and produced that November.[46] Though Chekhov found the experience «sickening» and painted a comic portrait of the chaotic production in a letter to his brother Alexander, the play was a hit and was praised, to Chekhov’s bemusement, as a work of originality.[47] Although Chekhov did not fully realise it at the time, Chekhov’s plays, such as The Seagull (written in 1895), Uncle Vanya (written in 1897), The Three Sisters (written in 1900), and The Cherry Orchard (written in 1903) served as a revolutionary backbone to what is common sense to the medium of acting to this day: an effort to recreate and express the realism of how people truly act and speak with each other. This realistic manifestation of the human condition may engender in audiences reflection upon what it means to be human.

This philosophy of approaching the art of acting has stood not only steadfast, but as the cornerstone of acting for much of the 20th century to this day. Mikhail Chekhov considered Ivanov a key moment in his brother’s intellectual development and literary career.[17] From this period comes an observation of Chekhov’s that has become known as Chekhov’s gun, a dramatic principle that requires that every element in a narrative be necessary and irreplaceable, and that everything else be removed.[48][49][50]

Remove everything that has no relevance to the story. If you say in the first chapter that there is a rifle hanging on the wall, in the second or third chapter it absolutely must go off. If it’s not going to be fired, it shouldn’t be hanging there.

— Anton Chekhov[50][51]

The death of Chekhov’s brother Nikolai from tuberculosis in 1889 influenced A Dreary Story, finished that September, about a man who confronts the end of a life that he realises has been without purpose.[52][53] Mikhail Chekhov, who recorded his brother’s depression and restlessness after Nikolai’s death, was researching prisons at the time as part of his law studies, and Anton Chekhov, in a search for purpose in his own life, himself soon became obsessed with the issue of prison reform.[17]

Sakhalin[edit]

In 1890, Chekhov undertook an arduous journey by train, horse-drawn carriage, and river steamer to the Russian Far East and the katorga, or penal colony, on Sakhalin Island, north of Japan, where he spent three months interviewing thousands of convicts and settlers for a census. The letters Chekhov wrote during the two-and-a-half-month journey to Sakhalin are considered to be among his best.[54] His remarks to his sister about Tomsk were to become notorious.[55][56]

Tomsk is a very dull town. To judge from the drunkards whose acquaintance I have made, and from the intellectual people who have come to the hotel to pay their respects to me, the inhabitants are very dull, too.[57]

Chekhov witnessed much on Sakhalin that shocked and angered him, including floggings, embezzlement of supplies, and forced prostitution of women. He wrote, «There were times I felt that I saw before me the extreme limits of man’s degradation.»[58][59] He was particularly moved by the plight of the children living in the penal colony with their parents. For example:

On the Amur steamer going to Sakhalin, there was a convict who had murdered his wife and wore fetters on his legs. His daughter, a little girl of six, was with him. I noticed wherever the convict moved the little girl scrambled after him, holding on to his fetters. At night the child slept with the convicts and soldiers all in a heap together.[60]

Chekhov later concluded that charity was not the answer, but that the government had a duty to finance humane treatment of the convicts. His findings were published in 1893 and 1894 as Ostrov Sakhalin (The Island of Sakhalin), a work of social science, not literature.[61][62] Chekhov found literary expression for the «Hell of Sakhalin» in his long short story «The Murder»,[63] the last section of which is set on Sakhalin, where the murderer Yakov loads coal in the night while longing for home. Chekhov’s writing on Sakhalin, especially the traditions and habits of the Gilyak people, is the subject of a sustained meditation and analysis in Haruki Murakami’s novel 1Q84.[64] It is also the subject of a poem by the Nobel Prize winner Seamus Heaney, «Chekhov on Sakhalin» (collected in the volume Station Island).[65] Rebecca Gould has compared Chekhov’s book on Sakhalin to Katherine Mansfield’s Urewera Notebook (1907).[66] In 2013, the Wellcome Trust-funded play ‘A Russian Doctor’, performed by Andrew Dawson and researched by Professor Jonathan Cole, explored Chekhov’s experiences on Sakhalin Island.

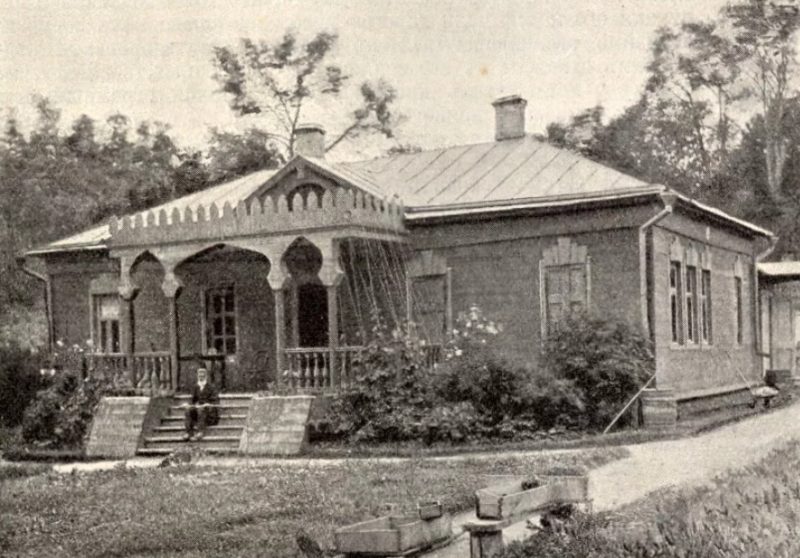

Melikhovo[edit]

Mikhail Chekhov, a member of the household at Melikhovo, described the extent of his brother’s medical commitments:

From the first day that Chekhov moved to Melikhovo, the sick began flocking to him from twenty miles around. They came on foot or were brought in carts, and often he was fetched to patients at a distance. Sometimes from early in the morning peasant women and children were standing before his door waiting.[67]

Chekhov’s expenditure on drugs was considerable, but the greatest cost was making journeys of several hours to visit the sick, which reduced his time for writing.[68] However, Chekhov’s work as a doctor enriched his writing by bringing him into intimate contact with all sections of Russian society: for example, he witnessed at first hand the peasants’ unhealthy and cramped living conditions, which he recalled in his short story «Peasants». Chekhov visited the upper classes as well, recording in his notebook: «Aristocrats? The same ugly bodies and physical uncleanliness, the same toothless old age and disgusting death, as with market-women.»[69] In 1893/1894 he worked as a Zemstvo doctor in Zvenigorod, which has numerous sanatoriums and rest homes. A local hospital is named after him.

In 1894, Chekhov began writing his play The Seagull in a lodge he had built in the orchard at Melikhovo. In the two years since he had moved to the estate, he had refurbished the house, taken up agriculture and horticulture, tended the orchard and the pond, and planted many trees, which, according to Mikhail, he «looked after … as though they were his children. Like Colonel Vershinin in his Three Sisters, as he looked at them he dreamed of what they would be like in three or four hundred years.»[17]

The first night of The Seagull, at the Alexandrinsky Theatre in St. Petersburg on 17 October 1896, was a fiasco, as the play was booed by the audience, stinging Chekhov into renouncing the theatre.[70] But the play so impressed the theatre director Vladimir Nemirovich-Danchenko that he convinced his colleague Konstantin Stanislavski to direct a new production for the innovative Moscow Art Theatre in 1898.[71] Stanislavski’s attention to psychological realism and ensemble playing coaxed the buried subtleties from the text, and restored Chekhov’s interest in playwriting.[72] The Art Theatre commissioned more plays from Chekhov and the following year staged Uncle Vanya, which Chekhov had completed in 1896.[73] In the last decades of his life he became an atheist.[74][75][76]

Yalta[edit]

In March 1897, Chekhov suffered a major haemorrhage of the lungs while on a visit to Moscow. With great difficulty he was persuaded to enter a clinic, where doctors diagnosed tuberculosis on the upper part of his lungs and ordered a change in his manner of life.[77]

After his father’s death in 1898, Chekhov bought a plot of land on the outskirts of Yalta and built a villa (The White Dacha), into which he moved with his mother and sister the following year. Though he planted trees and flowers, kept dogs and tame cranes, and received guests such as Leo Tolstoy and Maxim Gorky, Chekhov was always relieved to leave his «hot Siberia» for Moscow or travels abroad. He vowed to move to Taganrog as soon as a water supply was installed there.[78][79] In Yalta he completed two more plays for the Art Theatre, composing with greater difficulty than in the days when he «wrote serenely, the way I eat pancakes now». He took a year each over Three Sisters and The Cherry Orchard.[80]

On 25 May 1901, Chekhov married Olga Knipper quietly, owing to his horror of weddings. She was a former protégée and sometime lover of Nemirovich-Danchenko whom he had first met at rehearsals for The Seagull.[81][82][83] Up to that point, Chekhov, known as «Russia’s most elusive literary bachelor»,[84] had preferred passing liaisons and visits to brothels over commitment.[85] He had once written to Suvorin:

By all means I will be married if you wish it. But on these conditions: everything must be as it has been hitherto—that is, she must live in Moscow while I live in the country, and I will come and see her…. I promise to be an excellent husband, but give me a wife who, like the moon, won’t appear in my sky every day.[86]

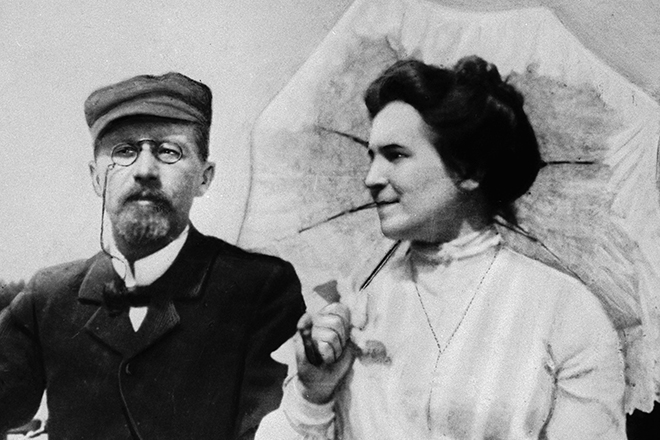

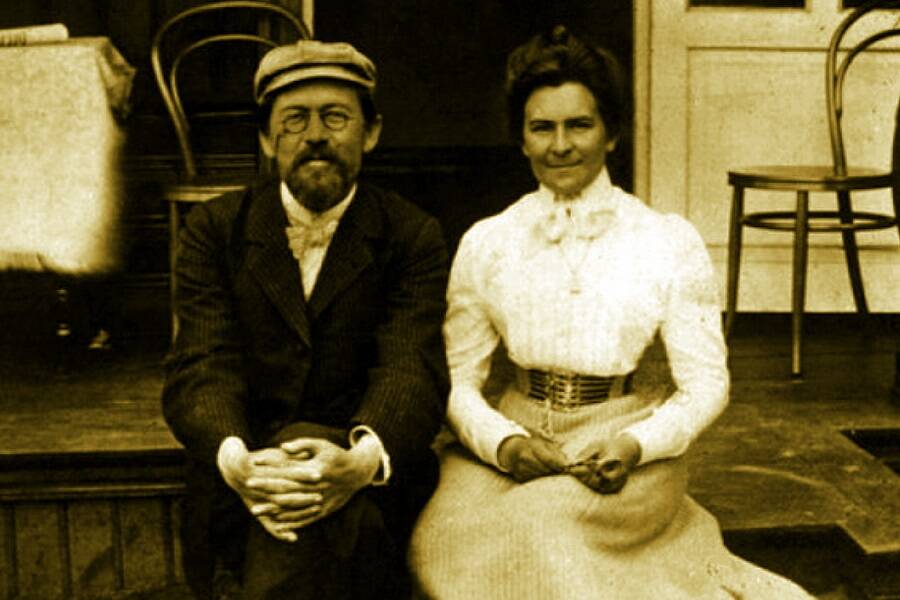

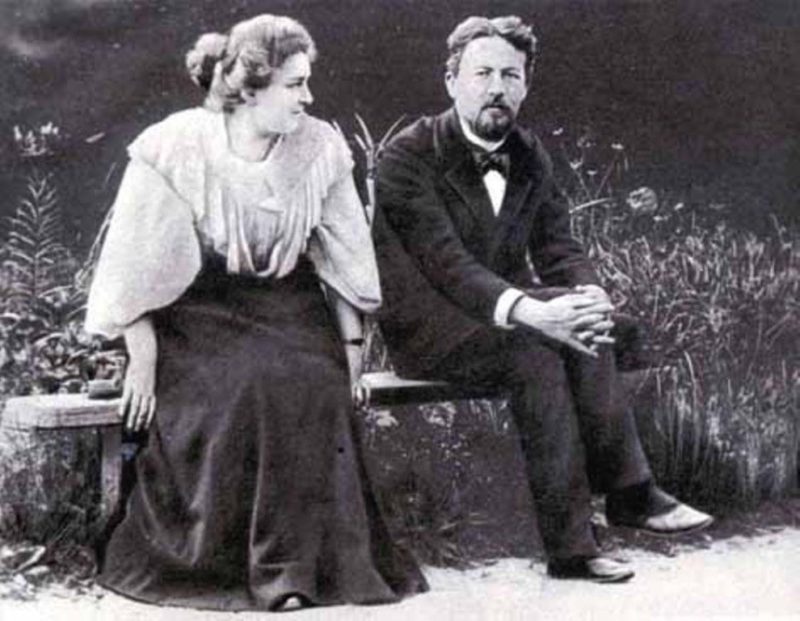

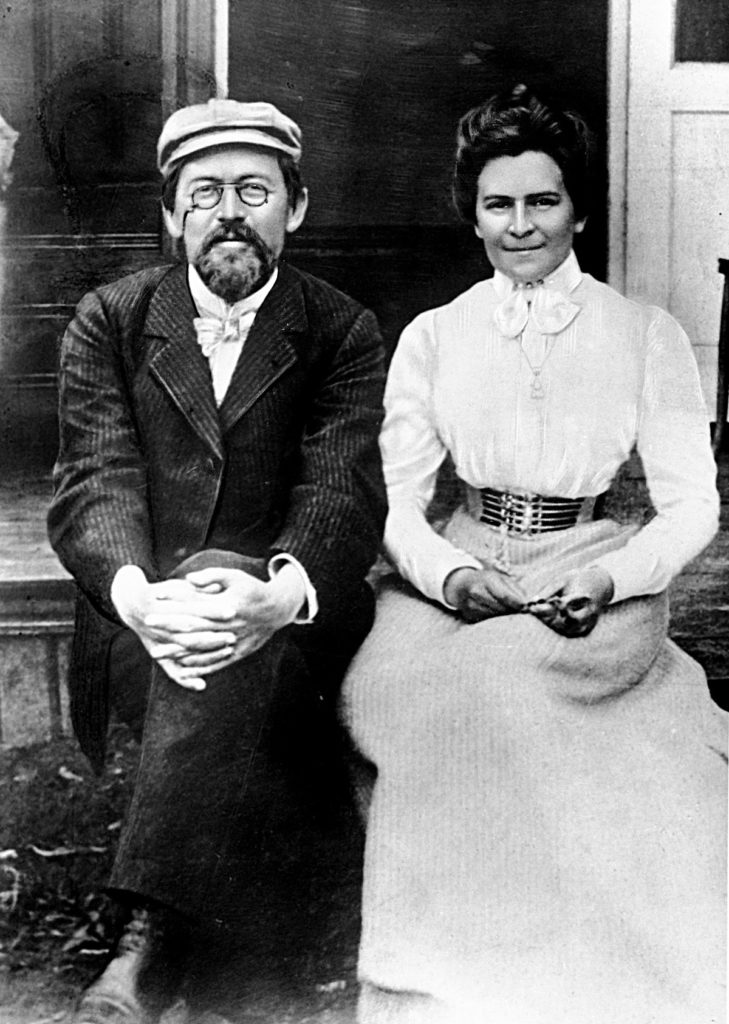

Chekhov and Olga, 1901, on their honeymoon

The letter proved prophetic of Chekhov’s marital arrangements with Olga: he lived largely at Yalta, she in Moscow, pursuing her acting career. In 1902, Olga suffered a miscarriage; and Donald Rayfield has offered evidence, based on the couple’s letters, that conception occurred when Chekhov and Olga were apart, although other Russian scholars have rejected that claim.[87][88] The literary legacy of this long-distance marriage is a correspondence that preserves gems of theatre history, including shared complaints about Stanislavski’s directing methods and Chekhov’s advice to Olga about performing in his plays.[89]

In Yalta, Chekhov wrote one of his most famous stories,[90] «The Lady with the Dog»[91] (also translated from the Russian as «Lady with Lapdog»),[92] which depicts what at first seems a casual liaison between a cynical married man and an unhappy married woman who meet while holidaying in Yalta. Neither expects anything lasting from the encounter. Unexpectedly though, they gradually fall deeply in love and end up risking scandal and the security of their family lives. The story masterfully captures their feelings for each other, the inner transformation undergone by the disillusioned male protagonist as a result of falling deeply in love, and their inability to resolve the matter by either letting go of their families or of each other.[93]

Death[edit]

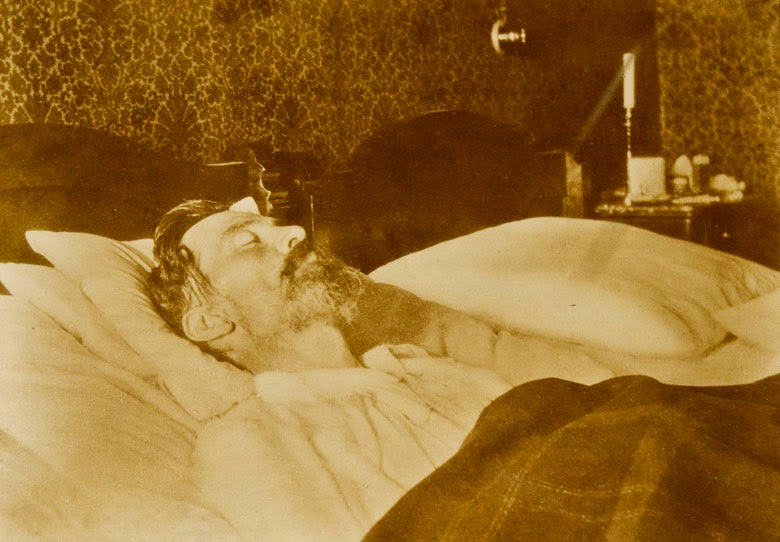

In May 1903 Chekhov visited Moscow; the prominent lawyer Vasily Maklakov visited him almost every day. Maklakov signed Chekhov’s will. By May 1904 Chekhov was terminally ill with tuberculosis. Mikhail Chekhov recalled that «everyone who saw him secretly thought the end was not far off, but the nearer [he] was to the end, the less he seemed to realise it».[17] On 3 June he set off with Olga for the German spa town of Badenweiler in the Black Forest in Germany, from where he wrote outwardly jovial letters to his sister Masha, describing the food and surroundings, and assuring her and his mother that he was getting better. In his last letter he complained about the way German women dressed.[94] Chekhov died on 15 July 1904 at the age of 44 after a long fight with tuberculosis, the same disease that killed his brother.[95]

Chekhov’s death has become one of «the great set pieces of literary history»[96]—retold, embroidered, and fictionalized many times since, notably in the 1987 short story «Errand» by Raymond Carver. In 1908 Olga wrote this account of her husband’s last moments:

Anton sat up unusually straight and said loudly and clearly (although he knew almost no German): Ich sterbe (‘I’m dying’). The doctor calmed him, took a syringe, gave him an injection of camphor, and ordered champagne. Anton took a full glass, examined it, smiled at me and said: ‘It’s a long time since I drank champagne.’ He drained it and lay quietly on his left side, and I just had time to run to him and lean across the bed and call to him, but he had stopped breathing and was sleeping peacefully as a child …[97]

Chekhov’s body was transported to Moscow in a refrigerated railway-car meant for oysters, a detail that offended Gorky.[98] Some of the thousands of mourners followed the funeral procession of a General Keller by mistake, to the accompaniment of a military band.[99] Chekhov was buried next to his father at the Novodevichy Cemetery.[100][101]

Legacy[edit]

A few months before he died, Chekhov told the writer Ivan Bunin that he thought people might go on reading his writings for seven years. «Why seven?», asked Bunin. «Well, seven and a half», Chekhov replied. «That’s not bad. I’ve got six years to live.»[102]

Chekhov’s posthumous reputation greatly exceeded his expectations. The ovations for the play The Cherry Orchard in the year of his death served to demonstrate the Russian public’s acclaim for the writer, which placed him second in literary celebrity only to Tolstoy, who outlived him by six years. Tolstoy was an early admirer of Chekhov’s short stories and had a series that he deemed «first quality» and «second quality» bound into a book. In the first category were: Children, The Chorus Girl, A Play, Home, Misery, The Runaway, In Court, Vanka, Ladies, A Malefactor, The Boys, Darkness, Sleepy, The Helpmate, and The Darling; in the second: A Transgression, Sorrow, The Witch, Verochka, In a Strange Land, The Cook’s Wedding, A Tedious Business, An Upheaval, Oh! The Public!, The Mask, A Woman’s Luck, Nerves, The Wedding, A Defenceless Creature, and Peasant Wives.[103]

Chekhov’s work also found praise from several of Russia’s most influential radical political thinkers. If anyone doubted the gloom and miserable poverty of Russia in the 1880s, the anarchist theorist Peter Kropotkin responded, «read only Chekhov’s novels!»[104] Raymond Tallis further recounts that Vladimir Lenin believed his reading of the short story Ward No. 6 «made him a revolutionary».[105] Upon finishing the story, Lenin is said to have remarked: «I absolutely had the feeling that I was shut up in Ward 6 myself!»[106]

In Chekhov’s lifetime, British and Irish critics generally did not find his work pleasing; E. J. Dillon thought «the effect on the reader of Chekhov’s tales was repulsion at the gallery of human waste represented by his fickle, spineless, drifting people» and R. E. C. Long said «Chekhov’s characters were repugnant, and that Chekhov revelled in stripping the last rags of dignity from the human soul».[107] After his death, Chekhov was reappraised. Constance Garnett’s translations won him an English-language readership and the admiration of writers such as James Joyce, Virginia Woolf, and Katherine Mansfield, whose story «The Child Who Was Tired» is similar to Chekhov’s «Sleepy».[108] The Russian critic D. S. Mirsky, who lived in England, explained Chekhov’s popularity in that country by his «unusually complete rejection of what we may call the heroic values».[109] In Russia itself, Chekhov’s drama fell out of fashion after the revolution, but it was later incorporated into the Soviet canon. The character of Lopakhin, for example, was reinvented as a hero of the new order, rising from a modest background so as eventually to possess the gentry’s estates.[110][111]

Despite Chekhov’s reputation as a playwright, William Boyd asserts that his short stories represent the greater achievement.[112] Raymond Carver, who wrote the short story «Errand» about Chekhov’s death, believed that Chekhov was the greatest of all short story writers:

Chekhov’s stories are as wonderful (and necessary) now as when they first appeared. It is not only the immense number of stories he wrote—for few, if any, writers have ever done more—it is the awesome frequency with which he produced masterpieces, stories that shrive us as well as delight and move us, that lay bare our emotions in ways only true art can accomplish.[113]

Style[edit]

One of the first non-Russians to praise Chekhov’s plays was George Bernard Shaw, who subtitled his Heartbreak House «A Fantasia in the Russian Manner on English Themes», and pointed out similarities between the predicament of the British landed class and that of their Russian counterparts as depicted by Chekhov: «the same nice people, the same utter futility».[114]

Ernest Hemingway, another writer influenced by Chekhov, was more grudging: «Chekhov wrote about six good stories. But he was an amateur writer.»[115] And Vladimir Nabokov criticised Chekhov’s «medley of dreadful prosaisms, ready-made epithets, repetitions».[116][117] But he also declared “yet it is his works which I would take on a trip to another planet”[118] and called «The Lady with the Dog» «one of the greatest stories ever written» in its depiction of a problematic relationship, and described Chekhov as writing «the way one person relates to another the most important things in his life, slowly and yet without a break, in a slightly subdued voice».[119]

For the writer William Boyd, Chekhov’s historical accomplishment was to abandon what William Gerhardie called the «event plot» for something more «blurred, interrupted, mauled or otherwise tampered with by life».[120]

Virginia Woolf mused on the unique quality of a Chekhov story in The Common Reader (1925):

But is it the end, we ask? We have rather the feeling that we have overrun our signals; or it is as if a tune had stopped short without the expected chords to close it. These stories are inconclusive, we say, and proceed to frame a criticism based upon the assumption that stories ought to conclude in a way that we recognise. In so doing we raise the question of our own fitness as readers. Where the tune is familiar and the end emphatic—lovers united, villains discomfited, intrigues exposed—as it is in most Victorian fiction, we can scarcely go wrong, but where the tune is unfamiliar and the end a note of interrogation or merely the information that they went on talking, as it is in Tchekov, we need a very daring and alert sense of literature to make us hear the tune, and in particular those last notes which complete the harmony.[121]

Michael Goldman has said of the elusive quality of Chekhov’s comedies: «Having learned that Chekhov is comic … Chekhov is comic in a very special, paradoxical way. His plays depend, as comedy does, on the vitality of the actors to make pleasurable what would otherwise be painfully awkward—inappropriate speeches, missed connections, faux pas, stumbles, childishness—but as part of a deeper pathos; the stumbles are not pratfalls but an energized, graceful dissolution of purpose.»[122]

Influence on dramatic arts[edit]

In the United States, Chekhov’s reputation began its rise slightly later, partly through the influence of Stanislavski’s system of acting, with its notion of subtext: «Chekhov often expressed his thought not in speeches», wrote Stanislavski, «but in pauses or between the lines or in replies consisting of a single word … the characters often feel and think things not expressed in the lines they speak.»[123][124] The Group Theatre, in particular, developed the subtextual approach to drama, influencing generations of American playwrights, screenwriters, and actors, including Clifford Odets, Elia Kazan and, in particular, Lee Strasberg. In turn, Strasberg’s Actors Studio and the «Method» acting approach influenced many actors, including Marlon Brando and Robert De Niro, though by then the Chekhov tradition may have been distorted by a preoccupation with realism.[125] In 1981, the playwright Tennessee Williams adapted The Seagull as The Notebook of Trigorin. One of Anton’s nephews, Michael Chekhov, would also contribute heavily to modern theatre, particularly through his unique acting methods which developed Stanislavski’s ideas further.

Alan Twigg, the chief editor and publisher of the Canadian book review magazine B.C. BookWorld wrote:

One can argue Anton Chekhov is the second-most popular writer on the planet. Only Shakespeare outranks Chekhov in terms of movie adaptations of their work, according to the movie database IMDb. … We generally know less about Chekhov than we know about mysterious Shakespeare.[126]

Chekhov has also influenced the work of Japanese playwrights including Shimizu Kunio, Yōji Sakate, and Ai Nagai. Critics have noted similarities in how Chekhov and Shimizu use a mixture of light humour as well as an intense depictions of longing.[127] Sakate adapted several of Chekhov’s plays and transformed them in the general style of nō.[128] Nagai also adapted Chekhov’s plays, including Three Sisters, and transformed his dramatic style into Nagai’s style of satirical realism while emphasising the social issues depicted in the play.[128]

Chekhov’s works have been adapted for the screen, including Sidney Lumet’s Sea Gull and Louis Malle’s Vanya on 42nd Street. Laurence Olivier’s final effort as a film director was a 1970 adaptation of Three Sisters in which he also played a supporting role. His work has also served as inspiration or been referenced in numerous films. In Andrei Tarkovsky’s 1975 film The Mirror, characters discuss his short story «Ward No. 6». Woody Allen has been influenced by Chekhov and references to his works are present in many of his films including Love and Death (1975), Interiors (1978) and Hannah and Her Sisters (1986). Plays by Chekhov are also referenced in François Truffaut’s 1980 drama film The Last Metro, which is set in a theatre. The Cherry Orchard has a role in the comedy film Henry’s Crime (2011). A portion of a stage production of Three Sisters appears in the 2014 drama film Still Alice. The 2022 Foreign Language Oscar winner, Drive My Car, is centered on a production of Uncle Vanya.

Several of Chekhov’s short stories were adapted as episodes of the 1986 Indian anthology television series Katha Sagar. Another Indian television series titled Chekhov Ki Duniya aired on DD National in the 1990s, adapting different works of Chekhov.[129]

Nuri Bilge Ceylan’s Palme d’Or winner Winter Sleep was adapted from the short story «The Wife» by Anton Chekhov.[130]

Publications[edit]

See also[edit]

- Chekhov Library

- Chekhov Monument in Rostov-on-Don

- Maria Chekhova

- Ann Dunnigan, English-language translator

- Jean-Claude van Itallie, English-language translator

Explanatory notes[edit]

- ^ In Chekhov’s day, his name was written Антонъ Павловичъ Чеховъ. See, for instance, Антонъ Павловичъ Чеховъ. 1898. Мужики и Моя жизнь.

- ^ Old Style date 17 January.

- ^ Old Style date 2 July.

Citations[edit]

- ^ Letter to G. I. Rossolimo, 11 October 1899. Letters of Anton Chekhov

- ^ Rayfield 1997, p. 595.

- ^ a b c Hingley, Ronald Francis (25 January 2022). «Anton Chekhov – Biography, Plays, Short Stories, & Facts». Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 26 April 2022.

- ^ «Greatest short story writer who ever lived.» Raymond Carver (in Rosamund Bartlett’s introduction to About Love and Other Stories, XX); «Quite probably. the best short-story writer ever.» A Chekhov Lexicon, by William Boyd, The Guardian, 3 July 2004. Retrieved 16 February 2007.

- ^ «Stories … which are among the supreme achievements in prose narrative.» Vodka miniatures, belching and angry cats, George Steiner’s review of The Undiscovered Chekhov, in The Observer, 13 May 2001. Retrieved 16 February 2007.

- ^ Harold Bloom, Genius: A Study of One Hundred Exemplary Authors.

- ^ Letter to Alexei Suvorin, 11 September 1888. Letters of Anton Chekhov. On Wikiquote.

- ^ «Actors climb up Chekhov like a mountain, roped together, sharing the glory if they ever make it to the summit». Actor Ian McKellen, quoted in Miles, 9.

- ^ «Chekhov’s art demands a theatre of mood.» Vsevolod Meyerhold, quoted in Allen, 13; «A richer submerged life in the text is characteristic of a more profound drama of realism, one which depends less on the externals of presentation.» Styan, 84.

- ^ «Chekhov is said to be the father of the modern short story». Malcolm 2004, p. 87; «He brought something new into literature.» James Joyce, in Arthur Power, Conversations with James Joyce, Usborne Publishing Ltd, 1974, ISBN 978-0-86000-006-8, 57; «Tchehov’s breach with the classical tradition is the most significant event in modern literature», John Middleton Murry, in Athenaeum, 8 April 1922, cited in Bartlett’s introduction to About Love.

- ^ «You are right in demanding that an artist should take an intelligent attitude to his work, but you confuse two things: solving a problem and stating a problem correctly. It is only the second that is obligatory for the artist.» Letter to Suvorin, 27 October 1888. Letters of Anton Chekhov.

- ^ Rayfield 1997, pp. 3–4: Egor Mikhailovich Chekhov and Efrosinia Emelianovna

- ^ Wood 2000, p. 78

- ^ Payne 1991, p. XVII.

- ^ Simmons 1970, p. 18.

- ^ Chekhov and Taganrog, Taganrog city website.

- ^ a b c d e f From the biographical sketch, adapted from a memoir by Chekhov’s brother Mihail, which prefaces Constance Garnett’s translation of Chekhov’s letters, 1920.

- ^ Letter to brother Alexander, 2 January 1889, in Malcolm 2004, p. 102.

- ^ Another insight into Chekhov’s childhood came in a letter to his publisher and friend Alexei Suvorin: «From my childhood I have believed in progress, and I could not help believing in it since the difference between the time when I used to be thrashed and when they gave up thrashing me was tremendous.» Letter to Suvorin, 27 March 1894. Letters of Anton Chekhov.

- ^ Bartlett, pp. 4–5.

- ^ Letter to I.L. Shcheglov, 9 March 1892. Letters of Anton Chekhov.

- ^ Rayfield 1997, p. 31.

- ^ Letter to cousin Mihail, 10 May 1877. Letters of Anton Chekhov.

- ^ Malcolm 2004, p. 25.

- ^ a b Payne 1991, p. XX.

- ^ Letter to brother Mihail, 1 July 1876. Letters of Anton Chekhov.

- ^ Simmons 1970, p. 26.

- ^ Simmons 1970, p. 33.

- ^ Rayfield 1997, p. 69.

- ^ Wood 2000, p. 79.

- ^ Rayfield 1997, p. 91.

- ^ «There is in these miniatures an arresting potion of cruelty … The wonderfully compassionate Chekhov was yet to mature.» «Vodka Miniatures, Belching and Angry Cats», George Steiner’s review of The Undiscovered Chekhov in The Observer, 13 May 2001. Retrieved 16 February 2007.

- ^ Willis, Louis (27 January 2013). «Chekhov’s Crime Stories». Literary and Genre. Knoxville: SleuthSayers.

- ^ Malcolm 2004, p. 26.

- ^ Letter to N.A.Leykin, 6 April 1886. Letters of Anton Chekhov.

- ^ Rayfield 1997, p. 128.

- ^ Rayfield 1997, pp. 448–450: They only ever fell out once, when Chekhov objected to the anti-Semitic attacks in New Times against Dreyfus and Zola in 1898.

- ^ In many ways, the right-wing Suvorin, whom Lenin later called «The running dog of the Tzar» (Payne, XXXV), was Chekhov’s opposite; «Chekhov had to function like Suvorin’s kidney, extracting the businessman’s poisons.»Wood 2000, p. 79

- ^ The Huntsman.. Retrieved 16 February 2007.

- ^ Malcolm 2004, pp. 32–33.

- ^ Payne 1991, p. XXIV.

- ^ Simmons 1970, p. 160.

- ^ «There is a scent of the steppe and one hears the birds sing. I see my old friends the ravens flying over the steppe.» Letter to sister Masha, 2 April 1887. Letters of Anton Chekhov.

- ^ Letter to Grigorovich, 12 January 1888. Quoted by Malcolm 2004, p. 137.

- ^ «‘The Steppe,’ as Michael Finke suggests, is ‘a sort of dictionary of Chekhov’s poetics,’ a kind of sample case of the concealed literary weapons Chekhov would deploy in his work to come.» Malcolm 2004, p. 147.

- ^ From the biographical sketch, adapted from a memoir by Chekhov’s brother Mikhail, which prefaces Constance Garnett’s translation of Chekhov’s letters, 1920.

- ^ Letter to brother Alexander, 20 November 1887. Letters of Anton Chekhov.

- ^ Petr Mikhaĭlovich Bit︠s︡illi (1983), Chekhov’s Art: A Stylistic Analysis, Ardis, p. x

- ^ Daniel S. Burt (2008), The Literature 100: A Ranking of the Most Influential Novelists, Playwrights, and Poets of All Time, Infobase Publishing

- ^ a b Valentine T. Bill (1987), Chekhov: The Silent Voice of Freedom, Philosophical Library

- ^ S. Shchukin, Memoirs (1911)

- ^ «A Dreary Story.». Retrieved 16 February 2007.

- ^ Simmons 1970, pp. 186–191.

- ^ Malcolm 2004, p. 129.

- ^ Simmons 1970, p. 223.

- ^ Rayfield 1997, p. 224.

- ^ Letter to sister, Masha, 20 May 1890. Letters of Anton Chekhov.

- ^ Wood 2000, p. 85.

- ^ Rayfield 1997, p. 230.

- ^ Letter to A.F.Koni, 16 January 1891. Letters of Anton Chekhov.

- ^ Malcolm 2004, p. 125.

- ^ Simmons 1970, p. 229: Such is the general critical view of the work, but Simmons calls it a «valuable and intensely human document.»

- ^ «The Murder». Retrieved 16 February 2007.

- ^ Murakami, Haruki. 1Q84. Alfred A. Knopf: New York, 2011.

- ^ Heaney, Seamus. Station Island Farrar Straus Giroux: New York, 1985.

- ^ Gould, Rebecca Ruth (2018). «The aesthetic terrain of settler colonialism: Katherine Mansfield and Anton Chekhov’s natives». Journal of Postcolonial Writing. 55: 48–65. doi:10.1080/17449855.2018.1511242. S2CID 165401623.

- ^ From the biographical sketch, adapted from a memoir by Chekhov’s brother Mikhail, which prefaces Constance Garnett’s translation of Chekhov’s letters, 1920.

- ^ From the biographical sketch, adapted from a memoir by Chekhov’s brother Mihail, which prefaces Constance Garnett’s translation of Chekhov’s letters, 1920.

- ^ Note-Book.. Retrieved 16 February 2007.

- ^ Rayfield 1997, pp. 394–398.

- ^ Benedetti, Stanislavski: An Introduction, 25.

- ^ Chekhov and the Art Theatre, in Stanislavski’s words, were united in a common desire «to achieve artistic simplicity and truth on the stage.» Allen, 11.

- ^ Rayfield 1997, pp. 390–391: Rayfield draws from his critical study Chekhov’s «Uncle Vanya» and the «Wood Demon» (1995), which anatomised the evolution of the Wood Demon into Uncle Vanya—»one of Chekhov’s most furtive achievements.»

- ^ Tabachnikova, Olga (2010). Anton Chekhov Through the Eyes of Russian Thinkers: Vasilii Rozanov, Dmitrii Merezhkovskii and Lev Shestov. Anthem Press. p. 26. ISBN 978-1-84331-841-5.

For Rozanov, Chekhov represents a concluding stage of classical Russian literature at the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries, caused by the fading of the thousand-year-old Christian tradition that had sustained much of this literature. On the one hand, Rozanov regards Chekhov’s positivism and atheism as his shortcomings, naming them among the reasons for Chekhov’s popularity in society.

- ^ Chekhov, Anton Pavlovich (1997). Karlinsky, Simon; Heim, Michael Henry (eds.). Anton Chekhov’s Life and Thought: Selected Letters and Commentary. Northwestern University Press. p. 13. ISBN 978-0-8101-1460-9.

While Anton did not turn into the kind of militant atheist that his older brother Alexander eventually became, there is no doubt that he was a non-believer in the last decades of his life.

- ^ Richard Pevear (2009). Selected Stories of Anton Chekhov. Random House Digital, Inc. pp. xxii. ISBN 978-0-307-56828-1.

According to Leonid Grossman, ‘In his revelation of those evangelical elements, the atheist Chekhov is unquestionably one of the most Christian poets of world literature.’

- ^ Letter to Suvorin, 1 April 1897. Letters of Anton Chekhov.

- ^ Olga Knipper, «Memoir», in Benedetti, Dear Writer, Dear Actress, 37, 270.

- ^ Bartlett, 2.

- ^ Malcolm 2004, pp. 170–171.

- ^ «I have a horror of weddings, the congratulations and the champagne, standing around, glass in hand with an endless grin on your face.» Letter to Olga Knipper, 19 April 1901.

- ^ Benedetti, Dear Writer, Dear Actress, 125.

- ^ Rayfield 1997, p. 500″Olga’s relations with Vladimir Nemirovich-Danchenko were more than professional.»

- ^ Harvey Pitcher in Chekhov’s Leading Lady, quoted in Malcolm 2004, p. 59.

- ^ «Chekhov had the temperament of a philanderer. Sexually, he preferred brothels or swift liaisons.»Wood 2000, p. 78

- ^ Letter to Suvorin, 23 March 1895. Letters of Anton Chekhov.

- ^ Rayfield 1997, pp. 556–557Rayfield also tentatively suggests, drawing on obstetric clues, that Olga suffered an ectopic pregnancy rather than a miscarriage.

- ^ There was certainly tension between the couple after the miscarriage, though Simmons 1970, p. 569, and Benedetti, Dear Writer, Dear Actress, 241, put this down to Chekhov’s mother and sister blaming the miscarriage on Olga’s late-night socialising with her actor friends.

- ^ Benedetti, Dear Writer, Dear Actress: The Love Letters of Olga Knipper and Anton Chekhov.

- ^ Chekhov, Anton. «Lady with lapdog». Short Stories.

- ^ Rosamund, Bartlett (2 February 2010). «The House That Chekhov Built». London Evening Standard. p. 31.

- ^ Greenberg, Yael. «The Presentation of the Unconscious in Chekhov’s Lady With Lapdog.» Modern Language Review 86.1 (1991): 126–130. Academic Search Premier. Web. 3 November 2011.

- ^ «Overview: ‘The Lady with the Dog’.» Characters in 20th-Century Literature. Laurie Lanzen Harris. Detroit: Gale Research, 1990. Literature Resource Center. Web. 3 November 2011.

- ^ Letter to sister Masha, 28 June 1904. Letters of Anton Chekhov.

- ^ «Anton Chekhov | Biography, Plays, Short Stories, & Facts | Britannica».

- ^ Malcolm 2004, p. 62.

- ^ Olga Knipper, Memoir, in Benedetti, Dear Writer, Dear Actress, 284.

- ^ «Banality revenged itself upon him by a nasty prank, for it saw that his corpse, the corpse of a poet, was put into a railway truck ‘For the Conveyance of Oysters’.» Maxim Gorky in Reminiscences of Anton Chekhov.. Retrieved 16 February 2007.

- ^ Chekhov’s Funeral. M. Marcus.The Antioch Review, 1995

- ^ Malcolm 2004, p. 91; Alexander Kuprin in Reminiscences of Anton Chekhov. Retrieved 16 February 2007.

- ^ «Novodevichy Cemetery». Passport Magazine. April 2008. Retrieved 12 September 2013.

- ^ Payne 1991, p. XXXVI.

- ^ Simmons 1970, p. 595.

- ^ Peter Kropotkin (1 January 1905). «The Constitutional Movement in Russia». revoltlib.com. The Nineteenth Century.

- ^ Raymond Tallis (3 September 2014). In Defence of Wonder and Other Philosophical Reflections. Routledge. ISBN 9781317547402.

- ^ Edmund Wilson (1940). «To The Finland Station». archive.org. Doubleday.

When Vladimir finished reading this story, he was seized with such a horror that he could not bear to stay in his room. He went out to find someone to talk to, but it was late: they had all gone to bed. ‘I absolutely had the feeling,’ he told his sister next day,’that I was shut up in Ward 6 myself!’

- ^ Meister, Charles W. (1953). «Chekhov’s Reception in England and America». American Slavic and East European Review. 12 (1): 109–121. doi:10.2307/3004259. JSTOR 3004259.

- ^ William H. New (1999). Reading Mansfield and Metaphors of Reform. McGill-Queen’s Press. pp. 15–17. ISBN 978-0-7735-1791-2.

- ^ Wood 2000, p. 77.

- ^ Allen, 88.

- ^ «They won’t allow a play which is seen to lament the lost estates of the gentry.» Letter of Vladimir Nemirovich-Danchenko, quoted by Anatoly Smeliansky in «Chekhov at the Moscow Art Theatre», from The Cambridge Companion to Chekhov, 31–32.

- ^ «The plays lack the seamless authority of the fiction: there are great characters, wonderful scenes, tremendous passages, moments of acute melancholy and sagacity, but the parts appear greater than the whole.» A Chekhov Lexicon, by William Boyd, The Guardian, 3 July 2004. Retrieved 16 February 2007.

- ^ Bartlett, «From Russia, with Love», The Guardian, 15 July 2004. Retrieved 17 February 2007.

- ^ Anna Obraztsova in «Bernard Shaw’s Dialogue with Chekhov», from Miles, 43–44.

- ^ Letter from Ernest Hemingway to Archibald MacLeish, 1925 (from Selected Letters, p. 179), in Ernest Hemingway on Writing, Ed Larry W. Phillips, Touchstone, (1984) 1999, ISBN 978-0-684-18119-6, 101.

- ^ Wood 2000, p. 82.

- ^ Wikiquote quotes about Chekhov

- ^ Karlinsky, Simon (13 June 2008). «Nabokov and Chekhov: Affinities, parallels, structures». Cycno. 10 (n°1 NABOKOV : Autobiography, Biography and Fiction). Retrieved 10 September 2018.

- ^ From Vladimir Nabokov’s Lectures on Russian Literature, quoted by Francine Prose in Learning from Chekhov, 231.

- ^ «For the first time in literature the fluidity and randomness of life was made the form of the fiction. Before Chekhov, the event-plot drove all fictions.» William Boyd, referring to the novelist William Gerhardie’s analysis in Anton Chekhov: A Critical Study, 1923. «A Chekhov Lexicon» by William Boyd, The Guardian, 3 July 2004. Retrieved 16 February 2007.

- ^ Woolf, Virginia, The Common Reader: First Series, Annotated Edition, Harvest/HBJ Book, 2002, ISBN 0-15-602778-X, 172.

- ^ Michael Goldman, The Actor’s Freedom: Towards a Theory of Drama, p72.

- ^ Reynolds, Elizabeth (ed), Stanislavski’s Legacy, Theatre Arts Books, 1987, ISBN 978-0-87830-127-0, 81, 83.

- ^ «It was Chekhov who first deliberately wrote dialogue in which the mainstream of emotional action ran underneath the surface. It was he who articulated the notion that human beings hardly ever speak in explicit terms among each other about their deepest emotions, that the great, tragic, climactic moments are often happening beneath outwardly trivial conversation.» Martin Esslin, from Text and Subtext in Shavian Drama, in 1922: Shaw and the last Hundred Years, ed. Bernard. F. Dukore, Penn State Press, 1994, ISBN 978-0-271-01324-4, 200.

- ^ «Lee Strasberg became in my opinion a victim of the traditional idea of Chekhovian theatre … [he left] no room for Chekhov’s imagery.» Georgii Tostonogov on Strasberg’s production of Three Sisters in The Drama Review (winter 1968), quoted by Styan, 121.

- ^ Sekirin, Peter (2011). Memories of Chekhov: Accounts of the Writer from His Family, Friends and Contemporaries. Foreword by Alan Twigg. Jefferson, NC: MacFarland Publishers. p. 1. ISBN 978-0-7864-5871-4.

- ^ Rimer, J. (2001). Japanese Theatre and the International Stage. Leiden, The Netherlands: Koninklijke Brill NV. pp. 299–311. ISBN 978-90-04-12011-2.

- ^ a b Clayton, J. Douglas (2013). Adapting Chekhov: The Text and Its Mutations. Routledge. pp. 269–270. ISBN 978-0-415-50969-5.

- ^ «Chekhov Ki Duniya». nettv4u.

- ^ Diken, Bülent (1 September 2017). «Money, Religion, and Symbolic Exchange in Winter Sleep». Religion and Society. 8 (1): 94–108. doi:10.3167/arrs.2017.080106. ISSN 2150-9301.

General and cited sources[edit]

- Allen, David, Performing Chekhov, Routledge (UK), 2001, ISBN 978-0-415-18934-7

- Bartlett, Rosamund, and Anthony Phillips (translators), Chekhov: A Life in Letters, Penguin Books, 2004, ISBN 978-0-14-044922-8

- Bartlett, Rosamund, Chekhov: Scenes from a Life, Free Press, 2004, ISBN 978-0-7432-3074-2

- Benedetti, Jean (editor and translator), Dear Writer, Dear Actress: The Love Letters of Olga Knipper and Anton Chekhov, Methuen Publishing Ltd, 1998 edition, ISBN 978-0-413-72390-1

- Benedetti, Jean, Stanislavski: An Introduction, Methuen Drama, 1989 edition, ISBN 978-0-413-50030-4

- Borny, Geoffrey, Interpreting Chekhov, ANU Press, 2006, ISBN 1-920942-68-8, free download

- Chekhov, Anton, About Love and Other Stories, translated by Rosamund Bartlett, Oxford University Press, 2004, ISBN 978-0-19-280260-6

- Chekhov, Anton, The Undiscovered Chekhov: Fifty New Stories, translated by Peter Constantine, Duck Editions, 2001, ISBN 978-0-7156-3106-5

- Chekhov, Anton, Easter Week, translated by Michael Henry Heim, engravings by Barry Moser, Shackman Press, 2010

- Chekhov, Anton (1991). Forty Stories. Translated by Payne, Robert. New York City: Vintage Classics. ISBN 978-0-679-73375-1.

- Chekhov, Anton, Letters of Anton Chekhov to His Family and Friends with Biographical Sketch, translated by Constance Garnett, Macmillan, 1920. Full text at Gutenberg.. Retrieved 16 February 2007.

- Chekhov, Anton, Note-Book of Anton Chekhov, translated by S. S. Koteliansky and Leonard Woolf, B.W. Huebsch, 1921. Full text at Gutenberg.. Retrieved 16 February 2007.

- Chekhov, Anton, The Other Chekhov, edited by Okla Elliott and Kyle Minor, with story introductions by Pinckney Benedict, Fred Chappell, Christopher Coake, Paul Crenshaw, Dorothy Gambrell, Steven Gillis, Michelle Herman, Jeff Parker, Benjamin Percy, and David R. Slavitt. New American Press, 2008 edition, ISBN 978-0-9729679-8-3

- Chekhov, Anton, Seven Short Novels, translated by Barbara Makanowitzky, W. W. Norton & Company, 2003 edition, ISBN 978-0-393-00552-3

- Clyman, T. W. (Ed.). A Chekhov companion. Westport, Ct: Greenwood Press, (1985). ISBN 9780313234231

- Finke, Michael C., Chekhov’s ‘Steppe’: A Metapoetic Journey, an essay in Anton Chekhov Rediscovered, ed Savely Senderovich and Munir Sendich, Michigan Russian Language Journal, 1988, OCLC 17003357

- Finke, Michael C., Seeing Chekhov: Life and Art, Cornell UP, 2005, ISBN 978-0-8014-4315-2

- Gerhardie, William, Anton Chekhov, Macdonald, (1923) 1974 edition, ISBN 978-0-356-04609-9

- Gorky, Maksim, Alexander Kuprin, and I.A. Bunin, Reminiscences of Anton Chekhov, translated by S. S. Koteliansky and Leonard Woolf, B.W.Huebsch, 1921. Read at eldritchpress.. Retrieved 16 February 2007.

- Gottlieb, Vera, and Paul Allain (eds), The Cambridge Companion to Chekhov, Cambridge University Press, 2000, ISBN 978-0-521-58917-8

- Jackson, Robert Louis, Dostoevsky in Chekhov’s Garden of Eden – ‘Because of Little Apples’, in Dialogues with Dostoevsky, Stanford University Press, 1993, ISBN 978-0-8047-2120-2

- Klawans, Harold L., Chekhov’s Lie, 1997, ISBN 1-888799-12-9. About the challenges of combining writing with the medical life.

- Malcolm, Janet (2004) [2001]. Reading Chekhov, a Critical Journey. London: Granta Publications. ISBN 9781862076358. OCLC 224119811.

- Miles, Patrick (ed), Chekhov on the British Stage, Cambridge University Press, 1993, ISBN 978-0-521-38467-4

- Nabokov, Vladimir, Anton Chekhov, in Lectures on Russian Literature, Harvest/HBJ Books, [1981] 2002 edition, ISBN 978-0-15-602776-2.

- Pitcher, Harvey, Chekhov’s Leading Lady: Portrait of the Actress Olga Knipper, J Murray, 1979, ISBN 978-0-7195-3681-6

- Prose, Francine, Learning from Chekhov, in Writers on Writing, ed. Robert Pack and Jay Parini, UPNE, 1991, ISBN 978-0-87451-560-2

- Rayfield, Donald (1997). Anton Chekhov: A Life. London: HarperCollins. ISBN 9780805057478. OCLC 654644946, 229213309.

- Sekirin, Peter. «Memories of Chekhov: Accounts of the Writer from His Family, Friends and Contemporaries,» MacFarland Publishers, 2011, ISBN 978-0-7864-5871-4

- Simmons, Ernest Joseph (1970) [1962]. Chekhov: A Biography. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 9780226758053. OCLC 682992.

- Speirs, L. Tolstoy and Chekhov. Cambridge, England: University Press, (1971), ISBN 0521079500

- Stanislavski, Constantin, My Life in Art, Methuen Drama, 1980 edition, ISBN 978-0-413-46200-8

- Styan, John Louis, Modern Drama in Theory and Practice, Cambridge University Press, 1981, ISBN 978-0-521-29628-1

- Wood, James (2000) [1999]. «What Chekhov Meant by Life». The Broken Estate: Essays in Literature and Belief. New York, NY: Modern Library. ISBN 9780804151900. OCLC 863217943.

- Zeiger, Arthur, The Plays of Anton Chekhov, Claxton House, Inc., New York, NY, 1945.

- Tufarulo, G, M., La Luna è morta e lo specchio infranto. Miti letterari del Novecento, vol.1 – G. Laterza, Bari, 2009– ISBN 978-88-8231-491-0.

External links[edit]

This audio file was created from a revision of this article dated 26 July 2012, and does not reflect subsequent edits.

- Biographical

- Petri Liukkonen. «Anton Chekhov». Books and Writers

- Biography at The Literature Network

- «Chekhov’s Legacy» by Cornel West at NPR, 2004

- The International competition of philological, culture and film studies works dedicated to Anton Chekhov’s life and creative work (in Russian)

- Documentary

- 2010: Tschechow lieben (Tschechow and Women) – Director: Marina Rumjanzewa – Language: German

- Works

- Works by Anton Chekhov in eBook form at Standard Ebooks

- Works by Anton Pavlovich Chekhov at Project Gutenberg. All Constance Garnett’s translations of the short stories and letters are available, plus the edition of the Note-book translated by S. S. Koteliansky and Leonard Woolf – see the «References» section for print publication details of all of these. Site also has translations of all the plays.

- Works by or about Anton Chekhov at Internet Archive

- Works by Anton Chekhov at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- 201 Stories by Anton Chekhov, translated by Constance Garnett presented in chronological order of Russian publication with annotations.

- Антон Павлович Чехов. Указатель Texts of Chekhov’s works in the original Russian, listed in chronological order, and also alphabetically by title. Retrieved June 2013. (in Russian)

- Антон Павлович Чехов Texts of Chekhov’s works in the original Russian. Retrieved 16 February 2007. (in Russian)

- Works by Anton Chekhov at Open Library

Anton Chekhov: biography

Anton Pavlovich Chekhov is the classic of the world literature, writer, playwright, doctor by training, academician of the Russian Academy of Sciences.

Anton Chekhov was born in Taganrog in January 1860. His father was a grocer who held a small colonial products store. Anton had four brothers and two sisters one of which died in early childhood. Chekhov’s mother, a calm family-oriented woman, was a daughter of a merchant.

Chekhov went to the Taganrog grammar school when his father ran away from creditors to Moscow. The would-be writer stayed in the hometown to complete his education. He lived with the new owners of the house and paid for his living by tutoring.

In his school years, Chekhov acquired his worldview and developed the love of books and theater. At that time, he wrote several early humorous stories. Since 13, the boy was infatuated with theater and even took part in putting on home plays for his schoolmates.

Artworks

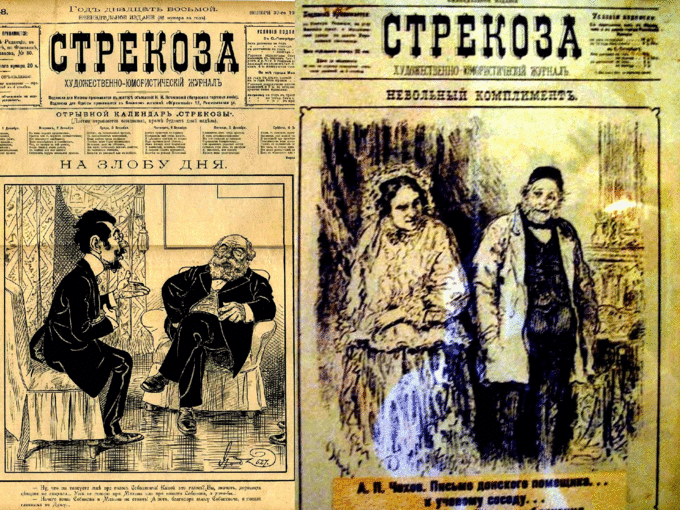

The first printed work by Anton Pavlovich appeared in 1880 in the magazine “Strekoza” (“Dragonfly”). Since then, Chekhov had been collaborating with the magazines “Budilnik” (“Alarm clock”), “Zritel” (“Viewer”), “Mirskoy Tolk” (“Mundane Talk”), “Svet i teni” (“Light and Shadows”). In the magazine “Oskolki” (“Fragments”), many Chekhov’s humorous stories appeared first: “Fat and Thin” 1883, “The Chameleon” 1884, “Overdoing it” 1885.

In 1886, in the periodical “Petersburg Gazeta” (“Petersburg Newspaper”), the Christmas story “Vanka” was published. The writer used the pseudonym “Antosha Chekhonte” in his first works.

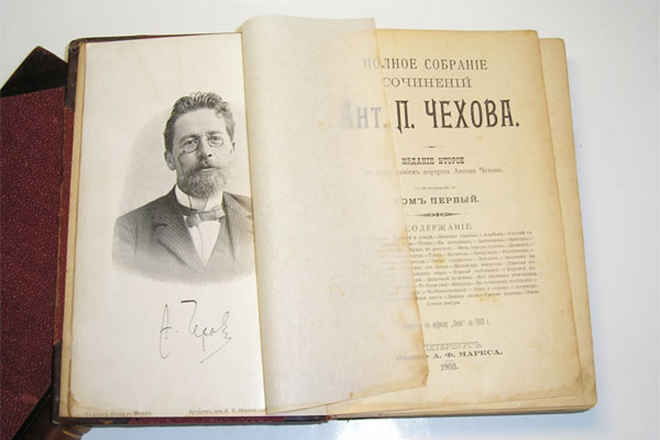

In 1886, Anton Pavlovich received a job offer from St. Petersburg from the newspaper “Novoye Vremya” (“The New Time”). At this period, the writer created the short story collections “Motley Stories” and “Innocent Conversations.” As his works gained popularity, Chekhov started signing them with his real name.

The premiere of the new play “Ivanov” was in 1887 in Moscow. The young playwright’s artwork was first staged in Korsh Theater. With varied public reactions, the play was a success. Later, the play was staged in St. Petersburg with some adjustments. In 1888, Anton Pavlovich was awarded the half Pushkin Prize for his short story collection “At Dusk.”

In 1888-1889, the Chekhovy spent summer in Kharkov Governorate not far from Sumy. The death of one of the brothers made the writer escape the place where he lived with his relatives. Anton Pavlovich was going to visit Europe, but fate led him to Odessa where Maly Theater was touring. The writer attracted to some young actress, yet this feeling faded away soon. Apathetic, Chekhov went to Yalta.

By 1889, the writer had created the novellas “Drama on the Hunt,” Steppe,” “Lights,” and “A Boring Story.” The material for these works was gathered by Chekhov during his journeys. The writer became interested in visiting different places at the end of the 1880s when he stopped cooperating with the humorous magazines.

The desire to travel urged Chekhov to go to Sakhalin in 1890. The way to the island laid through Siberia where the writer stocked up on the material for his future literary projects. Considering the health condition of the consumptive person, the road was challenging for him. At the end of the journey, Chekhov created the collection of essays “From Siberia” and the book “Island Sakhalin.”

For numerous Chekhov’s art admirers, the novella “Ward № 6” stands out among other works. It was first published in the magazine “Russkaya Mysl” (“Russian Thought”) in 1892. The title of the novella became denominative – it means something abnormal or crazy. Many phrases from this book have become popular quotes.

In 1892, the writer’s old dream came true: he bought a country estate in Melikhovo and started living there with his parents and sister Maria who became a faithful guardian angel for her brother. After the purchase of the estate, Chekhov’s life transformed. Again, he had the opportunity to practice medicine – except literature, Anton Pavlovich had another passion, surgery.

During the Melikhovo period, Chekhov worked as a zemski doctor, built several schools, a fire station for peasants, and a bell tower. The writer ensured the road to Lopasnya was built and the railway station had a post office. Besides, Chekhov planted elms, oaks, and larches in the less dense parts of the forest; he also planted more than a thousand cherry trees. At this time, Anton Pavlovich opened the public library in Taganrog at his own expense.

Many famous works by Chekhov, such as “The Seagull” and “Uncle Vanya,” were created in Melikhovo. The tuberculosis exacerbation made the writer to leave the country estate for the south. In 1898, the playwright spent the winter in Nice; having returned from France, he bought a piece of land in Yalta. In summer 1899, Chekhov sold the country estate in Melikhovo and finally moved to Crimea.

At this time, Anton Pavlovich met his future wife. Olga Knipper spent July 1900 at Chekhov’s summer house which determined their further relationship development. In 1900, the playwright created the play “Three Sisters” where his spouse played splendidly. As the leading actress, Olga Knipper was also a success when “The Cherry Orchard” was staged in 1903.

In 1904, the playwright died. The play “The Cherry Orchard” was the last work of the Russian classic.

Stage Plays and Movies

In 1969, the Soviet director Sergey Yutkevich created the movie about how the play “The Seagull” was made. The movie was named “A Plot for a Little Story.”

Using the facts from the writer’s biography, in 1991, Robert Long and Dmitry Frenkel created the musical “Chekhov” in the Netherlands.

Commissioned by the Moscow Government, the biographical drama “Farewell, doctor Chekhov!” telling the story of the playwright’s life was created in 2007.

In 2012, the movie about the relationship between Anton Pavlovich and Lydia Avilova was presented. “The Admirer” starred Oleg Tabakov and Kirill Pirogov, the famous Russian actors.

In 2015, the French director René Féret created the movie “Anton Chekov 1890” based on his own scenario. The young actor Nicolas Giraud played the Russian playwright. The plot is based on the writer’s life in 1885-1890.

Personal Life

The writer’s personal life is full of love stories. The relationships between Chekhov and his women could last for years, and the writer’s affairs were not sequential. The women often knew about each other, yet they did not rush to break up with their beloved.

In 1888, the writer was attracted to Lidija Mizinova. The 19-year-old girl was a friend of Chekhov’s sister. Lika wanted to become the writer’s wife, but all Chekhov wanted was to be free and independent – he never considered her as a possible spouse. However, it did not prevent Chekhov from giving her hope for almost ten years. He enjoyed her company but avoided speaking about marriage and household.

In the first years, Chekhov laughed at his possible rivals in front of Lika, thus leaving them no chance to gain the young woman’s favor. Later, Chekhov himself introduced Lika who was in love with him with the womanizer Ignaty Potapenko.

Mizinova entered into the relationship with the married man, got pregnant, and had a daughter who died in her early childhood. Chekhov used these facts – Mizinova was the prototype figure of Nina Zarechnaya in “The Seagull.” After complex and complicated games with Chekhov and Potapekno, Lika found comfort in her marriage – in 1902, she married the theater director Alexander Sanin.

In the 1880s, Anton Pavlovich met Elena Shavrova. The 15-year-old girl brought her short story manuscript to Chekhov and fell over heels in love with him. However, the girl realized that she had few chances to be loved back and married five years after their meeting.

In 1897, Elena went to Moscow to visit her relatives. She met Chekhov again, and they had a love affair. The lovers escaped to Crimea and spent some time in Yalta; in the end, they split up. Chekhov wrote her about 70 letters – more than to any other woman he loved. In the short story “The Lady with the Dog,” the writer portrayed Shavrova as the female character.

In 1898, at “The Seagull” premiere, the playwright met his old acquaintance Nina Korsh who had fallen in love with Chekhov at 12. She did not miss the chance to mesmerize the writer, and Anton Pavlovich got attracted. As a result, Nina became pregnant. The writer is considered to have no direct offspring, but in 1900, his daughter Tatyana was born. Chekhov did not know about it since he left Nina for Olga Knipper, and Korsh never told him about her child. Afterwards, Nina and her parent went to Paris. Tatyana Antonovna followed in the footsteps of her father and became a doctor.

Olga Knipper was the woman who managed to persuade Chekhov to marry her. They met in 1898 during one of “The Seagull” rehearsals. Olga was a beautiful, charming woman and actress. The couple had no children. Knipper was pregnant, but no successor was born.

The letters from Chekhov’s archive give an ambiguous impression concerning his marriage to Knipper. Olga did not leave the stage, and Chekhov lived in Yalta most of the time, managing his tuberculosis episodes. The love story of the writer and his wife began with mutual feelings and beautiful courtship, yet it grew only into the epistolary novel with occasional meetings.

Chekhov’s friends believed that if he had not married Olga he would have lived longer and happier. However, the denouement of this story was not as dramatic as it could have been: in the last days, the playwright’s wife was by his side, not touring.

Disease and Death

Chekhov had tuberculosis. For the first time, he discovered the symptoms of consumption at 24. Since 1885, his sickness became more apparent: according to the writer’s memories, the temperature was accompanied by coughing blood. In his youth, Anton Pavlovich did not have treatment for tuberculosis – he thought the symptoms were the signals of another disease.

Later, the writer used to hide his poor physical condition from the nearest and dearest – he did not want to disturb his mother and sister. By 1897, the playwright was seriously ill, and he had regular bleedings in his right lung. This fact made him undergo examination conducted by doctor Ostroumov.

To study Chekhov’s disease symptoms, he was hospitalized. The doctors made the diagnosis and prescribed treatment. As long as the writer felt better, he started asking to let him go home – he wanted to continue his literary work. In 1898, coughing blood lasted for several days, yet he disguised this fact from his family.

The pain that had become an integral part of the writer’s life was also present in his characters. It is particularly evident in his work “The Story of an Unknown Man.”

The writer was prescribed visiting various health resorts the road to which was sometimes too heavy for a sick person. Living in Yalta extended his life till his marriage. As Ivan Bunin believed, his wife undermined his health with her frequent departures. She did not get along well with the writer’s sister Maria which gave more reasons to worry. Shortly before he died, Chekhov and his wife went to the resort in South Germany.

In summer 1904, in Badenweiler, the writer passed away. The reason of Chekhov’s death was tuberculosis. It began when the playwright felt worse than usual. When a doctor came, Chekhov was sure he was dying. He asked for a glass of champagne, had a drink, and died.

Interesting facts

- In his childhood, Chekhov was called “bomb” because he had a large head. Together with his brothers, he sang in a church choir led by his father.

- Sometimes, the writer did not use his real surname in his works. Scholars know more than 40 pseudonyms invented by Anton Pavlovich for himself.

- The writer loved dogs; he had two dachshunds. He called his pets Hina Markovna and Brom Isaevich in honor of popular medicines. The writer also had a mongoose.

- The playwright was friends with Pyotr Tchaikovsky, Maxim Gorky, Isaaс Levitan, Ivan Bunin; he called Leo Tolstoy his idol.

- Anton Pavlovich’s height was more than 180 cm. His charm attracted many women. The playwright’s friends jokingly called them “antonovkas.”

- The coffin with the writer’s body was delivered to Moscow from Germany in a car labeled “Oysters.” It was the only part of the train with refrigeration.

- After the writer’s death, one of his literary colleagues published memoirs “A.P. Chekhov in my life.” Lydia Avilova claimed that their relationship was passionate, although there is no documental evidence supporting this version. In his letters, Anton Pavlovich called her “matushka” (“mother”) or “the honorable.” Lydia Avilova explained it by the fact that she had burned the majority of the personal letters.

- The historians doubt her memoirs are true and believe she wanted to attract attention to herself by the famous colleague’s name.

Photo

Anton Pavlovich Chekhov (Russian: Антон Павлович Чехов)

Anton Pavlovich Chekhov (1860 — 1904), was a Russian playwright and master of the modern short story. His best plays and short stories have very simple plots, but this simplicity reveals deep emotions and hidden thoughts of the characters creating an unforgettable impression on the readers. Chekhov is regarded as the outstanding representative of the late 19th-century Russian realist school.

Anton Chekhov was born in the Black Sea port of Taganrog. His grandfather used to be a serf, but he managed to purchase his family’s freedom. His father Pavel Chekhov owned a grocery shop. Little Chekhov used to spend a lot of time there. He learned to observe the everyday lives of different people and his ability to listen later became one of his most valuable skills as a writer.

Unfortunately, Pavel Chekhov wasn’t successful in his business. In 1876, he was declared bankrupt, so he moved with the family to Moscow to make a fresh start. Anton Chekhov stayed in Taganrog to finish his education and supported himself by working as a tutor for younger boys. In 1879, he joined the family and enrolled in the medical school at I.M. Sechenov First Moscow State Medical University.

By the time of Anton’s graduation in 1884, his father was no longer earning a living. So Anton Chekhov supported his family through his freelance earnings as a journalist and writer of comic sketches. In the same year, the first symptoms of tuberculosis appeared, but Chekhov couldn’t afford to stop his work as a physician or make a pause in his writing in order to get treatment.

In 1887, Chekhov took a trip to Ukraine and fell in love with the beauty of the steppe. In 1888, he published his first novel in a leading literary review called Severny Vestnik («Northern Herald»). The novel described a journey in the Ukraine as seen through the eyes of a child sent away from his family. It was the first among more than 50 stories published in a variety of journals between 1888 and his death in 1904.

End of the 19th century and beginning of the 20th century was the time when artists and scholars debated the purpose of literature. Some felt that literature should offer «life instructions.» Others felt that art should simply exist to please. Chekhov mostly agreed with the latter view. But at some point in this life he became obsessed with an idea of a prison reform. In early 1890, he even took an expedition to a remote island, Sakhalin, which was an imperial Russian penal settlement. Chekhov stayed there for three months, interviewing thousands of convicts and settlers for a census. After his return, he published his findings as a research thesis called The Island of Sakhalin (1893 — 1894).

In 1892, Chekhov bought a country estate in the village of Melikhovo, about 50 miles south of Moscow. He moved there with his parents and his sister Maria. The Melikhovo period was the most fruitful for Chekhov as a short story writer. During those six years, he wrote «The Butterfly,» «Neighbors» (1892), «An Anonymous Story» (1893), «The Black Monk» (1894), «Murder,» and «Ariadne» (1895). He worked as a doctor, charging poor people nothing for his services. He also took the responsibilities of the landlord very seriously, so he built three schools, a fire station, and a clinic.

In some of his stories of the Melikhovo period, Chekhov attacked the teachings of Leo Tolstoy. He used to be Tolstoy’s follower at first, but later Chekhov rejected those doctrines. He illustrated his new view in one particularly outstanding story called «Ward Number Six» (1892). The story pictures an elderly doctor who shows himself nonresistant to evil refusing to do anything in order to change the appalling conditions in the mental ward of which he has charge — only to find himself later a patient of the same ward.

Chayka (The Seagull) is Chekhov’s only dramatic work composed during the Melikhovo period. It received a disastrous response on opening night. The audience actually booed during the first act. Fortunately, innovative directors Konstantin Stanislavski and Vladimir Nemirovich-Danchenko believed in Chekhov’s work. Their new approach to drama invigorated audiences. The Moscow Art Theatre restaged The Seagull and it was a triumph.

Soon after, the Moscow Art Theatre, led by Stanislavski and Nemirovich-Danchenko, produced the rest of Chekhov’s masterpieces: Uncle Vanya (1899), The Three Sisters (1900), and The Cherry Orchard (1904).

In March 1897 Chekhov suffered a major lung hemorrhage caused by tuberculosis. Chekhov had to sell his Melikhovo estate. He built a villa in Yalta, the Crimean coastal resort. From then on, he spent most of his winters there. Both his plays Three Sisters and The Cherry Orchard were written in Yalta. Soon Chekhov had become attracted by a young actress, Olga Knipper, who was starring in his plays. He married her in 1901; the marriage probably marked the only profound love affair of his life. But since his wife continued to pursue her acting career and Chekhov was badly ill, they lived apart during most of the winter months and had no children. In 1904, Chekhov died of tuberculosis in Badenweiler, Germany, where he was together with his wife.

During and after his lifetime, Anton Chekhov was adored throughout Russia. Aside from his beloved stories and plays, he is also remembered as a humanitarian and a philanthropist. However, Chekhov remained largely unknown to the international audience until after World War I when his works were finally translated by Constance Garnett (into English) and others.

One of the first non-Russians to praise Chekhov’s plays was George Bernard Shaw, who subtitled his Heartbreak House «A Fantasia in the Russian Manner on English Themes,» and pointed out similarities between the predicament of the British landed class and that of their Russian counterparts as depicted by Chekhov: «the same nice people, the same utter futility.»

In the United States, Chekhov’s reputation grew together with the influence of Stanislavski’s system of acting, with its notion of subtext: «Chekhov often expressed his thought not in speeches,» wrote Stanislavski, «but in pauses or between the lines or in replies consisting of a single word … the characters often feel and think things not expressed in the lines they speak.» This subtextual approach to drama influenced many well-known playwrights, actors, and screenwriters.

Alan Twigg, the chief editor and publisher of the Canadian book review magazine BC Bookworld wrote, «One can argue Anton Chekhov is the second-most popular writer on the planet. Only Shakespeare outranks Chekhov in terms of movie adaptations of their work, according to the movie database IMDb. … We generally know less about Chekhov than we know about mysterious Shakespeare.»

Sources:

- Wikipedia

- Encyclopedia Britannica

- ThoughtCo

- TheatreHistory.com

About the author

Антон Павлович Чехов

Литератор и врач, публицист и благотворитель, классик мировой драматургии Антон Павлович Чехов прожил всего 44 года, но его творчество повлияло на многие поколения писателей в России и за рубежом. Чехов создал новый тип драмы и перевернул прежние представления о том, каким должно быть театральное искусство.

Детство и юность Антона Чехова

Будущий писатель родился 17 (29) января 1860 года на юге России, в Таганроге, в большой купеческой семье. Глава семейства, Павел Егорович, продавал бакалейные товары. Он был человеком набожным, но крутого нрава, и его пять сыновей и дочь рано начали трудиться. С пяти утра они пели в церковном хоре, а вечерами сторожили отцовскую лавку.

В восьмилетнем возрасте Чехов поступил в таганрогскую гимназию, которая в наши дни носит имя писателя. Именно здесь, в стенах одного из старейших учебных заведений юга России, юный Антон Чехов начал писать рассказы и даже обзавёлся первым из своих многочисленных псевдонимов – Антоша Чехонте. Молодой гимназист страстно полюбил литературу и сцену: он выпускал юмористический журнал, участвовал в домашних спектаклях своих друзей, не пропускал постановок таганрогского театра.

В 1876 году, когда Чехову исполнилось всего 16 лет, отец его разорился, продал имущество и уехал с семьёй в Москву. Антон остался в Таганроге, чтобы окончить гимназию. Он жил у бывшего квартиранта своих родителей и зарабатывал на жизнь частными уроками.

В 1879 году Чехов поступил в Московский университет. Он выбрал профессию врача и уже с 1882 года погрузился в медицинскую практику – начал помогать докторам Чикинской больницы в подмосковном Воскресенске (ныне Истра). В этой же лечебнице Чехов продолжил работать и после окончания в 1884 году университета. Затем молодой врач перебрался в Звенигород и на некоторое время возглавил местную больницу.

Становление Антона Чехова как литератора

В 1880 году на страницах сатирического журнала «Стрекоза» появился первый печатный рассказ А.П. Чехова под названием «Письмо учёному соседу». Чехов писал много и быстро, и за этим дебютом последовали публикации коротких юмористических рассказов и фельетонов в различных московских и петербургских изданиях. В начале 1880-х миниатюры Чехова выходили под разнообразными псевдонимами (Антоша Чехонте, Человек без селезёнки и др.), что было характерной чертой жанра.

Вскоре Чехов «перерос» фельетоны, водевили и юморески. Со второй половины 1880-х темы его произведений стали серьёзнее, автора всё больше занимал трагизм обыденной жизни. В эти годы зародился интерес Чехова к повседневности, начала проявляться та особенная «бессобытийность» чеховской прозы, которую впоследствии будут отмечать многие критики.

К концу 1880-х гг. юмористические миниатюры уступили место повестям. «Степь» и «Скучная история», опубликованные в толстых журналах, принесли Чехову литературную славу. Вышедший в 1887 году сборник рассказов «В сумерках» был отмечен Пушкинской премией Императорской Санкт-Петербургской академии наук. К этому же времени относится и первое серьёзное драматургическое произведение А.П. Чехова – пьеса «Иванов». Рассказы конца 1880-х сочетали в себе подчёркнуто бесстрастное описание малозначительных событий повседневности и сквозящую в них глубокую трагичность («Спать хочется»).

Писательская деятельность. Творчество Чехова