Venn diagram showing the relationships between homophones (blue circle) and related linguistic concepts

A homophone () is a word that is pronounced the same (to varying extent) as another word but differs in meaning. A homophone may also differ in spelling. The two words may be spelled the same, for example rose (flower) and rose (past tense of «rise»), or spelled differently, as in rain, reign, and rein. The term homophone may also apply to units longer or shorter than words, for example a phrase, letter, or groups of letters which are pronounced the same as another phrase, letter, or group of letters. Any unit with this property is said to be homophonous ().

Homophones that are spelled the same are also both homographs and homonyms, e.g. the word read, as in «He is well read» (he is very learned) vs. the sentence «I read that book» (I have finished reading that book).[a]

Homophones that are spelled differently are also called heterographs, e.g. to, too, and two.

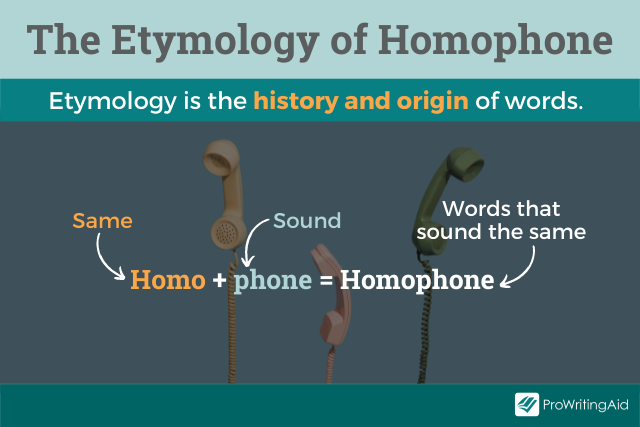

Etymology[edit]

«Homophone» derives from Greek homo- (ὁμο‑), «same», and phōnḗ (φωνή), «voice, utterance».

Wordplay and games[edit]

Homophones are often used to create puns and to deceive the reader (as in crossword puzzles) or to suggest multiple meanings. The last usage is common in poetry and creative literature. An example of this is seen in Dylan Thomas’s radio play Under Milk Wood: «The shops in mourning» where mourning can be heard as mourning or morning. Another vivid example is Thomas Hood’s use of birth and berth as well as told and toll’d (tolled) in his poem «Faithless Sally Brown»:

- His death, which happen’d in his berth,

- At forty-odd befell:

- They went and told the sexton, and

- The sexton toll’d the bell.

In some accents, various sounds have merged in that they are no longer distinctive, and thus words that differ only by those sounds in an accent that maintains the distinction (a minimal pair) are homophonous in the accent with the merger. Some examples from English are:

- pin and pen in many southern American accents

- by and buy

- merry, marry, and Mary in most American accents

- The pairs do and due as well as forward and foreword are homophonous in most American accents but not in most English accents

- The pairs talk and torque as well as court and caught are distinguished in rhotic accents, such as Scottish English, and most dialects of American English, but are homophones in some non-rhotic accents, such as British Received Pronunciation

Wordplay is particularly common in English because the multiplicity of linguistic influences offers considerable complication in spelling and meaning and pronunciation compared with other languages.

Malapropisms, which often create a similar comic effect, are usually near-homophones. See also Eggcorn.

Same-sounding phrases[edit]

Same-sounding (homophonous, or homophonic) phrases are often used in various word games. Examples of same-sounding phrases (which may only be true homophones in certain dialects of English) include:

- ice cream vs. I scream (as in the meme I scream. You scream. We all scream for ice cream.)

- euthanasia vs. Youth in Asia

- depend vs. deep end

- Gemini vs. gem in eye vs. Jim and I (vs. Jem in eye)

- the sky vs. this guy (most notably as a mondegreen in «Purple Haze» by Jimi Hendrix)

- four candles vs. fork handles

- sand which is there vs. sandwiches there

- philanderers vs. Flanders

- example vs. egg sample

- some others vs. some mothers vs. smothers

American comedian Jeff Foxworthy frequently uses same-sounding phrases in his Appalachian comedy routine, which play on exaggerated «country» accents. Notable examples include:

- Initiate vs. and then she ate: «My wife ate two sandwiches, initiate a bag o’ tater chips.»

- Mayonnaise vs. Man, there is: «Mayonnaise a lot of people here tonight.»

- Innuendo vs. in your window: «Hey dude I saw a bird fly innuendo.»

- Moustache vs. must ask: «I Moustache you a question.»

During the 1980s, an attempt was made to promote a distinctive term for same-sounding multiple words or phrases, by referring to them as «oronyms»,[b]

but the term oronym was already well established in linguistics as an onomastic designation for a class of toponymic features (names of mountains, hills, etc.),[2] the alternative use of the same term was not well accepted in scholarly literature.[3]

Number[edit]

English[edit]

There are sources[4] which maintain lists of homophones (words with identical pronunciations but different spellings) and even ‘multinyms.’ There is disagreement among such lists due to dialectical variations in pronunciation and archaic uses. In English, concerning groups of homophones (excluding proper nouns), there are approximately 88 triplets, 24 quadruplets, 2 quintuplets, 1 sextet, 1 septet, and 1 questionable octet (possibly a second septet). The questionable octet is:

- raise, rays, rase, raze, rehs, res, reais, [race]

Other than the common words raise, rays, and race this octet includes

- raze – a verb meaning «to demolish, level to the ground» or «to scrape as if with a razor»

- rase – an archaic verb meaning «to erase»

- rehs – the plural of reh, a mixture of sodium salts found as an efflorescence in India

- res – the plural of re, a name for one step of the musical scale; obsolete legal term for «the matter» or «incident»

- reais – the plural of real, the currency unit of Brazil

The inclusion of «race» in the octet above is questionable, since its pronunciation differs from the other words on the list (ending with /s/ instead of /z/).

If proper names are included, then a possible nonet would be:

- Ayr – a town in Scotland

- Aire – a river in Yorkshire

- Eyre – legal term and various geographic locations

- heir – one who inherits

- air – the ubiquitous atmospheric gas that people breathe; a type of musical tune

- err – to make an error

- ere – poetic / archaic «before»

- e’er – poetic «ever» (some speakers)

- are – a defunct, small, metric unit of area

German[edit]

There are many homophones in present-day standard German. As in other languages, however, there exists regional and/or individual variation in certain groups of words or in single words, so that the number of homophones varies accordingly. Regional variation is especially common in words that exhibit the long vowels ä and e. According to the well-known dictionary Duden, these vowels should be distinguished as /ɛ:/ and /e:/, but this is not always the case, so that words like Ähre (ear of corn) and Ehre (honor) may or may not be homophones.

Individual variation is shown by a pair like Gäste (guests) – Geste (gesture), the latter of which varies between /ˈɡe:stə/ and /ˈɡɛstə/ and by a pair like Stiel (handle, stalk) – Stil (style), the latter of which varies between /ʃtiːl/ and /stiːl/.

Besides websites that offer extensive lists of German homophones,[5] there are others which provide numerous sentences with various types of homophones.[6] In the German language homophones occur in more than 200 instances. Of these, a few are triples like

- Waagen (weighing scales) – Wagen (cart) – wagen (to dare)

- Waise (orphan) – Weise (way, manner) – weise (wise)

Most are couples like lehren (to teach) – leeren (to empty).

Spanish[edit]

Although Spanish has far fewer homophones than in English, they are far from being non-existent. Some are homonyms, such as basta, which can either mean ‘enough’ or ‘coarse’, but most exist because of homophonous letters. For example, the letters b and v are pronounced exactly alike, so the words basta (coarse) and vasta (vast) are pronounced identically.[7]

Other homonyms are etymologically related, but have different genders, and in some cases the different genders producing different lexical items. In the case of persona, el persona (the male or ungendered/unidentified person) and la persona (the female person) are the masculine and feminine forms of the noun persona (person) respectively. However, el capital and la capital have drastically different meanings, in which the masculine noun means ‘money’ and the feminine noun means ‘capital city’ or ‘capital letter’.[8]

Japanese[edit]

There are many homophones in Japanese, due to the use of Sino-Japanese vocabulary, where borrowed words and morphemes from Chinese are widely used in Japanese, but many sound differences, such as the original words’ tones, are lost.[citation needed] These are to some extent disambiguated via Japanese pitch accent (i.e. 日本 vs. 二本, both pronounced nihon, but with different pitches), or from context, but many of these words are primarily or almost exclusively used in writing, where they are easily distinguished as they are written with different kanji; others are used for puns, which are frequent in Japanese.

An extreme example is kikō (hiragana: きこう), which is the pronunciation of at least 22 words (some quite rare or specialized, others common; all these examples are two-character compounds), including:

- 機構 (organization / mechanism)

- 紀行 (travelogue)

- 稀覯 (rare)

- 騎行 (horseback riding)

- 貴校 (school (respectful))

- 奇功 (outstanding achievement)

- 貴公 (word for «you» used by men addressing male equals or inferiors)

- 起稿 (draft)

- 奇行 (eccentricity)

- 機巧 (contrivance)

- 寄港 (stopping at port)

- 帰校 (returning to school)

- 気功 (breathing exercise, qigong)

- 寄稿 (contribute an article / a written piece)

- 機甲 (armor, e.g. of a tank)

- 帰航 (homeward voyage)

- 奇効 (remarkable effect)

- 季候 (season / climate)

- 気孔 (stoma)

- 起工 (setting to work)

- 気候 (climate)

- 帰港 (returning to port)

Even some native Japanese words are homophones. For example, kami (かみ) is the pronunciation of the words

- 紙 (paper)

- 髪 (hair)

- 神 (god/spirit)

- 上 (up)

The former two words are disambiguated from the latter two by pitch accent.

Korean[edit]

The Korean language contains a combination of words that strictly belong to Korean and words that are loanwords from Chinese. Due to Chinese being pronounced with varying tones and Korean’s removal of those tones, and because the modern Korean writing system, Hangeul, has a more finite number of phonemes than, for example, Latin-derived alphabets such as that of English, there are many homonyms with both the same spelling and pronunciation.

For example

- ‘화장(化粧)하다‘: ‘to put on makeup’ vs. ‘화장(火葬)하다‘: ‘to cremate’

- ‘유산(遺産)‘: ‘inheritance’ vs. ‘유산(流産)‘: ‘miscarriage’

- ‘방구‘: ‘fart’ vs. ‘방구(防具)‘: ‘guard’

- ‘밤[밤ː]’: ‘chestnut’ vs. ‘밤’: ‘night’

There are heterographs, but far fewer, contrary to the tendency in English. For example,

- ‘학문(學問)’: ‘learning’ vs. ‘항문(肛門)’: ‘anus’.

Using hanja (한자; 漢字), which are Chinese characters, such words are written differently.

As in other languages, Korean homonyms can be used to make puns. The context in which the word is used indicates which meaning is intended by the speaker or writer.

Mandarin Chinese[edit]

Due to phonological constraints in Mandarin syllables (as Mandarin only allows for an initial consonant, a vowel, and a nasal or retroflex consonant in respective order), there are only a little over 400 possible unique syllables that can be produced,[9] compared to over 15,831 in the English language.[10]

Chinese has an entire genre of poems taking advantage of the large amount of homophones called one-syllable articles, or poems where every single word in the poem is pronounced as the same syllable if tones are disregarded. An example is the Lion-Eating Poet in the Stone Den.

Like all Chinese languages, Mandarin uses phonemic tones to distinguish homophonic syllables; Mandarin has five tones. A famous example,

- mā (妈) means «mother»

- má (麻) means «hemp»

- mă (马) means «horse»

- mà (骂) means «scold»

- ma (吗) is a yes / no question particle

Although all these words consist of the same string of consonants and vowels, the only way to distinguish each of these words audibly is by listening to which tone the word has, and as shown above, saying a consonant-vowel string using a different tone can produce an entirely different word altogether. If tones are included, the number of unique syllables in Mandarin increases to at least 1,522.[11]

However, even with tones, Mandarin retains a very large amount of homophones. Yì, for example, has at least 125 homophones,[12] and it is the pronunciation used for Chinese characters such as 义, 意, 易, 亿, 议, 一, and 已.

There are even place names in China that have identical pronunciations, aside for the difference in tone. For example, there are two neighboring provinces with nearly identical names, Shanxi (山西) and Shaanxi (陕西) Province. The only difference in pronunciation between the two names are the tone in the first syllable (Shanxi is pronounced Shānxī whereas Shaanxi is pronounced Shǎnxī). As most languages exclude the tone diacritics when transcribing Chinese place names into their own languages, the only way to visually distinguish the two names is to write Shaanxi in Gwoyeu Romatzyh romanization. Otherwise, nearly all other spellings of placenames in mainland China are spelled using Hanyu Pinyin romanization.

Many scholars believe that the Chinese language did not always have such a large number of homophones and that the phonological structure of Chinese syllables was once more complex, which allowed for a larger amount of possible syllables so that words sounded more distinct from each other.

Scholars also believe that Old Chinese had no phonemic tones, but tones emerged in Middle Chinese to replace sounds that were lost from Old Chinese. Since words in Old Chinese sounded more distinct from each other at this time, it explains why many words in Classical Chinese consisted of only one syllable. For example, the Standard Mandarin word 狮子(shīzi, meaning «lion») was simply 狮 (shī) in Classical Chinese, and the Standard Mandarin word 教育 (jiàoyù, «education») was simply 教 (jiào) in Classical Chinese.

Since many Chinese words became homophonic over the centuries, it became difficult to distinguish words when listening to documents written in Classical Chinese being read aloud. One-syllable articles like those mentioned above are evidence for this. For this reason, many one-syllable words from Classical Chinese became two-syllable words, like the words mentioned in the previous paragraph.

Even with the existence of two- or two-syllable words, however, there are even multisyllabic homophones. Such homophones even play a major role in daily life throughout China, including Spring Festival traditions, which gifts to give (and not give), political criticism, texting, and many other aspects of people’s lives.[13]

Another complication that arises within the Chinese language is that in non-rap songs, tones are disregarded in favor of maintaining melody in the song.[14] While in most cases, the lack of phonemic tones in music does not cause confusion among native speakers, there are instances where puns may arise.

Subtitles in Chinese characters are usually displayed on music videos and in songs sung on movies and TV shows to disambiguate the song’s lyrics.

Vietnamese[edit]

It is estimated that there are approximately 4,500 to 4,800 possible syllables in Vietnamese, depending on the dialect.[15] The exact number is difficult to calculate because there are significant differences in pronunciation among the dialects. For example, the graphemes and digraphs «d», «gi», and «r» are all pronounced /z/ in the Hanoi dialect, so the words dao (knife), giao (delivery), and rao (advertise) are all pronounced /zaw˧/. In Saigon dialect, however, the graphemes and digraphs «d», «gi», and «v» are all pronounced /j/, so the words dao (knife), giao (delivery), and vao (enter) are all pronounced /jaw˧/.

Pairs of words that are homophones in one dialect may not be homophones in the other. For example, the words sắc (sharp) and xắc (dice) are both pronounced /săk˧˥/ in Hanoi dialect, but pronounced /ʂăk˧˥/ and /săk˧˥/ in Saigon dialect respectively.

Psychological research[edit]

Pseudo-homophones[edit]

Pseudo-homophones are pseudowords that are phonetically identical to a word. For example, groan/grone and crane/crain are pseudo-homophone pairs, whereas plane/plain is a homophone pair since both letter strings are recognised words. Both types of pairs are used in lexical decision tasks to investigate word recognition.[16]

Use as ambiguous information[edit]

Homophones, specifically heterographs, where one spelling is of a threatening nature and one is not (e.g. slay/sleigh, war/wore) have been used in studies of anxiety as a test of cognitive models that those with high anxiety tend to interpret ambiguous information in a threatening manner.[17]

See also[edit]

- Homograph

- Homonym

- Synonym

- Dajare, a type of wordplay involving similar-sounding phrases

- Perfect rhyme

- Wiktionary

- List of dialect-independent homophones

- List of dialect-dependent homophones

Footnotes[edit]

- ^

According to the strict sense of homonyms as words with the same spelling and pronunciation; however, homonyms according to the loose sense common in nontechnical contexts are words with the same spelling or pronunciation, in which case all homophones are also homonyms.[1] - ^

The name oronym was first proposed and advocated by Gyles Brandreth in his book The Joy of Lex (1980), and such use was also accepted in the BBC programme Never Mind the Full Stops, which featured Brandreth as a guest.

References[edit]

- ^ «Homonym». Random House Unabridged Dictionary. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016 – via Dictionary.com.

- ^ Room 1996, p. 75.

- ^ Stewart 2015, p. 91, 237.

- ^ Burkardt, J. «Multinyms». Department of Scientific Computing. Fun / wordplay. Florida State University. Archived from the original on 25 August 2016.

- ^ See, e.g. «Homophone und homonyme im deutschen Homophone». yumpu.com (in German). Archived from the original on 8 March 2021. Retrieved 15 March 2020.

- ^ See Fausto Cercignani, «Beispielsätze mit deutschen Homophonen» [Example sentences with German homophones] (in German). Archived from the original on 29 May 2020.

- ^ «51 Spanish Words That Sound Exactly Like Other Spanish Words». ThoughtCo. Retrieved 27 August 2022.

- ^ «37 Spanish Nouns Whose Meanings Change With Gender». ThoughtCo. Retrieved 27 August 2022.

- ^ «Is there any similarity between Chinese and English?». Learn Mandarin Chinese Online. Study Online Mandarin Chinese Courses. 7 July 2017. Archived from the original on 25 January 2021. Retrieved 18 December 2020.

- ^ Barker (22 August 2016). «Syllables». Linguistics. New York University. Archived from the original on 22 August 2016. Retrieved 17 December 2020.

- ^ «Compare that with 413 syllables for Chinese if you ignore tones, 1,522 syllables». news.ycombinator.com. Hacker News. Archived from the original on 14 April 2021. Retrieved 18 December 2020.

- ^ Chang, Chao-Huang. «Corpus-based adaptation mechanisms for Chinese Homophone disambiguation» (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 14 April 2021. Retrieved 18 December 2020.

- ^ «Chinese Homophones and Chinese Customs». yoyochinese.com (blog). Archived from the original on 9 April 2021. Retrieved 18 December 2020.

- ^ «How do people sing in a tonal language?». Diplomatic Language Services. 8 September 2016. Archived from the original on 28 November 2020. Retrieved 30 December 2020.

- ^ «vietnamese tone marks pronunciation». pronunciator.com. Archived from the original on 18 May 2022. Retrieved 5 February 2021.

- ^ Martin, R.C. (1982). «The pseudohomophone effect: The role of visual similarity in non-word decisions». Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology. 34A (Pt 3): 395–409. doi:10.1080/14640748208400851. PMID 6890218. S2CID 41699283.

- ^ Mogg, K.; Bradley, B.P.; Miller, T.; Potts, H.; Glenwright, J.; Kentish, J. (1994). «Interpretation of homophones related to threat: Anxiety or response bias effects?». Cognitive Therapy and Research. 18 (5): 461–477. doi:10.1007/BF02357754. S2CID 36150769.

Sources[edit]

- Franklyn, Julian (1966). Which Witch? (1st ed.). New York, NY: Dorset Press. ISBN 0-88029-164-8.

- Room, Adrian (1996). An Alphabetical Guide to the Language of Name Studies. Lanham and London, UK: The Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-081083169-8. Archived from the original on 14 April 2021. Retrieved 23 December 2020.

- Stewart, Garrett (2015). The Deed of Reading: Literature, writing, language, philosophy. Ithaca, NY and London, UK: Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-150170170-2. Archived from the original on 14 April 2021. Retrieved 23 December 2020.

External links[edit]

Look up homophone in Wiktionary, the free dictionary.

- Homophone.com – a list of American homophones with a searchable database.

- Reed’s homophones – a book of sound-alike words published in 2012

- Homophones.ml – a collection of homophones and their definitions

- Homophone Machine – swaps homophones in any sentence

- Useful tips … English homophones – homophones list, activities and worksheets

Homophones are words that have different meanings but are pronounced the same way.

Sometimes you’ll find that the words are spelled the same way, while other times they’ll be spelled differently.

Examples

Same Way

One homophone that is spelled the same way but has a different meaning is bow.

In Sherwood Forest, someone who meets Robin Hood might choose to bow to greet him. Robin Hood might then give him a bow and arrow.

Homophones that are spelled the same are both homonyms and homographs.

Different Way

One homophone pair that is spelled differently is sail and sale.

A person with a yacht might put it on sale because the sail is broken and he can’t afford to fix it.

Homophones that are spelled differently are called heterographs.

What Does Homophone Mean?

The word homophone comes from two Greek words that have been put together – homo and phone.

‘Homo’ means ‘same’ and ‘phone’ means ‘sound’ or ‘voice’. Homophone therefore literally means ‘same sound’ or ‘same voice.’

Make sure you check out our complete homophones list.

What Is a Homophone?

A homophone is a word that sounds the same as another word but is usually spelled differently and has a different meaning. Homophones may consist of two or more words, although pairs are more common than three or more words that sound the same. Examples of homophones that have three words are to, too, and two, and their, there, and they’re.

The English language is, honestly, a bit of a mess, and homophones are extra tricky. Today, we’re learning what homophones are, how to use them correctly, and where you can find homophones hiding in English.

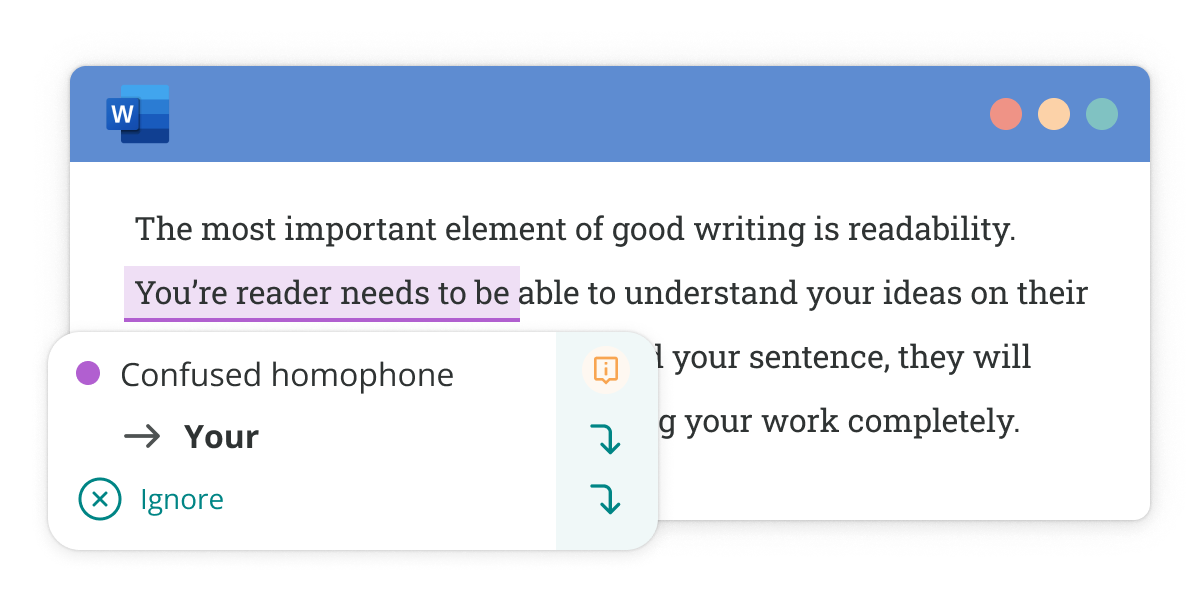

What Is the Difference between Homophones, Homonyms, and Homographs?

Do homophones always have different spellings? Well, it depends on who you ask. Let’s look at some other types of tricky words.

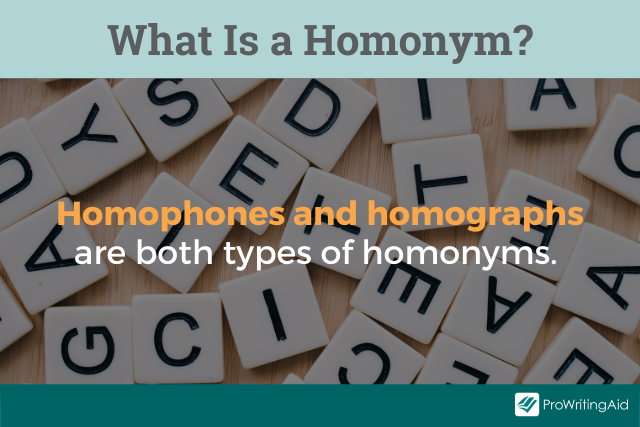

There are homophones, homographs, and homonyms. That’s enough to make anyone’s head spin! How do you tell the difference?

We can start by looking at the etymology of the words. The prefix homo- means «same.» The root phone comes from the Greek word phonos, which means «sound.» That means a homophone has the same sound. You can remember this by thinking of a phone, which we hear sounds through.

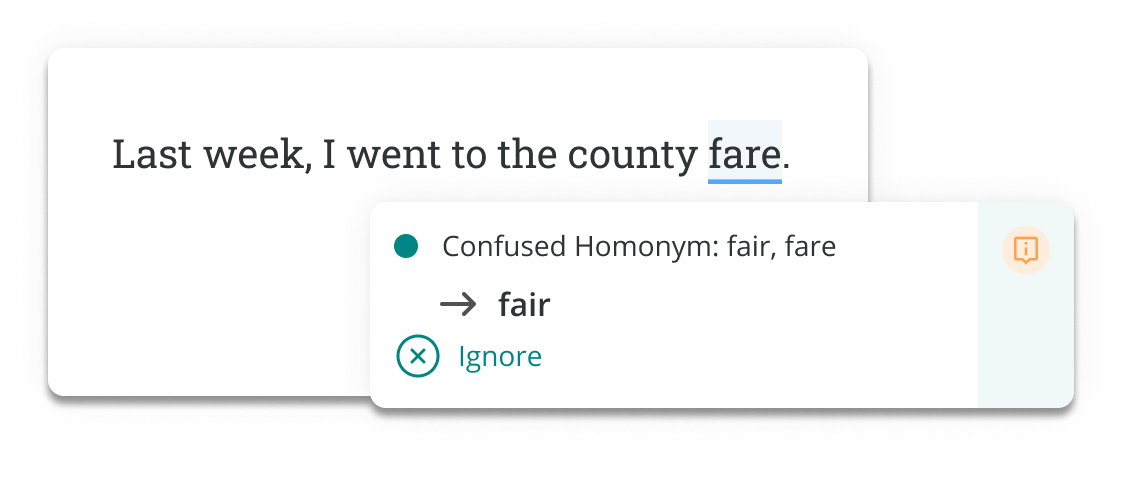

An example of a homophone pair is fare and fair. They sound alike but have different meanings. They are also spelled differently.

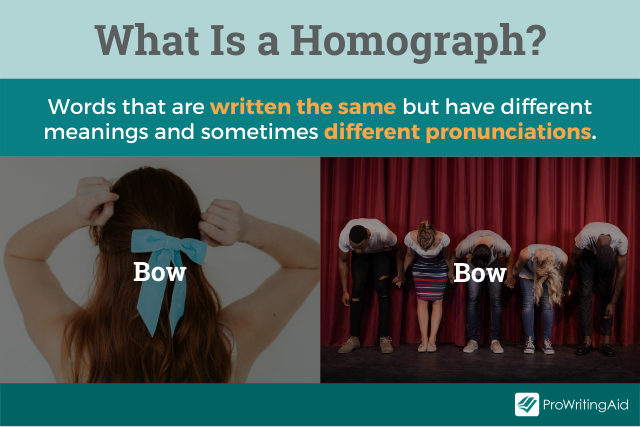

The root graph derives from the Greek graphein, which means «to write.» Same + write tells us that homographs are words that are written the same. They have the same spelling but different meanings and sometimes different pronunciations. Remember this by thinking of graphite, the part of a pencil that writes.

Now, let’s look at homonyms. Nym comes from the Greek word for «name.» Homonym means «same name,» but the definition of a homonym really depends on who you ask.

Some resources say that “homonym” only applies to words that are spelled the same but are pronounced differently in addition to having different definitions. In other words, it’s a homograph that does not sound alike.

In this strict sense, an example is bow. If you pronounce bow with a short /o/ sound, it can mean a part of a ship. If you pronounce it with a long /o/ sound, it’s something that shoots arrows.

Other resources say that a homonym is a word that is both a homophone and a homograph. It sounds the same, looks the same, and has different meanings.

One example of a homonym using this definition would be pitcher. It can mean the person who throws the ball in baseball or a vessel for pouring water. They sound the same and look the same, but they have different meanings.

Still others think that homonym is more of an umbrella term. Homophones and homographs are both types of homonyms. This is the definition we will use.

Now that you know the difference between the types of homonyms, let’s learn about homophones in more detail.

Do Homophones Rhyme?

Homophones rhyme because they are words that sound alike. When words rhyme, they have the same ending vowel sound. All homophones are rhymes, but not all rhymes are homophones.

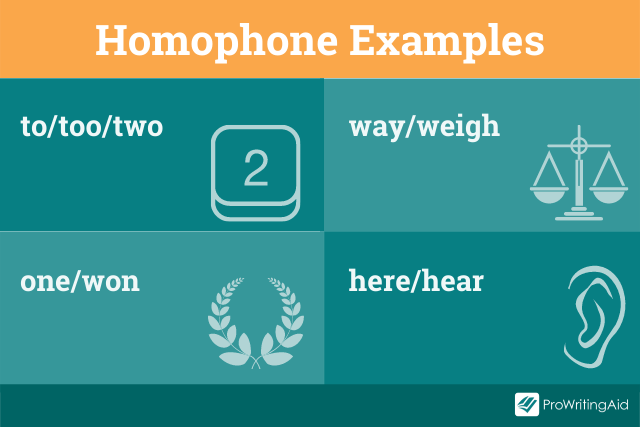

What Are the Most Common Homophones in English?

There are thousands of English homophones. It’s hard to pin down an exact number because some words are homophones depending on regional accents. For example, sometimes people say «then» and «than» exactly the same, while others emphasize the differing vowel sounds.

Here are a few examples of common English homophones. We’ll go into more detail on some of these in a later section:

- to/too/two

- there/their/they’re

- which/witch

- way/weigh

- by/bye/buy

- whether/weather

- accept/except

- one/won

- you’re/your

- here/hear

These are just a few of the most commonly confused homophones in English. We’ll look at even more examples in the following sections.

How Do I Know Which Homophone to Use?

It’s important to know which homophone to use to ensure your meaning is clear. But how can you keep up when there are so many homophones to use?

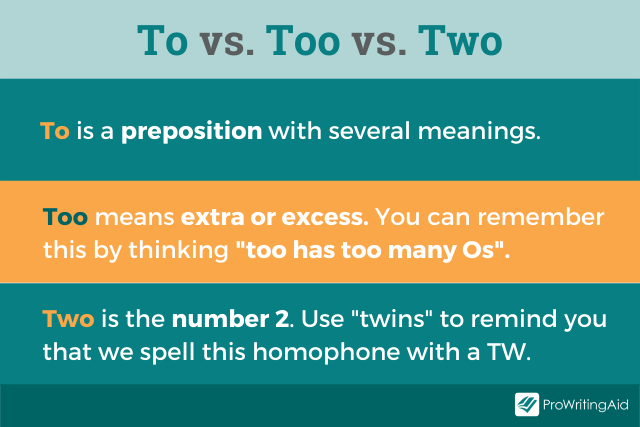

Some homophones have tricks to help you remember them. Let’s look at one of the most commonly confused homophones: to/ too /two. It’s extra tricky because it contains more than two words.

To is a preposition with several meanings. Too means extra or excess. You can remember this by thinking «too has too many Os.» Two is the number 2. Remember «twins» to remind you that we spell this homophone with a TW.

Mnemonic devices can help you remember the difference between two or more words. But there are just too many homophones to come up with a cool trick for all of them!

You can always check the dictionary. Or you can use ProWritingAid. Our Homonym Report will check for all of the homophones and homographs that you might have mixed up in your writing. You can find this report under “More Reports” or add it to your “Combo Report” settings to check for homophones every time.

Try the Homonym Report with a free ProWritingAid account.

What Are Some Examples of Homophones?

We’ve looked at a few examples of English homophones, but there are so many! Let’s go more in depth with our examples.

What Are Some Common Homophones with Their Definitions?

-

There/ their /they’re is one of the most commonly confused set of homophones. But these three words have more than just different spellings—they have very different meanings.

There has a number of applications across different parts of speech, but the definitions relate to a location or place. Their is the third-person plural possessive pronoun. They’re is a contraction that means «they are.»

-

Another common homophone pair that people mix up often is your/ you’re. Your is the second-person possessive pronoun. You’re is a contraction that means «you are.»

-

Here means “this place,” while hear means “to sense sound.” Whether is a conjunction, while weather is the conditions outdoors.

-

One is the number 1. Won is the past tense of the verb «win.» Accept is a verb that means “to receive or to agree.” Except is used to talk about excluding something or someone.

-

Another triplet homophone is by/ buy /bye. By is a preposition that usually means “near” or “next to.” Buy is a verb that means “to purchase.” Bye is short for «goodbye.»

-

Which is a preposition that means «what one.» A witch is a woman who does magic and might conjure images of pointy black hats and giant cauldrons.

-

A way is a path. We use the verb weigh to find out how heavy something is.

-

Its is the possessive form of the pronoun «it.» It shows that something belongs to it, e.g., the dog chewed its bone. It’s is a contraction that means «it is.»

We hope these definitions clear up some confusion about common homophones. But how do you use these tricky homophones in your writing?

What Are Some Examples of Homophones in Sentences?

We’ve defined several homophones that are all spelled differently. But the best way to understand homophones is to see them in the wild. Here are some example sentences with homophones.

- I always try to do the right thing. / Do you write fiction or nonfiction?

- When you see a bear, play dead. / My bare arms are freezing!

- Look how much he has grown. / He let out a groan at the terrible joke.

- You’re not allowed to go to the party. / She’s never said the words aloud.

- They will sell their house next year. / Mitochondria are the powerhouses of the cell.

- Do you know the muffin man? / He had no money left.

- My son is very handsome. / The sun shines brightly.

- Do you think the cake is too sweet? / The hotel suite has two bedrooms and a small kitchen.

- I’m not giving you another cent! / The hounds caught the scent of the rabbit and ran after it.

- He was so angry he punched a hole in the wall. / I was so hungry I ate the whole pie in one sitting.

- She came in fourth at the gymnastics meet. / Go forth and conquer!

- Clean up the mess in the pasta aisle. / Have you ever visited the Isle of Wight?

We could give you homophone examples all day! But now you can apply what you have learned about homophones to your own writing. Can you think of any other homophones that we didn’t include? Let us know in the comments.

ProWritingAid works wherever you do

Try our integrations for MS Word, Google Docs, Chrome, Scrivener, and more.

Sign up for a free account now.

- homophone

-

омофон

1) буква или комбинация букв, представляющих один и тот же звук речи

2) слова, одинаковые по звучанию, но имеющие разный смысл и/или написание

Англо-русский толковый словарь терминов и сокращений по ВТ, Интернету и программированию. .

1998-2007.

Смотреть что такое «homophone» в других словарях:

-

homophone — [ ɔmɔfɔn ] adj. et n. m. • 1827; gr. homophônos, de phônê « 2. son » ♦ Ling. Se dit de lettres, de mots qui ont la même prononciation. f et ph[ f ], eau et haut [ o ] sont homophones. N. m. Homophones homographes ou non. ⇒ homonyme. On s exagère… … Encyclopédie Universelle

-

Homophone — Hom o*phone, n. [Cf. F. homophone. See {Homophonous}.] 1. A letter or character which expresses a like sound with another. Gliddon. [1913 Webster] 2. A word having the same sound as another, but differing from it in meaning and usually in… … The Collaborative International Dictionary of English

-

homophone — (n.) 1843, from the adjective homophone (1620s), from Gk. homos same (see HOMO (Cf. homo ) (1)) + phone sound (see FAME (Cf. fame)). Related: Homophonic … Etymology dictionary

-

homophone — ► NOUN ▪ each of two or more words having the same pronunciation but different meanings, origins, or spelling (e.g. new and knew). ORIGIN from Greek ph n sound, voice … English terms dictionary

-

homophone — [häm′ə fōn΄] n. [< Gr homophōnos: see HOMOPHONIC] 1. any of two or more letters or groups of letters representing the same speech sound (Ex.: c in civil and s in song) 2. HOMONYM (sense 1) homophonous [hō mäf′ə nəs, həmäf′ə nəs] adj … English World dictionary

-

Homophone — In diesem Artikel oder Abschnitt fehlen folgende wichtige Informationen: Der Artikel erschöpft sich weitgehend in der Aufzählung von Beispielen für Homophone bzw. für Sprachen, die an Homophonen besonders reich sind. Er erklärt nicht, warum… … Deutsch Wikipedia

-

Homophone — A homophone is a word that is pronounced the same as another word but differs in meaning. The words may be spelled the same, such as rose (flower) and rose (past tense of rise ), or differently, such as carat , caret , and carrot , or two and too … Wikipedia

-

Homophone — Homophonie (linguistique) Pour les articles homonymes, voir Homophonie. onymie Acronymie Rétro acronymie Acronymie récursive … Wikipédia en Français

-

homophone — (o mo fo n ) adj. 1° Terme de grammaire. Mots homophones, mots qui se prononcent de même. 2° Hiéroglyphe homophone, hiéroglyphe représentant le son ou l articulation qui commence le mot par lequel l objet figuré est dénommé dans la langue… … Dictionnaire de la Langue Française d’Émile Littré

-

homophone — UK [ˈhɒməfəʊn] / US [ˈhɑməˌfoʊn] / US [ˈhoʊməˌfoʊn] noun [countable] Word forms homophone : singular homophone plural homophones linguistics a word that sounds the same as another word but has its own spelling, meaning, and origin … English dictionary

-

homophone — /hom euh fohn , hoh meuh /, n. 1. Phonet. a word pronounced the same as another but differing in meaning, whether spelled the same way or not, as heir and air. 2. a written element that represents the same spoken unit as another, as ks, a… … Universalium

Other forms: homophones

A homophone is a word that sounds the same as another word but has a different meaning and/or spelling. “Flower” and “flour” are homophones because they are pronounced the same but you certainly can’t bake a cake using daffodils.

Other common homophones are write and right, meet and meat, peace and piece. You have to listen to the context to know which word someone means if they’re spoken aloud. If they say they like your jeans (genes?), they’re probably talking about your pants and not your height and eye color — but you’d have to figure it out from the situation!

Definitions of homophone

-

noun

two words are homophones if they are pronounced the same way but differ in meaning or spelling or both (e.g. bare and bear)

see moresee less-

type of:

-

homonym

two words are homonyms if they are pronounced or spelled the same way but have different meanings

-

homonym

DISCLAIMER: These example sentences appear in various news sources and books to reflect the usage of the word ‘homophone’.

Views expressed in the examples do not represent the opinion of Vocabulary.com or its editors.

Send us feedback

EDITOR’S CHOICE

Look up homophone for the last time

Close your vocabulary gaps with personalized learning that focuses on teaching the

words you need to know.

Sign up now (it’s free!)

Whether you’re a teacher or a learner, Vocabulary.com can put you or your class on the path to systematic vocabulary improvement.

Get started

| Homophones | Definitions |

|---|---|

| Aisle and isle | Space between rows; small island or peninsula |

| Eye and I | Body part used for seeing; singular first-person pronoun |

| Bare and bear | Not covered; carry or support/large mammal |

| Be and bee | To exist; flying insect |

| Brake and break | Device used for slowing down; separate into pieces |

| Buy and by | To make a purchase; how something is done/moving past someone or something |

| Cell and sell | Small room/smallest structure of organisms; to cause the purchase of something |

| Cent and scent | Unit of money; a typically pleasant smell |

| Dear and deer | Regarded with affection; a hoofed, grazing animal |

| Flour and flower | Product made from wheat; brightly colored part of a plant |

| For and four | Who/what something relates to; one more than three/one less than five |

| Hear and here | To perceive sound; in, at, or to a certain point |

| Hole and whole | Hollow place in a solid body; something in its entirety |

| Know and no | To understand; a negative response |

| Meat and meet | Flesh of an animal; to join together |

| One and won | Lowest whole number; to achieve through effort |

| Peace and piece | State of security/order; a portion of something |

| Right and write | Correct; form letters, words, or sentences on a surface |

| Sea and see | Portion of the ocean that is partly surrounded by land; perceive with the eyes |

| Son and sun | Boy/man in relation to his parents; the star around which the Earth orbits |

| There, their, and they’re | In, at, or to a place or position; belonging to multiple people; they are |

| To, too, and two | Used in the infinitive form of a verb (to jump); also; greater than one/less than three |

| Weak and week | Not strong; period of seven days |

| Your and you’re | Belonging to the person being addressed; you are |

Homophones can sometimes have a different spelling and even a slightly different pronunciation. They should be mostly similar though. The phrase also applies to phrases, letters, and groups of letters that are pronounced the same as other versions of the same thing. It’s very common to find homophones used in poetry in order to create rhymes and/or to emphasize a sound or meaning.

Homophone pronunciation: haa-muh-fown

Explore Homophone

- 1 Definition and Explanation of Homophone

- 2 Homophones in Games and Puzzles

- 3 Types of Homophones

- 4 Common Homophones in English

- 5 Examples of Homophones in Literature

- 6 Why Do Writers Use Homophones?

- 7 Related Literary Terms

- 8 Other Resources

Definition and Explanation of Homophone

A homophone is a word that has the same sound as another word but a different definition. If the two words are spelled differently, which is often the case, they are also called heterotrophs. Another aspect of homophones that’s interesting to note is how different accents have different effects on the words. Some words might be homophonous in one accent and not in another. For example, “do” and “due” in an American accent are usually homophones but are not in many English accents. The same can be said of the words “forward” and “forward” in English and American accents. The word “homophone” is derived from the Greek meaning “same” and “voice” or “utterance.”

Homophones in Games and Puzzles

Homophones are sometimes used in puns, games, and puzzles, in order to suggest multiple meanings and deceive (usually for fun) the reader. These are sometimes also used in malapropisms where the wrong word is used to comic effect (although that’s not always the author’s intention).

Longer phrases also appear in word games and puzzles. They’re easily incorporated into jokes and pithy sayings. For example, “I moustache you a question” in which the word “moustache” is used rather than “must ask.”

Types of Homophones

- Homograph: homophones that have similar or identical spellings but different definitions.

- Homonym: words that have the same pronunciation but different meanings. For example: “Carrot, caret, and carat.”

- Heterograph: are homophones with different spellings but are pronounced the same way. For example: “bear” and “bare.”

- Oronym: words or phrases that have similar sounds. One word might have the same sound as a phrase. For example, “mustache” and “must ask.”

- Pseudo-homophone: words that are identical phonetically but one isn’t a real word.

Common Homophones in English

- Bear and bare

- Rose (a flower) and rose (past tense of “rise”)

- Carrot, caret, and carat

- Ad and add

- Arc and ark

- Ewe, yew, and you

- Faint and feint

- Licker and liquor

- Lean and lien

- Scull and skull

- Sear, seer, and sere

- Straight and strait

- Tale and tail

Examples of Homophones in Literature

Romeo and Juliet by William Shakespeare

In William Shakespeare’s poems and plays, readers can find a great number of homophones. One of the most commonly cited appears in the following lines of Romeo and Juliet.

Mercutio: “Nay, gentle Romeo, we must have you dance.”

Romeo:“Not I, believe me. You have dancing shoes. With nimble soles; I have a soul of lead. So stakes me to the ground I cannot move …

In the lines, Romeo uses the homophones “soul” and “sole.” He’s talking about the weight of his soul and his emotions while at the same time connecting it to his ability to dance and the “soles” of his shoes.

Read William Shakespeare’s poetry.

Faithless Sally Brown by Thomas Hood

In Hood’s ‘Faithless Sally Brown’ the poet includes homophones in the last stanza:

His death, which happen’d in his berth,

At forty-odd befell:

They went and told the sexton, and

The sexton toll’d the bell.

Here, he uses the words “toll’d” and “berth” and allude to their homophones “told” and “birth.” He uses “toll’d” to speak about the bell being rung after he died.

Read more of Thomas Hood’s poetry.

A Hymn to God the Father by John Donne

In ‘A Hymn to God the Father,’ Donne uses his own last name, which is also the last name of his wife, as homophones.

When Thou hast done,

Thou hast not done for I have more.

That at my death Thy Son

Shall shine as he shines now, and heretofore

And having done that, Thou hast done;

I fear no more.

In this passage, readers can also spot the use of “Son” rather than “sun” in the second line. This is a religious allusion and homophone. It’s not necessary for Donne to include the other version of the word, “sun” anywhere in the passage. Readers will be able to understand what he is trying to say without it.

Read more John Donne’s poems.

The Importance of Being Earnest by Oscar Wilde

Wilde’s best-known and well-loved play, The Importance of Being Earnest alludes to a homophone in its title and uses it a few times throughout the text. Here are a few lines.

On the contrary, Aunt Augusta, I’ve now realized for the first time in my life the vital Importance of Being Earnest[…]

I always told you, Gwendolen, my name was Ernest, didn’t I? Well, it is Ernest after all. I mean it naturally is Ernest.

In these passages from The Importance of Being Earnest, the characters use “earnest” and “Ernest,” the name, as homophones. Jack Earnest is talking to his Aunt and mocking his family. His father’s name makes him “Ernest” and “earnest” in a way that relates back to the broader storyline.

Explore Oscar Wilde’s poetry.

Why Do Writers Use Homophones?

Writers use homophones in order to create a humorous or clever effect in their writing. When words with two or more meanings are used, the reader is asked to stop and consider them and think for a moment about which meaning the writer has selected. They can be used in everyday life, and in the dialogue between characters, in order to prove one’s wit and make another laugh. Often, the best writers use them flawlessly and easily include them in descriptions, narrations, and dialogues.

- Ambiguity: a word or statement that has more than one meaning. If a phrase is ambiguous, it means multiple things.

- Analogy: an extensive comparison between one thing and another that is very different from it.

- Cadence: the natural rhythm of a piece of text, created through a writer’s selective arrangement of words, rhymes, and the creation of meter.

- Connotation: the feeling a writer creates through their word choice. It’s the idea a specific word or set of words evokes.

- Euphony: a literary device that refers to the musical, or pleasing, qualities of words.

Other Resources

- Read: Common Homophones List

- Watch: Learn 17 Homophone Pairs in English

- Read: 34 American Homophones Uncommon in British English

Definition of Homophone

A homophone can be defined as a word that, when pronounced, seems similar to another word, but has a different spelling and meaning. For example, the words “bear” and “bare” are similar in pronunciation, but are different in spelling as well as in meaning. Sometimes the words may have the same spelling, such as “rose,” the past tense of rise, and “rose,” the flower. Mostly, however, they are spelled differently, such as:

- carrot

- caret

- carat

In literature, homophones are used extensively in poetry and prose to make rhythmic effects, and to put emphasis on something. They are also used to create a multiplicity of meanings in a written piece.

Types of Homophone

There are five different types of homophone:

- Homograph – Some homophones are similar in spelling, but different in meanings. They are called homographs. For instance, “hail” meaning an ice storm, and “hail” meaning something that occurs in large numbers, such as “a hail of bullets.”

- Homonym – Some words have the same pronunciation but different meanings. These are called Homonyms. For instance, “cite,” “sight,” and “site.”

- Heterograph – Homophones that have different spellings but are pronounced in the same way are called heterographs. For instance, “write” and “right.”

- Oronym – Homophones that have multiple words or phrases, having similar sounds, are called oronyms. For instance, “ice cream” and “I scream.”

- Pseudo-homophone – Homophones that are identical phonetically are called pseudo-homophones. In this type of homophone, one of the pair of words is not a real word, such as “groan” and “grone.”

Examples of Homophone in Literature

Example #1: Where Truth’s Wind Blew (By Venicebard)

“Sole owner am I of this sorry soul …

pour out corruption’s slag from every pore —

whole slates scrape clean! they leave no gaping hole.

Role that I’ve played, loose grip! while back I roll,

or dodge each wave, or with firm grip on oar

bore through this sea, snout down, just like the boar …”

This poem is filled with examples of homophone, which are marked in bold. They create a humorous effect in the poem through their same pronunciations but altogether different meanings.

Example #2: A Hymn to God the Father (By John Donne)

“When Thou hast done,

Thou hast not done for I have more.

That at my death Thy Son

Shall shine as he shines now, and heretofore

And having done that, Thou hast done;

I fear no more.”

John Done has used the name of his wife Anne and his own name Donne as homophones. In addition, he makes use of the word “son” instead of “sun,” to refer to Christ. They are also homophones.

Example #3: The Importance of Being Earnest (By Oscar Wilde)

“On the contrary, Aunt Augusta, I’ve now realized for the first time in my life the vital Importance of Being Earnest …”

“I always told you, Gwendolen, my name was Ernest, didn’t I? Well, it is Ernest after all. I mean it naturally is Ernest. “

In these excerpts, Oscar Wilde used the word earnest as a homophone. Here, Jack Earnest is talking to his Aunt Augusta and mocks his family. Jack finds out that his father’s name makes him really earnest.

Example #4: Romeo and Juliet (By William Shakespeare)

MERCUTIO:

“Nay, gentle Romeo, we must have you dance.”ROMEO:

“Not I, believe me. You have dancing shoes. With nimble soles; I have a soul of lead. So stakes me to the ground I cannot move …”

Some of Shakespeare’s famous literary pieces are rich with homophone examples. One of which is the above excerpt where he uses the words “sole” and “soul” as homophones. Romeo talks about soles of his shoes, and the soul of his heart, which is heavy with sorrow.

Example #5: Richard III (By William Shakespeare)

“Now is the winter of our discontent … made glorious summer by this Son of York.”

Here, Shakespeare uses two words similar in pronunciation, “sun” and “son,” which are homophones. The Duke of York has a son named Edward, who is also taken as a sun whose rising power would create trouble for Richard.

Function of Homophone

The purpose of homophones in literature is to create humorous effect by using words that have two or more meanings. In everyday life, these words are employed intentionally in witty remarks. In addition, these give meaning to a literary piece of work, and writers reveal the ingenuity of their characters through the use of homophones.

Definition of Homophone

A homophone is a word that is pronounced in the same way as another word but has a different meaning, and usually a different spelling. For example, the words “sea” and “see” constitute a homophone pair because they are pronounced the same way but have different meanings and different spellings. Note that some words count as homophones in one person’s accent, while in another person’s accent the words sound different. For example, for some people “merry,” “marry,” and “Mary” are all pronounced exactly the same, while for others there are three separate vowel sounds.

The word homophone comes from the Greek words homo- (ὁμο‑) and phōnḗ (φωνή), which mean “same” and “voice” or “utterance,” respectively. The definition of homophone is very similar to that of homonym, which also refers to a word that is pronounced the same way, but which must be spelled in the same way as well. Therefore, every homonym is a homophone, while not every homophone is a homonym.

Difference Between Homophone, Homograph, and Homonym

Every example of homophone pairs is pronounced the same way, while every homograph pair is spelled in the same way. A homonym pair must be pronounced in the same way as well as spelled the same way. To qualify as a homograph, a homophone, or a homonym the words in question must have different meanings; they often have different root words as well.

A homophone pair that is spelled differently can also be further classified as a heterograph pair.

Common Examples of Homophone

There are many different examples of homophone pairs in English. There are also over 80 homophone triples, 24 homophone quadruples, and a few examples of homophonic groups that have five, six, and even seven words.

- Homophone pairs: Flower, Flour; Deer, Dear; Cot, Caught; Maid, Made; Stake, Steak; Sale, Sail; Faint, Feint; Great, Grate; Days, Daze; Beach, Beech; Creak, Creek; Grease, Greece; Minor, Miner; Knight, Night; Mode, Mowed; Yolk, Yoke; Aloud, Allowed; Witch, Which

- Homophone triples: Pair, Pare, Pear; To, Two, Too; Wail, Whale, Wale; Rood, Rude, Rued; Rapped, Rapt, Wrapped; Coward, Cowherd, Cowered; Chord, Cord, Cored; Bald, Balled, Bawled; Aisle, I’ll, Isle; Ade, Aid, Aide; Frees, Frieze, Freeze; Knead, Kneed, Need; Knot, Naught, Not; Reign, Rain, Rein

- Homophone quadruples: Gnu, Knew, New, Nu; Prays, Preys, Praise, Prase; Metal, Meddle, Mettle, Medal; Carat, Caret, Carrot, Karat; Sense, Cents, Scents, Cense

- Homophone quintuplet: Seau, Sew, So, Soe, Sow

There are many pun examples in English that depend on homophonic words. Here are some examples:

- When she saw her first strands of gray hair, she thought she’d dye.

- Once you’ve seen one shopping center you’ve seen a mall. (a mall=‘em all)

- Those who jump off a Paris bridge are in Seine. (in Seine=insane)

There are also many longer jokes in which the punch line depends on a homophonic pun, such as the following:

A string walks into a bar with a few friends and orders a beer. The bartender says, “I’m sorry, but we don’t serve strings here.”

The string goes back to his table. He ties himself in a loop and messes up the top of his hair. He walks back up to the bar and orders a beer.

The bartender squints at him and says, “Hey, aren’t you a string?”

The string says, “Nope, I’m a frayed knot.”

Significance of Homophone in Literature

When authors choose to use homophones in literature, it’s usually to create a pun. Though homophones do not have the same meaning, when they are heard aloud there can be a brief moment of confusion as the audience works out the meaning of the word from the context. Thus, homophone examples are especially popular in drama, because the audience will hear the word spoken and thus hear the pun intended by the different meanings of the homophonic words.

Examples of Homophone in Literature

Example #1

SAMPSON: Gregory, o’ my word, we’ll not carry coals.

GREGORY: No, for then we should be colliers.

SAMPSON: I mean, an we be in choler, we’ll draw.

GREGORY: Ay, while you live, draw your neck out o’ the collar.

(Romeo and Juliet by William Shakespeare)

William Shakespeare particularly loved including homophone examples in his works to show clever wordplay. In the above excerpt from Romeo and Juliet, the characters of Sampson and Gregory come up with three homophones: collier, choler, and collar. They know they are being witty, and choose their rebukes just to further the game of words. Their back-and-forth is not necessarily full of sense, but instead makes use of this homophone triple for humor’s sake.

Example #2

DON PEDRO: Why, how now, Count, wherefore are you sad?

CLAUDIO: Not sad, my lord.

DON PEDRO: How then, sick?

CLAUDIO: Neither, my lord.

BEATRICE: The Count is neither sad, nor sick, nor merry, nor well, but civil count, civil as an orange, and something of that jealous complexion.

(Much Ado About Nothing by William Shakespeare)

In Much Ado About Nothing, William Shakespeare uses a clever play on words that might not be quite as obvious as the previous example. Beatrice says the Count is “civil as an orange.” In this case, the word “civil” is suppose to be a homophone for the Spanish city of Seville, which is where the majority of oranges came from in Shakespeare’s day. Thus, his audiences would hear the somewhat strange simile of “civil as an orange,” and understand it to be a homophonic pun. Indeed, the joke goes a bit further because oranges from Seville were known to be bitter, and thus Beatrice is implying that the Count is feeling bitter.

Example #3

His death, which happen’d in his berth,

At forty-odd befell:

They went and told the sexton, and

The sexton toll’d the bell.

(“Faithless Sally Brown” by Thomas Hood)

In this final stanza from his poem “Faithless Sally Brown,” Thomas Hood uses two homophone examples. The man in this poem is a sailor, and thus when Hood refers to “his berth,” he is talking about the man’s bed on his ship. However, it is also clearly a homophonic pun which hearkens back to the word “birth” and therefore the line is clever because it contains a seeming juxtaposition between the man’s death and birth.

Example #4

ROSENCRANTZ: Oh yes, it’s dark for day.

GUILDENSTERN: We must have gone north, of course.

ROSENCRANTZ: Off course?

GUILDENSTERN: Land of the midnight sun, that is.

ROSENCRANTZ: Of course….I think it’s getting light.

GUILDENSTERN: Not for night.

ROSENCRANTZ: This far north.

GUILDENSTERN: Unless we’re off course.

ROSENCRANTZ: Of course.

(Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are Dead by Tom Stoppard)

The above excerpt from Tom Stoppard’s absurdist play Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are Dead is not quite an example of homophone because “of course” and “off course” are usually not pronounced the same way. However, the characters mishear each other, making the two phrases functional homophones in this passage. Stoppard’s play contains many such exchanges that show the limits of communication and the consequences of miscommunication. Therefore, this passage is humorous to the audience who likely can hear the difference between the two phrases and note that the two characters are not understanding the difference.

Test Your Knowledge of Homophone

1. Which of the following statements is the correct homophone definition?

A. A word which has the same pronunciation but a different meaning as another word.

B. A word which has the same spelling but a different meaning as another word.

C. A word which has the same spelling and same pronunciation as another word.

| Answer to Question #1 | Show |

|---|---|

2. Choose the homophone example from the following pairs of words:

A. Stare/Steer

B. Bear/Bare

C. Mayor/Mayer

| Answer to Question #2 | Show |

|---|---|

3. Which of the following sets of lines from Gloucester’s speech in William Shakespeare’s Richard III contains an example of homophone?

A.

Now is the winter of our discontent

Made glorious summer by this sun of York;

B.

And all the clouds that lour’d upon our house

In the deep bosom of the ocean buried.

C.

Now are our brows bound with victorious wreaths;

Our bruised arms hung up for monuments;

| Answer to Question #3 | Show |

|---|---|

A homophone is a word that is pronounced the same as another word but differs in meaning. The words may be spelled the same, such as «rose» (flower) and «rose» (past tense of «rise»), or differently, such as «carat», «caret», and «carrot», or «two» and «too», or «know» and «no». A homophone is a type of homonym, although sometimes «homonym» is used to refer only to homophones that have the same spelling but different meanings. The term may also be used to apply to units shorter than words, such as letters or groups of letters that are pronounced the same as another letter or group of letters.

The prefix, «homo» means the «same». «Phone» means «sound». «Graph» in homograph means «writing».

Homophones are often used to create puns and to deceive the reader (as in crossword puzzles) or to suggest multiple meanings. The last usage is common in poetry and creative literature. An example of this is seen in Dylan Thomas’s radio play «Under Milk Wood»: «The shops in mourning» where «mourning» can be heard as «mourning» or «morning». Another vivid example is Thomas Hood’s use of ‘birth’ & ‘berth’ and «told’ & ‘toll’d’ (tolled) in his poem «Faithless Sally Brown»:

:His death, which happen’d in his berth,:At forty-odd befell::They went and told the sexton, and:The sexton toll’d the bell.

Homophones in the context of word games are also known as «oronyms». This term was coined by Gyles Brandreth and first published in his book «The Joy of Lex» (1980), and it was used in the BBC programme «Never Mind the Full Stops», which also featured Brandreth as a guest.

Examples of «oronyms» (which may only be true homophones in certain dialects of English) include :’mint spy’ vs ‘mince pie’; :’ice cream’ vs. ‘I scream’:’stuffy nose’ vs. ‘stuff he knows’;:’euthanasia’ vs. ‘youth in Asia’;:’i.c.u.’ vs. ‘I see you’.:’depend’ vs. ‘deep end’:’the sky’ vs. ‘this guy’:’four candles’ vs. ‘fork handles’:’insinuate’ vs. ‘in sin you ate’:’Sand which is there’ vs. Sandwiches there’Two oronyms appear in «Ana’s Song (Open Fire)» by Silverchair. While they initially sound like mondegreens, reading the lyrics will reveal that this is not the case. The first line of the song, «Please die Ana, for as long as you’re here we’re not», also sounds very much like «Please Diana, …», which confuses people into believing that «Ana» is a person, when really it is just a nickname for anorexia. The next verse is «And Ana wrecks your life, like an anorexia life», which is another oronym that proves «ana’s» real meaning.

American comedian Jeff Foxworthy frequently uses oronyms in his Appalachian routine. Notable examples include, «Initiate: My wife ate two sandwiches, «initiate» (and then she ate) a bag o’ tater chips.» and «Mayonnaise: «Mayonnaise» (Man, there is) a lot of people here tonight.»

Mad Gab is a team oronym solving game.

Use in psychological research

Pseudo-homophones

Pseudo-homophones are non-words that are phonetically identical to a word. Pseudo-homophone pairs are pairs of phonetically identical letter strings where one string is a word and the other is a non-word. For example, groan/grone and crane/crain are pseudo-homophone pairs, whereas plane/plain is a homophone pair since both letter strings are recognised words. Both types of pairs are used in lexical decision tasks to investigate word recognition.

Use as ambiguous information

Homophones where one spelling is of a threatening nature and one is not («e.g.» slay/sleigh, war/wore) have been used in studies of anxiety as a test of cognitive models that those with high anxiety tend to interpret ambiguous information in a threatening manner. See Mogg K, Bradley BP, Miller T, Potts H, Glenwright J, Kentish J (1994). Interpretation of homophones related to threat: Anxiety or response bias effects? «Cognitive Therapy and Research», 18(5), 461-77.

Dreams

Homophones also appear sometimes in dreams; see dream pun.

External links

* [http://www.cooper.com/alan/homonym_list.html Alan Cooper’s Homonym List (actually homophones, not homonyms, as he himself explains)]

* [http://assortedmaterial.googlepages.com/EnglishHomonymsHomophones.html Homonyms and Homophones] — a basic but useful list

*cite web |url=http://www.bifroest.demon.co.uk/misc/homophones-list.html |title=List of 441 British-English homophones |work=Ian Miller |accessmonthday=February 15 |accessyear=2008

Wiktionary

*

*

Wikimedia Foundation.

2010.