Table of Contents

1

Pose a question; introduce a character; set a scene; lure them in with enticing prose; lay a clue to the direction the novel is going to take; plant the seeds of an idea; create a dramatic impression; give them a taste of action.

What makes a good first line?

The first lines of a novel or short story must grab the reader’s attention, enticing them to continue past the first page and continue reading. The first sentence provides you with an opportunity to showcase your writing style, introduce your main character, or establish the inciting incident of your narrative.

How do I start just writing?

8 Great Ways to Start the Writing Process

- Start in the Middle. If you don’t know where to start, don’t bother deciding right now. …

- Start Small and Build Up. …

- Incentivize the Reader. …

- Commit to a Title Up Front. …

- Create a Synopsis. …

- Allow Yourself to Write Badly. …

- Make Up the Story as You Go. …

- Do the Opposite.

How do I start my book?

How to Write a Good Hook & Start Your Novel with a Bang!

- Startle readers with the first line. …

- Begin at a life-changing moment. …

- Create intrigue about the characters. …

- Use a setting as the inciting incident. …

- Up the stakes within the first few pages. …

- Introduce something ominous right away. …

- Set the mood.

How do you write a good story?

10 ways to make a good story succeed:

- Give your story strong dramatic content.

- Vary rhythm and structure in your prose.

- Create believable, memorable characters.

- Make the important story sections effective.

- Deepen your plot with subplots.

- Make every line of dialogue count.

- Add what makes a good story (immersive setting)

How do you start a short story example?

5 Ways to Start a Short Story

- Hook readers with excitement. …

- Introduce the lead character. …

- Start with dialogue. …

- Use memories. …

- Begin with a mystery.

How do you write a story example?

Brainstorm to find an interesting character or plot.

The spark for your story might come from a character you think would be interesting, an interesting place, or a concept for a plot. Write down your thoughts or make a mind map to help you generate ideas. Then, pick one to develop into a story.

How do you start a scene?

To create an action launch:

- Get Straight to the Action. …

- Hook the Reader With Big or Surprising Actions. …

- Be Sure That the Action Is True to Your Character. …

- Act First, Think Later. …

- Save Time by Beginning With Summary. …

- Communicate Necessary Information to the Reader Before the Action Kicks in.

How do I start my first chapter?

An ideal first chapter should do the following things:

- 1) Introduce the main character. …

- 2) Make us care enough to go on a journey with that character. …

- 3) Set tone. …

- 4) Let us know the theme. …

- 5) Let us know where we are. …

- 6) Introduce the antagonist. …

- 7) Ignite conflict.

How do you start a chapter?

5 Ways to Start a Chapter and Keep Your Readers Engaged

- Begin with action. When in doubt, begin the opening scene of a new chapter with action. …

- Try a new point of view. …

- Reveal new information. …

- Include sensory details. …

- Jump through time.

How can I make a story in English?

How to Write a Story in English

- Pick a theme. Base your story around something you’ve already learned in English. …

- Make a plan. No matter how short you intend your story to be, make a quick plan beforehand. …

- Pick a point-of-view. …

- Write the actual story in English. …

- Keep it simple. …

- Finish it.

What are good words to start a sentence?

Good sentence starters to establish cause and effect

- As a result . . .

- Accordingly . . .

- Consequently . . .

- Due to . . .

- For this reason . . .

- Hence . . .

- Therefore . . .

- This means that . . .

How do I find my writing style?

Follow these general guidelines to help you find that style and develop your writing voice and tone:

- Be original. …

- Use your life experiences. …

- Be present in your writing. …

- Have an adaptable voice. …

- Step out of your comfort zone. …

- Read other authors. …

- Write often. …

- Hone your craft.

How do you write a good writing style?

8 Tips for Improving Your Writing Style

- Be direct in your writing. Good writing is clear and concise. …

- Choose your words wisely. …

- Short sentences are more powerful than long sentences. …

- Write short paragraphs. …

- Always use the active voice. …

- Review and edit your work. …

- Use a natural, conversational tone. …

- Read famous authors.

What’s a good story plot?

Top 10 Story Ideas

- Tell the story of a scar.

- A group of children discover a dead body.

- A young prodigy becomes orphaned.

- A middle-aged woman discovers a ghost.

- A woman who is deeply in love is crushed when her fiancé breaks up with her.

- A talented young man’s deepest fear is holding his life back.

How do you start a first person story?

7 Tips for Beginning a Story in First-Person POV

- Establish a clear voice. …

- Start mid-action. …

- Introduce supporting characters early. …

- Use the active voice. …

- Decide if your narrator is reliable. …

- Decide on a tense for your opening. …

- Study first-person opening lines in literature.

How do you write a school story?

How to Write a Short Story: The Complete Guide in 9 Steps

- Start With an Idea. The first step to writing a short story is to have an idea. …

- Pick a Point of View. Is your character telling the story? …

- Learn About Your Character. …

- Avoid Character Cliches. …

- Give Your Character Conflict. …

- Show, Don’t Tell.

What’s a short story example?

What is an example of a short story? A short story is a fictional story which is more than 1,600 words and less than 20,000. One famous example of a short story is Anton Chekhov’s “Gooseberries” written in 1898.

How do you title a short story?

Titles of individual short stories and poems go in quotation marks. The titles of short story and poetry collections should be italicized. For example, “The Intruder,” a short story by Andre Dubus appears in his collection, Dancing After Hours.

What is a good opening scene?

Your opening scene should include information that either foreshadows or leads to the inciting incident. There needs to be information relating to your main character’s journey, and how that journey lands him or her into this particular setting.

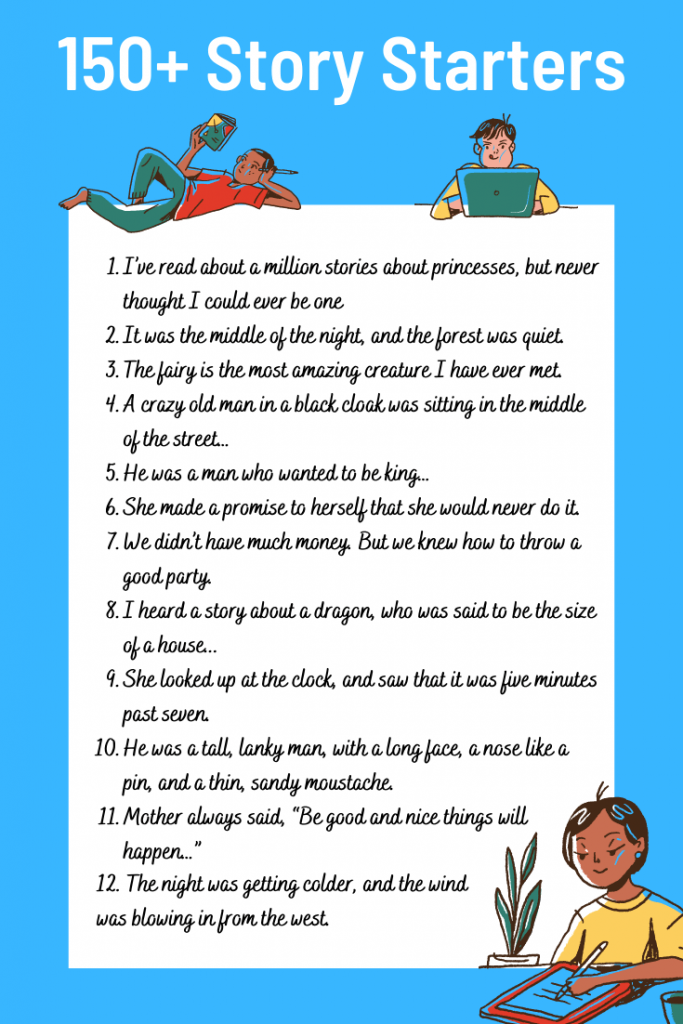

150+ Story Starters: Creative Sentences To Start A Story

June 26, 2022

The most important thing about writing is finding a good idea. You have to have a great idea to write a story. You have to be able to see the whole picture before you can start to write it. Sometimes, you might need help with that. Story starters are a great way to get the story rolling. You can use them to kick off a story, start a character in a story or even start a scene in a story.

When you start writing a story, you need to have a hook. A hook can be a character or a plot device. It can also be a setting, something like “A young man came into a bar with a horse.” or a setting like “It was the summer of 1969, and there were no cell phones.” The first sentence of a story is often the hook. It can also be a premise or a situation, such as, “A strange old man in a black cloak was sitting on the train platform.”

Story starters are a way to quickly get the story going. They give the reader a place to start reading your story. Some story starters are obvious, and some are not. The best story starters are the ones that give the reader a glimpse into the story. They can be a part of a story or a part of a scene. They can be a way to show the reader the mood of a story. If you want to start a story, you can use a simple sentence. You can also use a question or an inspirational quote. In this post, we have listed over 150 story starters to get your story started with a bang! A great way to use these story starters is at the start of the Finish The Story game.

Click the ‘Random’ button to get a random story starter.

If you want more story starters, check out this video on some creative story starter sentences to use in your stories:

Here is a list of good sentences to start a story with:

- I’ve read about a million stories about princesses but never thought I could ever be one.

- There was once a man who was very old, but he was wise. He lived for a very long time, and he was very happy.

- What is the difference between a man and a cat? A cat has nine lives.

- In the middle of the night, a boy is running through the woods.

- It is the end of the world.

- He knew he was not allowed to look into the eyes of the princess, but he couldn’t help himself.

- The year is 1893. A young boy was running away from home.

- What if the Forest was actually a magical portal to another dimension, the Forest was a portal to the Otherworld?

- In the Forest, you will find a vast number of magical beings of all sorts.

- It was the middle of the night, and the forest was quiet. No bugs or animals disturbed the silence. There were no birds, no chirping.

- If you wish to stay in the Forest, you will need to follow these rules: No one shall leave the Forest. No one shall enter. No one shall take anything from the Forest.

- “It was a terrible day,” said the old man in a raspy voice.

- A cat is flying through the air, higher and higher, when it happens, and the cat doesn’t know how it got there, how it got to be in the sky.

- I was lying in the woods, and I was daydreaming.

- The Earth is a world of wonders.

- The fairy is the most amazing creature I have ever met.

- A young girl was sitting on a tree stump at the edge of a river when she noticed a magical tree growing in the water.

- My dancing rat is dressed in a jacket, a tie and glasses, which make him look like a person.

- In the darkness of the night, I am alone, but I know that I am not.

- Owls are the oldest, and most intelligent, of all birds.

- My name is Reyna, and I am a fox.

- The woman was drowning.

- One day, he was walking in the forest.

- It was a dark and stormy night…

- There was a young girl who could not sleep…

- A boy in a black cape rode on a white horse…

- A crazy old man in a black cloak was sitting in the middle of the street…

- The sun was setting on a beautiful summer day…

- The dog was restless…”

- There was a young boy in a brown coat…

- I met a young man in the woods…

- In the middle of a dark forest…

- The young girl was at home with her family…

- There was a young man who was sitting on a …

- A young man came into a bar with a horse…

- I have had a lot of bad dreams…

- He was a man who wanted to be king…

- It was the summer of 1969, and there were no cell phones.

- I know what you’re thinking. But no, I don’t want to be a vegetarian. The worst part is I don’t like the taste.

- She looked at the boy and decided to ask him why he wasn’t eating. She didn’t want to look mean, but she was going to ask him anyway.

- The song played on the radio, as Samual wiped away his tears.

- This was the part when everything was about to go downhill. But it didn’t…

- “Why make life harder for yourself?” asked Claire, as she bit into her apple.

- She made a promise to herself that she would never do it.

- I was able to escape.

- I was reading a book when the accident happened.

- “I can’t stand up for people who lie and cheat.” I cried.

- You look at me and I feel beautiful.

- I know what I want to be when I grow up.

- We didn’t have much money. But we knew how to throw a good party.

- The wind blew on the silent streets of London.

- What do you get when you cross an angry bee and my sister?

- The flight was slow and bumpy. I was half asleep when the captain announced we were going down.

- At the far end of the city was a river that was overgrown with weeds.

- It was a quiet night in the middle of a busy week.

- One afternoon, I was eating a sandwich in the park when I spotted a stranger.

- In the late afternoon, a few students sat on the lawn reading.

- The fireflies were dancing in the twilight as the sunset.

- In the early evening, the children played in the park.

- The sun was setting and the moon was rising.

- A crowd gathered in the square as the band played.

- The top of the water tower shone in the moonlight.

- The light in the living room was on, but the light in the kitchen was off.

- When I was a little boy, I used to make up stories about the adventures of these amazing animals, creatures, and so on.

- All of the sudden, I realized I was standing in the middle of an open field surrounded by nothing but wildflowers, and the only thing I remembered about it was that I’d never seen a tree before.

- It’s the kind of thing that’s only happened to me once before in my life, but it’s so cool to see it.

- They gave him a little wave as they drove away.

- The car had left the parking lot, and a few hours later we arrived home.

- They were going to play a game of bingo.

- He’d made up his mind to do it. He’d have to tell her soon, though. He was waiting for a moment when they were alone and he could say it without feeling like an idiot. But when that moment came, he couldn’t think of anything to say.

- Jamie always wanted to own a plane, but his parents were a little tight on the budget. So he’d been saving up to buy one of his own.

- The night was getting colder, and the wind was blowing in from the west.

- The doctor stared down at the small, withered corpse.

- She’d never been in the woods before, but she wasn’t afraid.

- The kids were having a great time in the playground.

- The police caught the thieves red-handed.

- The world needs a hero more than ever.

- Mother always said, “Be good and nice things will happen…”

- There is a difference between what you see and what you think you see.

- The sun was low in the sky and the air was warm.

- “It’s time to go home,” she said, “I’m getting a headache.”

- It was a cold winter’s day, and the snow had come early.

- I found a wounded bird in my garden.

- “You should have seen the look on my face.”

- He opened the door and stepped back.

- My father used to say, “All good things come to an end.”

- The problem with fast cars is that they break so easily.

- “What do you think of this one?” asked Mindy.

- “If I asked you to do something, would you do it?” asked Jacob.

- I was surprised to see her on the bus.

- I was never the most popular one in my class.

- We had a bad fight that day.

- The coffee machine had stopped working, so I went to the kitchen to make myself a cup of tea.

- It was a muggy night, and the air-conditioning unit was so loud it hurt my ears.

- I had a sleepless night because I couldn’t get my head to turn off.

- I woke up at dawn and heard a horrible noise.

- I was so tired I didn’t know if I’d be able to sleep that night.

- I put on the light and looked at myself in the mirror.

- I decided to go in, but the door was locked.

- A man in a red sweater stood staring at a little kitten as if it was on fire.

- “It’s so beautiful,” he said, “I’m going to take a picture.”

- “I think we’re lost,” he said, “It’s all your fault.”

- It’s hard to imagine what a better life might be like

- He was a tall, lanky man, with a long face, a nose like a pin, and a thin, sandy moustache.

- He had a face like a lion’s and an eye like a hawk’s.

- The man was so broad and strong that it was as if a mountain had been folded up and carried in his belly.

- I opened the door. I didn’t see her, but I knew she was there.

- I walked down the street. I couldn’t help feeling a little guilty.

- I arrived at my parents’ home at 8:00 AM.

- The nurse had been very helpful.

- On the table was an array of desserts.

- I had just finished putting the last of my books in the trunk.

- A car horn honked, startling me.

- The kitchen was full of pots and pans.

- There are too many things to remember.

- The world was my oyster. I was born with a silver spoon in my mouth.

- “My grandfather was a World War II veteran. He was a decorated hero who’d earned himself a Silver Star, a Bronze Star, and a Purple Heart.

- Beneath the menacing, skeletal shadow of the mountain, a hermit sat on his ledge. His gnarled hands folded on his gnarled knees. His eyes stared blankly into the fog.

- I heard a story about a dragon, who was said to be the size of a house, that lived on the top of the tallest mountain in the world.

- I was told a story about a man who found a golden treasure, which was buried in this very park.

- He stood alone in the middle of a dark and silent room, his head cocked to one side, the brown locks of his hair, which were parted in the middle, falling down over his eyes.

- Growing up, I was the black sheep of the family. I had my father’s eyes, but my mother’s smile.

- Once upon a time, there was a woman named Miss Muffett, and she lived in a big house with many rooms.

- When I was a child, my mother told me that the water looked so bright because the sun was shining on it. I did not understand what she meant at the time.

- The man in the boat took the water bottle and drank from it as he paddled away.

- The man looked at the child with a mixture of pity and contempt.

- An old man and his grandson sat in their garden. The old man told his grandson to dig a hole.

- An old woman was taking a walk on the beach. The tide was high and she had to wade through the water to get to the other side.

- She looked up at the clock and saw that it was five minutes past seven.

- The man looked up from the map he was studying. “How’s it going, mate?”

- I was in my room on the third floor, staring out of the window.

- A dark silhouette of a woman stood in the doorway.

- The church bells began to ring.

- The moon rose above the horizon.

- A bright light shone over the road.

- The night sky began to glow.

- I could hear my mother cooking in the kitchen.

- The fog began to roll in.

- He came in late to the class and sat at the back.

- A young boy picked up a penny and put it in his pocket.

- He went to the bathroom and looked at his face in the mirror.

- It was the age of wisdom and the age of foolishness. We once had everything and now we have nothing.

- A young man died yesterday, and no one knows why.

- The boy was a little boy. He was not yet a man. He lived in a house in a big city.

- They had just returned from the theatre when the phone rang.

- I walked up to the front of the store and noticed the neon sign was out.

- I always wondered what happened to Mary.

- I stopped to say hello and then walked on.

- The boy’s mother didn’t want him to play outside…

- The lights suddenly went out…

- After 10 years in prison, he was finally out.

- The raindrops pelted the window, which was set high up on the wall, and I could see it was a clear day outside.

- My friend and I had just finished a large pizza, and we were about to open our second.

- I love the smell of the ocean, but it never smells as good as it does when the waves are crashing.

- They just stood there, staring at each other.

- A party was in full swing until the music stopped.

For more ideas on how to start your story, check out these first-line writing prompts. Did you find this list of creative story starters useful? Let us know in the comments below!

Marty the wizard is the master of Imagine Forest. When he’s not reading a ton of books or writing some of his own tales, he loves to be surrounded by the magical creatures that live in Imagine Forest. While living in his tree house he has devoted his time to helping children around the world with their writing skills and creativity.

It happens to the best of us: you open a new word document, you’re faced with the many possibilities that a story can take, and then you realize you don’t know how to start a story. Or you do know, but you’re not sure how to start this story. Or you know exactly what this story is supposed to be, but you can’t seem to find the first words.

Whatever the case, there are many good ways to start a story, but simply starting somewhere can prove challenging. How do other writers do it?

This article tackles the tricky concept of how to start a story. We’ll take a look at different strategies, examples, and ideas you can use to improve your own work. And, we’ll look at what not to do as you start a new draft of your story.

In order to understand how to start a story, we should first examine what your story’s beginning must accomplish.

Check Out Our Fiction Writing Courses!

Getting Started Marketing Your Work

with Gloria Kempton

April 12th, 2023

Solve the mystery of marketing and get your work out there in front of readers in this 4-week online class taught by Instructor Gloria Kempton.

What Should the Start of a Story Accomplish?

No matter where your story begins, it needs to accomplish a few things for the reader. There are many ways to start a story, but without a certain amount of context and intrigue, the reader will fail to understand what the story is about or where the story is headed.

Most stories, regardless of length, will establish the following items early on:

Characters

Who are the main characters of your story? Of course, many more characters may be introduced as the story progresses, but we should know early on who our protagonist is, as well as some relevant relationships that make the story unfold.

Try to give the reader a peek into your protagonist’s psyche right away. Learn more about this at our article on Character Development.

Try to give the reader a peek into your protagonist’s psyche right away.

Setting

Where is your story taking place? Often, the story begins somewhere safe, where the protagonist hasn’t yet been forced from their home. Or, if your protagonist doesn’t go on a physical journey, they still go on an emotional one—a journey in which their home begins to feel a lot less like home.

Establishing the protagonist’s relationship to their setting helps define where the story exists and where the story will go. Learn more at our article on Five Functions of Setting in Literature.

Establishing the protagonist’s relationship to their setting helps define where the story exists and where the story will go.

Point of View

Who is telling the story, and from what vantage point? Is it the protagonist themselves, or a close friend of the protagonist, or some distant third party observer?

A story’s points of view can shift over time, but we should know right away “who’s holding the camera” as the story unfolds before us. Our article on Narrative Point of View explains this in detail.

We should know right away “who’s holding the camera” as the story unfolds before us.

Mood

The mood of a story refers to the general emotional atmosphere conveyed by the work itself. It is both the feelings expressed in the work and the feelings that the writer wishes to evoke from the reader.

Stories are often defined by specific moods, and although the mood of a story is complex and shifts over time, it should be established right away through the author’s style and word choice. Here’s a succinct write-up on how literature establishes mood.

Although the mood of a story is complex and shifts over time, it should be established right away through the author’s style and word choice.

Conflict

Your story starts where the conflict starts. No, many stories don’t have an inciting incident within the first paragraph. But, your story must establish early on the cause for the story’s existence: the conflicts, disagreements, and contradictions that the story will develop and (maybe) resolve.

Your story starts where the conflict starts.

As we examine “how to start a story” examples, take note of how each story start establishes character, setting, mood, conflict, and point of view. Other elements in story writing, like plot, style, and themes, are developed over time, as are these initial 5 elements. You can learn more about working with the elements of fiction at our article The Art of Storytelling.

How to Start a Story: Examples from Literature

Every story requires its own unique beginning. The ideas we list below can help you decide where you jumpstart your story, but pay careful consideration to the intent of your opening lines. Are you trying to surprise the reader? To situate them in the story’s setting? Or, perhaps, to baffle the reader while also generating intrigue?

Here’s 12 ways to start a story, with examples from published works of literature.

1. How to Start a Story: Dialogue

Readers are nosy: they like being involved in the social lives of the story’s characters. Dropping the reader in the middle of a conversation will certainly pique the reader’s interest, especially if that conversation itself is interesting.

One such story that drops the reader in the middle of dialogue is “Never a Gentle Master” by Brittany N. Williams.

“Ain’t no good coming of messin’ in other folks’ business.” Madear’s voice broke through the silence of the workroom. “Especially not Qual’s.” Kae jerked, and the dried lavender cracked in her hand, spilling the remnants of fragrant purple flowers all over the table. The venom in her grandma’s voice as she spat out the name shook her but she didn’t dare look up from her work.

“The man’s meddling with death magic,” Momma said to Madear as she strode into the workshop, “and that right there makes it our business.”

By starting with dialogue, this story drops us in the middle of the tension: meddling, death magic, and workroom gossip. Dialogue writing has its own challenges; learn how to start a story with proper dialogue at our article How to Write Dialogue in a Story.

Note: some writers and publishers don’t like this method of starting a story, because we don’t know anything about the character before hearing them speak. If you open your story with dialogue, that dialogue should intrigue the reader, introduce conflict, and offer some characterization. Show us through the character’s word choice who the character is.

2. How to Start a Story: Conflict

Conflict is the lifeblood of a story. Without conflict—man vs. man, man vs. nature, man vs. self, etc.—there is little else propelling the story from beginning to end.

Of course, conflict doesn’t have to be an all-out war. Yes, dueling wizards and angry gods counts as conflict. But, it can also be something far more everyday.

In “A Duck Walks into a Bar” by Joshua Bohnsack, for example, the conflict is a child’s struggle to understand jokes—and his parent’s struggle to teach him about the world.

My son is trying to write a joke. He thinks this will help him make friends and let people know he’s friendly. He wants me to tell him if the jokes are funny. He doesn’t know whether I am being sincere most of the time, so he asks me to clarify.

He says, “Mommy. What does the scarecrow say to the pigeon?”

I tell him I don’t know.

“‘Just leave me alone.’”

I tell him I don’t think that’s a funny joke.

By starting with conflict, the author wastes no time getting to the heart of what they’re writing about.

3. How to Start a Story: Setting and Mood

Stories transport us to faraway places—places we’ve never visited, times long past, and settings we can only dream about. Every character has a relationship to their setting, and that relationship often lends itself to the mood of the story: the overall feeling, aesthetic, and emotional landscape of the work.

Starting the story with its setting can pull the reader in and establish a compelling mood. In “Fjord of Killary” by Kevin Barry, the author does just that.

So I bought an old hotel on the fjord of Killary. It was set hard by the harbor wall, with Mweelrea Mountain across the water, and disgracefully gray skies above. It rained two hundred and eighty-seven days of the year, and the locals were given to magnificent mood swings. On the night in question, the rain was particularly violent—it came down like handfuls of nails flung hard and fast by a seriously riled sky god. I was at this point eight months in the place and about convinced that it would be the death of me.

“It’s end-of-the-fucking-world stuff out there,” I said.

By giving the reader details about the place, its people, and its bleakness, the author sets the mood of the entire story. Learn more about developing settings at our article What is the Setting of a Story?

4. How to Start a Story: Backstory

Backstory refers to events that have happened prior to the story’s present-day action. While backstory isn’t necessary to follow the story’s plot, it is essential for understanding specific pieces of information.

Backstory offers context, and sometimes, the author wants to get that context out of the way first. In “The Missing Limousine” by Sanjena Sathian, the story explains why the protagonist gets hooked on The Bachelor, and why this is unusual for her, before getting into the story’s actual conflict.

Watching the bachelor was supposed to make life easier. I started getting into it a year or so after I began working at my brother’s salon. I had a regular stable of clients, but none was particularly in love with me. The problem was not my skill—I am talented at hair removal and competent at mani-pedis. The problem was our Yelp reviews, which said things like “Good eyebrow threading but that one girl makes you keep your eyes open for a whole minute before she starts and the way she stares makes you think she’s trying to suck your soul out.” Which I thought was dramatic.

By establishing basic facts, the author uses backstory to characterize her protagonist and propel the story into its central conflict. Do note: don’t write too much backstory, just give us enough to contextualize the conflict before moving the story forward.

5. How to Start a Story: Everyday Life

Your story’s conflict might dramatically alter your protagonist’s life. They might go on a journey, a quest, or even be forced into a life they didn’t ask for. Something that will highlight this dramatic shift of events is showing the reader what the protagonist’s everyday life was like.

“The Tunnel Under the World” by Frederik Pohl does just this.

On the morning of June 15th, Guy Burckhardt woke up screaming out of a dream. It was more real than any dream he had ever had in his life. He could still hear and feel the sharp, ripping-metal explosion, the violent heave that had tossed him furiously out of bed, the searing wave of heat.

He sat up convulsively and stared, not believing what he saw, at the quiet room and the bright sunlight coming in the window.

He croaked, “Mary?”

Guy Burckhardt wakes up from a terrible dream and finds himself back to everyday life: a shower, a wife, and an office job. It’s only when Guy investigates the eerie normalcy of his life that he comes to find all of it is a façade.

Note: starting your story with the protagonist waking up is generally a cliché idea. But, if you read all of Frederik Pohl’s story, you’ll understand exactly why he has to do this. Whether your protagonist gets shipped to the other side of the world or the other side of the universe, consider starting your story at home.

6. How to Start a Story: Theme

A theme is a central idea that propels a story forward. Themes are often abstract concepts, like love, justice, and fate vs. free will. When the characters of a story have to reckon with certain difficult situations, their decisions become springboards for the story’s various themes.

Sometimes, the story needs to unfold before any themes emerge. Other times, the author might lead with the theme before letting the story act that theme out. Take the opening lines from two works of classic literature:

Anna Karenina by Leo Tolstoy: Happy families are all alike; every unhappy family is unhappy in its own way.

A Tale of Two Cities by Charles Dickens: It was the best of times, it was the worst of times, it was the age of wisdom, it was the age of foolishness, it was the epoch of belief, it was the epoch of incredulity, it was the season of Life, it was the season of Darkness, it was the spring of hope, it was the winter of despair, we had everything before us, we had nothing before us, we were all going direct to Heaven, we were all going direct the other way-in short, the period was so far the like present period, that some of its noisiest authorities insisted on its being received, for good or for evil, in the superlative degree of comparison only.

Anna Karenina leads with the story’s dissection of happy and unhappy families, while A Tale of Two Cities leads with the bifurcated realities of the rich and the poor. Both novels, of course, have many more themes than just these, but these stories start rooted to a central idea, then unfurl to encompass a wider understanding of life.

7. How to Start a Story: Interesting Language

Charles Baudelaire once said “Always be a poet, even in prose.” Following this advice, sometimes all you need to start a story is some interesting word choice.

Take, for example, the story “Bread Week” by JoAnna Novak.

Your father calls you train wreck, as in, HEY, wake up, train wreck, bud, you’re falling asleep—beady, bootblack eyes narrowed on you from the Hemingway chair in the basement.

This brief introduction is packed with interesting language. For starters, it’s written in the second person, which is a daring way to write a story, because it situates the reader as the story’s protagonist without any other context. Additionally, the sentence is a mix of dialogue and narration, but without the use of quotation marks, making it structurally intriguing. Finally, the alliterative phrase “beady, bootblack eyes” is rich with description and characterization while also being a pleasure to read.

8. How to Start a Story: In Media Res

Under traditional storytelling models, like Freytag’s Pyramid, there’s a clear progression of events. After the exposition introduces us to the story’s characters, and settings, an inciting incident kicks off the story’s conflict. During the rising action, the conflict escalates, until a climax decides the fate of the protagonist.

When a story starts in media res (Latin: “in the middle of things”), the author chooses to start the story in the middle of the rising action, skipping over the exposition and the inciting incident.

For example, Homer’s The Iliad begins in the 9th year of the Greeks’ 10-year siege against Troy. We are introduced to major characters like Achilles, Agamemnon, and Odysseus, and also to the influence of the Gods like Hera and Zeus. Only as the story unfolds do we also gain some backstory, such as the reason for the war’s beginning and the previous lives of the story’s protagonists.

9. How to Start a Story: Frame Story

A story that starts at the end is called a frame story, which is another way to play with traditional narrative structures. Also known as a story-within-a-story, frame stories begin at the end of the conflict. Often, a character who is not part of the conflict will wander into the story; eventually, a character who was part of the conflict regales this wanderer, transporting us to the story’s beginning.

Wuthering Heights by Emily Brontë offers a great example. In this novel, Mr. Lockwood, who is not part of the story’s conflict, becomes a new tenant of Thrushcross Grange. Thrushcross Grange is tended to by Nelly, a housekeeper who witnessed all of the story’s conflicts. Nelly tells Mr. Lockwood about the romance, violence, drama, and death that has unfolded in Thrushcross Grange’s recent history.

Thus, the story begins at the end, with Mr. Lockwood moving into a now-quiet Thrushcross Grange. Then, the story jumps to the beginning, with the cast of characters that propel the house’s strange and awful history.

10. How to Start a Story: A Hook

A hook is a simple premise for a story that, when told to the reader, instantly draws them into the story. Many of the other examples listed here can also be viewed as hooks, but a hook directly states the reason for the story’s existence and invites the reader to learn more.

For example, the story “Chouette” by Claire Oshetsky hooks the reader instantly.

I dream I’m making tender love with an owl. The next morning, I see talon marks across my chest that trace the path of my owl-lover’s embrace. Two weeks later I learn that I’m pregnant.

You may wonder: How could such a thing come to pass between woman and owl?

I, too, am astounded because my owl-lover was a woman.

There is so much happening in these first few lines. A same-sex owl romance leads to an inter-species pregnancy? Yes, please tell me more.

11. How to Start a Story: A Question

Some stories begin with a question, and the entire story responds to the conundrum that question presents. Just like a story that starts with theme, starting with a question will draw the reader into the story’s central ideas.

Of course, a story can also begin with a question that baffles the reader, hooks them in, or tries to characterize its protagonists. Take the opening line of Gilbert Sorrentino’s novel Imaginative Qualities of Actual Things:

What if this young woman, who writes such bad poems, in competition with her husband, whose poems are equally bad, should stretch her remarkably long and well-made legs out before you, so that her skirt slips up to the tops of her stockings?

12. How to Start a Story: Compelling Characterization

Readers are drawn to stories for a variety of reasons. However, very few stories would satisfy if they lacked interesting characters. Great characterization can be a byproduct of the many good ways to start a story.

In “The Killer” by Sarah Gerard, we learn so much about the story’s protagonist just by watching her observe other people.

Carol was spying on the table next to theirs, hiding behind large shades. She loved the kind of basic beachfront retiree gossip they were dishing. It was almost a pastime for her, immersing herself in the narrative miasma of coconut-vanilla, spray-tan, condo pools, and other people’s secrets. The loudest of the group was calling the story’s subject’s affliction, with faux-sarcastic air quotes, a ‘social disease.’ Carol knew such a thing was more common in their small barrier island community than one would think. A lot of tea partiers, too much money, too much time. Nothing else to do but get drunk on Tom Collinses, mouth off about liberalism, sleep with your friends’ wives. She called up her own recent sins. She noted that the fishing nets on the ceiling of the Pelican had captured a mermaid, suspended her there like bycatch. Nathan returned from washing his hands and sat at their glass deck table. It overlooked the Gulf, and the yellow umbrella shielding them from the late morning sun cast them in a certain glow.

How Not to Start a Story

Because people have been telling stories for at least 4,400 years, there are many ways to start a story—and many of them are cliché, unconvincing, or simply boring for the reader. Let’s briefly look at how not to start a story.

Do note: rules are made to be broken, and there is no single standard of good or bad writing. So, while we discourage people from starting stories using the following methods, there might be a reason for doing so in your story. Just be intentional: if your story starts with a dream, for example, make sure that dream is absolutely essential to the story’s conflict, and that there is no better place from which to begin the story.

Nonetheless, if you want to submit your stories to literary journals or publications, be wary of the following story beginnings:

Starting with a dream.

This story start will mostly confuse the reader. They’ll think what’s happening in the dream is happening in real life, and when that turns out not to be the case, the reader will feel tricked, as well as bored with real life. Plus, dreams are rarely a source of conflict, which your story should start with.

The protagonist wakes up.

This is perhaps the most cliché method of starting a story. It doesn’t generate conflict or tell us anything interesting about the character. Yes, some stories need to show us everyday life before it’s drastically altered. But, since all people wake up, we don’t need to know about your character waking up, we just need to know details about everyday life that will, eventually, be altered.

Starting with character summary.

Don’t introduce your characters with basic, summaristic info. In other words, don’t start your story like this: “Sean Glatch was a 20-something writer in ABC City; one day, he woke up on the other side of the world.” This kind of writing is devoid of any style or intrigue. The reader wants to connect with the story’s characters on a personal level, so these summaristic details should be embedded in the story itself, rather than stated directly to the reader.

Cliche beginnings.

Once upon a time, people started their stories with “once upon a time.” But, even if your story begins on a dark and stormy night, tell the reader something a bit more compelling.

Starting before the conflict.

If the first page of your story doesn’t have conflict, then your story hasn’t started yet. Readers will nod off very quickly if they don’t know why they’re reading this story. The conflict doesn’t have to be clear or explicitly stated, but it does need to drive the narration right away, even as we’re learning about the story’s characters and settings.

Disconnected worldbuilding.

Perhaps your story begins on Planet X, which has an icy surface, endless tundras, and snowy mountains as tall as Olympus Mons. Nonetheless, the reader wants to follow people, not planets. So, instead of introducing the reader to this snowy world devoid of human conflict, show us the protagonist fighting against the cold, baring their teeth against chilling winds and subzero hypothermia.

Further Readings on Storytelling

For more resources on story writing and development, take a look at these handy articles.

- What is the Plot of a Story?

- Character Development Definition: A Look at 40 Character Traits

- Capturing the Art of Storytelling: Techniques & Tips

- Literary Fiction vs. Genre Fiction

- Novel Writing Tips: The Basics of Novel Writing

Additionally, the American Book Review has a list of the 100 best first lines from novels. Perhaps one of those lines will inspire your own story’s beginning.

Learn How to Start a Story at Writers.com

Whether you’re starting a flash fiction piece, an essay, a novel, a memoir, or an epic in dactylic hexameter, learn how to start a story at Writers.com. Take a look at our upcoming schedule!

The greatest difference between success and failure is not the lack of ideas, but their implementation. We all think of the next-big-thing over a dozen times a day, but the ability create that ‘big thing’ is what defines us. Same is the case with writers, we have great stories and arguments rummaging through our head, but when it comes to jotting them down, you don’t know where to begin. You are stuck with thoughts like ‘where do I even begin?’, ‘how to start a paragraph?’, ’Do I even have a great idea?’

Table of Contents

- Writing Help With Sentence Starters

- Why You Need to Know about Different Words to Start a Paragraph?

- List of Suitable Words to Start an Essay

- List of Transition Words to Begin a Paragraph that Show Contrast

- Body Paragraph Starters to Add Information

- Paragraph Starter Words Showing Cause

- Words to Start a Sentence for Emphasis

- Sentence Starters for Rare Ideas

- Paragraph Starter Words for Common Ideas

- Inconclusive Topic Sentence Starters

- How to Start a Sentence that Shows Evidence

- Paragraph Starters That Focus On the Background

- Words that Present Someone Else’s Evidence or Ideas

- Words for Conclusive Paragraph Starters

- Tips for Selecting the Right Words to Start Sentences

- FAQ

Paragraph starter words provide assistance in getting that head start with your writing. Following is all the information you require regarding different ways to start a paragraph.

Writing Help With Sentence Starters

Whether you are looking for the right words to start a body paragraph in an essay or the right words to effectively conclude your ideas, there are plenty of effective ways to successfully communicate your ideas. Following are the three main types of words you can use to start your paragraph:

Begin with Adverbs

Too much of anything is nauseating, including adverbs. All those ‘ly’ words in a sentence can get pretty overwhelming pretty fast. But when effectively added to the beginning of a sentence, it can help transition, contradict or even conclude information in an impactful manner. For instance, ‘consequently’ is a great transition word, ‘conversely’ helps include a counter argument and ‘similarly’ enables you to break an idea into two paragraphs. The trick to using adverbs as sentence starters is to limit them to just one or two in a paragraph and to keep switching between them.

Synonyms for ‘However’

If only there was a penny for every time most writers use the word ‘however,’ there’d be a shortage of islands to privately own on this planet; and perhaps on a few more planets too. Anyhow, nobody’s got those pennies to spare! Might as well opt for other, equally effective substitutes! Some good options include:

- Alternatively

- Nonetheless

- Nevertheless

- Despite this

Why You Need to Know about Different Words to Start a Paragraph?

The simplest answer to this question is to mainly improve your writing. The beginning of a paragraph helps set the mood of the paragraph. It helps determine the W’s of writing (When, Why, What, Who, Where) you are trying to address. Following are some ways learning the paragraph starter words can be assistive in writing great essays:

- Sentence starters help the resist the typical format of using subject-verb structure for sentences.

- Transition words help you sound more eloquent and professional.

- They help differentiate your writing from the informal spoken language.

- They help transition your thoughts more effectively.

List of Suitable Words to Start an Essay

- The central theme

- This essay discusses

- Emphasized are

- Views on

List of Transition Words to Begin a Paragraph that Show Contrast

- Instead

- Comparatively

- However

- Otherwise

- Conversely

- Still

- On the contrary

- On the other hand

- Nevertheless

- Different from

- Besides

- Other than

- Outside of

- Whereas

Body Paragraph Starters to Add Information

- Moreover

- Furthermore

- Additionally

- Again

- Coupled with

- Correspondingly

- Similarly

- Identically

- Whereas

- Likewise

- Not only

Paragraph Starter Words Showing Cause

- Singularly

- Particularly

- Otherwise

- Unquestionably

- Generally speaking

- Consequently

- For the most part

- As a result

- Undoubtedly

- In this situation

- Otherwise

- Hence

- Ordinarily

Words to Start a Sentence for Emphasis

- Admittedly

- Certainly

- Granted

- Above all

- As a rule

- Chiefly

Sentence Starters for Rare Ideas

- Rarely

- Not many

- Uncommonly

- Seldom

- A few

Paragraph Starter Words for Common Ideas

- The majority

- More than

- Many

- Numerous

- Almost all

- Usually

- Mostly

- Several

Inconclusive Topic Sentence Starters

- There is limited evidence

- Maybe

- Perhaps

- Debatably

- For the lack of evidence

How to Start a Sentence that Shows Evidence

- The result

- Therefore

- Predictably

- The connection

- Considerably

- With regard to

- It can be seen

- Subsequently

- As a result

- The relationship

- Hence

- After examining

- The convergence

- Apparently

- Effectively

Paragraph Starters That Focus On the Background

- Customarily

- Originally

- Earlier

- In the past

- Prior to this

- Historically

- Over time

- The traditional interpretation

- Up until now

- Initially

- Conventionally

- Formerly

Words that Present Someone Else’s Evidence or Ideas

- As explained by

- According to

- With regard to

- Based on the ideas of

- As demonstrated by

- As disputed by

- As stated by

- As mentioned by

Words for Conclusive Paragraph Starters

- In conclusion

- Obviously

- Finally

- Overall

- As expressed

- Thus

- Lastly

- Therefore

- As a result

- All in all

- In essence

- By and large

- To sum up

- On balance

- Overall

- In any case

- All things considered

- In other words

Tips for Selecting the Right Words to Start Sentences

Evidently, there are hundreds of starter words to select from. Qualified assignments writers can give you hundreds of them. How do you determine which of these essay starters will be the most impactful? Word selection mainly depends on the type of ideas being shared. Are you about to enter a counter argument or plan to introduce a new idea? Before you can begin hunting for the right words to start a new paragraph, do the following three steps:

- Determine what the previous paragraph discussed.

- Decide how the said paragraph will relate to the one before this?

- Now scan the appropriate list from the list to find a word that is best suited based on the purpose of the paragraph.

Keep the following tips in mind to make your paragraph starter words impactful and relevant:

- Always put a comma after every transition word in the beginning of a sentence.

- Add the subject of the sentence immediately after the comma.

- Avoid using the same transition word again and again. Opt for selecting different but suitable transition words.

- Don’t fret too much about using sentence starters during the first draft. It will be easier to add appropriate words during proofreading. Needless to say, always proofread your work to help make it flow better.

When looking for the right sentence starters for essays, make sure you are clear about the objective of every paragraph. What are you trying to tell? Is it an introductory paragraph or the body discussing ideas or contradictory information? The beginning of a paragraph should immediately reflect the ideas discussed within that paragraph. It might take some time, but with a little conscious effort and a lot of practice, using transition words would soon become second nature.

FAQ

What is a good word to start a paragraph?

The word you use to start a paragraph depends on the information you want to communicate. However, the right word to use should offer a smooth transition from the previous paragraph so readers can easily transition into the new section.

How do you start a paragraph example?

When writing essays that require evidence to support your claim, start your paragraph with the words like; For instance, For example, Specifically, To illustrate, Consider this, We can see this in, or This is evidence. That helps the reader to explain the ideas in the real world.

How to introduce a paragraph?

The best way to introduce a paragraph is by using a topic sentence that will briefly explain what you intend to discuss in the paragraph. Remember that the introduction of a paragraph is a topic sentence or the thesis of the entire essay.

How to start a second body paragraph transition words?

An essay shows the flow from the introduction to the last paragraph. Use transition words when writing a second body paragraph. By doing this, you show that the ideas in each section relate to each other.

What are some good words to start a conclusion paragraph?

Examples of words you can use are briefly, by and large, finally, after all, in any case, as a result, etc. After writing an engaging essay, ensure the conclusion paragraph is just as interesting by carefully selecting the types of words you will use.

What words to start a new paragraph?

You can begin with adverbs like Similarly, Consequently, or Conversely. Other words to start a new paragraph are: Nevertheless, That said, Alternately, At the same time, etc. Capture your readers’ attention by choosing the right words to use when starting a new paragraph.

How do you start your story?

Once upon a time… [wait no… that’s too cliche].

It was a dark and stormy night… [we’ve all heard that one before].

Just the other day… [hmmm… getting better…]

Let’s be honest – one of the hardest things to decide is where to start your story. If you don’t know where to begin, you don’t really know where to take things either. It’s easy to feel like you’re chasing your tail.

- Do you start by figuring out the story of where you’re going?

- Do you start by figuring out the story of where you’re coming from?

Storytelling can be complex and the information about storytelling, well, overwhelming. The good news, is that you can start either way — from the future (with a vision story) or the past (with an origin story). In this article I want to show you simple ways that you can dive right into telling your story (without fretting or worrying so much if you’re getting it right).

In a recent client workshop in New York City we unpacked this process, sharing some of my favorite ways to lead off any purposeful story. I shared six kick-off phrases that ANYONE can use to start a story in a way that’s compelling, uplifting, and inspiring. I like to think of it as Mad-Libs for transformational storytelling!

The story literally spills out of you, when you use one of these 6 kick-off phrases.

These 6 strategies are something we cover in great depth in our StoryU Online course Undeniable Story. Today, I want to share with you a few of them that are really important in setting the context and frame for your marketing, storytelling, and leadership efforts.

The first, a “future vision” story, is used when you want to describe your vision for change and growth. The second, your “origins” story, talks about where you are and where you’re coming from. Both stories are critical in terms of establishing the bounds of your story universe, and helping people to find themselves inside your world.

Here are three of my favorite ways to tell these stories.

Setting the right frame for your future vision story.

For a lot of us, we’re working on describing a world we imagine — the world we want to live in. But how do you tell the story of where you want to go in a meaningful way that doesn’t sound fantastical or unrealistic? How can you create a future-vision story that has your clients and prospects nodding, yes, totally, I believe you? How do you make it real?

At its heart, a story about the future is a story about possibility. We’re describing the way we want things to be — painting pictures of new ideas in the imaginations of our audience.

Here are three phrases to use to set up your own vision stories.

#1: “Imagine if …”

Imagine if is a really, really powerful phrase to start your story. It’s a way to ask your audience to suspend disbelief and imagine the following possibility — it’s a way to set up an invitation for people to connect to way they want or desire. Take a look at these examples:

Imagine if you could travel to any city around the world and feel like you’re living a little bit more like the locals. (This is the AirBNB story).

Imagine if you had the convenience of driving a car without the expense and hassle of insurance, parking, and all the other stuff that stresses you out. (This is the ZipCar story).

Traditional sales has people starting off with a problem and then closing with the solution — yet what this does, unfortunately, is it raises fear in people’s minds (and pumps cortisol, the stress hormone throughout their body). Problems make us feel tired, overwhelmed, and depressed. Future-vision stories that are anchored in possibility are providing an invitation, an uplift, a boost to your audience emotionally. When you invite people to imagine, you bring them into a space to begin to see the world in a new way.

Next comes the important part:

So you first is to set the stage with your “Imagine If…” phrase. It’s critical that you follow up with people and show them the picture you’re painting already exists.

For example, with ZipCar:

“Guess what? That possibility is already real. Let me show you how it’s already happening…”

It’s important in an possibility story to not wander so far off into dreamland that your listeners become skeptics, shaking their heads in disbelief. You need to show them where it’s working in the world. Say, “not only is this an amazing idea, it’s already real.”

Then introduce the creative tension. Only at this point, your story talks about the obstacles and challenges. How do we bring to scale this idea to all the cities of the world? How can you take your classroom of 100 and bring your breakthrough curriculum to life for 1,000 students?

To recap, here’s the three step sequence:

- “Imagine if…”

- “Let me show you how it’s real…”

- “Yet there’s obstacles that stand in the way of this promise being more available”

Interested in more storytelling tips? Try The Red Pill, my free 5-day email course that helps you get your story straight.

#2: Here’s what excites me…

This is another great way to start your story.

The phrase “Here’s what excites me” is a really easy way to talk about what you’re passionate about and paint a picture about where things are headed in the world.

For example:

Here’s what excites me about how technology is making it really easy for people to express themselves and use their voice…

Here’s what excites me about what’s happening in the classroom, both online and in person, today.

Here’s what excites me about some of the environmental changes people are making in their lives.

You always want to tell a story that excites you. Why? Because our emotions are contagious. So, start from the place of what turns you on. What’s cool? What’s intrigues you? What gets you all hot and bothered?!? Paint the picture of the exciting changes you see happening and this will others excited — yet only if YOU are excited too.

What these phrases have in common.

All of these little phrases have one thing in common: they serve as an invitation. They have an underlying emotion — a curiosity that invites people, draws them in. Emotional content is what lifts people up. They initiate attraction and engagement. Because we’re all naturally drawn to things that are expansive and have energy. They create a space between you and your audience, and invite the excitement of possibility to take ahold of both of you.

When telling future vision stories, start with an invitation, a possibility. Then introduce the creative tension. (This is the Feel Good Principle that we talked about earlier).

Possibilities are an invitation. When we talk about possibility, we get people turned on and excited about what is possible. From this place, magic happens.

What about your origins story?

How do you talk about where you’ve come from?

While a Vision Story transports us into the future, an Origins Story talks about your past: who you are, where you come from, and what have you done. Knowing how to talk about the past, in a succinct, pithy, and relevant manner can be anxiety producing for many of us. We don’t know what to say, without feeling like we’re bragging, boasting, or being a bore.

Which is why we have several catch phrases we love at Get Storied that help people jump into their Origins Story in a way that’s easy, exciting, and invites the listener in.

Here’s one of my favorites:

#3: “I remember when…”

A member of our StoryU tribe, Sarah Peck, worked for a number of years at an architecture firm before transitioning to her life in writing and design communications. In the architecture world, the transformation from the paper world to the digital world upended the industry in less than a decade. It was common to hear people talk about how much things changed by using the phrase, ‘I remember when…” to describe the rapid changes happening to her organization.

I remember when we used to do everything by hand… I remember when we used to scan and Fed-Ex drawings to our clients; now we can send blueprints digitally in just a few seconds!

If you’re part of the start-up craze, you’ll hear founders say things like: “I remember when we were a startup, drinking crappy Folgers coffee and working out of our garage.”

The key phrase “I remember when” let’s you acknowledge how far things have come, and what’s continue to change for your organization, industry or sector. It allows you to be circumspect. By reminding people of the past, you can create a contrast frame with the unfolding future, and again how excited you are of the new possibilities ahead.

“I remember when we used to do things this way, and look how far we’ve come since them.”

Let people understand where you’re coming from.

The key with Origins Stories is that you use them as a way of offering perspective. Origin Stories lay the foundation for your faith in the future and what’s coming ahead. By sharing what you’ve accomplished so far, you can inspire confidence in where things are going.

“I have no doubt we’re going to get through this,” you can say. “I’m so excited about these opportunities.” “If we’ve done this much since we began, imagine where we can go in the next five, ten years ahead.”

Origin stories create rooting and foundation. These story frames let you show not only who you are, but where you’ve come from — and, if you want to string two stories together, it sets the stage for you to paint a picture of where you want to go.

How do you start your stories?

These are three of our favorite ways to start your vision and origin stories — three easy mad-lib phrases that kick things off with the right tone and frame for your message.

Share with us your own catch phrases or let us know what your vision story is in the comments below! We love reading your stories and we’d love to hear what you have to say.

As Glinda the Good Witch says in The Wizard of Oz, “It’s always best to start at the beginning.” That’s where editors and literary agents generally get going, so perhaps you should, too. Here are some strategies, accompanied by exemplars from literature, for making the first line of your novel or short story stand out so that the reader can’t help but go on to the second and the third and so on to see what else you have to say:

1. Absurd

“‘Take my camel, dear,’ said my Aunt Dot, as she climbed down from this animal on her return from High Mass.” — Rose Macaulay, The Towers of Trebizond

Are you in the mood for amusement? This opening line makes it clear that farce is in force.

2. Acerbic

“The human race, to which so many of my readers belong, has been playing at children’s games from the beginning, and will probably do it till the end, which is a nuisance for the few people who grow up.” — G. K. Chesterton, The Napoleon of Notting Hill

Astute observations accompanied by a implied sigh of disgust are tricky to master, but Chesterton, one of the most multifaceted men of letters, lights the way for you with this sample of the form.

3. Bleak

“The sky above the port was the color of television, tuned to a dead channel.” — William Gibson, Neuromancer

Oh, by the way, just in case you missed the forecast? Don’t expect any fluffy bunnies or fragrant blossoms or dulcet giggles to show up in this seminal cyberpunk story. A spot-on metaphor expresses the story’s nihilism, letting you know what you’re in for and lugubriously inviting you in.

4. Confiding

“There was a boy called Eustace Clarence Scrubb, and he almost deserved it.” — C. S. Lewis, The Voyage of the Dawn Treader

The author of the Chronicles of Narnia no sooner introduces by name a new character in the latest installment than, in just five more words, he succeeds in telling you everything you need to know about him. Well, got that out of the way.

5. Cynical

“Justice? — You get justice in the next world, in this world you have the law.” — William Gaddis, A Frolic of His Own

Somebody got up on the wrong side of the bed this morning — and maybe the bed’s shoved up against the wall, and that attitude is a permanent condition. The stage is set for an unhappy beginning, middle, and ending.

6. Disorienting

“It was a bright cold day in April, and the clocks were striking thirteen.” — George Orwell, 1984

Ho-hum — huh? Orwell’s opening line creates a slight but immediate discordance that sets you up for an unsettling experience.

7. Enigmatic

“Once upon a time, there was a woman who discovered she had turned into the wrong person.” — Anne Tyler, Back When We Were Grownups

It will not surprise you to learn that the protagonist sets about retracing her steps and striving to correct the error, but after reading this subtle but striking first line, can you resist finding out how she does it?

8. Epigrammatic

“The past is a foreign country; they do things differently there.” — L. P. Hartley, The Go-Between

This offbeat observation from Hartley’s novel of painful reminiscence is a blindsidingly original statement that one will feel compelled to read about just how the writer acquired this wisdom.

9. Expository

“In our family, there was no clear line between religion and fly fishing. We lived at the junction of great trout rivers in Montana, and our father was a Presbyterian minister and a fly fisherman who tied his own flies and taught others. He told us about Christ’s disciples being fishermen, and we were left to assume, as my brother and I did, that all first-class fishermen on the Sea of Galilee were fly fishermen, and that John, the favorite, was a dry-fly fisherman.” — Norman McLean, A River Runs Through It

By the end of this paragraph, you already know a great deal about the narrator’s family (especially the father) — but thanks to the introduction, as clear as a snow-fed mountain river, you want to know more.

10. Foreboding

“I have never begun a novel with more misgiving.” — W. Somerset Maugham, The Razor’s Edge

The author is a bit intrusive here, true enough, but it is kind of him to let us know that we’re in for a bit of unpleasantness. But if he can express such profound reluctance, it must be quite a story.

11. Gritty

“There was a desert wind blowing that night. It was one of those hot dry Santa Anas that come down through the mountain passes and curl your hair and make your nerves jump and your skin itch. On nights like that every booze party ends in a fight. Meek little wives feel the edge of the carving knife and study their husbands’ necks. Anything can happen. You can even get a full glass of beer at a cocktail lounge.” — Raymond Chandler, Red Wind

Chandler, the master of hard-bitten crime noir, makes it obvious that this story is not going to end well. You can almost hear the smoky, whiskey-soured, world-weary narration in your head. And this quote comes from one of Chandler’s half-forgotten short stories.

12. Inviting

“Whether I shall turn out to be the hero of my own life, or whether that station will be held by anybody else, these pages must show.” — Charles Dickens, David Copperfield

Dickens extends his arm toward the passageway within, welcoming you to enter what promises to be an entertaining story.

13. Picaresque

“In the last years of the Seventeenth Century there was to be found among the fops and fools of the London coffee-houses one rangy, gangling flitch called Ebenezer Cooke, more ambitious than talented, and yet more talented than prudent, who, like his friends-in-folly, all of whom were supposed to be educating at Oxford or Cambridge, had found the sound of Mother English more fun to game with than her sense to labor over, and so rather than applying himself to the pains of scholarship, had learned the knack of versifying, and ground out quires of couplets after the fashion of the day, afroth with Joves and Jupiters, aclang with jarring rhymes, and string-taut with similes stretched to the snapping-point.” — John Barth, The Sot-Weed Factor

Oh, but you know this novel is going to be juicy. This snide introduction to the main character conveys a promise of a continuous feed of schadenfreude.

14. Pithy

“Ships at a distance have every man’s wish on board.” — Zora Neale Hurston, Their Eyes Were Watching God

Every once in a while there comes an opening line that seems to have an entire story folded up inside it. But it’s just the label on the envelope. And I challenge you to withstand the urge to open it up and read the message.

15. Poetic

“We started dying before the snow, and like the snow, we continued to fall.” — Louise Erdrich, Tracks

A somber, stately metaphor draws us in despite the pervasively gloomy imagery.

16. Prefatory

“It was the best of times, it was the worst of times, it was the age of wisdom, it was the age of foolishness, it was the epoch of belief, it was the epoch of incredulity, it was the season of Light, it was the season of Darkness, it was the spring of hope, it was the winter of despair.” — Charles Dickens, A Tale of Two Cities

Many people associate Dickens with whimsy and eccentricity, but A Tale of Two Cities is a stern study of the insanity of mob rule, and this floridly eloquent prologue sets the stage like the presenter of a Shakespearean prologue: “Epic Ahead.”

17. Romantic

“He was born with a gift of laughter and a sense that the world was mad.” — Raphael Sabatini, Scaramouche

Romantic, that is, in the sense of lust for life, not love for another. This author of swashbucklers like The Sea Hawk and Captain Blood (and, of course, Scaramouche) lets you know right away that you are about to meet someone larger than life.

18. Sarcastic

“It is a truth universally acknowledged, that a single man in possession of a good fortune, must be in want of a wife.” — Jane Austen, Pride and Prejudice

Austen didn’t invent the word snark — but she certainly refined the application of the quality. Notice, though, how subtle this line is. It’s a bon mot — understated, yet with teeth behind that prim smile.

19. Sour

“If you really want to hear about it, the first thing you’ll probably want to know is where I was born, and what my lousy childhood was like, and how my parents were occupied and all before they had me, and all that David Copperfield kind of crap, but I don’t feel like going into it, if you want to know the truth.” — J. D. Salinger, The Catcher in the Rye

Can you find it in your heart to forgive this young man his grievously bad attitude? More likely, you’ll be impressed by — and want to immerse yourself in more of — his insolence.

20. Unexpected

“Every summer Lin Kong returned to Goose Village to divorce his wife, Shuyu.” — Ha Jin, Waiting

This seemingly pedestrian introduction upends itself with an intriguing premise that raises a question in the reader’s mind that must be answered.

The opening lines of a story carry a lot of responsibility. They act as an invitation for someone who’s glanced at the first page of your book to either put it back down or keep reading.

Whether you’re just figuring out how to start a novel, or revisiting Page 1 of a first draft, here are 11 ways to start a story:

- 1. Craft an unexpected story opening

- 2. Start with a compelling image

- 3. Create interest with immediate action

- 4. Begin the book with a short sentence

- 5. Pose a question for the reader

- 6. Introduce the plot and characters

- 7. Build a convincing world and setting

- 8. Do something new with your writing

- 9. Create tension in the beginning of the novel

- 10. Put your mind and heart in it

- 11. Capture your readers’ attention

1. Craft an unexpected story opening

Think of the opening to Nineteen Eighty-Four, or Iain Banks’s, The Crow Road, “It was the day my grandmother exploded.” Of course, your opening doesn’t have to be as outrageous as these but always aim for the unusual. In other words: think of how people will be expecting the book to start, then take the plot in another direction. [Gareth Watkins]

If you’re in the mood to get some similarly twisty ideas, you can go here to see a list of 70+ plot twist examples.

“It was a bright cold day in April, and the clocks were striking thirteen.”

— George Orwell, Nineteen Eighty-Four

2. Start with a compelling image

Many editors will tell you to avoid exposition — the dreaded info dump — at the start of your manuscript. One of the best ways to avoid this is to begin on an image. By focusing on sensory detail right at the start — sight, sound, taste, touch, smell — and by conveying a particular, defined setting, you can absorb readers immediately within the tangible world of your novel. Context and background will come later, but a compelling image can be a fantastic hook. [Harrison Demchick]

“It was a special pleasure to see things eaten, to see things blackened and changed. With the brass nozzle in his fists, with this great python spitting its venomous kerosene upon the world, the blood pounded in his head, and his hands were the hands of some amazing conductor playing all the symphonies of blazing and burning to bring down the tatters and charcoal ruins of history.”

— Ray Bradbury, Fahrenheit 451

Novels that open in medias res (latin for «in the midst of action») are often really effective at immediately grabbing the reader and establishing stakes and tension. A classic example is Lord of the Flies, which starts with the boys on the island and then fills in the details of how they got there later. If you go this route, you need to be sure your opening action is compelling enough that the reader is prepared to wait for character setup later. [Jeanette Shaw]

“The boy with fair hair lowered himself down the last few feet of rock and began to pick his way toward the lagoon. Though he had taken off his school sweater and trailed it now from one hand, his grey shirt stuck to him and his hair was plastered to his forehead.”

— William Golding, Lord of the Flies

PRO-TIP: Want to find out which famous author you write like? Take our 1-minute quiz below!

🖊️

Which famous author do you write like?

Find out which literary luminary is your stylistic soulmate. Takes one minute!

4. Begin the book with a short sentence

Start with something sparse that flicks on our curiosity, above all. [Fran Lebowitz]

“In a hole in the ground there lived a hobbit.”

— J.R.R. Tolkien, The Hobbit

FREE COURSE

How to Write a Novel

Bestselling novelist Ben Galley will guide you from page 1 to the finish line.

5. Pose a question for the reader

The reader should be looking for an answer. The opening to your novel should be a question that can only be answered by reading on. This doesn’t need to be literal, or overt, it can even be poetic, or abstract, but there must be a wound that can only be healed by reading on. [Nathan Connolly]

“It was a queer, sultry summer, the summer they electrocuted the Rosenbergs, and I didn’t know what I was doing in New York.»

— Sylvia Plath, The Bell Jar

Write. Edit. Format. All for free.

Sign up to use Reedsy’s acclaimed book-writing app for free

Learn how Reedsy can help you craft a beautiful book.

6. Introduce the plot and characters

There are many ways to start a novel, but in my experience, the most successful beginnings have the magnetic effect of appealing to an emotion that all readers possess: curiosity. Make them immediately ask of your characters: What is this place? Why are they here? What are they doing? Who is involved? Where is this going? If you can pique your readers’ curiosity from the very first sentence, you can will them to keep reading before they even know they like your book. [Britanie Wilson]

«Royal Beating. That was Flo’s promise. You are going to get one Royal Beating.»

— Alice Munro, Who Do You Think You Are?

At the same time, it’s important that the start of your book isn’t entirely cryptic. Your opening must sustain your readers’ interest in some way if you are to keep them reading through to chapter two, and reveal more and more information in the plot points to come.

Pro tip: Starting your writing with dialogue is considered a no-no by some, but can actually be a great way of achieving this effect.